Abstract

Human consumption of cannabinoid-containing products during early life or pregnancy is rising. However, information about the molecular mechanisms involved in early life stage Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and cannabidiol (CBD) toxicities is critically lacking. Here, larval zebrafish (Danio rerio) were used to measure THC- and CBD-mediated changes on transcriptome and the roles of cannabinoid receptors (Cnr) 1 and 2 and peroxisome proliferator activator receptor γ (PPARγ) in developmental toxicities. Transcriptomic profiling of 96-h postfertilization (hpf) cnr+/+ embryos exposed (6 − 96 hpf) to 4 μM THC or 0.5 μM CBD showed differential expression of 904 and 1095 genes for THC and CBD, respectively, with 360 in common. Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathways enriched in the THC and CBD datasets included those related to drug, retinol, and steroid metabolism and PPAR signaling. The THC exposure caused increased mortality and deformities (pericardial and yolk sac edemas, reduction in length) in cnr1−/− and cnr2−/− fish compared with cnr+/+ suggesting Cnr receptors are involved in protective pathways. Conversely, the cnr1−/− larvae were more resistant to CBD-induced malformations, mortality, and behavioral alteration implicating Cnr1 in CBD-mediated toxicity. Behavior (decreased distance travelled) was the most sensitive endpoint to THC and CBD exposure. Coexposure to the PPARγ inhibitor GW9662 and CBD in cnr+/+ and cnr2−/− strains caused more adverse outcomes compared with CBD alone, but not in the cnr1−/− fish, suggesting that PPARγ plays a role in CBD metabolism downstream of Cnr1. Collectively, PPARγ, Cnr1, and Cnr2 play important roles in the developmental toxicity of cannabinoids with Cnr1 being the most critical.

Keywords: cannabidiol, tetrahydrocannabinol, PPARγ, RNAseq, development, behavior

Marijuana laws are changing at a rapid pace across the world. As of January 2021, consumer access to cannabis is high, with countries such as Canada, Georgia, South Africa, Uruguay, as well as 15 states, 2 territories, and the District of Columbia in the United States of America (USA) having legalized recreational use. Medicinal cannabis use is legal in 43 countries and almost all states in the USA. Roughly 22%−30% of young adults in the USA between the ages of 18 − 30 admit to using marijuana in the past month (Schulenberg et al., 2020), whereas 11%−36% of teenagers aged 13 − 17 admit using in the last year (Miech et al., 2020). The incidence of cannabis usage in pregnant women (in the first trimester) has more than doubled in the past decade (Volkow et al., 2019). In fact, marijuana use among pregnant women is higher than any other illicit drug (Volkow et al., 2019) and 70% of both pregnant and nonpregnant women believe there is slight or no risk of marijuana use (Ko et al., 2015). Therefore, there is an ongoing need to understand the potential developmental effects of exposure including possible long-term effects of early life exposure (Bobst et al., 2020).

Cannabis contains more than 545 known chemical compounds including the psychoactive Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and nonpsychoactive cannabidiol (CBD) (Gonçalves et al., 2019). The endocannabinoid system, on which cannabinoids interact, consists of 2 cannabinoid receptors 1 and 2 (CB1 and CB2 in humans and rodents, Cnr1 and Cnr2 in fish), 2 endocannabinoids—anandamide and 2-arachidonoylglycerol, and anabolic/catabolic enzymes (Lu and MacKie, 2016). The endocannabinoidome further includes many other overlapping receptor/signaling pathways such as transient receptor potential cation channel subfamily V member 1 (TRPV1), peroxisome proliferator-activated nuclear receptors- (PPARα and PPARγ), T-type Ca2+ channels, and orphan G protein-coupled receptors like GPR18, or GPR55 (Cristino et al., 2020).

In vertebrates (eg, chick, mouse, Xenopus, and zebrafish) the endocannabinoid system is expressed in the central nervous system prior to and during neurodevelopment (Berghuis et al., 2007; Harkany et al., 2007; Krug and Clark, 2015; Lam et al., 2006; Psychoyos et al., 2012; Sufian et al., 2019). Exposure to high doses of THC and CBD during embryonic development causes disrupted brain development and other teratogenic effects in mice and fish (Carty et al., 2018; Fish et al., 2019). Furthermore, perinatal manipulation of the endocannabinoid system by administering cannabinoids or by maternal marijuana consumption alters neurotransmission and behavioral functions in offspring of humans (Fried et al., 2003; Fried and Smith, 2001), mice (De Salas-Quiroga et al., 2015), rats (Fride and Mechoulam, 1996; O’Shea and Mallet, 2005; Rubio et al., 1995), and zebrafish (Ahmed et al., 2018; Carty et al., 2019). Previous research in our laboratory established that high doses of THC (≥4 μM) or CBD (≥0.5 μM) are teratogenic to zebrafish (Carty et al., 2018). Importantly, lower concentrations that did not induce overt morphological effects and were within the human therapeutic range resulted in reproductive abnormalities and gene expression changes that persisted into adulthood and old age (Carty et al., 2019; Pandelides et al., 2020a, 2020b). Furthermore, sublethal concentrations of THC or CBD caused significant larval behavioral alterations (Carty et al., 2019, 2018).

THC is a known agonist of Cnr1 and Cnr2 receptors, whereas CBD acts as an allosteric modulator to these receptors (Laprairie et al., 2015; Martínez-Pinilla et al., 2017; Tham et al., 2019). Due to the expression of Cnr1 and Cnr2 receptors throughout the central nervous system, cannabinoid compounds have the potential to affect neural development. There is evidence from cannabinoid receptor knock out models that Cnr1 and Cnr2 play important roles in mediating behavior, organ development, size, and metabolism (De Azua et al., 2017; Liu et al., 2016; Ravinet Trillou et al., 2004; Schmitz et al., 2016; Varvel et al., 2005). However, the role of Cnr1 and Cnr2 in THC or CBD developmental toxicity has not been fully elucidated.

In the current study, we investigated effects of THC and CBD on the larval zebrafish transcriptome at 96 hpf following developmental exposure to assess the effects of cannabinoids on the whole organism. Resulting pathway analysis informed further investigation into the mechanistic contributions of Cnr1, Cnr2, and PPARγ in THC and CBD early life stage toxicities. We hypothesized that the cannabinoid receptors would play a significant mechanistic role in THC’s, but not CBD’s, acute toxic effects.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Experimental animals

The following strains of zebrafish were used in this study—the Tg(fli1: egfp), cnr1−/− [Tu(cnr1zf679/zf679)] and cnr2−/− [Tu(cnr2zf680/zf680)]. Tg(fli1: egfp) zebrafish were obtained from the Zebrafish International Resource Center (ZFIN, Eugene, Oregon). The cannabinoid receptor mutants (cnr1−/− and cnr2−/−) (Liu et al., 2016) were kindly provided by Dr Wolfram Goessling (Genetics Division, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts 02115). Tg(fli1:egfp) which is cnr+/+ was used as a wildtype control in studies involving cnr1−/− and cnr2−/− mutants. We have used Tg(fli1:egfp) strain to assess the impact of developmental exposure to both THC and CBD (Carty et al., 2018, 2019; Pandelides et al., 2020a, 2020b). Healthy adult zebrafish were maintained in Aquatic Habitats Zebrafish Flow-through System (Aquatic Habitats, Apopka, Florida) under ambient conditions (pH 7.5–8.0, dissolved oxygen 7.2–7.8 mg/l, conductivity 730–770 mS, and temperature 27–29°C). The cnr1−/− and cnr2−/− adults were genotyped prior to conducting the experiments. The primer sequences used for genotyping are provided in Supplementary Table 1. All the experiments and exposure protocols were in accordance with approved Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee guidelines and recommendations.

Embryos for exposure studies were obtained by setting up pairwise breeding of adult fish overnight. The next morning, eggs were collected, debris removed, and randomly sorted into scintillation vials (10 embryos per vial) containing embryo water (6 ml volume, sterilized deionized water; pH 7.4–7.7; 60 ppm Instant Ocean, Cincinnati, Ohio), and maintained at 28°C in an incubator. Exposed embryos were screened daily to assess overall health of the embryos.

Δ9-Tetrahydrocannabinol and CBD exposures

The rationale for the exposure paradigm used in this study included several considerations. Previously, a dosing regimen of 1 − 4 µM THC and 0.25 − 0.5 µM CBD in zebrafish water resulted in the accumulation of 0.28 − 0.71 mg/kg THC and 1.2 − 8.61 mg/kg CBD in the whole larval zebrafish, respectively (Carty et al., 2018, 2019). Because CBD bioconcentrates more than THC in zebrafish, there is higher acute toxicity in CBD-exposed zebrafish and a lower CBD concentration range was used. Representative concentrations used in this study (eg, 4 µM THC [3.75 mg/l] and 0.5 μM CBD [0.15 mg/l]), were lower than the typical 5 mg/kg THC dose used in prenatal and perinatal mice/rats studies (range 0.15 − 150 mg/kg; Grant et al., 2018). Furthermore, a 2.5 mg/kg THC rodent dose has been related to a human exposure from a single joint (approximately 120–220 mg THC) (Leishman et al., 2018; Rubino et al., 2008). Clinically, CBD in Epidiolex is FDA approved for dosing from 2.5 to 10 mg/kg twice daily, with the goal of maintenance dosing of 10 − 20 mg/kg/day (Arzimanoglou et al., 2020). In humans, THC and CBD can cross the placenta. Reported meconium and umbilical cord concentrations for THC were 0.016 and 0.0012 mg/kg, respectively, and 0.33 mg/kg CBD in meconium (Grant et al., 2018; Jensen et al., 2019; Kim et al., 2018), which supports the observation of higher bioconcentration of CBD relative to THC. The exact dose a developing child is exposed to maternally of THC or CBD is unknown. THC is known to be quickly metabolized within 24 h from many tissues and serum, but persists in fat (Brunet et al., 2006).

Based on previous dose response studies conducted in our laboratory (Carty et al., 2018; 2019), 4 μM THC and 0.5 μM CBD were chosen to investigate the effects of exposure on gene expression changes. Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO; final concentration 0.05%) was used as a carrier control. Δ9-Tetrahydrocannabinol and CBD were procured from the NIDA Drug Supply Program (Research Triangle Park, North Carolina). Tg(fli1:egfp) embryos were exposed under static conditions from 6 h postfertilization (hpf) to 96 hpf. Every 24 h, embryos were observed for any developmental defects and mortalities. Any debris (sloughed chorions) were removed from vials during observation. Each treatment consisted of 3 biological replicates with 10 embryos per replicate.

