Abstract

Background

Appendectomy is the gold standard for treatment of acute appendicitis. However, recent studies favor primary antibiotic therapy. The aim of this observational study was to explore changes in the numbers of operations for acute appendicitis in the period 2010–2017, paying special attention to disease severity.

Methods

Data from diagnosis-related group statistics were used to analyze the trends, mortality, and complication rates in the surgical treatment of appendicitis in Germany between 2010 and 2017. All cases of appendectomy after a diagnosis of appendicitis were included.

Results

Altogether, 865 688 inpatient cases were analyzed. The number of appendectomies went down by 9,8%, from 113 614 in 2010 to 102 464 in 2017, while the incidence fell from 139/100 000 in 2010 to 123/100 000 in 2017 (standardized by age group). This decrease is due to the lower number of operations for uncomplicated appendicitis (79 906 in 2017 versus 93 135 in 2010). Hospital mortality decreased both in patients who underwent surgical treatment of complicated appendicitis (0.62% in 2010 versus 0.42% in 2017) and in those with a complicated clinical course (5.4% in 2010 versus 3.4% in 2017).

Conclusion

Decisions on the treatment of acute appendicitis in German hospitals follow the current trend towards non-surgical management in selected patients. At the same time, the care of acute appendicitis has improved with regard to overall hospital morbidity and hospital mortality.

Appendicitis is a common global disease with a lifetime risk of 7–8% (1). The pooled incidence of appendicitis in Western Europe is estimated at 151 per 100 000 person-years (2). Appendectomy has been established as the treatment of choice for acute appendicitis (3). In recent years, the surgical treatment of acute uncomplicated appendicitis – defined as the absence of perforation or abscess – has been challenged in several randomized controlled trials. Some have proclaimed a paradigm shift and proposed antibiotics alone as first-line treatment for acute appendicitis (4– 9). However, estimating the course of the disease remains problematic even with the use of diagnostic imaging (e.g., low-dose computed tomography) (9). In 14 to 40% of all cases, primary antibiotic treatment is followed by recurrence and rescue surgery. The guideline recommendations regarding conservative and surgical treatment options therefore show considerable heterogeneity (10– 14).

The aim of this study was to depict trends in case numbers for surgical treatment of acute appendicitis in Germany by examining all inpatient cases from 2010 to 2017, based on full national data sets. Specifically, outcomes of care were assessed by studying indicators of complicated clinical courses and in-hospital mortality.

Methods

This retrospective observational study was based on microdata analysis of diagnosis-related group statistics for the years 2010 to 2017 via the Research Data Center of the Federal Statistical Office by means of controlled data processing (15). Details of the statistical methods can be found in the eMethods. The inclusion and exclusion criteria for diagnosis codes (International Statistical Classification of Diseases, 10th revision [ICD-10]) and procedure codes (German classification for operations and procedures [OPS]) are given in eTable 1.

eTable 1. Definition of patient population and stratification variables.

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria | |

| Patient population | ||

| All inpatient cases with appendectomy as sole intervention for acute appendicitis | PD ICD-10 K35, K36, K37 and OPS 5-470, 5-455.3 | OPS 5-471, 5-479 |

| Severity | ||

| Uncomplicated appendicitis | PD ICD-10 K35.30, K35.8, K36, K37 | |

| Complicated appendicitis | PD ICD-10 K35.2, K35.31, K35.32 | |

| Surgical approach | ||

| Open | OPS 5-470.0, 5-455.31 | OPS 5-470.2, 5-455.37 |

| Laparoscopic | OPS 5-470.1, 5-455.35 | OPS 5-470.0, 5-470.2, 5-455.31, 5-455.37 |

| Conversion | OPS 5-470.2, 5-455.37 | |

| Other or undefined | OPS 5-470.x, 5-470.y | OPS 5-470.0, 5-470.1, 5-470.2, 5-455.31, 5-455.35, 5-455.37 |

| Type of surgery | ||

| Appendectomy | OPS 5-470 | OPS 5-455.3 |

| Cecal resection | OPS 5-455.3 | |

| Indicators of complicated course | ||

| Septicemia | SD ICD-10 A40, A41, R57.2, R65 | |

| Blood transfusions, ≥ 6 units | OPS 8-800.1, 8-800.c1-cr | |

| Postoperative ileus | SD ICD-10 K91.3 | |

| Mechanical ventilation > 24 h | Mechanical ventilation for > 24 h (separate data field) | |

| Complex intensive care | OPS 8-980, 8-98d, 8-98f (from 2013) | |

ICD, International Statistical Classification of Diseases; OPS, German classification for operations and procedures (Operationen- und Prozedurenschlüssel); PD, principal diagnosis; SD, secondary diagnosis

Complicated appendicitis was identified by the ICD-10 codes K35.2 (with generalized peritonitis), K35.31 (localized peritonitis with perforation or rupture), and K35.32 (with peritoneal abscess). The clinical outcome was assessed in terms of in-hospital mortality and indicators of a complicated clinical course. Based on previous research, these indicators were defined by means of the ICD-10 codes for the secondary diagnoses of septicemia or postoperative ileus and the OPS codes for blood transfusion (≥ six units), complex intensive care treatment, or mechanical ventilation for more than 24 hours (etable 1) (16, 17).

Results

Characteristics of cases treated

A total of 865 688 inpatient appendectomies for acute appendicitis were performed as independent procedures in Germany during the period 2010 to 2017 and were thus included in this study. The overall number of operations per year declined linearly from 113 614 cases in 2010 to 102 464 cases in 2017, a relative overall reduction of 9.8% (Table 1, eTable 2).

Table 1. Characteristics of inpatient cases with appendectomy as sole intervention for acute appendicitis.

| 2010 | 2017 | ||||

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Total number of inpatient cases | 113 614 | 100.0 | 102 464 | 100.0 | |

| Incidence per 100 000 persons | 139 | 124 | |||

| Incidence per 100 000 persons (standardized by age group, in relation to 2010) |

139 | 123 | |||

| Age (years) | < 15 | 22 273 | 19.6 | 14 944 | 14.6 |

| 15–35 | 53 165 | 46.8 | 47 331 | 46.2 | |

| > 35 | 38 176 | 33.6 | 40 189 | 39.2 | |

| Sex | Female | 59 734 | 52.6 | 51 173 | 49.9 |

| Length of hospital stay (days) | Mean (median) | 5.1 (4) | 4.4 (4) | ||

| Severity | Uncomplicated appendicitis | 93 135 | 82.0 | 79 906 | 78.0 |

| Complicated appendicitis | 20 479 | 18.0 | 22 558 | 22.0 | |

| Surgical procedure | Laparoscopic surgery | 86 500 | 76.1 | 95 441 | 93.1 |

| Open surgery | 23 365 | 20.6 | 4534 | 4.4 | |

| Conversion | 3728 | 3.3 | 2450 | 2.4 | |

| Other or undefined | 21 | 0.0 | 39 | 0.0 | |

| Type of surgery | Appendectomy | 112 815 | 99.3 | 101 037 | 98.6 |

| Cecal resection | 799 | 0.7 | 1427 | 1.4 | |

eTable 2. Characteristics of inpatient cases with appendectomy as sole intervention for appendicitis.

