Abstract

Objective:

Stress is linked to negative cardiovascular consequences and increases in depressive behaviors. Environmental enrichment (EE) involves exposure to novel items that provide physical and cognitive stimulation. EE has behavioral, cognitive, and neurobiological effects that may improve stress responses in humans and animal models. This study investigated the potential protective effects of EE on behavior and cardiovascular function in female prairie voles following a social stressor.

Methods:

Radiotelemetry transmitters were implanted into female prairie voles to measure heart rate (HR) and heart rate variability (HRV) throughout the study. All females were paired with a male partner for five days, followed by separation from their partner for five additional days, and a ten-day treatment period. Treatment consisted of either continued isolation, isolation with EE, or re-pairing with the partner (n=9 per group). Following treatment, animals were observed in the forced swim test (FST) for measures of stress coping behaviors.

Results:

Isolation elevated HR and reduced HRV relative to baseline for all groups [p < .001]. HR and HRV returned to baseline in the EE and re-paired groups, but not in the continued isolation group [p < .001]. Animals in the EE and re-paired groups displayed significantly lower immobility time [p < .001] and HR [p < .03] during the FST, with a shorter latency for HR to return to baseline levels following the FST, relative to the continued isolation group [p < .001].

Conclusions:

EE and re-pairing reversed the negative behavioral and cardiovascular consequences associated with social isolation.

Keywords: autonomic nervous system, cardiovascular, environmental enrichment, prairie vole, social isolation, stress

INTRODUCTION

Social stressors are associated with the development of physiological and psychological disorders (1–2). Evidence from human and animal studies indicates that low levels of social engagement increase the likelihood of depression, anxiety, disrupted cognition, sleep disturbances, and physiological disruptions (3–5). Further, both social isolation and loneliness are associated with cardiovascular dysfunction, including increased body mass index, blood pressure, cholesterol, and other indices associated with cardiovascular mortality (4,6). In contrast, social support, such as a hug from a romantic partner or encouragement during a public speaking task, has been shown to attenuate the rise in heart rate (HR) and blood pressure associated with acute stressors (7–8). Animal studies support the findings from human literature, indicating that experimentally-manipulated social isolation produce cardiovascular deficits and maladaptive behavioral responses related to depression and anxiety (1,9–11).

Taken together, these previous investigations indicate that social stressors, including the lack of social bonding, negatively influence behaviors and cardiovascular functioning, while social support serves a protective role. The present study uses the socially monogamous prairie vole to specifically investigate the influence of disrupting social bonds on behavioral and physiological function. Prairie voles are socially active rodents that form enduring pair bonds, engage in co-parenting of offspring, and live in extended family groups (12). Previous evidence demonstrates that the prairie vole is a valuable translational model for investigating the effects of social stressors on behaviors and other physiological processes (13). For example, disrupting established social bonds increases resting and stressor-induced HR, produces depression- and anxiety-related behaviors, and elevates neuroendocrine markers of stress (9–11,14–15).

The psychological and physiological effects of stress may be difficult to treat comprehensively and cost-effectively with pharmacotherapies. Some pharmacological treatments are associated with only limited improvements in behavioral and physiological consequences of stress (16–17). Cardiac medications, such as propranolol, reduce physiological symptoms of fear and anxiety in humans, but do not alter the psychological impact of such emotional events (16). Antidepressants, such as fluoxetine, diminish depressive behaviors in rats following a series of mild stressors, but do not protect against the cardiovascular consequences of the stressors (17).

An alternative to pharmacotherapy, which may improve both behavioral and cardiovascular consequences of stress, is environmental enrichment (EE). EE promotes positive behavioral and cognitive stimulation via activities that involve physical exercise, hand-eye coordination, and interactions with cognitive tasks or inanimate objects. Studies from both humans and animal models indicate that EE buffers stress responses and may protect against several cognitive conditions, stress-related disorders, developmental disorders, and effects of aging (18–24).

Additional studies have found EE to mitigate the effects of chronic stress, including social stressors (25–28). For example, EE in the form of nesting material, running wheels, tubes, and objects of varying shapes protects against maladaptive anxiety- and depression-relevant behaviors following a social defeat stressor in mice (25) and following long-term social isolation in prairie voles (26). EE may provide positive neural stimulation to prevent or reverse the effects of social deprivation, similar to other forms of social housing (23).

Given previous evidence suggesting several benefits of EE, this stimulation may protect against cardiovascular consequences of social stress in the prairie vole model. Therefore, the current study examines behavioral and cardiovascular consequences in female prairie voles resulting from the disruption of an established social bond with a male partner. The remediating effects of EE are compared to re-pairing with the previous male partner, which may be considered an ideal strategy for improving responses to social stressors. We hypothesize that both EE and re-pairing will reverse the negative cardiovascular consequences and reduce depressive behaviors associated with deprivation from a socially-bonded partner.

Methods

Animals

27 female (experimental animals) and 27 male prairie voles (partners), 60–90 days old, were used here. All animals were bred at Northern Illinois University. Subjects were removed from breeding pairs at 21 days of age, and housed in same-sex sibling pairs until the commencement of experimentation. Female voles were used to capitalize on the enhanced reaction to separation that is unique to females (30–31), and to improve our knowledge of female cardiovascular responses to stress. Only one animal from each sibling-pair was used for these experiments. Animals were allowed ad libitum access to food and water, maintained at a room temperature of 20–21°C and a relative humidity of 40–50%, under a standard 14:10 light/dark cycle (lights on at 0630). All protocols were approved by the Northern Illinois University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and followed National Institute of Health guidelines in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

General Study Design

A wireless radiotelemetry transmitter was implanted into each female prairie vole for the recording of continuous electrocardiogram (ECG) and activity variables throughout all phases of the study. Following a recovery period (10–12 days), animals underwent a baseline period of ECG and activity recordings (3 days). Each experimental animal was then removed from its home cage and paired with an unrelated male prairie vole of similar age and body weight (5 days). Following the pairing period, all female-male pairs were separated into isolated cages (5 days). Following this period, the experimental animals were randomly assigned to one of three treatment conditions, during which time ECG and activity were recorded (10 days): (a) isolation group: continued isolation from the male partner in a standard cage, (b) EE group: continued isolation from the male partner with the addition of EE, or (c) re-paired group: re-pairing with the male partner. A forced swim test (FST) was conducted following the treatment period. Handling, cage changing, and body weight measurements were matched among all groups.

