Abstract

Introduction:

Qualitative analysis of Twitter posts reveals key insights about user norms, informedness, perceptions, and experiences related to opioid use disorder (OUD). This paper characterizes Twitter message content pertaining to medications for opioid use disorder (MOUD) and Naloxone.

Methods:

In-depth thematic analysis was conducted of 1,010 Twitter messages collected in June 2019. Our primary aim was to identify user perceptions and experiences related to harm reduction (e.g., Naloxone) and MOUD (e.g., sublingual and Extended-release buprenorphine, Extended-release naltrexone, Methadone).

Results:

Tweets relating to OUD were most commonly authored by general Twitter users (43.8%), private residential or detoxification programs (24.6%), healthcare providers (e.g., physicians, first responders; 4.3%), PWUOs (4.7%) and their caregivers (2.9%). Naloxone was mentioned in 23.8% of posts and authored most commonly by general users (52.9%), public health experts (7.4%), and nonprofit/advocacy organizations (6.6%). Sentiment was mostly positive about Naloxone (73.6%). Commonly mentioned MOUDs in our search consisted of Buprenorphine-naloxone (13.8%), Methadone (5.7%), Extended-release naltrexone (4.1%), and Extended-release buprenorphine (0.01%). Tweets authored by PWUOs (4.7%) most commonly related to factors influencing access to MOUD or adverse events related to MOUD (70.8%), negative or positive experiences with illicit substance use (25%), policies related to expanding access to treatments for OUD (8.3%), and stigma experienced by healthcare providers (8.3%).

Conclusion:

Twitter is utilized by a diverse array of individuals, including PWUOs, and offers an innovative approach to evaluate experiences and themes related to illicit opioid use, MOUD, and harm reduction.

Keywords: Opioid use disorder, social media, twitter, medications for opioid use disorder, naloxone, buprenorphine-naloxone, extended-release naltrexone

Introduction

Nearly all Americans regularly use the Internet (90%), and the majority are connected to social media (72%).1,2 As a result, social media has become an important tool by which health researchers can study perceptions and patterns of health information sharing across multiple communities. Social media research is an especially important way to reach special interest groups that may be less represented in traditional health research including young adults (18–29 years old, 90%), Hispanic/Latinos (70%), African-Americans (68%), and women (70%).2 Twitter, which is used by approximately 22% of US adults and attracts a broad array of conversations related to health, has become a useful tool to assess current events and experiences related to a range of health topics.3 Twitter is especially popular because it is essentially a micro-blogging platform and user posts on it are typically publicly available.

Over recent years, health researchers have utilized Twitter to study substance use disorders, including alcohol, tobacco, cannabis, psychostimulants, and opioids. Given the high stigma associated with substance use, social media allows many users and their networks to openly share information with reduced concern for judgment and retaliation. Opioid use disorder (OUD), which affects over two million Americans and is the primary driver of ongoing overdose deaths across the U.S., is of particularly high interest to health researchers, especially given incessant gaps in access to effective treatment and services to reduce opioid-related harms.4

Preliminary research pertaining to OUD on Twitter have yielded some important findings: Mackey and colleagues reported that Twitter can be used to facilitate illicit sales of prescription opioids.5 Sarker et al., utilized supervised classification and natural language processing for monitoring and classifying posts with prescription opioid misuse content.6 Natural language processing has also been harnessed to identify prescription opioid misuse (i.e., Oxycontin®) on Twitter and assess the location of prescription opioid misuse tweets relative to state-level OUD prevalence estimates from nationally representative data.7 Finally, Tofighi et al. identified how peer-to-peer exchanges on Twitter may facilitate: 1) access to heroin and prescription opioids; 2) sharing opioid withdrawal experiences; and 3) exchanges of emotional support and recovery resources among family and friends of people who use opioids (PWUO).

