Abstract

Deep brain stimulation is a promising treatment for severe depression, but lack of efficacy in randomized trials raises questions regarding anatomical targeting. We implanted multi-site intracranial electrodes in a severely depressed patient and systematically assessed the acute response to focal electrical neuromodulation. We found an elaborate repertoire of distinctive emotional responses that were rapid in onset, reproducible, and context and state dependent. Results provide proof of concept for personalized, circuit-specific medicine in psychiatry.

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is a common, highly disabling disorder1 associated with a high level of treatment resistance2. Deep brain stimulation (DBS) emerged in 2003 as a highly promising addition to the therapeutic armamentarium3 for the most refractory patients2. However, early tantalizing results were not consistently replicated across three randomized, controlled studies4–6. Although trial design might have been a key factor in trial outcome7,8, low response rates suggest that novel strategies in DBS treatment are needed7. One such strategy is personalization of DBS circuit targeting, which is supported by positive findings in open-label DBS studies targeting different brain regions3,9. Personalization of therapy is proposed as a means to improve outcomes in medicine generally but has remained elusive in the field of psychiatry10. Direct neural recordings and intracranial stimulation are promising tools for evaluating whether it is possible to establish proof of concept for a circuit-targeted precision medicine approach, where dysfunctional neural circuits are reliably identified and targeted to change a specific set of symptoms experienced by an individual. It has been shown that engagement of brain stimulation targets based on patient-level anatomy can improve outcome in DBS for depression11,12, and personalized electrocortical stimulation mapping is considered the gold standard for functional cortex localization before surgical resection in epilepsy13. In this study, we built on these two approaches and the early intracranial stimulation work of Bishop et al.14 by carrying out personalized electrocortical stimulation mapping that could serve as a basis for personalized DBS in depression. We implanted temporary intracranial electrodes across corticolimbic circuits for a 10-d inpatient monitoring interval to evaluate responses to an array of focal stimulations and to establish the relationships between stimulation characteristics and clinical response. Here we describe the findings from stimulus–response mapping and demonstrate new properties of brain stimulation responses that provide proof of concept for personalized medicine in psychiatry.

The patient was a 36-year-old woman with severe treatment-resistant MDD (trMDD) (Montgomery Asberg Depression Rating Scale: 36/54) with childhood onset and a family history of suicide. She had three distinct lifetime episodes of depression with periods of better functioning in between and experienced the full constellation of depression symptoms within each episode. Her primary symptoms of the most recent 4-year episode included anhedonia, anergy and cognitive deficits. This depression episode was not adequately responsive to four antidepressant medications, augmentation strategies, electroconvulsive therapy and transcranial magnetic stimulation (Supplementary Information). Owing to her level of treatment resistance, she was enrolled in a clinical trial of personalized closed-loop DBS for trMDD.

This trial included a 10-d exploratory stage, where ten stereoelectroencephalography electrodes (160 contacts) were implanted across the orbitofrontal cortex (OFC), amygdala, hippocampus, ventral capsule/ventral striatum (VC/VS) and subgenual cingulate (SGC)3,9,15–17 bilaterally for the purpose of personalized target selection. During this time, we assessed clinical response to a pre-selected set of stimulation parameters using a five-point Likert scale combining subjective responses with physician-rated affect, visual analog scales of depression, anxiety and energy and a six-question subscale of the 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale18. An elaborate repertoire of emotions across different sites and stimulation parameters was observed with ∼90 s of stimulation (summarized in Fig. 1a). For example, she reported ‘tingles of pleasure’ with 100-Hz VC/VS stimulation, ‘neutral alertness … less cobwebs and cotton’ with 100-Hz SGC stimulation and calm pleasure ‘like … reading a good book’ with 1-Hz OFC stimulation. Despite the patient being blinded to the stimulation site, her verbal reports were remarkably consistent with many reports in the literature15,19,20 and revealed new associations as well, such as the anxiolytic, sedating effects of the OFC (Fig. 1b).

