Abstract

The current therapeutic approach to asthma focuses exclusively on targeting inflammation and reducing airway smooth muscle force to prevent the recurrence of symptoms. However, even when inflammation is brought under control, airways in an asthmatic can still hyperconstrict when exposed to a low dose of agonist. This suggests that there are mechanisms at play that are likely triggered by inflammation and eventually become self-sustaining so that even when airway inflammation is brought back under control, these alternative mechanisms continue to drive airway hyperreactivity in asthmatics. In this study, we hypothesized that stiffening of the airway extracellular matrix is a core pathological change sufficient to support excessive bronchoconstriction even in the absence of inflammation. To test this hypothesis, we increased the stiffness of the airway extracellular matrix by photo-crosslinking collagen fibers within the airway wall of freshly dissected bovine rings using riboflavin (vitamin B2) and Ultraviolet-A radiation. In our experiments, collagen crosslinking led to a twofold increase in the stiffness of the airway extracellular matrix. This change was sufficient to cause airways to constrict to a greater degree, and at a faster rate when they were exposed to 10−5 M acetylcholine for 5 min. Our results show that stiffening of the extracellular matrix is sufficient to drive excessive airway constriction even in the absence of inflammatory signals.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY Targeting inflammation is the central dogma on which current asthma therapy is based. Here, we show that a healthy airway can be made to constrict excessively and at a faster rate in response to the same stimulus by increasing the stiffness of the extracellular matrix, without the use of inflammatory agents. Our results provide an independent mechanism by which airway remodeling in asthma can sustain airway hyperreactivity even in the absence of inflammatory signals.

Keywords: asthma, airway hyperreactivity, airway remodeling, collagen remodeling, extracellular matrix

INTRODUCTION

Asthma is a debilitating respiratory disease that adversely affects the lives of over 300 million people worldwide (1). Airways in an asthmatic are prone to sudden, exaggerated narrowing in response to a low concentration of inhaled airway smooth muscle (ASM) agonist. A low dose of inhaled agonist that evokes little to no response in a healthy individual can cause airways to hyperconstrict in an asthmatic (2). However, the exact mechanisms that trigger a healthy airway to become hypercontractile are not known. There is a consensus in the field that sustained inflammatory signals acting on the ASM play an important role in the development of hypercontractile airways. As such, the treatment of asthma over the past several decades has focused on using a combination of anti-inflammatory drugs, to reduce airway inflammation, and bronchodilators that cause relaxation of the ASM. This therapeutic strategy is only aimed at disease management and many patients with asthma remain poorly controlled (3). Even when inflammation is brought back under control, airways in an asthmatic can still hyperconstrict to a low dose of inhaled contractile agonist (4, 5). This suggests that there are alternative mechanisms at play that are likely triggered by inflammation and eventually become self-sustaining. Although airway inflammation can be resolved using anti-inflammatory therapies, these alternative mechanisms may be sufficient to drive airway hyperreactivity (AHR) in asthmatics. In this study, we examined whether an increase in the stiffness of the extracellular matrix (ECM) within airways would be sufficient to drive excessive airway constriction in the absence of inflammatory signals.

From in vitro studies, we know that the ECM plays a critical role in regulating agonist-induced Ca2+ oscillations in smooth muscle cells (6). Bronchial smooth muscle cells from healthy human donors exposed to a low dose of contractile agonist exhibit a calcium response consistent with a significantly higher agonist dose when the stiffness of the underlying ECM is increased (6). Similarly, mechanobiological interactions between the ASM and a stiff environment have been shown to lead to ASM hypercontractility (7, 8), ASM hyperplasia (9), and remodeling that continues unabated by bronchodilators or glucocorticoids (10), all of which are characteristic features of asthma. Despite the wealth of data at the cellular level, the potential role of ECM stiffening in driving the development of AHR in asthma has never been tested experimentally at the level of an airway. Among the multitude of proteins, proteoglycans, and glycoproteins that make up the airway ECM, collagen is the most critical determinant of ECM stiffness and failure strain in lung tissue (11). In this study, we increased the stiffness of airway ECM by crosslinking collagen fibers within the airway wall using riboflavin (vitamin B2) and Ultraviolet-A radiation (UV-A). This collagen crosslinking procedure is a well-established method for increasing ECM stiffness in multiple tissue types (12–14) and is routinely used in a clinical setting to increase the stiffness of collagen within the human cornea (13).

We found that a healthy airway can be made hyperreactive simply by increasing the stiffness of the ECM in the airway wall. Our data demonstrate that airway remodeling which leads to an increase in the stiffness of the ECM is sufficient to drive excessive airway constriction, even in the absence of inflammatory triggers. Our results highlight the need for therapeutic approaches that target ECM remodeling in asthma.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Tissue Preparation

Bovine lungs were obtained from a local slaughterhouse (Research 87, Boylston, MA) immediately after death and placed on ice. The main stem bronchus of the lung (generations 18–24) was dissected free of parenchymal tissue, and bronchial airway rings ∼1–3 mm in diameter with an average thickness of 3.2 ± 0.50 mm were cut from the bronchus for imaging. Tissue specimens were kept in a heated water bath at 37°C in warmed Krebs solution (in mM: 118 NaCl, 4.7 KCl, 1.2 MgSO4,·7H2O, 25 NaHCO3, 1.2 KH2PO4, 11 Glucose, and 2.5 CaCl2). Tissue viability was then confirmed by subjecting the airway rings to electric field stimulation (EFS) (15, 16). Platinum wires were placed on either side of the airway samples in warmed Krebs solution and a 20 V, 100 Hz square wave EFS pulse train was applied for 10 s. The airway tissue samples used in this study were taken from three sets of bovine lungs. This study was carried out in accordance with the guidelines and regulations approved by the Institutional Biosafety Committee at Northeastern University.

Experimental Setup

During our experiments, airway rings were left freely floating in a 40-mm interchangeable coverslip dish (#190130, Bioptech Inc., Butler, PA) filled with 3 mL of warm Krebs solution. A tabletop microscope equipped with a camera (Dino-Lite Edge AM7115 Series, AnMo Electronics Corp., Taiwan) was positioned above the dish housing the airway rings to capture videos of constriction. The temperature of the solution in the dish was maintained at 37°C with a hot plate throughout the entirety of each experiment. Between constriction experiments, airway rings were kept in six-well plates in an incubator kept at 5% CO2 to maintain the pH of the Krebs solution. During EFS stimulation of airway rings, platinum wires were placed in the dish on either side of the samples and a 20 V, 100 Hz square wave EFS pulse train was applied for 10 s.

