SUMMARY

Objective

The incidence of papillary thyroid carcinoma (PTC) has increased in recent years and its treatment remains controversial. The objective of this study is to identify clinicopathological predictive factors of tumour recurrence.

Methods

We retrospectively analysed 4,085 patients who underwent thyroidectomy for PTC from 1996 to 2015. Patients were stratified according to American Thyroid Association (ATA) risk categories and clinicopathological features were evaluated to identify independent factors for recurrence.

Results

After a mean follow-up of 58.7 (range 3-256.5) months, tumour recurrence was diagnosed in 176 (4.3%) patients, mostly in lymph nodes. Distant metastasis occurred in 18 patients (0.4%). There were 3 (0.1%) cancer-related deaths. Multivariate analysis showed that tumour size >10 mm, multifocality, extrathyroidal extension and lymph node metastasis (all, P < 0.001) were independent risk factors for recurrence. Further, recurrence was identified in 1.6% of the ATA low-risk, 7.4% of the intermediate-risk and 22.7% of the high-risk patients (P < 0.001).

Conclusions

In PTC patients, tumour size >10 mm, multifocality, extrathyroidal extension and presence of lymph node metastasis as well as the ATA recurrence staging system effectively predict recurrence.

KEY WORDS: thyroid, papillary carcinoma, recurrence, survival

RIASSUNTO

Obiettivo

L’incidenza del carcinoma papillare tiroideo (PTC) è aumentata negli ultimi anni e il suo trattamento rimane controverso. L’obiettivo di questo studio è identificare i fattori predittivi clinicopatologici di recidiva tumorale.

Metodi

Abbiamo analizzato retrospettivamente 4.085 pazienti sottoposti a tiroidectomia per PTC dal 1996 al 2015. I pazienti sono stati stratificati in base alle categorie di rischio dell’American Thyroid Association (ATA) e le caratteristiche clinicopatologiche sono state valutate per identificare fattori indipendenti di recidiva.

Risultati

Dopo un follow-up medio di 58,7 (range, 3-256,5) mesi, la recidiva del tumore è stata diagnosticata in 176 pazienti (4,3%), principalmente nei linfonodi. Metastasi a distanza si sono verificate in 18 pazienti (0,4%). Ci sono stati 3 (0,1%) decessi correlati al cancro. L’analisi multivariata ha mostrato che le dimensioni del tumore > 10 mm, la multifocalità, l’estensione extratiroidea e le metastasi linfonodali (tutti, P < 0,001) erano fattori di rischio indipendenti per la recidiva. Inoltre, la recidiva è stata identificata nell’1,6% dei pazienti ATA a basso rischio, nel 7,4% dei pazienti a rischio intermedio e nel 22,7% dei pazienti ad alto rischio (P < 0,001).

Conclusioni

Nei pazienti con PTC, la dimensione del tumore > 10 mm, la multifocalità, l’estensione extratiroidea e la presenza di metastasi linfonodali, nonché il sistema di stadiazione delle recidive ATA, predicono efficacemente la recidiva.

PAROLE CHIAVE: tiroide, carcinoma papillare, recidiva, sopravvivenza

Introduction

The incidence of thyroid cancer is increasing worldwide, mainly due to the greater number of papillary thyroid carcinomas (PTC) incidentally discovered after the widespread use of ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration biopsy in patients with suspected thyroid diseases 1. Excellent outcomes following therapy of PTC have been demonstrated, with 10-year survival rates of 93% 2. However, despite the favourable long-term prognosis, locoregional recurrences have been described in up to 28% of patients 3.

There is no consensus regarding the natural history of PTC and treatment options range from observation to total thyroidectomy and neck lymph node dissection followed by radioactive iodine (RAI) ablation 4.

