Abstract

Changes in both the coding sequence of transcriptional regulators and in the cis-regulatory sequences recognized by these regulators have been implicated in the evolution of transcriptional circuits. However, little is known about how they evolved in concert. We describe an evolutionary pathway in fungi where a new transcriptional circuit (a-specific gene repression by the homeodomain protein Matα2) evolved by coding changes in this ancient regulator, followed millions of years later by cis-regulatory sequence changes in the genes of its future regulon. By analyzing a group of species that has acquired the coding changes but not the cis-regulatory sites, we show that the coding changes became necessary for the regulator’s deeply conserved function, thereby poising the regulator to jump-start formation of the new circuit.

Changes in transcriptional circuits over evolutionary time are an important source of organismal novelty. Such circuits are typically composed of one or more transcriptional regulators (sequence-specific DNA binding proteins) and their direct target genes, which contain cis-regulatory sequences recognized by the regulators. Although changes in cis-regulatory sequences are often stressed as sources of novelty that avoid extensive pleiotropy, it is clear that coding changes in the transcriptional regulatory proteins are also of key importance (1–6). Some well-documented changes in transcriptional circuitry require concerted changes in both elements (7, 8). Although such concerted changes are likely to be widespread, we know little about how they occur.

In this work, we study a case in the fungal lineage where gains in cis-regulatory sequences and coding changes in the transcriptional regulator were both required for a new circuit to have evolved. Specifically, we addressed which came first: the changes in the regulatory protein or the changes in the cis-regulatory sequences of its 5 to 10 target genes. The system we analyzed consists of an ancient regulator, the homeodomain protein Matα2, and the changes—both in the protein itself and in the regulatory regions of the genes it controls—that occurred across the Saccharomycotina clade of fungi, which spans roughly 300 million years. [In terms of protein diversity, this represents roughly the range between humans and sea sponges (9)]. Throughout this time, Matα2 has maintained its ancient function: It binds cooperatively to DNA with a second homeodomain protein, Mata1, to repress a group of genes called the haploid-specific genes (Fig. 1). More recently, Matα2 formed an additional circuit, which is present in only a subset of the Saccharomycotina: It binds DNA cooperatively with the MADS box protein Mcm1 to repress the a-specific genes (Fig. 1). Before this time, the a-specific genes were regulated by a different mechanism—positive control by the HMG-domain protein Mata2 (10, 11).

