Abstract

Objectives:

Persons living with Alzheimer’s disease (AD) may be at increased risk for prescribing cascades due to greater multimorbidity, polypharmacy, and the need for more complex care. Our objective was to assess the proportion of the antidopaminergic-antiparkinsonian medication prescribing cascades among persons living with Alzheimer’s disease.

Setting:

Two large administrative claims databases in the United States.

Participants:

We identified patients aged ≥50 on January 1, 2017, who were dispensed a drug used to treat Alzheimer’s disease for at least one day in the 365 days prior to or on cohort entry date and who had medical and pharmacy coverage in the 365 days prior to the cohort entry date. We excluded individuals with a recent institutional stay. We identified incident antidopaminergic (antipsychotic/metoclopramide) use in the 183 days following cohort entry and identified subsequent incident antiparkinsonian drug use within 8–365 days.

Results:

There were 121,538 patients with Alzheimer’s disease eligible for inclusion. Approximately 62% were women with a mean age of 79.5 (SD ± 8.6). The mean number of drugs dispensed was 9.2 (SD ± 4.9). There were 36 incident antiparkinsonian users among 4,534 incident antipsychotic/metoclopramide users (0.8%).

Conclusion:

We determined that the proportion of antidopaminergic-antiparkinsonian medication prescribing cascades, widely considered as high-priority, was low. Our approach can be used to assess the proportion of prescribing cascades in populations considered to be at high risk and to prioritize system-level interventional efforts to improve medication safety in these patients.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease and related Dementias, medication safety, older adults, prescribing cascades

INTRODUCTION

Prescribing cascades occur when a healthcare provider misinterprets the side effect of a drug as a new medical condition and prescribes a second, potentially unnecessary drug therapy to address this drug-related harm.1,2 The second drug in turn can lead to additional adverse effects. Prescribing cascades can lead to an increase in the overall burden of multimorbidity, with adverse effects on health-related quality of life and function.3 Prescribing cascades have become an important target relevant to improving medication safety, reducing problematic polypharmacy, and as a focus for deprescribing efforts in high-risk populations.4

