ABSTRACT

The Acinetobacter baumannii RND efflux pump AdeABC is regulated by the 2-component regulator AdeRS. In this study, we compared the regulation and expression of AdeABC of the reference strains ATCC 17978 and ATCC 19606. A clearly stronger efflux activity was demonstrated for ATCC 19606. An amino acid substitution at residue 172 of adeS was identified as a potential cause for differential expression of the pump. Therefore, we recommend caution with exclusively using single reference strains for research.

KEYWORDS: Acinetobacter, antibiotic resistance, cloning, efflux pumps

INTRODUCTION

Infections with multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii in health care facilities are challenging due to limited treatment options (1). Antimicrobial resistance genes acquired by horizontal gene transfer are the main route toward multidrug resistance, and these genes are predominantly specific to single agents or classes (2). Contrary to this, intrinsic efflux mechanisms may contribute to reduced susceptibility to numerous antimicrobial classes simultaneously. The most common broad-spectrum efflux pumps in Gram-negative bacteria belong to the resistance-nodulation-division (RND) family. Besides their ability to pump out antimicrobials of different classes, they have been shown to affect susceptibility to diverse compounds used in medical practice, such as antiseptics, disinfectants, and detergents (3–6).

In A. baumannii, the RND efflux pump AdeABC, encoded on an operon and regulated by the two-component system AdeRS, has been shown to affect antimicrobial susceptibility and contribute to tigecycline resistance (7, 8). It was shown that single amino acid substitutions in AdeRS induce overexpression of AdeABC and are associated with antimicrobial resistance (9–11).

Bacteriological research into fundamental mechanisms of growth, metabolism, and antimicrobial resistance is mainly performed using a limited number of reference strains (12–14). For A. baumannii RND efflux investigations, the reference strains ATCC 17978 and ATCC 19606 are commonly used (7, 15). In this study, we compare and characterize AdeABC in terms of its regulation, expression, efflux activity, and role in antimicrobial susceptibility in these two A. baumannii reference strains.

We deleted adeRS in A. baumannii reference strains ATCC 17978 and ATCC 19606 according to the method of Stahl et al. (16). Briefly, the upstream and downstream regions of adeRS were integrated into pBIISK::sacB_kanR using the In-Fusion HD EcoDry cloning kit (TaKaRa Clontech, Saint-Germain-en-Laye, France) and primer pairs L49/L50 and L51/L52 or M66/M67 and M68/M69, respectively (Table S2 in the supplemental material). Transformed strains were selected overnight in 10 ml Luria-Bertani (LB) medium supplemented with 10% sucrose. Single colonies were obtained by plating appropriate dilutions onto LB agar with 10% sucrose. Colonies were tested for kanamycin sensitivity by replica plating and subjected to PCR to confirm the deletion of adeRS. To measure the expression of adeB, semiquantitative reverse transcription-PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed as described previously (17). Strains were grown in LB until mid-log phase. Samples were treated with RNAprotect (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), followed by RNA isolation using the RNeasy minikit (Qiagen). cDNA was synthesized using the QuantiTect reverse transcription kit (Qiagen). Finally, RT-PCR was performed in a LightCycler (Roche, Mannheim, Germany) with QuantiFast SYBR green (Qiagen) in triplicates using freshly prepared cDNA. rpoB was used as the reference gene and was analyzed alongside adeB. Statistical analysis was performed using the unpaired t test. Strains and primers are listed in Tables S1 and S2.

