Abstract

Background

Mask wearing has varied considerably throughout the COVID-19 pandemic and has been most often associated with political affiliation and specific health beliefs. The purpose of this study was to determine the relationship between mask usage, neighborhood racial segregation, and racial disparities in COVID-19 deaths.

Methods

We used linear regression to assess whether the racial/ethnic composition of deaths and residential segregation predicted Americans’ decisions to wear masks in July 2020.

Results

After controlling for mask mandates, mask usage increased when White death rates relative to Black and Hispanic rates increased.

Conclusions

Mask wearing may be shaped by an insensitivity to Black and Hispanic deaths and a corresponding unwillingness to engage in health-protective behaviors. The broader history of systemic racism and residential segregation may also explain why white Americans do not wear masks or perceive themselves to be at risk when communities of color are disproportionately affected by COVID-19.

Keywords: Racism, Racial bias, COVID-19, Health equity

Background

Nationally available data from the CDC and other sources reveal that Black and Latinx Americans account for a disproportionate number of COVID-19-related cases, hospitalizations, and deaths [1–4]. A vast and growing body of research suggests that racial disparities in mortality are associated with underlying differences in comorbidities that are shaped by the influence of structural racism and access to health care [5, 6]. Because COVID-19 is a novel coronavirus, the public, elected officials, and even scientists are continually learning how to mitigate its devastating impact. While the learning curve may be slow in some ways, there is widespread scientific agreement regarding the use of facial coverings to slow, if not prevent the spread. By mid-July 2020, masks were mandatory in 21 states, with more states considering the adoption of such policies [7]. Yet, mask usage in the USA has proved controversial and selectively adopted. In June of 2020, for example, a national poll found that less than two-thirds of Americans agreed that it was important to wear a mask [8] and only a slightly higher percentage (73%) of Americans stated that they had worn a mask in a public setting [9].

From national polls and peer-reviewed studies conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic, we have learned important correlates of mask usage in the context of a novel respiratory pathogen. Researchers have focused primarily on political affiliation, finding that voting patterns and exposure to misinformation predict adherence to public health guidance regarding masks [8, 10]. Other studies have extended this work, finding that political affiliation is associated with the usage of specific news sources and different levels of knowledge and beliefs related to COVID-19 [11], including mask wearing and efforts to socially distance [12]. Further contributing to uneven mask usage is a significant amount of misinformation circulating regarding the effectiveness of masks, creating what public health experts have called an “infodemic” [13]. Given evidence that masks are an important part of public health efforts to mitigate COVID-19 transmission, research is necessary to understand additional factors that are associated with decisions to adopt this recommendation.

Few studies have explored other social or cultural factors that underlie mask usage, especially considering the continued severity of the pandemic and striking racial/ethnic disparities in COVID-19 infections and outcomes. It is important for researchers, accordingly, to understand when and in what contexts Americans feel compelled to wear masks specifically and follow public health guidance more generally. It is possible, for example, that reasons for refusing to wear a mask may extend beyond political affiliation and exposure to misinformation and differ by race or ethnicity. While a key concern for white Americans who do not wear masks is that mandates infringe on their civil rights [13], there may exist a mask conundrum for Black Americans. After mask requirements were implemented across the country, several news outlets featured stories highlighting the concerns of Black communities regarding the risk of police profiling of Black men wearing face coverings [14–16]. By early June, multiple accounts of Black men targeted for wearing masks—and for not wearing masks—were documented across the country [17]. This lose-lose scenario is captured by the statement of Aaron Thomas, an educator in Ohio: “I want to stay alive but I also want to stay alive” [18]. At the same time, survey data showed that Black and Hispanic Americans were more likely than white Americans to report concern that they would require hospitalization from COVID or unknowingly spread the disease to others, supporting mask wearing among these populations [19]. This evidence suggests that factors other than political affiliation may be important correlates of mask usage.

