Abstract

Objectives

This study aimed to determine the relationship between emotional reflexivity and work-life integration through the mechanism of moral courage and enhance our understanding of the importance of these nursing concepts to enable the nurses to develop better coping strategies for work-life integration.

Methods

A cross-sectional survey was performed with 249 nurses, including staff nurses, ICU and critical care nurses, operation theatre nurses, pediatric nurses from 17 hospitals. Emotional Reflexivity, work-life integration, and courage were measured using a demographic information questionnaire, Life Project Reflexivity Scale (LPRS), Nurse’s Moral Courage Scale (NMCS), and Work-Life Boundary Enactment (WLBE) scale. A series of multiple regressions analyzed the mediating effect.

Results

Emotional Reflexivity was positively correlated with work-life integration (β = 0.66, P < 0.01). There was a positive correlation between emotional reflexivity and moral courage. But the path did not get the necessary support in the structural equation modeling (SEM) (β = −0.13, P = 0.40). When controlling for courage (β = 0.42, P < 0.01), the association was significant between emotional reflexivity and work-life integration with partial mediation.

Conclusion

The study reported a positive correlation between reflexivity and work-life integration. Thus, nurses’ work-life integration becomes better by reinforcing their emotional reflexivity and moral courage.

Keywords: Emotional reflexivity, Life, Moral courage, Nurses, Survey and questionnaires, Work

What is known?

-

•

Previous studies have used emotional intelligence and emotional reflexivity interchangeably and have replaced emotional reflexivity with emotional intelligence.

-

•

Previous studies have used work-life balance and work-life integration interchangeably.

-

•

Studies exploring the role of moral courage in reflexivity-integration are not known yet.

What is new?

-

•

To understand how emotional reflexivity increases work-life integration, it is essential to consider the role of moral courage that is how courage helps nurses to identify personal and professional values and cope with work-life integration.

-

•

An increase in emotional reflexivity is positively related to work-life integration through moral courage.

1. Introduction

The nursing profession has always been plagued with long working hours and the untimely spurt of workload coupled with emotional and ethical complexity [1] and personal and professional values. Moral courage has always been the need of the hour for nurses. Integration of work and non-work domain creates stress and strain of juggling between domestic responsibilities and caring responsibilities along with challenging job demands [2]. Constant awareness about self helps nurses develop strategies and hone their skills to define their life goals and resolve conflict by making independent work-related decisions. We opine that emotional reflexivity (ER) is a kind of strategy that nurses employ more often to reflect on self-awareness and take steps to adjust work-life integration (WLI). Nurses use it to gain clarity on what they want in their personal lives and then implement various ways to balance working and living. Trusting in one’s belief and standing up to those beliefs without any fear becomes stronger with self-identification. Noble professions like teaching and healthcare are constantly faced with critical situations requiring moral courage for solving dilemmatic and ethical problems. For example, teaching the teachers and professors has always been expected to display values of being impartial, fair, and to enlighten the student mass. However, in certain conflicting situations, professors succumb to the organizational culture and peer pressure of not standing up to one’s personal and professional values and belief and thus resorting to breaking the code of conduct, favoritism, and cheating to save their job. This leads to endangering the value structure of the society, causing losses to the generations [3].

Similarly, in the health care profession, innumerable situations call for moral courage [1]. Conditions range from taking care of patients inflicted with highly infectious disease overcoming the fear of getting infected to breaking bad news of improper diagnosis or treatment. Recently, there have been instances of losing healthcare professionals and nurses while caring for patients infected with Ebola or COVID-19 [4]. These professionals were determined and were courageous to enforce ethical, societal, and professional norms without considering the cost they would pay in terms of getting infected or losing life [5].

According to Merriam Webster dictionary, courage is “mental strength to venture, persevere, and withstand fear or difficulty.” This is in line with Murray’s [6] opinion about courage. Murray defined a sense of courage stemming out of one’s determination to overcome fear, live up to their values and ideals and resolve conflicts without any obligations to compromise. On the other hand, ER in the dictionary has been defined as “the fact of someone being able to examine his or her feelings, reactions, and motives (= reasons for acting) and how these influences what, he or she does or thinks in a situation.” Analyzing the definitions, the authors find a common thread between the sense of courage and ER. The sense of courage implies firmness of one’s mind and belief gained through ER, which identifies and clarifies those beliefs and dispositions. Thus, the sense of courage is woven with fabrics of ER. To satiate their moral values for serving others in pain, nurses require a sense of courage to resolve the conflicts [7,8] while the studies focusing on courage have been scarce [9,10].

