Abstract

Objectives:

Effective regulations that reduce nicotine vaping among young adult dual (combustible and e-cigarette) users may differ depending on whether e-cigarettes are used for helping with smoking cessation. This laboratory experiment examined flavor and nicotine effects on e-cigarette product appeal among young adult dual users, stratified by reported use of e-cigarettes to quit smoking.

Methods:

Dual users aged 18–35 years that did (N = 31) or did not (N = 22) report vaping for the purpose of quitting smoking puffed e-cigarette solutions varied by a flavor (fruit, menthol, tobacco) and nicotine (nicotine-containing [6 mg/mL], nicotine-free) within-participant design. After puffing each solution, participants rated appeal.

Results:

In main effect analyses, non-tobacco (vs tobacco) flavors increased appeal and nicotine-containing (vs nicotine free) solutions reduced appeal similarly in dual users who did and did not vape to quit smoking. Interaction analyses found non-significant trend evidence that fruit and menthol flavors suppressed nicotine’s appeal-reducing effects more powerfully in those that did not vape to quit smoking (flavor × nicotine × vape to quit smoking, ps = .05–.06).

Conclusions:

Non-tobacco flavors might increase e-cigarette product appeal in young adult dual users overall and disproportionately suppress nicotine’s appeal-reducing effects in those that vape for purposes other than assisting with smoking cessation.

Keywords: e-cigarettes, flavors, tobacco regulatory science, young adults, product appeal

Observational surveillance data indicate that young adults, the age bracket of individuals with the highest vaping prevalence,1 predominantly use e-cigarettes marketed in non-tobacco flavors (eg, fruit or menthol).2 Laboratory product appeal testing, where young adult vapers provide appeal ratings (eg, liking, willingness to use again) in response to controlled administration of e-cigarette solutions in different flavors, is a useful paradigm that compliments observational data on flavor preferences. This paradigm demonstrates that flavorants in e-cigarette solutions increase appeal, irrespective of external factors such as variations in marketing or cultural trends.3–7

Laboratory product appeal testing indicates that puffs taken from non-tobacco flavored products generate higher appeal ratings than tobacco-flavored products in young adult nicotine vapers.3–7 There is also evidence that nicotine and flavor may have interactive effects on product appeal. Although nicotine generates rewarding neuropharmacological effects once absorbed,8 it is a respiratory irritant and has harsh and bitter qualities that can reduce immediate perceptions of product appeal.3–7 Non-tobacco flavors appear to be capable of masking nicotine’s aversive sensory effects (flavor × nicotine interaction effects).4,7,9 By doing so, non-tobacco flavors may allow young adults to continue vaping nicotine-containing e-cigarettes despite their aversive sensory properties, and therefore, may promote the acquisition of regular vaping patterns sustained by neuropharmacologically-mediated nicotine reinforcement.

Evidence that non-tobacco flavors enhance appeal and mask nicotine’s appeal-reducing properties has significant regulatory implications. However, challenges persist in interpreting these implications in young adult dual (combustible and e-cigarette) users, who exhibit biomarkers indicative of increased exposure to nicotine and cardiovascular/carcinogenic toxins.12,13 Some dual users vape with the intention of ultimately quitting smoking and could be in a temporary state of transition that precedes smoking cessation.10 Other dual users vape without any intention of quitting smoking and use e-cigarettes primarily as a means to self-administer nicotine in circumstances when and where smoking is not possible.11 E-cigarette product appeal research that segments the young adult dual-user population by those who do versus those who do not use e-cigarettes for the purpose of smoking cessation may more precisely inform the potential health impact of flavor regulation in dual users, the modal smoking status of young adult nicotine vapers.10

This study is a secondary analysis of data from a published laboratory experiment that tested the effects of fruit and menthol (vs tobacco) flavored and nicotine-containing (vs nicotine-free) e-cigarettes on product appeal among young adult vapers.14 The primary outcomes paper reported effects stratified across never smokers, former smokers, and current dual users. Grouping the participants in this way overlooks the heterogeneity within the dual-user subsample, which likely constitutes a mix of dual users that use e-cigarettes to quit smoking and those that do not use e-cigarettes as a smoking cessation aid. To address this gap, in this paper, we examined the main and interactive effects of flavor and nicotine, stratified by reported use of e-cigarettes to quit smoking, in the sample of dual users from the parent experiment.14

Dual users who vape for the purpose of quitting smoking may prefer e-cigarette products that closely resemble combustible cigarettes,15 which are inherently harsh and bitter. By contrast, dual users who vape for other reasons may be more open to e-cigarettes with qualities that depart from combustible cigarettes, including products in non-traditional flavors, such as fruit. Therefore, we hypothesized that the extent to which non-tobacco flavors (especially fruit) increase appeal, nicotine reduces appeal, and non-tobacco flavors suppress nicotine’s appeal-reducing effects would be more robust in dual users who do not use e-cigarettes to help quit smoking as compared to those who do use e-cigarettes to help quit smoking.

METHODS

Participants

Participants in the parent study (N = 100) met the following inclusion criteria: (1) 18–35 years old, (2) use nicotine-containing e-cigarettes (ie, e-liquid greater than 0 mg/mL) at least one day per week for one month or longer and reported use in the past 30 days. Exclusion criteria were: (1) current use of psychiatric or smoking cessation medication, (2) currently pregnant or breastfeeding, (3) plan to quit vaping in the next 30 days because vaping study devices were procedures.

All participants in the parent study were current e-cigarette users. Of this group, participants that reported smoking ≥100 combustible cigarettes in their lifetime and smoking in the past 30 days (N = 53) in addition to their current e-cigarette use, were considered dual users and included in the current analytic sample.

