Abstract

Donepezil is a centrally acting acetylcholinesterase (AChE) inhibitor with therapeutic potential in inflammatory diseases; however, the underlying autonomic and cholinergic mechanisms remain unclear. Here, we assessed effects of donepezil on mean arterial pressure (MAP), heart rate (HR), HR variability, and body temperature in conscious adult male C57BL/6 mice to investigate the autonomic pathways involved. Central versus peripheral cholinergic effects of donepezil were assessed using pharmacological approaches including comparison with the peripherally acting AChE inhibitor, neostigmine. Drug treatments included donepezil (2.5 or 5 mg/kg sc), neostigmine methyl sulfate (80 or 240 μg/kg ip), atropine sulfate (5 mg/kg ip), atropine methyl bromide (5 mg/kg ip), or saline. Donepezil, at 2.5 and 5 mg/kg, decreased HR by 36 ± 4% and 44 ± 3% compared with saline (n = 10, P < 0.001). Donepezil, at 2.5 and 5 mg/kg, decreased temperature by 13 ± 2% and 22 ± 2% compared with saline (n = 6, P < 0.001). Modest (P < 0.001) increases in MAP were observed with donepezil after peak bradycardia occurred. Atropine sulfate and atropine methyl bromide blocked bradycardic responses to donepezil, but only atropine sulfate attenuated hypothermia. The pressor response to donepezil was similar in mice coadministered atropine sulfate; however, coadministration of atropine methyl bromide potentiated the increase in MAP. Neostigmine did not alter HR or temperature, but did result in early increases in MAP. Despite the marked bradycardia, donepezil did not increase normalized high-frequency HR variability. We conclude that donepezil causes marked bradycardia and hypothermia in conscious mice via the activation of muscarinic receptors while concurrently increasing MAP via autonomic and cholinergic pathways that remain to be elucidated.

Keywords: acetylcholinesterase, cardiovascular, donepezil, muscarinic, temperature

INTRODUCTION

Donepezil is one of three centrally active cholinesterase inhibitors used in the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) (1, 2). All of these agents have comparable efficacy by virtue of their ability to inhibit acetylcholinesterase (AChE), delay the physiological inactivation of acetylcholine (ACh), and thereby enhance cholinergic neurotransmission at critical synapses in the brain (1). From the clinical perspective, donepezil and other centrally active AChE inhibitors are a major advance in the treatment of AD, providing acute and long-term benefits with a tolerable safety profile (1). Accordingly, the therapeutic application of these Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved drugs is currently being explored in other diseases and disease models where controlled, long-term potentiation of cholinergic neurotransmission could be beneficial.

It is well known that inflammation plays a crucial role in many diseases, and pioneering work conducted over the past two decades has identified a novel cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway (3, 4). This pathway involves a vagal nerve efferent activity-induced increase in sympathetic nerve activity to the spleen ultimately leading to a decrease in circulating proinflammatory cytokines. As expected, vagal nerve stimulation reduces proinflammatory cytokines in experimental models associated with inflammation (5). Studies have also shown that the cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway can be activated by centrally acting AChE inhibitors and by stimulation of M1 muscarinic receptors in the brain (6). The therapeutic potential of these drugs in treating inflammatory disorders was demonstrated by recent work showing that galantamine, a centrally acting AChE inhibitor, reduces insulin resistance in patients with metabolic syndrome (7).

Central activation of classical sympathetic efferent pathways, independent of vagal nerve efferent activity, also plays a major role in modulating inflammatory responses to various stimuli (8, 9). Indeed, it has also been acknowledged that such sympathetic pathways may contribute to the anti-inflammatory effects of centrally acting AChE inhibitors (6, 10). This is consistent with previous studies showing that acute administration of centrally acting AChE inhibitors increase sympathetic activity and blood pressure (BP) in various species (11). However, there is a scarcity of data describing the physiological responses to centrally acting AChE inhibitors in conscious mice, which are commonly used to evaluate the mechanisms mediating the cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway.

The primary goal of this study was to determine the cardiovascular and thermoregulatory effects of donepezil in conscious, freely moving mice. Cardiovascular and temperature responses were used to assess the autonomic effects of donepezil, a method that has been previously utilized to assess the effects of various pharmacological agents on autonomic function in rodents (12–16). In addition to arterial blood pressure (BP), heart rate (HR), and core body temperature, HR variability was assessed to evaluate cardiac sympathovagal balance (14, 15, 17–20). Central versus peripheral effects of donepezil were determined using a pharmacological approach and by comparison with the peripherally acting AChE inhibitor, neostigmine.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Adult (5-mo-old) male C57BL/6J mice (Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) were used for this study. Mice were given γ-irradiated food and water ad libitum and housed singly in ventilated cages on a 12-h light/dark cycle at 21 ± 0.2°C and 50 ± 10% relative humidity. All experiments were approved by the East Tennessee State University Committee on Animal Care and followed protocols established by the National Institutes of Health in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (8th Ed., National Academy of Sciences, 2011).

Drugs and Treatments

Donepezil hydrochloride (donepezil), atropine sulfate, atropine methyl bromide, and neostigmine methyl sulfate (neostigmine) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). All drugs were dissolved in sterile saline (0.9% NaCl) before administration. Drug doses were selected to be in the effective range based on previous in vivo studies in mice (21–33). These studies also confirmed that the actions of atropine methyl bromide and neostigmine are limited to the periphery. Donepezil and neostigmine were evaluated at two doses each. Neither dose of AChE inhibitors produced signs of toxicity, such as salivation and diarrhea; however, a similar degree of muscle fasciculation was observed after administration of both drugs.

Experimental Protocols

Experiment 1: Assessment of donepezil versus neostigmine for effects on rectal temperature, HR, and ECG parameters in conscious mice.

Mice were administered donepezil (2.5 or 5 mg/kg), neostigmine (80 μg/kg), or sterile saline (0.9% NaCl) via subcutaneous (sc) injection with a sterile 26-gauge needle. All injections were given to conscious, restrained mice between 10 and 11 AM, and drug treatments were randomized and separated by 2 days. Rectal temperature was measured using a MicroTherma 2 T handheld thermometer and a 0.75-in. rectal probe (Braintree Scientific, Braintree, MA) before injection (baseline) and every hour for 5 h following ECG measurements. ECGs were recorded noninvasively using the ECGenie apparatus (Mouse Specifics, Inc., Boston, MA), as described previously (34). For ECG measurements, mice were individually removed from their cage and placed on the elevated ECGenie platform containing disposable footpad electrodes several minutes before data collection to allow time for acclimation. ECG signals were collected for 5 min before drug administration (baseline) and for 5 min every hour for 5 h thereafter. Rectal temperature was assessed immediately after ECG measurements. The administration of drugs was staggered so that ECG and rectal temperature could be assessed in multiple mice on a given day. At least 100 raw ECG signals were analyzed per mouse for each time point using e-Mouse software (Mouse Specifics, Inc.). Cardiac intervals (i.e., PR, QRT, and QTc) and HR were analyzed for each time point and treatment group.

Experiment 2: Effects of donepezil with and without atropine sulfate or atropine methyl bromide and neostigmine on BP, HR, and core body temperature in conscious, chronically instrumented mice.

One group of mice were surgically instrumented with a BP radiotransmitter (model TA11PA-C10, Data Sciences International, St. Paul, MN) under isoflurane anesthesia. A 1.5-cm incision was made between the scapulae, and the body of the transmitter was positioned subcutaneouly. A 1-cm vertical incision was then made along the neck and the catheter tip of the transmitter was routed to the neck incision site from the scapulae region. The right carotid artery was isolated using blunt dissection, and the BP catheter was inserted into the artery and advanced to the aortic arch. Both skin incisions were then closed. Mice were administered Tylenol (1 g/L) in the drinking water for 3 days following surgery and were allowed to recover from surgery for 2 wk before experiments were performed. An additional group of mice were surgically instrumented with a temperature radiotransmitter (TA-F10, Data Sciences International, St. Paul, MN) under isoflurane anesthesia. Briefly, a 1.5-cm vertical incision was made along the abdominal wall, and the transmitter was placed within the abdominal cavity and the incision was closed. Mice were administered Tylenol (1 g/L) in the drinking water for 3 days following surgery and were allowed to recover from surgery for 2 wk before experiments were performed. During experiments, BP (500 Hz), HR (500 Hz), and core body temperature (10 Hz) were continuously recorded for 1 h before (baseline) and for 5 h following drug administration. Hourly averages of mean arterial pressure (MAP), HR, and core body temperature were made over the baseline period and every hour following drug administration.