Moral courage is mental strength and is, therefore, implicit and judgmental. Implicit theory of courage starts with understanding an individual’s view on “what is courage?” [11]. The implicit approach is naturalistic, and it furthers people’s notion of courage or how they view courage as [12]. In a series of studies in the nursing domain, patients with chronic illness were asked to describe how courageous they were during their hospital stay [[13], [14], [15]] were asked to describe a situation in which they thought they were brave. The findings pointed out the development of being courageous to fight the illness. This is also in line with [16], who argued that moral courage is the “individual’s capacity to overcome fear and stand up for his or her core values.” There have had been many situations where nurses might have to remind doctors to sanitize their hands or put on the mask before visiting or touching a patient. Thus, according to Lachman [16], moral courage bridges the gap between personal values and acting on them to fulfill professional obligations. Thus, moral courage stems from personal values, integrity, professional commitments, and advocating them. However, literature on moral courage is heavily skewed and is rarely discussed in nursing literature.

In contrast, the concept is heavily discussed in the general workplace, relying on and drawing resources from psychology literature [17]. The importance of moral courage in nursing lies in the fact that it is responsible for maintaining a balanced approach in personal and professional lives. This is in line with one of the seminal works of Murray [18], where the author hinted towards the importance of moral courage in the personal and professional development of a nurse. Moral courage is an inevitable necessity for nurses [19]. Earlier studies have also demonstrated that moral courage is related to ER consisting of emotional self-awareness, self-regulation, and firm belief on ones’ self [20,21].

The nursing community requires research that provides a unique perspective on emotional self-management in general and ER, particularly in resolving ethical problems and conflicts. There is a scarcity of literature directly addressing ER as a specific term. Researchers have surrogated ER with emotional intelligence (EI) as most of the research has highlighted the importance of emotions on nursing actions [22,23]. Further, these research studies have embedded ER in EI instead of studying its impact independently on various aspects of nursing works. ER is understood as a process of identifying self-insight and awareness [24], articulating and clarifying one’s perspectives and values [25]. ER takes place through a series of processes facilitating the clarification on self-awareness and construction of self-identification [26]. With ER, nurses, amidst chaotic and unending job pressure, design and differentiate personal values and professional values, which helps them tackle conflicts occurring due to clashes or overlap in their personal and professional projects. ER is the process through which a nurse concludes who he/she is, and how is he/she going to balance his/her present and future personal and professional demands. This process of self-identification and act of balancing removes insecurities and uncertainties surrounding one’s personal and professional environment which leads to their well-being [27]. Extending this to a nursing domain, nurses can cope with work-life uncertainties or transitions [28]. Developing ER in nursing research, ER plays a prominent part in determining or altering nurses’ actions or choices based on assumptions, dispositions, biases, and subjectivities towards their approach and understanding of WLI in their day-to-day lives. Two primary principles of conservation of resources theory (COR) are resource loss and resource gain, and wherein resource loss is more impactful than resource gain [29]. With the process of identification and clarification of self-awareness, belief, values, worth, purpose, and dispositions, any individual and a nurse per se would retain and protect them. The nursing profession and ethical problems coexist. Hence, there will be situations when a nurse will be facing conflict and losing the valued resources.

ER embraces a sense of one’s self which forms the basis of dealing with work-life. Hence, it can be said that ER is the crux of WLI for nurses by helping them to understand about self and making connections between self at the personal life and professional life. WLI is an essential outcome of ER and is defined as an individual-level strategy of integrating work to the non-work method that affects general well-being wherein general wellbeing is understood by psychological health conceptualized in terms of exhaustion and work-life balance [30]. Nurses always find themselves identifying and clarifying their stand on situations involving conflict between personal, social, and organizational values. WLI as a concept focuses on blurred boundaries between work and life and relies on boundary/border theory [31,32]. WLI adopts integration strategies wherein the boundary/border is flexible, having easy access to both domains.

Although ER, WLI, and courage are considered pertinent elements of nursing, very little work has been done, resulting in very few studies. To contribute to the body of empirical research on ER and WLI through the lens of courage, we conducted the present study. Specifically, our study proposed a theoretical framework exploring the ER and WLI relation. Further, the study also aims to understand the role of courage which affects ER and WLI, the reason being, On the one hand, we assumed that courage leads to ER by clarifying a nurse’s awareness of her professional and moral values and further positively influences WLI by integrating work and non-work domains to fulfill the responsibilities, solely guided by her inner values of willingness to serve. Thus, we suggest that courage may positively relate to ER and other influence WLI.

