Abstract

Few data exist on palliative care for trauma and acute care surgery patients. This pilot study evaluated family perceptions and experiences around palliative care in a surgical intensive care unit (SICU) via mixed methods interviews conducted from February 1, 2020, to March 5, 2020, with 5 families of patients in the SICU. Families emphasized the importance of clear, honest communication, and inclusiveness in decision-making. Many interviewees were unable to recall whether goals-of-care discussions had occurred, and most lacked understanding of the patients’ illnesses. This study highlights the significance of frequent communication and goals-of-care discussions in the SICU.

Keywords: communication, end-of-life care, qualitative methods, team communication

Introduction

The culture of medicine in Western society promotes aggressive care until a patient’s death, which can lead to interventions that are discordant with patients’ wishes, high health care costs, and invasive treatments (1 –3). Although palliative care has been traditionally used for chronically ill medical intensive care unit patients rather than surgical intensive care unit (SICU) patients, studies suggest that early implementation of palliative care in the SICU can better align treatments with patient needs and improve communication, length of stay, and physical and emotional well-being without increasing mortality (1,4 –9). Given recent integration of a palliative care initiative in our institution’s SICU involving improved documentation of health care decision-makers and the initiation of goals-of-care (GOC) discussions within 72 hours, the purpose of this study was to evaluate family perceptions of communication and palliative care in our SICU, as well as examine general care and communication preferences.

Methods

This pilot study was conducted from February 1, 2020, to March 5, 2020, at the University of North Carolina (UNC), a tertiary hospital with a 16-bed, closed unit SICU. Rounds are multidisciplinary and families are invited to participate. Primary palliative care (palliative care by SICU providers who have undergone at least 3 training sessions) and specialty palliative care consultants are both utilized.

The study used a mixed methods approach with interviews to evaluate families’ experiences in terms of palliative care, understanding of patient’s diagnoses and care options, perceived quality of patient–doctor communication, the effectiveness of GOC discussions, and preferences on educational materials. The study population consisted of 5 families of SICU patients whose primary diagnoses were trauma or acute care surgery. Due to coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), the sample size was limited. All 5 families who were purposefully recruited by the SICU staff agreed to participate. We excluded families who were not felt to be willing or emotionally able to engage (n = 7/94), families of patients who had Charlson Comorbidity Indices of <3 (n = 64/94), or families of patients who remained in the SICU for <72 hours (n = 46/94). After obtaining written informed consent, private interviews were conducted in person by a trained interviewer who was not part of the care team. Interviews were recorded, transcribed, and manually coded. Chart review was also conducted for patient age, sex, and use of GOC discussions. Goals-of-care was defined for the families as discussions involving code status, decisions about specific treatments and intensity of care, health care decision-makers, and plans for future care. For data analysis, the grounded theory (Glaser) methodology was used (10). Descriptive statistics were performed in Microsoft Excel. This study was approved by the institutional review board of UNC (IRB# 19-522).

Results

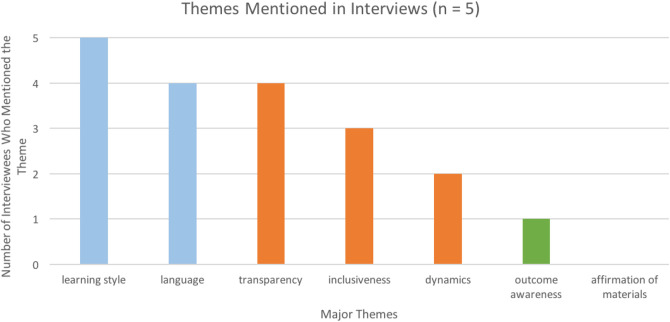

Five families were interviewed. The median patient age was 61 years (range 19-89) and 80% were male. The familial relation to the patient included 1 (20%) sibling, 1 (20%) child, 1 (20%) spouse, and 2 (40%) parents. Data were categorized into 3 primary themes related to palliative care in the SICU based on responses: communication, team performance, and family awareness, with subthemes explored below (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Frequency of all identified themes key: blue = communication themes, orange = team performance themes, and green = family awareness themes.

Communication: Learning Style

Participants unanimously mentioned learning style in terms of the resources they would find most helpful. Three participants were verbal learners, while 2 were visual learners. One interviewee who mentioned previous hospital experiences appreciated having “written materials that say what to expect when you get home, what to expect each day, getting worse is sometimes normal…. ” Speaking with a doctor or nurse (100%), speaking with a social worker (100%), and written materials (60%) were the top 3 preferred modes of information delivery.