Measurement of Airway Reactivity

Viable airway rings were subjected to a dose of 10−5 M acetylcholine (ACh) and allowed to freely constrict. The constricting airway rings were imaged at a rate of 10 frames/s using a tabletop microscope, and two separate videos were captured. The first video corresponded to a 30-s recording of the airway ring at baseline. The airway ring was then exposed to ACh and the constricting airway ring was imaged for 5 min, which is the typical time needed for an airway to fully constrict in response to ACh (16). The resulting image sequences were analyzed using a custom MATLAB image processing algorithm which outlines the inner lumen of the airway ring in each frame. The algorithm returns the inner luminal area of the constricting airway ring as a function of time. The time t = 0 corresponds to the time at which the airway ring is first exposed to ACh. The inner luminal area of the airway segment at baseline (Abaseline) was calculated by averaging area measurements taken during the last 5 s of the baseline video recording. Area measurements collected during the last 5 s of the constriction video recording were averaged to calculate the final constricted inner luminal area (Aconstricted). From these two measurements, we calculate the reactivity of an airway ring, ξ, as the fractional change in the inner luminal area of the airway ring:

| (1) |

Increasing the Stiffness of the Airway ECM

Here, we crosslink collagen fibers using riboflavin (vitamin B2) and UV-A light to increase the stiffness of the airway ECM. The wavelength of UV-A light used for these experiments was 365 nm. Collagen crosslinking with riboflavin and UV-A treatment is a well-established technique used to increase ECM stiffness in multiple tissue types (12–14, 17) and is commonly used in human corneal surgery to increase the stiffness of collagen in the corneal ECM. Once the pretreatment airway reactivity was recorded, airway rings were washed five times to remove any remaining ACh and allowed to return to their baseline (unconstricted) state. The airway rings were then immersed in a 1% (w/v) solution of riboflavin (#R9504, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) diluted in warm Krebs for 5 min. Following riboflavin treatment, the airway rings were moved to fresh, warmed Krebs solution and exposed to UV-A light for 15 min (Blak-Ray Lamp, Model XX-15BLB, 115 V, 60 Hz, 0.68 Amps). The intensity of the UV-A light used for experiments was measured at 2.69 mW/cm2 using a UV intensity meter (OAI Instruments, Milpitas, CA, Model 0308-0000-01). After 15 min of UV-A exposure, the tissue was again washed five times in fresh, warmed Krebs solution and tested for viability using EFS. None of the airway ring samples we used in our experiments failed this viability test. Using the same procedure described in the Measurement of airway reactivity, we then measured airway reactivity (Eq. 1). The entire protocol used for collagen crosslinking is summarized in Fig. 1. To test the possibility that the first airway constriction did not introduce any alterations in the airway wall that made it possible for the airway to constrict more in response to the second application of ACh, we performed time-controlled airway reactivity experiments. These experiments followed the same protocol displayed in Fig. 1B, however, airway rings were not treated with riboflavin and UV-A.

Figure 1.

Schematic showing the experimental protocol for measuring the extracellular matrix (ECM) stiffness of airway rings before and after crosslinking of collagen (A) and measuring the reactivity of airway rings to a fixed dose of contractile agonist (10−5 M ACh) (B).

Measurement of ECM Stiffness in Airway Rings

To measure the stiffness of the airway ECM, airway rings were first treated with 10−5 M cytochalasin D for 1 h. Cytochalasin D is a specific inhibitor of actin polymerization in cells, which acts on the positive ends of actin filaments to prevent both the association and dissociation of actin monomers (18). One hour of cytochalasin D treatment disrupts the actin cytoskeleton and significantly decreases the contribution of cells to total tissue stiffness (19). The stiffness of airway rings measured after cytochalasin D treatment represents the upper bound of airway ECM stiffness. A detailed description of why we chose to measure ECM stiffness in this manner over alternative methods can be found in discussion.

After 1 h of cytochalasin D exposure, airway rings were mounted in a uniaxial tissue stretcher setup (model 300 C, Aurora Scientific, ON, Canada) in 20 mL of warm Krebs solution to measure Young’s modulus of the tissue. A detailed description of the protocol and our experimental setup can be found in Polio et al. (8). Briefly, after preconditioning each airway ring to eliminate prior stretch history, each airway ring was stretched in the radial direction to a maximal strain of 80%–100%, then back to 0% using a triangular displacement waveform lasting 60 s. The strain was calculated using the length imposed by the lever arm, d, and the undeformed inner diameter of each airway ring, d0, using Eq. 2:

| (2) |

Following force measurements, the longitudinal length l and wall thickness w of each airway ring was measured. The force F, generated by the stretching of the airway rings after 1 h of cytochalasin D treatment was used to calculate airway wall stress, σ, using Eq. 3:

| (3) |

Once the stress-strain curve was generated for each airway ring, Young’s modulus E was calculated at 60% radial strain by calculating the instantaneous slope of the stress-strain curve using Eq. 4:

| (4) |

Pretreatment measurements represent the ECM stiffness of airway rings treated with cytochalasin D for 1 h before riboflavin and UV-A treatment, and posttreatment measurements represent the same measurements collected after riboflavin and UV-A treatment.

Measurement of Contractile Force in Airway Rings

Airway rings were imaged using a tabletop microscope (Dino-Lite Edge AM7115 Series, AnMo Electronics Corp., Taiwan) to measure the inner luminal diameter. Next, airway rings were mounted on the uniaxial tissue stretcher system in 20 mL of warmed Krebs solution and preconditioned according to the same protocol outlined in the previous section. After preconditioning, airway rings were stretched and held fixed at 20% strain for 5 min to allow the airway to reach an equilibrium isometric force. Stretched airway rings were then exposed to a 20 V, 100 Hz square wave EFS pulse train for 10 s and allowed to relax for 60 s, then the process was repeated two more times. Airway rings were left to return to their baseline state for 7 min after EFS, then 10−5 M ACh was added to the Krebs solution and the isometric force generated by the airway rings during constriction was recorded for 5 min. The baseline force of each airway ring was calculated by averaging the last 5 s of force measurements collected before the addition of ACh, and the active force was calculated by averaging the last 5 s of force measurements recorded after ACh exposure. Pretreatment measurements represent force measurements collected before riboflavin and UV-A treatment, whereas posttreatment measurements reflect the same measurements repeated after riboflavin and UV-A treatment. Control isometric force measurements were collected using the same experimental protocol outlined in this section, however, the airway rings in control experiments were not treated with riboflavin and UV-A.

Measurement of Airway Ring Viability after Riboflavin and UV-A Treatment

To assess whether riboflavin and UV-A treatment had any significant effect on tissue viability, airway rings were incubated with Ethidium homodimer-1 (EthD-1) at a concentration of 2 µM in warmed Krebs solution for 30 min at 37°C. After 30 min, airway rings were washed three times in warmed Krebs solution and cell nuclei were stained with NucBlue LiveReady Probes Hoechst 33342 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) at a concentration of 2 drops/mL. Sample images were acquired using a Zeiss LSM-800 confocal microscope (405 nm/561 nm) at 2% laser power with an EC Plan-Neofluar ×10/0.3 objective. Images were split into separate channels and a threshold was applied based on pixel intensity to identify cell nuclei. EthD-1 was used to label the nuclei of dead cells whereas NucBlue stained the nuclei of both live and dead cells. The dead cells were identified as the nuclei marked by EthD-1 expression. Live cells were identified as the nuclei which had NucBlue expression but did not express EthD-1. Cellular viability was calculated for each image as the ratio of live to dead cells in each image. We thank the Institute for Chemical Imaging of Living Systems at Northeastern University for consultation and imaging support.

