Abstract

Background

Overweight and obesity have increased considerably in low- and middle-income countries over the past few decades, particularly among women of reproductive age. This study assessed the role of physical activity, nutrient intake and risk factors for overweight and obesity among women in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania.

Methods

We conducted a cross-sectional survey among 1004 women aged 15–49 years in the Dar es Salaam Urban Cohort Study (DUCS) from September 2018 to January 2019. Dietary intake was assessed using a food frequency questionnaire (FFQ). Physical activity was assessed using the Global Physical Activity Questionnaire (GPAQ) using metabolic equivalent tasks (MET). Modified poison regression models were used to evaluate associations between physical activity and nutrient intake with overweight/obesity in women, controlling for energy and other factors.

Results

The mean (±SD) age of study women was 30.2 (±8.1) years. Prevalence of overweight and obesity was high (50.4%), and underweight was 8.6%. The risk of overweight/obesity was higher among older women (35–49 vs 15–24 years: PR 1.59; 95% CI: 1.30–1.95); women of higher wealth status (PR 1.24; 95% CI: 1.07–1.43); and informally employed and married women. Attaining moderate to high physical activity (≥600 MET) was inversely associated with overweight/obesity (PR 0.79; 95% CI: 0.63–0.99). Dietary sugar intake (PR 1.27; 95% CI: 1.03–1.58) was associated with increased risk, and fish and poultry consumption (PR 0.78; 95% CI: 0.61–0.99) with lower risk of overweight/obesity.

Conclusion

Lifestyle (low physical activity and high sugar intake), age, wealth status, informal employment and marital status were associated with increased risk of overweight/obesity, while consumption of fish and poultry protein was associated with lower risk. The study findings underscore the need to design feasible and high-impact interventions to address physical activity and healthy diets among women in Tanzania.

Keywords: Overweight, Obesity, Women, Nutrients, Physical activity, Tanzania

Background

Overweight and obesity are major public health concerns affecting about half of the global adult population, with prevalence being greater among women compared to men [1, 2]. In low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), overweight and obesity have been increasing at a rapid rate, particularly in urban compared with rural settings [3]. Tanzania is not an exception, with overweight and obesity among women of reproductive age increasing markedly from 21.5 to 28% from 2010 to 2015 [4]. The prevalence of overweight among women in urban areas is twice (42%) as high as that for women in rural areas (21%) [5].

The effects of overweight and obesity on health are well researched. The global burden of disease related to high body mass index (BMI) is high. Globally, high BMI accounts for more than 4 million deaths, two-thirds of which are due to cardiovascular disease [6]. In LMICs, the disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) related to obesity are high and have been steadily rising compared to high-income countries [7]. Among women of childbearing age, overweight and obesity have been associated with increased risk of non-communicable diseases (NCDs), pregnancy complications, caesarean section births, adverse birth outcomes, and infant mortality [8–11]. A recent study conducted in Tanzania reported associations between maternal overweight and increased risk of intrapartum obstetric complications and caesarean section births [12]. Furthermore, offspring of obese mothers have had up to 29% increased risk of hospital admission from cardiovascular disease and 35% increased risk of premature death in adulthood compared to offspring of normal BMI mothers [13].

Several factors may be contributing to increasing overweight and obesity among women in low-income settings and sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), and these include environmental and lifestyle factors, genetics and diseases [14]. Additionally, high socioeconomic status, increasing age, parity, and marital status have also been associated with overweight among women in the region [15, 16].

Physical inactivity and poor dietary patterns characterised by high intake of calorie-rich, processed and refined foods may be key modifiable risk factors for overweight and obesity in SSA [15, 16]. However, little is known about the role of physical activity and nutrients intake among African women of reproductive age because most reports come from national demographic surveys where physical activity and nutrient intake are not assessed. Previous studies in urban African settings assessing nutrient intake among women of reproductive age are limited by small sample sizes affecting the generalisation of their findings [17, 18]. Additionally, understanding the actual contribution of physical activity to women’s BMI is a bit tricky considering women’s participation in energy-demanding domestic activities to support household needs, which is often unaccounted. A clear understanding of the role of these modifiable risk factors in overweight and obesity in the African context may assist in designing appropriate interventions given unprecedented urbanisation, nutrition and dietary transition observed in many African cities [19, 20].

High prevalence of environmental and lifestyle diseases related to high BMI cannot be ignored in Tanzania, considering the upsurge of maternal BMI in urban settings recently reported from the Tanzania national Nutrition Survey [21]. As a country, no effective policies and programs to control overweight in women of reproductive age. This may be due to several factors, including limited pre-pregnancy BMI data from clearly designed populations studies in Tanzania, as in other low-income settings. This study aimed to determine the prevalence and factors associated with overweight and obesity and evaluate the role of physical activity in high BMI among women of reproductive age in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania.

Methods

The study was conducted in the Dar es Salaam Urban Cohort Study (DUCS) site, a Health and Demographic Surveillance System (HDSS) platform based in Ukonga and Gongolamboto wards, in Ilala District of Dar es salaam. The platform is a peri-urban area in Dar es Salaam, the commercial city of Tanzania. The design of the DUCS and the study population have been described in detail elsewhere [22].