Design and Materials

We used a flavor × nicotine content double-blind within-participant factorial design. The procedure utilized e-cigarette solutions in 9 flavors – blackberry, strawberry, blueberry, watermelon, peach, Portal Blend menthol, Triple Menthol, Red USA tobacco, and Desert Ship tobacco (Dekang Biotechnology Co, Ltd). Each of the 9 flavors was used in both a 6 mg/mL free-base nicotine and a nicotine-free formulation, resulting in 18 total solutions. The mean Propylene Glycol/Vegetable Glycerin (PG/VG) was 51/49 (SD=4.3/4.3), and among the 9 nicotine-containing solutions, the mean nicotine concentration was 6.1 mg/mL (SD = 0.53). Solutions were administered via a variable-voltage Joyetech “Delta 23 Atomizer” tank device and “eVic Supreme” battery using a guided puff procedure. Each of the 18 e-liquid solutions was administered at 2 different power settings based on previous research:16,17 low power (7.3W [3.3 V@1.5Ω resistance]) and high power (12.3W [4.3V@1.5Ω resistance]), resulting in 36 total trials. The sequence of the 36 trials was administered in a randomized order, and pre-prepared prior to the study sessions to uphold the study blind.

Procedure

Potential participants were recruited using a variety of methods including Craigslist ads, social media ads, and flyers. After a telephone screen to determine study eligibility, eligible participants were invited to an in-person study visit and instructed to abstain from using any nicotine or tobacco products for at least 2 hours prior to arrival to prevent nicotine saturation during the procedure. Data were collected from January-August 2016. All study visits began at 12:00PM and lasted around 4 hours total. Prior to the study visit, staff who did not interact with the participants pre-prepared the 36 solutions in a random order generated by a random sequence generator. Participants and data collection staff were blind to the solutions administered at each trial. After informed consent, participants provided breath and saliva samples for carbon monoxide and salivary cotinine assessment, respectively. Participants then started the appeal product testing procedure, in which the experimental 36 trials were separated into 4, 9-trial blocks with 30-minute breaks separating each block. During each trial, participants followed a guided puffing procedure involving 2 puff cycles per trial: 10-second preparation, 4-second inhalation, one-second hold, and 2-second exhale intervals. After each 2-puff cycle, participants provided appeal ratings. Each trial was separated by one minute, during which participants were provided with water to prevent sensory carryover across trials. Furthermore, there were 4 additional filler trials using a flavorless solution. In between each 9-trial block, there was a longer, 30-minute break. As reported previously,14 there was no evidence that participants became habituated, fatigued, or sensitized to the procedure or to the appeal-altering effects of nicotine over the course of testing, as demonstrated by the non-significant trial number × nicotine or trial number × flavor effects. During the 30-minute breaks between each testing block, participants completed questionnaires that assessed demographic characteristics and tobacco product use history.

Measures

Use of e-cigarettes to quit smoking.

All participants included in the analytic sample were current dual (combustible and e-cigarette) users. Of this group, participants were split into 2 categories based on their response to the following question: “Are you using e-cigarettes as a way of quitting smoking?” Participants who answered “Yes” were classified as those who “Use E-Cigarettes to Quit Smoking” (N = 31), whereas participants who answered “No” were classified as those who “Does Not Use Cigarettes to Quit Smoking” (N = 22).

Appeal.

Using visual analogue scales (VAS; range 0–100), participants answered the following 3 appeal questions after each 2-puff trial: (1) “How much did you like it?” (2) “How much did you dislike it?” (3) “Would you use it again?” Rating anchors were ‘Not at all’ and ‘extremely’ for each measure, except use again (‘Not at all’ and ‘Definitely). For each of the 36 trials, a mean composite score of “Liking,” “Disliking,” (reverse-scored) and “Willingness to use again” was calculated. This previously-validated standardized e-cigarette appeal rating procedure has shown sensitivity to nicotine, device power, and flavor manipulations.9,14 Cronbach’s alpha was .93, and inter-item correlations were strong (rs ≥ .76) and previous factor analyses have demonstrated the unidimensionality of the 3-item composite score.9

Participant characteristics and potential covariates.

Participants completed demographic and tobacco product use history questionnaires to characterize the sample. These included items assessing gender, age, race, age at which participants started daily smoking of combustible cigarettes (years), number of cigarettes smoked per day (continuous), whether participants usually smoked menthol cigarettes (yes/no), number of e-cigarette puffs per vaping day (continuous), nicotine concentration of e-cigarette solution typically used (mg/mL; continuous), total duration of e-cigarette use (months), e-cigarette device type typically used (forced choice: cigalike, tank/pen, or advanced mod), and flavor of e-cigarette solutions typically used (fruit/dessert, menthol/mint, tobacco). Additionally, participants were administered the Fagerström Test for Cigarette Dependence (FTCD)18 measure of combustible cigarette dependence severity, and the Penn State Electronic Cigarette Dependence Index (PSECD),19 an e-cigarette dependence measure (range: 0–20). A semi-quantitative salivary cotinine measure – NicAlert™ test strips (LiveWellTesting. com, San Diego, CA) and breath carbon monoxide (CO) were collected to provide descriptive data on nicotine and combustible tobacco exposure, respectively. Participants’ reports of whether they were planning to quit smoking in the next 6 months (yes/no) also were collected for descriptive purposes.

Data Analysis

Descriptive comparisons of participant characteristics by vaping to quit smoking status were first performed. In the primary analysis, multilevel linear models (MLMs) of trial-level appeal outcome data nested within participants (36 observations per participant) were used, which modeled flavor (fruit, menthol, and tobacco [reference category]), nicotine content (nicotine-containing and nicotine-free [reference]), and flavor × nicotine content interactions as within-subject fixed effects. Initially, MLMs were tested separately in the subsamples of participants that did (N = 31) and did not (N = 22) report vaping to quit smoking, reported as unstandardized effect estimates (differences in appeal, by condition in 0–100 VAS units). Next, the subsamples were combined into a pooled dataset (N = 53) to test 2- and 3-way interactions with the vape to quit smoking between-subjects variable (yes vs no). Flavor × vape to quit smoking effects tested if flavor main effects varied by whether participants used e-cigarettes to quit smoking. Nicotine × vape to quit smoking effects tested group differences in nicotine main effects. Flavor × nicotine × vape to quit smoking effects tested for group differences in flavor × nicotine interaction effects. Demographic and tobacco product use characteristics that differed by use of e-cigarettes to quit smoking were adjusted for in the pooled sample moderation tests, which involved inclusion of the covariate construct’s main effect and its corresponding interactions with flavor and nicotine. The 3-way interaction tests included all 2-way and 3-way interaction term covariates (eg, covariate × flavor, covariate × flavor, and covariate × flavor × nicotine effects). Data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics Version 24 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY). Although statistical significance was set to .05 (2-tailed), non-significant trends (p < .10) were interpreted (with caution) as suggestive evidence as well because we did not want to overlook potentially promising findings in this first study ever addressing this topic, allowing the possibility for future replication studies.

