ABSTRACT

Social media (SoMe) are platforms that enable users to create and share content, or participate in social networking. Medical education is rapidly moving into a post-COVID world, with the use of SoMe becoming ever more prominent. We explore the risks and benefits of using this technology to assist learning and examine these in light of relevant educational theory.

Benefits include accessibility to experts, opportunities for mentorship, access to support networks, resource sharing and global participation. Following the ‘Black Lives Matter’ movement, SoMe has provided the impetus to adapt medical curricula to address health inequities in minority ethnic individuals.

Key criticisms focus on superficial learning, psychological safety, correctly identifying level of expertise, professionalism and ownership protections for content creators. Users have limited ways to manage risk.

The medical education community must adapt and rapidly critique SoMe innovations so that they can be better developed and learned from, all the while remaining vigilant.

KEYWORDS: medical education, social media, Twitter, technology enhanced learning, Facebook

Introduction

Social media (SoMe) are platforms that enable users to create and share content or participate in social networking. The key difference between SoMe and other websites is the multi-directional flow of information.

Medical education (MedEd) is moving into a post-COVID world with SoMe becoming ever more prominent. Educators and learners alike are utilising SoMe for far more than information gathering; focus has turned to the delivery of education itself. The ‘social’ is just as important as the ‘media’. As investigations into this phenomenon develop, educational theories are being adapted to fit the digital age. Previous iterations applicable to face-to-face teaching may not sufficiently explain the success or shortcomings of digital education methods. Further, the educational community's understanding and trust of this complex social phenomenon has been called into question. While numerous studies have attempted to extol the virtues of SoMe as applied to undergraduate MedEd, here we apply a critical lens, highlighting the risks associated with SoMe learning and examining relevant educational theory in the context of 2020 SoMe.

Overview of education theories

The grounding for the use of SoMe in MedEd revolves around the theories of connectivism and communities of practice, while its effectiveness can be evaluated by cognitive learning frameworks such as Bloom's taxonomy.

Connectivism

Connectivism is an eminent learning theory for the digital age. It postulates that learning occurs through the formation of networks, largely facilitated by technology.1 Learners are given the tools and educators merely facilitate the process.2 In the context of SoMe, this translates to online interactions. A high number of connections should, in theory, increase the opportunity for knowledge transfer and resource sharing. These networks may also expose learners to diverse perspectives, encouraging them to develop critical thinking skills and examine their own knowledge. Practically, this results in the formation of learning communities (cluster networks of individuals at all levels) with similar motives and interests.

Communities of practice

Communities of practice describe individuals with a common domain of interest collaborating and sharing ideas to learn or complete a task.2 Socially sanctioned responsibility encourages learners to play a central role in the community. This contrasts with settings where knowledge sharing may be unidirectional, from the educator to the learner. Lave and Wegner use the apprenticeship of tailors, where much of the learning occurs ‘on the job’ without formal didactic teaching, as an example of such communities.3 This is analogous to medical students learning on hospital ward placements, where the emphasis is on developing practical skills in situ.

Bloom's taxonomy of cognitive domains

Bloom's taxonomy is a hierarchical framework that examines the cognitive aspects of learning, such as how learners process received information and relate it to what is already known. The framework portrays effective learning as engaging the following processes with increasing order of complexity (remembering, understanding, applying, analysing, evaluating and creating) and provides a structure against which educational interventions can be evaluated.4

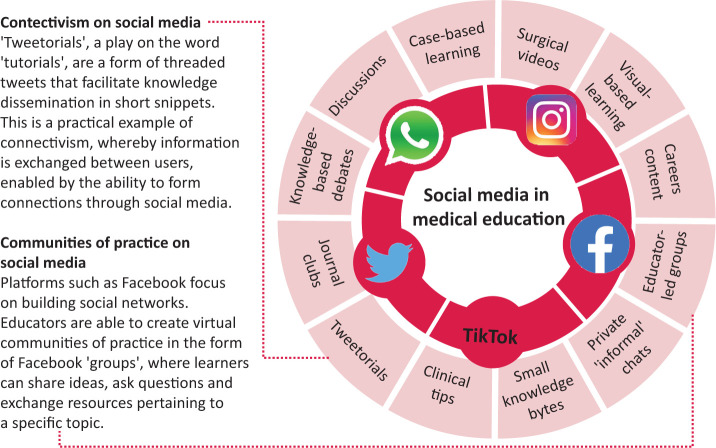

Within the context of SoMe, there are numerous applications of these learning theories. Different SoMe platforms can be used to support and deliver MedEd, and describes how the theories of communities of practice and connectivism apply (Fig 1).

