Abstract

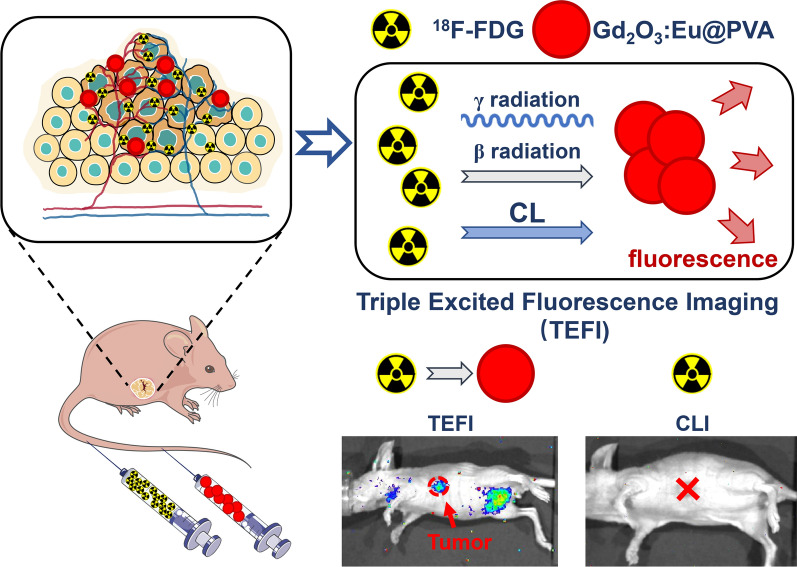

Cerenkov luminescence imaging (CLI) is a novel optical imaging technique that has been applied in clinic using various radionuclides and radiopharmaceuticals. However, clinical application of CLI has been limited by weak optical signal and restricted tissue penetration depth. Various fluorescent probes have been combined with radiopharmaceuticals for improved imaging performances. However, as most of these probes only interact with Cerenkov luminescence (CL), the low photon fluence of CL greatly restricted it’s interaction with fluorescent probes for in vivo imaging. Therefore, it is important to develop probes that can effectively convert energy beyond CL such as β and γ to the low energy optical signals. In this study, a Eu3+ doped gadolinium oxide (Gd2O3:Eu) was synthesized and combined with radiopharmaceuticals to achieve a red-shifted optical spectrum with less tissue scattering and enhanced optical signal intensity in this study. The interaction between Gd2O3:Eu and radiopharmaceutical were investigated using 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (18F-FDG). The ex vivo optical signal intensity of the mixture of Gd2O3:Eu and 18F-FDG reached 369 times as high as that of CLI using 18F-FDG alone. To achieve improved biocompatibility, the Gd2O3:Eu nanoparticles were then modified with polyvinyl alcohol (PVA), and the resulted nanoprobe PVA modified Gd2O3:Eu (Gd2O3:Eu@PVA) was applied in intraoperative tumor imaging. Compared with 18F-FDG alone, intraoperative administration of Gd2O3:Eu@PVA and 18F-FDG combination achieved a much higher tumor-to-normal tissue ratio (TNR, 10.24 ± 2.24 vs. 1.87 ± 0.73, P = 0.0030). The use of Gd2O3:Eu@PVA and 18F-FDG also assisted intraoperative detection of tumors that were omitted by preoperative positron emission tomography (PET) imaging. Further experiment of image-guided surgery demonstrated feasibility of image-guided tumor resection using Gd2O3:Eu@PVA and 18F-FDG. In summary, Gd2O3:Eu can achieve significantly optimized imaging property when combined with 18F-FDG in intraoperative tumor imaging and image-guided tumor resection surgery. It is expected that the development of the Gd2O3:Eu nanoparticle will promote investigation and application of novel nanoparticles that can interact with radiopharmaceuticals for improved imaging properties. This work highlighted the impact of the nanoprobe that can be excited by radiopharmaceuticals emitting CL, β, and γ radiation for precisely imaging of tumor and intraoperatively guide tumor resection.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12951-021-00920-6.

Keywords: Radiopharmaceuticals, Gd2O3:Eu, Cerenkov luminescence imaging, Optical imaging, Image-guided surgery

Introduction

Cerenkov luminescence imaging (CLI) is an important optical imaging technique based on Cerenkov radiation generated along with the decay process of various radionuclides [1–4]. Numerous Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved radiopharmaceuticals that were originally used for positron emission computed tomography (PET) can generate Cerenkov luminescence (CL), providing CLI with high potential for clinical translation. Therefore, since the first biomedical imaging of small animals in 2009, CLI-based tumor imaging and image-guided tumor resection surgery have been broadly investigated in pre-clinical applications and also explored in clinic [5–14]. The combination of CLI and PET enables surgeon to achieve the distribution of the same imaging agent before and during surgery, which may provide surgeon with more information on the tumor location and improve the accuracy of the tumor resection surgery [15, 16]. However, as optical signal intensity of CL is extremely weak, a long exposure time is often used in image acquisition. Besides, the ultraviolet-blue spectrum of the CL restricted penetration. These limit the application of CLI in intraoperative real-time tumor imaging.

Various fluorescent probes including small-molecule agents and nanoparticle (NP) probes have been combined with radiopharmaceuticals for improved imaging performances. Research has been focused on quantum dots (QDs) that can interact with CL, achieving emitted light in the near-infrared range with deeper tissue-penetration. This imaging technique was named as radiation excited luminescence imaging [17] or the secondary Cerenkov emission fluorescence imaging (SCIFI) [18]. Another research has demonstrated that a clinically available imaging agent, fluorescein sodium (FS) which has been commonly used for retinal blood vessel imaging, can also be excited by Cerenkov photons for surgical navigation [19]. However, low photon fluence of CL greatly restricted it’s interaction with fluorescent probes for in vivo imaging [20]. Therefore, novel imaging probes that can interact with radiopharmaceuticals through additional mechanisms have been desired. It was reported that the β particles and γ radiation generated along with the decay process of the radiopharmaceutical can also interact with some NPs [17, 21, 22]. These interactions can result in the ionization of the NP, with the fluorescence of higher signal intensity and longer wavelength emitted as the NP relaxes to the baseline state [23–27]. Therefore, the europium oxide (Eu2O3) NP that can be excited by CL and interact with γ radiation as well has been developed to achieve an enhanced optical intensity and red-shifted optical spectrum of radiopharmaceuticals, which improves the tumor-to-normal tissue ratio (TNR) and shortens the exposure time [26–28]. Recently, ZnGa2O4:Cr3+ NPs with persistent luminescence were reported to be activated by radiopharmaceuticals. The persistent luminescence of the NPs enabled long-lasting tumor detecting with high sensitivity and contrast [29, 30].

In this work, novel Eu3+ doped gadolinium oxide (Gd2O3:Eu) NPs were synthesized to be combined with radiopharmaceuticals for improved imaging performance. The commonly used clinical radiopharmaceutical 2-deoxy-2-18F-fluoroglucose (18F-FDG) was used to provide CL, β particles, and γ radiation. By mixing 18F-FDG and Gd2O3:Eu NPs, an enhanced red-shifted emission light was achieved. It was found that Gd2O3:Eu NPs interact with CL, β, and γ radiation, which turned the energy of radiopharmaceuticals into fluorescence with high efficiency. Therefore, the imaging method was named as triple-excited fluorescence imaging (TEFI). Moreover, Gd2O3:Eu NPs were modified by polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) for improvement of biocompatibility. In the end, performance of PVA modified Gd2O3:Eu (Gd2O3:Eu@PVA) on tumor imaging and image-guided surgery were evaluated using subcutaneous breast tumor-bearing mouse models. It was demonstrated that Gd2O3:Eu@PVA and 18F-FDG combination improved intraoperative tumor detection with a high imaging contrast.

