Abstract

Self-regulation is a dynamic process wherein executive processes (EP) delay, minimize or desist prepotent responses (PR) that arise in situations that threaten well-being. It is generally assumed that, over the course of early childhood, children expand and more effectively deploy their repertoire of EP-related strategies to regulate PR. However, longitudinal tests of these assumptions are scarce in part because self-regulation has been mostly studied as a static construct. This study engages dynamic systems modeling to examine developmental changes in self-regulation between ages 2 and 5 years. Second-by-second time-series data derived from behavioral observations of 112 children (63 boys) faced with novel laboratory-based situations designed to elicit wariness, hesitation, and fear were modeled using differential equation models designed to capture age-related changes in the intrinsic dynamics and bidirectional coupling of PR (fear/wariness) and EP (strategy use). Results revealed that dynamic models allow for the conceptualization and measurement of fear regulation as intrinsic processes as well as direct and indirect coupling between PR and EP. Several patterns of age-related changes were in line with developmental theory suggesting that PR weakened and was regulated more quickly and efficiently by EP at age 5 than at age 2. However, most findings were in the intrinsic dynamics and moderating influences between PR and EP rather than direct influences. The findings illustrate the precision with which specific aspects of self-regulation can be articulated using dynamic systems models, and how such models can be used to describe the development of self-regulation in nuanced and theoretically meaningful ways.

Keywords: longitudinal analysis, self-regulation, fear, multiple time-scale, emotion regulation

Self-regulation is a fundamental human faculty that can be conceptualized as a dynamic process in which individuals engage executive processes (EP) to delay, minimize or desist reflexive emotions and behaviors (i.e., a prepotent response; PR) in response to situations that threaten well-being (Cole, Martin, & Dennis, 2004). Evidence indicates that children begin to initiate strategies that involve EP during early childhood (e.g., Mangelsdorf, Shapiro, & Marzolf, 1995). That these strategies are effective is implied but thus far not tested empirically, in part due to the need for data analytic tools that simultaneously capture (a) instantaneous, short-term, dynamic relations between PR and EP and (b) age-related, longer-term, changes in those dynamics. The present investigation integrates dynamic systems modeling, specifically differential equation models (Boker & Nesselroade, 2002), into a multiple time-scale framework (Ram & Gerstorf, 2009) to examine changes in self-regulation dynamics between ages 2 and 5 years.

Adaptive Nature of Self-Regulation

The ability to self-regulate is one of the best early indicators of future socioemotional competence and health (Mischel, Shoda, & Rodriguez, 1989; Moffitt et al., 2011). It includes, among other attributes, the ability to regulate fear-related action. PR includes wariness, distress, negative emotionality, hesitation, withdrawal, or fear when encountering unexpected, novel circumstances like being approached by an unfamiliar person (henceforward discussed as fear). Stranger fear emerges at 7 months, increases through infancy (Sroufe, 1977), and remains dominant in toddlerhood (Brooker et al., 2013). To navigate the unexpected novelties of life successfully, children must learn to regulate this form of PR. Difficulty doing so is associated with a wide range of socioemotional difficulties, including social withdrawal and anxiety (Clauss & Blackford, 2012; Pérez-Edgar & Fox, 2005).

Developmental Changes in Self-Regulation

In early childhood, the ability to regulate fear-related PR involves behavioral strategies such as self-comforting (e.g., self-touching), distraction (e.g., shifting attention from the source of threat), and instrumental action (e.g., engaging in and exerting control over the situation; Grolnick, Bridges, & Connell, 1996; Stansbury & Sigman, 2000). Infants are able to orient away from sources of distress with momentary reductions in distress (Buss & Goldsmith, 1998; Stifter & Braungart, 1995) but they still rely on adults to resolve such distress (Diener & Mangelsdorf, 1999; Harman, Rothbart, & Posner, 1997).

Kopp (1982) posited that, in the third year, children initiate strategies that recruit EP without adult direction. Evidence of age-related changes are consistent with that view (Cole et al., 2011; Hodgins & Lander, 1997; Mangelsdorf et al., 1995; Morasch & Bell, 2012; Rothbart, Ziaie, & O’Boyle, 1992). Yet, little is known about the effectiveness of young children’s EP and whether there are increases in EP effectiveness between toddler and preschool ages. Such evidence requires an analysis of the dynamic interplay between PR and EP at multiple ages. Between ages 2 and 5 years, EP should become more efficient because as cognitive processes develop, PR can be managed more and more quickly.

Limitations in Operationalizing Self-Regulation

To study how effectively EP alters PR, we need dynamic conceptualization and measurement of EP and PR dynamics. Although early childhood studies measure PR and EP by micro-coding observed behavior in emotion-eliciting situations, the time series dynamics are overlooked by the use of summary statistics (e.g., total number of times a child used EP). Sequential and contingency analyses (Bakeman & Quera, 2011) allow assessment of the effects of strategies on emotional reactions but only reveal momentary effectiveness (e.g., Buss & Goldsmith, 1998; Crockenberg & Leerkes, 2004; Diener & Mangelsdorf, 1999; Stifter & Braungart, 1995). Contingency analyses do not reveal if, as children age, PR simply decays more quickly regardless of EP, EP is deployed more readily, or PR is more effectively regulated by EP. Moreover, this approach does not take into account potential influences of PR on EP (for an exception see Ekas, Braungart-Rieker, Lickenbrock, Zentall, & Maxwell, 2011). Our approach investigates bidirectional influences of PR and EP, allowing us to ask, for example, whether there are age-related changes in the tendency of PR to interfere with EP effectiveness. Recently, it was shown that for some 3-year-olds, if the level of PR is too high, it can overwhelm EP, regulatory interference (Cole, Bendezú, Ram, & Chow, 2017). In the context of fear, a toddler may freeze and use fewer strategies (Buss & Goldsmith, 1998; Buss et al., 2004). Alternatively, toddlers’ EP deployment may not be as effective at lowering PR, as implied by evidence that children recruit more neural resources than adults to inhibit PR (Durston et al., 2002). In this case, there may be developmental differences in regulatory efficiency rather than in interference (Cole et al., 2017). A dynamic systems modeling framework can be used to examine how ongoing changes in PR and EP influence each other and how these influences change with age.

Dynamic Systems Model of Self-Regulation

The dynamic systems approach emphasizes the importance of studying development as a dynamic process involving changes across different time scales – across moments and across years (Hollenstein, Lichtwarck-Aschoff, & Potworowski, 2013; Ram & Gerstorf, 2009). Based in mathematical principles that explain complex and non-linear systems, dynamic systems approaches have been used to study developmental changes in cognition and locomotion (Thelen & Smith, 1994), social interaction (Hollenstein & Lewis, 2006; Lunkenheimer, Olson, Hollenstein, Sameroff, & Winter, 2011), and emotion (Lewis, 2005).

Change processes can be described mathematically by relations among a set of derivatives that indicate, at each moment in time, the location (0th derivative), velocity (1st derivative), and acceleration (2nd derivative) of target variables (e.g., EP and PR). Thus, fear responses and strategy use can be characterized with respect to momentary features (i.e., intensity, level, or location), moment-to-moment changes (velocity/speed) and changes in rate of change (acceleration). As shown in Figure 1, children’s PR and EP manifestations cannot be fully captured by level alone. A child in a novel situation may withdraw, but then look with interest, but then gaze away, but then turn and look again, perhaps approach and say something but then withdraw again. This way, children’s PR and EP manifestations contain degrees of momentary change (velocity) and shifts in the degree of change (acceleration/ deceleration). By combining all three sources (level, velocity, and acceleration) the data are fully described as oscillations. The damped linear oscillator model is a second-order differential equation describing moment-to-moment acceleration of a process as a function of its current location and velocity (Boker & Nesselroade, 2002). Such models have been useful in representing a variety of mechanical, biological, and psychological processes, including hormonal changes across the menstrual cycle (Boker, Neale, & Klump, 2014), week-to-week emotional oscillations (Chow, Ram, Boker, Fujita, & Clore, 2005), synchrony of romantic partners’ physiological responses (Helm, Sbarra, & Ferrer, 2012), coordination dynamics of motor movements (Butner, Amazeen, & Mulvey, 2005), and emotion co-regulation between partners (Butner, Diamond, & Hicks, 2007).

Figure 1.

Raw composite time-series for one example child at age 2 (upper panel) and age 5 (lower panel). Epoch-to-epoch changes across the 4.5-minute novel stranger task of the child’s PR and EP are shown in red and blue, respectively.

