Abstract

Many of the ligands for Toll-like receptors (TLRs) are unique to microorganisms, such that receptor activation unequivocally indicates the presence of something foreign. However, a subset of TLRs recognizes nucleic acids, which are present in both the host and foreign microorganisms. This specificity enables broad recognition by virtue of the ubiquity of nucleic acids but also introduces the possibility of self-recognition and autoinflammatory or autoimmune disease. Defining the regulatory mechanisms required to ensure proper discrimination between foreign and self-nucleic acids by TLRs is an area of intense research. Progress over the past decade has revealed a complex array of regulatory mechanisms that ensure maintenance of this delicate balance. These regulatory mechanisms can be divided into a conceptual framework with four categories: compartmentalization, ligand availability, receptor expression and signal transduction. In this Review, we discuss our current understanding of each of these layers of regulation.

Subject terms: Infectious diseases, Toll-like receptors, Autoimmunity

Activation of nucleic acid-sensing Toll-like receptors is finely tuned to limit self-reactivity while maintaining recognition of foreign microorganisms. The authors describe recent progress made in defining the regulatory mechanisms that facilitate this delicate balance.

Introduction

Toll-like receptors (TLRs) are a family of innate immune receptors whose activation is crucial for the induction of innate and adaptive immune responses. Expression of TLRs in antigen-presenting cells links the recognition of pathogens both to the induction of innate immune effector mechanisms that limit pathogen replication and to the initiation of adaptive immunity1. TLRs recognize conserved microbial features shared by broad pathogen classes, which enables a limited set of receptors to recognize the tremendous diversity of microorganisms potentially encountered by the host. Five mammalian TLRs can be activated by nucleic acid ligands (referred to here as NA-sensing TLRs): TLR3 recognizes double-stranded RNA; TLR7, TLR8 and TLR13 recognize fragments of single-stranded RNA with distinct sequence preferences; and TLR9 recognizes single-stranded DNA containing unmethylated CpG motifs. NA-sensing TLRs are particularly relevant for the detection of viruses because viruses generally lack other common, invariant features that are suitable for innate immune recognition. However, NA-sensing TLRs can also detect nucleic acids from other pathogen classes, and each of these receptors has been implicated in the host response to diverse pathogens (Table 1).

Table 1.

Key examples of pathogen recognition by nucleic acid-sensing Toll-like receptors

| Receptor | Ligand specificity | Class of pathogen recognized | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| TLR3 | dsRNA | dsRNA viruses | Reovirus |

| ssRNA viruses | Respiratory syncytial virus, hepatitis C virus | ||

| DNA viruses | HSV-1, HSV-2, vaccinia virus | ||

| Retroviruses | HIV-1 | ||

| Bacteria | Lactic acid-producing bacteria | ||

| Protozoa | Neospora caninum | ||

| TLR7 and TLR8 | ssRNA and RNA breakdown products | ssRNA viruses | Influenza A virus, SARS-CoV |

| Retroviruses | HIV-1 | ||

| Bacteria | Group B streptococcus, Borrelia burgdorferi | ||

| Fungi | Candida spp. | ||

| Protozoa | Leishmania major | ||

| TLR9 | ssDNA (containing CpG motifs) | DNA viruses | HSV-1, HSV-2, HPV, adenovirus |

| Bacteria | Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serovar Typhimurium, Mycobacterium tuberculosis | ||

| Fungi | Aspergillus fumigatus, Candida spp. | ||

| Protozoa | Plasmodium falciparum, Leishmania major | ||

| TLR13 (mice) | ssRNA | Bacteria | Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pneumoniae |

| ssRNA viruses | Vesicular stomatitis virus |

ds, double-stranded; HPV, human papillomavirus; HSV, herpes simplex virus; SARS-CoV, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus; ss, single-stranded; TLR, Toll-like receptor.

Targeting nucleic acids greatly expands the breadth of microorganisms that can be recognized by TLRs but comes with the trade-off of potentially sensing self-nucleic acids. Indeed, improper activation of NA-sensing TLRs by self-nucleic acids has been linked to several autoimmune and autoinflammatory disorders, including systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and psoriasis2–8. One possible strategy for limiting such adverse outcomes is recognition of specific features that distinguish foreign nucleic acids from self-nucleic acids. However, although ligand preferences based on sequence or chemical modifications do reduce the likelihood of TLR responses to self-nucleic acids, discrimination between foreign and self-nucleic acids is not based solely on these differences9,10. NA-sensing TLRs also rely on mechanisms that reduce the likelihood that they will encounter self-nucleic acids and/or dampen the response when self-nucleic acids are nevertheless detected. These mechanisms collectively set a precisely tuned threshold for receptor activation: too low a threshold would result in sensing of self-nucleic acids and autoimmunity, whereas too high a threshold would hinder defence against the very pathogens that the NA-sensing TLRs aim to detect (Fig. 1). Recent research has shown that multiple mechanisms function together to determine this threshold for a given TLR. The picture emerging from these studies is becoming quite complex, as each NA-sensing TLR is subject to distinct modes of regulation, suggesting that the ‘solution’ to the problem of self versus non-self discrimination may be different for each TLR. Such receptor-specific regulation probably explains the differences in the relative contributions of different NA-sensing TLRs to autoimmune diseases. For example, inappropriate activation of TLR7 by self-nucleic acid is much more consequential than TLR9 activation in animal models of SLE, even though both TLR7 and TLR9 can contribute to pathology11–13. Although the field has taken initial steps towards identifying the molecular basis of this specialized regulation, substantial additional work is needed to determine how such closely related receptors can make different contributions to disease outcomes.

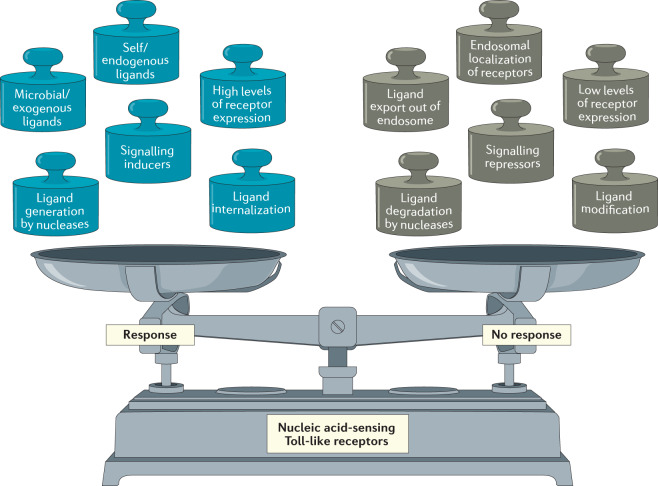

Fig. 1. The activation of nucleic acid-sensing Toll-like receptors is finely balanced by a complex array of regulatory mechanisms.

The nucleic acid-sensing Toll-like receptors (NA-sensing TLRs) are capable of sensing a wide variety of potential pathogens, but this breadth of recognition comes at the potential cost of autoimmunity induced by host nucleic acids. Activation of these receptors must therefore be carefully balanced, such that they remain inactive under homeostatic conditions but are still sensitive to increases in endosomal levels of nucleic acids that could indicate the presence of microorganisms. Each weight on the left-hand side of the scale represents a known input that drives the activation of NA-sensing TLRs, whereas the weights on the right-hand side represent known restraints on TLR activation.

With these questions in mind, here, we review our understanding of the mechanisms controlling activation of, and signalling by, NA-sensing TLRs. We believe that this discussion is timely, as several strategies to modulate NA-sensing TLR responses, both positively and negatively, are being pursued therapeutically (Box 1). We discuss the four categories of regulatory mechanism that influence NA-sensing TLR responses: compartmentalization, ligand availability, receptor expression and signal transduction.

Box 1 Nucleic acid-sensing Toll-like receptors as therapeutic targets.

Therapeutics that modulate nucleic acid-sensing Toll-like receptor (NA-sensing TLR) responses are being pursued in several contexts (reviewed extensively in ref.117). Because the ligands for these receptors are relatively small and easy to synthesize, progress in generating synthetic agonists or inhibitors has been rapid relative to other TLRs.

Numerous clinical trials are testing the efficacy of agonists for TLR3, TLR7, TLR8 and TLR9 in contexts where increased activation of innate and adaptive immune responses should be beneficial. These trials can be broadly grouped into two categories: adjuvants for vaccines targeting infectious disease and therapies aimed at boosting immune responses against cancer. The TLR9 agonist CpG 1018 is FDA-approved as an adjuvant in the hepatitis B vaccine HEPLISAV-B118, and several additional TLR agonist compounds are being tested in vaccines against viral pathogens117. Two potent vaccines for coronavirus disease 19 (COVID-19), developed by Moderna and Pfizer/BioNTech, are mRNA-based vaccines that probably trigger an immune response at least in part through stimulation of NA-sensing TLRs. By contrast, the use of NA-sensing TLR agonists to boost anticancer immune responses has been met with only limited success so far. Currently, the only FDA-approved TLR agonist for treatment of cancer is imiquimod, an agonist for TLR7 and for the NLRP3 inflammasome, which is used to treat basal cell carcinoma, but many agonists for TLR3, TLR7, TLR8 and TLR9 are being tested for efficacy against various types of cancer. Most of these trials involve combining TLR agonists with therapeutics that block one or more immune checkpoints.

