Abstract

Background and aims

A sizable body of research has elucidated the significant role of psychological reactions to trauma on pain coping and outcomes. In order to best inform intervention development and clinical care for patients with both trauma and pain at the tertiary care level, greater clarity is needed regarding the magnitude of these effects and the specific pathways through which they may or may not function at the time of first presentation to such a treatment setting. To achieve this, the current study examined the cross-sectional relationships between traumatic etiology of pain, psychological distress (anger, depressive symptoms, and PTSD symptoms), and pain outcomes (pain catastrophizing, physical function, disability status).

Methods

Using a structural path modeling approach, analyses were conducted using a large sample of individuals with chronic pain (N = 637) seeking new medical evaluation at a tertiary pain management center, using the Collaborative Health Outcomes Information Registry (CHOIR). We hypothesized that the relationships between traumatic etiology of pain and poorer pain outcomes would be mediated by higher levels of psychological distress.

Results

Our analyses revealed modest relationships between self-reported traumatic etiology of pain and pain catastrophizing, physical function, and disability status. In comparison, there were stronger relationships between indices of psychological distress and pain catastrophizing, but a weaker pattern of associations between psychological distress and physical function and disability measures.

Conclusions

To the relatively small extent that self-reported traumatic etiology of pain correlates with pain-related outcomes, these relationships appear to be due primarily to the presence of psychiatric symptoms and manifest most notably in the context of psychological responses to pain (i.e., catastrophizing about pain).

Implications

Findings from this study highlight the need for early intervention for patients with traumatic onset of pain and for clinicians at tertiary pain centers to include more detailed assessments of psychological distress and trauma as a component of comprehensive chronic pain treatment.

Keywords: pain catastrophizing, chronic pain, trauma, Collaborative Health Outcomes Information Registry (CHOIR), mood

Introduction

Prior research has suggested that the experience of trauma uniquely impacts the pain experience (1), proposing patients with pain stemming from a traumatic event, such as a car collision or military conflict, may present differently and have unique treatment needs compared to other pain patients (2). Pain originating from a traumatic injury is associated with increased affective disturbance, life interference, and pain severity compared to pain without traumatic onset (3–5). There is a growing interest around the connection between chronic pain and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), which are highly comorbid (6, 7), as well as how trauma-related factors may influence chronic pain-related outcomes. Prior research has identified PTSD as not only a significant risk factor for chronic pain development (8, 9), but has also highlighted it as a potential moderator or mediator between traumatic events and poor pain outcomes (10–12). Pain patients with comorbid PTSD have been found to have poorer physical and mental health on various indices, including pain intensity, anxiety, depression, physical function, disability, and opioid use (7, 13, 14). A growing literature over the last several years utilizing both cross-sectional and longitudinal approaches suggests that the mere existence of traumatic etiology of pain is not necessarily a meaningful predictor of pain outcomes itself but it is psychological distress related to the trauma which appears to influence responses to pain (15–18). The mutual maintenance model (19) proposes that the interaction of components of the two conditions, such as attentional bias and negative affect, may explain the high prevalence of comorbidity of chronic pain and PTSD. The extant literature has highlighted individual links between trauma and various indices of emotional distress, including depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress symptoms, and pain catastrophizing, in support of the mutual maintenance model (15, 17, 20–22).

Pain catastrophizing, a pattern of cognitive and emotional responses to pain, including rumination, magnification, and feelings of helplessness (23), is an outcome of particular interest as it has been shown to be a primary predictor of the development of chronic pain and is associated with greater pain intensity, higher mood disturbance, greater disability, and poorer response to medical intervention (24, 25). Pain catastrophizing and PTSD symptoms have evidenced significant associations in samples of whiplash injury participants (26) as well as in war veterans sustaining injury (27), highlighting pain catastrophizing as a potential target for assessment and treatment in patients impacted by traumatic onset of pain.

Supplementing prior work that has profiled chronic pain patients with a history of trauma as having a high prevalence of emotional distress and high rates of disability (28, 29), it is useful to highlight the relative contributions of these factors to pain-related outcomes in individuals with chronic pain using a comprehensive modeling approach. In an effort to help clarify such relationships, with particular attention to how these variables may be functioning at the tertiary care level, this study used a structural path modeling approach to examine PTSD symptoms, anger, and depression as potential intervening psychological variables in the relationship between traumatic etiology of pain and pain-related outcomes in a sample of patients from a multidisciplinary tertiary care pain clinic. We hypothesized that the relationships between traumatic etiology of pain and poorer pain outcomes would be partially explained by higher concurrent levels of emotional distress.

Materials and Methods

We conducted a retrospective review of clinical data from the Collaborative Health Outcomes Information Registry (CHOIR; http://choir.stanford.edu). Prior to their first appointment at the Stanford Pain Management Center, all patients electronically completed the series of questionnaires included within CHOIR, either at home through a secure email link or via a tablet in the clinic waiting room. Responses to a subset of the measures collected were used in this analysis. All procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board at the Stanford University School of Medicine. All data extraction and analyses were completed under an IRB-sapproved retrospective chart review protocol.

One of the current barriers to effective treatment of chronic pain is the lack of consistent data with which to describe pain conditions and with which to pinpoint the subpopulations that will benefit most from specific treatments. CHOIR was developed by Stanford University as part of the Stanford-NIH Open Source Health Registry initiative in an effort to improve the collection and reporting of pain data. CHOIR collects an array of patient self-report measures at every visit to the Stanford Pain Management Center in Redwood City, California, as well as at follow up clinic visits. A primary goal of CHOIR is to enable large-scale capturing of biopsychosocial data while avoiding many common issues in similar non-CHOIR investigations, such as non-standardized vocabularies and non-generalizability of samples so that findings that can be more confidently used as a basis for intervention development and dissemination. CHOIR data from the Stanford Pain Management Center has been utilized in other published studies (30–35). The current study is the first to use CHOIR data to examine trauma.

Measures

Trauma variable:

Traumatic etiology of chronic pain was assessed using a single item, “Is your pain from a traumatic event?” with yes or no response options. No examples of traumatic events were provided, relying on patients to interpret whether the origin of their pain is traumatic or not.