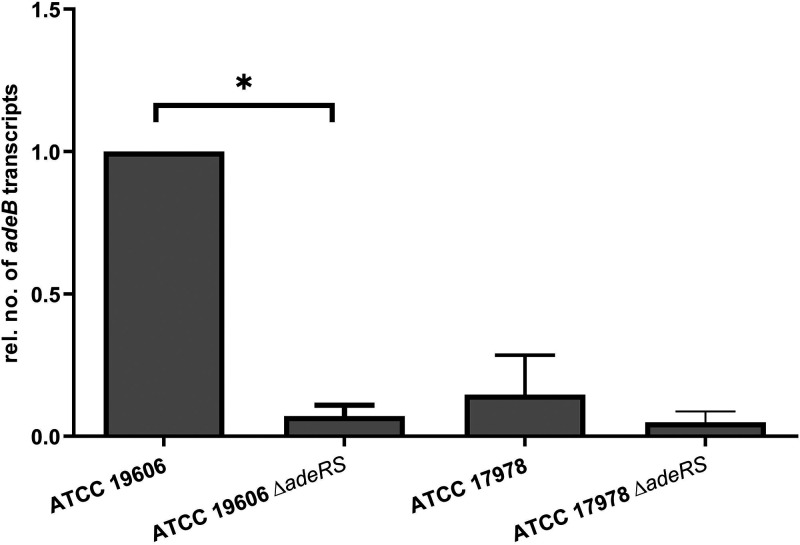

We found that in ATCC 19606, adeRS deletion inhibited the expression of adeB (P < 0.03). In contrast, adeB expression in ATCC 17978 was already low in the wild-type strain, and there was no significant difference in expression levels (P > 0.5) compared to its adeRS knockout derivate (Fig. 1).

FIG 1.

Relative adeB expression levels of A. baumannii ATCC 19606 and ATCC 17978 and the derived adeRS deletion strains determined by qRT-PCR. Results are represented as mean values ± standard errors of the means. Statistical analysis was done by using the unpaired t test on the absolute values. *, P < 0.03.

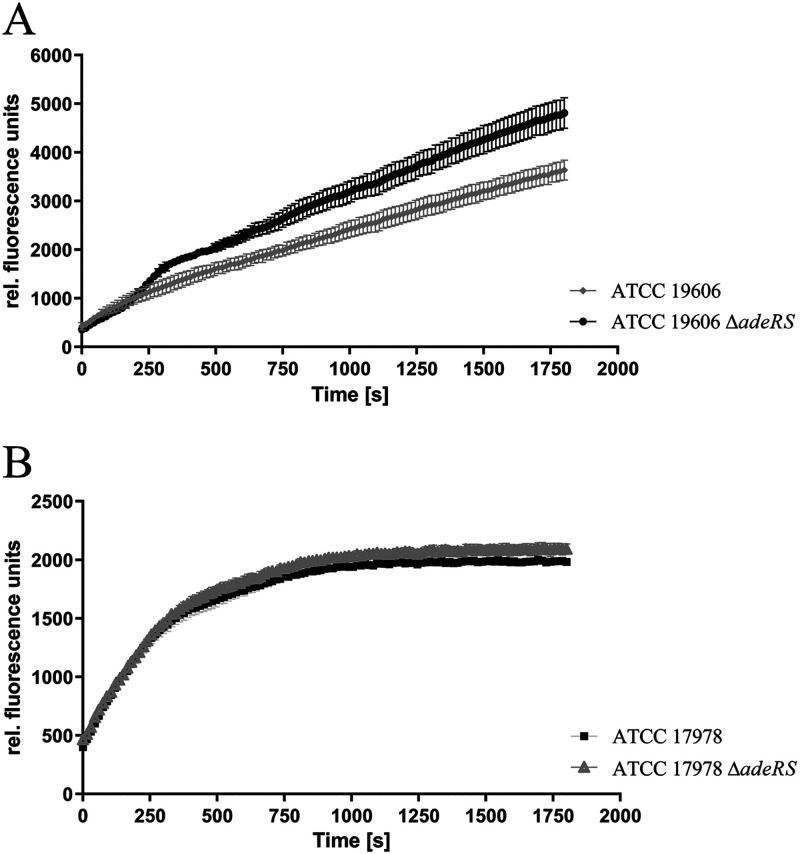

These findings were confirmed by accumulation studies using the AdeABC substrate ethidium bromide (18). Mid-log-phase cells were washed in potassium phosphate buffer (50 mM potassium phosphate buffer, 1 mM MgSO4 [pH 7.4]), adjusted to an optical density of 20 at 600 nm, and finally supplemented with 0.2% (wt/vol) glucose (Sigma-Aldrich, Steinheim, Germany). Cells were kept on ice during washing. Ethidium bromide (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) was applied at a final concentration of 10 μM. Fluorescence (excitation at 530 nm and emission at 600 nm) was measured in a 96-well Nunclon delta surface plate (Thermo Scientific) using an Infinite M1000 pro plate reader (Tecan, Crailsheim, Germany). Measurements were performed in triplicates, and mean values were analyzed for statistical significance using the unpaired t test. Accumulation of ethidium is facilitated by reduced expression of AdeABC, resulting in enhanced DNA binding of ethidium, which is revealed by increased fluorescence (9, 18, 19). Whereas ATCC 19606 ΔadeRS revealed higher fluorescence rates, indicating significantly reduced (P < 0.0001) efflux compared to its parental strain (Fig. 2), this effect of ΔadeRS was not detected for ATCC 17978 (P < 0.05) (Fig. 3).

