Abstract

Background

A significant proportion of newly diagnosed patients with cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (cSCC) have metastasis and eventually die of the disease, necessitating the exploration of novel biomarkers for early detection of cSCC aggressiveness, risk assessment and monitoring. Matrix metalloproteinase-13 (MMP-13) has been implicated in cSCC pathogenesis. Serum MMP-13 levels have been shown to predict survival in patients with esophageal SCC, but their diagnostic value for cSCC has not been explored.

Methods

We conducted a case-control study to examine serum MMP-13 as a biomarker for cSCC. Patients with cSCC undergoing surgical resection and health controls undergoing plastic surgery were recruited. ELISA for measurement of serum MMP-13 and immunohistochemistry for detection of tissue MMP-13 were performed, and the results were compared between the case and the control group, and among different patient groups. ROC curve analysis was performed to determine the diagnostic value of serum MMP-13 levels.

Results

The ratio of male to female, and the age between the case (n = 77) and the control group (n = 50) were not significantly different. Patients had significantly higher serum MMP-13 levels than healthy controls. Subjects with stage 3 cSCC had markedly higher serum MMP-13 levels than those with stage 1 and stage 2 cSCC. Patients with invasive cSCC had remarkably higher serum MMP-13 than those with cSCC in situ. Post-surgery serum MMP-13 measurement was done in 12 patients, and a significant MMP-13 decrease was observed after removal of cSCC. Tumor tissues had a remarkably higher level of MMP-13 than control tissues. Serum MMP-13 predicted the presence of invasive cSCC with an AUC of 0.87 (95% CI [0.78 to 0.95]) for sensitivity and specificity of 81.7 and 82.4%, respectively for a cut-off value of 290 pg/mL. Serum MMP-13 predicted lymph node involvement with an AUC of 0.94 (95% CI [0.88 to 0.99]) for sensitivity and specificity of 93.8 and 88.5%, respectively for a cut-off value of 430 pg/mL.

Conclusion

Serum MMP-13 might serve as a valuable biomarker for early detection of cSCC invasiveness and monitoring of cSCC progression.

Keywords: Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma, Matrix metalloproteinase-13, Biomarker, Metastasis

Background

Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), a family of structurally related proteolytic enzymes, participate in the degradation of various extracellular matrix (ECM) components, e.g., collagen, elastin, fibronectin and gelatin [1, 2]. To date, over 20 MMP members have been identified in humans, which are divided into different subtypes according to their substrate specificity such as collagenase: collagenase-1 (MMP-1), collagenase-2 (MMP-8), collagenase-3 (MMP-13) and collagenase-4 (MMP-18); gelatinase: gelatinase A (MMP-2) and gelatinase B (MMP-9); and stromelysin: stromelysin-1 (MMP-3) and stromelysin-2 (MMP-10) [1]. Through regulation of ECM remodeling, MMPs play an essential role in a wide range of physiological processes, e.g., embryonic development, tissue morphogenesis, reproduction, angiogenesis, and wound healing [3–8]. Dysregulation of MMPs has been found to be involved in diverse pathological conditions including arthritis, fibrosis and neoplasia [9–23].

Cutaneous basal cell carcinoma (cBCC) and cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (cSCC) account for approximately 80 and 20% of nonmelanoma skin cancer (NMSC), respectively [24, 25]. A systematic analysis of the global burden of disease showed that there were 7.7 million incident NMSC cases and sixty-five thousand NMSC deaths worldwide in 2017 [26]. While cBCC is a locally destructive cancer that rarely results in metastasis or death [27], cSCC is the main contributor of NMSC deaths. A number of MMPs including MMP-13 have been implicated in cSCC genesis and development [22, 28, 29]. MMP-13, also termed collagenase-3 responsible for cleavage of fibrillar collagens, gelatin and fibronectin, is not detectable in intact normal skin [30], but its expression has been shown in tumor tissues from patients with cSCC and SCC of the head and neck [30–34]. However, serum MMP-13 as a diagnostic marker for cSCC has not been explored.

Methods

Study subjects

Patients who had cSCC and underwent surgical procedures at our department from March 2016 to March 2019 were recruited. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. Diagnosis of cSCC was confirmed by pathological analysis of excised tumor tissues. Staging of cSCC was done according to the eighth edition of American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) cancer staging system: T1, tumor diameter < 2 cm; T2, tumor diameter ≥ 2 cm and < 4 cm, T3, tumor diameter ≥ 4 cm, or minor bone erosion, or perineural invasion, or deep invasion; T4, tumor with gross cortical bone/bone marrow invasion [35]. Histology typing of invasive cSCC and cSCC in situ, and further subtyping of invasive cSCC into well-differentiated, moderately-differentiated and poorly-differentiated were done at our pathology department. Healthy individuals undergoing cosmetic procedures from the department of plastic surgery were recruited as controls. Patients with other skin disorders, connective tissue disease, renal disease, other tumors, hepatic disease, severe cardiovascular or pulmonary disease were excluded.

