Abstract

Background:

Informed consent is a cornerstone of the ethics of modern medical care. In an ideal world, informed consent is a process of education – a conversation between a surgeon and a patient or family that allows the patient or family to make the best possible decision regarding care.

Objective:

The study was conducted with objectives of assessing information given to the patient before taking consent for surgery and determining the compliance to various contents of the consent forms.

Material and Methods:

This was a prospective study over a period of 12 weeks in wards of various surgical departments of a 1000+ bedded tertiary care hospital. Patient interviews were conducted to assess their level of information and the consent forms were reviewed to assess the compliance.

Observations:

The overall level of information r4egarding various aspects among the participants was 75.14%. The level of information varied statistically with age, literacy level, annual income and the type of surgery. All the patients (100%) stated that they were informed about the current clinical condition/ problem, while only 34% were informed about risk and 26% about the alternative options. All the forms (100%) had a statement regarding the explanation of procedure to the patient/ guardian and none of the forms (0%) contained names of all practitioners performing the procedure.

Conclusion:

There is need to create awareness among doctors and also to educate patients regarding the importance of informed consent.

Keywords: Consent from, informed consent, legal responsibility, patient right

Introduction

Informed consent is an integral part of the modern healthcare delivery system. In an ideal world, informed consent is a process of education—a conversation between a physician/surgeon and a patient or his/her family that allows them to take the best possible decision regarding care. The consent form was intended to be a documentary evidence of the conversation between the patient and the healthcare provider, which has now become a medicolegal necessity.[1]

Informed consent is an ethically and legally binding requirement for medical care. It has important roots in Anglo-American political theory and has been reiterated in the law through multiple judicial decisions over time.[2,3] Informed consent also forms the ethos of the modern practices of shared decision-making and patient-centric care.[4]

Studies from developing countries show that patients view written consent as ritualistic and bureaucratic and some even feel pressured to give consent.[5,6]

Childers has described three essential components of surgical consent which are “disclosure which determines the interests and values of the patient and doctor, patient understanding of the disease and the procedure, and patient decision making which is based on the patient's understanding of the information regarding the risk and benefit.”[7,8]

Considering the above, researchers in India are beginning to recognize the limitations of standard informed consent forms. For patients with low educational background, this document appears to be suspicious and they are hesitant to sign it. In other instances, the informed consent process has become a mere formality with subject/patients simply acquiescing to whatever is required of them.

Objectives

-

(i)

To assess the information given to the patient before taking consent for surgery.

-

(ii)

To determine the compliance to various contents of the consent forms.

Material and Methods

This was a prospective study with a view to assess the information given to patients before signing the consent form and to assess the efficiency in filling up the consent form. The study was carried out for 12 weeks in the wards of various surgical departments such as General Surgery, Neurosurgery, Plastic Surgery, Urology, and Obstetrics and Gynecology of a tertiary care hospital in a metropolitan city. The sample size was calculated to be 200 using a statistical software by using a sample size of previously related studies and considering the degree of freedom as 5 and the study subjects were selected using simple random sampling. The study was carried out as a routine operational activity after taking due approvals. Since there was no human sampling or intervention, ethics committee approval was not sought.

Exclusion criteria

All patients who have been operated on in any other hospital.

Patients that were admitted for nonsurgical management.

Critically ill postoperative patients.

After studying the available literature regarding informed consent in relevant journals, a validated checklist was adopted from WHO's website. The investigator made multiple visits to various wards and all the patients who had undergone surgery were identified. Only those patients who were physically fit enough to participate in the interview and gave written consent were included in the study. Patients’ demographic data such as age, sex, education, monthly income, date of admission and surgery, and diagnosis were recorded from the case sheet. Then a structured interview was conducted which was based on 14 points in the checklist and marked as yes or no according to the responses given by patients. A team of four members conducted the interview in English/Hindi/local language and the results were transcribed in English for analysis. A framework analytical approach was used for data analysis which involved the categorical analysis of data on the following five parameters pertaining to patients who had undergone surgery. All interviews were carried out in privacy and both patients and their relatives were assured of confidentiality. These responses were calculated for each patient and inference was drawn from graphs plotted for the five parameters, i.e., age, sex, education, type of patient, and type of surgery (elective or emergency), by using appropriate computer software.