Despite the promise of Twitter as a scalable resource for OUD-related information from a large population, there is a paucity of studies that have investigated the perceptions, experiences, and information posted about medications for opioid use disorder (MOUD) and harm reduction (e.g., Naloxone) to reduce overdose and other health harms. Two effective approaches to reducing opioid overdose fatalities include improving access to Naloxone, which effectively reverses opioid overdose, and improving entry and retention on MOUD, including Methadone, Buprenorphine-naloxone, and Extended release naltrexone.8,9 Prior work suggests the limited frequency of credible posts by clinicians and public health experts relating to OUD relative to marketing and stigmatizing content related to PWUOs.10 Still, more is needed to understand the nature of the content that is being circulated related to these services as well as the different driving sources of this content.

In light of ongoing opioid overdose fatalities and underutilization of effective harm reduction and treatment strategies for PWUOs, this study sought to assess perceptions and experiences relating to Naloxone and MOUDs (e.g., Methadone, Buprenorphine-naloxone, Extended-release naltrexone, and Extended-release buprenorphine) and how these vary based on user type (e.g., PWUOs, family/friends of PWUO, and healthcare providers).9 These findings may inform public health interventions that leverage social media platforms to rapidly increase access to evidence-based harm reduction and treatment resources for hard-to-reach populations with OUD whom experience disparities in OUD outcomes.

