ABSTRACT

Never before in history have we had the data to track such a rapid increase in inequalities. With changes imminent in healthcare and public health organisational landscape in England and health inequalities high on the policy agenda, we have an opportunity to redouble efforts to reduce inequalities.

In this article, we argue that health inequalities need re-framing to encompass the breadth of disadvantage and difference between healthcare and health outcome inequalities. Second, there needs to be a focus on long-term organisational change to ensure equity is considered in all decisions. Third, actions need to prioritise the fundamental redistribution of resources, funding, workforce, services and power.

Reducing inequalities can involve unpopular and difficult decisions. Physicians have a particular role in society and can support evidenced-based change across practice and the system at large. If we do not act now, then when?

KEYWORDS: health inequalities, equity, health systems, healthcare organisations

Introduction

For the first time in history we have the empirical data to witness a rapid compounding of existing inequalities due to the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly for lower socio-economic and minority ethnic groups.1,2 In the UK, deaths in the most deprived areas are double those in the least deprived (age–sex standardised rate in the least deprived areas are 350 deaths per 100,000 compared with 669 in the most).3 In the USA and UK, deaths are up to three times higher in minority ethnic groups.4 The current crisis represents a syndemic pandemic; the intertwined, interactive and cumulative effects on health and wellbeing of the COVID-19 pandemic combined with substantial existing socio-economic inequalities across life courses and in communities.2

Despite the policy prominence and various frameworks focusing on health inequalities, healthcare leaders still do not feel they have the skills and knowledge to reduce health inequalities.5–9 The underlying reasons for this may include a failure of researchers to provide accessible evidence on how to translate evidence into practice as well as a lack of a systematic and logical approach to inequalities for healthcare systems.10–12 Physicians have a particular role in society and can support evidence-based change across practice and the system at large. Here, we first discuss the current policy and research context, then argue it is time for a re-framing of inequalities within healthcare systems, with a concerted effort to build a long-term organisational change to tackle inequalities head on, along with a wider redistribution of resources, funding, workforce, services and power across healthcare and wider society.

Policy, research and legislative context of health systems in the UK

In England, for the first time, key national and local NHS decision-making bodies were required by law to address inequalities in access and outcomes under the Health and Social Care Act 2012.13 This was the result of a growing body of literature showing sustained stark health outcome inequalities, dating back to the Black report, with inequalities in waiting times, patient experience and hospital admissions.14–17 The Health and Social Care Act also shifted power from ministerial departments to NHS England with a decentralisation of decision making to local health systems. Despite the statutory responsibility, the years after the enactment of the Health and Social Care Act were dominated by reorganisation with considerable fragmentation of previously aligned services. Reforms were undertaken in the name of efficiency with poor evidence of their impact, rising costs to the health system and little progress on health inequalities, despite the clear negative health and wellbeing impacts of austerity and welfare reform.18,19 Public health professionals classified the risk of this reorganisation to widen health inequalities as ‘extreme’.20

In 2019, the NHS in England was asked to develop its own plans for a £20 billion funding injection. High-level policy objectives and initiatives were outlined in The NHS Long Term Plan and, in turn, local healthcare systems were asked to develop their own local response plans.21 Health inequalities were a prominent feature of the national The NHS Long Term Plan among other priorities, such as primary care workforce, integration, prevention, cardiovascular disease and cancer. The plan set out to establish a ‘more concerted and systematic approach to reducing health inequalities’ alongside a number of specific inequalities initiatives such as supporting minority ethnic groups. However, the plan and its subsequent supporting documents failed to outline how local and national systems could systematically approach health inequalities with an expectation that local healthcare systems would each develop their own approaches. Our own previous research has highlighted that this is challenging for local systems, resulting in local plans being vague and lacking a systematic or joined-up approach.12 Furthermore, the lack of a national health inequalities strategy (like that successfully pursued between 2000 and 2010) makes it harder to effect change across local health systems.22,23

In response to COVID-19 inequalities data, NHS England and NHS Improvement (NHSE/I) published eight urgent actions to address health inequalities, including directives protecting the most vulnerable, improving recording, strengthening leadership and increasing preventative measures.24