Disability Status:

Disability status was assessed using a single item, “Are you receiving any kind of disability?” with yes and no response options.

PTSD Symptoms:

Current PTSD symptoms were assessed using the Primary Care PTSD Screen (36) which has demonstrated high diagnostic accuracy. The measure includes a stem of, “In your life, have you ever had any experience that was so frightening, horrible, or upsetting that, in the past month, you:” and has 4 items with yes/no response options. Items included, 1) Have had nightmares about it or thought about it when you did not want to? 2) Have tried hard not to think about it or went out of your way to avoid situations that reminded you of it? 3) Were constantly on guard, watchful, or easily startled? 4) Felt numb or detached from others, activities, or your surroundings? The Primary Care PTSD has been used in previous studies of individuals with chronic pain (37).

Pain catastrophizing:

Pain catastrophizing was assessed using the Pain Catastrophizing Scale (PCS) (23). The PCS has 3 subscales, rumination, magnification, and helplessness. Responses to 13 questions are quantified on a 5-point scale and are summed for a total score of 0 to 52 to determine trait pain catastrophizing tendencies in daily life. Example items include, “I worry all the time about whether the pain will end” and “It’s terrible and I think it’s never going to get any better.” The PCS has been validated for use in clinical pain samples (38, 39).

PROMIS Instruments:

Pain intensity, anger, physical function, and depression were assessed using Patient-Reported Outcome Measurement Information System (PROMIS) item banks. PROMIS is a set of reliable, precise assessments of physical and mental health and social well–being developed by the NIH to help standardize assessments. By using Computer Adaptive Testing (CAT), which determines the next question that is asked of the patient based on his or her response to the previous question, PROMIS has improved measurement accuracy and reliability and decreased time-burden for the patient in comparison to traditional standard scale assessments (40–42). PROMIS instruments are based on an item response theory-based assessment that utilizes item level responses rather than composite scale responses. PROMIS measures are normed against the U.S. population and have a mean of 50 points and a standard deviation of 10 points. CAT-based administrations frequently administer a substantially smaller number of items but yield superior efficiency in domain assessment and greater precision in terms of lower standard error compared to traditional, non-adaptive testing forms. Higher scores on PROMIS measures reflect greater severity of symptoms. PROMIS measures of pain intensity, physical function, anger, and depression showed clinical validity in a range of clinical conditions, including chronic pain at the tertiary care level (43).

The PROMIS Pain Intensity item, “In the past 7 days, how intense was your average pain?” using an 11-point numerical rating scale ranging from 0 (no pain) to 10 (pain as bad as you can imagine), was used to assess pain intensity. Numerical rating scales have demonstrated validity as an assessment of pain in chronic pain studies (44).

PROMIS Anger was used to assess anger in the past 7 days and has been previously used to assess anger in a chronic pain samples (35). The PROMIS Anger measure is derived from the legacy instrument Bus-Perry Aggression Questionnaire (45). The average number of items for the CAT PROMIS Anger is 6.24 ± 1.21. Example items include, “I felt like yelling at someone” and “I was grouchy” with response options of never, rarely, sometimes, often, and always.

PROMIS Physical Function was used to assess physical function and has previously been used to assess physical function in chronic pain samples (34). The PROMIS Physical Function measure is derived from the legacy instrument the Health Assessment Questionnaire-Disability Index (46). The average number of items for the CAT PROMIS Physical Function is 4.11 ± 0.48. Example items include, “Does your health now limit you in doing two hours of physical labor?” and “Are you able to do chores such as vacuuming or yard work?” with response options of not at all, very little, somewhat, quite a lot, and cannot do.

PROMIS Depression was used to assess depressive symptoms in the past 7 days and has previously been used to assess depression in chronic pain samples (33). The PROMIS Depression measure is derived from the legacy instrument the Patient Health Questionnaire (47). The average number of items for the CAT PROMIS Depression is 4.97 ± 1.07. Example items include, “I felt sad” and “I felt discouraged about the future” with response options of never, rarely, sometimes, often, and always.

Participants

A one-time data extraction was conducted for January 2014-May 2014 for patients who presented for initial medical evaluation at the Stanford Pain Management Center, a large, tertiary care pain clinic (N = 637). The sample had a mean age of 48.9 years (SD = 16.3; range = 17–91 years) and was 61.3% female (N = 390). The most common marital status was currently married (50.2%) followed by never married (22.6%). The predominant ethnicity was white (64.6%), followed by Asian (7.7%), African American (2.8%), Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander (1.3%), and American Indian or Alaska Native (.8%). An ethnicity of “Other” was reported by 16.4%, 4.1% of the sample did not endorse an ethnicity and 2.4% reported an ethnicity of “Unknown.” Median education level in the patient sample was some college. Characterization of patients’ pain complaints was assessed via broad categories related to the suspected etiology of pain; categories were not mutually exclusive. In the sample, 52.2% of patients reported nerve-related pain, 31.1% reported pain due to an initial injury, 28.5% reported muscle-related pain, 27.0% reported pain from an injured disc, 15.7% reported pain from a bone problem, 3.8% reported pain related to an infection, and 3.6% reported pain from cancer. Notably, 24.7% reported an unknown etiology of their pain. About a third of the sample (33.5%) reported that they were currently working, and 30.7% reported being disabled. Regarding the trauma variable, 22.0% of the sample (N = 140) reported a traumatic onset of their pain.