The risk of recurrence in PTC can be estimated based upon selected clinicopathologic features such as the presence of extrathyroidal extension, aggressive histologies, vascular invasion, regional metastases, or high levels of postoperative serum thyroglobulin suggestive of distant metastases. The 2009 ATA guidelines for the management of thyroid cancer proposed a system to estimate the risk of relapse of differentiated thyroid cancer based upon these clinicopathologic findings 5. Additional prognostic variables as extent of lymph node involvement and BRAF mutation profile were included in an updated version of the 2015 ATA risk stratification system 6 (Tab. I). However, these additional variables have not been rigourously assessed.

Table I.

Initial American Thyroid Association risk of recurrence classification.

|

Low risk (all the following) |

No local or distant metastases All macroscopic tumour has been resected No invasion of locoregional tissues Tumour does not have aggressive histology (e.g.: tall cell, insular, columnar cell carcinoma, Hurthle cell carcinoma, follicular thyroid cancer) No vascular invasion No 131I uptake outside the thyroid bed on the post-treatment scan, if done Clinical N0 or ≤ 5 pathologic N1 micrometastases (< 0.2 cm)* Intrathyroidal, encapsulated follicular variant of papillary thyroid cancer* Intrathyroidal, well differentiated follicular thyroid cancer with capsular invasion and no or minimal (< 4 foci) vascular invasion* Intrathyroidal, papillary microcarcinoma, unifocal or multifocal, including BRAFV600E mutated (if known)* |

|

Intermediate risk (any of the following) |

Microscopic invasion into the perithyroidal soft tissues Cervical lymph node metastases or 131I uptake outside the thyroid bed on the post-treatment scan done after thyroid remnant ablation Tumour with aggressive histology or vascular invasion Papillary thyroid cancer with vascular invasion* Clinical N1 or > 5 pathologic N1 with all involved lymph nodes < 3 cm* Multifocal papillary microcarcinoma with extrathyroidal extension (ETE) and BRAFV600E mutated (if known)* |

|

High risk (any of the following) |

Macroscopic (gross ETE) invasion of tumour into the perithyroidal tissues Incomplete tumour resection Distant metastases Postoperative serum thyroglobulin suggestive of distant metastases* Pathologic N1 with any metastatic lymph node ≥ 3 cm* Follicular thyroid cancer with extensive vascular invasion (> 4 foci of vascular invasion)* |

* Additional prognostic variables included in the 2015 ATA risk stratification system.

The aim of this study was to review the characteristics of PTC at diagnosis in a single cancer centre retrospective cohort and to identify the clinical and pathological features associated with tumour recurrence. We also evaluated the 2009 ATA risk stratification system for prediction of cancer recurrence.

Materials and methods

Study population and treatment

After obtaining institutional review board approval, we retrospectively reviewed the medical records of 4,104 consecutive patients treated for papillary thyroid cancer (PTC) between January 1996 and December 2015. Only patients with a postoperative pathologic diagnosis of PTC were included and 19 patients were excluded due to concurrent thyroidal malignancies. Most patients had an initial total or subsequent completion thyroidectomy, based on patient preference and clinical criteria such as previous neck irradiation, hypothyroidism, familial predisposition or bilateral nodularity. Many physicians and patients chose bilateral thyroidectomies aiming to simplify follow-up. Therapeutic lymph node dissection was performed if clinical involvement was confirmed based on sonographic findings and intraoperative exploration of the neck compartments. Elective central neck dissection was performed in the presence of extrathyroidal extension. For patients who were pathologically confirmed to have high risk findings mainly extrathyroidal extension and cervical lymph node metastasis, routine 131I treatment was administered after withdrawal of hormone therapy for at least 4 weeks. Some patients received radioiodine (RAI) ablation with the purpose of facilitate follow-up or destroy foci of micrometastatic disease. Diagnostic scintigraphy was performed before 131I administration and 2-5 days later. Levels of thyroglobulin (tg), and anti-tg antibodies were measured postoperatively just before RAI. Most PTC patients received oral therapy with levothyroxine postoperatively, in attempt to prevent hypothyroidism or to suppress thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) based on risk assessment.