Relying on boundary & border theory, COR, and implicit theory of courage, with work to life boundary and role transitions taking place, there is conflict and resource loss. ER will identify values, beliefs, and dispositions required for self-identification; moral courage will require standing up to those beliefs and values. ER and moral courage will determine the level of integration between work and nonwork domain. ER is all about strengthening one’s firmness on himself/herself and developing inner character. However, it is not an easy process. Building firmness on oneself and forming inner surface, moral values must be identified, clarified, practiced to the extent that it becomes a reflex to make positive changes in the work and nonwork domain [33]. This calls for moral courage to stand up to a belief, trust it, and make it a part of one’s character. It applies to nurses where nurses have to be courageous to trust themselves and use the same in the personal and professional domain. Thus, we suggest that high in ER is characterized by blurring boundaries between work and life, leading to higher WLI.

Further, higher ER leads to a more heightened sense of courage to advocate and stand up to beliefs. Similarly, nurses with a higher degree of integration between work and life have to be more courageous to resolve conflicting situations and ethical dilemmas. In other words, ER fabricates moral courage among nurses, which defines the degree of WLI. Thus, the following hypotheses were formulated for empirical validation:

H1

Increase in ER is positively related to WLI.

H2

Increase in ER is positively related to the sense of courage.

H3

Courage mediates the relationship between the increase in ER and WLI.

2. Method

2.1. Respondents and procedure

The cross-sectional research design was established among nurses employed in Indian public and private hospitals—seventeen reputed hospitals out of 26 extended authorization with their support personnel for survey distribution. Standard method variance (SMV) was avoided by employing three-wave procedures suggested by Ref. [34]. The questionnaire distributed in different stages was coded to match the sample respondents in subsequent survey exercises. In the first wave, 360 questionnaires containing demographic details and ER were administered. The response rate yielded was 83.2% (299 responses). Nearly after two weeks, in the second wave, the participants in the first stage shared their views on WLI instruments. Out of 299 responses, 268 responses were recorded (89.6%). In the third wave, after about a month, we circulated the courage questionnaire to the participants who had participated in both stages; 261 responses were collected for a response rate of 97.3%. The reduction of participants in the second and third waves was due to unforeseen absence of nurses (e.g., sick leave, deputed to other units of their hospitals). The questionnaire with missing information (12) was eliminated, and 249 respondents were considered for further analysis, representing a total response rate of 69.1%.

They are employed in critical care, cardiology, geriatrics, obstetric & gynecological, pediatrics, surgery, and transplantation. 12.05% (30/249) of sample respondents were male, and the mean age of the total sample was of 36.4 ± 6.3 years with an average work experience of 8.6 ± 4.2 years. The average tenure of working under their immediate supervisor was 4.78 ± 2.8 years. The details of the demographic characteristics are given in Table 1. ER, WLI, and courage were measured on them using a demographic information questionnaire, Life Project Reflexivity Scale (LPRS), Nurse’s Moral Courage Scale (NMCS), and Work-Life Boundary Enactment (WLBE) scale.

Table 1.

Characteristics of participants(n = 249).

| Characteristics | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Man | 30 | 12.05 |

| Woman | 219 | 87.95 |

| Marital status | ||

| Single | 43 | 17.27 |

| Married | 114 | 45.78 |

| Separated | 32 | 12.85 |

| Divorced | 60 | 24.10 |

| Work experience years | ||

| <3 | 18 | 7.22 |

| 3–5 | 51 | 20.48 |

| 6–9 | 118 | 47.39 |

| ≥10 | 62 | 24.90 |

| Tenure of work under immediate supervisor (years) | ||

| <1 | 16 | 6.43 |

| 1–3 | 27 | 10.84 |

| 4–7 | 119 | 47.79 |

| 8–10 | 43 | 17.27 |

| >10 | 44 | 17.67 |

2.2. Measurements

The self-administered questionnaire comprised demographic details (e.g., age, gender, marital status, total working experience, and tenure of work under their immediate supervisor/doctor) and three scales that measured courage, ER, and WLI.

2.2.1. Emotional reflexivity

ER was measured using the 15 items LPRS developed by Numminen et al. [35] for assessing one’s authentic self through reflexivity of one’s career and life goals. The scale with a response format on a 5-point Likert scale consists of 3 dimensions: authenticity (e.g., The professional projects for my future life are full of meaning for me), acquiescence (e.g., The projects for my future life are more anchored by the values of the society in which I live than my most authentic values) and clarity/project quality (e.g., It is clear to me what it fully entails for what I want to become in the next chapter of my professional life story). Better scores imply a stronger sense of emotional reflexivity. The CFA findings exhibited required validity of the instrument (χ2 = 439.41, df = 198, CFI = 0.94, GFI = 0 95, TLI = 0.95, RMSEA = 0.06). The Cronbach’s α coefficient for the overall scale was 0.85, and the three dimensions were 0.88, 0.91, 0.93, respectively.