Over a 3-wk period, mice in both groups were administered nine drug regimens consisting of 1) sterile saline (0.9% NaCl sc), 2) donepezil (2.5 mg/kg sc), 3) donepezil (5 mg/kg sc), 4) neostigmine (80 μg/kg ip), 5) neostigmine (240 μg/kg ip), 6) atropine sulfate (5 mg/kg ip), 7) atropine methyl bromide (5 mg/kg ip), 8) donepezil (5 mg/kg sc) + atropine sulfate (5 mg/kg ip), or 9) donepezil (5 mg/kg sc) + atropine methyl bromide (5 mg/kg ip). In these experiments, neostigmine was administered intraperitoneally to enhance absorption. The rationale for coadministering atropine sulfate, a central + peripheral muscarinic receptor antagonist, or atropine methyl bromide, a peripheral muscarinic receptor antagonist, with donepezil was to determine the central versus peripheral mechanisms by which it alters cardiovascular function and body temperature. All drugs were administered at 10 AM, and drug treatments were randomized and separated by 2 days. Just before the drug administration, mice were briefly and lightly anesthetized with isoflurane to avoid handling-induced displacement of the BP transmitter and catheter. Mice instrumented with temperature radiotransmitters were treated in a similar fashion before the drug administration. Mice were returned to their cages immediately following drug administration. We did not include the first 10 min of data following drug administration to avoid collecting data when mice were still anesthetized and to allow for mice to completely regain consciousness and mobility before data collection began. Diminished BP and pulse pressure from the radiotransmitter occurred in a few mice over the 3-wk period; therefore, some mice did not receive all drug regimens.

Experiment 3: Effects of anesthesia on HR responses to donepezil and saline.

In one group of mice, donepezil (5 mg/kg) and saline were administered on separate days in a similar fashion to that described in experiment 2. At 10 min following drug administration, mice were anesthetized with isoflurane (5% induction/1.0% maintenance), placed on a heated table (37°C) , and ECG electrodes were placed subcutaneously for the assessment of HR. The ECG was recorded using a Grass P55 A.C. preamplifier (Grass Technologies, West Warwick, RI), a PowerLab/8SP (ADInstruments, Colorado Springs, CO), and a computer running LabChart 7 Pro software version 7.3.8 (ADInstruments). After a 5-min stabilization period, HR was recorded for 15 min in anesthetized mice. In the final experiment, the muscarinic receptor agonist, carbachol (1 mg/kg ip), was administered at the end of the 15-min protocol to assess the functionality of cardiac muscarinic receptors under anesthesia. Mice were euthanized after recording HR responses to carbachol.

In another group of mice, donepezil (5 mg/kg sc) and saline were administered on separate days after mice were anesthetized. For this experiment, mice were anesthetized with isoflurane (5% induction/1.0% maintenance), placed on a heated table (37°C), and ECG electrodes were placed subcutaneously for the assessment of HR. After a 5-min stabilization period, HR was recorded for 5 min before donepezil (5 mg/kg sc) or saline administration and for 20 min thereafter. In the final experiment, carbachol (1 mg/kg ip) was administered at the end of the protocol to assess the functionality of cardiac muscarinic receptors in anesthetized mice. Mice were euthanized after recording HR responses to carbachol.

Pulse Interval Variability Analyses

Pulse interval (PI) duration was derived from the 500-Hz arterial pressure recordings using a custom-designed program (MATLAB) in which each peak of the systolic pressure waveform was identified, resulting in a sequence of PIs between the successive peaks. Every recording was visually inspected to ensure that the data used for PI variability analyses were free of artifacts and arrhythmias and to ensure the accuracy of the systolic peak identifications. For the time-domain analyses of PI variability, the average PI, standard deviation (SD) of PI, and coefficient of variation (CV) of PI were calculated from the PI sequence for the 1-h baseline period and for the first hour following drug administration. For the frequency-domain analysis of PI variability, a 500 Hz sampled PI signal was created by assigning each sample a value equal to the PI for the pair of successive peaks between which that sample lies. The 500-Hz PI data were resampled to 20 Hz after being low-pass filtered to remove signal components with frequencies greater than 10 Hz. The recording was then divided into ∼16 times segments of 8,192 samples with 50% overlap of segments. The PI spectra were determined using Welch’s averaged periodogram method with a fast Fourier transform applied to each segment after multiplication by a Hanning window. The PI power spectral density was integrated over three frequency ranges consisting of very low frequency (VLF, 0.01–0.15 Hz), low frequency (LF, 0.15–1.5 Hz), and high frequency (HF, 1.5–5 Hz). These frequency ranges were based on previously published data in mice (15, 20) and were used to assess the modulation of cardiac rhythms by the autonomic nervous system. Total PI power was defined as the sum of VLF, LF, and HF powers. We assessed PI variability during the first hour following drug administration because it was associated with the peak drug effect on cardiovascular parameters, and the majority of previous studies in mice have used similar time frames to evaluate PI variability following the administration of drugs that alter cholinergic activity (14, 15, 19, 35).

Statistical Analysis

Group data are expressed as the means ± SE. A two-way repeated-measures ANOVA was used to evaluate group differences in temperature, ECG parameters, HR, and MAP over time. A two-way repeated-measures ANOVA was also used to evaluate effects of drugs versus baseline levels and versus saline administration on PI variability parameters. Post hoc comparisons were made using a Holm–Sidak test. A probability level of 0.05 or less was regarded as statistically significant.

RESULTS

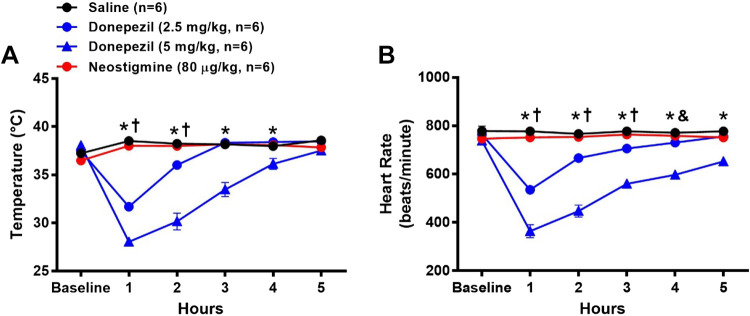

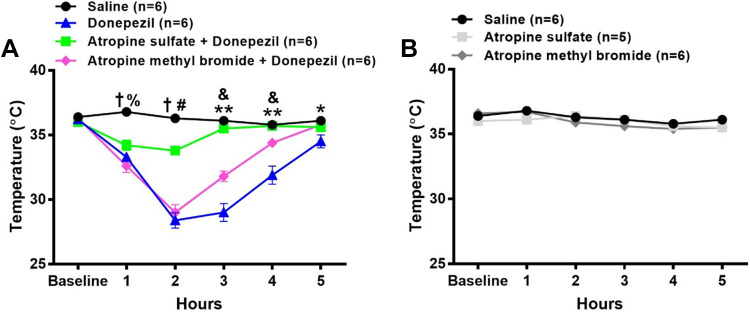

Effects of Donepezil and Neostigmine on Rectal Temperature

As shown in Fig. 1A, a significant dose-dependent hypothermic response to donepezil was observed 1 h after administration [16% decrease from baseline for 2.5 mg/kg (n = 6) and 26% decrease from baseline for 5 mg/kg donepezil (n = 6)] as compared with saline. Rectal temperature recovered by 3 and 5 h in mice treated with 2.5 and 5 mg/kg donepezil, respectively. Neither saline nor neostigmine (80 μg/kg, n = 6) altered rectal temperature.

Figure 1.

Effects of donepezil and neostigmine on rectal temperature and heart rate (HR) in conscious mice. Data were collected before (baseline) and for 5 h after administration of saline (sc), donepezil (2.5 mg/kg sc), donepezil (5 mg/kg sc), or neostigmine (80 µg/kg sc). Drugs were administered to the same group of mice on four separate days. Data are means ± SE; n, number of animals. Two-way repeated-measures ANOVA with Holm–Sidak post hoc comparison was used to assess differences in rectal temperature (A) and heart rate (B) among groups. *P < 0.05, 5 mg/kg donepezil vs. all other treatments; †P < 0.05, 2.5 mg/kg donepezil vs. 80 μg/kg neostigmine and saline; &P < 0.05, 2.5 mg/kg donepezil vs. saline.

Effects of Donepezil and Neostigmine on HR from ECG Recordings

As shown in Fig. 1B, a significant dose-dependent reduction in HR was observed 1 h after administration of donepezil [30% decrease from baseline for 2.5 mg/kg (n = 6) and 51% decrease from baseline for 5 mg/kg donepezil (n = 6)] as compared with saline. HR recovered by 5 h in mice treated with 2.5 mg/kg donepezil but remained significantly lower in mice treated with 5 mg/kg donepezil as compared with all other groups over the entire experimental period. Neither saline nor neostigmine (80 μg/kg, n = 6) altered HR.

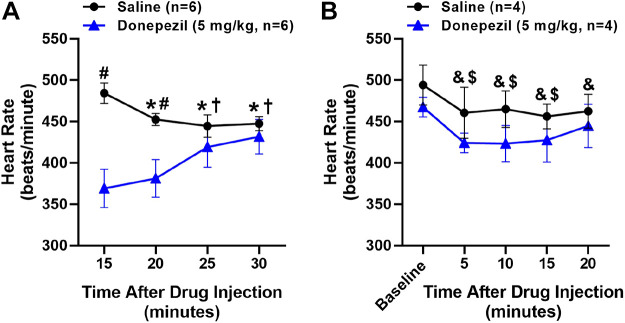

Effects of Donepezil and Neostigmine on Cardiac Intervals (i.e., PR, QRS, and QTc)

ECG analysis showed that PR, QRS, and QTc intervals were significantly prolonged 1 h after administration of 5 mg/kg donepezil (n = 6) and variably affected 1 h after administration of 2.5 mg/kg donepezil (n = 6) relative to saline administration (n = 6) (Fig. 2). As shown in Fig. 2A, the PR interval of mice receiving 5 mg/kg donepezil was significantly prolonged (81% increase from baseline) at 1 h and gradually recovered over the next 4 h, whereas the PR interval of mice receiving 2.5 mg/kg donepezil (13% increase from baseline) did not differ significantly from saline. The PR intervals of 2.5 mg/kg donepezil-, neostigmine-, and saline-treated groups did not differ significantly from baseline over the duration of the experiment.