Fig. 1 |. Mapping mood across the corticolimbic circuit.

a, Examples of the clinical responses to ∼90 s of stimulation. Electrodes that demonstrated a positive or negative mood response to stimulation are enlarged for emphasis and shaded with color of respective region. b, Relationship of patient response to literature. c, Covariance matrix of relationship between depression measures (Methods) (left) and heat map of average Likert scores per stimulation condition (right). Somatic symptoms (side effects) of stimulation are also shown. d, Location of stereoelectroencephalography leads in the VC/VS, SGC and OFC with neighboring fiber tracts defined by diffusion tensor imaging. Left, Anterior thalamic radiations and VC–brainstem tracts (inset); middle, forceps minor, stria terminalis/cingulum bundle and uncinate fasciculus; and right, forceps minor and uncinate fasciculus. AMY, amygdala; HAMD, Hamilton Depression Rating Scale; HPC, hippocampus; VAS, Visual Analog Scale.

Stimulation paradigms that exhibited positive responses were tested with sham-controlled stimulation with 3-min stimulation periods. We were surprised to identify three paradigms in a single patient that all reliably improved symptoms but targeted different dimensions of depression (Fig. 1c). Two of these paradigms—100-Hz stimulation of the SGC3 and the VC/VS9—were consistent with previous DBS studies. The third was a novel location and stimulation condition: low-frequency stimulation across a broad region of the OFC (Fig. 1d).

