Abstract

Background and Purpose: Cardiotoxicity is a well-known adverse effect of radiation therapy. Measurable abnormalities in the heart function indicate advanced and often irreversible heart damage. Therefore, early detection of cardiac toxicity is necessary to delay and alleviate the development of the disease. The present study investigated long-term serum proteome alterations following local heart irradiation using a mouse model with the aim to detect biomarkers of radiation-induced cardiac toxicity.

Materials and Methods: Serum samples from C57BL/6J mice were collected 20 weeks after local heart irradiation with 8 or 16 Gy X-ray; the controls were sham-irradiated. The samples were analyzed by quantitative proteomics based on data-independent acquisition mass spectrometry. The proteomics data were further investigated using bioinformatics and ELISA.

Results: The analysis showed radiation-induced changes in the level of several serum proteins involved in the acute phase response, inflammation, and cholesterol metabolism. We found significantly enhanced expression of proinflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, TGF-β, IL-1, and IL-6) in the serum of the irradiated mice. The level of free fatty acids, total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein (LDL), and oxidized LDL was increased, whereas that of high-density lipoprotein was decreased by irradiation.

Conclusions: This study provides information on systemic effects of heart irradiation. It elucidates a radiation fingerprint in the serum that may be used to elucidate adverse cardiac effects after radiation therapy.

Keywords: radiation therapy, proteomics, data-independent acquisition, inflammation, ionizing radiation, biomarker, radiation-induced heart disease, cardiac lipid metabolism

Introduction

It is, nowadays, commonly acknowledged that the exposure of the heart to ionizing radiation, as in radiation therapy for breast cancer, Hodgkin's disease, or other cancers of the chest, increases the risk of heart disease (1, 2). This has become a growing problem with the advancements in cancer therapy that have successfully reduced both mortality rates and the recurrence, expanding the life expectancy of the survivors (3, 4).

Manifestations of radiation-induced heart disease include pericarditis, pericardial fibrosis, diffuse myocardial fibrosis, coronary artery disease, microvascular damage, and stenosis of the valves (5, 6). Considering causal biological processes in the development of the disease, persistent inflammation and oxidative stress, fibrosis, and pre-mature endothelial senescence are thought to be salient (7–9). Recently, the role of mitochondrial dysfunction and related metabolic perturbations has become more and more evident (10–12).

Detecting cardiac toxicity by assessing left ventricular function often requires a large amount of myocardial damage, characteristic of irreversible heart injury (13, 14). There is increasing emphasis on the use of biomarkers to detect cardiotoxicity at a stage before it becomes irreversible.

The most important blood biomarkers of heart injury are cardiac troponins T (cTnT) and I (cTnI), heart proteins controlling the calcium-mediated interaction between actin and myosin filaments (15). While cTnT is expressed to a small extent in skeletal muscle, cTnI has been found only in the myocardium. A previous study by Skyttä et al. showed that cTnT levels increased during adjuvant whole-breast radiation therapy in one out of five patients. Moreover, the increase in cTnT release was positively associated with cardiac radiation dose and with minor changes in the left ventricular diastolic function (16). A sustained irreversible leakage of cardiac troponins to the blood stream is due to the degradation of the myofibrils after heart damage (17).

Since irradiation tends to stimulate inflammatory processes, C-reactive protein (CPR), an acute phase protein, could be an additional potential predictive marker of cardiotoxicity after irradiation. Increased CRP level was associated with the severity of radiation-induced cardiomyopathy after radiation therapy of lung or breast cancer (18). We have shown elevated levels of inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin (IL)-1, IL-6, and tissue necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) in serum after local cardiac irradiation in mice (19), but data on their role in the prediction of myocardial changes in clinical trials are lacking to date (20, 21).

Although cardiac troponins and CRP are established sensitive biomarkers of myocardial injury and inflammation, respectively, there is no specificity for radiation-associated heart disease. In fact, there are no biomarkers available to identify radiotherapy patients who are in the process of developing radiation-associated heart disease, although the current data suggest that certain blood biomarkers may be associated with myocardial dysfunction (20, 22, 23).

Proteomics represents a promising global technology to discover new types of biomarkers for radiation-induced cardiac injury (11, 24). However, identification and quantification of serum/plasma proteins remains an analytical challenge, mainly due to the dominance of albumins and immunoglobulins and the high dynamic range of protein abundances (25). This is particularly true for disease-specific biomarkers that are mainly low-abundance proteins (26, 27). The newly established quantitative proteomics technology based on the data-independent acquisition (DIA) mass spectrometry (MS) was introduced recently to overcome the limitation of previous approaches (26). The aim of this study was to identify biomarkers of cardiac toxicity in the serum proteome of mice after local heart irradiation by using DIA-MS.

Materials and Methods

Irradiation and Sample Preparation

Local heart irradiation was carried out on male C57BL/6J mice at the age of 8 weeks as previously described (28). Briefly, mice were irradiated with a single X-ray dose of 8 or 16 Gy locally to the heart (200 kV, 10 mA) (Gulmay, West Byfleet, UK). The age-matched control mice were sham irradiated. Mice were not anesthetized during irradiation but were held in a prone position in restraining jigs with the thorax fixed using adjustable hinges. The position and field size (9 × 13 mm2) of the heart was determined by pilot studies using soft X-rays; the rest of the body was shielded with a 2-mm-thick lead plate. With this beam size, 40% of the lung volume receives, by necessity, the full heart dose (29). Blood samples were collected from all mice by cardiac puncture after animals were sacrificed 20 weeks post-radiation. The serum was isolated and kept at −80°C for further analyses. All animal experiments were approved and licensed under Bavarian federal law (Certificate No. AZ 55.2-1-54-2532-114-2014). Altogether, 15 mice were used in this study, with five mice in each group.

Proteome Profiling

Serum protein concentrations were determined by Bradford assay, and 50 μg per sample was prepared using PreOmics' iST Kit (Preomics GmbH, Martinsried, Germany) according to manufacturers' specifications. After drying, the peptides were resuspended in 2% acetonitrile (ACN) and 0.5% trifluoroacetic acid. The HRM Calibration Kit (Biognosys, Schlieren, Switzerland) was added to all of the samples according to the manufacturer's instructions.

The MS data were acquired in DIA mode on a Q Exactive HF mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA). Samples were automatically loaded to the online coupled RSLC (Ultimate 3000, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.) HPLC system. A Nano-Trap column was used (300-μm inner diameter (ID) × 5 mm, packed with Acclaim PepMap100 C18, 5 μm, 100 Å from LC Packings, Sunnyvale, CA, USA, before separation by reversed-phase chromatography (Acquity UPLC M-Class HSS T3 Column 75 μm ID × 250 mm, 1.8 μm from Waters, Eschborn, Germany) at 40°C. Peptides were eluted from the column at 250 nl/min using increasing ACN concentration in 0.1% formic acid from 3 to 40% over a 45-min gradient.

The DIA method consisted of a survey scan from 300 to 1,500 m/z at 120,000 resolution and an automatic gain control (AGC) target of 3e6 or 120-ms maximum injection time. Fragmentation was performed via higher-energy collisional dissociation with a target value of 3e6 ions determined with predictive AGC. Precursor peptides were isolated with 17 variable windows spanning from 300 to 1,500 m/z at 30,000 resolution with an AGC target of 3e6 and automatic injection time. The normalized collision energy was 28, and the spectra were recorded in profile type.