Methods

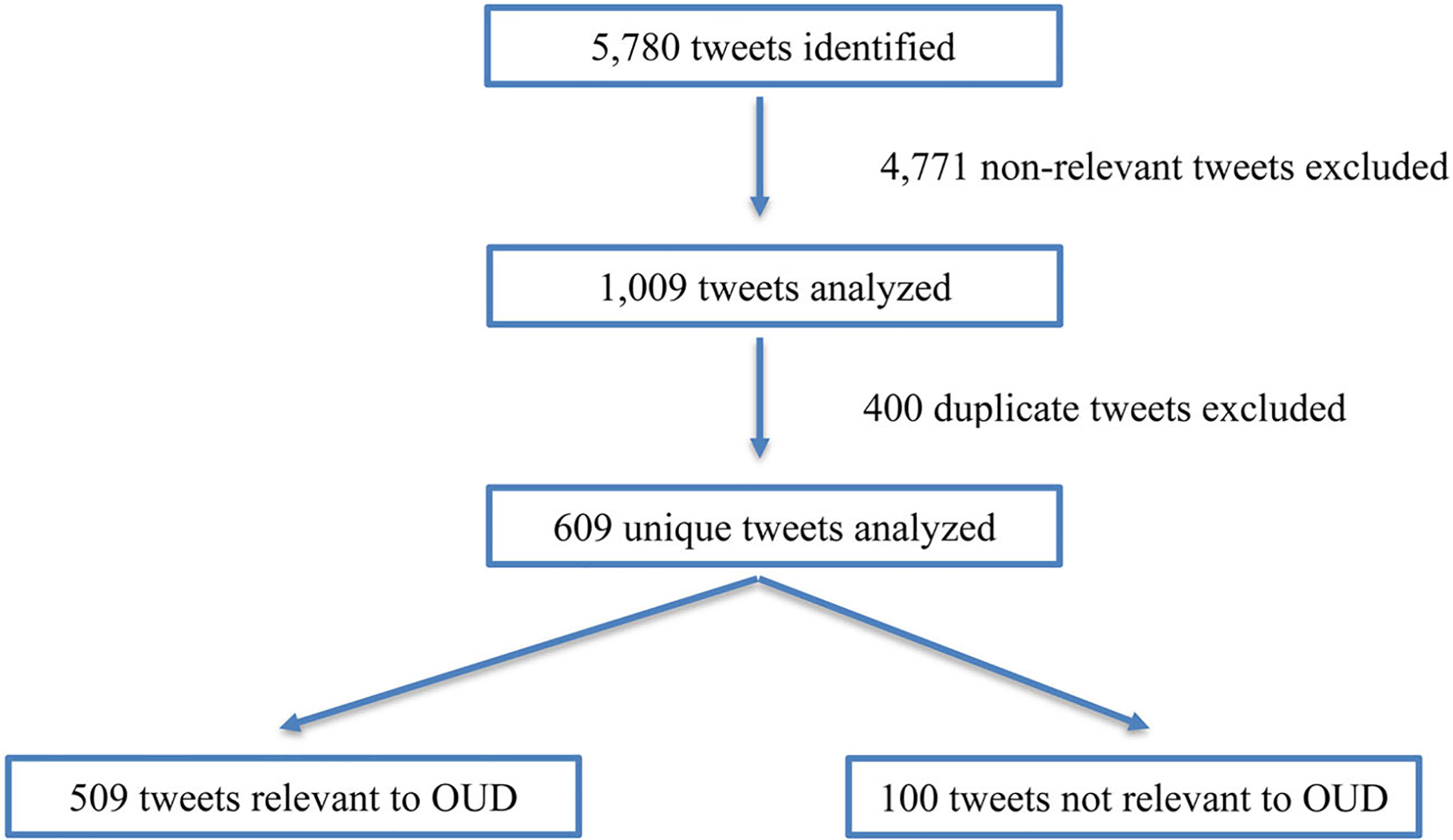

Data collection relied on the Twitter Application Programing Interface (API), which enables the collection of a sample of public posts on Twitter using keywords. The study team used an open source Python module, langdetect, to acquire tweets and retweets that were not geolocated. Posts archived between May 26 and June 6, 2019 were collected in August 2019. Tweets (n = 5,780) mentioning opioids were collected using opioid keywords (i.e., opioids, heroin, opiates, dope, oxy*, oxycontin, pills, percocet) and relevant medications for OUD (i.e., narcan, naloxone, bup*, suboxone, zubsolv, sublocade, vivitrol, naltrexone, Methadone). These keywords were based on prior studies evaluating Twitter and technology use patterns among PWUO and modified after a preliminary review of our Twitter sample.5,7,10 Non-relevant tweets (n = 4,771) were manually excluded if they were non-English language posts, “retweets” that lacked any additional content, tweets that were related to a thread and necessitated further contextualization to be fully understood, consisted of links or hashtags not related to OUD, MOUD, or Naloxone. The study team then manually analyzed 1,009 posts and removed tweets that were duplicates (n = 400), metaphors or sarcastic comments not related to OUD (n = 69), pertaining to alcohol use disorder only (n = 29), or referring to cannabis use only (n = 2) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of search and exclusion of tweets.

The coding schema was derived manually by content experts in OUD (BT, OE, AS) and a trained medical student (AS) using a subset of Tweets based on the grounded theory approach. The lead author, who is an expert in OUD (BT) identified the structured coding categories and reviewed the schema with the two other coders (OE, AS) on the scope of each category. The study team conducted three meetings to iteratively refine the coding schemes after a review of 210 randomly selected tweets (n = 70/meeting). Each tweet was then independently coded into its respective categories by one of the coders (AS, OE, BT) using a structured coding excel workbook. The coding categories focused on differentiating the author of the post, intended audience, overall themes, and issues or experiences related to MOUD. The coding categories were not mutually exclusive, that is each tweet could reflect more than one of the following categories: 1) source (PWUOs, family/friends of PWUOs, healthcare providers, addiction treatment program); 2) intended audience per post @replies, hashtags, and Tweet content; 3) sentiment (positive, negative, neutral); 4) genre (i.e., personal experience, joke/sarcasm, news, policy, education, recovery services, emotional or concrete support for recovery, encouraging illicit opioid use); and 5) theme relating to the content conveyed by authors (e.g., overdose, MOUD, illicit opioid use, PWUOs). Additional attention was given to user claims requiring evidence (i.e., medical research, news). The source of the tweet was categorized as a PWUO if they presented content meeting criteria for OUD as outlined by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders, elicited an overdose episode, opioid use for non-medical purposes, or OUD treatment experience, or requested access to illicit opioids or resources to address their OUD.11 The interrater agreement of the coded variables was assessed via a random sample of n = 150 tweets (29.5%) coded independently by the three coders. Mean Cohen’s κ for Tweet coding categories was 0.95 (range 0.81–1.00).12,13