Radiotelemetric Transmitter Implantation

Wireless radiofrequency transmitters (TA10ETA-F10; Data Sciences International, St. Paul, MN) were implanted intraperitoneally into female prairie voles under isoflurane anesthesia (Henry Schein, Dublin, OH) mixed with oxygen. The body of the transmitter was implanted into the intraperitoneal space using methods described previously, and wire leads were sutured to the muscle on the left and right of the heart using DII positioning (32). Each animal was housed for 5 days in a custom-designed divided cage with its respective female sibling, which permitted adequate healing of suture wounds (see 32). All females and their siblings were then returned to standard cages to recover for an additional 5–7 days. Animals were assessed for the following characteristics of recovery: (a) visible signs of eating and drinking, (b) adequate urination and defecation, (c) adequate activity level (approximately 2 counts per minute or higher), (d) adequate body temperature (approximately 37.5o C), and (e) stabilization of HR.

Electrocardiographic and Activity Recordings

ECG signals were collected via radiotelemetric recordings (sampling rate 5 kHz, 12-bit precision digitizing), continuously or at hourly intervals throughout all experimental protocols. Multiple segments of 1–5 minutes of stable, continuous data were used to evaluate HR, heart rate variability (HRV) and activity. Activity signals were quantified with the vendor software (256 Hz sampling rate), which measures the signal strength as the animal moves around the cage relative to a central location, and converts the information into counts per minute (cpm). Baseline resting cardiac parameters were derived from ECG data sampled during a period of minimal activity (≤ 5 cpm), during which time the animal may have been sitting, resting quietly, sleeping, or engaging in low-level movement. These resting baseline data were compared to data during the other phases of the experiment, including all possible activity states.

Quantification of Cardiac Variables

ECG signals were exported into a data file and examined manually with custom-designed software to ensure proper R-wave detection (Brain-Body Center, University of Illinois at Chicago, Chicago, IL; 33–34). HR was evaluated using the number of beats per minute (bpm). HRV was evaluated using the standard deviation of normal-to-normal intervals (SDNN index) and amplitude of respiratory sinus arrhythmia (RSA). SDNN index, hypothesized to represent the convergence of sympathetic and parasympathetic pathways on the heart, was calculated from the standard deviation of all R-R intervals (35).

The amplitude of RSA, hypothesized to represent the functional impact of myelinated vagal efferent pathways originating in the nucleus ambiguus on the sinoatrial node (36), was assessed with time-frequency procedures that have been validated in humans (33–34), applied to small mammals (37), modified for the prairie vole (3), and are appropriate for use during period of both low and high activity (36,38–39). The ECG data were analyzed using custom-designed software (33–34). Based on preliminary analyses confirming that the prairie vole expresses a spectral peak in the range of 1.0–4.0 Hz (40–41), R-R intervals were re-sampled at 20 Hz. To ensure that the assumption of stationarity was not violated, the data were de-trended with a 21-point cubic moving polynomial, which removed low frequency components that fell below 0.5 Hz. The residuals of this process were free of slow periodic and aperiodic processes. A band-pass filter was then applied to define RSA by extracting the variance in the HR spectrum that fell between 1.0 and 4.0 Hz.

Baseline Measurements

Following recovery from the surgical procedure, the baseline period consisted of recording ECG and activity variables via the radiotelemetry transmitter for 3 days, while the experimental female animal was housed with a female sibling in the home cage.

Social Bonding

Each female animal was separated from its respective siblings and paired with an unrelated male of approximately the same age and body weight, in a new, clean cage, for 5 days. This time period is sufficient for prairie voles to form a social bond (14–15).

Isolation

Following 5 days of social pairing, each female was separated from its respective male partner for 5 days, and housed individually without auditory, olfactory, or visual cues from the male partner. This isolation period is associated with dysregulation of behavior, autonomic function, and neural function (14–15).

Treatment

Following 5 days of isolation, each female was assigned to one of 3 treatment conditions for 10 days: (a) continued isolation: continued isolation from the male partner in a standard cage, without auditory, olfactory, or visual cues from the male partner (n = 9), (b) EE: continued isolation from the male partner, without auditory, olfactory, or visual cues from the male partner, with the addition of EE (n = 9), or (c) re-paired: re-paired with the previous male partner (n = 9).

Each animal in the continued isolation condition was moved into a new, clean standard cage; and remained isolated from its respective male partner, for the 10-day period. The standard cage was 12×18×28cm in size, consisting of food, water and bedding.

Each animal in the EE condition was moved into a new, clean cage. The EE cage was 25×45×60cm in size, consisting of food, water, bedding, and the following items: (a) a running wheel (4in diameter), (b) a wood block, (c) a rubber die, (d) a wood jack chew toy, (e) a mini straw hat, (f) a cardboard toilet paper roll, (g) a tin foil ball, (h) a piece of cotton nesting material, (i) a plastic bowl with small food pellets, (j) 2 plastic toys (1 hanging from cage top and 1 inside the cage), (k) 2 marbles, and (l) a plastic igloo house. Items were sanitized prior to placing them randomly inside the cage, and sanitized or replaced each time the cage was changed.

Each animal in the re-paired group was placed into a new, clean standard cage (12×18×28cm, with food, water and bedding) with its previous male partner, for the 10-day period.

Forced Swim Test

Following the treatment period, the FST was used as an operational index of helpless behavior (e.g., behavioral despair), which is hypothesized to represent a maladaptive response to the stressor of swimming (42). A clear, cylindrical Plexiglas tank (46cm height; 20cm diameter) was filled to a depth of 18cm with tap water (20–24°C). The animal was placed in the tank for 5 minutes. The tank was cleaned thoroughly and filled with clean water prior to testing each animal. Each animal was returned to its home cage (either continued isolation, EE, or re-paired conditions) immediately following the test, and allowed access to a heat lamp for 15 minutes. ECG and activity variables were recorded via the radiotelemetry transmitter continuously during the FST and intermittently for 24 hours following the test.

Behaviors during the FST were recorded using a digital video camera, and scored manually by two, experimentally-blinded, trained observers. Behaviors were defined as: (a) swimming: forelimb and hindlimb movements without breaking the surface of the water, (b) struggling: forelimbs breaking the surface of water, (c) climbing: attempts to climb the walls of the tank, and (d) immobility: no limb or body movements (floating) or using limbs solely to remain afloat without corresponding trunk movements. The duration of swimming, struggling, and climbing were summed to provide one index of active coping behaviors; the duration of immobility was used as the operational index of depressive (helpless/maladaptive) behavior (42).

