Abstract

Background/Objectives.

COVID-19 required rapid innovation throughout the health care system. Home-based primary care (HBPC) practices faced unique challenges maintaining services for medically complex older populations for whom they needed to adapt a traditionally hands-on, model of care to accommodate restrictions on in-person contact. Our aim was to determine strategies used by New York City-area HBPC practices to provide patient care during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic with the goal of informing planning and preparation for home-based practices nationwide.

Design.

Cross-sectional qualitative design using semi-structured interviews and inductive and deductive thematic analysis.

Setting.

HBPC practices in the New York City (NYC) metro area during spring 2020.

Participants.

HBPC leadership including clinical/medical directors, program managers, nurse practitioners/nursing coordinators and social workers/social work coordinators (n=13) at 6 NYC-area practices.

Results.

Participants described care delivery and operational adaptations similar to those universally adopted across health care settings during COVID-19, such as patient outreach and telehealth. HBPC-specific adaptations included mental health services for patients experiencing depression and isolation, using multiple modalities of patient interactions to balance virtual care with necessary in-person contact, strategies to maintain patient trust, and supporting team connection of staff through daily huddles and emotional support during the surge of deaths among long-standing patients.

Conclusion.

NYC-area HBPC providers adapted care delivery and operations rapidly during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic. Keeping older, medically complex patients safe in their homes required considerable flexibility, transparency, teamwork and partnerships with outside providers. As the pandemic continues to surge around the US, HBPC providers may apply these lessons and consider resources needed to prepare for future challenges.

Keywords: Home-based primary care, homebound, home health, COVID-19

Introduction

While the impact of COVID-19 on nursing home residents is well documented, there has been less focus on the far greater number of homebound community-dwelling adults.1,2 These 7.5 million individuals experience disproportionately high rates of hospital and emergency department utilization, and are at risk of serious complications or death if exposed to COVID-19.3 They also face significant barriers to medical care and receive fewer primary care visits than nursing home residents.4 Home-based primary care (HBPC) provides longitudinal, interdisciplinary primary care delivered in the home to individuals lacking access to traditional primary care. HBPC is critical for this population during pandemics as it can help maintain access to health-related services and keep patients out of medical and congregate settings where they may be at higher risk for exposure and associated morbidity and mortality.5,6

On March 13, 2020, New York City (NYC) entered a state of emergency due to COVID-19, ordering residents to remain at home and maintain physical distancing.7 While care delivery was disrupted throughout health systems,8,9 HBPC practices faced particular challenges due to their service model and high-risk population. Our study aimed to determine how HBPC practices innovated to provide patient care early in the crisis, with the goal of informing COVID-19 planning and preparation for practices serving medically complex older adults nationwide through ongoing surges and a potential “second wave” of COVID-19.

Methodology

Study Design, Setting and Participants

Our project was a qualitative arm of the “Home-based Primary Care for Homebound Seniors: A Randomized Controlled Trial” (HOME) study.10 Because HBPC is a multidisciplinary, team-based model, we recruited practice leaders across multiple roles for interviews to obtain a range of perspectives and experiences. Interviews focused on experiences during the height of the NYC pandemic (March-June 2020) and were conducted from May-July 2020.

Recruitment

We recruited participants through purposeful and snowball sampling. Using professional networks and HBPC associations, we identified practices varying by affiliation, profit status, ownership model, and size. We aimed to recruit and interview medical, nursing and social work leadership from each practice, and asked participants to refer additional practices. We continued interviews until reaching thematic saturation.

Data Collection and Analysis

We obtained informed verbal consent and conducted 30-45 minute semi-structured interviews via Zoom videoconference, recording and transcribing interviews verbatim. The authors developed the interview guide around three topics: 1) care delivery challenges due to COVID-19; 2) adaptations; and 3) advice for other practices. We probed how practices were managing COVID and non-COVID patient care; end-of-life care, telehealth, community-based resources (home health and social services), and staffing. Participants described their roles and tenure. We piloted the guide with three providers from the Mount Sinai Visiting Doctors program. Pilot interview data are included in our sample.