The structure of the NHS has moved substantially from its inception, through many re-disorganisations and, lately, the statutory bodies established under the Health and Social Care Act 2012. More recently, integrated care systems have been established, which are likely to merge with clinical commissioning groups.25 It is likely that further health and social care legislation, under the advice of NHSE/I, will be passed in the near future to catch up with the organisational evolution.26

Only 7 years after its formation, Public Health England (PHE) is already being disestablished. PHE was set up to protect and improve the nation's health and reduce health inequalities.27 One action of the Health and Social Care Act was the extraction of public health skills from leadership roles within the NHS, something that was an obvious gap immediately after revealing a lack of understanding of the key role of public health leadership and skills in health and social care systems. This has become critical during the COVID-19 pandemic, as more public health leadership in the health and social care system may have improved the response.

Health inequalities have been a common thread across PHE activities. While trying work across organisational boundaries, these have included the provision of data on health inequalities, guidance, evidence-based tools for local health systems, advice to national government and focused action on inequalities in screening and immunisations.5,28–31 PHE have particularly promoted a place-based approach to inequalities.5 Under current plans PHE's health protection functions will be taken over by the National Institute for Health Protection, but the future location of the other PHE functions is still under discussion.

The research community has been driving forward the inequalities' agenda. The Academy of Medical Sciences published their report Improving the health of the public by 2040 promoting a health of the public research approach with a strong emphasis on health equity.32 In response to this, the Strategic Coordination of the Health of the Public Research committee (SCHOPR) was established and has set out its guiding principles on population research, including a priority of focused investigation into how interdisciplinary research can reduce inequalities.33 Furthermore, the Academy of Medical Sciences has recently written to the secretary of state outlining the need to prioritise prevention and improvement to reduce inequalities.34

More recently, the Royal College of Physicians have convened a coalition of over 140 organisations to campaign for a cross-government strategy to reduce inequalities, the commencement of the socio-economic duty in the Equality Act and prioritising child health in public policy.35

With the healthcare and public health reform afoot, inequalities highlighted due to the pandemic are thus high on the policy agenda, and a mobilised research community, it is time to rethink our approach to inequalities within and beyond the healthcare system. Without clarity, sufficient prioritisation and leadership any actions are at risk of only ever having a marginal impact.

Framing inequalities to ensure a systematic and logical approach in health systems

Framing is a way of structuring or presenting a problem and can be helpful, potentially vitally so, to ensuring action.36 How we discuss and present inequalities must be developed with and for any audience it is hoped might contribute to effective changes; for example, NHS staff are more likely to engage if inequalities are framed around healthcare and the specific services for which they are responsible, such as inequalities in chronic disease management or non-elective admissions alongside concrete actions, rather than high-level more abstract health outcome inequalities, such as differences in life expectancy.37 A lack of adequate framing brings risks. Focusing only on high level inequalities with healthcare staff, such as life expectancy, may lead to a sense of fatalism because these inequalities are primarily driven by geo-political factors outwith the influence of local health systems and their leaders; or a belief that downstream individual actions targeted at the social determinants of health will reduce inequalities.38–40 In turn, these may lead to a health inequalities fatigue where motivation for action on inequalities wains due to short-termism and a perceived lack of progress.

A broad framing of inequalities highlighting how multiple different aspects of disadvantage lead to substantial differences in healthcare and health outcomes is needed to allow decision-makers to develop their own systematic and logical approach to doing what is within their power and advocacy to reduce inequalities. Without this systematic approach, there is a risk of an unequal focus on certain groups at the expense of others, such as focusing on the so-called ‘deserving poor’ at the expense of the ‘undeserving poor’.41 Our review of local NHS plans revealed that systems focused more on people with learning difficulties and autism, but less so on undocumented migrants, people who are transgender or those with justice service involvement.12 This creates inequalities within inequalities.