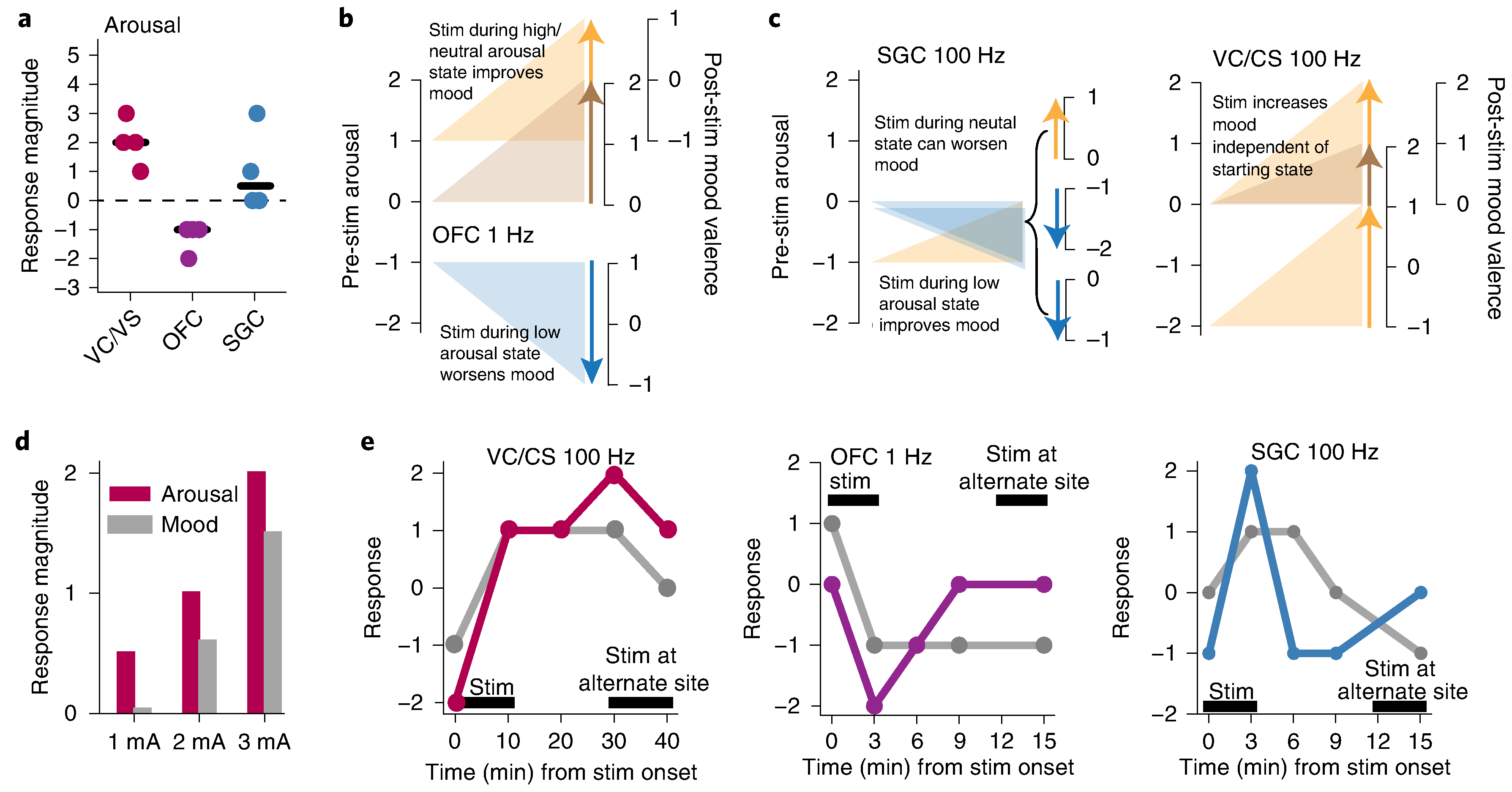

We next tested brain–behavioral relationships of prolonged stimulation (10 min) at these three stimulation paradigms. Notably, we observed that response to stimulation interplayed closely with the patient’s core symptoms and symptom state at the time of stimulation. First, we found that responses were reproducible as a function of context and state at time of stimulation on 100% of trials that elicited a response (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Information). For example, in the OFC, the effect was positive and calming if delivered during a high/neutral arousal state but worsened mood if delivered during a low arousal state, causing the patient to feel excessively drowsy (Fig. 2b). The opposite pattern was observed in the SGC and VC/VS—regions where stimulation increased arousal (Fig. 2c). This patient’s primary symptom was anhedonia, and she perceived the most consistent benefit from stimulation in one region of the VC/VS. However, when she was in a highly aroused state, broad OFC stimulation was preferred. We next examined properties of the stimulation response that would inform whether it would be possible to deliver stimulation specifically when a particular symptom state is present. We found a clear dose response for both activation and mood valence (Fig. 2d) and found that the response to simulation was sustained beyond the stimulation period itself, even up to 40 min (Fig. 2e).

Fig. 2 |. Characterization of response properties.

a, Effect of stimulation on arousal dimension of depression across four trials of stimulation in each brain region. b, State dependence for OFC stimulation. The left axis marks the arousal state before stimulation; the right axis shows mood state (Mood_V) measured after stimulation. c, State dependence for SGC and VC/CS stimulation. d, Dose dependence of stimulation for VC/VS on dimensions of both mood and anxiety. Each bar represents response after one trial of stimulation at 1, 2 or 3 mA. e, Response durability for example trials are shown for VC/CS (red), OFC (purple) and SGC (blue) for both arousal (colored line) and Mood_V (gray line). The black bar indicates the duration of stimulation.

In summary, we present a novel approach to DBS that includes a 10-d inpatient interval where multi-day, multi-site stimulation—response mapping is performed before implantation of a chronic neuromodulation device to characterize the complex interplay among symptoms, mood state and neural stimulation. These findings extend previous work that suggested that different stimulation targets within and across brain regions have different clinical effects12 and further demonstrate the putative importance of a patient’s symptom profile in interpreting the clinical response to stimulation. Furthermore, they suggest that the time a patient spends in a particular mood state could be a consideration in the selection of a DBS target. Although traditional DBS delivers stimulation continuously, ‘closed-loop’ DBS aims to vary stimulation parameters in response to ongoing changes in the state of neural networks7. The conceptual framework of a closed-loop approach is that brief intermittent stimulation delivered only when the patient is in a target state can be delivered on a long-term basis and could be a means of treating chronic depression. Although our results do not contain neurophysiological findings that would be needed to drive closed-loop therapy, our findings that the response to stimulation is rapid in onset, dose dependent, sustained beyond the stimulation itself and context dependent suggest that a closed-loop strategy is of interest for further study in trMDD. Future work will be needed to determine inter-individual variability in stimulus—response relationships. Nonetheless, this case establishes network principles and methodology for implementation of a precision medicine paradigm for circuit-targeted therapy. The principles we established extend to noninvasive modulation of brain circuitry that could allow circuit-targeted personalized therapy to be broadly available to people with MDD.