Antagonists of TLR7, TLR8 and TLR9 are being pursued to treat autoimmune disorders, such as systemic lupus erythematosus and psoriasis, in which activation of these TLRs has been implicated in disease pathology or progression. Unfortunately, although antagonists for TLR7 and TLR9 produced promising results in preclinical models, clinical trials focused on systemic lupus erythematosus have failed to meet primary end points117. Trials focused on psoriasis have been more promising. The modest success of these therapeutics probably reflects the complex aetiology of these diseases and underscores the importance of increasing our understanding of the mechanisms that control TLR regulation and function.

Compartmentalization

Activation of all NA-sensing TLRs is restricted to endosomes, and this intracellular compartmentalization is crucial for both their function and their regulation (Fig. 2). NA-sensing TLRs encounter pathogen-derived nucleic acids when microorganisms are internalized and degraded, either through endocytosis or phagocytosis14,15. This mode of recognition enables cells to detect pathogens without being infected, which reduces the likelihood that pathogens can inhibit TLR-mediated induction of immunity. By contrast, cytosolic sensors of nucleic acids can generally detect pathogen ligands only when cells are directly infected, which makes them more prone to interference from pathogen evasion strategies.

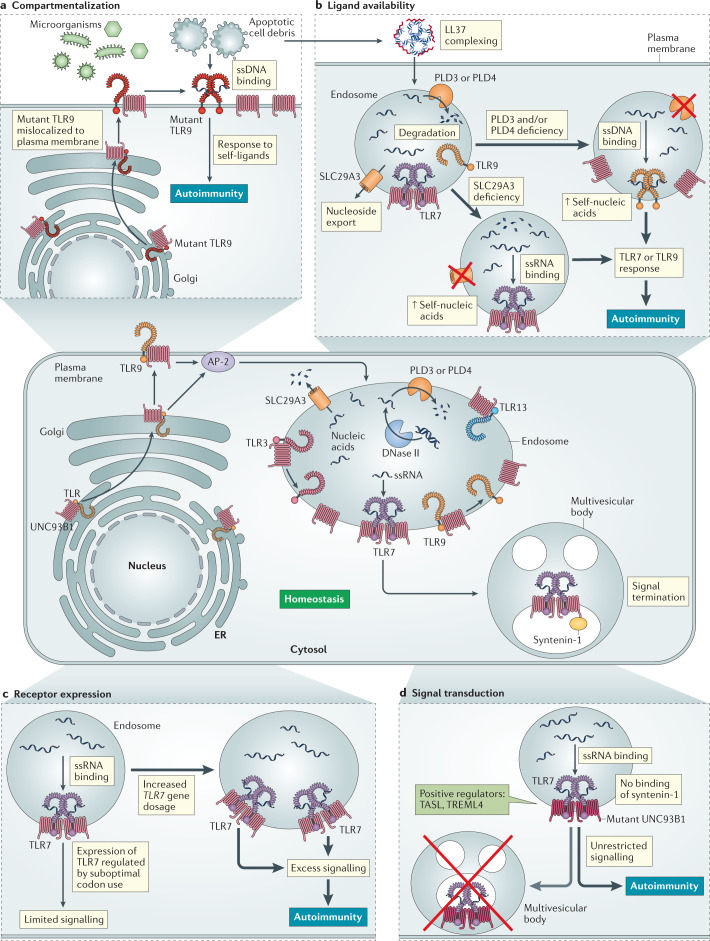

Fig. 2. The four categories of regulatory mechanisms for nucleic acid-sensing Toll-like receptors.

At homeostasis (centre panel), multiple regulatory mechanisms — compartmentalization, ligand availability, receptor expression and signal transduction — function collectively to limit the responses of nucleic acid-sensing Toll-like receptors (NA-sensing TLRs) to self-nucleic acids, while preserving responses to microbial nucleic acids. All NA-sensing TLRs require the transmembrane protein UNC93B1 to exit the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), where they are translated, and traffic via the classical secretory pathway to endosomes. To reach an endosome, TLR9 must first traffic to the plasma membrane, where it is internalized by adaptor protein complex 2 (AP-2)-mediated endocytosis. UNC93B1 also mediates regulatory functions after exit from the ER. For example, TLR3 and TLR9 are released from UNC93B1 in the endosome, whereas TLR7 remains associated. This subjects TLR7 to additional regulation through binding of syntenin-1 to UNC93B1, which leads to sorting of the UNC93B1–TLR7 complex to multivesicular bodies and termination of signalling. The fate of UNC93B1–TLR13 complexes in endosomes is currently not known. The distinct stoichiometry of dimeric UNC93B1–TLR7 complexes, compared with monomeric UNC93B1–TLR3 complexes, is also depicted. Breakdown of these regulatory mechanisms has been linked to the induction of autoimmunity and/or autoinflammation. For each category of regulatory mechanism, representative examples of how that regulation can break down are indicated. Detailed discussions of additional examples are provided in the main text. a | Compartmentalization. Mislocalization or defective compartmentalization of mutant TLR9 enables recognition of extracellular self-DNA. b | Ligand availability. Association of self-DNA and self-RNA with the antimicrobial peptide LL37 promotes their uptake into endosomes and reduces degradation by nucleases. Loss of the membrane-anchored 5′ exonucleases phospholipase D3 (PLD3) and PLD4 or of the nucleoside exporter SLC29A3 increases the availability of self-nucleic acids within endosomes and triggers activation of TLR9 or TLR7, respectively. c | Receptor expression. Overexpression of TLR7 increases the number of receptors in endosomes, which enables responses to otherwise non-stimulatory levels of self-RNA. d | Signal transduction. Loss of syntenin-1 binding to mutant UNC93B1 disrupts the sorting of UNC93B1–TLR7 complexes into multivesicular bodies, which is required to restrict TLR7 responses to self-RNA. Positive regulators of NA-sensing TLRs, such as TASL and TREML4, can enhance downstream signalling. ssDNA, single-stranded DNA; ssRNA, single-stranded RNA.

Localization of NA-sensing TLRs to endosomes also achieves a crucial regulatory function by sequestering these receptors away from self-nucleic acids. The importance of this sequestration was first demonstrated by the finding that certain types of immune cell that are normally unresponsive to self-nucleic acids can be activated if these ligands are efficiently delivered to endosomes7,16. This concept is further illustrated by studies in which NA-sensing TLRs have been mislocalized to the plasma membrane, which increases their access to extracellular nucleic acids17. Mice engineered to express mislocalized TLR9 have fatal systemic inflammation and anaemia18,19. These examples illustrate the importance of mechanisms that limit the activation of NA-sensing TLRs to endosomes. In the following sections, we discuss our current understanding of how such compartmentalization is achieved.

Receptor trafficking

The NA-sensing TLRs are translated at the endoplasmic reticulum and trafficked via the classical secretory pathway to endosomes14. Trafficking itself is a regulatory mechanism, as the number of functional TLRs in endosomes and lysosomes influences the receptor activation threshold. It is beyond the scope of this Review to cover all aspects of the trafficking of NA-sensing TLRs, which have been reviewed in detail elsewhere (for example, refs14,15), but we highlight the key players and the latest developments.

All NA-sensing TLRs require the 12-pass transmembrane protein UNC93B1 to exit the endoplasmic reticulum and traffic to endosomes20–22. UNC93B1 stays associated with NA-sensing TLRs during their trafficking, and it is now clear that UNC93B1 also mediates regulatory functions after exit from the endoplasmic reticulum21,23–25. For example, the association of UNC93B1 with NA-sensing TLRs is essential for their stability in and beyond the endoplasmic reticulum23. Non-functional alleles of UNC93B1 that abolish interaction with NA-sensing TLRs result in reduced receptor stability, failure of export from the endoplasmic reticulum and loss of function22,23,26. These findings have clinical relevance, as humans with loss-of-function mutations in UNC93B1 are non-responsive to ligands for NA-sensing TLRs and show increased susceptibility to certain viruses27. Missense mutations in UNC93B1 can alter the trafficking of NA-sensing TLRs, leading to marked functional consequences. For example, the D34A mutation in UNC93B1 leads to preferential export of TLR7 from the endoplasmic reticulum at the expense of TLR9, which presumably increases the amount of TLR7 within endosomes28. This increase in the level of ‘functional’ TLR7 is sufficient to trigger lethal inflammation in mice29. That a single point mutation in this crucial chaperone is sufficient to disrupt the distribution of NA-sensing TLRs underscores the carefully tuned and interconnected nature of NA-sensing TLR regulation.