RNA sequencing analysis

RNA sequencing (RNAseq) was conducted on the 3 biological replicates at the University of Mississippi Medical Center (Jackson, Mississippi). Library construction was done using TruSeq Illumina library preparation kit. Paired end 100 bp sequencing was done on an HiSeq2000 Illumina platform. Raw data files were assessed for quality using FastQC (Andrews, 2010) prior to preprocessing. Trimmomatic was used for preprocessing, to remove any remaining adaptor sequences and reads with low-sequence quality (Phred score less than 20). Trimmed sequence reads were mapped to the zebrafish genome using the STAR aligner (Dobin et al., 2016). The number of reads mapped to annotated regions of the genome were obtained using HTSeq-count (Anders et al., 2015). Ensembl version 84 (GRCz10) of the zebrafish genome and annotations were used in this analysis (Yates et al., 2016) and statistical analysis was conducted using edgeR, a Bioconductor package (Robinson et al., 2010). The quasi-likelihood model in edgeR (glmQLFTest) was used to perform differential gene expression analysis. Only genes with false discovery rate (FDR) of less than 5% were considered to be differentially expressed. Annotation of the differentially expressed genes was done using BioMart (Smedley et al., 2015).

Gene ontology classification, KEGG pathway, and human phenotype analysis

Annotated zebrafish genes found to be differentially expressed (FDR < 0.05) were classified based on gene ontology (molecular function) using a gProfiler package g:GOSt (Reimand et al., 2016). The up- and downregulated datasets for each treatment were processed individually. We then compared the GO terms between the 3 treatments using the g:Cocoa, a package of gProfiler (Reimand et al., 2016). We visualized the GO terms using GOView and generated hierarchical DAG (directed acyclic graphs) graphs to highlight relationships between GOterms (child and parent terms) (Wang et al., 2017). Only unique GO terms with a distinct set of genes were considered for further analysis. Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) and Human Phenology (HP) term analysis of the DEGs was done using gProfiler. Genes represented under each enriched KEGG and HP pathway were manually screened, and the pathways with unique lists of genes were selected.

Determining the developmental toxicity to THC and CBD exposure in Cnr mutants

Beginning at 6 hpf, zebrafish embryos from the cnr+/+, cnr1−/−, and cnr2−/− strains were exposed to 5 different concentrations of THC (2, 4, 8, 9.5, and 12 μM or 0.65, 1.25, 2.4, 3, 3.75 mg/l) or CBD (0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, and 4 μM or 0.075, 0.15, 0.3, 0.6, 1.2 mg/l). A 0.05% DMSO (control) group was included as a carrier control. Exposures were continued under static conditions until 96 hpf. Each treatment consisted of 5 biological replicates with 10 embryos per replicate.

Role of PPARγ in THC- and CBD-induced effects

To determine the role of PPARγ in THC- and CBD-induced effects, we exposed cnr+/+, cnr1−/−, and cnr2−/− strains to either a PPARγ antagonist GW9662 (0.5 µM; Jin et al., 2020) alone or in combination with 4 µM THC or 2 µM CBD. A 0.05% DMSO (control) group was included as a carrier control. These embryos were exposed 6 − 96 hpf under static exposure conditions. Each treatment consisted of 5 biological replicates with 10 embryos per replicate.

Quantification of THC and CBD using GC/MS

Δ9-Tetrahydrocannabinol and CBD in exposure medium (embryo water) was measured by GC/MS as described previously (Carty et al., 2018). Briefly, deuterated THC-d3 (Sigma Aldrich, St Louis, Missouri) was added to the samples at 0 h post-treatment along with 2 M sodium hydroxide and extracted using hexane:ethyl acetate (9:1 vol:vol). Samples were then derivatized in N,O-bis(trimethylsilyl)trifluoroacetamide with 1% trimethylchlorosilane (ThermoScientific) at 90°C for 1 h. Samples were then evaporated to dryness, reconstituted in iso-octane, and run on the GC/MS (Agilent Technologies 6890N; Mass Spectrometer 5973) with DB-5MS column (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, California) for analysis in selected ion monitoring mode. Retention times and ions [quantitative; qualitative] for quantifying THC-d3, THC, and CBD were as follows: 8.142 min [374; 389 m/z], 8.167 min [386; 371 m/z], and 6.936 min [390; 458 m/z]. Concentrations were calculated based on a 5-point standard curve (0.0625–1 mg/l). Percent recovery was 87% ± 20% for water samples. Measured water concentrations are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Cannabinoid Exposure Water Concentrations

| Compound | Nominal Water Concentration (mg/l) | Measured Water Concentration (mg/l) |

|---|---|---|

| Control | 0 | ND |

| THC | 0.65 | 0.22 ± 0.004 |

| 1.25 | 0.32 ± 0.007 | |

| 2.5 | 0.50 ± 0.05 | |

| 3 | 0.68 ± 0.01 | |

| 3.75 | 0.77 ± 0.03 | |

| CBD | 0.075 | 0.16 ± 0.006 |

| 0.15 | 0.19 ± 0.008 | |

| 0.3 | 0.24 ± 0.005 | |

| 0.6 | 0.46 ± 0.03 |

Data presented as mean measured concentration ± SD of 3 − 9 replicates for the dose response and PPARγ-antagonist exposures.

Abbreviation: ND, not detected.

Larval behavioral assays

Larval locomotion behavior in response to light was measured following established methods using a ViewPoint ZebraBox (ViewPoint, Montreal, Canada) (Kirla et al., 2016). At the end of the exposure (96 hpf), larvae were transferred into individual wells of a 96-well plate (300 µl embryo water/well) and acclimated for 5 min under ambient light and temperature. Locomotory assay conditions include initial 10 min under 100% light [8000 lux] followed by 10 min in the dark [0% light; 0 lux]; and 10 min in 100% light (Kirla et al., 2016). The total distance travelled during the light and the dark phases was also calculated per larvae. Larvae that were unable to swim due to gross malformation were excluded from the behavior analysis. Behavior was assessed in all fish except those used for RNA sequencing. Each treatment condition consisted of 50 individual larvae.

Morphological phenotypes

After behavioral assessments, photographs were taken of all surviving larval fish (50 larval fish per treatment, 10 per replicate, n = 5 replicates) per treatment group to assess developmental deformities. Larvae were anesthetized in tricaine methanesulfonate (300 mg/l MS-222) buffered with 600 mg/l sodium bicarbonate. They were immediately placed on a microscope slide with a chamber containing 3% methyl cellulose and a lateral image was captured with a MicroFire camera (Optronics, Goleta, California) attached to a Zeiss Stemi 2000-C Stereo Microscope (Jena, Germany) using Picture Frame Application 2.3 software (Optronics). The phenotypes were scored blindly using ImageJ software (Schneider et al., 2012). Total body length, diameter, and area of the eye, presence or absence of developmental abnormalities (yolk sac edema, pericardial edema, spinal curvature, swim bladder inflation failure) were recorded by 3 double-blinded reviewers. Pooled larval zebrafish were placed in RNA later (10 per replicate), frozen and stored at -80°C until further analysis.

RNA isolation, cDNA synthesis, and real time-quantitative PCR

RNA extraction was done using an RNeasy mini-kit (Qiagen, California) in conjunction with gDNA removal via RNase-Free DNase set (Qiagen) following the manufacturer’s recommended protocol. RNA was quantified and evaluated for purity (260/280 ratio = 1.9 − 2.1) on a NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer (ThermoFisher, Massachusetts). RNA (250 ng) was then reverse transcribed to cDNA following the manufacture’s protocol (Invitrogen, California). The RT-qPCR was performed on PPARγ (pparγ), PPARα (pparαa), and 18S ribosomal RNA (reference gene), using an Applied Biosystems 7500 real-time cycler with SYBR Green detection chemistry (Applied Biosystems, California) following the manufacture’s protocol in a 25 µl reaction volume. Parameters for RT-qPCR were as follows: 95°C for 10 min, then 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 s and 60°C for 1 min, followed by 95°C for 15 s−60°C for 1 min−95°C for 15 s dissociation curve. Primers were optimized as described previously (Corrales et al., 2014) and primer sequences are provided in Supplementary Table 1. Samples were run in duplicate followed by 2-ΔΔCT method evaluation (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001).

Statistical analysis

All data were assessed for normality and homogeneity of variance using Shapiro-Wilk and Brown-Forsythe tests, respectively. The incidence of developmental deformities (%) was calculated per biological replicate (n = 5). Larval length, eye diameter, and eye area was recorded per fish and then averaged per replicate (n = 5). The differences in strain were assessed by comparing the 3 unexposed solvent controls (1-way analysis of variance [ANOVA], Tukey’s posthoc test, p ≤ .05) in order to make all pairwise comparisons between the 3 strains. Differences in treatment within each strain were assessed by ANOVA, Dunnett’s posthoc (p ≤ .05), in order to assess the difference between treated and the untreated control fish.

RT-qPCR was assessed using (ANOVA) on the ΔCT followed by Dunnett’s posthoc test compared with the solvent controls (p ≤ .05). The gene expression data were summarized in tables displaying the average log(2)ΔΔCt ± standard error of the mean. The differences in strain were assessed by comparing the ΔCt of the 3 unexposed solvent controls (ANOVA, Tukey’s posthoc, p ≤ .05).

Statistical analysis was conducted on the total distance travelled during the light and dark phases separately. First, the 3 DMSO controls were compared to assess the difference between the strains (ANOVA on ranks, Tukey’s posthoc, p ≤ .05). Next within each strain differences in concentration were assessed (ANOVA on ranks, Dunn’s posthoc, p ≤ .05). All graphing and statistical analyses were conducted using Sigmaplot 14.0 software.

RESULTS

Δ9-Tetrahydrocannabinol- and CBD-Induced Transcriptional Responses

Transcriptomic analysis revealed differential expression of 904 and 1095 genes in the THC- and CBD-exposed groups, respectively, in comparison to the DMSO control (5% FDR). Among the 904 DEGs in response to THC, 744 genes were upregulated, and 160 genes were downregulated. Whereas with CBD, 774 genes were upregulated, and 321 genes were downregulated. Comparison of these 2 datasets revealed a total of 360 genes were differentially expressed in common in response to both THC and CBD. The entire list of differentially expressed genes as well as shared genes and their fold changes is provided in Supplementary Data (THC_CBD_DEGs.xlsx). Raw files have been deposited in the GEO database (accession number GSE164128).