Because COVID-19 death rates are twice as high among Black Americans in the USA [20], it is possible that mask wearing reflects different perceptions of risk related to COVID-19 exposure and outcomes. More specifically, because American communities continued to be segregated by race [21], white Americans may feel less vulnerable to COVID-19 because fewer individuals in their close proximity may have become infected or have been killed by this novel illness. It is important, accordingly, to consider whether different types of racism, especially residential segregation, are associated with mask usage among white Americans. There is compelling evidence that contemporary forms of racism such as color-blind racism or racial apathy are present in more than half of white Americans [22, 23] and may help perpetuate residential segregation through opposition to policies that advance racial equity [24, 25]. We ask, therefore, whether white Americans wear masks as often when Black, as opposed to white Americans, are dying at higher rates in the surrounding state. According to prominent pediatrician, public health advocate, and scholar Rhea Boyd, “opposition to public health interventions, like masking, have also become a material manifestation of America’s racism, particularly anti-Black racism” [26]. To test this, we assess whether mask usage among white Americans is associated with who is dying from COVID-19 in the surrounding community. To our knowledge, this is the first study to quantitatively examine how mask usage relates to differential outcomes in COVID-19 deaths by race.

Methods

Data

Our data on mask usage, demographic factors, mask mandates, and COVID-19 death rate disparities come from multiple sources. Mask wearing reflects the percentage of state residents who report wearing a mask whenever they are in public and was measured by the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation at the University of Washington [27]. State mask mandate indicates whether a state-level mask wearing mandate had been adopted as of July 20, 2020 [28]. Racial segregation data is from 2013 to 2015 and is based on a dissimilarity index, produced by the US Census Bureau where Black-White segregation levels range from 0 to 100, with 100 being the most spatially segregated by race [29].

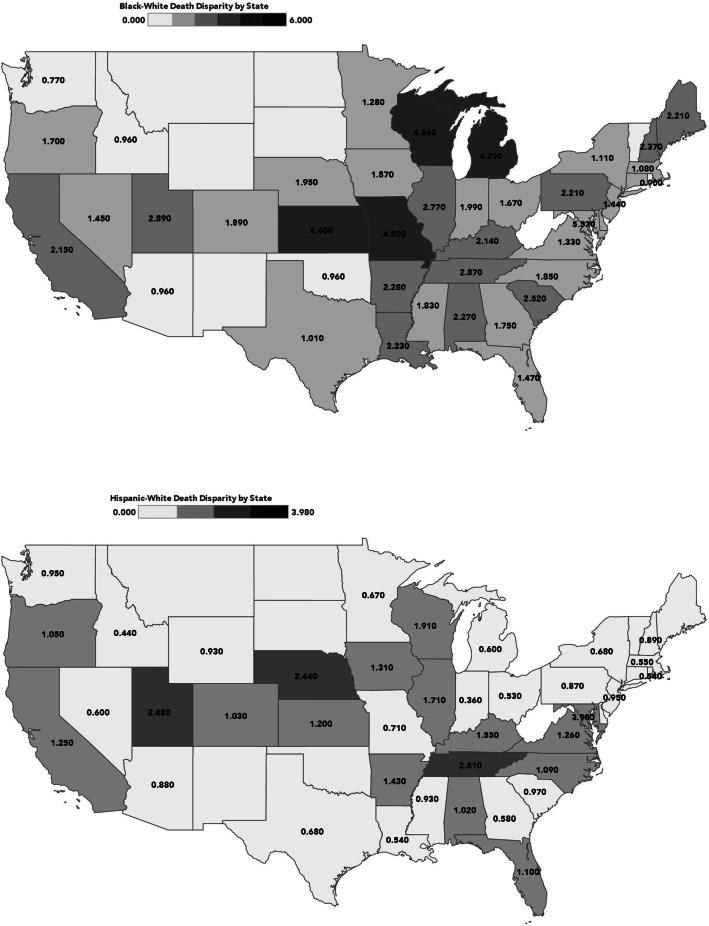

Our focal independent variables are Black-White and Hispanic-White disparities in racial death rates which included 45 states with available data. To construct indices of racial disparities in COVID-19 deaths, we draw on data from the Kaiser Family Foundation’s State COVID Racial Data Tracker [30] including COVID-19 deaths through July 21, 2020. The racial death disparity index reflects the ratio of Black or Hispanic death rates to White death rates in each state (Black or Hispanic deaths divided by White deaths). If the death rates for Blacks or Hispanics in a particular state are identical to the death rate for Whites, the racial death disparity index will equal 1.0. Racial death disparity index values less than 1.0 indicate that Blacks (or Hispanics) are underrepresented relative to Whites while values greater than unity would indicate that Blacks (or Hispanics) are overrepresented in a state’s COVID-19 death counts. Table 1 reports disproportionate COVID-19 deaths by race and Figure 1 demonstrates the geographic pattern of disparities.