2.2.2. Courage

Courage was measured through the 21 item NMCS developed by Hair et al. [36]. The scale comprises of 4 dimensions: compassion and true presence (e.g., Regardless of the care situation, I try to encounter each patient as a dignified human being even if …), moral responsibility (e.g., I bring up my honest opinion concerning even …), moral integrity (e.g., I adhere to professional, ethical principles even if …. ) and commitment to good care (e.g., If the resources required for ensuring good care are inadequate …). NMCS used a 5-point Likert scale: 1 = does not describe me at all through and 5 = describes me very well. Higher scores signify higher self-assured moral courage. We have conducted CFA to test whether the four-dimensional model and the overall second-order factor fit with the given data. The findings showed that NMCS is a valid instrument with the fit indices in the acceptable range (χ2 = 183.37, df = 74, CFI = 0.92, GFI = 0.92, TLI = 0.95, RMSEA = 0.05). The Cronbach’s α coefficient for the overall scale was 0.92, and the four dimensions were 0.91, 0.94, 0.89, 0.93, respectively.

2.2.3. Work-life integration

WLI was measured using a 16-item WLBE scale developed by Wepfer and colleagues [30]. Participants were instructed to indicate how they “currently manage the boundaries between work and non-work life.” The 5-point Likert scale consisting of 2 dimensions have polar statements: a) work-to-life direction (e.g., I always leave my workplace on time – I often leave my workplace late) and b) life-to-work direction (e.g., I never communicate with friends and family while I am at work – I often communicate with friends and family while I am at work). CFA validated the scale instrument (χ2 = 344.92, df = 139, CFI = 0.94, GFI = 0.92, TLI = 0.96, RMSEA = 0.06). The Cronbach’s α coefficient for the overall scale was 0.87, and the two dimensions were 0.89 and 0.91, respectively.

2.3. Ethical consideration

For gaining access, we contacted the HR/PR departments of hospitals with a formal request letter to carry out the field survey during Feb–April 2021. Participation in the survey exercise was voluntary, and the respondents have not been given any kind of compensation. The questionnaire during all three waves was handed over to sample respondents in opaque envelopes, with the first sheet being a consent form attached to it. Participants were assured in the consent form that the collected data would be reported as aggregate findings, and the responses will be kept private.

2.4. Data analysis

We performed principal component analysis (PCA) with promax rotation to assess whether the items were loading on individual factors. Minor alterations were performed to ensure that all the things of courage, ER, and WLI gets requisite loading (<0.40 with cross-loading >0.2 among the factors). 2 items were removed from WLI for having loading values less than 0.40 (“At work, I behave completely different than at home” and “I always leave my workplace on time – reverse coded).” In contrast, the rest of the scale items were maintained after conducting PCA. In addition, gender (man = 1, woman = 2), marital status (single = 1, married = 2, separated = 3, widowed = 4), work experience (less than 3 years = 1, 3–5 years = 2, 6–9 years = 3, 10 and more years = 4), tenure of work under immediate supervisor (less than 1 year = 1, 1–3 years = 2, 4–7 years = 3, 8–10 years = 4, more than 10 years = 4) were regarded as control variables in the multiple regression.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive statistics

The scores of questionnaire and correlation findings were shown in Table 2. For confirming the fitness of the overall model [37], the df, CFI, and RMSEA were analyzed using AMOS 20.0 [38]. Good model fit was achieved (χ2 = 117.59, df = 71, χ2/df = 1.65, CFI = 0.98, GFI = 0.97, RMSEA = 0.05) after performing minor error corrections advocated by large modification indices [39].

Table 2.

Descriptive, correlation of the study variables(n = 249).

| Variables | Mean ± SD |

r value |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Emotional reflexivity | Courage | ||

| Emotional reflexivity | 4.51 ± 0.51 | – | |

| Courage | 3.28 ± 0.39 | 0.42∗∗ | – |

| Work-life integration | 3.73 ± 0.44 | 0.27∗ | 0.38∗∗ |

Note:∗P < 0.05; ∗∗P < 0.01.

