Abstract

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a prototypic autoimmune disease characterized by antinuclear antibody (ANA) production. ANAs bind to DNA, RNA and complexes of proteins and nucleic acids and are important markers for diagnosis and activity. According to current models, ANAs originate from antigen-driven processes; nevertheless, antibody responses to both DNA and RNA binding proteins display features unexpected in terms of current paradigms for antigenicity. These differences may reflect disturbances in both B and T cells critical for autoreactivity. Clinically, ANA testing has new uses for determining classification as well as assessing eligibility for clinical trials. Studies of patients with established disease show frequent seronegativity. In this setting, seronegativity may indicate a stage of disease called post-autoimmunity in which the natural history of disease or effects of immunosuppressive therapies modifies responses. The new uses of ANA testing highlight the importance of understanding autoantigenicity and developing sensitive and informative assays for clinical assessments.

Keywords: Systemic lupus erythematosus, Antinuclear antibodies, Biomarkers, Monogamous bivalency, Nuclear molecules

1. Introduction

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a prototypic systemic autoimmune disease characterized by the abundant production of autoantibodies (1, 2). These antibodies target a wide array of nuclear, cytoplasmic and membrane molecules; in addition, autoantibodies can bind to both proteins and lipids circulating in the blood. Among these antibodies, those directed to nuclear molecules (antinuclear antibodies or ANAs) are the most distinctive and important for assessing diagnosis, classification and disease activity (3, 4). Furthermore, ANAs represent important markers for elucidating immunopathogenesis, with mechanisms regulating these responses viewed as central elements in the path to autoreactivity.

In the study of SLE, the focus on antinuclear antibodies as biomarkers began with the description of the LE cell phenomenon (5). This phenomenon was discovered fortuitously in the examination of a bone marrow sample but can also be demonstrated in blood and other biological fluids. As now recognized, the LE cell represents the engulfment of a cell nucleus by phagocytic cells following opsonization of the nucleus by antibody and complement. The LE cell assay is relatively crude and can be difficult to perform and standardize, limiting its utility for routine laboratory assessment. For clinical purposes, the LE cell phenomenon was rapidly replaced by the indirect immunofluorescence assay (IFA) which is much simpler; this test is also more frequently positive in patients with SLE (3, 6–8).

With the development of new technologies to assess the structure and function of both autoantibodies and autoantigens, the story of autoantibodies has seen remarkable changes over the years as the depth of analysis has dramatically increased. Nevertheless, salient questions remain similar: the fine specificity of ANAs for target molecules; the generation of ANAs from B cell populations; the extracellular expression of nuclear molecules; the immunological activity of immune complexes; and the biomarker functions of ANAs in the clinical setting. In considering these topics, this review will provide a context for understanding the manner in which serological testing has shaped understanding of the pathogenesis of SLE and has provided biomarkers that are now being used in novel and unexpected ways.

2. The assay of ANA

The assay of antinuclear antibodies by immunofluorescence (IFA or IIF) has long been the foundation of serological testing in SLE since virtually all patients with SLE have been considered to be serologically positive at least one time in their disease (3, 6–8). By its nature, the IFA does not reveal the specificity of the antibodies detected although the pattern of staining can provide insight into the intra-nuclear location of the antigen bound and thus its possible identity (9). In view of the relatively non-specific nature of the IFA, investigators used biochemical purification and molecular cloning to identify and characterize the target nuclear molecules. This information has allowed the development of many sensitive and specific assays, including solid phase immunoassays (SPAs) and laser addressable bead-base multiplex formats.

2.1. Types of ANAs

The transition to the use of molecularly defined products for immunoassays has represented an important chapter in the story of ANAs. As these studies have demonstrated, ANAs in SLE can be conveniently divided into two types on the basis of the biochemical properties of the molecules targeted. The first type includes antibodies to DNA and related nucleosomal components such as histones and DNA-histone complexes. Of antibodies to nucleosomal components, only anti-DNA antibodies have undergone extensive study and routine assay; the term anti-DNA will, therefore, be used for the anti-nucleosomal group (10, 11). The second type of ANA includes antibodies to RNA binding proteins (RBPs). These antibodies have also been called antibodies to extractable nuclear antigen (ENA), a termed derived from the nuclear extracts used for testing. Antibodies to RBPs bind to a series of RNA binding proteins (Sm, RNP, Ro and La) although, in the cell, RBPs are associated with specific RNA molecules (12). Thus, both types of ANA bind to complexes of proteins with DNA or RNA, with anti-DNA binding to a nucleic acid and anti-RBPs binding to proteins (3).

As shown in studies on the disease specificity of various ANAs, antibodies to double stranded mammalian DNA are quite specific for SLE, substantiating their role as classification or diagnostic biomarkers (10, 11, 13). In contrast, antibodies to RBPs show a different pattern of expression among autoantibody associated rheumatic diseases (AARDs). While antibodies to the Sm antigen are also specific for SLE, antibodies to the closely associated ribonucleoprotein (RNP) antigen have a broader distribution and can occur in a condition called mixed connective tissue disease (MCTD). Nevertheless, in patients with SLE, anti-Sm and anti-RNP commonly co-exist (12). Antibodies to Ro and La also have a wide distribution, showing expression in SLE, Sjogren’s syndrome and rheumatoid arthritis (RA). Of anti-RBPs, antibodies to anti-Sm are a marker for classification although, interestingly, anti-RNP antibodies are more commonly expressed in SLE.

2.2. Pathogenicity of ANA and relationship to disease activity

While antibodies to both nucleosomal components and RBPs may be pathologic, determining a specific role in disease (i.e., pathogenicity) can be difficult and depends on the disease manifestation, the pattern of antibody expression and the assay used for measurement. The ability to determine the relationship of an ANA to a disease manifestation also depends on the availability of quantitative assays and the assessment of antibody at the time of the clinical manifestations. Of ANAs, however, only anti-DNA is routinely assessed using quantitative assays at this time (10, 11, 13). Depending on the assay used and the manifestation considered, anti-DNA levels show evidence of a relationship to disease activity, with the association with disease activity its highest with nephritis. Anti-DNA levels are also included as evidence for disease activities with assessment tools such as the Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Disease Activity Index (SLEDAI).

The lack of a clear relationship of various ANA specificities (e.g., anti-Sm) with disease activity has two main explanations: infrequent assessment after the time of diagnosis or initial patient evaluation and the reliance of qualitative as opposed to quantitative assessment. Thus, certain antibodies may have a greater role in disease than usually believed although existing data may not be sufficiently robust to support that conclusion. In this regard, with current technology such as solid phase immunoassays, all antibodies can be measured quantitatively to provide a more complete picture of the pathogenic potential of these specificities.

In addition to differences in the biochemical properties of the target antigens, anti-DNA and anti-RBPs differ in their expression during disease course. Thus, anti-DNA can display widely varying levels of expression, showing spikes in levels during flares of activity and dramatic reductions and even disappearance with conventional immunosuppressive treatments, including glucocorticoids (14, 15). The magnitude of change in anti-DNA levels during a flare can be striking and even unprecedented among both ordinary, putatively protective antibodies to foreign antigens as well as of other autoantibodies. While accounting for the utility of anti-DNA as a biomarker for disease activity, these findings highlight the unique immunological features of this autoantibody response.