Materials and methods

Synthesis of Gd2O3:Eu NPs

The hydrothermal method was used in the synthesis of Gd2O3:Eu NPs referring to the previous report [31]. 1.52 mmol Gd(NO3)3·9H2O, 0.08 mmol Eu(NO3)3·6H2O, and 0.2168 g urea were mixed with 8 mL of deionized water (DI water) and different amount of glycerol. The mixture was stirred until the solution turned clear and was then transferred into a stainless-steel reactor. The reaction lasted 500 min under 160 ℃. After the reaction, the solution was cooled and centrifugated. The product was washed with DI water three times. The product was then dried using a lyophilizer at –60 ℃ under vacuum. The dried precipitate was calcinated at 1000 ℃ for another 4 h. The dose of glycerol was regulated to achieve Gd2O3:Eu NPs of different sizes. Glycerol (3, 1, or 0.5 mL) was added to obtain Gd2O3:Eu with a diameter of 50, 100, and 200 nm (named as Gd2O3:Eu-50, Gd2O3:Eu-100, and Gd2O3:Eu-200), respectively.

PVA modification of NPs

To modify the NPs with PVA, Gd2O3:Eu-50, Gd2O3:Eu-100, and Gd2O3:Eu-200 were added into the DI water solution of PVA separately. The mixture of the Gd2O3:Eu NPs and PVA were stirred using quartz beads to ensure that the Gd2O3:Eu NPs were uniformly coated with PVA and formed Gd2O3:Eu-50, Gd2O3:Eu-100, and Gd2O3:Eu-200 modified with PVA (Gd2O3:Eu-50@PVA, Gd2O3:Eu-100@PVA, and Gd2O3:Eu-200@PVA). The mixture was then dried using a lyophilizer at -60 ℃ under vacuum.

Characterization of Gd2O3:Eu and Gd2O3:Eu@PVA NPs

The size and morphology of Gd2O3:Eu NPs were tested by Transmission Electron Microscope (TEM, JEOL Ltd, Tokyo, Japan). The diameters of the NPs were measured with Image J according to the TEM images (National Institutes of Health, Maryland, USA). Fluorescent properties including emission and excitation spectra were measured using EnSpire Multimode Plate Readers (PerkinElmer, Inc., Massachusetts, USA). The crystal characteristics of the nanoparticles were tested with an Ultima IV X-ray diffractometer (XRD, Rigaku, Tokyo, Japan). X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) measurements were carried out with Thermo Scientific K-Alpha + (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Massachusetts, USA).

Fluorescence imaging

The fluorescence images were acquired with the IVIS Spectrum imaging system (PerkinElmer, Inc., Massachusetts, USA). In the experiments on the influencing factors of optical signal intensity of Gd2O3:Eu NPs, an exposure time of 60 s was adopted. While in the in vitro experiments to verify the interaction type, an exposure time of 300 s was adopted. To evaluate the spectrum of the emitted light, a series of bandpass filters with a discrete center wavelength from 500 to 840 nm integrated into the IVIS system was adopted with an exposure time of 20 s. For the experiments on tissue penetration, an open filter was applied, with the exposure time set to be 5 s. In the animal experiments of phantom study, imaging, and image-guided surgery, an open filter and an exposure time of 300 s were used.

Investigation of the factors affecting radical interaction

To select the most suitable NP for biomedical imaging, 5 mg Gd2O3:Eu-50, Gd2O3:Eu-100, Gd2O3:Eu-200, Gd2O3:Eu-50@PVA, Gd2O3:Eu-100@PVA, or Gd2O3:Eu-200@PVA were set in 6 different Eppendorf (EP) tubes and mixed with 18F-FDG (430 μCi, 100 μl), respectively. Images of the 6 EP tubes were acquired to evaluate the signal intensity. Gd2O3:Eu and Gd2O3:Eu@PVA with a diameter of 100 nm were selected for the following ex vivo and in vivo experiments based on the aforementioned experimental results.

To investigate the impact of distance between the excitation source (18F-FDG) and the NP (Gd2O3: Eu) on the optical intensity produced, a single well of a transparent 96-well plate loaded with 18F-FDG (730 μCi, 100 μl), and an EP tube containing Gd2O3:Eu-100 (20 mg) was placed with the distance between the bottom of the tube and the well set to be 10, 20, 30, 40, and 50 mm. The signal intensity of Gd2O3:Eu-100 NP on each image was measured, and its correlation with distance was then determined.

To evaluate impact of radioactivity, a series of EP tubes containing 100 μl of 18F-FDG with different radioactivity (1128, 552, 285, 145, 73, 36, 18, 9, 4, and 2 μCi) were applied as excitation source successively. Gd2O3:Eu-100 (20 mg) was placed in another EP tube. The distance between them was set to be 10 mm. The signal intensity of the Gd2O3:Eu-100 NP was measured and correlated to the radioactivity of the 18F-FDG in each image.

To assess the impact of mass, 18F-FDG (730 μCi, 100 μl) was set in a well of a transparent 96-well plate. Gd2O3:Eu-100 with different mass (20, 10, 5, 2.5, 1 mg) was placed in EP tubes, respectively. The distance between the well and the tubes was 10 mm. the signal intensity of each EP tube containing Gd2O3:Eu-100 with different mass was measured and correlated to the mass.

Eu2O3 of the same mass with Gd2O3: Eu was used as a comparison in each experiment as stated above.

Investigation of interaction mechanisms between Gd2O3:Eu and 18F-FDG

To reveal the mechanisms that result in the emission of light, Gd2O3:Eu-100 powder (20 mg) and 18F-FDG (2.2 mCi, 100 μl) were placed at the bottom of two EP tubes. Images were first acquired when the bottom of the two EP tubes was placed next to each other, with no blocking between them. Therefore, the CL, β particle and γ radiation generated from 18F-FDG can all interact with Gd2O3:Eu-100. An aluminum plate that blocked CL and β particles and a lead plate that blocked CL, β particles, and γ radiation were then placed between the two tubes in order. Black tapes were then used to cover the EP tube containing 18F-FDG to block CL only. Images were acquired in each step. Besides, to further investigate the contribution of CL to the emission, the two EP tubes containing 18F-FDG and Gd2O3:Eu-100 were placed with the bottom 20 mm apart. Two mirrors were placed on both sides of the tubes to reflect CL. Optical images were acquired to reveal the three types of interaction with CL, β particle, and γ radiation. With a lead plate set between the two tubes, β particles and γ radiation were blocked, where only CL can interact with the Gd2O3:Eu-100. Optical images were then acquired for evaluation of light emission caused by CL. The same operation was repeated with Gd2O3:Eu-100 replaced by Eu2O3 powder (20 mg) to investigate the contribution of CL to the emission when the Eu2O3 NP was used.

Assessment of emission spectrum and tissue penetration ability of the light

Gd2O3:Eu, Gd2O3:Eu@PVA of different sizes (50, 100, and 200 nm) and Eu2O3 (powder, each 5 mg) were mixed with 18F-FDG (430 μCi, 100 μl) separately in a well of the 96-well plate. Saline solution (100 μl) and 18F-FDG (430 μCi, 100 μl) were used as the control. The penetration ability of the light emitted from the mixtures in biological tissue was then evaluated using a porcine intestine covering the 96-well plate.

Cell culturing and animal model establishment

All the experimental procedures involving animals were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Fifth Affiliated Hospital, Sun Yat-sen University (2020071401). 4T1 mouse mammary tumor cells were cultured with RPMI 1640 medium (Gibco, Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Gibco, Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA), 100 U/mL penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) in a humidified incubator at 37 °C with 5% CO2.

Female balb/c nude mice of 4 weeks (Beijing Vital River Laboratory Animal Technology Co. Ltd, Beijing, China) were used in this study. The subcutaneous breast cancer mice models were established by injecting 5 × 106 4T1 mouse mammary tumor cells subcutaneously in mice. Seven days after injection, the mice were used for imaging and image-guided surgery experiment. Animal surgery and imaging were performed under isoflurane gas anesthesia (3% isoflurane and air mixture), and all the possible actions were employed to minimize the suffering of the mice.