Online content

Any methods, additional references, Nature Research reporting summaries, source data, extended data, supplementary information, acknowledgements, peer review information; details of author contributions and competing interests; and statements of data and code availability are available at https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-020-01175-8.

Online Methods

Surgical Procedure

The patient gave written informed consent for participation in a clinical trial of closed-loop DBS for trMDD (Presidio: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04004169), approved by the institutional review board and food and drug administration (FDA). The patient was surgically implanted with ten stereoelectroencephalography (SEEG) electrodes (PMT Corporation, Chanhassen, MN) within the most promising sites bilaterally for modulating depression based on published literature1–5: the orbitofrontal cortex (OFC), amygdala, hippocampus, VC/VS, and the SGC (Figure 1A). Surgical targeting was planned in Brainlab iPlan Cranial Software using DTI6 or coordinate-based targeting7 in accordance with published work. Computerized tomography (CT) was used intraoperatively to confirm electrode placement. No complications of surgery occurred. Exploratory intracranial stimulation and recording took place over a 10-day period (Oct 2019). After the 10-days the electrodes were explanted.

Mood Assessments

There are currently no well-validated measures that assess acute changes in symptom severity. Prior DBS studies for psychiatric disorders have used patients’ subjective responses7 or visual analog scales (VAS)8. We serially assessed clinical symptoms multiple times a day for 10 days in three independent ways: i) a 5-point Likert scale combining subjective responses with physician rated affect (−2 to 2 on dimensions of arousal and mood valance (Mood_V), −2 to 0 for somatic side effects (nausea, flushing)), ii) VAS’s of depression (VAS-D), anxiety (VAS-A), and energy (VAS-E), and iii) the HAMD6 subscale of the HAMD-17 which is thought to capture the core-symptoms of the full-scale and has been used to assess the rapid effects of antidepressants9,10. Our symptom assessment strategy included an a priori plan to consider dimensions of depression that can change in the course of a day as represented in the HAMD6 subscale of the HAMD-17, which includes: Q1) sadness, Q2) guilt, Q3) apathy, Q4) fatigue, Q5) anxiety, and Q6) energy9 but focus only on the dimensions that were possible to meaningfully operationalize in the setting of repeated testing with a VAS and were the smallest number needed to reflect the symptom profile of the patient (sadness, anxiety, energy). This allowed us to balance the need to capture the needed number of dimensions while minimizing the known fatigue/data quality issues that can arise with repeated administration of scales. We found that mood valence (happiness/sadness) and energy/arousal accounted for most of the variance in symptoms in this subject (Figure 1c) and we therefore further reduced the analysis to these two dimensions for this case. Although it is understood that we were not sampling the full range of dimensions that can exist in patients with depression, this methodology was intended only to help us establish “proof of concept” for our approach. Improving our capacity to optimally assess clinical depression symptoms in the setting of this type of work will be an important area for future work. Scales were administered at resting-state and before and after stimulation at each location. The patient was blind to stimulation parameters and the region being stimulated.

Diffusion Tensor Imaging

Diffusion data was acquired using axial DTI High Angular Resolution Diffusion Imaging (HARDI) at 3Tesla with a 32-channel head coil (B-Value: 2000 s/mm2, 55 directions). Tractography was performed using deterministic fiber assignment by continuous tracking (FACT)11, implemented within BrainLAB FiberTracking software. In Figure 1d, average fiber fractional anisotropy (FA) and length was 0.44 and 97mm for VC/CS contacts 2/3, 0.3, 121mm for SGC contact 3, and 0.33, 90mm for the OFC contacts 1–7.

Electrode Stimulation

We tested a preselected set of stimulation parameters through a systematic bipolar stimulation survey (∼90s stimulation at each parameter). We utilized a frequency of 100Hz, pulse-width of 100us, and amplitudes of 1–6mA based on previous work utilizing iEEG stimulation that found these parameters to be safe and result in positive mood-related responses3. Based on literature that supports frontal cortical low frequency stimulation, particularly on the right side, we additionally tested 1Hz stimulation in the OFC12. From this survey, we selected a reduced set of parameters for further testing with blinded, sham-controlled stimulation (3 minutes epochs of stimulation, sham and baseline). The three best stimulation configurations were then tested during longer stimulation periods (10min). Where indicated brain stimulation configuration is represented by contact number and polarity (ex. 2+/3− reflects that contact 2 is cathode, contact 3 is anode).