Statistical Testing

Sigmastat (Systat Software, San Jose, CA) was used to perform statistical testing of experimental data. The specific tests used to determine statistical significance, the number of airway rings (n), and the P-value are described along with the corresponding results. Data in the Results section is presented as means ± SD for normally distributed data. For data that failed the normality test, the median of the data is also included. A P-value of 0.05 was used as a threshold for a statistically significant difference between data sets.

RESULTS

Crosslinking of Collagen with Riboflavin and UV-A Increases the Stiffness of the Airway ECM

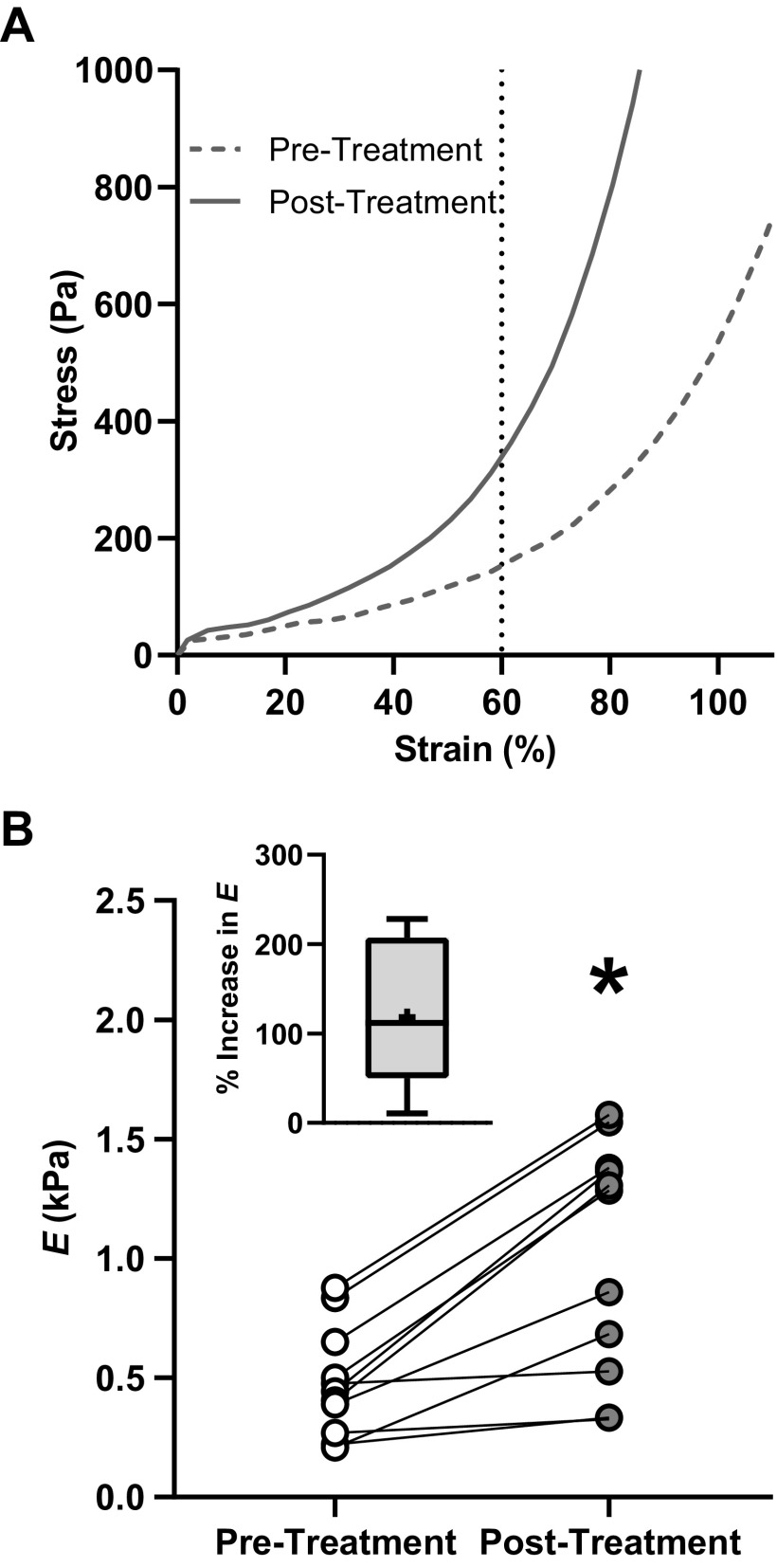

To measure changes in the stiffness of the airway ECM due to collagen crosslinking, airways rings were exposed to cytochalasin D for 1 h and Young’s modulus E of each airway ring was measured before and after riboflavin and UV-A treatment. A typical stress-strain curve of an airway ring exposed to cytochalasin D before (pretreatment) and after (posttreatment) riboflavin and UV-A treatment is shown in Fig. 2A. The stress that develops in the airway tissue is predominantly due to the extracellular components in the airway wall (primarily collagen).

Figure 2.

A: stress-strain curves of an airway ring exposed to 10−5 M cytochalasin D for 1 h before (dashed dark gray line) and after (dark gray line) treatment with riboflavin and UV-A. The Young’s modulus, E, was calculated as the slope of the stress-strain curve at 60% radial strain. Exposure to cytochalasin D reduces the contribution of the cells to the total tissue stiffness to negligible levels, therefore, the value of E measured here represents extracellular matrix (ECM) stiffness. B: following collagen crosslinking, E increased for all airway ring samples tested (dark gray circles, n = 9). The effect was statistically significant (P < 0.001, paired t test, n = 9). The percentage increase in E is shown in the inset figure. n, number of airway rings tested; *statistical significance (P < 0.05).

Young’s modulus, E, of the airway ECM increased following riboflavin and UV-A treatment (Fig. 2B). The results from a paired t test demonstrated a significant increase in E from 479.4 ± 226.4 Pa (pretreatment) to 1,021.4 ± 487.6 Pa (posttreatment, n = 9, P < 0.001). The pretreatment median of E was 444.3 Pa and the posttreatment median was 1,284.1 Pa. The increase in stiffness due to riboflavin and UV-A treatment was highly reproducible, and all the treated airway rings demonstrated an increase in ECM stiffness. Across all the samples tested, the mean percentage increase in ECM stiffness following riboflavin and UV-A treatment was 118.2% (Fig. 2B, inset).

Collagen Crosslinking Leads to a Higher Degree of Airway Constriction in Response to the Same Dose of Contractile Agonist

To measure agonist-induced airway constriction, we first applied a 10 s EFS pulse train to test the viability of the airway tissue (Fig. 1B). EFS pulses cause nerve endings in freshly dissected airways to release ACh, causing the airway to constrict (20, 21). All airway ring samples constricted in response to EFS both before and after riboflavin and UV-A treatment. The mean reactivity of airway rings in response to EFS before treatment with riboflavin and UV-A was 75.4% ± 15.2% (n = 9), and 86.6% ± 14.0% (n = 9) after treatment, indicating that the airway rings were viable throughout the course of our experiments.