Selected LC-MS/MS data encompassing 164 raw files were analyzed using Proteome Discoverer (Version 2.1, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.) using Byonic (Version 2.0, Proteinmetrics, San Carlos, CA, USA) search engine node maintaining 1% peptide and protein FDR threshold. The peptide spectral library was generated in Spectronaut (Version 10, Biognosys, Schlieren, Switzerland) with default settings using the Proteome Discoverer result file. Spectronaut was equipped with the Swiss-Prot mouse database (Release 2017.02, 16,869 sequences, www.uniprot.org) with a few spiked proteins (e.g., Biognosys iRT peptide sequences). The final spectral library generated in Spectronaut contained 10,525 protein groups and 322,041 peptide precursors. The DIA-MS data were analyzed using the Spectronaut 10 software applying default settings with the exception: quantification was limited to proteotypic peptides, data filtering was set to Q-value 25% percentile, summing-up peptide abundances. For this study, the proteins with a q-value <0.05 were considered as significantly differentially expressed.

Additional differential abundance testing was performed in Spectronaut as unpaired ratio based t-test on peptide level to identify the candidates' differential between the experimental groups (i) sham irradiation, (ii) 8-Gy irradiation, or (iii) 16-Gy irradiation.

Interaction and Signaling Network Analysis

The analyses of protein–protein interaction and signaling networks were performed by the software tools INGENUITY Pathway Analysis (IPA) (Qiagen, Inc., Hilden, Germany, https://www.qiagenbioinformatics.com/products/ingenuity-pathway-analysis) (30).

Serum Inflammatory Molecule Analysis

The expression levels of different mediators including TNF-α, TGF-β, monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 (MCP1), IL-1 α, IL-1 β, IL-6, IL-10, IL-12, interferon (IFN) gamma, granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (G-CSF), and granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) were measured using ELISA strip colorimetric kits #EA-1401, # EA-1051, and # EA-1131 (Signosis, Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Serum Lipid Profiling

The levels of circulating free fatty acids (ab65341), triglyceride (ab65336), total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein (LDL), and high-density lipoprotein (HDL) (ab65390), all from Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA, and oxidized low-density lipoprotein (oxLDL) (MBS2512757, MyBioSource, San Diego, CA, USA) were measured according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Statistical Analysis

The 3D principal component analysis (PCA) was performed by R (4.0.5) (https://www.R-project.org/) and the hierarchical clustering using the Heatmapper web server (http://www.heatmapper.ca/) (31). Student's t-test (unpaired) was used for proteomics and ELISA comparisons. The error bars were calculated as the standard error of the mean (SEM).

Data Availability

The mass spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE (32) partner repository with the dataset identifier PXD024446.

Results

Serum Proteome Alterations Following Local Heart Irradiation

The serum proteome of mice was analyzed 20 weeks in sham-irradiated and irradiated (8 and 16 Gy) mice using DIA-MS. The analysis identified and quantified 499 proteins (Supplementary Table 1). Among the quantified proteins, the expression of 42 and 59 proteins was significantly changed (q-value <0.05, identification by at least two unique peptides) at 8 and 16 Gy, respectively, suggesting a dose-dependent increase in the number of significantly deregulated proteins (Table 1). The majority of these proteins (76% at 8 Gy and 83% at 16 Gy) have been previously annotated as serum proteins based on the Plasma Proteome Database (PPD) (http://plasmaproteomedatabase.org/index.html).

Table 1.

Significantly deregulated serum proteins in heart-irradiated mice.

| # | Protein accession | Protein ID | Protein description | Total unique peptides | Ratio 8/0 Gy | Ratio 16/0 Gy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | P48410 | ABCD1 | ATP-binding cassette subfamily D member 1 | 20 | 0.712 | |

| 2 | P29699 | AHSG | Alpha-2-HS-glycoprotein | 12 | 0.989 | 1.043 |

| 3 | P05064 | ALDOA | Fructose-bisphosphate aldolase A | 48 | 0.435 | |

| 4 | Q91Y97 | ALDOB | Fructose-bisphosphate aldolase B | 5 | 0.476 | |

| 5 | P12246 | APCS | Serum amyloid P-component | 3 | 2.375 | |

| 6 | P09813 | APOA2 | Apolipoprotein A-II | 3 | 0.812 | |

| 7 | P06728 | APOA4 | Apolipoprotein A-IV | 28 | 0.891 | 0.993 |

| 8 | E9Q414 | APOB | Apolipoprotein B-100 | 16 | 1.301 | 1.271 |

| 9 | P34928 | APOC1 | Apolipoprotein C-I | 3 | 0.801 | |

| 10 | P08226 | APOE | Apolipoprotein E | 24 | 1.340 | |

| 11 | Q02105 | C1QC | Complement C1q subcomponent subunit C | 5 | 0.857 | |

| 12 | Q80X80 | C2CD2L | C2 domain-containing protein 2-like | 31 | 0.039 | |

| 13 | P01027 | C3 | Complement C3 | 99 | 1.153 | 0.895 |

| 14 | P01029 | C4B | Complement C4-B | 45 | 1.452 | 1.151 |

| 15 | P06684 | C5 | Complement C5 | 20 | 1.134 | |

| 16 | P55284 | CDH5 | Cadherin-5 | 27 | 1.468 | |

| 17 | P04186 | CFB | Complement factor B | 19 | 0.923 | |

| 18 | P06909 | CFH | Complement factor H | 45 | 1.234 | |

| 19 | Q61129 | CFI | Complement factor I | 8 | 0.870 | |

| 20 | P12960 | CNTN1 | Contactin-1 | 59 | 1.214 | |

| 21 | Q61147 | CP | Ceruloplasmin | 54 | 1.116 | |

| 22 | P09581 | CSF1R | Macrophage colony-stimulating factor 1 receptor | 5 | 1.178 | |

| 23 | P63037 | DNAJA1 | DnaJ homolog subfamily A member 1 | 26 | 0.258 | |

| 24 | Q61508 | ECM1 | Extracellular matrix protein 1 | 18 | 0.767 | 0.846 |

| 25 | Q01279 | EGFR | Epidermal growth factor receptor | 46 | 1.137 | |

| 26 | P19221 | F2 | Prothrombin | 26 | 0.972 | |

| 27 | Q9QXC1 | FETUB | Fetuin-B | 8 | 1.214 | |

| 28 | E9PV24 | FGA | Fibrinogen alpha chain | 30 | 1.435 | |

| 29 | P11276 | FN1 | Fibronectin | 145 | 1.008 | |

| 30 | P21614 | GC | Vitamin D-binding protein | 23 | 1.253 | |

| 31 | P13020 | GSN | Gelsolin | 44 | 0.902 | 0.987 |

| 32 | P01898 | H2-Q10 | H-2 class I, Q10 alpha chain | 11 | 1.212 | |

| 33 | P01942 | HBA | Hemoglobin subunit alpha | 18 | 1.467 | |

| 34 | P02088 | HBB-B1 | Hemoglobin subunit beta-1 | 19 | 1.460 | 1.309 |

| 35 | Q61646 | HP | Haptoglobin | 14 | 3.311 | |

| 36 | Q91X72 | HPX | Hemopexin | 24 | 1.328 | |

| 37 | P06330 | IG HEAVY C | Ig heavy chain V region AC38 205.12 | 3 | 1.116 | |

| 38 | P01864 | IGG | Ig gamma-2A chain C region secreted form | 4 | 1.310 | 1.849 |

| 39 | P01867 | IGH-3 | Ig gamma-2B chain C region | 9 | 1.821 | 2.659 |

| 40 | P01872 | IGHM | Ig mu chain C region | 16 | 1.585 | 1.696 |

| 41 | P01837 | IGK | Ig kappa chain C region | 5 | 1.242 | 1.514 |

| 42 | Q61702 | ITIH1 | Inter-alpha-trypsin inhibitor heavy chain H1 | 17 | 1.174 | |

