Abstract

Chemosterilization is reported in cattle fed chlortetracycline hydrochloride (CTC) at dosages ranging from 1.1 mg/kg for 120 days to 11 mg/kg for 30–60 days. The relationship between plasma CTC drug concentration and carrier clearance has not been described. Chronic carrier status was established in 21 steers with a Virginia isolate of Anaplasma marginale and confirmed by cELISA and an A. marginale-specific RT-PCR. Four negative, splenectomized steers served as active disease transmission sentinels. Steers were randomized to receive 4.4 mg/kg/day (LD); 11 mg/kg/day (MD); or 22 mg/kg/day (HD) of oral chlortetracycline; or placebo (CONTROL) for 80 days. The LD, MD and HD treatment groups consisted of 5 infected steers and 1 splenectomized steer; CONTROL group had six infected steers and 1 splenectomized steer. The daily treatments and ration were divided equally and fed twice daily. Blood samples were collected semi-weekly for determining plasma drug concentration by ultrahigh performance liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry/mass spectrometry method and assessment of disease status by both cELISA and RT-PCR. Mean (CV%) chlortetracycline plasma drug concentrations in the LD, MD, and HD groups were 85.3 (28%), 214.5 (32%) and 518.9 (40%) ng/mL during days 4 through 53 of treatment. A negative RT-PCR assay result was confirmed in all CTC-treated groups within 49 days of treatment; however, cELISA required an additional 49 to 88 days before similar results. Subinoculation of splenectomized steers confirmed chemosterilization. These results are important for influencing future chemosterilization strategies and impacting free trade policy among countries and regions of contrasting endemicity.

Keywords: Anaplasma, Cattle, Chemosterilization, Chlortetracycline, Competitive ELISA, Polymerase chain reaction

1. Introduction

Cattle infected with anaplasmosis following natural infection and vaccination with live Anaplasma species remain lifelong carriers (as reviewed by Kocan et al., 2009). Carrier animals are responsible for horizontal, iatrogenic, and vertical transmission of anaplasmosis to naïve cattle by providing a reservoir of infective blood for biological, mechanical, and in utero infection (as reviewed by Kocan et al., 2009; Potgieter and van Rensburg, 1987; Reinbold et al., 2009b).

Historically, chemosterilization of persistently infected cattle has been achieved by use of treatment regimens of both the injectable and oral formulations of tetracycline antibiotics (as reviewed by Kocan et al., 2009). Chemosterilization failed in a recent study (Coetzee et al., 2005) when using 5 daily injections of oxytetracycline administered intravenously at a dosage of 22 mg/kg; furthermore, sensitivity and specificity deficiencies for both the cELISA and a nested PCR (Torioni de Echaide et al., 1998) were revealed. Chemosterilization success is reported in cattle fed chlortetracycline hydrochloride (CTC) at dosages ranging from 1.1 mg/kg for 120 days to 11 mg/kg for 30 to 60 days (Brock et al., 1959; Franklin et al., 1966, 1967, 1965; Richey et al., 1977; Sweet and Stauber, 1978; Twiehaus, 1962); however, these studies should be scrutinized as they are based on the use of insensitive diagnostic tests, such as capillary agglutination and complement fixation, for detecting true positive disease (as reviewed by Kocan et al., 2009). Furthermore, regardless of the type of tetracycline antibiotic used, the relationship between plasma drug concentration and chemosterilization is unknown.

The objectives of this study were to evaluate A. marginale chemosterilization regimens using CTC at 3 different dosages for a fixed duration of treatment; establish the relationship between CTC plasma drug concentration and chemosterilization; estimate the time of chemosterilization as determined by negative assay results revealed by an A. marginale-specific RT-PCR assay; and determine the susceptibility of chemosterilized steers to reinfection with the original Virginia isolate.

2. Materials and methods

Twenty-five preconditioned, Holstein steers were enrolled under the Kansas State University (KSU) Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee protocol No. 2517 and Kansas State University Institutional Biosafety Committee protocol No. 524. Previously, all 25 steers were included in an anaplasmosis iatrogenic transmission study (Reinbold et al., 2009b) that used a previously characterized, Virginia isolate of A. marginale (de la Fuente et al., 2003). As a result of iatrogenic infection with a Virginia isolate of A. marginale, a true positive disease status was confirmed in 6 steers by interpretation in series of bi-weekly test results from a commercially available cELISA (Knowles et al., 1996; Torioni de Echaide et al., 1998) and an A. marginale-specific RT-PCR assay; a true negative disease status was confirmed in the remaining 19 steers by the same methods. In order to assemble a group of 21 steers chronically infected with A. marginale, 15 of the 19 negative steers were randomly assigned to 1 of 6 iatrogenically infected steers. Each of the negative steers received a 5 mL intravenous inoculation of whole blood, which was collected into separate evacuated tubes containing K2EDTA from the assigned iatrogenically infected steer immediately prior to the inoculation of naïve steers, 48 days prior to study initiation. A true positive disease status was confirmed by the diagnostic methodism, as described previously, prior to the start of the chemosterilization study. The 4 remaining, negative steers were splenectomized 36 days prior to the start study to serve as anaplasmosis disease transmission sentinels during the chemosterilization studies.

