Abstract

Background: The purpose of this study was to compare the long-term revision rate of in situ ulnar nerve decompression with anterior subcutaneous transposition surgery for idiopathic cubital tunnel syndrome. Methods: This retrospective, multicenter, cohort study compared patients who underwent ulnar nerve surgery with a minimum 5 years of follow-up. The primary outcome studied was the need for revision cubital tunnel surgery. In total, there were 132 cases corresponding to 119 patients. The cohorts were matched for age and comorbidity. Results: The long-term reoperation rate for in situ decompression was 25% compared with 12% for anterior subcutaneous transposition. Seventy-eight percent of revisions of in situ decompression were performed within the first 3 years. Younger age and female sex were identified as independent predictors of need for revision. Conclusions: In the long-term follow-up, in situ decompression is seen to have a statistically significant higher reoperation rate compared with subcutaneous transposition.

Keywords: cubital tunnel syndrome, nerve, diagnosis, transposition, in situ decompression, hand, anatomy, nerve, basic science, ulnar nerve, long-term, reoperation

Introduction

Cubital tunnel syndrome is the second most common upper extremity compressive neuropathy. There are a variety of procedures that have been described to treat this compression. None have been shown to be superior in the treatment of this disease; thus, the determination of the surgery to be done is based on surgeon preference. The treatments fall into 2 common categories—in situ decompression (IS) and anterior transposition (AT). In situ decompression has gained popularity over the past decade and a half, 1 increasing from 51% to 62% of cubital tunnel procedures performed in the ambulatory surgery setting. More recently, the percentage of in situ decompression has gone up to 80% of initial ulnar nerve procedures. The incidence of cubital tunnel surgery in general has additionally increased during this time, which is likely related to the relaxation of operative indications for cubital tunnel syndrome 2 because of the noted importance of treating the disease before intrinsic weakness has occurred. The recent popularity of in situ release is related to an increasing body of literature that has reported equivalent outcomes of IS compared with AT, with a lower reported complication rate as well as a theoretical maintenance of nerve vascularity.3-6 All studies have had short- to medium-term follow-up of 1 to 4 years. Long-term outcome data on procedures for cubital tunnel are lacking. The purpose of this investigation was to identify the long-term outcome of in situ ulnar nerve release compared with anterior subcutaneous transposition. A recent meta-analysis 7 identified the absence of standardized outcome measures for cubital tunnel syndrome. Thus, revision rates of surgery have been used as an outcome measure of failure of surgery.8,9 Because of the increase in the performance of in situ release, we secondarily sought to evaluate factors associated with failure of initial in situ release or subcutaneous transposition of the ulnar nerve.

Materials and Methods

Approval for this study was obtained from the institutional review board of the participating institutions. Once obtained, the billing code 64718 was used to identify patients who had undergone cubital tunnel surgery between 1998 and 2008. Three hundred ninety-eight patients were identified. Chart reviews were then performed, and exclusion criteria were applied, including previous elbow surgery, previous elbow trauma, and age less than 18 years. Chart review also identified the patients with documented revision surgery. For those patients who did not have documented revision surgery, letters were mailed to inform patients of the study, followed by telephone contact. Patients with whom contact was made were included in the study. As our locality consists largely of 2 health centers and 2 separate electronic medical records (EMRs), we cross-referenced our patients in the opposite EMR in order to not lose follow-up or second opinions outside of the original hospital. Our outcome measure in this long follow-up study was chosen to be reoperation rate only due to the lack of standardized outcome measures for cubital tunnel syndrome. 7