Although the NA-sensing TLRs all localize to endosomes, the trafficking routes they use, as well as the nature of the compartments where they ultimately reside, are surprisingly diverse. The process of dissecting the mechanisms responsible for this diversity remains in its infancy, but some insight has been gained from recent studies. S100A9, a calcium-binding and zinc-binding protein, has been identified as a regulator of TLR3 compartmentalization but is not required for the trafficking of other TLRs. The S100A9–TLR3 interaction is crucial for the distribution of TLR3 in late endosomes, and accordingly, S100A9 deficiency in mice leads to a reduced response to the TLR3 agonist polyinosinic:polycytidylic acid (polyI:C)30. The mechanism by which S100A9 specifically controls TLR3 trafficking to late endosomes remains unclear. There is also evidence that TLR7 and TLR9 are subject to distinct trafficking regulation. To reach endosomes, TLR9 must first traffic to the plasma membrane, where it is then internalized into endosomes by adaptor protein complex 2 (AP-2)-mediated endocytosis21. By contrast, TLR7 does not require this AP-2-mediated step but instead can interact with AP-4, which suggests that TLR7 may traffic directly from the Golgi to endosomes21. For each of these examples, the biological relevance of such differential trafficking remains unclear, and further studies are needed to dissect the importance of such regulation.

There are clear examples of functional specialization owing to the regulated trafficking of NA-sensing TLRs, which illustrate the potential of this line of research. In plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs) (Box 2), the localization of TLR7 and TLR9 is further controlled by AP-3, which moves these TLRs into a specialized type of lysosome-related organelle from which TLR signalling leads to the transcription of type I interferon (IFN) genes31,32. Trafficking of TLR9 to this specialized endosome also requires phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate 5-kinase33. Interestingly, there is growing evidence that the machinery controlling trafficking of TLR7 and TLR9 to this compartment is distinct. For example, TLR7-driven IFNα production by pDCs requires a cellular redistribution of TLR7-containing lysosomes mediated by linkage to microtubules34. The GTPase ARL8B is required for this redistribution of TLR7, but TLR9-induced IFNα production occurs independently of this mechanism34. pDCs also use a process known as LC3-associated phagocytosis for the formation of the TLR9–IFN signalling cascade in response to DNA-containing immune complexes35. The distinct modes by which each NA-sensing TLR populates the endosomal network suggest a granular level of sorting with potentially profound functional consequences. The lack of definitive molecular markers for some of these specialized endosomal organelles and the challenge of isolating such compartments for biochemical analyses have slowed progress in this field.

Box 2 Cell-type-specific regulation of nucleic acid-sensing Toll-like receptors.

Expression levels of the nucleic acid-sensing Toll-like receptors (NA-sensing TLRs) can differ between cell types, and signalling and regulatory differences specific to a given cell type can further tailor the output of TLR activation.

Plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs) are the prototypical example of specialized regulation of NA-sensing TLRs. In response to stimulation through TLR7 or TLR9, pDCs produce type I and type III interferons (IFNs), in contrast to other cell types that mainly produce nuclear factor-κB-dependent cytokines in response to TLR7 or TLR9 ligands119. This specialized signalling in pDCs probably ensures that antiviral IFNs are produced during viral infections because pDCs need not be infected to detect viral nucleic acids; by contrast, cytosolic sensing pathways for nucleic acids are often directly antagonized by viral proteins expressed in infected cells. Relevant and crucial to their ability to produce type I and type III IFNs is the expression of members of the IFN response factor (IRF) family by pDCs120,121, as well as several other specialized signalling mechanisms122–124.

There is also evidence of specialized signalling by NA-sensing TLRs in B cells. TLR signalling can lead to B cell proliferation and antibody production, and certain unique aspects of signal transduction in B cells have been identified as being crucial for these responses. Responses to TLR9 ligands require the adaptor protein DOCK8, which links TLR9 activation to activation of the transcription factor STAT3 (ref.125). B cell responses are impaired in patients with mutations in DOCK8 (refs125,126). Another example has been revealed by studies of diffuse large B cell lymphoma. A subset of these tumours depends on mutations in the TLR adaptor MYD88, which drives a TLR9-dependent proliferative and survival signal127. Whether these signalling features apply to other NA-sensing TLRs in B cells remains to be seen, as does the extent to which they operate in untransformed cells.

Certain cell types limit responses to nucleic acids by lacking expression of NA-sensing TLRs. To prevent aberrant responses to self-nucleic acids within engulfed cells, tissue-resident macrophages do not express TLR9 and also repress signalling from endosomal TLRs, while maintaining signalling from extracellular TLRs96,128. These mechanisms probably prevent autoinflammation or autoimmunity driven by a cell type with particularly high levels of exposure to endogenous ligands. Similarly, TLR7 and TLR9 are not expressed in intestinal epithelial cells, perhaps preventing aberrant immune responses in the ligand-rich environment of the gut microbiota129.

Receptor processing

The compartmentalized activation of NA-sensing TLRs is reinforced by a requirement that their ectodomains undergo proteolytic processing before they can respond to ligands36,37. Specific proteases have been implicated in ectodomain processing36–40, but it is likely that many enzymes can mediate this required step. Although uncleaved TLRs can still bind to ligands, it is clear that processing is a prerequisite for stabilization of receptor dimers and activation36,41. Proteolytic processing occurs most efficiently in the acidic environment of endosomes and lysosomes. As a result, the NA-sensing TLRs are inactive in the endoplasmic reticulum and during trafficking, which further reduces the chance of stimulation by self-nucleic acids (Fig. 2). Human TLR7 and TLR8 can also be cleaved at a neutral pH by furin-like proprotein convertases, which suggests that they may become functional before reaching the acidic environment of endolysosomes42,43. The consequences of this potential ‘early’ activation of TLR7 and TLR8 in humans, if any, have not been determined.

Ligand availability

The compartmentalization of NA-sensing TLRs as a strategy to achieve self versus non-self discrimination relies on complementary mechanisms that control ligand availability within endosomes. Several factors influence the amount of nucleic acids within endosomes and determine whether those nucleic acids are capable of activating TLRs. Nucleases can reduce the availability of self-nucleic acids (Fig. 2), but ligand digestion as a means of negative regulation of the NA-sensing TLRs is nuanced because nucleic acids can be self or microbial. Furthermore, the ligands for some NA-sensing TLRs are very small RNA fragments (Box 3), so degradation of self-nucleic acids may not always prevent recognition and may even facilitate it. Similarly, the digestion of microbial nucleic acids can also promote recognition by generating molecules that are capable of activating TLRs.

Although our current understanding makes it challenging to place the mechanisms affecting ligand availability into a unified conceptual framework, we find it useful to group such mechanisms into four general categories: nucleic acid digestion that reduces the concentration of activating ligands, internalization of ligands, nucleic acid digestion that generates activating ligands, and physical sequestration of ligands out of the endosome. Together, these four categories of regulation establish the levels of available ligands within endosomes, which contributes to the balance between sensing potential pathogens and avoiding recognition of self-nucleic acids (Fig. 1).

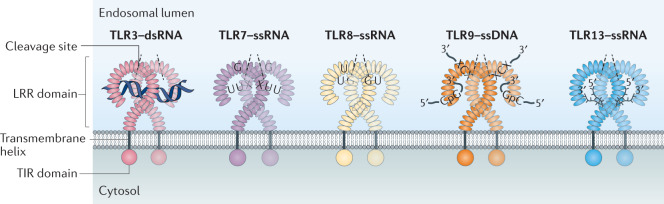

Box 3 Structural features of ligand recognition by nucleic acid-sensing Toll-like receptors.

The nucleic acid-sensing Toll-like receptors (NA-sensing TLRs) have common structural features, including an extracellular leucine-rich-repeat (LRR) domain that binds ligand, a transmembrane helix and a cytosolic Toll/IL-1 receptor (TIR) domain (see the figure). Ligand binding induces dimerization of the TLR and activation of downstream signalling pathways.

Ligands for TLR3 have the longest length requirement of the NA-sensing TLRs, with a minimum of 40 bp of double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) being necessary for activation. The dsRNA segment spans the two ligand-binding sites that are located on opposite ends of each TLR3 ectodomain130,131. By contrast, activation of TLR7 can occur with simple single-stranded RNA (ssRNA) ligands that require only one guanosine nucleoside at the first ligand-binding site together with a minimum of a ssRNA trimer containing a uridine dimer (UUX) at the second ligand-binding site78,132. Ligand binding by TLR8 is quite similar to TLR7, but with a preference for binding uridine in the first binding site and UG dimers in the second binding site77,133.