Steers were randomized by body weight and assigned to receive either a (1) 4.4 mg/kg/day (LD; n = 6); (2) 11 mg/kg/day (MD; n = 6); (3) 22 mg/kg/day (HD; n = 6) CTC treatment groups; or (4) placebo treatment (CONTROL; n = 7). The LD, MD and HD treatment groups each consisted of 5 A. marginale infected steers and 1 splenectomized steer. The CONTROL group consisted of 6 infected steers and 1 splenectomized steer. Steers were collectively 314 ± 29.9 days old and weighed 312.4 ± 47.1, 309.5 ± 43.6, 303.5 ± 47.2 and 320.8 ± 29 kg for the LD, MD, HD and CONTROL treatment groups, respectively. Four dry lot pens located at the KSU Juniatta Beef Cattle research facility accommodated the treatment groups.

A commercial CTC product (Aureomycin 50 Granular®; Alpharma Animal Health, Bridgewater, NJ, USA) was formulated by the Kansas State University feed mill to a final concentration of 591.0, 1,477.3, and 2,954.4 mg of CTC per kg of ground corn carrier for the LD, MD, and HD treatment administered, respectively. These respective drug concentrations ensured that a similar total quantity of treatment was fed per kg body weight regardless of the dosage administered. The CONTROL group received the ground corn carrier as a placebo based on the average weight of top dress fed to the CTC-treated groups.

Steers were acclimated to a total mixed ration diet over a 1-month period. During the study, this diet was rationed twice daily at 1.25% (as fed) of the average pen weight. The daily dietary ration and CTC dosages were determined using the mean weight of the treatment group, which was taken bi-weekly. Daily dosage and ration were divided equally and administered twice daily for 80 days (160 total doses/group). The treatment was distributed evenly across the top of the daily ration that was fed in a 3.7 m long concrete feed bunk (0.61 m/head). The feed bunk was inspected prior to each treatment. Residues from the previous treatment were noted in a daily log sheet; however, observed residues were not removed or weighed. Water was supplied ad libitum. When handling was necessary for the collection of venous blood samples, the steers were individually restrained with a head gate and rope halter. If sample collection coincided with scheduled treatment, samples were collected prior to treatment administration.

2.1. Sample collection and analysis

2.1.1. cELISA

Blood was collected from the jugular vein with evacuated tubes containing no additive. Serum was removed and analyzed for antibody against A. marginale by a commercially available cELISA in accordance with the method described by the OIE and recommended by the manufacturer (OIE, 2009; VMRD, 2010; VMRD-2, 2010). The optical density of each sample was measured by an ELISA plate reader at a wavelength of 620 nm. The optical density was used to calculate a percent inhibition (% inhibition). Samples were considered negative for anaplasmosis if the % inhibition was <30%. All samples with a % inhibition >30% were considered positive (Coetzee et al., 2007; OIE, 2009; Strik et al., 2007; VMRD, 2010).

2.1.2. Real-time RT-PCR assay

Two hundred and fifty microliters of plasma-free whole blood sample was removed from blood samples collected with evacuated tubes containing K2EDTA from the jugular vein. The plasma-free whole blood sample was used to extract RNA using a commercially available product according to manufacturer recommendations (TRI Reagent, Sigma–Aldrich; Saint Louis, MO). The RNA samples were rehydrated with 50 μL of nuclease-free water. An A. marginale-specific real-time RT-PCR assay was used to detect and quantify a highly conserved and specific region of 16S ribosomal RNA subunit (16S rRNA) as previously described (Reinbold et al., 2009b). The RT-PCR assay was optimized over a linear, dynamic range with one hundred to one billion molecules of 16S rRNA template that correspond to cycle threshold (Ct) values from 10 to 35, respectively. Linear regression was used to quantify the number of 16S rRNA template molecules in the 25 μL reaction based on the corresponding Ct value with the following Eq. (1):

| (1) |

where y is the reported Ct value and x is the number of template molecules. The correlation coefficient (R2) for the regression equation was 0.9973. Samples from a known A. marginale carrier and a naïve cow were extracted and analyzed simultaneously for monitoring assay performance and quality of the RNA extraction technique.

2.1.3. Light microscopic examination of stained blood films

Blood films were prepared for light microscopic examination from whole blood collected from the jugular vein in evacuated tubes containing K2EDTA. Blood films were stained with an automated unit (Hema-Tek, Ames Company; Elkhart, IN) using a Modified Wright stain. A total of 1000 erythrocytes were counted in each sample.