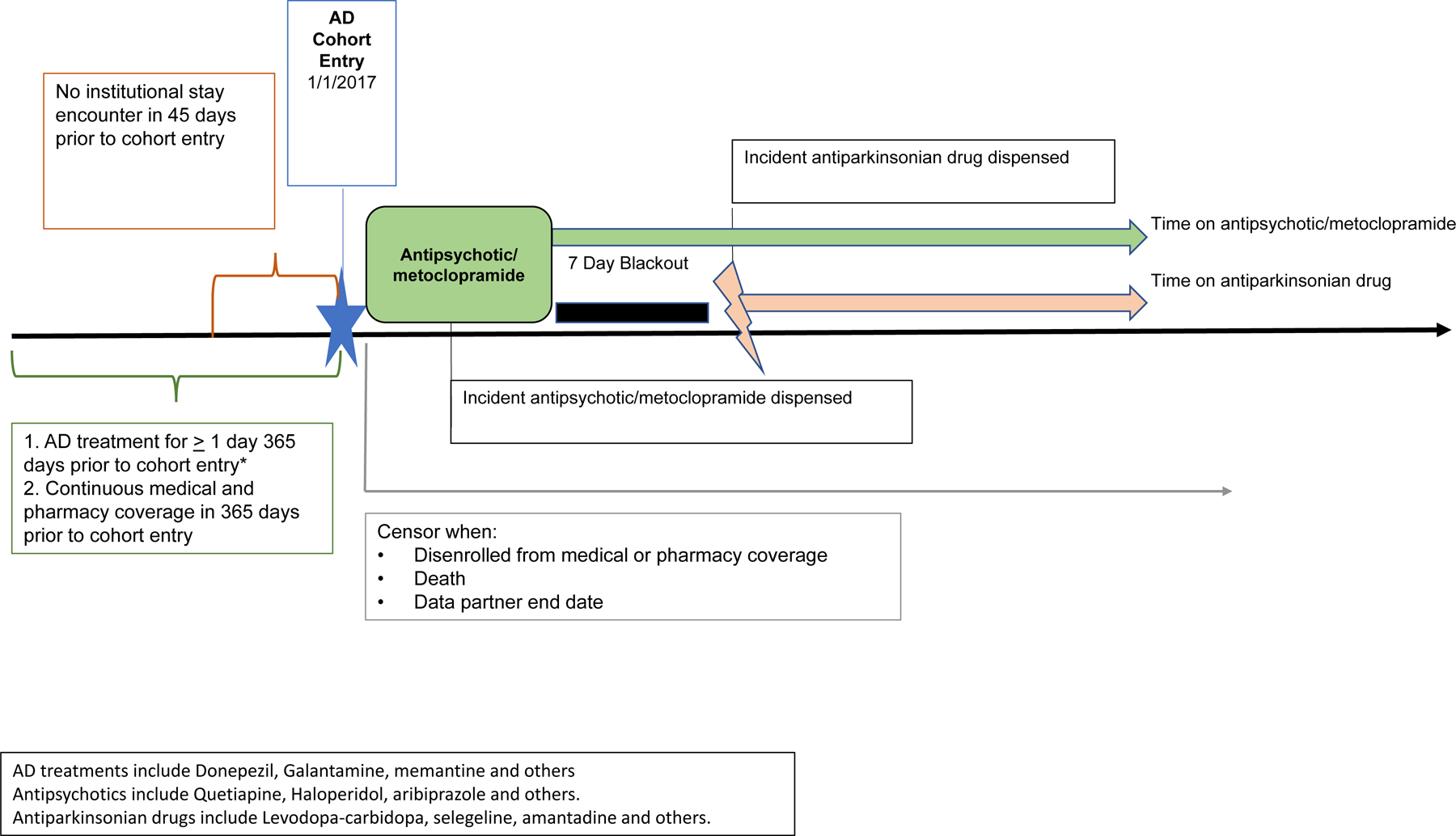

There are several studies of prescribing cascades.5–11 One prescribing cascade often considered to be high priority includes the development of drug-induced parkinsonism and subsequent use of dopamine agonists (e.g., levodopa) after the use of antidopaminergic drugs including antipsychotics,8 and metoclopramide (Figure 1).9–11 Drug-induced parkinsonism is the most common cause of parkinsonism after idiopathic Parkinson’s disease.13 Drug-induced parkinsonism has been noted to occur with both typical (e.g., haloperidol and phenothiazines) and atypical antipsychotic drugs (e.g., olanzapine, quetiapine risperidone),13 with the latter carrying a lower potential for this adverse effect;14 although high dose atypical antipsychotics and typical antipsychotics may carry similar risks of development of parkinsonism.15 Persons with AD are increasingly prescribed antipsychotics to manage the behavioral symptoms of dementia.16 Older adults also may have compromised kidney function which may lead to metoclopramide accumulation and increase risk for parkinsonism. Additionally, metoclopramide is often used to treat symptoms of nausea and vomiting. However, there are no previous studies that have measured the proportion of prescribing cascades in persons living with AD. To address this gap, we estimated the proportion of the antipsychotic/metoclopramide-antiparkinsonian prescribing cascades among persons living with AD in two large U.S. health plans.

Figure 1. Incident antipsychotic/metoclopramide use with incident antiparkinsonian use prescribing cascade.

AD days’ supply and dispensings assessed from 6/1/2015 forward. AD days’ supply and dispensings assessed from 06/01/2015 forward. AD = Alzheimer’s Disease

METHODS

Data source.

We conducted this study using administrative claims data from two large commercial U.S. health plans which included a Medicare Advantage membership. Further details of the database are shown in Supplementary File 1.

Alzheimer’s Disease cohort

Using January 1, 2017, as the cohort entry, we identified patients aged 50 years and older who had been treated for at least one day with a drug used to treat AD (i.e., donepezil, galantamine, rivastigmine, memantine, memantine/donepezil) via outpatient pharmacy dispensing data in the 365 days prior to or on that date. Eligible patients were enrolled in medical and pharmacy coverage for 365 days prior to cohort entry date, with an allowable enrollment gap of up to 45 days. We excluded patients with an institutional stay encounter (e.g., skilled nursing facility) in the 45 days prior to or on cohort entry, and censored patients based on the first of the following: disenrollment from medical or pharmacy coverage, death, or end of data.