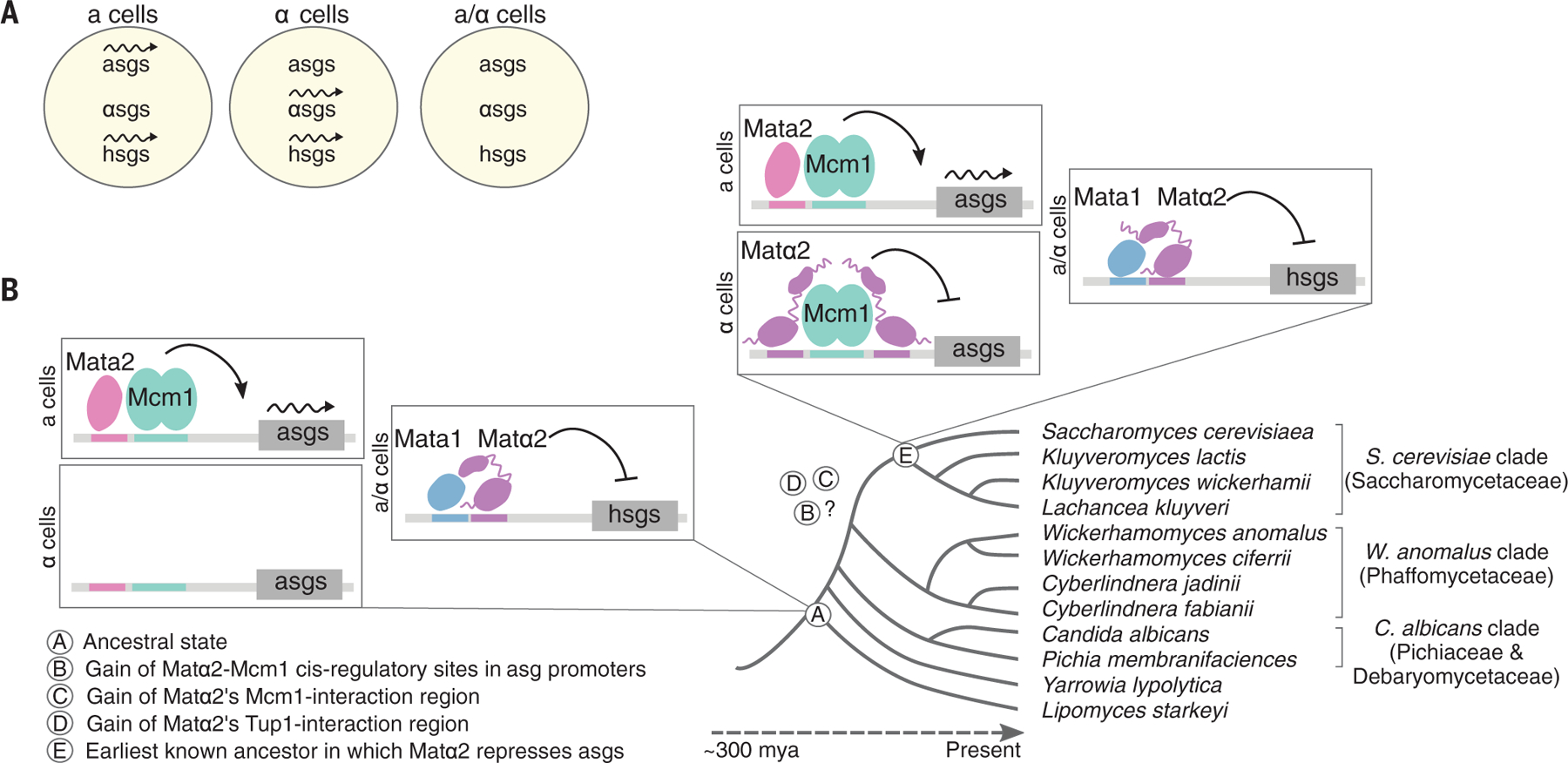

Fig. 1. Cell type–specific gene expression in the Saccharomycotina yeast.

(A) Across the Saccharomycotina clade, a and α cells each express a set of genes specific to that cell type (a- and α-specific genes, or asgs and αsgs, respectively), as well as a shared set of haploid-specific genes (hsgs). a and α cells can mate to form a/α cells, which do not express the a-, α-, or haploid-specific genes (22). Wavy arrows represent active transcription. (B) The mechanism underlying the expression of a-specific genes is different among species. In the last common ancestor of the Saccharomycotina yeast (see circled A in the figure), transcription of the a-specific genes was activated by Mata2, a protein produced only in a cells, which binds directly to the regulatory region of each a-specific gene (10, 23). Much later in evolutionary time (see circled E in the figure), repression of the a-specific genes by direct binding by Matα2 evolved. Still later, the Mata2-positive form of control was lost in some species (including S. cerevisiae), leaving only the Matα2-negative form. mya, million years ago.

The switch between the two mechanisms of controlling the a-specific genes occurred some-time before the divergence of Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Kluyveromyces lactis (formally known as the Saccharomycetaceae, here called the S. cerevisiae clade) but after the divergence of this clade and that containing Candida albicans and Pichia membrifaciens (formally known as the Pichiaceae and Debaryomecetaceae, here called the C. albicans clade) (Fig. 1B). Three events must have occurred for the newer (repression) scheme to have evolved: (i) Matα2 acquired the ability to contact the Tup1-Ssn6 co-repressor, bringing it to DNA to carry out the repression function; (ii) Matα2 acquired the ability to bind to DNA cooperatively (through a direct protein-protein contact) with Mcm1; and (iii) the a-specific genes (numbering between 5 and 10, depending on the species) each acquired a new cis-regulatory site for the Matα2-Mcm1 combination (Fig. 1B).