Follow-up

Patients were assessed every 3 months for the first year, every 6 months between the second and fifth years, and every 12 months thereafter at the discretion of the attending physician based on the risk of the individual patient. The follow-up visits included palpation of the neck, dosage of serum TSH, tg and anti-tg antibody levels, and ultrasound examination of the cervical lymph nodes. Disease recurrence was defined as the first clinical reappearance of tumour. It included all clinical events reported (local relapses, lymph node metastases, and distant metastases) and confirmed by imaging modalities, biopsy or surgery.

Prognostic parameters

Patient characteristics, surgery data, pathological features and postoperative clinical outcomes were retrieved from the medical charts. Pathological characteristics of thyroidectomy specimens included: tumour size, minor extrathyroidal extension (invasion of perithyroidal soft tissues or strap muscles) and gross extrathyroidal extension (invasion of subcutaneous soft tissues, recurrent laryngeal nerve, esophagus, trachea, larynx, carotid artery or mediastinal vessels), multifocality, aggressive histology (e.g.: tall cells, diffuse sclerosing and solid), pathologically confirmed neck lymph node metastasis, lympho-vascular invasion and chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis. Patients were classified according to 2009 ATA risk stratification system as low, intermediate or high risk for recurrence 5.

Statistical methods

The primary end point of the study was disease-free survival (DFS). Categorical variables were described by the frequency and number of each unique category. For continuous variables, results were reported as range, mean and standard deviation (SD). Patients were followed-up until death, recurrence or the last date the patient was known to be alive. Disease-free survival probabilities were estimated by the Kaplan-Meier technique including the log-rank test to compare recurrence. P-values < 0.05 were considered significant. Univariate analyses were performed separately for each of the variables using the Cox regression model. All parameters in univariate analysis were included in the multivariate survival model. The backward selection technique was conducted with a P-value of < 0.10 used to select variables to the final model. Next, potential independent prognostic factors of recurrence were defined. The Schoenfeld and scaled Schoenfeld residuals verified whether the proportional assumption of risks was valid for the final Cox multivariate regression model. All statistical analyses were performed using computer software Stata: version 16 (StataCorp LP, College Station, Texas).

Results

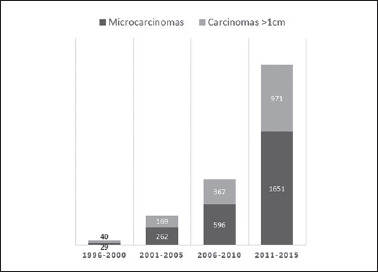

From January 1996 to December 2015, both the number of patients treated for papillary thyroid carcinoma (PTC) and the proportion of papillary thyroid microcarcinomas (PTMCs) increased over time: 42% (29 of 69 patients) in 1996-2000, 60.8% (262 of 431) in 2001-2005, 61.9% (596 of 963) in 2006-2010, and 63% (1,651 of 2,622) in 2011-2015 (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Temporal evolution of papillary thyroid carcinomas and proportion of microcarcinomas.

Clinicopathological features and risk stratification of the 4,085 patients included in this retrospective study are presented in Table II. Most patients (4,031-98.7%) underwent initial total thyroidectomy or completion thyroidectomy. Central lymph node dissection (level VI) was performed in 725 patients (17.7%), of whom 184 (4.5%) underwent concomitant lateral dissection (levels IIa, III, IV, Vb). Radioiodine administration (I131) was performed post-surgically in 2,569 patients (62.9%). Dose of iodine ranged from 22 to 463 mCi (mean: 137.5 mCi; SD: 42.2 mCi).

Table II.