Fig 1.

Applications of social media platforms in medical education. The inner ring displays the logos of five social media platforms: (clockwise from top right) Instagram, Facebook, TikTok, Twitter and Whatsapp. The outer ring provides examples of how these platforms may be used to serve medical education. Each example is located near its most relevant platform, however, there is significant overlap between them.

Benefits of social media

There are several advantages of using SoMe for MedEd. Platforms like Twitter work particularly well for delivering journal clubs and Tweetorials because they permit live global participation. Additionally, SoMe offers a degree of informality that facilitates accessibility to experts, regardless of seniority or status; not always the case in the hierarchies of a hospital-based workforce.

Similarly, SoMe can provide a wealth of opportunities for individuals early in their careers to seek out mentors with particular expertise. Drawing on communities of practice, SoMe can integrate students and trainees into the centre of the learning sphere, laying the foundations for collaboration with seniors. Indeed, this very article is the product of such collaboration; no authors have met in person and all communications were initiated on Twitter. Further examples include the use of the hashtags #ILookLikeASurgeon and #WomeninMedicine, which have enabled female doctors across the world to form both professional and social relationships. In turn, this has set the stage for the next generation of female clinicians to connect with role models who may have been otherwise unreachable. These connections can then act as a catalyst for successfully navigating the often male-dominated upper echelons of both medicine and academia.5

Case study 1: The hidden curriculum

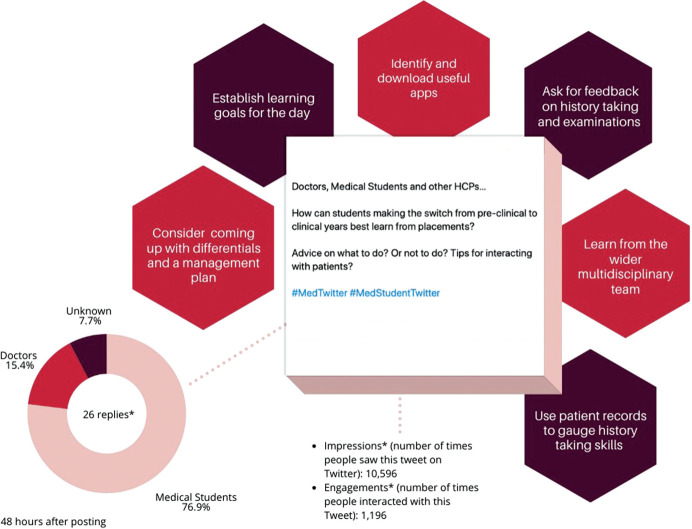

The hidden curriculum can be defined as those cultural aspects learnt about beyond the confines of a formal curriculum. One example is the Facebook group ‘Tea & Empathy’, which facilitates the discussion of concerns and struggles relating to work and enables members to seek the advice of others on how to navigate them. On Twitter, hashtags such as #HiddenCurriculum, #MedTwitter and #MedStudentTwitter are useful in signposting individuals to discussions around a variety of related topics. Some examples include optimising sleep patterns for night shifts, maintaining a work–life balance, advice regarding revision and interviews and how to make the most out of clinical placements (Fig 2). In contrast to learning solely from the experiences of people within the immediate geographical vicinity (ie at one's medical school), SoMe is an effective means of learning from and comparing the experiences of individuals outwith usual boundaries.

Fig 2.