| 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | ||||||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Total number of inpatient cases | 113 614 | 100.0 | 113 975 | 100.0 | 111 957 | 100.0 | 108 437 | 100.0 | 107 322 | 100.0 | 104 922 | 100.0 | 102 997 | 100.0 | 102 464 | 100.0 | |

| Incidence per 100 000 persons | 139 | 142 | 139 | 134 | 132 | 128 | 125 | 124 | |||||||||

| Incidence per 100 000 persons (standardized by age group, in relation to 2010) |

139 | 142 | 139 | 134 | 132 | 127 | 124 | 123 | |||||||||

| Age (years) | < 15 | 22 273 | 19.6 | 21 451 | 18.8 | 19 991 | 17.9 | 18 256 | 16.8 | 16 893 | 15.7 | 15 891 | 15.1 | 15 139 | 14.7 | 14 944 | 14.6 |

| 15–35 | 53 165 | 46.8 | 53 537 | 47.0 | 53 171 | 47.5 | 52 412 | 48.3 | 51 967 | 48.4 | 50 151 | 47.8 | 48 692 | 47.3 | 47 331 | 46.2 | |

| > 35 | 38 176 | 33.6 | 38 987 | 34.2 | 38 795 | 34.7 | 37 769 | 34.8 | 38 462 | 35.8 | 38 880 | 37.1 | 39 166 | 38.0 | 40 189 | 39.2 | |

| Gender | Female | 59 734 | 52.6 | 60 236 | 52.9 | 58 890 | 52.6 | 57 071 | 52.6 | 56 563 | 52.7 | 53 715 | 51.2 | 51 944 | 50.4 | 51 173 | 49.9 |

| Length of hospital stay (days) | Mean (median) | 5.1 (4) | 4.9 (4) | 4.8 (4) | 4.7 (4) | 4.6 (4) | 4.6 (4) | 4.6 (4) | 4.4 (4) | ||||||||

| Severity | Uncomplicated appendicitis | 93 135 | 82.0 | 92 911 | 81.5 | 90 824 | 81.1 | 87 574 | 80.8 | 86 559 | 80.7 | 83 362 | 79.5 | 81 140 | 78.8 | 79 906 | 78.0 |

| Complicated appendicitis | 20 479 | 18.0 | 21 064 | 18.5 | 21 133 | 18.9 | 20 863 | 19.2 | 20 763 | 19.3 | 21 560 | 20.5 | 21 857 | 21.2 | 22 558 | 22.0 | |

| Surgical approach | Laparoscopic | 86 500 | 76.1 | 91 633 | 80.4 | 93 663 | 83.7 | 93 697 | 86.4 | 95 378 | 88.9 | 95 053 | 90.6 | 94 687 | 91.9 | 95 441 | 93.1 |

| Open | 23 365 | 20.6 | 18 582 | 16.3 | 14 777 | 13.2 | 11 578 | 10.7 | 9009 | 8.4 | 6992 | 6.7 | 5578 | 5.4 | 4534 | 4.4 | |

| Conversion | 3728 | 3.3 | 3688 | 3.2 | 3441 | 3.1 | 3118 | 2.9 | 2908 | 2.7 | 2848 | 2.7 | 2704 | 2.6 | 2450 | 2.4 | |

| Other or undefined | 21 | 0.0 | 72 | 0.1 | 76 | 0.1 | 44 | 0.0 | 27 | 0.0 | 29 | 0.0 | 28 | 0.0 | 39 | 0.0 | |

| Type of surgery | Appendectomy | 112 815 | 99.3 | 113 121 | 99.3 | 111 046 | 99.2 | 107 427 | 99.1 | 106 216 | 99.0 | 103 612 | 98.8 | 101 670 | 98.7 | 101 037 | 98.6 |

| Cecal resection | 799 | 0.7 | 854 | 0.7 | 911 | 0.8 | 1010 | 0.9 | 1106 | 1.0 | 1310 | 1.2 | 1327 | 1.3 | 1427 | 1.4 | |

Taking the population of Germany into consideration (18), the incidence of appendectomy in the year 2010 was 139 per 100 000 person-years. By 2017, the incidence had fallen to 124 per 100 000 person-years. Standardized by age groups to 2010, the incidence declined from 139 per 100 000 in 2010 to 123 per 100 000 in 2017 (etable 2). This corresponds to a relative reduction of approximately 11.5% within 8 years. The proportion represented by the youngest age group (< 15 years) decreased during the study from an initial 20% (n = 22 273) to 15% (n = 14 944), while the group “15–35” remained stable at 46% (n = 47 331) and the group “35 or older” increased from 34% (n = 38 176) to 39% (n = 40 189).

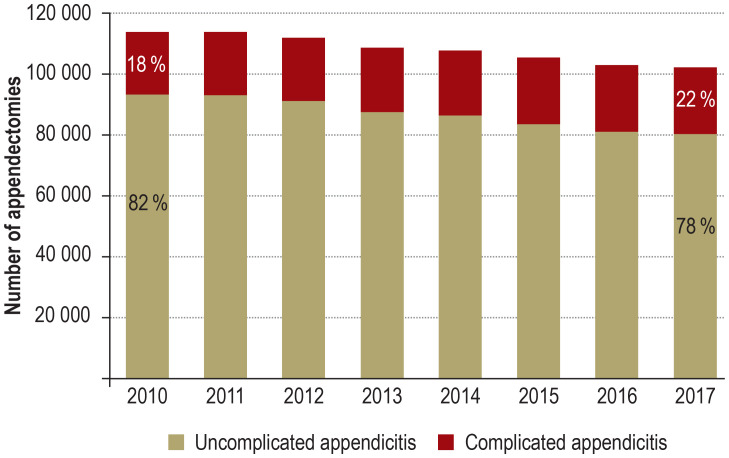

The proportion of female patients was higher in 2010 (53%; n = 59 734) than in 2017 (50%; n = 51 173). The mean length of hospital stay went down from 5.1 days to 4.4 days during the 8-year observation period. The proportion of operations performed for uncomplicated appendicitis decreased from 82% (n = 93 135) in 2010 to 78% (n = 79 906) in 2017. Conversely, the proportion of operations for complicated appendicitis increased from 18% (n = 20 479) to 22% (n = 22 558) (Figure 1). This trend can also be observed in the analysis of all individual federal states of Germany, with the sole exception of Saarland, where the opposite trend was found (etable 3).

Figure 1.