Analytic Plan

All analyses were conducted using path modeling approaches in Mplus version 5.12. First, the direct effect of the traumatic onset of pain variable was estimated as a predictor of pain catastrophizing, physical function, and disability status. The traumatic onset of pain variable was specified as a binary (“yes/no”) variable. Similarly, disability status was specified as a binary outcome; consequently, any models examining disability status as an outcome were computed using a logit function. After direct effects were estimated, fully-estimated models estimated the mediating effects of 3 measures of psychological distress (symptoms of PTSD, depression, and anger), above and beyond the effects of traumatic onset of pain, on the relationships between traumatic etiology of pain and each outcome variable. As these models were saturated, all indices of model fit represent perfect fit and are thus not reported in the current paper. While data collection was conducted at a single time point, this study is assessing distinct temporal events: past trauma and current symptoms. Some have suggested employing the term “intervening variable” in lieu of “mediator” when temporal precedence of the examined effects cannot be confirmed from longitudinal data collection (48); however, for the purposes of brevity, we utilize the term “mediation analysis” in the current paper. Mediated effects were estimated using an ab coefficient product approach (48), representing the product of the effect of the predictor on the mediator (the “a path”) and the effect of the mediator on the outcome (the “b path”). Average pain intensity over the previous 7 days was included as a covariate in all paths in the fully-specified model. As path modeling approaches do not lend themselves to clear effect size metrics, we report an r2 proportional reduction of variance metric to represent the relative effects of each set of predictors on each outcome(49). All path coefficients are presented in their standardized form to allow comparison regarding the relative size of each relationship.

Results

Descriptive statistics for study variables can be found in Table 1 and bivariate correlations between all study continuous variables can be found in Table 2. Of the sample, 28 (4.4%) declined to answer the traumatic onset of pain question and were thus omitted from analysis. All other variables had no missing data.

Table 1:

Descriptive statistics for study variables

| Traumatic onset of pain | N | Mean | SD | t | Sig (2-tailed) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pain | No | 468 | 22.86 | 12.44 | −3.113 | <.01 |

| Catastrophizing | Yes | 140 | 26.56 | 11.99 | ||

| Physical | No | 468 | 34.64 | 7.80 | −2.15 | .032 |

| Function | Yes | 140 | 33.11 | 7.22 | ||

| Depression | No | 468 | 57.43 | 9.90 | −3.143 | <.01 |

| Yes | 140 | 60.36 | 8.95 | |||

| PTSD | No | 468 | .42 | .95 | −6.401 | <.01 |

| Symptoms | Yes | 140 | 1.30 | 1.54 | ||

| Anger | No | 468 | 52.99 | 10.77 | −4.060 | <.01 |

| Yes | 140 | 57.16 | 10.39 | |||

| Pain Intensity | No | 468 | 5.87 | 2.14 | −1.462 | .144 |

| Yes | 140 | 6.17 | 1.00 |

Table 2:

Bivariate correlations between all study variables

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Depression | 1 | .337** | .712** | −.351** | .618** | .254** |

| 2. | PTSD Symptoms | 1 | .402** | −.133** | .328** | .066 | |

| 3. | Anger | 1 | −.246** | .533** | .200** | ||

| 4. | Physical Function | 1 | −.285** | −.337** | |||

| 5. | PCS | 1 | .365** | ||||

| 6. | Pain Intensity | 1 |

p < .01

Note: PCS = Pain Catastrophizing Scale

Note: PTSD symptoms computed as a count variable.

Direct effects on pain-related outcomes.

When the direct effect of traumatic etiology of pain was estimated (with no other predictors in the model), traumatic onset of pain demonstrated a significant direct effect on pain catastrophizing, physical function, and likelihood of being on disability. In all cases, the direct effects of the trauma variable accounted for a very small proportion of the variance in outcome variables (r2 between .007 and .020 in all cases; see Table 3 for proportions of variance accounted for in each outcome). Inclusion of pain intensity in the model as a covariate reduced the direct effect of traumatic onset of pain on disability status to statistical non-significance (p > .10). The direction and significance of the direct effects of traumatic onset of pain were otherwise unaffected when pain intensity was included in the model.

Table 3:

Proportion of variance accounted for by direct and indirect effects in each outcome variable

| Outcome Variable | Direct Effect (Traumatic Onset Only) | Traumatic Onset and 3 Mediators |

|---|---|---|

| Pain Catastrophizing | .016 | .376 |

| Physical Function | .007 | .126 |

| Disability Status | .020 | .051 |

Note: Direct effect represented as proportion of variance accounted for in endogenous variable (r2)

Notably, the presence of traumatic onset of pain was related to significantly greater levels of anger and depressive symptoms, as well as a higher average number of PTSD symptoms endorsed, but these direct effects again accounted for small proportions of the variance in each outcome (r2 between .016 and .100 in all cases). PTSD symptoms, depressive symptoms, and anger scores significantly predicted pain catastrophizing scores in the fully-specified model, above and beyond the effects of pain intensity.

Mediation analysis.