CpG motifs within a DNA segment are necessary for activation of TLR9 (ref.41), but the motifs that induce maximum stimulation differ between mice and humans134,135. A second binding site in TLR9 for 5′-XCX DNAs cooperatively promotes receptor dimerization, together with CpG DNA. This second site has similarities with the nucleoside-binding pockets in TLR7 and TLR8, which highlights a common feature of ligand recognition by NA-sensing TLRs. Binding of the two sites in TLR9 can be achieved by a single DNA molecule, with spacing of at least 10 bp between the 5′-XCX and CpG motifs, or by two distinct DNA segments136.

Unlike the other NA-sensing TLRs, ligand recognition by TLR13 is sequence specific. The 13-nucleotide ssRNA ligand for TLR13 (5′-XCGGAAAGACCXX-3′) has been identified in a conserved region of bacterial 23S ribosomal RNA and similar ssRNA sequences in viruses74,75,99,137.

Digestion of nucleic acids to limit ligand availability

In recent years, investigators have identified multiple nucleases, the absence of which leads to sensing of self-nucleic acids as well as the onset of autoimmunity in both mice and humans. DNase I-like 3 (DNASE1L3), a secreted DNA endonuclease, has a positively charged carboxy-terminal peptide that enables it to access apoptotic cell microparticles and digest the DNA within44. Mutations in this nuclease lead to a form of paediatric SLE in humans45, and mice lacking DNASE1L3 develop autoimmunity that is driven synergistically by TLR7 and TLR9 (refs44,46). The contribution of TLR7, an RNA sensor, is unexpected and could be owing to the reported capacity of TLR7 to respond also to deoxyguanosine47 or to the functional competition between TLR7 and TLR9 that has been previously described28,29,48.

Deficiencies in other nucleases cause severe autoinflammation that manifests earlier in life. Phospholipase D3 (PLD3) and PLD4 were recently identified as membrane-anchored 5′ exonucleases that degrade TLR9 ligands within endolysosomes2. Mice lacking either enzyme develop TLR9-dependent and IFNγ-dependent inflammatory disease; mice lacking both PLD3 and PLD4 develop severe disease that is fatal early in life2, similar to the disease that develops when mice express mislocalized TLR9, the activation of which is no longer restricted to endosomes19. Mice lacking DNase II, another endolysosomal endonuclease, also develop severe disease in utero49. In contrast to the TLR9-dependent disease in PLD3-deficient and PLD4-deficient mice, the embryonic lethality of DNase II-deficient mice can be attributed to activation of the cGAS–STING pathway upon endosomal rupture and can be rescued by eliminating type I IFN signalling49–51. However, in these rescued mice, the accumulation of self-DNA in endosomes leads to TLR-dependent autoantibody production, arthritis and splenomegaly, and deficiency in UNC93B1 reduces this residual disease52–54.

In addition to these examples, it is likely that other nucleases are also involved in preventing the induction of NA-sensing TLR-dependent autoimmunity. An obvious candidate is another secreted DNase, DNase I; mice and humans with DNase I deficiency have symptoms of SLE but this disease has not yet been linked directly to aberrant TLR activation55,56.

The examples discussed above involve enzymes that metabolize DNA but not RNA. Does an analogous group of RNases digest potential RNA ligands for TLR3, TLR7, TLR8 and TLR13? The RNase A family is one possible candidate, and overexpression of RNase A proteins reduces disease in a TLR7-dependent model of autoimmunity57. However, existing single knockouts of RNase A family members do not cause autoinflammation or autoimmunity58,59. Functional redundancy between family members may mask phenotypes in these contexts. Studies to overcome this limitation, perhaps by knocking out multiple RNases at the same time, have not been carried out to our knowledge. Alternatively, it is possible that the RNA-sensing TLRs are more reliant on alternative modalities of regulation, such as the physical sequestration mechanisms described below.

The distinct timelines of disease triggered by deletion of the genes that encode these nucleases are also compelling. In contrast to autoimmune diseases triggered by TLR7 and TLR8, TLR9-dependent autoinflammation develops in utero or extremely early in life. It is possible that TLR9 is simply expressed at an earlier time in development than TLR7 or TLR8 and therefore is capable of driving disease earlier. Alternatively, this observation may hint that early development is particularly sensitive to the loss of enzymes that are responsible for degrading DNA ligands rather than RNA ligands. The rapid tissue development and remodelling early in life, accompanied by increased apoptosis, could explain why digestion of potential TLR9 ligands is particularly crucial at this time point.

Internalization of ligands

Another factor that influences the ligand availability for activation of NA-sensing TLRs is the extent to which ligands are internalized by cells. The uptake of microorganisms varies across cell types; macrophages and dendritic cells are highly phagocytic, whereas certain other cell types are most likely to internalize microorganisms only when specific receptor–ligand interactions occur. For example, B cells are generally poor at acquiring antigen but will readily internalize antigens bound by their B cell receptor.

Receptor-mediated uptake of ligands also affects responses to self-nucleic acids. The first demonstration of this principle was made in the context of B cells expressing a B cell receptor specific for self-immunoglobulin. These B cells internalize immune complexes containing self-DNA or self-RNA, leading to synergistic activation of B cells through TLR9 or TLR7 and the B cell receptor16,60. This mechanism effectively ‘breaks’ the receptor compartmentalization achieved through localization of NA-sensing TLRs to endosomes. A similar uptake of immune complexes containing self-nucleic acids can occur via engagement of Fc receptors on dendritic cells61,62. Other receptors, such as the receptor for advanced glycosylation end products (RAGE)63–65, have also been implicated in uptake and delivery of nucleic acids to NA-sensing TLRs.

Another mechanism that facilitates cellular uptake of and aberrant responses to extracellular self-nucleic acids is the formation of complexes between self-nucleic acids and certain self-proteins. The clearest example of this concept is the association of self-DNA and self-RNA with the antimicrobial peptide LL37 (also known as CAMP)7,66. This interaction condenses the nucleic acids, promoting uptake into endosomes and reducing degradation by nucleases. LL37-complexed self-RNA and self-DNA potently stimulate TLR7 and TLR9 in pDCs, leading to type I IFN production. This mechanism is particularly relevant to the recognition of neutrophil extracellular traps. Neutrophils express high levels of LL37, and neutrophil extracellular traps seem to be a major source of self-nucleic acids in the context of autoimmune diseases such as SLE and psoriasis67–69. Additional proteins, such as HMGB1, have also been shown to bind to self-nucleic acids and protect them from digestion by nucleases64,70.

Processing of nucleic acids to generate ligands

The degradative environment of the endosome has an important role in breaking down microorganisms to expose their nucleic acids, but there is accumulating evidence that recognition of nucleic acids in some cases requires further processing by nucleases to generate ligands that can activate TLRs. The lysosomal endoribonucleases RNase T2 and RNase 2 function upstream of human TLR8-dependent RNA recognition, cleaving before and after uridine residues to generate TLR8 ligands from the RNA of certain pathogens71,72. DNase II, described above as a nuclease that is required to prevent responses to self-DNA, is also required to generate TLR9 ligands in some contexts53,54,73. DNase II-deficient cells, also lacking the type I IFN receptor to prevent lethality, fail to respond to CpG-A, which assembles into large oligomers, whereas responses to less complex CpG-B ligands are unaffected73. Similar analyses have revealed that other sources of DNA, such as Escherichia coli genomic DNA and even self-DNA, require processing by DNase II before TLR9 recognition53,54. Thus, DNase II provides an example of the nuanced nature of ligand processing as it functions to prevent the accumulation of DNA in some contexts while at the same time generating ligands that can stimulate TLR9.

Whether stimulation of the other NA-sensing TLRs requires ligand digestion by specific nucleases remains an open question. TLR13 recognizes bacterial ribosomal RNA sequences that are embedded within the ribosome and therefore are not readily accessible74,75. This specificity implies that some level of ligand processing must take place for TLR13 to be activated by bacterial ribosomal RNA. However, a specific nuclease that is required for this processing has not yet been discovered. This example, as well as the digestion of pathogen-derived RNA by RNase T2 and RNase 2 described above, highlights a prime area for future research — to determine how ligands derived from pathogens, rather than synthetic ligands, are processed and made available to the NA-sensing TLRs.