Results

Content analysis of twitter author categories

Tweets related to OUD were most often authored by general Twitter users (43.8%), private residential or detoxification programs (24.6%), healthcare providers (e.g., physicians, first responders; 4.3%), PWUOs (4.7%) and their caregivers (2.9%). Other authors included politicians (n = 3), blog writers (n = 3), law enforcement (n = 2), magazines related to OUD (n = 2), pharmaceutical company (n = 1), and a foundation (n = 1; see Table 1). The study team was unable to categorize authors for 3.3% of posts (n = 17) due to the limited information available in the tweet or the profile associated with the tweet (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Author categories for tweets related to OUD.

| User type definition | Users (n = 509) % (n) | Tweet examples |

|---|---|---|

| General | 43.8 (223) | Most of the time it doesn’t start with heroin. It’s trying someone’s moms norco or percocets at a party and THAT leads to heroin. Please let’s educate and take care of each other. 5 people have OD’d at the bus stop outside my apt in the last 8 months. I carry Narcan in my purse. [link] |

| Private residential and/or inpatient detoxification programs | 24.6 (125) | Are you or someone you know suffering from a prescription drug or heroin problem? Help is available. Call ###-###-#### for treatment resources. |

| PWUO | 4.7 (24) | @username I feel like this too. I think it’s gotten worse in my late 20’s for sure. I’d like to think it’s clinical depression or some lingering affect of heroin addiction/recent sobriety. Ketamine treatment legitimately worked but the physician in my town stopped taking my insurance. |

| Healthcare Provider | 4.3 (22) | @username Why? It’s not 2002–2004 anymore. 2004 in NY you were paying $1500+ just to SEE the doctor to get on Suboxone. I have the easiest time getting clients on Suboxone/Subutex in CA, Vivitrol is another story. |

| News | 3.1 (16) | ‘I’m trying not to die right now’: Why opioid-addicted patients are still searching for help [link] |

| Caregivers of PWUO | 2.9 (15) | @username I appreciate his tolerance levels will have dropped but I can’t understand why his treatment would have to be cut for a month - how does this help the situation? he was telling me how proud he was he had been off heroin for a week before all this happened |

| Nonprofit/Advocacy | 2.9 (15) | Interested in accessing resources during PRIDE? Here is a map of the safer sex spots we have set up along the route! Want more info on naloxone and treatment services? Give the Revive. Survive. OverDose Prevention Team a call at ###-###-#### # iprevent #pride #safersex #naloxone [link] |

| Podcast | 2.6 (13) | Are you talking with Colin Morrison [link] ###-###-#### #sober #treatement #intervention #addiction #dependency #detox #relapse #Malibu #recovery #wsj #nytimes #reuters #forbes #nasdaq #chicago #newyork #business #cnn #bet #foxnews #CBD #MAGA #sports [link] |

| Public Health Expert | 2.4 (12) | OD ALERT: Saint Paul has had five suspected heroin overdoses in the last 36 hours. If you suspect an overdose: Read more [link]

|

| Chronic pain patient | 2.2 (11) | @username Yeah, I have a benzo, but also am on opioids for chronic pain, and my doctor is quite concerned about the two. He makes me carry Narcan with me due to the potential for overdose even at prescribed doses. So it’s an option! And I use it when it’s bad. |

| Website/Blog | 1.0 (5) | Hello @username, are you looking for #Alcohol & #Drug #Addiction #Rehab #Treatment #Tips Alcohol and drug addiction represent a growing #public #health crisis. This blog can give you the help you need to #detox, rehab, and get freedom from addiction. [link] |

Private residential and inpatient detoxification programs (24.6%, n = 125) infrequently cited MOUD as a part of their treatment protocols (6.4%, n = 8/125) and some programs encouraged “detoxification” off of Methadone or Buprenorphine-naloxone (4%, n = 5/125). Treatment programs sought to garner legitimacy by posting “proven home detox kits,” links to popular press coverage about their program, hashtags of popular press despite no articles from these sources about the programs (e.g., “#reuters #foxnews), updating readers with podcast interviews and magazine articles about the program’s CEO that was actually published by the program’s own website, and quoting celebrities’ positive treatment experiences after entering their program.