An example of the hidden curriculum being discussed on Twitter in response to the tweet: ‘Doctors, Medical Students and other HCPs... How can students making the switch from pre-clinical to clinical years best learn from placements? Advice on what to do? Or not to do? Tips for interacting with patients? #MedTwitter #MedStudentTwitter. The text surrounding the tweet summarises some of the key recommendations suggested in the replies to this tweet. 48 hours after posting, 26 replies were received. The percentage breakdown of replier occupation is shown by the pie chart. This was determined by information supplied in the user's Twitter biography, if not stated, then user occupation was labelled as ‘unknown’.

In light of recent activities with numerous Black Lives Matter protests worldwide, there has been an increasing awareness of the disparate outcomes in healthcare for individuals from minority ethnic backgrounds. A movement to ‘decolonise’ the medical curriculum is beginning to progress, as a community we are now confronting how race has impacted many of our current medical practices. While there have been a host of historical efforts to tackle such inequalities, the uptake of such initiatives has not been as widespread or fast-moving as recent cultural shifts. SoMe has proven a useful and impactful way to disseminate important information among students and doctors alike. Initiatives, such as working documents with useful resources and reading lists, have been shared via Facebook and Twitter by medical students. This is a good example of SoMe encouraging learners to be active participants in their education. Students have also been able to share examples of initiatives they have undertaken within their own individual institutions with healthcare professionals of varying levels. Such actions are linked to the learning theory of connectivism where knowledge is shared across all levels.

Case study 2: Decolonising medicine

Students at the University of Liverpool conducted a review of their University's curriculum to construct a report, Are we doing our BAME patients a disservice in care due to a lack of diversity in the current medical curriculum?, which highlighted areas that could be improved as well as providing actionable suggestions for improvement.6

The Decolonising the Medical Curriculum Reading List is an example of a working document created by the collaboration of students on SoMe. It offers advice on how to navigate the topic and makes recommendations of a range of articles and books relating to historical awareness, epistemic bias and developing an understanding of the intersectional determinants of health.7

Social media also has utility for widening participation (WP). WP activities aim to increase the proportion of students entering medical school from under-represented groups. While formal WP initiatives do exist in the UK, SoMe permits social accessibility to those in medicine, for example, by enabling prospective students to connect with current medical students and ask for application advice.

Despite these benefits, a light should be shone onto the ‘dark side’ of the medium.

Criticisms of social media

One criticism levelled towards SoMe in MedEd is the superficial nature of the learning it facilitates. A large proportion of education provision on SoMe involves the consumption of medical information, for example ‘Tweetorials’ or the ‘live-tweeting’ of meetings, whereby learners are merely exposed to factual statements. Bloom's taxonomy suggests effective learning should involve all six of its domains (remembering, understanding, applying, analysing, evaluating and creating), however, the aforementioned examples only engage remembering and understanding.4 As a result, the effectiveness of such learning may be limited.

Even in the most casual of learning contexts, users are faced with the task of judging the accuracy of information they encounter. While SoMe may be beneficial in providing content, users risk learning inaccurate information. The limited ability to regulate the credentials of ‘the educator’ adds to this. In response to the spread of misinformation concerning the COVID-19 pandemic on its platform, Twitter accelerated its verification process to endorse the credibility of ‘expert’ accounts by adding a blue tick next to their names. However, verified status is not exclusive to health experts; these accounts are no less capable of spreading misinformation. If they do, this information may be held to higher esteem than that of non-verified accounts. This argument extends to those in authority, including world-leaders.

We suggest the need to evaluate ‘social capital’ in the development of virtual communities of practice. Social capital is a construct that considers the collective value of one's social networks (for example, interpersonal relationships, achievements, perceived reputation and access to resources).8 In the context of SoMe, the number of subscribers or followers one has may directly influence social capital. Emphasis on superficial metrics may foster an environment where certain concepts gain traction due to the fact that there is a large following, as opposed to educational merit. This risks creating a barrier of entry to those with less social capital wanting to contribute to educational content.

SoMe can also present a hostile environment for educators who are afforded little protection over their content. Intellectual property infringement is a growing problem, and most platforms' terms of service require users to grant permission to use, modify, distribute and copy their material.9 Additionally, the rise and fall of different platforms can lead to learning trends dying off quickly, when they do, creators risk losing the work they created.