Communication: Language/Medical Jargon

A majority of participants (60%) spoke about the importance of language in family–doctor interactions and of receiving “easy to understand explanations that limit medical jargon.”

Team Performance: Transparency

Eighty percent of participants mentioned the need for transparency with honest, straightforward answers from physicians being the priority. “It is important being open to any question, and if they don’t know, they find out. They aren’t afraid to say, ‘I don’t know, but I’ll come back with the answer.’”

One participant expressed dissatisfaction with receiving patient updates that were delivered in an overly grim manner: “It was like they were building for a story where the other shoe was going to drop. We would have been served well by ‘everything’s fine’ and then you walk through the details…as opposed to the suspense of waiting.”

Team Performance: Dynamics

Two participants cited the ICU team’s collaborative dynamics as a positive. The balanced hierarchy among the care team made one interviewee feel more secure: “The communication between the doctors and nurses flows back and forth both ways. One of the doctors came in after the first night we were here…and it was nice that they [the nurses who had been at bedside all night] gave a little push back of what to do, very respectfully, but they were colleagues and equals.”

Team Performance: Inclusiveness

Forty percent of participants mentioned that the inclusion of family in rounds gave the families a sense of reassurance and control. They felt more confident in asking questions and intervening when they felt uncomfortable with a decision. One comment that was echoed: “I have felt almost like a part of the medical team. At every round that has occurred, if I’m not standing in that circle, they ask me to come.”

One interviewee said that he experienced a gap in updates because he came to the hospital a few days later than his brother. This interviewee subsequently did not receive all the same information from the doctors, highlighting the need for continued updates and discussions.

Family Awareness: Outcome Awareness

Only one participant communicated that she understood the medical state and prognosis of her family member, and she was a retired nurse. When asked if they could explain the medical state of their family member, the 4 other interviewees were unable to.

Family Awareness: Affirmation of Provided Materials

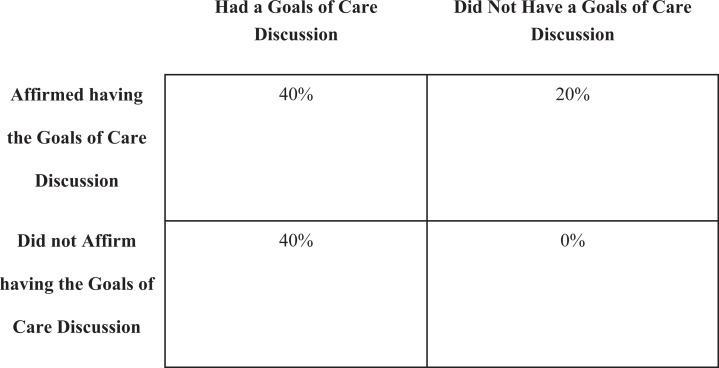

When asked if they had been offered any resources on palliative care or ICU care, all 5 participants reported that they had not. Based on Advanced Care Planning notes, 80% of interviewees had participated in a GOC discussion. However, only 40% of interviewees correctly understood that they had been part of a GOC conversation, while 40% reported not having had a GOC discussion when they actually had, and 20% reported having a GOC discussion when they had not (Figure 2). Two of the families had experienced specialty palliative consultation, with one family correctly identifying that they had had a GOC discussion and one reporting they had not.

Figure 2.

Comparison of interviewees’ awareness of goals-of-care discussion.

Discussion

There are limited studies on palliative care in the SICU (1,11 –13). We discovered that families appreciate inclusion on rounds (promoting empowerment), simple communication, honesty, and transparency regarding their loved one’s medical status and care. Education materials were considered more useful when aligned with the interviewees’ learning styles.

Family members with a loved one admitted to the SICU are in a vulnerable and stressful situation. It is crucial for these relatives to receive honest, straightforward language to guide them through the process. Families prefer physicians not to “sugar coat” their words but also want to hear “everything is fine” early on if that is the case. They want a general idea of the patient’s status or condition relayed early in the conversation, followed by the details. Although it is not possible to individually update multiple family members because of time constraints, large families with multiple members appreciate inclusion in rounds, group family meetings, and GOC discussions.

Families that were the most informed about their loved ones’ medical condition expressed the most satisfaction with the SICU staff’s communication. However, most participants did not understand the medical situation and many of the interviewees did not think they had participated in a GOC discussion when in fact they had. The majority of participants were not health professionals and were in a stressed state, which likely contributed to their lack of understanding or acceptance of patient prognosis and care needs. One study has shown that patients often only remember approximately 20% of what a physician tells them (14). These findings highlight the need to have multiple, repeat family meetings to improve understanding, disseminate updates to multiple people at once, and clarify GOC as the patients’ status changes. Moving forward, we will continue to include families in rounds but endeavor to provide written education materials, more frequent verbal updates and recurring GOC discussions, and train providers on limiting medical jargon and communication strategies.