We use a variant of this model to describe children’s regulation of their initial withdrawal from novel stimuli. Specifically, we formulate a damped linear oscillator model to describe relations among moment-to-moment changes, quantified in terms of level, velocity, and acceleration/deceleration, in children’s PR (fear, hesitation, withdrawal) and EP (self-soothing and engagement) when approached by a stranger.

The damped oscillator model is useful, in part, because the represented systems have three inherent properties (Boker & Laurenceau, 2007). First, the model posits that the targeted system has a homeostasis, or goal state, defined as a particular level (of EP or PR) toward which the process converges over time. The goal state or baseline level represents the average level across the task. Second, it posits oscillations (the natural ebb and flow of emotions and strategies), with greater deviation away from the goal state in either direction (above or below the baseline) producing a stronger tendency to revert to the goal state. For example, when a spring is extended or compressed, it exerts a pull or push back toward its natural resting state. In an analogous manner, when fear is provoked (e.g., by a novel person) there is a tendency to return to equilibrium; the greater the return strength, the faster the return to homeostasis. Importantly, some levels of oscillations are hypothesized to persist for a period of time following an initial shock that pushes the system away from homeostasis, such as the appearance of a stranger, even in the absence of new shocks. This model tests our expectation that PR and EP comprise self-sustaining ebbs and flows that arise as part of their intrinsic dynamics (Chow, Ram et al., 2005). This is in contrast to alternative models for emotions such as the Orstein-Uhlenbeck model (e.g., Oravecz, Tuerlinckx, & Vandekerckhove, 2011).

Third, the model may be specified so the system can show reductions in the amplitude of oscillations during a task as it settles into homeostasis. The greater the deviations from homeostasis in a specified amount of time (i.e. higher velocity or rate of change), the more the system attempts to decelerate (slows down or has progressively smaller deviations). For example, in the presence of friction, an oscillating spring will tend to slow down or “damp” toward its equilibrium point. Such damping occurs intrinsically in the absence of other extrinsic forces. Similarly, a fearful child’s progressively smaller amplitudes of bouts of fear to settle into a calm baseline may be conceptualized as damping. As shown in Figure 2, the red spring (PR box) hangs in an extended manner at the outset (left side of graph). The red line from the box indicates how PR fluctuates and damps over time as the spring pulls back towards its natural resting state, eventually settling at its baseline level (right side of graph).

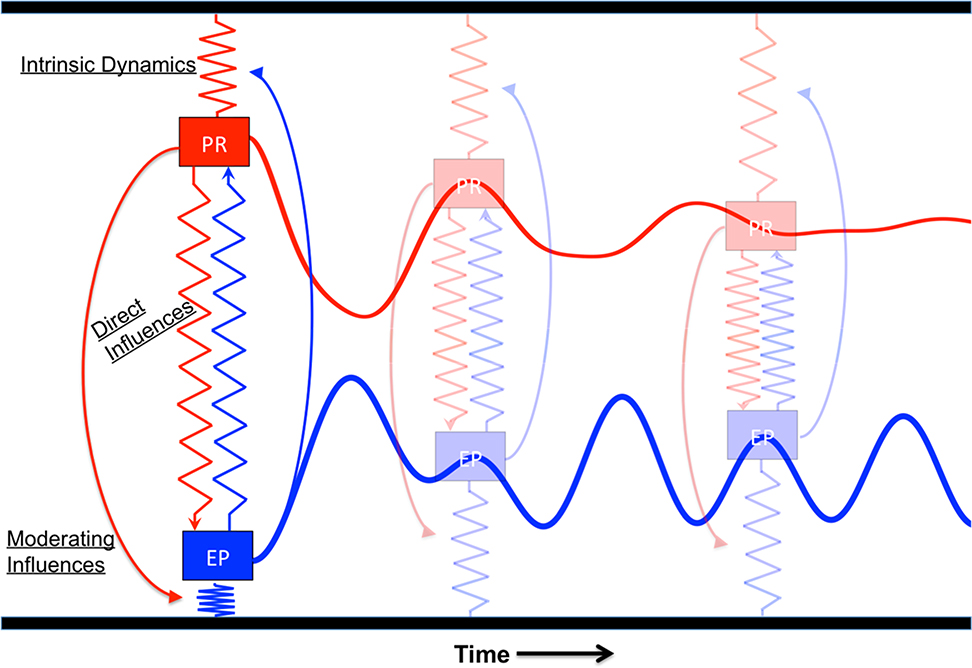

Figure 2.

Following the physics analogy, PR and EP are illustrated as masses (square boxes) on springs (sawtooth lines). Intrinsic dynamics: baseline, return strength, and damping unfold over time in accordance with the characteristics of outer springs. Bidirectional coupling: direct influences unfold over time in accordance with the characteristics of the inner springs; and moderating influences depicted by the arced arrows connecting the PR and EP masses to the outer springs. The resulting nonlinear trajectories of PR and EP across the course of a task are depicted by the red and blue lines.

Our conceptualization of fear self-regulation also invokes an interplay between PR and EP. That is, we focus on two damped oscillators – PR and EP, respectively – with their own intrinsic dynamics that can also influence each other through bidirectional coupling. Moreover, both direct and moderating influences are built into the model. Direct influences are akin to the main effect of an independent variable in a multiple regression model. Here, these involve how the level of and velocity in EP influence acceleration/deceleration in PR at a child’s average level of PR (i.e., when PR is at 0 or its equilibrium position, at which its level and velocity are both 0). EP’s location and velocity may contribute extrinsic push and extrinsic damping on PR, respectively. For example, an extrinsic push would be the direct influence of EP on turning rising fear back toward baseline, and extrinsic damping would be the direct influence of EP on reducing the amplitude of fear bouts. Similarly, PR could exert extrinsic push and extrinsic damping on EP. For instance, fear may have a direct influence on EP bout length, when EP turns around toward equilibrium. Fear may directly influence EP intensity by being directly related to its damping. In Figure 2, these extrinsic forces are represented by blue and red springs directly connecting PR and EP boxes. When one box moves, these connections govern if and how its movement invokes movement in the other box. If the springs are strong, EP and PR movements are tightly coupled, but if they are weak, EP and PR may have little direct effect on one another.

In contrast, moderating influences portray how the effects of extrinsic push and damping depend on the current level and velocity of the process when it is not at resting state. EP level (strategy use) may influence the intrinsic dynamics of PR (fearfulness): specifically, we expect that under high EP levels (while using strategies), children’s fear bouts will shorten as they are pulled more quickly toward equilibrium (higher return strength) and will display larger reductions in intensity (damping). Here, the engagement of EP does not restore PR to equilibrium directly, but rather creates space for PR to bring itself back to homeostasis; that is, EP facilitates PR’s intrinsic regulation. Similarly, PR may moderate EP’s intrinsic dynamics, such that at high levels of fear (PR), children’s strategies deployment lengthens and/or intensifies. That is, PR may create open space that allows amplification, rather than damping, of EP. In Figure 2, these moderating influences are represented by the arced arrows connecting the PR and EP boxes to the intrinsic dynamics of the springs when the two boxes are not at equilibrium. When one box moves, its movements may alter the strength of the other box’s spring, which governs its intrinsic dynamics. In sum, a pair of coupled differential equations can be used to describe the intrinsic dynamics of children’s PR and EP during a fear inducing task, and to study the direct and moderating influence each process has on the other.

Current Study: Developmental Changes in Fear-Regulation Dynamics

The coupled damped oscillator model quantifies three aspects of self-regulation: intrinsic dynamics (baseline, return strength, damping), and bidirectional couplings that are either direct or moderating influences. We apply it to micro-coded longitudinal data involving children’s PR and EP, at ages 2 and 5 years, during a stranger task known to elicit fear/hesitation. In this way we articulate and examine developmental changes in fear self-regulation dynamics. Working from Kopp’s (1982) developmental framework, we hypothesize how the three specific aspects of self-regulation dynamics change during early childhood. However, given this novel approach, we regard the work as a discovery phase that can contribute to formulating new hypotheses about the development of self-regulation. It is not exploratory in that we do articulate and test implicit assumptions in the literature. At the same time, without explicit theory, the tests of hypotheses are also not strictly confirmatory.

Intrinsic dynamics.