To measure the change in reactivity for a given dose of contractile agonist, we exposed airway ring samples to 10−5 M ACh before and after riboflavin and UV-A treatment. In untreated airway rings, we found that exposure to this concentration of ACh caused moderate constriction (ξ = 29.6% ± 31.9%, median ξ = 23.7%, n = 9). The degree to which the airway rings constricted to the same dose of agonist (10−5 M ACh) changed significantly after collagen was cross linked in the same airway rings. The time course of change in the inner luminal area of an airway ring after adding 10−5 M ACh, before and after collagen crosslinking is shown in Fig. 3A. The baseline and constricted inner luminal area of each airway ring (n = 9) before and after collagen crosslinking is shown in Fig. 3B. Before treatment, the luminal area of airway rings decreased from 1.22 mm2 (pretreatment baseline area, median = 0.85 mm2, white circles, n = 9) to 0.92 mm2 (pretreatment constricted area, median = 0.71 mm2, white triangles, n = 9) in response to 10−5 M ACh. The same airway rings experienced a decrease in the luminal area from 1.57 mm2 (posttreatment baseline area, dark gray circles, n = 9) to 0.56 mm2 (posttreatment constricted area, dark gray triangles, n = 9) after riboflavin and UV-A treatment. The decrease in the luminal area of airways due to ACh exposure was statistically significant before (P = 0.008, Wilcoxon Signed Rank test, n = 9) and after (P = 0.004, paired t test, n = 9) treatment. After collagen crosslinking, airway rings exposed to the same dose of ACh (10−5 M) exhibited a substantial increase in reactivity from ξ = 29.6% ± 31.9% (pretreatment, white triangles, n = 9), to ξ = 74.7 ± 28.9 (posttreatment, dark gray triangles, n = 9) (Fig. 3C). We found that collagen crosslinking led to a statistically significant increase in airway reactivity ξ for the same dose (10−5 M) of contractile agonist (P ≤ 0.001, paired t test, n = 9). Without riboflavin and UV-A treatment, airway reactivity was ξ = 18.7% ± 8.8% (1st constriction, white triangles, n = 8) for the first constriction and ξ = 19.2% ± 8.7% (2nd constriction, dark gray triangles, n = 8) for the second constriction (Fig. 3D). Untreated airway rings did not exhibit a significant increase in reactivity (P = 0.751, paired t test, n = 8). Based on these time control experiments, we confirmed that the increase in airway reactivity was the result of riboflavin and UV-A treatment and not prior exposure to agonist or an increase in tissue compliance from the first constriction.

Figure 3.

A: change in inner luminal area of an airway ring with respect to time after addition of 10−5 M ACh before (white circles) and after (dark gray circles) collagen crosslinking. B: the baseline and constricted inner luminal area of each airway ring (n = 9) before (white) and after collagen crosslinking (dark gray). The decrease in the luminal area due to ACh exposure was statistically significant for pretreatment (P = 0.008, Wilcoxon Signed Rank test, n = 9) and posttreatment (P = 0.004, paired t test, n = 9) airway rings. C: box plots of airway reactivity, ξ. After collagen crosslinking, airway rings exposed to the same low dose of ACh (10−5 M) exhibited a substantial increase in reactivity from ξ = 29.6% ± 31.9%, (pretreatment, white triangles, n = 9) to ξ = 74.7% ± 28.9%, (posttreatment, dark gray triangles, n = 9). The effect was statistically significant (P ≤ 0.001, paired t test, n = 9). D: box plots of airway reactivity for time control experiments performed without riboflavin and UV-A treatment. Airway reactivity went from ξ = 18.7% ± 8.8%, (1st constriction, white triangles, n = 8) to ξ = 19.2% ± 8.7% (2nd constriction, dark gray triangles, n = 8), which was not statistically significant (P = 0.751, paired t test, n = 8). The sample number n represents the number of airway rings tested; *statistical significance (P < 0.05).

The variable ξ represents the fractional change in the inner luminal area of an airway ring in response to a contractile agonist. The use of fractional change in the luminal area is the most appropriate means of measuring the response of airways to agonists and is widely used in the literature (22, 23). However, the mathematical formulation of fractional measures makes them prone to bias due to differences in the baseline measure. In our case, ξ is sensitive to change in Abaseline before and after treatment with riboflavin and UV-A. A lower value of Abaseline posttreatment can lead to higher percent changes in the luminal area and confound our interpretation of the degree of airway reactivity. To test for the confounding effect of variations in Abaseline, we tested for statistical differences in the baseline (pre-ACh) inner luminal area of our airway rings before and after collagen crosslinking and found no difference in Abaseline (P = 0.331, paired t test, n = 9). In the supplementary information, we include two movies of the same airway ring narrowing in response to ACh before (Supplemental Video S1; see https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.12584633) and after (Supplemental Video S2; see https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.12584663) treatment with riboflavin and UV-A.