| 43 | Q61703 | ITIH2 | Inter-alpha-trypsin inhibitor heavy chain H2 | 33 | 0.907 | |

| 44 | Q61704 | ITIH3 | Inter-alpha-trypsin inhibitor heavy chain H3 | 14 | 1.518 | 0.937 |

| 45 | A6X935 | ITIH4 | Inter alpha-trypsin inhibitor, heavy chain 4 | 23 | 1.632 | 0.993 |

| 46 | P04104 | KRT1 | Keratin, type II cytoskeletal 1 | 10 | 0.533 | |

| 47 | P08730 | KRT13 | Keratin, type I cytoskeletal 13 | 30 | 0.933 | |

| 48 | Q6NXH9 | KRT73 | Keratin, type II cytoskeletal 73 | 10 | 0.588 | |

| 49 | Q61233 | LCP1 | Plastin-2 | 44 | 0.672 | |

| 50 | P42703 | LIFR | Leukemia inhibitory factor receptor | 25 | 0.736 | 0.712 |

| 51 | Q80XG9 | LRRTM4 | Leucine-rich repeat transmembrane neuronal protein 4 | 9 | 0.751 | |

| 52 | P51885 | LUM | Lumican | 12 | 0.922 | |

| 53 | O09159 | MAN2B1 | Lysosomal alpha-mannosidase | 40 | 0.800 | |

| 54 | P04247 | MB | Myoglobin | 13 | 1.354 | |

| 55 | Q99KE1 | ME2 | NAD-dependent malic enzyme, mitochondrial | 37 | 0.751 | |

| 56 | P28665 | MUG1 | Murinoglobulin-1 | 63 | 0.877 | |

| 57 | P11589 | MUP2 | Major urinary protein 2 | 8 | 0.896 | |

| 58 | P97863 | NFIB | Nuclear factor 1 B-type | 21 | 0.358 | |

| 59 | O89084 | PDE4A | cAMP- 3′,5′-cyclic phosphodiesterase 4A | 21 | 0.718 | |

| 60 | P52480 | PKM | Pyruvate kinase PKM | 60 | 0.605 | |

| 61 | Q60963 | PLA2G7 | Platelet-activating factor acetylhydrolase | 18 | 1.110 | |

| 62 | P20918 | PLG | Plasminogen | 39 | 1.073 | |

| 63 | P55065 | PLTP | Phospholipid transfer protein | 12 | 1.102 | 1.420 |

| 64 | P52430 | PON1 | Serum paraoxonase/arylesterase 1 | 14 | 1.137 | |

| 65 | Q62009 | POSTN | Periostin | 39 | 1.183 | |

| 66 | Q61171 | PRDX2 | Peroxiredoxin-2 | 17 | 1.303 | 1.280 |

| 67 | Q61838 | PZP | Pregnancy zone protein | 70 | 1.052 | |

| 68 | P07758 | SERPINA1A | Alpha-1-antitrypsin 1-1 | 18 | 0.963 | |

| 69 | P22599 | SERPINA1B | Alpha-1-antitrypsin 1-2 | 6 | 0.824 | |

| 70 | Q00897 | SERPINA1D | Alpha-1-antitrypsin 1-4 | 8 | 0.835 | 0.832 |

| 71 | P07759 | SERPINA3K | Serine protease inhibitor A3K | 14 | 1.076 | |

| 72 | Q91WP6 | SERPINA3N | Serine protease inhibitor A3N | 17 | 1.503 | |

| 73 | P32261 | SERPINC1 | Antithrombin-III | 26 | 0.926 | |

| 74 | P49182 | SERPIND1 | Heparin cofactor 2 | 9 | 0.994 | |

| 75 | P97298 | SERPINF1 | Pigment epithelium-derived factor | 18 | 0.946 | |

| 76 | Q61247 | SERPINF2 | Alpha-2-antiplasmin | 6 | 0.841 | |

| 77 | P97290 | SERPING1 | Plasma protease C1 inhibitor | 12 | 1.149 | |

| 78 | P70441 | SLC9A3R1 | Na(+)/H(+) exchange regulatory cofactor | 29 | 1.156 | |

| 79 | P35441 | THBS1 | Thrombospondin-1 | 63 | 1.233 | |

| 80 | Q9Z1T2 | THBS4 | Thrombospondin-4 | 23 | 1.220 | |

| 81 | P07309 | TTR | Transthyretin | 10 | 1.242 | |

| 82 | P29788 | VTN | Vitronectin | 10 | 1.168 | 1.042 |

The UniProt protein identifiers (ID), protein IPA code, full name, and fold changes (FC) of significantly differentially expressed proteins (q-value < 0.05) following local heart irradiation at 8 or 16 Gy are shown. Cells without any value mean that the protein did not pass the selection criteria in the proteomics analysis (q-value < 0.05, protein identification with at least two unique peptides). The shared proteins are in bold.

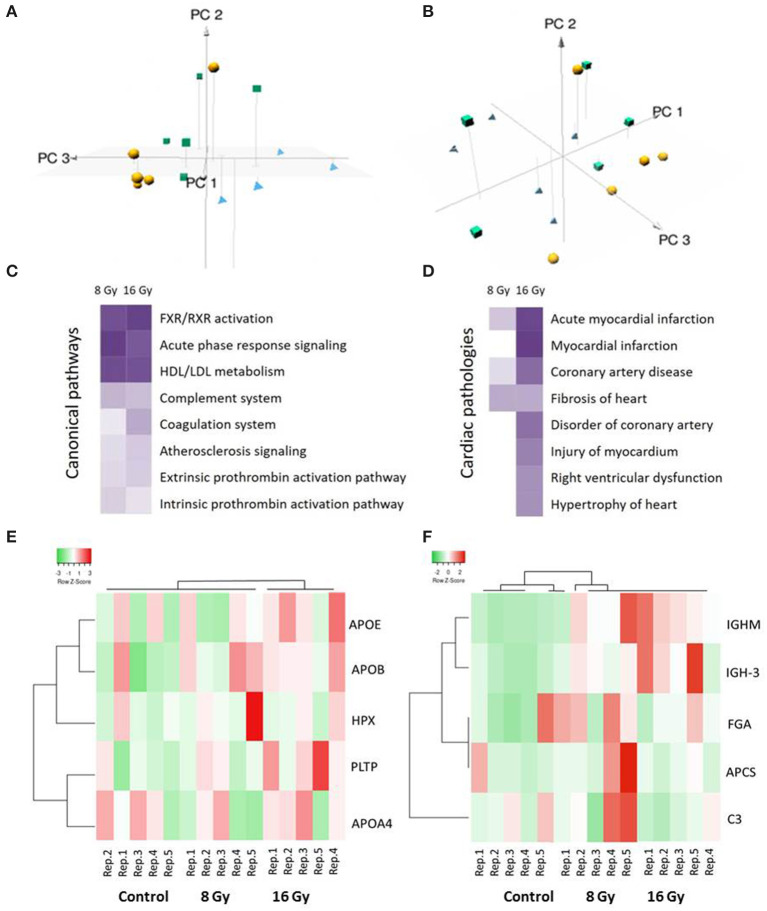

To assess the global variation in the samples, a multivariate analysis was performed using three-dimensional principal component analysis (3D-PCA). The 3D-PCA, based on the normalized intensities of all serum proteins, showed a clustering among the different groups (PC1: 15.9%, PC2: 15.1%, and PC3: 12.3%) (Figures 1A,B). The 8- and 16-Gy treated samples were separated mainly on the PC2 axis, whereas the discrimination between the controls and 8-Gy treated samples was visible on the PC3 axis.

Figure 1.