To determine the order of these events, we studied Matα2 and the regulation of the a-specific genes in a clade that branched from the ancestor before the occurrences of all three of these events. We reasoned that this group of species might have acquired some, but not all, of the changes needed to form the new circuit, and it therefore might provide clues to the evolutionary history. This approach was made possible by the genome sequencing of a monophyletic group of species that branches before the last common ancestor of the S. cerevisiae clade (formally known as the Phaffomycetaceae) (Fig. 1B) (12, 13). We chose the species Wickerhamomyces anomalus, and we were able to optimize relatively simple procedures to alter it genetically (14).

We examined the W. anomalus Matα2 protein sequence to determine whether it is more similar to the ancestral (represented by C. albicans) or the derived (represented by S. cerevisiae) form of Matα2. Alignment of the Matα2 coding sequences across many species indicated that, of the five functional regions described for the S. cerevisiae protein (Fig. 2A and fig. S1), the W. anomalus protein shares all of them. In particular, it has a similar Tup1-interacting region (region 1, Fig. 2A) and Mcm1-interacting region (region 3, Fig. 2A); these regions are missing in outgroup proteins and are needed to repress the a-specific genes in S. cerevisiae (11, 15). By swapping these W. anomalus regions into the S. cerevisiae protein, we confirmed that they are functional in repressing the a-specific genes (Fig. 2B). In the course of these experiments, we found that the homeodomain of the W. anomalus protein contained mutations that prevented its binding to the a-specific gene cis-regulatory sequence in S. cerevisiae, a derived change within this clade alone (Fig. 2B and fig. S1). Similar results were obtained with the Matα2 protein from two additional species that branch with W. anomalus, indicating that these two conclusions—that W. anomalus clade Matα2 bears functional protein-protein interactions but cannot bind the S. cerevisiae a-specific genes—are characteristic of the W. anomalus clade rather than of a single species (fig. S1D).

