Abstract

Background

Cancer is the leading cause of death among Hispanics/Latinos. Thus, understanding health-related quality of life (HRQOL) needs among this diverse racial/ethnic group is critical. Using Ferrell’s multidimensional framework for measuring QOL, we synthesized evidence on HRQOL needs among Hispanic/Latino cancer survivors.

Methods

We searched MEDLINE/PubMed, EMBASE, CINAHL, and PsycINFO, for English language articles published between 1995 and January 2020, reporting HRQOL among Hispanic/Latino cancer survivors in the USA.

Results

Of the 648 articles reviewed, 176 met inclusion criteria, with 100 of these studies focusing exclusively on breast cancer patients and no studies examining end-of-life HRQOL issues. Compared with other racial/ethnic groups, Hispanics/Latinos reported lower HRQOL and a higher symptom burden across multiple HRQOL domains. Over 80% of studies examining racial/ethnic differences in psychological well-being (n = 45) reported worse outcomes among Hispanics/Latinos compared with other racial/ethnic groups. Hispanic/Latino cancer survivors were also more likely to report suboptimal physical well-being in 60% of studies assessing racial/ethnic differences (n = 27), and Hispanics/Latinos also reported lower social well-being relative to non-Hispanics/Latinos in 78% of studies reporting these outcomes (n = 32). In contrast, reports of spiritual well-being and spirituality-based coping were higher among Hispanics/Latinos cancer survivors in 50% of studies examining racial/ethnic differences (n = 15).

Discussion

Findings from this review point to the need for more systematic and tailored interventions to address HRQOL needs among this growing cancer survivor population. Future HRQOL research on Hispanics/Latinos should evaluate variations in HRQOL needs across cancer types and Hispanic/Latino subgroups and assess HRQOL needs during metastatic and end-of-life disease phases.

Keywords: Latino, Cancer survivor, Health-related quality of life, Supportive care

Background

Cancer is the leading cause of death among Hispanics/Latinos [1]. In the USA in 2018, there were approximately 150,000 incident cancer cases and 43,000 cancer-related deaths among Latinos [2]. For Hispanic/Latino men, prostate, colorectal, and lung are the three most common cancers [2]; and among Hispanic/Latina women, the three most prevalent cancers are breast, thyroid, and uterine cancer [2]. Although Hispanics/Latinos have a 25% lower cancer incidence rate and 30% lower cancer mortality rate than non-Hispanic/Latino Whites; risk of infection-related cancers such as stomach, liver, and cervical cancer is nearly twice as high among Hispanics/Latinos [1]. Moreover, emerging evidence suggests that as immigration rates slow, and more Hispanics/Latinos are in the USA long-term, Hispanic/Latino incidence/mortality cancer rates will rise and become more similar to other racial/ethnic groups in the USA [3, 4]. These findings underscore the imperative need to better understand the cancer experience of this growing, heterogeneous US population.

Compared with non-Hispanic/Latino Whites, Hispanics/Latinos are more likely to report structural barriers to care including lower incomes and education, lack of health insurance, and no usual source of healthcare [5]. These socioeconomic differences may contribute to higher rates of late stage cancer diagnoses, and resultantly more aggressive treatment, among Hispanics/Latinos [2]. Aggressive cancer treatment modalities are known to pose significant symptom and quality of life burdens. Additionally, Hispanic/Latino cancer survivors face a range of psychosocial factors that may negatively affect their care quality and quality of life, including acculturation challenges, language barriers, and limited cancer self-efficacy [6–8]. In particular, language barriers have been linked to low patient satisfaction with their health care [9]. Research also suggests that Hispanics/Latinos without cancer are less likely to receive supportive care for mental health issues [10–13]. Thus, Hispanics/Latinos may be at increased risk for quality of life decrements following their cancer diagnoses and treatments.

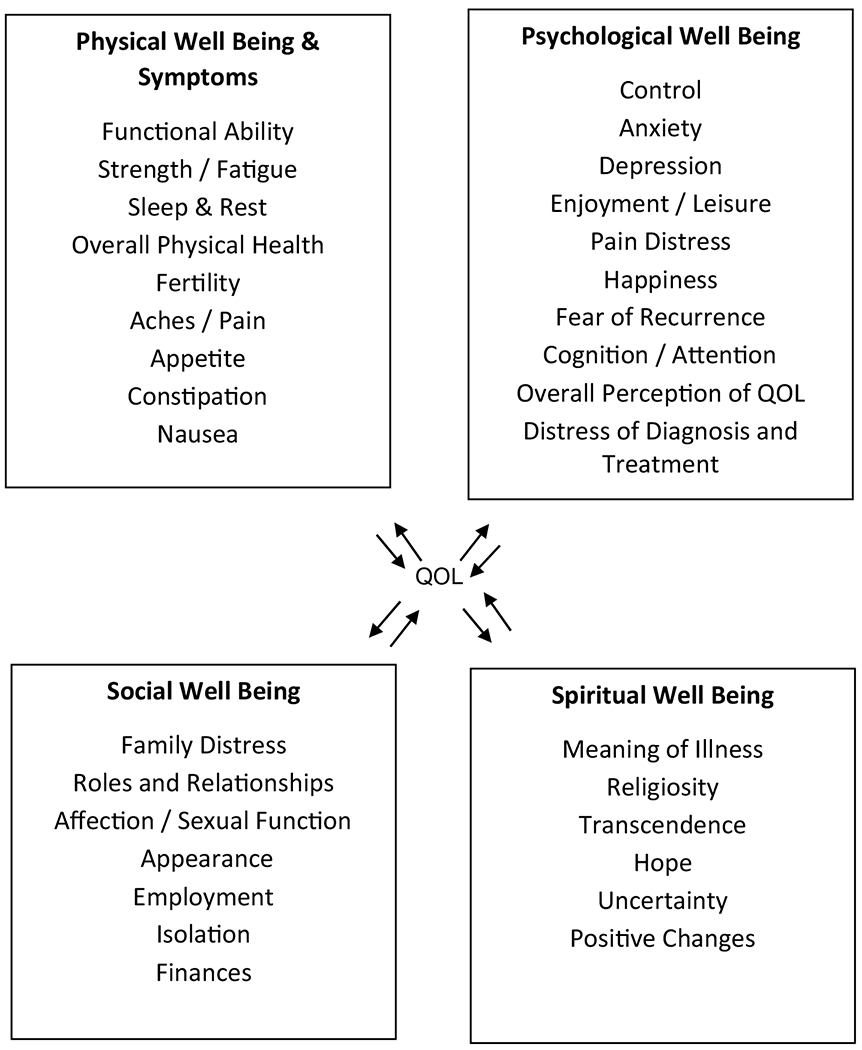

Although previous systematic reviews summarized health-related quality of life (HRQOL) patterns among Latino cancer survivors, prior studies were largely focused on women with breast cancer, did not consider HRQOL experiences of survivors at different phases of the cancer care continuum, from the time of diagnosis to death, and/or failed to account for multiple domains of HRQOL [14–23]. Ferrell’s Conceptual Framework on quality of life [24] has been used to study HRQOL among racially/ethnically diverse cancer survivors [24–26]. The framework considers four distinct HRQOL domains: 1) physical well-being (e.g., nausea, fatigue), social well-being (e.g., distress, sexual function), psychosocial well-being (e.g., anxiety, depression), and spiritual well-being (Fig. 1) [24]. The objective of this study was to synthesize evidence on HRQOL needs among Hispanic/Latino cancer survivors in the USA using Ferrell’s HRQOL framework. This systematic review includes studies reporting HRQOL outcomes and needs among US-based Hispanic/Latino cancer survivors, of all cancer types, from the time of diagnosis to death. This broad focus allows for a comprehensive assessment of the existing evidence on Hispanic/Latino HRQOL needs. Additionally, we present recommendations for advancing HRQOL research on Hispanic/Latino cancer survivors and improving supportive care services for this rapidly growing patient population.

Fig. 1.

Ferrell’s quality of life in cancer survivors

Methods

Literature search strategy

A comprehensive literature search was conducted in MEDLINE/PubMed, EMBASE, CINAHL, and PsycINFO, to identify relevant articles published from 1995 (publication year of Ferrell’s original article on Measurement of QOL in Cancer Survivors [24]) through January 2020. Search terms were optimized for each database and included Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) and related text/keyword searches when appropriate. The search focused on terms used to describe (a) HRQOL (e.g., financial burden, spirituality, depression, insomnia, sexual dysfunction); in (b) Hispanic/Latino (e.g., Hispanic, Latino, Puerto Rican, Cuban); (c) cancer survivors (e.g., cancer, carcinoma*, neoplasm*) AND (survivorship, survivor OR survivors). The full search strategy can be found in Supplemental Appendix Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Eligibility criteria were developed with respect to the population, outcomes of interest, study design, and timing (PICOTS), and publication type. Studies were eligible for inclusion if they presented results on HRQOL among Hispanic/Latino cancer survivors of any age. Consistent with current definitions of a “cancer survivor,” we employed a lifetime definition capturing time from cancer diagnosis until death from any cause [27, 28]. We used the US Census Bureau’s definition of Hispanics/Latinos (individuals of Cuban, Mexican, Puerto Rican, South or Central American, or other Spanish culture or origin regardless of race [29]). Conference abstracts and non-peer-reviewed publications were excluded from this review, as were non-empirical studies (with the exception of literature reviews), non-English studies, non-US-based studies, and studies not separately reporting HRQOL for our target population (i.e., Hispanic/Latino cancer survivors).