Tweets authored by PWUOs (4.7%) related to: 1) treatment (70.8%, 17/24), including barriers to accessing MOUD due to cost or lack of providers prescribing MOUD, motivations for seeking MOUD treatment versus inpatient detoxification treatment and an abstinence based approach, positive and negative experiences utilizing addiction treatment services (e.g., withdrawal symptoms persistent cravings), perceptions regarding MOUD, challenges with self-tapering off of Methadone or Buprenorphine-naloxone, experiences with worsening withdrawal symptoms following admission to inpatient detoxification treatment, and adverse events related to MOUD; 2) negative or positive active use (25%, 6/24) experiences with heroin, prescription opioids, or poly-substance use; 3) politics/policy (8.3%, 2/24) related to expanding access to MOUD or inpatient detoxification treatment; 4) stigma experienced by healthcare providers; and/or 5) surviving an overdose event (4.2%, 1/24). Posts by family or friends of PWUO often recounted harrowing experiences with acquaintances diagnosed with OUD or passing away from an opioid overdose, and the importance of increasing access to MOUD and Naloxone (2.9%).

Healthcare providers (e.g., physicians, nurses; 4.3%) emphasized the importance of expanding access to MOUD and Naloxone citing personal experiences, peer-reviewed literature, or state and federal guidelines. Providers also highlighted barriers to accessing MOUD and Naloxone, including limited information among providers and patients, out-of-pocket costs, need for contact information to allow patients to enter programs offering MOUD, and addressing stigma related to MOUD. Although general users frequently tweeted about findings disseminated in peer-reviewed manuscripts (e.g., barriers to OUD treatment, effectiveness of MOUD), public health experts infrequently posted informational, treatment, or policy content pertaining to opioids, OUD, and treatments for OUD (2.4%).

Claims shared by all users were primarily based on personal experiences (33.8%), information posted by a private detoxification and/or residential treatment program (27.5%), a public health expert (e.g., departments of health, academic or peer-reviewed research; 15.1%), and news (e.g., television, newspaper; 10.8%).

Content analysis of twitter post categories

Tweets were coded into non-mutually exclusive categories (see Table 2). The most common content categories related to OUD posted in our sample referred to treatment (70.7%), policy or political comments (27.7%), and harm reduction (24.8%).

Table 2.

Categories of tweets related to OUD identified via content analysis (n = 509).

| Category | Example | Post frequency related to OUD, %1 (n) |

|---|---|---|

| Treatment | Anyone know if PCP in CA can write for Methadone? If no, who has the authority? Some counties are Suboxone only. PCP trying 2 help by sending me 2 MAT afraid of health consequences w/ Methadone detox after 20 years. #notanaddict just need my Methadone Does MAT take #CPP? | 70.7 (360) |

| Politics/Policy | Pathetic time-wasting “efforts” of @username inventing an “ecig” epidemic while ignoring #opioids during his tenure - almost kills 2-year-old. [link] | 27.7 (141) |

| Harm Reduction | #Narcan (naloxone) is designated as an opiate antidote, meaning it can reverse the effects of opioids after someone has taken them. @username is a nonprofit group formed to facilitate prevention efforts in Shelby County to combat substance abuse and its consequences. | 24.8 (126) |

| Active Use | @username It is the catalyst for many users. Starts with pain / injury and becomes addictive. Nearly 80 percent of Americans using heroin (including those in treatment) reported misusing prescription opioids prior to using heroin. | 17.7 (90) |

| Overdose News | wish Canada would get a grip on the addiction crisis..my son is in dire need..he’s been calling detox for 3 weeks … no beds..in the meantime he’s overdosed 2x..#heartbroken Paramedics revive Beechview girl, 11, who overdosed on heroin [link] | 13.8 (70) 11.0 (56) |

| Peer Support | @username And this is NOT to downplay/dismiss the ‘addiction’. We KNOW it can be so so strong. It is however, encouragement to adjust your focus onto yourself. Once your reasons/motives/drives are uncovered, they can be tackled. Hugs. Detox is painful, but important. | 2.7 (36) |

| Pain Management | @username The narrative for persons having legitimate, Physician-treated chronic pain-management issues requiring opioids is a valid one. Unfortunately, CNS depressants/opioids have hundreds of narratives; many which don’t involve a physician but involve Narcan, some involving OD deaths. | 5.9 (30) |