Data Analyses

For ECG data, periods of ECG involving artifact due to animal movement or a poor signal-to-noise relationship were excluded from analysis. ECG data were analyzed with mixed-design analyses of variance (ANOVA), with group (continued isolation, EE, or re-paired) as the independent groups factor and time point (baseline, pairing, isolation, and treatment periods) as repeated measures factors, followed by a priori Student’s t-tests for hypothesis-driven comparisons.

For behavioral data, scores from two raters were averaged, and behaviors were analyzed using a single-factor ANOVA followed by an a priori Student’s t-test. HR and SDNN index prior to, during, and following the FST were analyzed using a mixed-design ANOVA, with group (continued isolation, EE, or re-paired) as the independent groups factor and time point [pre-stressor (prior to the FST), during the FST, and 3, 6, and 12 hours following the FST] as repeated measures factors, followed by a priori Student’s t-tests for hypothesis-driven comparisons.

A value of p < .05 was considered to be statistically significant. A Bonferroni correction was applied to multiple comparisons; the adjusted probability value, depending on the number of comparisons made, was used to determine whether the result was statistically significant.

Results

Resting Cardiac Function

HR

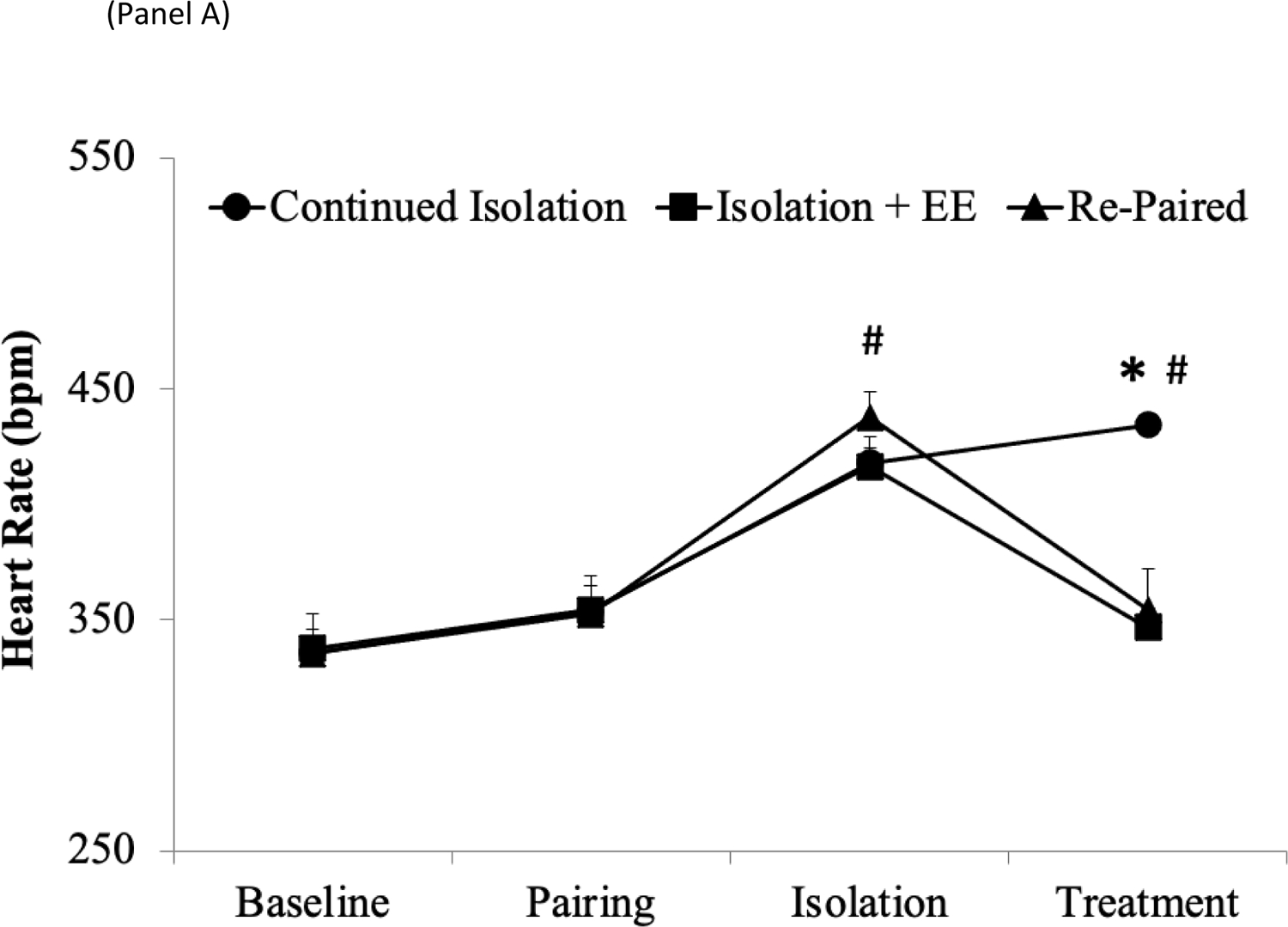

A mixed-design ANOVA for HR during the different phases of the experiment yielded a main effect of group [F(2,120) = 3.36, p < .038], a main effect of time [F(3,120) = 43.22, p < .001], and a group by time interaction [F(6,120) = 5.35, p < .001] (Figure 1A). Baseline HR values were similar across the 3 groups (continued isolation, 335.9 ± 10.0 bpm; EE, 337.6 ± 5.5 bpm; re-paired, 335.7 ± 17.3 bpm), and 5 days of pairing did not alter HR in any group relative to respective baseline values. 5 days of social isolation led to a significant elevation of HR to a similar extent in all groups, relative to baseline values; HR data were pooled among the 3 groups for the purpose of this comparison [t(52) = 11.36, p < .001].