Four fellowship-trained hand surgeons were included in the study from 2 hospital systems. Two surgeons exclusively performed subcutaneous AT as a primary surgery for idiopathic cubital tunnel syndrome. Both surgeons made a 10-cm incision posterior to the medial epicondyle and in line with the ulnar nerve. Decompression of all points of compression from the arcade of Struthers to the deep flexor carpi ulnaris (FCU) fascia was performed. The intramuscular septum was excised, and a “soft tissue” barrier was constructed to prevent resubluxation. Postoperatively, these patients were treated in a long-arm splint for 1 week. These patients were used as the control group. Two surgeons primarily performed in situ release in patients, transposing the nerve when unstable intraoperatively. Of these patients, those who were intended for in situ release but underwent AT due to subluxation of the nerve were not included in the study. Both surgeons made a 5-cm incision, posterior to and centered about the medial epicondyle. They performed decompression of Osborne ligament and FCU fascia. The nerve was evaluated for stability through a full range of motion prior to closure. Postoperatively, these patients were treated with soft dressing and immediate motion. The vast majority of patients in both groups were McGowan 1 or 2, with sensory symptoms only and no involvement of intrinsic musculature. The original decision to operate was made by the surgeon and the patient based on the resistance of their significant symptoms to conservative care, including night soft elbow splints. Similarly, the decision to proceed with revision surgery was a combined decision between patient and surgeon, related to failure to improve or worsening of symptoms resistant to an appropriate course of hand therapy. The “failures” had initial improvement but were then followed by recurrence of symptoms. In situ procedures that required revision were all transposed anteriorly, where the anteriorly transposed cases were revised to a submuscular position or decompressed in the subcutaneous plane again.

T tests were used to compare surgery type with continuous variables (age, follow-up time), and χ2 tests were used for categorical variables. Multivariate Cox regression was used to compare revision rates between surgery types, controlling for age, sex, diabetes status, and hypothyroid status. The Cox regressions were run 2 ways: (1) treating bilateral surgeries as independent patients (main analysis); and (2) including only the first procedure for bilateral patients so that the assumption of independence was not violated (sensitivity analysis).

Results

A total of 136 cases were included in the study (AT = 60, IS = 76), corresponding to 119 patients, due to exclusions as well as duration of follow-up. All the revision surgeries were identified by the medical record review. We were able to contact all the included patients, and none had had a revision surgery. The largest reason for exclusion was our inability to contact patients for follow-up. Three of the patients had multiple revisions (1 in AT, 2 in IS). For all analyses, we only used the first revision for these patients. Thus, our analysis data set consisted of 132 cases (AT = 59, IS = 73) corresponding to 119 patients conducted by a total of 4 surgeons.

Among these 119 patients, there were 13 patients (11%) who had bilateral procedures. For our primary analysis, we included all 132 cases, although there was a slight violation of the independence assumption of our statistical analysis methods. However, as a sensitivity analysis, we also randomly dropped a side for the bilateral patients. The sensitivity analysis showed that the clustering observed within 11% of our sample had a negligible effect on all results. Thus, here we present results from the full 132 cases.

Descriptive summaries were made of patient characteristics stratified by surgery type (AT or IS, Table 1).

Table 1.

Summaries of Patient Characteristics by Surgery Type.

| Patient characteristics | AT (n = 59) | IS (n = 73) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y, mean (SD) | 47 (11) | 48 (13) | .637 |

| Sex, male, No. (%) | 29 (49.2) | 18 (24.7) | .003 |

| Side, L, No. (%) | 33 (55.9) | 28 (38.4) | .002 |

| Diabetes, No. (%) | 16 (27.1) | 16 (21.9) | .488 |

| Hypothyroid, No. (%) | 9 (15.2) | 15 (20.6) | .433 |

| Follow-up time, mo, mean (SD) | 117 (53) | 90 (47) | .003 |

Note. AT = anterior transposition; IS = in situ decompression.