2.1.4. Plasma drug concentration analysis

Plasma drug concentrations were determined from whole blood samples collected with evacuated tubes containing lithium heparin. Plasma was subjected to solid phase extraction and analysis with an ultrahigh performance liquid chromatography–mass spectroscopy/mass spectroscopy (UPLC–MS/MS) method as previously described (Reinbold et al., 2009a). The limit of quantitation of the method was 50 ng/mL. Plasma drug concentrations >50 ng/mL were reported and used for analysis.

2.2. Evaluation of infection status

A heparinized, 10 mL whole blood sample was collected from each steer in the LD, MD and HD treatment groups; in addition to the 10 mL sample collected, the typical volume of sample was analyzed, as described, by both the cELISA and RT-PCR assay for assessment of disease status of each steer in these treatment groups. Heparinized whole blood samples were pooled within each treatment group to compose a 50 mL final volume and used to intravenously subinoculate the splenectomized calf assigned to the respective treatment group during the 80-day study. For 6 weeks thereafter, these 3 splenectomized calves were monitored for infection for 6 weeks by the cELISA, light microscopy, and RT-PCR.

2.3. Determining susceptibility to reinfection

After a negative RT-PCR assay result was reported for all CTC-treated steers and chemosterilization was confirmed by the subinoculation of splenectomized calves, steers were continually monitored until the reported % inhibition of the cELISA declined below 40%. Five steers, which were iatrogenically infected in the previous study (Reinbold et al., 2009b), were exposed to reinfection with a frozen stabilate prepared from the same Virginia isolate of A. marginale. This stabilate was prepared from a splenectomized steer used to propagate the isolate in vivo for the previous iatrogenic transmission study (Reinbold et al., 2009b). The stabilate was prepared 280 days prior to the time of exposure from a heparinized, whole blood sample with a 2% parasitemia. The parasitemia at the time of collection was 2%. Four milliliters of stabilate was used to intravenously inoculate each of the five chemosterilized steers. The disease status of these chemosterilized steers was evaluated by cELISA, light microscopic examination of stained blood smears, and RT-PCR assay.

2.4. Chemosterilization of CONTROL group

Upon validation of chemosterilization results for the LD, MD, and HD treatment groups, chemosterilization was assessed in the CONTROL treatment group with a single, subcutaneous injection of a long-acting oxytetracycline (Tetradure 300, Merial Limited, Duluth, GA) at 20 mg/kg followed by 30 days of treatment with CTC at 4.4 mg/kg/day (Fig. 4). The CTC treatment preparation and administration were similar to the LD treatment group. Samples were collected on days 0, 10, 17, 24, 31, and 38 for assessment of disease status by cELISA and RT-PCR. Plasma drug concentrations were not determined during this treatment.

Fig. 4.

Comparison of the A. marginale-specific RT-PCR assay results (open diamonds) and antibody decline against A. marginale detected by cELISA (open triangles) in six steers treated with a subcutaneous injection of a long-acting oxytetracycline (300 mg/mL) at 20 mg/kg and 30 days of treatment with oral chlortetracycline at 4.4 mg/kg/day. The end of treatment with CTC treatment is indicated (closed circle) on the x-axis. Data points are represented as the geometric mean and CV% (error bars) of results reported during analysis.

2.5. Statistical analysis

Data were entered into a software package (Microsoft Excel 2007, Microsoft Corporation; Redmond, WA) for subsequent calculations and manipulation. Geometric mean and CV% were calculated for data acquired from responses recorded from diagnostic assay results. Diagnostic assay results were converted to a binary format (0, negative; 1, positive). Comparisons were made between iatrogenically infected and subinoculated steers for diagnostic method results for cELISA and the RT-PCR using mixed procedures (PROC Mixed, SAS version 9.1; SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC). A semi-parametric survival analysis was performed to analyze the variation in time to A. marginale clearance (represented as hazard ratios) between the 3 CTC chemosterilization regimens and the regimen using CTC and oxytetracycline (Stata version 10.1; Stata Corp. LP, College Station, TX). An alpha level of 0.05 was observed throughout the study for evaluating statistically significant differences.

3. Results

The mean weight among treatment groups was not significantly different at the initiation (P = 0.943) and completion of treatment (P = 0.93). Initially, there was a significant difference in the log10 number of A. marginale organisms per mL of plasma-free blood sample between the 6 steers that were iatrogenically infected and the 15 steers subinoculated with blood collected from the iatrogenically infected steers (P < 0.0001); however, there was no significant difference among treatment groups after randomization (P = 0.16). No significant difference was detected among the reported % inhibition results of the cELISA for the iatrogenically infected and subinoculated steers prior to randomization (P = 0.86). One splenectomized steer was removed from the study as a result of death caused by post-surgical hemorrhage from an aneurysm of the splenic vein; furthermore, thiscomplication reduced the numberofsteers in the CONTROL group to 6 A. marginale infected steers.