Number of appendectomies in the period 2010–2017

The overall number of appendectomies fell by 9.8% from 113 614 cases in 2010 to 102 464 cases in 2017. The proportion of all appendectomies accounted for by complicated appendicitis increased to 22%, while that for uncomplicated appendicitis decreased to 78%.

eTable 3. Inpatient cases of uncomplicated and complicated appendicitis per federal state (patient’s place of residence).

| 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | ||||||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Germany | Uncomplicated appendicitis | 93 135 | 82.0 | 92 911 | 81.5 | 90 824 | 81.1 | 87 574 | 80.8 | 86 559 | 80.7 | 83 362 | 79.5 | 81 140 | 78.8 | 79 906 | 78.0 |

| Complicated appendicitis | 20 479 | 18.0 | 21 064 | 18.5 | 21 133 | 18.9 | 20 863 | 19.2 | 20 763 | 19.3 | 21 560 | 20.5 | 21 857 | 21.2 | 22 558 | 22.0 | |

| Schleswig–Holstein | Uncomplicated appendicitis | 2702 | 80.4 | 2820 | 80.1 | 2736 | 79.1 | 2731 | 80.4 | 2736 | 79.5 | 2605 | 78.3 | 2490 | 76.9 | 2372 | 77.4 |

| Complicated appendicitis | 657 | 19.6 | 702 | 19.9 | 721 | 20.9 | 664 | 19.6 | 706 | 20.5 | 722 | 21.7 | 750 | 23.1 | 691 | 22.6 | |

| Hamburg | Uncomplicated appendicitis | 1831 | 83.6 | 1822 | 81.7 | 1831 | 82.4 | 1795 | 81.7 | 1837 | 82.5 | 1667 | 82.5 | 1658 | 79.7 | 1633 | 79.7 |

| Complicated appendicitis | 360 | 16.4 | 409 | 18.3 | 392 | 17.6 | 401 | 18.3 | 391 | 17.5 | 354 | 17.5 | 421 | 20.3 | 415 | 20.3 | |

| Lower Saxony | Uncomplicated appendicitis | 10 008 | 82.0 | 9756 | 81.8 | 9302 | 80.5 | 9022 | 79.8 | 9025 | 81.0 | 8522 | 79.1 | 8152 | 78.9 | 8150 | 78.8 |

| Complicated appendicitis | 2204 | 18.0 | 2169 | 18.2 | 2257 | 19.5 | 2282 | 20.2 | 2121 | 19.0 | 2251 | 20.9 | 2179 | 21.1 | 2199 | 21.2 | |

| Bremen | Uncomplicated appendicitis | 527 | 77.6 | 542 | 79.0 | 595 | 78.7 | 573 | 77.1 | 541 | 77.4 | 550 | 77.0 | 492 | 74.3 | 525 | 76.1 |

| Complicated appendicitis | 152 | 22.4 | 144 | 21.0 | 161 | 21.3 | 170 | 22.9 | 158 | 22.6 | 164 | 23.0 | 170 | 25.7 | 165 | 23.9 | |

| North Rhine–Westphalia | Uncomplicated appendicitis | 21 957 | 82.6 | 21 532 | 81.9 | 21 329 | 81.7 | 20 169 | 80.9 | 19 840 | 81.1 | 19 563 | 80.4 | 19 019 | 79.8 | 18 426 | 78.7 |

| Complicated appendicitis | 4610 | 17.4 | 4766 | 18.1 | 4771 | 18.3 | 4751 | 19.1 | 4632 | 18.9 | 4762 | 19.6 | 4806 | 20.2 | 4989 | 21.3 | |

| Hesse | Uncomplicated appendicitis | 6383 | 80.8 | 6449 | 81.1 | 6355 | 80.3 | 6097 | 79.7 | 6127 | 80.4 | 5969 | 78.2 | 5945 | 78.0 | 5952 | 78.3 |

| Complicated appendicitis | 1521 | 19.2 | 1507 | 18.9 | 1561 | 19.7 | 1552 | 20.3 | 1498 | 19.6 | 1667 | 21.8 | 1679 | 22.0 | 1653 | 21.7 | |

| Rhineland–Palatinate | Uncomplicated appendicitis | 4670 | 82.1 | 4530 | 81.1 | 4323 | 80.8 | 4281 | 81.4 | 3988 | 80.1 | 3917 | 78.3 | 3756 | 78.7 | 3812 | 77.7 |

| Complicated appendicitis | 1019 | 17.9 | 1057 | 18.9 | 1026 | 19.2 | 978 | 18.6 | 992 | 19.9 | 1087 | 21.7 | 1019 | 21.3 | 1094 | 22.3 | |

| Baden–Württemberg | Uncomplicated appendicitis | 11 035 | 80.7 | 11 154 | 80.3 | 10 890 | 79.5 | 10 780 | 79.5 | 10 528 | 77.9 | 10 154 | 78.2 | 9975 | 77.5 | 10 223 | 76.9 |

| Complicated appendicitis | 2639 | 19.3 | 2737 | 19.7 | 2804 | 20.5 | 2786 | 20.5 | 2989 | 22.1 | 2833 | 21.8 | 2895 | 22.5 | 3072 | 23.1 | |

| Bavaria | Uncomplicated appendicitis | 15 508 | 83.8 | 15 944 | 83.1 | 15 633 | 82.9 | 14 903 | 83.0 | 14 746 | 82.8 | 13 990 | 81.1 | 13 176 | 79.7 | 13 086 | 78.8 |

| Complicated appendicitis | 3001 | 16.2 | 3246 | 16.9 | 3234 | 17.1 | 3062 | 17.0 | 3057 | 17.2 | 3267 | 18.9 | 3362 | 20.3 | 3527 | 21.2 | |

| Saarland | Uncomplicated appendicitis | 834 | 78.0 | 939 | 78.8 | 978 | 80.9 | 928 | 78.1 | 860 | 78.0 | 840 | 78.7 | 887 | 80.0 | 847 | 78.3 |

| Complicated appendicitis | 235 | 22.0 | 252 | 21.2 | 231 | 19.1 | 260 | 21.9 | 242 | 22.0 | 227 | 21.3 | 222 | 20.0 | 235 | 21.7 | |

| Berlin | Uncomplicated appendicitis | 3458 | 79.4 | 3435 | 80.8 | 3341 | 80.6 | 3318 | 80.3 | 3415 | 80.2 | 3110 | 78.0 | 3128 | 76.7 | 3160 | 76.5 |

| Complicated appendicitis | 897 | 20.6 | 818 | 19.2 | 805 | 19.4 | 814 | 19.7 | 842 | 19.8 | 876 | 22.0 | 950 | 23.3 | 970 | 23.5 | |

| Brandenburg | Uncomplicated appendicitis | 2651 | 80.9 | 2582 | 80.1 | 2600 | 80.9 | 2424 | 80.6 | 2386 | 79.2 | 2233 | 77.3 | 2269 | 77.6 | 2246 | 76.3 |

| Complicated appendicitis | 627 | 19.1 | 641 | 19.9 | 613 | 19.1 | 583 | 19.4 | 625 | 20.8 | 656 | 22.7 | 656 | 22.4 | 698 | 23.7 | |

| Mecklenburg–Western Pomerania | Uncomplicated appendicitis | 1479 | 79.9 | 1483 | 78.7 | 1508 | 79.7 | 1429 | 79.2 | 1472 | 79.8 | 1418 | 78.5 | 1397 | 78.1 | 1258 | 74.7 |