RESULTS

Participant Characteristics

The analytic sample was 37.7% female, 18.9% Hispanic, 22.6% white, 35.8% black, and the average age was 26.5 years (SD = 4.4). The average duration of e-cigarette use was 18.43 months (SD = 15.39). Altogether, 77.4% of participants reported vaping primarily using fruit/dessert flavored e-liquids, 45.3% used an advanced personal vaporizer/mod, and the average number of puffs per day was 57.7 (SD = 67.7). Overall, 43.4% of participants smoked primarily menthol-flavored combustible cigarettes and smoked an average 5.9 cigarettes per day (SD = 5.7).

As expected, participants who reported vaping to quit smoking were much more likely to report a serious intention to quit smoking in the next 6 months (64.5%) than those who did not vape for the purpose of quitting smoking. Except for that characteristic, there were no statistically significant differences across any demographic or tobacco product use characteristic between participants who did (N = 31) versus did not (N = 22) report using e-cigarettes to quit smoking (Table 1). A non-significant trend (p = .05) indicated that a higher proportion of participants who did vape to quit smoking typically smoked menthol-flavored combustible cigarettes. This variable was included as a covariate in the subsequent tests of moderation of flavor, nicotine, and flavor × nicotine effects by use of e-cigarettes to quit analysis.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics of Participant Characteristics, by Use of E-cigarettes as a Quit-smoking Aid

| Stratified by Use of e-Cigarettes as a Quit-smoking Aid |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pooled sample (N = 53) | Yes (N = 31) | No (N = 22) | p-value for test of group difference | |

| Demographics | ||||

| Female Gender, % | 37.7% | 29% | 50% | .12 |

| Age, M (SD), years | 26.45 (4.42) | 26.94 (3.83) | 25.77 (5.14) | .35 |

| Race/Ethnicity, % | ||||

| Hispanic Ethnicity | 18.9% | 19.4% | 18.2% | .80 |

| White | 22.6% | 25.8% | 18.2% | |

| Black | 35.8% | 29.0% | 45.5% | |

| Asian | 11.3% | 12.9% | 9.1% | |

| Other | 11.3% | 12.9% | 9.1% | |

| Tobacco Product Use Characteristics | ||||

| Biomarkers, M (SD) | ||||

| Carbon monoxide, ppm | 7.04 (5.95) | 6.00 (3.83) | 8.50 (6.70) | .13 |

| Salivary cotinine semi-quantitative levela | 3.08 (1.14) | 3.00 (1.21) | 3.18 (1.05) | .57 |

| Combustible cigarettes | ||||

| Age started smoking every day, M (SD), yearsb | 18.77 (3.51) | 18.81 (3.66) | 18.71 (3.35) | .93 |

| Current cigarettes/day, M (SD) | 5.89 (5.67) | 5.63 (5.70) | 6.25 (7.66) | .72 |

| FTCD, M (SD) | 2.45 (1.94) | 2.39 (1.82) | 2.55 (2.13) | .77 |

| Usually smoke menthol cigarettes, % | 43.4% | 54.8% | 27.3% | .05 |

| e-Cigarettes | ||||

| PSECD, M (SD) | 7.34 (4.32) | 7.68 (4.48) | 6.86 (4.13) | .50 |

| Puffs per day, M (SD)c | 57.70 (67.66) | 69.42 (80.62) | 41.18 (39.54) | .14 |

| Nicotine concentration typically used, M (SD) | 11.06 (18.12) | 8.46 (11.07) | 14.71 (24.79) | .22 |

| Duration of e-cigarette use, M (SD), months | 18.42 (15.39) | 19.48 (17.17) | 16.91 (12.71) | .55 |

| e-Cigarette device type typically used, % | ||||

| Cig-a-like | 18.9% | 19.4% | 18.1% | .44 |

| Tank/pen | 35.8% | 29.0% | 45.5% | |

| Advanced personal vaporizer/mod | 45.3% | 51.6% | 36.4% | |

| E-cigarette flavor typically used, % | ||||

| Fruit/dessert | 77.4% | 80.6% | 72.7% | .16 |

| Menthol | 13.2% | 6.5% | 22.7% | |

| Tobacco | 9.4% | 12.9% | 4.5% | |

| Planning to quit smoking in the next 6 months | 41.5% | 64.5% | 9.1% | <.001 |

Note.

NicAlert Strip (Range 1–6).

One person removed for impossible value.

One outlier winsorized. p-value for omnibus group differences from χ2 (categorical variable) or t (continuous variable) test. FTCD = Fagerstrom Test for Cigarette Dependence; PSECD = Penn State Electronic Cigarette Dependence Index; ppm = parts per million. Sample size range from 47–53 across analyses due to differential patterns of missing data across variables.

Primary Analysis

Flavor and nicotine main effects, by use of e-cigarettes to quit smoking.