Multivariate, pathway, and cardiotoxicity analyses of the significantly differentially expressed serum proteins after local heart irradiation using 0 (control), 8, or 16 Gy. The principal component analysis (PCA) performed on normalized intensities of all proteins resulted in PC1, PC2, and PC3 as follows: PC1 15.9%, PC2 15.1%, and PC3 12.3%. The control samples are represented as yellow balls, the samples exposed to 8 Gy in green cubes, and the 16 Gy treated samples in blue pyramids (A,B). A dose-dependent alteration is observed in the pathways involved in the inflammation and lipid metabolism (C). Several proteins were identified associated with different heart pathologies (D). The pathway and cardiotoxicity scores are displayed using a purple color gradient; the darker the color, the higher the scores and, thereby, statistical significance. The score is the negative log of the p-value derived from the Fisher's Exact test. By default, the rows (pathways) with the highest total scores across the set of observations are sorted to the top. The analysis was performed using Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) (Qiagen Inc., https://www.qiagenbioinformatics.com/products/ingenuity-pathway-analysis). The heat maps show hierarchical clustering (complete linkage, Spearman ranked correlation) of significantly deregulated proteins belonging to the high-density lipoprotein (HDL)/low-density lipoprotein (LDL) metabolism (E) and acute phase response (F) pathways in the control and irradiated samples. The green bars indicate downregulation and the red bars upregulation. The analysis was performed by the Heatmapper web server (http://www.heatmapper.ca/) (31). Detailed information of the proteomics features and individual samples is given in Supplementary Table 1.

In particular, apolipoproteins, serpins, immunoglobulins, and inter-alpha-trypsin inhibitors were differentially regulated in the irradiated mice at both doses (Table 1). These shared proteins are mainly involved in the inflammatory response, and cholesterol and lipid metabolism. A detailed analysis of functional interactions and biological pathways based on differentially regulated proteins showed that acute phase response signaling, LXR/RXR cascade, cholesterol metabolism, coagulation system, and atherosclerosis signaling were the most affected pathways (Figure 1C and Supplementary Table 2). The differentially regulated proteins are associated with several heart pathologies such as infarction, hypertrophy, and fibrosis (Figure 1D and Supplementary Table 3). The analysis indicated a dose-dependent increase in the significance of the influenced pathways and in the cardiac pathologies.

Based on the list of canonical pathways (Figure 1C) the deregulated proteins belonging to two of the significantly affected pathways, namely, HDL/LDL metabolism and acute phase response signaling, were subjected to hierarchical clustering analysis (Figures 1E,F) (31). The heat map showed a clustering associated with the irradiation status of the groups.

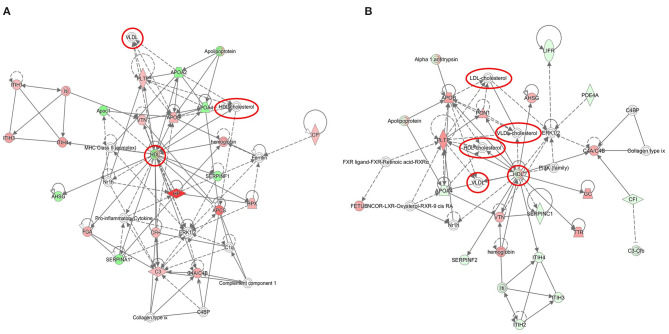

The significantly deregulated proteins built a functional network associated with cholesterol metabolism and transport (Figure 2 and Supplementary Table 4). All deregulated proteins formed a tight cluster interacting with regulatory proteins of the inflammatory and acute phase response pathways.

Figure 2.

Graphical representation of cholesterol-associated networks based on radiation-induced alterations in the serum proteome. The protein clusters are shown at 8 Gy (A) and 16 Gy (B). The upregulated proteins are marked in red and the downregulated in green. The nodes represent proteins connected with arrows; the solid arrows represent direct interactions and the dotted arrows indirect interactions. The cholesterol nodes are marked inside red circles and boxes. The IPA codes and corresponding full protein names are shown in Table 1 and in Supplementary Table 1. The analysis was performed using the Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) (https://www.qiagenbioinformatics.com/products/ingenuity-pathway-analysis).

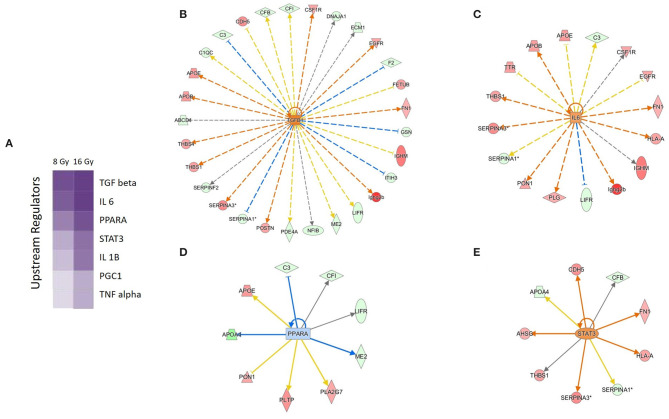

The prediction analysis of the upstream regulators of the significantly deregulated proteins identified transcription factors involved in proinflammatory response (IL-6, TGF-β, and STAT3) and lipid metabolism (PPARα, PGC-1). The proinflammatory regulators were predicted to be activated, while PPARα was predicted to be inactivated (Figure 3 and Supplementary Table 5).

Figure 3.

Predicted upstream regulators of the deregulated serum proteins. Predicted upstream regulators are displayed using a purple color gradient where the intensity of the purple color corresponds to statistical significance (the deeper the color, the higher the significance). The score is the negative log of the p-value derived from Fisher's exact test. By default, the rows (upstream regulators) with the highest total scores across the set of observations are sorted to the top (A). The predicted upstream regulators and their activity status at 16 Gy are shown: TGF-β (B), IL-6 (C), PPARα (D), and STAT3 (E). The orange and the blue color of the nodes indicate activation and deactivation, respectively; the solid arrows represent direct interactions and the dotted arrows indirect interactions. The deregulated proteins forming the wheel around the nodes are marked in red (upregulation) and green (downregulation). The IPA codes and corresponding full protein names are shown in Table 1 and in Supplementary Table 1. The analysis was performed using Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) (https://www.qiagenbioinformatics.com/products/ingenuity-pathway-analysis).

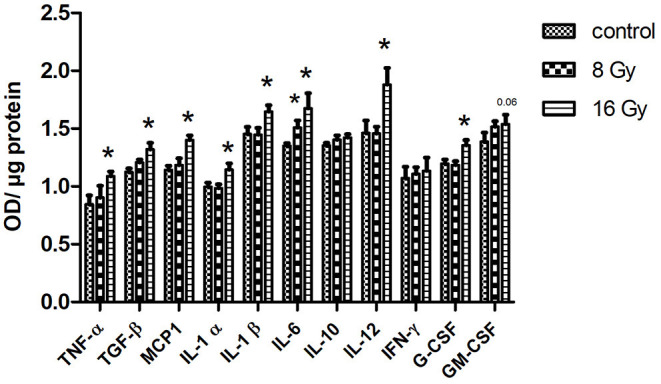

Radiation-Induced Serum Inflammatory Markers

Since the inflammatory response was the main affected pathway in the serum proteome following local heart irradiation, the level of 11 different cytokines and inflammatory mediators was measured in serum using ELISA. At 8 Gy, only the level of IL-6 significantly increased. In contrast, following 16 Gy, the serum levels of TNF-α, TGF-β, MCP-1, IL-1 α and β, IL-6, IL-12, and G-CSF were significantly increased in comparison with controls (Figure 4). The level of IFN-γ, IL-10, and GM-CSF remained unchanged after irradiation.

Figure 4.