The study was a cross-sectional study nested in the HDSS platform. We enrolled women of reproductive age from September 2018 to January 2019. A list of women of reproductive age was initially pulled from the HDSS database that contained participants’ names, dates of birth, and household identification numbers. A simple random sampling technique using random numbers was applied to select households with women of reproductive age. A field worker then visited the selected households to identify women who met the inclusion criteria. Inclusion criteria for the study included (i) women aged 15 to 49 years, (ii) who intended to become pregnant within the next 4 years, (iii) were currently not pregnant based on the last normal menstrual period, and (iv) provided written informed consent. A lottery method was used to select one woman randomly from households with more than one woman. A household replacement was considered for those households in which no woman met the inclusion criteria.

The sample size for the study was calculated based on multiple indicators using a cluster survey formula that factored in the predicted prevalence of overweight/obesity (42%), the proportion of women of reproductive age (30%), average household size in Dar es Salaam (4.0), and the anticipated non-response [5]. Therefore, the minimum sample size was 1012 women for 80% study power and less than 5% level of significance.

Face-to-face interviews were conducted for data collection using a standardized questionnaire. Study research assistants collected information on participants’ socio-demographic and economic characteristics, lifestyle characteristics such as alcohol use, smoking, dietary intake, and levels of physical. Information on pregnancy status and medical history was also collected. Anthropometric measurements, including weight and height, were taken using a calibrated weighing scale to the nearest 100 g and a height board to the nearest cm.

Outcome variable

The outcome in this study was overweight and obesity obtained by computing BMI as weight in kilograms (Kg) divided by height in meters (m) squared. BMI categories followed the WHO recommendations as < 18.50 kg/m2 (underweight), 18.50–24.99 kg/m2 (normal), 25–29.9 kg/ m2 (overweight) and ≥ 30 kg/m2 (obese) [2]. A binary outcome variable was generated by combining overweight or obese and compared against women who had normal BMI.

Assessment of physical activity

Research assistants collected information on physical activity using the Global Physical Activity Questionnaire (GPAQ) [23]. Metabolic Equivalents (MET) assessed physical activity levels [23]. The value of MET for each reported physical activity for each woman was obtained from the compendium of physical activity types. Physical activity was categorized into two groups: moderate-intensity and vigorous-intensity. Moderate-intensity physical activity included brisk walking, dancing, housework and domestic chores, gardening, animal rearing, washing clothes, fetching water, and preparing food. Vigorous-intensity physical activity included climbing a hill, running, fast cycling, swimming, intense farming, competitive sports, traditional games, and wood splitting for fire. Total physical activity (MET-minutes per week) was calculated based on analysis guidelines for physical activity recommended by WHO [24]. Moderate to vigorous physical activity was scored as ≥600 MET-minutes per week, while sedentary physical activity was scored as < 600 MET-minutes per week. Total time spent in vigorous physical activity was categorized as ≥75 min per week and < 75 min per week, and moderate physical activity was categorized as ≥150 min per week and < 150 min per week.

Assessment of macronutrients intake

Dietary information was assessed using a locally adapted Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ) used previously in the study area, containing at least 85 foods [25]. Women were asked to recall foods consumed in the previous 30 days. Nutrient intake was assessed from each reported food consumed by the respondent, based on the Tanzania Food Composition Table (TFCT) [26]. Nutrient values of each food item were calculated by multiplying each food item’s frequency of consumption by the food item’s nutrient content and the specific portion size. Nutrient intake was categorized into tertiles, namely low, medium, and high intake tertiles.

Statistical analysis

Data were cleaned and analyzed by using STATA version 15. Numerical variables were summarized using means and standard deviations, and medians and interquartile range. Categorical variables were summarized using frequencies and percentages. We used the chi-square test to compare the proportion of women with overweight and obesity across explanatory variables, including social-demographic characteristics, physical activity, and dietary diversity.

Potential confounders for each outcome were selected based on associations with the outcome in bivariate regression models at levels of p < 0.1. Confounders considered included age, marital status, education, parity, wealth index, and employment type. The final model was adjusted by total energy intake. Please note, wealth index was created using principal component analysis then categorised into tertile.

A modified Poisson regression model with a robust standard error estimated prevalence ratios (PR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) [27]. The model was used to evaluate the association between physical activity and nutrient intake on overweight and obesity. Modified Poisson regression was used due to the non-convergence of the log-binomial regression model [27]. All analyses were based on a two-tailed significance level at p < 0.05. The Akaike Information Criteria (AIC) was used for model selection, whereby the model with the lowest AIC was considered as a parsimonious model. Tests for trend were conducted for multivariate models for macronutrients.

Results

A total of 1004 women of reproductive age were enrolled in the study. Women in the study had a mean age (±SD) of 30.2 (±8.1) years. Of these, 31.7% were 35 years or older, 57.9% were either married or cohabiting, and 54.4% had no employment. Fifty-four percent of the women had at least two children. The nutrition status of study women was poor, with 8.6% underweight, 27.8% overweight, and 22.6% obese. The overall/combined prevalence of overweight and obesity was 50.4% [Table 1].

Table 1.