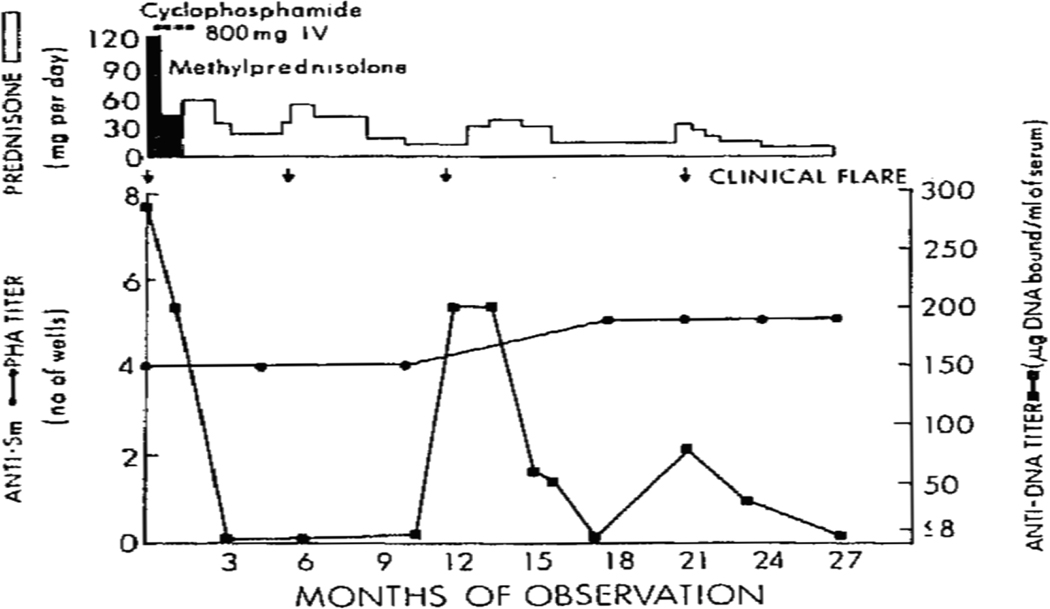

In contrast to the situation with anti-DNA, the expression of antibodies to RBPs tends to be relatively static over time although the paucity of studies on longitudinal expression of autoantibodies limits this conclusion (4). In a time-frame of a few years, however, levels of antibodies such as anti-Sm, anti-RNP or anti-Ro show little variation. Figure 1 provides an example of the temporal expression of anti-DNA and anti-Sm in a patient with SLE, showing the discordant expression. These findings suggest that, in contrast to anti-DNA, anti-RBPs are products of long lived plasma cells; as such, they resemble antibodies to vaccine antigens or naturally acquired responses to bacterial or viral molecules whose production over time is sustained.

Figure 1. Longitudinal expression of autoantibodies in SLE.

The figure illustrates the levels of anti-Sm and anti-DNA during the course of disease in a patient with SLE. Anti-Sm levels were determined by a passive hemagglutination assay (PHA) while anti-DNA levels were determined by a filter binding assay. Flares are indicated by arrows along with therapy in terms of prednisone dose and use of cyclophosphamide. As the figure indicates, while anti-DNA levels rise and fall, anti-Sm levels remained unchanged during the period of observations. Reprinted with permission from reference 15.

Since levels of anti-RBP antibodies may not vary much over time, these autoantibodies have not been viewed as mediators of disease flares although they could drive underlying immune disturbances that are more persistent. Thus, immune complexes with anti-RBP antibodies can stimulate interferon production by innate immune cells, leading to the generation of the interferon signature (16, 17). This signature, which results from interferon production following the activation of internal nucleic acid sensors by the RNA or DNA in the immune complex, appears persistent. Excessive production of interferon could provoke immunological abnormalities that lead to inflammation and autoreactivity in SLE even if ANA levels do not change significantly over time.

3. The binding of anti-DNA to DNA autoantigen

An important clue to the mechanism for ANA generation relates to the molecular properties of the antibodies and their fine specificity for antigenic determinants on the target molecules; these determinants are also called epitopes. Progress in understanding these issues has differed between anti-DNA and anti-RBPs, however; anti-DNA has received more investigation than anti-RBPs because of the seemingly unique expression antibodies to DNA in SLE and the value of anti-DNA as a biomarker for both classification (diagnosis) and disease activity. Indeed, anti-DNA antibodies have received more intense study at the molecular and cellular level than any other antibody response except those to the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) or possibly influenza (flu).

3.1. DNA-anti-DNA interactions

While the anti-DNA response has been dissected extensively, several factors have limited precise understanding of the binding specificities of these antibodies. The first factor relates to the nature of DNA as an antigen (18, 19). In comparison to a protein which has a defined sequence and structure (unless denatured for an immunoassay), DNA is a very large macromolecule and contains an enormous array of potential antigenic sites because of sequence variation along its length. While a nucleotide sequence could be the target of anti-DNA antibody, this determination is difficult because any antigenic sequence may be expressed multiple times along any DNA molecule; furthermore, an antigenic sequence could be commonly expressed by DNA molecules from different species, making it appear that the antigenic site is a conserved determinant and, thus, likely related to the phosphodiester backbone.

Another difference between antibodies to DNA and antibodies to proteins relates to the lack of paradigms for DNA antigen recognition; algorithms to predict antigenic sequences or motifs are also lacking. In contrast, the nature of antigenic sites on proteins is now well understood as a result of basic science investigation to understand immunogenicity and antigenicity as well as develop vaccines. In this regard, many studies on the structural basis of antigenicity of proteins come from studies in animals experimentally immunized with purified proteins in adjuvant. While the relationship between these model responses and naturally occurring responses to foreign proteins during infection is not fully known, the model studies have nevertheless established “rules” for antigenicity; these rules can be informatively applied to analyze the basis of autoantibody binding to protein autoantigen.

In contrast to the situation with autoantibodies to proteins, the experimental induction of anti-DNA antibodies by immunization has generally been unsuccessful. Even when bound to a protein carrier and presented in adjuvant, mammalian DNA elicits a very limited antibody response and, to this day, a model of SLE based on DNA immunization essentially does not exist (10). This situation limits many straightforward experiments to define the cellular basis of antibody induction. It also deprives the field of a paradigm to compare spontaneous and induced anti-DNA antibodies to reveal possible disturbances in antibody recognition of DNA that could illuminate the mechanisms of autoreactivity.

3.2. Epitope structure of DNA

Following the discovery of anti-DNA antibodies, many studies demonstrated that anti-DNA antibodies are specific markers for the diagnosis of SLE, a conclusion supported by the use of assays from a variety of DNA sources (e.g., mammalian DNA, bacterial DNA, plasmid DNA and synthetic polynucleotides). Other studies demonstrated that anti-DNA antibodies can bind single as well as double stranded DNA (18). Together, these observations suggested that epitope(s) recognized by anti-DNA antibodies resides on the DNA backbone, a highly charged structure because of the negatively charged phosphate groups that decorate its length. In general, antibody binding to single stranded DNA appears stronger than double stranded DNA, suggesting that structural flexibility favors antibody interaction; a double stranded molecule is more rigid than a single stranded one. Of note, preparation of double stranded DNA without single stranded regions and vice versa is technically difficulty (20).

In general, an antigen-driven response displays high avidity, with maturation of the response pointing to the role of somatic mutations in enhancing antigen binding. As the process of somatic mutation occurs in the germinal center B cells, the maturation also implies the location for the antibody generation (21). Measured in conventional assays, anti-DNA antibodies appear to be very avid. Coupled with studies indicating that murine monoclonal anti-DNA antibodies have somatic mutations in the complementarity determining regions (CDR) of the heavy chain leading to positively charge amino acids, these findings have suggested that anti-DNA emerges as a consequence of DNA antigen drive, with sites along the DNA backbone acting as the selecting determinants (22).

The story on DNA recognition antibody has had many twists and turns related to the uncertain relationship of these antibodies and disease activity and the ability of conventional anti-DNA assays to detect pathogenic specificities (11). While the binding to widely shared or conversed sites has long been considered fundamental to anti-DNA antigen recognition, a series of experiments over the years indicate the usual conceptualization of anti-DNA antibodies binding may not be correct and that the avidity of these responses have been misjudged.

3.3. The influence of DNA size on antigenicity

An antibody combining site can encompass a few nucleotides in length. Nevertheless, anti-DNA antibodies, in general, do not bind well to short oligonucleotides but rather require much longer stretches of DNA for stable interactions. For fluid phase DNA determinations, antibody binding requires lengths of DNA from 30 to 40 or more nucleotides for stable interaction although some sera or antibodies require pieces of DNA several hundred nucleotides in length (23, 24). For solid phase assays, the length of DNA for stable antibody binding is even greater, with detectable binding necessitating lengths of DNA of several thousand bases (25).

The requirement for such a large molecular structure for binding is unusual for a putatively antigen-driven response and likely relates to a mechanism of antibody interaction known as monogamous bivalency (23, 26, 27). In this mode of interaction, both Fab combining sites of a single antibody must be in contact with antigenic sites present on the same molecule, in this case, DNA. Since the distance between two Fab sites is approximately 140Å (depending on the isotype), a piece of DNA of that length is needed to allow both Fab sites to contact DNA in the fluid phase. For those sera that need even larger pieces of DNA for binding, it seems likely that antibody recognition occurs with sites that are dispersed along the DNA molecule such that a long piece is needed to contain two.