| Complicated appendicitis | 372 | 20.1 | 401 | 21.3 | 384 | 20.3 | 376 | 20.8 | 372 | 20.2 | 389 | 21.5 | 391 | 21.9 | 427 | 25.3 | |

| Saxony | Uncomplicated appendicitis | 4074 | 82.1 | 3960 | 81.6 | 3926 | 80.8 | 3755 | 79.8 | 3681 | 80.1 | 3617 | 78.2 | 3467 | 78.0 | 3338 | 76.3 |

| Complicated appendicitis | 891 | 17.9 | 892 | 18.4 | 930 | 19.2 | 950 | 20.2 | 917 | 19.9 | 1008 | 21.8 | 977 | 22.0 | 1037 | 23.7 | |

| Saxony–Anhalt | Uncomplicated appendicitis | 2376 | 81.0 | 2374 | 79.8 | 2333 | 80.5 | 2268 | 80.5 | 2350 | 81.5 | 2315 | 79.4 | 2311 | 78.8 | 2131 | 77.5 |

| Complicated appendicitis | 559 | 19.0 | 601 | 20.2 | 564 | 19.5 | 549 | 19.5 | 532 | 18.5 | 602 | 20.6 | 623 | 21.2 | 617 | 22.5 | |

| Thuringia | Uncomplicated appendicitis | 2672 | 84.8 | 2688 | 84.9 | 2581 | 84.0 | 2551 | 83.0 | 2448 | 82.8 | 2313 | 81.9 | 2326 | 82.4 | 2155 | 79.6 |

| Complicated appendicitis | 479 | 15.2 | 479 | 15.1 | 493 | 16.0 | 523 | 17.0 | 509 | 17.2 | 510 | 18.1 | 498 | 17.6 | 552 | 20.4 | |

| Other country or unknown | Uncomplicated appendicitis | 970 | 79.1 | 901 | 78.8 | 563 | 75.2 | 550 | 77.2 | 579 | 76.3 | 579 | 75.8 | 692 | 72.8 | 592 | 73.2 |

| Complicated appendicitis | 256 | 20.9 | 243 | 21.2 | 186 | 24.8 | 162 | 22.8 | 180 | 23.7 | 185 | 24.2 | 259 | 27.2 | 217 | 26.8 | |

Morbidity and mortality

The mean rates for secondary diagnoses or procedures such as septicemia (0.56%), blood transfusion (0.07%), postoperative ileus (0.46%), mechanical ventilation > 24 hours (0.33%) and complex intensive care treatment (1.58%) did not change significantly. The proportion of cases with at least one of the above-mentioned surrogates for a complicated course stayed constant at 2.2–2.4% (2010: n = 2540; 2017: n = 2502). The overall in-hospital mortality rate was 0.12% (n = 118) in 2017 compared with 0.16% (n = 184) in 2010. If at least one of the indicators for a complicated course was present, the mean in-hospital mortality rate increased steeply to 4.2%. Here too, however, in-hospital mortality declined, from 5.4% (n = 136) in 2010 to 3.4% (n = 86) in 2017 (Table 2, eTable 4).

Table 2. Morbidity and mortality of inpatient cases with appendectomy as sole intervention for appendicitis.

| 2010 | 2017 | ||||

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Total number of patients | 113 614 | 100.0 | 102 464 | 100.0 | |

| Indicators of complicated course | Septicemia | 578 | 0.5 | 727 | 0.7 |

| Blood transfusions (≥ 6 units) |

108 | 0.1 | 50 | 0.05 | |

| Postoperative ileus | 494 | 0.4 | 537 | 0.5 | |

| Mechanical ventilation > 24 h | 434 | 0.4 | 309 | 0.3 | |

| Complex intensive care | 1796 | 1.6 | 1609 | 1.6 | |

| At least one indicator of complicated course | 2540 | 2.2 | 2502 | 2.4 | |

| In-hospital mortality (all appendectomy cases) | 184 | 0.16 | 118 | 0.12 | |

| In-hospital mortality (among patients with at least one indicator of complicated course) | 136 | 5.4 | 86 | 3.4 | |

eTable 4. Morbidity and mortality of inpatient cases with appendectomy as sole intervention for appendicitis.

| 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | ||||||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Total number of patients | 113 614 | 100.0 | 113 975 | 100.0 | 111 957 | 100.0 | 108 437 | 100.0 | 107 322 | 100.0 | 104 922 | 100.0 | 102 997 | 100.0 | 102 464 | 100.0 | |

| Indicators of complicated course | Septicemia | 578 | 0.5 | 533 | 0.5 | 545 | 0.5 | 535 | 0.5 | 578 | 0.5 | 650 | 0.6 | 677 | 0.7 | 727 | 0.7 |

| Blood transfusions (≥ 6 units) |

108 | 0.1 | 104 | 0.1 | 90 | 0.1 | 77 | 0.1 | 75 | 0.1 | 52 | 0.05 | 59 | 0.1 | 50 | 0.05 | |

| Postoperative ileus | 494 | 0.4 | 468 | 0.4 | 473 | 0.4 | 454 | 0.4 | 509 | 0.5 | 526 | 0.5 | 521 | 0.5 | 537 | 0.5 | |

| Mechanical ventilation > 24 h | 434 | 0.4 | 399 | 0.4 | 384 | 0.3 | 346 | 0.3 | 320 | 0.3 | 363 | 0.3 | 329 | 0.3 | 309 | 0.3 | |

| Complex intensive care | 1796 | 1.6 | 1806 | 1.6 | 1693 | 1.5 | 1678 | 1.5 | 1744 | 1.6 | 1690 | 1.6 | 1697 | 1.6 | 1609 | 1.6 | |

| At least one indicator of complicated course | 2540 | 2.2 | 2496 | 2.2 | 2432 | 2.2 | 2346 | 2.2 | 2512 | 2.3 | 2501 | 2.4 | 2521 | 2.4 | 2502 | 2.4 | |

| In-hospital mortality (all appendectomy cases) | 184 | 0.16 | 174 | 0.15 | 138 | 0.12 | 139 | 0.13 | 134 | 0.12 | 112 | 0.11 | 114 | 0.11 | 118 | 0.12 | |

| In-hospital mortality (among patients with at least one indicator of complicated course) | 136 | 5.4 | 131 | 5.3 | 105 | 4.3 | 106 | 4.5 | 107 | 4.3 | 86 | 3.4 | 81 | 3.2 | 86 | 3.4 | |