The ELISA analysis of serum cytokines. The level of cytokines was measured in 100 μg of serum in mice following 8 or 16 Gy local heart radiation using ELISA (t-test; *p < 0.05, mean with SEM, n = 5).

Radiation-Associated Changes in Serum Lipids

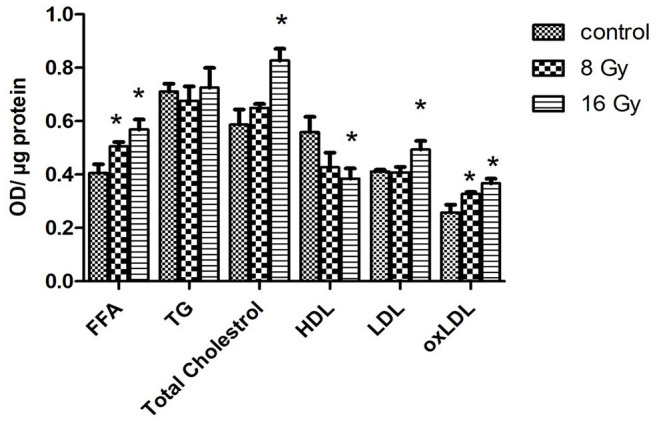

The changes in the serum proteome indicated alterations in lipid metabolism. Therefore, the level of free fatty acid (FFA), total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein (HDL), low-density lipoprotein (LDL), and triglyceride (TG) was measured in the serum of the control and irradiated mice. The level of FFA was increased at both radiation doses, while the levels of total cholesterol and LDL were increased only at 16 Gy. Similarly, the level of HDL was reduced only at 16 Gy (Figure 5). The level of TG remained unchanged in irradiated mice.

Figure 5.

The ELISA analysis of serum lipid levels. The levels of free fatty acid (FFA), triglyceride (TG), total cholesterol, HDL, LDL, and oxidized low-density lipoprotein (oxLDL) were measured in 100 μg of serum of mice at 8- or 16-Gy local heart irradiation using ELISA (t-test; *p < 0.05, mean with SEM, n = 5).

To examine the effect of oxidative stress on the level of serum lipids, the level of oxidized LDL (oxLDL) was analyzed. The analysis confirmed an enhanced level of oxLDL at both radiation doses (Figure 5).

Discussion

The serum proteome is a reliable mirror of the individual's healthy and diseased states (33). In this study, we used global serum proteomics analysis as a starting point to predict radiation effects outside the target tissue. Applying a multivariate analysis on the data, in this case principal component analysis and hierarchical clustering, we could separate the control group from the irradiated groups. Although the analysis could even differentiate between the two irradiated groups based on the radiation dose, it also highlighted a panel of proteins being differentially expressed in both irradiated groups. This panel, rather than one single protein, can be considered as a radiation biomarker in the serum proteome.

This analysis also clearly showed that local heart irradiation is able to induce systemic inflammation and hypercholesterolemia in mice. These two responses are similar to those found in a multiomics study comparing atherogenic and dyslipidemic mice with wild-type mice and, more importantly, when comparing familial hypercholesterolemia patients with healthy controls (34).

The degree of this systemic inflammatory and dyslipidemic effect was dose-dependent and thereby presumably also related to the degree of the heart damage. The dose of 8 Gy was only partly able to induce similar proteome changes as the 16-Gy dose, and the proteome was, in general, altered to a lesser extent. Furthermore, the lower radiation dose was not able to alter the cytokine or lipid profile of the serum as strongly as the higher dose.

The pathological changes in the locally irradiated heart tissue of these mice have been described in our previous study (35) where we showed radiation-induced elevation of inactive phosphorylated PPARα and increased expression levels of proteins involved in SMAD-dependent and SMAD-independent TGF-β signaling. Furthermore, we showed enhanced levels of proteins involved in fibroblast to myofibroblast conversion and inflammation at 16 Gy. Some, but not all, of these protein expression changes were also present at 8 Gy (35). Histological examination in similarly treated C57BL/6J mice revealed a significant increase in epicardial thickness (8 and 16 Gy), enhanced levels of inflammatory cells, and iron-containing macrophages (16 Gy) after 20 weeks (36). These changes are in line with the alterations found in the serum of irradiated mice in this study.

We have shown previously that, particularly, cardiac endothelial cells respond to high-dose radiation by secreting proinflammatory cytokines in vivo and in vitro (19, 37–39). TNF-α that we found significantly elevated at the 16-Gy dose modulates the inflammatory response by activating the expression of IL-1 and IL-6 (40). These cytokines that also were upregulated in the serum of irradiated animals serve as significant predictors of cardiovascular disease (40, 41). In agreement with our data, elevated levels of IL-1 and IL-6 were found in patients after radiation therapy for lung cancer (42).

We found in this study changed levels in serum proteins involved in blood clotting in irradiated mice, indicating not only inflammatory but also thrombotic changes. Among these were several serpins, plasminogen, fibronectin, and fibrinogen. Fibrinogen is a serum adhesion molecule identified in individuals with a high risk for cardiovascular disorders (43). IL-1 and IL-6 positively influence the synthesis of fibrinogen (44, 45). Fibrinogens contribute to atherosclerotic plaque formation by inducing endothelial permeability and increase the probability for thrombus formation by enhancing the blood viscosity and platelet aggregation (44, 46, 47). In agreement with our results, previous studies show an induction of thrombotic responses in locally irradiated carotid and saphenous arteries and in the heart (48–50).

The proteomics data in this study predicted radiation-induced activation of TGF-β, and its upregulation in the serum was confirmed at 16 Gy using ELISA. TGF-β is a multifunctional cytokine regulating inflammation and fibrosis in the heart (51, 52). The consequences of cardiac fibrosis are severe including contractile dysfunction, deformation and remodeling of the cardiac structure, and heart failure (53). Enhanced levels of TGF-β mediate also radiation-induced cardiac fibrosis that is characterized by excess fibroblast proliferation and deposition of collagen fibers (36, 54). We have shown previously the activation of TGF-β signaling and induction of fibrosis in the mouse heart exposed to local high-dose radiation (16 Gy) (35, 55).

In contrast to the systemic inflammatory effect, this is, to the best of our knowledge, the first study to show that local heart irradiation has a profound effect on serum lipids. Enhanced levels of free fatty acids and total cholesterol that we find here, especially in the 16-Gy irradiated mice, are strong risk factors for cardiovascular disease (56, 57). Similarly, increased LDL and decreased HDL levels, particularly in combination, are associated with increased risk for cardiovascular disease in humans since, if long lasting, they are known to lead to hardening of the arteries and atherosclerosis (58). The enhancement of oxLDL serum level that we have observed already in a previous study (19) is a strong predictive marker for upcoming coronary heart disease events in healthy men and a potential risk factor for cardiovascular disease (59, 60). OxLDL is involved in the early progression of the atherosclerotic plaque formation including endothelial injury, increased levels of adhesion molecules, leukocyte recruitment and extravasation, and foam cell and thrombus formation (61). Moreover, it activates the inflammatory response and increases the production of cytokines (62).

The transcription factor PPARα that was predicted to be inactivated in irradiated animals, based on the serum proteome profiling, is the main regulator of lipid metabolism (63). Furthermore, it exerts anti-inflammatory effects in the vascular wall and, thereby, protects against initiation and progression of atherosclerosis (64). The PPARα protein is highly expressed in the heart but not excreted in the serum. We have shown previously that cardiac PPARα is inactivated after local heart irradiation in mice (28). More importantly, it was inactivated in a dose-dependent manner in the cardiac left ventricle of Mayak nuclear workers exposed to varying total body doses of external gamma radiation when compared with Mayak workers not exposed to irradiation (10). Both exposed and control workers were diagnosed and died of ischemic heart disease. These data indicate that, although deactivation of PPARα is a common feature in ischemic heart disease and has been observed in human heart failure patients (65–69), it is especially prominent in radiation-induced heart disease and, therefore, a radiation target in the heart. It is particularly interesting that this is reflected in the serum proteome and cytokine and lipid profiles.