| PWUO | @username We have no idea the duration or depth of her addiction- each withdrawl is different in time & degree dep on abuse. When she was in the hosp she started detox, had taken pills only after fight with username. Keeping a calendar on her sobriety wont match unless your with her 24/7. | 5.1 (26) |

| Education | We just finished a dynamic #webinar with local health departments in #newyork on using #academicdetailing to improve access to #suboxone for treatment of #opioidusedisorder! #publichealth #OpioidCrisis #opioidepidemic #buprenorphine #mat #behaviorchange #stigma [link] | 2.2 (11) |

| Jokes/Sarcasm | Well you gave free condoms for the AIDS crisis, how about some free Narcan and Fentanyl test strips for the addicts that illegally abuse opioids. Come On Now !! #fakeopioidcrisis #opioidcrisis #personalresponsibility | 1.2 (6) |

| Stigma | Does It Really Matter How We Talk About Addiction? Words can hurt when they reinforce misconceptions. Read more: #detox #healthylifestyle #wellness #rehab #drug #addiction #alcohol #therapist #abuse #program #recovery [link] |

>1.0 (4) |

| News | *Cops Saves Overdose Victim *A #RedHook police officer saved a man overdosing on opioids by administering Narcan. #DailyVoice #Dutchess [link] | >1.0 (3) |

Content frequency may be greater than 100% because categories are not mutually exclusive.

Naloxone was mentioned in 23.8% of posts and authored most commonly by general users (n = 65, 52.9%), public health experts (n = 9, 7.4%), nonprofit/advocacy organizations (n = 8, 6.6%), and news (n = 8, 6.6%). Sentiment was mostly positive about Naloxone (73.6%). Negative posts about Naloxone (n = 19, 15.7%) were associated with stigmatizing comments about PWUOs who would be “enabled” to use more illicit opioids due to Naloxone, claims that Naloxone does not reduce overdose, and criticisms of government policies misallocating resources for PWUOs rather than more “legitimate” health needs such as opioid analgesics for chronic pain patients or needles for diabetic patients.

Commonly mentioned MOUDs in our search consisted of Buprenorphine-naloxone (13.8%), Methadone (5.7%), Extended-release naltrexone (4.1%), and extended-release buprenorphine (0.01%). Users frequently posted the importance of expanding access to MOUD [e.g., general users (n = 40), family or friends of PWUO (n = 4), PWUO (n = 2), healthcare providers (n = 2), and public health experts (n = 1)].

Buprenorphine-naloxone (13.8%) was most commonly posted by general users (n = 34, 48.6%), addiction treatment programs (n = 8, 11.4%), and healthcare providers (n = 8, 11.4%). Approximately half of posts pertaining to Buprenorphine-naloxone were positive (n = 35, 50%). Negative comments pertaining to the medication (n = 23, 32.9%), were generated by general users (n = 11), addiction treatment programs (n = 7) and PWUOs (n = 4) emphasizing an abstinence-based approach to treatment requiring “faith” and “willpower.” Additional posts critical of Buprenorphine-naloxone targeted policies expanding access to MOUD for PWUOs while chronic pain patients were unfairly discontinued off of opioid analgesics. Several posts that were supportive of Buprenorphine treatment highlighted ongoing barriers to accessing such treatment and attributed to increased medication costs, limited access to prescribers, residential treatment or inpatient detoxification programs not inducting patients to buprenorphine, stigma attributed to opioid antagonist therapies by the general public and criminal justice system, and rigid clinic protocols terminating care for patients suspected of illicit substance use.

Posts regarding Methadone (5.7%) were mostly authored by general users (n = 10, 34.5%) and PWUOs (n = 8, 27.6%). Positive sentiment relating to Methadone (n = 14, 48.3%) included its beneficial treatment outcomes shared by some PWUOs and healthcare providers, and importance of offering office-based treatment with Methadone. Negative perceptions of Methadone (n = 11, 37.9%) highlighted challenges in tapering off of Methadone compared to heroin or Buprenorphine-naloxone, the benefits of antagonist treatment with Extended-release naltrexone versus “trading one addiction for another” in the form of Methadone, and risks of overdose with illicit Methadone use shared by two PWUOs. Several detoxification programs encouraged readers to utilize their services to “detox” off of Methadone.