Uncomplicated versus complicated appendicitis

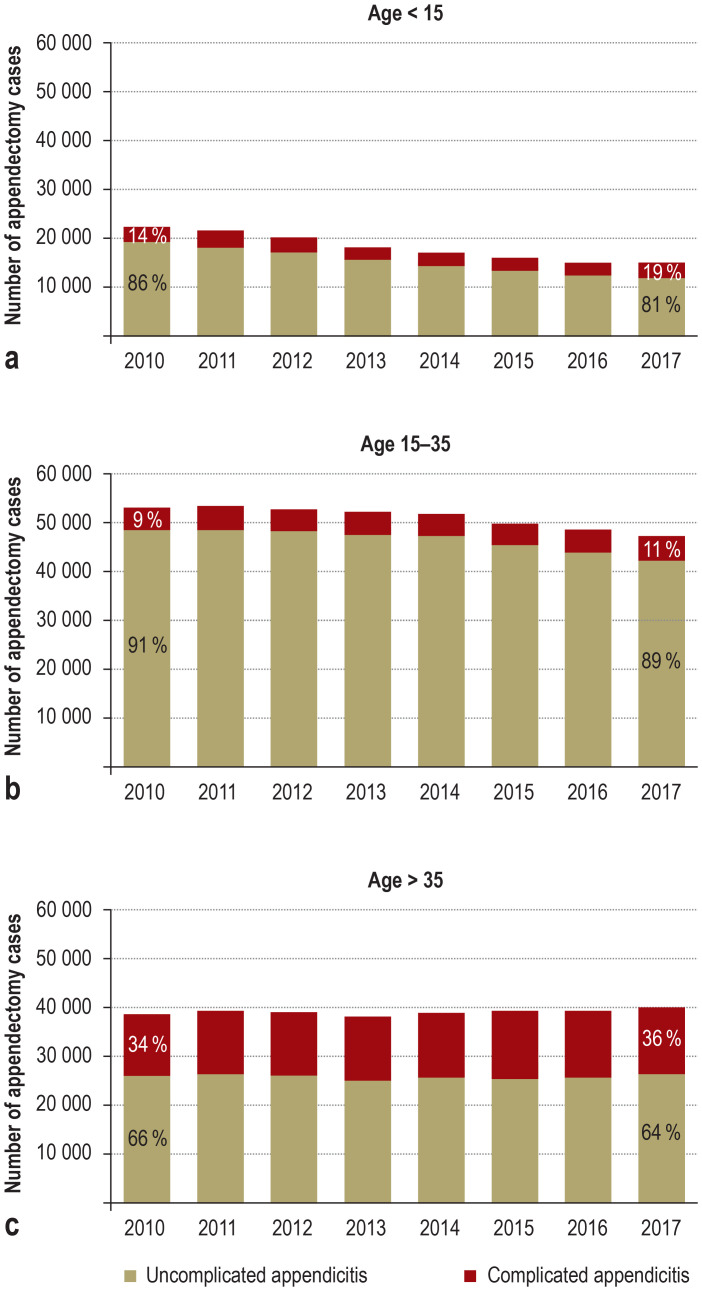

The ratio of appendectomies for uncomplicated versus complicated appendicitis differed among the age groups (efigure). In patients aged < 15 years, the number of appendectomies for uncomplicated appendicitis declined, while the absolute numbers of appendectomies for complicated appendicitis stayed almost constant. As a consequence, the proportion of appendectomies for complicated appendicitis rose from 14% (n = 3083) in 2010 to 19% (n = 2879) in 2017. In the intermediate age group (15–35 years) the proportion of appendectomies for complicated appendicitis increased from 9% (n = 4604) in 2010 to 11% (n = 5104) in 2017, and for patients older than 35 years the proportion was 34% (n = 12 792) in 2010 and 36% (n = 14 575) in 2017.

eFigure.

The development of absolute case numbers for appendectomy, stratified by age group.

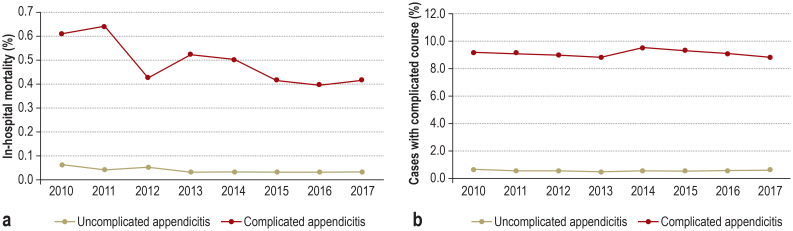

Of note, in-hospital mortality differed between uncomplicated appendicitis and complicated appendicitis (etable 5). The in-hospital mortality rate for uncomplicated appendicitis was 0.06% (57 deaths) in 2010 and fell by 50% to 0.03% in 2017 (23 deaths) (Figure 2a). The in-hospital mortality rate for an acute complicated appendicitis was more than 10 times higher: 0.62% (127 deaths) in 2010, 0.42% (95 deaths) in 2017. At least one of the indicators of a complicated clinical course was present in 9.3% (n = 1897) of all patients with complicated appendicitis in 2010 and in 8.9% (n = 2001) in 2017—compared with 0.7% and 0.6%, respectively, for uncomplicated appendicitis (Figure 2b).

eTable 5. Appendectomy case numbers, mortality, and morbidity, stratified by severity of appendicitis (uncomplicated or complicated).

| 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | |||||||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |||

| Total number of patients | 113 614 | 100.0 | 113 975 | 100.0 | 111 957 | 100.0 | 108 437 | 100.0 | 107 322 | 100.0 | 104 922 | 100.0 | 102 997 | 100.0 | 102 464 | 100.0 | ||

| Hospital size | ≤ 20 000 cases per year |

Uncomplicated appendicitis | 62 791 | 83.0 | 60 583 | 82.6 | 56 367 | 82.5 | 52 161 | 81.9 | 49 421 | 81.7 | 45 547 | 80.6 | 42 771 | 80.1 | 41 943 | 79.6 |

| Complicated appendicitis | 12 839 | 17.0 | 12 735 | 17.4 | 11 988 | 17.5 | 11 551 | 18.1 | 11 095 | 18.3 | 10 988 | 19.4 | 10 655 | 19.9 | 10 744 | 20.4 | ||

| > 20 000 cases per year |

Uncomplicated appendicitis | 30 344 | 79.9 | 32 328 | 79.5 | 34 457 | 79.0 | 35 413 | 79.2 | 37 138 | 79.3 | 37 815 | 78.2 | 38 369 | 77.4 | 37 963 | 76.3 | |

| Complicated appendicitis | 7640 | 20.1 | 8329 | 20.5 | 9145 | 21.0 | 9312 | 20.8 | 9668 | 20.7 | 10 572 | 21.8 | 11 202 | 22.6 | 11 814 | 23.7 | ||

| Age (years) | < 15 | Uncomplicated appendicitis | 19 190 | 86.2 | 18 379 | 85.7 | 17 067 | 85.4 | 15 418 | 84.5 | 14 184 | 84.0 | 13 188 | 83.0 | 12 328 | 81.4 | 12 065 | 80.7 |

| Complicated appendicitis | 3083 | 13.8 | 3072 | 14.3 | 2924 | 14.6 | 2838 | 15.5 | 2709 | 16.0 | 2703 | 17.0 | 2811 | 18.6 | 2879 | 19.3 | ||

| 15–35 | Uncomplicated appendicitis | 48 561 | 91.3 | 48 791 | 91.1 | 48 325 | 90.9 | 47 634 | 90.9 | 47 283 | 91.0 | 45 205 | 90.1 | 43 809 | 90.0 | 42 227 | 89.2 | |