Serum preparation

Serum samples were obtained before surgery as follows: after overnight fasting, 10 ml of whole blood from each subject was collected into serum separator tubes which were then left undisturbed at room temperature for 30 min; afterwards, blood samples were centrifuged at 2000 g for 10 min, and the resulting supernatant was collected and frozen at − 80 °C in aliquots until further analysis.

Measurement of MMP-13 by ELISA

Serum MMP-13 was measured using the Human MMP-13 ELISA Kit obtained from Sigma China Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). ELISA was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions with standards and samples run in duplicate. Briefly, 100 μl of each standard and sample were added into appropriate wells of the 96-well ELISA plate and incubated for 2.5 h at room temperature. After 4 washes with the Wash Solution, 100 μl of 1x Detection Antibody was added into each well and incubated for 1 h at room temperature followed by 4 washes with the Wash Solution. Subsequently, 100 μl of Streptavidin solution was added into each well and incubated for 45 min at room temperature followed by 4 washes as described above. Afterwards, 100 μl of TMB One-Step Substrate Reagent was added into each well and incubated for 30 min at room temperature in the dark. Finally, 50 μl of Stop Solution was added into each well, and absorbance at 450 nm of each well was read immediately using a microplate reader (BioTek, Winooski, VT, USA). Sample MMP-13 levels were determined against the concentrations of standards.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

Routine tissue fixation, paraffin-embedding and sectioning, inactivation of endogenous horseradish peroxidase (HRP) and antigen retrieval were performed as described elsewhere [36]. Primary antibody incubation (1:50 dilution of anti-MMP-13 polyclonal antibodies from Boster Biological Technology, Wuhan, China) was done at room temperature for 1 h. After 3 washes with PBS, subsequent secondary antibody incubation and detection were performed using the PV-9000 IHC Kit containing biotinylated anti-rabbit secondary antibody, HRP-labeled-streptavidin, and the substrate diaminobenzidine (Zhongshan Golden Bridge Biotechnology, Beijing, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Hematoxylin was used for counter staining. Under a high power field, the immune-reactive intensity was scored from 0 to 3: 0, no brown color; 1, light brown; 2, brown; and 3, dark brown. The percentage of immune-positive cells over the total cells in a high power field was scored 0–4: 0, < 5%, 1, 5–25%; 2, 26–50%; 3, 51–75% and 4, > 75%. The final immune-score was calculated by multiplying the intensity score and the percentage score, and determined as: < 3, negative; 3–5, weak; 6–8, moderate; and 9–12: strong [36]. All scorings were done by two pathologists in a blind manner and the average immune-score from 10 high power fields for each sample was compared between patients and healthy controls.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis

To determine the diagnostic value of serum MMP-13 levels for the differentiation of invasive cSCC and cSCC in situ, and the detection of cSCC lymph node metastasis, ROC curve analysis was performed using the GraphPad 8.0 statistics software (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA).

Statistical analysis

Data normality was determined by Shapiro-Wilk test. Parametric variables were presented as mean ± standard deviation and non-parametric variables as median (first quartile, third quartile). Unpaired t test for parametric variables or Mann-Whitney test for non-parametric variables was performed to analyze data between two groups of subjects. Serum MMP-13 levels among patients with different stages of cSCC and different histology subtypes (well-differentiated, moderately-differentiated and poorly-differentiated) were analyzed by one way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with post-hoc Tukey test. Categorical data were analyzed by chi-square test. P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed and graphs created using the GraphPad 8.0 statistics software.

Results

A total of 77 patients (49 males and 28 females) and 50 healthy individuals (33 males and 17 females) were included in this study. For patients, fifty-seven cases of cSCC occurred in sun-exposed areas and 20 in the genital areas. The ratio of male to female, and the age in the two groups were not significantly different (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic data of all participants

| Healthy controls (n = 50) | Patients (n = 77) | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender (M/F) | 33/17 | 49/28* |