Ligand sequestration

TLR7 and TLR8 can recognize extremely short fragments of RNA and, in some cases, even single nucleosides47,76–78 (Box 3), so digestion of nucleic acids does not completely solve the problem of potential recognition of self-nucleic acids. In other words, nucleases may not be able to digest RNA ligands to the extent that they can no longer be recognized by TLR7 and TLR8. An additional mechanism that reduces the concentration of RNA in endosomes is the transport of ligands out of the endosomal lumen and into the cytosol. One clear example of this principle comes from recent preprint data of mice lacking SLC29A3, a member of the solute carrier family that functions to maintain nucleoside homeostasis. These mice accumulate endosomal nucleosides and develop disease with many of the hallmarks observed in other models of TLR7 dysregulation79. SLC29A3-deficient mice and humans have other abnormalities, most likely related to altered nucleoside homeostasis80–83, but much of the autoimmune pathology in mice is rescued by TLR7 deficiency79. This example further illustrates how fundamental homeostatic mechanisms contribute to the carefully balanced recognition system of endosomal TLRs.

A second example of ligand sequestration involves the export of double-stranded RNA from endosomes. SIDT1 and SIDT2, which are the mammalian orthologues of the SID-1 double-stranded RNA transporter in Caenorhabditis elegans, are present in the endosome and facilitate transport of double-stranded RNA into the cytoplasm84,85. Mice deficient in SIDT2 have enhanced TLR3-mediated signalling, which indicates that physical sequestration of double-stranded RNA by SIDT2 can help to dampen TLR3 responses84. However, the enhanced TLR3 signalling in this model does not result in overt disease, which may indicate that accumulation of endosomal double-stranded RNA self-ligands is not problematic at steady state.

An open question is whether similar transporters exist to remove ligands for TLR9 or TLR13 from the endosome. Ligand digestion may be more important for regulating these NA-sensing TLRs, as they generally recognize longer nucleic acids than TLR7 or TLR8. Finally, it is unclear whether these transporters interfere with the ability of NA-sensing TLRs to recognize foreign nucleic acids by also reducing the availability of microbial ligands. There may be an additional, undiscovered layer of regulation that prevents microbial nucleic acids from being transported out of the endosome and thus avoiding recognition. It is also possible that microbial nucleic acids are occasionally transported from the endosome but that this is a worthwhile trade-off to prevent the induction of autoimmunity. Alternatively, the presence of pathogen-derived nucleic acids may increase overall ligand concentration enough to overcome the effect of export by transporters.

Receptor expression

The previous sections describe how NA-sensing TLRs localize to intracellular compartments separate from the majority of extracellular nucleic acids and how ligand digestion and sequestration reduce the concentration of self-nucleic acids that do reach the endosome. Collectively, these two categories of regulation operate to reduce the likelihood that a given NA-sensing TLR will encounter self-nucleic acids. Another component of this system is regulation of TLR expression, which determines the number of receptors in a given cell and, in combination with trafficking regulation, the number of receptors in the endosome available for ligand recognition. Maintaining low levels of TLR expression makes sense conceptually, as the concentrations of both ligand and receptor within the endosome determine the activation threshold for each TLR (Fig. 1). Increased levels of either will favour TLR activation and the induction of aberrant responses to self-nucleic acids. However, if expression of TLRs is too low, then responses to microbial ligands become compromised.

Relatively little is known about the molecular mechanisms that regulate expression of the NA-sensing TLRs. Most TLR transcripts contain a high frequency of suboptimal codons, which limits the number of NA-sensing TLRs present in the endosome86,87. For TLR7, this suboptimal codon usage regulates expression by altering the rates of translation and transcription and by modulating RNA stability21,87. TLR9 is an outlier among the TLRs, with super-optimal codon usage86,87. The fact that TLR9 does not require this additional limitation on receptor levels imposed by suboptimal codon usage aligns with the observation, discussed below, that TLR9 overexpression does not induce autoimmunity.

Despite the lack of information regarding the underlying mechanisms that control TLR expression, there is no doubt that maintaining low levels of certain NA-sensing TLRs is necessary to avoid autoimmunity. In mice and humans, increasing gene dosage of TLR7 and/or TLR8, both located on the X chromosome, can lead to immune pathology3–5,88–95. It has been suggested that failed X-inactivation can lead to increased expression of TLR7 and TLR8 in individuals with more than one X chromosome93, which could contribute to observed sex differences in susceptibility to certain autoimmune diseases. The sensitivity to overexpression of TLR7 and TLR8 is in contrast to studies of TLR9 overexpression in mice, for which there is no major pathology observed even with two additional copies of a Tlr9 transgene expressed in every cell96.

There is currently no satisfactory explanation for the disparate effects of overexpression of TLR7 and/or TLR8 versus TLR9, but several possibilities merit discussion. The ligands that are recognized by each receptor might have a crucial role — TLR7 and TLR8 can be stimulated by small fragments of RNA, whereas TLR9 requires longer strands of CpG DNA to initiate signalling (Box 3). There could simply be a higher concentration of these simple RNA ligands than of DNA in endosomes. Alternatively, endosomal DNA levels might be tightly controlled by the above-discussed DNases, whereas the sequestration strategies used to reduce endosomal RNA levels are less efficient. It is also possible that there are more diverse intracellular sources of TLR7 and TLR8 ligands, including RNA from endogenous retroviruses and retroelements. Finally, there is the possibility that undiscovered regulatory mechanisms provide additional protection specifically against TLR9-induced autoimmunity.

Cell-type-specific expression and/or specialization of the NA-sensing TLRs also require further consideration. In this Review, we have largely assumed that regulation of the NA-sensing TLRs is similar across cell types, yet there are clear examples of different cell types with distinct patterns of TLR expression and unique modes of regulation (Box 2). These differences are illustrated by the distinct mechanisms of disease associated with dysregulation of TLR7 and TLR8 versus TLR9. In the former case, disease is driven by type I IFN and pDCs, whereas in the latter case, it is driven by IFNγ and natural killer cells2,5,11,19,97,98. How differences in TLR expression (and potentially signalling) lead to such distinct disease manifestations is relatively understudied, and future work will first require the development of tools that enable dissection of TLR signalling and regulation in cell types that are often rare or difficult to isolate.

Finally, a discussion of the expression of NA-sensing TLRs is not complete without noting the presence of marked differences between species. There is substantial variation between mice and humans, particularly with respect to the single-stranded RNA sensors. TLR13 senses bacterial and viral single-stranded RNA in mice but is not encoded in the human genome74,75,99 (Table 1). Instead, human TLR8 seems to have many of the same sensing functions as mouse TLR13 (ref.100). TLR8 itself is also the source of a major difference between mice and humans, in that TLR8 was originally thought to be non-functional in mice owing to its inability to respond to known ligands of human TLR8 (ref.101). Although there have been subsequent reports that mouse TLR8 does respond to certain ligands, its relative role in the hierarchy of single-stranded RNA-sensing TLRs is still an open question. There is also evidence of variation in cell-type-specific expression of the NA-sensing TLRs between mice and humans102. Expression of TLR3 and TLR9 is generally more limited in humans than in mice. For example, TLR9 expression is restricted to pDCs and B cells in humans but it is expressed much more broadly in mice103,104. The evolutionary history of the NA-sensing TLRs is a topic primed for further dissection, and species-specific expression patterns will probably provide further clues to the function and regulation of the NA-sensing TLRs.

Signal transduction

The above regulatory mechanisms, which ensure the proper balance of ligand availability and receptor expression in endosomes, are complemented by mechanisms that regulate signal transduction after activation of the NA-sensing TLRs. Properly modulated signalling functions as an extra layer of protection against inappropriate activation, terminates signalling after activation and ensures the appropriate functional outcome of signalling for different cell types (Box 2). The general molecular players in TLR signalling are not covered in detail here, and we refer the reader to other excellent reviews on that topic1,105. Instead, we focus on the regulatory mechanisms that are imposed selectively on the NA-sensing TLRs, which are not as well understood.

There are relatively few examples of signalling regulation that are specific for the NA-sensing TLRs, although recent studies have identified several key positive regulators. The newly identified protein TASL, encoded by the SLE-associated gene CXorf21 (also known as TASL), interacts with the endolysosomal transporter SLC15A4 to facilitate activation of IRF5, another SLE-associated protein106,107, and the transcription of inflammatory genes in response to stimulation of TLR7, TLR8 and TLR9, but not TLR2 (refs108–110). This work illustrates how genetic variation in positive regulators of NA-sensing TLR signalling can also influence responses to self-nucleic acids, presumably by lowering the threshold for activation that leads to a biologically meaningful transcriptional response. TREML4, another positive regulator of TLR7, TLR9 and TLR13 signalling, promotes MYD88 recruitment to the TLR and STAT1 phosphorylation and activation of transcription111. TREML4 deficiency in mice results in impaired production of IFNβ and the chemokine CXCL10 in response to TLR7 activation but does not affect TLR9-mediated activation of the IFN pathway111. Whereas TASL and TREML4 positively impact the signalling of multiple NA-sensing TLRs, there is one reported example of a signalling regulator that might be specific for TLR9. CD82, a transmembrane protein, positively regulates TLR9 signalling by promoting myddosome assembly112,113. In each of these cases, much more work is needed to understand the precise mechanisms by which these proteins control the signalling of NA-sensing TLRs. Whether these signalling modulators are specific to individual NA-sensing TLRs or whether they are generally involved in signalling pathways originating from the endosome also remains an open question.