Table 1.

State-level racial (Black-White and Hispanic-White) disparities in COVID-19 deaths

| State | Black-White Death disparity | Hispanic-White Death disparity |

|---|---|---|

| AK | -- | -- |

| AL | 2.27 | 1.02 |

| AR | 2.28 | 1.43 |

| AZ | .96 | .88 |

| CA | 2.15 | 1.25 |

| CO | 1.89 | 1.03 |

| CT | 1.36 | .48 |

| DC | 5.53 | 3.98 |

| DE | 1.22 | .66 |

| FL | 1.47 | 1.10 |

| GA | 1.75 | .58 |

| IA | 1.87 | 1.31 |

| ID | .96 | .44 |

| IL | 2.77 | 1.71 |

| IN | 1.99 | .36 |

| KS | 4.40 | 1.20 |

| KY | 2.14 | 1.55 |

| LA | 2.23 | .54 |

| MA | 1.08 | .55 |

| MD | 1.60 | 1.28 |

| ME | 2.21 | -- |

| MI | 4.29 | .60 |

| MN | 1.28 | .67 |

| MO | 4.50 | .71 |

| MS | 1.83 | .93 |

| NC | 1.85 | 1.09 |

| NE | 1.95 | 2.44 |

| NH | 2.37 | .89 |

| NJ | 1.44 | .95 |

| NV | 1.45 | .60 |

| NY | 1.11 | .68 |

| OH | 1.67 | .53 |

| OK | .96 | -- |

| OR | 1.70 | 1.05 |

| PA | 2.21 | .87 |

| RI | .90 | .54 |

| SC | 2.52 | .97 |

| TN | 2.87 | 2.51 |

| TX | 1.01 | .68 |

| UT | 2.89 | 2.48 |

| VA | 1.33 | 1.26 |

| VT | -- | -- |

| WA | .77 | .95 |

| WI | 4.86 | 1.91 |

| WY | .00 | .93 |

| Total | 44 | 44 |

States with Black/Hispanic overrepresentation (disparity index >1.00) highlighted in bold

Fig. 1.

Racial/ethnic disparity levels by state

While racial disparity levels vary, the index for Black-White death exceeds 1.0 in 36 states; the index for Hispanic-White death exceeds 1.0 in 18 states.

Results

Table 2 provides descriptive statistics for all analysis variables. The focal outcome measure—state mask wearing—shows considerable variation in the percentage of respondents who report wearing masks every time they are in public (mean = 4.22; S.D = 1.33). Our primary predictor variables—racial disparities in COVID-19 deaths—vary widely across the states: Black-White disparities (mean = 1.92; S.D = 1.07) exceed Hispanic-White disparities (mean = .97; S.D = .59). State policies regarding mask mandates also vary (mean = .279; S.D = .454) with slightly more than one-quarter of states having adopted mandates in some form. Racial segregation levels are relatively high (mean = 58.17; S.D = 11.71), but vary considerably across states and range from 37 to 78 in our sample.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics for analysis variables

| Variable | Mean | S.D |

|---|---|---|

| Mask-wearing practices | 4.28 | 1.399 |

| Mask mandates | .279 | .454 |

| Black-White Death disparities | 1.915 | 1.068 |

| Hispanic-White Death disparities | .968 | .589 |

| Segregation index | 58.168 | 11.706 |

The regression models in Table 3 examine [1] the degree to which differences in COVID-19 deaths by race predict mask wearing; [2] this same prediction after adjusting for the presence of a mask mandate; and [3] this same prediction with the addition of mask mandates and state-level racial segregation; as such, the primary predictor of interest in these models was a disparity in racial/ethnic death rates.

Table 3.