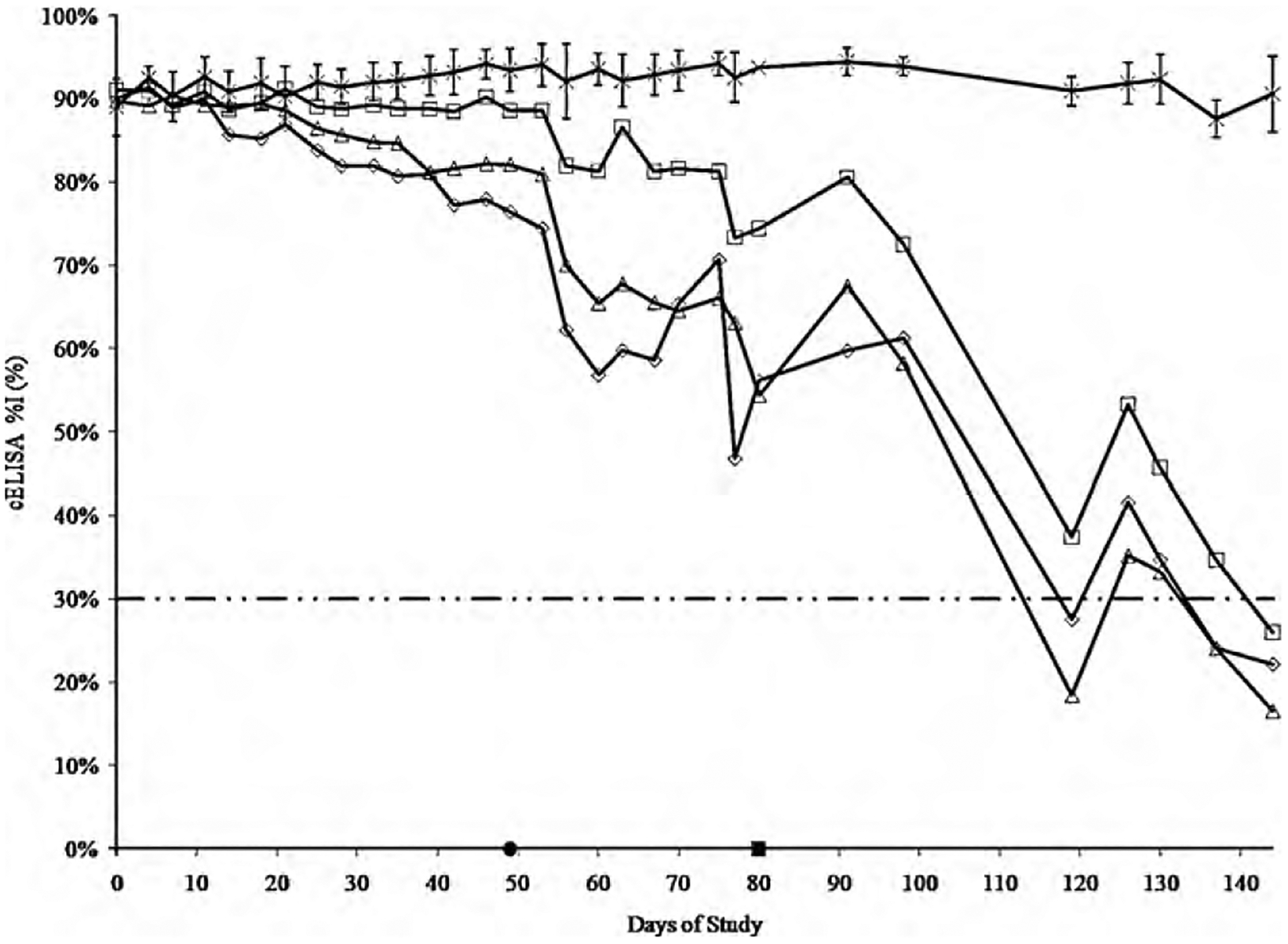

When assessing disease status by the RT-PCR assay, the LD, MD and HD groups tested negative for A. marginale infection following 46, 46, and 49 days of CTC treatment, respectively (Fig. 1). There was no significant difference detected when comparing the time of a negative assay status between the LD and MD (P = 0.07) as well as the MD and HD (P = 0.30) treatment groups; however, a significant difference was detected between the LD and HD (P = 0.005) treatments. There was no significant difference detected between the time of a negative assay status and cELISA results (P = 0.43). The results of the cELISA did not indicate a negative disease status until 18, 54, and 18 days after the completion of the 80-day CTC treatment regimen in the LD, MD, and HD treatment groups, respectively (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Comparison of the A. marginale-specific RT-PCR assay results during an 80-day treatment with placebo in the CONTROL group (open circles; n = 6) and oral chlortetracycline in the LD (open diamonds; n = 5), MD (open squares; n = 5), and HD (open triangles; n = 5) groups. Data points are represented as the geometric mean of the log10 number of A. marginale bacteria in 1 mL of plasma-free blood sample reported during analysis. The geometric CV% is included as error bars for the CONTROL group.

Fig. 2.