Cohort 1. Incident antipsychotic/metoclopramide use with incident antiparkinsonian use prescribing cascade (Figure 1).

We identified patients with incident dispensing of an antipsychotic/metoclopramide on the day of cohort entry or during the 183 days after cohort entry (i.e., first six months of 2017), with a 183-day no use period before antipsychotic/metoclopramide. The first antipsychotic/metoclopramide episode to meet the criteria was counted per eligible patient. The drugs evaluated are shown in the Supplementary Table 1. Incident antiparkinsonian use was defined as an incident dispensing of an antiparkinsonian drug from day 8 through 365 following antipsychotic/metoclopramide start, during the antipsychotic/metoclopramide treatment episode, with a 183-day no-use period to define incident antiparkinsonian drug use. This no use period is the number of days a user is required to have no evidence of prior drug dispensing and continuous drug and medical coverage prior to an incident treatment episode. We also excluded those who had an incident antiparkinsonian dispensing during days 0 to 7 from the antipsychotic/metoclopramide dispensing because dispensing of an antiparkinsonian medication during this early period is unlikely to be attributed to the antipsychotic/metoclopramide use. In the absence of reliable data on the time frame for development of antipsychotic/metoclopramide induced parkinsonism, we made reasonable approximations about this period to be about 7 days. We counted the first incident antiparkinsonian episode per patient that met all criteria. We censored patients based on the first occurrence of the following: disenrollment from medical or pharmacy coverage, death, or end of data, or end of first antiparkinsonian episode.

Cohort 2. Prescribing cascades among those with polypharmacy in Alzheimer’s Disease cohort (Supplementary Figure 1).

We also determined the incidence of the antipsychotic/metoclopramide-antiparkinsonian prescribing cascade among those with polypharmacy in the AD cohort. The polypharmacy cohort included those who were concomitantly using 4 other drugs on that antipsychotic/metoclopramide start date, for at least 1 day,17 of incident antipsychotic/metoclopramide use within 183 days of cohort entry date (January through June 2017). A combination drug was considered a single generic. We identified incident antipsychotic/metoclopramide use as incident dispensing of antipsychotic/metoclopramide on the day of cohort entry or during the 183 days after cohort entry. We included someone in the cohort if they were concomitantly using 4 other drugs on that antipsychotic/metoclopramide start date, for at least 1 day. We included the first incident antipsychotic/metoclopramide dispensing per patient that met all criteria. Among this cohort we identified those with an incident dispensing (183-day washout) of an antiparkinsonian drug on day 8 through day 365 of antipsychotic/metoclopramide start (i.e., 7-day blackout period). The same censoring criteria as above were applied.

Ethical approval.

The study was reviewed and approved by the institutional review board at the University of Massachusetts Medical School.

RESULTS

Characteristics of the population.

There were 121,538 patients with AD eligible for inclusion in the main cohort. Approximately 62% were female, with a mean age of 79.5 (SD ± 8.6). Their combined comorbidity score, a measure of comorbidity, was 3 (SD ± 2.7).18 The mean number of different generic drugs dispensed in the 183 days prior to cohort entry was 9.2 (SD 4.9). These are shown in Table 1. The proportion of various antipsychotic drugs used is shown in Supplementary Table 2.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics of Alzheimer’s Disease cohort (Total n=121,538).