Mask wearing and state racial death disparities

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Black-White | Hispanic-White | Black-White | Hispanic-White | Black-White | Hispanic-White | |

| Racial death disparities | −.361†, .197 | −.888***, .348 | −.279†, .155 | −.587*, .287 | −.152, .165 | −.446†, .280 |

| State mask law, 1=yes | 1.890***, .364 | 1.755***, .373 | 2.083***, .369 | 1.994***, .370 | ||

| Segregation index | −.030†, .016 | −.033*, .014 | ||||

| Constant | 4.95***, .430 | 5.14***, .390 | 4.263***, .361 | 4.36***, .357 | 5.752***, .885 | 6.13***, .845 |

| Adj. R2 | .054 | .118 | .420 | .418 | .453 | .474 |

†p≤ .10; *p≤ .05; **p≤ .01; ***p≤ .001

The results reported in model 1 examine the association between state mask-wearing practices and race-specific death rate disparities. Results in the first column show that Black-White COVID-19 death rate disparities are marginally inversely related (b=−.361, p <.10) to self-reported mask usage. Residents in states with greater Black-White COVID-19 death disparities report lower levels of mask wearing compared to states with lower disparities. Results in the second column of model 1 show that deaths from COVID-19 among Hispanic populations are strongly inversely related (b=−.888, p <.001) to self-reported mask usage. Both Black (Adj. R2 = .054) and Hispanic (Adj. R2 = .118) COVID-19 death rates account for a significant share of the variance in model 1.

The results reported in model 2, which examines the association between state mask-wearing practices and race-specific death rate disparities, with controls for state mask mandates, show that this relationship is reduced but remains significant with regard to both Black-White and Hispanic-White death rate disparities. Black-White death rate disparities are marginally inversely associated (b=−.279, p <.10) with state mask-wearing practices while Hispanic-White death rate disparities are moderately inversely associated (b=−.587, p <.05) with state mask-wearing practices. Thus, even in states with mask mandates, residents in states with higher racial disparities in COVID-19-related deaths report lower levels of mask wearing compared to residents in states with smaller disparities in Black-White and Hispanic-White COVID-19-related deaths. Not surprisingly, the addition of the state mask mandate measure in model 2 substantially increases the variance accounted for in both the Black-White (Adj. R2 = .420) and Hispanic-White (Adj. R2 = .418) equations.

The results reported in the full model (model 4) examining the association between state mask-wearing practices and race-specific death rate disparities, with controls for mask mandates, also include a segregation index as a proxy measure of a state’s structural racial inclusivity. Segregation appears to substantially mediate the relationship between state mask-wearing practices and Black-White death rate disparities, and to partially mediate the relationship between state mask-wearing practices and Hispanic-White death rate disparities. When racial segregation (dissimilarity index) is included in the full model, the Black-White death rate disparity measure is no longer significantly associated with state mask-wearing practices. In contrast, including racial segregation in the full model reduces, but does not eliminate, the association (b=−.446, p <.10) between state mask-wearing practices and Hispanic-White death rate disparities. The inclusion of the segregation measure in model 3 modestly increases the variance accounted for in both the Black-White (Adj. R2 = .453) and Hispanic-White (Adj. R2 = .474) equations. Mask mandates are clearly the most important determinant of state mask-wearing practices in our analyses.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to understand additional factors that underlie patterns of mask wearing in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic in the USA. Mask wearing has emerged as a cornerstone of the public health approach to mitigating new infections and deaths from the disease. Still, mask wearing in the USA is uneven and previous studies have mostly focused on the role that political affiliation and ideology play in shaping adherence to this public health recommendation. We explored whether self-reported mask usage in a state is related to COVID-19 death disparities in states, which may serve as a proxy for the level of risk that exists.

Our findings suggest that the percentage of individuals who wear masks is associated with those who are dying from COVID-19 in the state. After controlling for mask mandates, which aim to increase adherence to public health guidelines, mask usage increased when the White death rates relative to Black and Hispanic rates increased. Conversely, individuals wear masks less frequently when Black and Hispanic death rates relative to White death rates are higher. There are two plausible interpretations of these findings that may provide support for two complementary models of how racism shapes COVID-19 outcomes: [1] that Americans do not perceive themselves to be at risk when people of color are dying because US communities are highly segregated by race and [2] because many Americans endorse racial apathy, or at a minimum harbor unconscious implicit biases, they may therefore be less concerned about Black or Hispanic deaths.