Figure 2.

Effects of donepezil and neostigmine on cardiac intervals in conscious mice. Data were collected before (baseline) and for 5 h following the administration of saline (sc), donepezil (2.5 mg/kg sc), donepezil (5 mg/kg sc), or neostigmine (80 µg/kg sc). Drugs were administered to the same group of mice on four separate days. Data are means ± SE; n, number of animals. Two-way repeated-measures ANOVA with Holm–Sidak post hoc comparison was used to assess differences in PR interval (A), QRS interval (B), and QTc interval (C) among groups. *P < 0.05, 5 mg/kg donepezil vs. all other treatments; †P < 0.05, 2.5 mg/kg donepezil vs. 80 μg/kg neostigmine and saline; #P < 0.05, 5 mg/kg donepezil vs. saline; $P < 0.05, 5 mg/kg donepezil vs. 2.5 mg/kg donepezil and saline.

As shown in Fig. 2B, the QRS intervals of mice receiving either dose of donepezil were significantly prolonged 1 h after administration (37% increase from baseline for 2.5 mg/kg and 67% increase from baseline for 5 mg/kg donepezil) relative to saline. The prolonged QRS interval gradually returned to baseline over the next 2 h in mice treated with 2.5 mg/kg donepezil and by 4 h in mice treated with 5 mg/kg donepezil. QRS intervals of saline- and neostigmine-treated mice did not differ significantly from baseline over the duration of the experiment.

As shown in Fig. 2C, the QTc intervals of mice receiving either dose of donepezil were significantly prolonged at 1 h after administration (25% increase from baseline for 2.5 mg/kg and 42% increase from baseline for 5 mg/kg donepezil) relative to saline. QTc intervals gradually returned to baseline by 3 h in mice administered 2.5 mg/kg donepezil and by 5 h with 5 mg/kg donepezil. QTc intervals of saline- and neostigmine-treated mice did not differ significantly from baseline over the duration of the experiment.

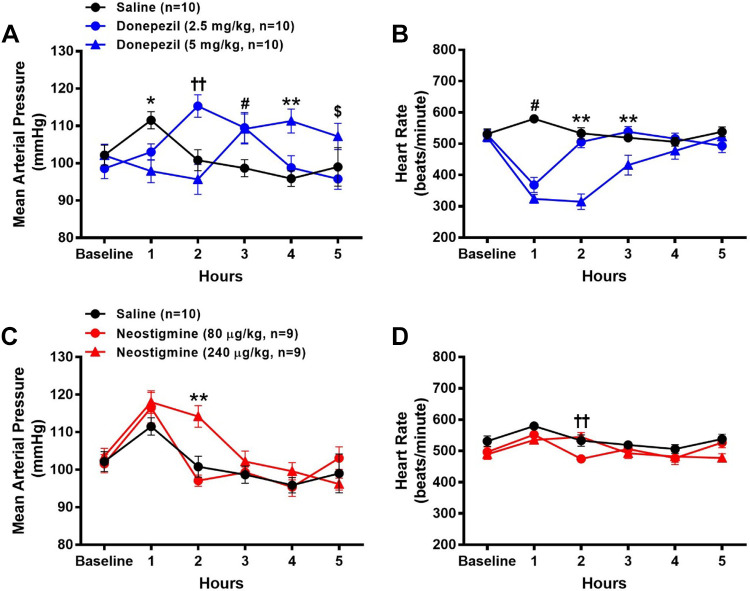

Effects of Donepezil Versus Neostigmine on Radiotelemetrically Measured MAP, HR, and Core Body Temperature in Conscious Mice

No significant differences in baseline HR, MAP, or core body temperature were observed across all groups. As shown in Fig. 3, A and C, time-dependent changes in MAP were observed in all groups. During the first hour following administration, there was a modest (P < 0.05) increase in MAP with saline (9%, n = 10) and 80 μg/kg (15%, n = 9) and 240 μg/kg (14%, n = 9) neostigmine, but not donepezil, as compared with baseline levels. The increase in MAP in these groups was likely due to the effects of recovery from anesthesia given that mice administered saline also exhibited a modest increase in MAP. Although MAP returned to baseline levels for the remainder of the experiment by 2 h following saline and 80 μg/kg neostigmine, it remained significantly elevated with 240 μg/kg neostigmine (10% increase from baseline) as compared with saline. By 3 h postadministration of 240 μg/kg neostigmine, MAP returned to baseline levels and remained unchanged for the remainder of the experiment. Significant increases in MAP were observed at 2 and 3 h following the administration of 2.5 mg/kg donepezil (17% and 11% increase from baseline, respectively, n = 10) and at 3 and 4 h following the administration of 5 mg/kg donepezil (7% and 9%, increase from baseline, respectively, n = 10), as compared with saline.

Figure 3.

Effects of donepezil and neostigmine on radiotelemetrically measured mean arterial pressure (MAP) and heart rate (HR) in conscious mice. Data were collected before (baseline) and for 5 h following the administration of saline (sc), donepezil (2.5 mg/kg sc), donepezil (5 mg/kg sc), neostigmine (80 µg/kg ip), or neostigmine (240 µg/kg ip). Drugs were administered to the same group of mice on five separate days. The MAP and HR data following saline administration are shown in both A and C and B and D, respectively. Data are means ± SE; n, number of animals. Two-way repeated-measures ANOVA with Holm–Sidak post hoc comparison was used to assess differences in MAP and HR among groups. *P < 0.05, 5 mg/kg donepezil vs. saline; ††P < 0.05, 2.5 mg/kg donepezil vs. all other treatments and P < 0.05, 80 µg/kg neostigmine vs. all other treatments; #P < 0.05, 2.5 and 5 mg/kg donepezil vs. saline; **P < 0.05, 5 mg/kg donepezil vs. all other treatments and P < 0.05, 240 µg/kg neostigmine vs. all other treatments; $P < 0.05, 5 mg/kg donepezil vs. 2.5 mg/kg donepezil.

Similar to the results observed in the ECG study, donepezil led to marked reductions in HR (30% and 38% reduction at 1-h postinjection in mice administered the 2.5 and 5 mg/kg doses, respectively) as illustrated in Fig. 3B. In mice administered 2.5 mg/kg donepezil, HR returned to baseline levels at 2-h postinjection. In contrast, 5 mg/kg donepezil led to sustained reductions in HR for 3-h postinjection. Neither saline nor neostigmine altered HR during the experiment as compared with baseline levels. At 2-h postadministration, HR was modestly, but significantly, lower following 80 μg/kg neostigmine versus saline administration (Fig. 3D).

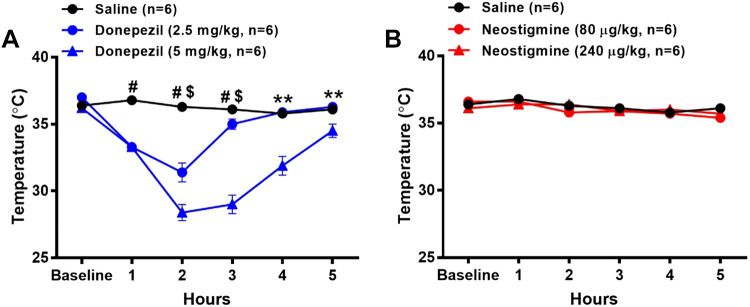

Similar to the rectal temperature measurements, donepezil led to substantial reductions in core body temperature (Fig. 4A). Significant decreases in core body temperature were detected at 1 h and peaked at 2 h after 2.5 mg/kg (15% reduction from baseline, n = 6) and 5 mg/kg (22% reduction from baseline, n = 6) donepezil administration as compared with saline. Core body temperature returned to baseline levels by 3 and 5 h after administration of 2.5 mg/kg and 5 mg/kg donepezil, respectively. Core body temperature was not significantly altered following administration of either 80 μg/kg (n = 6) or 240 μg/kg neostigmine (n = 6) and saline (n = 6).

Figure 4.

Effects of donepezil and neostigmine on radiotelemetrically measured core body temperature in conscious mice. Data were collected before (baseline) and for 5 h following the administration of saline (sc), donepezil (2.5 mg/kg sc), donepezil (5 mg/kg sc), neostigmine (80 µg/kg ip), or neostigmine (240 µg/kg ip). Drugs were administered to the same group of mice on five separate days. The temperature data following saline administration are shown in both A and B. Data are means ± SE; n, number of animals. Two-way repeated-measures ANOVA with Holm–Sidak post hoc comparison was used to assess differences in core body temperature among groups. #P < 0.05, 2.5 and 5 mg/kg donepezil versus saline; $P < 0.05, 5 mg/kg donepezil versus 2.5 mg/kg donepezil; **P < 0.05 5 mg/kg donepezil versus all other treatments.