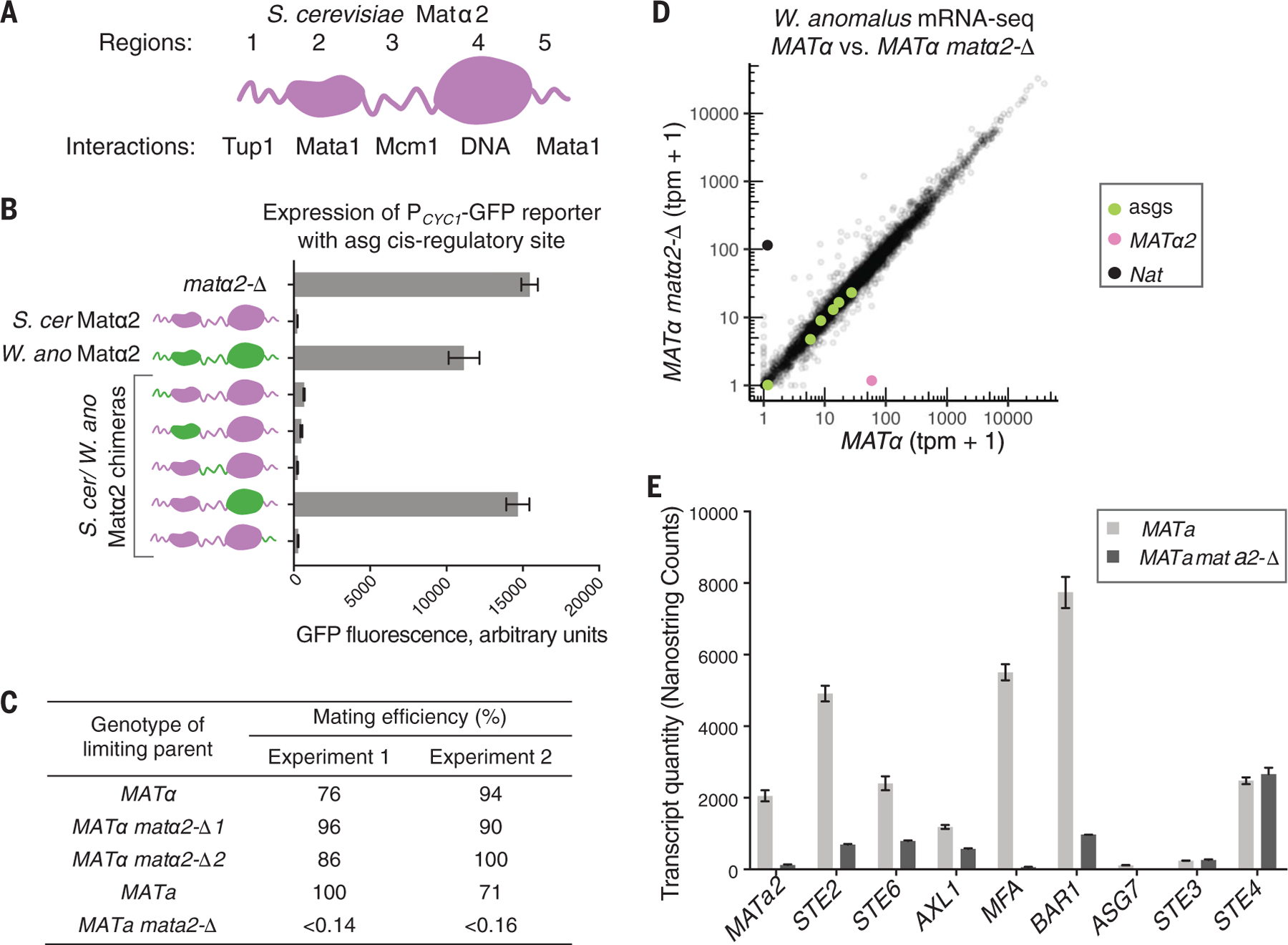

Fig. 2. W. anomalus Matα2 has functional Tup1- and Mcm1-interacting regions but does not repress the a-specific genes.

(A) The five modules of the S. cerevisiae Matα2 protein. Structural domains are shown as globular, and unstructured regions are shown as wavy lines. (B) Expression of an a-specific gene reporter in the presence of S. cerevisiae (S. cer) Matα2 (purple), W. anomalus (W. ano) Matα2 (green), and hybrid proteins (purple and green). Means and SDs of three independent genetic isolates, grown and tested in parallel, are shown. GFP, green fluorescent protein. (C) In W. anomalus, Mata2, but not Matα2, is required for a cells to mate (see supplementary text for details). (D) mRNA sequencing (mRNA-seq) (tpm, transcripts per million) of wild-type W. anomalus α cells (MATα) compared with a cells with MATα2 deleted (MATα2 matα2-Δ). a-specific genes STE2, AXL1, ASG7, BAR1, STE6, and MATa2 are shown in green. Expression of MATα2 and the marker used to delete it (Nat) are shown in pink and opaque black, respectively. Data from independent replicates are given in fig. S3. (E) a-specific gene expression levels in a wild-type W. anomalus a cells (MATa) compared with a cells with MATa2 deleted (MATa2 mata2-Δ), measured by the NanoString nCounter system (24). For comparison, expression levels of the α-specific gene STE3 and the haploid-specific gene STE4 are also given. Means and SDs of two cultures per genotype, grown and tested in parallel, are shown.

The observation that the W. anomalus Matα2 protein acquired the necessary coding changes to interact with Tup1 and Mcm1 but could not bind to the S. cerevisiae a-specific gene control region raised the question of whether it has any role in regulating the a-specific genes in W. anomalus. A series of otherwise-isogenic strains was constructed with Matα2 (and Matα2) deleted, and the results show that, in this species, Matα2 does not regulate the a-specific genes; they are instead regulated by Mata2 (Fig. 2, C to E, and fig. S3). Thus, despite the changes in Matα2, W. anomalus retains the ancestral form of a-specific gene regulation and activation by Mata2. This conclusion is supported by a bioinformatic analysis showing that the a-specific genes possess Mata2-Mcm1, but not Matα2-Mcm1 cis-regulatory sequences (fig. S4B). These results argue against the possibility that direct, a-specific gene repression by Matα2 existed in an ancestor of W. anomalus but was subsequently lost, as this would have required the independent loss of Matα2 binding sites from all of the a-specific genes across numerous species.