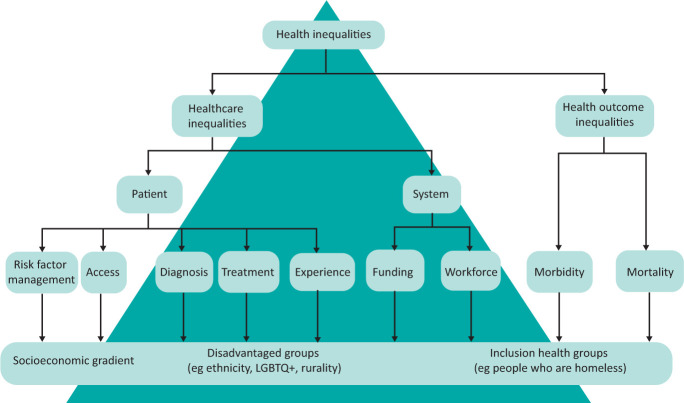

Inequalities must be framed and measured to include both healthcare (eg risk factor management, access, diagnosis, treatment and experience) and health outcome (eg morbidity and mortality) inequalities (Fig 1). Key components across the spectrum of health and care include the distribution of health system resources (namely funding, workforce and research distribution, and training), access to and quality of healthcare, major drivers of mortality and morbidity (eg cardiovascular disease, respiratory disease, cancer, mental health and musculoskeletal conditions) and conditions which are intrinsically associated with inequalities (such as drug and alcohol abuse).

Fig 1.

Unpacking health inequalities.

Framing should avoid language which is stigmatising or shaming. Smith and colleagues describe a paradox where people recognise that health is determined by social factors and acknowledged socio-economic inequalities in society, but are reluctant to acknowledge the resulting health inequalities.42 The authors suggest this paradox arises because individuals do not want the place in which they live to be stigmatised, shamed, or have negative or derogatory connotations, which may have negative impacts on their employment opportunities or family.43 Other studies have found that the idea of socio-economic health inequalities can be a source of stress for residents.44,45

Building the long-term organisational change

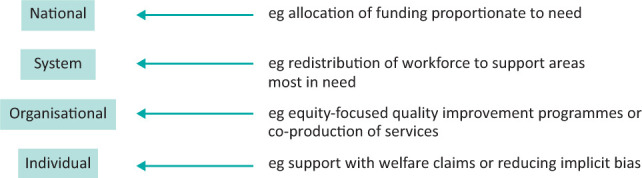

Many health inequalities have arisen over decades and even centuries, operating across generations and communities, due to long-standing imbalances in the social determinants of health. It is noteworthy that the north-south pattern of deaths from the Spanish flu pandemic of 1918, almost exactly mirrors the distributions of COVID-19 deaths over a century later.46 New manifestations of inequalities emerge over time, often with the promise of solutions and enthusiasms from new technologies. Previously this was the offer of screening, known to be taken up preferentially by more advantaged in society, and more recently in access to digital healthcare services with clear differential access.47 In light of the plethora of existing and emerging inequalities, many feel a moral duty to ‘do something’, including investments in actions that lack a strong evidence base or sustainability (such as social prescribing or hospitals acting as anchor institutions).48 It is important, therefore, for the NHS to resist the temptation to reach for such short-term actions at the expense of focusing on the long-term organisational change required for sustained and evidenced-based action. With the formation of integrated care systems in the NHS in England we have the opportunity to ensure an equity perspective is adopted from the start, maximising the opportunities of integrated working across health and social care. However, we need inequalities actions at all levels of healthcare, including national, system, organisational and individual (Fig 2).

Fig 2.

Levels of health inequalities actions.

Much health data, particularly within hospitals, is not presented by socio-economic group, geographical disadvantage or ethnicity. The NHS eight urgent actions to address inequalities aims to improve ethnicity recording.24 More upskilling is needed to help healthcare analysts undertake equity analyses to explore the difference between groups, adjusting for age and gender where appropriate. Equity perspectives are still rarely considered in healthcare quality improvement programmes, clinical audits, service evaluation or adverse events investigation; for example, hospital-based quality improvement programmes should consider if the services changes improve quality of care across socio-economic groups and ethnicity equally. Adverse event investigations should include an exploration how healthcare supported (or not) patients who are disadvantaged, for example due to poor health literacy or social support, interacted with services.