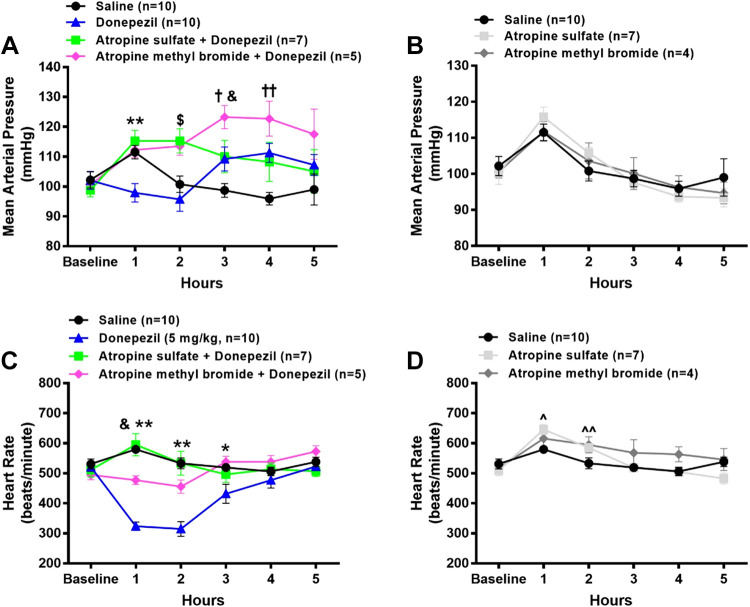

Effects of Atropine Sulfate Versus Atropine Methyl Bromide on Donepezil-Induced Changes in Radiotelemetrically Measured MAP, HR, and Core Body Temperature in Conscious Mice

To determine the role of central versus peripheral cholinergic pathways by which donepezil alters MAP, HR, and core body temperature, mice were administered donepezil (5 mg/kg sc) in conjunction with either the central + peripheral muscarinic receptor antagonist, atropine sulfate (5 mg/kg ip, n = 7), or the peripheral muscarinic receptor antagonist, atropine methyl bromide (5 mg/kg ip, n = 5). No significant differences in baseline MAP, HR, or core body temperature were observed among all groups. As shown in Fig. 5A, MAP was significantly higher over the first 2 h in mice coadministered either atropine sulfate (17% and 18% increase from baseline, respectively) or atropine methyl bromide (8% and 14% increase from baseline, respectively) with donepezil as compared with donepezil alone. At 3 and 4 h after drug administration, MAP was significantly and similarly elevated in mice administered donepezil alone and atropine sulfate + donepezil as compared with saline. The coadministration of atropine methyl bromide with donepezil significantly enhanced the pressor response at 3 h (19% increase from baseline), which tended to remain higher at 4 h (15% increase from baseline), as compared with donepezil alone. Neither atropine sulfate (n = 7) nor atropine methyl bromide (n = 4) altered MAP when administered alone (Fig. 5B).

Figure 5.

Effects of central + peripheral versus peripheral muscarinic receptor blockade on donepezil-induced changes in radiotelemetrically measured mean arterial pressure (MAP) and heart rate (HR) in conscious mice. A subgroup of mice described in Fig. 3 were administered atropine sulfate (5 mg/kg ip, central + peripheral muscarinic receptor antagonist) or atropine methyl bromide (5 mg/kg ip, peripheral muscarinic receptor antagonist) either A and C in combination with 5 mg/kg donepezil or B and D alone. The MAP and HR data after administration of saline and 5 mg/kg donepezil are the same as that shown in Fig. 3. Data are means ± SE; n, number of animals. Two-way repeated-measures ANOVA with Holm–Sidak post hoc comparison was used to assess differences in MAP (A and B) and HR (C and D) among groups. **P < 0.05, 5 mg/kg donepezil versus all other treatments; $P < 0.05, 5 mg/kg donepezil and saline versus all other treatments; †P < 0.05, saline versus all other treatments; &P < 0.05, 5 mg/kg donepezil + atropine methyl bromide versus all other treatments; ††P < 0.05, saline vs. 5 mg/kg donepezil and 5 mg/kg donepezil + atropine methyl bromide; *P < 0.05 5 mg/kg donepezil vs. saline and donepezil + atropine methyl bromide; ^P < 0.05, atropine sulfate vs. saline; ^^P < 0.05, atropine sulfate and atropine methyl bromide vs. saline.

As shown in Fig. 5C, the coadministration of atropine sulfate with donepezil completely abolished the donepezil-induced decrease in HR. Atropine methyl bromide also largely mitigated the donepezil-induced decrease in HR. When administered alone (Fig. 5D), atropine sulfate led to a modest but significant increase in HR during the first and second hour after injection as compared with saline. The administration of atropine methyl bromide significantly increased HR only during the second hour after injection as compared with saline administration.

As shown in Fig. 6A, the coadministration of atropine sulfate with donepezil (n = 6) largely prevented the decrease in core body temperature. In contrast, coadministration of atropine methyl bromide with donepezil (n = 6) did not affect the peak decrease in core body temperature. Individually, neither atropine sulfate (n = 5) nor atropine methyl bromide (n = 6) altered core body temperature (Fig. 6B).

Figure 6.

Effects of central + peripheral versus peripheral muscarinic receptor blockade on donepezil-induced changes in radiotelemetrically measured core body temperature in conscious mice. A subgroup of mice described in Fig. 4 were administered atropine sulfate (central + peripheral muscarinic receptor antagonist) or atropine methyl bromide (peripheral muscarinic receptor antagonist) either in combination with 5 mg/kg donepezil (A) or alone (B). The temperature data following administration of saline and 5 mg/kg donepezil are the same as that shown in Fig. 4. Data are means ± SE; n, number of animals. Two-way repeated-measures ANOVA with Holm–Sidak post hoc comparison was used to assess differences in core body temperature among groups. †P < 0.05, saline vs. all other treatments; %P < 0.05, 5 mg/kg donepezil + atropine methyl bromide vs. 5 mg/kg donepezil + atropine sulfate; #P < 0.05, 5 mg/kg donepezil + atropine sulfate vs. all other treatments; &P < 0.05, 5 mg/kg donepezil + atropine methyl bromide vs. all other treatments; **P < 0.05, 5 mg/kg donepezil vs. all other treatments; *P < 0.05, 5 mg/kg donepezil vs. saline and 5 mg/kg donepezil + atropine methyl bromide.

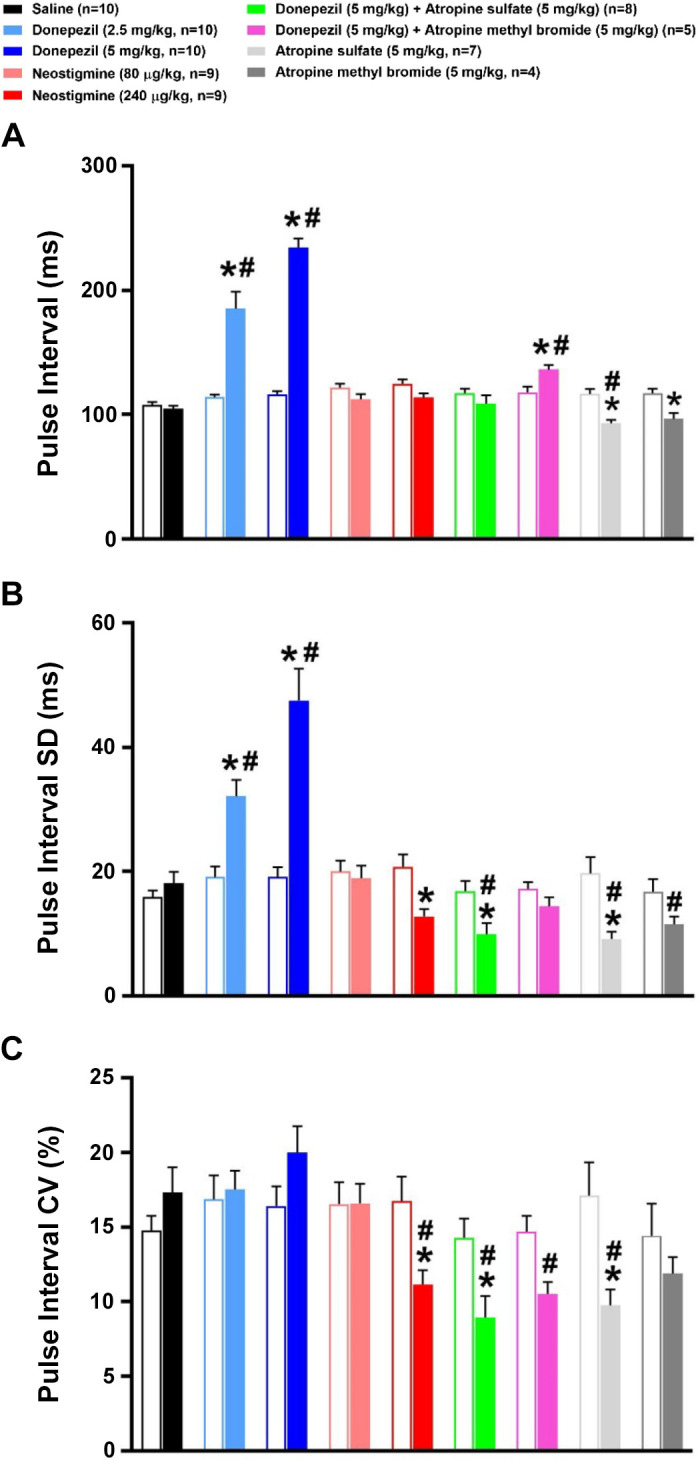

Effects of Donepezil, Neostigmine, and Muscarinic Receptor Blockade on Time-Domain Analysis of PI Variability

A significant increase in PI was observed following the administration of 2.5 and 5 mg/kg donepezil as compared with baseline levels (Fig. 7A). Neither dose of neostigmine significantly altered PI. Individually, atropine sulfate and atropine methyl bromide significantly reduced PI as compared with baseline. A significant increase in PI was observed following donepezil + atropine methyl bromide as compared with baseline. As shown in Fig. 7B, donepezil significantly increased PI SD, whereas 240 μg/kg neostigmine and most treatments involving the administration of atropine reduced PI SD. As shown in Fig. 7C, 5 mg/kg donepezil tended to increase PI CV, but did not reach statistical significance. In contrast, 240 μg/kg neostigmine and most treatments involving the administration of atropine reduced PI CV as compared with their respective baseline values.