We expect age-related change in all three intrinsic dynamics of PR and EP. Following evidence that self-regulation improves with age, we expect 5-year-olds will display less fear and hesitation to the stranger relative to their 2-year-old behavior. That is, the tendency to exhibit PR becomes less potent with age. For PR intrinsic dynamics, we expect that (H1a) PR baseline level to decrease, and PR return strength and damping to increase from Age 2 years to Age 5 years. In terms of EP, we expect it to increase and become more efficient with age, in terms of both ability to deploy and potency of action. That is, with more efficient deployment, we expect EP to kick in faster and be used more briefly to accomplish the same regulatory effects at the older age. Thus, for EP intrinsic dynamics we expect that (H1b) EP baseline level, return strength, and damping to increase (i.e., greater efficiency) from Age 2 years to Age 5 years.

Bidirectional coupling: Direct Influences.

We conceptualize self-regulation in terms of the relations between PR and EP as captured by coupling parameters. For the direct influence of EP on PR, we expect self-regulation to become more effective with age. Thus, we expect EP to push and damp PR with greater force at older ages regardless of PR current level (H2a). Similarly, we expect PR to push and damp EP with less force at older ages regardless of EP’s current level (H2b). That is, the direct force with which PR pushes and damps EP will decrease from Age 2 to Age 5 years.

Bidirectional coupling: Moderating Influences.

We also expect the facilitative role of EP to increase with age and the interference of PR to decrease with age. Specifically, we expect an increase from Age 2 to Age 5 in the moderating influence of EP level on PR return strength and damping (H3a). Likewise, we expect (H3b) a decrease from Age 2 to Age 5 in the moderating influence of PR level on EP return strength and damping. Age-related gains in efficiency would involve PR interfering less with EP at Age 5.

Method

Data are drawn from a longitudinal study of temperament and socioemotional development during early childhood (Buss, 2011). More extensive information about the design, participants, variables, and assessment procedures can be found in Buss et al. (2013). Select details relevant to the present analysis are given below.

Participants

Behavioral observations were conducted with 112 children in lab visits at ages 2 years (M = 2.01, SD =.13) and 5 years (M = 5.88, SD =.33). Children and primary caregivers (~91% mothers, hereafter referred to as mothers) were recruited from a Midwestern city and surrounding rural county. The sample generally consisted of middle-class (M Hollingshead index = 48.85; SD = 10.55; range = [17, 66]), Caucasian (91.9%), married (>98%) families. Observational data were available for 111 children at age 2 (63 boys) and 75 children (42 boys) at age 5. Children with data at both waves did not differ on any study or demographic variable from those who only participated at wave 1 (ts < 0.37, ps > .71, ts < 1.49, ps > .14, respectively), except for race, (χ2(4, N=112)=11.21, p=.02). All four African American participants (3.5% of the sample) did not have data at wave 2.

Novel Task (Procedure)

At each age, children and their mothers visited the laboratory and completed a series of tasks designed to elicit particular types of behavior (Buss, 2011). Here we analyze data from two parallel stranger tasks designed to elicit fear. In brief, at age 2 years, children (accompanied by their mothers) met The Clown. The child and mother were approached by a female research assistant wearing a clown outfit with wig and nose, but no make-up, introducing herself as Floppy the Clown. She rummaged through a large bag to find toys, periodically asking the child to join her. For 1 minute each, the clown played with beach balls, bubbles, and musical instruments. After the first 2 minutes, she said it was hot in the room and removed her wig and nose. After 3 minutes she ask the child to help clean up the toys, gathered them with or without help, and left. Total task time was approximately 4.5 minutes. At age 5 years, children completed the same task, this time being introduced to The Lion.

At age 5, the child was alone in the room (without mother) when a female research assistant wearing a lion costume and mask entered the room, introducing herself as Leo the Lion. She rummaged through a large bag to find toys, periodically inviting the child to join her. For 1 minute each, she danced a “chicken dance,” then tossed a “hot potato” back and forth, and then played “Simon Says.” After 3 minutes the lion asked for help cleaning up the toys, gathered them with or without help, and left. Total task time was approximately 4.5 minutes. The two tasks are treated as conceptually and empirically equivalent.

Measures

Video records of children’s emotions and behaviors were micro-coded on a second-by-second basis. Facial coding was done using the AFFEX system, which reliably differentiates emotions based on three facial regions (Izard, Dougherty, & Hembree, 1983). Coders were considered accurate once they reached a minimum of 90% agreement on each behavior. Inter-coder reliability, calculated as percent agreement on 15% of cases for each episode, were 83% to 100% for clown, and 89% to 100% for lion (see Table S1 for each code’s reliability). From the resulting multivariate time-series data, select variables were used to form composite indices of children’s PR (i.e., wariness and hesitation) and EP (i.e., strategies).

Prepotent Response (PR).

PR was defined by five behaviors indicating hesitation, fear, and withdrawal (Buss, 2011). To increase PR variability in line with previous research (e.g., Pfeifer, Goldsmith, Davidson, & Rickman, 2002), we created a composite that captured a broad range of possible PR-related behaviors. Intensity of children’s facial expressions of fear were coded (0–3) when brows were straight and raised, or tense; eyes were open wide; and mouth open with corners pulled back. Bodily expressions of fear were indicated (0–3) when play was diminished, children froze or decreased activity suddenly, and/or when muscles appeared tensed or trembling. Freezing behavior was also scored (0–1) when children remained still or rigid for 2 or more seconds. This was done by scoring the total time the child displayed the behaviors. For example, if a child froze for 3 seconds, he/she received three consecutive freezing scores of 1. Facial expressions of sadness were coded (0–3) when inner corners of brows were raised and outer corners lowered; eyes were narrowed or squinted and cheeks were raised; corners of mouth were pulled down and out; mouth was open or closed and upper lip often protrudes at the center. Bodily expressions of sadness were coded (0–3) when the child displayed a slump of shoulders or slight drop of head. The intensities of these five behaviors were summed to obtain a composite score indicting the strength of the child’s PR at each second of the task.

Executive Processes (EP).

EP was defined by behaviors that indicated overcoming initial hesitation and using strategies. Fidgeting/self-stimulation was coded (0 ‘absent’ or 1 ‘present’) for tapping or wiggling feet and fingers, sucking on thumb, twirling hair, or rocking back and forth. Gaze aversion was coded (0–1) when the child looked away from the stranger for less than 2 seconds, and Distraction was coded (0–1) when the child focused attention away for more than 2 seconds. Proximity to the novel character (i.e. clown/lion) was rated by distance, i.e. coded (0) when the child was away from the stranger (> 2 feet), within arms length of the stranger (1), or touching the stranger (2). Engaged in activity was scored (0–1) when the child actively played with the toys. Controlling the situation was scored (0–1) when the child attempted to move a stimulus, control the stimulus’ natural movement (for example, forcing something to stay still), or play with a toy after the clown/lion initiated play with a new toy. The ratings for these five behaviors were summed to obtain a composite EP intensity score for each second of the task.

Age.

Age of the child was coded as a binary variable that indicated whether the PR and EP time-series were obtained at the Age 2 years (=0) or Age 5 years (=1) visit.

Data Preparation

Horizontal aggregation.

The second-by-second behavioral coding procedures produce time-series that chronicle changes in child behavior across the 4.5-minute tasks. However, the binary and ordinal nature of the codes do not inherently provide the smooth, continuous trajectories described by differential equations. We therefore aggregate PR and EP variables in 5-second epochs, which allows for emergence and co-occurrence of PR and EP behaviors, as has been done in prior research on fear regulation (Buss & Goldsmith, 1998; Thomas & Martin, 1976), and which captures intermediate – neither fleeting nor long-term – levels of behavior. Thus, the approximately 270 seconds of PR and EP composites were averaged into 5-second segments to obtain epoch-level time-series, yielding approximately 54 occasions that were relatively smooth and deemed of sufficient length for analysis. Figure 1 portrays the time-series of one child at Ages 2 and 5. As can be seen, PR (red) and EP (blue) fluctuate throughout the task and differently at the two ages. In this way, we identify and model epoch-to-epoch changes and accelerations/decelerations and how they change with age.

Calculation of Derivatives.

The epoch-level PR and EP time-series were recast as an ensemble of derivatives, the relations among which describe regulatory dynamics. Specifically, derivatives indicating, for each individual i, the location of PR and EP at each epoch t, (0th derivative; PRita, EPita), rate of change at each epoch (1st derivative; dPR/dtita, dEP/dtita), and rate of acceleration at each epoch (2nd derivative, d2PR/dt2ita, d2EP/dt2ita). Derivatives were calculated using the Generalized Local Linear Approximation (GLLA; Boker, Deboeck, Edler, & Keel, 2010) procedure, with smoothing parameter τ = 1 (calculations made every epoch) and embedding parameter D = 4 (calculations made using a 4-epoch window; see recommendations in Boker et al., 2010). In brief, the GLLA extracts the time dependencies in replicated windows of time series (structured in a time-delay embedded data matrix with window length D) via polynomials and uses these approximations to derive least squares estimates of the 0th, 1st, and 2nd derivatives. The script used to estimate the derivatives can be found in the supplemental information of this article.