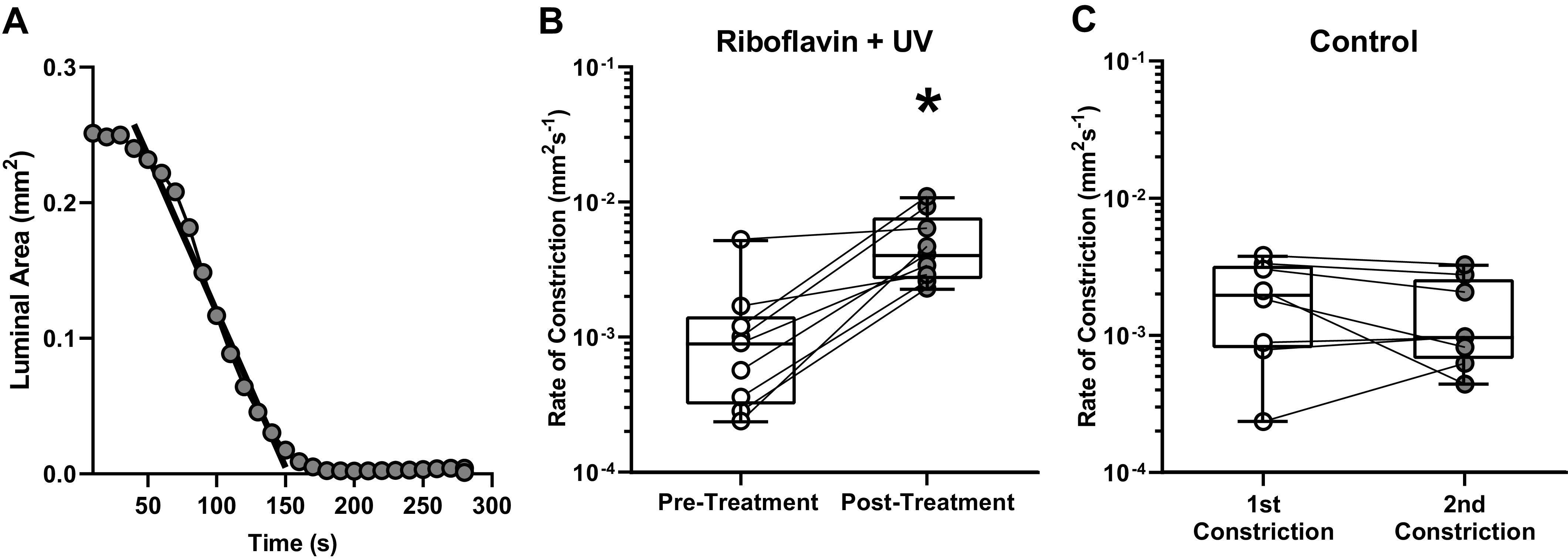

Collagen Crosslinking Increases the Rate of Airway Ring Constriction

To test how riboflavin and UV-A treatment affected the rate of airway ring constriction, the slope of a line that best fits the decrease in the inner luminal area of each airway ring was measured after exposure to 10−5 M ACh. Inner luminal area measurements were averaged over 10 s intervals, and constriction rates were calculated for airway rings before and after riboflavin and UV-A treatment. An example time course for an airway ring constricting in response to 10−5 M ACh after treatment, along with the best-fit line used to calculate the rate of constriction for the airway ring, is shown in Fig. 4A. The pretreatment and posttreatment rate of constriction for each airway ring is displayed in Fig. 4B. Every sample we tested demonstrated a faster rate of constriction in response to ACh after treatment with riboflavin and UV-A (1.28 ± 1.6 × 10−3 mm2/s, median = 0.90 × 10−3 mm2/s, pretreatment, n = 9 vs. 5.19 ± 3.1 × 10−3 mm2/s, median = 4.10 × 10−3 mm2/s, posttreatment, n = 9). Due to a lack of normality in the pretreatment and posttreatment constriction rates, a Wilcoxon Signed Rank test was performed. The difference in constriction rates due to collagen crosslinking was statistically significant (P = 0.004, Wilcoxon Signed Rank test, n = 9). The rates of constriction calculated from the first and second constriction for each control airway ring tested are shown in Fig. 4C. In untreated airway rings, constriction rates were similar for both constrictions (2.01 ± 1.3 × 10−3 mm2/s, 1st constriction, N = 8 vs. 1.49 ± 1.1 × 10−3 mm2/s, 2nd constriction, n = 8) and no statistical differences were detected (P = 0.078, paired t test, n = 8).

Figure 4.

A: an example time course for an airway ring after riboflavin and UV-A treatment, along with the best-fit line used to calculate the rate of constriction for the airway ring in response to 10−5 M ACh. Inner luminal area measurements were averaged over 10 s intervals, and constriction rates were calculated for airway rings before and after treatment. B: the pretreatment (white circles) and posttreatment (dark gray circles) rates of constriction in response to 10−5M ACh for each airway ring are shown. The difference in constriction rates due to collagen crosslinking was statistically significant (P = 0.004, Wilcoxon Signed Rank test, n = 9). C: the rates of constriction for control experiments performed with airway rings that were not treated with riboflavin and UV-A. The rate of constriction during the first constriction (white circles) was not statistically different from the rate during the second constriction (dark gray circles) in control airway rings (P = 0.078, paired t test, n = 8). n, number of airway rings tested; *Statistical significance (P < 0.05).

Collagen Crosslinking Leads to Higher Force Generation during Airway Ring Constriction

To test whether collagen crosslinking would cause airway rings to generate higher forces during constriction, isometric force experiments were performed on airway rings before and after treatment with riboflavin and UV-A. Airway rings were mounted on a uniaxial tissue stretcher system and held stretched at 20% strain, then left to relax for at least 5 min until reaching an equilibrium force. Next, airway rings were stimulated three times with an EFS pulse train for 10 s each with 1 min rest between each stimulation. After the last EFS pulse, airway rings were left for 7 min to relax and allow an equilibrium baseline force to be reached. Once the baseline force was recorded, airway rings were exposed to 10−5M ACh, and force measurements were collected for 5 min during constriction. An example time course for an isometric force experiment done with an airway ring before and after riboflavin and UV-A treatment is shown in Fig. 5A. The baseline force and the active force generated by each airway ring in response to ACh before (pretreatment, white) and after (posttreatment, dark gray) collagen crosslinking are shown in Fig. 5B. Before UV-A treatment, 10−5 M ACh increased the force generated by airway rings from 2.23 ± 0.34 mN (pretreatment baseline force, median = 2.08 mN, white circles, n = 10) to 2.84 ± 0.78 mN (pretreatment active force, median = 2.64 mN, white triangles, n = 10). After riboflavin and UV-A treatment, exposure to 10−5M ACh increased the force generated by airway rings from 2.20 ± 0.26 mN (posttreatment baseline force, dark gray circles, n = 10) to 3.87 ± 1.17 mN (posttreatment active force, dark gray triangles, n = 10). The increase in force generated by airway rings due to ACh exposure was statistically significant for pretreatment (P = 0.002, Wilcoxon Signed Rank test, n = 10) and posttreatment (P = 0.001, paired t test, n = 10) airway rings. In addition, riboflavin and UV-A treatment did not have a significant effect on the baseline force generated by the airway rings (P = 0.814, paired t test, n = 10). In Fig. 5C, the percentage increase from baseline force after ACh exposure for airway rings before (pretreatment, white triangles) and after (posttreatment, dark gray triangles) riboflavin and UV-A treatment are shown. Before riboflavin and UV-A treatment, the force generated by airway rings in response to 10−5 M ACh only increased 25.6% ± 16.6% (white triangles, n = 10) from baseline. However, after treatment the same dose of ACh caused airway rings to exhibit a 76.7% ± 55.0% increase in force from baseline, which marked a significant increase from pretreatment measurements (P = 0.006, paired t test, n = 10). The same experiments were performed in control airway rings, and the results from the first (1st constriction, white triangles, n = 8) and second (2nd constriction, dark gray triangles, n = 8) constrictions are displayed in Fig. 5D. When riboflavin and UV-A treatment was removed, the difference in the force increase from baseline generated by airway rings in response to ACh (27.3% ± 6.4%, 1st constriction vs. 25.9% ± 13.8%, 2nd constriction, n = 8) was not significant (P = 0.760, paired t test, n = 8).

Figure 5.

A: an example time course of an isometric force experiment for an airway ring before and after riboflavin and UV-A treatment. Airway rings were stimulated with EFS three times for 10 s and left to return to their baseline force, then exposed to 10−5M ACh for 5 min. B: the baseline force and active force generated by each airway ring in response to 10−5 M ACh (n = 10) before (white) and after (dark gray) collagen crosslinking. The increase in force due to ACh was statistically significant for pretreatment (P = 0.002, Wilcoxon Signed Rank test, n = 10) and posttreatment (P = 0.001, paired t test, n = 10) airway rings. C: the percentage increase from baseline force after ACh exposure for airway rings before (pretreatment, white triangles, n = 10) and after (posttreatment, dark gray triangles, n = 10) riboflavin and UV-A treatment. The difference in the percentage increase from baseline force after 5 min of ACh exposure between pretreatment and posttreatment airway rings was statistically significant (P = 0.006, paired t test, n = 10). D: the percentage increase from baseline force after ACh exposure in control airway rings that were not treated with riboflavin and UV-A. No statistical differences were observed between the first (white triangles, n = 8) and second constriction (dark gray triangles, n = 8) experiments (P = 0.760, paired t test, n = 8). n, number of airway rings tested; *statistical significance (P < 0.05).