FIG 2.

Ethidium bromide accumulation of ATCC 19606 and ATCC 19606 ΔadeRS (A) and ATCC 17978 and ATCC 17978 ΔadeRS (B). Fluorescence was measured every 10 s over 30 min. Data were collected from three independent experiments and are presented as mean values ± standard errors of the means.

FIG 3.

Relative adeB expression levels of A. baumannii ATCC 17978 ΔadeRS transformants determined by qRT-PCR. Results are represented as mean values ± standard errors of the means. Statistical analysis was done by using the unpaired t test on the absolute values (P = 0.0699).

Furthermore, deletion of adeRS in ATCC 19606 caused increased susceptibility to different antimicrobial classes, as determined by agar dilution or broth microdilution following the current CLSI guidelines (Table 1) (20). The biggest impact of adeRS deletion in ATCC 19606 was on azithromycin resistance, with a 16-fold-reduced MIC, emphasizing the affinity of azithromycin as a substrate of AdeABC. In accordance with our analysis of adeABC expression and efflux activity, the deletion of adeRS in ATCC 17978 had no detectable effect on antimicrobial susceptibility to the antimicrobials tested. All these findings illustrate the strain-dependent role of AdeABC expression, which should be considered in future efflux studies based on findings in a single reference or laboratory strain.

TABLE 1.

MICs of antimicrobials from different classes against ATCC 19606, ATCC 17978, and derived adeRS deletion strains

| Strain | MIC (mg/liter) ofa: |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMK | GEN | AZM | ERY | CIP | LVX | CHL | MEM | RIF | MIN | TET | TGCb | |

| ATCC 19606 | 8 | 16 | 32 | 32 | 1 | 0.5 | >128 | 0.5 | 4 | 0.25 | 8 | 1 |

| ATCC 19606 ΔadeRS | 2 | 8 | 2 | 16 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 128 | 0.25 | 4 | ≤0.125 | 4 | ≤0.125 |

| ATCC 17978 wild type | 2 | 1 | 2 | 16 | 0.25 | ≤0.125 | 64 | 0.5 | 4 | ≤0.125 | 1 | 0.25 |

| ATCC 17978 ΔadeRS | 2 | 1 | 2 | 16 | 0.25 | ≤0.125 | 64 | 0.5 | 4 | ≤0.125 | 1 | ≤0.125 |

| ATCC 17978 ΔadeRS(pJN17/04) | 2 | 0.5 | 2 | 8 | ≤0.125 | ≤0.125 | 64 | 0.5 | 4 | ≤0.125 | 1 | ≤0.125 |

| ATCC 17978 ΔadeRS(pJN17/04::adeRS17978) | 2 | 1 | 2 | 8 | ≤0.125 | ≤0.125 | 64 | 0.5 | 4 | ≤0.125 | 1 | ≤0.125 |

| ATCC 17978 ΔadeRS[pJN17/04::adeR(L172P)S17978] | 2 | 2 | 4 | 16 | 0.25 | ≤0.125 | 64 | 0.5 | 4 | ≤0.125 | 2 | ≤0.125 |

MICs were determined by agar dilution unless otherwise noted. AMK, amikacin; AZM, azithromycin; CHL, chloramphenicol; CIP, ciprofloxacin; ERY, erythromycin; GEN, gentamicin; MEM, meropenem; MIN, minocycline; LVX, levofloxacin; RIF, rifampicin; TET, tetracycline; TGC, tigecycline.

TGC MICs were determined by broth microdilution.