Study selection

Two trained research assistants (RAs) used the eligibility criteria to independently screen titles and abstracts in duplicate for inclusion/exclusion. Studies with titles and abstracts that met the inclusion criteria or lacked adequate information to determine inclusion/exclusion underwent full-text review. During the full-text review, two RAs independently reviewed all full-text articles in duplicate for inclusion/exclusion. If both reviewers agreed that a study did not meet eligibility criteria, the study was excluded. A senior member of the review team resolved any conflicts. Covidence software was used for this review. The software was set to dual screening mode which required at least 2 reviewers to agree for article inclusion/exclusion at each review phase.

Data extraction and quality appraisal

Three independent reviewers abstracted data from the 176 eligible articles using a standardized abstraction form (Supplemental Appendix Table 2) that captured study participant characteristics, conceptual frameworks employed, study design, HRQOL measures, and Latino-specific HRQOL findings. The three reviewers abstracted the first five articles together to ensure consistency. At least two reviewers were involved in each article abstraction — one person conducted the primary abstraction and the second person performed quality control. Reviewers also assessed the quality of each article using the 22-item Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies (STROBE) tool [30] for articles with quantitative methods, and the ten-item Critical Appraisal Skills Program (CASP) tool [31] for qualitative studies. Each study was assigned an appraisal tool ratio, calculated as the number of STROBE/CASP criteria met divided by the total number of tool criteria (Supplemental Appendix Table 2) [32]. No studies were excluded based on quality appraisal ratio scores.

Results

Literature search results

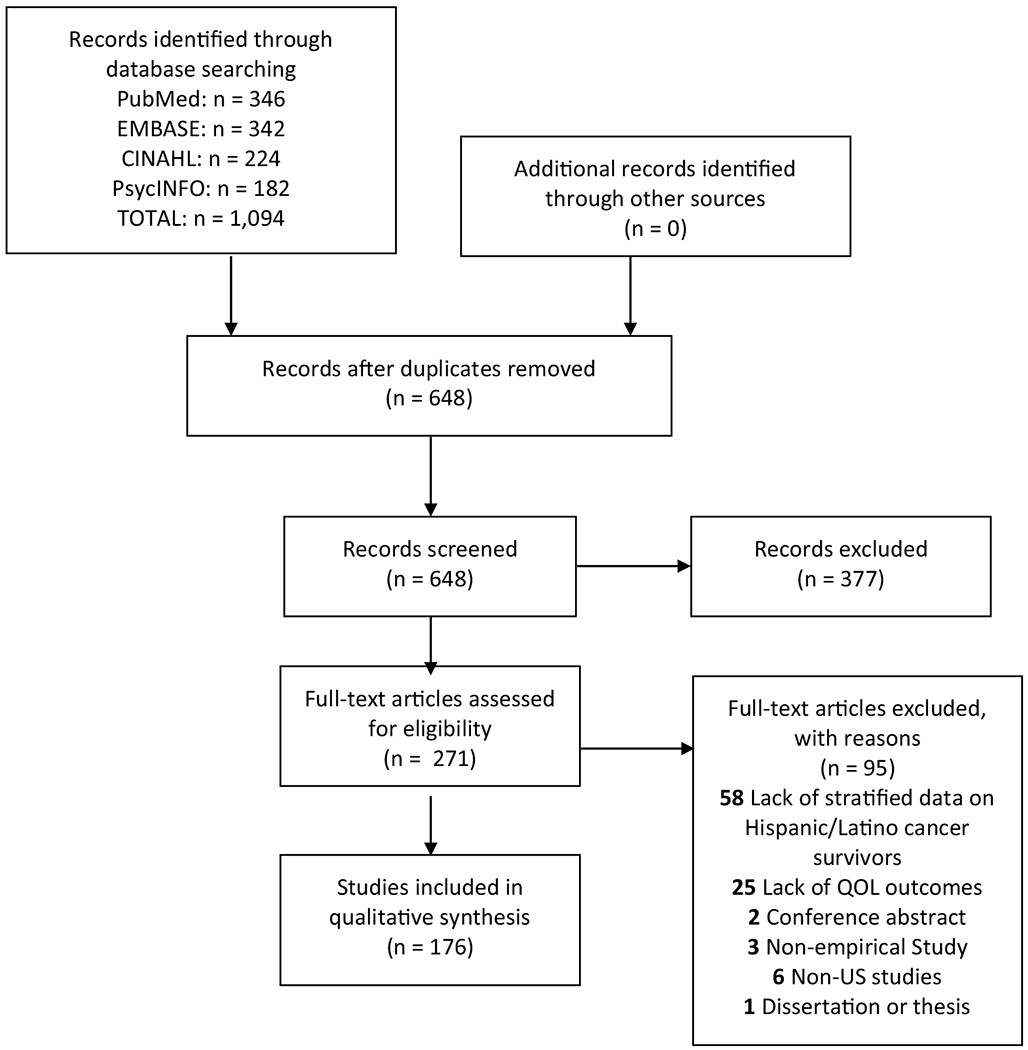

A total of 1,094 articles were identified through database searching, of which 648 were non-duplicates. A total of 377 articles were excluded during the initial title and abstract screening phase. Of the remaining 271 articles, 95 articles were excluded during full-text review, and 176 articles met all inclusion criteria (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Literature flow diagram

Description of included studies

The study designs of the 176 articles varied and included 90 (51.1%) cross-sectional quantitative, 35 (19.9%) longitudinal quantitative, 30 (17.0%) qualitative, eight (4.5%) mixed-methods, and 13 (7.4%) literature reviews (Table 1). One hundred studies focused exclusively on breast cancer, while the remainder included other (e.g., prostate) or multiple cancers. Time since cancer diagnosis for study participants ranged from 0–120 months post-diagnosis. Most studies focused on adults. Forty studies employed a HRQOL conceptual framework and the majority of studies used validated HRQOL measurement instruments (e.g., Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–General [FACT-G]). All studies met at least 70% of the critical appraisal criteria, and 94 studies met > 70% of the appraisal criteria. Although literature reviews were included in this study, they were excluded from critical appraisal.

Table 1.

Summary of Included Studies

| HRQOL domains | Study design | Examples of commonly explored HRQOL measures |

|---|---|---|

| Overall | Quantitative Cross-sectional: 25 studies [1–25] Quantitative Longitudinal: 7 studies [26–31] Qualitative: 1 study [32] Mixed-Methods: 0 studies Literature Review: 4 studies [33–36] |

Overall: [2–8, 10, 11, 13–15, 17, 19–26, 32, 34–36] |

| Physical well-being | Quantitative Cross-sectional: 57 studies [2, 5, 6, 8, 9, 12–15, 17, 20, 21, 23, 24, 37–79] Quantitative Longitudinal: 21 studies [26, 28, 31, 80–97] Qualitative: 12 studies [98–108] Mixed-Methods: 7 studies [109–115] Literature Review: 8 studies [34–36, 116–120] |

General Physical Health/ Functional Status: [5, 8, 14, 24, 28, 32, 38, 39, 41, 43, 46, 47, 50, 53, 54, 56, 59, 65, 68–70, 81, 83, 85, 90, 93, 94, 110–113] Lymphedema: [36, 51, 86, 97, 121] Pain: [51, 52, 69, 89, 101, 102, 106, 112] Fatigue: [28, 51, 64, 94, 103, 106] |

| Psychological well-being | Quantitative Cross-sectional: 74 studies [2–9, 12–18, 20, 21, 23–25, 37–44, 46, 48–65, 67–69, 71–76, 78, 122–138] Quantitative Longitudinal: 23 studies [26, 28, 31, 81–85, 87, 88, 90, 91, 93–96, 139–145] Qualitative: 27 studies [32, 98–108, 146–160] Mixed-Methods: 7 studies [109–112, 114, 115, 161] Literature Review: 12 studies [33–36, 116–120, 162–164] |

General Mental Health/ Emotional Well-Being: [3, 8, 8, 24, 28, 39, 41, 43, 46, 50, 53, 54, 59, 65, 68, 69, 81, 83, 85, 90, 93, 110–113, 142] Coping: [3, 28, 102, 142, 155] Depression: [15, 28, 38, 64, 84, 94, 98, 102, 109, 122 127, 139, 145] Stress: [4, 25, 28, 38, 98, 154] |

| Social well-being | Quantitative Cross-sectional: 55 studies [2, 3, 5, 7, 8, 12–16, 20–24, 37–42, 46, 48, 49, 53, 54, 56, 57, 59, 60, 62, 66, 67, 69, 73–76, 122–126, 129–132, 134, 135, 138, 165–169] Quantitative Longitudinal: 22 studies [28, 31, 81–84, 88, 90–94, 134, 140–142, 144, 145, 170–173] Qualitative: 25 studies [32, 98–106, 108, 147–152, 154, 156–160, 174, 175] Mixed-Methods: 5 studies [110–114] Literature Review: 10 studies [33–36, 116–118, 163, 164, 176] |

Social Support: [15, 20, 22, 99, 101–104, 110, 114, 125, 135, 149, 150, 152, 154, 156–158] Family: [103, 106, 154] Finances: [4, 28, 32, 99, 101, 104, 106, 110, 132, 172 173] Sexuality: [4, 28, 59, 84, 101, 103, 106] |

| Spiritual well-being | Quantitative Cross-sectional: 22 studies [5, 7, 8, 14, 16, 17, 20, 21, 24, 38–40, 47, 60, 64, 70, 123, 131, 135, 136, 177] Quantitative Longitudinal: 4 studies [28, 81, 94, 142] Qualitative: 24 studies [32, 98–106, 108, 147–150, 152–157, 160, 175, 178] Mixed-Methods: 3 studies [111–113] Literature Review: 6 studies [34, 35, 116, 118, 163, 164] |

Spirituality/ Spiritual Well-Being: [14, 17, 24, 46, 81, 99, 100, 108, 112, 113, 135, 150, 156, 157, 178] Religion: [32, 102, 136, 150, 155, 175] Uncertainty/ Questioning God: [20, 21, 28] Prayer: [32, 64, 70, 94, 98, 106, 149] |

Findings by Health-Related Quality of Life Domain.