Characteristics of women enrolled in the study (N = 1004)

| Variable | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Age group (years) | ||

| 15–24 | 334 | 33.3 |

| 25–34 | 351 | 35.0 |

| 35 and above | 319 | 31.7 |

| Education level | ||

| No education | 59 | 5.9 |

| Primary | 600 | 59.8 |

| Secondary | 267 | 26.6 |

| Above secondary education | 78 | 7.7 |

| Employment | ||

| No employment | 546 | 54.4 |

| Informal employment | 334 | 33.3 |

| Formal employment | 124 | 12.4 |

| Marital Status | ||

| Single | 356 | 35.5 |

| Married/cohabiting | 581 | 57.9 |

| Divorced/separated/widow | 66 | 6.6 |

| Parity | ||

| None | 267 | 26.6 |

| One | 194 | 19.3 |

| Two and above | 543 | 54.1 |

| Household size | ||

| 1–3 | 170 | 16.9 |

| 4–5 | 333 | 33.2 |

| 6 and above | 501 | 49.9 |

| BMI (Kg/M2) | ||

| aMean (±SD) | 25.8 | ±5.8 |

| Underweight | 86 | 8.6 |

| Normal | 412 | 41.0 |

| Overweight | 279 | 27.8 |

| Obese | 227 | 22.6 |

aMean (±Standard deviation)

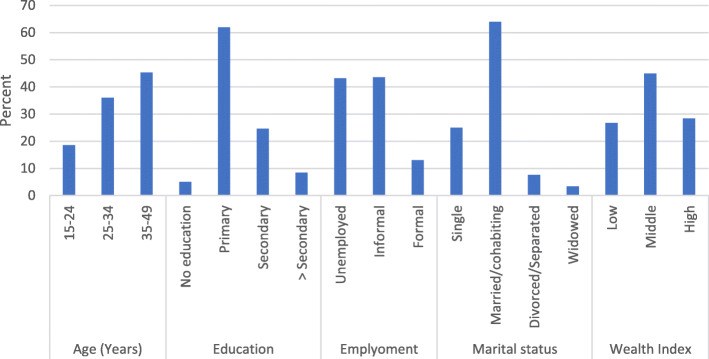

About 43 % (220/506) of overweight and obese women had total physical activity above 600 metabolic equivalents of task (MET for moderate to vigorous physical activity), referred to as sufficient physical activity. Among the overweight and obese women with sufficient total physical activity, 61.9% had primary education level, and 64.0% were married or cohabiting. Additionally, 3.4% of the women were widowed, 5.1% uneducated, and 8.5% with an education level above secondary school [Fig. 1].

Fig. 1.

Socio-demographic characteristics of overweight and obese women with sufficient physical activity (N = 220)

Results from the adjusted analysis for factors associated with overweight and obesity are in Table 2. Compared to women aged 15–24 years, women aged 25–34 years had a 26% higher risk of overweight and obesity (95%CI 1.03–1.54; p = 0.03), while those aged 35 to49 years had a 59% higher risk of the outcome (95%CI 1.30–1.95; p < 0.001), adjusted for physical activity and energy intake. Women who had informal employment had a 14% higher risk of overweight and obesity (95% CI: 1.01–1.29; p = 0.04) compared with those who are not employed. Married or cohabiting women had a 33% higher risk of overweight and obesity (95% CI: 1.11–1.60; p < 0.01) compared with single, divorced or separated women after adjusting for physical activity and energy intake. However, other factors, including education, parity and household size, were not significantly associated with overweight or obesity. Women in the medium and high wealth index tertiles had 25% (PR = 1.25; 95%CI 1.09–1.43; p < 0.01) and 24% (PR = 1.24; 95%CI 1.07–1.43; p < 0.01) higher prevalence of overweight and obesity, compared to women in the low wealth index tertiles in models adjusting for physical activity and energy intake [Table 2].

Table 2.

Associations between participant socio-demographic characteristics and overweight/obesity among women of reproductive age in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania (N = 918)

| Variables | N | n (%) | CPR(95%CI) | P-value | APRa(95%CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years | ||||||

| 15–24 | 334 | 105 (31.4) | 1 | 1 | ||

| 25–34 | 351 | 185 (52.7) | 1.50 (1.25,1.79) | < 0.01 | 1.26 (1.03,1.54) | 0.03 |

| 35–49 | 319 | 218 (68.3) | 1.90 (1.61,2.45) | < 0.01 | 1.59 (1.30,1.95) | < 0.01 |

| Household size | ||||||

| 1–3 | 170 | 88 (51.8) | 1 | |||

| 4–5 | 333 | 181 (54.4) | 1.09 (0.84,1.41) | 0.52 | ||

| 6 and above | 501 | 239 (47.7) | 0.94 (0.73,1.21) | 0.64 | ||

| Education | ||||||

| No education | 59 | 28 (47.5) | 1 | |||

| Primary | 600 | 329 (54.8) | 1.12 (0.86,1.16) | 0.40 | ||

| Secondary | 267 | 114 (42.7) | 0.94 (0.70,1.25) | 0.67 | ||

| Above secondary | 78 | 37 (47.4) | 1.04 (0.75,1.47) | 0.78 | ||

| Type of Employment | ||||||

| No employment | 546 | 242 (44.3) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Informal | 334 | 199 (59.6) | 1.28 (1.13,1.45) | < 0.01 | 1.14 (1.01,1.29) | 0.04 |

| Formal | 124 | 67 (54.0) | 1.17 (0.98,1.40) | 0.08 | 1.06 (0.90,1.26) | 0.48 |

| Marital Status | ||||||

| Single | 356 | 114 (32.0) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Married/cohabiting | 581 | 357 (61.5) | 1.66 (1.42,1.94) | < 0.01 | 1.33 (1.11,1.60) | < 0.01 |

| Divorced/separated | 66 | 36 (54.6) | 1.52 (1.17,1.97) | < 0.01 | 1.21 (0.93,1.59) | 0.16 |