Professionalism concerns may hinder the uptake of SoMe for MedEd. A now-retracted study investigating unprofessional SoMe content among vascular surgeons was itself subject to criticism on SoMe for its definition of unprofessional behaviour.10 Photographs depicting surgeons holding alcohol, wearing inappropriate attire (the example given: bikinis) and posting comments on controversial social topics were labelled as potentially unprofessional. Many healthcare professionals took to SoMe to highlight the subjective nature of the definition and its implicit biases, starting the #MedBikini trend. This backlash against somewhat archaic concepts of professionalism demonstrates that SoMe professionalism is becoming increasingly nuanced. Greater focus is needed on specific risks to users (such as cyberbullying and trolls), which may make SoMe a toxic educational environment. Conversely, the response to the article is an example of rapid calls for social change brought to light by SoMe.

SoMe is transforming the way MedEd is delivered, but this comes with a dark side. Key concerns include psychological safety, correctly identifying level of expertise, professionalism and ownership protections, many of which apply to the general use of SoMe. Users have limited ways to manage risk: reporting cyberbullies, opting to ‘private’ modes if concerned about who can view their profiles, creating private educational groups and including an ownership statement when posting content.9 While evaluating these methods is beyond the scope of this piece, we recognise that many of these strategies are insufficient and not always available.

Conclusion

SoMe in MedEd, though a double-edged sword, is here to stay. It presents numerous benefits, for example, connecting learners across the continents and hierarchies and providing the impetus to adapt medical curricula in addressing health inequities. Issues regarding professionalism, though heavily investigated, are becoming progressively nuanced, while the rise of online bullying, trolls and fake news are of increasing concern. Moreover, it could be argued that SoMe promotes the consumption of enjoyable, convenient, yet ultimately less useful information. The MedEd community must take a critical approach to SoMe innovations and their integration with other education structures. Only then can we optimise and utilise learning from SoMe alongside recognising and managing the potential risks.

Conflicts of interest

Dr Jonathan Guckian is a director of communications and social media for the Association for the Study of Medical Education (ASME), founder of Medisense Medical Education and junior editorial trainee at the British Journal of Dermatology.

References

- 1.Goldie J. Connectivism: A knowledge learning theory for the digital age? Med Teach 2016;38:1064–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Flynn L, Jalali A, Moreau K. Learning theory and its application to the use of social media in medical education. Postgrad Med J 2015;91:556–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fuller A, Hodkinson H, Hodkinson P, Unwin L. Learning as peripheral participation in communities of practice: a reassessment of key concepts in workplace learning. British Educational Research Journal 2005;31:49–68. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Currie G, Woznitza N, Bolderston A, Prospero L, Nightingale J. Twitter journal club in medical radiation science. J Med Imaging Radiat Sci 2017;48:83–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lewis J, Fane K, Ingraham A, et al. Expanding opportunities for professional development: utilization of Twitter by early career women in academic medicine and science. JMIR Medical Education 2018;4:e11140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gittens J, Clynch A, Amoako-Tawiah P, et al. Are we doing our BAME patients a disservice in care due to a lack of diversity in the current medical curriculum? An open letter. 2020. https://docs.google.com/document/d/14U4lbXoWuk3fxmS8aaBic0mU3a3FpAD0gITN2weEQg4/mobilebasic [Accessed 11 August 2020].

- 7.Wong S, Plowman T, Nwibe I, Chow H, Puri D. Decolonising the medical curriculum reading list 2020. 2020. https://docs.google.com/document/d/1_H8mm4-CRP0yzt0ms_c2lfWV1zO5A4tQJSiTg9rw_ZI/edit [Accessed 11 August 2020].

- 8.Williams J. The use of online social networking sites to nurture and cultivate bonding social capital: A systematic review of the literature from 1997 to 2018. New Media & Society 2019;21:2710–29. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nowak L. Intellectual property and social media. European IP Helpdesk Internet, 2020. www.iprhelpdesk.eu/blog/intellectual-property-and-social-media [Accessed 27 December 2020].

- 10.Hardouin S, Cheng T, Mitchell E, et al. Prevalence of unprofessional social media content among young vascular surgeons. Journal of Vascular Surgery 2019;69:e31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]