We conducted a qualitative thematic analysis using a combined inductive and deductive approach.11 First, two coders (EF and KG) reviewed the same two interviews independently using focused coding to identify “adaptations” and “advice”, sub-coding emergent categories within each area. We noted a priori topic areas (e.g., telehealth, patient care), as well as emerging ideas (e.g., care modalities, team building). We developed an initial codebook based on these analytic memos and discussion.12 The coders applied the codebook to these two interviews, comparing, discussing, and refining it with additional researchers (AF and KO) until no new codes emerged. We then coded the remaining interviews independently and reviewed each other’s coding, discussing discordance until reaching consensus, and used these codes to draw larger themes. Data were analyzed using Dedoose qualitative software.13 Research activities were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai.

Results

We interviewed 13 staff members from 6 practices as described in Table 1, including clinical/medical directors (CDs), program managers (PMs), nurse practitioners/nursing coordinators (NCs) and social workers/social work coordinators (SWs).

Table 1:

Participant and Practice Characteristics

| Participant characteristics | N |

|---|---|

| Total participants | 13 |

| Role | |

| Medical/clinical director | 6 |

| Program manager | 1 |

| Nurse/nursing coordinator | 3 |

| Social worker/social work coordinator | 3 |

| Years working in program | |

| Mean | 11 |

| Median | 12 |

| Range | 1-18 |

| Practice characteristics | N |

| Total Practices | 6 |

| Area served | |

| Urban | 5 |

| Suburban | 1 |

| Primary sponsor/owner | |

| Health system | 4 |

| Independent provider/group | 2 |

| Profit status | |

| For-profit | 1 |

| Non-profit | 5 |

| Sector | |

| Private | 5 |

| Public | 1 |

| Daily patient census before 3/1/2020 | |

| Mean | 811 |

| Median | 900 |

| Range | 45-1400 |

| Years in existence | |

| Mean | 13.5 |

| Range | 1-25 |

| Participants interviewed per program | |

| Min | 1 |

| Max | 4 |

Practice Adaptations

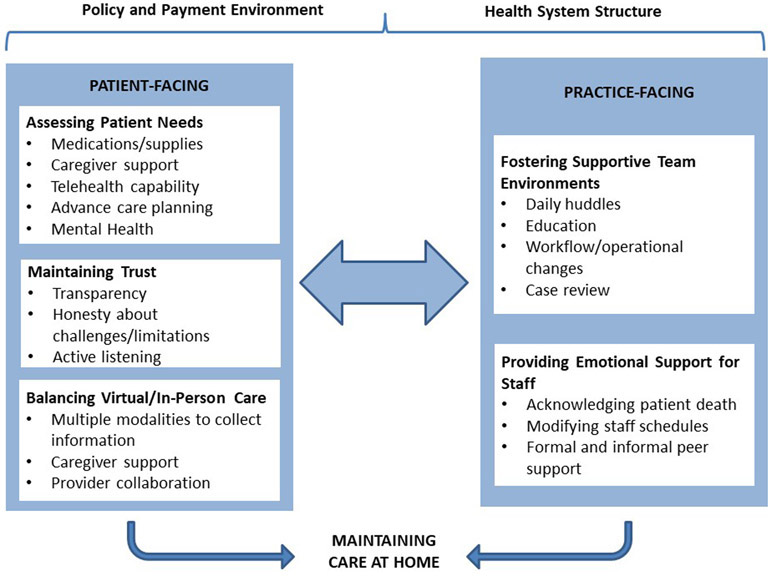

Participants described their primary goal during the pandemic as keeping patients “at home, with care” (CD, Practice 3). These efforts included changes in care delivery (“patient-facing”) and operational functions (“practice-facing”). While many adaptations have been broadly adopted as usual care (e.g., patient outreach and telehealth), participants also reported innovations specific to their practice model and patient population, including strategies to maintain patient trust, balancing virtual and in-person care, and supporting staff [See Figure 1].

Figure.