In solid phase assays, antibody binding of DNA is very limited with size fractionated DNA in lengths up to several thousand nucleotides although antibody binding occurs with purified unfractionated chromosomal DNA (25). An explanation for these results relates to a requirement of a conformational rearrangement of DNA such as looping or bending to bring two antigenic determinants into contact with both Fab binding sites of an IgG molecule. For solid phase assays, lower molecular weight DNA may be too adherent to solid phase supports to allow rearrangement. With high molecular weight DNA, much of the DNA may be free or unattached to the solid phase support and, therefore, behave as if soluble.

3.4. The binding of antibody fragments to DNA

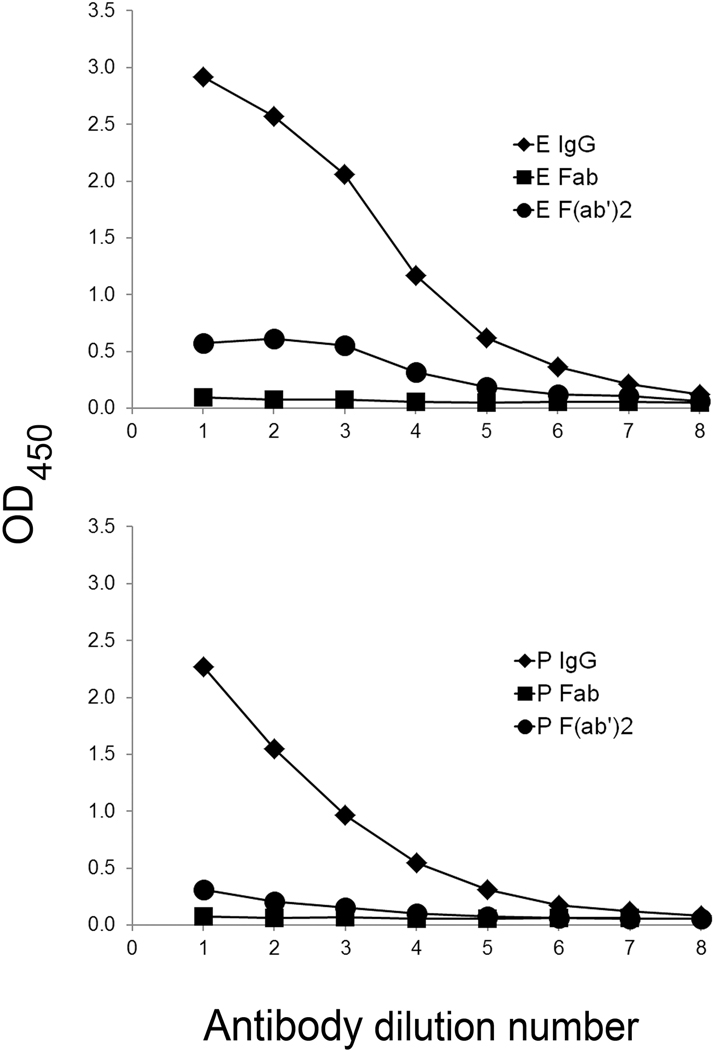

The importance of monogamous bivalency is demonstrated further in studies on the anti-DNA binding properties of Fab and F(ab’)2 fragments of purified IgG from patients with SLE (28). As shown in these studies using an ELISA, Fab fragments of IgG fail to bind DNA in an ELISA, a result consistent with monogamous bivalency; since a Fab fragment can bind only monovalently, it lacks sufficient affinity for stable interaction. In these experiments, F(ab’)2 fragments were also unable to bind DNA in the ELISA. This result is very surprising since F(ab’)2 fragments, like an intact IgG molecule, are bivalent. Figure 2 presents results of binding studies of sera from two patients with SLE.

Figure 2. The binding of antibody fragments to DNA.

The figure illustrates the binding of intact IgG as well as Fab and F(ab′)2 fragments of purified IgG from two patients with SLE. Anti-DNA levels were detected by an ELISA, using amounts of IgG or fragments with an equivalent number of binding sites. The figure shows the low activity of fragments. Control experiments (not shown) demonstrated activity of the fragments to a tetanus toxoid and EBV antigen preparations. While a lack of binding by Fab fragments to DNA is consistent with monogamous bivalency, the results with F(ab′)2 fragments indicate that the Fc fragment is contributing in unexpected ways to anti-DNA activity. Reprinted with permission from reference 28.

The requirement for an Fc fragment for anti-DNA activity raises a number of interesting possibilities that have not usually been considered in models for antigen-antibody interactions. Thus, the lack of DNA binding by the F(ab’)2 fragments suggests that the Fc portion of the IgG molecules may influence the conformation of the Fab binding sites to promote antigen interactions; the induction of structural changes by Fab and Fc portions of an antibody may thus be bidirectional. In another scenario, the Fc portion of an IgG could also contact DNA providing a third albeit weak binding site. Finally, Fc-Fc interactions may boost antibody binding by cross-linking adjacent IgG molecules. While these possibilities are all under investigation, together, they suggest that antibodies to DNA may not obey the rules for antigenicity generated in studies on experimental immunization either because of their origin in the setting of autoimmunity or the physical-chemical nature of DNA as an antigen.

3.5. Sequence specificity binding by anti-DNA

Together, these studies suggest that anti-DNA antibodies bind antigenic determinants that may be discrete and, while situated along the DNA backbone, they may not be the phosphodiester backbone itself. Evidence for the recognition of discrete antigenic sites that are sequence-dependent also comes from studies about the binding of sera as well as murine and human monoclonal antibodies to DNA (24, 29–32). These studies have suggested that monoclonal antibodies can bind selectively to DNA depending on the species origin of the DNA. The sequence of naturally occurring DNA is highly variable and depends on the base composition of DNA as well as extent of methylation; nevertheless, all naturally occurring DNA display the same phosphodiester backbone. Selective recognition, therefore, suggests binding of discrete epitopes.

Other evidence for the existence of sequence-specific recognition of DNA derives from studies on the binding of sera from normal human subjects (NHS) to bacterial or viral DNA (33–36). As these studies indicated, while sera from patients with SLE can bind similarly to all natural DNA, sera from NHS can bind to some bacterial DNA although these antibodies do not cross-react with mammalian DNA; the levels of antibodies to the bacterial DNA antigens were comparable to those found in sera of patients with SLE. A similar situation pertains to DNA from certain viruses. In their binding to bacterial DNA, sera from NHS differ from SLE sera in their apparent higher avidity binding to foreign DNA; NHS anti-DNA also show less dependence on ionic interactions as reflected in salt sensitivity and the effects of pH (37). The antibodies in NHS are mostly IgG2 isotype and, thus, differ from SLE anti-DNA antibodies which are predominantly IgG1 (36). The highly selective binding of NHS anti-DNA to foreign DNA also differs from that of so-called “natural autoantibodies” which are IgM.

The reason that the anti-DNA response of NHS was long missed relates to the manner in which the specificity of SLE has been interpreted and investigated. Since SLE antibodies had been considered to bind to the phosphodiester backbone, a structure shared by all DNA, studies on anti-DNA specificity have relied on a relatively few different DNA sources such as DNA from calf thymus, salmon sperm and E. coli; plasmid DNAs has also been used for assay since they are closed circles and lack ends which could lead to unwinding and confusion between single and double stranded structures. Simply, the bacterial DNA sources that were found antigenic had never been tested as antigens. Table 1 summarizes properties of anti-DNA antibodies.

Table 1.

Binding properties of anti-DNA antibodies

| Bind to conserved sites on DNA from different species |

| Reactivity with single stranded and double stranded DNA |

| Require large pieces of DNA for stable interaction |

| Charge-charge interactions |

| Monogamous bivalency |

3.6. Immune activity of foreign DNA

As is now well recognized, bacterial DNA can serve as a mitogen or pathogen associated molecular pattern (PAMP) and can induce anti-DNA production by experimental immunization (38). In normal mice the induced antibodies, like those in NHS, bind selectively to the foreign DNA used for immunization; in contrast, in NZB/NZW autoimmune mice, like those in patients with SLE, the induced antibodies can bind both bacterial DNA and mammalian DNA. Similar results were obtained with DNA from BK virus (39). These studies suggest that disturbances in the B cell repertoire, a feature of the autoimmune state, could facilitate a response to self DNA by a type of molecular mimicry, with the unusual mechanism of Fc-dependent monogamous bivalency allowing a cross-reactive response.

4. Autoantibody recognition of protein autoantigens

The story on autoantibody recognition of protein autoantigens in SLE differs from that of DNA related to the much more extensive investigation of the structural determinants of antigenicity of proteins; in addition, technologies to synthesize peptides readily provide vast arrays of antigens for testing. Assay with these peptide arrays can provide a detailed picture of the sequences recognized by sera or monoclonal antibodies and map decisively the portion of a molecule recognized by antibodies. While such array approaches are now available for DNA, they have not yet been used extensively, placing binding to protein autoantigens and nucleic acid autoantigens in separate realms.