Another eight-point checklist was employed for the assessment of efficiency in filling up the informed consent forms. The responses were undertaken as yes and no, directly from the filled consent forms. These responses were calculated and inference was withdrawn.

Observations

A total of 200 patients were interviewed to assess the information provided to them before undergoing surgery. To put the data in quantifiable terms, a validated checklist was used and the responses were marked as “Yes” or “No” depending on whether the information was provided to the patient or not.

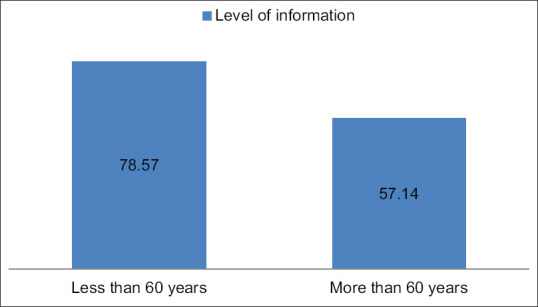

In this study, it was found that patients aged more than 60 years (n = 32) showed an average of eight “Yes” responses (57.14%) and patients below 60 years of age (n = 168) had an average of 11 (78.57%). In the present study, it was found that patients aged less than 60 years were better informed. [Figure 1]. The P value was found to be significant at 0.001.

Figure 1.

Comparison of the level of information among different age groups

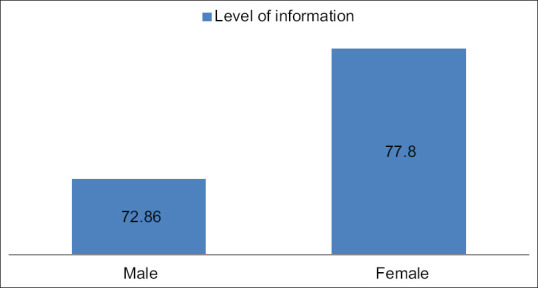

The average “Yes” responses of male and female patients were 10.2 (72.86%) and 10.9 (77.80%), respectively. The mean scores did not differ significantly according to sex as the P value was 0.910 [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

Comparison of the level of information among both genders

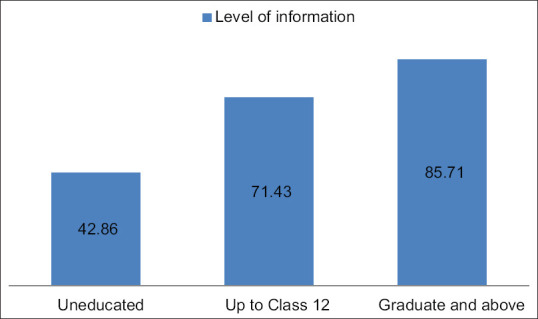

The education level of patients was classified as uneducated and educated. The educated category was further divided into patients with a graduate degree and patients with education up to 12th standard. In the present study, we found a direct correlation between the educational status and information provided to the patient. The better the educational status the better the information provided to him/her. The difference among various groups was statistically significant as the P value was < 0.001 [Figure 3].

Figure 3.

Variation of the level of information with education level

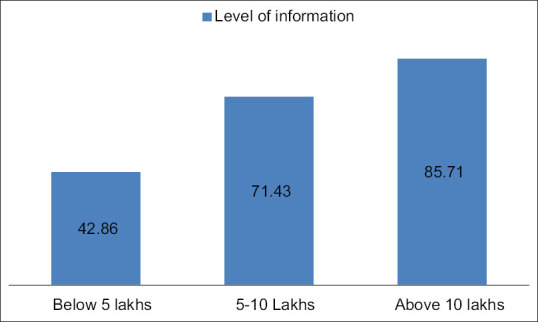

Patients of the hospital were categorized based on their economic status into three categories viz. patients with annual income below 5 lac, between 5 and 10 lac, and more than 10 lac. In our study, it was found that patients of the higher economic status category were better informed compared to other categories and the difference was statistically significant (p value < 0.001) [Figure 4].