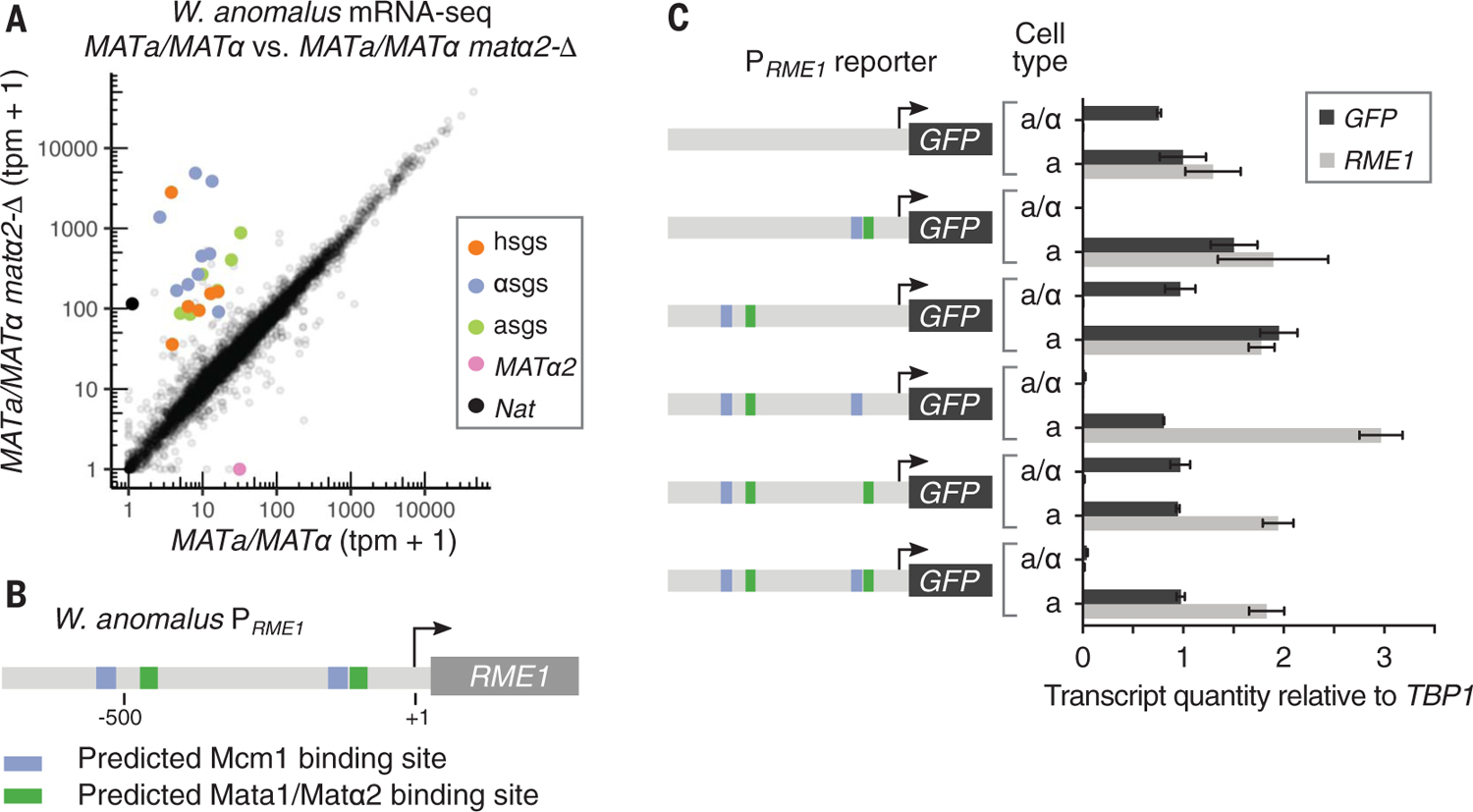

Our experiments up to this point demonstrate that Matα2 had acquired the coding changes needed to repress the a-specific genes millions of years before its cis-regulatory sequences appeared in the a-specific genes. We next addressed how these changes in the Matα2 protein could have been maintained in the absence of their usefulness in repressing the a-specific genes. One hypothesis focuses on Matα2’s ancient function—repressing the haploid-specific genes with Mata1—and holds that the Matα2 coding changes became required for this function only in the W. anomalus clade. To test this idea, we analyzed the requirements for haploid-specific gene repression in W. anomalus. We deleted MATα2 and MATa1 in a/α cells and found that they are both necessary for haploid-specific gene repression, a conclusion confirmed by chromatin immunoprecipitation (Fig. 3A and figs. S5 and S6C). However, unlike in species outside the W. anomalus clade, the Tup1-interaction region and the Mcm1-interaction region of Matα2 are necessary for repression of the haploid-specific genes within the clade (Fig. 2A and fig. S6B). Finally, an Mcm1 cis-regulatory site is also required for the repression of the W. anomalus haploid-specific gene RME1 (Fig. 3C and fig. S6). Taken together, these experiments show that Matα2, Mata1, and Mcm1 are all required for haploid-specific gene repression in W. anomalus, and that the portions of Matα2 that interact with Mcm1 and Tup1 are also required. This three-part recognition of the haploid-specific genes in the W. anomalus clade was not anticipated from studies of other species. Even in the S. cerevisiae clade, where Mcm1 and Matα2 are known to interact, this interaction