Patients and tumour characteristics.

| Characteristics | No. patients | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 80.7% | 3,297 |

| Male | 19.3% | 788 | |

| Age (years): | Mean (SD) | 43.7 (13.1) | 4,085 |

| Median | 43 | ||

| Range | 7-88 | ||

| < 55 | 78.8% | 3,218 | |

| ≥ 55 | 21.2% | 867 | |

| Tumour size (mm): | Mean (SD) | 11.2 (9.9) | 4,085 |

| Median | 9 | ||

| Range | 0.2-140 | ||

| ≤ 10 mm | 62.1% | 2,538 | |

| > 10 mm | 37.9% | 1,547 | |

| Aggressive histology | 4% | 164 | |

| Multifocality | 33.5% | 1,370 | |

| Bilaterality | 22.7% | 928 | |

| Extrathyroidal extension | Minor | 15.7% | 641 |

| Gross | 5.1% | 209 | |

| Lympho-vascular invasion | 2% | 80 | |

| Lymph node metastasis | cN1 | 10% | 406 |

| pN1 | 17.2% | 703 | |

| Chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis | 33.2% | 1,356 | |

| ATA risk stratification category | Low-risk | 66.7% | 2,727 |

| Intermediate | 28.1% | 1,147 | |

| High | 5.2% | 211 |

After a mean follow-up of 58.7 months (range 3-256.5 months), tumour recurrence was diagnosed in 176 patients (4.3%), mostly in neck lymph nodes (see Fig. 2). Median time to recurrence was 56.8 months (range, 3-256.5 months; SD 40.2). There were 3 (0.1%) cancer-related deaths, all associated with progression of lung metastases. Forty-two patients (1%) died from other causes.

Figure 2.

Pattern of recurrence of papillary thyroid carcinoma.

Cox regression univariate analysis showed that male gender (P = 0.001), age < 55 years (P = 0.018), tumour size > 10 mm (P < 0.001), multifocality (P < 0.001), bilaterality (P < 0.001), extrathyroidal extension (P < 0.001), aggressive histologic variant (P = 0.004), lympho-vascular invasion (P < 0.001) and lymph node metastasis (P < 0.001) were significantly associated with tumour recurrence. In contrast, chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis did not affect disease-free survival rate (P = 0.287). Multivariate Cox regression analyses revealed that cancer recurrence was independently associated with tumour size > 10 mm [Hazard Ratio (HR) 1.68; 95% Confidence Interval (CI) 1.21-2.33; P = 0.002], multifocality (HR 1.48; CI 95% 1.1-2.01; P = 0.01), extrathyroidal extension (HR 1.57; CI 95% 1.14-2.16; P = 0.006) and lymph node metastasis (HR 4.74; 95% CI 3.41-6.61; P < 0.001) (Tab. III).

Table III.

Univariate and multivariate cancer-recurrence logistic regression analyses of PTC patients.

| Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P-value | HR (95% CI) | P-value | |

| Male gender | 1.79 (1.29-2.48) | 0.001 | ||

| Age < 55 years | 1.65 (1.09-2.51) | 0.018 | ||

| Tumour size > 10 mm | 2.91 (2.13-3.95) | < 0.001 | 1.68 (1.21-2.33) | 0.002 |

| Multifocality | 2.04 (1.51-2.74) | < 0.001 | 1.48 (1.10-2.01) | 0.01 |

| Bilaterality | 1.77 (1.30-2.42) | < 0.001 | ||

| Extrathyroidal extension | ||||

| Yes | 3.16 (2.35-4.26) | < 0.001 | 1.57 (1.14-2.16) | 0.006 |

| Minor | 1.71 (1.15-2.55) | 0.008 | ||

| Gross | 7.65 (5.39-10.86) | < 0.001 | ||

| Aggressive histology | 2.17 (1.28-3.69) | 0.004 | ||

| Lympho-vascular invasion | 3.07 (1.71-5.54) | < 0.001 | ||

| Lymph node metastasis | 6.87 (5.09-9.26) | < 0.001 | 4.74 (3.41-6.61) | < 0.001 |

| Chronic thyroiditis | 0.84 (0.61-1.16) | 0.287 | ||

HR and 95% CI estimated by COX regression models.