Figure 4.

Variation of level of information with the annual income of the patient

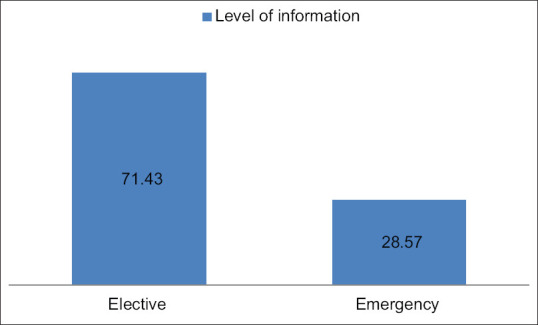

Based on clinical condition, the patients were categorized into emergency cases and elective surgery patients. The study revealed that the elective surgery patients were better informed as compared to the emergency ones and the difference was statistically significant with a P value of < 0.001 [Figure 5].

Figure 5.

Comparison level of information among the two types of surgical procedures

The percentage of patients who were informed about the various parameters of the informed consent was calculated. All the patients (100%) stated that they were informed about the current clinical condition/problem. However, 26% of the patients were least informed about the alternative options available to them [Table 1].

Table 1.

Percentage of patients informed regarding various parameters of informed consent

| Parameter | Remark |

|---|---|

| Discussed the patient’s current clinical situation or problem | 100% |

| Discussed the indication for the proposed procedure | 98% |

| Discussed the purpose of a proposed treatment or procedure | 96% |

| Explained the actual procedure of the patient | 84% |

| Explained the risks involved | 34% |

| Explained the benefits of the procedure | 90% |

| Informed about the alternative options available to the patient | 26% |

| The risks and benefits of alternatives | 24% |

| Asked whether patient had any queries | 94% |

| Told the patient when he/she can resume work | 60% |

| Informed briefly about the postoperative care the patient has to take | 94% |

| Addressed all queries of the patient | 84% |

| Summarized the discussion | 70% |

| Rechecked that the patient was willingly giving consent | 98% |

The consent forms were examined to assess the compliance to various components of the informed consent. It was observed that all the forms (100%) had a statement regarding the explanation of the procedure to the patient/guardian. None of the forms (0%) contained the names of all the practitioners performing the procedure. The compliance to various contents is depicted in Table 2.

Table 2.

Compliance to various contents of the informed consent form

| Parameter | Compliance |

|---|---|

| Name and signature of the patient, or if appropriate, legal guardian | 98% |

| Name of the hospital | 98% |

| Name of all practitioners performing the procedure and individual significant task if more than one practitioner | 0% |

| Date and time consent is obtained | 42% |

| Statement that procedure was explained to patient or guardian | 100% |

| Name of the procedure | 86% |

| Signature of professional person witnessing the consent | 54% |

| Name and signature of person who explained the procedure to the patient or guardian | 90% |

Perception of patients on informed consent

Many of the patients interviewed in the study were not aware of the importance of informed consent. A few patients mentioned that they signed the paper just because a doctor had asked them to sign it without even going through the content. Few of the patients considered signing a consent form as a formality which they had to do before undergoing the surgery.

Why patients did not ask queries before signing the consent

During the interview, the investigators were given many reasons why patients did not ask queries regarding the surgery or their clinical condition. All the reasons given by the patients could be summarized in one word “trust.” Many patients had the belief that the doctor knows the best. This behavior was predominantly seen in patients of lower socioeconomic status and uneducated patients.

Discussion

The present informed consent form was found to have certain deficiencies such as

-

(i)

There was no designated space to mention the name of all the practitioners performing the procedure

-

(ii)

In place of the signature of the doctor, it is mentioned the signature of MO (Medical officer). Therefore, in case a specialist explains about the surgery, the specialist does not sign as an MO.

-

(iii)

All the departments of the hospital do not have a similar format for consent forms. It is recommended to have a standard informed consent form for the entire hospital.