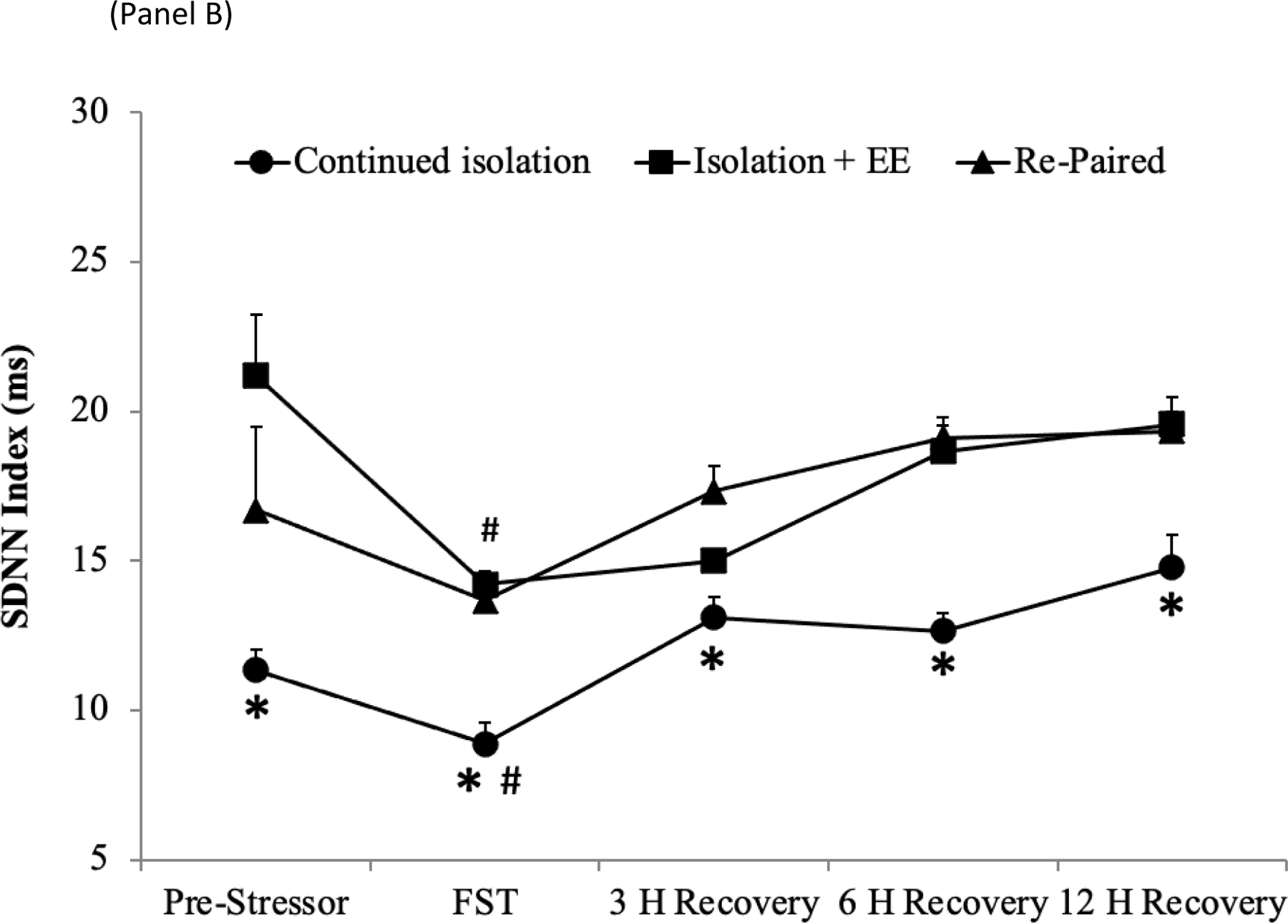

Figure 1:

Mean (+SEM) HR (Panel A), RSA amplitude (Panel B), and SDNN Index (Panel C) in prairie voles in the continued isolation, EE, and re-paired groups at baseline (prior to any manipulations), following 5 days of pairing with the male partner, following 5 days of isolation from the male partner, and following 10 days of treatment. *p < .05 vs. EE and re-paired groups at the same time point; #p < .05 vs. respective baseline value.

Follow-up pairwise comparisons using Student’s t-tests (with a Bonferroni correction) indicated that both EE and re-pairing with the male partner led to a significant reduction in HR, relative to continued isolation [EE vs. continued isolation, t(16) = 5.43, p < .001; re-pairing vs. continued isolation, t(16) = 6.44, p < .001], and these treatments reduced HR to a similar extent (EE vs. re-pairing, p > .05). At the end of the treatment period, both the EE and re-paired groups displayed HR values that were comparable to these groups’ respective baseline values (EE period vs. baseline, p > .05; re-pairing period vs. baseline, p > .05), whereas the HR of the continued isolation group remained significantly greater than this group’s respective baseline value [t(8) = 8.87, p < .001].

RSA

A mixed-design ANOVA for RSA amplitude during the different phases of the experiment yielded a main effect of time [F(3,120) = 18.79, p < .001] and a group by time interaction [F(6,120) = 3.67, p < .002] (Figure 1B). Baseline RSA amplitude values were similar across the 3 groups [continued isolation, 4.51 ± 0.20 ln(ms2); EE, 4.03 ± 0.15 ln(ms2); re-paired, 4.27 ± 0.38 ln(ms2)], and 5 days of pairing slightly (but non-significantly) reduced RSA amplitude in all groups to a similar extent, relative to respective baseline values. 5 days of social isolation led to a significant reduction in RSA amplitude to a similar extent in all groups, relative to baseline values; RSA amplitude data were pooled among the 3 groups for the purpose of this comparison [t(52) = 7.09, p < .001].

Follow-up pairwise comparisons using Student’s t-tests (with a Bonferroni correction) indicated that both EE and re-pairing led to a significant increase in RSA amplitude, relative to continued isolation [EE vs. continued isolation, t(16) = 6.51, p < .001; re-pairing vs. continued isolation, t(16) = 3.27, p < .001], and these treatments increased RSA amplitude to a similar extent (EE vs. re-pairing, p > .05). At the end of the treatment period, both the EE and re-paired groups displayed RSA amplitude values that were comparable to these groups’ respective baseline values (EE period vs. baseline, p >.05; re-pairing period vs. baseline, p > .05), whereas the RSA amplitude of the continued isolation group remained significantly lower than this group’s respective baseline value [t(8) = 6.64, p < .001].