| Variables | Participants n (%) |

|---|---|

| Sex, Female | (62.2) |

| Age, Mean (SD) | 79.5 (8.6) |

| Age Range | |

| 50–54 | 960 (0.8) |

| 55–59 | 2085 (1.7) |

| 60–64 | 4143 (3.4) |

| 65–69 | 7759 (6.4) |

| 70–74 | 16430 (13.5) |

| 75–79 | 25065 (20.6) |

| 80–84 | 28271 (23.3) |

| 85+ | 36825 (30.3) |

| Health Care Utilization Mean (SD) # | |

| Number of Unique Drug Classes | 8.8 (4.5) |

| Number of Generics | 9.2 (4.9) |

| Number of Filled Prescriptions | 26.7 (20.9) |

| Number of Ambulatory visits | 9.3 (9.5) |

| Number of Emergency Department Visits | 0.4 (.8) |

| Number of Non-acute institutional encounters | 0.5 (1.5) |

| Number of Other Ambulatory encounters | 4 (9.3) |

These mean values apply from 6 months prior to cohort entry date

Prescribing cascades.

The results for the prescribing cascade are shown in Table 2. Among 121,538 patients with AD from two large U.S. health plans, there were 36 incident antiparkinsonian drugs users among 4,534 incident antipsychotic/metoclopramide users (0.8%). In the cohort of AD patients with polypharmacy, we identified 3,485 patients with polypharmacy at the day of incident antipsychotic/metoclopramide dispensing, 20 of whom subsequently used an antiparkinsonian drug (0.5%). The data on disenrollment are shown in Supplementary Table 3.

Table 2.

Results for the incidence of prescribing cascades among participants with Alzheimer’s Disease (AD).

| Prescribing Cascade Cohort | Antipsychotic/metoclopramide, N | Antiparkinsonian use, n | Person-time on Antiparkinsonian, Total, days | Time on Antiparkinsonian Drug, Mean (SD), days |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Incident antipsychotic/metoclopramide use with incident antiparkinsonian use | 4534 | 36 | 5869 | 163.0 (150.1) |

| Polypharmacy Prescribing cascades among those with polypharmacy in AD cohort |

3485 | 20 | 3977 | 179.9(153.7) |

DISCUSSION

We estimated that the proportion of the antidopaminergic-antiparkinsonian prescribing cascades among persons living with AD in two large administrative claims databases in the US was low, and was similar for all the cohorts we examined in our study.

Our findings bear both similarities and differences with other population-based studies. A case-control study among Medicaid enrollees above 65 years or older in New Jersey reported a threefold risk of initiation of new prescriptions for levodopa after initiation of metoclopramide10 (adjusted OR, 3.09; 95 % CI, 2.25–4.26). Another case-control study among older adults above 65 years of age in the same database evaluated the use of antipsychotics in the 90 days prior to the initiation of an antiparkinsonian therapy, and reported that antipsychotics users were 5.4 times more likely to begin antiparkinsonian therapy than non-users (95% CI 4.8–6.1)..19 Although anticholinergic drugs accounted for the highest number of cases of antiparkinsonian therapy, there was a more than twofold increased risk of initiating therapy for dopaminergic drugs specific for idiopathic Parkinson’s disease (OR, 2.2; 95% CI 1.9–2.7). Another study reported similar rates of parkinsonism among those who were dispensed high dose atypical antipsychotics compared to those dispensed typical antipsychotics.15 However one needs to carefully consider the potential improvement in prescribing practices over time when comparing findings from our study to earlier studies when the concern about antipsychotics and side effects like parkinsonism was not well recognized.

Another study from Taiwan which included 218,931 metoclopramide users (57.9% female, median age of 41 years and 83.39% were <60 years of age) reported a similar low prevalence of drug-induced parkinsonism associated with metoclopramide (0.06%) over a one-year period.11 However it also reported that risk was twofold higher compared to non-users (aHR 2.16; 95% CI 1.54 –3.02). Those in the high exposure group (>30 mg/day and/or duration >5 days) had a 1.83 fold higher risk than standard users (≤ 30 mg/day and/or duration ≤ 5 days). In another study from Korea, metoclopramide and levosulpiride users above 65 years of age had almost three-fold odds of beginning levodopa therapy relative to non-users (metoclopramide: OR, 2.94; 95% CI 2.35–3.67 and levosulpiride: OR, 3.30; 95% CI, 3.52–4.32). 9 Compared to those who received a shorter duration of the drug (<20 days), the risk of initiation of levodopa therapy for both metoclopramide and levosulpride users increased with increasing duration of therapy beyond 20 days. Another case-control study from Korea also reported a higher risk of parkinsonism with exposure to propulsive drugs (OR, 2.82; 95% CI 2.46–3.21), antipsychotics (OR, 3.0; 95% CI 1.67–5.43), and flunarizine (OR, 4.95; 95% CI 2.71–9.04) in the year before the first date of diagnosis of parkinsonism,8 compared with never users. The ORs were higher with those more recently exposed and those exposed to higher cumulative doses.