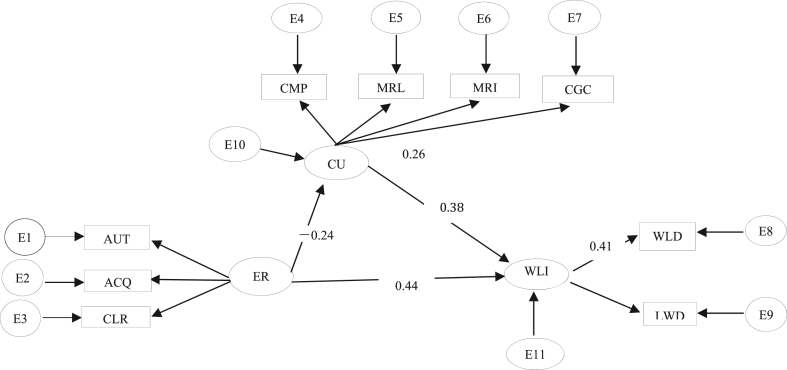

For examining the positive association between ER and WLI (H1) and the positive relations between ER and courage (H2) as in Table 1, The structural equation modeling (SEM) was performed using AMOS 20.0 [38]. The model got a good fit (χ2 = 126.41, df = 94, χ2/df = 1.34, CFI = 0.96, GFI = 0.95, RMSEA = 0.06) allowing the assumption that the increase in ER had a strong relation with WLI (β = 0.66, P < 0.01). Even though there was a positive correlation between ER and courage, the path did not get necessary support in SEM (β = −0.13, P = 0 0.40) and thus rejects the second hypothesis (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Final model with numbers inside arrows imply standardized regression weights. Numbers on top of item indicate R2 value. ER = emotional reflexivity. AUT = authenticity. ACQ = acquiescence. CLR = clarity. CU = courage. CMP = compassion and presence. MRL = moral responsibility. MRI = moral integrity. CGC = commitment to good care. WLI = work-life integration. WLD=work to life direction. LWD = life to work direction.

For validating the directivity and potential reciprocal relationship of the association between ER and WLI, a model having a double path between WLI and ER was designed, and the test was carried out using SEM. We have considered the suggestion of [40] in this regard. The model got a good fit (χ2 = 47.38, df = 24, χ2/df = 1.97, CFI = 0.98, GFI = 0.97, RMSEA = 0.04) and the magnitude of increase in ER heightens WLI (β = 0.66, P < 0.01), contrary to lack of WLI > increase in ER (β = −0.09, P = 0.32). The findings offer further support to H1.

3.2. Mediating effect of courage

The mediating role of courage in the relationship between ER and WLI was examined through a three-step method suggested by Ref. [41]. The multiple regression equation incorporated the control variables such as gender, marital status, total working experience, and tenure of work under their immediate supervisor/doctor. Model 1 of Table 3 represented ER was positively related to courage after controlling the demographic variables such as gender, marital status, total working experience, and tenure of work under their immediate supervisor/doctor (β = 0.29, P < 0.05). In model 2, ER is found to be significantly related to WLI (β = 0.48, P < 0.01) after regulating for demographic variables. In model 3, the demographic variables, ER, and WLI were simultaneously entered into the model wherein courage was positively related to WLI (β = 0.42, P < 0.01). The coefficient weightage for ER was reduced from 0.48 to 0.39 when courage was added to the model, proving that courage partially mediates the relationship between ER and WLI (Table 3).

Table 3.

Courage as a mediator between emotional reflexivity and work-life integration (n = 249).

| Variables | Courage |

Work-life integration |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |

| Control variables | |||

| Gender | 0.05 | −0.03 | 0.02 |

| Marital status | −0.07∗ | −0.06 | −0.04 |

| Work experience | −0.05 | 0.07∗ | 0.05∗ |

| Tenure of work under immediate supervisor | −0.11∗∗ | 0.09∗ | 0.13 |

| Independent variable | |||

| Emotional reflexivity | 0.29∗ | 0.48∗∗ | 0.39∗∗ |

| Mediating variable | |||

| Courage | 0.42∗∗ | ||

| R2 | 0.18 | 0.27 | 0.33 |

| Δ R2 | 0.07 | ||

| F | 43.21∗ | 67.79∗∗ | 118.23∗∗ |

Note:Data are β. ∗P < 0.05;∗∗P < 0.01.

Bootstrapping was carried out using process macro to examine the direct and indirect effect of ER (through courage) on WLI. The bootstrapped estimations with 95% CI for direct and indirect influence are presented in Table 4. As shown in Table 4, the direct and indirect effect of ER (through courage) on WLI was significant, as the bootstrapped CI did not contain zero. The said results confirmed partial mediation effect of courage was prevailing in the association between ER and WLI.

Table 4.

Direct and indirect effect of emotional reflexivity (through courage) on work-life integration (n = 249).

| Effect | Path | Estimated effect | SE | Boot strapping (95% CI) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||

| Direct | ER→WLI | 0.29 | 0.04 | 0.36 | 0.23 |

| Indirect | ER→CU→WLI | 0.17 | 0.04 | 0.22 | 0.11 |

Note: ER = emotional reflexivity. CU = courage. WLI = work-life integration. SE = standard error.