Comparison of the rate of antibody decline against A. marginale detected by cELISA. The data series represented are the CONTROL (crosses; n = 6), LD (open diamonds; n = 5), MD (open squares; n = 5), and HD (open triangles; n = 5) treatment groups. Data points are represented as the geometric mean of the % inhibition reported during analysis. The geometric CV% is included as error bars for the CONTROL group. The cut-off point recommended by the manufacturer for interpretation of negative disease status is represented as 30% inhibition (- · · -). The cumulative time to a negative disease status detected by the RT-PCR assay is represented on the x-axis (closed circle). The end of treatment is represented on the x-axis (closed square).

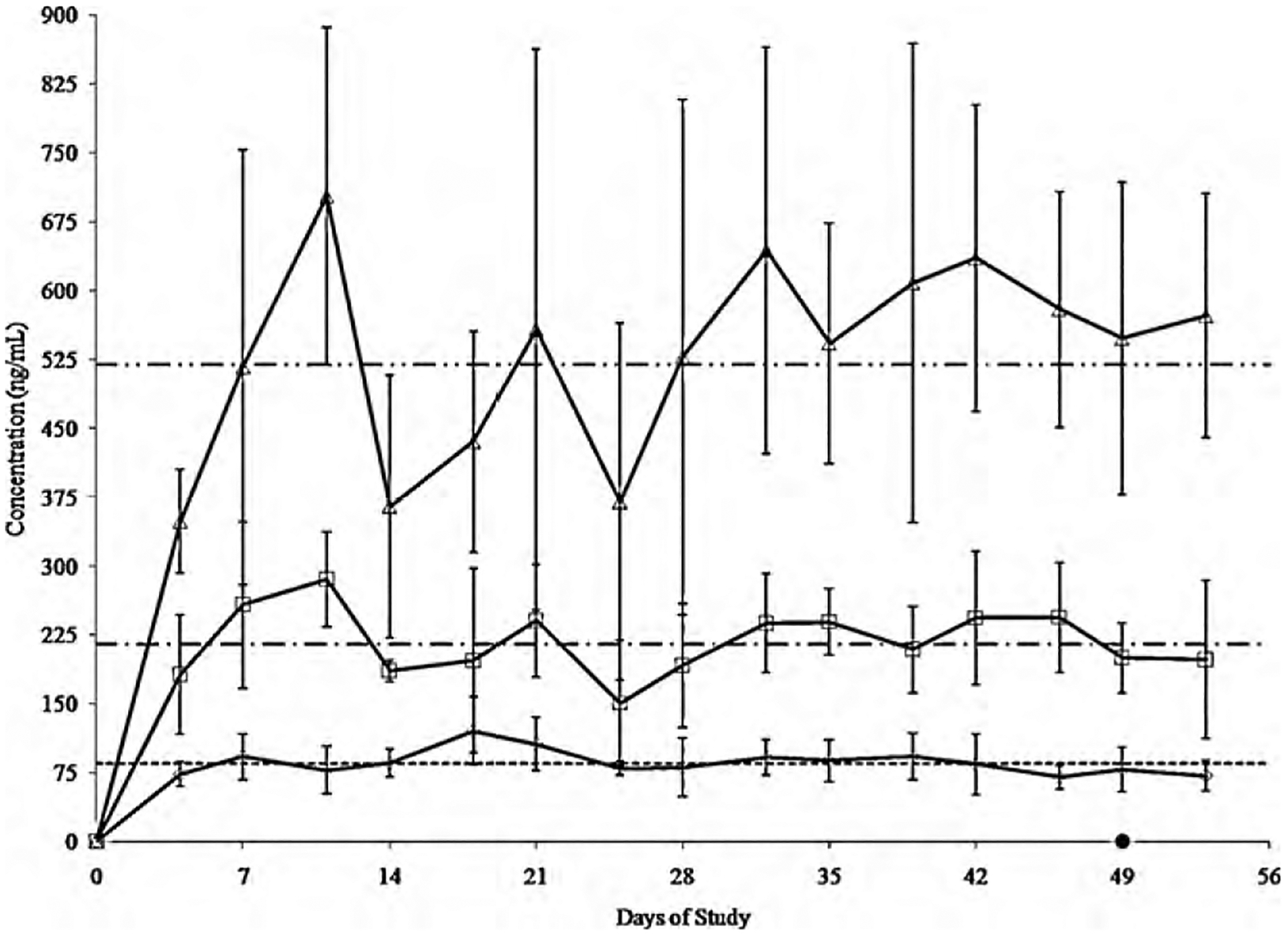

Oral administration of all treatments was well tolerated throughout the study. Feed bunk spatial allocation of 0.61 m/head was adequate to allow each steer equal opportunity to consume the daily ration and treatment. However, a remarkable level of intra- and inter-individual variability of plasma drug concentrations was observed within treatment groups (Fig. 3). The geometric mean (CV%) of plasma drug concentrations collected on days 4 through 53 of the study for the LD, MD, and HD treatment groups were 85.3 (28), 214.5 (32), and 518.9 (40) ng/mL, respectively.