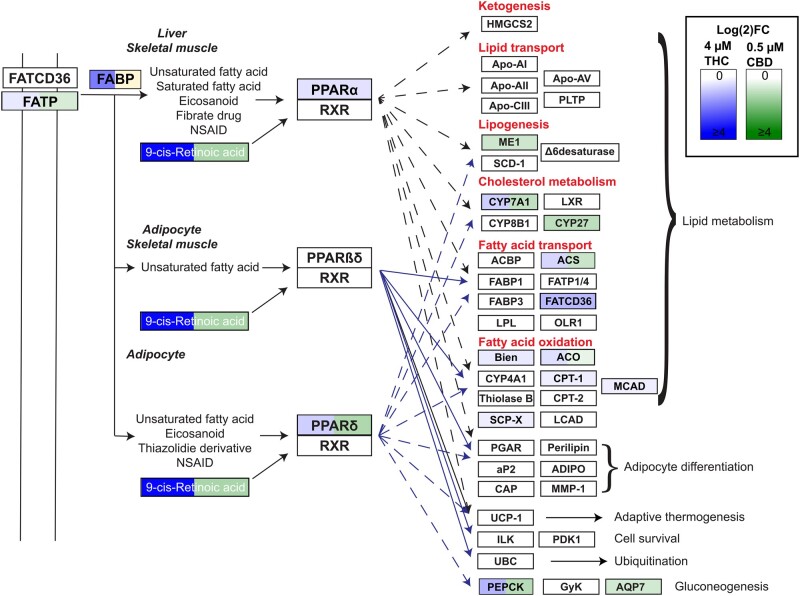

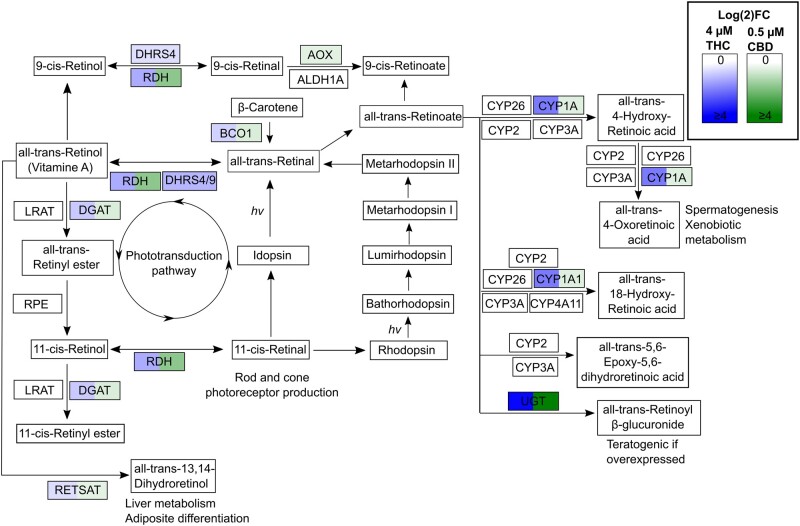

The KEGG pathways enriched in the THC dataset included drug metabolism, metabolic pathways (glutathione, tyrosine, arachidonic acid, glycine, serine, and threonine metabolism), steroid hormone biosynthesis, retinol metabolism, and PPAR signaling. Some of the same KEGG pathways enriched in CBD dataset were PPAR signaling, steroid hormone biosynthesis, metabolic pathways, and retinol metabolism. The differentially expressed genes associated with the PPAR signaling pathway and retinol metabolism are shown in Figure 1 and 2, respectively. The human phenology term analysis revealed enrichment of complement deficiency in both THC and CBD datasets. The detailed list of enriched KEGG and human phenology pathways is shown in Table 2.

Figure 1.

Δ9-Tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and cannabidiol (CBD) altered PPARα,γ associated pathways. PPARs are known to dimerize with RXR and their roles in metabolism are well established. Significant upregulation (FDR ≤ 0.05) of genes within this KEGG signaling pathway are highlighted in gradients of blue (THC), green (CBD), or both blue and green (both THC and CBD). Note that 1 gene in the data (FABP, logFC = −0.61, yellow) set was significantly downregulated for CBD.

Figure 2.

Δ9-Tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and cannabidiol (CBD) altered retinol metabolism pathway. The retinol pathway plays an important role in important physiological functions including photoreceptor development, metabolism, etc. The KEGG retinol signaling pathway with genes significantly upregulated (FDR ≤ 0.05) in our data set are highlighted in gradients of blue (THC), green (CBD), or both blue and green (both THC and CBD). No genes were significantly downregulated in this pathway.

Table 2.

Top HP, GO, and KEGG Pathway Analysis Terms Enriched in the Differentially Expressed Genes in Zebrafish Developmentally Exposed to 4 μM THC or 0.5 μM CBD

| 4 μM THC |

0.5 μM CBD |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. DEG | p-Value | No. DEG | p-value | ||

| GO ID | GO Pathway | ||||

| GO:0016491 | Oxidoreductase activity | 91 | 9.29E−21 | 67 | 1.76E−05 |

| GO:0046906 | Tetrapyrrole binding | 28 | 5.39E−09 | 28 | 2.19E−07 |

| GO:0061134 | Peptidase activity | 60 | 7.15E−08 | 58 | 1.71E−04 |

| GO:0016787 | Hydrolase activity | 140 | 3.86E−05 | N/A | |

| GO:0016936 | Galactoside binding | 5 | 5.07E−04 | N/A | |

| GO:0004497 | Monooxygenase activity | N/A | 27 | 4.16E−08 | |

| HP ID | HP pathway | ||||

| HP:0004431 | Complement deficiency | 11 | 1.48E−05 | 13 | 5.19E−07 |

| HP:0001937 | Microangiopathic hemolytic anemia | 7 | 1.92E−03 | 8 | 3.86E−04 |

| HP:0011036 | Abnormality of renal excretion | N/A | 14 | 5.88E−03 | |

| HP:0005575 | Hemolytic-uremic syndrome | 7 | 1.92E−03 | 7 | 7.03E−03 |

| HP:0001919 | Acute kidney injury | N/A | 9 | 1.55E−02 | |

| KEGG ID | KEGG pathway | ||||

| KEGG:00980 | Metabolism of xenobiotics by CYP450 | 19 | 6.34E−12 | N/A | |

| KEGG:00983 | Drug metabolism—other enzymes | 21 | 7.97E−11 | N/A | |

| KEGG:00830 | Retinol metabolism | 18 | 1.44E−09 | 10 | 3.74E−02 |

| KEGG:01100 | Metabolic pathways | 106 | 3.36E−09 | 95 | 2.59E−02 |

| KEGG:00140 | Steroid hormone biosynthesis | 16 | 1.18E−08 | 10 | 1.09E−02 |

| KEGG:03320 | PPAR signaling pathway | 13 | 2.62E−03 | 13 | 1.23E−02 |

Each treatment consisted of 3 biological replicates with 10 embryos per replicate. No. DEG. = N/A.

Role of Cnr1 and Cnr2 in THC- and CBD-Induced Developmental Toxicity

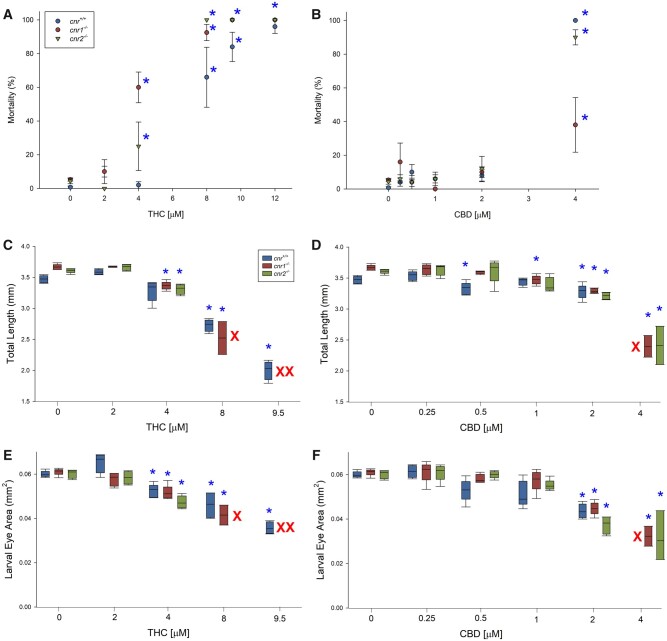

There was a dose-dependent effect of THC exposure on mortality in all 3 strains of fish (cnr+/+, cnr1−/−, and cnr2−/−). In controls (cnr+/+), 60% mortality was observed with 8 μM THC (Figure 3A). In contrast, cnr1 and cnr2 null mutants were more sensitive to THC exposure and had significant mortality at 4 µM THC. Similarly, increased sensitivity to THC in the cnr1 and cnr2 null mutants was observed for developmental deformities (pericardial and yolk sac edemas, Supplementary Figure 1). Constitutive differences between the 3 strains are shown in Supplementary Figure 2.

Figure 3.

Mortality (%), total length (mm), and larval eye area (mm2) of 96 hpf larval zebrafish developmentally exposed to Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (A, C, E) or cannabidiol (B, D, F) presented as box and whisker plots (n = 5). Asterisk indicates a significant difference compared with the within-strain solvent control (ANOVA, Dunnett’s posthoc, p ≤ .05). Red X’s indicate concentration/strains with no survival.

Developmental exposure to CBD did not show a dose-dependent effect on mortality in any of the 3 strains up to 2 µM CBD (Fig. 3B). However, at the highest concentration of CBD (4 µM), 90%−100% of the cnr+/+ and cnr2−/− larvae and 40% of the cnr1−/− larvae died. The cnr1 and cnr2 null mutants were less sensitive than cnr+/+ for developmental edemas (Supplementary Figure 1).

Exposure to THC and CBD caused a dose-dependent reduction in the total length in all 3 strains compared with the unexposed groups (Figs. 3C and D). In addition, exposure to both THC and CBD resulted in dose-dependent reduction in the eye area of larval fish in all 3 strains (Figs. 3E and F).