4. Discussion

4.1. Theoretical implications for nursing research

By showing that ER is positively related to WLI and moral courage, we hope to draw the attention of researchers to the importance of conversation with the self and others to be self-aware of the current situation. EI and ER are important concepts covered under dynamic management, with both of them being used interchangeably. However, the present study negates the use of EI and ER as the same concept. This study hints out at the importance of ER on nursing actions and decision making. The authors suggest that more research should be carried on the conceptualization of ER and its application in nursing research through self-conversation or conversation with others. Further, the study has used integration as a continuum and not as an “either-or-proposition.”

Delving into boundary/border theory, the study has used different dimensions of WLI such as boundary transition, role transition, permeability, etc. Not surprisingly, the relationship between ER and WLI is not more accessible and is very complex. This complexity paves the way for further research on ER and WLI. ER is more of an intervention tool, and progress can be made by considering interactionist perspectives at the individual level. Detailed analysis is required for further investigation into providing clarity on boundary management, flexibility, and permeability. Thus, using ER as an intervention tool will lead to more intervention research testing different boundary transition strategies.

More research is also needed to investigate environmental contexts and family contexts for providing a more substantial base for boundary management. We posit the solid and complex interplay between ER and work-life boundaries involving personal preferences. In addition, moral courage is complex and multilayered. It takes a lot of practice to make courage a part of one’s innate character. Courage is a necessity for nurses. Hence, research should be conducted for all nursing fields to understand differences in experiencing courage with the heterogenous sample from mental health care, child nursing, midwives nursing. Further, male nurses should also be included to determine if they were more courageous than female nurses. Therefore, a difference in courage in different nursing settings and fields will have implications for developing courage among nurses across various areas.

4.2. Practical implications for nursing management

Self-awareness holds tremendous value in nursing as it helps nurses gain better knowledge of themselves and consequently helps build a better therapeutic relationship with the patients by providing an environment of trust and care [42]. Thus, owing to its importance, healthcare establishments can assist the nurses in improving self-awareness by enabling them to take mindfulness sessions. This practice will equip them to coexist peacefully with all the emotions they feel. Secondly, providing them with relevant resources and pieces of training – both offline and online can bolster self-awareness. On these lines, the pre-existing EI training programs can be used, and emphasis can be given to strengthening the dimension of self-awareness specifically. Additionally, developing self-awareness can even be integrated into the nurse training curriculum by nursing education institutes.

Having a positive self-identity becomes essential for nurses who are surrounded by several stressors continuously in a challenging work environment. A way to build a more positive self-identity and get relief from stress is by continuously monitoring one’s internal dialogue, which is more commonly known as self-talk. Nurses need to identify negative self-talk and modify that pattern for which professionals may be consulted. Other options include manually recording emotions as soon as a change in sentiment occurs or using online applications to ‘check-in’ moods at specified times of the day.

Moral courage is the foundation for ethical workplaces. ER can be used as a tool or a guide for individuals to navigate their paths when faced with new situations or a problem. This applies even when one faces ethical dilemmas. Therefore, to enhance moral competence and moral courage, educational programs (including continuing education programs) by health care institutions for their front-line workers need to be built and delivered. The best way to deliver these programs is in a team-based environment with the help of case studies. Healthcare establishments (similar to several consulting and auditing firms already do) can also appoint ethics or compliance officers who can act as the official channel for honest communication and reporting, handling grievances, and enforcing the organization’s code of conduct [43]. Steps need to be taken by healthcare setups to build a culture that encourages nurses to take ethical decision-making without fearing the adverse consequences of their actions. It also becomes vital for the healthcare industry to study and become aware of the factors that inhibit and support moral courage.

Self-awareness is essentially the first step towards WLI as well. Nurses need to acknowledge that WLI is a moving target and not something that is fixed throughout. Hence, heightened self-awareness will enable them to integrate work and life better as their roles, responsibilities, and priorities evolve. Self-awareness and a healthy self-identity also allow one to accept that work and life coexist and not compete. Healthcare establishments should undertake studies to understand how nurses have unique individual preferences when integrating work and life. The work-life strategies they offer should be tailor-made to cater to their personal preferences.

4.3. Limitations

The study is not without limitations. One of the limitations of this study is that the investigation conducted quantitative research giving a retrospective interpretation of the nurses’ experiences. Qualitative methods such as conversation with the respondents and diary-writing and unstructured interviews would provide deeper insight into the respondents experiencing reflexivity and their stance on moral courage. Further, this study took on a deductive approach where data were collected based on existing questionnaires. An inductive approach might render better results. Concepts like reflexivity and courage can be better understood in natural settings. Questionnaires may not bring out those responses that were experienced at some point in time. Hence the authors suggest that an interactionist approach in collecting data should be adopted. Further, there are many aspects of WLI and boundary management theory, viz. role transitions, flexibility, permeability, personal preferences, and other factors such as family condition and geographic location could not be addressed. Last but not least, a limitation of this study was due to the COVID-19 pandemic; it became difficult to reach out to more participants for the task.