| Age (years) | 57.1 ± 15.9 | 61.3 ± 15.2# |

* p = 0.79 and # p = 0.14 compared with controls

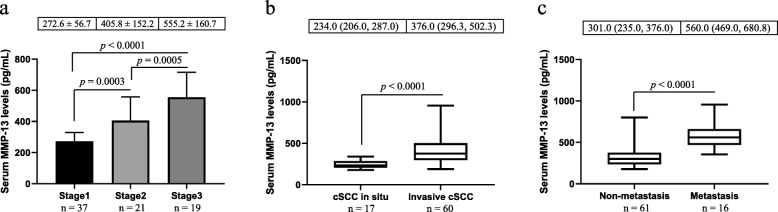

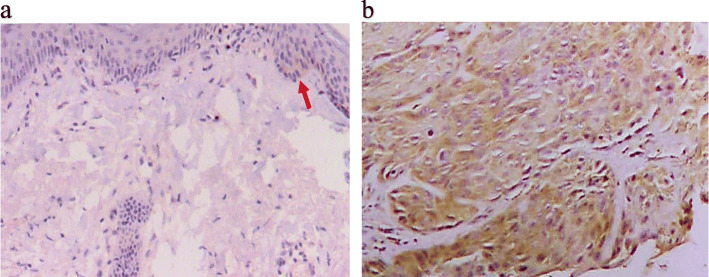

The cSCC group had significantly higher serum MMP-13 levels than the control group (Fig. 1). Furthermore, patients with stage 3 cSCC had markedly higher serum MMP-13 levels than those with stage 1 and stage 2 cSCC, and patients with stage 2 cSCC had substantially higher serum MMP-13 levels than individuals with stage 1 cSCC (Fig. 2 a). However, there was no significant difference in serum MMP-13 levels between healthy controls and patients with stage I cSCC. Histologically, there were 17 cases of cSCC in situ and 60 cases of invasive cSCC, and the latter had remarkably higher serum MMP-13 levels than the former (Fig. 2 b). We did not observe significant difference in serum MMP-13 levels between healthy controls and patients with cSCC in situ. Furthermore, there were no significant differences in serum MMP-13 levels among patients with well-differentiated, moderately-differentiated and poorly- differentiated cSCC (data not shown). Significantly higher levels of serum MMP-13 were also detected in subjects with lymph node metastasis compared with those without lymph node metastasis (Fig. 2 c). Patients with non-metastatic cSCC had significantly higher serum MMP-13 levels than healthy controls (p < 0.001). Post-surgery measurement of serum MMP-13 was performed in 12 patients, which showed a marked decrease of serum MMP-13 concentrations after the removal of cSCC (523.0 ± 231.4 pg/ml prior-surgery versus 296.4 ± 92.6 pg/ml post-surgery, p < 0.001).

Fig. 1.

Comparison of serum MMP-13 levels between patients and healthy controls. As shown in this figure, patients with cSCC had significantly higher serum MMP-13 levels than healthy controls

Fig. 2.

Comparison of serum MMP-13 levels among different groups of patients. Panel a shows the comparative results among patients with different stages of cSCC. Patients with invasive cSCC or lymph node metastasis had substantially higher serum MMP-13 levels than those with cSCC in situ (panel b) or without lymph node involvement (panel c), respectively

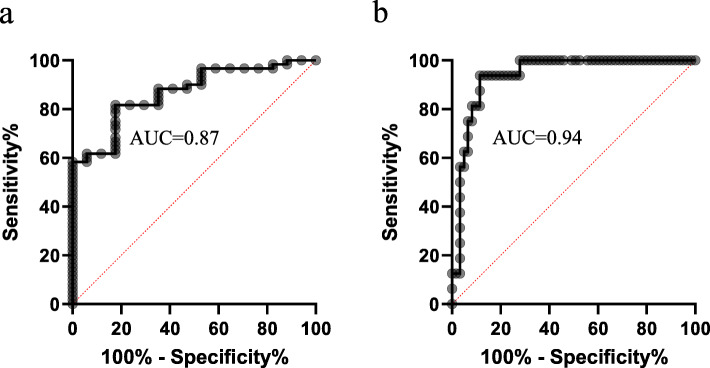

MMP-13 expression in excised samples from all 77 patients and 30 healthy subjects were analysed by IHC. The results showed that negative and weak expression of MMP-13 were detected in 23 and 7 healthy individuals, respectively. In contrast, a significantly higher proportion of patients had positive MMP-13 expression in the resected samples (32 with moderate, 32 with weak and 13 with negative MMP-13 expression, p < 0.01). IHC microphotographs are shown in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Immunohistochemical analysis of MMP-13. IHC analysis of the normal tissue from a healthy subject showed several MMP-13 positive cells (light brown staining indicated by the red arrow in panel a). Panel b is an IHC microphotograph for the cSCC tissue, and brown staining can be seen in most of tumor cells

The age impact on serum MMP-13 levels in patients was examined. Patients were divided into two groups: one group with age < 60 years and the other with age ≥ 60 years. There were no substantial differences in serum MMP-13 levels between these two groups (Table 2). Moreover, the ratio of male to female, and the percent of patients in each stage were not markedly different between the two groups (Table 2).