Relationship of patient response to literature

Key emotion terms were searched in PubMed using MeSH terms to specify type of study (human vs. animal model, electrocorticography vs. MRI and brain region). The number of papers that pair the behavioral response with the brain region is reported in relation to papers that cite the behavioral response across all brain region (region + modality) and behavioral response and brain region across all modalities (total citing region and term) (Figure 1b).

Characterization of Response Properties

The effect of stimulation on the arousal dimension of depression was measured by taking the difference in response magnitude on this Likert scale after stimulation compared to before stimulation for paradigms in each brain region. To measure state dependence, the effect of stimulation on mood (Mood_V) was examined in relation to the starting arousal state.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health award K23NS110962 (to K.W.S.), a NARSAD Young Investigator grant from the Brain and Behavioral Research Foundation (to K.W.S.) and the Ray and Dagmar Dolby Family Fund through the Department of Psychiatry at the University of California, San Francisco (to K.W.S., A.D.K., E.F.C. and L.P.S.). E.F.C. was supported by the National Institutes of Health (U01NS098971, R01MH114860, R01MH111444, R01DC015504, R01DC01237, UH3 NS109556, UH3NS115631 and R01 NS105675), the New York Stem Cell Foundation, the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, the McKnight Foundation, the Shurl and Kay Curci Foundation and the William K. Bowes Foundation. A.D.K. acknowledges support from the National Institutes of Health (P01AG019724, R01 HL142051-01, R01AG059794, R01DK117953, UH3 NS109556-01 and R01AG060477-01A1), PCORI, Janssen, Jazz, Axsome (AXS-05-301) and Reveal Biosensors. L.P.S. receives support from the National Institutes of Health (U24 DA041123).

Footnotes

Competing interests

A.D.K. consults for Eisai, Evecxia, Ferring, Galderma, Harmony Biosciences, Idorsia, Jazz, Janssen, Merck, Neurocrine, Pernix, Sage, Takeda, Big Health, Millenium Pharmaceuticals, Otsuka Pharmaceuticals, and Neurawell. All other authors declare no competing interests.

Reporting Summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Code availability

The code and data used to produce the figures in this paper are available at https://github.com/ScangosLab/PR01.

Additional information

Supplementary information is available for this paper at https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-020-01175-8.

Peer review information Jerome Staal and Kate Gao were the primary editors on this article and managed its editorial process and peer review in collaboration with the rest of the editorial team.

Reprints and permissions information is available at www.nature.com/reprints.

Data availability

The source data that support the findings in this report are available in the report itself, in the Supplementary Information and in our publicly available code. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