Fig. 3.

Comparison of plasma drug concentrations achieved with 4.4, 11, and 22 mg/kg/day of oral chlortetracycline in the LD (open diamonds; n = 6), MD (open squares; n = 6), and HD (open triangles; n = 6) treatment groups, respectively. Data points are represented as the geometric mean and CV% (error bars) of plasma drug concentrations reported during analysis. The cumulative time to a negative disease status detected by the RT-PCR assay for all steers treated with chlortetracycline in the LD, MD, and HD treatment groups is represented on the x-axis (closed circle). A geometric mean is included for plasma drug concentrations (n = 90/treatment) recorded on days 4 through 53 of treatment in the LD (85.3 ng/mL; -), MD (214.5 ng/mL; - · -), and HD (518.9 ng/mL; - · · -) treatment groups.

The CONTROL group was not chemosterilized during the 80-day study. However beginning 68 days after the end of the 80-day oral treatment study, these steers were subsequently chemosterilized with a single, subcutaneous injection of a long-acting oxytetracycline followed by 30 days of treatment with CTC at 4.4 mg/kg/day (Fig. 4). Plasma drug concentrations were not determined during this treatment.

Chemosterilization, as assessed by the cELISA and RT-PCR assays, was confirmed through subinoculation of splenectomized steers. Three splenectomized steers, subinoculated with a pooled blood samples collected from chemosterilized steers 50 days after the end of the 80-day study, were monitored for infection for 6 weeks by cELISA, light microscopy, and RT-PCR. No change in disease status of the splenectomized steers was detected by these methods. Similarly, there was no change in disease status of a splenectomized steer subinoculated with blood collected from the CONTROL group 12 days after chemosterilization with oxytetracycline and CTC.

Results from the semi-parametric survival analysis were expressed as hazard ratios. Hazard ratios, interpreted similarly as odds ratios, were assumed to be proportional over time and represent the effect of a unit change in the predictor on the frequency of the outcome (Le, 2003). Steers in the CONTROL group chemosterilized by use of CTC and oxytetracycline were 5.67 (1.4, 23.2; P < 0.016), 5.4 (1.4, 21.5; P = 0.016) and 7.6 (1.7, 33.0; P = 0.007) times more likely to be chemosterilized sooner than the LD, MD, and HD groups, respectively.

All five steers, which were included in the CTC treatment groups that were chemosterilized and were the 5 original steers used to subinoculate 15 naïve steers prior to the start of the present study, were reinfected by a stabilate of the Virginia isolate of A. marginale used to infect these steers (Reinbold et al., 2009b). Antibodies were detected by the cELISA as early as 10 days, but by 24 days of exposure in all steers. Infection was detected by the RT-PCR assay 10 days after reinfection in 4 steers, and in all 5 steers 17 days after reinfection. A splenectomized steer subinoculated with a pooled blood sample collected from the reinfected steers was monitored by cELISA, light microscopy, and RT-PCR for change in disease status. Reinfection was confirmed in the splenectomized steer with positive test results for all 3 diagnostic methods within 21 days following subinoculation.

4. Discussion

To our knowledge, our study is the first to establish a relationship between chlortetracycline plasma drug concentration and chemosterilization of steers persistently infected with a Virginia isolate of A. marginale using 3 different dosages of CTC for a fixed duration. Dosages were selected based upon a CTC pharmacokinetic study (Reinbold et al., 2009a) reporting dose linearization of plasma drug concentrations among the CTC dosages prescribed in the present study. Accordingly, these dosages were prescribed to determine if dose combined with a fixed duration of treatment affected the apparent rate of chemosterilization. All CTC dosages yielded a sustainable plasma drug concentration necessary for chemosterilization in the LD, MD, and HD treatment groups. However, these plasma drug concentrations were less than the minimum inhibitory concentration (2 μg/mL) recommended for the treatment of bacterial infection caused by Mannheimia haemolytica, Pasteurella multocida, or Histophilus somnii with a 200 mg/mL injectable oxytetracycline product (CLSI, 2008). Therefore, the success of an A. marginale chemosterilization strategy should not be based on the aforementioned minimum inhibitory concentration. Furthermore, the treatment regimens outlined in this study may differ for different isolates, thus requiring further testing of currently circulating strains.

A significant difference was detected when comparing regimens using CTC treatment to a regimen using a combination of oral and injectable formulations of tetracycline antibiotics. This was likely because of the time of maximum concentration occurring earlier when a 300 mg/mL preparation of oxytetracycline (4.7 h) (Dowling and Clark, 2003) is administered as compared with the LD (38.4 h), MD (42.1 h) and HD (41.5 h) treatments (Reinbold et al., 2009a).