HBPC practices maintained care during COVID-19 through patient- and practice-facing adaptations. Adaptations were and will continue to be influenced by the broader policy and payment environment and structure of the health care system.

Patient-facing Adaptations

Assessing and addressing isolated patients’ needs.

HBPC practices conducted regular patient assessments around medication and medical supply needs, caregiving support (paid and unpaid), housing, food security, and goals of care. Given the medically complex patient population, many practices also completed advance care plans, and walked patients and caregivers through emergency planning scenarios, asking “what would you do if your aides could not come?” (CD, Practice 3). Two practices, concerned about social isolation, screened for loneliness, anxiety and depression through phone calls and medical chart reviews and connected patients with mental telehealth services, while one social worker kept a “short list” of patients who “need a little TLC” to check on frequently (Practice 6).

Maintaining patient-provider trust.

HBPC practices often had longstanding relationships with patients, and providers felt the need to reassure patients and caregivers that their level of care would be maintained. To maintain trust, providers took deliberate steps to clearly describe how care would be delivered, why modifications were being made, explain safety precautions, talk through patients’ fears, and discuss challenges; for instance, explaining that oxygen may not be readily available due to supply shortages. One nursing coordinator focused on “active listening and just letting them speak and telling them that I felt the same way, that this wasn’t because they were homebound and because they were old” (NC, Practice 5). While some patients wanted continued in-person care (“Why aren’t you coming? When are you coming to see me?”), practitioners also noted that because of these trusting relationships, patients overall were resilient and accommodating.

Balancing in-person and virtual care to limit exposure.

All but one practice quickly transitioned to telehealth, and several initially stopped admitting patients since they could not perform in-person intake visits. Overall, practices found telehealth valuable (“there’s something very personal about seeing someone’s face”). However, video visits could be challenging due to patients’ physical and cognitive limitations, and often required caregiver or aide assistance. In this high-need patient population, some in-person visits were unavoidable. One nursing coordinator noted that when patients had difficulty navigating telehealth, a nurse could make a home visit to initiate and facilitate the call with the physician. Providers also limited face-to-face contact by collecting as much information as possible ahead of a visit; for example, one provider conducted patient interviews by phone from the driveway before entering the home.

Practices balanced virtual and in-home care by engaging other providers in and outside their health systems. In one practice, community paramedics delivered pulse oximeters and thermometers to “COVID-suspect” patients, while nurses conducted daily follow-up calls to determine if higher level care was necessary. However, COVID-related disruptions affected outside services; one nursing coordinator described making multiple calls to state officials to help contracted home health agencies get sufficient PPE to maintain services.

Operational Adaptations

Fostering supportive team environments.

Although most practices moved primarily to telework, they took steps to maintain and enhance the team connection many described as critical to HBPC. All but one practice increased the frequency of team meetings, moving from weekly or bi-weekly to daily virtual all-staff “huddles” at the pandemic’s height. Meetings helped teams manage rapid changes in COVID-19 guidance and patients’ health status by covering provider education on infection control, workflow and operational changes, case reviews, and an opportunity to “express their feelings and frustrations” (CD, Practice 1). Huddles also helped manage staffing changes as many system-based practices adjusted to clinician redeployments or staff illness. Overall, participants reported huddles were welcome and helped manage the stress of their intensified workload, although they could not completely alleviate it. “Having team meetings every single day sounds like, ‘oh, it’s a lot,’” said one social worker (Practice 1). “It really does set a tone and it really just helps. You really feel connected and you’re not doing this by yourself.”

Providing emotional support for staff.

Rapid increases in patient mortality deeply affected HBPC staff. Participants estimated that at the height of the surge their practices experienced three to five times the usual number of deaths. One social worker explained the emotional strain, noting “that’s really the difference in our practice and other home-based programs, you work with people for many, many years. You really get to know them, their family, and their story.” (SW, Practice 3) One team that previously held occasional “remembrance meetings” to discuss patients who had died began holding meetings bi-weekly. The practice also redistributed on-call schedules to alleviate the burden of managing multiple patient deaths on providers.

Participants’ specific recommendations are described further in Table 2.