Residential segregation persists in the USA as a legacy of institutionalized racism. Many studies document the impact of segregation on wealth accumulation and numerous acute and chronic health conditions such as hypertension, asthma, and infant mortality [31–34]. Residential segregation may shape COVID-19 disparities insofar as chronic diseases, which disproportionately affect Americans of color, and increase vulnerability to morbidity and mortality from COVID-19. But the effects of residential segregation may go even further in damaging public health. If severe and fatal cases of COVID-19 are concentrated in communities of color where many White Americans are not exposed to the severe threat posed by this disease, individuals may be less likely to adopt public health practices, such as mask wearing. Indeed, we find in our study that when controlling for the level of residential segregation in a state, this factor at least partially helps us understand why mask usage may be lower when Black-White and Hispanic-White death rate disparities are more pronounced in a state.

Still, there are likely other factors that are important to consider. In particular, we focus on the persistence of systemic racism, but are unable to directly measure other forms of racism such as racial apathy, or an ambivalence toward policies that are perceived as disproportionately aimed at helping Black or Hispanic Americans [35, 36]. Although this framework has been used to explain support for policies that explicitly focus on racial advancement such as affirmative action, we argue that mask wearing may also be perceived as a race-based policy when deaths are disproportionately concentrated among Black and Hispanic Americans and other people of color. Although our data do not allow us to test this relationship, future research should explore whether racial apathy in particular may be reflected in an insensitivity to Black and Hispanic deaths and a corresponding unwillingness to engage in health-protective behaviors such as mask usage.

Our study has several limitations that are important to consider. First, our use of cross-sectional data does not allow us to assess causality in patterns of mask usage. Second, our use of state-level data does not provide insight into individual factors that shape mask usage. Finally, we present data from July 2020 when mask usage still varied considerably across the USA [37]. Mask usage continued to rise after this point [38] and as a result varied less between social groups. In addition, the patterns for Black-White and Hispanic-White disparities reflect the specific time period covered in our study. The differences found for Blacks and Hispanics likely reflect the fact that during the early summer of 2020, the eastern and southern states where Black Americans are more concentrated (compared to Hispanics) were also locations where the virus spread most rapidly. As such, patterns of racial disparities changed as different regions of the USA were affected in the third surge of COVID-19 during winter of 2021.

Conclusions

Public health scholars and practitioners have been active in recent years in demonstrating the pernicious effects of racism on public health. Most of this focus has been on structural racism and its impact on numerous social determinants of health. Our study provides evidence that the persistence of anti-Black and anti-Hispanic attitudes in the USA must be included in efforts to identify and address racism in the USA. These attitudes not only shape support for policies that stand to redress long-standing racial/ethnic health disparities [39, 40], but may also help us understand resistance to public health measures, such as mask wearing, during the COVID-19 pandemic. Disparities in morbidity and mortality in the context of the novel coronavirus pandemic have brought to the forefront a much older and more enduring public health crisis: racial discrimination. Exploring and addressing the structural and individual context of racism in the USA will help us improve public health and better prepare for the public health challenges to come.

Acknowledgments

Availability of Data and Materials

All data for this study are publicly available.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Author Contribution

JHB led the conceptualization of the study, the methodological approach, and formal analysis of the data. BF and AM prepared the original draft. All authors reviewed, edited, and gave final approval for the manuscript.

Declarations

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

Not applicable.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

In the United States, wearing a mask is not just politicized. It is racialized. (Rhea Boyd, The Nation, 7-9-20)

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Rossen LM, Branum AM, Ahmad FB, Sutton P, Anderson RN. Excess deaths associated with COVID-19, by age and race and ethnicity — United States, January 26–October 3, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep [Internet] 2020;69(42):1522–1527. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6942e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gold JAW, Rossen LM, Ahmad FB, Sutton P, Li Z, Salvatore PP, et al. Race, ethnicity, and age trends in persons who died from COVID-19 — United States, May–August 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep [Internet] 2020;69(42):1517–1521. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6942e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.CDC. COVID-19 Hospitalization and death by race/ethnicity [Internet]. CDC COVID-19 Cases, Data & Surveillance. 2020 [cited 2020 Nov 18]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/covid-data/investigations-discovery/hospitalization-death-by-race-ethnicity.html