4.1. The use of peptides to elucidate autoantibody binding

Peptide arrays have been used extensively to analyze the binding of antibodies to RBP antigens (40–44). These studies have been important in pinpointing the regions of these molecules that are antigenic and demonstrating sequence similarity to regions of viruses, most pertinently Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) (45). These studies provide clear evidence of shared sequences between foreign and self-antigen and furthermore provide a framework to chart the evolution of antibody specificity known as epitope spreading. In epitope spreading, following induction of antibodies to one part of an antigen, antibodies to other parts of the molecule develop or spread, leading to recognition of multiple determinants. Spread can also occur to other target antigens.

The binding of antibodies to peptidic determinants, however, does not rule significant or even preferential binding to conformational determinants that contain these peptides. While a small peptide can serve as an antigen, its structure can vary as it undergoes a transition from a random state to other structural forms. Thus, a peptide can be in equilibrium with a conformation in which the peptide exists in the intact molecule. Once a peptide displays that conformation, antibody binding can occur, often stabilizing the peptide in that conformation. The equilibrium between conformations is governed by a rate equation which determines the amount of the peptide in an appropriate conformation. Even if the amount of peptide in the conformation is limited, immunoassay for peptides can be very sensitive and detect very small amounts of antibody (43). This situation makes it difficult to assess the amount of antibody binding to different conformational states of an antigen unless direct comparison of the intact protein and peptide fragment is performed.

A study on the binding specificity of antibodies to the La antigen produced intriguing results relevant to the basis of antigenicity of protein autoantigens (46). In this study, the binding of antibodies from patients with SLE and Sjogren’s syndrome was compared to that of mice immunized with a recombinant La protein. The test antigens were synthetic peptides predicted to be antigenic on the basis of hydrophilicity and antigenicity indices; for the purpose of the assay, the peptides were conjugated to bovine serum albumin (BSA). Results of these studies indicated that, depending on strain, mice immunized with La produce antibodies that could bind to five of the six peptides predicted to be antigenic. In contrast, the patient sera did not bind to any of the putatively antigenic peptides. Interestingly, sera of autoimmune MRL-lpr/lpr mice expressed antibodies to only two of the six peptides tested.

The failure of patient sera to bind peptides is striking and seemingly at variance with other studies showing antibody reactivity of anti-RBPs to peptide antigens. Among explanations for the differences between these results, it is possible that the nature of the peptides used for assay leads to sensitivity differences and that the ELISA assay with synthetic peptides conjugated to BSA detects antibodies less well than do the assays based on overlapping peptide arrays. On the other hand, the peptides conjugated with BSA worked well as antigens with the induced mouse sera; these findings establish the activity of peptides as antigens, with the induced antibodies binding to protein regions predicted to be antigenic.

4.2. Antigen drive in autoimmunity

Every assay format has potential limitations in its detection of antibodies to a given protein or nucleic acid. While the most informative approach to delineate ANA specificity is not known, nevertheless, the studies on both anti-DNA and anti-RBP suggest that these responses may not conform to the rules that govern antigen recognition in normal hosts. For the anti-DNA system, (which lacks a well characterized model system for an induced response in immunized mice), the comparison between antibodies presented in NHS and SLE suggest differences in recognition of conserved determinants and non-conserved determinants. While the sites recognized by anti-DNA found in patients in SLE may be sequences, they appear to be widely shared; in contrast, for NHS, the sites are non-conserved and occur on only certain bacterial or viral molecules (35). For anti-DNA in SLE, the actual strength of binding of these antibodies may be low since an intact IgG structure with two Fab binding sites is needed for stable interaction; furthermore, for stable interaction with anti-DNA antibodies, DNA antigen must be large and flexible to allow structural rearrangement to facilitate monogamous bivalency. To the extent that these antibodies result from an antigen driven response, the molecular properties of the anti-DNA antibodies seem to indicate an aberrant and inefficient process.

Similarly, for antibodies to proteins, the role of antigen selection also appears aberrant since binding to sequences predicted to be antigenic may not occur (46). This conclusion, however, is dependent on the sensitivity of the assays using peptides as antigens; for definitive information on this issue, more rigorous and detailed studies are needed to define the extent to which antibodies bind preferentially to conformational determinants present in the intact protein as opposed to sequential determinants that can be mimicked by small peptides.

4.3. Cellular abnormalities in SLE

As shown in many studies, SLE is characterized by a multitude of functional disturbances of B cells, T cells as well as antigen presenting cells such as dendritic cells and macrophages; neutrophils are also abnormal although they play a less direct role in the induction of antibody responses (2). Given the array of functional immune disturbances, the generation of antibody responses in SLE-whether directed to foreign or self-antigen-is likely to be aberrant, affecting both qualitative and quantitative features of these responses. The meaning of “antigen selection” in this setting is uncertain although nevertheless critical to understanding the mechanisms by which self-tolerance is lost.

While studies of peripheral cells have documented many disturbances in immune cell activation of T cells, the study of antigen specific T cell responses has received only limited attention (47–50). In part, this situation reflects uncertainty in the identity of proteins involved in the induction of T cell as opposed to B cell responses. Antigens such as Sm or RNP are complexes that have multiple macromolecular components; thus, triggering of T cells could involve one or more proteins in the complex that are not necessarily the targets of B cells. Similarly, for the response to DNA, T cell help could result from induction by any of the histone as well as non-histone DNA binding proteins attached to DNA. In view of these uncertainties, the basis of T cell help for autoreactive responses remains unknown beyond the involvement of expected cytokines or populations such as T follicular helper cells and other T helper cell populations (51, 52).

Studies on the B cell compartment in SLE provide important insight into the pattern of self-antigen recognition. As these studies have indicated, tolerance defects can occur at various points in the generation and maturation of B cells, leading to a pre-immune repertoire enriched with autoreactive precursors (53–58). While the germinal center is the canonical location for antigen selection and somatic hypermutation, in SLE, autoantibody production may reflect extrafollicular pathways as well, with autoantibody producing cells arising from naïve B cell precursors as well as memory cells. The fine specificity and avidities of antibodies derived from these different pathways are not yet known, although specificity could change over time if the response arises de novo from naïve cells.

Together, these finding suggest that, while ANA may result from an antigen selection, functional differences in the signaling thresholds of B cell and T cells can lead to patterns of specificity that differ from those for foreign antigen, especially in model systems that involve adjuvant and hyperimmunization. Table 2 summarizes evidence that ANA responses are driven by antigen, recognizing that an autoimmune state may influence the outcome of such a process.

Table 2.

Evidence for Antigen Drive in ANA Responses

| IgG isotype |

| High affinity |

| Binding of multiple epitopes |

| Independent expression |

| Somatic mutations in CDR |

5. The properties of in vivo self antigen

An important advance in the study of autoantibodies in SLE has been the identification and molecular characterization of the target autoantigens. The identification of DNA as a target autoantigen preceded that for anti-RBPs by many years until the advent of technology for cloning protein molecules. The identification of target autoantigens allows the construction of highly specific immunoassays using cloned protein or synthetic peptides. For both anti-DNA and anti-RBP responses, however, the target antigens are embedded in complexes which contain multiple components that include both proteins and nucleic acids. While these components may affect antigenicity, the identity of the components that are essential parts of the complexes is also unknown especially for nucleosomes to which a large number of transcription factors and other proteins bind. As a result, the development of immunoassays with complexes or “less pure” antigens can be problematic in terms of standardization.

Despite the inherent difficulties of using “less pure” antigens, recent studies have provided a new perspective on the recognition of self-antigen in vivo as opposed to the in vitro setting of immunoassays. As currently conceptualized, SLE is a disease of immune complexes in which ANAs interact with nuclear molecules; this interaction can occur either in the blood to form circulating immune complexes or locally in the tissue (e.g., glomerulus) where self-antigen is released or generated. This model of disease, therefore, requires an elucidation of the mechanisms generating extracellular nuclear molecules as well as the properties of these molecules in either the physiological or pathophysiological setting. While the LE cell phenomenon provided compelling evidence for extracellular release of the cell nucleus, only in the last few years has the self-antigen part of the immune complexes received much investigative interest.