Role of cnr1 and cnr2 Receptors in THC- and CBD-Induced Behavioral Deficits

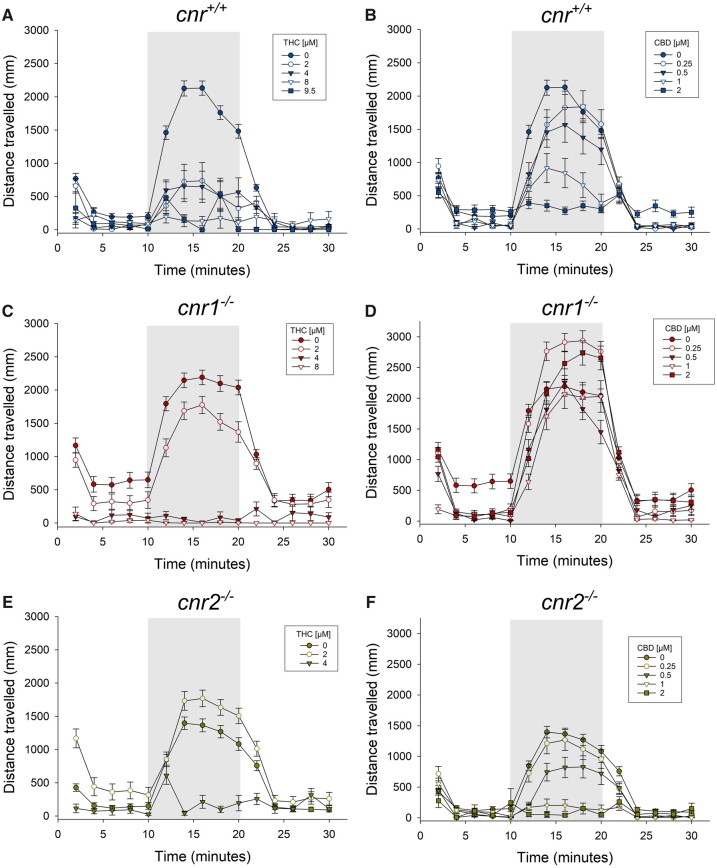

In cnr+/+ fish, THC exposure significantly decreased larval locomotor activity particularly in the dark phase when compared with the vehicle control similar to previous in laboratory studies (Carty et al., 2019, 2018) (Figure 4A; Supplementary Figs. 3A−C). Similarly, CBD exposure significantly reduced larval locomotion in the cnr+/+ strain (Figure 4B; Supplementary Figs. 4A−C).

Figure 4.

Total distance travelled (mean ± SE, n = 50) over the 30 min during the light:dark: Light test of the cnr+/+, cnr1−/−, and cnr2−/− strains of zebrafish used in this study exposed to THC (A, C, E) or CBD (B, D, F).

In cnr1−/− mutants, THC exposure at all concentrations significantly decreased larval locomotor activity in the dark phase (Figure 4C; Supplementary Figs. 3D−F). CBD caused a significant reduction in cnr1−/− larval locomotion during both light and dark phases, but effects were not dose-dependent (Figure 4D; Supplementary Figs. 4D−F). All concentrations of THC and CBD (except for 0.25 µM CBD) exposure decreased larval locomotory activity in the dark phase in cnr2−/− mutants (Figs. 4E and F; Supplementary Figs. 3 and 4G−I).

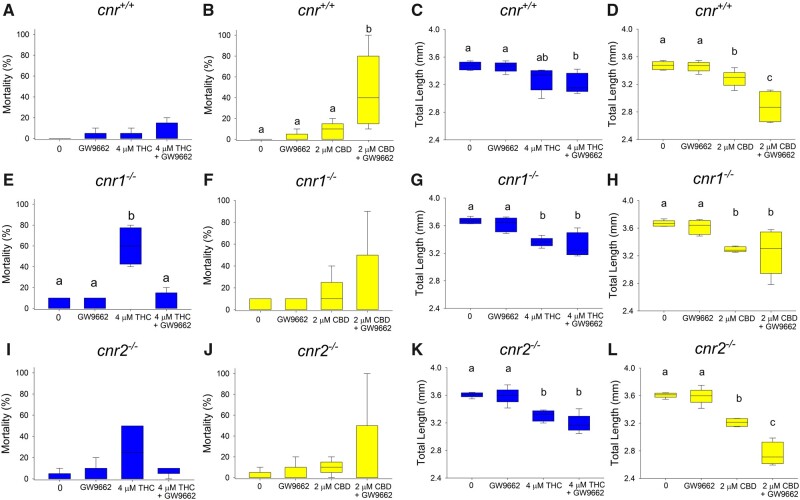

Role of PPARγ in THC- and CBD-Exposure Induced Effects

RNAseq results revealed that PPARγ was a significant upstream regulator of many of the differentially expressed genes. In order to elucidate the role PPARγ in the adverse outcomes associated with cannabinoid exposure, all 3 strains of fish embryos were exposed to either 4 µM THC or 2 µM CBD alone or in combination with the PPARγ antagonist (GW9662, 0.5 µM; Jin et al., 2020). Larval exposure to 0.5 µM GW9662 alone did not cause any significant effects on any endpoints measured with the exception of larval locomotion in cnr1−/− mutants. However, a mixture of CBD and the PPAR antagonist caused significantly reduced survival in the cnr+/+ strain compared with CBD alone. Although the opposite effect (increased survival) was observed in THC+GW9662 mixture for cnr1−/− fish and no significant change found in the cnr2−/− strain (Figs. 5A−J). Δ9-Tetrahydrocannabinol and CBD either alone or in combination with PPARγ antagonist significantly reduced the total length of the fish in all 3 strains of fish (Figs. 5C−L). Significantly worse outcomes were observed in cnr+/+ and cnr2−/− mutants, where the PPARγ antagonist in combination with CBD significantly decreased the total length of larvae in comparison to CBD alone. Although exposure to the PPARγ inhibitor alone did not cause any significant increase in the incidence of yolk sac or pericardial edema, cotreatment with THC or CBD generally caused a significant increase in the incidence of malformations (pericardial and yolk sac edemas) in all 3 strains of fish, which was significantly higher than THC or CBD alone in the cnr+/+ and cnr2−/− strains (except for pericardial edema in THC treated cnr2−/− fish) (Supplementary Figs. 5 and 6). There was no significant mixture effect for larval eye area (Supplementary Figure 7) and larval locomotor activity (Supplementary Figs. 8 and 9) in any of the 3 fish strains.

Figure 5.

Survival (%, A:J) and total length (mm, C:L) of 96 hpf larval zebrafish developmentally exposed to THC, CBD, GW9662 (PPARγ antagonist) or a mixture (n = 5). Different letters indicate a significant difference between groups (ANOVA, Tukey’s posthoc, p ≤ .05).

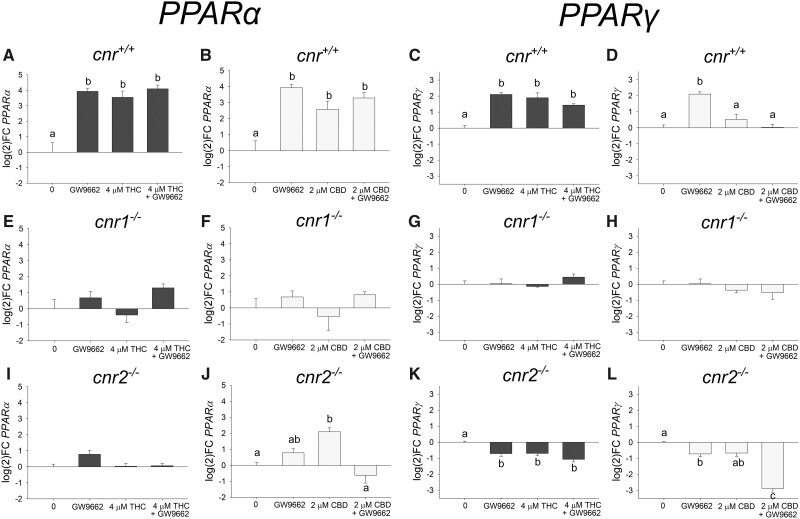

The Effect of THC, CBD, and/or a PPARγ Antagonist Exposure on PPARα and PPARγ Expression

Exposure to all treatments resulted in significant upregulation of PPARα in the cnr+/+ fish (Figure 6). There was no significant effect on PPARα expression in the cnr1−/− fish, but in the cnr2−/− fish exposure to 2 µM CBD caused significant upregulation of PPARα. Furthermore, in the cnr2−/− fish exposure to GW9662 alone or in combination with THC or CBD did not significantly affect PPARα expression.

Figure 6.

Expression log(2)fold change of PPARα (A:J) and PPARγ (C:L) of 96 hpf larval zebrafish developmentally exposed (6 − 96 hpf) to THC, CBD, GW9662 (PPARγ antagonist), or a mixture (n = 3 − 5). Different letters indicate a significant difference between groups (ANOVA, Tukey’s posthoc, p ≤ .05).

Exposure to 4 µM THC, GW9662 (a PPARγ inhibitor), and a combination of both resulted in a significant upregulation of PPARγ expression measured at 96 hpf in the cnr+/+ fish (Figure 6). In contrast, the cnr1−/− fish did not differentially express PPARγ following THC or GW9662 exposure, and the cnr2−/− fish exhibited significant downregulation of PPARγ following THC or GW9662 exposure. The cnr+/+ fish exposed to CBD alone or in combination with GW9662 did not significantly affect PPARγ. Unlike the cnr+/+ fish, both GW9662 and the mixture of 2 µM CBD + GW9662 in the cnr2−/− resulted in significant downregulation of PPARγ. Both of the unexposed control cnr null strains had significantly higher relative expression of PPARα and PPARγ than the unexposed control cnr+/+ when comparing expression (Supplementary Figure 10).