Immunoglobulins G and M were significantly upregulated in the serum of irradiated mice. Increased levels of both immunoglobulins in blood have been associated with adverse cardiovascular events, particularly in dyslipidemic men, but the epidemiological data are contradictory (70–73). In contrast, we did not identify cardiac troponins that are immediate markers of cardiac damage in humans as in mice. In mice, cardiac TnI concentrations in serum peaked at 1 to 4 h and declined to baseline by 48–72 h after a single administration of isoproterenol (74). This rapid decline is probably the reason why we did not find it elevated in the mouse serum 20 weeks after local heart radiation. Nevertheless, cardiac troponins seem to stay downregulated in the cardiac tissue a long time after radiation exposure. We have shown previously a dose-dependent decrease in cTnT in the human left ventricle in the Mayak worker study (10) and cTnI in the locally irradiated mouse heart (8 and 16 Gy) (28) suggesting an early leakage of cardiac troponins to the serum after radiation-induced myofibril degradation.

All in all, the data presented here suggest that the serum proteins and lipids function as potential biomarkers of cardiac injury following heart high-dose radiation exposure. They confirm our previous findings in the heart proteome following high-dose irradiation suggesting radiation-associated activation of TGF-β but inactivation of PPARα (35, 56). Especially, PPARα has become an interesting therapeutic target due to its pleiotropic activity in controlling lipid metabolism and energy homeostasis, inhibiting inflammation, reducing oxidative stress and apoptosis, and ameliorating contractile function. However, the clinical trials using PPARα agonists have shown contradictory outcomes so far (75). We suggest that administering such agonists could be particularly beneficial in connection with radiation therapy for thoracic malignancies where the heart may receive considerable radiation doses leading to adverse cardiovascular events (76). Furthermore, the data from this serum study could be beneficial in identifying patients who may develop radiation-associated cardiac toxicity.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/Supplementary Material.

Ethics Statement

All animal experiments were approved and licensed under Bavarian federal law (Certificate No. AZ 55.2-1-54-2532-114-2014).

Author Contributions

The study was designed by OA, VS, MA, GM, and ST. The irradiation was done by WS and VS. Serum collection was done by VS. The proteomics analysis was done by CT and OA. The ELISA experiments were performed by OA. The multivariate analysis was done by OA. OA and ST wrote the draft manuscript. All authors contributed to the revision of the manuscript, read it, discussed, and approved the final version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank Fabian Gruhn for the technical assistance, Lucas Duchrow for the help with the multivariate analysis, and Mona Aghaee for the critical feedback.

Footnotes

Funding. This research was funded by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research of Germany (BMBF) with grant number 02NUK064B (ST). VS was a recipient of a scholarship from the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD), grant number 91524248.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2021.678856/full#supplementary-material