5.1. The extracellular expression of nuclear autoantigens

While ANAs could theoretically form immune complexes with any of the target antigens, most of the study on extracellular nuclear molecules has focused on the DNA system for a number of reasons. First, evidence for a role in disease of immune complexes seems most solid with the DNA-anti-DNA system. Thus, levels of anti-DNA can fluctuate with disease activity and anti-DNA is a criterion for disease activity (10, 11, 13–15). A second reason for the focus on DNA is technical and relates to the ability to detect even very small amounts of DNA in the blood by techniques such as polymerase chain reaction and molecular cloning and sequencing (59). In contrast, detection of Sm or RNP protein in circulating immune complexes is technically more difficult since the amounts are small and the sensitivity of proteomic approaches can be limited. Finally, “cell free” or circulating DNA has become a major focus of investigation because of the utility of circulating DNA as a biomarker in settings such as neonatal testing and malignancy (59).

For DNA, in vivo and in vitro studies indicate that this molecule can enter the blood cells in many conditions associated with cell death whether by necrosis, apoptosis or necroptosis (60, 61). Necrosis is a form of sudden cell death induced by physical or chemical trauma while apoptosis and necroptosis are both regulated forms of cell death mediated by enzymes that cleave protein and induce other molecular changes that affect cell integrity. Whereas apoptosis is considered to be non-inflammatory, necroptosis can be inflammatory. Another form of regulated cell death is pyroptosis which follows activation of the inflammasome. Both necroptosis and pyroptosis lead to lytic cell death and, therefore, the extensive release of cell contents including pro-inflammatory molecules such as cytokines and DAMPs (damage or death association molecules).

During apoptosis, both protein and nucleic acids are cleaved and rearranged, with certain autoantigens translocating into structures called blebs. In another death process, neutrophils can undergo NETosis in which the DNA in the cells is released in a high molecular form decorated by the contents of neutrophil granules to produce an anti-bacterial mesh or “NET” (62, 63). In these scenarios, DNA remains associated with histones in the form of nucleosomes; the disposition of proteins such as Sm or RNP is not well studied although it appears that RBPs leave cells separately from DNA.

5.2. The properties of circulating DNA

Even though dying cells can release high molecular weight DNA, in the blood, DNA appears, in general, to be low molecular weight and exist with lengths of about 166 base pairs which is the size of DNA wrapped around a single nucleosome (59). This finding suggests that DNA once outside the cell has undergone very extensive cleavage. Of note, in SLE, circulating DNA is shorter than other conditions which is perhaps surprising since there is a relationship between active SLE and levels of the DNases responsible for digesting extracellular DNA (64, 65). With activity, DNase levels are increased which would be expected to lead to higher molecular weight DNA. The short size of cell free DNA is especially notable for DNA from neutrophils since the putative function of a NET is to ensnare and entrap bacteria or fungi because of a large, dense network of DNA strands. While this high molecular structure may exist in the tissues, exudates or pus, in the blood, the DNA is degraded. In view of the size requirement for larger pieces of DNA for antigenicity, for some sera, the nucleosomal size of DNA could limit binding and immune complex formation.

5.3. Microparticles as a source of self antigen

Another distinctive feature of circulating DNA relates to its presence in microparticles. A microparticle is a type of extracellular vesicle (EV) which is released from cells during cell death; platelets, however, can release particles following activation (66). These particles are 0.1–1.0 microns in diameter and contain an ensemble of cell constituents. Particles released during apoptosis may derive from blebs which form during this death process; as part of the molecular rearrangement during cell death, nuclear macromolecules migrate into blebs which can then be released into the extracellular space. The function of blebbing is not known although it may facilitate the clearance of cellular debris. Approximately one-half of the DNA in the blood is soluble while the other half is particulate.

In contrast, RNA is mostly particulate likely because unprotected RNA outside of particles would be digested. Evidence from a variety of studies strongly suggest that microparticles are the source of DNA that form immune complexes (67–71). Thus, microparticles obtained from patient blood contain IgG as shown by proteomics analysis; flow cytometry can also document the presence of IgG on the particles. More direct proof of the antigenicity of particles comes from studies showing that sera of patients with SLE, sera from murine lupus models and murine monoclonal anti-nucleosomal antibodies can all bind to particles obtained from the supernatants of apoptotic cells. Further support for the importance of particles in immune complex formation comes from observations that levels of anti-DNA are related to the number of IgG-positive particles. For particles to serve as antigens for immune complex formation, the DNA must be on the surface or otherwise accessible to antibody interaction.

The relationship between particle binding by either patient sera or monoclonal anti-nucleosomal antibodies is not absolute, however. Despite their content of anti-DNA, some sera do not bind particles generated in vitro; similarly, only certain monoclonal anti-DNA antibodies can bind to particles, suggesting that fine specificity for DNA determines particle binding, perhaps because of the exposure of these sites on the particle surface (72). Together, these studies suggest that particles generated in vitro may be an informative source of antigen to assess anti-DNA binding since these structures may represent the form of DNA found in vivo more reliably than highly purified DNA sources usually used for immunoassays. The use of particles and related extracellular vesicles for assay could help resolve the question of why certain patients are serologically active but clinically quiescent when anti-DNA is assessed with pure DNA antigens. Perhaps the autoantibodies in the clinically quiescent patients, while capable of DNA binding, do not bind to DNA presented on the particle.

While particle binding could be a useful probe for ANA specificity, the structure of particles found in vivo is likely to be quite diverse, reflecting the composition of expressed proteins in the differentiated cells. In this regard, while a role of cell death in generating extracellular nuclear materials is likely, there is little information on the cells in SLE that are actually dying. Thus, the utilization of microparticles as antigens for autoantibody assessment could represent a new chapter in the autoantibody story, although advancement of this approach requires much more basic and clinical study. Table 3 summarizes properties of autoantigens targeted in SLE.

Table 3.

Properties of Target Autoantigens in SLE

| Complexes of proteins and nucleic acids |

| Important functions in all cells |

| Conserved structures among species |

| Cleaved or rearranged during apoptosis |

| Extracellular translocation during cell death |

| Shared determinants with bacterial or viral proteins |

6. Autoantibodies as biomarkers

Biomarkers provide valuable information for patient evaluation although there are several different kinds of biomarker function (Table 4). Unfortunately, in the search for new and actionable biomarkers, the distinction among these functions is sometimes lost. Thus, while the ANA is a valuable marker for diagnosis or classification, it does not function well as a screening biomarker since up to 20% of the otherwise healthy population is ANA positive (73). The utility of the ANA for assessing disease activity is also limited especially for the IFA whose subjective nature can limit quantitative assessment. The titer of the ANA simply reflects the amount of antibody present in the greatest quantity, obscuring the contribution of ANA in lower amounts. Quantitative abundance does not imply pathogenicity.

Table 4.

Types of Biomarkers

| Antecedent | Risk for disease |

| Screening | Subclinical Disease |

| Diagnostic | Overt disease |

| Staging | Disease severity |

| Monitoring | Disease activity |

| Prognostic | Future course |

| Theranostic | Response to therapy |

In contrast to the situation with ANA, assessment of anti-DNA is useful for assessing classification and diagnosis as well as disease activity. Theoretically, because of its specificity for SLE, anti-DNA testing could be used as a screening biomarker but the frequency of SLE in the population is too low for this use and, while anti-DNA is a more specific marker for SLE, it is less sensitive than the ANA. A similar situation pertains to the assay of anti-RBP antibodies for screening.

While screening of the general populations may not be feasible, study of high risk individuals (i.e., sisters or identical twins of a patient with SLE) could be more fruitful (74). The use of autoantibodies for screening is consistent with the existence of a pre-autoimmune state that occurs prior to the onset of obvious signs or symptoms of SLE. This state is characterized by the production of autoantibody as well as other markers of immune disturbances (e.g., cytokine disturbances) in the absence of clear-cut evidence of inflammatory disease manifestations (75, 76). As shown in seminal studies, this state can precede clinical disease by as much as 10 years (77). Interestingly, antibodies to the Ro antigen are among the earliest serological findings although, as noted, anti-Ro is not a defining antibody for SLE. With the progression of time, perhaps other autoantibodies appear related to epitope spreading.

6.1. ANA and anti-DNA as theranostic markers

More recently, both ANA and anti-DNA antibodies have received attention as theranostic biomarkers which is a type of biomarker that allows prediction of the response to a therapeutic intervention (78). In the context of clinical trials, the use of ANA and anti-DNA for this purpose began with the development of belimumab, a monoclonal antibody to BAFF/BLyS, for the treatment of active SLE. Following the failure of this product to reach its endpoint in the Phase 2 trial, the sponsor reanalyzed the data and showed efficacy of the product for those patients who were serologically positive. Serological positivity was defined as the presence ANA and/or anti-DNA. The subsequent Phase 3 studies targeted patients with serologically positive, clinical active SLE and were successful (79, 80). Subsequently, other sponsors have followed this approach and entry criteria for many studies now include evidence of serological disease activity.