In contrast to the above studies, we did not evaluate the risk of anti-parkinsonian drug use with comparators. Despite the low proportion of drug-induced parkinsonism noted in our study the morbidity and mortality from drug-induced parkinsonism should not be underestimated because the incidence of drug-induced parkinsonism has been noted to be rising.20

Strength and Limitations.

Our study has some limitations. In the absence of a gold standard for identifying persons living with AD in administrative claims database, we used prescription drug use as a proxy for the diagnosis which may underestimate the number of patients with AD. We reviewed the strengths and limitations of alternative approaches such as the use of administrative codes alone and or combined with medication use, both of which are also susceptible to misclassification. 21 The use of medications for ADRD serve as a reasonable proxy for the spectrum of ADRD patients who were at risk of prescribing cascades. As a result, these patients should be considered as potentially having dementia. Potential misclassification of exposure is also possible. However, this source is expected to be highly complete for such medications that are billed to insurance. These also represent dispensings which indicate a patient picked up the prescription, versus prescription data which can only infer that the patient received the medication.

We did not include a control group of participants without ADRD because our objective was to generate data on proportion of participants in support of the feasibility of a pragmatic trial. This limited our ability to make inferences about the relative risk of prescribing cascades. We did not evaluate the dose and duration of the include drugs which also limit our ability to interpret these findings. Given the small number of cascades identified a subgroup analysis was unlikely to yield meaningful results. We did not have information on the characteristics of excluded participants which may affect the generalizability of our findings.

Administrative data may lack sufficient clinical information to determine instances in which prescribing cascades may be therapeutically appropriate.2 This highlights the importance of our key finding that the true proportion of this prescribing cascade is likely even lower. Another limitation is that we did not use a negative control or measure the proportion of prescribing cascades in the non-polypharmacy cohort. Despite these limitations, our study provides a robust analytic approach to the measurement of prescribing cascades in large administrative databases.

Future research.

Future studies using validated algorithms for identifying AD may provide better estimates of the burden of this prescribing cascade in this population. In the absence of reliable data on the time frame for development of antipsychotic/metoclopramide induced parkinsonism, we made approximations about the blackout period. Subsequent studies could consider alternative time-windows for the blackout period and include studies with negative controls.

Conclusion

We determined that the proportion of antidopaminergic-antiparkinsonian medication prescribing cascades, widely considered as high-priority, was low in patients with ADRD.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary File 1. Data Source Details

Supplementary Table 1. Names of drugs used to identify Alzheimer’s disease participants and antidopaminergic-antiparkinsonian prescribing cascade

Supplementary Table 2. List of Antipsychotics/Metoclopramide evaluated in the study

Supplementary Table 3. Disenrollment of Alzheimer’s disease participants.

Supplementary Figure 1. Prescribing cascades among those with polypharmacy in Alzheimer’s Disease cohort

Key Points:

There are few studies which measure the proportion of prescribing cascades among persons with Alzheimer’s dementia.

This study shows that the proportion of antidopaminergic-antiparkinsonian prescribing cascades among persons with Alzheimer’s dementia was low in two large administrative databases in the United States

Why does this paper matter?

This study shows that the proportion of antidopaminergic-antiparkinsonian prescribing cascades among persons with Alzheimer’s dementia in two large administrative databases in the United States was low.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The Controlling and Stopping Cascades Leading to Adverse Drug Effects Study in Alzheimer’s Disease (CASCADES-AD) study was supported by a grant from the National Institute on Aging (1R56AG061813-01- PI Gurwitz).