DISCUSSION

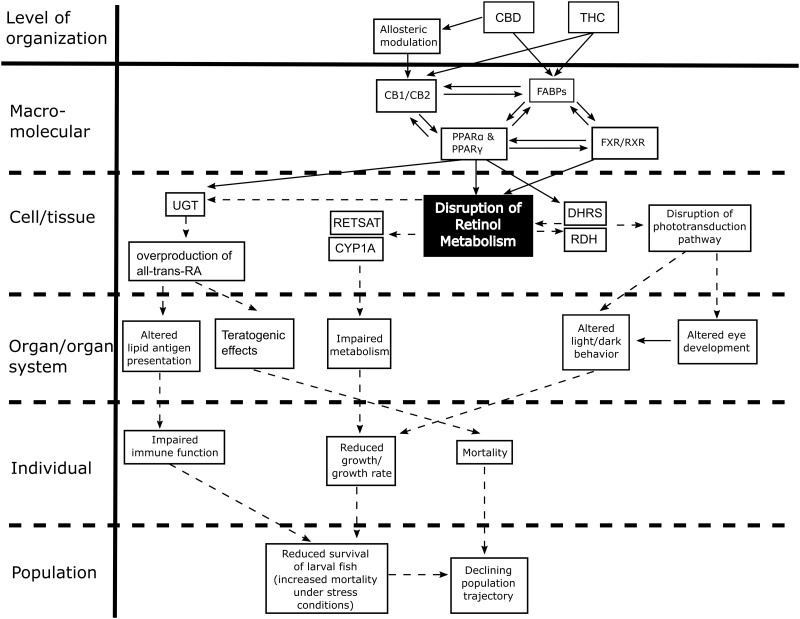

This study found that developmental exposure to THC or CBD in zebrafish results in significant effects on the transcriptome, larval behavior, and developmental abnormalities, consistent with previous studies. Furthermore, THC and CBD effects were ameliorated in cnr mutants, and by a PPARγ antagonist, suggesting these receptors play distinct roles in modulating the developmental effects of cannabinoid exposure. Collectively, these data demonstrate that exposure to THC or CBD during development causes significant adverse outcomes at both the cellular and organismal level. Based on the molecular changes observed in this study, we have proposed an adverse outcome pathway framework for THC and CBD developmental toxicity, beginning with receptor binding to Cnr1, Cnr2, and/or PPARs, in turn altering metabolic pathways (eg, retinol), and resulting in adverse developmental and behavioral outcomes (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Proposed potential adverse outcome pathway for cannabinoid developmental toxicity focused on retinol metabolism and downstream adverse outcomes. Solid lines with arrows indicate known links, whereas dashed lines with arrows represent proposed adverse outcome pathways.

To our knowledge, this is the first study describing the transcriptional responses to THC and CBD exposure in a developing vertebrate. One of the predominant groups of differentially expressed genes were those related to diverse metabolic pathways, including cytochrome P450 genes involved in the breakdown of THC and CBD and genes associated with energy metabolism. These results are not surprising given the fact that developing zebrafish are metabolically active and metabolize a wide range of xenobiotic compounds. Both THC and CBD serve as substrates for cytochrome P450s, particularly CYP3A4 and CYP2C9, significant contributors of THC and CBD metabolism (Hryhorowicz et al., 2018). Our analysis revealed upregulation of a number of cyp2 (cyp2c9, 2aa12, 2p6, 2p7, 2p8, 2k6, 2k16, 2k18, 2k19, 2x9, 2x10.2, 2ad6, 2ad3, 2aa7, 2aa12, 2y3) and two cyp3 family member (cyp3c1 and cyp3c4) genes. Due to genome duplication, zebrafish have a total of 94 CYP genes, distributed among 18 gene families found also in mammals (Goldstone et al., 2010). The relationship between human and zebrafish cyp2 and cyp3 gene families is more complex, with more than 1 ortholog to each human gene. Irrespective of the complexity, upregulation of numerous cyp2 and cyp3 family members suggests that THC and CBD are metabolized in zebrafish embryos.

Another group of metabolic genes differentially expressed in response to cannabinoid exposure included those associated with energy metabolism. The majority of these genes were upregulated in response to THC and CBD exposure, supporting well-established effects on energy homeostasis (Kunos et al., 2008). One previous study (Liu et al., 2016) showed that deletion of cannabinoid receptor in zebrafish leads to liver abnormalities, including delayed development, suggesting that the role of cannabinoids on energy metabolism are evolutionarily conserved. We also observed decreased growth (standard length) in the larvae at the end of the exposure period as well as decreased locomotory behavior, suggesting that effects on metabolic gene expression could lead to phenotypic changes. Furthermore, we have previously shown that this decrease in size due to developmental THC or CBD exposure persists into old age (2.5 years) for female zebrafish (Pandelides et al., 2020a, 2020b). Together, these data suggest that metabolic disruption due to developmental THC or CBD exposure can result in long-term changes in growth.

A key group of transcriptional factors involved in energy homeostasis is peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs). Our results showed enrichment of genes associated with PPAR signaling including differential expression of several lipid and carbohydrate metabolism genes. All 3 PPAR subtypes are ubiquitously expressed during zebrafish development (Den Broeder et al., 2015) and their roles in development, adipocyte differentiation, neurodevelopment, and immune response are well established (Tyagi et al., 2011). We observed upregulation of PPARα and PPARγ gene expression in response to THC and CBD exposure and differential expression of a number of downstream pathways.

There are multiple lines of evidence for THC and CBD interaction with PPARs including binding studies (Granja et al., 2012) and increased transcriptional activity measured following exposure to THC or CBD (Hegde et al., 2015; O’Sullivan et al., 2009, 2005; Takeda et al., 2014). Two hypotheses associated with cannabinoid/PPAR interactions (O’Sullivan, 2016) suggest that cannabinoids bind directly to PPARs and/or activation at the cell surface of cannabinoid receptors initiates intracellular signaling cascades that lead to the activation of PPARs indirectly.

Both THC and CBD are actively transported intracellularly by fatty acid binding proteins (FABPs) and this may be how they are transported into the nucleus (Elmes et al., 2015). It is likely that FABPs direct cannabinoids either to FAAHs for enzymatic degradation, or to the nucleus for PPAR activation; but it is not yet known what is driving one pathway over another. Further, alteration of FABPs may drive increased gene expression of PPARα and γ (Wolfrum et al., 2001). We observed significant upregulation of fabp7a and fabp11a/fabp4 in only the CBD-treated fish (RNAseq data), suggesting CBD dysregulates FABPs. Increased adverse outcomes were observed in the mixture of CBD and the PPAR antagonist for both cnr+/+ and cnr2−/− strains. Thus, PPARγ may play a role in the metabolism of CBD, counteracting some of the toxic effects at higher doses, but this needs further investigation.

Both cnr null strains had significantly higher expression of PPARγ than cnr+/+ when comparing the expression of the unexposed controls, suggesting both Cnr1 and Cnr2 regulate endogenous PPAR expression. Further, the effects of THC or CBD on transcription of PPARs was not blocked by PPARγ antagonism. Additionally, the effect of exposure to THC or CBD on PPAR expression was either muted in the cnr1−/− fish or downregulated in the cnr2−/−. It should be noted that whereas the concentration of THC or CBD did not cause significant toxicity in the cnr+/+ fish, these concentrations did cause toxicity to the Cnr1 and Cnr2 knock out strains, which could have impacted their expression of PPARα and γ. Collectively, the results on PPARα and γ expression of our 3 strains suggest that Cnr1 and Cnr2 act upstream of the action of THC or CBD on PPARs.

PPARs play an important role in a number of pathways, dysregulation of these receptors by agonists/antagonists can lead to several adverse outcomes, including pulmonary fibrosis, edema, renal effects, liver and gall bladder disease, disruption of glucose metabolism, and changes in weight (Bortolini et al., 2013; Brunmeir and Xu, 2018; Jeong et al., 2019). In previous studies, THC caused time and PPARγ-dependent vasorelaxation in rat isolated arteries (O’Sullivan et al., 2009, 2005). It is possible that when PPARγ was blocked in the Cnr+/+ and Cnr2−/− cotreated with THC or CBD, the increased adverse outcomes such as pericardial edema were caused by PPARγ-dependent cardiovascular effects.

The PPARs also heterodimerize with other nuclear receptors such as retinoid X receptor (RXR) (Dawson and Xia, 2012; Qi et al., 2000). Retinoids such as retinal, retinaldehyde, and apo14 modulate RXR and PPAR both in vitro and in vivo (Ziouzenkova et al., 2007a, 2007b; Ziouzenkova and Plutzky, 2008). We observed significant upregulation of genes involved in retinol metabolism, including rdh12l, rdh20, retsat, dhrs4, dhrs9, bco1, dgat1a suggesting that PPAR-RXR crosstalk is affected. The PPARγ activates retinoic acid synthesis by inducing the expression of retinol metabolizing enzymes, including retinol dehydrogenase 10, DHRS9, and retinal metabolizing enzymes such as retinaldehyde dehydrogenase type 2 (RALDH2) in dendritic cells (Szatmari et al., 2006). The PPARα-deficient mice exhibit disturbed retinoic acid homeostasis, with significantly reduced and increased expression of dhrs4 and raldh2, respectively (Lin et al., 2017). In the current study, we observed significant upregulation of both pparα and pparγ, which could contribute to the disruption of retinol metabolism. Retinol is critical for both eye development and photoreception in vertebrate species (Luo et al., 2006), including zebrafish (Marsh-Armstrong et al., 1994). Our observations of eye size differences in THC- and CBD-exposed fish supports that disruption of retinol metabolism during development could be responsible for morphological defects.

In addition, we observed differential expression of genes associated with immune response particularly the complement system, a key innate immune response pathway. These effects were expected because both THC and CBD have well established anti-inflammatory properties (Hegde et al., 2008; Klein et al., 1998; Malfait et al., 2000; Nagarkatti et al., 2009; Stančić et al., 2015). We have previously shown that developmental exposure to THC or CBD caused a significant reduction in the expression of many anti-inflammatory genes such as tnfα, il-6, and il-1b (Pandelides et al., 2020a, 2020b). The anti-inflammatory properties of cannabinoids, such as THC, are mediated in part by cannabinoid receptors as well as other receptors including PPARα and γ (O’Sullivan, 2016). Together, these data suggest that immune changes caused by developmental THC or CBD exposure have the potential to have long-term consequences.