The mechanism for the extensive duration of treatment necessary for chemosterilization is unknown. However, the absorption of tetracycline into the erythrocyte has been characterized as a simple diffusion process (DeLoach and Wagner, 1984). Once inside the erythrocyte, drug passes as a cation through porin channels of the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria into the periplasm, becomes an uncharged molecule to diffuse through the inner cytoplasmic membrane, and reversibly binds to the 30S ribosome to inhibit protein synthesis (Chopra and Roberts, 2001). The reversible binding of tetracyclines to the 30S ribosome and lifespan of parasitized erythrocytes may be key contributors to this phenomenon. However, the concentration of drug achieved in parasitized erythrocytes may be inadequate for a bactericidal effect. Efflux and ribosomal protection proteins, as well as enzymatic inactivation, are mechanisms of resistance to counteract the efficacy of antibiotics during treatment. These mechanisms are driven by numerous resistance genes found in commensal and pathogenic bacteria today (Chopra and Roberts, 2001). It is noteworthy that 2 multidrug resistant pumps have been identified (Brayton et al., 2005) in a Saint Maries isolate of A. marginale; however, the significance of this finding in the treatment of cattle persistently infected with A. marginale is unknown. Additionally, it may be likely that the inhibition of protein synthesis by tetracycline antibiotics may prevent the infection of non-parasitized erythrocytes. However, parasitized erythrocytes must still be removed from circulation by erythrophagocytosis in the spleen. Ultimately, carrier clearance is influenced by an extensive drug absorption process, reversible binding of the tetracycline antibiotic to the 30S ribosome, the potential for antimicrobial resistance, and erythrophagocytosis of parasitized erythrocytes.

In the United States, CTC is only labeled for the control of active infection of anaplasmosis caused by A. marginale susceptible to CTC in cattle (2009 Feed Additive Compendium). Historically, the continuous feeding of CTC to naïve cattle in high risk areas for anaplasmosis infection is advocated during the vector season (Brock et al., 1957). As a result of the findings of our study, the recommendation of this practice should be scrutinized because of the potential to inadvertently disrupt endemic stability by chemosterilizing infected cattle; furthermore, chemosterilized cattle are susceptible to reinfection. The development and application of improved animal husbandry practices (Reinbold et al., 2009b), as well as establishment of an endemically stable herd (Figueroa et al., 1998), could considerably reduce the need for tetracycline antibiotics when attempting to control anaplasmosis in cattle. However, the existence of an endemically stable herd does not permit the commingling of cattle of unknown disease status or reduce trade restrictions between endemic and non-endemic countries.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the following grants: USDA CREES 1433 grant (AES project number: 481851) and AI070908 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. The authors wish to acknowledge the invaluable contributions of the following KSU faculty, staff, and students who assisted with sampling and care of the study animals: Dr. David Anderson, Dr. Brian V. Lubbers, Dr. Michael D. Apley, Angela Baker, Laura Barbur, Lauren Calland, Charley Cull, Pilar Gunter, Jamie Kotschwar, Nathan Kotschwar, Amanda Sherck, and Kara Smith.

References

- Brayton KA, Kappmeyer LS, Herndon DR, Dark MJ, Tibbals DL, Palmer GH, McGuire TC, Knowles DP Jr., 2005. Complete genome sequencing of Anaplasma marginale reveals that the surface is skewed to two superfamilies of outer membrane proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 102, 844–849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brock WE, Pearson CC, Kliewer IO, 1959. Anaplasmosis control by test and subsequent treatment with chlortetracycline. Proc. US Livestock San Assoc 62, 66–70. [Google Scholar]

- Brock WE, Pearson CC, Staley EE, Kliewer IO, 1957. The prevention of anaplasmosis by feeding chlortetracycline. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc 130, 445–446. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chopra I, Roberts M, 2001. Tetracycline antibiotics: mode of action, applications, molecular biology, and epidemiology of bacterial resistance. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev 65, 232–260 second page, table of contents. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CLSI, 2008. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Disk and Dilution Susceptibility Tests for Bacteria Isolated from Animals; Approved Standard, third ed., CLSI document M31-A3, Table 2.28, pp. 65–72. [Google Scholar]

- Coetzee JF, Apley MD, Kocan KM, Rurangirwa FR, Van Donkersgoed J, 2005. Comparison of three oxytetracycline regimes for the treatment of persistent Anaplasma marginale infections in beef cattle. Vet. Parasitol 127, 61–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coetzee JF, Schmidt PL, Apley MD, Reinbold JB, Kocan KM, 2007. Comparison of the complement fixation test and competitive ELISA for serodiagnosis of Anaplasma marginale infection in experimentally infected steers. Am. J. Vet. Res 68, 872–878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de la Fuente J, Blouin EF, Kocan KM, 2003. Infection exclusion of the rickettsial pathogen Anaplasma marginale in the tick vector Dermacentor variabilis. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol 10, 182–184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLoach JR, Wagner GG, 1984. Pharmacokinetics of tetracycline encapsulated in bovine carrier erythrocytes. Am. J. Vet. Res 45, 640–642. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowling PM, Clark C, 2003.PharmacokineticsComparison:Bio-mycin200 and Tetradure. , pp. 1–2http://www.bi-vetmedica.com/BIMS/docs_ts/TB03-108.pdf?-session=BISITE:D8A83FAA118e216BBDvOg1456A5D.