SDNN Index

A mixed-design ANOVA for SDNN index during the different phases of the experiment yielded a main effect of time [F(3,120) = 9.00, p < .001] and a group by time interaction [F(6,120) = 3.30, p < .005] (Figure 1C). Baseline SDNN index values were similar across the 3 groups (continued isolation, 20.0 ± 1.76 ms; EE, 16.5 ± 2.4 ms; re-paired, 20.5 ± 4.2 ms), and 5 days of pairing did not alter SDNN index in any group relative to respective baseline values. 5 days of social isolation led to a significant reduction in SDNN index to a similar extent in all groups, relative to baseline values; SDNN index data were pooled among the 3 groups for the purpose of this comparison [t(52) = 4.55, p < .001].

Follow-up pairwise comparisons using Student’s t-tests (with a Bonferroni correction) indicated that both EE and re-pairing led to a significant increase in SDNN index, relative to continued isolation [EE vs. continued isolation, t(16) = 5.56, p < .001; re-pairing vs. continued isolation, t(16) = 2.25, p < .02], and these treatments increased SDNN index to a similar extent (EE vs. re-pairing, p > .05). However, at the end of the treatment period, only the EE group displayed an SDNN index values that was comparable its respective baseline values (EE period vs. baseline, p > .05), whereas the SDNN index of both the re-paired and continued isolation groups remained significantly lower than these groups’ respective baseline values [re-pairing period vs. baseline, t(8) = 2.88, p < .008; continued isolation period vs. baseline, t(8) = 4.85, p < .001].

Forced Swim Test

Behavior

A single-factor ANOVA for immobility duration during the FST yielded a significant main effect of treatment [F(2,26) = 9.13, p < .001] (Figure 2). Both the EE and re-paired groups displayed lower levels of immobility than the continued isolation group [EE vs. continued isolation, t(16) = 3.13, p < .006; re-pairing vs. continued isolation, t(16) = 3.24, p < .005]. The immobility level of the EE and re-paired groups did not differ significantly (p > .05).

Figure 2:

Mean (+SEM) duration of immobility during a 5-minute FST following 10 days of either continued isolation, EE, or re-pairing with the male partner. *p < .05 vs. EE and re-paired groups. Note: immobility and active coping behaviors (a combination of swimming, struggling, and climbing) are mutually-exclusive and exhaustive behavioral categories in the FST, therefore only the behavior of immobility is shown here. The remainder of 300 seconds is comprised of active coping behaviors.

HR

A mixed-design ANOVA for HR prior to, during, and following the FST yielded a main effect of group [F(2,120) = 45.27, p < .001], a main effect of time [F(4,120) = 19.82, p < .001], and a group by time interaction [F(8,120) = 2.30, p < .03] (Figure 3A). The HR of the EE and the re-paired groups did not differ significantly at any time point (p > .05 for all comparisons), therefore the data from these groups were pooled for the purpose of comparisons with the continued isolation group. The HR of these pooled treatment groups was significantly lower than that of the continued isolation group at every time point [pre-stressor, t(25) = 4.76, p < .001; during the FST, t(25) = 3.14, p < .002; 3 hours following the FST, t(25) = 7.48, p < .001; 6 hours following the FST, t(25) = 3.85, p < .001]; 12 hours following the FST, t(25) = 3.51, p < .001]. The HR of the pooled treatment groups was not significantly different from the respective pooled pre-stressor HR value by 3 hours following the FST (p > .05), whereas at this same time point the HR of the continued isolation group remained significantly higher than this group’s respective pre-stressor value [t(8) = 6.52, p < .001]. The HR of the continued isolation group was comparable to its respective pre-stressor value by 6 hours following the FST (p > .05).