To test whether collagen crosslinking led to any changes in the rate of force generation after agonist exposure, the slope of a line that best fit the increase in force generated by each airway ring was measured after exposure to 10−5M ACh. Force measurements were averaged over 10 s intervals, then the rate of force generation for airway rings was calculated before and after riboflavin and UV-A treatment. After collagen crosslinking the rate of force generation in airway rings increased from 1.53 ± 1.1 × 10−2 mN/s (pretreatment, median = 1.40 × 10−2 mN/s, n = 10) to 2.44 ± 1.6 × 10-2 mN/s (posttreatment, median = 1.91 × 10-2 mN/s, n = 10). Since the pretreatment and posttreatment data were not normally distributed, a Wilcoxon Signed Rank test was performed to test for statistical significance. The difference in the rate of force generation due to riboflavin and UV-A treatment was statistically significant (P = 0.027, Wilcoxon Signed Rank test, n = 10). In control airways, the rate of force generation was similar for both constrictions (1.62 ± 0.67 × 10−2 mN/s, 1st constriction, n = 8 vs. 1.77 ± 0.70 × 10−2 mN/s, 2nd constriction, n = 8) and no statistical differences were detected (P = 0.723, paired t test, n = 8).

Riboflavin and UV-A Treatment Does Not Affect Airway Viability

To confirm that airway ring viability was not impacted by riboflavin and UV-A treatment, control airway rings and riboflavin/UV-A-treated airway rings were stained with Ethidium homodimer-1 (EthD-1). EthD-1 binds to DNA in the nucleus when the cell membrane is compromised; therefore, it is a fluorescent indicator used to identify dead cells. In addition to EthD-1 staining, airways were stained with NucBlue LiveReady Probes Hoechst 33342 to identify where both live and dead cell nuclei were located within the airway tissue. Representative images of a control airway ring and an airway ring after riboflavin and UV-A treatment are displayed in Fig. 6, A and B, where EthD-1 expression is shown in pink and cell nuclei are shown in blue. Images were split into separate channels and a threshold was applied based on pixel intensity to identify the nuclei of cells. The dead cells were identified as the nuclei marked by EthD-1 expression. Live cells were identified as the nuclei which had NucBlue expression but did not express EthD-1. Cellular viability was calculated for each image as the ratio of live to dead cells in each image using a custom MATLAB program. A total of 22 images were captured from five different control samples, and on average control airways exhibited 65.5% ± 7.9% viability (Fig. 6C, white circles, n = 5). For airway rings treated with riboflavin and UV-A, 17 images were captured from three different airway rings with an average viability of 64.8% ± 12.6% (Fig. 6C, dark gray circles, n = 3). Treatment of airway rings with riboflavin and UV-A did not have a significant effect on airway ring viability (P = 0.920, t test, n > 3 airway rings).

Figure 6.

A: a representative image of an untreated airway ring after staining for cell nuclei (DAPI, blue) and dead cells (EthD-1, pink) acquired at ×10 magnification. B: a representative image of an airway ring after riboflavin and UV-A treatment. The arrows indicate the epithelium (yellow) and the smooth muscle layer (green) in each image. C: the percentage viability calculated for control airway rings (white circles, n = 5) and airway rings treated with riboflavin and UV-A (dark gray circles, n = 3). Viability measurements were calculated from 22 images across n = 5 control airway rings, and 17 images across n = 3 airway rings treated with riboflavin and UV-A. Treatment of airway rings with riboflavin and UV-A did not have a significant effect on airway ring viability (P = 0.920, t test, n ≥ 3 airways). n, number of airway rings tested.

DISCUSSION

Disruption of collagen homeostasis and excessive deposition of fibrillar collagen are characteristic structural changes found in the airways of asthmatics (18, 24). While these pathological alterations in the ECM are likely triggered by inflammation, these changes in the composition and rigidity of the extracellular component of the airway wall persist even when airway inflammation is brought under control. In this study, we hypothesized that increasing the stiffness of ECM within the airway wall is a pathological change sufficient to support excessive constriction of airways, even in the absence of inflammatory signals. To test this hypothesis, we employed a collagen crosslinking technique using riboflavin (vitamin B2) and UV-A light, which has been shown to increase the stiffness of the ECM within multiple tissue types (12, 13, 25). In our experiments, we were able to generate a twofold increase in the ECM stiffness of bovine airways (Fig. 2B). The goal here was not to recreate the pathophysiological process that occurs in asthma but to perturb the mechanical properties of the ECM without introducing any inflammatory signals to examine its impact on agonist-induced airway constriction. When we measured the degree of airway reactivity after ECM stiffening, we found that the airways constricted to a greater degree (Fig. 3C) and at a faster rate (Fig. 4B) in response to the same dose of contractile agonist. These results provide direct evidence that structural changes within the airway wall which result in a pathologically stiffer ECM are sufficient to support excessive bronchoconstriction, even in the absence of inflammation.

The ECM is often thought of as the load against which the smooth muscle constricts. As such, our finding that ECM stiffening can lead to increased airway contraction may seem contradictory. The apparent discrepancy here arises from the false notion that the force generated by the smooth muscle is independent of the material properties of the ECM. If this were true, then increased ECM stiffness should reduce the degree of airway constriction for a fixed dose of agonist. However, a growing body of experimental and modeling studies have shown that the mechanical properties of the ECM can regulate the force generated by the airway smooth muscle (6, 8, 26, 27). The ECM can control smooth muscle force through multiple mechanisms. In an isolated smooth muscle cell, mechanical interactions between the ECM and the actin cytoskeleton in the ASM can influence myosin-cycling causing the muscle to generate higher forces on a stiffer matrix (27). In multicellular ensembles of ASM cells as one finds in an airway, stiffening the ECM can alter the agonist-induced calcium oscillations in the ASM cells (6). Bronchial smooth muscle cells from healthy human donors exposed to a low dose of contractile agonist exhibit a calcium response and higher force consistent with a significantly higher agonist dose when the underlying ECM becomes stiffer (6). ECM stiffening can also change the way ASM cells connect with each other. On stiff matrix, ASM cells change their connectivity from cadherin-based direct cell-cell contacts to integrin-based cell-ECM connections (8). In all these mechanisms, the force generated by the ASM increases upon ECM stiffening. In the present study, we found that increasing the ECM stiffness of an airway using riboflavin and UV-A treatment led to a significant increase in the force generated by the smooth muscle (Fig. 5).

