Editor – What is the impact of changing anticoagulation from warfarin to direct-acting oral anticoagulants (DOAC) on the carbon footprint (CF) of the elective direct current cardioversion (EDCCV) care pathway (supplementary material S1; Fig S1)?

Methods

After Integrated Research Application System (230497), institutional approval (RHM-CR10347) and patient consent, we recruited all patients presenting for EDCCV under general anesthesia at University Hospital Southampton NHS Foundation Trust (UHS) between 2012–2017. Prospectively, data from 22 patients were analysed: mode of transport to their general practitioner and UHS, anaesthesia drugs, disposables, oxygen, waste generation and time spent in hospital for EDCCV were obtained and applied retrospectively. From the information systems, correspondence, attendance, duration of stay, clinical activity and pathology data was obtained, extracted, anonymised and encrypted. We calculated all relevant distances, (supplementary material S1; Tables S1 and S2) and incorporated these into Sustainable Care Pathway Guidance (SCPG).1 Pooled data for DOAC treated patients were compared with warfarin treated patients using the Mann–Whitney U test.

Study answer and limitations

Supplementary material S1, Fig S2 illustrates patient flow. In the prospective limb, 21 travelled to hospital and 14 to their GP surgery by fossil fuelled cars. Median age was 68 years (interquartile range (IQR) 61–73; range 22–89), 71.6% were men and 204 were receiving DOACs at the time of the EDCCV.

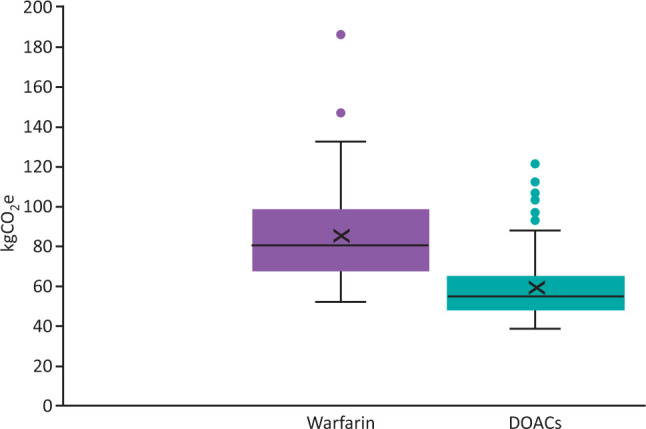

DOAC treated patients spent less time on the care pathway, made fewer visits to GP and hospital, travelled less and had fewer coagulation studies. The median equivalent carbon dioxide (CO2e) was 58.16 kg vs 85.49 kg for the warfarin group (p<0.0001; Table 1; Fig 1).

Table 1.

Warfarin and DOAC treated groups

| Warfarin, n=95 | DOACs, n=204 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median | Range | IQR | Median | Range | IQR | p | |

| Time from referral to DCCV, months | 5 | 2–24 | 3–6 | 4 | 1–12 | 3–6 | 0.002 |

| GP visits, n | 6 | 3–20 | 4–9 | 1 | 1 | 1–1 | <0.001 |

| UHS visits, n | 4 | 2–6 | 4–5 | 4 | 2–6 | 3–4 | 0.003 |

| Total distance travelled, km | 51.86 | 10.65–343.80 | 34.63–99.7 | 38.80 | 5.95–316.75 | 21.96–83 | <0.001 |

| Coagulation studies, n | 6 | 4–26 | 5–11 | 1 | 1–1 | 1–1 | <0.001 |

| Travel-related CF, kgCO2e | 12.58 | 2.58–83.37 | 8.38–24.18 | 9.41 | 1.44–76.8 | 5.32–20.13 | <0.001 |

| Total CF, kgCO2e | 85.49 | 52.07–185.55 | 67.39–97.29 | 58.16 | 38.26–120.98 | 64.17–47.81 | <0.0001 |

| CO2e expressed as equivalent car travel for the whole care pathwaya | 534 | 325–1160 | 363 | 239–756 | |||

aEquivalent car distance travelled assumes 160 gCO2/km. CF = carbon footprint; DOAC = direct acting oral anticoagulant; DCCV = direct current cardioversion; GP = general practitioner; IQR = interquartile range; kgCO2e = kg carbon dioxide equivalence; UHS = University Hospital Southampton NHS Foundation Trust.

Fig 1.

Total kgCO2e of the care pathways for warfarin vs DOAC treated patients. DOACs = direct acting oral anticoagulants (and includes the pooled results from the patients receiving rivaroxaban, apixaban and dabigatran).

Between 2012–2017, DOAC treatment required less stringent monitoring of anticoagulation with less visits, travelling, sample transportation and processing. The CO2e of anaesthesia-related single use items was taken as 420 g/£ spent irrespective of anticoagulation.2 The CO2e of DOAC procurement was not available from the manufacturers, but we estimate a month's apixaban therapy to be 100 g (1 km in a small car).3–5

Building energy use was apportioned for the duration of stay and was 233 kWh/bed/day and contributed 17.11 kg for both groups.6

What this study adds

SCPG avoids time-consuming and costly life cycle assessments, yet provides the framework to map clinical care. The change from warfarin to DOACs reduced the CF of the EDCCV care pathway for patients attending our hospital.

Supplementary material

Additional supplementary material may be found in the online version of this article at www.rcpjournals.org/fhj:

S1 – Supplemental tables and figures.

Acknowledgement

The authors gratefully acknowledge the help and support provided by Simon Aumônier of ERM, Oxford, UK.

References

- 1.NHS . Care pathways: Guidance on appraising sustainability. NHS, 2015. %%%www.sduhealth.org.uk/documents/publications/2015/CSPM%20Care%20Pathways%20Guidance/Sustainable_Care_Pathways_Guidance_-_Main_Document_-_Oct_2015.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 2.NHS . Identifying high greenhouse gas intensity prescription items. NHS, 2014. www.sduhealth.org.uk/documents/publications/2014/GHG_Prescription_Feb_2014.pdf [Accessed 19 November 2020]. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Parvatker A, Tunceroglu H, Sherman JD, et al. Cradle-to-gate greenhouse gas emissions for twenty anaesthetic active pharmaceutical ingredients based on process scale-up and process design calculations. ACS Sustainable Chem Eng 2019;7:6580–91. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bhonoah Y. Synthesis. www.ch.ic.ac.uk/local/projects/bhonoah/synthesis.html (Accessed 20/01/21).

- 5.Mali AC, Deshmukh DG, Joshi DR, et al. Facile approach for the synthesis of rivaroxaban using alternate synthon: reaction, crystallization and isolation in single pot to achieve desired yield, quality and crystal form. Sustain Chem Process 2015;3:11. [Google Scholar]

- 6.NHS . Estates Returns Information Collection, England, 2017-18. NHS, 2018. https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/estates-returns-information-collection/summary-page-and-dataset-for-eric-2017-18#resources [Accessed 30 July 2019]. [Google Scholar]