Results organized by Ferrell’s HRQOL domains (i.e., psychological, physical, social, and spiritual) are presented in Table 1 and Supplemental Appendix Table 2. We included an additional section labeled Combined “Overall” HRQOL that summarizes studies that included some combination of the four HRQOL domains [14]. In addition to reporting HRQOL patterns among Hispanic/Latino cancer survivors, several studies examined differences in HRQOL between Hispanic/Latino cancer survivors and survivors from other racial/ethnic groups and/or correlates of HRQOL. Such studies are summarized within each HRQOL domain sub-section below. Where applicable, we summarized interventions to improve HRQOL among Latino cancer survivors.

Psychological well-being

Most included studies (143 out of 176 studies) focused on psychological well-being, with 38 studies reporting lower psychological well-being among Hispanics/Latinos compared to other racial/ethnic groups [6, 14–19, 22, 33–61]. Only six studies [62–67] reported similar mental health scores between Hispanics/Latinos cancer survivors and survivors from other racial/ethnic groups, and one study documented better mental health outcomes among less acculturated Hispanic/Latina breast cancer survivors compared to their White counterparts [68].

With a prevalence ranging from 32% [69] to 53% [70], depressive symptoms were the most commonly studied and reported HRQOL measure among Hispanic/Latino cancer survivors. Nine studies examined racial/ethnic differences in reports of depression, of which, six showed higher rates of depression among Hispanics/Latinos compared to non-Hispanics/Latinos [15, 43, 52, 54, 57, 61], while the remaining three studies reported no ethnic differences [71–73]. For example, in a study examining post-treatment symptoms among breast cancer survivors, Hispanics/Latinas reported significantly higher rates of depression compared to non-Hispanic/Latino Whites and Blacks [43]. In contrast, a study examining HRQOL among cervical cancer survivors found no differences in rates of depression between Hispanics/Latinas and non-Hispanic/Latina survivors [73]. Several factors were associated with increased risk for depression among Hispanic/Latino cancer survivors, including lower education, poor physical/social functioning, less social (e.g., family, peer) and emotional support, higher stress, poor body image, poor coping, self-blame, and Spanish language preference [57, 70, 74, 75].

Other commonly studied and reported psychological well-being issues included emotional well-being concerns, distress or anxiety, and fear of recurrence [16–18, 34, 40, 50, 76–78]. Hispanic/Latino cancer survivors consistently reported worse emotional well-being compared to survivors of other racial/ethnic groups [14, 19, 37–39, 47–49, 51, 79, 80]. Of the 12 studies examining fear of cancer recurrence [16–18, 34, 40, 50, 58, 76–78, 81, 82], six reported higher levels of fear among Hispanics/Latinos compared to other racial/ethnic groups [16–18, 34, 40, 50, 78]. In a systematic review of studies on fear of recurrence among survivors of multiple cancers, Hispanic/Latino ethnicity was associated with higher levels of fear of cancer recurrence [18]. Additionally, two studies reported that Hispanics/Latinas with lower levels of acculturation reported the highest level of worry about recurrence compared to Hispanics/Latinas with high levels of acculturation, Black women, and White women [44, 45]. Other psychological HRQOL measures reported/studied among Hispanic/Latino cancer survivors included post-traumatic growth [35, 72, 83]; body image issues [36, 77, 78, 84–86]; stress [73, 87]; sadness [86]; worry about job loss or finances [16, 77, 88], worry about fertility, relationships, treatment effects [16, 22, 36, 51, 56, 84, 89]; neurocognitive performance [76, 90]; fear of social isolation [36]; coping [36, 88, 90–95]; and fatalism [96, 97].

Ten studies tested a variety of interventions to improve psychological well-being among Hispanic/Latino cancer survivors [20, 78, 98–105]. In-person and telephone-based education, as well as counseling and mindfulness-based stress reduction interventions were shown to improve anxiety, depressive symptoms, and psychological HRQOL among breast cancer survivors [78, 98, 101–103].

Physical well-being

A total of 105 studies focused on physical well-being among Hispanic/Latino cancer survivors. Twenty seven studies examined racial/ethnic differences in physical well-being among Hispanic/Latino cancer survivors [6, 14, 37, 38, 41, 42, 47, 53–55, 62–68, 79, 106–114], with 16 of these studies documenting worse physical well-being among Hispanics/Latinos compared to survivors from other racial/ethnic groups [14, 38, 41, 42, 47, 53, 55, 65, 79, 106–110, 113, 114]. For example, two studies examining breast, colorectal, prostate and lung cancer survivors reported lower physical HRQOL scores among Hispanic/Latino survivors compared to other racial/ethnic groups [41, 42]. Acculturation was associated with physical HRQOL, where English proficient Hispanic/Latina breast cancer survivors were more likely than their low English proficient counterparts to report better self-rated physical health [6]. In contrast, eight studies reported no differences in physical HRQOL between Hispanic/Latino survivors and survivors from other racial/ethnic groups [54, 62–64, 66, 67, 111, 112]; while one study documented better physical well-being among less acculturated Hispanic/Latina breast cancer survivors relative to their non-Hispanic/Latina White counterparts [68].

Two studies evaluated racial/ethnic differences in physical functioning with conflicting findings. In a systematic review examining HRQOL among cancer and renal disease patients, Hispanic/Latino men with prostate cancer had significantly worse physical functioning than White men, and had more bowel-related issues than their White and Black counterparts [22]. Yet, in a another study of breast, prostate, colorectal and gynecologic cancer patients, Latino cancer survivors reported higher physical functioning compared to Black and Asian cancer survivors [115].

Other measures of physical well-being reported among Hispanic/Latino cancer survivors included sexual functioning [16, 86, 116, 117], pain [14, 19, 43, 54, 77, 86, 91, 108, 118–122], fatigue [14, 19, 43, 54, 76, 78, 86, 104, 113, 119–121, 123–125], nausea [19, 86, 91, 96, 119, 121, 123], hair loss [19, 49, 86, 91, 123], lymphedema [14, 43], bowel problems [22, 123], and “other symptom bother” [49, 73, 91, 123, 126]. Studies examining racial/ethnic differences in sexual function consistently reported that Latino cancer survivors were more likely to experience adverse sexual function than other racial/ethnic groups [16, 17, 117]. Compared with other racial/ethnic groups, Hispanic/Latino and Black survivors reported worse physical toxicities from treatment [14, 22, 43, 49, 108, 117, 118]. Additionally, in a systematic review of HRQOL among Hispanic/Latina breast cancer patients, Hispanics/Latinas reported higher symptom burden for symptoms such as pain, fatigue and lymphedema [14].

Four studies examining the effect of telephone-based and multi-part interventions (including culturally sensitive health education and interpersonal counseling) on HRQOL among Hispanic/Latino cancer survivors reported significant improvements in physical well-being in intervention groups [20, 101, 104, 127].

Social well-being

One hundred and seventeen studies examined social well-being among Hispanic/Latino cancer survivors. Thirteen studies examined social well-being using a summary score measure (e.g., FACT-G) with nine reporting lower social well-being scores among Hispanics/Latinos compared to other racial/ethnic groups [14, 15, 17, 38, 39, 48, 53, 64, 109]. In a study examining HRQOL among a diverse group of cervical cancer survivors, Spanish-speaking Hispanics/Latinas survivors reported worse social well-being compared to White survivors [39]. In another cohort of multiethnic breast cancer survivors, Hispanics/Latinas reported the lowest scores for social/family well-being when compared to other groups [38]. Social support [16, 19, 36, 40, 50, 61, 63, 73, 76–78, 81, 82, 86, 88, 91–93, 95, 97, 102, 128–145] and financial hardship/job disruption [19, 33, 45, 50, 81, 82, 86, 102, 106, 121, 128, 130, 131, 140, 145–157] were the most commonly reported/studied social well-being measures. Hispanic/Latino cancer survivors reported social support as an important component of dealing with a cancer diagnosis [76–78, 81, 82, 86, 88, 92, 93, 95, 97, 102, 121, 131, 132, 134, 140, 145]. In a study among Hispanic/Latino adolescent and young adult cancer survivors, family communication around cancer and symptoms was reported as beneficial to transitioning these survivors from pediatric to adult-centered survivorship care [132]. While one study reported that Hispanic/Latino cancer survivors mainly sought support from family [21], another study noted that informal social support networks were more helpful to Hispanic/Latino survivors relative to their non-Hispanic/Latino White counterparts [16]. Although social support was strongly endorsed among Hispanic/Latino cancer survivors, several studies reported more adverse social HRQOL outcomes in Hispanic/Latino cancer survivors compared to other racial/ethnic groups, including smaller social support networks / less social support [19, 50, 138], more social avoidance [40], and lower scores on measures of interpersonal relationships [113, 139]. Hispanics/Latinos cancer survivors were also less likely to take part in support groups [135] and report changes in their marital status as a result of a cancer diagnosis [128]. In contrast, one study among cervical cancer patients reported no differences in social support between Hispanic/Latino and non-Hispanic/Latino survivors [73]. Moreover, in one study, while non-Hispanic/Latino Whites perceived more social support than Hispanics/Latinas (mean score of 145.9 vs. 139.0, p = 0.04), Latinas reported slightly higher spousal and familial support [138].