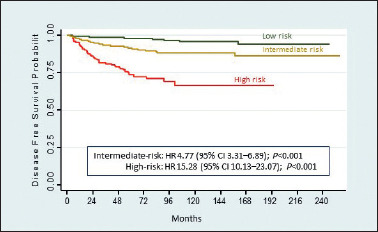

According to the 2009 ATA risk stratification system, patients were classified as low (66.7%), intermediate (28.1%) or high-risk (5.2%). Recurrence was observed in 43 (1.6%) of 2,727 low-risk patients, 85 (7.4%) of 1,147 intermediate-risk patients and in 48 (22.7%) of 211 high-risk patients. Five years disease-free survival probability was significantly lower in high-risk (73.1%) than in intermediate (90.8%) and low-risk (94.8%) patients (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meier recurrence estimates based on ATA risk categories.

Discussion

The incidence of papillary thyroid carcinoma (PTC) is rapidly rising, mostly due to increased presurgical diagnosis of incidental tumours 7. The prevalence of occult PTC in autopsy specimens is as high as 35.6% 8 and a similar high frequency of incidental PTC is seen in 7.2% of thyroid glands surgically resected for benign diseases 9. In our series, PTC increased significantly over the years, most been nonpalpable tumours incidentally diagnosed during neck radiologic procedures, such as ultrasonography or computed tomography performed during follow-up due to other cancers.

Studies analyzing PTC of all sizes described recurrence rates ranging from 6.6 to 28% 3,10. In our series, we found a low recurrence rate (4.3%), which is probably influenced by a high percentage (62.1%) of papillary thyroid microcarcinomas (PTMC) which are defined as carcinomas ≤ 1 cm. Recurrence was more frequently identified following thyroidectomy in patients with tumours >1 cm compared with PTMC (7.3% versus 2.5%). In a meta-analysis including 6,839 PTMC patients, Yi et al. found a recurrence rate of 2.8% 11, very similar to ours. As we know, PTMCs are less aggressive 12 and most thyroid nodules < 1 cm should not undergo fine-needle aspiration (FNA). Furthermore, most of our patients (83.9%) had asymptomatic or incidental PTC which demonstrate a much lower recurrence rate than symptomatic or nonincidental tumours 13.

Another possible reason for the low recurrence rate observed in this series is that most patients were submitted to total thyroidectomy, based on patient preference and clinical criteria such as previous neck irradiation, hypothyroidism, familial predisposition, bilateral nodularity or as a strategy to simplify follow-up. Some investigators favour total thyroidectomy, as an appropriate initial treatment for PTC, with the advantage of providing lower local recurrence because of removal of all potential foci in both lobes 14. However, salvage resection is quite effective in the few patients that recur and the surgical risks of two-stage procedure (lobectomy followed by completion thyroidectomy) are similar to those following bilateral thyroidectomy 6.

Due to a high incidence of multifocality and lymph node metastasis in the level VI, some authors recommend a total thyroidectomy and concomitant central lymph node dissection (CLND) in patients with clinically node negative (cN0) PTC to avoid reoperation or reduce locoregional recurrence 15. However, routine elective CLND might increase the risk of postoperative complications, especially permanent hypocalcaemia 16. In fact, microscopic nodal disease is rarely of clinical importance since it often remains quiescent or subsequent RAI administration ablates these occult foci. Based on 2015 ATA guidelines, prophylactic CLND must be indicated only in cN0 patients who have advanced primary tumours (T3 or T4) 6.

Most authors 17, but not all 18, agree that post thyroidectomy RAI is not beneficial in reducing cancer recurrence or mortality in low-risk and some intermediate-risk PTC patients. Since no long-term randomised trials were identified, conclusions are limited to observational studies. Most of our patients received RAI, with the purpose of destroying foci of micrometastatic disease in intermediate-high risk tumours or making follow-up easier by improving the sensitivity of thyroglobulin.