Table 2.

Comparison of serum MMP-13 levels between different age groups of patients

| < 60 years (n = 29) | ≥ 60 years (n = 48) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| MMP-13 levels (pg/ml) | 304.0 (252.0, 404.5) | 347.5 (271.3, 484.3) | 0.17 |

| T1, n (%) | 15 (51.7%) | 22 (45.8%) | 0.40 |

| T2, n (%) | 7 (24.1%) | 14 (29.2%) | 0.40 |

| T3, n (%) | 7 (24.2%) | 12 (25.0%) | 0.40 |

| Gender (M/F) | 20/9 | 29/19 | 0.45 |

MMP-13 levels were expressed as median (first quartile, third quartile). M: male; and F: female

When serum MMP-13 levels were compared between male and female patients, no significant differences were observed (Table 3). Moreover, the age and the percent of patients in each stage were not significantly different between male and female patients (Table 3).

Table 3.

Comparison of serum MMP-13 levels between female and male patients

| Female (n = 28) | Male (n = 49) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Serum MMP-13 levels (pg/ml) | 373.5 (269.3, 518.5) | 325.0 (264.0, 504.5) | 0.43 |

| T1, n (%) | 13 (46.4%) | 24 (49.0%) | 0.97 |

| T2, n (%) | 8 (28.6%) | 13 (26.5%) | 0.97 |

| T3, n (%) | 7 (25.0%) | 12 (24.5%) | 0.97 |

| Age (years) | 61.9 ± 15.4 | 60.9 ± 15.3 | 0.78 |

Serum MMP-13 levels were presented as median (first quartile, third quartile)

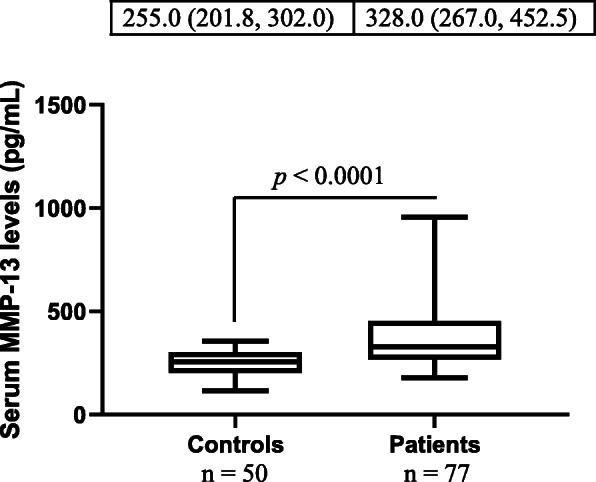

The ROC curve analysis revealed that serum MMP-13 predicted the presence of invasive cSCC with an AUC of 0.87 (95% CI [0.78 to 0.95]) for sensitivity and specificity of 81.7 and 82.4%, respectively for a cut-off value of 290 pg/mL (Fig. 4 a). Serum MMP-13 predicted lymph node involvement with an AUC of 0.94 (95% CI [0.88 to 0.99]) for sensitivity and specificity of 93.8 and 88.5%, respectively for a cut-off value of 430 pg/mL (Fig. 4 b).

Fig. 4.

ROC curve analysis results. ROC curve analysis revealed that serum MMP-13 levels had an AUC of 0.87 and 0.94 for prediction of the presence of invasive cSCC (panel a) and lymph node involvement (panel b), respectively

Discussion

In the present study, we examined the diagnostic value of serum MMP-13 for cSCC, and reported the following findings: 1) patients with cSCC had significantly higher serum MMP-13 levels than healthy controls; 2) the stage of cSCC was associated with the concentration of serum MMP-13; 3) serum MMP-13 possesses high diagnostic value for the differentiation of invasive cSCC and cSCC in situ; 4) serum MMP-13 serves as an excellent diagnostic biomarker for cSCC lymph node metastasis; 5) post-surgery serum MMP-13 measurement was done in 12 patients, and a significant MMP-13 decrease was observed after removal of cSCC; 6) tumor tissues had a remarkably higher level of MMP-13; and 7) age and gender were not related to the elevation of serum MMP-13 levels in patients.