is not required for haploid-specific gene repression (11). These results explain the observation that the key changes in Matα2 needed for the new a-specific gene circuit were already in place in the last common ancestor of S. cerevisiae and W. anomalus, long before the circuit came into play (Fig. 4). An alternative scenario—in which the Matα2 protein gained the Mcm1-interaction region twice, once in the S. cerevisiae clade and once in the W. anomalus clade—is unlikely because the same seven amino acids would have had to be gained in exactly the same position in the protein (fig. S1).

Fig. 3. Mata1, Matα2, and an Mcm1 cis-regulatory sequence are all required for haploid-specific gene repression in W. anomalus.

(A) mRNA-seq of a wild-type W. anomalus a/α cell (MATa/MATα) compared with an a/α cell with MATα2 deleted (MATa/MATα matα2-Δ). The a-specific genes are shown in green, the haploid-specific genes in orange, and the α-specific genes in blue. Data from one culture of each genotype are plotted here, and data from replicates, grown and prepared in parallel, and similar results obtained by deleting Mata1 are shown in fig. S5. (B) Diagram of the sequence upstream of the RME1 coding sequence indicating presumptive Mata1-Matα2 (green) and Mcm1 (blue) binding sites. Arrow indicates the transcription start site. (C) Expression levels of endogenous RME1 transcript (which serves as a control) and various PRME1-GFP reporter constructs in W. anomalus a and a/α cells measured by reverse transcription quantitative polymerase chain reaction. Quantities are means and SDs of two cultures grown and measured in parallel, normalized to expression of the housekeeping gene TBP1. Independent replicates are given in fig. S6.