Previous research suggests that equity-focused processes can support healthcare organisations, their teams and individuals within these to address inequalities.49 Health inequalities impact assessment is a process of exploring and mitigating the impacts of decisions on inequalities during decision making. Sadare and colleagues found that health inequalities impact assessment, if undertaken a meaningful way, can be a catalyst for equity-focused organisational change.49 These could be used by clinical directors and hospital leaders to ensure that secondary care services do not increase inequalities.

Applied research has an vital role to play in exploring the distributional effects of interventions across disadvantaged groups and generating evidence of what works to reduce inequalities.50,51 The evidence produced by current research poorly represents those who are most disadvantaged. The SCHOPR principles call for co-produced, transdisciplinary research to create and deliver targeted national and local solutions to reduce inequalities.33 More research is needed to develop and understand the implementation of evidence-based solutions drawing upon disciplines such as geography, anthropology, sociology, economics and history. Research capacity and skills must be embedded in the organisations which emerge from the latest restructure to help them become learning systems.

Redistributing resources and power to prevent illness and promote health

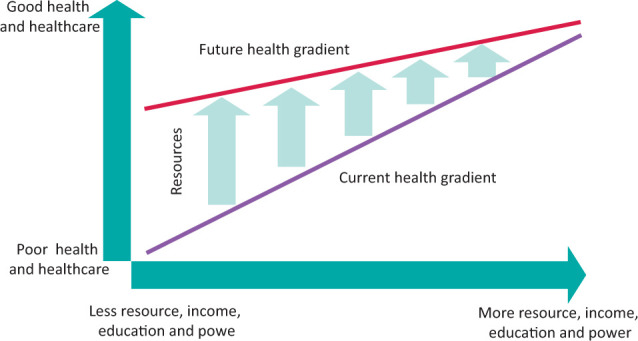

Inequalities are caused by the unequal distribution of social determinants of health, public and private investment, public sector workforce, services and power (the ability of one section of society to control another).52 Without a fundamental change to how society can organise itself to address these, inequalities in health outcomes will persist. However, even within the way we organise ourselves currently and contrary to the sense that nothing can be done, there is evidence that the NHS can reduce inequalities. One example is an analysis of the increase of NHS resources to more deprived areas between 2001 and 2011, revealing a reduction in inequalities from causes amenable to healthcare.53 This complements the principle of proportionate universalism, which states services should be accessible to all, but the intensity of the service should be proportionate to need with the most disadvantaged receiving more resources (Fig 3).14 While existing national NHS allocation formulae are weighted for deprivation, evidence suggests they do not go far enough; and, in England, the weighting was reduced after the 2011 Act.54

Fig 3.

Distributing resources proportionate to need.

Beyond specific healthcare system evidence, there is also good evidence that cross government action can reduce inequalities.22,23 Over the last couple of decades, there has been a natural experiment at a national scale. The UK government implemented a cross-government health inequalities programme and strategy from 2000 to 2010. Prior to the start of the programme, the difference in life expectancy between the most deprived areas and the rest of England was increasing by 0.57 months per year for males and 0.30 months per year for females.22 The strategy reversed these trends with the gap in life expectancy reducing by 0.91 months per year for men and 0.50 months per year for women. Inequalities in the infant mortality rate (IMR) also decreased.23 However, since the end of the strategy and the implementation of austerity, the inequality gap widened again by a similar amount as before and there is now evidence of increasing inequalities in IMR associated with rising rates of child poverty.23 Key to the programme was a redistribution of funding, services and power to poorer areas, with regeneration initiatives, Sure Start centres to support early years childcare, increased NHS funding allocations, introduction of national minimum wage, more generous tax and benefit changes targeted at child poverty and targeted services in the most deprived local authorities. Unfortunately, detailed independent evaluation was not embedded or undertaken, and therefore the specific factors, either individually or collectively, which contributed to the observed narrowing inequalities gap remain unknown.