References

- 1.Darby SC, Ewertz M, McGale P, Bennet AM, Blom-Goldman U, Bronnum D, et al. Risk of ischemic heart disease in women after radiotherapy for breast cancer. N Engl J Med. (2013) 368:987–98. 10.1056/NEJMoa1209825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Swerdlow AJ, Higgins CD, Smith P, Cunningham D, Hancock BW, Horwich A, et al. Myocardial infarction mortality risk after treatment for Hodgkin disease: a collaborative British cohort study. J Natl Cancer Inst. (2007) 99:206–14. 10.1093/jnci/djk029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Okwuosa TM, Anzevino S, Rao R. Cardiovascular disease in cancer survivors. Postgrad Med J. (2017) 93:82–90. 10.1136/postgradmedj-2016-134417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yusuf SW, Venkatesulu BP, Mahadevan LS, Krishnan S. Radiation-induced cardiovascular disease: a clinical perspective. Front Cardiovasc Med. (2017) 4:66. 10.3389/fcvm.2017.00066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Demirci S, Nam J, Hubbs JL, Nguyen T, Marks LB. Radiation-induced cardiac toxicity after therapy for breast cancer: interaction between treatment era and follow-up duration. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. (2009) 73:980–7. 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.11.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Adams MJ, Hardenbergh PH, Constine LS, Lipshultz SE. Radiation-associated cardiovascular disease. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. (2003) 45:55–75. 10.1016/S1040-8428(01)00227-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tapio S. Pathology and biology of radiation-induced cardiac disease. J Radiat Res. (2016) 57:439–48. 10.1093/jrr/rrw064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cuomo JR, Sharma GK, Conger PD, Weintraub NL. Novel concepts in radiation-induced cardiovascular disease. World J Cardiol. (2016) 8:504–19. 10.4330/wjc.v8.i9.504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boerma M, Sridharan V, Mao XW, Nelson GA, Cheema AK, Koturbash I, et al. Effects of ionizing radiation on the heart. Mutat Res. (2016) 770:319–27. 10.1016/j.mrrev.2016.07.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Azimzadeh O, Azizova T, Merl-Pham J, Subramanian V, Bakshi MV, Moseeva M, et al. A dose-dependent perturbation in cardiac energy metabolism is linked to radiation-induced ischemic heart disease in Mayak nuclear workers. Oncotarget. (2017) 8:9067–78. 10.18632/oncotarget.10424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Azimzadeh O, Azizova T, Merl-Pham J, Blutke A, Moseeva M, Zubkova O, et al. Chronic occupational exposure to ionizing radiation induces alterations in the structure and metabolism of the heart: a proteomic analysis of human formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) cardiac tissue. Int J Mol Sci. (2020) 21:6832. 10.3390/ijms21186832 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sridharan V, Aykin-Burns N, Tripathi P, Krager KJ, Sharma SK, Moros EG, et al. Radiation-induced alterations in mitochondria of the rat heart. Radiat Res. (2014) 181:324–34. 10.1667/RR13452.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Henri C, Heinonen T, Tardif JC. The role of biomarkers in decreasing risk of cardiac toxicity after cancer therapy. Biomark Cancer. (2016) 8:39–45. 10.4137/BIC.S31798 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tian S, Hirshfield KM, Jabbour SK, Toppmeyer D, Haffty BG, Khan AJ, et al. Serum biomarkers for the detection of cardiac toxicity after chemotherapy and radiation therapy in breast cancer patients. Front Oncol. (2014) 4:277. 10.3389/fonc.2014.00277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sharma S, Jackson PG, Makan J. Cardiac troponins. J Clin Pathol. (2004) 57:1025–6. 10.1136/jcp.2003.015420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Skyttä T, Tuohinen S, Boman E, Virtanen V, Raatikainen P, Kellokumpu-Lehtinen PL. Troponin T-release associates with cardiac radiation doses during adjuvant left-sided breast cancer radiotherapy. Radiat Oncol. (2015) 10:141. 10.1186/s13014-015-0436-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wu AHB. Release of cardiac troponin from healthy and damaged myocardium. Front Lab Med. (2017) 1:144–50. 10.1016/j.flm.2017.09.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Canada JM, Thomas GK, Trankle CR, Carbone S, Billingsley H, Van Tassell BW, et al. Increased C-reactive protein is associated with the severity of thoracic radiotherapy-induced cardiomyopathy. Cardiooncology. (2020) 6:2. 10.1186/s40959-020-0058-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Azimzadeh O, Sievert W, Sarioglu H, Merl-Pham J, Yentrapalli R, Bakshi MV, et al. Integrative proteomics and targeted transcriptomics analyses in cardiac endothelial cells unravel mechanisms of long-term radiation-induced vascular dysfunction. J Proteome Res. (2015) 14:1203–19. 10.1021/pr501141b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gkantaifi A, Papadopoulos C, Spyropoulou D, Toumpourleka M, Iliadis G, Kardamakis D, et al. Breast radiotherapy and early adverse cardiac effects. the role of serum biomarkers and strain echocardiography. Anticancer Res. (2019) 39:1667–73. 10.21873/anticanres.13272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ananthan K, Lyon AR. The role of biomarkers in cardio-oncology. J Cardiovasc Transl Res. (2020) 13:431–50. 10.1007/s12265-020-10042-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cesari M, Penninx BW, Newman AB, Kritchevsky SB, Nicklas BJ, Sutton-Tyrrell K, et al. Inflammatory markers and onset of cardiovascular events: results from the Health ABC study. Circulation. (2003) 108:2317–22. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000097109.90783.FC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ueland T, Gullestad L, Nymo SH, Yndestad A, Aukrust P, Askevold ET. Inflammatory cytokines as biomarkers in heart failure. Clin Chim Acta. (2015) 443:71–7. 10.1016/j.cca.2014.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Unger K, Li Y, Yeh C, Barac A, Srichai MB, Ballew EA, et al. Plasma metabolite biomarkers predictive of radiation induced cardiotoxicity. Radiother Oncol. (2020) 152:133–45. 10.1016/j.radonc.2020.04.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pietrowska M, Wlosowicz A, Gawin M, Widlak P. MS-based proteomic analysis of serum and plasma: problem of high abundant components and lights and shadows of albumin removal. Adv Exp Med Biol. (2019) 1073:57–76. 10.1007/978-3-030-12298-0_3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lin L, Zheng J, Yu Q, Chen W, Xing J, Chen C, et al. High throughput and accurate serum proteome profiling by integrated sample preparation technology and single-run data independent mass spectrometry analysis. J Proteomics. (2018) 174:9–16. 10.1016/j.jprot.2017.12.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smith JG, Gerszten RE. Emerging affinity-based proteomic technologies for large-scale plasma profiling in cardiovascular disease. Circulation. (2017) 135:1651–64. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.025446 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Azimzadeh O, Sievert W, Sarioglu H, Yentrapalli R, Barjaktarovic Z, Sriharshan A, et al. PPAR Alpha: a novel radiation target in locally exposed mus musculus heart revealed by quantitative proteomics. J Proteome Res. (2013) 12:2700–14. 10.1021/pr400071g [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sievert W, Stangl S, Steiger K, Multhoff G. Improved overall survival of mice by reducing lung side effects after high-precision heart irradiation using a small animal radiation research platform. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. (2018) 101:671–9. 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2018.02.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kramer A, Green J, Pollard J, Jr, Tugendreich S. Causal analysis approaches in Ingenuity Pathway Analysis. Bioinformatics. (2014) 30:523–30. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Babicki S, Arndt D, Marcu A, Liang Y, Grant JR, Maciejewski A, et al. Heatmapper: web-enabled heat mapping for all. Nucleic Acids Res. (2016) 44:W147–53. 10.1093/nar/gkw419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Perez-Riverol Y, Csordas A, Bai J, Bernal-Llinares M, Hewapathirana S, Kundu DJ, et al. The PRIDE database and related tools and resources in 2019: improving support for quantification data. Nucleic Acids Res. (2019) 47:D442–50. 10.1093/nar/gky1106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Geyer PE, Kulak NA, Pichler G, Holdt LM, Teupser D, Mann M. Plasma proteome profiling to assess human health and disease. Cell Syst. (2016) 2:185–95. 10.1016/j.cels.2016.02.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Olkowicz M, Czyzynska-Cichon I, Szupryczynska N, Kostogrys RB, Kochan Z, Debski J, et al. Multi-omic signatures of atherogenic dyslipidaemia: pre-clinical target identification and validation in humans. J Transl Med. (2021) 19:6. 10.1186/s12967-020-02663-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Subramanian V, Borchard S, Azimzadeh O, Sievert W, Merl-Pham J, Mancuso M, et al. PPARalpha Is necessary for radiation-induced activation of noncanonical tgfbeta signaling in the heart. J Proteome Res. (2018) 17:1677–89. 10.1021/acs.jproteome.8b00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Seemann I, Gabriels K, Visser NL, Hoving S, te Poele JA, Pol JF, et al. Irradiation induced modest changes in murine cardiac function despite progressive structural damage to the myocardium and microvasculature. Radiother Oncol. (2012) 103:143–50. 10.1016/j.radonc.2011.10.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Philipp J, Azimzadeh O, Subramanian V, Merl-Pham J, Lowe D, Hladik D, et al. Radiation-induced endothelial inflammation is transferred via the secretome to recipient cells in a STAT-mediated process. J Proteome Res. (2017) 16:3903–16. 10.1021/acs.jproteome.7b00536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Philipp J, Sievert W, Azimzadeh O, von Toerne C, Metzger F, Posch A, et al. Data independent acquisition mass spectrometry of irradiated mouse lung endothelial cells reveals a STAT-associated inflammatory response. Int J Radiat Biol. (2020) 96:642–50. 10.1080/09553002.2020.1712492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sievert W, Trott KR, Azimzadeh O, Tapio S, Zitzelsberger H, Multhoff G. Late proliferating and inflammatory effects on murine microvascular heart and lung endothelial cells after irradiation. Radiother Oncol. (2015) 117:376–81. 