In vivo optical imaging using capillary phantoms

Two capillaries were subcutaneously embedded into the back of the athymic nude mouse. One capillary was filled with 18F-FDG (84 μCi, 20 μl), while the other was filled with the mixture of Gd2O3:Eu@PVA (2 mg) and 18F-FDG (84 μCi, 20 μl). PET and optical imaging were performed for comparison.

In vivo evaluation of the Gd2O3:Eu-100@PVA and 18F-FDG mixture

To study the performance of Gd2O3:Eu-100@PVA in improving the optical signal intensity of 18F-FDG in vivo, breast tumor-bearing mice (n = 8) were randomly assigned to the TEFI and CLI group (n = 4 for each group). For the TEFI group, mice were injected intravenously with 18F-FDG (250 μCi, 200 μl) and Gd2O3:Eu-100@PVA (1 mg/ml, 100 μl), while the mice in the CLI group were injected with only 18F-FDG (1 mg/ml, 100 μl). Imaging was performed 1.5 h after injection using the IVIS system.

PET imaging of small animals

Static 5-min PET images of animals injected with 18F-FDG were acquired using a preclinical PET/CT scanner (Genisys PET, SofieBiosciences, Inc., USA). The data acquisition mode of 18F was integrated into the device.

Biodistribution of Gd2O3:Eu@PVA

The tumor-bearing mice in the TEFI group were euthanized immediately after NPs based optical imaging. The tumor, heart, liver, spleen, lung, kidney, intestine, brain, and muscle were harvested, and blood was also collected for ex vivo optical imaging.

Results

The characteristic of the synthesized Gd2O3:Eu NPs

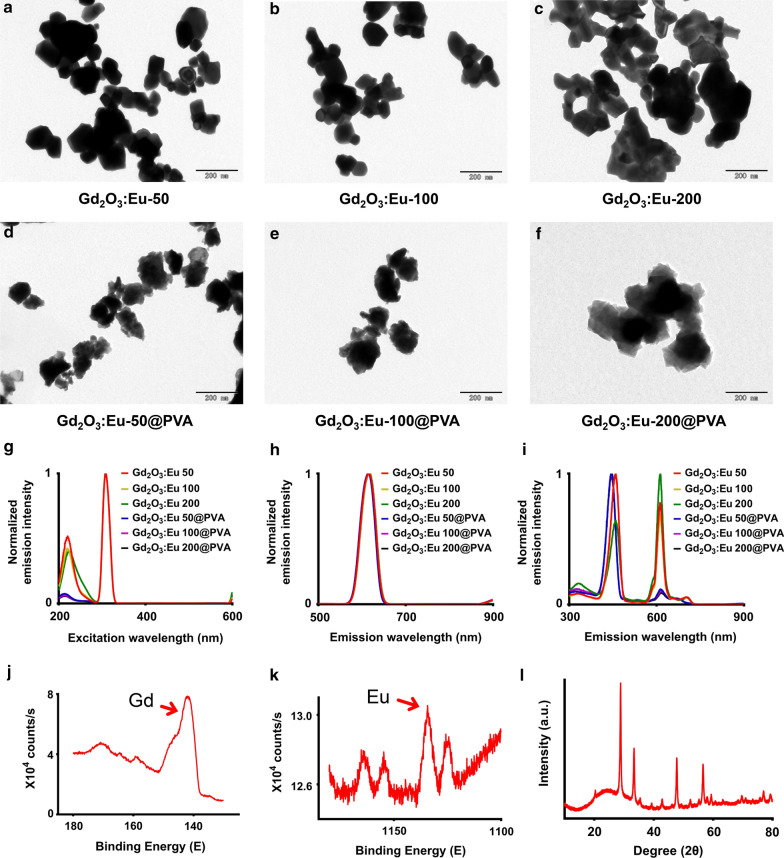

The size of Gd2O3:Eu-50, Gd2O3:Eu-100, and Gd2O3:Eu-200 NPs was in ranges of 50–75, 90–110, and 170–230 nm, respectively (Fig. 1a–c), as measured on the TEM images. The surface modification with PVA did not significantly change the size and morphology of Gd2O3:Eu NPs, with the diameters laid in ranges of 65–88, 95–116, and 195–244 nm (Fig. 1d–f).

Fig. 1.

Nanoparticle morphology and spectrum. a–f the TEM images of the NPs with different sizes and surface modification. Scale bar, 200 nm. g the excitation peaks lays on 214 and 308 nm, keeping the emission fixed at 620 nm. h an emission peak of 620 nm was displayed under 214 nm excitation. i emission peaks of 460 nm, 620 nm, and 700 nm were displayed under 308 nm excitation light. j, k the XPS spectrum of Gd (j) and Eu (k) from the Gd2O3:Eu-100 NP. l XRD patterns of the Gd2O3:Eu-100 NP

The excitation spectrum showed that the maximum excitation wavelength of the NPs, including Gd2O3:Eu and Gd2O3:Eu@PVA with different diameters (50,100, 200 nm) was 308 nm, with a smaller peak laying on around 214 nm (Fig. 1g). When excited by 308 nm excitation light, the emission peak was 620 nm for all the NPs (Fig. 1h). When excited by 214 nm excitation light, the emission spectrum had three peaks lying on 460, 620, and 700 nm (Fig. 1i).

The peaks of the XPS spectrum at the 141.98 and 1134.48 eV binding energy proved the presence of the Gd and Eu (Fig. 1j, k). The XRD spectrum of the Gd2O3:Eu-100 NP was matched with the standard JCPDS 12–0797 card. The XRD peaks were related only to the Gd2O3 nanoparticles (Fig. 1l).