| Parity | ||||||

| 0–1 | 194 | 97 (50.0) | 1 | |||

| > 1 | 543 | 329 (60.6) | 1.16 (1.00,1.34) | 0.06 | ||

| Wealth index Score | ||||||

| Low | 335 | 150 (44.8) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Middle | 395 | 210 (53.2) | 1.21 (1.05,1.39) | 0.01 | 1.25 (1.09,1.4) | < 0.01 |

| High | 274 | 148 (54.0) | 1.18 (1.12,1.61) | 0.03 | 1.24 (1.07,1.4) | < 0.01 |

Abbreviations: CPR Crude prevalence ratio; APR Adjusted prevalence ratio

aAdjusted for physical activity and energy intake

Total physical activity and minutes per week of vigorous physical activity were inversely associated with overweight and obesity adjusted for other factors [Table 3]. Women who performed moderate to vigorous physical activity of at least 600 MET per week had a 21% lower prevalence of overweight and obesity compared with those with a sedentary lifestyle (PR = 0.79; 95% CI 0.63–0.99; p = 0.04). Women who performed vigorous physical activity at least 75 min per week had a 32% lower prevalence of overweight and obesity than those who performed less than 75 min of vigorous physical activity per week (PR = 0.68; 95%CI 0.47–0.99; p = 0.04). However, work-related moderate physical activity (minutes per week of moderate physical activity) and days of moderate physical activity were not significantly associated with overweight and obesity [Table 3].

Table 3.

Associations of physical activity and the risk of overweight and obesity among women of reproductive age in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania (n = 918)

| Variable | CPR(95%CI) | P-value | APR a(95%CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total physical activity | ||||

| Sedentary (≤600 MET) | 1 | 1 | ||

| MVPA (> 600 MET) | 1.00 (0.89,1.13) | 0.99 | 0.79 (0.63,0.99) | 0.04 |

| Minutes per week of vigorous physical activity | ||||

| < 75 min | 1 | 1 | ||

| ≥ 75 min | 1.13 (0.86,1.48) | 0.39 | 0.68 (0.47,0.99) | 0.04 |

| Minutes per week of moderate physical activity | ||||

| < 150 min | 1 | 1 | ||

| ≥ 150 min | 1.01 (0.88,1.15) | 0.93 | 1.02 (0.81,1.27) | 0.90 |

| Days of vigorous physical activity per week | ||||

| None | 1 | |||

| 1–3 days/week | 1.32 (1.03,1.71) | 0.03 | ||

| 4–7 days/week | 1.15 (0.92,1.45) | 0.22 | ||

| Days of moderate physical activity per week | ||||

| None | 1 | |||

| 1–3 days/week | 0.91 (0.73,1.14) | 0.43 | ||

| 4–7 days/week | 1.01 (0.89, 0.14) | 0.92 | ||

| Days of walking or driving a bicycle at least 10 min | ||||

| None | 1 | |||

| 1–3 days/week | 0.90 (0.78, 1.04) | 0.15 | ||

| 4–7 days/week | 0.97 (0.84, 1.11) | 0.67 | ||

Abbreviations: CRP Crude prevalence ratio; APR Adjusted prevalence ratio; MET Metabolic Equivalent of Task; MVPA Moderate to Vigorous Physical Activity

aAdjusted prevalence ratio – adjusted for energy intake, age, wealth index, type of employment, marital status, education and number of parity

Higher intake of sugar, total fat, animal protein were positively associated with overweight and obesity. In comparison, a higher intake of protein from fish and poultry was associated with a lower risk of overweight and obesity. There was a significant increase in overweight and obesity with the increased consumption of animal protein. Women in the highest tertile of animal protein intake had a higher risk of overweight and obesity (PR = 1.19, 95%CI: 1.01, 1.35), p for trend 0.26. Similarly, women in the highest tertile of sugar consumption had a higher risk of overweight/obesity (PR = 1.27, 95%CI: 1.03, 1.58, p for trend < 0.01). Women in the highest tertile of protein intake from fish and poultry meat had a 22% lower risk of overweight and obesity (PR = 0.78, 95%CI: 0.61.0.99, p for trend 0.03) [Table 4].

Table 4.

Associations between Macronutrient Intake with overweight/obese among women of reproductive age in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania (N = 918)

| Macronutrients | Overweight /obese n(%) |

CPR a(95%CI) | P-value | APRa(95%CI) | P-value | P value for trend |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carbohydrate (g) | ||||||

| Low | 159 (52.0) | 1 | 1 | |||

| Medium | 179 (58.5) | 1.07 (0.92,1.23) | 0.37 | 1.15 (0.91,1.46) | 0.25 | 0.47 |

| High | 168 (54.9) | 1.11 (0.95,1.30) | 0.19 | 1.15 (0.84,1.58) | 0.39 | |

| Animal Protein(g) | ||||||

| Low | 161 (52.6) | 1 | 1 | |||

| Medium | 171 (55.7) | 1.13 (0.98,1.30) | 0.09 | 1.17 (1.01,1.35) | 0.03 | 0.26 |

| High | 168 (57.1) | 1.12 (0.94,1.32) | 0.20 | 1.19 (1.02,1.39) | 0.03 | |

| Total fat (g) | ||||||

| Low | 176 (57.5) | 1 | 1 | |||

| Medium | 176 (57.5) | 1.12 (0.96,1.30) | 0.14 | 1.21 (0.98,1.50) | 0.10 | 0.07 |