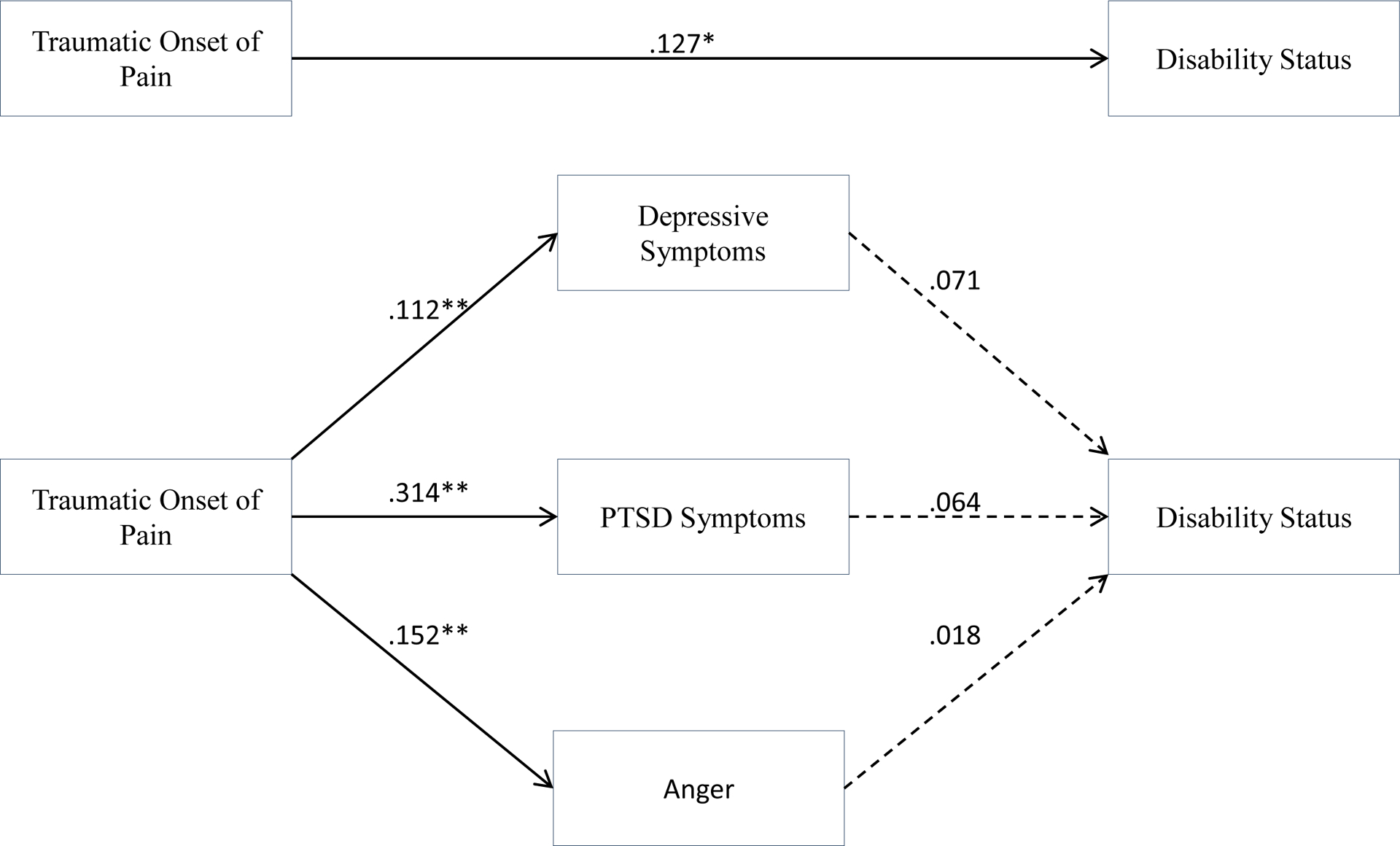

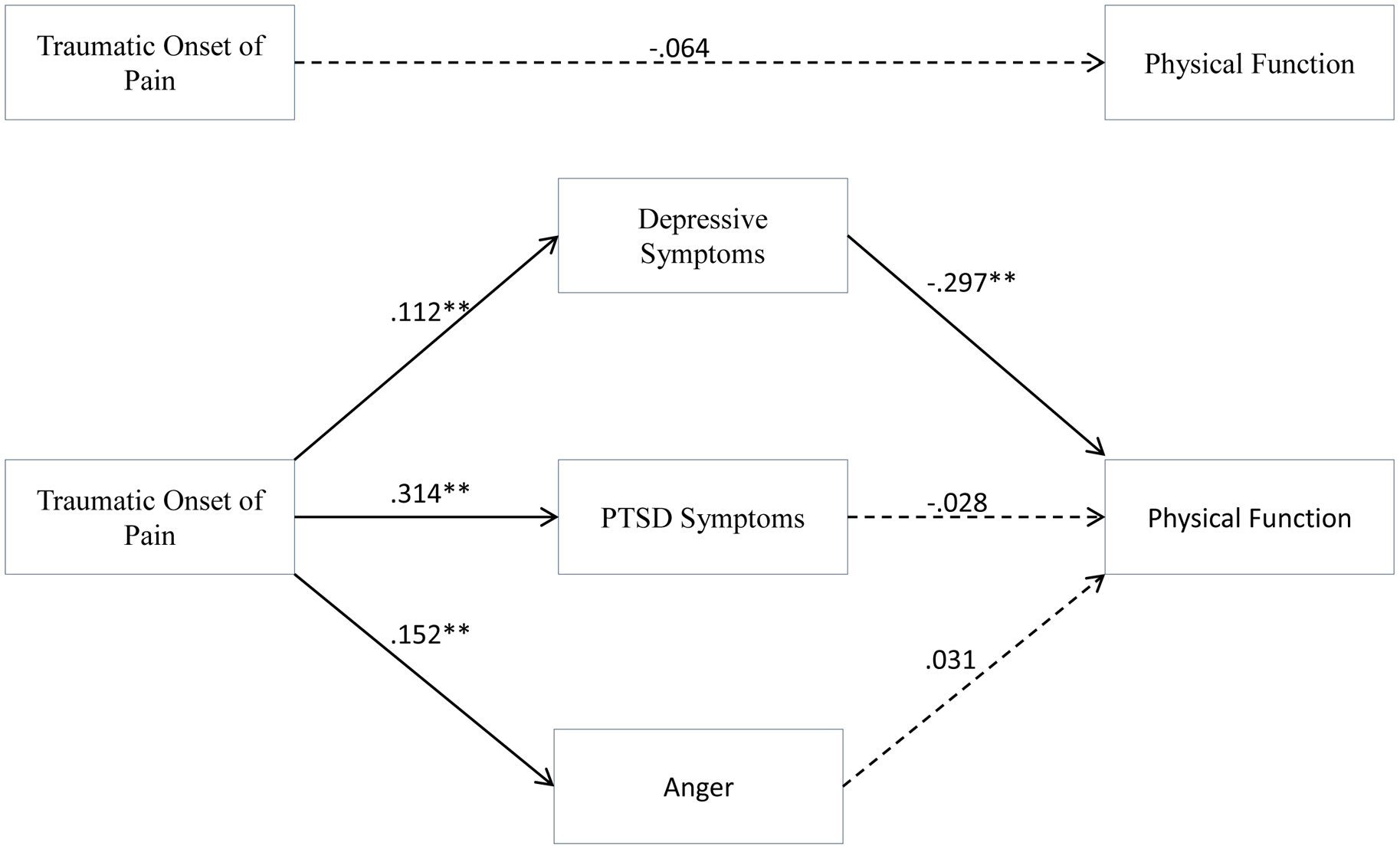

Depressive symptoms (standardized ab = .046, p = .006), PTSD symptoms (standardized ab = .033, p = .004), and anger scores (standardized ab = .022, p = .012) significantly mediated the relationship between traumatic onset of pain and pain catastrophizing scores. Only depressive symptoms were found to mediate the relationship between traumatic onset of pain and physical function (standardized ab = −.033, p = .010). As none of the 3 examined mediators were significant predictors of disability status, no mediated effects were estimated in this path model. See Figures 1–3.