Data Analysis

The relations among the epoch-level time-series of the PR and EP derivatives were then modeled using a bivariate system of differential equations within a multilevel modeling framework that accommodated the nested nature of the data (54 epochs nested within 112 persons) and allowed for description and testing of age differences in the intrinsic dynamics and bidirectional coupling embedded in the interplay of children’s PR and EP during novel situations.

Intrinsic dynamics (+ age differences).

First, a model was constructed to articulate PR and EP intrinsic dynamics, and test for age differences in these dynamics. Specifically, the relations among the PR derivatives were modeled as

| (1.1) |

where i indexes child, t indexes epoch, and a indexes age; and the relations among the EP derivatives were modeled as

| (1.2) |

where in both equations,

and

with (baselinePRi and baselineERi) indicating person-specific baseline levels of PR and EP at Age 2 and ΔbaselinePRi and ΔbaselineERi indicating the age-related change in baseline/homeostasis levels to Age 5. In Equations 1.1 and 1.2, the accelerations/decelerations of PR or EP at each epoch t, and , are modeled as a function of the corresponding locations (0th derivative = PR or EP), rates of change (1st derivative = or ), and “dynamic errors” or residual acceleration ( or ). The parameters ηPR0 and ηER0 describe the intrinsic return strength at Age 2. For the processes with oscillations (rather than alternative dynamics such as exponential growth), ηPR0 and ηER0 are positive. In turn, ηPR1 and ηER1 describe the age-related change in the intrinsic return strength for PR and EP, respectively. As outlined in the introduction, our expectation is that will be positive, indicating greater PR and EP return strength at Age 5. Finally, ζPR0 and ζER0 describe the extent of intrinsic damping of PR and EP, respectively, at age 2. We expect ζPR0 and ζER0 to be positive, indicating that the system eventually converges to baseline. The parameters ζPR1 and ζER1 capture the age-related change in damping of PR and EP. Our expectation is that ζPR1 will be positive, indicating that PR damps faster at Age 5, and that ζER1 will be near zero or positive, indicating that EP shows little changes or slight increase in damping at Age 5.

Bidirectional coupling (+ age differences).

Equations 1.1 and 1.2 articulate only the intrinsic dynamics of PR and EP (and the age differences therein), without allowing the possibility for EP to influence the acceleration/deceleration of PR or, vice versa, for PR to influence the acceleration/deceleration of EP. As described earlier, we assume that EP and PR influence each other in two ways: each process has a (extrinsic) direct influence on acceleration/deceleration of the other process (e.g., higher levels of EP are associated with PR deceleration); and, each process has a moderating influence on the intrinsic dynamics of the other process (e.g., high levels of EP facilitate intrinsic damping of PR). Allowing for these two types of coupling, the model was expanded to include bidirectional influences at ages 2 and 5. Specifically, Equation 1.1 was expanded to

| (2.1) |

and Equation 1.2 was expanded to

| (2.2) |

In Equations 2.1 and 2.2, parameters describing intrinsic dynamics match those from Equations 1.1 and 1.2, and two additional sets of parameters summarize bidirectional coupling. Parameters βPR0 and βER0 capture the direct extrinsic push of PR on EP and of EP on PR at Age 2, and βPR1 and βER1 describe the age-related change in direct extrinsic pushes for PR and EP, respectively. Parameters δPR0 and βER0 capture the extrinsic damping of PR on EP and of EP on PR at Age 2, and δPR1 and δER1 characterize age-related changes in the strengths of the direct extrinsic damping. The last set of parameters capture moderating effects of one process one the other processes’ intrinsic dynamics. Specifically, πPR0 and πER0 capture how intrinsic return strengths of PR and EP are contingent on the level of the other process. In turn, age-related changes in the extent of moderation are captured by πPR1 and πER1 parameters. Similarly, ξPR0 and ξER0 capture how intrinsic damping of PR and EP are moderated by the level of the other process, with the corresponding age-related changes in extent of moderation captured by ξPR1 and ξER1. The full list of parameters and short explanations are embedded in Table 2.

Table 2.

Results from multilevel model examining age differences in self-regulation dynamics.

| Final Model | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Parameters | Estimates | 95%CI | Parameter Label |

| Fixed effects for PR (Eq. 2.1) | |||

| Intrinsic Dynamics for PR | |||

| baselinePR | 0.45 * | [0.26,0.63] | Baseline |

| ΔbaselinePR | −0.32 * | [−0.51,−0.12] | Age Δ in baseline |

| ηPR | 0.26 * | [0.25,0.28] | Return strength |

| ηPR1 | 0.05 * | [0.02,0.07] | Age Δ in return strength |

| ζPR | 0.13 * | [0.09,0.16] | Damping |

| ζPR1 | 0.06 * | [0.00, 0.13] | Age Δ in damping |

| Extrinsic Direct Influences for PR | |||

| βPR | 0.01 | [0.00,0.02] | Extrinsic push |

| βPR1 | 0.01 | [−0.01,0.03] | Age Δ in extrinsic push |

| δPR | 0.00 | [−0.02,0.02] | Extrinsic damping |

| δPR1 | 0.00 | [−0.04,0.04] | Age Δ in extrinsic damping |

| Extrinsic Indirect Influences for PR | |||

| πPR | −0.20 * | [−0.21,−0.18] | Moderated return strength |

| πPR1 | −0.11 * | [−0.15,−0.08] | Age Δ in moderated return strength |

| ξPR | 0.12 * | [0.08,0.17] | Moderated damping |

| ξPR1 | −0.10 | [−0.21,0.02] | Age Δ in moderated damping |

| Fixed effects for EP (Eq. 2.2) | |||

| Intrinsic Dynamics for EP | |||

| baselineEP | 1.14 * | [1.03,1.25] | Baseline |

| ΔbaselineEP | −0.10 | [−0.23,0.04] | Age Δ in baseline |

| ηEP | 0.25 * | [0.24,0.26] | Return strength |

| ηEP1 | 0.21 * | [0.19,0.24] | Age Δ in return strength |

| ζEP | −0.01 | [−0.04,0.02] | Damping |

| ζEP1 | 0.01 | [−0.05,0.06] | Age Δ in damping |

| Extrinsic Direct Influences for EP | |||

| βEP | 0.05 * | [0.03,0.06] | Extrinsic push |

| βEP1 | 0.06 * | [0.03,0.09] | Age Δ in extrinsic push |

| δEP | 0.01 | [−0.03,0.05] | Extrinsic damping |

| δEP1 | −0.03 | [−0.11,0.04] | Age Δ in extrinsic damping |

| Extrinsic Indirect Influences for EP | |||

| πEP | −0.04 * | [−0.06,−0.02] | Moderated return strength |

| πEP1 | 0.11 * | [0.06,0.16] | Age Δ in moderated return strength |

| ξEP | −0.06 * | [−0.12,0.00] | Moderated damping |

| ξEP1 | 0.11 | [−0.03,0.25] | Age Δ in moderated damping |

| Random effects | |||

| σBaselinePR | 0.99 | [0.91,1.09] | Residual variance/covariance unaccounted for by Age |

| σΔBaselinePR | 1.01 | [0.94,1.07] | |

| σBaselineEP | 0.58 | [0.49,0.70] | |

| σΔBaselineEP | 0.66 | [0.52,0.83] | |

| r(φPR, φEP ) | −0.45 | [−0.56,−0.32] | |

| r(φPR, φΔPR ) | −0.97 | [−0.98,−0.95] | |

| r(φPR, φΔEP ) | 0.30 | [0.15,0.44] | |

| r(φEP, φΔPR ) | 0.45 | [0.31,0.56] | |

| r(φEP, φΔEP ) | −0.92 | [−0.95,−0.86] | |

| r(φΔPR, φΔEP ) | −0.34 | [−0.47,−0.19] | |

| Model Fit | |||

| AIC | 4012.01 | ||

| BIC | 4336.44 | ||

| LogLikelihood | −1965.05 | ||

Note: N = 112, PR = Prepotent Response, EP = Executive Process, CI = 95% confidence interval, AIC = Akaike Information Criteria, BIC = Bayes Information Criteria