Hispanic/Latino cancer survivors more commonly reported job disruptions and financial hardship after their cancer diagnosis [33, 50, 128, 147–152, 157]. For example, in a study examining correlates of paid work after breast cancer diagnosis, Hispanic/Latina breast cancer survivors were more likely than Whites to stop working after a diagnosis [151]. However, another study examining factors associated with returning to work noted that there were no significant differences in job retention between Hispanic/Latino cancer survivors and Whites, although job retention was associated with acculturation [146]. Yet, another study found that Hispanic/Latino cancer survivors were more likely to return to work than White survivors [106]. Financial hardship or loss was also more prevalent among Hispanic/Latino cancer survivors compared to other racial/ethnic groups, with the exception of Blacks [86, 148, 149, 152, 157]. Other social HRQOL concerns reported among Hispanic/Latino cancer survivors included sexual health and sexuality (e.g., the negative effect of diagnosis on enjoying sex) [46, 71, 77, 84, 122, 142, 145].

Spiritual well-being

Fifty-nine studies examined spiritual well-being among Hispanic/Latino cancer survivors, and documented a range of religious/spiritual practices for coping with cancer, including: prayer [92, 111, 123, 158], faith [21, 36, 77, 84, 159, 160], finding meaning and peace [61, 143], religious/church attendance [158], and relationship with God [22, 47, 63, 64, 94, 111, 159–162]. Hispanic/Latino survivors commonly reported spirituality as a source of strength [78, 86, 93, 101] and comfort [47, 161]. The 15 studies [16, 22, 47, 61, 63, 64, 94, 111, 130, 143, 159–163] examining racial/ethnic differences in spiritual well-being generally showed that compared to other racial/ethnic groups, Hispanic/Latino and Black cancer survivors were more likely to use spirituality as a coping strategy [22, 61, 64, 94, 143, 160, 162]. In a study among patients with hematological diseases and brain tumors, compared with non-Hispanics/Latinos, Hispanic/Latino survivors reported higher spiritual well-being scores [162]. In contrast, a study examining HRQOL among survivors of childhood cancers showed no statistically significant difference in spiritual well-being among Hispanics/Latinos and non-Hispanic/Latino Whites [63]. Spirituality/religious coping was associated with other aspects of HRQOL among Hispanic/Latino cancer survivors [83, 158, 163], including lower anxiety, fatigue, and depression [158], better functional well-being [163], and less depression [61].

Combined “Overall” HRQOL

Thirty-seven studies reported on overall HRQOL domains among Hispanic/Latino cancers survivors, highlighting racial/ethnic differences between Hispanics/Latinos and other groups [8, 14, 15, 22, 39, 57, 65, 73, 75, 110, 162, 164–170]. In a multiethnic cohort of women with breast cancer, Hispanic/Latino ethnicity was associated with worse overall HRQOL compared to Black survivors [164]. Another study of HRQOL among prostate cancer patients reported lower overall HRQOL among Hispanic/Latino and Black men relative to other racial/ethnic groups [22]. However, a study among cervical cancer survivors reported no differences in overall HRQOL between Hispanics/Latinas and non-Hispanics/Latinas [73]. In terms of correlates of HRQOL, greater acculturation, shame, and stigma were negatively associated with overall HRQOL, while more physical activity, inner peace, and better physical, social, psychological and functional well-being were positively associated with overall HRQOL among Hispanic/Latino cancer survivors [6, 57, 75, 110, 144, 163, 166–168].

Four studies documented efficacy of culturally sensitive education and counseling interventions, as well as patient navigation in improving overall HRQOL among Hispanic/Latino cancer patients [20, 78, 127, 171].

Discussion

In this systematic review, we synthesized evidence on HRQOL experiences and needs among Hispanic/Latino cancer survivors, from the time of cancer diagnosis until death. Evidence from our review suggests that HRQOL needs are high among Hispanic/Latino cancer survivors. In particular, Hispanics/Latinos reported worse psychological well-being (e.g., depression, anxiety, fear of recurrence) and suboptimal physical well-being (e.g., pain, nausea, sexual dysfunction) relative to their counterparts. In terms of social well-being, although Hispanic/Latino survivors commonly endorse preferences for family support and social network involvement during care, several studies reported lower social well-being and more job disruptions/financial hardship among Hispanics/Latinos relative to non-Hispanic/Latino Whites. In contrast, reports of spiritual well-being and spirituality-based coping were high among Hispanic/Latino cancer survivors.

Fewer studies evaluated HRQOL interventions; however, culturally responsive education and counseling were the most commonly tested interventions with demonstrated efficacy in improving HRQOL. However, given the extent of HRQOL needs in Hispanic/Latino cancer survivors, there is an urgent need for more systematic and tailored interventions to address the HRQOL needs of this growing and underrepresented segment of the cancer survivor population. In terms of potential intervention targets, previous research has documented racial/ethnic differences in clinicians’ assessment of patients’ symptoms, with clinicians being less likely to assess and accurately estimate HRQOL symptom burden in patients of color relative to Whites [172–175]. Uneven clinician screening of patients for HRQOL/symptom burden likely contributes to inequities in supportive care service access and delivery, including medication prescribing, and referrals to supportive care specialists (e.g., psychiatry, pain specialist, physical therapy). Although distress screening has been an American College of Surgeons accreditation standard for cancer centers since 2015 [176], recent evidence suggests that the uptake and dissemination of distress screening has been limited in some settings, including National Cancer Institute-designated cancer centers [177]. Thus, efforts to improve HRQOL among Hispanic/Latino cancer survivors must include broader uptake of routine symptom and distress screening for HRQOL issues and supportive care needs, especially depression/anxiety, physical symptoms (e.g., pain, sexual dysfunction, bowel issues), job loss and financial hardship, social support, and spiritual coping. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCNN) Distress Thermometer and Problem List is a helpful tool for quickly assessing both patient distress and a range of HRQOL concerns that closely align with the four HRQOL domains examined in this review [178]. The NCCN distress screening tool has been translated/adapted for Spanish-speakers which is important in this population due to heterogeneity in acculturation, English proficiency, and Spanish language preference. Furthermore, routine monitoring of symptom distress and HRQOL needs can be facilitated through the use of health information technology (e.g., electronic patient-reported outcome [ePRO] systems), where symptom distress and HRQOL needs can be addressed in real-time and tracked across visits. Prior studies have demonstrated the feasibility, acceptability, and efficacy of symptom monitoring through implementation of ePRO systems in routine oncology care [179], but feasibility/acceptability/efficacy testing needs to be expanded to more diverse cancer patient populations, including Hispanics/Latinos.

Moreover, addressing the HRQOL needs of Hispanic/Latino cancer survivors requires consideration of the unique cultural and linguistic needs of this patient population, as well as the current social and political context surrounding the lived experience of Hispanics/Latinos in America, where high uninsurance rates (19% of Hispanics/Latinos remain uninsured [180]) and rising anti-immigrant and xenophobic sentiments [181] continue to threaten the health and well-being of the Hispanic/Latino community. Specifically, clinicians should recognize that the socio-political context in which Hispanics/Latinos in America live may further exacerbate psychological distress and other HRQOL issues in many Hispanic/Latino survivors and hinder some from seeking and receiving critical follow-up care to address these needs. To advance equity in supportive care for Hispanic/Latino cancer survivors, it is important for cancer centers to provide culturally and linguistically appropriate supportive care services that include medical interpreters as a standard of care [182], support family/social network involvement in decision-making [182], account for patients’ spiritual care needs in care planning [182], and acknowledge and address, where possible, the broader societal stressors (e.g., discrimination, financial hardship, job loss) that may affect Hispanic/Latino survivors’ HRQOL and their engagement with the cancer care system.

While this systematic review resulted in over 150 articles meeting inclusion criteria, there are some limitations of the included studies that are worth noting. First, our study was limited to Latinos/Hispanics in the US context, where anti-immigration sentiments and health care coverage challenges remain key concerns for this subset of the cancer survivor population. Thus, our findings may not generalize to Latinos/Hispanic cancer survivors in other countries, especially countries where health care and immigration policies are more inclusive. Second, men were vastly underrepresented, with roughly a quarter of studies including men in their study sample and only two studies solely focused on men [82, 117]. Overrepresentation of women across studies potentially limits generalizability of our findings to men, which precludes efforts to understand and address gender-specific HRQOL needs among Hispanic/Latino men with cancer. Additionally, few studies presented results stratified by Hispanic/Latino subgroups (e.g., Mexican vs. Puerto Rican vs. Venezuelan), thereby overlooking possible heterogeneity in HRQOL needs among Hispanics/Latinos from different countries of origin [183]. Most studies also focused on patients with earlier stage diagnoses, but no study evaluated HRQOL needs of Hispanics/Latinos with metastatic disease or those near the end of life (EOL), when HRQOL needs are known to be greater. In terms of representation of HRQOL domains across studies, relatively few studies evaluated the social and spiritual aspects of HRQOL among Hispanics/Latinos. Finally, the majority of included studies involved a cross-sectional observational study design (90 out of 176 studies were cross-sectional; 35 out of 176 were longitudinal) which hinders identification of changes in HRQOL needs overtime, critical time frames for intervention, and effective strategies for enhancing HRQOL in this population. Future research on HRQOL among Latino cancer survivors should place greater emphasis on exploring the experiences of Latino cancer survivors in countries outside the USA, recruiting more men into studies, evaluating HRQOL needs during metastatic and EOL disease cases, stratifying data by Latino subgroup, including measures of social and spiritual HRQOL, and incorporating longitudinal and intervention study designs, where possible.

Conclusion

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review to examine domain-specific HRQOL concerns and issues among Hispanic/Latino cancer survivors at different phases of the cancer care continuum, from cancer diagnosis to death. There is overwhelming evidence pointing to significant HRQOL needs among Hispanic/Latino survivors, including depression/anxiety, decrements in physical function, job loss and financial hardship. Routine assessment of HRQOL needs in clinical practice, as well as culturally and linguistically responsive approaches to supportive cancer care hold much promise for enhancing HRQOL outcomes in this growing segment of the cancer survivor population.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Cancer Institute (1 K01CA218473-01A1 to C.A.S). Olive M. Mbah is supported by the National Cancer Institute’s National Research Service Award sponsored by the Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center at the University of North Carolina (T32 CA116339).