As expected, the majority of our PTC patients had recurrence in lymph nodes: 30.1% exclusively in level VI; 42% in lateral neck levels; and 17.6% in both, central and lateral compartment nodes. Distant metastases were seen in 18 (10.2%) of recurrent patients: 12 had lung metastases only, 4 had bone metastases only, and 2 had lung and bone metastases. Of note, all 3 cancer-related deaths were associated to progression of lung metastases.

Several clinicopathologic factors have been described in literature to predict recurrence of PTC 19: age, gender male, tumour diameter >1 cm, aggressive histological variants, multifocality, capsular invasion or absence of tumour capsule, extrathyroidal extension, lymph node metastases, proportion of metastasised and removed nodes at first operation > 0.5, extranodal extension, vascular invasion, mutated BRAF and TERT and non-incidental diagnosis. In a review of 5,768 PTC patients, Ito et al. found recurrence and cancer-specific death rates of 9.6% and 1%, respectively. Age older than 55 years, male gender, tumour size > 2 cm, extrathyroidal extension and clinical node metastasis were independent predictors of recurrence 20. Additionally, in a meta-analysis including 7,048 PTMC patients, Guo et al. found that male gender, extrathyroidal extension, lymph node metastasis, distant metastasis, tumour size greater than 2 cm and subtotal thyroidectomy were independent risk factors for recurrence.

Our univariate analysis showed that, except for chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis, all clinicopathologic factors analysed were associated with a risk of cancer recurrence. On multivariate analyses tumour size > 10 mm, multifocality, extrathyroidal extension and mainly presence of lymph node metastasis pathologically confirmed were independently associated with relapse of disease. Patients with lymph node metastases had almost 5 times greater risk of relapse than pN0 patients. These findings can be explained by the strong association between most of the clinical and pathological features analysed and the development of regional metastases. Accordingly, previous meta-analyses revealed that central lymph node metastasis in PTC patients are associated with male gender, younger age (< 45 years), larger tumour size, multifocality, extrathyroidal extension and lympho-vascular invasion, but not with chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis 21. In effect, Qu et al. found that lymphocytic thyroiditis resulted in decreased risk of lymph node metastasis 22. Additionally, So et al. in a systematic review of 18,741 patients, found that level VI lymph node metastases were the most important predictive factor for involvement of lymph nodes in the lateral compartment 23. Thus, the presence of lymph node metastases at initial diagnosis is the best predictive factor for the risk of locoregional recurrence in PTC patients.

Many histological variants of PTC have been described based on histological differences, mainly the characteristics of tumour cell nuclei. In our series, only 164 (4%) patients presented an aggressive histology, most with diffuse sclerosing (1.9%), solid (1.1%) or tall cell (0.7%) variants. We found that histological variants of PTC were associated with a more aggressive behaviour than the classic form and we agree with other authors 24 that patients with these variants should be treated intensively with total thyroidectomy and postoperative RAI, regardless of status of the regional lymph nodes.

The 2017 TNM (tumor, node, metastasis) staging system from American Joint Cancer Committee/Union Internationale Contre le Cancer (AJCC/UICC) is adequately used to predict disease-specific mortality 25. Since death is uncommon following management of PTC patients, we also use the American Thyroid Association (ATA) clinicopathologic staging system to provide initial estimates of risk of recurrence and thus improve clinical decision making. In our cancer center, the relatively high proportion of low-risk (66.7%) or intermediate-risk (28.1%) patients probably reflects the great number of PTMC incidentally discovered. Recurrence was identified in 1.6% of the low-risk, 7.4% of the intermediate-risk and 22.7% of the high-risk patients (P < 0.001). Consistent with previous publications, our data confirm that the risk of recurrence can be effectively predicted based on ATA staging system.