-

(iv)

An ideal consent form must have the following components[9,10]:

- Name & signature of the patient or if appropriate the legal guardian

- Name of the hospital where the procedure has to be performed

- Name of all practitioners performing the procedure

- Statement that the procedure was explained to the patient or guardian along with the benefit(s), risk(s), and alternative choice(s) of treatment

- Specific name of the procedure

- Name and signature of the professional person witnessing the consent

In literature, informed consent has been described as a process where a healthcare provider disseminates information regarding the potential benefits, risks, and alternatives of a treatment to the patient.[11] Hence, it makes informed consent an integral part of healthcare delivery at every level for the involvement of patients in decision-making. This can also be interpreted in light of Article 21 of the Indian Constitution which describes the principle of autonomy envisaging the right to life and personal liberty.[12]

Searight and Barbarash in their article on informed consent in family practice emphasized that informed consent is much beyond its clinical and legal dimensions in family medicine. The family physicians have a long-term relationship with their patients which makes them responsible for engaging their patients in clinical decision making as they better understand the needs of their patients.[13]

Hanson and Pitt in their paper titled “Informed consent for surgery: risk discussion and documentation” discussed the challenges in obtaining informed consent such as preoperative anxiety among patients and language barrier which warrants a family member acting as a translator leading to information loss.[14] However, at times, the patients may be eager and need a detailed discussion to which the surgeon must comply. These might be the possible factors for the lack of information regarding certain aspects that may be disturbing for the patients to hear such as the risks involved (only 34% were informed) and the available alternatives (only 26% informed).

In a multicentric study by Koyfman et al. to compare information provided through conversations and that documented, it was observed that certain critical elements were often omitted from the conversation.[15] Similarly, our study revealed although 100% of the consent forms stated that patients had been informed regarding the procedure, only 34% of the patients stated that they were informed about the risks and 26% stated that they were informed about alternative choices.

A study conducted in the UK by Sivanadarajah et al. on the readability of the informed consent form concluded that due to varying literacy levels and the information written in the consent form, a majority of the patients may struggle to give informed consent.[16] Our study also concluded that patients’ understanding of the procedure was related to their level of education, with the more educated ones being able to assimilate more knowledge.

Wood et al. studied the perspective of the doctors to assess the barriers to obtaining consent. The major barriers identified were lack of time, inexperience of the clinicians, and patient factors such as reluctance.[17] They observed that most often junior doctors were responsible for obtaining consent from patients for the procedure that they themselves were not familiar with. Even in our Institute, consent is obtained by junior doctors who at times have limited knowledge about the risks and alternative treatments. This explains why the patients had little knowledge about certain aspects of the procedure.[18]

Literature states that patients may avoid the consent process and place ‘faith’ in the clinician.[17,19] In our study, during the interview, the investigators were told multiple reasons why patients did not ask queries. The essence of all reasons was “trust”; a majority of the patients were of the opinion that the doctor knows the best for the patients.

A review article by Chong-Wen Wang et al. regarding a social worker's role in advanced care planning of patients, it was stated that social workers play a role in discussing the clinical condition, treatment, and prognosis of the disease with patients and attendants.[20,21]

Elective patients were significantly more likely to report satisfaction with consent (80%) than emergency patients (63%),

In a study conducted by Akkad et al. to compare the consent for elective and emergency procedures, it was stated that emergency patients were less likely to be satisfied with the information provided regarding the study.[22] They further discovered that patients did not read through the contents of the consent form as they were provided verbal information and trusted the doctors. Both these findings were similar to our study.