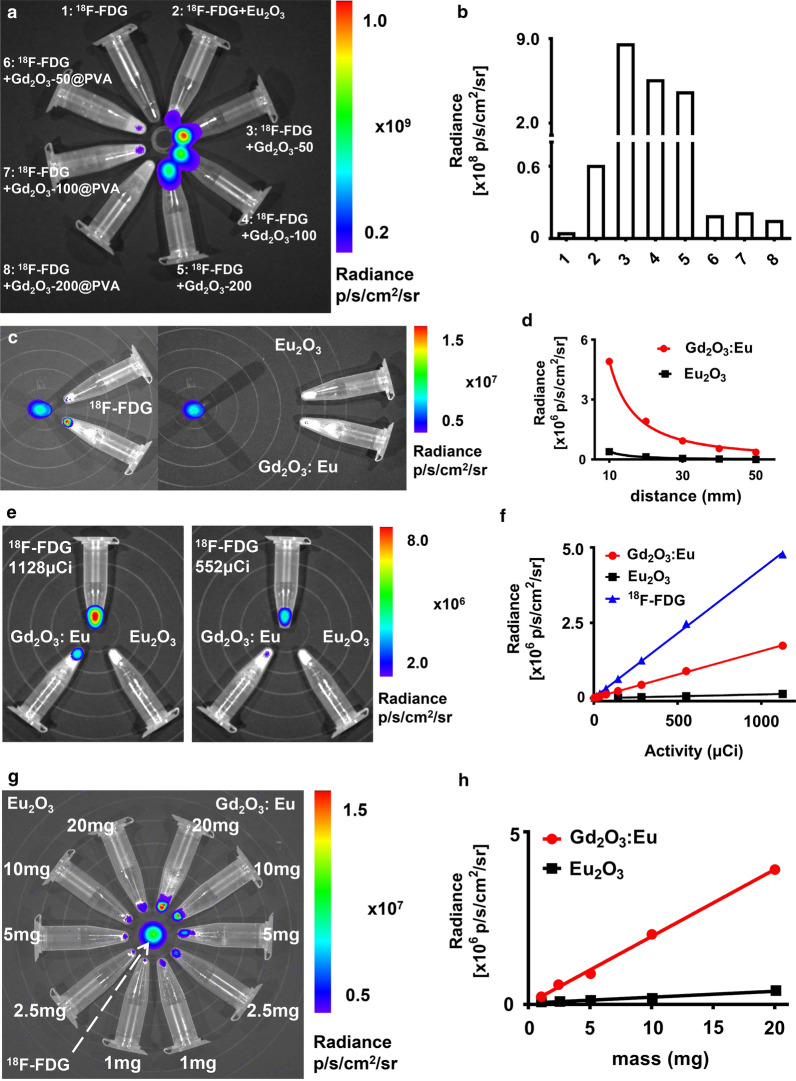

The influential factors of optical signal intensity

The optical signal intensity of the NPs was affected by the particle size and surface modification (Fig. 2a, b). For Gd2O3:Eu without surface modification of PVA, the optical signal intensity decreased as the particle size increased, with the Gd2O3:Eu-50 generating light with the highest optical signal intensity and Gd2O3:Eu-200 generating light with the lowest optical signal intensity. For Gd2O3:Eu with surface modification by PVA, Gd2O3:Eu-100@PVA generated light with the highest optical signal intensity while Gd2O3: Eu-200@PVA generated light with the lowest optical signal intensity. As the mass of the particles used were kept the same, the amount of the Gd2O3:Eu may be replaced by PVA. Therefore the optical signal was influenced by PVA modification though it may improve biocompatibility. With the results obtained above, the 100 nm NPs were further evaluated in the following experiments, with Gd2O3:Eu-100@PVA used in the in vivo experiments and Gd2O3:Eu-100 tested in the ex vivo experiments.

Fig. 2.

The factors impacting the optical signal intensity of interaction. a,b, optical images (a) and quantitative analysis (b) displayed that the size and surface modification of the NPs affected the optical signal intensity. c, d the optical signal intensity is in inverse proportion to the interaction distance between Gd2O3:Eu-100/ Eu2O3 and 18F-FDG. e, f the optical signal intensity is in direct proportion to the radioactivity of 18F-FDG. g, h the optical signal intensity is in direct proportion to the mass of the Gd2O3:Eu/ Eu2O3

The influencing factors of the optical signal intensity also included excitation distance, the amount of the radioactivity of 18F-FDG, and the mass of NPs (Gd2O3:Eu-100 and Eu2O3). The optical signal intensity decreased exponentially as the excitation distance increased for both Gd2O3:-Eu-100 and Eu2O3, with R2 of 0.9972 for Gd2O3:Eu-100 and 0.9931 for Eu2O3 (Fig. 2c, d, Additional file 1: Fig. S1a). The optical signal intensity of the NP increased linearly with the increasing of the radioactivity of 18F-FDG, with R2 of 0.9994 for Gd2O3:-Eu and 0.9998 for Eu2O3 (Fig. 2e, f, Additional file 1: Fig. S1b). As for the mass of NPs, the optical signal intensity of the NPs also increased linearly with the mass of NPs, with R2 of 0.9975 for Gd2O3:Eu and 0.9737 for Eu2O3 (Fig. 2g, h). The optical signal of Gd2O3:Eu was much higher than that of Eu2O3 in each of the studies.

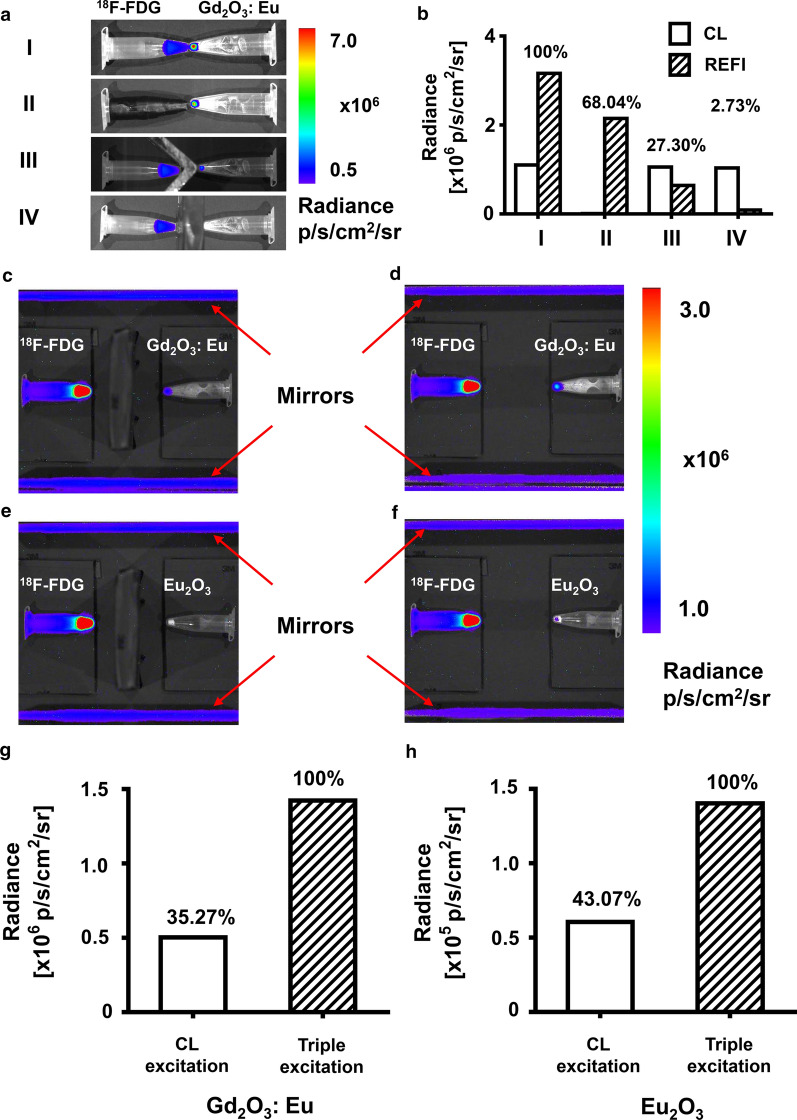

Investigation of the optical signal caused by CL, β particles, and γ radiation of 18F-FDG

It was observed that emission light was generated by Gd2O3:Eu 100 through interactions with CL, β particle, and γ radiation generated by 18F-FDG (Fig. 3a). The overall optical signal intensity caused by all three types of interactions was set to be 100% (Fig. 3a row I and Fig. 3b I). With only CL blocked by black tape, the optical signal caused by interaction with β particles and γ radiation was observed, which accounted for 68.04% of the overall optical signal intensity (Fig. 3a row II and Fig. 3b II). With CL and β particles both blocked by an aluminum plate, the optical signal caused by interaction with γ radiation was acquired, which only accounted for 27.30% of the overall optical signal intensity (Fig. 3a row III and Fig. 3b III). In the further experiment where CL, β, and γ radiation were all blocked by a lead plate, the optical signal was barely acquired (Fig. 3a row IV and Fig. 3b IV). It was calculated that 31.97% of the optical signal was caused by CL, 40.74% of the optical signal was caused by β particles, and 27.30% was caused by γ radiation. Moreover, with β particles and γ radiation blocked by a lead plate, but CL reflected by two mirrors, the optical signal caused by interaction with CL was evaluated independently (Fig. 3c–f). For Gd2O3:Eu-100, 35.27% of the optical signal was caused by CL, which was in accordance with the result of the experiments above (Fig. 3c, d). For Eu2O3, the previously reported radiopharmaceutical excitable NP, 43.07% of the optical signal was caused by CL according to measurement (Fig. 3e, f).

Fig. 3.