Some limitations of this retrospective study are mainly related to selection bias. Recommendations on treatment and intensity and frequency of follow-up visits and tests varied from patient to patient based on individual surgeons and patient preferences and not on an institutional protocol. This would lead to an increased diagnose of recurrent disease in intermediate to high-risk patients than the less rigorous testing paradigm often used in low-risk patients. Furthermore, important prognostic variables included in the updated version of the 2015 ATA risk stratification system, such as the number and dimension of lymph node metastases, were not assessed in this study. Finally, a median follow-up period of 58.7 months may be too short as some patients with a less aggressive disease may manifest clinically significant recurrence many years following initial therapy.

In summary, our data confirm that some clinicopathological factors such as tumour size > 10 mm, multifocality, extrathyroidal extension and mainly presence of lymph node metastasis at diagnosis, as well as ATA recurrence staging system, effectively predicts recurrence, thus providing valuable information that can help to individualise clinical management and follow-up for PTC patients.

Figures and tables

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the A. C. Camargo Cancer Center, Fundação Antonio Prudente, Sao Paulo, Brazil.

References

- 1.Wiltshire JJ, Drake TM, Uttley L, et al. Systematic review of trends in the incidence rates of thyroid cancer. Thyroid 2016;26:1541-1552. https://doi.org/10.1089/thy.2016.0100 10.1089/thy.2016.0100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hundahl SA, Fleming ID, Fremgen AM, et al. A National Cancer Data Base report on 53,856 cases of thyroid carcinoma treated in the U.S., 1985-1995. Cancer 1998;83:2638-2648. https://doi.org/10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19981215)83:12<2618::aid-cncr29>3.0.co;2-h [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grogan RH, Kaplan SP, Cao H, et al. A study of recurrence and death from papillary thyroid cancer with 27 years of median follow-up. Surgery 2013;154:1436-1446; discussion 1446-1447. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surg.2013.07.008 10.1016/j.surg.2013.07.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nabhan F, Ringel MD. Thyroid nodules and cancer management guidelines: comparisons and controversies. Endocr Relat Cancer 2017;24:R13-R26. https://doi.org/10.1530/ERC-16-0432 10.1530/ERC-16-0432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cooper DS, Doherty GM, Haugen BR, et al. American Thyroid Association (ATA) Guidelines Taskforce on Thyroid Nodules and Differentiated Thyroid Cancer Revised American Thyroid Association management guidelines for patients with thyroid nodules and differentiated thyroid cancer. Thyroid 2009;19:1167-1214. https://doi.org/10.1089/thy.2009.0110 10.1089/thy.2009.0110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haugen BR, Alexander EK, Bible KC, et al. 2015 American Thyroid Association Management Guidelines for adult patients with thyroid nodules and differentiated thyroid cancer: the American Thyroid Association Guidelines Task Force on thyroid nodules and differentiated thyroid cancer. Thyroid 2016;26:1-133. https://doi.org/10.1089/thy.2015.0020 10.1089/thy.2015.0020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kaliszewski K, Zubkiewicz-Kucharska A, Kiełb P, et al. Comparison of the prevalence of incidental and non-incidental papillary thyroid microcarcinoma during 2008-2016: a single-center experience. World J Surg Oncol 2018;16:202. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12957-018-1501-8 10.1186/s12957-018-1501-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harach HR, Franssila KO, Wasenius VM. Occult papillary carcinoma of the thyroid. A ‘normal’ finding in Finland. A systematic autopsy study. Cancer 1985;5:531-538. https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-0142(19850801)56:3<531::aid-cncr2820560321>3.0.co;2-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Matos PS, Ferreira AP, Ward LS. Prevalence of papillary microcarcinoma of the thyroid in Brazilian autopsy and surgical series. Endocr Pathol 2006;17:165-173. https://doi.org/10.1385/ep:17:2:165 10.1385/ep:17:2:165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim HJ, Sohn SY, Jang HW, et al. Multifocality, but not bilaterality, is a predictor of disease recurrence/persistence of papillary thyroid carcinoma. World J Surg 2013;37:376-384. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-012-1835-2 10.1007/s00268-012-1835-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yi D, Song P, Huang T, Tang X, et al. A meta-analysis on the effect of operation modes on the recurrence of papillary thyroid microcarcinoma. Oncotarget 2017;8:7148-7156. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.12698 10.18632/oncotarget.12698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zheng W, Wang X, Rui Z, et al. Clinical features and therapeutic outcomes of patients with papillary thyroid microcarcinomas and larger tumors. Nucl Med Commun 2019;40:477-483. https://doi.org/10.1097/MNM.0000000000000991 10.1097/MNM.0000000000000991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mehanna H, Al-Maqbili T, Carter B, et al. Differences in the recurrence and mortality outcomes rates of incidental and nonincidental papillary thyroid microcarcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 21 329 person-years of follow-up. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2014;99:2834-2843. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2013-2118 10.1210/jc.2013-2118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Macedo FI, Mittal VK. Total thyroidectomy versus lobectomy as initial operation for small unilateral papillary thyroid carcinoma: a meta-analysis. Surg Oncol 2015;24:117-122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.suronc.2015.04.005 10.1016/j.suronc.2015.04.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lang BH, Ng SH, Lau LL, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of prophylactic central neck dissection on short-term locoregional recurrence in papillary thyroid carcinoma after total thyroidectomy. Thyroid 2013;23:1087-1098. https://doi.org/10.1089/thy.2012.0608 10.1089/thy.2012.0608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ywata de Carvalho A, Chulam TC, Kowalski LP. Long-term results of observation vs prophylactic selective level VI neck dissection for papillary thyroid carcinoma at a cancer center. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2015;141:599-606. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoto.2015.0786 10.1001/jamaoto.2015.0786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sacks W, Fung CH, Chang JT, et al. The effectiveness of radioactive iodine for treatment of low-risk thyroid cancer: a systematic analysis of the peer-reviewed literature from 1966 to April 2008. Thyroid 2010;20:1235-1245. https://doi.org/10.1089/thy.2009.0455 10.1089/thy.2009.0455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ruel E, Thomas S, Dinan M, et al. Adjuvant radioactive iodine therapy is associated with improved survival for patients with intermediate-risk papillary thyroid cancer. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2015;100:1529-1536. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2014-4332 10.1210/jc.2014-4332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cipriani NA. Prognostic parameters in differentiated thyroid carcinomas. Surg Pathol Clin 2019;12:883-900. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.path.2019.07.001 10.1016/j.path.2019.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ito Y, Kudo T, Kobayashi K, et al. Prognostic factors for recurrence of papillary thyroid carcinoma in the lymph nodes, lung, and bone: analysis of 5,768 patients with average 10-year follow-up. World J Surg 2012;36:1274-1278. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-012-1423-5 10.1007/s00268-012-1423-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sun W, Lan X, Zhang H, et al. Risk factors for central lymph node metastasis in CN0 papillary thyroid carcinoma: a systematic review and meta-Analysis. PLoS One 2015;10:e0139021. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0139021 10.1371/journal.pone.0139021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Qu H, Sun GR, Liu Y, et al. Clinical risk factors for central lymph node metastasis in papillary thyroid carcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2015;83:124-132. https://doi.org/10.1111/cen.12583 10.1111/cen.12583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.So YK, Kim MJ, Kim S, et al. Lateral lymph node metastasis in papillary thyroid carcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis for prevalence, risk factors, and location. Int J Surg 2018;50:94-103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2017.12.029 10.1016/j.ijsu.2017.12.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kazaure HS, Roman SA, Sosa JA. Aggressive variants of papillary thyroid cancer: incidence, characteristics and predictors of survival among 43,738 patients. Ann Surg Oncol 2012;19:1874-1880. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-011-2129-x 10.1245/s10434-011-2129-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tuttle RM, Morris LF, Haughen BR, et al. Thyroid - differentiated and anaplastic carcinoma. Amin MB, editor. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. Eighth Edition. New York: Springer; 2017. p. 873. [Google Scholar]