| Complicated appendicitis | 4604 | 8.7 | 4746 | 8.9 | 4846 | 9.1 | 4778 | 9.1 | 4684 | 9.0 | 4946 | 9.9 | 4883 | 10.0 | 5104 | 10.8 | ||

| > 35 | Uncomplicated appendicitis | 25 384 | 66.0 | 25 741 | 66.0 | 25 432 | 65.6 | 24 522 | 64.9 | 25 092 | 65.2 | 24 969 | 64.2 | 25 003 | 63.8 | 25 614 | 63.7 | |

| Complicated appendicitis | 12 792 | 34.0 | 13 246 | 34.0 | 13 363 | 34.4 | 13 247 | 35.1 | 13 370 | 34.8 | 13 911 | 35.8 | 14 163 | 36.2 | 14 575 | 36.3 | ||

| Mortality*1 | In-hospital mortality | Uncomplicated appendicitis | 57 | 0.06 | 38 | 0.04 | 47 | 0.05 | 28 | 0.03 | 29 | 0.03 | 21 | 0.03 | 27 | 0.03 | 23 | 0.03 |

| Complicated appendicitis | 127 | 0.62 | 136 | 0.65 | 91 | 0.43 | 111 | 0.53 | 105 | 0.51 | 91 | 0.42 | 87 | 0.40 | 95 | 0.42 | ||

| Complicated course*2 | At least one indicator of complicated course | Uncomplicated appendicitis | 643 | 0.7 | 569 | 0.6 | 515 | 0.6 | 492 | 0.6 | 524 | 0.6 | 478 | 0.6 | 510 | 0.6 | 501 | 0.6 |

| Complicated appendicitis | 1897 | 9.3 | 1927 | 9.2 | 1917 | 9.1 | 1854 | 8.9 | 1988 | 9.6 | 2023 | 9.4 | 2011 | 9.2 | 2001 | 8.9 | ||

*1 The percentages given indicate the proportion of the total quantity

*2 The percentages given indicate the proportion of the subset of uncomplicated (complicated) appendicitis per year

Figure 2.

Development of in-hospital mortality and proportion of cases with complicated course, stratified by severity of appendicitis (complicated versus uncomplicated)

Mortality is higher for appendectomy cases with complicated appendicitis than for appendectomy cases with uncomplicated appendicitis and shows a declining trend over time (a).

The proportion of cases with a complicated course is higher for appendectomy cases with complicated appendicitis than for appendectomy cases with uncomplicated appendicitis. No temporal trend is evident (b).

Discussion

This study demonstrates a decrease in the number of appendectomies for acute appendicitis between 2010 and 2017 in Germany (relative reduction: 9.8%; demographically adjusted relative reduction: 11.5%). Interestingly, despite the reduction in the absolute number of appendectomies, the proportion of patients with complicated appendicitis has increased. This effect was most pronounced in patients younger than 15 years (etable 5). The decrease in cases reflects either a declining incidence of acute appendicitis or a decrease in the number of patients treated surgically. The latter would be consistent with the current trend towards primary antibiotic treatment in selected patients (19, 20). De Wijkerslooth et al. reported a fall in the incidence of appendectomy from 90 per 100 000 inhabitants in 2006 to 78 per 100 000 in 2015 (21). It remains unclear why the incidence in their study was significantly lower than in our and other studies (see below). Moreover, the authors were unable to determine whether the cause was a reduction in the incidence of acute appendicitis or a decrease in the number of patients treated surgically. Furthermore, improved diagnostic modalities (sonography, computed tomography, etc.) are contributing to the reduced rate of appendectomy. However, the reduction cannot be fully explained by a lower rate of negative appendectomies (22– 24).

The data on the development of the incidence of appendicitis are very heterogeneous. Studies in the USA and England describe decreasing rates (25, 26), while more recent publications report stable or rising case numbers (27– 30). A systematic review on the global incidence of appendicitis published in 2017 estimated the pooled incidence of appendicitis or appendectomy in western Europe at 151/100 000 person-years; since 1990 the incidence of appendectomy has decreased in western countries, while the incidence of appendicitis is stated as stable (2). Assuming that the incidence remained stable during the period we investigated, one can conclude that the observed decrease of appendectomies in Germany may be influenced by the growing number of studies which, on the basis of their results, recommend conservative treatment of 60–70% of all appendicitis patients (3, 19, 20, 31, 32). A glance at the appendectomy numbers for uncomplicated and complicated appendicitis seems to confirm this conclusion: The proportion of patients that underwent appendectomy for uncomplicated appendicitis fell from 82% (n = 93 135) in 2010 to 78% (n = 79 906) in 2017.

Since both the absolute and relative number of operations for complicated appendicitis increased, it might be supposed that an increasing number of patients treated with antibiotics were developing complicated appendicitis and required surgery. Although this cannot be supported by unambiguous data in this study, the results of a recently published randomized controlled trial suggest exactly this clinical scenario (20). This study of 1552 adult patients showed non-inferiority of antibiotic treatment; nevertheless, three out of every ten participants in the antibiotic arm of the trial had to undergo rescue appendectomy. In addition, the complication rate was correspondingly higher. In our study, the increase in the number of cecal resections from 799 (0.7%) in 2010 to 1427 (1.4%) in 2017 may be due to a delay in surgical intervention, as cecal resection is only performed when severe inflammation does not allow simple appendectomy.

Appendectomy is in principle a low-risk surgical procedure. The in-hospital mortality rate in Germany decreased from 0.16% (n = 184) in 2010 to 0.12% (n = 118) in 2017, which is comparable to mortality rates reported from other countries (0.09% to 0.25%) (33). Here, we also present data on the mortality rate stratified by disease severity. For uncomplicated appendicitis, the rate of death was 0.03% (95% confidence interval [0.02; 0.04]; n = 23) in 2017, compared to a significantly higher rate of 0.06% in 2010 ([0.05; 0.08]; n = 57). For complicated appendicitis, the mortality rate was more than 10 times higher in 2017, at 0.42% (n = 95), but also showed a downward trend (2010: 0.62%; n = 127). For those cases in which acute appendicitis—whether uncomplicated or complicated—was accompanied by at least one surrogate parameter of a complicated clinical course (i.e., septicemia, transfusion of more than six units of erythrocytes or whole blood, postoperative ileus, mechanical ventilation > 24 h, need for intensive care), the in-hospital mortality in 2017 was 3.4% (n = 86), compared with 5.4% (n = 136) in 2010. As expected, however, complicated appendicitis was more likely than uncomplicated appendicitis to involve a complicated clinical course (2017: 8.9% vs. 0.6%; 2010: 9.3% vs. 0.7%).

The present study has several limitations. Studies based on DRG statistics are subject to potential information bias introduced by inconstant coding behavior. Moreover, the distinction between non-perforated and perforated appendicitis is based on ICD-10 diagnoses. These are assigned on the basis of the surgeon’s intraoperative findings, so the distinction is open to interobserver variation (34). Cases with the clinical appearance of appendicitis and conservative treatment were excluded from the study because the respective number might have been distorted by incorrect diagnoses and multiple hospitalizations. Moreover, owing to the way in which DRG data are documented no temporal association could be established between possible subsequent procedures and diagnoses, which limits our assumptions with regard to a complicated disease course.