Role of the sponsor.

This sponsor was not involved in the study design; the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of this report; and in the decision to submit the report for publication. This work has not been presented elsewhere.

Funding information:

This work was sponsored by the National Institute on Aging (1R56AG061813-01) and has not been presented elsewhere.

Abbreviations:

- AD

Alzheimer’s Disease

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Contributor Information

Sonal Singh, University of Massachusetts Medical School & Meyers Primary Care Institute, Worcester, MA, USA.

Noelle M. Cocoros, Department of Population Medicine, Harvard Medical School / Harvard Pilgrim Health Care Institute, Boston, MA, USA.

Kevin Haynes, HealthCore, Inc. Wilmington, Delaware, USA.

Vinit P. Nair, Humana Healthcare Research Inc. (Humana), Louisville, Kentucky, USA.

Thomas P. Harkins, Humana Healthcare Research, Inc. (Humana) Miami, FL, USA.

Paula A Rochon, Women’s College Research Institute, Women’s College Hospital, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

Richard Platt, Department of Population Medicine, Harvard Medical School / Harvard Pilgrim Health Care Institute, Boston, MA, USA.

Inna Dashevsky, Department of Population Medicine, Harvard Medical School / Harvard Pilgrim Health Care Institute, Boston, MA, USA.

Juliane Reynolds, Department of Population Medicine, Harvard Medical School / Harvard Pilgrim Health Care Institute, Boston, MA, USA.

Kathleen M Mazor, University of Massachusetts Medical School & Meyers Primary Care Institute, Worcester, MA, USA.

Sarah Bloomstone, University of Massachusetts Medical School & Meyers Primary Care Institute, Worcester, MA, USA.

Kathryn Anzuoni, University of Massachusetts Medical School & Meyers Primary Care Institute, Worcester, MA, USA.

Sybil L. Crawford, University of Massachusetts Medical School & Meyers Primary Care Institute, Worcester, MA, USA.