Although surgical resection is effective in the treatment of cSCC, it has been shown that 14% of cSCC cases at the first diagnosis have metastasis and of these patients, 40% will eventually die [37]. Currently, biomarkers that can be used for early detection of cSCC aggressiveness, risk assessment and monitoring are lacking [37–39]. Johansson et al. revealed that MMP-13 mRNA was expressed in head and neck SCC cell lines but not in normal intact skin [30]. The same group also showed that MMP-13 protein was expressed in cSCC tissues as assessed by immunohistochemistry [32]. In another study, Culhaci et al. observed a positive correlation between the degree of immunostaining for MMP-13 in tumor tissues and the invasiveness of tumor in head and neck SCC [33]. These findings suggest that analysis of MMP-13 expression in small biopsy samples may be used to determine the invasive capacity of SCC at an earlier stage. However, an objective method for quantifying MMP-13 or other molecules in SCC tissues for diagnostic purposes has not been reported. It is known that gene dysregulations caused by tumors are often reflected by the changes of final gene products in blood which can be applied for tumor diagnosis [40, 41]. In view of this and the finding of MMP-13 up-regulation in SCC tissues, we sought to explore serum MMP-13 as a diagnostic marker for cSCC, and our results show that serum MMP-13 has high sensitivity and specificity for the differentiation of invasive cSCC and cSCC in situ (Fig. 4 a), and prediction of cSCC lymph node metastasis (Fig. 4 b).

Measurement of serum MMP levels in patients with SCC of different anatomic sites, and comparison of the results with those of healthy controls have been documented [42–50]. Jiao et al. showed that patients with esophageal SCC had significantly higher serum MMP-13 levels than healthy controls; furthermore, serum MMP-13 levels were found to be associated with tumor progression and survival [42]. Riedel et al. discovered the elevation of serum MMP-9 levels in patients with head and neck SCC [43], which is also observed by Stanciu et al. [44]. Lotfi et al. reported that both serum MMP-2 and MMP-9 levels were significantly increased in laryngeal SCC cases compared with healthy controls [45], and similar results were depicted by Matulka et al. and Grzelczyk et al. [46, 47]. Choudhry et al. revealed that serum levels of MMP-1, − 8, − 10, − 12 and − 13 in oral SCC patients were substantially elevated as compared with healthy controls [48]. In contrast, Ghallab showed the increase of serum MMP-9 in oral SCC patients compared with subjects with oral premalignant lesions [49]. Among all these studies, only two groups examined the diagnostic value of MMPs: using the ROC analysis, Ghallab showed serum MMP-9 with an AUC of 0.6, which failed to differentiate between oral SCC and oral premalignant lesions [49]. Of note, serum MMP-12 was shown to have an AUC of 0.84 for sensitivity and specificity of 80 and 78.9%, respectively for a cut-off value of 16.13 pg/ml for the diagnosis of oral SCC [48]. These data together with ours suggest that serum MMPs may serve as potential biomarkers for SCC diagnosis.

We discovered that serum MMP-13 is a valuable biomarker in prediction of cSCC lymph node metastasis (Fig. 4 b). However, discrepancy in relationship between serum MMP levels and lymph node involvement has been presented [42, 44, 50]. While no significant correlations were proven between serum MMP-1, − 2, and − 9 concentrations and lymph node status in head and neck SCC [50], serum MMP-2 was found to be correlated with lymph node involvement in laryngeal SCC [45], and serum MMP-13 levels were associated with esophageal SCC lymph node metastasis [42]. These disagreeing results may be attributed to: 1) heterogeneity of SCC studied and 2) small sample sizes explored.

MMP-13 elevation in SCC cell lines or tissues has been described in several studies. Johansson et al. showed that while MMP-13 mRNA was highly expressed in head and neck SCC cell lines, it is undetectable in normal skin tissues [30]. Elevated MMP-13 mRNA expression was also observed in head and neck SCC tissues [34]. In agreement with these mRNA data, increased MMP-13 protein production in head and neck SCC tissues was detected by IHC [33]. In the present study, we found a significantly higher level of MMP-13 in cSCC tissues compared with control tissues. Moreover, serum MMP-13 substantially decreased after the resection of cSCC. These results suggest tumor-derived MMP-13 contributes to the elevation of serum MMP-13 seen in our patients.

In this study, the impact of sex and age on serum MMP-13 levels was not observed in patients, which has also been reported in SCC of different sites by other studies [42, 50]. Serum MMP-13 levels were found to be uncorrelated with age and gender in patients with esophageal SCC [42]. A study that analyzed serum levels of MMP-1, − 2, and − 9 in patients with head and neck SCC did not show correlations between serum MMP levels and sex or age [50].