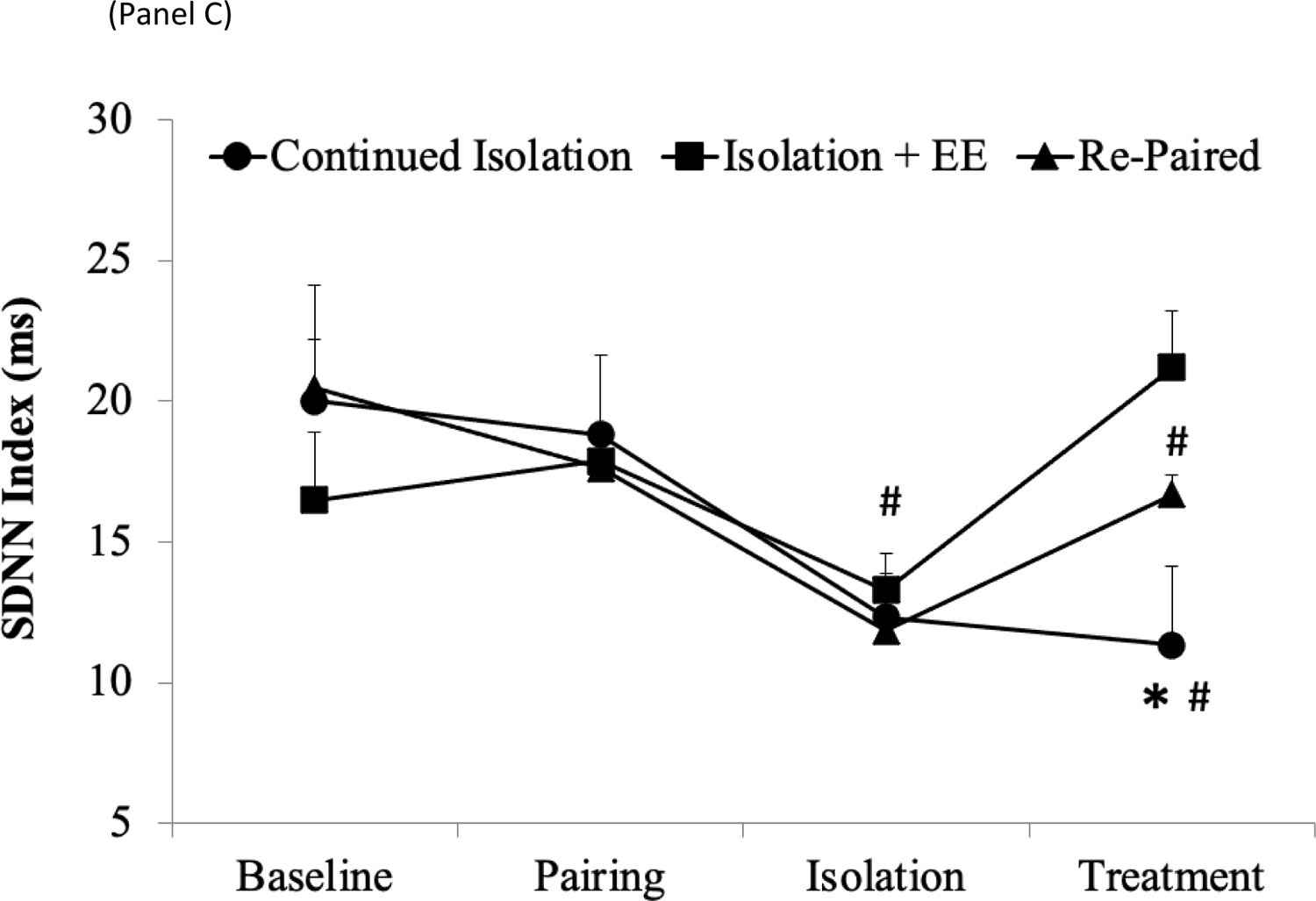

Figure 3:

Mean (+SEM) HR (Panel A) and SDNN Index (Panel B) prior to, during, and for 3, 6, and 12 hours after the FST, following 10 days of either continued isolation, EE, or re-pairing with the male partner. *p < .05 vs. EE and re-paired groups (pooled) at the same time point; #p < .05 vs. respective baseline value.

SDNN

A mixed-design ANOVA for SDNN index prior to, during, and following the FST yielded a main effect of group [F(2,120) = 37.82, p < .001], a main effect of time [F(4,120) = 11.13, p < .001], and a marginal group by time interaction [F(8,120) = 2.02, p = .05] (Figure 4B). The SDNN of the EE and re-paired groups did not differ significantly at any time point (p > .05 for all comparisons), therefore the data from these groups were pooled for the purposes of comparisons with the continued isolation group. The SDNN index of these pooled treatment groups was significantly greater than that of the continued isolation group at every time point [pre-stressor, t(25) = 2.95, p < .003; during the FST, t(25) = 8.00, p < .001; 3 hours following the FST, t(25) = 3.45, p < .001; 6 hours following the FST, t(25) = 7.21, p < .001]; 12 hours following the FST, t(25) = 4.24, p < .001]. All groups displayed SDNN index values that were comparable to respective pre-stressor values by 3 hours following the FST (p > .05 for both comparisons).

Discussion

Given previous evidence showing that EE improves cognition, behavior, and general health (22–23,27–28), the present study investigated whether EE would improve resting and stressor-induced cardiac function and depressive behaviors, in female prairie voles following disruption of a male-female social bond; and whether the effects of EE would be comparable to an ideal situation of re-pairing with a previous social partner. Both EE and re-pairing reversed HR and HRV responses to the social bond disruption, compared to continued isolation. A similar pattern of improvement in both behavior and cardiovascular responses was observed during the FST. These findings indicate that both EE and re-uniting animals with a previous partner protect against autonomic and behavioral consequences of social stress in the prairie vole model.

Consistent with previous research using the prairie vole model (9,11,14–15), the current findings demonstrate that disruption of a social bond between a male and female prairie vole contributes to physiological disturbances. Social deprivation from the male partner for 5 days resulted in an increase in resting HR, and a decrease in both SDNN index and RSA. Both EE and re-pairing with the previous male partner were effective at restoring HR and HRV to baseline levels. The stimulation provided by EE can reverse the negative autonomic effects of isolation, and suggest that the benefits of EE appear to be relevant to both sympathetic and parasympathetic regulation of the heart.

In addition to reversing HR and HRV changes, exposure to EE improved stressor-induced behavioral and cardiovascular responses associated with the FST. The FST was used as an acute stressor to measure depressive behaviors (helpless/maladaptive response) and physiological reactivity. The decreased immobility time in the FST displayed by the EE and re-paired groups may represent a more adaptive coping response to this stressor, consistent with evidence from previous EE studies in rats and prairie voles (27,43). The EE and re-paired groups also displayed attenuated cardiac reactivity to the FST (both in HR and SDNN responses) and a faster recovery time to pre-stressor levels, compared to the continued isolation group. The expedited ability of the cardiovascular system to recover from an acute stressor may represent increased physiological resilience to short-term stressors in the EE and re-paired groups.

Both EE and re-pairing animals with a previous social partner reversed the cardiac and behavioral consequences of social deprivation in the present study, which may suggest that EE and reuniting the animals are equally effective strategies for coping with social stress. EE and re-pairing may improve behavioral and cardiovascular function over social isolation, by fostering a more appropriate level of stimulation, similar to the stimulation that social species would encounter in their natural environment. However, given that reuniting with one’s previous social partner is not always possible (e.g., if a relationship dissolves or a partner dies), EE may be a useful alternative to consider for individuals who are struggling with the loss of an important social bond or other forms of social stress. The present study also demonstrates the benefits of EE at a time point that is translational to human conditions; in particular, EE was effective at reversing the negative cardiac consequences after a social bond disruption.

There are several possible mechanisms that may underlie the benefits of EE. It is possible that EE promotes cardiovascular and behavioral health via the voluntary exercise component of this paradigm, through peripheral and/or central mechanisms. Exercise increases vagal control of the heart, decreases body fat, reduces inflammatory cytokines, and reduces plaque buildup in arteries, all of which are associated with improvements in cardiovascular health and longevity (44–45). Exercise also promotes brain-derived neurotrophic factor in regions associated with cognition and behavior (e.g., hippocampus), providing benefits for cognitive functions, emotion, and stress reactivity (46–48). Further, exercise has anti-depressive benefits in patients with chronic illnesses, including cardiovascular disease (49), however the specific mechanisms that underlie these benefits are yet to be determined. Consistent with these findings, EE and physical exercise alone were shown to be comparably effective at protecting against depressive behaviors in socially isolated prairie voles (26).

Although exercise appears to be an important component of EE paradigms, the benefits of EE may be more complex than simply increased physical activity. Engaging in a variety of cognitive or physical activities, including reasoning tasks (e.g., crossword puzzles) or sensory activities (e.g., knitting, building with blocks, gardening), has been suggested to protect against the damaging effects of aging, stress, and cardiovascular disease, and may have benefits for psychological disorders such as attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and autism (18–19,21,50–51). Engaging in mentally stimulating activities also may be associated with higher baseline HRV and altered HRV reactivity to stress (52). A related hypothesis suggests that the mild stress associated with EE may encourage resilience or habituation towards more severe stressors in other contexts (25,53). For instance, the novelty associated with EE has been suggested to be slightly stressful (53–54), whereas over time EE has been found to lower baseline and stressor-induced HPA axis responses (20,27–29).