Jerry H. Gurwitz, University of Massachusetts Medical School & Meyers Primary Care Institute, Worcester, MA, USA.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rochon PA, Gurwitz JH. Optimising drug treatment for elderly people: the prescribing cascade. BMJ 1997;315(7115):1096–9. 10.1136/bmj.315.7115.1096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McCarthy LM, Visentin JD, Rochon PA. Assessing the Scope and Appropriateness of Prescribing Cascades. J Am Geriatr Soc 2019;67(5):1023–26. 10.1111/jgs.15800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson TS, Steinman MA. Antihypertensive Prescribing Cascades as High-Priority Targets for Deprescribing. JAMA Intern Med. 2020. May 1;180(5):651–652. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.7082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McKean M, Pillans P, Scott IA. A medication review and deprescribing method for hospitalised older patients receiving multiple medications. Intern Med J 2016;46(1):35–42. 10.1111/imj.12906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vouri SM, van Tuyl JS, Olsen MA, Xian H, Schootman M. An evaluation of a potential calcium channel blocker-lower-extremity edema-loop diuretic prescribing cascade. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2018. Sep-Oct;58(5):534–539.e4. 10.1016/j.japh.2018.06.014. Epub 2018 Jul 20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Savage RD, Visentin JD, Bronskill SE, Wang X, Gruneir A, Giannakeas V, Guan J, Lam K, Luke MJ, Read SH, Stall NM, Wu W, Zhu L, Rochon PA, McCarthy LM. Evaluation of a Common Prescribing Cascade of Calcium Channel Blockers and Diuretics in Older Adults With Hypertension. JAMA Intern Med. 2020. May 1;180(5):643–651. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.7087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gill SS, Mamdani M, Naglie G, et al. A prescribing cascade involving cholinesterase inhibitors and anticholinergic drugs. Arch Intern Med 2005;165(7):808–13. 10.1001/archinte.165.7.808 [published 6. Kim S, Cheon SM, Suh HS. Association Between Drug Exposure and Occurrence of Parkinsonism in Korea: A Population-Based Case-Control Study. Ann Pharmacother 2019;53(11):1102–10. doi: 10.1177/1060028019859543 [published Online First: 2019/06/21] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim S, Cheon SM, Suh HS. Association Between Drug Exposure and Occurrence of Parkinsonism in Korea: A Population-Based Case-Control Study. Ann Pharmacother. 2019. November;53(11):1102–1110. 10.1177/1060028019859543. Epub 2019 Jun 19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huh Y, Kim DH, Choi M, et al. Metoclopramide and Levosulpiride Use and Subsequent Levodopa Prescription in the Korean Elderly: The Prescribing Cascade. Journal of clinical medicine 2019;8(9) 10.3390/jcm8091496 [published Online First: 2019/09/25] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Avorn J, Gurwitz JH, Bohn RL, et al. Increased incidence of levodopa therapy following metoclopramide use. Jama 1995;274(22):1780–2. [published Online First: 1995/12/13] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tsai SC, Sheu SY, Chien LN, et al. High exposure compared with standard exposure to metoclopramide associated with a higher risk of parkinsonism: a nationwide population-based cohort study. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2018;84(9):2000–09. 10.1111/bcp.13630 [published Online First: 2018/05/11] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thanvi B, Treadwell S. Drug induced parkinsonism: a common cause of parkinsonism in older people. Postgraduate Medical Journal 2009;85(1004):322–26. 10.1136/pgmj.2008.073312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Germay S, Montastruc F, Carvajal A, et al. Drug-induced parkinsonism: Revisiting the epidemiology using the WHO pharmacovigilance database. Parkinsonism & related disorders 2020;70:55–59. 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2019.12.011 [published Online First: 2019/12/23] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vasilyeva I, Biscontri RG, Enns MW, et al. Movement disorders in elderly users of risperidone and first generation antipsychotic agents: a Canadian population-based study. PLoS One 2013;8(5):e64217. 10.1371/journal.pone.0064217 [published Online First: 2013/05/23] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rochon PA, Stukel TA, Sykora K, et al. Atypical antipsychotics and parkinsonism. Arch Intern Med 2005;165(16):1882–8. 10.1001/archinte.165.16.1882 [published Online First: 2005/09/15] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gill SS, Bronskill SE, Normand SL, et al. Antipsychotic drug use and mortality in older adults with dementia. Ann Intern Med 2007;146(11):775–86. 10.7326/0003-4819-146-11-200706050-00006 [published Online First: 2007/06/06] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Masnoon N, Shakib S, Kalisch-Ellett L, et al. What is polypharmacy? A systematic review of definitions. BMC Geriatr 2017;17(1):230. 10.1186/s12877-017-0621-2 [published Online First: 2017/10/12] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gagne JJ, Glynn RJ, Avorn J, et al. A combined comorbidity score predicted mortality in elderly patients better than existing scores. J Clin Epidemiol 2011;64(7):749–59. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.10.004 [published Online First: 2011/01/07] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Avorn J, Bohn RL, Mogun H, et al. Neuroleptic drug exposure and treatment of parkinsonism in the elderly: a case-control study. Am J Med 1995;99(1):48–54. 10.1016/s0002-9343(99)80104-1 [published Online First: 1995/07/01] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Han S, Kim S, Kim H, et al. Prevalence and incidence of Parkinson’s disease and drug-induced parkinsonism in Korea. BMC public health 2019;19(1):1328. 10.1186/s12889-019-7664-6 [published Online First: 2019/10/24] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wilkinson T, Ly A, Schnier C, et al. Identifying dementia cases with routinely collected health data: A systematic review. Alzheimer’s & Dementia 2018;14(8):1038–51. 10.1016/j.jalz.2018.02.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary File 1. Data Source Details

Supplementary Table 1. Names of drugs used to identify Alzheimer’s disease participants and antidopaminergic-antiparkinsonian prescribing cascade

Supplementary Table 2. List of Antipsychotics/Metoclopramide evaluated in the study

Supplementary Table 3. Disenrollment of Alzheimer’s disease participants.

Supplementary Figure 1. Prescribing cascades among those with polypharmacy in Alzheimer’s Disease cohort