= p < .05

To find the best model, first a simpler model was fitted to the data (i.e., bivariate models with no bidirectional coupling, as in Equations 1.1 and 1.2; Table S2 & Figure S1) and then a more complex model (bivariate model with direct and moderating influences) of Equations 2.1 and 2.2. Models were estimated using the nlme package (Pinheiro, Bates, DebRoy, Sarkar, & R Core Team, 2016) in R (R Development Core Team, 2008), with incomplete data treated as missing at random and with maximum-likelihood estimation. At each stage of the fitting a variety of random effects structures were tested, with the different configurations having little influence on the model parameters or interpretations (i.e., no changes in significant effects). The final structure included random effects for the baseline and age-differences in baseline parameters. As expected, the final, complete, model had the best fit (i.e., based on AIC, BIC, and log-likelihood). Thus, for parsimony, we present and interpret only the final model. Statistical significance of the parameters was evaluated using standard procedures (i.e., α = .05), with the pattern of findings being identical when using conservative or liberal interpretation and calculation of the degrees of freedom (i.e., number of persons vs. number of observations) in the multilevel model (see discussion in Bolger & Laurenceau, 2013). Notably, results were robust to changes in the random effects structure, removal of potential non-conformers (e.g., removal of children who never displayed fear in the putatively fear-inducing task; Table S3 & Figure S2), and treatment of missing data (e.g., similar pattern of findings when using only complete data cases; Table S4 & Figure S3).

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Table 1 contains PR and EP descriptive statistics at ages 2 and 5. Table 1 shows that the overall PR level was lower at age 5 than age 2 (MAge5=0.11, SD=0.17; MAge2=0.39, SD= 0.96; t(73)=2.82, p=.006, d=0.33). The overall EP level did not change with age (MAge5=1.11, SD=0.56; MAge2=1.03, SD=0.23; t(73)=1.31, p=.193, d=0.15). The within-person PR-EP correlation, which is sometimes interpreted as indicating bidirectional coupling was, on average, r=−.26 at Age 2 and r=−.16 at Age 5. In line with previous studies (e.g., Buss & Goldsmith, 1998; Rothbart et al., 1992), the mean PR and EP levels are both relatively low; averaging across the entire task time combines segments in which where PR and EP are prominent with those in which PR and/or EP are absent (see Figure 1). PR mostly occurs at the beginning of the task and diminishes over time. The time-related changes in PR and EP are not captured by means, but can be examined using the dynamic system models.

Table 1.

Sample Descriptives for Prepotent Responses (PR) and Executive Processes (EP) at Ages 2 and 5.

| Variable | M | SD | 1. EPAge2 | 2. PRAge2 | 3. EPAge5 | 4. PRAge5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. EP Age 2 | 1.11 | 0.56 | -- |

−.26 [−.66, .27] |

-- | -- |

| 2. PR Age 2 | 0.39 | 0.96 | −.45** | -- | -- | -- |

| [−.58, −.28] | ||||||

| 3. EP age 5 | 1.03 | 0.23 | .00 | −.06 | -- | −.16 |

| [−.23, .23] | [−.29, .17] | [−.64, .38] | ||||

| 4. PR Age 5 | 0.11 | 0.17 | .08 | .02 | .01 | -- |

| [−.16, .30] | [−.21, .24] | [−.22, .24] |

Note. N = 112 Age 2, 75 Age 5

indicates p < .05

indicates p < .01.

M and SD indicate sample-level mean and standard deviation, respectively. Lower triangle contains sample-level correlations between mean PR and EP levels [with 95% confidence interval in brackets]. Upper triangle contains average within-person correlation [with sample range in brackets].

Dynamic Model

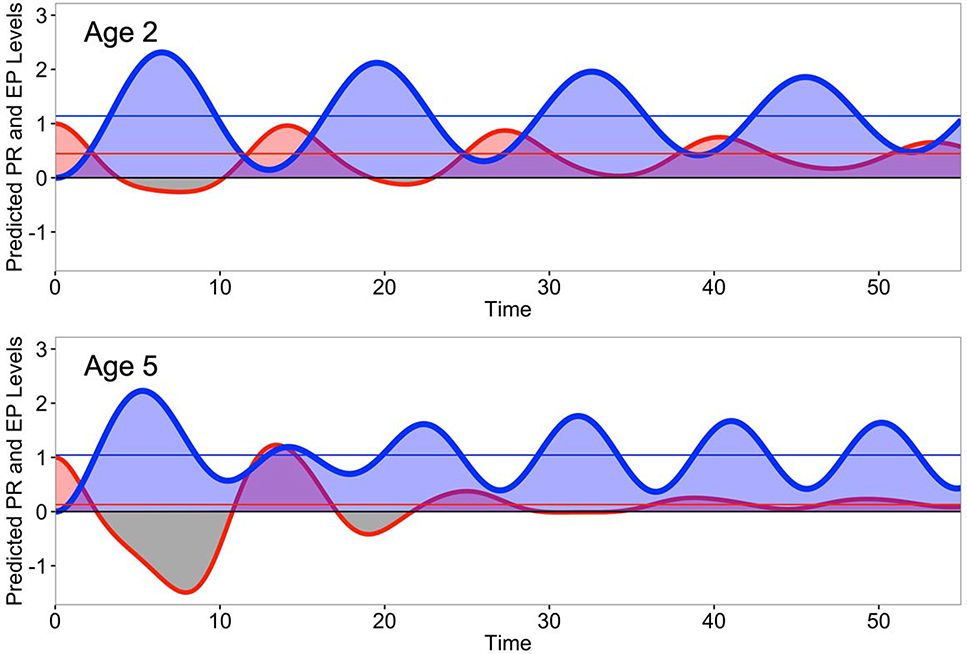

More detailed age differences in PR and EP intrinsic dynamics and their bidirectional coupling were articulated by the coupled damped linear oscillator model (Equations 2.1 and 2.2). Results are shown in Table 2, with corresponding visual depiction of the model-implied trajectories in Figure 3. We describe each set of parameters in turn.

Figure 3.

The predicted trajectories of the prepotent response (red) and executive processes (blue) based on the estimated parameters from the final model for age 2 (upper panel) and age 5 (lower panel), with starting values for PR and dPR/dt of 1.00 and −0.01, respectively, and for EP and dEP/dt of 0.00 and −0.01, respectively.

Intrinsic dynamics (+ age differences).

The first set of parameters describes three aspects of the intrinsic dynamics of PR (baselinePRi, ηPR0, ζPR0) and EP (baselineERi, ηER0, ζPR0), and the age differences therein.

Baselines.

As expected (H1a), PR baseline level was significantly lower at Age 2 (baselinePR=0.45, p<.001) than Age 5, (ΔbaselinePR=−0.32, p<.001), as seen in baseline levels in Figure 3 as thin red horizontal lines. Contrary to hypothesis H1b, EP baseline level at Age 2 (baselinePR=1.14, p<.001) was not significantly lower than at Age 5 (ΔbaselineEP=−0.10, p=.151). The thin blue lines in Figure 3 show the similarity of baseline EP across age.

Intrinsic Return Strength (η).

At Age 2, there was significant intrinsic pull back toward homeostasis/baseline in both PR and EP (ηPR0=0.26, p<.001; ηER0=0.25, p<.001). As hypothesized (H1a and H1b, respectively), the intrinsic return strengths of PR and EP were stronger at age 5 than at age 2 (ηPR1=0.05, p<.001; ηEP1=0.21, p<.001). Figure 3 depicts these differences through the increased frequency of (i.e. more rapid) oscillations at Age 5 for both PR (red) and EP (blue) lines.

Damping (ζ).

Also as expected based on H1a, age 2 showed significant damping for PR(ζPR1=0.13, p<.001), which strengthened at age 5 (ζER1=0.06, p=.038). The age-related change in intrinsic damping of PR is in part reflected in Figure 3 that shows age differences in the timing of convergence to baseline levels. At Age 5 the oscillations extinguish almost entirely by Time 30 (lower panel), whereas the oscillations persist through Time 50 at Age 2 (upper panel). Contrary to H1b, however, EP did not show evidence of damping at Age 2(ζER0=−0.01, p=.423), nor was there significant change with age (ζER1=0.01, p=.810). Consequently, the EP amplitude (height) of the oscillations remains unchanged throughout the task and across age.

Bidirectional coupling (+ age differences).

The second set of parameters describes the direct and moderating influences of PR on EP and EP on PR, and the age differences therein.

Direct influences (β,δ).