The investigation on the excitation mechanism. a the overlayed images of the optical signal generated by Gd2O3:Eu-100. b the optical signal intensity of each tube. c–f the images of the optical signal generated by Gd2O3:Eu-100 through interaction with CL, with β particles and γ radiation blocked by the lead plate and CL reflected by the mirrors (c), by Gd2O3:Eu-100 through interaction with CL, β particles, and γ radiation (d), by Eu2O3 through interaction with CL (e) and by Eu2O3 through interaction with CL, β particles, and γ radiation (f). g, h the optical signal intensity of each condition for Gd2O3:Eu-100 (g) and Eu2O3 (h)

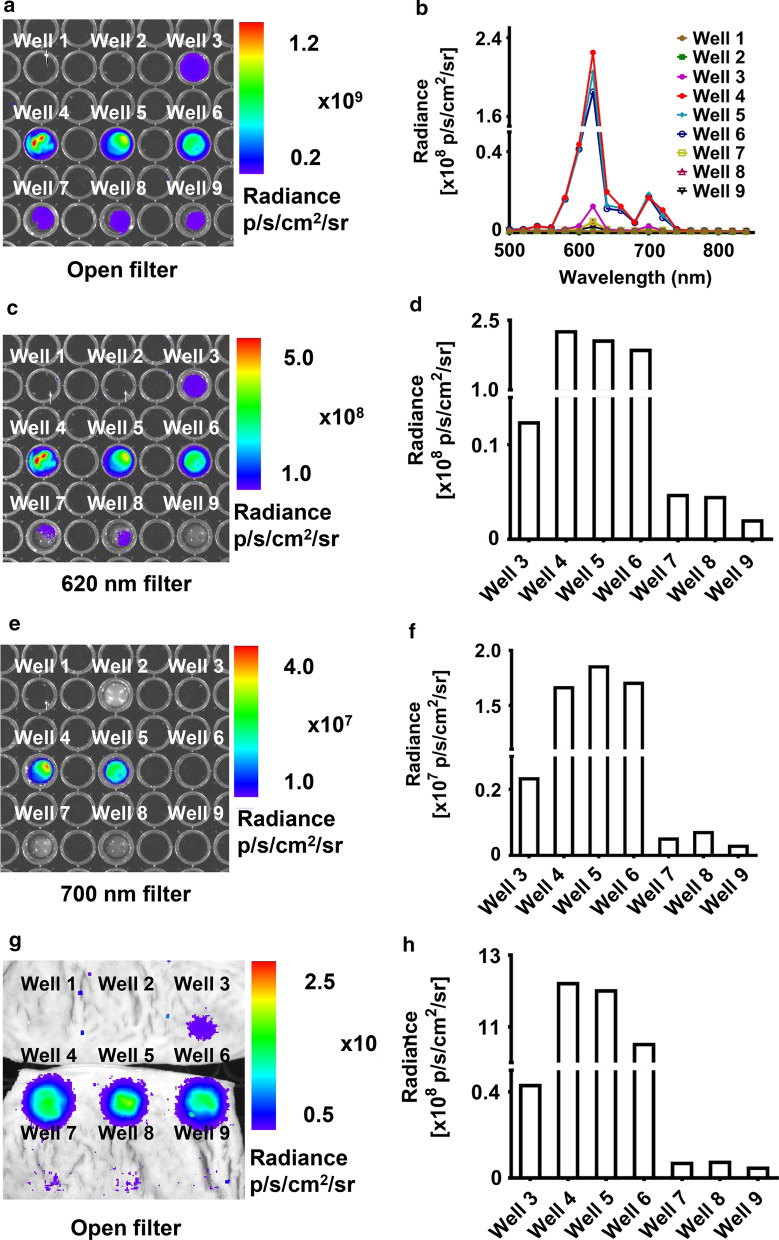

Characterization and tissue penetration of the red-shifted emission light

The 5 mg NPs (Eu2O3, Gd2O3:Eu, and Gd2O3:Eu@PVA) extensively enhanced the optical signal intensity and tissue penetration capacity of 18F-FDG (Fig. 4). The optical image acquired with an open filter demonstrated that the signal intensity of the mixture of Gd2O3: Eu NPs (with diameters of 50, 100, and 200 nm) and 18F-FDG were all higher than that of 18F-FDG alone and the mixture of Eu2O3 and 18F-FDG. It was demonstrated that the optical signal intensity of the novel Gd2O3:Eu-50 NPs was 16.19 times higher than that of Eu2O3 when mixed with 18F-FDG, and reached 369 times higher than that of 18F-FDG alone (Fig. 4a). The emission peak of the emission light measured using bandpass filters also laid on 620 and 700 nm, which was in accordance with the spectrum measured using a spectrometer previously (Fig. 4b). Images acquired with a 620 nm filter demonstrated that the optical signal intensity of Gd2O3:Eu-50 was the highest, followed by the Gd2O3:Eu-100, and Gd2O3:Eu-200 (Fig. 4c, d). While mentioning the Gd2O3:Eu NPs modified by PVA, it was the same case that Gd2O3:Eu-50@PVA possessed the emission light with the highest intensity, followed by Gd2O3:-Eu-100@PVA and Gd2O3:Eu-200@PVA (Fig. 4c, d). However, when it came to the 700 nm filter, the Gd2O3:Eu-100 possessed the highest optical signal intensity (Fig. 4e, f). Therefore, for Gd2O3:Eu with surface modification, with the relatively weak optical signal of 620 nm wavelength, the accumulated optical signal of a broad spectrum of Gd2O3:Eu-100@PVA was the highest among Gd2O3:Eu NPs with surface modification.

Fig. 4.

The profile of optical imaging of the Gd2O3:Eu and 18F-FDG mixture. The contents in the Well 1–9 in this figure are listed as follows: Well 1: saline solution. Well 2: 18F-FDG. Well 3: Eu2O3 + 18F-FDG. Well 4: Gd2O3:Eu-50 + 18F-FDG. Well 5: Gd2O3:Eu-100 + 18F-FDG. Well 6: Gd2O3:Eu-200 + 18F-FDG. Well 7: Gd2O3:Eu-50@PVA + 18F-FDG. Well 8: Gd2O3:Eu-100@PVA + 18F-FDG. Well 9: Gd2O3:Eu-200@PVA + 18F-FDG. a optical imaging with an open filter. b the emission spectrum of contents in each well. c, d optical image (c), and quantification of the optical signal intensity (d) with 620 nm filter. e, f optical image (e), and quantification of the optical signal intensity (f) with 700 nm filter. g, h optical image (g), and quantification of the optical signal intensity (h) with swine intestine covered on the top

With a porcine intestine covered on the top, the CL of the 18F-FDG was nearly blanketed and almost unmeasurable. Whereas the optical signal of the NPs and 18F-FDG mixtures were rather higher. The Gd2O3:Eu-50 showed the highest optical signal intensity among the three Gd2O3:Eu-NPs with different diameters. While Gd2O3:-Eu-100@PVA showed the highest optical signal intensity among the three Gd2O3:Eu NPs with surface modification (Fig. 4g, h).