| High | 154 (57.5) | 1.13 (0.98,1.32) | 0.10 | 1.22 (1.03,1.45) | 0.02 | |

| Fish & Poultry protein (g) | ||||||

| Low | 156 (50.5) | 1 | 1 | |||

| Medium | 174 (56.0) | 1.05 (0.85,1.30) | 0.63 | 0.83 (0.70,0.99) | 0.04 | 0.03 |

| High | 176 (59.1) | 1.04 (0.84, 1.29) | 0.74 | 0.78 (0.61,0.99) | 0.04 | |

| Sugar (g) | ||||||

| Low | 165 (53.9) | 1 | 1 | |||

| Medium | 169 (55.2) | 1.01 (0.87,1.16) | 0.10 | 1.13 (0.98,1.31) | 0.09 | < 0.01 |

| High | 172 (56.2) | 1.05 (0.90,1.23) | 0.07 | 1.27 (1.03,1.58) | 0.01 | |

| Fiber (g) | ||||||

| Low | 243 (53.9) | 1 | 1 | |||

| Medium | 140 (56.7) | 0.94 (0.81, 1.09) | 0.42 | 0.95 (0.81,1.12) | 0.57 | 0.57 |

| High | 123 (55.9) | 1.02 (0.89, 1.17) | 0.81 | 0.95 (0.77,1.17) | 0.65 | |

Abbreviations: CRP Crude prevalence ratio

aAdjusted prevalence ratio -adjusted for physical activity, energy intake, age, wealth index, type of employment, marital status, number of parity and education level

Discussion

Our findings show that the combined prevalence of overweight and obesity among women intending to become pregnant within the next 4 years is very high in Tanzania. Overall, we found that being older, having informal employment and middle to high socioeconomic status were associated with overweight and obesity among women in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. The study found an association between vigorous physical activity and decreased overall prevalence of overweight and obesity. Sugary dietary intake was associated with an increased prevalence of overweight and obesity. Consumption of protein from fish and poultry was associated with a lower risk of overweight and obesity after adjusting for energy intake and physical activity.

More than half of the women in our study are either overweight or obese, which is higher than the 2015 national prevalence in urban settings (50.7% vs 42.0%) in Tanzania [5]. The high prevalence of overweight and obesity in the study area may explain the impact of economic development, nutrition transition and women’s empowerment on overweight and obesity that is more pronounced in African cities like Dar es salaam [17, 19]. Women in this study had a 6-fold higher prevalence of overweight and obesity when compared with the underweight (50.4% vs 8.6%). This is of great concern given most nutritional counselling observed in many antenatal health care services; the emphasis is on maternal weight gain and less on the overweight and obese control (a personal conversation with the health facility providers in the study area).

A high prevalence of maternal obesity is also reported in a systematic review and meta-analysis across Africa, ranging from 6.5 to 50.7% [28]. Economic and nutrition transition remain the core reasons demonstrated to expose women to sedentary life and unhealthy diets [29, 30]. Such a high prevalence of overweight and obesity in women who intend to conceive within the next few years is alarming considering the reported maternal and newborn adverse outcomes associated with high pre-pregnancy BMI [9, 11].

Being older, having informal employment, and middle to high socioeconomic status were associated with an increased prevalence of overweight and obesity in this study. These findings are consistent with other studies that reported a higher prevalence of overweight and obesity in older women [15, 31, 32]. Increased parity, hormonal changes, and a less active lifestyle may attribute obesity among older women [33, 34]. In addition, weight retained during pregnancy is often difficult for women to lose, even for obese women, contributing to increased BMI over time [35].

Women who were self-employed or under the informal employment sector, such as street vendors, shopkeepers, and tailors, had a higher prevalence of overweight and obesity than women who were unemployed or formally employed. The role of employment status as a determinant of BMI is not clear. Studies have shown that white-collar workers are at the greatest risk of low occupational physical activity levels and sedentary behaviour [36, 37]. In this study, women under formal employment in most cases were in the white-collar job category; however, this was not associated with an increased risk of overweight and obesity. There is, therefore, a need to understand the nature and actual contribution of specific employment status to women’s BMI.

We found that women with higher economic status had a higher prevalence of overweight and obesity. Similar findings have also been reported by other studies from SSA, where socioeconomic status was an important determinant of overweight and obesity [15, 32, 38]. This may be due to socio-cultural factors and perceptions in many LMICs favouring women having larger body size [39, 40]. Being obese or overweight in many African countries have been perceived as a sign of being wealthy, having enough to eat, and less associated with diseases such as HIV infection [41, 42]. More importantly, more affluent households can afford more calories in their diets, having financial power to purchase processed and unhealthy foods, eat fast food from restaurants etc., while also being less likely to be physically active [43]. The findings are contrary to many studies in high-income countries where adults with higher socioeconomic status have a low prevalence of obesity [44, 45].

Besides controlling dietary intake, having sufficient exercise and physical activity is considered an effective approach for controlling weight gain [46]. This is in line with our findings that women who met moderate to vigorous total physical activity criteria (MVPA) had a lower prevalence of overweight and obesity by 21%. Similar findings have been reported from Ghana, where women who did not meet the recommended physical activity level had an increased risk of obesity by 23% [47]. Physical activity, including aerobic exercises, reduces fat mass and body weight [48].