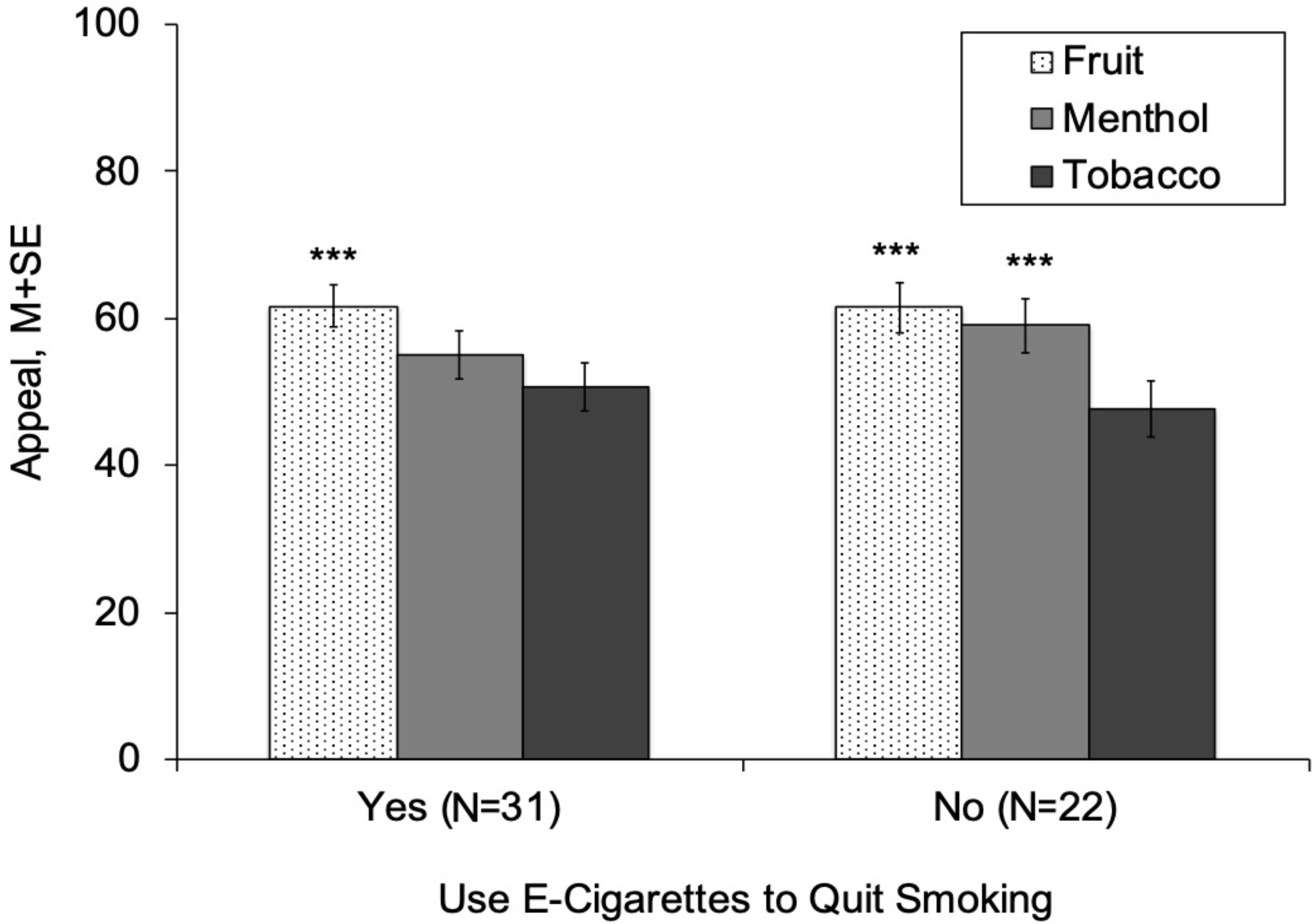

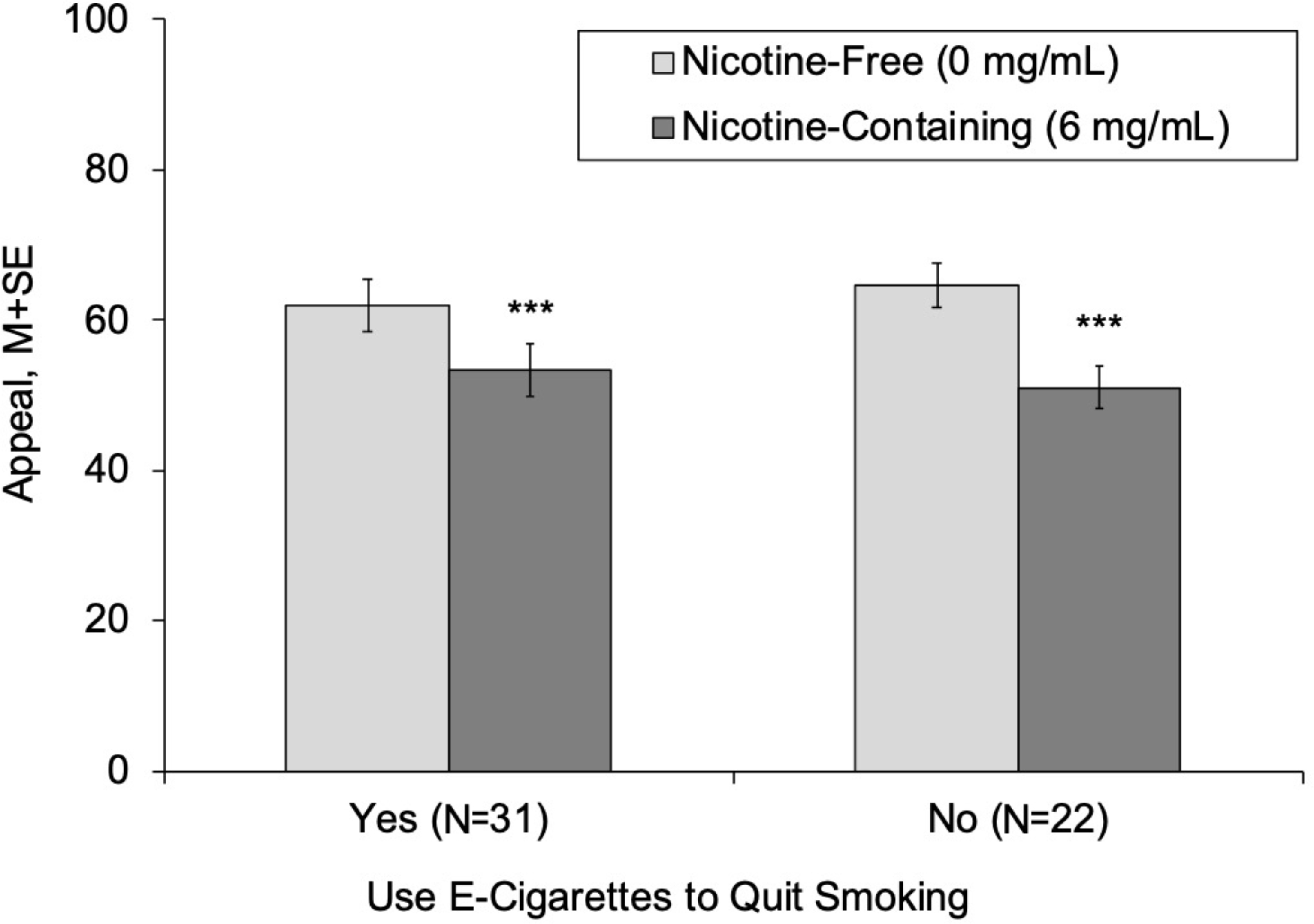

Use of e-cigarettes for the purposes of quitting smoking did not significantly moderate the appeal-increasing effects of fruit flavors after adjustment for menthol combustible cigarette smoking status (fruit × vape to quit smoking, p =. 29; Table 2). For both groups, appeal ratings were significantly higher for fruit-flavored (vs tobacco-flavored) e-liquid – the fruit effect estimate (fruit – tobacco difference) for those that did versus did not vape to quit smoking were 10.96 versus 13.77 respectively (Table 2, Figure 1). Vaping to quit smoking also did not significantly moderate menthol-flavored (vs tobacco-flavored) e-liquid’s effects on appeal as evidenced by nonsignificant adjusted fruit × vape to quit smoking effects. Menthol-flavored e-liquid significantly increased appeal in smokers who did not vape to quit smoking (menthol estimate [menthol – tobacco]: 11.29). In smokers who vaped to quit smoking, menthol-flavored e-liquid also increased appeal, but this effect was a non-significant trend (estimate: 4.36, p = .07; Table 2, Figure 1). Vaping to quit smoking did not significantly moderate the effect of nicotine-containing (vs nicotine-free) product variation on appeal (Table 2, Figure 2). Nicotine significantly reduced appeal among both those who did (nicotine estimate [nicotine-containing – nicotine-free]: −13.50) and did not (estimate: −8.57) vape to quit smoking.

Table 2.

Estimates of Flavor and Nicotine Effects on Appeal, by Use of e-Cigarettes as a Quit-smoking Aid

| Use e-cigarettes as a quit-smoking aid |

Difference in effect estimates, by use of e-cigarettes as quit-smoking aida |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (N = 31) |

No (N = 12) |

||||

| B (SE) | p | B (SE) | p | p | |