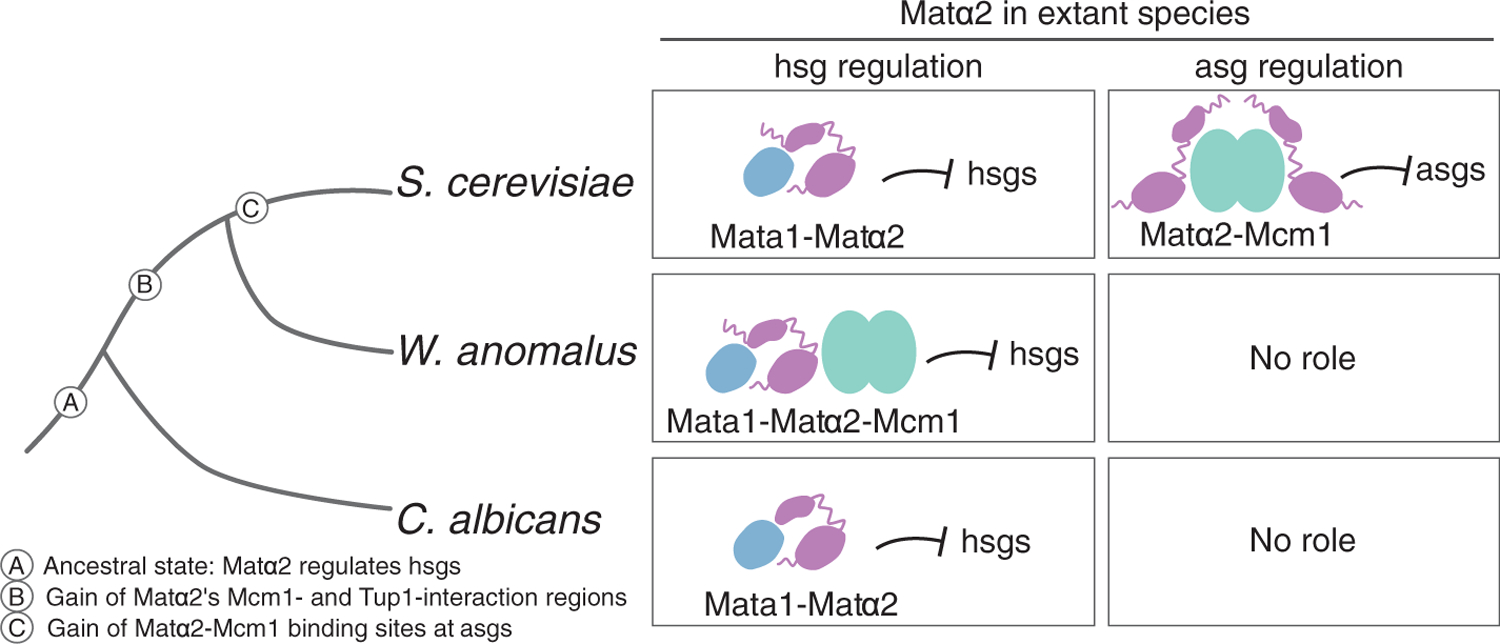

Fig. 4. Order of evolutionary events leading to repression of the a-specific genes by Matα2.

The three-protein solution for repressing the haploid-specific genes remains in the W. anomalus clade, but in the S. cerevisiae lineage it was partitioned into a-specific gene regulation (which uses only two proteins, Mcm1 and Matα2) and repression of the haploid-specific genes (which requires Matα2 and Mata1). The three-protein intermediate explains how the necessary changes in the regulatory protein Matα2 could have been maintained for millions of years before being co-opted for the new circuit.

This study helps to illuminate several long-standing issues. First, how is pleiotropy avoided when transcriptional regulators acquire new functions? The modular structure of Matα2 is evident from the protein domain swap experiments (Fig. 2B and fig. S6B), showing that the derived regions of the protein (Tup1- and Mcm1-interaction regions) can be transplanted to a variety of outgroup Matα2 proteins and that they endow the ancestral proteins with the new functions without compromising the existing functions (11). However, there is a second, more subtle way that extensive pleiotropy was avoided in the case studied in this work. In the shift between the different ways of controlling the haploid-specific genes, pleiotropy was avoided automatically; even before the new a-specific gene circuit was formed, the Matα2-Mcm1 combination (which forms the basis of the new circuit) had been “vetted” for millions of years as being compatible with the ancestral function of Matα2.