Conclusion and Recommendations

There is a need to create awareness among doctors regarding the importance of informed consent. Informed consent must not be viewed merely as a legal formality but as a tool to educate the patients and enhance their involvement in decision-making. The scope of informed consent is much beyond surgical procedures and it adds a whole new dimension to family medicine as it presents an opportunity to patients to raise concerns about their course of treatment. The possibility of involving a medical social worker in the consent process may be explored to ease out the burden on the doctors. Finally, a revision of the informed consent form may be considered to include all the requisite information in a simple patient-friendly language.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Crepeau AE, McKinney BI, Fox-Ryvicker M, Castelli J, Penna J, Wang ED. Prospective evaluation of patient comprehension of informed consent. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93:e114 (1–7). doi: 10.2106/JBJS.J.01325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berg JW, Appelbaum- PJ. Informed Consent: Legal Theory & Clinical Practice. 02nd ed. New York, NY: Oxford university press Inc; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Faden RR, Beauchamp TL, King NM. A History & Theory of Informed Consent. New York, NY: Oxford University Press Inc; 1986. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Laine C, Davidoff F. Patient centered medicine: A professional evolution. JAMA. 1996;275:152–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pérez-Moreno JA, Pérez-Cárceles MD, Osuna E, Luna A. Información preoperatoria y consentimiento informado en pacientes intervenidos quirúrgicamente [Preoperative information and informed consent in surgically treated patients] Rev Esp Anestesiol Reanim. 1998;45:130–5. Spanish. PMID: 9646652. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Akkad A, Jackson C, Dixon-Woods M, Taub N, Habiba M. Informed consent for elective and emergency surgery in obstetrics and gynaecology: A questionnaire study. BJOJ. 2004;111:1133–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2004.00240.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Childers R, Lipsett PA, Pawlick TM. Informed consent and the surgeon. J Am Coll Surg. 2009;208:627e634. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2008.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stain SC. Informed surgical consent. J Am Coll Surg. 2016;222:717–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2015.12.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Federal Code Title 42 Tag A-0238 x482.24(c)(2)(v) [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cocanour cS. Informed consent-It's more than a signature on a piece of paper. Am J Surg. 2017;214:993–7. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2017.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shah P, Thornton I, Turrin D, Hipskind JE. StatPearls [Internet] Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2021. Informed consent. Updated 2020 Aug 22. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK430827/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nandimath OV. Consent and medical treatment: The legal paradigm in India. Indian J Urol. 2009;25:343–7. doi: 10.4103/0970-1591.56202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Searight HR, Barbarash RA. Informed consent: Clinical and legal issues in family practice. Fam Med. 1994;26:244–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hanson M, Pitt D. Informed consent for surgery: Risk discussion and documentation. Can J Surg. 2017;60:69–70. doi: 10.1503/cjs.004816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Koyfman SA, Reddy CA, Hizlan S, Leek AC, Kodish AE Phase I Informed consent (POIC) Research Team. Informed Consent conversations and documents: A quantitative comparison. Cancer. 2016;122:464–9. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sivanadarajah N, El-Daly I, Mamarelis G, Sohail MZ, Bates P. Informed consent and the readability of the written consent form. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2017;99:645–9. doi: 10.1308/rcsann.2017.0188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wood F, Martin SM, carson-Stevens A, Elwyn G, Precious E, Kinnersley P. Doctors’ perspectives of informed consent for non-emergency surgical procedures: A qualitative interview study. Health Expect. 2016;19:751–61. doi: 10.1111/hex.12258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carson-Stevens A, Davies M, Jones R, Chik A, Robbe I, Fiander A. Framing patient consent for student involvement in pelvic examination: A dual model of autonomy. J Med Ethics. 2013;39:676–80. doi: 10.1136/medethics-2012-100809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Medical Protection Society. Consent to Medical Treatment in the UK: An MPS Guide. London: Medical Protection Society; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang CW, chan CL, Chow AY. Social workers’ involvement in advance care planning: A systematic narrative review [published correction appears in BMC Palliat care 2017;16:51] BMc Palliat Care. 2017;17:5. doi: 10.1186/s12904-017-0218-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Werner P, Carmel S, Ziedenberg H. Nurses'and social workers'attitudes and beliefs about and involvement in life-sustaining treatment decisions. Health Social Work. 2004;29:27–35. doi: 10.1093/hsw/29.1.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Akkad A, Jackson c, Kenyon S, Dixon-Woods M, Taub N, Habiba M. Informed consent for elective and emergency surgery: Questionnaire study. BJOG. 2004;111:1133–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2004.00240.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]