Previous studies have shown that mutational hot spots in RND-type efflux regulatory genes identified in clinical isolates cause differential expression of the corresponding RND efflux pumps and thus contribute to antimicrobial resistance (9, 11, 21). To identify the cause of the different roles of AdeRS for ATCC 19606 and ATCC 17978, the amino acid sequences were aligned and compared (22). AdeR of ATCC 17978 revealed only one amino acid substitution, a change of L to P at position 241 (P241L), which was predicted by the PROVEAN online tool to be neutral (23). AdeS of ATCC 17978, however, revealed a P172L amino acid substitution, which was classified as deleterious. Furthermore, previous studies have shown that this region is a hot spot for resistance mutations in Acinetobacter baumannii (10, 11, 24). Residue 172 is part of the dimerization and histidine-containing phosphotransfer domain, which includes the phosphorylation residue H149 and might therefore affect the activity of the sensor kinase. Moreover, analysis of available genome sequences revealed that clinical isolates predominantly harbor the P172 configuration, which is also present in other commonly used laboratory strains like ACICU and AYE (25).

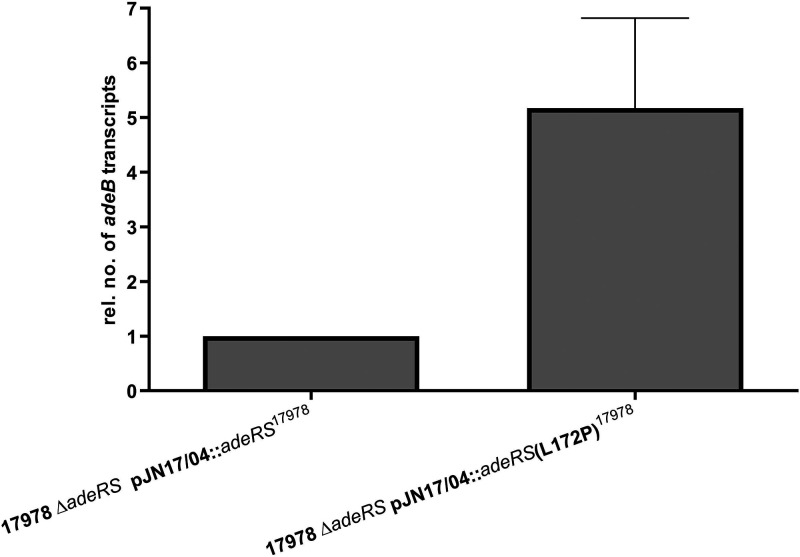

Subsequently, ATCC 17978 ΔadeRS was either recomplemented with wild-type adeRS of ATCC 17978 or adeRS subjected to Q5 site-directed mutagenesis (New England Biolabs) to obtain the nucleotide triplet coding for proline at residue 172 cloned into shuttle vector pJN17/04. Sanger sequencing (LGC Genomics GmbH Berlin, Germany) was used to confirm the corresponding nucleotide exchange. This single amino acid substitution caused an approximately 5-fold increase in the expression of adeB as determined by qRT-PCR performed in triplicates (Fig. 4).

FIG 4.

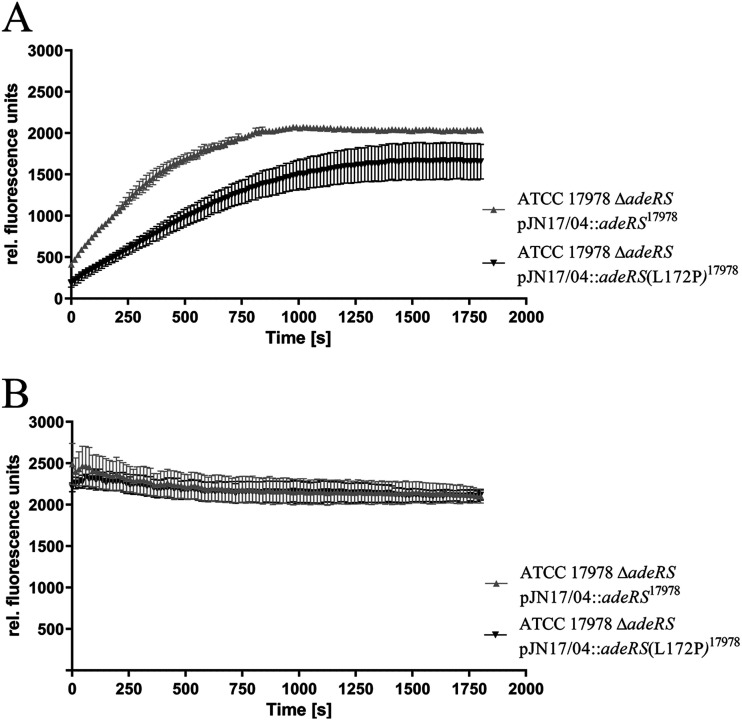

Ethidium bromide accumulation in untreated (A) and CCCP-treated (500 μm) (B) ATCC 17978 ΔadeRS transformants. Fluorescence was measured every 10 s over 30 min. Data were collected from three independent experiments and are presented as mean values ± standard errors of the means.