Conclusions

Serum MMP-13 levels show high sensitivity and specificity for the differentiation of invasive cSCC and cSCC in situ, and the prediction of lymph node metastasis, suggesting serum MMP-13 might serve as a valuable biomarker for early detection of cSCC invasiveness and monitoring of cSCC progression.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Authors’ contributions

YS conceived the study. YS, HW, HL and QY designed the study. HW and ZW performed all experiments. SG and JG performed all pathological analyses. HL and QY performed statistical analyses and interpreted the results. HW drafted the manuscript. YS critically revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the Weifang Municipal Health and Family Planning Commission Science and Technology Project (grant No: 2016wsjs024) and the Weifang Municipal Science and Technology Development Project (grant No: 2019YX007).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Medical Research Review Committee of Weifang People’s Hospital (Approval No.: 2016-3-10). Informed consent was obtained from all participants. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Laronha H, Caldeira J. Structure and function of human matrix metalloproteinases. Cells. 2020;9(5):1076. doi: 10.3390/cells9051076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cui N, Hu M, Khalil RA. Biochemical and biological attributes of matrix metalloproteinases. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci. 2017;147:1–73. doi: 10.1016/bs.pmbts.2017.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tomlinson ML, Garcia-Morales C, Abu-Elmagd M, Wheeler GN. Three matrix metalloproteinases are required in vivo for macrophage migration during embryonic development. Mech Dev. 2008;125(11–12):1059–1070. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2008.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ethell IM, Ethell DW. Matrix metalloproteinases in brain development and remodeling: synaptic functions and targets. J Neurosci Res. 2007;85(13):2813–2823. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ortega N, Behonick DJ, Colnot C, Cooper DN, Werb Z. Galectin-3 is a downstream regulator of matrix metalloproteinase-9 function during endochondral bone formation. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16(6):3028–3039. doi: 10.1091/mbc.e04-12-1119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dubois B, Arnold B, Opdenakker G. Gelatinase B deficiency impairs reproduction. J Clin Invest. 2000;106(5):627–628. doi: 10.1172/JCI10910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rundhaug JE. Matrix metalloproteinases and angiogenesis. J Cell Mol Med. 2005;9(2):267–285. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2005.tb00355.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mohan R, Chintala SK, Jung JC, Villar WV, McCabe F, Russo LA, Lee Y, McCarthy BE, Wollenberg KR, Jester JV, Wang M, Welgus HG, Shipley JM, Senior RM, Fini ME. Matrix metalloproteinase gelatinase B (MMP-9) coordinates and effects epithelial regeneration. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(3):2065–2072. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107611200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Rooy DP, Zhernakova A, Tsonaka R, Willemze A, Kurreeman BA, Trynka G, van Toorn L, Toes RE, Huizinga TW, Houwing-Duistermaat JJ, Gregersen PK, van der Helm-van Mil AH. A genetic variant in the region of MMP-9 is associated with serum levels and progression of joint damage in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73(6):1163–1169. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-203375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Peake NJ, Khawaja K, Myers A, Jones D, Cawston TE, Rowan AD, Foster HE. Levels of matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-1 in paired sera and synovial fluids of juvenile idiopathic arthritis patients: relationship to inflammatory activity, MMP-3 and tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-1 in a longitudinal study. Rheumatology. 2005;44(11):1383–1389. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kei025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vincenti MP, Brinckerhoff CE. Transcriptional regulation of collagenase (MMP-1, MMP-13) genes in arthritis: integration of complex signaling pathways for the recruitment of gene-specific transcription factors. Arthritis Res. 2002;4(3):157–164. doi: 10.1186/ar401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Giannandrea M, Parks WC. Diverse functions of matrix metalloproteinases during fibrosis. Dis Model Mech. 2014;7(2):193–203. doi: 10.1242/dmm.012062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Duarte S, Baber J, Fujii T, Coito AJ. Matrix metalloproteinases in liver injury, repair and fibrosis. Matrix Biol. 2015;44–46:147–156. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2015.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pardo A, Cabrera S, Maldonado M, Selman M. Role of matrix metalloproteinases in the pathogenesis of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Respir Res. 2016;17(1):23. doi: 10.1186/s12931-016-0343-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Egeblad M, Werb Z. New functions for the matrix metalloproteinases in cancer progression. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2(3):161–174. doi: 10.1038/nrc745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fukushima R, Kasamatsu A, Nakashima D, Higo M, Fushimi K, Kasama H, Endo-Sakamoto Y, Shiiba M, Tanzawa H, Uzawa K. Overexpression of translocation associated membrane protein 2 leading to cancer-associated matrix metalloproteinase activation as a putative metastatic factor for human oral cancer. J Cancer. 2018;9(18):3326–3333. doi: 10.7150/jca.25666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yu D, Ye T, Xiang Y, Shi Z, Zhang J, Lou B, Zhang F, Chen B, Zhou M. Quercetin inhibits epithelial-mesenchymal transition, decreases invasiveness and metastasis, and reverses IL-6 induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition, expression of MMP by inhibiting STAT3 signaling in pancreatic cancer cells. Onco Targets Ther. 2017;10:4719–4729. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S136840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mehner C, Hockla A, Miller E, Ran S, Radisky DC, Radisky ES. Tumor cell-produced matrix metalloproteinase 9 (MMP-9) drives malignant progression and metastasis of basal-like triple negative breast cancer. Oncotarget. 2014;5(9):2736–2749. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.1932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hsu CC, Huang SF, Wang JS, Chu WK, Nien JE, Chen WS, Chow SE. Interplay of N-cadherin and matrix metalloproteinase 9 enhances human nasopharyngeal carcinoma cell invasion. BMC Cancer. 2016;16(1):800. doi: 10.1186/s12885-016-2846-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Said AH, Raufman JP, Xie G. The role of matrix metalloproteinases in colorectal cancer. Cancers. 2014;6(1):366–375. doi: 10.3390/cancers6010366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee EJ, Lee SJ, Kim S, Cho SC, Choi YH, Kim WJ, Moon SK. Interleukin-5 enhances the migration and invasion of bladder cancer cells via ERK1/2-mediated MMP-9/NF-κB/AP-1 pathway: involvement of the p21WAF1 expression. Cell Signal. 2013;25(10):2025–2038. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2013.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ala-aho R, Ahonen M, George SJ, Heikkilä J, Grénman R, Kallajoki M, Kähäri VM. Targeted inhibition of human collagenase-3 (MMP-13) expression inhibits squamous cell carcinoma growth in vivo. Oncogene. 2004;23(30):5111–5123. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.O'Grady A, Dunne C, O'Kelly P, Murphy GM, Leader M, Kay E. Differential expression of matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-2, MMP-9 and tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase (TIMP)-1 and TIMP-2 in non-melanoma skin cancer: implications for tumour progression. Histopathology. 2007;51(6):793–804. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2007.02885.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tanese K, Nakamura Y, Hirai I, Funakoshi T. Updates on the systemic treatment of advanced non-melanoma skin cancer. Front Med. 2019;6:160. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2019.00160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Burton KA, Ashack KA, Khachemoune A. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: a review of high-risk and metastatic disease. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2016;17(5):491–508. doi: 10.1007/s40257-016-0207-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Global Burden of Disease Cancer Collaboration. Fitzmaurice C, Abate D, et al. Global, regional, and national cancer incidence, mortality, years of life lost, years lived with disability, and disability-adjusted life-years for 29 cancer groups, 1990 to 2017: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study. JAMA Oncol. 2019;5(12):1749–1768. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.2996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wysong A, Aasi SZ, Tang JY. Update on metastatic basal cell carcinoma: a summary of published cases from 1981 through 2011. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149(5):615–616. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2013.3064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.D'Armiento J, DiColandrea T, Dalal SS, Okada Y, Huang MT, Conney AH, Chada K. Collagenase expression in transgenic mouse skin causes hyperkeratosis and acanthosis and increases susceptibility to tumorigenesis. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15(10):5732–5739. doi: 10.1128/MCB.15.10.5732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Coussens LM, Tinkle CL, Hanahan D, Werb Z. MMP-9 supplied by bone marrow-derived cells contributes to skin carcinogenesis. Cell. 2000;103(3):481–490. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)00139-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Johansson N, Airola K, Grenman R, Kariniemi AL, Saarialho-Kere U, Kahari VM. Expression of collagenase-3 (matrix metalloproteinase-13) in squamous cell carcinomas of the head and neck. Am J Pathol. 1997;151(2):499–508. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pendas A, Uria JA, Jimenez MG, Balbin M, Freije JP, Lopez-Otin C. An overview of collagenase-3 expression in malignant tumors and analysis of its potential value as a target in antitumor therapies. Clin Chim Acta. 2000;291(2):137–155. doi: 10.1016/S0009-8981(99)00225-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Johansson N, Vaalamo M, Grénman S, Hietanen S, Klemi P, Saarialho-Kere U, Kähäri VM. Collagenase-3 (MMP-13) is expressed by tumor cells in invasive vulvar squamous cell carcinomas. Am J Pathol. 