Contrary to expectations (H2a), there was no evidence of an extrinsic push from EP to PR (βPR0=0.01, p=.134), or evidence of an age difference in the strength of the push (βPR1=0.01, p=.150). Partial support was found for H2b in that Age 2 showed a statistically significant PR to EP push toward baseline (βEP0=0.05, p<.001), but this PR to EP direct influence actually strengthened as opposed to weakened with age (βEP1=0.06, p<.001). Further divergence from hypotheses H2a and H2b was found in that there was no evidence that EP provided any extrinsic damping of PR, (δPR0=0.00; p=.912); no evidence that PR provided any extrinsic damping of EP, (δER0=0.01; p=.549); and no evidence of age differences in extrinsic damping, (δPR1=0.00, p=.892 and δER1=−0.03, p=.399). Generally, these findings suggest that there is limited direct influence between PR and EP, and only where PR provided an extrinsic push on EP.

Moderating influences (π, ξ).

The interactive influences between PR and EP were more salient when considered as moderating influences, with the intrinsic dynamics of PR and EP each moderated by the other process.

EP moderating PR dynamics.

At Age 2 EP moderated the intrinsic return strength of PR (πPR0=−0.20, p<.001), such that PR exhibited weaker return strength when EP was above-baseline. Contrary to expectations (H3a), the moderation became stronger with age (πPR1=−0.11, p<.001). That is, the “interaction” between PR and EP actually led PR to take longer to revert to baseline when EP was high (above-baseline) at Age 5 than at Age 2. In addition, at Age 2, EP moderated the intrinsic damping of PR (ξPR0=0.12, p<.001), with high levels of EP facilitating intrinsic damping of PR. However, also contrary to hypothesis H3a, the extent of moderation did not change with age (ξPR1=−0.10, p=.097).

PR moderating EP dynamics.

PR was found to moderate the intrinsic return strength of EP (πEP0=−0.04, p<.001), by weakening the return strength of EP at high levels of PR. Confirming the expected developmental change (H3b), the direction of moderation was reversed at Age 5, such that high levels of PR were coupled with enhanced return strength of EP (πEP1=0.11, p<.001). Thus, as expected, older children tended to deploy EP for briefer periods of time (i.e. shorter EP bouts as indexed by a higher return strength), especially at extreme levels of PR. In complement, PR also moderated the intrinsic damping in EP, such that EP tended to amplify or become “evoked” at high levels of PR (ξEP0=−0.06, p=.043). Contrary to expectations (H3b), the PR moderation of intrinsic damping in EP did not change significantly with age (ξEP1=0.11, p=.112).

In sum, children at Age 5 appeared to be more efficient (i.e. quicker) than children at Age 2 in deploying EP-related strategies (as reflected in the PR→EP moderated influence on the latter’s return strength), but they did not do so with higher potency/effectiveness (as reflected in the lack of age difference in the PR→EP moderated influence on the latter’s amplification at high levels of PR). The age differences in the direct and moderating influences is seen most prominently in the first half of the prototypical trajectories shown in Figure 3, with substantial shifts in the interplay of EP and PR between the upper (Age 2) and lower (Age 5) panels around Time 12. Of note, the reason the predicted trajectories go beyond the range of observed scores (i.e., below zero) is an artifact of the divergence between the observational coding scheme (which is a composite of binary and ordinal variables) and the model (which assumes that the latent underlying psychological process is continuous in nature). Given that the psychological processes (e.g., PR) occur even in the absence of observable behavior (e.g., expression in physiology but not in overt behavior), the predicted trajectories provide a picture of the predicted (latent) psychological process.

Discussion

The present study is the first to investigate age-related changes in the dynamics of fear-related regulation between toddlerhood and childhood. Specifically, children’s self-regulation of fear was modeled using coupled damped linear oscillators that allowed for precise articulation of three aspects of self-regulation dynamics: the intrinsic dynamics (baseline, return strength, damping) of each process (i.e., PR and EP); the direct influences of one process on the other; and the moderating influences each process has on the intrinsic dynamics of the other process. These models made it possible to examine for the first time, if PR simply decays more quickly with age regardless of the use of strategies, whether EP-related strategies get deployed more readily with age, or whether PR is more effectively modulated by the use of EP with age. Overall, we found age-related changes consistent with developmental theory (Kopp, 1982) in intrinsic dynamics and moderating influences. However, not all the dynamics manifested or changed as expected. Instead the results of the dynamic modeling approach reveal nuances to the development of self-regulation of fear in early childhood, including the limitations of young children’s fear regulation. Beyond the specific results, the study highlights how the application of dynamic systems modeling to multiple time-scale data can contribute to a refined description and understanding of the development of self-regulation.

Generally, we found that children at Age 5 appeared to show more efficient fear-related regulation than at Age 2. Results for the intrinsic dynamics revealed that the PR baseline, or overall average during the task, decreased with age, and both the PR return strength and the PR damping increased with age. Namely, when children’s fear and hesitation were provoked, they were quicker to return to baseline at Age 5 compared to Age 2. This is in line with the proposition that as self-regulation develops (Kopp, 1982), children’s PR decreases and can be managed more quickly and efficiently. For EP, the only significant age-related change in intrinsic dynamics was an increase in the EP return strength. This supports the assertion that older children are more efficient at deploying putative regulatory strategies. That is, when EP was evoked, it reverted to baseline more quickly at Age 5 than at Age 2. This was further supported by the moderating influences, in which at Age 2, EP’s return strength was related to the level of PR, with high levels of PR weakening the return strength of EP. However, as expected this effect was reversed at Age 5. In this way, older children appeared to be more efficient (i.e. quicker) in deploying EP.

We did not, however, find support for increased efficiency of self-regulation in terms of potency. EP did not show intrinsic damping during the task at both ages, implying that, at both ages, EP “remains vigilant” throughout the task and does not diminish back into equilibrium like PR. This may reflect the fact that once the child overcomes their initial inhibition towards novelty and approaches or engages with the novel stranger, they maintain their involvement with the stranger. Supporting this interpretation, the baseline level of EP did not change with age. Although developmental theory suggests that the number and frequency of EP strategies increases with age, the findings here (which collapse across strategies) suggest that the developmental changes are located in the quickness of deployment rather than in the quantity and/or potency of deployment.

Similarly, in the moderating influences, we did not find age differences in the potency of EP. As expected by developmental theory (Kopp, 1982, 1989), we found that EP facilitated the intrinsic damping of PR. That is, the higher the level of EP, the stronger the reductions in the intensity (intrinsic damping) of PR. But, contrary to expectations, there was no evidence for age-related changes in this parameter. EP facilitated damping of PR in a similar way at both Age 2 and Age 5. In the same vein, we found that PR levels also moderated the intrinsic damping of EP, such that when PR was high, EP was amplified. That is, PR evokes EP to down-regulate PR, both at Age 2 and at Age 5. These findings suggest that in this context, these forms of effective self-regulation are acquired early, and once acquired may not change with age. This is in line with studies examining the regulatory effectiveness of specific strategies using contingency analyses in infancy (e.g., Buss & Goldsmith, 1998; Crockenberg & Leerkes, 2004). These studies found that even at younger ages than the current study, some of the infants’ putative regulatory behaviors reduced the intensity of emotion. Although the effectiveness of these strategies may be more evident for anger and short lived during infancy (Buss & Goldsmith, 1998), the prior studies and the current findings suggest that some aspects of effective self-regulation are present from early development and may remain relatively stable across development. Notably, these prior studies discuss the associations in terms of direct influences, while here we have located them as moderating influences.

The distinction between direct and moderating influences has not been previously articulated. Given that the model allows for such distinction, theoretically, it would seem more likely that EP influences PR indirectly, by changing the context rather than directly changing PR levels. For instance, when a distressed child uses a strategy, the strategy does not directly cause the reductions in distress. Rather the strategy (e.g., distraction) changes the psychological context and that allows distress to decrease. In line with this, there were no significant direct influences where EP was providing an extrinsic push or extrinsic damping on PR. The implication is that EP (putative regulatory strategies) do not operate directly on PR, but may instead facilitate the more basic intrinsic dynamics that govern return of PR to baseline, as suggested by the moderating influences discussed above. Further support comes from a recent study of 36-month-olds’ regulation of anger, where self-regulation was conceptualized in terms of how levels of one process (EP or PR) moderated the damping or amplification of the opposing process (Cole et al., 2017). More specifically, they found that externalizing behavior was related to more regulatory interference – the use of strategies (EP) displayed increased damping, under high levels of frustration (PR). These results together with the current findings suggest that self-regulation may be best captured, at least in these two contexts (anger and fear), as indirect (moderating) influences between PR and EP rather than direct influence of one process on the other.