We found that high sugar consumption was associated with a higher prevalence of overweight and obesity, which is consistent with findings from a systematic review in SSA. The review found that a steady increase in the availability and consumption of energy-rich foods from the 1980s had contributed substantially to the increase of obesity in the region [49]. High sugar and beverages consumption above 10% of the total daily energy requirement has increased in recent years, especially in urban settings, including Tanzania [50]. Thus, this calls for immediate attention, given that high sugar intake is associated with non-communicable diseases [51]. Animal protein and fat intake were not associated with an increased risk of overweight and obesity. This is contrary to the USA and European study, which associated animal protein intake with increased global and abdominal obesity risk. Fish and poultry protein intake was significant associated with a low risk of overweight and obesity. Compared to animal (red) meat, fish and chicken have less saturated fat and cholesterol, which justifies having less risk of overweight and obesity [52].

Our study is one of the few studies in SSA that has measured physical activity and dietary intake given the current situation of unprecedented urbanization and dietary transmission in many African countries. Therefore, we believe the findings are vital to underpin the importance of addressing overweight and obesity determinants in the region, including physical activity and healthy diets. However, we cannot ignore the possibility of a recall bias as some respondents may fail to remember foods consumed in the past 30 days. Additionally, we utilize a cross-sectional study design which may be affected by confounding. However, we tried to address the confounding effect by adjusted for energy intake and known potential confounders. Additionally, in the models for dietary intake, we controlled for physical activity.

Conclusion

The overall prevalence of overweight and obesity among women of reproductive age who intend to conceive within the next 4 years was very high. Overweight and obesity were significantly associated with a sedentary lifestyle, wealth, older age, informal employment status, and marital status. High sugar intake was associated with a higher risk of overweight and obesity, while protein consumption from fish and poultry was associated with lower risk. The findings of this study underscore the need to design culturally-sensitive, feasible and potentially high-impact interventions to address the modifiable risk factors of physical activity and healthy diets to control the upsurge of pre-pregnancy overweight and obesity among women in SSA countries.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset generated during the current study are not publicly available due to the Africa Academy for Public Health (AAPH) data policy but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgements

We thank the participating women for their cooperation and all Ukonga HDSS field staff involved in the study, under the supervision of Alli Mangara. Special thanks are given to Patrick Kazonda, Neema Gamasa, and Zohra Lukmanji for managing data collection tool and training field workers.

Abbreviations

- BMI

Body Mass Index

- DUCS

Dar es Salaam Urban Cohort Study

- DAILYs

Disability-Adjusted Life Years

- FFQ

Food Frequency Questionnaire

- GPAQ

Global Physical Activity Questionnaire

- LMICs

Low- and Middle-Income Countries

- MET

Metabolic Equivalent Tasks

- NCD

Non-Communicable Diseases

- TFNC

Tanzania Food Composition Table

- WHO

World Health Organization

Authors’ contributions

The study was designed by DM and WWF, assisted by JK, GL and TWB. Enrolment and follow-up of participants in the field were coordinated by DM and MM. HAP conducted data analysis, assisted by IM, IBM and SM. DM and HAP wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors participated in data interpretation, review and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The study was funded by a special sub-grant from the Institute of Global Health at the Heidelberg University. DM was supported by the Fogarty International Center, of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number D43 TW 007886.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset of the current study is available from the corresponding author based on a reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical clearance was obtained from the Tanzania National Research Ethics Committee (NatREC) with reference number NIMR/HQ/R.8a/Vol.IX/2589. The local authorities of the region and district were informed about the study objectives and granted their approval. The study was conducted in full compliance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all study participants after informed about the study. For the minors, informed consent was obtained from their parents or legal guardians after providing the assent. Confidentiality of the data obtained from participants was strictly secured and maintained.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Bhurosy T, Jeewon R. Overweight and obesity epidemic in developing countries: a problem with diet, physical activity, or socioeconomic status? ScientificWorldJournal. 2014;2014:964236. doi: 10.1155/2014/964236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organisation. Obesity and overweight. Geneva: WHO; 2020. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight.

- 3.Ford ND, Patel SA, Narayan KM. Obesity in low- and middle-income countries: burden, drivers, and emerging challenges. Annu Rev Public Health. 2017;38(1):145–164. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031816-044604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Bureau of Statistics, ICF Macro: Tanzania Demographic and Health Survey 2010. Dar es Salaam: NBS; 2011. https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR243/FR243%5B24June2011%5D.pdf.

- 5.Tanzania Ministry of Health, NBS, OCGS, ICF: Tanzania Demographic and Health Survey and Malaria Indicator Survey (TDHS-MIS) 2015-16. Dar es Salaam: MoHCDGEC; 2016.https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/fr321/fr321.pdf.