Conflict of interest

Dr. Cleo A. Samuel reports research funding from National Cancer Institute and Pfizer for work unrelated to this review. All other authors do not have any conflicts of interest to disclose.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material The online version of this article (https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-020-02527-0) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

References

- 1.Miller KD, Goding Sauer A, Ortiz AP, Fedewa SA, Pinheiro PS, Tortolero-Luna G, et al. (2018). Cancer Statistics for Hispanics/Latinos 2018. CA: A Cancer Journal of Clinicians, 68(6), 425–445. 10.3322/caac.21494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Cancer Society. (2018). Cancer facts & figures for Hispanics/Latinos 2018–2020. Atlanta: American Cancer Society, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pinheiro PS, Sherman RL, Trapido EJ, Fleming LE, Huang Y, Gomez-Marin O, et al. (2009). Cancer incidence in first generation US Hispanics: Cubans, Mexicans, Puerto Ricans, and new Latinos. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers Prevention, 18(8), 2162–2169. 10.1158/1055-9965.epi-09-0329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pinheiro PS, Callahan KE, Stern MC, & de Vries E (2018). Migration from Mexico to the United States: A high-speed cancer transition. International Journal of Cancer, 142(3), 477–488. 10.1002/ijc.31068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vélez L, Chalela P, & Ramirez A (2008). Hispanic/Latino health and disease: An overview. Health Promotion in Multicultural Populations: A Handbook for Practitioners and Students. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Garcia-Jimenez M, Santoyo-Olsson J, Ortiz C, Lahiff M, Sokal-Gutierrez K, & Napoles AM (2014). Acculturation, inner peace, cancer self-efficacy, and self-rated health among Latina breast cancer survivors. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 25(4), 1586–1602. 10.1353/hpu.2014.0158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kagawa-Singer M (1995). Socioeconomic and cultural influences on cancer care of women. Seminars in Oncology Nursing, 11(2), 109–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Medeiros EA, Castaneda SF, Gonzalez P, Rodriguez B, Buelna C, West D, et al. (2015). Health-related quality of life among cancer survivors attending support Groups. Journal of Cancer Education, 30(3), 421–427. 10.1007/s13187-014-0697-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baker DW, Hayes R, & Fortier JP (1998). Interpreter use and satisfaction with interpersonal aspects of care for Spanish-speaking patients. Medical Care, 36(10), 1461–1470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Akincigil A, Olfson M, Siegel M, Zurlo KA, Walkup JT, & Crystal S (2012). Racial and ethnic disparities in depression care in community-dwelling elderly in the United States. American Journal of Public Health, 102(2), 319–328. 10.2105/ajph.2011.300349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alegria M, Canino G, Rios R, Vera M, Calderon J, Rusch D, et al. (2002). Inequalities in use of specialty mental health services among Latinos, African Americans, and non-Latino whites. Psychiatric Services (Washington, DC)., 53(12), 1547–1555. 10.1176/appi.ps.53.12.1547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alegria M, Chatterji P, Wells K, Cao Z, Chen CN, Takeuchi D, et al. (2008). Disparity in depression treatment among racial and ethnic minority populations in the United States. Psychiatric Services (Washington, DC)., 59(11), 1264–1272. 10.1176/appi.ps.59.11.1264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lagomasino IT, Stockdale SE, & Miranda J (2011). Racial-ethnic composition of provider practices and disparities in treatment of depression and anxiety, 2003–2007. Psychiatric Services (Washington, DC), 62(9), 1019–1025. 10.1176/appi.ps.62.9.1019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yanez B, Thompson EH, & Stanton AL (2011). Quality of life among Latina breast cancer patients: A systematic review of the literature. Journal of Cancer Survivorship, 5(2), 191–207. 10.1007/s11764-011-0171-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Luckett T, Goldstein D, Butow PN, Gebski V, Aldridge LJ, McGrane J, et al. (2011). Psychological morbidity and quality of life of ethnic minority patients with cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Oncology, 12(13), 1240–1248. 10.1016/s1470-2045(11)70212-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aziz NM, & Rowland JH (2002). Cancer survivorship research among ethnic minority and medically underserved groups. Oncology Nursing Forum, 29(5), 789–801. 10.1188/02.onf.789-801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Blinder VS, & Griggs JJ (2013). Health disparities and the cancer survivor. Seminars in Oncology, 40(6), 796–803. 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2013.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koch L, Jansen L, Brenner H, & Arndt V (2013). Fear of recurrence and disease progression in long-term (%3e/= 5 years) cancer survivors: A systematic review of quantitative studies. Psychooncology., 22(1), 1–11. 10.1002/pon.3022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lopez-Class M, Gomez-Duarte J, Graves K, & Ashing-Giwa K (2012). A contextual approach to understanding breast cancer survivorship among Latinas. Psychooncology., 21(2), 115–124. 10.1002/pon.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McNulty J, Kim W, Thurston T, Kim J, & Larkey L (2016). Interventions to improve quality of life, well-being, and care in latino cancer survivors: A systematic literature review. Oncology Nursing Forum, 43(3), 374–384. 10.1188/16.onf.374-384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pfaendler KS, Wenzel L, Mechanic MB, & Penner KR (2015). Cervical cancer survivorship: Long-term quality of life and social support. Clinical Therapeutics, 37(1), 39–48. 10.1016/j.clinthera.2014.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang J, Sallfrank MF, Hong SH, Liu C, & Gourley DR (2007). Patterns of reporting health-related quality of life across racial and ethnic groups. Expert Review of Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research, 7(2), 177–186. 10.1586/14737167.7.2.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yoo GJ, Levine EG, & Pasick R (2014). Breast cancer and coping among women of color: A systematic review of the literature. Supportive Care in Cancer, 22(3), 811–824. 10.1007/s00520-013-2057-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ferrell BR, Dow KH, & Grant M (1995). Measurement of the quality of life in cancer survivors. Quality of Life Research, 4(6), 523–531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Burhansstipanov L, Dignan M, Jones KL, Krebs LU, Marchionda P, & Kaur JS (2012). Comparison of quality of life between Native and non-Native cancer survivors: Native and non-Native cancer survivors’ QOL. Journal of Cancer Education, 27(1 Suppl), S106–S113. 10.1007/s13187-012-0318-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Samuel CA, Pinheiro LC, Reeder-Hayes KE, Walker JS, Corbie-Smith G, Fashaw SA, et al. (2016). To be young, Black, and living with breast cancer: A systematic review of health-related quality of life in young Black breast cancer survivors. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment, 160(1), 1–15. 10.1007/s10549-016-3963-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.American Cancer Society. (2014). Life after cancer: Survivorship by the numbers. Atlanta: American Cancer Society, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cho J, Jung SY, Lee JE, Shim EJ, Kim NH, Kim Z, et al. (2014). A review of breast cancer survivorship issues from survivors’ perspectives. Journal of Breast Cancer, 17(3), 189–199. 10.4048/jbc.2014.17.3.189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.U.S. Office of Management and Budget; United States Census Bureau. Hispanic Origin. 2019. Retrieved July 2, 2019.