The experience with belimumab was remarkable because of the high frequency of seronegativity in the Phase 2 patient population. In this and other studies, the screen failure rate can approximate 30% which is very surprising in view of the use of the ANA as a criterion for disease classification. In general, the frequency of ANA positivity in SLE is considered to be 95–99%, with the occurrence of ANA negative disease rare to the extent that it exists (81). Nevertheless, the experience with the clinical trials with SLE indicates a much higher frequency of ANA negative disease, a finding that has both practical and theoretical implications.

6.2. Seronegativity in SLE

The explanation for the high frequency of ANA negativity in the clinical trial population has been unexpected and may result from a number of factors. In general, the population of patients in a clinical trial, in general, have many years of disease and have received a variety of immunosuppressive medications that can affect B cells. Thus, a transition to a seronegative state may occur because of changes in immune cell function induced by prolonged therapy. It is also possible that ANA negativity is a part of the natural history of disease, with screening during a trial revealing a previously missed serological feature of disease. In general, ANA testing occurs primarily at the time of an initial patient evaluation. Once ANA positivity is found, there is little reason to repeat the test since the criterion for classification (or diagnosis) has been met; furthermore, ANA status has not been considered useful to assess prognosis or disease activity in part because quantification of IFA results can be difficult.

Another explanation for a high frequency of seronegativity in the screening for clinical trials is technical and relates to the performance characteristics of the available kits for IFA testing. While all kits utilize HEp2 cells, variations can occur because of differences in the culture and handling of cells, the fixatives used and the nature of the fluorescently labeled reagents for antibody detection; observer differences can also affect results. Indeed, recent studies have emphasized the importance of these variations, indicating that the frequency of ANA negativity in patients with established disease can be substantial depending on the kit used for assay. For example, in a cross-sectional study of 103 patients with established disease, the frequency of ANA negativity ranged from 4.9–22.3% by IFA (82). In another study of 181 patients entered into a trial of a monoclonal antibody to IL-6, the frequency of ANA negativity by IFA varied from 0.6–27.6% by IFA (83).

The variation in results among kits likely relates to specificity differences of antibodies as discussed above. Thus, the presentation of antigenic determinants may differ depending on the source of the antigen (e.g., cloned or purified from tissue); the manner in which it displayed (i.e., solid phase vs soluble); and assay conditions. The situation with anti-DNA assays is notable as variation among assays can be very large (84, 85). Likely these differences result from the physical-chemical properties of the DNA and the range of avidities of antibodies that can be detected. The correlation between results in the different assays is limited which can be confusing in routine patient care if results from one laboratory are positive and another is negative. In the trial setting, variation can determine patient eligibility. Furthermore, for products that are approved for active, autoantibody positive disease, the choice of both anti-DNA and ANA results could affect the ability of a provider to prescribe the product.

6.3. The impact of assay kit on serological findings

In the absence of data on the most relevant specificity for detection and the relationship to pathogenicity and disease activity, the choice of an assay kit is entirely uncertain. In this regard, some data suggest that, over time, patients with SLE express similar anti-DNA antibodies, leading to consistent results with a given assay although the antibodies may be missed by another assay (84). These findings are of interest with respect to the idea that anti-DNA antibodies emerge from naïve B cells (56). In that scenario, the properties of antibodies produced may differ in terms of fine specificity, avidity and assay detection. Longitudinal studies on many patients screened with a panel of assays are needed to address the question of whether anti-DNA specificities are gained or lost over time.

One solution to the problem of assessing trial eligibility is to use multiple IFA and SPA assays to capture as many positive responses as possible, thereby reducing screen failure rate. On the other hand, use of an assay that leads to a fair degree of ANA negativity can be useful in sub-setting patients even if the basis for variable detection is not clear. In the belimumab studies, ANA status provided useful information to allow a successful study, with seropositivity helping to ensure diagnosis as well as illuminate certain immunological features that can be associated with response (79, 80).

6.4. Conundrums in assay selection

Interestingly, in the study on serological status of patients in an anti-IL-6 trial, those who were negative by IFA with the kit that the sponsor had used showed lower amounts of antibodies to the RBP molecules as well as a lower frequency of the so-called interferon signature (83). Had the belimumab clinical trial utilized a kit that produced essentially 100% ANA positivity, the theranostic information would have been lost, producing the situation of the unsuccessful Phase 2 study. Given many different assay kits that are now available for measuring ANA, anti-DNA and anti-RBPs, a well-designed trial could help identify a companion diagnostic or theranostic biomarker to rationalize and standardize serological testing for the conduct of clinical trials. Similar considerations pertain for the prescription of products for active, autoantibody positive SLE.

6.5. Dynamics of ANA expression during disease

While the uncertainty in assays complicates the interpretation of serological status of patients with established disease, studies now suggest that autoantibody production may change over time, with patients both gaining and losing individual antibodies (86). By analogy with pre-autoimmunity, this stage of lupus can be termed post-autoimmunity, with changes in antibody production related to either treatment or disease natural history. Future studies, therefore, are needed to evaluate serology over the course of disease, determining a relationship to remission and identifying treatments that may diminish autoantibody production.

7. The role of ANA testing in new EULAR-ACR classification criteria

The other area where ANA testing is undergoing change concerns the development of new criteria for the classification of SLE by the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) and the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) (87, 88). While in previous criteria sets from the ACR and the Systemic Lupus Collaborating International Clinics (SLICC), the ANA was one criterion for classification (89, 90), in the new criteria, a positive ANA is required for further consideration; in this system, clinical manifestations receive a varying number of points, with classification occurring when a total of >10 is reached.

7.1. IFA and SPA in serological determinations for classification

The original version of the criteria specified the IFA as the assay for ANA determination based on the idea that SLE is almost invariably ANA positive. This idea was supported by a comprehensive review and meta-analysis of published studies which demonstrated that the frequency of ANA positivity by IFA was 95.9% depending on titer (91). Because availability of the IFA can be limited, the final version of the criteria allows the use of solid phase assays for ANA determination. The utilization of SPAs is very reasonable for classification since such assays are widely used and many of the kits perform well. Certainly, clinical laboratories have a preference for SPAs and bead-based multiplex assay because of efficiency and ease of performance. A literature review on the performance characteristics of SPAs comparable to that for IFA has not yet been published.

The experience with ANA testing in the trial setting raises caution about its use in the setting of classification pending more data on kit performance in the specific setting of disease classification for SLE as opposed to assessing serological findings in the evaluation of patients with an autoantibody associated rheumatic disease. In this regard, the time frame for assay performance for classification may need greater specification since classification could occur and may occur at any stage of disease. As studies on patients with established disease indicate, the use of certain kits could prevent classification of as many as 20–30% of patients depending on which kit is used. Reliance on historical results for ANA testing can be problematic especially if the patient is the source of information.

8. Conclusion

The story of autoantibody production is one of the longest running in the field of laboratory testing and continues to provide new insights as innovation in technology allows analyses of greater depth and precision. The increasing utilization of the ANA as a theranostic biomarker and recent establishment of the ANA as the ultimate classification criterion provide an impetus to further the development of new assays to meet the changing needs for serological assay for clinical and investigation purposes. Given the power of current laboratory science, the next chapters of the evolving story of autoantibodies in SLE should be exciting, challenging and illuminating and keep SLE at the forefront in studies on the mechanisms of autoimmunity.

Highlights.

Antinuclear antibodies (ANA) bind to nuclear molecules with unique properties

Anti-DNA and antibodies to RNA binding proteins have distinct patterns of expression

Antibodies bind to DNA by a mechanism called monogamous bivalency

Antinuclear antibody responses show features of antigen drive

ANA responses may evolve over time during post-autoimmunity

The use of ANA for classification raises questions about the best assays for this purpose

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a VA Merit Review grant and an NIH grant (AR073935).