Figure 7.

Effects of cholinergic drugs on time-domain analyses of pulse interval (PI) variability. Time-domain analysis of PI (A) and PI variability [PI standard deviation (SD) (B) and PI coefficient of variation (CV) (C)] before (baseline) and during the first hour following administration of saline, donepezil (2.5 mg/kg sc), donepezil (5 mg/kg sc), neostigmine (80 µg/kg ip), neostigmine (240 µg/kg ip), 5 mg/kg donepezil + atropine sulfate (5 mg/kg ip), 5 mg/kg donepezil + atropine methyl bromide (5 mg/kg ip), atropine sulfate, or atropine methyl bromide. Open and filled bars represent pre- and postdrug values following each treatment. Data are means ± SE; n, number of animals. Two-way repeated-measures ANOVA with Holm–Sidak post hoc comparison was used to assess the effects of treatments versus respective baseline values versus saline. *P < 0.05, drug versus respective baseline value; #P < 0.05, drug versus saline.

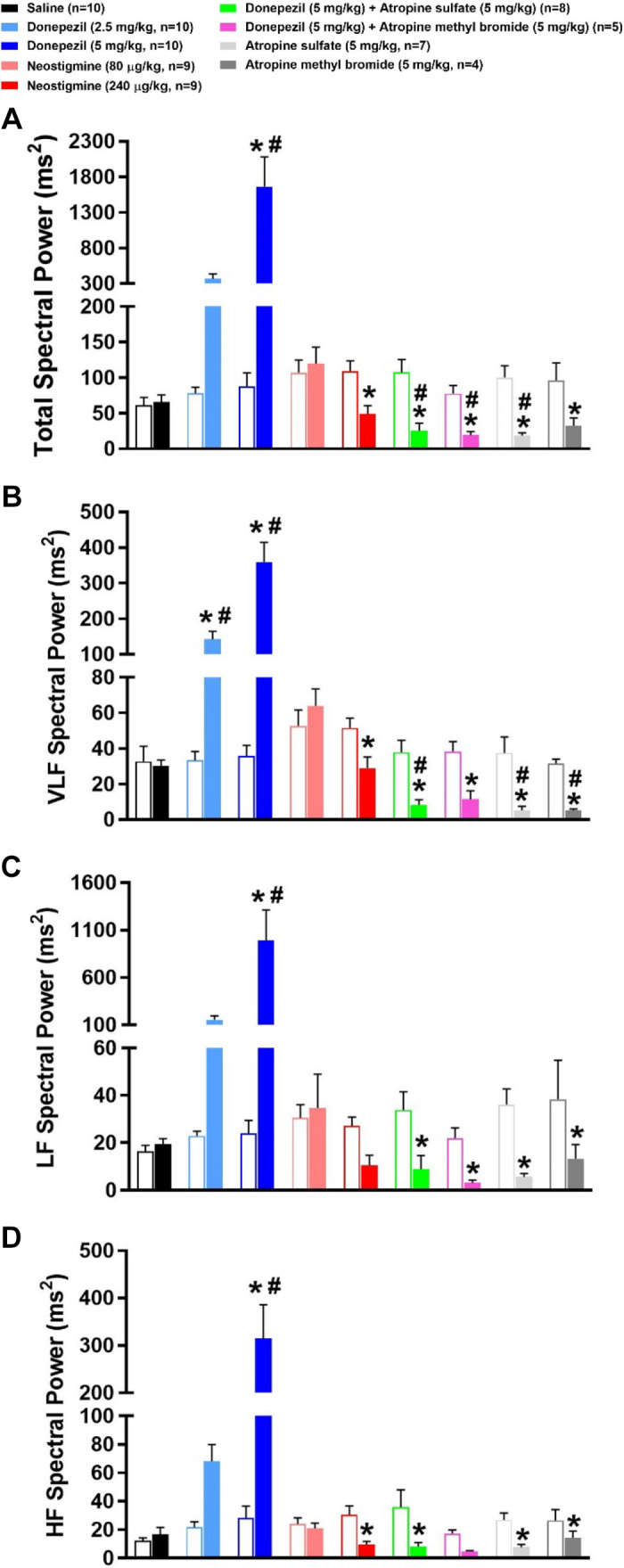

Effects of Donepezil, Neostigmine, and Muscarinic Receptor Blockade on Frequency-Domain Analysis of PI Variability

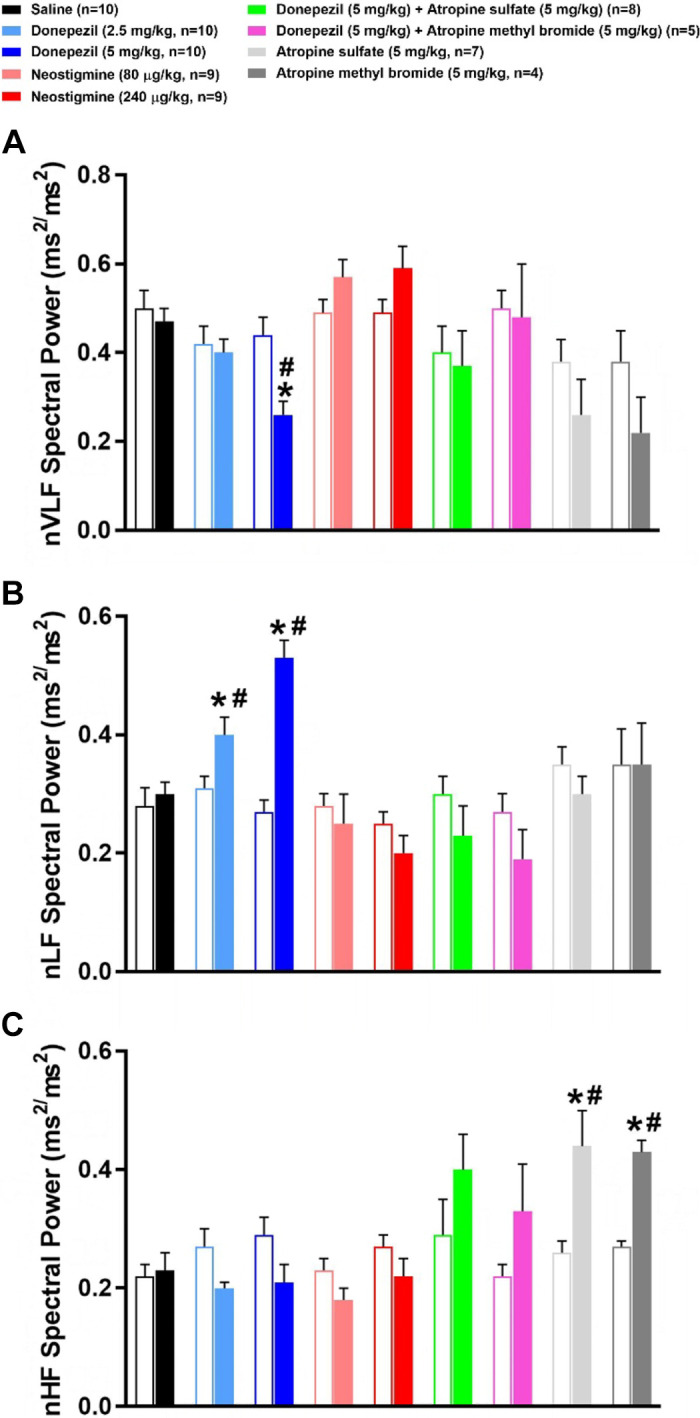

Figure 8 illustrates the frequency-domain analysis of PI variability during the first hour following drug or saline administration. As shown in Fig. 8A, donepezil substantially increased total PI variability power across all frequency ranges. Total spectral power was significantly reduced following 240 μg/kg neostigmine and all treatments involving the administration of atropine. In large part, similar effects were observed with VLF, LF, and HF spectral powers (Fig. 8, B–D). Figure 9 illustrates the PI power in the VLF, LF, and HF bands when normalized to total power (i.e., VLF + LF + HF). Donepezil caused a significant decrease in normalized VLF (nVLF) and increase in normalized LF (nLF) power as compared with baseline levels. Donepezil did not significantly alter normalized HF (nHF) power. Neostigmine did not significantly alter normalized spectral power within any frequency band. The same was true for all treatments involving atropine except that individually, atropine sulfate and atropine methyl bromide significantly increased nHF power. The increase in nHF power with atropine was likely due to the limited ability to further reduce HF power from baseline levels in mice (15).