- 30.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gotzsche PC, & Vandenbroucke JP (2008). The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 61(4), 344–349. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Critical Appraisal Skills Program. CASP Qualitative Checklist. (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mollica M, Nemeth L, Newman SD, & Mueller M (2015). Quality of life in African American Breast Cancer Survivors: An integrative literature review. Cancer Nursing, 38(3), 194–204. 10.1097/ncc.0000000000000160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bowen DJ, Alfano CM, McGregor BA, Kuniyuki A, Bernstein L, Meeske K, et al. (2007). Possible socioeconomic and ethnic disparities in quality of life in a cohort of breast cancer survivors. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment, 106(1), 85–95. 10.1007/s10549-006-9479-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Blinder VS, Murphy MM, Vahdat LT, Gold HT, de Melo-Martin I, Hayes MK, et al. (2012). Employment after a breast cancer diagnosis: A qualitative study of ethnically diverse urban women. Journal of Community Health, 37(4), 763–772. 10.1007/s10900-011-9509-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Arpawong TE, Oland A, Milam JE, Ruccione K, & Meeske KA (2013). Post-traumatic growth among an ethnically diverse sample of adolescent and young adult cancer survivors. Psychooncology, 22(10), 2235–2244. 10.1002/pon.3286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ashing-Giwa KT, Kagawa-Singer M, Padilla GV, Tejero JS, Hsiao E, Chhabra R, et al. (2004). The impact of cervical cancer and dysplasia: A qualitative, multiethnic study. Psychooncology, 13(10), 709–728. 10.1002/pon.785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ashing-Giwa KT, & Lim JW (2011). Examining emotional outcomes among a multiethnic cohort of breast cancer survivors. Oncology Nursing Forum, 38(3), 279–288. 10.1188/11.onf.279-288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ashing-Giwa KT, Tejero JS, Kim J, Padilla GV, & Hellemann G (2007). Examining predictive models of HRQOL in a population-based, multiethnic sample of women with breast carcinoma. Quality of Life Research, 16(3), 413–428. 10.1007/s11136-006-9138-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ashing-Giwa KT, Tejero JS, Kim J, Padilla GV, Kagawa-Singer M, Tucker MB, et al. (2009). Cervical cancer survivorship in a population based sample. Gynecologic Oncology, 112(2), 358–364. 10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Carver CS, Smith RG, Petronis VM, & Antoni MH (2006). Quality of life among long-term survivors of breast cancer: Different types of antecedents predict different classes of outcomes. Psychooncology, 15(9), 749–758. 10.1002/pon.1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Clauser SB, Arora NK, Bellizzi KM, Haffer SC, Topor M, & Hays RD (2008). Disparities in HRQOL of cancer survivors and non-cancer managed care enrollees. Health Care and Finance Review, 29(4), 23–40. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Connor AE, Baumgartner RN, Pinkston CM, Boone SD, & Baumgartner KB (2016). Obesity, ethnicity, and quality of life among breast cancer survivors and women without breast cancer: The long-term quality of life follow-up study. Cancer Causes and Control, 27(1), 115–124. 10.1007/s10552-015-0688-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Eversley R, Estrin D, Dibble S, Wardlaw L, Pedrosa M, & Favila-Penney W (2005). Post-treatment symptoms among ethnic minority breast cancer survivors. Oncology Nursing Forum, 32(2), 250–256. 10.1188/05.onf.250-256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Janz NK, Hawley ST, Mujahid MS, Griggs JJ, Alderman A, Hamilton AS, et al. (2011). Correlates of worry about recurrence in a multiethnic population-based sample of women with breast cancer. Cancer, 117(9), 1827–1836. 10.1002/cncr.25740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Janz NK, Li Y, Beesley LJ, Wallner LP, Hamilton AS, Morrison RA, et al. (2016). Worry about recurrence in a multi-ethnic population of breast cancer survivors and their partners. Supportive Care in Cancer, 24(11), 4669–4678. 10.1007/s00520-016-3314-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Knobf MT, Ferrucci LM, Cartmel B, Jones BA, Stevens D, Smith M, et al. (2012). Needs assessment of cancer survivors in Connecticut. Journal of Cancer Survivorship, 6(1), 1–10. 10.1007/s11764-011-0198-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lim JW, Gonzalez P, Wang-Letzkus MF, & Ashing-Giwa KT (2009). Understanding the cultural health belief model influencing health behaviors and health-related quality of life between Latina and Asian-American breast cancer survivors. Supportive Care in Cancer, 17(9), 1137–1147. 10.1007/s00520-008-0547-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Meeske KA, Patel SK, Palmer SN, Nelson MB, & Parow AM (2007). Factors associated with health-related quality of life in pediatric cancer survivors. Pediatric Blood & Cancer, 49(3), 298–305. 10.1002/pbc.20923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Munoz AR, Kaiser K, Yanez B, Victorson D, Garcia SF, Snyder MA, et al. (2016). Cancer experiences and health-related quality of life among racial and ethnic minority survivors of young adult cancer: A mixed methods study. Supportive Care in Cancer, 24(12), 4861–4870. 10.1007/s00520-016-3340-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pandya DM, Patel S, Ketchum NS, Pollock BH, & Padmanabhan S (2011). A comparison of races and leukemia subtypes among patients in different cancer survivorship phases. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk., 11(Suppl 1), S114–S118. 10.1016/j.clml.2011.05.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pinheiro LC, Wheeler SB, Chen RC, Mayer DK, Lyons JC, & Reeve BB (2015). The effects of cancer and racial disparities in health-related quality of life among older Americans: A case–control, population-based study. Cancer, 121(8), 1312–1320. 10.1002/cncr.29205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wu C, Ashing KT, Jones VC, & Barcelo L (2017). The association of neighborhood context with health outcomes among ethnic minority breast cancer survivors. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 10.1007/s10865-017-9875-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ashing KT, George M, & Jones V (2018). Health-related quality of life and care satisfaction outcomes: Informing psychosocial oncology care among Latina and African-American young breast cancer survivors. Psychooncology, 27(4), 1213–1220. 10.1002/pon.4650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bevilacqua LA, Dulak D, Schofield E, Starr TD, Nelson CJ, Roth AJ, et al. (2018). Prevalence and predictors of depression, pain, and fatigue in older- versus younger-adult cancer survivors. Psychooncology., 27(3), 900–907. 10.1002/pon.4605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Olagunju TO, Liu Y, Liang LJ, Stomber JM, Griggs JJ, Ganz PA, et al. (2018). Disparities in the survivorship experience among Latina survivors of breast cancer. Cancer, 124(11), 2373–2380. 10.1002/cncr.31342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Papaleontiou M, Reyes-Gastelum D, Gay BL, Ward KC, Hamilton AS, Hawley ST, et al. (2019). Worry in thyroid cancer survivors with a favorable prognosis. Thyroid, 29(8), 1080–1088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ritt-Olson A, Miller K, Baezconde-Garbanati L, Freyer D, Ramirez C, Hamilton A, et al. (2018). Depressive symptoms and quality of life among adolescent and young adult cancer survivors: Impact of gender and Latino culture. Journal of adolescent and young adult oncology., 7(3), 384–388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Séguin Leclair C, Lebel S, & Westmaas JL (2019). The relationship between fear of cancer recurrence and health behaviors: A nationwide longitudinal study of cancer survivors. Health Psychology, 38(7), 596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.StGeorge SM, Noriega Esquives B, Agosto Y, Kobayashi M, Leite R, Vanegas D, et al. (2020). Development of a multigenerational digital lifestyle intervention for women cancer survivors and their families. Psycho-Oncology, 29(1), 182–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Young K, Shliakhtsitsava K, Natarajan L, Myers E, Dietz AC, Gorman JR, et al. (2019). Fertility counseling before cancer treatment and subsequent reproductive concerns among female adolescent and young adult cancer survivors. Cancer, 125(6), 980–989. 10.1002/cncr.31862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yu Q, Medeiros KL, Wu X, & Jensen RE (2018). Non-linear predictive models for multiple mediation analysis: With an application to explore ethnic disparities in anxiety and depression among cancer survivors. Psychometrika, 83(4), 991–1006. 10.1007/s11336-018-9612-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Reyes ME, Ye Y, Zhou Y, Liang A, Kopetz S, Rodriquez MA, et al. (2017). Predictors of health-related quality of life and association with survival may identify colorectal cancer patients at high risk of poor prognosis. Quality of Life Research, 26(2), 319–330. 10.1007/s11136-016-1381-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Casillas JN, Zebrack BJ, & Zeltzer LK (2006). Health-related quality of life for Latino survivors of childhood cancer. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology, 24(3), 125–145. 10.1300/J077v24n03_06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bloom JR, Stewart SL, Napoles AM, Hwang ES, Livaudais JC, Karliner L, et al. (2013). Quality of life of Latina and Euro-American women with ductal carcinoma in situ. Psychooncology, 22(5), 1008–1016. 10.1002/pon.3098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Castellino SM, Casillas J, Hudson MM, Mertens AC, Whitton J, Brooks SL, et al. (2005). Minority adult survivors of childhood cancer: A comparison of long-term outcomes, health care utilization, and health-related behaviors from the childhood cancer survivor study. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 23(27), 6499–6507. 10.1200/jco.2005.11.098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Pakiz B, Ganz PA, Sedjo RL, Flatt SW, Demark-Wahnefried W, Liu J, et al. (2016). Correlates of quality of life in overweight or obese breast cancer survivors at enrollment into a weight loss trial. Psychooncology, 25(2), 142–149. 10.1002/pon.3820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Goldfarb M, & Casillas J (2016). Thyroid cancer-specific quality of life and health-related quality of life in young adult thyroid cancer survivors. Thyroid, 26(7), 923–932. 10.1089/thy.2015.0589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Maly RC, Liu Y, Liang LJ, & Ganz PA (2014). Quality of life over 5 years after a breast cancer diagnosis among low-income women: Effects of race/ethnicity and patient-physician communication. Cancer, 121(6), 916–926. 10.1002/cncr.29150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Holden AE, Ramirez AG, & Gallion K (2014). Depressive symptoms in Latina breast cancer survivors: A barrier to cancer screening. Health Psychology, 33(3), 242–248. 10.1037/a0032685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ashing-Giwa K, Rosales M, Lai L, & Weitzel J (2013). Depressive symptomatology among Latina breast cancer survivors. Psychooncology, 22(4), 845–853. 10.1002/pon.3084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Christie KM, Meyerowitz BE, & Maly RC (2010). Depression and sexual adjustment following breast cancer in low-income Hispanic and non-Hispanic White women. Psychooncology, 19(10), 1069–1077. 