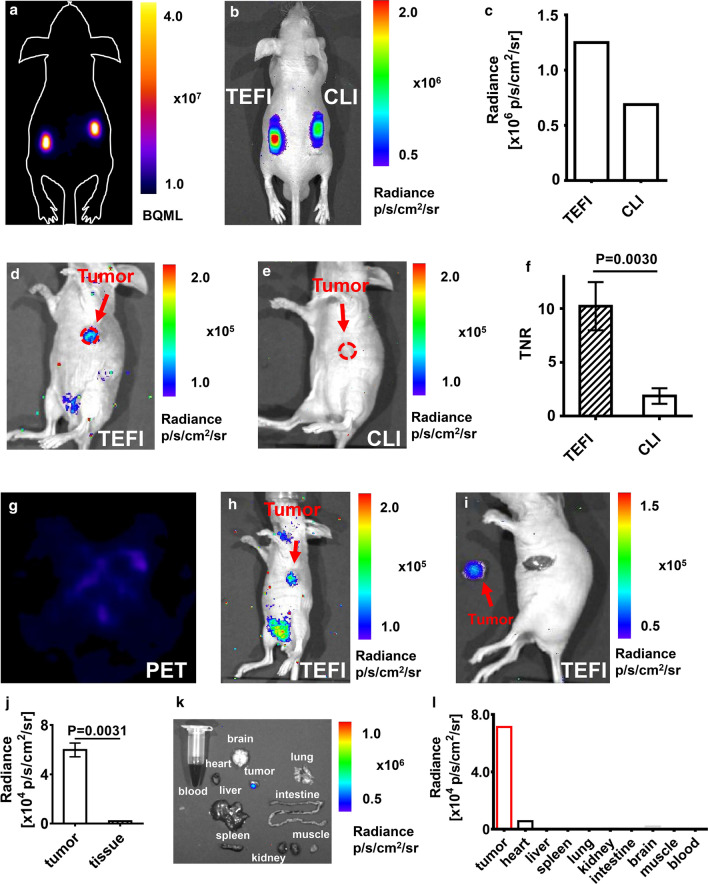

Validation using in vivo capillary phantom and living animal models

With the living phantom established using capillaries that contained 18F-FDG or 18F-FDG mixed with Gd2O3:Eu-100@PVA, the feasibility of the in vivo use of Gd2O3:Eu-100@PVA NP was investigated. The PET image showed an equal signal intensity of the two implanted tubes, indicating similar radioactivity of 18F-FDG in the two capillaries (Fig. 5a). Nevertheless, the optical signal intensity of the 18F-FDG and Gd2O3:Eu-100@PVA mixture was enhanced twice of the intensity of 18F-FDG alone upon measurement (Fig. 5b, c).

Fig. 5.

In vivo phantom and animal experiments. a the PET image of the animal phantom showed the same radioactivity of 18F-FDG in the capillaries. b, c the optical image and the quantitative analysis showed a higher signal intensity of the mixture of Gd2O3:Eu-100@PVA and 18F-FDG compared with 18F-FDG alone (left: 18F-FDG (84 μCi, 20 μl) + Gd2O3:Eu@PVA (2 mg), right: 18F-FDG (84 μCi, 20 μl)). d Gd2O3:Eu-100@PVA enhanced the optical signal of 18F-FDG, showing an obvious tumor optical signal. e CLI displayed no obvious signal of the tumor. f the TNR of the tumor was also increased by the Gd2O3:Eu-100@PVA NP. g the PET image of the tumor-bearing mouse injected the mixture of Gd2O3:Eu-100@PVA and 18F-FDG displayed no obvious tumor signal. h the Gd2O3: Eu 100@PVA enhanced the optical signal of the tumor. i the tumor was resected with the guidance of the optical image. j the optical signal intensity of the tumor was significantly higher than that of the surrounding normal tissue. k, l the optical image, and the quantification showed the significantly higher optical signal intensity of tumor compared with muscles and other organs obtained from the tumor-bearing mouse

For in vivo imaging, Gd2O3:Eu-100@PVA combined with 18F-FDG provided a higher tumor imaging contrast compared with CLI using 18F-FDG alone (Fig. 5d, e). The optical signal of the tumor was not observed using CLI (Fig. 5d). However, with Gd2O3:Eu-100@PVA injected together with 18F-FDG, the optical signal of the tumor was visualized with high contrast using TEFI (Fig. 5e). The tumor-to-normal tissue ratio (TNR) of the Gd2O3:Eu-100@PVA and 18F-FDG was significantly higher than that of CLI (10.24 ± 2.24 vs. 1.87 ± 0.73, P = 0.0030, Fig. 5f).

Triple-excited fluorescence (TEF) image-guided tumor surgery and biodistribution

For the mice models injected with 18F-FDG and Gd2O3:Eu-100@PVA, the PET images acquired 1.5 h after injection showed no obvious tumor signal (Fig. 5g). However, the TEF images showed an obvious tumor signal (Fig. 5h). The tumor was then resected under the guidance of TEF images, with an ex vivo optical image of the tumor demonstrating that the tumor had an enhanced optical signal compared with normal tissue background (Fig. 5i). The ex vivo tumor signal intensity was significantly higher than that of the surrounding normal tissue (P = 0.0031, Fig. 5j).

The ex vivo optical images of organs or tissue (tumor, heart, liver, spleen, lung, kidney, intestine, brain, muscle, and blood) of mice assigned to TEFI group were acquired (Fig. 5j). The optical signal intensity of the tumor was way much higher than those of other organs, followed by the heart with a faint optical signal. The optical signal of other organs or tissue was extremely weak, indicating an outstanding capability of tumor delineation using this novel technique.

Discussion

Radical resection is usually difficult to achieve in surgery of malignant tumors, such as breast cancer, glioblastomas, and lung cancer. Therefore, technologies that can assist intraoperative tumor identification are in urgent need. Optical imaging help to identify tumors in real-time during surgery, which leads to high potential for clinical translation. In this study, Gd2O3:Eu NPs have been combined with a commonly used clinical radiopharmaceutical 18F-FDG for outstanding imaging performance. For biomedical use, Gd2O3:Eu was modified with PVA, and the performance of tumor imaging and image-guided surgery was investigated in small animal models. It is demonstrated on animal models that the mixed 18F-FDG and Gd2O3:Eu-100@PVA performs much better than CLI in tumor imaging and it can be successfully used in image-guided surgery.

When mixed with 18F-FDG in vitro, the novel Gd2O3:Eu-50 NPs achieve a signal intensity 16.19 times higher than that of Eu2O3, and approximately 369 times higher than that of CL generated by 18F-FDG alone. The enhanced signal intensity caused by Gd2O3:Eu NPs enables in vivo tumor imaging with high contrast. It is also demonstrated that the optical signal intensity decreases as the diameter increases for NPs without PVA modification. This may be affected by the amount of the molecule involved as reported before [32].

The Gd2O3:Eu NPs have been modified with PVA for improving biocompatibility, which is widely used [33, 34]. With modification, the optical intensity is weakened compared with Gd2O3:Eu without modification. However, to still take the advantage of high biocompatibility, modified Gd2O3:Eu was evaluated in the in vivo experiment of tumor imaging and image-guided surgery. Gd2O3:Eu-100@PVA with a diameter of 100 nm generates an optical signal with the highest intensity among the three modified Gd2O3:Eu NPs with different diameters. In the experiment of measuring the optical spectrum, the emission light of 700 nm generated by Gd2O3:Eu-100@PVA is stronger than that of Gd2O3:Eu-50@PVA and Gd2O3:Eu-200@PVA. This may be caused by the interaction between PVA and the radiopharmaceutical or the emitted light.

The ex vivo experiments have been performed with Gd2O3:Eu first. It is demonstrated that the optical signal generated from interaction with CL, β particles, and γ radiation is 33, 40, and 27%, respectively. The experiment using mirror reflection also achieves a similar percentage of interaction with CL. While in the previous study on REFI with Eu2O3, only 4.6% of the optical signal is generated by CL and 95.4% by γ radiation [26]. This study indicates that Gd2O3:Eu based nanoparticles are better CL absorbers than Eu2O3.

The optical spectrum acquired by optical signal using the IVIS spectrum imaging system aligns with that measured by the spectrometer, with a peak of 620 nm and a small peak of 700 nm. Compared with CL with a blue-ultraviolet spectrum, the red-shifted and enhanced light provide deeper penetration and shortened exposure time, which improves the clinical translation potential of TEFI. With the porcine intestine covered on the top of the 96-well plate containing 18F-FDG and the NPs, the optical signal of the mixture of 18F-FDG and Gd2O3:Eu is approximately 28 times higher than that of the 18F-FDG and Eu2O3 mixture. This demonstrates the improved tissue penetration capacity with Gd2O3:Eu combined with 18F-FDG. This may enable a reduced dose of NPs used with an outstanding imaging performance, which reduce potential toxicity.