| Flavor and Nicotine main effects | |||||

| Fruit vs Tobacco flavor | 10.96 (1.97) | <.001 | 13.77 (2.52) | <.001 | .29 |

| Menthol vs Tobacco flavor | 4.36 (2.36) | .06 | 11.29 (3.02) | <.001 | .83 |

| Nicotine-containing vs Nicotine-free | −8.57 (1.57) | <.001 | −13.50 (1.99) | <.001 | .16 |

| Flavor × nicotine interaction effects | |||||

| Fruit vs Tobacco × Nicotine vs Nicotine-free | 1.18 (3.89) | .76 | 12.69 (4.87) | .01 | .05 |

| Menthol vs Tobacco × Nicotine vs Nicotine-free | 7.79 (4.65) | .09 | 20.29 (5.82) | .001 | .06 |

Note.

Nicotine = 6 mg/mL; Nicotine-Free = 0 mg/mL. Appeal = Average of “liking,” “willingness-to-use-again” and “disliking” (reverse-scored) (range 0–100). B(SE) = Effect Estimate and Standard Error of Effect Estimate.

Test of interaction between use of e-cigarettes as a quit-smoking aid (yes vs no) and respective flavor, nicotine, or flavor × nicotine interaction effect adjusted by interaction between menthol combustible cigarette use and respective flavor, nicotine, or flavor × nicotine interaction effect.

Figure 1.

Appeal of Fruit, Menthol, and Tobacco-flavored Solutions, by Use of E-cigarettes to Quit Smoking

Note.

***Appeal rating significantly different between respective flavor and tobacco flavor within respective group (p < .001).

Appeal = Average of “liking,” “willingness-to-use-again” and “disliking” (reverse-scored) (range 0–100).

Figure 2.

Appeal of e-Cigarettes with Nicotine-Containing and Nicotine-Free Solutions, by of Use E-cigarettes to Quit Smoking

Note.

***Appeal rating significantly different between respective nicotine-containing and nicotine-free conditions within respective group (p < .001).

Appeal = Average of “liking,” “willingness-to-use-again” and “disliking” (reverse-scored) (range 0–100).

Flavor × nicotine interaction effects, by use of e-cigarettes to quit smoking.