10.1002/pon.1661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Foley KL, Farmer DF, Petronis VM, Smith RG, McGraw S, Smith K, et al. (2006). A qualitative exploration of the cancer experience among long-term survivors: Comparisons by cancer type, ethnicity, gender, and age. Psychooncology, 15(3), 248–258. 10.1002/pon.942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Osann K, Hsieh S, Nelson EL, Monk BJ, Chase D, Cella D, et al. (2014). Factors associated with poor quality of life among cervical cancer survivors: Implications for clinical care and clinical trials. Gynecologic Oncology, 135(2), 266–272. 10.1016/j.ygyno.2014.08.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Aguado Loi CX, Baldwin JA, McDermott RJ, McMillan S, Martinez Tyson D, Yampolskaya S, et al. (2013). Risk factors associated with increased depressive symptoms among Latinas diagnosed with breast cancer within 5 years of survivorship. Psychooncology, 22(12), 2779–2788. 10.1002/pon.3357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Tobin J, Miller KA, Baezconde-Garbanati L, Unger JB, Hamilton AS, Milam JE, et al. (2018). Acculturation, mental health, and quality of life among hispanic childhood cancer survivors: A latent class analysis. Ethnicity & Disease, 28(1), 55–60. 10.18865/ed.28.1.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ceballos RM, Molina Y, Malen RC, Ibarra G, Escareno M, & Marchello N (2015). Design, development, and feasibility of a spanish-language cancer survivor support group. Supportive Care in Cancer, 23(7), 2145–2155. 10.1007/s00520-014-2549-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ashing-Giwa KT, Padilla GV, Bohorquez DE, Tejero JS, Garcia M, & Meyers EA (2006). Survivorship: A qualitative investigation of Latinas diagnosed with cervical cancer. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology, 24(4), 53–88. 10.1300/J077v24n04_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Juarez G, Hurria A, Uman G, & Ferrell B (2013). Impact of a bilingual education intervention on the quality of life of Latina breast cancer survivors. Oncology Nursing Forum, 40(1), E50–60. 10.1188/13.onf.e50-e60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Giedzinska AS, Meyerowitz BE, Ganz PA, & Rowland JH (2004). Health-related quality of life in a multiethnic sample of breast cancer survivors. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 28(1), 39–51. 10.1207/s15324796abm2801_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ashing-Giwa KT, & Lim JW (2009). Examining the impact of socioeconomic status and socioecologic stress on physical and mental health quality of life among breast cancer survivors. Oncology Nursing Forum, 36(1), 79–88. 10.1188/09.onf.79-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Borrayo EA, Scott KL, Drennen A, Bendriss TM, Kilbourn KM, & Valverde P (2020). Treatment challenges and support needs of underserved Hispanic patients diagnosed with lung cancer and head-and-neck cancer. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology, 2020, 1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Sommariva S, Vázquez-Otero C, Medina-Ramirez P, Aguado Loi C, Fross M, Dias E, et al. (2019). Hispanic male cancer survivors’ coping strategies. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 41(2), 267–284. 10.1177/0739986319840658. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Tobin J, Allem JP, Slaughter R, Unger JB, Hamilton AS, & Milam JE (2017). Posttraumatic growth among childhood cancer survivors: Associations with ethnicity, acculturation, and religious service attendance. Journal of Psychological Oncology., 2017, 1–14. 10.1080/07347332.2017.1365799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ashing-Giwa KT, Padilla GV, Bohorquez DE, Tejero JS, & Garcia M (2006). Understanding the breast cancer experience of Latina women. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology, 24(3), 19–52. 10.1300/J077v24n03_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Buki LP, Reich M, & Lehardy EN (2016). “Our organs have a purpose”: body image acceptance in Latina breast cancer survivors. Psychooncology, 25(11), 1337–1342. 10.1002/pon.4270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Fatone AM, Moadel AB, Foley FW, Fleming M, & Jandorf L (2007). Urban voices: the quality-of-life experience among women of color with breast cancer. Palliat Support Care, 5(2), 115–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Martinez Tyson DD, Jacobsen P, & Meade CD (2016). Understanding the stress management needs and preferences of Latinas undergoing chemotherapy. Journal of Cancer Education, 31(4), 633–639. 10.1007/s13187-015-0844-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Phillips F, & Jones BL (2014). Understanding the lived experience of Latino adolescent and young adult survivors of childhood cancer. Journal of Cancer Survivorship, 8(1), 39–48. 10.1007/s11764-013-0310-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Costas-Muniz R, Hunter-Hernandez M, Garduno-Ortega O, Morales-Cruz J, & Gany F (2017). Ethnic differences in psychosocial service use among non-Latina white and Latina breast cancer survivors. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology, 35(4), 424–437. 10.1080/07347332.2017.1310167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Ayala-Feliciano M, Pons-Valerio JJ, Pons-Madera J, & Acevedo SF (2011). The relationship between visuospatial memory and coping strategies in breast cancer survivors. Breast Cancer (Auckland), 5, 117–130. 10.4137/bcbcr.s6957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Banas JR, Victorson D, Gutierrez S, Cordero E, Guitleman J, & Haas N (2017). Developing a peer-to-peer mhealth application to connect Hispanic cancer patients. Journal of Cancer Education, 32(1), 158–165. 10.1007/s13187-016-1066-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Campesino M (2009). Exploring perceptions of cancer care delivery among older Mexican American adults. Oncology Nursing Forum, 36(4), 413–420. 10.1188/09.onf.413-420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Carrion IV, Nedjat-Haiem F, Macip-Billbe M, & Black R (2017). “I Told Myself to Stay Positive” perceptions of coping among Latinos with a cancer diagnosis living in the United States. American Journal of Hospital Palliative Care, 34(3), 233–240. 10.1177/1049909115625955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Gonzalez P, Nunez A, Wang-Letzkus M, Lim JW, Flores KF, & Napoles AM (2016). Coping with breast cancer: Reflections from Chinese American, Korean American, and Mexican American women. Health Psychology, 35(1), 19–28. 10.1037/hea0000263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Jones BL, Volker DL, Vinajeras Y, Butros L, Fitchpatrick C, & Rossetto K (2010). The meaning of surviving cancer for Latino adolescents and emerging young adults. Cancer Nursing, 33(1), 74–81. 10.1097/NCC.0b013e3181b4ab8f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Buki LP, Garces DM, Hinestrosa MC, Kogan L, Carrillo IY, & French B (2008). Latina breast cancer survivors’ lived experiences: Diagnosis, treatment, and beyond. Culture Diversity Ethnic Minor Psychology, 14(2), 163–167. 10.1037/1099-9809.14.2.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Livaudais JC, Thompson B, Godina R, Islas I, Ibarra G, & Coronado GD (2010). A qualitative investigation of cancer survivorship experiences among rural Hispanics. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology, 28(4), 361–380. 10.1080/07347332.2010.488146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Ashing K, & Rosales M (2014). A telephonic-based trial to reduce depressive symptoms among Latina breast cancer survivors. Psychooncology, 23(5), 507–515. 10.1002/pon.3441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Hughes DC, Leung P, & Naus MJ (2008). Using single-system analyses to assess the effectiveness of an exercise intervention on quality of life for Hispanic breast cancer survivors: A pilot study. Social Work in Health Care, 47(1), 73–91. 10.1080/00981380801970871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Molina Y, Thompson B, Espinoza N, & Ceballos R (2013). Breast cancer interventions serving US-based Latinas: current approaches and directions. Womens Health (London), 9(4), 335–348. 10.2217/whe.13.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Badger TA, Segrin C, Hepworth JT, Pasvogel A, Weihs K, & Lopez AM (2013). Telephone-delivered health education and interpersonal counseling improve quality of life for Latinas with breast cancer and their supportive partners. Psychooncology, 22(5), 1035–1042. 10.1002/pon.3101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Badger TA, Segrin C, Sikorskii A, Pasvogel A, Weihs K, Lopez AM, et al. (2020). Randomized controlled trial of supportive care interventions to manage psychological distress and symptoms in Latinas with breast cancer and their informal caregivers. Psychology & Health, 35(1), 87–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Elimimian E, Elson L, Bilani N, Farrag SE, Dwivedi AK, Pasillas R, et al. (2020). Long-term effect of a nonrandomized psychosocial mindfulness-based intervention in Hispanic/Latina breast cancer survivors. Integratvie Cancer Theraphy, 19, 1534735419890682. 10.1177/1534735419890682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Napoles AM, Santoyo-Olsson J, Chacon L, Stewart AL, Dixit N, & Ortiz C (2019). Feasibility of a mobile phone app and telephone coaching survivorship care planning program among Spanish-speaking breast cancer survivors. JMIR Cancer, 5(2), e13543. 10.2196/13543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Yanez B, Oswald LB, Baik SH, Buitrago D, Iacobelli F, Perez-Tamayo A, et al. (2020). Brief culturally informed smartphone interventions decrease breast cancer symptom burden among Latina breast cancer survivors. Psycho-Oncology, 29(1), 195–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Clarke TC, Christ SL, Soler-Vila H, Lee DJ, Arheart KL, Prado G, et al. (2015). Working with cancer: Health and employment among cancer survivors. Annals of Epidemiology, 25(11), 832–838. 10.1016/j.annepidem.2015.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Ashing-Giwa KT, Lim JW, & Gonzalez P (2010). Exploring the relationship between physical well-being and healthy lifestyle changes among European- and Latina-American breast and cervical cancer survivors. Psychooncology, 19(11), 1161–1170. 10.1002/pon.1687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Fu OS, Crew KD, Jacobson JS, Greenlee H, Yu G, Campbell J, et al. (2009). Ethnicity and persistent symptom burden in breast cancer survivors. Journal of Cancer Survivorship, 3(4), 241–250. 10.1007/s11764-009-0100-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Janz NK, Mujahid MS, Hawley ST, Griggs JJ, Alderman A, Hamilton AS, et al. (2009). Racial/ethnic differences in quality of life after diagnosis of breast cancer. Journal of Cancer Survivorship, 3(4), 212–222. 10.1007/s11764-009-0097-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Paxton RJ, Phillips KL, Jones LA, Chang S, Taylor WC, Courneya KS, et al. (2012). Associations among physical activity, body mass index, and health-related quality of life by race/ethnicity in a diverse sample of breast cancer survivors. Cancer, 118(16), 4024–4031. 10.1002/cncr.27389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Ross LE, Hall IJ, Fairley TL, Taylor YJ, & Howard DL (2008). Prayer and self-reported health among cancer survivors in the United States, National Health Interview Survey, 2002. Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, 14(8), 931–938. 