In clinic, PET provides pre-operative imaging on functional and metabolism information of diseases. 18F-FDG used in this study is one of the commonly used radiopharmaceuticals for PET in clinic. In this study, the in vivo PET shows no obvious signal of the tumor. While optical images using Gd2O3:Eu-100@PVA and 18F-FDG reveals an obvious optical signal of the tumor. This indicates that the optical imaging of Gd2O3:Eu-100@PVA and 18F-FDG has high potential for tumor detection.

CLI is an emerging optical imaging method that can use radiopharmaceutical for optical imaging. CLI has been applied in intraoperative imaging in 2017 where ex vivo breast tumor tissue samples are obtained intraoperatively and imaged with a specially designed imaging device for CLI, which is used to display the tumor boundary [9]. However, the optical signal intensity of CLI is relatively weak, restricting the real-time intraoperative tumor imaging. Therefore, various methods have been put forward to achieve the enhancement of optical signal intensity. In 2015, Eu2O3 NP was combined with radiopharmaceuticals in optical imaging, demonstrating a better signal-to-background ratio compared with FMI [26]. As the Eu2O3 NPs mainly interact with γ radiation, the enhancement of optical signal intensity obtained by the Eu2O3 NP is still needed to be improved. Besides, the NP without surface modification raises the concern of in vivo toxicity. Another imaging technique, Cerenkov radiation energy transfer (CRET), has been explored using clinical radiopharmaceuticals 18F-FDG and 18C-choline (11C-CHO) together with FDA-approved fluorophore fluorescein sodium (FS). The application of FS further improves the potential of clinical translation as it has been approved for clinical use by the FDA and extensively investigated in different imaging fields. However, FS only translates energy of CL into long-wavelength fluorescence, which does not take full advantages of radiation emitted by radiopharmaceuticals except for CL, such as β particles and γ radiation [18]. In this research, the novel Eu3+ doped gadolinium oxide with PVA modification can translate the energy of CL, β particles, and γ radiation generated along with the decay process of 18F-FDG. This enhances the optical signal production capability of Gd2O3:Eu@PVA NP.

The gadolinium-based nanoparticle was reported to have enhanced MRI T1 signal [35, 36]. Therefore, the nanoparticles reported in this article has the potential to be applied as multi-modality tumor imaging. Besides, as fluorescence imaging with light of longer wavelength has shown outstanding performance [37, 38], novel NPs with emission of longer wavelength are of great potential to combine with radiopharmaceuticals for better biomedical use.

Conclusion

A novel Eu3+ doped gadolinium oxide (Gd2O3:Eu) is combined with 18F-FDG to achieve a red-shifted emitting spectrum and enhanced optical signal intensity. The high conversion efficiency of the radiation energy is realized using the novel NP. Moreover, with PVA modification, Gd2O3:Eu@PVA with high biocompatibility shows capability for tumor imaging and image-guided surgery in small animal models. Our study highlights that combining Gd2O3:Eu with 18F-FDG greatly integrate the merit of optical imaging and nuclear imaging, worthy of further investigation of more NPs with improved optical properties and biocompatibility for pre-clinical and clinical use.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Figure 1. The optical images with different interaction distances and radioactivity.

Acknowledgements

We thank Prof. Zhanjun Gu and Dr. Linji Gong from the Institute of High Energy Physics Chinese Academy of Sciences for the technical assistance on the preparation of the nanoparticles involved in this manuscript.

Authors’ contributions

XS performed the experiment, analyzed the data acquired and wrote the manuscript. ZH and JT supervised the designation of the experiments. CC and ZZ assisted with data analysis.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2017YFA0205200), National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) (62027901, 81930053, 92059207, 81227901), Beijing Natural Science Foundation (JQ19027), the innovative research team of high-level local universities in Shanghai, and the Zhuhai High-level Health Personnel Team Project (Zhuhai HLHPTP201703). The authors would like to acknowledge the instrumental and technical support of the multi-modal biomedical imaging experimental platform, Institute of Automation, Chinese Academy of Sciences.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated or analyzed during this study are included in the manuscript and the supplementary information files.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study only involved small animals. All the experimental procedures involving animals were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Fifth Affiliated Hospital, Sun Yat-sen University (2020071401).

Consent for publication

All the co-authors have approved the manuscript and agree with submission to your esteemed journal. No individual person’s data was involved in this manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Xiaojing Shi, Email: shixiaojing2017@ia.ac.cn.

Caiguang Cao, Email: caocaiguang2018@ia.ac.cn.

Zeyu Zhang, Email: zhang.zey.doc@gmail.com.

Jie Tian, Email: jie.tian@ia.ac.cn.

Zhenhua Hu, Email: zhenhua.hu@ia.ac.cn.