The importance of prevention and health promotion has been highlighted in several key documents.24,34 The irony is that the under the Health and Social Care Act, public health was taken out of the NHS, but the current The NHS Long Term Plan prioritises prevention. Greater clarity is needed to ensure that the manner in which this emphasis is implemented does not unintentionally widen the gap.55,56 For example, those with the resources and capabilities to benefit from an untargeted physical activity campaign have been and already are the more affluent groups with financial resources, health literacy and employment flexibility. This is also replicated within our research programmes and recruitment, which in many clinical research spheres do not represent diverse and disadvantaged communities. Policy makers should avoid the temptation to think that unhealthy lifestyles in people living in poorer areas arise because of a lack of knowledge or motivation and that the solution is information campaigns.52,57 Decades of research reaching has demonstrated again and again that people, whether from poor or rich backgrounds, understand the determinants of health and have logical reasons for unhealthy choices.57 For example, Graham found that pregnant women on low incomes still found money to buy cigarettes because smoking was the one opportunity in the day to do something for themselves in the context of very challenging life circumstances.58 More recently, Thirlway found that smoking cessation was shaped by (lack of) social mobility.59 To prevent illness and promote health we must break down the power hierarchies which suggest that one part of society knows what is best for another and get alongside people to understand why they act the way they do, treating them as experts in their lived experience, co-designing solutions as equal partners and advocating for the wider societal changes needed to address the social and economic context of inequality.60

Conclusion

We all have an ethical and moral imperative to respond to the rapid proliferation of existing inequalities. Simultaneously, healthcare and public health organisations are being re-structured in England. We argue that the concept of health inequalities needs to be reframed to acknowledge the breadth of health and care inequalities with non-stigmatising language to ensure a systematic approach to the problem. A focus on building long-term equity-orientated organisational change in the NHS is urgently needed. At the core of any action should be the fundamental redistributions of resources, funding, workforce, services and power. If we do not act now in light of these stark inequalities, then when?

References

- 1.Public Health England . COVID-19: review of disparities in risks and outcomes. PHE, 2020. www.gov.uk/government/publications/covid-19-review-of-disparities-in-risks-and-outcomes [Accessed 09 June 2020]. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bambra C, Riordan R, Ford J, Matthews F. The COVID-19 pandemic and health inequalities. J Epidemiol Community Health 2020;74:964–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Office for National Statistics . Deaths involving COVID-19 by local area and socioeconomic deprivation. ONS, 2020. www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/deaths/bulletins/deathsinvolvingcovid19bylocalareasanddeprivation/deathsoccurringbetween1marchand17april [Accessed 03 May 2020]. [Google Scholar]

- 4.APM Research Lab . The color of coronavirus: COVID-19 deaths race and ethnicity in the US. APM Research Lab, 2020. www.apmresearchlab.org/covid/deaths-by-race [Accessed Dec 29, 2020]. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Public Health England . Place-based approaches for reducing health inequalities: foreword and executive summary. PHE, 2019. www.gov.uk/government/publications/health-inequalities-place-based-approaches-to-reduce-inequalities/place-based-approaches-for-reducing-health-inequalities-foreword-and-executive-summary [Accessed 05 September 2019]. [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization . A framework for measuring health inequality. WHO, 1996. www.who.int/healthinfo/paper05.pdf [Accessed 29 December 2020]. [Google Scholar]

- 7.NHS Health Scotland . Health inequalities action framework. NHS, 2013. www.healthscotland.scot/media/1223/health-inequalities-action-framework_june13_english.pdf [Accessed 29 December 2020]. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brooks D, Douglas M, Aggarwal N, et al. Developing a framework for integrating health equity into the learning health system. Learn Heal Syst 2017;1:e10029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.NHS Confederation . Public reassurance needed over slow road to recovery for the NHS. NHS, 2020. www.nhsconfed.org/news/2020/06/road-to-recovery [Accessed 08 October 2020]. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smith KE. Health inequalities in Scotland and England: the contrasting journeys of ideas from research into policy. Soc Sci Med 2007;64:1438–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith KE. The politics of ideas: The complex interplay of health inequalities research and policy. Sci Public Policy 2014;41:561–74. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Olivera J, Ford J, Sowden S, Bambra C. Conceptualisation of health inequalities by local health care systems: a document analysis. [Under peer review, 2021]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Health and Social Care Act 2012. www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2012/7/contents/enacted [Accessed 09 October 2019].