10.1089/acm.2007.0788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Armbruster SD, Song J, Gatus L, Lu KH, & Basen-Engquist KM (2018). Endometrial cancer survivors’ sleep patterns before and after a physical activity intervention: A retrospective cohort analysis. Gynecological Oncology, 149(1), 133–139. 10.1016/j.ygyno.2018.01.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Park J, Wehrlen L, Mitchell SA, Yang L, & Bevans MF (2019). Fatigue predicts impaired social adjustment in survivors of allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT). Supportive Care in Cancer, 27(4), 1355–1363. 10.1007/s00520-018-4411-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Zhou ES, Clark K, Recklitis CJ, Obenchain R, & Loscalzo M (2018). Sleepless from the get go: Sleep problems prior to initiating cancer treatment. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 25(5), 502–516. 10.1007/s12529-018-9715-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Bellizzi KM, Aziz NM, Rowland JH, Weaver K, Arora NK, Hamilton AS, et al. (2012). Double jeopardy? Age, race, and HRQOL in older adults with cancer. Journal of Cancer Epidemiology. 10.1155/2012/478642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Blinder V, Patil S, Eberle C, Griggs J, & Maly RC (2013). Early predictors of not returning to work in low-income breast cancer survivors: A 5-year longitudinal study. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment, 140(2), 407–416. 10.1007/s10549-013-2625-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Orom H, Biddle C, Underwood W 3rd, Homish GG, & Olsson C (2017). Racial/ethnic and socioeconomic disparities in prostate cancer survivors’ prostate-specific quality of life. Urology. 10.1016/j.urology.2017.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Lee E, Takita C, Wright JL, Reis IM, Zhao W, Nelson OL, et al. (2016). Characterization of risk factors for adjuvant radiotherapy-associated pain in a tri-racial/ethnic breast cancer population. Pain, 157(5), 1122–1131. 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Krok-Schoen JL, Fernandez K, Unzeitig GW, Rubio G, Paskett ED, Post DM, et al. (2019). Hispanic breast cancer patients’ symptom experience and patient-physician communication during chemotherapy. Supportive Care in Cancer, 27(2), 697–704. 10.1007/s00520-018-4375-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Meneses K, Gisiger-Camata S, Benz R, Raju D, Bail JR, Benitez TJ, et al. (2018). Telehealth intervention for Latina breast cancer survivors: A pilot. Womens Health (London), 14, 1745506518778721. 10.1177/1745506518778721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Segrin C, Badger TA, Sikorskii A, Pasvogel A, Weihs K, Lopez AM, et al. (2019). Longitudinal dyadic interdependence in psychological distress among Latinas with breast cancer and their caregivers. Supportive Care in Cancer. 10.1007/s00520-019-05121-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Sleight AG, Lyons KD, Vigen C, Macdonald H, & Clark F (2019). The association of health-related quality of life with unmet supportive care needs and sociodemographic factors in low-income Latina breast cancer survivors: A single-Centre pilot study. Disability and Rehabilitation, 41(26), 3151–3156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Owens B, Jackson M, & Berndt A (2009). Complementary therapy used by Hispanic women during treatment for breast cancer. Journal of Holistic Nursing., 27(3), 167–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Black DS, Cole SW, Christodoulou G, & Figueiredo JC (2018). Genomic mechanisms of fatigue in survivors of colorectal cancer. Cancer, 124(12), 2637–2644. 10.1002/cncr.31356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Sanchez-Birkhead AC, Carbajal-Salisbury S, Larreta JA, Lovlien L, Hendricks H, Dingley C, et al. (2017). A community-based approach to assessing the physical, emotional, and health status of hispanic breast cancer survivors. Hispanic Health Care International, 15(4), 166–172. 10.1177/1540415317738016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Brisbois MD (2014). An interpretive description of chemotherapy-induced premature menopause among Latinas with breast cancer. Oncology Nursing Forum, 41(5), E282–E289. 10.1188/14.onf.e282-e289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Ashing-Giwa KT (2008). Enhancing physical well-being and overall quality of life among underserved Latina-American cervical cancer survivors: Feasibility study. Journal of Cancer Survivorship, 2(3), 215–223. 10.1007/s11764-008-0061-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Ashing-Giwa KT, & Lim JW (2010). Exploring the association between functional strain and emotional well-being among a population-based sample of breast cancer survivors. Psychooncology, 19(2), 150–159. 10.1002/pon.1517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Dyer KE (2015). “Surviving is not the same as living”: Cancer and Sobrevivencia in Puerto Rico. Social Science and Medicine, 132, 20–29. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.02.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Ashing-Giwa KT, Padilla G, Tejero J, Kraemer J, Wright K, Coscarelli A, et al. (2004). Understanding the breast cancer experience of women: A qualitative study of African American, Asian American. Latina and Caucasian cancer survivors. Psychooncology., 13(6), 408–428. 10.1002/pon.750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Castillo A, Mendiola J, & Tiemensma J (2019). Emotions and coping strategies during breast cancer in Latina women: A focus group study. Hispanic Health Care International, 17(3), 96–102. 10.1177/1540415319837680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Casillas J, Kahn KL, Doose M, Landier W, Bhatia S, Hernandez J, et al. (2010). Transitioning childhood cancer survivors to adult-centered healthcare: Insights from parents, adolescent, and young adult survivors. Psychooncology, 19(9), 982–990. 10.1002/pon.1650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Crookes DM, Shelton RC, Tehranifar P, Aycinena C, Gaffney AO, Koch P, et al. (2016). Social networks and social support for healthy eating among Latina breast cancer survivors: Implications for social and behavioral interventions. Journal of Cancer Survivorship, 10(2), 291–301. 10.1007/s11764-015-0475-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Galvan N, Buki LP, & Garces DM (2009). Suddenly, a carriage appears: Social support needs of Latina breast cancer survivors. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology, 27(3), 361–382. 10.1080/07347330902979283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Kent EE, Alfano CM, Smith AW, Bernstein L, McTiernan A, Baumgartner KB, et al. (2013). The roles of support seeking and race/ethnicity in posttraumatic growth among breast cancer survivors. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology, 31(4), 393–412. 10.1080/07347332.2013.798759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Napoles AM, Ortiz C, Santoyo-Olsson J, Stewart AL, Lee HE, Duron Y, et al. (2017). Post-treatment survivorship care needs of Spanish-speaking Latinas with breast cancer. Journal of Community Support and Oncology, 15(1), 20–27. 10.12788/jcso.0325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Patel SK, Lo TT, Dennis JM, & Bhatia S (2013). Neurocognitive and behavioral outcomes in Latino childhood cancer survivors. Pediatric Blood & Cancer, 60(10), 1696–1702. 10.1002/pbc.24608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Sammarco A, & Konecny LM (2010). Quality of life, social support, and uncertainty among Latina and Caucasian breast cancer survivors: A comparative study. Oncology Nursing Forum, 37(1), 93–99. 10.1188/10.onf.93-99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Smith AB, & Bashore L (2006). The effect of clinic-based health promotion education on perceived health status and health promotion behaviors of adolescent and young adult cancer survivors. Journal of Pediatric Oncology Nursing, 23(6), 326–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Lockhart JS, Oberleitner MG, & Nolfi DA (2018). The Hispanic/Latino immigrant cancer survivor experience in the United States: A scoping review. Annual Review of Nursing Research, 37(1), 119–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Moreno PI, Ramirez AG, San Miguel-Majors SL, Castillo L, Fox RS, Gallion KJ, et al. (2019). Unmet supportive care needs in Hispanic/Latino cancer survivors: Prevalence and associations with patient-provider communication, satisfaction with cancer care, and symptom burden. Supportive Care in Cancer, 27(4), 1383–1394. 10.1007/s00520-018-4426-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Moreno PI, Ramirez AG, San Miguel-Majors SL, Fox RS, Castillo L, Gallion KJ, et al. (2018). Satisfaction with cancer care, self-efficacy, and health-related quality of life in Latino cancer survivors. Cancer, 124(8), 1770–1779. 10.1002/cncr.31263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Ochoa CY, Haardorfer R, Escoffery C, Stein K, & Alcaraz KI (2018). Examining the role of social support and spirituality on the general health perceptions of Hispanic cancer survivors. Psychooncology, 27(9), 2189–2197. 10.1002/pon.4795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Segrin C, Badger TA, & Sikorskii A (2019). A dyadic analysis of loneliness and health-related quality of life in Latinas with breast cancer and their informal caregivers. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology, 37(2), 213–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Sleight AG, Lyons KD, Vigen C, Macdonald H, & Clark F (2018). Supportive care priorities of low-income Latina breast cancer survivors. Supportive Care in Cancer, 26(11), 3851–3859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Blinder V, Eberle C, Patil S, Gany FM, & Bradley CJ (2017). Women with breast cancer who work for accommodating employers more likely to retain jobs after treatment. Health Affairs (Millwood), 36(2), 274–281. 10.1377/hlthaff.2016.1196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Blinder VS, Patil S, Thind A, Diamant A, Hudis CA, Basch E, et al. (2012). Return to work in low-income Latina and non-Latina white breast cancer survivors: A 3-year longitudinal study. Cancer, 118(6), 1664–1674. 10.1002/cncr.26478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Burg MA, Adorno G, Lopez ED, Loerzel V, Stein K, Wallace C, et al. (2015). Current unmet needs of cancer survivors: Analysis of open-ended responses to the American Cancer Society Study of Cancer Survivors II. Cancer, 121(4), 623–630. 10.1002/cncr.28951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Jagsi R, Pottow JA, Griffith KA, Bradley C, Hamilton AS, Graff J, et al. (2014). Long-term financial burden of breast cancer: Experiences of a diverse cohort of survivors identified through population-based registries. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 32(12), 1269–1276. 10.1200/jco.2013.53.0956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Mujahid MS, Janz NK, Hawley ST, Griggs JJ, Hamilton AS, Graff J, et al. (2011). Racial/ethnic differences in job loss for women with breast cancer. Journal of Cancer Survivorship, 5(1), 102–111. 10.1007/s11764-010-0152-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Mujahid MS, Janz NK, Hawley ST, Griggs JJ, Hamilton AS, & Katz SJ (2010). The impact of sociodemographic, treatment, and work support on missed work after breast cancer diagnosis. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment, 119(1), 213–220. 10.1007/s10549-009-0389-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]