UNC93B1, which was discussed above as a chaperone that facilitates transport of the NA-sensing TLRs to the endosome, also regulates signalling by the NA-sensing TLRs. Recent work has shown that UNC93B1 has distinct mechanisms of regulatory control over TLR3, TLR7 and TLR9 (refs24,25). Although UNC93B1 controls the trafficking of all three TLRs, upon reaching the endosome, TLR3 and TLR9 are released from UNC93B1, whereas TLR7 remains associated25. This continued association with UNC93B1 allows for more nuanced control of TLR7 signalling. Upon TLR7 stimulation, UNC93B1 recruits syntenin-1 to the UNC93B1–TLR7 complex, leading to the sorting of the complex into multivesicular bodies and ultimately terminating signalling24. Mutations in UNC93B1 that prevent binding of syntenin-1 induce TLR7 hyperresponsiveness and severe TLR7-dependent autoimmune disease in mice. Notably, a similar mutation in the carboxy-terminal tail of UNC93B1 was recently identified by a genome-wide association study as the causative genetic variant in dogs with a form of cutaneous lupus erythematosus114. Thus, UNC93B1, through its association with syntenin-1, can tune TLR7 signalling and promote signal termination to prevent autoimmunity. Because TLR9 and TLR3 are released from UNC93B1 in the endosome, these receptors are not regulated by this mechanism. Whether distinct UNC93B1-mediated mechanisms restrict activation of these TLRs remains to be determined.

Many additional questions remain regarding UNC93B1-mediated regulation of the NA-sensing TLRs. How does a single protein differentially traffic and regulate multiple NA-sensing TLRs, as well as TLR5, TLR11 and TLR12, which also require UNC93B1 for proper localization? Recent structures of UNC93B1 bound to TLR3 or TLR7 have shown that these TLRs interact with similar regions of UNC93B1; however, the stoichiometry differs between the UNC93B1–TLR3 complex and the UNC93B1–TLR7 complex, indicating the existence of distinct interaction surfaces that may impact TLR function115. Comparisons of additional structures of UNC93B1 bound to each of the TLRs will certainly be an important aspect of future studies focused on defining new regulatory mechanisms. It remains unclear whether UNC93B1 exerts specific regulation of individual NA-sensing TLRs beyond the recently described syntenin-1 pathway. It is also possible that UNC93B1-mediated regulation of NA-sensing TLRs differs across cell types.

Conclusions and future challenges

The NA-sensing TLRs facilitate the recognition of a diverse array of potential pathogens but must be tightly regulated to avoid improper responses to self-nucleic acids. We have discussed four general categories of mechanisms that influence responses by NA-sensing TLRs and establish the balance that enables discrimination between self and foreign nucleic acids. The field has made substantial progress defining these mechanisms over the past decade (Fig. 2), but numerous open questions remain, which we have noted throughout this piece.

There is increasing evidence that each NA-sensing TLR is subject to individualized regulation at multiple levels. Trafficking patterns vary significantly between the NA-sensing TLRs, despite the fact that they all depend on UNC93B1. Modulation of ligand availability is similarly nuanced, with proper regulation of the RNA-sensing TLRs dependent on ligand transporters, whereas the level of TLR9 ligands is regulated by nucleases. These distinct regulatory mechanisms probably determine the contribution of specific TLRs to certain disease states, such as the opposing roles played by TLR7 and TLR9 in experimental models of autoimmunity11–13, yet the logic behind such differences is still poorly understood. Future discoveries will no doubt provide additional pieces to the puzzle and will probably reveal that the regulatory nuances we currently perceive as unnecessarily complex are in fact rooted in functional differences between each of the NA-sensing TLRs. It is also possible that conceptual commonalities will emerge. For example, endosomal transporters for TLR9 and TLR13 ligands, or RNases involved in the removal of potential TLR7 ligands, may be identified.

The extent to which NA-sensing TLR responses are specialized in different immune cell types is also of great interest. We have described one example in which increased signalling of NA-sensing TLRs is wired to facilitate type I IFN production in pDCs, and another in which TLR9 expression and signalling are reduced in tissue-resident macrophages so that they can safely clear apoptotic cells (Box 2). On the basis of these examples, it seems likely that the function of NA-sensing TLRs is also specialized in other immune and non-immune cell types. Some evidence already exists for such specialization in B cells (Box 2). Further progress in this area will require better tools to track receptor expression and function in specific cell types, particularly for cells that are rare and/or difficult to access.

The challenge for the next decade is to unravel the mechanisms that influence each of the four regulatory categories that we have laid out here (compartmentalization, ligand availability, receptor expression and signal transduction) for each NA-sensing TLR. Ideally, these studies will incorporate the recognition of microbial ligands, as differences in the processing and recognition of nucleic acids in the context of microorganisms may be missed with the use of purely synthetic ligands116. The insights gained in the years ahead will undoubtedly reveal new therapeutic approaches for enhancing and inhibiting the activation of these key innate immune receptors (Box 1).

Acknowledgements

Research on nucleic acid sensing by TLRs in the Barton laboratory is supported by funding from the US National Institutes of Health (AI072429). K.P. is a Cancer Research Institute Irvington Fellow supported by the Cancer Research Institute. V.E.R. is supported by the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship Program under grant no. DGE 1752814.

Glossary

- CpG motifs

Short single-stranded oligodeoxynucleotides containing unmethylated CpG motifs function as Toll-like receptor 9 (TLR9) agonists. Different classes of CpG oligodeoxynucleotide are given letter designations (for example, CpG-A, CpG-B and CpG-C) based on the distinct responses they elicit.

- Systemic lupus erythematosus

(SLE). A chronic autoimmune disease characterized by the production of antinuclear autoantibodies and often associated with production of type I interferon. The pathology of SLE can affect joints, skin, brain, lungs, kidneys and blood vessels.

- Psoriasis

A chronic autoimmune disease characterized by inflammation of the skin, leading to raised patches of dry and scaly skin.

- Cytosolic sensors of nucleic acids

Innate immune sensors of infection that detect nucleic acids and reside in the cytosol. Examples include the cGAS–STING pathway and AIM2, which detect DNA, and RIG-I and MDA5, which detect RNA.

- Apoptotic cell microparticles

Small membrane-coated particles released from apoptotic cells that contain genomic DNA and chromatin, as well as RNA.

- cGAS–STING pathway

An innate immune sensing pathway that detects the presence of cytosolic double-stranded DNA and triggers the transcription of type I interferon and other genes involved in the host response.

- Neutrophil extracellular traps

Web-like structures of DNA released into the extracellular space by neutrophils. Neutrophil extracellular traps can trap microorganisms and prevent their dissemination, but in some contexts, they can be a source of self-nucleic acids that drive autoimmune diseases, such as systemic lupus erythematosus and psoriasis.

- Suboptimal codons

Codons that are used at a lower than expected frequency in a given genome. Such codons often result in less efficient translation, which is thought to be owing, at least in part, to the limited availability of corresponding transfer RNAs.

- Myddosome

A multiprotein signalling complex consisting of the adaptor protein MYD88 and members of the IL-1 receptor-associated kinase (IRAK) family that assembles upon activation of all Toll-like receptors (TLRs), except for TLR3.

- Syntenin-1

A PDZ domain-containing adaptor protein that has been implicated in the biogenesis of exosomes and that supports intraluminal budding and delivery of cargo into intraluminal vesicles.

- Multivesicular bodies

Specialized organelles within the endolysosomal network that are characterized by the presence of vesicles within their lumen. These intraluminal vesicles form by budding from the limiting membrane into the lumen. Sorting of cargo into multivesicular bodies is a common mechanism by which receptor signalling is terminated.

Author contributions

All authors researched data for the article, contributed substantially to discussion of the content, wrote the article and reviewed and/or edited the manuscript before submission.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Peer review information

Nature Reviews Immunology thanks K. Fitzgerald, N. J. Gay, A. Weber and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Nicholas A. Lind, Victoria E. Rael, Kathleen Pestal.