Table 2:

Recommended Adaptations to Manage COVID-19 in Home-Based Primary Care

| Patient-Facing Adaptations | ||

|---|---|---|

| Outreach & Assessment | Practice emergency scenarios; initiate advance care planning | Hav[e] proactive goals of care conversations…like, “What would you do if your aide could not come in?…Who’s going to be able to take care of you if you are dependent on somebody?”…You can’t always think of every scenario but try to think about as many as you can. (CD, Practice 3) |

| Proactively assess high-risk patients; screen for social determinants of health | [We had] a template of questions to ask people to ensure that they knew to contact us with certain symptoms, that they have enough food, that they had a supply of medication, that they had a caregiver if they needed one” (CD, Practice 1). | |

| Keep up-to-date records | Keep very good records on your patient population….up-to-date contact information for family members….if the patient doesn’t have [email], who in the family has an email? What’s their smart phone number? Can we reach them? (SW, Practice 1) | |

| Consent patients to telehealth early or on admission | Telehealth has been really impactful and if they could do that sooner than later and get the consent form…we were able to get the vast majority of our patients consented to use telehealth, which was truly incredible. Literally, we just worked all day from 9:00 to 5:00, just calling every patient. (SW, Practice 1) | |

| Maintaining trusting patient-provider relationships | Be patient and understanding | Be patient because it’s not easy. You got to understand these are old people. If it’s a geriatric home based primary care group, they’re old. They’re not going to understand this [telehealth]…just be patient and just try to find the best platform for your visits that you can. (NC, Practice 1) |

| Be transparent | [We explain] to the family, “to have the safest visit and protect you and protect our care team, we’re going to have some of the conversation on the phone before we go in. It’d be helpful if there aren’t people that don’t need to be part of the conversation, if they can be in another part of the home.” (CD, Practice 4) | |

| Educate patients and caregivers | When we’re in the hospital or in the office, we have a cleaning staff. We have proper ventilation. We have all that that helps protect us. We don’t have that in the home. So, it’s patient education, family education so that resuming the visits could be safer for the providers also. (NC, Practice 5) | |

| Balancing virtual and in-person care | Employ multiple modes of care delivery | Using telehealth as an initial sort of triage has been really, really helpful. It has expanded what we can manage, but for the work that does really need an in-person visit, it helped prep that visit to be the most efficient and effective that it can be. (CD, Practice 4) |

| Leverage local and community resources |

I have a really close relationship with a hospice. We partnered with them tremendously. We always had, but even more so now. (NC, Practice 3) Through the city, you can get groceries delivered…No one needs to be going hungry right now in the homebound population who’s connected with a social worker, doctors like ours who know about these resources. (SW, Practice 3) |

|

| Practice-facing Adaptations | ||

| Building team connection | Conduct regular staff meetings; keep lines of communication open |

You can never stay too connected with your staff…You have to have a lot of transparency and [interact] with your staff members much, much more than during regular operations. (CD, Practice 1) We had chats going on. We opened up a SharePoint website so that we could put real-time information up on there for people to access. We had daily meetings. We had every week education sessions focused on COVID. We had weekly sessions on diagnostic and treatment dilemmas where we encouraged [staff] ahead of time to submit questions so that we had time to prepare (NC, Practice 3) |

| Involve all staff in decision making, work as a team | This has also been a really inspiring time for people or teams to come together and problem-solve and be creative in our problem-solving, to both identify needs and think how to meet those needs. Some of which are very practical like getting thermometers and masks to people who need it and groceries, and others more complicated. (PM, Practice 5) | |

| Ensure dedicated staffing and prepare for staff shortages | We had multiple providers who were redeployed…so, what is your absolute minimum to stay open? Do you have enough PPE? I think those are some of the scenarios to think about. (CD, Practice 3) | |

| Provide staff training and education | [Team meetings] expanded into an opportunity to do some training and overview of home-based medical care in general, and then have evolved into case discussions to help learn from the team. (CD, Practice 4) | |

| Learn from peer programs | If you can have a contact or a program where somebody’s already been through this… you can have a lot of questions and you may as well just ask them instead of reinventing the wheel. (CD, Practice 5) | |

| Emotional support for staff | Consider practice changes to avoid burnout | We shifted the call schedule…and split it up. People were definitely much better. [Knowing] that you’re only on for 12 hours or 6 hours is really helpful” (CD, Practice 3) |

| Create peer support opportunities | The big thing that has really impacted the staff has been the deaths. That’s been hard. Patients that we have worked with for a very long time…we have condolence meetings when the team talks about the people who’ve died. It’s very important not to let that just pass by. (SW, Practice 3) | |