10.1016/j.radonc.2015.07.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Azzawi M, Hasleton P. Tumour necrosis factor alpha and the cardiovascular system: its role in cardiac allograft rejection and heart disease. Cardiovasc Res. (1999) 43:850–9. 10.1016/S0008-6363(99)00138-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang H, Park Y, Wu J, Chen X, Lee S, Yang J, et al. Role of TNF-alpha in vascular dysfunction. Clin Sci. (2009) 116:219–30. 10.1042/CS20080196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lierova A, Jelicova M, Nemcova M, Proksova M, Pejchal J, Zarybnicka L, et al. Cytokines and radiation-induced pulmonary injuries. J Radiat Res. (2018) 59:709–53. 10.1093/jrr/rry067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.de Moerloose P, Boehlen F, Neerman-Arbez M. Fibrinogen and the risk of thrombosis. Semin Thromb Hemost. (2010) 36:7–17. 10.1055/s-0030-1248720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lominadze D, Dean WL, Tyagi SC, Roberts AM. Mechanisms of fibrinogen-induced microvascular dysfunction during cardiovascular disease. Acta Physiol. (2010) 198:1–13. 10.1111/j.1748-1716.2009.02037.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rokita H, Neta R, Sipe JD. Increased fibrinogen synthesis in mice during the acute phase response: co-operative interaction of interleukin 1, interleukin 6, and interleukin 1 receptor antagonist. Cytokine. (1993) 5:454–8. 10.1016/1043-4666(93)90035-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Appiah D, Schreiner PJ, MacLehose RF, Folsom AR. Association of plasma gamma' fibrinogen with incident cardiovascular disease: the atherosclerosis risk in communities (ARIC) study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. (2015) 35:2700–6. 10.1161/ATVBAHA.115.306284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stec JJ, Silbershatz H, Tofler GH, Matheney TH, Sutherland P, Lipinska I, et al. Association of fibrinogen with cardiovascular risk factors and cardiovascular disease in the Framingham Offspring Population. Circulation. (2000) 102:1634–8. 10.1161/01.CIR.102.14.1634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Patties I, Haagen J, Dörr W, Hildebrandt G, Glasow A. Late inflammatory and thrombotic changes in irradiated hearts of C57BL/6 wild-type and atherosclerosis-prone ApoE-deficient mice. Strahlenther Onkol. (2015) 191:172–9. 10.1007/s00066-014-0745-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Patties I, Habelt B, Rosin B, Dörr W, Hildebrandt G, Glasow A. Late effects of local irradiation on the expression of inflammatory markers in the Arteria saphena of C57BL/6 wild-type and ApoE-knockout mice. Radiat Environ Biophys. (2014) 53:117–24. 10.1007/s00411-013-0492-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hoving S, Heeneman S, Gijbels MJ, Te Poele JA, Visser N, Cleutjens J, et al. Irradiation induces different inflammatory and thrombotic responses in carotid arteries of wildtype C57BL/6J and atherosclerosis-prone ApoE(-/-) mice. Radiother Oncol. (2012) 105:365–70. 10.1016/j.radonc.2012.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Frangogiannis NG. The role of transforming growth factor (TGF)-beta in the infarcted myocardium. J Thorac Dis. (2017) 9:S52–63. 10.21037/jtd.2016.11.19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hassan MO, Duarte R, Dix-Peek T, Dickens C, Naidoo S, Vachiat A, et al. Transforming growth factor-beta protects against inflammation-related atherosclerosis in South African CKD patients. Int J Nephrol. (2018) 2018:8702372. 10.1155/2018/8702372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Parichatikanond W, Luangmonkong T, Mangmool S, Kurose H. Therapeutic targets for the treatment of cardiac fibrosis and cancer: focusing on TGF-β signaling. Front Cardiovasc Med. (2020) 7:34. 10.3389/fcvm.2020.00034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sun W, Ni X, Sun S, Cai L, Yu J, Wang J, et al. Adipose-derived stem cells alleviate radiation-induced muscular fibrosis by suppressing the expression of TGF-beta1. Stem Cells Int. (2016) 2016:5638204. 10.1155/2016/5638204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Subramanian V, Seemann I, Merl-Pham J, Hauck SM, Stewart FA, Atkinson MJ, et al. The role of TGF Beta and PPAR alpha signalling pathways in radiation response of locally exposed heart: integrated global transcriptomics and proteomics analysis. J Proteome Res. (2016) 16:307–18. 10.1021/acs.jproteome.6b00795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pilz S, März W. Free fatty acids as a cardiovascular risk factor. Clin Chem Lab Med. (2008) 46:429–34. 10.1515/CCLM.2008.118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Peters SA, Singhateh Y, Mackay D, Huxley RR, Woodward M. Total cholesterol as a risk factor for coronary heart disease and stroke in women compared with men: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Atherosclerosis. (2016) 248:123–31. 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2016.03.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bhatnagar D, Soran H, Durrington PN. Hypercholesterolaemia and its management. Bmj. (2008) 337:a993. 10.1136/bmj.a993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Stocker R, Keaney JF, Jr. Role of oxidative modifications in atherosclerosis. Physiol Rev. (2004) 84:1381–478. 10.1152/physrev.00047.2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Meisinger C, Baumert J, Khuseyinova N, Loewel H, Koenig W. Plasma oxidized low-density lipoprotein, a strong predictor for acute coronary heart disease events in apparently healthy, middle-aged men from the general population. Circulation. (2005) 112:651–7. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.529297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Steinberg D. Lewis A. Conner memorial lecture. Oxidative modification of LDL and atherogenesis. Circulation. (1997) 95:1062–71. 10.1161/01.CIR.95.4.1062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rhoads JP, Major AS. How oxidized low-density lipoprotein activates inflammatory responses. Crit Rev Immunol. (2018) 38:333–42. 10.1615/CritRevImmunol.2018026483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gervois P, Torra IP, Fruchart JC, Staels B. Regulation of lipid and lipoprotein metabolism by PPAR activators. Clin Chem Lab Med. (2000) 38:3–11. 10.1515/CCLM.2000.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zandbergen F, Plutzky J. PPARalpha in atherosclerosis and inflammation. Biochim Biophys Acta. (2007) 1771:972–82. 10.1016/j.bbalip.2007.04.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Barger PM, Kelly DP. PPAR signaling in the control of cardiac energy metabolism. Trends Cardiovasc Med. (2000) 10:238–45. 10.1016/S1050-1738(00)00077-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sack MN, Rader TA, Park S, Bastin J, McCune SA, Kelly DP. Fatty acid oxidation enzyme gene expression is downregulated in the failing heart. Circulation. (1996) 94:2837–42. 10.1161/01.CIR.94.11.2837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Remondino A, Rosenblatt-Velin N, Montessuit C, Tardy I, Papageorgiou I, Dorsaz PA, et al. Altered expression of proteins of metabolic regulation during remodeling of the left ventricle after myocardial infarction. J Mol Cell Cardiol. (2000) 32:2025–34. 10.1006/jmcc.2000.1234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rosenblatt-Velin N, Montessuit C, Papageorgiou I, Terrand J, Lerch R. Postinfarction heart failure in rats is associated with upregulation of GLUT-1 and downregulation of genes of fatty acid metabolism. Cardiovasc Res. (2001) 52:407–16. 10.1016/S0008-6363(01)00393-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Dewald O, Sharma S, Adrogue J, Salazar R, Duerr GD, Crapo JD, et al. Downregulation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-alpha gene expression in a mouse model of ischemic cardiomyopathy is dependent on reactive oxygen species and prevents lipotoxicity. Circulation. (2005) 112:407–15. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.536318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cristea A, Rus H, Niculescu F, Bedeleanu D, Vlaicu R. Characterization of circulating immune complexes in heart disease. Immunol Lett. (1986) 13:45–9. 10.1016/0165-2478(86)90124-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kovanen PT, Mänttäri M, Palosuo T, Manninen V, Aho K. Prediction of myocardial infarction in dyslipidemic men by elevated levels of immunoglobulin classes A, E, and G, but not M. Arch Intern Med. (1998) 158:1434–9. 10.1001/archinte.158.13.1434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ravandi A, Boekholdt SM, Mallat Z, Talmud PJ, Kastelein JJ, Wareham NJ, et al. Relationship of IgG and IgM autoantibodies and immune complexes to oxidized LDL with markers of oxidation and inflammation and cardiovascular events: results from the EPIC-Norfolk Study. J Lipid Res. (2011) 52:1829–36. 10.1194/jlr.M015776 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Khamis RY, Hughes AD, Caga-Anan M, Chang CL, Boyle JJ, Kojima C, et al. High serum immunoglobulin g and m levels predict freedom from adverse cardiovascular events in hypertension: a nested case-control substudy of the anglo-scandinavian cardiac outcomes trial. EBioMedicine. (2016) 9:372–80. 10.1016/j.ebiom.2016.06.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Engle SK, Jordan WH, Pritt ML, Chiang AY, Davis MA, Zimmermann JL, et al. Qualification of cardiac troponin I concentration in mouse serum using isoproterenol and implementation in pharmacology studies to accelerate drug development. Toxicol Pathol. (2009) 37:617–28. 10.1177/0192623309339502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Li S, Yang B, Du Y, Lin Y, Liu J, Huang S, et al. Targeting PPARα for the treatment and understanding of cardiovascular diseases. Cell Physiol Biochem. (2018) 51:2760–75. 10.1159/000495969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Tapio S, Little MP, Kaiser JC, Impens N, Hamada N, Georgakilas AG, et al. Ionizing radiation-induced circulatory and metabolic diseases. Environ Int. (2021) 146:106235. 10.1016/j.envint.2020.106235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The mass spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE (32) partner repository with the dataset identifier PXD024446.

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/Supplementary Material.