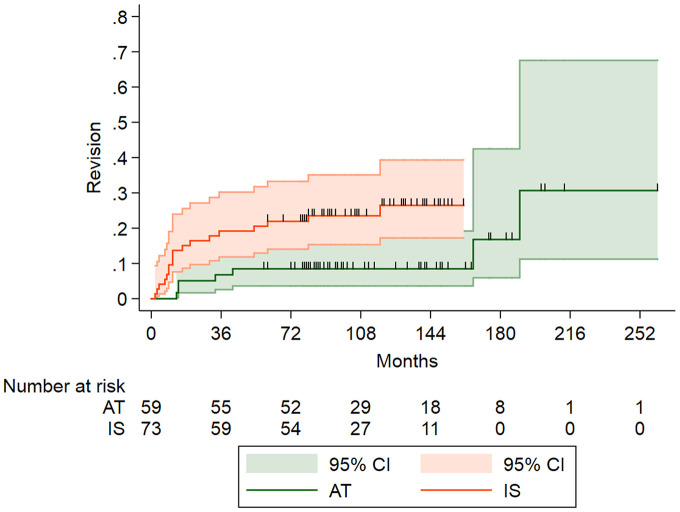

Seven (12%) of the 59 cases of AT surgeries had revisions, and 18 (25%) of the 73 cases of IS surgeries had revisions. A cumulative time to revision Kaplan-Meier plot stratified by surgery type (Figure 1) showed that the revision rate was higher in the IS cases (log rank test P value = .014). We also reported rates corresponding to 3, 5, and 10 years post surgery (Table 2). The rates correspond to points on each curve in Figure 1 (3 years = 36, 60, 120 months). Note that these rates are cumulative, that is, rates can only increase over time.

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier plot comparing revision rates between surgery types over time.

Note. CI = confidence interval; AT = anterior transposition; IS: in situ decompression.

Table 2.

Revision Rates at 3, 5, and 10 Years for Each Surgery (100% – Survival = Revision Rate) and the 95% Confidence Interval from the Kaplan-Meier Model Shown in Figure 1.

| Revision | AT | IS |

|---|---|---|

| 3 y | 7% (2%-17%) | 19% (12%-31%) |

| 5 y | 8% (3%-20%) | 22% (14%-34%) |

| 10 y | 8% (3%-20%) | 27% (17%-41%) |

Note. AT = anterior transposition; IS = in situ decompression.

As the rate for AT is constant at 8% between 5 and 10 years, this means that there were no revisions occurring for AT during those 5 years. It can be seen in the AT curve (green) in Figure 1 that the rate stays constant from ~45 to 170 months. Also, each black vertical line indicates a person who was lost to follow-up (ie, “censored”). There was an increase in revision rates at ~170 months, and then another jump around 195 months. There were only 8 patients with follow-up from month 180 onward (that is why the 95% confidence interval—green shaded region—gets wider, which indicates less confidence in the revision rate estimates). Also, the plot shows that there are no patients in the IS group with follow-up data beyond ~170 months.

Of the 18 IS revisions, 14 (78%) occurred within the first 3 years. This is evident in Figure 1 for the IS curve (red)—it takes the biggest jump within the first 18 months. Then, there is a fairly gradual increase over the next 7 years.

From the results in Table 3, we see that there is about 67% lower hazards for the AT surgery needing a revision compared with IS (hazard ratio = 0.33, 95% confidence interval = 0.12-0.89, P = .028). The sensitivity analysis (using 1 case/patient) yielded similar findings.

Table 3.

Results for Cox Proportional Hazards Analysis for All 132 Cases (Primary Analysis).

| Predictor | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|

| Surgery type (AT vs IS) | 0.33 (0.12-0.89) | .028 |

| Age (for each 1-y increase) | 0.96 (0.93-1.00) | .027 |

| Female vs male | 5.42 (1.23-23.88) | .025 |

| Diabetes vs not | 0.48 (0.14-1.64) | .244 |

| Hypothyroid vs not | 0.31 (0.07-1.35) | .119 |

Note. CI = confidence interval; AT = anterior transposition; IS = in situ decompression.

Discussion

Surgical management of cubital tunnel syndrome remains a mainstay of treatment for patients who fail nonoperative management. Over the past decade, 1 there has been increasing popularity of in situ release of the ulnar nerve, rather than AT. In addition, the popularity of endoscopic in situ cubital tunnel release has also been growing. The decision to perform in situ transposition is related to the ease of surgery with less dissection, less disruption of nerve vascularity, and a reported equivalent outcome to AT in the early postoperative period. The results of revision surgery have been shown to be less successful than primary cubital tunnel release surgery. 10 Thus, achieving long-term relief of the nerve symptoms without the need for revision surgery is ideal.