Bold = recommendations specific to HBPC practices and population; not bold = recommendations that have been widely adopted

Discussion

HBPC practices implemented a range of patient and practice-facing strategies in the face of a high degree of clinical uncertainty and societal stress in the early stage of the COVID-19 pandemic. Our study demonstrates the flexibility and resilience of HBPC practices and providers. Their experiences and recommendations provide important insights that may support care delivery by HBPC providers and other organizations serving medically complex patients nationwide.

Practices prioritized open and honest communication with patients, as well as balancing telehealth with the need to at times provide hands-on care.14 Because of their long-standing relationships, providers were able to maintain trust, highlighting the benefits of team-based, longitudinal patient care.15 In addition, these findings show a need to acknowledge the central role of and need to support paid and unpaid caregivers in facilitating virtual and in-person care16,17 and the importance of a flexible approach to coordinating care for patients for whom telehealth alone may not be sufficient.

Within their practices, participants recognized the importance of keeping multidisciplinary teams connected through daily “huddles”, case review, and collaborations with outside providers. Despite these support efforts, participants reported psychological exhaustion caused by the volume of patient deaths and rapid pace of change. Our results suggest that similar to other frontline healthcare workers, the pandemic has had a substantial effect on the mental health of HBPC providers.18-20

Best practices during the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond

The global scale of the COVID-19 pandemic, uncertainty around infection control and treatment, and the lack of a coordinated government response have put both home-based and other practices under considerable strain. While practices have risen to the challenge, supporting them in maintaining innovation through an emergency with no clear endpoint will require organizational resources and support including dedicated staffing, funding, and investments in technology to support remote work, telehealth and staff well-being.

From a policy standpoint, our findings also highlight how payment and policy changes will be critical to maintaining new models of care. Many temporary changes in reimbursement and regulation of services like telehealth and mental health21 should be made permanent, and expanded to reflect the flexible, multi-disciplinary care critical to enabling older, medically complex patients to reside in the community (e.g., reimbursing social work visits).22 Reimbursement from insurance is often insufficient to support HBPC.23-25

Study Strengths and Limitations

NYC was initially among the hardest hit metropolitan areas of the world, providing important learning opportunities. We began interviews shortly after the peak of NYC cases, reducing recall bias. We included a diversity of practice types and multiple interviewees across practices using theoretical sampling. However, our sample represents fewer than 25% of NYC area HBPC practices.26 The experiences of providers across the country may be substantially different, thus limiting generalizability. Additionally, our findings must be considered in light of the rapidly evolving pandemic.

Conclusions

Our study provides an important early look at HBPC services during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, a model that requires more attention and resources to reduce health risks for medically complex older adults. NYC HBPC providers adapted to unprecedented risks and restrictions by rapidly altering their approach to care delivery and maintaining trust with staff and patients. However, these efforts require ongoing financial and administrative resources. With the pandemic continuing to surge, HBPC providers may apply these lessons to prepare for the challenges ahead.

Financial Disclosure:

This study is funded by the National Institute on Aging (NIA, 1R01AG052557).

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have declared no conflict of interest for this article.

Sponsor’s Role: The sponsors played no role in any of the design, conduct, or preparation of this article.

The authors thank Albert L. Siu, MD and two anonymous reviewers for their invaluable feedback on this manuscript. This article does not represent the views of the US Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States government.