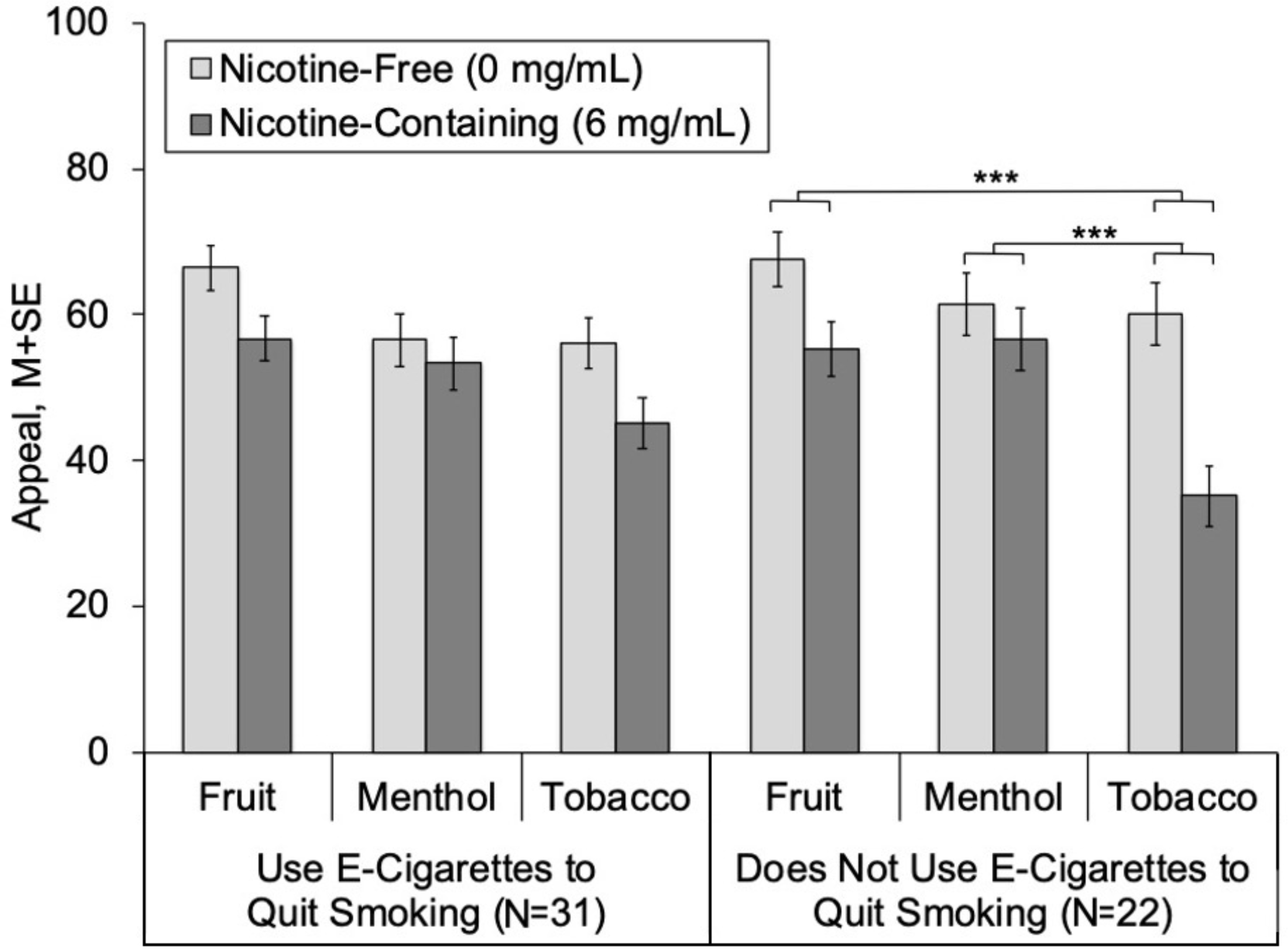

There was suggestive evidence that use of e-cigarettes to quit smoking moderated flavor × nicotine effects on appeal for both fruit and menthol e-liquid flavors, indicated by non-significant trends for flavor × nicotine × vape to quit smoking (ps = .05–.06; Table 2, Figure 3). In participants that did not report using e-cigarettes to quit smoking, nicotine-related reductions in appeal were significantly attenuated by fruit versus tobacco flavors (fruit × nicotine, p < .001), with a corresponding fruit × nicotine estimate of 12.69. The 12.69 estimate is the ‘difference-in-difference’ of the nicotine effect (nicotine-containing – nicotine-free difference score) for fruit flavors subtracted by the nicotine effect for tobacco flavors (−12.37 vs −25.06). In participants that vaped to quit smoking, however, fruit did not significantly attenuate the appeal-reducing effects of nicotine (fruit × nicotine estimate = 1.18, p = .76). For menthol (vs tobacco), attenuation of nicotine-induced reductions in appeal were highly robust in dual users that did not vape to quit (menthol × nicotine estimate = 20.29, p < .001), but were a non-significant trend in smokers that did vape to quit (menthol × nicotine estimate = 7.79, p = .09).

Figure 3.

Appeal of e-Cigarettes with Nicotine-Containing and Nicotine-Free Solutions, by Flavor and Use of E-cigarettes to Quit Smoking

Note.

*** Extent of difference in appeal between nicotine-containing and nicotine-free significantly differs between respective flavor and tobacco flavor within group (p < .001).

Appeal = Average of “liking,” “willingness-to-use-again” and “disliking” (reverse-scored) (range 0–100).

DISCUSSION

In this secondary analysis of product appeal data in young adult dual (combustible and e-cigarette) users, we found partial suggestive support for the hypothesis that the appeal-altering effects of non-tobacco e-liquid flavors and nicotine would be more robust in those that did not use e-cigarettes for the purpose of quitting smoking. In group-stratified flavor and nicotine main effect analyses, the appeal-enhancing effects of non-tobacco flavors and nicotine’s appeal-reducing effects did not significantly vary depending on self-reported vaping to help quit smoking. In group-stratified flavor × nicotine analyses, suggestive non-significant trend evidence was found that non-tobacco flavors suppressed nicotine’s appeal-reducing effects more powerfully in individuals that did not vape to quit smoking as compared to those who did vape to quit smoking.

Our findings add to the literature regarding the role of non-tobacco flavors across different sub-populations for whom vaping’s health implications might vary. In both groups of participants in this study, nicotine reduced appeal and fruit-flavored products were more appealing than tobacco flavors. Additionally, fruit/dessert flavors were the most common flavors participants typically used in their own devices, regardless of whether participants used e-cigarettes to quit smoking (Table 1). This is consistent with previous literature showing that non-tobacco flavored e-cigarettes are more commonly used and perceived as more appealing than tobacco-flavored e-cigarettes across numerous populations that vape.1,2,24–26 These findings add to evidence indicating that whereas most vapers prefer non-tobacco flavors, flavors disproportionately appeal to groups that derive little or no benefit from vaping.14,25–26 The relative magnitude of appeal-enhancement offered by non-tobacco flavors may be particularly large in never smokers per this parent experiment’s primary outcomes paper.14 As demonstrated here, we extend this evidence with suggestive results indicating that the magnitude of e-cigarette product appeal enhancement through suppression of nicotine’s aversive qualities might be disproportionately amplified in the subset of young adult dual users that do not use e-cigarettes as a smoking cessation aid and may be garnering little benefit by vaping.