Figure 8.

Effects of cholinergic drugs on the frequency-domain analyses of pulse interval (PI) variability. Frequency-domain analysis of PI variability before (baseline) and during the first hour following administration of saline, donepezil (2.5 mg/kg sc), donepezil (5 mg/kg sc), neostigmine (80 µg/kg ip), neostigmine (240 µg/kg ip), 5 mg/kg donepezil + atropine sulfate (5 mg/kg ip), 5 mg/kg donepezil + atropine methyl bromide (5 mg/kg ip), atropine sulfate, or atropine methyl bromide. Open and filled bars represent pre- and postdrug values following each treatment. Total PI variability spectral power (A) is the sum of the very low frequency (VLF, 0.01–0.15 Hz; B), low frequency (LF, 0.15–1.5 Hz; C), and high frequency (HF, 1.5–5 Hz; D) PI variability spectral powers. Data are means ± SE; n, number of animals. Two-way repeated-measures ANOVA with Holm–Sidak post hoc comparison was used to assess the effects of treatments vs. respective baseline values vs. saline. *P < 0.05, drug vs. respective baseline value; #P < 0.05, drug vs. saline.

Figure 9.

Effects of cholinergic drugs on the normalized frequency-domain analyses of pulse interval (PI) variability. Frequency-domain analysis of PI variability before (baseline) and during the first hour following administration of saline, donepezil (2.5 mg/kg sc), donepezil (5 mg/kg sc), neostigmine (80 µg/kg ip), neostigmine (240 µg/kg ip), 5 mg/kg donepezil + atropine sulfate (5 mg/kg ip), 5 mg/kg donepezil + atropine methyl bromide (5 mg/kg ip), atropine sulfate, or atropine methyl bromide. Open and filled bars represent pre- and postdrug values following each treatment. The PI variability spectral power of very low frequency (VLF, 0.01–0.15 Hz; A), low frequency (LF, 0.15–1.5 Hz; B), and high frequency (HF, 1.5–5 Hz; C) ranges was normalized to total PI variability spectral power (VLF + LF + HF). Data are means ± SE; n, number of animals. Two-way repeated-measures ANOVA with Holm–Sidak post hoc comparison was used to assess the effects of treatments vs. respective baseline values vs. saline. *P < 0.05, drug vs. respective baseline value; #P < 0.05, drug vs. saline.

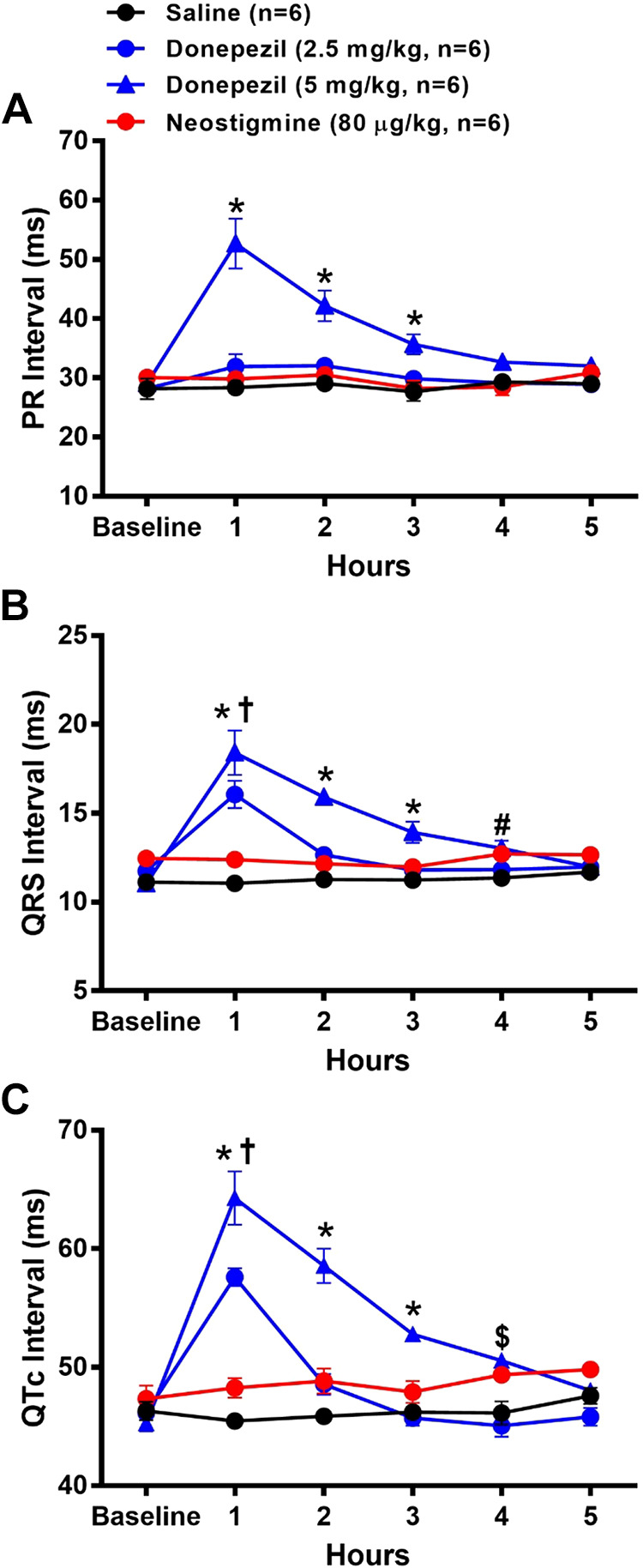

Effects of Anesthesia on HR Responses to Donepezil and Saline

The effects of anesthesia, induced 10 min following drug administration, on HR responses to saline (n = 6) and donepezil (n = 6) are shown in Fig. 10A. At 15 and 20 min following drug administration (5 and 10 min following anesthesia), HR was significantly lowered following donepezil versus saline administration. Although HR significantly decreased in anesthetized mice administered saline, HR significantly increased in anesthetized mice administered donepezil such that no significant differences were observed at 25- and 30-min after drug administration (10 and 15 min following anesthesia) as compared with saline. Carbachol led to a significant decrease in HR (219 ± 22 beats/min) as compared with HR values (448 ± 9 beats/min) at 15 min following anesthesia.

Figure 10.

Effects of anesthesia on heart rate (HR) responses to donepezil. Saline or donepezil (5 mg/kg sc) was administered to mice before (A) or after (B) administration of isoflurane anesthesia. A: saline or donepezil were administered 10 min before administration of anesthesia. After mice were anesthetized and allowed to stabilize for 5 min on a heated table, HR was recorded for 15 min. B: saline or donepezil was administered in anesthetized mice. Mice were first anesthetized and allowed to stabilize for 5 min. Then HR was recorded for 5 min before administration of saline or donepezil and for 20 min thereafter. No significant differences in HR were observed following administration of saline vs. donepezil. Data are means ± SE; n, number of animals. Two-way repeated-measures ANOVA with Holm–Sidak post hoc comparison was used to assess the effects of saline vs. donepezil over time. *P < 0.05, vs. 15-min time point in mice administered saline; †P < 0.05, vs. 15- and 20-min time points in mice administered donepezil; #P < 0.05, saline vs. donepezil; &P < 0.05, vs. baseline in mice administered saline; $P < 0.05, vs. baseline in mice administered donepezil.

The HR responses to saline (n = 4) and donepezil (n = 4), administered after mice were anesthetized, are shown in Fig. 10B. When administered in anesthetized mice, no significant differences in HR were observed following administration of saline versus donepezil. In both groups, HR significantly decreased over time to a similar extent, likely due to the effects of anesthesia. Carbachol again led to a significant decrease in HR (158 ± 16 beats/min) as compared with HR values (463 ± 21) at 20 min following anesthesia.

DISCUSSION

Despite a growing interest in the use of centrally acting AChE inhibitors in inflammatory diseases, the autonomic and cholinergic pathways mediating their beneficial effects remain incomplete. We assessed the cardiovascular and temperature effects of donepezil in combination with central or peripheral muscarinic receptor antagonists in conscious mice as a method to interrogate the autonomic and cholinergic pathways involved. The data show that donepezil results in robust hypothermia and bradycardia due to activation of muscarinic receptors. However, despite the almost twofold decrease in HR, MAP was initially maintained at baseline levels and increased after the bradycardia resolved. The mechanisms responsible for the BP response to donepezil are complex and likely involve both central and peripheral cholinergic receptors. Finally, donepezil did not enhance normalized HR variability indices related to parasympathetic modulation, despite the marked bradycardia. Our data in conscious mice are consistent with previous studies in other conscious species that have demonstrated that systemic administration of centrally acting AChE inhibitors, such as donepezil, modulates both parasympathetic and sympathetic efferent activity to different target tissues, in part, via muscarinic pathways.