Figure 1:

Path model with Traumatic Onset of Pain predicting Pain Catastrophizing with Depressive Symptoms, PTSD Symptoms and Anger as mediating variables

Note: ** = p < .01, * = p < .05

Direct Effect R2 = .016

Figure 3:

Path model with Traumatic Onset of Pain predicting Disability Status with Depressive Symptoms, PTSD Symptoms and Anger as mediating variables

Note: ** = p < .01, * = p < .05

Direct Effect R2 = .020

Discussion

In an effort to contribute to an improved understanding of the web of psychological factors present in chronic pain and the context in which they emerge and operate at the tertiary care level, this study explored the effects of traumatic etiology of pain on important pain outcomes including pain catastrophizing, physical function and disability status using a dataset that provided standardized phenotypic data for hundreds of clinic patients. In support of our hypotheses and in line with previous work (15–18), our analyses showed that to the extent that traumatic onset of pain contributes to pain outcomes in tertiary care patients, these effects can be attributed primarily to concurrent psychiatric symptoms and appear to manifest almost exclusively in psychological responses to pain.

Although self-reported traumatic etiology of pain predicted pain-related outcomes, the direct effects on pain-related outcomes were small. In our investigation, all psychiatric distress variables appeared to mediate effects of trauma on pain catastrophizing, while only depressive symptoms mediated the effects of trauma on physical function. In these cases, the emotional distress variables appeared to have a stronger relationship with pain variables, compared to traumatic etiology. This latter finding parallels prior CHOIR publications demonstrating a significant cross-sectional relationship between depressive symptoms and physical function (34). It is notable that neither the trauma variable nor psychiatric distress variables were related to disability status. This is in contrast with prior work that has found higher levels of psychological distress to be correlated with increased disability in pain samples (50, 51) and in particular post-traumatic stress symptoms to be related to increased disability (7, 17, 20). The current findings may be due to the highly disabled and chronic nature of pain in our patient sample as well as the relatively low-resolution and static nature of the disability status variable, but nevertheless suggests that neither prior traumatic experiences nor psychiatric distress were significant distinguishing factors between disabled and non-disabled patients. The ambiguous wording of the disability question should be considered as it can take on various meanings to different patients; wording specifying work disability may have led to different results. Although it is certainly possible that traumatic etiology is a relevant factor in the development of chronic pain, our results suggest that any consequences of such difficulties may be too remote to manifest in terms of chronic pain outcomes by the time patients present for treatment in a tertiary pain clinic. Our findings add input to the inconclusive discussion in this area of the literature regarding impact of trauma and psychological distress on physical function and disability, with some studies showing significant associations and others, like ours, failing to find meaningful relationships (14).

Catastrophizing has been identified as an important vulnerability to onset and maintenance of both chronic pain and PTSD (52) and our analyses revealed fairly robust relationships between the psychiatric distress variables and pain catastrophizing. Development of psychiatric symptoms following trauma may lead to increased anxiety sensitivity and an appraisal bias, with ambiguous situations or sensations being interpreted as dangerous (53). Reminders of the trauma (flashbacks, nightmares, etc.), which may be pain-related, could lead to informational biases and increased attention to pain. Individuals high in pain catastrophizing tend to have difficulty controlling or suppressing pain-related thoughts, with heightened rumination about pain, amplification of the potential severity of the pain, and feelings of helplessness around the pain (23). While directionality claims cannot be made here, psychiatric symptoms such as PTSD, depressed mood, and anger appear to coincide with more pronounced catastrophic thinking patterns, and all of these factors do appear to manifest more prominently in patients with a self-reported history of traumatic onset of pain. It is likely that psychiatric distress and catastrophizing function in a mutual maintenance model, feeding back on each other and increasing the likelihood for continuation of symptomology.

Our findings add to a growing body of studies that underscore the importance of psychological symptomology of chronic pain, and suggest that it may be the emotional significance encoded by the individual who has experienced trauma and subsequent pain, rather than the history of a traumatic event itself, that appears to shape pain coping. While the literature paints a convincing picture that psychological distress following a traumatic event is related to pain outcomes, ambiguity still exists concerning the influences of specific psychological constructs on various pain outcomes, particularly those involving physical functioning and pain-related disability. Our study adds texture to the existing body of literature by using structural equation modeling to demonstrate how common sequelae of trauma (PTSD symptoms, depressive symptoms, and anger) differentially relate to pain outcome variables. Of significance, our investigation includes a specific examination of anger, a meaningful yet underrepresented psychological construct in the existing body of similar work. Another strength of this study was the use of validated instruments administered through CHOIR, including the use of CAT PROMIS measures, which have shown to be more reliable than traditional measurements. Because all individuals seeking treatment in the clinic complete CHOIR, selection bias is minimized as are concerns regarding the representativeness of results that usually arise with studies having a low response-rate or high levels of missing data.

Several limitations of this study are notable. First, the single-item, patient-determined traumatic etiology variable reflects a low resolution of data capture for a complex construct. There is ambiguity around traumatic etiology of pain as the same event may be interpreted as traumatic by some and non-traumatic by others. While the self-report measure quantifies PTSD symptoms, we have no data regarding diagnoses for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). For the current investigation, our team was particularly interested in gaining information regarding the status of patients on first presentation to a tertiary pain center specifically, nevertheless, the cross-sectional design of the current study is an acknowledged limitation. Examining the impact of historical events on current symptoms lends strength to the study as it allows us to characterize relationships through a longitudinal lens, however, data were collected at one time point and subsequent investigations may consider examining these relationships utilizing prospective, longitudinal methodology to better understand how examined constructs relate and change over time.