- Feed Additive Compendium, 2009. Chlortetracycline. Feedstuffs 46, 223–229. [Google Scholar]

- Figueroa JV, Alvarez JA, Ramos JA, Rojas EE, Santiago C, Mosqueda JJ, Vega CA, Buening GM, 1998. Bovine babesiosis and anaplasmosis follow-up on cattle relocated in an endemic area for hemoparasitic diseases. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci 849, 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin TE, Cook RW, Anderson DJ, 1966. Fedding chlortetracycline to range cattle to eliminate the carrier state of anaplasmosis. Proc. US Livestock San Assoc 66, 85–90. [Google Scholar]

- Franklin TE, Cook RW, Anderson DJ, Kuttler KL, 1967. Medium and low level feeding of chlortetracycline with comparisons to anaplasmosis CF and CA tests. Southwest Vet. 20, 101–104. [Google Scholar]

- Franklin TE, Huff JW, Grumbles LC, 1965. Chlortetracycline for elimination of anaplasmosis in carrier cattle. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc 147, 353–356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knowles D, Torioni de Echaide S, Palmer G, McGuire T, Stiller D, McElwain T, 1996. Antibody against an Anaplasma marginale MSP5 epitope common to tick and erythrocyte stages identifies persistently infected cattle. J. Clin. Microbiol 34, 2225–2230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kocan KM, de la Fuente J, Blouin EF, Coetzee JF, Ewing SA, 2009. The natural history of Anaplasma marginale. Vet. Parasitol. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le CT, 2003. Introductory Biostatistics, first ed. John Wiley and Sons, Inc., Hoboken, NJ. [Google Scholar]

- OIE, 2009. Office International des Épizooties, Manual of Standards for Diagnostic Tests and Vaccines for Terrestrial Animals, 17th ed. (Chapter 2.4.1, accessed 13.7.09)http://www.oie.int/eng/normes/mmanual/2008/pdf/2.04.01_BOVINE_ANAPLASMOSIS.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Potgieter F, van Rensburg L, 1987. The persistence of colostral Anaplasma antibodies and incidence of in utero transmission of Anaplasma infections in calves under laboratory conditions. Onderstepoort J. Vet. Res 54, 557–560. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinbold JB, Coetzee JF, Gehring R, Havel JA, Hollis LC, Olson KC, Apley MD, 2009. Plasma pharmacokinetics of oral chlortetracycline in group fed, ruminating, Holstein steers in a feedlot setting. J. Vet. Pharm. Ther 9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinbold JB, Coetzee JF, Hollis LC, Nickell JS, Riegel C, Christopher-Huff J, Ganta RR, 2009. Comparison of iatrogenic Anaplasma marginale transmission by needle and needle-free injection techniques. Am. J. Vet. Res (Provisional acceptance: AJVR-09-07-0279). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richey EJ, Brock WE, Kliewer IO, Jones EW, 1977. Low levels of chlortetracycline for anaplasmosis. Am. J. Vet. Res 38, 171–172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strik NI, Alleman AR, Barbet AF, Sorenson HL, Wamsley HL, Gaschen FP, Luckschander N, Wong S, Chu F, Foley JE, Bjoersdorff A, Stuen S, Knowles DP, 2007. Characterization of Anaplasma phagocytophilum major surface protein 5 and the extent of its cross-reactivity with A. marginale. Clin. Vaccine Immunol 14, 262–268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweet VH, Stauber EH, 1978. Anaplasmosis: a regional serologic survey and oral antibiotic therapy in infected herds. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc 172, 1310–1312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torioni de Echaide S, Knowles DP, McGuire TC, Palmer GH, Suarez CE, McElwain TF, 1998. Detection of cattle naturally infected with Anaplasma marginale in a region of endemicity by nested PCR and a competitive enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay using recombinant major surface protein 5. J. Clin. Microbiol 36, 777–782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Twiehaus MJ, 1962. Control of anaplasmosis by feeding an antibiotic (Aureomycin). In: Proc. 4th Natl. Anaplasmosis Conf pp. 48–49. [Google Scholar]

- VMRD (Veterinary Medical Research & Development (VMRD), Inc.), 2010. Anaplasma antibody test kit, cELISA. USDA Product Code 5002.5020 for veterinary use only. pp. Assay instructions for catalog numbers: 282–282 and 282–285.

- VMRD-2 (Veterinary Medical Research & Development (VMRD), Inc.), 2010. Product information sheet: Anaplasma antibody test kit, cELISA (www.vmrd.com/docs/tk/Anaplasma/Anaplasma_Flyer_050113.pdf).