5. Conclusion

The nursing profession cannot exist without ethical dilemmas, problems and conflicts. It is essential to develop firmness on one’s values and belief for strengthening moral courage to advocate those values. Given the association found between ER and WLI, our research concluded that coping with or achieving a better WLI requires the combination of ER by increasing self-awareness and moral courage of standing up to one’s personal and professional values by redefining one’s role in both the private and professional domain. We opine that reflexivity should not be used as a one-time solution but should be used as a strategy continuously to make moral courage a part of a nurse’s innate character to develop and solve ethical dilemmas.

Funding

No funding.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Lalatendu Kesari Jena: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Data curation, Investigation. Jeeta Sarkar: Writing – original draft. Saumya Goyal: Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Acknowledgement

The authors are thankful to XIM University Bhubaneswar and Dean, School of Human Resource Management, XIM University, Bhubaneswar for supporting this research.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Chinese Nursing Association.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnss.2021.06.001.

Contributor Information

Lalatendu Kesari Jena, Email: lkjena@xub.edu.in.

Jeeta Sarkar, Email: jeeta@stu.ximb.ac.in.

Saumya Goyal, Email: saumya@weqip.com.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Qian J., Wang H., Han Z.R., Wang J., Wang H. Mental health risks among nurses under abusive supervision:the moderating roles of job role ambiguity and patients' lack of reciprocity. Int J Ment Health Syst. 2015;9:22. doi: 10.1186/s13033-015-0014-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Drinkwater J., Tully M.P., Dornan T. The effect of gender on medical students' aspirations:a qualitative study. Med Educ. 2008;42(4):420–426. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2008.03031.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Al Hamadani A. The developmental level of the moral personality of university professors. Psychology and Education Journal. 2021;58(2):3217–3225. doi: 10.17762/pae.v58i2.2570. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nguyen L.H., Drew D.A., Graham M.S., Joshi A.D., Guo C.G., Ma W.J. Risk of COVID-19 among front-line health-care workers and the general community: a prospective cohort study. Lancet Public Heal. 2020;5(9):e475–e483. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30164-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.May C., Sibley A., Hunt K. The nursing work of hospital-based clinical practice guideline implementation: an explanatory systematic review using Normalisation Process Theory. Int J Nurs Stud. 2014;51(2):289–299. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2013.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Murray J.S. Moral courage in healthcare: acting ethically even in the presence of risk. Online J Issues Nurs. 2010;15(3) doi: 10.3912/OJIN.Vol15No03Man02. Manuscript 2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gallagher A. Moral distress and moral courage in everyday nursing practice. Online J Issues Nurs. 2011;16(2) doi: 10.3912/OJIN.Vol16No02PPT03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Epstein E.G., Whitehead P.B., Prompahakul C., Thacker L.R., Hamric A.B. Enhancing understanding of moral distress:the measure of moral distress for health care professionals. AJOB Empir Bioeth. 2019;10(2):113–124. doi: 10.1080/23294515.2019.1586008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Black S., Curzio J., Terry L. Failing a student nurse:a new horizon of moral courage. Nurs Ethics. 2014;21(2):224–238. doi: 10.1177/0969733013495224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sadooghiasl A., Parvizy S., Ebadi A. Concept analysis of moral courage in nursing:a hybrid model. Nurs Ethics. 2018;25(1):6–19. doi: 10.1177/0969733016638146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sternberg R.J., Conway B.E., Ketron J.L., Bernstein M. People's conceptions of intelligence. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1981;41(1):37–55. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.41.1.37. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Woodard C.R. Hardiness and the concept of courage. Consult Psychol J Pract Res. 2004;56(3):173–185. doi: 10.1037/1065-9293.56.3.173. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haase J.E. Components of courage in chronically ill adolescents:a phenomenological study. ANS Adv Nurs Sci. 1987;9(2):64–80. doi: 10.1097/00012272-198701000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Finfgeld D.L. Courage in middle-aged adults with long-term health concerns. Can J Nurs Res. 1998;30(1):153–169. https://cjnr.archive.mcgill.ca › article › download [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Finfgeld D.L. Becoming and being courageous in the chronically III elderly. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 1995;16(1):1–11. doi: 10.3109/01612849509042959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lachman V.D. Moral courage:a virtue in need of development? Medsurg Nurs. 2007;16(2):131. https://www.academia.edu/2968461/Moral_courage_a_virtue_in_need_of_development [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sekerka L.E., Bagozzi R.P. Moral courage in the workplace:moving to and from the desire and decision to act. Business Ethics. 2007;16(2):132–149. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8608.2007.00484.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Murray S.J.S. Moral courage in healthcare: acting ethically even in the presence of risk. OJIN: Online J Issues Nurs. 2010;15(3):1–9. https://docuri.com/download/prof-ad_59c1cf35f581710b2863c3c6_pdf [Google Scholar]