This study included a large sample size with mixed etiology. Prior work has found that for the most part, the role of psychosocial factors in chronic pain development, maintenance and related outcomes is not condition-specific but similar across an array of chronic pain conditions (1). The size and diagnosis diversity of the sample is beneficial in terms of generalizability of the results, however, no inferences can be made about pain diagnosis subpopulations. It should be noted that our sample is drawn from a tertiary pain clinic where on average patients may have more severe pain than individuals in the community or in primary care. Our sample was predominantly White with a median education of at least some college; as such, findings may not generalize to populations with greater diversity in race and education. Future investigation is warranted as to how demographic factors such as gender or race/ethnicity may impact such relationships in pain patients. This study also did not control for medications and the effects certain medications such as anti-depressants, opioids, and benzodiazepines may have been having on the variables examined in this study. Additionally, this analysis used only self-report measures as representations of the constructs examined. Finally, while a strength of the study is inclusion of multiple psychological responses to trauma, including anger, a limitation is that the models did not specifically account for anxiety which has been shown to relate to trauma and pain (7, 16) and participate in the mutual maintenance model (19). Further research should attempt to extend modeling conducted here to include other important psychological and demographic correlates of pain and trauma to provide a more complete picture of the pain experience for a patient with traumatic etiology of pain.

Despite noted limitations, the current results reinforce previous findings that demonstrate the important role of psychological symptomology in the subpopulation of chronic pain patients who have a traumatic etiology to their pain while also highlighting the relatively limited utility of low-resolution assessment of trauma, such as single-item assessments of trauma status, as was done in this care setting. These findings provide a snapshot characterization of patients presenting for treatment at a comprehensive pain management center and suggest that appropriate psychological screening and intervention may play a critical role in reducing the effect of trauma on the pain experience and also highlight the need for more involved evaluation of factors related to the trauma to determine the extent to which it is impacting pain outcomes.

This study also points to the possible importance of early intervention in people with traumatic injury to help protect against psychological symptomology that may contribute to chronic pain development and maintenance. Prior work showed that in a sample of individuals who had sustained severe injuries, those who developed chronic pain had increased levels of PTSD symptoms and mood disturbance and that the differentiation of outcomes appeared to occur mostly within the first 12 months post-injury (54). Other research conducted in a rehabilitation setting, suggested patients with traumatic onset of pain with high levels of psychological distress including PTSD symptoms and pain catastrophizing could most benefit from early intervention within the first 3 months (22). Our findings call attention to the role of catastrophizing in particular and effectively treating catastrophizing has been shown to reduce pain intensity and a pain-related adverse outcomes (55–57). Psychological treatments for chronic pain patients such as acceptance and commitment therapy, cognitive behavioral therapy, and Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction are relevant to the mutual maintenance model as they involve emotion regulation and distress management (58). Cognitive behavioral approaches have been found to successful reduce both post-traumatic stress symptoms and catastrophic thinking (59, 60). Acceptance and commitment therapy for chronic pain was found to be effective for pain patients with and without PTSD, with the exception of lack of improvement in depressive symptoms for those with PTSD (61). Future work may build on the beginnings of integrative intervention approaches for patients with chronic pain and PTSD (62, 63) to examine the potential benefits of an intervention specifically targeting anger, catastrophizing, depression, and PTSD in the context of pain treatment.

Conclusions

It is crucial to understand the connections and interactions between pain outcomes and contributing factors at each stage in the pain experience to better assist healthcare providers in delivering precision medicine. Our results suggest that at the tertiary pain level in a sample with high levels of pain, disability, and emotional distress, the presence of a traumatic onset of pain was, at most, a small role as a predictor of outcomes, suggesting such historical variables may only be important to the extent that they are connected to current psychosocial factors relevant to pain. Improved treatments for chronic pain are needed and mapping the influence of psychological constructs on the pain experience may shed light on optimal next steps in intervention development and clinical care planning.

Figure 2:

Path model with Traumatic Onset of Pain predicting Physical Function with Depressive Symptoms, PTSD Symptoms and Anger as mediating variables

Note: ** = p < .01, * = p < .05

Direct Effect R2 = .007

Research funding:

Authors acknowledge funding support from National Institutes of Health (NIH) National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH) R01AT008561 (BDD and SCM), P01AT006651 (SCM) and P01AT006651S1 (SCM and BDD); NIH National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) K24DA029262 (SCM); NIH Pain Consortium HHSN271201200728P (SCM); and from the Chris Redlich Pain Research Endowment (SCM).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

Informed consent: Informed consent has been obtained from all individuals included in this study.

Ethical approval: The research related to human use complies with all the relevant national regulations, institutional policies and was performed in accordance with the tenets of the Helsinki Declaration, and has been approved by the authors’ institutional review board or equivalent committee.

Contributor Information

Chloe J. Taub, University of Miami, Department of Psychology, 5665 Ponce De Leon Blvd, Coral Gables, FL, 33124.

John A. Sturgeon, University of Washington School of Medicine Department of Anesthesiology and Pain Medicine.