Fewer posts cited Extended-release naltrexone (4.1%) and were authored by general users (n = 7, 33.3%), addiction treatment programs (n = 6, 28.6%), and healthcare providers (n = 3, 14.3%). Sentiment regarding Extended-release naltrexone was mostly positive (n = 14, 66.7%) and described as a “godsend,” with one user claiming that “its probably more effective than Methadone and suboxone.” One Twitter user self-reported the benefits of the treatment for their recovery openly: “I took Vivitrol for 3 months after I left treatment. I know it was a huge factor in maintaining my sobriety especially in the beginning. I try to tell everyone about it.” Posts critical of Extended-release naltrexone centered on its mandated use in criminal justice settings versus expanding access to opioid agonist therapies (n = 2), and higher cost (n = 1): “We need our courts to stop pushing Vivitrol and abstinence, and to stop violating people for #Methadone and #suboxone.” Some Twitter users also shared adverse experienced related to the injection, including nausea, gluteal pain, and swelling (n = 3).

All four posts mentioning Buprenorphine extended-release were positive and authored by a general user, physician, PWUO, and an addiction treatment program. Additional posts mentioned heroin-assisted treatment (n = 9), all of which were posted by general users and were positive. Seven posts pertaining to cannabis or cannabidiol products were published with positive sentiment and published by general users (n = 6, 85.7%). Additional posts recommended “home detox kits” that lacked information on active ingredients (n = 6), Ibogaine (n = 4), “natural remedies” (n = 2), and ketamine (n = 1) to support detoxification from illicit opioids, Buprenorphine-nalox-one, and/or Methadone without any references to support such claims.

Discussion

The current study demonstrates the feasibility of leveraging Twitter to identify informational content, experiences, and perceptions related to illicit opioid use, opioid overdose, and treatments for OUD. This work adds to a growing body of research about the unique opportunity that social media research provides to explore health topics that are sensitive or stigmatized across multiple sectors of society.5,6,7,10

Analysis of posts reveals new understandings of sentiment and informedness relating to OUD and the types of sources through which this information is being shared. Importantly, there was a paucity of Tweets authored by public health experts, healthcare providers, and nonprofit/advocacy organizations pertaining to Naloxone and MOUD. Most posts relating to Naloxone and MOUD were authored by general users and private treatment programs that shared opinions or advertisements rather than any evidence-based content. Negative sentiment targeting Naloxone, MOUD, and PWUOs were less frequent but highlighted a concerning proportion of posts authored primarily by general users and private treatment programs that mislead readers and stigmatized PWUOs and MOUD. Lastly, posts informing readers about emerging pharmacotherapies for OUD, including Extended-release naltrexone (4.1%) and Buprenorphine extended-release (0.01%) were uncommon.

Twitter content revealed multiple ways by which PWUOs and caregivers use the platform to reveal circumstances related to stigma, illicit opioid use, overdose events, and experiences and perceptions regarding accessing MOUD. One strategy to enhance the availability of evidence-based content among PWUOs and their caregivers is to identify novel strategies that enhance the reach of “peer experts” with lived experiences relating to MOUD and Naloxone in social media.14 A concerning finding was the frequent use of Twitter by commercial treatment programs to promote remedies (e.g., “home detox kits”) and services (e.g., rapid detoxification, residential treatment) that were not verifiable or evidence based. In some instances, commercial vendors and inpatient treatment programs disparaged MOUD and encouraged PWUOs to procure their services (e.g., Ibogaine, various formulations of Cannabidiols, “herbal remedies” consisting of unknown active ingredients, and creams). Although Twitter is uniquely positioned to counter misleading claims or negative sentiment pertaining to MOUD and harm reduction, few public health experts, harm reduction programs, and healthcare providers were actively identified in our search, and therefore likely make up a minority of active users commenting on these topics.