Professor Josef Smolen

It has been my great good fortune to have Josef Smolen as a friend and colleague. Josef is a remarkable individual who is an outstanding investigator, clinician and thinker. Josef has advanced the care of patients with rheumatic disease. He has galvanized the specialty with ideas like treat-to-target and he has inspired an historic era of international cooperation and collegiality. Josef and I have collaborated scientifically on studies regarding systemic lupus erythematosus and we worked closely for many years on a clinical trial on rheumatoid arthritis to assess the window of opportunity hypothesis. I have attended scientific meetings he has masterfully organized; he is a fantastic host. Most recently, I have served as an Associate Editor of Annals of Rheumatic Disease which Josef is leading with characteristic passion and brilliance. In all my interactions with Josef, I have been impressed by his boundless energy, vibrant personality and extraordinary knowledge. Josef knows about everything and, along with the most recent papers in Science and Nature, he can discourse on the architecture of buildings in Vienna, the art exhibit at the Albertina or Kunsthistorisches and the stars of the current production of The Magic Flute at the Wiener Staatsoper. I am delighted to contribute to this issue of Journal of Autoimmunity and have the opportunity to honor Josef Smolen, a luminary in rheumatology and a giant in all of medicine.

David S. Pisetsky, MD, PhD

Professor of Medicine and Immunology, Duke University Medical Center, Medical Research Service, Durham VA Medical Center, Durham, NC 27710 USA