Second, is the evolutionary pathway we describe in this paper compatible with the concept of constructive neutral evolution, or the idea that new functions can evolve through evolutionary transitions of approximately equal fitness (16–18)? Before the results presented here were obtained, it was difficult to understand how the derived circuit represented by S. cerevisiae (repression of the a-specific genes by Matα2 in α cells) could have evolved because it required changes in both the Matα2 coding region and in the cis-regulatory sequences controlling the 5 to 10 a-specific genes. We propose that the prior changes to Matα2 represent an example of constructive neutral evolution, in the sense that the neutral sampling of different ways to repress the haploid-specific genes over evolutionary time led to changes in Matα2 that, millions of years later through exaptation, formed the basis of the new circuit. Although we cannot rule out the possibility that the differences in the way that the haploid-specific genes were repressed were somehow adaptive, it seems more likely that they occurred neutrally—an explanation consistent with a wide variety of theoretical work (16–19). In any case, there is no obvious adaptive explanation, and neutral evolution is an appropriate default hypothesis.

Third, is there an inherent logic to the mechanisms underlying a given transcription circuit? In this paper, we show that some clades regulate the haploid-specific genes with a combination of three proteins, whereas others use only two of the proteins, even though the third is present. Nonetheless, the overall pattern of haploid-specific gene expression is the same. If there is any overriding design logic to the different mechanisms of regulating these genes, it is difficult to discern (20). More broadly, the work presented here illustrates that a given transcription circuit is best understood as one of several possible interchangeable, mechanistic solutions rather than as a finished, optimized design (21).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank L. Noiman, M. Lohse, C. Dalal, K. Fowler, and L. Booth for comments on the manuscript and C. Baker, I. Nocedal, N. Ziv, and B. Heineke for advice. We thank C. Schorsch of Evonik Industries for providing us with the plasmid used to genetically modify W. anomalus.

Funding:

The work was supported by NIH grant R01 GM037049 (to A.D.J.), an ARCS Scholarship (to C.S.B.), and an NSF Graduate Fellowship (to T.R.S.).

Footnotes

Competing interests: The authors declare no competing interests.

Data and materials availability:

Plasmid pCS.ΔLig4 can be obtained from Evonik Industries under a material transfer agreement. mRNA-seq data have been deposited at the National Center for Biotechnology Information Gene Expression Omnibus under accession number GSE133191.

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Lynch VJ, Wagner GP, Evolution 62, 2131–2154 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cheatle Jarvela AM, Hinman VF, EvoDevo 6, 3 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stern DL, Orgogozo V, Evolution 62, 2155–2177 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wray GA, Nat. Rev. Genet 8, 206–216 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wittkopp PJ, Kalay G, Nat. Rev. Genet 13, 59–69 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li H, Johnson AD, Curr. Biol 20, R746–R753 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sayou C et al. , Science 343, 645–648 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baker CR, Tuch BB, Johnson AD, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 108, 7493–7498 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shen X-X et al. , Cell 175, 1533–1545.e20 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tsong AE, Miller MG, Raisner RM, Johnson AD, Cell 115, 389–399 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baker CR, Booth LN, Sorrells TR, Johnson AD, Cell 151, 80–95 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shen X-X et al. , G3 6, 3927–3939 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Riley R et al. , Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 113, 9882–9887 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kurtzman C, Fell JW, Eds., The Yeasts - A Taxonomic Study (Elsevier, 1998). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Komachi K, Johnson AD, Mol. Cell. Biol 17, 6023–6028 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stoltzfus A, J. Mol. Evol 49, 169–181 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lukeš J, Archibald JM, Keeling PJ, Doolittle WF, Gray MW, IUBMB Life 63, 528–537 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gray MW, Lukes J, Archibald JM, Keeling PJ, Doolittle WF, Science 330, 920–921 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wagner A, FEBS Lett 579, 1772–1778 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dalal CK, Johnson AD, Genes Dev 31, 1397–1405 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sorrells TR, Johnson AD, Cell 161, 714–723 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Herskowitz I, Nature 342, 749–757 (1989). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tsong AE, Tuch BB, Li H, Johnson AD, Nature 443, 415–420 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Geiss GK et al. , Nat. Biotechnol 26, 317–325 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Plasmid pCS.ΔLig4 can be obtained from Evonik Industries under a material transfer agreement. mRNA-seq data have been deposited at the National Center for Biotechnology Information Gene Expression Omnibus under accession number GSE133191.