Given these limitations, the advantage of this study lies in the robustness of its data. Whereas study populations often represent only a statistical sample, our study included all inpatient cases in Germany who underwent surgery for acute appendicitis, corresponding to over 850 000 cases.

We therefore present not only developments in the surgical treatment of appendicitis, but also new data on in-hospital mortality of appendicitis, stratified by disease severity and clinical course. The numbers of appendectomies for appendicitis in general, and uncomplicated appendicitis in particular, fell during the study period, while the population (all residents of Germany) grew (18).

The findings of this study suggest that German hospitals are acting, albeit slowly, on the evidence of recently published studies favoring a non-operative approach in selected patients. Thus, an overall reduction of 9.8% was observed within 8 years. Advances in diagnosis may have contributed to this effect. Interestingly, the proportion of patients with complicated appendicitis treated with appendectomy increased during the period 2010 to 2017, while the use of appendectomy in those with uncomplicated appendicitis decreased. The outcome of treatment in terms of in-hospital morbidity and mortality improved during the same time span.

Supplementary Material

eMethods

Study design and setting

The study presented here is a population-based retrospective study based on the diagnosis-related groups hospital discharge data of the national reimbursement system (G-DRG). The evaluation of secondary data via the German DRG system for this investigation does not require ethics committee approval (e1).

Data

Since 2004, reimbursement for inpatient services in Germany has been uniform across all hospitals calculated through a DRG reimbursement system (G-DRG). The information available for each of these inpatient cases includes age, sex, diagnoses (coded according to the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th revision, German modification, ICD-10-GM), procedures (coded according to the German classification for operations and procedures, OPS), length of hospital stay, and mode of discharge. The individual inpatient data of the DRG statistics for the years 2010 to 2017 were accessed remotely via the Research Data Center of the Federal Statistical Office by means of controlled remote data processing (15).

Inclusion criteria

The units of analysis were inpatient cases who underwent appendectomy as sole intervention for appendicitis. These cases were identified by a principal diagnosis of appendicitis in combination with the OPS code for appendectomy or cecal resection. The inclusion and exclusion criteria for the diagnosis and procedure codes are given in etable 1. Due to the nature of the data, no histological diagnoses were included in this analysis.

Stratification and outcome variables

Complicated appendicitis was identified by a principal diagnosis code of acute appendicitis with generalized (K35.2) or localized peritonitis with perforation or rupture (K35.31) or acute appendicitis with peritoneal abscess (K35.32). In accordance with previously published age distributions in patients with acute appendicitis, the study population was divided into three groups: < 15 years, 15–35 years, and > 35 years (e2). The clinical outcome was assessed in terms of in-hospital mortality and indicators of a complicated clinical course. Based on previous research, these indicators were defined by the ICD-10 codes for the secondary diagnoses septicemia and postoperative ileus, the procedure codes for blood transfusions (≥ 6 units), complex intensive care, or mechanical ventilation > 24 hours (etable 1) (16, 17). These indicators were designed to identify serious complications or procedures required for serious complications while being widely unaffected by variation in coding behavior (e3).

Statistical methods

This study follows the REporting of studies Conducted using Observational Routinely collected health Data (RECORD) statement checklist (e4). All calculations were performed using SAS Version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). Data were analyzed descriptively for every year of observation and are expressed as absolute and relative frequencies. Development of appendectomy case numbers over time was analyzed separately for uncomplicated and complicated appendicitis and stratified by age group and hospital size. Additionally, in-hospital mortality and indicators of clinical course were stratified according to uncomplicated or complicated appendicitis.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that no conflict of interest exists.

References

- 1.Stewart B, Khanduri P, McCord C, et al. Global disease burden of conditions requiring emergency surgery. Br J Surg. 2014;101:e9–e22. doi: 10.1002/bjs.9329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferris M, Quan S, Kaplan BS, et al. The global incidence of appendicitis: a systematic review of population-based studies. Ann Surg. 2017;266:237–241. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Téoule P, de Laffolie J, Rolle U, Reißfelder C. Acute appendicitis in childhood and adolescence—an everyday clinical challenge. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2020;117:764–774. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2020.0764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bhangu A, Soreide K, Di Saverio S, Assarsson JH, Drake FT. Acute appendicitis: modern understanding of pathogenesis, diagnosis, and management. Lancet. 2015;386:1278–1287. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00275-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Varadhan KK, Neal KR, Lobo DN. Safety and efficacy of antibiotics compared with appendicectomy for treatment of uncomplicated acute appendicitis: meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ. 2012;344 doi: 10.1136/bmj.e2156. e2156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Styrud J, Eriksson S, Nilsson I, et al. Appendectomy versus antibiotic treatment in acute appendicitis: a prospective multicenter randomized controlled trial. World J Surg. 2006;30:1033–1037. doi: 10.1007/s00268-005-0304-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eriksson S, Granstrom L. Randomized controlled trial of appendicectomy versus antibiotic therapy for acute appendicitis. Br J Surg. 1995;82:166–169. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800820207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hansson J, Korner U, Khorram-Manesh A, Solberg A, Lundholm K. Randomized clinical trial of antibiotic therapy versus appendicectomy as primary treatment of acute appendicitis in unselected patients. Br J Surg. 2009;96:473–481. doi: 10.1002/bjs.6482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vons C, Barry C, Maitre S, et al. Amoxicillin plus clavulanic acid versus appendicectomy for treatment of acute uncomplicated appendicitis: an open-label, non-inferiority, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2011;377:1573–1579. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60410-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Korndorffer JR Jr., Fellinger E, Reed W. SAGES guideline for laparoscopic appendectomy. Surg Endosc. 2010;24:757–761. doi: 10.1007/s00464-009-0632-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Di Saverio S, Birindelli A, Kelly MD, et al. WSES Jerusalem guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of acute appendicitis. World J Emerg Surg. 2016;11 doi: 10.1186/s13017-016-0090-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gorter RR, Eker HH, Gorter-Stam MA, et al. Diagnosis and management of acute appendicitis EAES consensus development conference 2015. Surg Endosc. 2016;30:4668–4690. doi: 10.1007/s00464-016-5245-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vettoretto N, Gobbi S, Corradi A, et al. Consensus conference on laparoscopic appendectomy: development of guidelines. Colorectal Dis. 2011;13:748–754. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2011.02557.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bakker OJ, Go PM, Puylaert JB, Kazemier G, Heij HA. Werkgroep richtlijn Diagnostiek en behandeling van acute a: [Guideline on diagnosis and treatment of acute appendicitis: imaging prior to appendectomy is recommended] Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 2010;154 A303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Research data centres of the Federal Statistical Office and the statistical offices of the Federal States. Diagnosis-Related Group Statistics (DRG Statistics) 2010-2017, own calculations. DOI: 10.21242/23141.2010.00.00.1.1.0 to DOI: 10.21242/23141.2017.00.00.1.1.0 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Krautz C, Nimptsch U, Weber GF, Mansky T, Grutzmann R. Effect of hospital volume on in-hospital morbidity and mortality following pancreatic surgery in Germany. Ann Surg. 2018;267:411–417. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nimptsch U, Mansky T. Deaths following cholecystectomy and herniotomy—an analysis of nationwide German hospital discharge data from 2009 to 2013. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2020;112:535–543. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2015.0535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Federal Statistical Office (Destatis) www-genesis.destatis.de/genesis/online (last accessed on 19 April 2020) [Google Scholar]