- 4.Turk S. Racial disparities in Louisiana’s COVID-19 death rate reflect systemic problems [Internet]. WWL-TV. 2020 [cited 2020 Nov 18]. Available from: https://www.wwltv.com/article/news/health/coronavirus/racial-disparities-in-louisianas-covid-19-death-rate-reflect-systemic-problems/289-bd36c4b1-1bdf-4d07-baad-6c3d207172f2

- 5.Núñez A, Madison M, Schiavo R, Elk R, Prigerson HG. Responding to healthcare disparities and challenges with access to care during COVID-19. Heal Equity [Internet]. 2020;4(1):117–28 [cited 2020 Nov 18] Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7197255/. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Yancy CW. COVID-19 and African Americans [Internet]. Vol. 323, JAMA - Journal of the American Medical Association. American Medical Association; 2020 [cited 2020 Nov 18]. p. 1891–2. Available from: https://www.washingtonpost.com/nation/ [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Patton M. The effect of mandatory mask policies and politics on economic recovery: a state by state view [Internet]. Forbes. 2020; [cited 2020 Nov 18]. Available from: https://www.forbes.com/sites/mikepatton/2020/07/03/the-effect-of-mandatory-mask-policies-and-politics-on-economic-recovery-a-state-by-state-view/?sh=60ede67123c3.

- 8.Nguyen H. Nearly two in three Americans say wearing face masks in public should be mandatory [Internet]. YouGov. 2020; [cited 2020 Aug 14]. Available from: https://today.yougov.com/topics/health/articles-reports/2020/06/26/americans-wearing-face-masks-should-be-mandatory.

- 9.McKelvey T. Coronavirus: why are Americans so angry about masks? [Internet]. BBC News. 2020; [cited 2020 Aug 14]. Available from: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-53477121.

- 10.Milosh M, Painter M, Van DD, Wright AL. Unmasking partisanship: how polarization influences public responses to collective risk [Internet] Chicago. 2020;IL:2020–2102. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dhanani LY, Franz B. Unexpected public health consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic: a national survey examining anti-Asian attitudes in the USA. Int J Public Health [Internet] 2020;65(6):747–754. doi: 10.1007/s00038-020-01440-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ash E, Galletta S, Hangartner D, Margalit Y, Pinna M. The effect of fox news on health behavior during COVID-19 [Internet]. [cited 2020 Aug 14]. Available from: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3636762

- 13.Stewart E. Anti-mask protesters explain why they refuse to cover their faces during the COVID-19 pandemic [Internet]. Vox. 2020; [cited 2020 Aug 14]. Available from: https://www.vox.com/the-goods/2020/8/7/21357400/anti-mask-protest-rallies-donald-trump-covid-19.

- 14.de La Garza A. For Black Men, Homemade masks may be a risk all their own [Internet]. TIME. 2020; [cited 2020 Aug 13]. Available from: https://time.com/5821250/homemask-masks-racial-stereotypes/.

- 15.Black YD. Americans wearing masks can’t escape danger [Internet]. Wash Post. 2020; [cited 2020 Aug 13]. Available from: https://www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/2020/04/10/coronavirus-masks-black-america/.

- 16.Taylor DB. For Black Men, fear that masks to protect from COVID-19 will invite racial profiling [Internet]. The New York Times. 2020; [cited 2020 Aug 13]. Available from: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/14/us/coronavirus-masks-racism-african-americans.html.

- 17.McFarling UL. “Which death do they choose?”: many Black men fear wearing a mask more than the coronavirus [Internet]. Stat. 2020; Available from: https://www.statnews.com/2020/06/03/which-deamany-black-men-fear-wearing-mask-more-than-coronavirus/.

- 18.Alfonso F III. Why some people of color say they won’t wear homemade masks [Internet]. CNN. 2020; [cited 2020 Aug 13]. Available from: https://www.cnn.com/2020/04/07/us/face-masks-ethnicity-coronavirus-cdc-trnd/index.html.

- 19.Pew Research Center. Republicans, Democrats move even further apart in coronavirus concerns [Internet]. Pew Research. 2020; [cited 2020 Aug 14]. Available from: https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2020/06/25/republicans-democrats-move-even-further-apart-in-coronavirus-concerns/.