These findings therefore call for an urgent need for public health agencies to fully harness social media platforms to scale-up information and access to evidence-based content, harm reduction, and treatment resources. Expanding reach of valuable information to hard-to-reach populations with OUD whom commonly utilize Twitter has the potential to reduce disparities in OUD outcomes with minimal burden on caregivers, health systems, and state agencies1. Distinct opportunities for public health interventions include: 1) leveraging advances in natural language processing to offer “just-in-time” prompts linking PWUOs and their caregivers to treatment and harm reduction services in response to posts consisting of requests for help securing such resources, adverse experiences related to illicit opioid use, and opioid overdose events; 2) incorporating geographical information systems in social media to enhance linkages to nearby harm reduction and treatment services; 3) promoting support networks among caregivers and peers to sustain protective behavior change, adherence with MOUD, harm reduction, and treatment services; 4) confronting stigma among general Twitter users posting jokes or sarcastic comments about PWUO or policies addressing OUD; and 4) refine a Twitter-based surveillance system using natural language processing to identify OUD-related content, public attitudes, and allocate harm reduction and treatment services over time.

Limitations to this study include potential interrater variability and misinterpretation of posts, lack of generalizability of our initial corpus of Tweets based on our limited number of search terms, and harvesting only a fraction of posts available in the Twitter firehose. Additional qualitative research using Twitter is needed to confirm our findings, including interviews with Twitter users with OUD and textual analysis of post content. Lastly, we included tweets within a rather brief period of time period that may not reflect emerging perceptions and experiences related to OUD.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (K23DA042140-01A1).

References

- 1.Demographics of internet and home broadband usage in the United States. Pew Research Center: Internet, Science & Tech; 2019. June 12 [accessed 2020 May 17]. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/fact-sheet/internet-broadband.

- 2.Demographics of social media users and adoption in the United States. Pew Research Center: Internet, Science & Tech; 2019. June 12 [accessed 2020 May 17]. https://www.pewinternet.org/fact-sheet/social-media/.

- 3.Sinnenberg L, Buttenheim AM, Padrez K, Mancheno C, Ungar L, Merchant RM. Twitter as a tool for health research: a systematic review. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(1):e1–e8. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. 2016 national survey on drug use and health: detailed tables. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mackey TK, Kalyanam J, Katsuki T, Lanckriet G. Twitter-based detection of illegal online sale of prescription opioid. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(12): 1910–5. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2017.303994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chary M, Genes N, Giraud-Carrier C, Hanson C, Nelson LS, Manini AF. Epidemiology from tweets: estimating misuse of prescription opioids in the USA from social media. J Med Toxicol. 2017;13(4):278–86. doi: 10.1007/s13181-017-0625-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sarker A, O’Connor K, Ginn R, Scotch M, Smith K, Malone D, Gonzalez G. Social media mining for toxi-covigilance: automatic monitoring of prescription medication abuse from Twitter. Drug Saf. 2016;39(3): 231–40. doi: 10.1007/s40264-015-0379-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee JD, Nunes EV, Novo P, Bachrach K, Bailey GL, Bhatt S, Farkas S, Fishman M, Gauthier P, Hodgkins CC, et al. Comparative effectiveness of Extended-release naltrexone versus Buprenorphine-naloxone for opioid relapse prevention (X:BOT): a multicentre, open-label, randomised controlled trial. The Lancet. 2018;391(10118):309–18. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32812-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blanco C, Volkow ND. Management of opioid use disorder in the USA: present status and future directions. The Lancet. 2019;393(10182):1760–72. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)33078-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tofighi B, Aphinyanaphongs Y, Marini C, Ghassemlou S, Nayebvali P, Metzger I, Raghunath A, Thomas S. Detecting illicit opioid content on Twitter. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2020;39(3):205–8. doi: 10.1111/dar.13048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Association AP. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5®). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Pub; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Viera AJ, Garrett JM. Understanding interobserver agreement: the kappa statistic. Fam Med. 2005;37(5): 360–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cohen J A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educational and Psychological Measurement. 1960;20(1):37–46. doi: 10.1177/001316446002000104. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vydiswaran VGV, Reddy M. Identifying peer experts in online health forums. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2019;19(S3). doi: 10.1186/s12911-019-0782-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]