The current study design may limit conclusions regarding the specific mechanisms that underlie the benefits of EE. For instance, it was not possible to directly measure physical activity level in the current study. Future studies will benefit from including measures of activity, to allow for an evaluation of the exercise component of EE paradigms. It was also not possible to observe behaviors during different phases of the experimental timeline. Behavioral measures will provide valuable insight into the potential neurobiological and behavioral benefits of EE due to the complexity of activities available to the animal.

In conclusion, the present findings provide evidence for behavioral and cardiovascular benefits of EE following the disruption of an important social bond, similar to the improvements observed when an animal is reunited with its previous social partner. This study contributes to a growing body of literature examining the benefits of EE, and provides novel findings regarding autonomic nervous system improvements and reduced depressive-behaviors. The social nature of the prairie vole aids in the translation of these findings to human social experiences, highlighting the importance of environmental treatments for both behavioral and physiological responses to social stressors. Consequently, EE may be a useful environmental strategy to prevent or remediate negative consequences associated with the disruption of social bonds and other social stressors in humans. Continued investigation of the mechanisms through which EE is protective will contribute to the clinical relevance of this and related non-pharmacological strategies, to improve the quality of life for individuals experiencing negative consequences of social stressors.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank William Colburn and Amir Toghraee for assistance. This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH HL112350, AJG).

Source of Funding

Support provided by National Institutes of Health, HL112350.

Acronyms:

- ANOVA

analysis of variance

- ECG

electrocardiographic

- EE

environmental enrichment

- FST

forced swim test

- HR

heart rate

- HRV

heart rate variability

- RSA

respiratory sinus arrhythmia

- SDNN

standard deviation of normal-to-normal intervals

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: No conflict of interest declared by the authors.

References:

- 1.Watson SL, Shively CA, Kaplan JR, Line SW. Effects of chronic social separation on cardiovascular disease risk factors in female cynomolgus monkeys. JSM Atheroscler 1998;137:259–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Uchino BN. Social support and health: a review of physiological processes potentially underlying links to disease outcomes. J Behav Med 2006;29:377–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cacioppo S, Cacioppo JT. Decoding the invisible forces of social connections. Front Integr Neurosci 2012;6:1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Steptoe A, Shankar A, Demakakos P, Wardle J. Social isolation, loneliness, and all-cause mortality in older men and women. PNAS 2013;105:5797–5801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ramsay S, Ebrahim S, Whincup P, Papacosta O, Morris R, Lennon L, Wannamethee SG. Social engagement and the risk of cardiovascular disease mortality: results of a prospective population study of older men. Ann Epidemiol 2008;18:476–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hawkley LC, Cacioppo JT. Loneliness matters: a theoretical and empirical review of consequences and mechanisms. Ann Behav Med 2010;40:218–227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grewen KM, Anderson BJ, Girdler SS, Light KC. Warm partner contact is related to lower cardiovascular reactivity. Behav Med 2003;29:123–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Glynn LM, Christenfeld N, Gerin W. Gender, social support, and cardiovascular responses to stress. Psychosom Med 1999;61:234–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sun P, Smith AS, Lei K, Liu Y, Wang Z. Breaking bonds in male prairie vole: long-term effects on emotional and social behavior, physiology, and neurochemistry. Behav Brain Res 2014;265:22–31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grippo AJ, Lamb DG, Carter CS, Porges SW. Social isolation disrupts autonomic regulation of the heart and influences negative affective behaviors. Biol Psych 2007;62:1162–1170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Osako Y, Nobuhara R, Arai YP, Tanaka K, Young LJ, Nishihara M, Mitsui S, Yuri K. Partner loss in monogamous rodents: Modulation of pain and emotional behavior in male prairie voles. Psychosom Med 2017. September 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.DeVries AC. Interaction among social environment, the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, and behavior. Horm Behav 2002;41:405–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McGraw LA, Young LJ. The prairie vole: an emerging model organism for understanding the social brain. Trends Neurosci 2010;33:103–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McNeal N, Scotti MA, Wardwell J, Chandler DL, Bates SL, LaRocca M, Trahanas DM, Grippo AJ. Disruption of social bonds induces behavioral and physiological dysregulation in male and female prairie voles. Auton Neurosci 2014;180:9–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bosch OJ, Nair HP, Ahern TH, Neumann ID, Young LJ. The CRF system mediates increased passive stress-coping behavior following the loss of a bonded partner in a monogamous rodent. Neuropsychopharmacology 2009;34:1406–1415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Soeter M, Kindt M. High trait anxiety: a challenge for disrupting fear memory reconsolidation. PLoS ONE 2013;8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Grippo AJ, Beltz TG, Weiss RM, Johnson AK. The effects of chronic fluoxetine treatment on chronic mild stress-induced cardiovascular changes and anhedonia. Biol Psychiatry 2006;59:309–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Woo CC, Leon M. Environmental enrichment as an effective treatment for autism: a randomized controlled trial. Behav Neurosci 2013;127:487–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carlson MC, Parisi JM, Xia J, Xue QL, Rebok GW, Bandeen-Roche K, Fried LP. Lifestyle activities and memory: variety may be the spice of life. The women’s health and aging study II. J Int Neuropsychol Soc 2012;18:286–294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Novaes LS, Dos Santos NB, Batalhote RF, Malta MB, Camarini R, Scavone C, Munhoz CD. Environmental enrichment protects against stress-induced anxiety: role of glucocorticoid receptor, ERK, and CREB signaling in the basolateral amygdala. Neuropharmacology 2017;113:457–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Halperin JM, Healey DM. The influences of environmental enrichment, cognitive enhancement, and physical exercise on brain development: can we alter the developmental trajectory of ADHD? Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2011;35:621–634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hannan A Environmental enrichment and brain repair: harnessing the therapeutic effects of cognitive stimulation and physical activity to enhance experience-dependent plasticity. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol 2014;40:13–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tipyasang R, Kunwittaya S, Mukda S, Kotchabhakdi NJ, Kotchabhakdi N. Enriched environment attenuates changes in water-maze performance and BDNF level caused by prenatal alcohol exposure. EXCLI J 2014;13:536–547. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hamilton GF, Jablonski SA, Schiffino FL, St Cyr SA, Stanton ME, Klintsova AY. Exercise and environment as an intervention for neonatal alcohol effects on hippocampal adult neurogenesis and learning. Neuroscience 2014;265:274–290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lehmann ML, Herkenham M. Environmental enrichment confers stress resiliency to social defeat through infralimbic cortex-dependent neuroanatomical pathway. J Neurosci 2011;31:6159–6173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grippo AJ, Ihm E, Wardwell J, McNeal N, Scotti MA, Moenk DA, Chandler DL, LaRocca MA, Preihs K. The effects of environmental enrichment on depressive and anxiety-related behaviors in socially isolated prairie voles. Psychosom Med 2014;76:277–284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Belz EE, Kennell JS, Czambel RK, Rubin RT, Rhodes ME. Environmental enrichment lowers stress-responsive hormones in singly housed male and female rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 2003;76:481–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mesa-Gresa P, Ramos-Campos M, Redolat R. Corticosterone levels and behavioral changes induced by simultaneous exposure to chronic social stress and enriched environments in NMRI male mice. Physiol Behav 2016;158:6–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Garrido P, De Blas M, Ronzoni G, Cordero I, Antón M, Giné E, Santos A, Del Arco A, Segovia G, Mora F. Differential effects of environmental enrichment and isolation housing on the hormonal and neurochemical responses to stress in the prefrontal cortex of the adult rat: relationship to working and emotional memories. J Neural Transm 2013;120;829–843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grippo AJ, Cushing BS, Carter CS. Depression-like behavior and stressor-induced neuroendocrine activation in female prairie voles exposed to chronic isolation. Psychosom Med 2007;69:149–157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cushing BS, Carter CS. Peripheral pulses of oxytocin increase partner preferences in female, but not male, prairie voles. Horm Behav 2000;37:49–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Grippo AJ, Lamb DG, Carter CS, Porges, SW. Cardiac regulation in the socially monogamous prairie vole. Physiol Behav 2007;90:386–393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Porges SW. (1985). Patent No. 1985;4,510,944.