The role of collagen remodeling in asthma has been overlooked thus far because of the significant increase in ASM mass seen in fatal asthmatics (28). However, in fatal asthma, the volume of ECM within the airways is also significantly increased compared to healthy and mild asthmatics (28). Furthermore, second harmonic imaging of collagen structure in asthmatic airways has confirmed that the organization of collagen within the ASM layer of asthmatics is highly organized (24). Mechanically, such organized collagen fiber networks are associated with a high Young’s modulus (29, 30). This reasoning leads us to conclude that the ASM cells in severe asthmatics exist in a very stiff extracellular environment. From in vitro studies, we know that ASM cells become proliferative (9), and also generate more force for a given dose of agonist when cultured in stiff environments which mimic remodeled ECM (8). Despite clear evidence at the cellular level, the role of collagen stiffening in driving the development of AHR in asthma has never been experimentally tested at the airway level.

In this study, we measured ECM stiffness by measuring Young’s modulus of the airway tissue after 1 h of exposure to cytochalasin D. Cytochalasin D is a cell-permeable toxin that acts as a potent inhibitor of actin polymerization. By binding to the barbed (+) end of the actin filaments, cytochalasin D prevents the addition of actin monomers (31). The half-life of actin turnover in cells is ∼30 s (32). Therefore, treatment with cytochalasin D over the course of an hour is enough to disrupt the actin cytoskeleton within ASM cells (19). Since cell stiffness is primarily determined by cytoskeletal prestress, the contribution of cells to the total tissue stiffness in our measurements is negligible (25). Therefore, the measurements shown in Fig. 2B represent the upper bound of ECM stiffness in the airways. An alternative method for measuring ECM stiffness would have been to decellularize the airway tissue (8). While decellularization protocols can completely remove all the cells from the tissue, decellularization can also alter the ECM in tissue. In contrast, the activity of cytochalasin D is specific to actin in the cells. In addition, treatment with cytochalasin D is not known to affect ECM components. Regardless of the technique used to abrogate the contribution of cells to the total stiffness of the airway, the stiffness of the tissue should not be interpreted as a linear function of the cell and ECM stiffness. In situ, the cells attach and pull on nonlinearly elastic components of the ECM, such as collagen, increasing the stiffness of the ECM. At the moment, it is extremely challenging to account for this nonlinear interaction when estimating ECM stiffness using established experimental techniques.

The stiffness of airway ECM in healthy human lungs is size dependent. Small airways with an inner diameter of ≤ 3 mm, which are known to collapse in asthma, possess very soft ECM with Young’s modulus on the order of 1 kPa (8). If there is a triggering event, perhaps due to a brief period of airway inflammation, collagen is excessively deposited and remodeled within the ASM layer of an airway (33, 34). We recently demonstrated that an increase in matrix stiffness can cause ASM cells to lose direct cell–cell connections and form focal adhesions with collagen fibers in the underlying ECM. This ECM stiffness-induced switch in connectivity causes cells to generate higher forces, which are then transmitted through the collagen fibers (8). This change in the pathway of force transmission through collagen has two important and unexplored consequences for asthma progression. First, collagenase enzymes become ineffective at cleaving collagen fibers that carry tension (35–37), leading to a further increase in collagen levels within the ASM layer. Second, due to the strain stiffening properties of collagen, increased force transmission through fibers further increases collagen stiffness (38). Together, these two mechanisms can create a self-sustaining feedback loop that can promote pathological collagen remodeling and AHR development in the absence of sustained airway inflammation. This process is entirely driven by mechanical factors and can persist even when inflammation is brought under control. Thus, collagen remodeling in the airway can continue unabated by anti-inflammatory therapy (10).

Our results show that alterations in the mechanical properties of the ECM are sufficient to drive excessive airway constriction even in the absence of inflammatory signals. These results suggest that ECM remodeling may be a core pathological change that drives airway hyperreactivity in asthma and highlights the potential for targeting ECM remodeling as a therapy for this debilitating disease that affects over 300 million people worldwide.

GRANTS

This study was supported by the National Institute of Health Grants R00 HL122513 and R21 HL129468.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