It is well established that THC and CBD effects are mediated in part by CNRs (Cristino et al., 2020). The cnr1−/− and cnr2−/− strains in the current study exhibited significantly increased mortality and developmental abnormalities following THC exposure consistent with the fact that cnr1 and cnr2 null mutants have disrupted liver development and metabolic function (Liu et al., 2016). Even before the liver is completely developed, zebrafish are capable of metabolic activity and metabolizing compounds such as caffeine or diclofenac as early as 25 − 50 hpf (Nawaji et al., 2020). The diclofenac metabolites produced by the embryonic zebrafish in Nawaji et al. (2020) study are metabolized by CYP3A4 and CYP2C9 in humans, which as discussed above are important isozymes for THC and CBD metabolism. Consequently, impaired liver metabolism and clearance of THC and its active metabolites could contribute to the increased toxicity detected in the THC exposed knockout strains.

In contrast, CBD exposure did not have a pronounced effect in cnr1−/− and cnr2−/− mutants. Only the highest concentration of CBD caused significant mortality and affected growth reflecting the likelihood of different mechanisms of action between the cannabinoids. For example, THC has high affinity to Cnr1 (Ki = 5.05–80.3 nM) and Cnr2 (Ki = 3.13–75.3 nM), whereas CBD’s is much lower (Cnr1 Ki = 4350–27 500 nM and Cnr2 Ki = 2400 to >10 000 nM). Cannabidiol is also a weak Cnr1 antagonist (IC50 = 3350 nM) and Cnr2 inverse agonist (IC50 = 27 500 nM) (Howlett et al., 2002; Pertwee, 2008). Further, CBD acts as a negative allosteric modulator for Cnr1 and Cnr2 at concentrations well below its reported Ki values, so it is possible that some of CBD’s effects are still mediated through these 2 receptors (Laprairie et al., 2015; Martínez-Pinilla et al., 2017; Tham et al., 2019). Further, the actions of CBD could be mediated through direct agonism with other receptors like PPARγ (Esposito et al., 2011; O’Sullivan and Kendall, 2010), 5-hydroxytryptamine (serotonin) 1A (5-HT1A) receptors (Sales et al., 2018; Zanelati et al., 2010), and transient receptor potential cation channel subfamily V member 1 (TRPV1) (De Petrocellis et al., 2011).

Exposure to cannabinoids significantly impacts behavior in animal models, generally causing a reduction in motor activity as well as decreased anxiety-like symptoms (Carty et al., 2019; Hasumi et al., 2020; Hložek et al., 2017; Luchtenburg et al., 2019; Martin et al., 1991; Sufian et al., 2019; Varvel et al., 2005). In zebrafish, the endocannabinoid system is critical to the development of the locomotor system (Luchtenburg et al., 2019; Sufian et al., 2019). Behavior was the most sensitive endpoint tested in this study, with significant effects observed at all concentrations tested in the cnr+/+ strain except for the lowest CBD concentration. Exposure to THC or CBD generally caused reduced activity in a dose-dependent manner. It should be noted that the effects of cannabinoids on behavior can be biphasic with increased activity at low doses (lower than used in the present study) and decreased activity at higher doses (Viveros et al., 2005). As expected, the cnr1−/− fish were more tolerant to THC exposure than the other 2 strains because CB1 receptor normally mediates many of the behavioral effects of THC (Varvel et al., 2005). In addition to the Cnr1 and Cnr2 receptors, other endocannabinoid receptors could influence the effects of THC or CBD on behavior. Behavior especially in the context of development is a complex endpoint mediated by signaling across multiple cell types. For example, both proper eye development and photoreception is critical for zebrafish to respond to light: dark stimuli. It is possible that cannabinoid activation of other receptors such as TRPV1 could modulate retinal output as they are expressed in retinal ganglion and microglial cells (Ryskamp et al., 2014). Another important gene that is part of the endocannabinoid pathway and mediates stress response in zebrafish is faah2a (Krug et al., 2018). This gene is absent from rodents but is present in humans and fish (Wei et al., 2006). We measured significant upregulation of faah2a in the THC- or CBD-exposed fish (RNAseq data). Disruption of this enzyme could cause a disruption in endocannabinoid levels, ultimately resulting in behavioral effects.

The endocannabinoid signaling system is critical during early development and alterations of it by cannabinoids are of concern. Understanding the relative risk of maternal or early life stage exposure to THC or CBD is essential. Developmental exposure to THC (2 − 12 μM) or CBD (0.25 − 4 μM) resulted in severe consequences for the development and gene expression of zebrafish embryos and larvae. Transcriptional responses observed in this study suggest that exposure to cannabinoids affects diverse physiological pathways ranging from metabolism to immune responses. Furthermore, retinol metabolism and PPAR signaling were significantly enriched following exposure to THC or CBD which could contribute to the developmental and behavioral abnormalities detected. We propose an AOP framework for THC and CBD developmental toxicity, beginning with receptor binding to Cnr1, Cnr2, and/or PPARs leading to alterations in metabolism and ultimately adverse outcomes at the organismal level (Figure 7). Specifically, THC exposure caused increased mortality and deformities (pericardial and yolk sac edemas, reduction in size) in cnr1−/− and cnr2−/− fish compared with cnr+/+ suggesting Cnr receptors are involved in protective pathways. Conversely, the cnr1−/− larvae were more resistant to CBD-induced malformations, mortality, and behavioral alteration implicating Cnr1 in CBD-mediated toxicity. Behavior was the most sensitive endpoint to THC and CBD exposure with dose-dependent decreased larval distance travelled (96 hpf) at all concentrations tested in the cnr+/+ fish (except 0.25 µM CBD). Differences in strain expression levels suggest that PPARγ is regulated by Cnr1 and Cnr2. Further, blocking PPARγ in addition to THC or CBD exposure resulted in an increase in developmental toxicity for the cnr+/+ and cnr2−/− strains, but not the cnr1−/− strain, suggesting PPARγ plays an important protective role in THC/CBD metabolism. Collectively, these results indicate that PPARγ, Cnr1, and Cnr2 all play important roles in the developmental toxicity of THC and CBD with Cnr1 being the most critical.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary data are available at Toxicological Sciences online.

DECLARATION OF CONFLICTING INTERESTS

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank Dr Michael Garrett and his research group at the University of Mississippi Medical Center (UMMC) Molecular and Genomics Facility for performing RNA extraction and the RNAseq analysis. We would also like to thank Dennis R. Carty and Zachary S. Miller for conducting the initial exposure for RNAseq, as well as Bailey Westling, Mary-Beth Gillespie, and Kennedy E. Dickson for their help during sampling. Finally, we would like to thank Dr Wolfram Goessling (Genetics Division, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts 02115, USA) for kindly providing the cannabinoid receptor mutants (cnr1−/− and cnr2−/−) used in this study.

FUNDING

This work was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse R21DA044473-01, and Centers of Biomedical Research Excellence - National Institute of General Medical Sciences (COBRE-NIGMS P20GM104932). The work performed through the University of Mississippi Medical Center (UMMC) Molecular and Genomics Facility is supported, in part, by funds from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS), including Mississippi IDeA Networks of Biomedical Research Excellence (INBRE) (P20GM103476), Center for Psychiatric Neuroscience (CPN)-COBRE (P30GM103328), Obesity, Cardiorenal and Metabolic Diseases- COBRE (P20GM104357), and Mississippi Center of Excellence in Perinatal Research (MS-CEPR)-COBRE (P20GM121334). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

REFERENCES

- Ahmed K. T., Amin M. R., Shah P., Ali D. W. (2018). Motor neuron development in zebrafish is altered by brief (5-hr) exposures to THC (Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol) or CBD (cannabidiol) during gastrulation. Sci. Rep. 8, 1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anders S., Pyl P. T., Huber W. (2015). HTSeq-A Python framework to work with high-throughput sequencing data. Bioinformatics 31, 166–169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews S. (2010). A Quality Control Tool for High Throughput Sequence Data. Available at: http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc. Last accessed: 4/28/2021.

- Arzimanoglou A., Brandl U., Cross J. H., Gil-nagel A., Lagae L., Landmark C. J., Specchio N., Nabbout R., Thiele E. A., Gubbay O. (2020). Epilepsy and cannabidiol: A guide to treatment. Epileptic Disord. 22, 1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berghuis P., Rajnicek A. M., Morozov Y. M., Ross R. A., Mulder J., Urban G. M., Monory K., Marsicano G., Matteoli M., Canty A., et al. (2007). Hardwiring the brain: Endocannabinoids shape neuronal connectivity. Science 316, 1212–1216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bobst S., Ryan K., Plunkett L. M., Willett K. L. (2020). ToxPoint: Toxicology studies on Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol and cannabidiol-containing products available to consumers are lacking. Toxicol. Sci. 178, 1–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bortolini M., Wright M. B., Bopst M., Balas B. (2013). Examining the safety of PPAR agonists - Current trends and future prospects. Expert Opin. Drug Saf. 12, 65–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunmeir R., Xu F. (2018). Functional regulation of PPARs through post-translational modifications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 19, 1738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunet B., Doucet C., Venisse N., Hauet T., Hébrard W., Papet Y., Mauco G., Mura P. (2006). Validation of large white pig as an animal model for the study of cannabinoids metabolism: Application to the study of THC distribution in tissues. Forensic Sci. Int. 161, 169–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carty D. R., Miller Z. S., Thornton C., Pandelides Z., Kutchma M. L., Willett K. L. (2019). Multigenerational consequences of early-life cannabinoid exposure in zebrafish. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 364, 133–143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carty D. R., Thornton C., Gledhill J. H., Willett K. L. (2018). Developmental effects of cannabidiol and Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol in zebrafish. Toxicol. Sci. 162, 137–145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrales J., Fang X., Thornton C., Mei W., Barbazuk W. B., Duke M., Scheffler B. E., Willett K. L. (2014). Effects on specific promoter DNA methylation in zebrafish embryos and larvae following benzo[a]pyrene exposure. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. C. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 163, 37–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cristino L., Bisogno T., Di Marzo V. (2020). Cannabinoids and the expanded endocannabinoid system in neurological disorders. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 16, 9–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson M. I., Xia Z. (2012). The retinoid X receptors and their ligands. Biochim. Biophys. Acta - Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 1821, 21–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Azua I. R., Mancini G., Srivastava R. K., Rey A. A., Cardinal P., Tedesco L., Zingaretti C. M., Sassmann A., Quarta C., Schwitter C., et al. (2017). Adipocyte cannabinoid receptor CB1 regulates energy homeostasis and alternatively activated macrophages. J. Clin. Invest 127, 4148–4162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Petrocellis L., Ligresti A., Moriello A. S., Allarà M., Bisogno T., Petrosino S., Stott C. G., Di Marzo V. (2011). Effects of cannabinoids and cannabinoid-enriched Cannabis extracts on TRP channels and endocannabinoid metabolic enzymes. Br. J. Pharmacol. 163, 1479–1494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Salas-Quiroga A., Díaz-Alonso J., García-Rincón D., Remmers F., Vega D., Gómez-Cañas M., Lutz B., Guzmán M., Galve-Roperh I. (2015). Prenatal exposure to cannabinoids evokes long-lasting functional alterations by targeting CB1 receptors on developing cortical neurons. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 112, 13693–13698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Den Broeder M. J., Kopylova V. A., Kamminga L. M., Legler J. (2015). Zebrafish as a model to study the role of peroxisome proliferating-activated receptors in adipogenesis and obesity. PPAR Res. 2015, 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobin A., Gingeras T. R., Spring C., Flores R., Sampson J., Knight R., Chia N., Technologies H. S. (2016). Mapping RNA-seq with STAR. Curr. Protoc. Bioinforma 51, 586–597. [Google Scholar]