- 6.Collaborators GBDO, Afshin A, Forouzanfar MH, Reitsma MB, Sur P, Estep K, Lee A, Marczak L, Mokdad AH, Moradi-Lakeh M, et al. Health effects of overweight and obesity in 195 countries over 25 years. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(1):13–27. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1614362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lim SS, Vos T, Flaxman AD, Danaei G, Shibuya K, Adair-Rohani H, Amann M, Anderson HR, Andrews KG, Aryee M, et al. A comparative risk assessment of burden of disease and injury attributable to 67 risk factors and risk factor clusters in 21 regions, 1990-2010: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380(9859):2224–2260. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61766-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Catalano PM, Ehrenberg HM. The short- and long-term implications of maternal obesity on the mother and her offspring. BJOG. 2006;113(10):1126–1133. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2006.00989.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cresswell JA, Campbell OM, De Silva MJ, Filippi V. Effect of maternal obesity on neonatal death in sub-Saharan Africa: multivariable analysis of 27 national datasets. Lancet. 2012;380(9850):1325–1330. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60869-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Van Der Linden EL, Browne JL, Vissers KM, Antwi E, Agyepong IA, Grobbee DE, Klipstein-Grobusch K. Maternal body mass index and adverse pregnancy outcomes: a ghanaian cohort study. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2016;24(1):215–222. doi: 10.1002/oby.21210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yu Z, Han S, Zhu J, Sun X, Ji C, Guo X. Pre-pregnancy body mass index in relation to infant birth weight and offspring overweight/obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2013;8(4):e61627. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mwanamsangu AH, Mahande MJ, Mazuguni FS, Bishanga DR, Mazuguni N, Msuya SE, Mosha D. Maternal obesity and intrapartum obstetric complications among pregnant women: retrospective cohort analysis from medical birth registry in northern Tanzania. Obes Sci Pract. 2020;6(2):171–180. doi: 10.1002/osp4.395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reynolds RM, Allan KM, Raja EA, Bhattacharya S, McNeill G, Hannaford PC, Sarwar N, Lee AJ, Bhattacharya S, Norman JE. Maternal obesity during pregnancy and premature mortality from cardiovascular event in adult offspring: follow-up of 1 323 275 person years. BMJ. 2013;347(aug13 1):f4539. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f4539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gaillard R, Durmus B, Hofman A, Mackenbach JP, Steegers EA, Jaddoe VW. Risk factors and outcomes of maternal obesity and excessive weight gain during pregnancy. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2013;21(5):1046–1055. doi: 10.1002/oby.20088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mukora-Mutseyekwa F, Zeeb H, Nengomasha L, Kofi Adjei N: Trends in Prevalence and Related Risk Factors of Overweight and Obesity among Women of Reproductive Age in Zimbabwe, 2005-2015. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2019, 16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Sartorius B, Veerman LJ, Manyema M, Chola L, Hofman K. Determinants of obesity and associated population Attributability, South Africa: empirical evidence from a National Panel Survey, 2008-2012. PLoS One. 2015;10(6):e0130218. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0130218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mbochi RW, Kuria E, Kimiywe J, Ochola S, Steyn NP. Predictors of overweight and obesity in adult women in Nairobi Province, Kenya. BMC Public Health. 2012;12(1):823. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Suara SB, Siassi F, Saaka M, Foroshani AR, Asadi S, Sotoudeh G. Dietary fat quantity and quality in relation to general and abdominal obesity in women: a cross-sectional study from Ghana. Lipids Health Dis. 2020;19(1):67. doi: 10.1186/s12944-020-01227-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fox A, Feng W, Asal V. What is driving global obesity trends? Globalization or "modernization"? Glob Health. 2019;15(1):32. doi: 10.1186/s12992-019-0457-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Popkin BM, Adair LS, Ng SW. Global nutrition transition and the pandemic of obesity in developing countries. Nutr Rev. 2012;70(1):3–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2011.00456.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tanzania Ministry of Health, Tanzania Food & mNutrition Centre, National Bureau of Statistics, OCGS, UNICEF: Tanzania National Nutrition Survey using SMART Methodology (TNNS) 2018. Dar es Salaam: MoHCDGEC; 2018. https://www.unicef.org/tanzania/media/2141/file/Tanzania%20National%20Nutrition%20Survey%202018.pdf.

- 22.Leyna GH, Berkman LF, Njelekela MA, Kazonda P, Irema K, Fawzi W, Killewo J. Profile: the Dar Es Salaam health and demographic surveillance system (Dar es Salaam HDSS) Int J Epidemiol. 2017;46(3):801–808. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyw324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.WHO . Global Physical Activity Questionnaire ( GPAQ ) WHO STEPwise approach to NCD risk factor surveillance. Geneva: WHO; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 24.WHO . Global Physical Activity Questionnaire (GPAQ) Geneva: WHO; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zack RM, Irema K, Kazonda P, Leyna GH, Liu E, Gilbert S, Lukmanji Z, Spiegelman D, Fawzi W, Njelekela M, Killewo J, Danaei G. Validity of an FFQ to measure nutrient and food intakes in Tanzania. Public Health Nutr. 2018;21(12):2211–2220. doi: 10.1017/S1368980018000848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lukmanji Z, Hertzmark E, Mlingi N, Assey V, Ndossi G, Fawzi W. Tanzania food composition tables. HSPH, Dar es Salaam: MUHAS-TFNC; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zou G. A modified poisson regression approach to prospective studies with binary data. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159(7):702–706. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Onubi OJ, Marais D, Aucott L, Okonofua F, Poobalan AS. Maternal obesity in Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Public Health (Oxf) 2016;38(3):e218–e231. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdv138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.FWorld Health Organisation, Food and Agriculture Organization of the UN: Broken food systems and poor diets are increasing rates of obesity. Geneva: WHO; 2019. http://www.emro.who.int/media/news/broken-food-systems-and-poor-diets-are-increasing-rates-of-obesity.html.