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Kaul A, Gordon C, Crow MK, Touma Z, Urowitz MB, van Vollenhoven R, et al. Systemic lupus erythematosus. Nature reviews Disease primers. 2016;2:16039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tsokos GC, Lo MS, Costa Reis P, Sullivan KE. New insights into the immunopathogenesis of systemic lupus erythematosus. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2016;12(12):716–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Agmon-Levin N, Damoiseaux J, Kallenberg C, Sack U, Witte T, Herold M, et al. International recommendations for the assessment of autoantibodies to cellular antigens referred to as anti-nuclear antibodies. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73(1):17–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pisetsky DS. Antinuclear antibody testing - misunderstood or misbegotten? Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2017;13(8):495–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hepburn AL. The LE cell. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2001;40(7):826–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kavanaugh A, Tomar R, Reveille J, Solomon DH, Homburger HA. Guidelines for clinical use of the antinuclear antibody test and tests for specific autoantibodies to nuclear antigens. American College of Pathologists. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2000;124(1):71–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Solomon DH, Kavanaugh AJ, Schur PH. Evidence-based guidelines for the use of immunologic tests: antinuclear antibody testing. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;47(4):434–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meroni PL, Schur PH. ANA screening: an old test with new recommendations. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:1420–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wiik AS, Hoier-Madsen M, Forslid J, Charles P, Meyrowitsch J. Antinuclear antibodies: a contemporary nomenclature using HEp-2 cells. J Autoimmun. 2010;35(3):276–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rekvig OP. The anti-DNA antibody: origin and impact, dogmas and controversies. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2015;11:530–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pisetsky DS. Anti-DNA antibodies - quintessential biomarkers of SLE. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2016;12(2):102–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ching KH, Burbelo PD, Tipton C, Wei C, Petri M, Sanz I, et al. Two major autoantibody clusters in systemic lupus erythematosus. PloS one. 2012;7(2):e32001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hahn BH. Antibodies to DNA. N Engl J Med. 1998;338(19):1359–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schur PH, Sandson J. Immunologic factors and clinical activity in systemic lupus erythematosus. N Engl J Med. 1968;278(10):533–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McCarty GA, Rice JR, Bembe ML, Pisetsky DS. Independent expression of autoantibodies in systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol. 1982;9(5):691–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kirou KA, Lee C, George S, Louca K, Peterson MG, Crow MK. Activation of the interferon-alpha pathway identifies a subgroup of systemic lupus erythematosus patients with distinct serologic features and active disease. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52(5):1491–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weckerle CE, Franek BS, Kelly JA, Kumabe M, Mikolaitis RA, Green SL, et al. Network analysis of associations between serum interferon-alpha activity, autoantibodies, and clinical features in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63(4):1044–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stollar BD. The specificity and applications of antibodies to helical nucleic acids. CRC Crit Rev Biochem. 1975;3(1):45–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pisetsky DS. Standardization of anti-DNA antibody assays. Immunol Res. 2013;56(2–3):420–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stollar BD, Papalian M. Secondary structure in denatured DNA is responsible for its reaction with antinative DNA antibodies of systemic lupus erythematosus sera. J Clin Invest. 1980;66(2):210–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dorner T, Giesecke C, Lipsky PE. Mechanisms of B cell autoimmunity in SLE. Arthritis research & therapy. 2011;13(5):243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Radic MZ, Weigert M. Genetic and structural evidence for antigen selection of anti-DNA antibodies. Annu Rev Immunol. 1994;12:487–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Papalian M, Lafer E, Wong R, Stollar BD. Reaction of systemic lupus erythematosus antinative DNA antibodies with native DNA fragments from 20 to 1,200 base pairs. J Clin Invest. 1980;65(2):469–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ali R, Dersimonian H, Stollar BD. Binding of monoclonal anti-native DNA autoantibodies to DNA of varying size and conformation. Mol Immunol. 1985;22(12):1415–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pisetsky DS, Reich CF. The influence of DNA size on the binding of anti-DNA antibodies in the solid and fluid phase. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1994;72(3):350–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kaufman EN, Jain RK. Effect of bivalent interaction upon apparent antibody affinity: experimental confirmation of theory using fluorescence photobleaching and implications for antibody binding assays. Cancer Res. 1992;52(15):4157–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Romans DG, Tilley CA, Dorrington KJ. Monogamous bivalency of IgG antibodies. I. Deficiency of branched ABHI-active oligosaccharide chains on red cells of infants causes the weak antiglobulin reactions in hemolytic disease of the newborn due to ABO incompatibility. J Immunol. 1980;124(6):2807–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stearns NA, Pisetsky DS. The role of monogamous bivalency and Fc interactions in the binding of anti-DNA antibodies to DNA antigen. Clin Immunol. 2016;166–167:38–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Karounos DG, Pisetsky DS. Specificity analysis of monoclonal anti-DNA antibodies. Immunology. 1987;60(4):497–501. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sano H, Takai O, Harata N, Yoshinaga K, Kodama-Kamada I, Sasaki T. Binding properties of human anti-DNA antibodies to cloned human DNA fragments. Scand J Immunol. 1989;30(1):51–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wu DP, Gilkeson GS, Armitage J, Reich CF, Pisetsky DS. Selective recognition of DNA antigenic determinants by murine monoclonal anti-DNA antibodies. Clin Exp Immunol. 1990;82(1):33–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Uccellini MB, Busto P, Debatis M, Marshak-Rothstein A, Viglianti GA. Selective binding of anti-DNA antibodies to native dsDNA fragments of differing sequence. Immunol Lett. 2012;143(1):85–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bunyard MP, Pisetsky DS. Characterization of antibodies to bacterial double-stranded DNA in the sera of normal human subjects. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 1994;105(2):122–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fredriksen K, Skogsholm A, Flaegstad T, Traavik T, Rekvig OP. Antibodies to dsDNA are produced during primary BK virus infection in man, indicating that anti-dsDNA antibodies may be related to virus replication in vivo. Scand J Immunol. 1993;38(4):401–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Karounos DG, Grudier JP, Pisetsky DS. Spontaneous expression of antibodies to DNA of various species origin in sera of normal subjects and patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Immunol. 1988;140(2):451–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Robertson CR, Gilkeson GS, Ward MM, Pisetsky DS. Patterns of heavy and light chain utilization in the antibody response to single-stranded bacterial DNA in normal human subjects and patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1992;62(1 Pt 1):25–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Robertson CR, Pisetsky DS. Specificity analysis of antibodies to single-stranded micrococcal DNA in the sera of normal human subjects and patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 1992;10(6):589–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gilkeson GS, Pippen AM, Pisetsky DS. Induction of cross-reactive anti-dsDNA antibodies in preautoimmune NZB/NZW mice by immunization with bacterial DNA. J Clin Invest. 1995;95(3):1398–402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fredriksen K, Osei A, Sundsfjord A, Traavik T, Rekvig OP. On the biological origin of anti-double-stranded (ds) DNA antibodies: systemic lupus erythematosus-related anti-dsDNA antibodies are induced by polyomavirus BK in lupus-prone (NZBxNZW) F1 hybrids, but not in normal mice. Eur J Immunol. 1994;24(1):66–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Arbuckle MR, Reichlin M, Harley JB, James JA. Shared early autoantibody recognition events in the development of anti-Sm B/B’ in human lupus. Scand J Immunol. 1999;50(5):447–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.James JA, Gross T, Scofield RH, Harley JB. Immunoglobulin epitope spreading and autoimmune disease after peptide immunization: Sm B/B’-derived PPPGMRPP and PPPGIRGP induce spliceosome autoimmunity. J Exp Med. 1995;181(2):453–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.James JA, Harley JB. Linear epitope mapping of an Sm B/B’ polypeptide. J Immunol. 1992;148(7):2074–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Scofield RH, Farris AD, Horsfall AC, Harley JB. Fine specificity of the autoimmune response to the Ro/SSA and La/SSB ribonucleoproteins. Arthritis Rheum. 1999;42(2):199–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Scofield RH, Zhang FC, Kurien BT, Harley JB. Anti-Ro fine specificity defined by multiple antigenic peptides identifies components of tertiary epitopes. Clin Exp Immunol. 1997;109(3):480–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McClain MT, Heinlen LD, Dennis GJ, Roebuck J, Harley JB, James JA. Early events in lupus humoral autoimmunity suggest initiation through molecular mimicry. Nat Med. 2005;11(1):85–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.St Clair EW, Kenan D, Burch JA Jr., Keene JD, Pisetsky DS. The fine specificity of anti-La antibodies induced in mice by immunization with recombinant human La autoantigen. J Immunol. 1990;144(10):3868–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Greidinger EL, Gazitt T, Jaimes KF, Hoffman RW. Human T cell clones specific for heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A2 autoantigen from connective tissue disease patients assist in autoantibody production. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50(7):2216–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mohan C, Adams S, Stanik V, Datta SK. Nucleosome: a major immunogen for pathogenic autoantibody-inducing T cells of lupus. J Exp Med. 1993;177(5):1367–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Szymula A, Rosenthal J, Szczerba BM, Bagavant H, Fu SM, Deshmukh US. T cell epitope mimicry between Sjogren’s syndrome Antigen A (SSA)/Ro60 and oral, gut, skin and vaginal bacteria. Clin Immunol. 2014;152(1–2):1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Talken BL, Holyst MM, Lee DR, Hoffman RW. T cell receptor beta-chain third complementarity-determining region gene usage is highly restricted among Sm-B autoantigen-specific human T cell clones derived from patients with connective tissue disease. Arthritis Rheum. 1999;42(4):703–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Choi JY, Ho JH, Pasoto SG, Bunin V, Kim ST, Carrasco S, et al. Circulating follicular helper-like T cells in systemic lupus erythematosus: association with disease activity. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015;67(4):988–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kim SJ, Lee K, Diamond B. Follicular Helper T Cells in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Frontiers in immunology. 2018;9:1793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dieudonne Y, Gies V, Guffroy A, Keime C, Bird AK, Liesveld J, et al. Transitional B cells in quiescent SLE: An early checkpoint imprinted by IFN. J Autoimmun. 2019;102:150–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jacobi AM, Zhang J, Mackay M, Aranow C, Diamond B. Phenotypic characterization of autoreactive B cells--checkpoints of B cell tolerance in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. PloS one. 2009;4(6):e5776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Suurmond J, Atisha-Fregoso Y, Marasco E, Barlev AN, Ahmed N, Calderon SA, et al. Loss of an IgG plasma cell checkpoint in patients with lupus. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2019;143(4):1586–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tipton CM, Fucile CF, Darce J, Chida A, Ichikawa T, Gregoretti I, et al. Diversity, cellular origin and autoreactivity of antibody-secreting cell population expansions in acute systemic lupus erythematosus. Nature immunology. 2015;16(7):755–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yurasov S, Tiller T, Tsuiji M, Velinzon K, Pascual V, Wardemann H, et al. Persistent expression of autoantibodies in SLE patients in remission. J Exp Med. 2006;203(10):2255–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yurasov S, Wardemann H, Hammersen J, Tsuiji M, Meffre E, Pascual V, et al. Defective B cell tolerance checkpoints in systemic lupus erythematosus. J Exp Med. 2005;201(5):703–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jiang P, Lo YMD. The Long and Short of Circulating Cell-Free DNA and the Ins and Outs of Molecular Diagnostics. Trends Genet. 2016;32(6):360–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Elkon KB. Review: Cell Death, Nucleic Acids, and Immunity: Inflammation Beyond the Grave. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2018;70(6):805–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mistry P, Kaplan MJ. Cell death in the pathogenesis of systemic lupus erythematosus and lupus nephritis. Clin Immunol. 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Apel F, Zychlinsky A, Kenny EF. The role of neutrophil extracellular traps in rheumatic diseases. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2018;14(8):467–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gupta S, Kaplan MJ. The role of neutrophils and NETosis in autoimmune and renal diseases. Nature reviews Nephrology. 2016;12(7):402–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chan RW, Jiang P, Peng X, Tam LS, Liao GJ, Li EK, et al. Plasma DNA aberrations in systemic lupus erythematosus revealed by genomic and methylomic sequencing. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111(49):E5302–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Soni C, Reizis B. DNA as a self-antigen: nature and regulation. Curr Opin Immunol. 2018;55:31–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mobarrez F, Svenungsson E, Pisetsky DS. Microparticles as autoantigens in systemic lupus erythematosus. Eur J Clin Invest. 2018;48(12):e13010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ullal AJ, Reich CF 3rd, Clowse M, Criscione-Schreiber LG, Tochacek M, Monestier M, et al. Microparticles as antigenic targets of antibodies to DNA and nucleosomes in systemic lupus erythematosus. J Autoimmun. 2011;36:173–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Nielsen CT, Ostergaard O, Stener L, Iversen LV, Truedsson L, Gullstrand B, et al. Increased IgG on cell-derived plasma microparticles in systemic lupus erythematosus is associated with autoantibodies and complement activation. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64:1227–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Fortin PR, Cloutier N, Bissonnette V, Aghdassi E, Eder L, Simonyan D, et al. Distinct subtypes of microparticle-containing immune complexes are associated with disease activity, damage, and carotid intima-media thickness in systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol. 2016;43:2019–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Mobarrez F, Vikerfors A, Gustafsson JT, Gunnarsson I, Zickert A, Larsson A, et al. Microparticles in the blood of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE): phenotypic characterization and clinical associations. Scientific reports. 2016;6:36025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lopez P, Rodriguez-Carrio J, Martinez-Zapico A, Caminal-Montero L, Suarez A. Circulating microparticle subpopulations in systemic lupus erythematosus are affected by disease activity. Int J Cardiol. 2017;236:138–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ullal AJ, Marion TN, Pisetsky DS. The role of antigen specificity in the binding of murine monoclonal anti-DNA antibodies to microparticles from apoptotic cells. Clin Immunol. 2014;154(2):178–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Satoh M, Chan EK, Ho LA, Rose KM, Parks CG, Cohn RD, et al. Prevalence and sociodemographic correlates of antinuclear antibodies in the United States. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64(7):2319–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bhattacharya J, Pappas K, Toz B, Aranow C, Mackay M, Gregersen PK, et al. Serologic features of cohorts with variable genetic risk for systemic lupus erythematosus. Mol Med. 2018;24(1):24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Olsen NJ, Li QZ, Quan J, Wang L, Mutwally A, Karp DR. Autoantibody profiling to follow evolution of lupus syndromes. Arthritis research & therapy. 2012;14(4):R174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Olsen NJ, Karp DR. Autoantibodies and SLE: the threshold for disease. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2014;10(3):181–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Arbuckle MR, McClain MT, Rubertone MV, Scofield RH, Dennis GJ, James JA, et al. Development of autoantibodies before the clinical onset of systemic lupus erythematosus. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(16):1526–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Pisetsky DS, Rovin BH, Lipsky PE. New Perspectives in Rheumatology: biomarkers as entry criteria for clinical trials of new therapies for systemic lupus erythematosus: the example of antinuclear antibodies and anti-DNA. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017;69:487–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wallace DJ, Stohl W, Furie RA, Lisse JR, McKay JD, Merrill JT, et al. A phase II, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-ranging study of belimumab in patients with active systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;61(9):1168–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Furie R, Petri M, Zamani O, Cervera R, Wallace DJ, Tegzova D, et al. A phase III, randomized, placebo-controlled study of belimumab, a monoclonal antibody that inhibits B lymphocyte stimulator, in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63:3918–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Choi MY, Clarke AE, St Pierre Y, Hanly JG, Urowitz MB, Romero-Diaz J, et al. Antinuclear antibody-negative systemic lupus erythematosus in an international inception cohort. Arthritis Care Res. 2019;71:893–902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]