References

- 1.Mitchell GS, Gill RK, Boucher DL, Li C, Cherry SR. In vivo Cerenkov luminescence imaging: a new tool for molecular imaging. Philos T R Soc A. 1955;2011(369):4605–4619. doi: 10.1098/rsta.2011.0271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grootendorst MR, Cariati M, Kothari A, Tuch DS, Purushotham A. Cerenkov luminescence imaging (CLI) for image-guided cancer surgery. Clin Transl Imaging. 2016;4(5):353–366. doi: 10.1007/s40336-016-0183-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang Z, Cai M, Bao C, Hu Z, Tian J. Endoscopic Cerenkov luminescence imaging and image-guided tumor resection on hepatocellular carcinoma-bearing mouse models. Nanomed-Nanotechnol. 2019;17:62–70. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2018.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Qin Chenghu, Zhong Jianghong, Hu Zhenhua, Yang Xin, Tian Jie. Recent Advances in Cerenkov Luminescence and Tomography Imaging. IEEE J Sel Top Quant. 2012;18(3):1084–1093. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Robertson R, Germanos MS, Li C, Mitchell GS, Cherry SR, Silva MD. Optical imaging of Cerenkov light generation from positron-emitting radiotracers. Phys Med Biol. 2009;54(16):N355. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/54/16/N01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang Z, Qu Y, Cao Y, Shi X, Guo H, Zhang X, Zheng S, Liu H, Hu Z, Tian J. A novel in vivo Cerenkov luminescence image-guided surgery on primary and metastatic colorectal cancer. J Biophotonics. 2020;13(3):e201960152. doi: 10.1002/jbio.201960152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Song T, Liu X, Qu Y, Liu H, Bao C, Leng C, Hu Z, Wang K, Tian J. A novel endoscopic Cerenkov luminescence imaging system for intraoperative surgical navigation. Mol Imaging. 2015;14(8):7290.2015.00018. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu M, Zheng S, Zhang X, Guo H, Shi X, Kang X, Qu Y, Hu Z, Tian J. Cerenkov luminescence imaging on evaluation of early response to chemotherapy of drug-resistant gastric cancer. Nanomed-Nanotechnol. 2018;14(1):205–213. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2017.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grootendorst MR, Cariati M, Pinder SE, Kothari A, Douek M, Kovacs T, Hamed H, Pawa A, Nimmo F, Owen J, Ramalingam V, Sethi S, Mistry S, Vyas K, Tuch DS, Britten A, Hemelrijck MV, Cook GJ, Sibley-Allen C, Allen S, Purushotham A. Intraoperative assessment of tumor resection margins in breast-conserving surgery using 18F-FDG Cerenkov luminescence imaging: a first-in-human feasibility study. J Nucl Med. 2017;58(6):891–898. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.116.181032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Spinelli AE, Ferdeghini M, Cavedon C, Zivelonghi E, Calandrino R, Fenzi A, Sbarbati A, Boschi F. First human cerenkography. J Biomed Opt. 2013;18(2):020502. doi: 10.1117/1.JBO.18.2.020502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu H, Ren G, Liu S, Zhang X, Chen L, Han P, Cheng Z. Optical imaging of reporter gene expression using a positron-emission-tomography probe. J Biomed Opt. 2010;15(6):060505. doi: 10.1117/1.3514659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu H, Carpenter CM, Jiang H, Pratx G, Sun C, Buchin MP, Gambhir SS, Xing L, Cheng Z. Intraoperative imaging of tumors using Cerenkov luminescence endoscopy: a feasibility experimental study. J Nucl Med. 2012;53(10):1579–1584. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.111.098541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xu Y, Chang E, Liu H, Jiang H, Gambhir SS, Cheng Z. Proof-of-concept study of monitoring cancer drug therapy with Cerenkov luminescence imaging. J Nucl Med. 2012;53(2):312–317. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.111.094623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu H, Ren G, Miao Z, Zhang X, Tang X, Han P, Gambhir SS, Cheng Z. Molecular optical imaging with radioactive probes. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(3):e9470. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee SB, Yoon GS, Lee SW, Jeong SY, Ahn BC, Lim DK, Lee J, Jeon YH. Combined positron emission tomography and Cerenkov luminescence imaging of sentinel lymph nodes using PEGylated radionuclide-embedded gold nanoparticles. Small. 2016;12(35):4894–4901. doi: 10.1002/smll.201601721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee SB, Kumar D, Li Y, Lee IK, Cho SJ, Kim SK, Lee SW, Jeong SY, Lee J, Jeon YH. PEGylated crushed gold shell-radiolabeled core nanoballs for in vivo tumor imaging with dual positron emission tomography and Cerenkov luminescent imaging. J Nanobiotechnol. 2018;16(1):1–12. doi: 10.1186/s12951-018-0366-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu H, Zhang X, Xing B, Han P, Gambhir SS, Cheng Z. Radiation-luminescence-excited quantum dots for in vivo multiplexed optical imaging. Small. 2010;6(10):1087–1091. doi: 10.1002/smll.200902408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thorek DLJ, Ogirala A, Beattie BJ, Grimm J. Quantitative imaging of disease signatures through radioactive decay signal conversion. Nat Med. 2013;19(10):1345. doi: 10.1038/nm.3323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zheng S, Zhang Z, Qu Y, Zhang X, Guo H, Shi X, Cai M, Cao C, Hu Z, Liu H, Tian J. Radiopharmaceuticals and fluorescein sodium mediated triple-modality molecular imaging allows precise image-guided tumor surgery. Adv Sci. 2019;6(13):1900159. doi: 10.1002/advs.201900159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Glaser AK, Zhang R, Andreozzi JM, Gladstone DJ, Pogue BW. Cherenkov radiation fluence estimates in tissue for molecular imaging and therapy applications. Phys Med Biol. 2015;60(17):6701. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/60/17/6701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shaffer TM, Drain CM, Grimm J. Optical imaging of ionizing radiation from clinical sources. J Nucl Med. 2016;57(11):1661–1666. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.116.178624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ha SW, Cho HS, Yoon YI, Jang MS, Hong KS, Hui E, Lee JH, Yoon TJ. Ions doped melanin nanoparticle as a multiple imaging agent. J Nanobiotechnol. 2017;15(1):1–9. doi: 10.1186/s12951-017-0304-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu C, Li Z, Hajagos TJ, Kishpaugh D, Chen DY, Pei Q. Transparent ultra-high-loading quantum dot/polymer nanocomposite monolith for gamma scintillation. ACS Nano. 2017;11(6):6422–6430. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.7b02923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cao X, Chen X, Kang F, Zhan Y, Cao X, Wang J, Liang J, Tian J. Intensity enhanced Cerenkov luminescence imaging using terbium-doped Gd2O2S microparticles. ACS Appl Mater Inter. 2015;7(22):11775–11782. doi: 10.1021/acsami.5b00432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ma X, Kang F, Xu F, Fang A, Zhao Y, Lu T, Yang W, Wang Z, Lin M, Wang J. Enhancement of Cerenkov luminescence imaging by dual excitation of Er3+, Yb3+-doped rare-earth microparticles. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(10):e77926. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0077926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hu Z, Qu Y, Wang K, Zhang X, Zha J, Song T, Bao C, Liu H, Wang Z, Wang J, Liu Z, Liu H, Tian J. In vivo nanoparticle-mediated radiopharmaceutical-excited fluorescence molecular imaging. Nat Commun. 2015;6(1):1–12. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hu Z, Zhao M, Qu Y, Zhang X, Zhang M, Liu M, Guo H, Zhang Z, Wang J, Yang W, Tian J. In vivo 3-dimensional radiopharmaceutical-excited fluorescence tomography. J Nucl Med. 2017;58(1):169–174. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.116.180596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hu Z, Chi C, Liu M, Guo H, Zhang Z, Zeng C, Ye J, Wang J, Tian J, Yang W, Xu W. Nanoparticle-mediated radiopharmaceutical-excited fluorescence molecular imaging allows precise image-guided tumor-removal surgery. Nanomed-Nanotechnol. 2017;13(4):1323–1331. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2017.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu N, Shi J, Wang Q, Guo J, Hou Z, Su X, Zhang H, Sun X. In vivo repeatedly activated persistent luminescence nanoparticles by radiopharmaceuticals for long-lasting tumor optical imaging. Small. 2020;16(26):2001494. doi: 10.1002/smll.202001494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu N, Chen X, Sun X, Sun X, Shi J. Persistent luminescence nanoparticles for cancer theranostics application. J Nanobiotechnol. 2021;19(1):1–24. doi: 10.1186/s12951-021-00862-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhou L, Gu Z, Liu X, Yin W, Tian G, Yan L, Jin S, Ren W, Xing G, Li W, Chang X, Hu Z, Zhao Y. Size-tunable synthesis of lanthanide-doped Gd 2 O 3 nanoparticles and their applications for optical and magnetic resonance imaging. J Mater Chem. 2012;22(3):966–974. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pratt EC, Shaffer TM, Zhang Q, Drain CM, Grimm J. Nanoparticles as multimodal photon transducers of ionizing radiation. Nat Nanotechnol. 2018;13(5):418–426. doi: 10.1038/s41565-018-0086-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Alexandre N, Ribeiro J, Gärtner A, Pereira T, Amorim I, Fragoso J, Lopes A, Fernandes J, Costa E, Silva AS, Rodrigues M, Santos JD, Maurício AC, Luis AL. Biocompatibility and hemocompatibility of polyvinyl alcohol hydrogel used for vascular grafting-In vitro and in vivo studies. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2014;102(12):4262–4275. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.35098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hamdalla TA, Hanafy TA. Optical properties studies for PVA/Gd, La, Er or Y chlorides based on structural modification. Optik. 2016;127(2):878–882. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yin J, Wang X, Zheng H, Zhang J, Qu H, Tian L, Zhao F, Shao Y. Silica nanoparticles decorated with gadolinium oxide nanoparticles for magnetic resonance and optical imaging of tumors. ACS Appl Nano Mater. 2021;4(4):3767–3779. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Han C, Xie T, Wang K, Jin S, Li K, Dou P, Yu N, Xu K. Development of fluorescence/MR dual-modal manganese-nitrogen-doped carbon nanosheets as an efficient contrast agent for targeted ovarian carcinoma imaging. J Nanobiotechnol. 2020;18(1):1–15. doi: 10.1186/s12951-020-00736-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hu Zhenhua, Chen Wen-Hua, Tian Jie, Cheng Zhen. NIRF Nanoprobes for Cancer Molecular Imaging: Approaching Clinic. Trends Mol Med. 2020;26(5):469–482. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2020.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hu Z, Fang C, Li B, Zhang Z, Cao C, Cai C, Su S, Sun X, Shi X, Li C, Zhou T, Zhang Y, Chi C, He P, Xia X, Chen Y, Gambhir SS, Cheng Z, Tian J. First-in-human liver tumour surgery guided by multispectral fluorescence imaging in the visible and near-infrared-I/II windows. Nat Biomed Eng. 2020;4(3):259–71. doi: 10.1038/s41551-019-0494-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Figure 1. The optical images with different interaction distances and radioactivity.

Data Availability Statement

The data generated or analyzed during this study are included in the manuscript and the supplementary information files.