- 20.Risk for COVID-19 Infection, hospitalization, and death by race/ethnicity | CDC [Internet]. [cited 2021 May 18]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/covid-data/investigations-discovery/hospitalization-death-by-race-ethnicity.html

- 21.Iceland J, Weinberg DH, Steinmetz E, Coupe P, Del Pinal J, Friedman S, et al. Racial and ethnic residential segregation in the United States: 1980-2000. Census 2000 Special Reports. 2002.

- 22.Bonilla-Silva E. Racism without racists: color-blind racism and the persistence of racial inequality in America [Internet] New York: Rowman and Littlefield; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Milner A, Franz B, Henry BJ. We need to talk about racism - in all of its forms - in understand COVID-19 disparities. Heal Equity [Internet] 2020;4(1):397–402. doi: 10.1089/heq.2020.0069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.II JHB The perpetuation of segregation across levels of education: a behavioral assessment of the contact-hypothesis. Sociol Educ. 1980;53(3):178. doi: 10.2307/2112412. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bonilla-Silva E. Racism without racists : color-blind racism and the persistence of racial inequality in America. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boyd R. What it means when you wear a mask—and when you refuse to [Internet]. The Nation. 2020; [cited 2020 Aug 13]. Available from: https://www.thenation.com/article/society/mask-racism-refusal-coronavirus/.

- 27.Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. COVID-19 Projections [Internet]. Seattle: University of Washington; 2020 [cited 2020 Nov 18]. Available from: https://covid19.healthdata.org/united-states-of-america?view=total-deaths-&-tab=trend

- 28.Harring A. More than half of U.S. states have statewide mask mandates [Internet]. CNBC. 2020; [cited 2021 Apr 2]. Available from: https://www.cnbc.com/2020/07/20/more-than-half-of-us-states-have-statewide-mask-mandates.html.

- 29.US Census Bureau. Appendix B: measures of residential segregation [Internet]. Housing Patterns. 2016; [cited 2020 Nov 18]. Available from: https://www.census.gov/topics/housing/housing-patterns/guidance/appendix-b.html.

- 30.Kaiser Family Foundation. COVID-19 deaths by race/ethnicity [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2020 Nov 18]. Available from: https://www.kff.org/other/state-indicator/covid-19-deaths-by-race-ethnicity/?currentTimeframe=0&sortModel=%7B%22colId%22:%22Location%22,%22sort%22:%22asc%22%7D

- 31.Kershaw KN, Robinson WR, Gordon-Larsen P, Hicken MT, Goff DC, Carnethon MR, et al. Association of changes in neighborhood-level racial residential segregation with changes in blood pressure among black adults: The CARDIA study. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(7):996–1002. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.1226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Faber JW. We built this: consequences of new deal era intervention in America’s racial geography. Am Sociol Rev. 2020;85(5):739–775. doi: 10.1177/0003122420948464. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Alexander D, Currie J. Is it who you are or where you live? Residential segregation and racial gaps in childhood asthma. J Health Econ. 2017;55:186–200. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2017.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Niemesh GT, Shester KL. Racial residential segregation and black low birth weight, 1970–2010. Reg Sci Urban Econ. 2020;83:103542. doi: 10.1016/j.regsciurbeco.2020.103542. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bonilla-Silva E. The structure of racism in color-blind, “post-racial” America. Am Behav Sci. 2015;59(11):1358–1376. doi: 10.1177/0002764215586826. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Forman TA, Lewis AE. Beyond prejudice? Young Whites’ racial attitudes in post-civil rights America, 1976 to 2000. Am Behav Sci. 2015;59(11):1394–1428. doi: 10.1177/0002764215588811. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hutchins HJ, Wolff B, Leeb R, Ko JY, Odom E, Willey J, et al. COVID-19 mitigation behaviors by age group — United States, April–June 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep [Internet] 2020;69(43):1584–1590. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6943e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. COVID-19 projections [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2021 Jun 21]. Available from: https://covid19.healthdata.org/united-states-of-america?view=mask-use-&tab=trend

- 39.Milner A, Franz B. Anti-black attitudes are a threat to health equity in the United States. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2019;7(1):169–176. doi: 10.1007/s40615-019-00646-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Franz BN, Milner A, Brown RK. Opposition to the affordable care act has little to do with health care. Race Soc Probl [Internet] 2020;1:3. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data for this study are publicly available.