1999;154(2):469–480. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65293-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Culhaci N, Metin K, Copcu E, Dikicioglu E. Elevated expression of MMP-13 and TIMP-1 in head and neck squamous cell carcinomas may reflect increased tumor invasiveness. BMC Cancer. 2004;4(1):42. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-4-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stokes A, Joutsa J, Ala-Aho R, Pitchers M, Pennington CJ, Martin C, Premachandra DJ, Okada Y, Peltonen J, Grénman R, James HA, Edwards DR, Kähäri VM. Expression profiles and clinical correlations of degradome components in the tumor microenvironment of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16(7):2022–2035. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-2525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Amin MB, Greene FL, Edge SB, Compton CC, Gershenwald JE, Brookland RK, Meyer L, Gress DM, Byrd DR, Winchester DP. The eighth edition AJCC Cancer staging manual: continuing to build a bridge from a population-based to a more “personalized” approach to cancer staging. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67(2):93–99. doi: 10.3322/caac.21388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim SW, Roh J, Park CS. Immunohistochemistry for pathologists: protocols, pitfalls, and tips. J Pathol Transl Med. 2016;50(6):411–418. doi: 10.4132/jptm.2016.08.08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Voiculescu V, Calenic B, Ghita M, Lupu M, Caruntu A, Moraru L, Voiculescu S, Ion A, Greabu M, Ishkitiev N, Caruntu C. From normal skin to squamous cell carcinoma: a quest for novel biomarkers. Dis Markers. 2016;2016:4517492. doi: 10.1155/2016/4517492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lazar AD, Dinescu S, Costache M. Deciphering the molecular landscape of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma for better diagnosis and treatment. J Clin Med. 2020;9(7):2228. doi: 10.3390/jcm9072228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kivisaari A, Kähäri VM. Squamous cell carcinoma of the skin: emerging need for novel biomarkers. World J Clin Oncol. 2013;4(4):85–90. doi: 10.5306/wjco.v4.i4.85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Maruvada P, Wang W, Wagner PD, Srivastava S. Biomarkers in molecular medicine: cancer detection and diagnosis. Biotechniques. 2005;Suppl:9–15. doi: 10.2144/05384SU04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yeo JC, Lim CT. Potential of circulating biomarkers in liquid biopsy diagnostics. Biotechniques. 2018;65(4):187–189. doi: 10.2144/btn-2018-0093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jiao XL, Chen D, Wang JG, Zhang KJ. Clinical significance of serum matrix metalloproteinase-13 levels in patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2014;18(4):509–515. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Riedel F, Götte K, Schwalb J, Hörmann K. Serum levels of matrix metalloproteinase-2 and -9 in patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Anticancer Res. 2000;20(5A):3045–3049. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stanciu AE, Zamfir-Chiru-Anton A, Stanciu MM, Popescu CR, Gheorghe DC. Serum level of matrix metalloproteinase-9 in patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Clin Lab. 2016;62(8):1569–1574. doi: 10.7754/Clin.Lab.2016.160139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lotfi A, Mohammadi G, Saniee L, Mousaviagdas M, Chavoshi H, Tavassoli A. Serum level of matrix metalloproteinase-2 and -9 in patients with laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma and clinical significance. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2015;16(15):6749–6751. doi: 10.7314/APJCP.2015.16.15.6749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Matulka M, Konopka A, Mroczko B, Pryczynicz A, Kemona A, Groblewska M, Sieskiewicz A, Olszewska E. Expression and concentration of matrix metalloproteinase 9 and tissue inhibitor of matrix metalloproteinases 1 in laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Dis Markers. 2019;2019:3136792. doi: 10.1155/2019/3136792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Grzelczyk WL, Wróbel-Roztropiński A, Szemraj J, Cybula M, Pietruszewska W, Zielińska-Kaźmierska B, Jozefowicz-Korczynska M. Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and inhibitor of metalloproteinases (TIMP) mRNA and protein expression in laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Arch Med Sci. 2019;15(3):784–791. doi: 10.5114/aoms.2017.72405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Choudhry N, Sarmad S, Waheed NUA, Gondal AJ. Estimation of serum matrix metalloproteinases among patients of oral squamous cell carcinoma. Pak J Med Sci. 2019;35(1):252–256. doi: 10.12669/pjms.35.1.68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ghallab NA, Shaker OG. Serum and salivary levels of chemerin and MMP-9 in oral squamous cell carcinoma and oral premalignant lesions. Clin Oral Investig. 2017;21(3):937–947. doi: 10.1007/s00784-016-1846-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kalfert D, Ludvikova M, Topolcan O, Windrichova J, Malirova E, Pesta M, Celakovsky P. Analysis of preoperative serum levels of MMP-1, −2, and −9 in patients with site-specific head and neck squamous cell cancer. Anticancer Res. 2014;34(12):7431–7441. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article.