- Elmes M. W., Kaczocha M., Berger W. T., Leung K. N., Ralph B. P., Wang L., Sweeney J. M., Miyauchi J. T., Tsirka S. E., Ojima I., et al. (2015). Fatty acid-binding proteins (FABPs) are intracellular carriers for Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and cannabidiol (CBD). J. Biol. Chem. 290, 8711–8721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esposito G., Scuderi C., Valenza M., Togna G. I., Latina V., de Filippis D., Cipriano M., Carratù M. R., Iuvone T., Steardo L. (2011). Cannabidiol reduces Aβ-induced neuroinflammation and promotes hippocampal neurogenesis through PPARγ involvement. PLoS One 6, e28668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fish E. W., Murdaugh L. B., Zhang C., Boschen K. E., Boa-Amponsem O., Mendoza-Romero H. N., Tarpley M., Chdid L., Mukhopadhyay S., Cole G. J., et al. (2019). Cannabinoids exacerbate alcohol teratogenesis by a CB1-hedgehog interaction. Sci. Rep. 9, 1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fride E., Mechoulam R. (1996). Developmental aspects of anandamide: Ontogeny of response and prenatal exposure. Psychoneuroendocrinology 21, 157–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fried P. A., Smith A. M. (2001). A literature review of the consequences of prenatal marihuana exposure - An emerging theme of a deficiency in aspects of executive function. Neurotoxicol. Teratol. 23, 1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fried P. A., Watkinson B., Gray R. (2003). Differential effects on cognitive functioning in 13- to 16-year-olds prenatally exposed to cigarettes and marihuana. Neurotoxicol. Teratol. 25, 427–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstone J. V., McArthur A. G., Kubota A., Zanette J., Parente T., Jönsson M. E., Nelson D. R., Stegeman J. J. (2010). Identification and developmental expression of the full complement of cytochrome P450 genes in zebrafish. BMC Genomics 11. 1–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonçalves J., Rosado T., Soares S., Simão A., Caramelo D., Luís Â., Fernández N., Barroso M., Gallardo E., Duarte A. (2019). Cannabis and its secondary metabolites: Their use as therapeutic drugs, toxicological aspects, and analytical determination. Medicines 6, 31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granja A. G., Carrillo-Salinas F., Pagani A., Gómez-Cañas M., Negri R., Navarrete C., Mecha M., Mestre L., Fiebich B. L., Cantarero I., et al. (2012). A cannabigerol quinone alleviates neuroinflammation in a chronic model of multiple sclerosis. J. Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 7, 1002–1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant K. S., Petroff R., Isoherranen N., Stella N., Burbacher T. M. (2018). Cannabis use during pregnancy: Pharmacokinetics and effects on child development. Pharmacol. Ther. 182, 133–151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harkany T., Guzmán M., Galve-Roperh I., Berghuis P., Devi L. A., Mackie K. (2007). The emerging functions of endocannabinoid signaling during CNS development. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 28, 83–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasumi A., Maeda H., Yoshida K. (2020). Analyzing cannabinoid-induced abnormal behavior in a zebrafish model. PLoS One 15, 1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hegde V. L., Hegde S., Cravatt B. F., Hofseth L. J., Nagarkatti M., Nagarkatti P. S. (2008). Attenuation of experimental autoimmune hepatitis by exogenous and endogenous cannabinoids: Involvement of regulatory T cells. Mol. Pharmacol. 74, 20–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hegde V. L., Singh U. P., Nagarkatti P. S., Nagarkatti M. (2015). Critical role of mast cells and peroxisome proliferator–activated receptor γ (PPARγ) in the induction of myeloid-derived suppressor cells by marijuana cannabidiol in vivo. J. Immunol. 194, 5211–5222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hložek T., Uttl L., Kadeřábek L., Balíková M., Lhotková E., Horsley R. R., Nováková P., Šíchová K., Štefková K., Tylš F., et al. (2017). Pharmacokinetic and behavioural profile of THC, CBD, and THC+CBD combination after pulmonary, oral, and subcutaneous administration in rats and confirmation of conversion in vivo of CBD to THC. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 27, 1223–1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howlett A. C., Barth F., Bonner T. I., Cabral G., Casellas P., Devane W. A., Felder C. C., Herkenham M., Mackie K., Martin B. R., et al. (2002). International Union of Pharmacology. XXVII. Classification of cannabinoid receptors. Pharmacol. Rev. 54, 161–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hryhorowicz S., Walczak M., Zakerska-Banaszak O., Słomski R., Skrzypczak-Zielińska M. (2018). Pharmacogenetics of cannabinoids. Eur. J. Drug Metab. Pharmacokinet. 43, 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen T. L., Wu F., McMillin G. A. (2019). Detection of in utero exposure to cannabis in paired umbilical cord tissue and meconium by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Clin. Mass Spectrom. 14, 115–123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin M., Zhang B., Sun Y., Zhang S., Li X., Sik A., Bai Y., Zheng X., Liu K. (2020). Involvement of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ in anticonvulsant activity of α-asaronol against pentylenetetrazole-induced seizures in zebrafish. Neuropharmacology 162, 107760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong J., Garcia-Reyero N., Burgoon L., Perkins E., Park T., Kim C., Roh J. Y., Choi J. (2019). Development of adverse outcome pathway for PPARγ antagonism leading to pulmonary fibrosis and chemical selection for its validation: toxCast database and a deep learning artificial neural network model-based approach. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 32, 1212–1222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J., de Castro A., Lendoiro E., Cruz-Landeira A., López-Rivadulla M., Concheiro M. (2018). Detection of in utero cannabis exposure by umbilical cord analysis. Drug Test. Anal. 10, 636–643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirla K. T., Groh K. J., Steuer A. E., Poetzsch M., Banote R. K., Stadnicka-Michalak J., Eggen R. I. L., Schirmer K., Kraemer T. (2016). Zebrafish larvae are insensitive to stimulation by cocaine: Importance of exposure route and toxicokinetics. Toxicol. Sci. 154, 183–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein T. W., Friedman H., Specter S. (1998). Marijuana, immunity and infection. J. Neuroimmunol. 83, 102–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko J. Y., Farr S. L., Tong V. T., Creanga A. A., Callaghan W. M. (2015). Prevalence and patterns of marijuana use among pregnant and nonpregnant women of reproductive age. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 213, 201.e1–201.e10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krug R. G., Clark K. J. (2015). Elucidating cannabinoid biology in zebrafish (Danio rerio). Gene 570, 168–179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krug R. G., Lee H. B., El Khoury L. Y., Sigafoos A. N., Petersen M. O., Clark K. J. (2018). The endocannabinoid gene faah2a modulates stress-associated behavior in zebrafish. PLoS One 13, e0190897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunos G., Osei-Hyiaman D., Liu J., Godlewski G., Bátkai S. (2008). Endocannabinoids and the control of energy homeostasis. J. Biol. Chem 283, 33021–33025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam C. S., Rastegar S., Strähle U. (2006). Distribution of cannabinoid receptor 1 in the CNS of zebrafish. Neuroscience 138, 83–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laprairie R. B., Bagher A. M., Kelly M. E. M., Denovan-Wright E. M. (2015). Cannabidiol is a negative allosteric modulator of the cannabinoid CB1 receptor. Br. J. Pharmacol. 172, 4790–4805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leishman E., Murphy M., Mackie K., Bradshaw H. B. (2018). Δ9-Tetrahydrocannabinol changes the brain lipidome and transcriptome differentially in the adolescent and the adult. Biochim. Biophys. Acta - Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 1863, 479–492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Y. S., Lin T. Y., Wu J. J., Yao H. T., Chang S. L. Y., Chao P. M. (2017). Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α activation is not the main contributor to teratogenesis elicited by polar compounds from oxidized frying oil. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 18, 510–513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L. Y., Alexa K., Cortes M., Schatzman-Bone S., Kim A. J., Mukhopadhyay B., Cinar R., Kunos G., North T. E., Goessling W. (2016). Cannabinoid receptor signaling regulates liver development and metabolism. Development 143, 609–622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak K. J., Schmittgen T. D. (2001). Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2-ΔΔCT method. Methods 25, 402–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu H. C., MacKie K. (2016). An introduction to the endogenous cannabinoid system. Biol. Psychiatry 79, 516–525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luchtenburg F. J., Schaaf M. J. M., Richardson M. K. (2019). Functional characterization of the cannabinoid receptors 1 and 2 in zebrafish larvae using behavioral analysis. Psychopharmacology (Berl.) 236, 2049–2058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo T., Sakai Y., Wagner E., Dräger U. C. (2006). Retinoids, eye development, and maturation of visual function. J. Neurobiol. 66, 677–686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malfait A. M., Gallily R., Sumariwalla P. F., Malik A. S., Andreakos E., Mechoulam R., Feldmann M. (2000). The nonpsychoactive cannabis constituent cannabidiol is an oral anti-arthritic therapeutic in murine collagen-induced arthritis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97, 9561–9566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh-Armstrong N., McCaffery P., Gilbert W., Dowling J. E., Drager U. C. (1994). Retinoic acid is necessary for development of the ventral retina in zebrafish. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 91, 7286–7290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin B. R., Compton D. R., Thomas B. F., Prescott W. R., Little P. J., Razdan R. K., Johnson M. R., Melvin L. S., Mechoulam R., Susan J W. (1991). Behavioral, biochemical, and molecular modeling evaluations of cannabinoid analogs. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 40, 471–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Pinilla E., Varani K., Reyes-Resina I., Angelats E., Vincenzi F., Ferreiro-Vera C., Oyarzabal J., Canela E. I., Lanciego J. L., Nadal X., et al. (2017). Binding and signaling studies disclose a potential allosteric site for cannabidiol in cannabinoid CB2 receptors. Front. Pharmacol 8, 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miech R. A., Johnston L. D., O’Malley P. M., Bachman J. G., Schulenberg J. E., and Patrick, M. E. (2020). Monitoring the Future National Survey Results on Drug Use, 1975 − 2019, Volume 1: Secondary School Students. Ann Arbor, Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan. Available at: http://monitoringthefuture.org/pubs.html#monographs. Last accessed: 4/28/2021.