The first large retrospective cohort study 11 published in 1995 of IS reported 5% reoperation rate with an average of 4-year follow-up. It was not until 2005 that prospective randomized trials were performed evaluating IS compared with AT,3,5 showing equivalent outcomes and revision rates in both studies with 1-year follow-up. Furthermore, 2 meta-analyses have found similar revision rates between IS and AT; however, these studies also include submuscular transposition.6,12 Finally, a retrospective cohort study of in situ cubital tunnel release, without a control group, showed a 7% reoperation rate. 4 All studies have had short- to medium-term follow-up. To date, no study has taken into account the long-term reoperation rate and the difference between in situ release and AT. Our data diverge from the previously published equivalent outcomes of primary cubital tunnel surgery, both in the short term and in the long term. The greater reoperation rate seen in our in situ cohort population is confirmed by a more recently published outcome study that found a 19% reoperation rate on IS in the first 5 years. 9 This was published by the same institution that initially published the previously referenced 7% reoperation rate for in situ release of the ulnar nerve. 4

Although we report a higher failure rate of early in situ release than previously published, we still feel that it has its place and should not be discarded. When choosing this as a primary procedure, one must take into account the patient-specific variables and perform AT in those groups shown to undergo early failure with in situ release. After controlling for variables, the risk factors identified in our study include younger age and female sex. Comorbidities, including diabetes and hypothyroidism, are not seen to contribute to cubital tunnel syndrome in the same way that they do for carpal tunnel syndrome. This is in agreement with the findings in 2 recently published articles,8,9 both of which identified increased rate of revision in younger age (patients younger than age 50 at the time of surgery). In addition, our study identifies a 6:1 risk for women to undergo revision cubital tunnel surgery. This is conjectured to be attributed to known ligamentous laxity in the female population, which may lead to subluxation or dislocation of the nerve. Furthermore, women have a higher carrying angle of their elbow, making them more susceptible to the stretch phenomenon as the cause of their symptoms at the outset (Tom Fischer, personal communication, March 2016). Thus, measuring the carrying angle prior to surgery may be helpful in avoiding revision surgery.

An additional explanation for the difference of outcome between procedures is that in situ transposition does not relieve the traction on the ulnar nerve.13,14 This traction is felt to be a component of persistent and/or dynamic ischemia of the nerve due to the compression of intrinsic vessels. Our opinion is this tension, as the decompressed nerve gets older, becomes critical and symptoms return. It is also true that IS is technically and psychologically “easier” to revise than an AT. The tendency, in our opinion, right or wrong, is that a surgeon will be quicker to revise the symptom-persistent decompression and may “work up” or try further nonoperative measures in the AT. This bias, in and of itself, will increase the chances and rates of revision of IS. However, in consideration of blood flow to the ulnar nerve, the discussion of sacrificed vascularity of the ulnar nerve with transposition has certainly been mentioned on many occasions to be a potential significant drawback to the procedure. However, to date, it has not been proven to be a true cause of nerve ischemia. 15

The surgeon’s decision to perform in situ release over AT takes into account the following considerations: decreased dissection of the ulnar nerve, decreased dissection of surrounding tissues, decreased disruption of vascularity, decreased cost of surgery, and decreased operative time. When evaluating the potential cost savings of this procedure, the cost differential between the 2 procedures is $300. 1 This takes into account the operative time, anesthesiologist cost, cost of therapy, and cost of lost time from work. Although there may be this up-front cost savings, the potential need for revision surgery would significantly increase the cost of care for these patients. In revision surgery, the surgical time is prolonged, and the recovery can be time- and therapy-intensive. This can subsequently lead to additional costs related to time off work and cost of therapy sessions. Regarding operative time, the reported time difference between the 2 procedures is 10 minutes. 16 If AT is necessary, the additional 10 minutes spent intraoperatively is less than the counseling time of the patient in the office with a poor surgical outcome, not to mention the surgical and recovery time involved in revision surgery.

The limitation of this study is its retrospective nature. Certainly, the patients not included may have had a good outcome. Inability to identify and include these patients with successful outcome in the study likely increased the identified rate of failure for both procedures. In addition, the preoperative duration of or the severity of the disease was not included in the study as the medical record was inadequate to determine this. However, this severity level has not been shown to be predictive of outcome following cubital tunnel surgery.17,18

Conclusion

Surgical outcomes of surgery for cubital tunnel syndrome, comparing anterior subcutaneous transposition and IS, are not equivalent as previously thought. In situ transposition has been found in this study at all time points to have a statistically significant higher rate of revision compared with AT. Those at risk of revision are of younger age and female sex. It would be our recommendation to avoid in situ release at least in these patient populations and perform anterior subcutaneous transposition as their primary surgery.