The only significant direct influence indicated that PR provided an extrinsic push on EP, contributing to its return to baseline at Age 2, and even more so at Age 5. Also unexpected, this finding highlights an ambiguity and limitation of the damped linear oscillator model. This limitation concerns the reciprocal relation of some of the parameters within the model. While we have interpreted the parameter as indicating the strength with which PR “pushes EP down” to baseline, an equally viable interpretation is that PR “pulls EP up” to baseline. That is, PR evokes EP to down-regulate PR. Mathematically, the parameter governs both these possibilities. Future research should consider a stricter test of the current hypotheses by removing the reciprocal properties of the model (e.g., using a threshold autoregressive model; Tong & Lim, 1980).

Importantly, few studies have examined the influence of PR on EP (e.g., Ekas et al., 2011), and to our knowledge, no study (with the exception of Cole et al., 2017) has examined the effects of PR on EP while taking into account the effects of EP on PR. The current findings on the influence of PR on EP highlight the importance of using models that capture the bidirectional dynamics of self-regulatory process.

Limitations and Outlook

The results from this study should be considered carefully with respect to some specific limitations embedded in the study design and analysis. In addition to issues regarding the homogeneity of the sample (Caucasian, middle-class) and the need for care in generalization to the broader population (see Gatzke-Kopp, 2016), we highlight two specific challenges surrounding measurement invariance in the study of developmental change and dynamic systems modeling of observational data. Study of developmental change requires measurement invariance. In particular, quantification of change requires that the same constructs are measured in the same way at all ages (Widaman, Ferrer, & Conger, 2010). Our study was facilitated by a study design wherein children’s behavior during similar fear-eliciting, novel stranger tasks was observed when the children were Age 2 years and again at Age 5 years. Invoking the principle of measurement invariance, we treated the clown and lion tasks as conceptually and empirically equivalent environments that evoked fear of novelty in the same way. This facilitated the examination of age related-change. However, the two tasks were not identical. In particular, the mother was present in the room at Age 2, a developmental period in which separating the child from the mother might be considered an emotion-eliciting situation on its own, and not at Age 5. Even though mothers were instructed to remain uninvolved in the procedure, it is possible that the mothers’ presence influenced the children’s behaviors in ways that are not accounted for in the current analysis. Given that the presence of mothers may have served a regulatory role (Diener & Mangelsdorf, 1999; Kopp, 1982, 1989), we may be underestimating the extent of age-related change in self-regulation. Future studies should consider further the analytical benefits and costs of including tasks with the exact same “novel” stimuli at multiple ages. Here, we were able to invoke similarity across two visits. More detailed descriptions of the timing and tempo of age-related changes will require many more visits (e.g., every 6 months; see Ram & Grimm, 2015) and contribute an additional layer of complication for task equivalence and measurement invariance.

Although dynamic systems modeling offers a novel and promising approach to the study of the development of self-regulation, implementation with empirical data presents several challenges. For example, although second-by-second micro-coding of behavior and emotion observed during laboratory tasks provides rich multivariate time-series, the behaviors and emotions are typically coded as present or absent (0–1) or using 3 or 4-point ordinal scales (0–3). Differential equation models are designed and are most useful for studying change along a continuous scale. To bridge the gap between the data realities and the ideal analytical scenario we created composite measures of PR and EP by combining scores across several behaviors (vertical aggregation) and “zooming” out to 5-second epochs (horizontal aggregation). While this worked (see also Gottman, Murray, Swanson, Tyson, & Swanson, 2002; Thomas & Martin, 1976), future studies should consider using coding procedures that track behavioral change on continuous scales (e.g., Messinger, Mahoor, Chow, & Cohn, 2009) or using dynamic models with a Poisson measurement function (Durbin & Koopman, 2001). In the “zooming” out process we located a conceptually sound sweet spot that captured behavioral emergence and co-occurrence of PR and EP, but were left fitting a high-complexity model to ~54-occasion (i.e., relatively short) time series. Most certainly, longer time series (and a larger sample) will provide for more precise estimation of the intraindividual dynamics and the interindividual differences therein.

We used a specific differential equation model – a coupled, damped oscillator model – to articulate self-regulation as a process, and examine how that process changed from Age 2 to Age 5. Our selection of this model was driven by a combination of theory and empirical viability. Following prior work (e.g., Boker et al., 2014; Butner et al., 2005, 2007; Chow et al., 2005), we mapped model parameters to specific aspects of self-regulation. However, this is but one of many differential equation models that can be mapped to self-regulatory process. Future studies should consider how other models (e.g., Lotka-Volterra predator-prey models; Lotka, 1925; Volterra, 1926 or Orstein-Uhlenbeck; Oravecz et al., 2011) map to the processes of interest, the structure of task-specific perturbations, and the available measurements.

Conclusion

Despite the importance of self-regulation on socioemotional development, little is known about the specific ways in which self-regulation develops as it has been mostly studied as a static construct. The current study illustrates the precision with which aspects of self-regulation can be articulated by using the time-series of micro-coded data under a dynamic systems modeling framework. As in recent studies (Cole et al., 2017), a next step could utilize this approach to examine if particular aspects of regulation (or dysregulation) are associated with or predictive of behavioral problems. Here, we expanded these models to describe longitudinal changes in self-regulation during a fear-inducing situation. Results suggest that this approach can be used to describe the development of self-regulation in nuanced and theoretically meaningful ways.

Supplementary Material

Research Highlights:

Although it is generally assumed that during early childhood children’s self-regulation repertoire of strategies expands and is deployed more effectively, longitudinal tests of these assumptions are scarce.

By integrating dynamic systems modeling with a multiple time-scale framework we examined (short-term) dynamic relations between children’s prepotent responses and self-regulation strategies and how those dyanmics change developmentally (long-term) between ages 2 and 5 years.

Results revealed age-related changes in self-regulation dynamics, some of which were consistent with developmental theory and some that were not expected.

The findings illustrate the value of dynamic systems models for articulating specific aspects of self-regulation and how they change in nuanced and theoretically meaningful ways across early childhood.

References

- Bakeman R, & Quera V (2011). Sequential analysis and observational methods for the behavioral sciences. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Boker SM, Deboeck PR, Edler C, & Keel PK (2010). Generalized local linear approximation of derivatives from time series. In Chow S-M, Ferrer E, & Hsieh F (Eds.), Statistical methods for modeling human dynamics: An interdisciplinary dialogue (pp. 161–178). New York, NY, US: Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group. [Google Scholar]

- Boker SM, & Laurenceau J-P (2007). Coupled dynamics and mutually adaptive context. Modeling Contextual Effects in Longitudinal Studies, 299–324. [Google Scholar]

- Boker SM, Neale MC, & Klump KL (2014). A Differential Equations Model for the Ovarian Hormone Cycle. In Molenaar PCM, Lerner RM, & Newell KM (Eds.), Handbook of Developmental Systems Theory and Methodology (pp. 369–391). New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Boker SM, & Nesselroade JR (2002). A method for modeling the intrinsic dynamics of intraindividual variability: Recovering the parameters of simulated oscillators in multi-wave panel data. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 37(1), 127–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolger N, & Laurenceau J-P (2013). Intensive Longitudinal Methods: An Introduction to Diary and Experience Sampling Research (1 edition). New York, NY: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brooker RJ, Buss KA, Lemery-Chalfant K, Aksan N, Davidson RJ, & Goldsmith HH (2013). The development of stranger fear in infancy and toddlerhood: normative development, individual differences, antecedents, and outcomes. Developmental Science. 10.1111/desc.12058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buss KA (2011). Which fearful toddlers should we worry about? Context, fear regulation, and anxiety risk. Developmental Psychology, 47(3), 804–819. 10.1037/a0023227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buss KA, & Goldsmith HH (1998). Fear and Anger Regulation in Infancy: Effects on the Temporal Dynamics of Affective Expression. Child Development, 69(2), 359–374. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1998.tb06195.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butner J, Amazeen PG, & Mulvey GM (2005). Multilevel Modeling of Two Cyclical Processes: Extending Differential Structural Equation Modeling to Nonlinear Coupled Systems. Psychological Methods, 10(2), 159–177. 10.1037/1082-989X.10.2.159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butner J, Diamond LM, & Hicks AM (2007). Attachment style and two forms of affect coregulation between romantic partners. Personal Relationships, 14(3), 431–455. [Google Scholar]