References

- 1.Fitzgerald KA, Kagan JC. Toll-like receptors and the control of immunity. Cell. 2020;180:1044–1066. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gavin AL, et al. PLD3 and PLD4 are single-stranded acid exonucleases that regulate endosomal nucleic-acid sensing. Nat. Immunol. 2018;19:942–953. doi: 10.1038/s41590-018-0179-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pisitkun P, et al. Autoreactive B cell responses to RNA-related antigens due to TLR7 gene duplication. Science. 2006;312:1669–1672. doi: 10.1126/science.1124978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Subramanian S, et al. A Tlr7 translocation accelerates systemic autoimmunity in murine lupus. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:9970–9975. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603912103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Deane JA, et al. Control of Toll-like receptor 7 expression is essential to restrict autoimmunity and dendritic cell proliferation. Immunity. 2007;27:801–810. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marshak-Rothstein A. Toll-like receptors in systemic autoimmune disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2006;6:823–835. doi: 10.1038/nri1957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lande R, et al. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells sense self-DNA coupled with antimicrobial peptide. Nature. 2007;449:564–569. doi: 10.1038/nature06116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gilliet M, Lande R. Antimicrobial peptides and self-DNA in autoimmune skin inflammation. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2008;20:401–407. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2008.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kariko K, Buckstein M, Ni H, Weissman D. Suppression of RNA recognition by Toll-like receptors: the impact of nucleoside modification and the evolutionary origin of RNA. Immunity. 2005;23:165–175. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krieg AM, et al. CpG motifs in bacterial DNA trigger direct B-cell activation. Nature. 1995;374:546–549. doi: 10.1038/374546a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Christensen SR, et al. Toll-like receptor 7 and TLR9 dictate autoantibody specificity and have opposing inflammatory and regulatory roles in a murine model of lupus. Immunity. 2006;25:417–428. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nickerson KM, et al. TLR9 regulates TLR7- and MyD88-dependent autoantibody production and disease in a murine model of lupus. J. Immunol. 2010;184:1840–1848. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Santiago-Raber M-L, et al. Critical role of TLR7 in the acceleration of systemic lupus erythematosus in TLR9-deficient mice. J. Autoimmun. 2010;34:339–348. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2009.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Majer O, Liu B, Barton GM. Nucleic acid-sensing TLRs: trafficking and regulation. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2017;44:26–33. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2016.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barton GM, Kagan JC. A cell biological view of Toll-like receptor function: regulation through compartmentalization. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2009;9:535–542. doi: 10.1038/nri2587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leadbetter EA, et al. Chromatin–IgG complexes activate B cells by dual engagement of IgM and Toll-like receptors. Nature. 2002;416:603–607. doi: 10.1038/416603a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barton GM, Kagan JC, Medzhitov R. Intracellular localization of Toll-like receptor 9 prevents recognition of self DNA but facilitates access to viral DNA. Nat. Immunol. 2006;7:49–56. doi: 10.1038/ni1280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mouchess ML, et al. Transmembrane mutations in Toll-like receptor 9 bypass the requirement for ectodomain proteolysis and induce fatal inflammation. Immunity. 2011;35:721–732. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stanbery AG, Newman ZR, Barton GM. Dysregulation of TLR9 in neonates leads to fatal inflammatory disease driven by IFN-γ. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2020;117:3074–3082. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1911579117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim YM, Brinkmann MM, Paquet ME, Ploegh HL. UNC93B1 delivers nucleotide-sensing Toll-like receptors to endolysosomes. Nature. 2008;452:234–238. doi: 10.1038/nature06726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee BL, et al. UNC93B1 mediates differential trafficking of endosomal TLRs. eLife. 2013;2:e00291. doi: 10.7554/eLife.00291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tabeta K, et al. The Unc93b1 mutation 3d disrupts exogenous antigen presentation and signaling via Toll-like receptors 3, 7 and 9. Nat. Immunol. 2006;7:156–164. doi: 10.1038/ni1297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pelka K, et al. The chaperone UNC93B1 regulates Toll-like receptor stability independently of endosomal TLR transport. Immunity. 2018;48:911–922.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2018.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Majer O, Liu B, Kreuk LSM, Krogan N, Barton GM. UNC93B1 recruits syntenin-1 to dampen TLR7 signalling and prevent autoimmunity. Nature. 2019;575:366–370. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1612-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Majer O, et al. Release from UNC93B1 reinforces the compartmentalized activation of select TLRs. Nature. 2019;575:371–374. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1611-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brinkmann MM, et al. The interaction between the ER membrane protein UNC93B and TLR3, 7, and 9 is crucial for TLR signaling. J. Cell Biol. 2007;177:265–275. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200612056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Casrouge A, et al. Herpes simplex virus encephalitis in human UNC-93B deficiency. Science. 2006;314:308–312. doi: 10.1126/science.1128346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fukui R, et al. Unc93B1 biases Toll-like receptor responses to nucleic acid in dendritic cells toward DNA- but against RNA-sensing. J. Exp. Med. 2009;206:1339–1350. doi: 10.1084/jem.20082316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fukui R, et al. Unc93B1 restricts systemic lethal inflammation by orchestrating Toll-like receptor 7 and 9 trafficking. Immunity. 2011;35:69–81. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tsai SY, et al. Regulation of TLR3 activation by S100A9. J. Immunol. 2015;195:4426–4437. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1500378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sasai M, Linehan MM, Iwasaki A. Bifurcation of Toll-like receptor 9 signaling by adaptor protein 3. Science. 2010;329:1530–1534. doi: 10.1126/science.1187029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Blasius AL, et al. Slc15a4, AP-3, and Hermansky–Pudlak syndrome proteins are required for Toll-like receptor signaling in plasmacytoid dendritic cells. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:19973–19978. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1014051107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hayashi K, Sasai M, Iwasaki A. Toll-like receptor 9 trafficking and signaling for type I interferons requires PIKfyve activity. Int. Immunol. 2015;27:435–445. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxv021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Saitoh SI, et al. TLR7 mediated viral recognition results in focal type I interferon secretion by dendritic cells. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:1592. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-01687-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Henault J, et al. Noncanonical autophagy is required for type I interferon secretion in response to DNA–immune complexes. Immunity. 2012;37:986–997. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ewald SE, et al. The ectodomain of Toll-like receptor 9 is cleaved to generate a functional receptor. Nature. 2008;456:658–662. doi: 10.1038/nature07405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Park B, et al. Proteolytic cleavage in an endolysosomal compartment is required for activation of Toll-like receptor 9. Nat. Immunol. 2008;9:1407–1414. doi: 10.1038/ni.1669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sepulveda FE, et al. Critical role for asparagine endopeptidase in endocytic Toll-like receptor signaling in dendritic cells. Immunity. 2009;31:737–748. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ewald SE, et al. Nucleic acid recognition by Toll-like receptors is coupled to stepwise processing by cathepsins and asparagine endopeptidase. J. Exp. Med. 2011;208:643–651. doi: 10.1084/jem.20100682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Garcia-Cattaneo A, et al. Cleavage of Toll-like receptor 3 by cathepsins B and H is essential for signaling. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:9053–9058. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1115091109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ohto U, et al. Structural basis of CpG and inhibitory DNA recognition by Toll-like receptor 9. Nature. 2015;520:702–705. doi: 10.1038/nature14138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hipp MM, et al. Processing of human Toll-like receptor 7 by furin-like proprotein convertases is required for its accumulation and activity in endosomes. Immunity. 2013;39:711–721. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ishii N, Funami K, Tatematsu M, Seya T, Matsumoto M. Endosomal localization of TLR8 confers distinctive proteolytic processing on human myeloid cells. J. Immunol. 2014;193:5118–5128. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1401375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sisirak V, et al. Digestion of chromatin in apoptotic cell microparticles prevents autoimmunity. Cell. 2016;166:88–101. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.05.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Al-Mayouf SM, et al. Loss-of-function variant in DNASE1L3 causes a familial form of systemic lupus erythematosus. Nat. Genet. 2011;43:1186–1188. doi: 10.1038/ng.975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Soni C, et al. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells and type I interferon promote extrafollicular B cell responses to extracellular self-DNA. Immunity. 2020;52:1022–1038.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2020.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Davenne T, Bridgeman A, Rigby RE, Rehwinkel J. Deoxyguanosine is a TLR7 agonist. Eur. J. Immunol. 2020;50:56–62. doi: 10.1002/eji.201948151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Desnues B, et al. TLR8 on dendritic cells and TLR9 on B cells restrain TLR7-mediated spontaneous autoimmunity in C57BL/6 mice. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2014;111:1497–1502. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1314121111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yoshida H, Okabe Y, Kawane K, Fukuyama H, Nagata S. Lethal anemia caused by interferon-β produced in mouse embryos carrying undigested DNA. Nat. Immunol. 2005;6:49–56. doi: 10.1038/ni1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kawane K, et al. Chronic polyarthritis caused by mammalian DNA that escapes from degradation in macrophages. Nature. 2006;443:998–1002. doi: 10.1038/nature05245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ahn J, Gutman D, Saijo S, Barber GN. STING manifests self DNA-dependent inflammatory disease. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:19386–19391. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1215006109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Baum R, et al. Cutting edge: AIM2 and endosomal TLRs differentially regulate arthritis and autoantibody production in DNase II-deficient mice. J. Immunol. 2015;194:873–877. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1402573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pawaria S, et al. An unexpected role for RNA-sensing Toll-like receptors in a murine model of DNA accrual. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 2015;33:S70–S73. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pawaria S, et al. Cutting edge: DNase II deficiency prevents activation of autoreactive B cells by double-stranded DNA endogenous ligands. J. Immunol. 2015;194:1403–1407. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1402893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Napirei M, et al. Features of systemic lupus erythematosus in Dnase1-deficient mice. Nat. Genet. 2000;25:177–181. doi: 10.1038/76032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yasutomo K, et al. Mutation of DNASE1 in people with systemic lupus erythematosus. Nat. Genet. 2001;28:313–314. doi: 10.1038/91070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sun X, et al. Increased ribonuclease expression reduces inflammation and prolongs survival in TLR7 transgenic mice. J. Immunol. 2013;190:2536–2543. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1202689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Garnett ER, et al. Phenotype of ribonuclease 1 deficiency in mice. RNA. 2019;25:921–934. doi: 10.1261/rna.070433.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lee HH, Wang YN, Hung MC. Functional roles of the human ribonuclease A superfamily in RNA metabolism and membrane receptor biology. Mol. Aspects Med. 2019;70:106–116. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2019.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lau CM, et al. RNA-associated autoantigens activate B cells by combined B cell antigen receptor/Toll-like receptor 7 engagement. J. Exp. Med. 2005;202:1171–1177. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yasuda K, et al. Murine dendritic cell type I IFN production induced by human IgG–RNA immune complexes is IFN regulatory factor (IRF)5 and IRF7 dependent and is required for IL-6 production. J. Immunol. 2007;178:6876–6885. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.11.6876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yasuda K, et al. Requirement for DNA CpG content in TLR9-dependent dendritic cell activation induced by DNA-containing immune complexes. J. Immunol. 2009;183:3109–3117. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bertheloot D, et al. RAGE enhances TLR responses through binding and internalization of RNA. J. Immunol. 2016;197:4118–4126. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1502169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tian J, et al. Toll-like receptor 9-dependent activation by DNA-containing immune complexes is mediated by HMGB1 and RAGE. Nat. Immunol. 2007;8:487–496. doi: 10.1038/ni1457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sirois CM, et al. RAGE is a nucleic acid receptor that promotes inflammatory responses to DNA. J. Exp. Med. 2013;210:2447–2463. doi: 10.1084/jem.20120201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ganguly D, et al. Self-RNA–antimicrobial peptide complexes activate human dendritic cells through TLR7 and TLR8. J. Exp. Med. 2009;206:1983–1994. doi: 10.1084/jem.20090480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lande R, et al. Neutrophils activate plasmacytoid dendritic cells by releasing self-DNA–peptide complexes in systemic lupus erythematosus. Sci. Transl. Med. 2011;3:73ra19. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3001180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gestermann N, et al. Netting neutrophils activate autoreactive B cells in lupus. J. Immunol. 2018;200:3364–3371. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1700778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Herster F, et al. Neutrophil extracellular trap-associated RNA and LL37 enable self-amplifying inflammation in psoriasis. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:105. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-13756-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ivanov S, et al. A novel role for HMGB1 in TLR9-mediated inflammatory responses to CpG-DNA. Blood. 2007;110:1970–1981. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-09-044776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Greulich W, et al. TLR8 is a sensor of RNase T2 degradation products. Cell. 2019;179:1264–1275.e13. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2019.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ostendorf T, et al. Immune sensing of synthetic, bacterial, and protozoan RNA by Toll-like receptor 8 requires coordinated processing by RNase T2 and RNase 2. Immunity. 2020;52:591–605.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2020.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Chan MP, et al. DNase II-dependent DNA digestion is required for DNA sensing by TLR9. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:5853. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Li XD, Chen ZJ. Sequence specific detection of bacterial 23 S ribosomal RNA by TLR13. eLife. 2012;1:e00102. doi: 10.7554/eLife.00102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Oldenburg M, et al. TLR13 recognizes bacterial 23 S rRNA devoid of erythromycin resistance-forming modification. Science. 2012;337:1111–1115. doi: 10.1126/science.1220363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Shibata T, et al. Guanosine and its modified derivatives are endogenous ligands for TLR7. Int. Immunol. 2016;28:211–222. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxv062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Tanji H, et al. Toll-like receptor 8 senses degradation products of single-stranded RNA. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2015;22:109–115. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Zhang Z, et al. Structural analysis reveals that Toll-like receptor 7 is a dual receptor for guanosine and single-stranded RNA. Immunity. 2016;45:737–748. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Shibata T, et al. Nucleosides drive histiocytosis in SLC29A3 disorders by activating TLR7. bioRxiv. 2019 doi: 10.1101/2019.12.16.877357. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Nair S, et al. Adult stem cell deficits drive Slc29a3 disorders in mice. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:2943. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-10925-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Molho-Pessach V, et al. The H syndrome is caused by mutations in the nucleoside transporter hENT3. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2008;83:529–534. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Cliffe ST, et al. SLC29A3 gene is mutated in pigmented hypertrichosis with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus syndrome and interacts with the insulin signaling pathway. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2009;18:2257–2265. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Morgan NV, et al. Mutations in SLC29A3, encoding an equilibrative nucleoside transporter ENT3, cause a familial histiocytosis syndrome (Faisalabad histiocytosis) and familial Rosai–Dorfman disease. PLoS Genet. 2010;6:e1000833. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Nguyen TA, et al. SIDT2 transports extracellular dsRNA into the cytoplasm for innate immune recognition. Immunity. 2017;47:498–509.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2017.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Nguyen TA, et al. SIDT1 localizes to endolysosomes and mediates double-stranded RNA transport into the cytoplasm. J. Immunol. 2019;202:3483–3492. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1801369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Zhong F, et al. Deviation from major codons in the Toll-like receptor genes is associated with low Toll-like receptor expression. Immunology. 2005;114:83–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2004.02007.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Newman ZR, Young JM, Ingolia NT, Barton GM. Differences in codon bias and GC content contribute to the balanced expression of TLR7 and TLR9. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2016;113:E1362–E1371. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1518976113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Guiducci C, et al. RNA recognition by human TLR8 can lead to autoimmune inflammation. J. Exp. Med. 2013;210:2903–2919. doi: 10.1084/jem.20131044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Buechler MB, Akilesh HM, Hamerman JA. Cutting edge: direct sensing of TLR7 ligands and type I IFN by the common myeloid progenitor promotes mTOR/PI3K-dependent emergency myelopoiesis. J. Immunol. 2016;197:2577–2582. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1600813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Akilesh HM, et al. Chronic TLR7 and TLR9 signaling drives anemia via differentiation of specialized hemophagocytes. Science. 2019;363:eaao5213. doi: 10.1126/science.aao5213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Garcia-Ortiz H, et al. Association of TLR7 copy number variation with susceptibility to childhood-onset systemic lupus erythematosus in Mexican population. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2010;69:1861–1865. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.124313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Martin GV, et al. Mosaicism of XX and XXY cells accounts for high copy number of Toll like receptor 7 and 8 genes in peripheral blood of men with rheumatoid arthritis. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:12880. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-49309-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Souyris M, et al. TLR7 escapes X chromosome inactivation in immune cells. Sci. Immunol. 2018;3:eaap8855. doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.aap8855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Scofield RH, et al. Klinefelter’s syndrome (47,XXY) in male systemic lupus erythematosus patients: support for the notion of a gene-dose effect from the X chromosome. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:2511–2517. doi: 10.1002/art.23701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Liu K, et al. X chromosome dose and sex bias in autoimmune diseases: increased prevalence of 47,XXX in systemic lupus erythematosus and Sjogren’s syndrome. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68:1290–1300. doi: 10.1002/art.39560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Roberts AW, et al. Tissue-resident macrophages are locally programmed for silent clearance of apoptotic cells. Immunity. 2017;47:913–927.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2017.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Behrens EM, et al. Repeated TLR9 stimulation results in macrophage activation syndrome-like disease in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 2011;121:2264–2277. doi: 10.1172/JCI43157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Rowland SL, et al. Early, transient depletion of plasmacytoid dendritic cells ameliorates autoimmunity in a lupus model. J. Exp. Med. 2014;211:1977–1991. doi: 10.1084/jem.20132620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Shi Z, et al. A novel Toll-like receptor that recognizes vesicular stomatitis virus. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:4517–4524. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.159590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]