Footnotes

Authors’ Note: This work was performed at University of Utah and the Orthopedic Specialty Hospital in Salt Lake City, Utah.

Ethical Approval: All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.

Statement of Human and Animal Rights: No animals were tested in this study.

Statement of Informed Consent: Informed consent was obtained from all patients for being included in the study.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Douglas T. Hutchinson  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4156-1520

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4156-1520

References

- 1. Soltani AM, Best MJ, Francis CS, et al. Trends in the surgical treatment of cubital tunnel syndrome: an analysis of the national survey of ambulatory surgery database. J Hand Surg Am. 2013;38(8):1551-1556. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2013.04.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Tomaino MM, Brach PJ, Vansickle DP. The rationale for and efficacy of surgical intervention for electrodiagnostic-negative cubital tunnel syndrome. J Hand Surg Am. 2001;26(6):1077-1081. doi: 10.1053/jhsu.2001.26327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bartels RHMA, Verhagen WIM, van der Wilt GJ, et al. Prospective randomized controlled study comparing simple decompression versus anterior subcutaneous transposition for idiopathic neuropathy of the ulnar nerve at the elbow: part I. Neurosurgery. 2005;56:522-530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Goldfarb CA, Sutter MM, Martens EJ, et al. Incidence of re-operation and subjective outcome following in situ decompression of the ulnar nerve at the cubital tunnel. J Hand Surg Eur Vol. 2009;34(3):379-383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Nabhan A, Ahlhelm F, Kelm J, et al. Simple decompression or subcutaneous anterior transposition of the ulnar nerve for cubital tunnel syndrome. J Hand Surg Br. 2005;30:521-524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Zlowodzki M, Chan S, Bhandari M, et al. Anterior transposition compared with simple decompression for treatment of cubital tunnel syndrome. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(12):2591-2598. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.G.00183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Shi Q, MacDermid JC, Santaguida PL, et al. Predictors of surgical outcomes following anterior transposition of ulnar nerve for cubital tunnel syndrome: a systematic review. J Hand Surg Am. 2011;36(12):1996.e1-2001.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2011.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gaspar MP, Kane PM, Putthiwara D, et al. Decompression for patients with idiopathic cubital tunnel syndrome. J Hand Surg Am. 2016;41(3):427-435. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2015.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Krogue JD, Aleem AW, Osei DA, et al. Predictors of surgical revision after in situ decompression of the ulnar nerve. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2015;24(4):634-639. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2014.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Aleem AW, Krogue JD, Calfee RP. Outcomes of revision surgery for cubital tunnel syndrome. J Hand Surg Am. 2014;39(11):2141-2149. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2014.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Nathan PA, Keniston RC, Meadows KD. Outcome study of ulnar nerve compression at the elbow treated with simple decompression and an early programme of physical therapy. J Hand Surg Br. 1995;20(5):628-637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bartels DH, Menovsky T, Van Overbeeke JJ, et al. Surgical management of ulnar nerve compression at the elbow: an analysis of the literature. J Neurosurg. 1998;89(5):722-727. doi: 10.3171/jns.1998.89.5.0722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kleinman W. Cubital tunnel syndrome: anterior transposition as a logical approach to complete nerve decompression. J Hand Surg Am. 1999;24(5):886-897. doi: 10.1053/jhsu.1999.0886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mitchell J, Dunn JC, Kusnezov N, et al. The effect of operative technique on ulnar nerve strain following surgery for cubital tunnel syndrome. Hand (N Y). 2015;10(4):707-711. doi: 10.1007/s11552-015-9770-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ogata K, Shimon S, Owen J, et al. Effects of compression and revascularization on ulnar nerve function. J Hand Surg. 1991;16:104-108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Song JW, Chung KC, Prosser LA. Treatment of ulnar neuropathy at the elbow: cost-utility analysis. J Hand Surg Am. 2012;37(8):1617.e3-1629.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2012.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chung KC. Treatment of ulnar nerve compression at the elbow. J Hand Surg. 2008;33: 1625-1627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Novak CB, Mackinnon SE. Selection of operative procedures for cubital tunnel syndrome. Hand (N Y). 2009;4:50-54. doi: 10.1007/s11552-008-9133-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]