Effects of Donepezil on Temperature Regulation

Consistent with previous studies in rodents (23, 36, 37), we found that donepezil, but not neostigmine, caused a rapid decrease in rectal and core body temperatures in mice. The hypothermic response could be blocked by atropine but not atropine methyl bromide, indicating that increased ACh concentration in the brain after donepezil administration stimulated muscarinic receptors to produce hypothermia. Previous work established that nonselective muscarinic receptor agonists cause hypothermia in rodents by stimulating central muscarinic receptors, and studies with muscarinic receptor knockout mice have specifically implicated the M2 subtype (38, 39). Central muscarinic receptors regulate temperature in rodents by controlling brown adipose tissue (BAT) thermogenesis and heat loss from the tail (40). Both effectors are regulated by the firing of postganglionic sympathetic nerves, which stimulate BAT thermogenesis and decrease tail blood flow to prevent heat loss. Elegant studies using mice have established that cholinergic neurons in the dorsomedial hypothalamus project to the brainstem region that drives BAT thermogenesis and that activation of these neurons decreases BAT activity and core body temperature (41). Previous studies in rats have also shown that central administration of physostigmine increases tail blood flow and skin temperature, which were attributed to an associated increase in BP (42). However, our data indicate that the donepezil-induced hypothermia is independent of the pressor response because atropine sulfate largely inhibited hypothermia but not the increase in BP. Based on this evidence, we suggest that donepezil causes hypothermia, at least in part, by stimulating central muscarinic receptors to decrease sympathetic drive to BAT and/or cutaneous tail vessels, but additional studies are needed to test this hypothesis.

Effects of Donepezil on HR

Bradycardia is a side effect in the clinical application of donepezil (43, 44); however, there is a dearth of data examining its effects on HR in conscious rodents. We found that donepezil caused marked bradycardia in conscious mice, which could be inhibited by both atropine and atropine methyl bromide. Consequently, the role of central versus peripheral muscarinic pathways in initiating the bradycardic response to donepezil could not be determined using this pharmacological approach. Despite these methodological issues, an important finding in the present study was that neostigmine, an AChE inhibitor that does not cross the blood-brain barrier, did not cause bradycardia. Although this was somewhat unexpected given that bradycardia is a reported side effect of neostigmine in clinical settings (45, 46), a potential explanation includes the low level of cardiac vagal tone in conscious mice (14, 15, 19). Indeed, a high level of vagal tone and locally released ACh within the heart may be required for AChE inhibitors to cause bradycardia. The evidence that isoflurane anesthesia, which reduces neural activity, both reverses and prevents the bradycardic effects of donepezil support this concept. Of note, AChE inhibitors that enter the central nervous system (CNS), but not those confined to the periphery, have been reported to increase vagal nerve efferent activity to the lymphoid tissue (6) and to the heart (47). Moreover, most (48–50) but not all (51) previous studies in conscious mice have shown that pyridostigmine, an AChE inhibitor that does not enter the CNS, does not cause bradycardia. Thus, unlike the modest bradycardia observed in clinical populations and other species, including rats (52), the majority of studies in conscious mice indicate that AChE inhibitors that do not enter the CNS do not evoke bradycardia. In addition, the bradycardia observed in other species with peripherally acting AChE inhibitors is very modest as compared with the almost twofold reduction in HR observed with donepezil in the present study. Nevertheless, future studies assessing vagal nerve efferent activity and/or whether central administration of muscarinic receptor antagonists can prevent donepezil-induced bradycardia in mice will be required to definitively establish the role of central muscarinic receptors in mediating this response.

It is important to emphasize that the dose of neostigmine used in the present study, although significantly lower than that of donepezil, was based on previously reported effective doses for both drugs in rodents (21, 22, 25–27, 30, 31, 33). Indeed, the highest dose of neostigmine used in the present study (0.24 mg/kg ip) is twofold lower than its LD50 (0.51 mg/kg) (53), whereas the highest dose of donepezil (5 mg/kg sc) is fourfold lower than its LD50 (22.5 mg/kg). The lower effective dose of neostigmine versus donepezil is likely due to neostigmine being a potent inhibitor of both AChE and butyrylcholinesterase, whereas donepezil only inhibits AChE (36, 37). Finally, neostigmine and donepezil both led to a similar degree of muscle fasciculation, which suggests that both drugs increased ACh levels similarly at the neuromuscular junction. Collectively, these findings give us confidence that the appropriate effective doses of neostigmine and donepezil were used in the present study.

Effects of Donepezil on MAP

Despite the substantial donepezil-induced bradycardia, MAP was initially maintained at baseline levels and increased after the bradycardia resolved. As reviewed by Brezenoff and Giuliano (11) and Buccafusco (54), our data are consistent with numerous studies showing that the acute administration of centrally acting AChE inhibitors increase BP in multiple species including humans. Although studies in conscious mice are lacking, there is strong evidence in rats that centrally acting AChE inhibitors enhance sympathetic activity to the peripheral vasculature and stimulate the release of vasopressin and catecholamines to increase BP (11, 54–58). Moreover, the pressor effects of centrally acting AChE inhibitors are often associated with significant bradycardia in conscious rats (55, 56, 59), similar to that observed in conscious mice in the present study. Of note, the acute pressor effects of centrally and/or peripherally acting AChE inhibitors may be different than their chronic effects, which have been reported to decrease BP in disease models (47, 60).

Activation of either muscarinic or nicotinic receptors within the CNS have been reported to increase BP in multiple species, although the evidence is stronger for muscarinic mechanisms (11, 54). Indeed, atropine, but not methylatropine, inhibits the pressor response to centrally acting AChE inhibitors (11, 56). Yet, atropine did not prevent the donepezil-induced increase in BP in the present study. Potential explanations for the disparate findings between the present and previous studies include differences in the centrally acting AChE inhibitors used, doses and routes of administration of drugs, as well as species. The inability of atropine to inhibit the pressor effects of donepezil suggests a potential contribution of nicotinic receptors. Indeed, the significant increase in BP associated with the high dose of neostigmine in the present study is consistent with a role of nicotinic and/or muscarinic receptors within the peripheral nervous system in mediating this response. However, the duration of the pressor response was longer following donepezil versus neostigmine. In this regard, it is also noteworthy that specific blockade of peripheral muscarinic receptors with atropine methyl bromide potentiated the increase in BP with donepezil in the present study. Similar findings have been reported during blockade of peripheral muscarinic receptors during administration of physostigmine (58) and oxotremorine (16), a centrally acting M1 receptor agonist, in conscious rats. Thus, it is possible that a centrally mediated muscarinic and/or nicotinic pressor response with donepezil was masked by stimulation of peripheral muscarinic receptors. Finally, it is also possible that increases in stroke volume, mediated via increases in cardiac filling times and/or sympathetically mediated contractility, contributed to the pressor response to donepezil. The cholinergic pathways contributing to the increase in BP with systemic administration of donepezil in conscious mice are complex and will require additional studies to identify the underlying mechanisms.

Effects of Donepezil on PI Variability

The analysis of HR variability is commonly used to assess cardiac sympathovagal balance. Increases in HR variability in the time domain (i.e., PI SD) and HF range of the power spectrum are thought to indicate enhanced cardiac parasympathetic modulation (14, 19) due to changes in vagal efferent activity related to the respiratory cycle (61). Previous studies have demonstrated that centrally acting AChE inhibitors increase (6, 7, 60, 62), whereas atropine decreases (14, 15, 19, 20, 35) PI SD and HF spectral power. Our data are consistent with these findings and thus support a major role of the parasympathetic nervous system in contributing to HR variations in the time domain and HF domain of the power spectrum.

However, caution must be used when interpreting indices of PI variability when average PI significantly changes, as was observed with donepezil. This is because the mathematical relationship between PI variability and average PI biases interpretation (18, 63–65). For this reason, we also calculated normalized indices of PI variability (i.e., PI CV and nHF spectral power). Of note, this approach has been used previously to assess the effects of various pharmacological and physiological interventions on cardiac sympathovagal balance (18). Despite the almost twofold decrease in HR in mice administered donepezil, neither PI CV nor nHF spectral power significantly differed from baseline values. We can only speculate as to why these normalized indices of HR variability were not enhanced by donepezil. It is possible that donepezil-induced increases in parasympathetic activity to the heart were attended by increases in sympathetic activity, which can modulate HF HR variability and oppose vagally mediated HR oscillations (63, 66, 67). It is also possible that donepezil influenced other factors, independent of the autonomic nervous system (e.g., mechanical factors related to changes in respiration or cardiac filling) that modulate HF HR variability (63). Any combination of these factors could have contributed to the lack of increase in PI CV or nHF PI power, despite the marked bradycardia, following donepezil administration.

In contrast to nHF PI power, donepezil significantly increased nLF and decreased nVLF PI power. Historically, the LF component of the HR variability spectrum was thought to primarily reflect sympathetic nerve activation and/or baroreceptor function (68–71). However, accumulating evidence indicates that LF variations in HR are modulated by a complex mixture of both sympathetic and parasympathetic influences, as well as other factors (63, 69, 72). Indeed, Billman (63) has estimated that parasympathetic activity contributes to a greater portion of LF power as compared with sympathetic activity. Much less is known about the origin of VLF HR fluctuations. Studies have suggested that they are a result of an intrinsic cardiac nervous system that is modulated by sympathetic and parasympathetic activity, as well as changes in temperature, metabolic processes, and various hormones (17, 61, 73). In any event, the extent to which the sympathetic versus parasympathetic nervous systems, or autonomic independent effects, contributed to the increase and decrease in nLF and nVLF power, respectively, after donepezil administration remain to be determined.