Analysis of ethidium accumulation revealed significantly lower accumulation levels (P < 0.0001) for ATCC 17978 ΔadeRS[pJN17/04::adeRS(L172P)17978] than for the strain recomplemented with the ATCC 17978 wild-type adeRS (Fig. 4). To show that the difference in accumulation levels was induced by altered efflux activity, ethidium accumulation was measured while the strains were subjected to the proton motive force uncoupler carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenylhydrazone (CCCP) (Sigma-Aldrich) at a final concentration of 500 μM. In this way, all proton-mediated efflux was inhibited, allowing the determination of the contribution of the amino acid substitution to efflux. The application of CCCP led to an alignment of the accumulation levels of both strains, indicating that the L172P amino acid substitution in AdeS caused increased efflux activity (Fig. 4).

Finally, the effect of the L172P amino acid substitution on antimicrobial susceptibility was determined, revealing a 2-fold increase in the MICs for gentamicin, azithromycin, erythromycin, ciprofloxacin, and tetracycline. These results confirm the increased efflux activity induced by the L172P amino acid substitution.

Overall, our results show that ATCC 17978 is comparatively weak in terms of AdeABC efflux because of its AdeS configuration, indicating that it is a rather inappropriate strain to study AdeABC efflux. Furthermore, it has to be considered that ATCC 17978 is derived from an isolate first described in 1951 (26) and therefore might not represent current A. baumannii isolates persisting in the hospital environment. This also applies for ATCC 19606, which was isolated in 1948.

Taking all these data into account, our results emphasize that focusing on single reference strains to characterize antibacterial resistance mechanisms can be problematic because of phenotypic variation within bacterial species based on genetic inconsistency.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Heng-Keat Tam, Membrane Transport Machineries group at the Institute of Biochemistry, Goethe University Frankfurt, for personal correspondence.

This work was supported by the German Research Council (DFG) through grant number FOR2251 (https://applbio.biologie.uni-frankfurt.de/acinetobacter/).

We declare no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available online only.