References

- 1.Edwards RR, Dworkin RH, Sullivan MD, Turk DC, Wasan AD. The role of psychosocial processes in the development and maintenance of chronic pain. The Journal of Pain. 2016;17(9):T70–T92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meints S, Edwards R. Evaluating psychosocial contributions to chronic pain outcomes. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry. 2018;87:168–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Geisser ME, Roth RS, Bachman JE, Eckert TA. The relationship between symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder and pain, affective disturbance and disability among patients with accident and non-accident related pain. Pain. 1996;66(2):207–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Turk DC, Okifuji A. What factors affect physicians’ decisions to prescribe opioids for chronic noncancer pain patients? The Clinical journal of pain. 1997;13(4):330–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Turk DC, Okifuji A. Perception of traumatic onset, compensation status, and physical findings: impact on pain severity, emotional distress, and disability in chronic pain patients. Journal of behavioral medicine. 1996;19(5):435–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brennstuhl MJ, Tarquinio C, Montel S. Chronic pain and PTSD: evolving views on their comorbidity. Perspectives in psychiatric care. 2015;51(4):295–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Åkerblom S, Perrin S, Fischer MR, McCracken LM. The impact of PTSD on functioning in patients seeking treatment for chronic pain and validation of the posttraumatic diagnostic scale. Int J Behav Med. 2017;24(2):249–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kongsted A, Bendix T, Qerama E, Kasch H, Bach FW, Korsholm L, et al. Acute stress response and recovery after whiplash injuries. A one-year prospective study. European journal of pain. 2008;12(4):455–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jenewein J, Wittmann L, Moergeli H, Creutzig J, Schnyder U. Mutual influence of posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms and chronic pain among injured accident survivors: a longitudinal study. Journal of traumatic stress. 2009;22(6):540–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Powers A, Fani N, Pallos A, Stevens J, Ressler KJ, Bradley B. Childhood abuse and the experience of pain in adulthood: the mediating effects of PTSD and emotion dysregulation on pain levels and pain-related functional impairment. Psychosomatics. 2014;55(5):491–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lang AJ, Laffaye C, Satz LE, McQuaid JR, Malcarne VL, Dresselhaus TR, et al. Relationships among childhood maltreatment, PTSD, and health in female veterans in primary care. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2006;30(11):1281–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Raphael KG, Widom CS. Post-traumatic stress disorder moderates the relation between documented childhood victimization and pain 30 years later. PAIN®. 2011;152(1):163–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aaron LA, Bradley LA, Alarcón GS, Triana-Alexander M, Alexander RW, Martin MY, et al. Perceived physical and emotional trauma as precipitating events in fibromyalgia. Associations with health care seeking and disability status but not pain severity. Arthritis & Rheumatology. 1997;40(3):453–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Andersen TE, Andersen L-AC, Andersen PG. Chronic pain patients with possible co-morbid post-traumatic stress disorder admitted to multidisciplinary pain rehabilitation—a 1-year cohort study. European Journal of Psychotraumatology. 2014;5(1):23235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morasco BJ, Lovejoy TI, Lu M, Turk DC, Lewis L, Dobscha SK. The relationship between PTSD and chronic pain: mediating role of coping strategies and depression. Pain. 2013;154(4):609–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ravn SL, Vaegter HB, Cardel T, Andersen TE. The role of posttraumatic stress symptoms on chronic pain outcomes in chronic pain patients referred to rehabilitation. J Pain Res. 2018;11:527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ruiz-Párraga GT, López-Martínez AE. The contribution of posttraumatic stress symptoms to chronic pain adjustment. Health Psychol. 2014;33(9):958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Siqveland J, Ruud T, Hauff E. Post-traumatic stress disorder moderates the relationship between trauma exposure and chronic pain. European journal of psychotraumatology. 2017;8(1):1375337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sharp TJ, Harvey AG. Chronic pain and posttraumatic stress disorder: mutual maintenance? Clin Psychol Rev. 2001;21(6):857–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ravn SL, Hartvigsen J, Hansen M, Sterling M, Andersen TE. Do post-traumatic pain and post-traumatic stress symptomatology mutually maintain each other? A systematic review of cross-lagged studies. Pain. 2018;159(11):2159–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Asmundson GJ, Coons MJ, Taylor S, Katz J. PTSD and the experience of pain: research and clinical implications of shared vulnerability and mutual maintenance models. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 2002;47(10):930–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Andersen TE, Karstoft KI, Brink O, Elklit A. Pain-catastrophizing and fear-avoidance beliefs as mediators between post-traumatic stress symptoms and pain following whiplash injury–A prospective cohort study. European Journal of Pain. 2016;20(8):1241–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sullivan MJ, Bishop SR, Pivik J. The pain catastrophizing scale: development and validation. Psychol Assess. 1995;7(4):524. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Quartana PJ, Campbell CM, Edwards RR. Pain catastrophizing: a critical review. Expert review of neurotherapeutics. 2009;9(5):745–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leung L Pain catastrophizing: an updated review. Indian journal of psychological medicine. 2012;34(3):204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sullivan MJ, Thibault P, Simmonds MJ, Milioto M, Cantin A-P, Velly AM. Pain, perceived injustice and the persistence of post-traumatic stress symptoms during the course of rehabilitation for whiplash injuries. Pain. 2009;145(3):325–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ciccone DS, Kline A. A longitudinal study of pain and pain catastrophizing in a cohort of National Guard troops at risk for PTSD. PAIN®. 2012;153(10):2055–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Castillo RC, MacKenzie EJ, Wegener ST, Bosse MJ, Group LS. Prevalence of chronic pain seven years following limb threatening lower extremity trauma. Pain. 2006;124(3):321–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Roth RS, Geisser ME, Bates R. The relation of post-traumatic stress symptoms to depression and pain in patients with accident-related chronic pain. The Journal of Pain. 2008;9(7):588–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hah JM, Sturgeon JA, Zocca J, Sharifzadeh Y, Mackey SC. Factors associated with prescription opioid misuse in a cross-sectional cohort of patients with chronic non-cancer pain. Journal of pain research. 2017;10:979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sharifzadeh Y, Kao M-C, Sturgeon JA, Rico TJ, Mackey S, Darnall BD. Pain Catastrophizing Moderates Relationships between Pain Intensity and Opioid PrescriptionNonlinear Sex Differences Revealed Using a Learning Health System. Anesthesiology: The Journal of the American Society of Anesthesiologists. 