There are several possible explanations as to why non-tobacco flavors did not robustly suppress nicotine’s appeal-reducing effects in dual users that vape for the purpose of quitting smoking. Perhaps factors that distinguish between dual users that did versus did not vape to quit, irrespective of their quit-smoking intentions, confounded the results. This is unlikely, however, because we examined 15 other demographic and tobacco product use characteristics that could have confounded the association between flavors and appeal (Table 1) and none differed between groups, with the exception of a nonsignificant trend indicating that menthol combustible cigarette use was more common among individuals that vaped to quit smoking. This difference would presumably bias the results toward the opposite direction of what we hypothesized because people who smoke menthol cigarettes might dislike nicotine’s harshness in e-cigarettes when paired with tobacco-flavored solutions that lack menthol or other potential masking flavorants. Indeed, previous literature indicates that menthol smokers report not being able to tolerate the harshness of nonmenthol combustible cigarettes.20,21

Our results also could reflect type I errors. Moderation effects did not surpass statistical significance cutoffs (fruit × nicotine × vape to quit smoking, p = .05; menthol × nicotine × vape to quit smoking p = .06). Although we cannot rule out this possibility, the likelihood of obtaining these results by chance is exceptionally low. To obtain flavor × nicotine × vape to quit smoking effects in the same direction for both the fruit and menthol pairwise interactions contrasts when both are truly null amounts to a probability of .0015 ([.05×.06] ÷ 2 [because these are 2-tailed p-values]).

Notwithstanding the considerations above, it is possible that non-tobacco flavors’ ability to mask nicotine’s bitterness or harshness might not robustly translate to greater product appeal for dual users that vape to quit smoking. Qualitative research suggests smokers find e-cigarettes to be more appealing quit-smoking aids than medicinal nicotine products (eg, nicotine gum) because e-cigarettes simulate the sensorimotor effects of combustible cigarettes.15,22 Thus, it is possible that individuals using e-cigarettes as quit-smoking aids might be more inclined to enjoy e-cigarette products with sensory attributes that mirror combustible cigarette smoke, which is inherently harsh and bitter. Suppression of nicotine’s bitterness- and harshness-enhancing effects in e-cigarettes by non-tobacco flavors may promote a vaping experience that departs from smoking combustible cigarettes, which might be less valued for those that vape for the purpose of finding a replacement for combustible cigarettes and ultimately quitting smoking. By contrast, dual users that vape for other reasons besides to help with smoking cessation might value the novel aspects of e-cigarettes, such as the variety of flavors and device customization, which has been reported anecdotally in previous research.23 Each of the aforementioned speculative points address the relative differences between the dual users that do versus do not vape to quit smoking, and it is important to reiterate that both dual-user groups preferred non-tobacco versus tobacco flavors, on the whole, in main effect analyses.

This study has limitations. First, like many laboratory product appeal testing studies, the sample size was modest. This secondary analysis utilized a subgroup of dual users from the original parent study. Whereas the MLM analysis used trial-level data with more than 1000 observations in the analysis (20 per participant), which afforded sufficient statistical power, smaller samples make generalization to the greater population of young adult dual users unclear. Second, differences in appeal between dual users who do and do not use e-cigarettes to quit smoking were moderate and non-significant trends (p < .10) were interpreted as suggestive evidence. Future replication studies are needed to determine if these findings are generalizable beyond this study. Third, because there is no psychometrically-supported multi-item measure of the contract of vaping to quit smoking, the current study relied on a single-item classification in order to split the analytic sample into 2 groups: those who do and do not use e-cigarettes to quit smoking. Although responses to this item strongly associated with an intention to quit smoking in the next 6 months, suggesting convergent validity of the measures, further development of multi-item measures, and additional information regarding vaping history and quitting intentions might be useful in future iterations of this line of research. Fourth, the study utilized a tank-style device and it is unclear whether results could be replicated using pod-style e-cigarettes, such as the JUUL – a device which has become increasingly popular in recent years, but was not yet widely available during the period of data collection for this study. Additionally, this study used free-base nicotine solutions. Other products that use nicotine salt solutions may be less harsh and yield different results.27 More research using these newly popular pod-style devices and nicotine salt solutions would be valuable. Fifth, although this methodology is ideal for understanding appeal during the vaping experience, it is not suited for studying neuropharmacologically-mediated reinforcement of psychoactive constituents, such as nicotine. Lastly, we studied 3 flavor classes and compared nicotine-containing versus nicotine-free solutions, which addresses broad dimensions of heterogeneity in e-cigarette solutions. There are substantial sources of “micro-heterogeneity” across products based on their specific flavorant constituents, quantitative variation in nicotine concentration, and various other factors that intersect flavor and nicotine. These sources of cross-product heterogeneity warrant consideration in future research.

In conclusion, this laboratory product appeal test of young adult dual e-cigarette and combustible cigarette users found that, when e-liquid flavor and nicotine concentration were considered independently, non-tobacco flavors increased appeal and nicotine reduced appeal similarly regardless of reason for vaping. When flavor and nicotine were considered concomitantly as interacting factors, we found suggestive non-significant trend evidence that non-tobacco flavors suppressed nicotine’s appeal-reducing effects more powerfully in individuals that did not vape to quit smoking versus those who vaped for other reasons. These results suggest that regulatory policies that limit the manufacture and sale of non-tobacco e-liquid flavors would impact both types of young adult dual users. The suggestive evidence of group differences in flavor × nicotine effects further raises the possibility that non-tobacco flavor regulations could disproportionately impact the sub-population of dual users that vape for other reasons besides for smoking cessation. If this finding is confirmed in future research, regulations that discourage perpetual dual use without substantially discouraging e-cigarette assisted smoking cessation in young adults warrant consideration.

Acknowledgements

This project was supported in part by Tobacco Centers of Regulatory Science (TCORS) award U54CA180908 from the National Cancer Institute (NCI) and Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and grants K01DA040043, K01DA04295, K24DA048160 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosure Statement

No conflicts of interest declared.

Human Subjects Approval Statement

This study was approved by the University of Southern California Institutional Review Board (protocol #: HS-15-00172); informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to data collection.

Contributor Information

Adam M. Leventhal, Department of Preventive Medicine, University of Southern California Keck School of Medicine, Los Angeles, CA; Department of Psychology, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA; Institute for Addiction Science, University of Southern California Keck School of Medicine, Los Angeles, CA.