References

- 1.Ornstein KA, Leff B, Covinsky KE, et al. Epidemiology of the homebound population in the United States. JAMA Internal Medicine. 2015;175(7):1180–1186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hayes S SC, McCarthy D, Radley DC, Abrams S, Shah T, Anderson G. High-need, high-cost patients: who are they and how do they use health care? A population-based comparison of demographics, health care use, and expenditures. Commonwealth Fund; August 29, 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stokes EK, Zambrano LD, Anderson KN, et al. Coronavirus disease 2019 case surveillance—United States, January 22–May 30, 2020. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2020;69(24):759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yao N, Ritchie C, Camacho F, Leff B. Geographic concentration of home-based medical care providers. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35(8):1404–1409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Home-based primary care interventions--draft systematic review. 2015.

- 6.Edes T, Kinosian B, Vuckovic NH, Nichols LO, Becker MM, Hossain M. Better access, quality, and cost for clinically complex veterans with home-based primary care. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62(10):1954–1961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mayor de Blasio Issues State of Emergency [press release]. New York, NY, March 13, 2020. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reckrey JM. COVID-19 confirms it: paid caregivers are essential members of the healthcare team. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kent EE, Ornstein KA, Dionne-Odom JN. The family caregiving crisis meets an actual pandemic. Journal of pain and symptom management. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reckrey JM, Brody AA, McCormick ET, et al. Rationale and design of a randomized controlled trial of home-based primary care versus usual care for high-risk homebound older adults. Contemporary clinical trials. 2018;68:90–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Creswell JW. Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches. Sage; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lincoln YS, Guba EG. But is it rigorous? Trustworthiness and authenticity in naturalistic evaluation. New directions for program evaluation. 1986;1986(30):73–84. [Google Scholar]

- 13.SocioCultural Research Consultants LLC. Dedoose Version 6.1.18, web application for managing, analyzing, and presenting qualitative and mixed method research data. In:2015. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goodman-Casanova J, Durá-Pérez E, Guzmán-Parra J, Cuesta-Vargas A, Mayoral-Cleries F. Telehealth home support during COVID-19 confinement: Survey study among community-dwelling older adults with mild cognitive impairment or mild dementia. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Batalden M, Batalden P, Margolis P, et al. Coproduction of healthcare service. BMJ quality & safety. 2016;25(7):509–517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sterling MR, Tseng E, Poon A, et al. Experiences of home health care workers in New York City during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic: a qualitative analysis. JAMA Internal Medicine. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dang S, Penney LS, Trivedi R, et al. Caring for caregivers during COVID-19. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ayanian JZ. Mental health needs of health care workers providing frontline COVID-19 care. Paper presented at: JAMA Health Forum 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ripp J, Peccoralo L, Charney D. Attending to the emotional well-being of the health care workforce in a New York City health system during the COVID-19 pandemic. Academic Medicine. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Spray AM, Patel NA, Sood A, et al. Development of wellness programs during the covid-19 pandemic response. Psychiatric Annals. 2020;50(7):289–294. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bartels SJ, Baggett TP, Freudenreich O, Bird BL. COVID-19 emergency reforms in massachusetts to support behavioral health care and reduce mortality of people with serious mental illness. Psychiatric Services. 2020:appi. ps. 202000244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meisner BA, Boscart V, Gaudreau P, et al. Interdisciplinary and Collaborative approaches needed to determine impact of covid-19 on older adults and aging: CAG/ACG and CJA/RCV Joint Statement. Canadian Journal on Aging/La Revue canadienne du vieillissement. 2020:1–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Doshi A, Platt Y, Dressen JR, Mathews BK, Siy JC. Keep calm and log on: telemedicine for COVID-19 pandemic response. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(5):302–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ranganathan C, Balaji S. Key factors affecting the adoption of telemedicine by ambulatory clinics: insights from a statewide survey. Telemedicine and e-Health. 2020;26(2):218–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. List of telehealth services. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-General-Information/Telehealth/Tel. Published 2020. Accessed July 20, 2020.

- 26.Pepper L, Michener A, Kinosian B. US house call practices in 2014: Mismatch of providers, practices, and patients. Paper presented at: Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 2015. [Google Scholar]