- 19.Numminen O., Repo H.N., Leino-Kilpi H. Moral courage in nursing:a concept analysis. Nurs Ethics. 2017;24(8):878–891. doi: 10.1177/0969733016634155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brandstätter V., Job V., Schulze B. Motivational incongruence and well-being at the workplace:person-job fit,job burnout,and physical symptoms. Front Psychol. 2016;7:1153. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sekerka L.E. 2015. Ethics is a daily deal:choosing to build moral strength as a practice. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cheshire M.H., Strickland H.P., Carter M.R. Comparing traditional measures of academic success with emotional intelligence scores in nursing students. Asia Pac J Oncol Nurs. 2015;2(2):99–106. doi: 10.4103/2347-5625.154090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Foster K., McCloughen A., Delgado C., Kefalas C., Harkness E. Emotional intelligence education in pre-registration nursing programmes:an integrative review. Nurse Educ Today. 2015;35(3):510–517. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2014.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Holmes M. Researching emotional reflexivity. Emot Rev. 2015;7(1):61–66. doi: 10.1177/1754073914544478. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Patton M.Q. Two decades of developments in qualitative inquiry. Qual Soc Work. 2002;1(3):261–283. doi: 10.1177/1473325002001003636. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maree J.G. Counselling for career construction: connecting life themes to construct life portraits: turning pain into hope. https://www.springer.com/gp/book/9789462092723 Brill Sense. 15-27.

- 27.Di Fabio A., Maree J.G. A psychological perspective on the future of work: promoting sustainable projects and meaning-making through grounded reflexivity. Counseling: Giornale Italiano di Ricerca e Applicazioni. 2016;9(3) psycnet.apa.org/record/2017-16408-001. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Savickas M.L. Career counseling: guida teorica e metodologica per il XXI secolo. www.docsity.com/it/career-counseling-guida-teorica-e-metodologica-per-il-xxi-secolo-mark-l-savickas-2014/2193559/ (Versione italiana a cura di A. Di Fabio). Trento, Italia: Erickson.

- 29.Hobfoll S.E. Plenum Press; New York: 1998. Stress, culture, and community: the psychology and philosophy of stress; p. 73. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wepfer A.G., Allen T.D., Brauchli R., Jenny G.J., Bauer G.F. Work-life boundaries and well-being:does work-to-life integration impair well-being through lack of recovery? J Bus Psychol. 2018;33(6):727–740. doi: 10.1007/s10869-017-9520-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Clark S.C. Work/family border theory: a new theory of work/family balance. Hum Relat. 2020;53(6):747–770. doi: 10.1177/0018726700536001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Day L. Courage as a virtue necessary to good nursing practice. Am J Crit Care. 2007 Nov;16(6):613–616. doi: 10.4037/ajcc2007.16.6.613. PMID: 17962506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Podsakoff P.M., MacKenzie S.B., Lee J.Y., Podsakoff N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research:a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J Appl Psychol. 2003;88(5):879–903. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.di Fabio A., Maree J.G., Kenny M.E. Development of the life project reflexivity scale:a new career intervention inventory. J Career Assess. 2019;27(2):358–370. doi: 10.1177/1069072718758065. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Numminen O., Katajisto J., Leino-Kilpi H. Development and validation of nurses' moral courage scale. Nurs Ethics. 2019;26(7–8):2438–2455. doi: 10.1177/0969733018791325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hair JF, Black WC, Anderson RE, Babin BJ. Multivariate data analysis (seventh ed., Vol. vol. 7). New York, NY: Pearson Education.

- 37.Arbuckle J.L. Amos Development Corporation, SPSS Inc; 2011. IBM SPSS Amos 20 user's guide. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hu L.T., Bentler P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis:conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Modeling:A Multidiscip J. 1999;6(1):1–55. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Marcoulides GA. Modern methods for business research. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- 40.Baron R.M., Kenny D.A. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research:conceptual,strategic,and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1986;51(6):1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rasheed S.P. Self-awareness as a therapeutic tool for nurse/client relationship. Int J Caring Sci. 2015;8(1):211–216. https://www.docin.com/p-1646673589.html [Google Scholar]

- 42.Willard J. What is a healthcare compliance officer? 2020. https://verisys.com/what-is-a-healthcare-compliance-officer/

- 43.Lufkin B. Why it's wrong to look at work-life balance as an achievement. 2021. https://www.bbc.com/worklife/article/20210302-why-work-life-balance-is-not-an-achievement

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.