2017;127(1):136–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Karayannis NV, Sturgeon JA, Chih-Kao M, Cooley C, Mackey SC. Pain interference and physical function demonstrate poor longitudinal association in people living with pain: a PROMIS investigation. Pain. 2017;158(6):1063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sturgeon JA, Dixon EA, Darnall BD, Mackey SC. Contributions of physical function and satisfaction with social roles to emotional distress in chronic pain: A Collaborative Health Outcomes Information Registry (CHOIR) Study. Pain. 2015;156(12):2627–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sturgeon JA, Darnall BD, Kao M-CJ, Mackey SC. Physical and psychological correlates of fatigue and physical function: A Collaborative Health Outcomes Information Registry (CHOIR) study. The Journal of Pain. 2015;16(3):291–8. e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sturgeon JA, Carriere JS, Kao M-CJ, Rico T, Darnall BD, Mackey SC. Social disruption mediates the relationship between perceived injustice and anger in chronic pain: a collaborative health outcomes information registry study. Ann Behav Med. 2016;50(6):802–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cameron RP, Gusman D. The primary care PTSD screen (PC-PTSD): development and operating characteristics. Primary Care Psychiatry. 2003;9(1):9–14. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kroenke K, Outcalt S, Krebs E, Bair MJ, Wu J, Chumbler N, et al. Association between anxiety, health-related quality of life and functional impairment in primary care patients with chronic pain. General hospital psychiatry. 2013;35(4):359–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Osman A, Barrios FX, Gutierrez PM, Kopper BA, Merrifield T, Grittmann L. The Pain Catastrophizing Scale: further psychometric evaluation with adult samples. J Behav Med. 2000;23(4):351–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Van Damme S, Crombez G, Bijttebier P, Goubert L, Van Houdenhove B. A confirmatory factor analysis of the Pain Catastrophizing Scale: invariant factor structure across clinical and non-clinical populations. Pain. 2002;96(3):319–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gershon RC, Rothrock N, Hanrahan R, Bass M, Cella D. The use of PROMIS and assessment center to deliver patient-reported outcome measures in clinical research. Journal of applied measurement. 2010;11(3):304. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pilkonis PA, Choi SW, Reise SP, Stover AM, Riley WT, Cella D, et al. Item banks for measuring emotional distress from the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS®): depression, anxiety, and anger. Assessment. 2011;18(3):263–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cella D, Riley W, Stone A, Rothrock N, Reeve B, Yount S, et al. Initial adult health item banks and first wave testing of the patient-reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS™) network: 2005–2008. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2010;63(11):1179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cook KF, Jensen SE, Schalet BD, Beaumont JL, Amtmann D, Czajkowski S, et al. PROMIS measures of pain, fatigue, negative affect, physical function, and social function demonstrated clinical validity across a range of chronic conditions. Journal of clinical epidemiology. 2016;73:89–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Farrar JT, Young JP, LaMoreaux L, Werth JL, Poole RM. Clinical importance of changes in chronic pain intensity measured on an 11-point numerical pain rating scale. Pain. 2001;94(2):149–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Buss AH, Perry M. The aggression questionnaire. Journal of personality and social psychology. 1992;63(3):452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fries JF, Spitz PW, Young DY. The dimensions of health outcomes: the health assessment questionnaire, disability and pain scales. The Journal of rheumatology. 1981;9(5):789–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kroenke K, Strine TW, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Berry JT, Mokdad AH. The PHQ-8 as a measure of current depression in the general population. Journal of affective disorders. 2009;114(1):163–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Hoffman JM, West SG, Sheets V. A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychological methods. 2002;7(1):83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ullman JB, Bentler PM. Structural equation modeling. Handbook of psychology. 2003:607–34. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hall AM, Kamper SJ, Maher CG, Latimer J, Ferreira ML, Nicholas MK. Symptoms of depression and stress mediate the effect of pain on disability. Pain. 2011;152(5):1044–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hung C-I, Liu C-Y, Fu T-S. Depression: an important factor associated with disability among patients with chronic low back pain. The International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine. 2015;49(3):187–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Carty J, O’Donnell M, Evans L, Kazantzis N, Creamer M. Predicting posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms and pain intensity following severe injury: The role of catastrophizing. European Journal of Psychotraumatology. 2011;2(1):5652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Otis JD, Keane TM, Kerns RD. An examination of the relationship between chronic pain and post-traumatic stress disorder. Journal of rehabilitation research and development. 2003;40(5):397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jenewein J, Moergeli H, Wittmann L, Büchi S, Kraemer B, Schnyder U. Development of chronic pain following severe accidental injury. Results of a 3-year follow-up study. Journal of psychosomatic research. 2009;66(2):119–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Darnall BD, Sturgeon JA, Kao M-C, Hah JM, Mackey SC. From catastrophizing to recovery: a pilot study of a single-session treatment for pain catastrophizing. Journal of pain research. 2014;7:219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Smeets RJ, Vlaeyen JW, Kester AD, Knottnerus JA. Reduction of pain catastrophizing mediates the outcome of both physical and cognitive-behavioral treatment in chronic low back pain. The Journal of Pain. 2006;7(4):261–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jensen MP, Turner JA, Romano JM. Changes in beliefs, catastrophizing, and coping are associated with improvement in multidisciplinary pain treatment. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology. 2001;69(4):655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kerns RD, Sellinger J, Goodin BR. Psychological treatment of chronic pain. Annual review of clinical psychology. 2011;7:411–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ehlers A, Clark DM, Hackmann A, McManus F, Fennell M. Cognitive therapy for post-traumatic stress disorder: development and evaluation. Behav Res Ther. 2005;43(4):413–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Schütze R, Rees C, Smith A, Slater H, Campbell JM, O’Sullivan P. How can we best reduce pain catastrophizing in adults with chronic noncancer pain? A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Journal of Pain. 2018;19(3):233–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Herbert MS, Malaktaris AL, Dochat C, Thomas ML, Wetherell JL, Afari N. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for Chronic Pain: Does Post-traumatic Stress Disorder Influence Treatment Outcomes? Pain Med. 2019;20(9):1728–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.McGeary D, Moore M, Vriend CA, Peterson AL, Gatchel RJ. The evaluation and treatment of comorbid pain and PTSD in a military setting: an overview. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2011;18(2):155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Otis JD, Keane TM, Kerns RD, Monson C, Scioli E. The development of an integrated treatment for veterans with comorbid chronic pain and posttraumatic stress disorder. Pain Med. 2009;10(7):1300–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]