- 14.Marmot MG. Fair society, healthy lives: the Marmot review; strategic review of health inequalities in England post-2010. Marmot Review, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Acheson D. Independent inquiry into inequalities in health. Department of Health and Social Care, 1998. www.gov.uk/government/publications/independent-inquiry-into-inequalities-in-health-report [Accessed 29 December 2020]. [Google Scholar]

- 16.McIntosh Gray A. Inequalities in health. The black report: A summary and comment. Int J Heal Serv 1982;12:349–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cookson R, Propper C, Asaria M, Raine R. Socio-Economic Inequalities in Health Care in England. Fisc Stud 2016;37:371–403. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cheetham M, Moffatt S, Addison M, Wiseman A. Impact of Universal Credit in North East England: A qualitative study of claimants and support staff. BMJ Open 2019;9:29611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moffatt S, Lawson S, Patterson R, et al. A qualitative study of the impact of the UK ‘bedroom tax’. J Public Health (Oxf) 2016;38:197–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lambert MF, Sowden S. Revisiting the risks associated with health and healthcare reform in England: Perspective of Faculty of Public Health members. J Public Health (Oxf) 2016;38:e438–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.NHS England . The NHS Long Term Plan. NHS, 2019. www.longtermplan.nhs.uk [Accessed 09 July 2019]. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barr B, Higgerson J, Whitehead M. Investigating the impact of the English health inequalities strategy: Time trend analysis. BMJ 2017;358:j3310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Robinson T, Brown H, Norman PD, et al. The impact of New Labour's English health inequalities strategy on geographical inequalities in infant mortality: A time-trend analysis. J Epidemiol Community Health 2019;73:564–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.NHS England . Second Phase of the NHS Response to COVID-19. NHS, 2020. www.gov.uk/government/publications/wuhan-novel-coronavirus [Accessed 03 May 2020]. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brennan S. NHSE recommends law to abolish CCGs by 2022. HSJ; 2020. www.hsj.co.uk/commissioning/nhse-recommends-law-to-abolish-ccgs-by-2022/7029054.article [Accessed Nov 30, 2020]. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alderwick H. NHS reorganisation after the pandemic. BMJ 2020;371:m4468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vize R. Controversial from creation to disbanding, via e-cigarettes and alcohol: an obituary of Public Health England. BMJ 2020;371:m4476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Public Health England . Local action on health inequalities Understanding and reducing ethnic inequalities in health. PHE, 2018. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/730917/local_action_on_health_inequalities.pdf [Accessed 10 September 2019]. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Public Health England, Institute of Health Equity . Promoting good quality jobs to reduce health inequalities. PHE, 2015. www.instituteofhealthequity.org/resources-reports/local-action-on-health-inequalities-promoting-good-quality-jobs-to-reduce-health-inequalities-/local-action-on-health-inequalities-promoting-good-quality-jobs-to-reduce-health-inequalities-full-report.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 30.Public Health England . Supporting the health system to reduce inequalities in screening PHE Screening inequalities strategy Public Health England leads the NHS Screening Programmes. PHE, 2018. https://phescreening.blog.gov.uk/wp-content/uploads/sites/152/2018/03/Supporting-the-health-system-to-reduce-inequalities-in-screening.pdf [Accessed 12 June 2019]. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Public Health England . Health Equity Assessment Tool [HEAT]. PHE, 2020. www.gov.uk/government/publications/health-equity-assessment-tool-heat [Accessed 10 November 2020]. [Google Scholar]

- 32.The Academy of Medical Sciences . Improving the health of the public by 2040. The Academy of Medical Sciences, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Strategic Coordination of the Health of the Public Research committee . Health of the public research principles and goals. SCHOPR, 2019. https://acmedsci.ac.uk/file-download/70826993 [Accessed 28 December 2020]. [Google Scholar]