- Nagarkatti P., Pandey R., Rieder S. A., Hegde V. L., Nagarkatti M. (2009). Cannabinoids as novel anti-inflammatory drugs. Future Med. Chem. 1, 1333–1349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nawaji T., Yamashita N., Umeda H., Zhang S., Mizoguchi N., Seki M., Kitazawa T., Teraoka H. (2020). Cytochrome P450 expression and chemical metabolic activity before full liver development in zebrafish. Pharmaceuticals 13, 456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Shea M., Mallet P. E. (2005). Impaired learning in adulthood following neonatal Δ9-THC exposure. Behav. Pharmacol. 16, 455–461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Sullivan S. E. (2016). An update on PPAR activation by cannabinoids. Br. J. Pharmacol. 173, 1899–1910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Sullivan S. E., Kendall D. A. (2010). Cannabinoid activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors: Potential for modulation of inflammatory disease. Immunobiology 215, 611–616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Sullivan S. E., Sun Y., Bennett A. J., Randall M. D., Kendall D. A. (2009). Time-dependent vascular actions of cannabidiol in the rat aorta. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 612, 61–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Sullivan S. E., Tarling E. J., Bennett A. J., Kendall D. A., Randall M. D. (2005). Novel time-dependent vascular actions of Δ9- tetrahydrocannabinol mediated by peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 337, 824–831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandelides Z., Thornton C., Faruque A. S., Whitehead A. P., Willett K. L., Ashpole N. M. (2020a). Developmental exposure to cannabidiol (CBD) alters longevity and health span of zebrafish (Danio rerio). GeroScience 42, 785–800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandelides Z., Thornton C., Lovitt K. G., Faruque A. S., Whitehead A. P., Willett K. L., Ashpole N. M. (2020b). Developmental exposure to Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) causes biphasic effects on longevity, inflammation, and reproduction in aged zebrafish (Danio rerio). GeroScience 42, 923–936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pertwee R. G. (2008). The diverse CB 1 and CB 2 receptor pharmacology of three plant cannabinoids: Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol, cannabidiol and Δ9-tetrahydrocannabivarin. Br. J. Pharmacol. 153, 199–215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Psychoyos D., Vinod K. Y., Cao J., Xie S., Hyson R. L., Wlodarczyk B., He W., Cooper T. B., Hungund B. L., Finnell R. H. (2012). Cannabinoid receptor 1 signaling in embryo neurodevelopment. Birth Defects Res. Part B - Dev. Reprod. Toxicol. 95, 137–150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi C., Zhu Y., Reddy J. K. (2000). Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors, coactivators, and downstream targets. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 32, 187–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravinet Trillou C., Delgorge C., Menet C., Arnone M., Soubrié P. (2004). CB1 cannabinoid receptor knockout in mice leads to leanness, resistance to diet-induced obesity and enhanced leptin sensitivity. Int. J. Obes. 28, 640–648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reimand J., Arak T., Adler P., Kolberg L., Reisberg S., Peterson H., Vilo J. (2016). g:profiler—A web server for functional interpretation of gene lists (2016 update). Nucleic Acids Res. 44, W83–W89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson M. D., McCarthy D. J., Smyth G. K. (2010). edgeR: A bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics 26, 139–140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubino T., Vigano D., Realini N., Guidali C., Braida D., Capurro V., Castiglioni C., Cherubino F., Romualdi P., Candeletti S., et al. (2008). Chronic Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol during adolescence provokes sex-dependent changes in the emotional profile in adult rats: Behavioral and biochemical correlates. Neuropsychopharmacology 33, 2760–2771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubio P., de Fonseca F. R., Muñoz R. M., Ariznavarreta C., Martin-Calderón J. L., Navarro M. (1995). Long-term behavioral effects of perinatal exposure to Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol in rats: Possible role of pituitaryadrenal axis. Life Sci. 56, 2169–2176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryskamp D., Redmon S., Jo A., Križaj D. (2014). TRPV1 and endocannabinoids: Emerging molecular signals that modulate mammalian vision. Cells 3, 914–938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sales A. J., Crestani C. C., Guimarães F. S., Joca S. R. L. (2018). Antidepressant-like effect induced by cannabidiol is dependent on brain serotonin levels. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 86, 255–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz K., Mangels N., Haüssler A., Ferreirós N., Fleming I., Tegeder I. (2016). Pro-inflammatory obesity in aged cannabinoid-2 receptor-deficient mice. Int. J. Obes. 40, 366–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider C. A., Rasband W. S., Eliceiri K. W. (2012). NIH image to imageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat. Methods 9, 671–675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulenberg J. E., Johnston L. D., O’Malley P. M., Bachman J. G., Miech R. A., and Patrick, M. E. (2020). Monitoring the Future National Survey Results on Drug Use, 1975 − 2019: Volume 2, College Students & Adults Ages, pp. 19–60. Ann Arbor, Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan. Available at: http://monitoringthefuture.org/pubs.html#monographs. Last accessed: 4/28/2021.

- Smedley D., Haider S., Durinck S., Pandini L., Provero P., Allen J., Arnaiz O., Awedh M. H., Baldock R., Barbiera G., et al. (2015). The BioMart community portal: An innovative alternative to large, centralized data repositories. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, W589–W598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stančić A., Jandl K., Hasenöhrl C., Reichmann F., Marsche G., Schuligoi R., Heinemann A., Storr M., Schicho R. (2015). The GPR55 antagonist CID16020046 protects against intestinal inflammation. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 27, 1432–1445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sufian M. S., Amin M. R., Kanyo R., Allison W. T., Ali D. W., Ted Allison W., Ali D. W. (2019). CB1 and CB2 receptors play differential roles in early zebrafish locomotor development. J. Exp. Biol. 222, jeb206680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szatmari I., Pap A., Rühl R., Ma J.-X., Illarionov P. A., Besra G. S., Rajnavolgyi E., Dezso B., Nagy L. (2006). PPARγ controls CD1d expression by turning on retinoic acid synthesis in developing human dendritic cells. J. Exp. Med. 203, 2351–2362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeda S., Ikeda E., Su S., Harada M., Okazaki H., Yoshioka Y., Nishimura H., Ishii H., Kakizoe K., Taniguchi A., et al. (2014). Delta9-THC modulation of fatty acid 2-hydroxylase (FA2H) gene expression: Possible involvement of induced levels of PPARα in MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells. Toxicology 326, 18–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tham M., Yilmaz O., Alaverdashvili M., Kelly M. E. M., Denovan-Wright E. M., Laprairie R. B. (2019). Allosteric and orthosteric pharmacology of cannabidiol and cannabidiol-dimethylheptyl at the type 1 and type 2 cannabinoid receptors. Br. J. Pharmacol. 176, 1455–1469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyagi S., Sharma S., Gupta P., Saini A., Kaushal C. (2011). The peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor: A family of nuclear receptors role in various diseases. J. Adv. Pharm. Technol. Res. 2, 236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varvel S. A., Bridgen D. T., Tao Q., Thomas B. F., Martin B. R., Lichtman A. H. (2005). Δ9-Tetrahydrocannbinol accounts for the antinociceptive, hypothermic, and cataleptic effects of marijuana in mice. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 314, 329–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viveros M. P., Marco E. M., File S. E. (2005). Endocannabinoid system and stress and anxiety responses. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 81, 331–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow N. D., Han B., Compton W. M., McCance-Katz E. F. (2019). Self-reported medical and nonmedical cannabis use among pregnant women in the united states. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 322, 167–169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J., Vasaikar S., Shi Z., Greer M., Zhang B. (2017). WebGestalt 2017: A more comprehensive, powerful, flexible and interactive gene set enrichment analysis toolkit. Nucleic Acids Res. 45, W130–W137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei B. Q., Mikkelsen T. S., McKinney M. K., Lander E. S., Cravatt B. F. (2006). A second fatty acid amide hydrolase with variable distribution among placental mammals. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 36569–36578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfrum C., Borrmann C. M., Börchers T., Spener F. (2001). Fatty acids and hypolipidemic drugs regulate peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors α- and γ-mediated gene expression via liver fatty acid binding protein: A signaling path to the nucleus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 98, 2323–2328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yates A., Akanni W., Amode M. R., Barrell D., Billis K., Carvalho-Silva D., Cummins C., Clapham P., Fitzgerald S., Gil L., et al. (2016). Ensembl 2016. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, D710–D716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanelati T. V., Biojone C., Moreira F. A., Guimarães F. S., Joca S. R. L. (2010). Antidepressant-like effects of cannabidiol in mice: Possible involvement of 5-HT 1A receptors. Br. J. Pharmacol. 159, 122–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziouzenkova O., Orasanu G., Sharlach M., Akiyama T. E., Berger J. P., Viereck J., Hamilton J. A., Tang G., Dolnikowski G. G., Vogel S., et al. (2007a). Retinaldehyde represses adipogenesis and diet-induced obesity. Nat. Med. 13, 695–702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziouzenkova O., Orasanu G., Sukhova G., Lau E., Berger J. P., Tang G., Krinsky N. I., Dolnikowski G. G., Plutzky J. (2007b). Asymmetric cleavage of β-carotene yields a transcriptional repressor of retinoid X receptor and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor responses. Mol. Endocrinol. 21, 77–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziouzenkova O., Plutzky J. (2008). Retinoid metabolism and nuclear receptor responses: New insights into coordinated regulation of the PPAR-RXR complex. FEBS Lett. 582, 32–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.