- 30.Templin T, Cravo Oliveira Hashiguchi T, Thomson B, Dieleman J, Bendavid E. the overweight and obesity transition from the wealthy to the poor in low- and middle-income countries: a survey of household data from 103 countries. PLoS Med. 2019;16(11):e1002968. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Abrha S, Shiferaw S, Ahmed KY. Overweight and obesity and its socio-demographic correlates among urban Ethiopian women: evidence from the 2011 EDHS. BMC Public Health. 2016;16(1):636. doi: 10.1186/s12889-016-3315-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mndala L, Kudale A: Distribution and social determinants of overweight and obesity: a cross-sectional study of non-pregnant adult women from the Malawi Demographic and Health Survey (2015-2016). Epidemiol Health 2019, 41:e2019039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Karvonen-Gutierrez C, Kim C. Association of mid-Life Changes in body size, body composition and obesity status with the menopausal transition. Healthcare (Basel). 2016;4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Li W, Wang Y, Shen L, Song L, Li H, Liu B, Yuan J, Wang Y. Association between parity and obesity patterns in a middle-aged and older Chinese population: a cross-sectional analysis in the Tongji-Dongfeng cohort study. Nutr Metab (Lond) 2016;13(1):72. doi: 10.1186/s12986-016-0133-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ostbye T, Peterson BL, Krause KM, Swamy GK, Lovelady CA. Predictors of postpartum weight change among overweight and obese women: results from the active mothers postpartum study. J Women's Health (Larchmt) 2012;21(2):215–222. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2011.2947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Smith L, McCourt O, Sawyer A, Ucci M, Marmot A, Wardle J, Fisher A. A review of occupational physical activity and sedentary behaviour correlates. Occup Med (Lond) 2016;66(3):185–192. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqv164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Van Domelen DR, Koster A, Caserotti P, Brychta RJ, Chen KY, McClain JJ, Troiano RP, Berrigan D, Harris TB. Employment and physical activity in the U.S. Am J Prev Med. 2011;41(2):136–145. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.03.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Doku DT, Neupane S. Double burden of malnutrition: increasing overweight and obesity and stall underweight trends among Ghanaian women. BMC Public Health. 2015;15(1):670. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-2033-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Griffiths P, Bentley M. Women of higher socio-economic status are more likely to be overweight in Karnataka, India. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2005;59(10):1217–1220. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Subramanian SV, Perkins JM, Ozaltin E, Davey Smith G. Weight of nations: a socioeconomic analysis of women in low- to middle-income countries. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;93(2):413–421. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.110.004820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Devanathan R, Esterhuizen TM, Govender RD. Overweight and obesity amongst black women in Durban, KwaZulu-Natal: a ‘disease’ of perception in an area of high HIV prevalence. Afr J Prim Health Care Fam Med. 2013;5:450. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ettarh R, Van de Vijver S, Oti S, Kyobutungi C. Overweight, obesity, and perception of body image among slum residents in Nairobi, Kenya, 2008-2009. Prev Chronic Dis. 2013;10:E212. doi: 10.5888/pcd10.130198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hruby A, Hu FB. The epidemiology of obesity: a big picture. Pharmacoeconomics. 2015;33(7):673–689. doi: 10.1007/s40273-014-0243-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hoebel J, Kuntz B, Kroll LE, Schienkiewitz A, Finger JD, Lange C, Lampert T. Socioeconomic inequalities in the rise of adult obesity: a time-trend analysis of National Examination Data from Germany, 1990-2011. Obes Facts. 2019;12(3):344–356. doi: 10.1159/000499718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Roskam AJ, Kunst AE, Van Oyen H, Demarest S, Klumbiene J, Regidor E, Helmert U, Jusot F, Dzurova D. Mackenbach JP, for additional participants to the s: comparative appraisal of educational inequalities in overweight and obesity among adults in 19 European countries. Int J Epidemiol. 2010;39(2):392–404. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyp329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kim BY, Choi DH, Jung CH, Kang SK, Mok JO, Kim CH. Obesity and physical activity. J Obes Metab Syndr. 2017;26(1):15–22. doi: 10.7570/jomes.2017.26.1.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lartey ST, Magnussen CG, Si L, Boateng GO, de Graaff B, Biritwum RB, Minicuci N, Kowal P, Blizzard L, Palmer AJ. Rapidly increasing prevalence of overweight and obesity in older Ghanaian adults from 2007-2015: evidence from WHO-SAGE waves 1 & 2. PLoS One. 2019;14(8):e0215045. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0215045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Willis LH, Slentz CA, Bateman LA, Shields AT, Piner LW, Bales CW, Houmard JA, Kraus WE: Effects of aerobic and/or resistance training on body mass and fat mass in overweight or obese adults. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2012, 113:1831–1837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 49.Steyn NP, McHiza ZJ. Obesity and the nutrition transition in sub-Saharan Africa. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2014;1311(1):88–101. doi: 10.1111/nyas.12433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.WHO . Guideline: sugar intake for adults and children. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Delli Bovi AP, Di Michele L, Laino G, Vajro P. Obesity and obesity related diseases, sugar consumption and bad Oral health: a fatal epidemic mixtures: the pediatric and Odontologist point of view. Transl Med UniSa. 2017;16:11–16. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gilsing AM, Weijenberg MP, Hughes LA, Ambergen T, Dagnelie PC, Goldbohm RA, Brandt PA, Schouten LJ. Longitudinal changes in BMI in older adults are associated with meat consumption differentially, by type of meat consumed. J Nutr. 2012;142(2):340–349. doi: 10.3945/jn.111.146258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset generated during the current study are not publicly available due to the Africa Academy for Public Health (AAPH) data policy but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

The dataset of the current study is available from the corresponding author based on a reasonable request.