- 34.Porges SW, Bohrer R (1990). Analyses of periodic processes in psychophysiological research. In Cacioppo JT, Tassinary LG. Principles of psychophysiology: physical, social, and inferential elements (pp. 708–753). New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology, North American Society of Pacing and Electrophysiology. Heart rate variability: standards of measurement, physiological interpretation, and clinical use. Circulation 1996;93:1043–1065. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Porges SW. The polyvagal perspective. Biol Psych 2007;74:116–143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Youngue BG, McCabe PM, Porges SW, Rivera M, Kelley SL, Ackles PK. The effects of pharmacological manipulations that influence vagal control of the heart on heart period, heart-period variability and respiration in rats. Psychophysiology 1982;19:426–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Byrne EA, Fleg JL, Vaitkevicius PV, Wright J, Porges SW. Role of aerobic capacity and body mass index in the age-associated decline in heart rate variability. J Appl Physiol 1996;81:743–750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Houtveen JH, Rietveld S, de Geus EJ. Contribution of tonic vagal modulation of heart rate, central respiratory drive, respiratory depth, and respiratory frequency to respiratory sinus arrhythmia during mental stress and physical exercise. Psychophysiology 2002;39:427–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gehrmann J, Hammer PE, Maguire CT, Wakimoto H, Triedman JK, Berul CI. Phenotypic screening for heart rate variability in the mouse. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2000;279:H733–H740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ishii K, Kuwahara M, Tsubone H, Sugano S. Autonomic nervous function in mice and voles (Microtus arvalis): investigation by power spectral analysis of heart rate variability. Lab Animals 1996;30:359–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cryan JF, Valentino RF, Lucki I. Assessing substrates underlying the behavioral effects of antidepressants using the modified rat forced swim test. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2005;29:547–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Koh S, Magid R, Chung H, Stine CD, Wilson DN. Depressive behavior and selective down regulation of serotonin receptor expression after early-life seizures: reversal by environmental enrichment. Epilepsy Behavior 2007;10:26–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang YH, Wang SP, Tian ZJ, Zhang QJ, Li QX, Li YY, Yu XJ, Sun L, Li DL, Jia B, Liu BH, Zang WJ. Exercise benefits cardiovascular health in hyperlipidemia rats correlating with changes of the cardiac vagus nerve. Eur J Appl Physiol 2010;108:459–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.The Fifth Joint Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and Other Societies on Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in Clinical Practice. European Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice (version 2012). Eur Heart J 2012; 33: 1635–1701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kobilo T, Liu QR, Gandhi K, Mughal M, Shaham Y, van Praag H. Running is the neurogenic and neurotrophic stimulus in environmental enrichment. Learn Mem 2011;18:605–609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cotman CW, Berchtold NC. Exercise: a behavioral intervention to enhance brain health and plasticity. Trends Neurosci 2002;6:295–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bekinschtein P, Oomen CA, Saksida LM, Bussey TJ. Effects of environmental enrichment and voluntary exercise on neurogenesis, learning and memory, and pattern separation: BDNF as a critical variable? Semin Cell Dev Biol 2011;22:536–542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Herring MP, Puetz TW, O’Connor PJ, Dishman RK. Effect of exercise training on depressive symptoms among patients with a chronic illness: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Arch Intern Med 2012;172:101–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Larsen B, Christenfeld N. Cardiovascular disease and psychiatric comorbidity: the potential role of perseverative cognition. Cardiovasc Psychiatry Neurol 2009;2009:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Barnes DE, Alexopoulos GS, Lopez OL, Williamson JD, Yaffe K. Depressive symptoms, vascular disease, and mild cognitive impairment: findings from the Cardiovascular Health Study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2006;63:273–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lin F, Heffner K, Mapstone M, Chen DG, Porstenisson A. Frequency of mentally stimulating activities modifies the relationship between cardiovascular reactivity and executive function in old age. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2014;22:1210–1221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Crofton EJ, Zhang Y, Green TA. Inoculation stress hypothesis of environmental enrichment. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2015;49:19–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lyons DM, Parker KJ, Katz M, Schatzberg AF. Developmental cascades linking stress inoculation, arousal regulation, and resilience. Front Behav Neurosci 2009;3:1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]