Tyler B. Mason, Department of Preventive Medicine, University of Southern California Keck School of Medicine, Los Angeles, CA.

Sam N. Cwalina, Department of Preventive Medicine, University of Southern California Keck School of Medicine, Los Angeles, CA; Institute for Addiction Science, University of Southern California Keck School of Medicine, Los Angeles, CA.

Lauren Whitted, Department of Preventive Medicine, University of Southern California Keck School of Medicine, Los Angeles, CA; Institute for Addiction Science, University of Southern California Keck School of Medicine, Los Angeles, CA.

Marissa K. Anderson, Department of Preventive Medicine, University of Southern California Keck School of Medicine, Los Angeles, CA Institute for Addiction Science, University of Southern California Keck School of Medicine, Los Angeles, CA.

Carly E. Callahan, Department of Preventive Medicine, University of Southern California Keck School of Medicine, Los Angeles, CA; Institute for Addiction Science, University of Southern California Keck School of Medicine, Los Angeles, CA; Department of Sociology, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA.

References

- 1.Dai H, Leventhal AM. Prevalence of e-cigarette use among adults in the United States, 2014–2018. JAMA. 2019;322(18):1824–1827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bonhomme MG, Holder-Hayes E, Ambrose BK, et al. Flavoured non-cigarette tobacco product use among US adults: 2013–2014. Tob Control. 2016;25(Suppl 2):ii4–ii13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rosbrook K, Green BG. Sensory effects of menthol and nicotine in an e-cigarette. Nicotine Tob Res. 2016;18(7):1588–1595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Krishnan-Sarin S, Green BG, Kong G, et al. Studying the interactive effects of menthol and nicotine among youth: an examination using e-cigarettes. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2017;180:193–199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim H, Lim J, Buehler SS, et al. Role of sweet and other flavours in liking and disliking of electronic cigarettes. Tob Control 2016;25(Suppl 2),ii55–ii61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pullicin AJ, Kim H, Brinkman MC, et al. Impacts of nicotine and flavoring on the sensory perception of e-cigarette aerosol. Nicotine Tob Res. 2020; 22(5):806–813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.DeVito EE, Jensen KP, O’Malley SS, et al. Modulation of “protective” nicotine perception and use profile by flavorants: preliminary findings in e-cigarettes. Nicotine Tob Res. 2020;22(5):771–781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Benowitz NL. Pharmacology of nicotine: addiction, smoking-induced disease, and therapeutics. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2009;49:57–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leventhal AM, Cho J, Barrington-Trimis J, et al. Sensory attributes of e-cigarette flavours and nicotine as mediators of interproduct differences in appeal among young adults. Tob Control. 2019. December 18;tobaccocontrol-2019–055172. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2019-055172 [E-pub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coleman B, Rostron B, Johnson SE, et al. Transitions in electronic cigarette use among adults in the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) Study, Waves 1 and 2 (2013–2015). Tob Control. 2019;28(1):50–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Robertson L, Hoek J, Blank ML, et al. Dual use of electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS) and smoked tobacco: a qualitative analysis. Tob Control. 2019;28(1):13–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang JB, Olgin JE, Nah G, et al. Cigarette and e-cigarette dual use and risk of cardiopulmonary symptoms in the Health eHeart Study. PLoS One 2018;13(7):e0198681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goniewicz ML, Smith DM, Edwards KC, et al. Comparison of nicotine and toxicant exposure in users of electronic cigarettes and combustible cigarettes. JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1(8):e185937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leventhal AM, Goldenson NI, Barrington-Trimis J, et al. Effects of non-tobacco flavors and nicotine on e-cigarette product appeal among young adult never, former, and current smokers. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019;1(203):99–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Notley C, Ward E, Dawkins L, Holland R. The unique contribution of e-cigarettes for tobacco harm reduction in supporting smoking relapse prevention. Harm Reduct J. 2018;15(1):31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ramôa CP, Hiler MM, Spindle TR, et al. Electronic cigarette nicotine delivery can exceed that of combustible cigarettes: a preliminary report. Tob Control. 2016;25(e1):e6–e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sleiman M, Logue JM, Montesinos VN, et al. Emissions from electronic cigarettes: key parameters affecting the release of harmful chemicals. Environ Sci Technol. 2016;50:9644–9651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Fagerstrom KO. The Fagerström test for nicotine dependence: a revision of the Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire. Br J Addict. 1991;86(9):1119–1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Foulds J, Veldheer S, Yingst J, et al. Development of a questionnaire for assessing dependence on electronic cigarettes among a large sample of ex-smoking e-cigarette users. Nicotine Tob Res. 2015;17(2):186–192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kreslake JM, Wayne GF, Connolly GN. The menthol smoker: tobacco industry research on consumer sensory perception of menthol cigarettes and its role in smoking behavior. Nicotine Tob Res. 2008;10(4):705–715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wackowski OA, Evans KR, Harrell MB, et al. In their own words: young adults’ menthol cigarette initiation, perceptions, experiences and regulation perspectives. Nicotine Tob Res. 2018;20(9):1076–1084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pokhrel P, Herzog TA, Muranaka N, Fagan P. Young adult e-cigarette users’ reasons for liking and not liking e-cigarettes: a qualitative study. Psychol Health. 2015;30(12):1450–1469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vandrevala T, Coyle A, Walker V, et al. ‘A good method of quitting smoking’ or ‘just an alternative to smoking’? Comparative evaluations of e-cigarette and traditional cigarette usage by dual users. Health Psychol Open. 2017;4(1):2055102916684648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harrell MB, Weaver SR, Loukas A, et al. Flavored e-cigarette use: characterizing youth, young adult, and adult users. Prev Med Rep. 2016;5:33–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leventhal AM, Miech R, Barrington-Trimis J, et al. Flavors of e-cigarettes used by youth in the United States. JAMA. 2019;322(21):2132–2134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cullen KA, Gentzke AS, Sawdey MD, et al. E-cigarette use among youth in the United States. JAMA. 2019;322(21):2095–2103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barrington-Trimis JL, Leventhal AM. Adolescents’ use of “Pod Mod” e-Cigarettes - urgent concerns. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(12):1099–1102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]