- 34.The Academy of Medical Sciences . Future arrangements for prevention, health improvement and health protection. The Academy of Medical Sciences, 2020. https://acmedsci.ac.uk/file-download/90869115 [Accessed 29 December 2020]. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Royal College of Physicians . Inequalities in Health Alliance. RCP, 2020. www.rcplondon.ac.uk/projects/inequalities-health-alliance [Accessed 29 December 2020]. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Blackman T, Harrington B, Elliott E, et al. Framing health inequalities for local intervention: comparative case studies. Sociol Health Illn 2012;34:49–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ford J. Director's appointment should be used to reframe the debate around health inequalities. HSJ; 2020. www.hsj.co.uk/leadership/directors-appointment-should-be-used-to-reframe-the-debate-around-health-inequalities/7028959.article [Accessed 29 December 2020]. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Green L. The concept of fatalism and New Labour's role in tackling inequalities. Br J Community Nurs 2001;6:106–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schrecker T. Was Mackenbach right? Towards a practical political science of redistribution and health inequalities. Heal Place 2017;46:293–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Scott-Samuel A, Smith KE. Fantasy paradigms of health inequalities: Utopian thinking? Soc Theory Heal 2015;13:418–36. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Katz M. The Undeserving Poor: From the War on Poverty to the War on Welfare. New York: Pantheon, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Smith KE, Anderson R. Understanding lay perspectives on socioeconomic health inequalities in Britain: a meta-ethnography. Sociol Health Illn 2018;40:146–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Parry J, Mathers J, Laburn-Peart C, Orford J, Dalton S. Improving health in deprived communities: What can residents teach us? Crit Public Health 2007;17:123–36. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Davidson R, Mitchell R, Hunt K. Location, location, location: The role of experience of disadvantage in lay perceptions of area inequalities in health. Heal Place 2008;14:167–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mackenzie M, Collins C, Connolly J, Doyle M, McCartney G. Working-class discourses of politics, policy and health: ‘I don't smoke; I don't drink. The only thing wrong with me is my health’. Policy Polit 2017;45:231–49. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bambra C, Norman P, Johnson NPAS. Visualising regional inequalities in the 1918 Spanish flu pandemic in England and Wales. Environ Plan A Econ Sp 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rich E, Miah A, Lewis S. Is digital health care more equitable? The framing of health inequalities within England's digital health policy 2010–2017. Sociol Health Illn 2019;41:31–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sowden SL, Raine R. Running along parallel lines: How political reality impedes the evaluation of public health interventions. A case study of exercise referral schemes in England. J Epidemiol Community Health 2008;62:835–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sadare O, Williams M, Simon L. Implementation of the Health Equity Impact Assessment [HEIA] tool in a local public health setting: challenges, facilitators, and impacts. Can J Public Heal 2020;111:212–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cookson R, Griffin S, Norheim O, Culyer A. Distributional cost-effectiveness analysis. Oxford University Press, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pons-Vigués M, Diez È, Morrison J, et al. Social and health policies or interventions to tackle health inequalities in European cities: A scoping review. BMC Public Health 2014;14:198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.McCartney G, Collins C, Mackenzie M. What [or who] causes health inequalities: Theories, evidence and implications? Health Policy 2013;113:221–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Barr B, Bambra C, Whitehead M, Duncan WH. The impact of NHS resource allocation policy on health inequalities in England 2001-11: Longitudinal ecological study. BMJ 2014;348:g3231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Levene LS, Baker R, Bankart J, Walker N, Wilson A. Socioeconomic deprivation scores as predictors of variations in NHS practice payments: A longitudinal study of English general practices 2013-2017. Br J Gen Pract 2019;69:E546–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lorenc T, Petticrew M, Welch V, Tugwell P. What types of interventions generate inequalities? Evidence from systematic reviews. JECH 2013;67:190–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.White M, Adams J, Heywood P. How and why do interventions that increase health overall widen inequalities within populations? In: Babones S. (ed). Social inequality and public health. Policy Press, 2009:64–81. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kelly MP, Barker M. Why is changing health-related behaviour so difficult? Public Health 2016;136:109–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Graham H. Women, Smoking and Disadvantage. In: Slama K. (ed). Tobacco and health. Springer, 1995:695–7. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Thirlway F. Explaining the social gradient in smoking and cessation: the peril and promise of social mobility. Sociol Health Illn 2020;42:565–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cheetham M, Gorman S, Gibson E, Wiseman A. It's not about telling people to eat better, stop smoking or get on the treadmill. In: Newbury-Birch D, Allan K. Co-creating and co-producing research evidence. Routledge, 2019:66–77. [Google Scholar]