- Chow S-M, Ram N, Boker SM, Fujita F, & Clore G (2005). Emotion as a Thermostat: Representing Emotion Regulation Using a Damped Oscillator Model. Emotion, 5(2), 208–225. 10.1037/1528-3542.5.2.208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clauss JA, & Blackford JU (2012). Behavioral Inhibition and Risk for Developing Social Anxiety Disorder: A Meta-Analytic Study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 51(10), 1066–1075.e1. 10.1016/j.jaac.2012.08.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole PM, Bendezú JJ, Ram N, & Chow S-M (2017). Dynamical Systems Modeling of Early Childhood Self-Regulation. Emotion. 10.1037/emo0000268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole PM, Martin SE, & Dennis TA (2004). Emotion Regulation as a Scientific Construct: Methodological Challenges and Directions for Child Development Research. Child Development, 75(2), 317–333. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00673.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole PM, Michel MK, & Teti LO (1994). The development of emotion regulation and dysregulation: A clinical perspective. In Fox NA (Ed.), Monographs of the society for research in child development (Vol. 59, pp. 73–102). Retrieved from http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1540-5834.1994.tb01278.x/full [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole PM, Tan PZ, Hall SE, Zhang Y, Crnic KA, Blair CB, & Li R (2011). Developmental changes in anger expression and attention focus: Learning to wait. Developmental Psychology, 47(4), 1078–1089. 10.1037/a0023813 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crockenberg SC, & Leerkes EM (2004). Infant and Maternal Behaviors Regulate Infant Reactivity to Novelty at 6 Months. Developmental Psychology, 40(6), 1123–1132. 10.1037/0012-1649.40.6.1123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diener ML, & Mangelsdorf SC (1999). Behavioral strategies for emotion regulation in toddlers: associations with maternal involvement and emotional expressions. Infant Behavior and Development, 22(4), 569–583. 10.1016/S0163-6383(00)00012-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Durbin J, & Koopman SJ (2001). Time series analysis by state space methods (Vol. 24). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Durston S, Thomas KM, Yang Y, Ulug AM, Zimmerman RD, & Casey BJ (2002). A neural basis for the development of inhibitory control. Developmental Science, 5(4), F9–F16. 10.1111/1467-7687.00235 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ekas NV, Braungart-Rieker JM, Lickenbrock DM, Zentall SR, & Maxwell SM (2011). Toddler emotion regulation with mothers and fathers: Temporal associations between negative affect and behavioral strategies. Infancy, 16(3), 266–294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gatzke-Kopp LM (2016). Diversity and representation: Key issues for psychophysiological science: Diversity and representation. Psychophysiology, 53(1), 3–13. 10.1111/psyp.12566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottman JM, Murray JD, Swanson C, Tyson R, & Swanson KR (2002). The Mathematics of Marriage: Dynamic Nonlinear Models. Cambridge, Mass: A Bradford Book. [Google Scholar]

- Grolnick WS, Bridges LJ, & Connell JP (1996). Emotion Regulation in Two-Year-Olds: Strategies and Emotional Expression in Four Contexts. Child Development, 67(3), 928–941. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1996.tb01774.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harman C, Rothbart MK, & Posner MI (1997). Distress and attention interactions in early infancy. Motivation and Emotion, 21(1), 27–44. [Google Scholar]

- Helm JL, Sbarra D, & Ferrer E (2012). Assessing cross-partner associations in physiological responses via coupled oscillator models. Emotion, 12(4), 748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodgins MJ, & Lander J (1997). Children’s coping with venipuncture. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 13(5), 274–285. 10.1016/S0885-3924(96)00328-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollenstein T, & Lewis MD (2006). A state space analysis of emotion and flexibility in parent-child interactions. Emotion, 6(4), 656–662. 10.1037/1528-3542.6.4.656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollenstein T, Lichtwarck-Aschoff A, & Potworowski G (2013). A Model of Socioemotional Flexibility at Three Time Scales. Emotion Review, 5(4), 397–405. 10.1177/1754073913484181 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kopp CB (1982). Antecedents of self-regulation: A developmental perspective. Developmental Psychology, 18(2), 199–214. 10.1037/0012-1649.18.2.199 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kopp CB (1989). Regulation of distress and negative emotions: A developmental view. Developmental Psychology, 25(3), 343–354. 10.1037/0012-1649.25.3.343 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis MD (2005). Bridging emotion theory and neurobiology through dynamic systems modeling. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 28(2), 169–194. 10.1017/S0140525X0500004X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lotka AJ (1925). Elements of Physical Biology. Williams & Wilkins Company. [Google Scholar]

- Lunkenheimer ES, Olson SL, Hollenstein T, Sameroff AJ, & Winter C (2011). Dyadic flexibility and positive affect in parent–child coregulation and the development of child behavior problems. Development and Psychopathology, 23(2), 577–591. 10.1017/S095457941100006X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangelsdorf SC, Shapiro JR, & Marzolf D (1995). Developmental and Temperamental Differences in Emotion Regulation in Infancy. Child Development, 66(6), 1817–1828. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1995.tb00967.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messinger DS, Mahoor MH, Chow S-M, & Cohn JF (2009). Automated measurement of facial expression in infant–mother interaction: A pilot study. Infancy, 14(3), 285–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mischel W, Shoda Y, & Rodriguez MI (1989). Delay of gratification in children. Science, 244(4907), 933–938. 10.1126/science.2658056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt TE, Arseneault L, Belsky D, Dickson N, Hancox RJ, Harrington H, … Caspi A (2011). A gradient of childhood self-control predicts health, wealth, and public safety. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 108(7), 2693–2698. 10.1073/pnas.1010076108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morasch KC, & Bell MA (2012). Self-regulation of negative affect at 5 and 10 months. Developmental Psychobiology, 54(2), 215–221. 10.1002/dev.20584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oravecz Z, Tuerlinckx F, & Vandekerckhove J (2011). A hierarchical latent stochastic differential equation model for affective dynamics. Psychological Methods, 16(4), 468–490. 10.1037/a0024375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Edgar KE, & Fox NA (2005). Temperament and Anxiety Disorders. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 14(4), 681–706. 10.1016/j.chc.2005.05.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeifer M, Goldsmith HH, Davidson RJ, & Rickman M (2002). Continuity and Change in Inhibited and Uninhibited Children. Child Development, 73(5), 1474–1485. 10.1111/1467-8624.00484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinheiro J, Bates D, DebRoy S, Sarkar D, & R Core Team. (2016). nlme: Linear and Nonlinear Mixed Effects Models (Version 3.1–124). Retrieved from http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=nlme [Google Scholar]

- R Development Core Team. (2008). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. Retrieved from http://www.R-project.org. [Google Scholar]

- Ram N, & Gerstorf D (2009). Time-structured and net intraindividual variability: Tools for examining the development of dynamic characteristics and processes. Psychology and Aging, 24(4), 778–791. 10.1037/a0017915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ram N, & Grimm KJ (2015). Growth Curve Modeling and Longitudinal Factor Analysis. In Lerner RM (Ed.), Handbook of Child Psychology and Developmental Science (Vol. 1). John Wiley & Sons, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Rothbart MK, Ziaie H, & O’Boyle CG (1992). Self-regulation and emotion in infancy. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 1992(55), 7–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sroufe LA (1977). Wariness of Strangers and the Study of Infant Development. Child Development, 48(3), 731–746. 10.1111/1467-8624.ep10402182 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stansbury K, & Sigman M (2000). Responses of Preschoolers in Two Frustrating Episodes: Emergence of Complex Strategies for Emotion Regulation. The Journal of Genetic Psychology, 161(2), 182–202. 10.1080/00221320009596705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stifter CA, & Braungart JM (1995). The regulation of negative reactivity in infancy: Function and development. Developmental Psychology, 31(3), 448–455. 10.1037/0012-1649.31.3.448 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thelen E, & Smith LB (1994). A dynamic systems approach to the development of cognition and action. MIT Press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas EA, & Martin JA (1976). Analyses of parent-infant interaction. Psychological Review, 83(2), 141. [Google Scholar]

- Tong H, & Lim KS (1980). Threshold autoregression, limit cycles and cyclical data. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series B (Methodological), 245–292. [Google Scholar]

- Volterra V (1926). Variazioni e fluttuazioni del numero d’individui in specie animali conviventi. Memoria Della Reale Accademia Nazionale Dei Lincei. Ser. VI, Vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Widaman KF, Ferrer E, & Conger RD (2010). Factorial Invariance Within Longitudinal Structural Equation Models: Measuring the Same Construct Across Time. Child Development Perspectives, 4(1), 10–18. 10.1111/j.1750-8606.2009.00110.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.