- 1.Disease GBD, Injury I & Prevalence C Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2017. Lancet 392, 1789–1858 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Howland RH Sequenced treatment alternatives to relieve depression (STAR*D). Part 2: study outcomes. J. Psychosoc. Nurs. Ment. Health Serv. 46, 21–24 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mayberg HS et al. Deep brain stimulation for treatment-resistant depression. Neuron 45, 651–660 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Holtzheimer PE et al. Subcallosal cingulate deep brain stimulation for treatment-resistant depression: a multisite, randomised, sham-controlled trial. Lancet Psychiatry 4, 839–849 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dougherty DD et al. A randomized sham-controlled trial of deep brain stimulation of the ventral capsule/ventral striatum for chronic treatment-resistant depression. Biol. Psychiatry 78, 240–248 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bergfeld IO et al. Deep brain stimulation of the ventral anterior limb of the internal capsule for treatment-resistant depression: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry 73, 456–464 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scangos KW & Ross DA What we’ve got here is failure to communicate: improving interventional psychiatry with closed-loop stimulation. Biol. Psychiatry 84, e55–e57 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mayberg HS, Riva-Posse P & Crowell AL Deep brain stimulation for depression: keeping an eye on a moving target. JAMA Psychiatry 73, 439–440 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Malone DA Jr. et al. Deep brain stimulation of the ventral capsule/ventral striatum for treatment-resistant depression. Biol. Psychiatry 65, 267–275 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fraguas D et al. Mental disorders of known aetiology and precision medicine in psychiatry: a promising but neglected alliance. Psychol. Med. 47, 193–197 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Riva-Posse P et al. A connectomic approach for subcallosal cingulate deep brain stimulation surgery: prospective targeting in treatment-resistant depression. Mol. Psychiatry 23, 843–849 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Choi KS, Riva-Posse P, Gross RE & Mayberg HS Mapping the “depression switch” during intraoperative testing of subcallosal cingulate deep brain stimulation. JAMA Neurol. 72, 1252–1260 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tharin S & Golby A Functional brain mapping and its applications to neurosurgery. Neurosurgery 60, 185–201 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bishop MP, Elder ST & Heath RG Intracranial self-stimulation in man. Science 140, 394–396 (1963). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rao VR et al. Direct electrical stimulation of lateral orbitofrontal cortex acutely improves mood in individuals with symptoms of depression. Curr. Biol. 28, 3893–3902 e3894 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kirkby LA et al. An amygdala—hippocampus subnetwork that encodes variation in human mood. Cell 175, 1688–1700 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Scangos KW et al. Pilot study of an intracranial electroencephalography biomarker of depressive symptoms in epilepsy. J. Neuropsychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 32, 185–190 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Timmerby N, Andersen JH, Sondergaard S, Ostergaard SD & Bech P A systematic review of the clinimetric properties of the 6-item version of the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D6). Psychother. Psychosom. 86, 141–149 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Inman CS et al. Human amygdala stimulation effects on emotion physiology and emotional experience. Neuropsychologia 145, 106722 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Machado A et al. Functional topography of the ventral striatum and anterior limb of the internal capsule determined by electrical stimulation of awake patients. Clin. Neurophysiol. 120, 1941–1948 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References

- 1.Malone DA Jr., et al. Deep brain stimulation of the ventral capsule/ventral striatum for treatment-resistant depression. Biol Psychiatry 65, 267–275 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rao VR, et al. Direct Electrical Stimulation of Lateral Orbitofrontal Cortex Acutely Improves Mood in Individuals with Symptoms of Depression. Curr Biol 28, 3893–3902 e3894 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kirkby LA, et al. An Amygdala-Hippocampus Subnetwork that Encodes Variation in Human Mood. Cell 175, 1688–1700 e1614 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scangos KW, et al. Pilot Study of An Intracranial Electroencephalography Biomarker of Depressive Symptoms in Epilepsy. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 32, 185–190 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mayberg HS, et al. Deep brain stimulation for treatment-resistant depression. Neuron 45, 651–660 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Riva-Posse P, et al. Defining critical white matter pathways mediating successful subcallosal cingulate deep brain stimulation for treatment-resistant depression. Biol Psychiatry 76, 963–969 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dougherty DD, et al. A Randomized Sham-Controlled Trial of Deep Brain Stimulation of the Ventral Capsule/Ventral Striatum for Chronic Treatment-Resistant Depression. Biol Psychiatry 78, 240–248 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Campbell MC, et al. Mood response to deep brain stimulation of the subthalamic nucleus in Parkinson's disease. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 24, 28–36 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Timmerby N, Andersen JH, Sondergaard S, Ostergaard SD & Bech P A Systematic Review of the Clinimetric Properties of the 6-Item Version of the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D6). Psychother Psychosom 86, 141–149 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Salloum NC, et al. Efficacy of intravenous ketamine treatment in anxious versus nonanxious unipolar treatment-resistant depression. Depress Anxiety 36, 235–243 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mori S & van Zijl PC Fiber tracking: principles and strategies - a technical review. NMR Biomed 15, 468–480 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Feffer K, et al. 1Hz rTMS of the right orbitofrontal cortex for major depression: Safety, tolerability and clinical outcomes. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 28, 109–117 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The source data that support the findings in this report are available in the report itself, in the Supplementary Information and in our publicly available code. Source data are provided with this paper.