Limitations

The sample was limited to 5 participants. There were no attempts to recruit based on gender, age, race, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, education level, or language preference. However, interviewees were selected by staff via convenience sampling to reduce family distress, leading to selection bias as emotionally distressed families might provide some of the most relevant information. All were English speaking. Consequently, the results are not fully generalizable. Lastly, interviewees may not have been able to recall important details or may have responded in a socially favorable way. Families acting as gatekeepers of information can lead to bias.

Acknowledgments

The authors appreciate the families who allowed us to interview them during a vulnerable time, the entire UNC Institute for Healthcare Quality Improvement team for their support, and the hard work of the SICU staff in their efforts to improve communication in the SICU.

Authors’ Note: This study was approved by the UNC Institutional Review Board (IRB# 19-522). All procedures in this study were conducted in accordance with the UNC Institutional Review Board (IRB# 19-522) approved protocols. Written informed consent was obtained from a legally authorized representative(s) for anonymized patient information to be published in this article.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Trista Reid, MD, MPH  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6619-2880

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6619-2880

References

- 1. Rivet EB, Del Fabbro E, Ferrada P. Palliative care assessment in the surgical and trauma intensive care unit. JAMA Surg. 2018;153:280–1. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2017.5077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lilley EJ, Cooper Z, Schwarze ML, Mosenthal AC. Palliative care in surgery: defining the research priorities. Ann Surg. 2018;267:66–72. doi:10.1097/SLA.0000000000002253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cassell J, Buchman TG, Streat S, Stewart RM, Buchman TG. Surgeons, intensivists, and the covenant of care: administrative models and values affecting care at the end of life. Crit Care Med. 2003;31:1263–70. doi:10.1097/01.CCM.0000059318.96393.14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hamel MB, Goldman L, Teno J, Lynn J, Davis RB, Harrell FE, Jr, et al. Identification of comatose patients at high risk for death or severe disability. SUPPORT investigators. understand prognoses and preferences for outcomes and risks of treatments. JAMA. 1995;273:1842–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Toevs CC. Palliative medicine in the surgical intensive care unit and trauma. Anesthesiol Clin. 2012;30:29–35. doi:10.1016/j.anclin.2011.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lilly CM, De Meo DL, Sonna LA, Haley KJ, Massaro AF, Wallace RF, et al. An intensive communication intervention for the critically ill. Am J Med. 2000;109:469–75. doi:10.1016/s0002-9343(00)00524-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Norton SA, Hogan LA, Holloway RG, Temkin-Greener H, Buckley MJ, Quill TE. Proactive palliative care in the medical intensive care unit: effects on length of stay for selected high-risk patients. Crit Care Med. 2007;35:1530–5. doi:10.1097/01.CCM.0000266533.06543.0C [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mosenthal AC. Palliative care in the surgical ICU. Surg Clin North Am. 2005;85:303–13. doi:10.1016/j.suc.2005.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lilley EJ, Khan KT, Johnston FM, Berlin A, Bader AM, Mosenthal A, et al. Palliative care interventions for surgical patients: a systematic review. JAMA Surg. 2016;151:172–83. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2015.3625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Glaser B. The constant comparative method of qualitative analysis. Social Problems. 1965;12:436–45. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mosenthal AC, Weissman DE, Curtis JR, Hays RM, Lustbader DR, Mulkerin C, et al. Integrating palliative care in the surgical and trauma intensive care unit: a report from the improving palliative care in the intensive care unit (IPAL-ICU) project advisory board and the center to advance palliative care. Crit Care Med. 2012;40:1199–206. doi:10.1097/CCM.0b013e31823bc8e7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Finkelstein M, Goldstein NE, Horton JR, Eshak D, Lee EJ, Kohli-Seth R. Developing triggers for the surgical intensive care unit for palliative care integration. J Crit Care. 2016;35:7–11. doi:10.1016/j.jcrc.2016.04.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bradley CT, Brasel KJ. Developing guidelines that identify patients who would benefit from palliative care services in the surgical intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2009;37:946–50. doi:10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181968f68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kessels RP. Patients’ memory for medical information. J R Soc Med. 2003;96:219–22. doi:10.1258/jrsm.96.5.219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]