REFERENCES

- 1.Peleg AY, Seifert H, Paterson DL. 2008. Acinetobacter baumannii: emergence of a successful pathogen. Clin Microbiol Rev 21:538–582. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00058-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Levy SB, Marshall B. 2004. Antibacterial resistance worldwide: causes, challenges and responses. Nat Med 10:S122–S129. doi: 10.1038/nm1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fernandez L, Hancock REW. 2012. Adaptive and mutational resistance: role of porins and efflux pumps in drug resistance. Clin Microbiol Rev 25:661–681. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00043-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nikaido H, Pages JM. 2012. Broad-specificity efflux pumps and their role in multidrug resistance of gram-negative bacteria. FEMS Microbiol Rev 36:340–363. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2011.00290.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Poole K. 2004. Efflux-mediated multiresistance in gram-negative bacteria. Clin Microbiol Infect 10:12–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2004.00763.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li XZ, Plesiat P, Nikaido H. 2015. The challenge of efflux-mediated antibiotic resistance in gram-negative bacteria. Clin Microbiol Rev 28:337–418. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00117-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leus IV, Weeks JW, Bonifay V, Smith L, Richardson S, Zgurskaya HI. 2018. Substrate specificities and efflux efficiencies of RND efflux pumps of Acinetobacter baumannii. J Bacteriol 200:e00049-18. doi: 10.1128/JB.00049-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ruzin A, Keeney D, Bradford PA. 2007. AdeABC multidrug efflux pump is associated with decreased susceptibility to tigecycline in Acinetobacter calcoaceticus–Acinetobacter baumannii complex. J Antimicrob Chemother 59:1001–1004. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkm058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nowak J, Schneiders T, Seifert H, Higgins PG. 2016. The Asp20-to-Asn substitution in the response regulator AdeR leads to enhanced efflux activity of AdeB in Acinetobacter baumannii. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 60:1085–1090. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02413-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sun J-R, Jeng W-Y, Perng C-L, Yang Y-S, Soo P-C, Chiang Y-S, Chiueh T-S. 2016. Single amino acid substitution Gly186Val in AdeS restores tigecycline susceptibility of Acinetobacter baumannii. J Antimicrob Chemother 71:1488–1492. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkw002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gerson S, Nowak J, Zander E, Ertel J, Wen YR, Krut O, Seifert H, Higgins PG. 2018. Diversity of mutations in regulatory genes of resistance-nodulation-cell division efflux pumps in association with tigecycline resistance in Acinetobacter baumannii. J Antimicrob Chemother 73:1501–1508. doi: 10.1093/jac/dky083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Klockgether J, Munder A, Neugebauer J, Davenport C, Stanke F, Larbig K, Heeb S, Schöck U, Pohl T, Wiehlmann L, Tümmler B. 2010. Genome diversity of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 laboratory strains. J Bacteriol 192:1113–1121. doi: 10.1128/JB.01515-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Han M. 2016. Exploring the proteomic characteristics of the Escherichia coli B and K-12 strains in different cellular compartments. J Biosci Bioeng 122:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiosc.2015.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hijazi S, Visaggio D, Pirolo M, Frangipani E, Bernstein L, Visca P. 2018. Antimicrobial activity of gallium compounds on ESKAPE pathogens. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 8:316. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2018.00316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fernando D, Kumar A. 2012. Growth phase-dependent expression of RND efflux pump- and outer membrane porin-encoding genes in Acinetobacter baumannii ATCC 19606. J Antimicrob Chemother 67:569–572. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkr519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stahl J, Bergmann H, Gottig S, Ebersberger I, Averhoff B. 2015. Acinetobacter baumannii virulence is mediated by the concerted action of three phospholipases D. PLoS One 10:e0138360. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0138360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Higgins PG, Schneiders T, Hamprecht A, Seifert H. 2010. In vivo selection of a missense mutation in adeR and conversion of the novel blaOXA-164 gene into blaOXA-58 in carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii isolates from a hospitalized patient. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 54:5021–5027. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00598-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Giraud E, Cloeckaert A, Kerboeuf D, Chaslus-Dancla E. 2000. Evidence for active efflux as the primary mechanism of resistance to ciprofloxacin in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 44:1223–1228. doi: 10.1128/AAC.44.5.1223-1228.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Paixão L, Rodrigues L, Couto I, Martins M, Fernandes P, de Carvalho CC, Monteiro GA, Sansonetty F, Amaral L, Viveiros M. 2009. Fluorometric determination of ethidium bromide efflux kinetics in Escherichia coli. J Biol Eng 3:18. doi: 10.1186/1754-1611-3-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 2020. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing, 30th ed. CLSI supplement M100. CLSI, Wayne, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gerson S, Lucaßen K, Wille J, Nodari CS, Stefanik D, Nowak J, Wille T, Betts JW, Roca I, Vila J, Cisneros JM, Seifert H, Higgins PG. 2020. Diversity of amino acid substitutions in PmrCAB associated with colistin resistance in clinical isolates of Acinetobacter baumannii. Int J Antimicrob Agents 55:105862. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2019.105862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Corpet F. 1988. Multiple sequence alignment with hierarchical-clustering. Nucleic Acids Res 16:10881–10890. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.22.10881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Choi Y, Sims GE, Murphy S, Miller JR, Chan AP. 2012. Predicting the functional effect of amino acid substitutions and indels. PLoS One 7:e46688. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0046688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marchand I, Damier-Piolle L, Courvalin P, Lambert T. 2004. Expression of the RND-type efflux pump AdeABC in Acinetobacter baumannii is regulated by the AdeRS two-component system. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 48:3298–3304. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.9.3298-3304.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yilmaz Ş, Hasdemir U, Aksu B, Altınkanat Gelmez G, Söyletir G. 2020. Alterations in AdeS and AdeR regulatory proteins in 1–(1-naphthylmethyl)-piperazine responsive colistin resistance of Acinetobacter baumannii. J Chemother 32:286–293. doi: 10.1080/1120009X.2020.1735118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Piechaud D, Piechaud M, Second L. 1951. Etude de 26 souches de Moraxella-lwoffi. Ann Inst Pasteur (Paris) 80:97–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material. Download AAC00570-21_Supp_S1_seq1.pdf, PDF file, 0.1 MB (152.9KB, pdf)