J.W.R. and H.P. conceived and designed research; R.R.J., S.E.S., S.R.P., R.D.A., and C.A.M. performed experiments; R.R.J., J.W.R., and H.P. analyzed data; R.R.J., J.W.R., and H.P. interpreted results of experiments; R.R.J., S.E.S., and H.P. prepared figures; R.R.J., S.E.S., S.R.P., J.W.R., and H.P. drafted manuscript; R.R.J., S.E.S., S.R.P., J.W.R., and H.P. edited and revised manuscript; R.R.J., S.E.S., S.R.P., R.D.A., C.A.M., J.W.R., and H.P. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Nunes C, Pereira AM, Morais-Almeida M. Asthma costs and social impact. Asthma Res Pract 3: 1, 2017. doi: 10.1186/s40733-016-0029-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Woolcock AJ, Salome CM, Yan K. The shape of the dose-response curve to histamine in asthmatic and normal subjects. Am Rev Respir Dis 130: 71–75, 1984. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1984.130.1.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaplan A, FitzGerald JM, Buhl R, Vogelberg C, Hamelmann E. Comparing LAMA with LABA and LTRA as add-on therapies in primary care asthma management. NPJ Prim Care Respir Med 30: 50, 2020. doi: 10.1038/s41533-020-00205-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boulet LP, Turcotte H, Laviolette M, Naud F, Bernier MC, Martel S, Chakir J. Airway hyperresponsiveness, inflammation, and subepithelial collagen deposition in recently diagnosed versus long-standing mild asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 162: 1308–1313, 2000. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.162.4.9910051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Southam DS, Ellis R, Wattie J, Young S, Inman MD. Budesonide prevents but does not reverse sustained airway hyperresponsiveness in mice. Eur Respir J 32: 970–978, 2008. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00125307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stasiak SE, Jamieson RR, Bouffard J, Cram EJ, Parameswaran H. Intercellular communication controls agonist-induced calcium oscillations independently of gap junctions in smooth muscle cells. Sci Adv 6: eaba1149, 2020. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aba1149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.An SS, Mitzner W, Tang W-Y, Ahn K, Yoon A-R, Huang J, Kilic O, Yong HM, Fahey JW, Kumar S, Biswal S, Holgate ST, Panettieri RA Jr, Solway J, Liggett SB. An inflammation-independent contraction mechanophenotype of airway smooth muscle in asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol 138: 294–297.e4, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.12.1315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Polio SR, Stasiak SE, Jamieson RR, Balestrini JL, Krishnan R, Parameswaran H. Extracellular matrix stiffness regulates human airway smooth muscle contraction by altering the cell-cell coupling. Sci Rep 9: 9564, 2019. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-45716-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shkumatov A, Thompson M, Choi KM, Sicard D, Baek K, Kim DH, Tschumperlin DJ, Prakash YS, Kong H. Matrix stiffness-modulated proliferation and secretory function of the airway smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 308: L1125–L1135, 2015. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00154.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bourke JE, Li X, Foster SR, Wee E, Dagher H, Ziogas J, Harris T, Bonacci JV, Stewart AG. Collagen remodelling by airway smooth muscle is resistant to steroids and β2-agonists. Eur Respir J 37: 173–182, 2011. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00008109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Humphrey JD, Dufresne ER, Schwartz MA. Mechanotransduction and extracellular matrix homeostasis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 15: 802–812, 2014. doi: 10.1038/nrm3896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Uemura R, Miura J, Ishimoto T, Yagi K, Matsuda Y, Shimizu M, Nakano T, Hayashi M. UVA-activated riboflavin promotes collagen crosslinking to prevent root caries. Sci Rep 9: 1252, 2019. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-38137-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wollensak G, Spoerl E, Seiler T. Riboflavin/ultraviolet-A-induced collagen crosslinking for the treatment of keratoconus. Am J Ophthalmol 135: 620–627, 2003.doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(02)02220-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wollensak G, Spoerl E, Seiler T. Stress-strain measurements of human and porcine corneas after riboflavin-ultraviolet-A-induced cross-linking. J Cataract Refract Surg 29: 1780–1785, 2003. doi: 10.1016/s0886-3350(03)00407-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bossé Y, Chapman DG, Paré PD, King GG, Salome CM. A “Good” muscle in a “Bad” environment: the importance of airway smooth muscle force adaptation to airway hyperresponsiveness. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 179: 269–275, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2011.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harvey BC, Parameswaran H, Lutchen KR. Can breathing-like pressure oscillations reverse or prevent narrowing of small intact airways? J Appl Physiol 119: 47–54, 2015. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01100.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heo J, Koh RH, Shim W, Kim HD, Yim H-G, Hwang NS. Riboflavin-induced photo-crosslinking of collagen hydrogel and its application in meniscus tissue engineering. Drug Deliv Transl Res 6: 148–158, 2016. doi: 10.1007/s13346-015-0224-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Burgess JK, Mauad T, Tjin G, Karlsson JC, Westergren-Thorsson G. The extracellular matrix—the under-recognized element in lung disease? J Pathol 240: 397–409, 2016. doi: 10.1002/path.4808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.An SS, Laudadio RE, Lai J, Rogers RA, Fredberg JJ. Stiffness changes in cultured airway smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 283: C792–C801, 2002. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00425.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baker DG, Don HF, Brown JK. Direct measurement of acetylcholine release in guinea pig trachea. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 263: L142–L147, 1992. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1992.263.1.l142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang Z, Robinson NE, Yu M. ACh release from horse airway cholinergic nerves: effects of stimulation intensity and muscle preload. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 264: L269–L275, 1993. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1993.264.3.l269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bai Y, Sanderson MJ. The contribution of Ca2+ signaling and Ca2+ sensitivity to the regulation of airway smooth muscle contraction is different in rats and mice. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 296: L947–L958, 2009. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.90288.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tan X, Sanderson MJ. Bitter tasting compounds dilate airways by inhibiting airway smooth muscle calcium oscillations and calcium sensitivity. Br J Pharmacol 171: 646–662, 2014. doi: 10.1111/bph.12460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mostaço-Guidolin LB, Osei ET, Ullah J, Hajimohammadi S, Fouadi M, Li X, Li V, Shaheen F, Yang CX, Chu F, Cole DJ, Brandsma CA, Heijink IH, Maksym GN, Walker D, Hackett T-L. Defective fibrillar collagen organization by fibroblasts contributes to airway remodeling in asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 200: 431–443, 2019. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201810-1855OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang N, Tolić-Nørrelykke IM, Chen J, Mijailovich SM, Butler JP, Fredberg JJ, Stamenović D. Cell prestress. I. Stiffness and prestress are closely associated in adherent contractile cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 282: C606–C616, 2002. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00269.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Krishnan R, Park CY, Lin Y-C, Mead J, Jaspers RT, Trepat X, Lenormand G, Tambe D, Smolensky AV, Knoll AH, Butler JP, Fredberg JJ. Reinforcement versus fluidization in cytoskeletal mechanoresponsiveness. PLoS One 4: e5486, 2009. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Parameswaran H, Lutchen KR, Suki B. A computational model of the response of adherent cells to stretch and changes in substrate stiffness. J Appl Physiol (1985) 116: 825–834, 2014. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00962.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.James AL, Elliot JG, Jones RL, Carroll ML, Mauad T, Bai TR, Abramson MJ, McKay KO, Green FH. Airway smooth muscle hypertrophy and hyperplasia in asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 185: 1058–1064, 2012. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201110-1849OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lowe CJ, Reucroft IM, Grota MC, Shreiber DI. Production of highly aligned collagen scaffolds by freeze-drying of self-assembled, fibrillar collagen gels. ACS Biomater Sci Eng 2: 643–651, 2016. doi: 10.1021/acsbiomaterials.6b00036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lynch HA, Johannessen W, Wu JP, Jawa A, Elliott DM. Effect of fiber orientation and strain rate on the nonlinear uniaxial tensile material properties of tendon. J Biomech Eng 125: 726–731, 2003. doi: 10.1115/1.1614819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cooper JA. Effects of cytochalasin and phalloidin on actin. J Cell Biol 105: 1473–1478, 1987. doi: 10.1083/jcb.105.4.1473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Watanabe N, Mitchison TJ. Single-molecule speckle analysis of actin filament turnover in lamellipodia. Science 295: 1083–1086, 2002. doi: 10.1126/science.1067470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.González-Avila G, Bazan-Perkins B, Sandoval C, Sommer B, Vadillo-Gonzalez S, Ramos C, Aquino-Galvez A. Interstitial collagen turnover during airway remodeling in acute and chronic experimental asthma. Exp Ther Med 12: 1419–1427, 2016. doi: 10.3892/etm.2016.3509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reinhardt AK, Bottoms SE, Laurent GJ, McAnulty RJ. Quantification of collagen and proteoglycan deposition in an murine model of airway remodelling. Respir Res 6: 30, 2005. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-6-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bhole AP, Flynn BP, Liles M, Saeidi N, Dimarzio CA, Ruberti JW. Mechanical strain enhances survivability of collagen micronetworks in the presence of collagenase: implications for load-bearing matrix growth and stability. Philos Trans A Math Phys Eng Sci 367: 3339–3362, 2009. doi: 10.1098/rsta.2009.0093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Camp RJ, Liles M, Beale J, Saeidi N, Flynn BP, Moore E, Murthy SK, Ruberti JW. Molecular mechanochemistry: low force switch slows enzymatic cleavage of human type I collagen monomer. J Am Chem Soc 133: 4073–4078, 2011. doi: 10.1021/ja110098b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Flynn BP, Bhole AP, Saeidi N, Liles M, DiMarzio CA, Ruberti JW. Mechanical strain stabilizes reconstituted collagen fibrils against enzymatic degradation by mammalian collagenase matrix metalloproteinase 8 (MMP-8). PLoS One 5: e12337, 2010. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Licup AJ, Münster S, Sharma A, Sheinman M, Jawerth LM, Fabry B, Weitz DA, MacKintosh FC. Stress controls the mechanics of collagen networks. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 112: 9573–9578, 2015. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1504258112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]