- 19.Salminen P, Paajanen H, Rautio T, et al. Antibiotic therapy vs appendectomy for treatment of uncomplicated acute appendicitis: the APPAC randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2015;313:2340–2348. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.6154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Flum DR, Davidson GH, et al. CODA Collaborative, A randomized trial comparing antibiotics with appendectomy for appendicitis. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:1907–1919. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2014320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.de Wijkerslooth EML, van den Boom AL, Wijnhoven BPL. Disease burden of appendectomy for appendicitis: a population-based cohort study. Surg Endosc. 2020;34:116–125. doi: 10.1007/s00464-019-06738-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lu Y, Friedlander S, Lee SL. Negative appendectomy: clinical and economic implications. Am Surg. 2016;82:1018–1022. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oyetunji TA, Ong‘uti SK, Bolorunduro OB, Cornwell EE 3rd, Nwomeh BC. Pediatric negative appendectomy rate: trend, predictors, and differentials. J Surg Res. 2012;173:16–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2011.04.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Seetahal SA, Bolorunduro OB, Sookdeo TC, et al. Negative appendectomy: a 10-year review of a nationally representative sample. Am J Surg. 2011;201:433–437. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2010.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Addiss DG, Shaffer N, Fowler BS, Tauxe RV. The epidemiology of appendicitis and appendectomy in the United States. Am J Epidemiol. 1990;132:910–925. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kang JY, Hoare J, Majeed A, Williamson RC, Maxwell JD. Decline in admission rates for acute appendicitis in England. Br J Surg. 2003;90:1586–1592. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Buckius MT, McGrath B, Monk J, Grim R, Bell T, Ahuja V. Changing epidemiology of acute appendicitis in the United States: study period 1993-2008. J Surg Res. 2012;175:185–190. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2011.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Korner H, Soreide JA, Pedersen EJ, Bru T, Sondenaa K, Vatten L. Stability in incidence of acute appendicitis. A population-based longitudinal study. Dig Surg. 2001;18:61–66. doi: 10.1159/000050099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Livingston EH, Fomby TB, Woodward WA, Haley RW. Epidemiological similarities between appendicitis and diverticulitis suggesting a common underlying pathogenesis. Arch Surg. 2011;146:308–314. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2011.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Anderson JE, Bickler SW, Chang DC, Talamini MA. Examining a common disease with unknown etiology: trends in epidemiology and surgical management of appendicitis in California, 1995-2009. World J Surg. 2012;36:2787–2794. doi: 10.1007/s00268-012-1749-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Salminen P, Tuominen R, Paajanen H, et al. Five-year follow-up of antibiotic therapy for uncomplicated acute appendicitis in the APPAC randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2018;320:1259–1265. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.13201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Flum DR. Clinical practice Acute appendicitis—appendectomy or the „antibiotics first“ strategy. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1937–1943. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp1215006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Faiz O, Clark J, Brown T, et al. Traditional and laparoscopic appendectomy in adults: outcomes in English NHS hospitals between 1996 and 2006. Ann Surg. 2008;248:800–806. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31818b770c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ponsky TA, Hafi M, Heiss K, Dinsmore J, Newman KD, Gilbert J. Interobserver variation in the assessment of appendiceal perforation. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2009;19(Suppl 1):S15–S18. doi: 10.1089/lap.2008.0095.supp. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E1.Swart E, Gothe H, Geyer S, et al. [Good Practice of Secondary Data Analysis (GPS): guidelines and recommendations] Gesundheitswesen. 2015;77:120–126. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1396815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E2.Primatesta P, Goldacre MJ. Appendicectomy for acute appendicitis and for other conditions: an epidemiological study. Int J Epidemiol. 1994;23:155–160. doi: 10.1093/ije/23.1.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E3.Nimptsch U, Spoden M, Mansky T. [Definition of variables in hospital discharge data: pitfalls and proposed solutions] Gesundheitswesen. 2020;82:S29–S40. doi: 10.1055/a-0977-3332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E4.Benchimol EI, Smeeth L, Guttmann A, et al. The REporting of studies conducted using observational routinely-collected health data (RECORD) statement. PLoS Med. 2015;12 doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001885. e1001885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods

Study design and setting

The study presented here is a population-based retrospective study based on the diagnosis-related groups hospital discharge data of the national reimbursement system (G-DRG). The evaluation of secondary data via the German DRG system for this investigation does not require ethics committee approval (e1).

Data

Since 2004, reimbursement for inpatient services in Germany has been uniform across all hospitals calculated through a DRG reimbursement system (G-DRG). The information available for each of these inpatient cases includes age, sex, diagnoses (coded according to the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th revision, German modification, ICD-10-GM), procedures (coded according to the German classification for operations and procedures, OPS), length of hospital stay, and mode of discharge. The individual inpatient data of the DRG statistics for the years 2010 to 2017 were accessed remotely via the Research Data Center of the Federal Statistical Office by means of controlled remote data processing (15).

Inclusion criteria

The units of analysis were inpatient cases who underwent appendectomy as sole intervention for appendicitis. These cases were identified by a principal diagnosis of appendicitis in combination with the OPS code for appendectomy or cecal resection. The inclusion and exclusion criteria for the diagnosis and procedure codes are given in etable 1. Due to the nature of the data, no histological diagnoses were included in this analysis.

Stratification and outcome variables

Complicated appendicitis was identified by a principal diagnosis code of acute appendicitis with generalized (K35.2) or localized peritonitis with perforation or rupture (K35.31) or acute appendicitis with peritoneal abscess (K35.32). In accordance with previously published age distributions in patients with acute appendicitis, the study population was divided into three groups: < 15 years, 15–35 years, and > 35 years (e2). The clinical outcome was assessed in terms of in-hospital mortality and indicators of a complicated clinical course. Based on previous research, these indicators were defined by the ICD-10 codes for the secondary diagnoses septicemia and postoperative ileus, the procedure codes for blood transfusions (≥ 6 units), complex intensive care, or mechanical ventilation > 24 hours (etable 1) (16, 17). These indicators were designed to identify serious complications or procedures required for serious complications while being widely unaffected by variation in coding behavior (e3).

Statistical methods

This study follows the REporting of studies Conducted using Observational Routinely collected health Data (RECORD) statement checklist (e4). All calculations were performed using SAS Version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). Data were analyzed descriptively for every year of observation and are expressed as absolute and relative frequencies. Development of appendectomy case numbers over time was analyzed separately for uncomplicated and complicated appendicitis and stratified by age group and hospital size. Additionally, in-hospital mortality and indicators of clinical course were stratified according to uncomplicated or complicated appendicitis.