Perspectives and Significance

This study details the significant effects of donepezil on cardiovascular function and temperature regulation in conscious mice. Our data indicate that donepezil modulates both parasympathetic and sympathetic efferent pathways that regulate HR, cardiac rhythms and intervals, BP, and core body temperature. More specifically, it is possible that donepezil may decrease sympathetic activity to tissues important in thermoregulation, but increase sympathetic activity to most peripheral blood vessels and other organs. This is consistent with current viewpoints that sympathetic efferent nerve activity may be differentially regulated to various organ/tissue sites via central mechanisms (74, 75). The present study has important implications for the use of donepezil in clinical settings and potentially regarding its anti-inflammatory mechanisms. Although vagally mediated activation of the celiac ganglia and subsequent increase in splenic sympathetic nerve activity are thought to mediate this response, it is also possible that donepezil activates classical sympathetic pathways directed to the spleen.

GRANTS

These studies were supported by startup funds from ETSU and grants from the American Heart Association (17AIREA33660433), American Society of Nephrology Foundation for Kidney Research (Carl Gottschalk Research Scholar Grant), and National Institutes of Health (R15HL154067) to A. J. Polichnowski, a grant from the National Institute of Health (R15GM107949) to D. B. Hoover, and by the National Institutes of Health (C06RR0306551) to East Tennessee State University.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

A.J.P., T.E.B., and D.B.H. conceived and designed research; A.J.P., T.E.B., and D.B.H. performed experiments; A.J.P., G.A.W., T.E.B., and D.B.H. analyzed data; A.J.P., G.A.W., T.E.B., and D.B.H. interpreted results of experiments; A.J.P. prepared figures; A.J.P., G.A.W., and D.B.H. drafted manuscript; A.J.P., G.A.W., T.E.B., and D.B.H. edited and revised manuscript; A.J.P., G.A.W., T.E.B., and D.B.H. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Atri A. The Alzheimer’s disease clinical spectrum: diagnosis and management. Med Clin North Am 103: 263–293, 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2018.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim SH, Kandiah N, Hsu J-L, Suthisisang C, Udommongkol C, Dash A. Beyond symptomatic effects: potential of donepezil as a neuroprotective agent and disease modifier in Alzheimer’s disease. Br J Pharmacol 174: 4224–4232, 2017. doi: 10.1111/bph.14030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang H, Liao H, Ochani M, Justiniani M, Lin X, Yang L, Al-Abed Y, Wang H, Metz C, Miller EJ, Tracey KJ, Ulloa L. Cholinergic agonists inhibit HMGB1 release and improve survival in experimental sepsis. Nat Med 10: 1216–1221, 2004. doi: 10.1038/nm1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang H, Yu M, Ochani M, Amella CA, Tanovic M, Susarla S, Li JH, Wang H, Yang H, Ulloa L, Al-Abed Y, Czura CJ, Tracey KJ. Nicotinic acetylcholine receptor α7 subunit is an essential regulator of inflammation. Nature 421: 384–388, 2003. doi: 10.1038/nature01339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rosas-Ballina M, Olofsson PS, Ochani M, Valdes-Ferrer SI, Levine YA, Reardon C, Tusche MW, Pavlov VA, Andersson U, Chavan S, Mak TW, Tracey KJ. Acetylcholine-synthesizing T cells relay neural signals in a vagus nerve circuit. Science 334: 98–101, 2011. doi: 10.1126/science.1209985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pavlov VA, Ochani M, Gallowitsch-Puerta M, Ochani K, Huston JM, Czura CJ, Al-Abed Y, Tracey KJ. Central muscarinic cholinergic regulation of the systemic inflammatory response during endotoxemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103: 5219–5223, 2006. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600506103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Consolim-Colombo FM, Sangaleti CT, Costa FO, Morais TL, Lopes HF, Motta JM, Irigoyen MC, Bortoloto LA, Rochitte CE, Harris YT, Satapathy SK, Olofsson PS, Akerman M, Chavan SS, MacKay M, Barnaby DP, Lesser ML, Roth J, Tracey KJ, Pavlov VA. Galantamine alleviates inflammation and insulin resistance in patients with metabolic syndrome in a randomized trial. JCI Insight 2: e93340, 2017. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.93340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martelli D, Yao ST, McKinley MJ, McAllen RM. Reflex control of inflammation by sympathetic nerves, not the vagus. J Physiol 592: 1677–1686, 2014. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2013.268573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pongratz G, Straub RH. The sympathetic nervous response in inflammation. Arthritis Res Ther 16: 504, 2014. doi: 10.1186/s13075-014-0504-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pavlov VA, Parrish WR, Rosas-Ballina M, Ochani M, Puerta M, Ochani K, Chavan S, Al-Abed Y, Tracey KJ. Brain acetylcholinesterase activity controls systemic cytokine levels through the cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway. Brain Behav Immun 23: 41–45, 2009. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2008.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brezenoff HE, Giuliano R. Cardiovascular control by cholinergic mechanisms in the central nervous system. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 22: 341–381, 1982. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.22.040182.002013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gordon CJ, Grantham TA. Effect of central and peripheral cholinergic antagonists on chlorpyrifos-induced changes in body temperature in the rat. Toxicology 142: 15–28, 1999. doi: 10.1016/S0300-483X(99)00121-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gordon CJ, Samsam TE, Oshiro WM, Bushnell PJ. Cardiovascular effects of oral toluene exposure in the rat monitored by radiotelemetry. Neurotoxicol Teratol 29: 228–235, 2007. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2006.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Janssen BJ, Leenders PJ, Smits JF. Short-term and long-term blood pressure and heart rate variability in the mouse. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 278: R215–R225, 2000. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.2000.278.1.R215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Just A, Faulhaber J, Ehmke H. Autonomic cardiovascular control in conscious mice. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 279: R2214–R2221, 2000. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.2000.279.6.R2214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smith EC, Padnos B, Cordon CJ. Peripheral versus central muscarinic effects on blood pressure, cardiac contractility, heart rate, and body temperature in the rat monitored by radiotelemetry. Pharmacol Toxicol 89: 35–42, 2001. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0773.2001.d01-133.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Akselrod S, Gordon D, Ubel FA, Shannon DC, Berger AC, Cohen RJ. Power spectrum analysis of heart rate fluctuation: a quantitative probe of beat-to-beat cardiovascular control. Science 213: 220–222, 1981. doi: 10.1126/science.6166045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Billman GE. The effect of heart rate on the heart rate variability response to autonomic interventions. Front Physiol 4: 222, 2013. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2013.00222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gehrmann J, Hammer PE, Maguire CT, Wakimoto H, Triedman JK, Berul CI. Phenotypic screening for heart rate variability in the mouse. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 279: H733–H740, 2000. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.279.2.H733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thireau J, Zhang BL, Poisson D, Babuty D. Heart rate variability in mice: a theoretical and practical guide. Exp Physiol 93: 83–94, 2008. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2007.040733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Akinci SB, Ulu N, Yondem OZ, Firat P, Guc MO, Kanbak M, Aypar U. Effect of neostigmine on organ injury in murine endotoxemia: missing facts about the cholinergic antiinflammatory pathway. World J Surg 29: 1483–1489, 2005. doi: 10.1007/s00268-005-0073-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bitzinger DI, Gruber M, Tummler S, Malsy M, Seyfried T, Weber F, Redel A, Graf BM, Zausig YA. In vivo effects of neostigmine and physostigmine on neutrophil functions and evaluation of acetylcholinesterase and butyrylcholinesterase as inflammatory markers during experimental sepsis in rats. Mediators Inflamm 2019: 8274903, 2019. doi: 10.1155/2019/8274903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dronfield S, Egan K, Marsden CA, Green AR. Comparison of donepezil-, tacrine-, rivastigmine- and metrifonate-induced central and peripheral cholinergically mediated responses in the rat. J Psychopharmacol 14: 275–279, 2000. doi: 10.1177/026988110001400301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Geerts H, Guillaumat P-O, Grantham C, Bode W, Anciaux K, Sachak S. Brain levels and acetylcholinesterase inhibition with galantamine and donepezil in rats, mice, and rabbits. Brain Res 1033: 186–193, 2005. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.11.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hofer S, Eisenbach C, Lukic IK, Schneider L, Bode K, Brueckmann M, Mautner S, Wente MN, Encke J, Werner J, Dalpke AH, Stremmel W, Nawroth PP, Martin E, Krammer PH, Bierhaus A, Weigand MA. Pharmacologic cholinesterase inhibition improves survival in experimental sepsis. Crit Care Med 36: 404–408, 2008. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0B013E31816208B3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jiang Y, Zou Y, Chen S, Zhu C, Wu A, Liu Y, Ma L, Zhu D, Ma X, Liu M, Kang Z, Pi R, Peng F, Wang Q, Chen X. The anti-inflammatory effect of donepezil on experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis in C57 BL/6 mice. Neuropharmacology 73: 415–424, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2013.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kalb A, von Haefen C, Sifringer M, Tegethoff A, Paeschke N, Kostova M, Feldheiser A, Spies CD. Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors reduce neuroinflammation and -degeneration in the cortex and hippocampus of a surgery stress rat model. PLoS One 8: e62679, 2013. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0062679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Long JP, Eckstein JW. Ganglionic actions of neostigmine methylsulfate. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 133: 216–222, 1961. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Padmanabha Pillai N, Ramaswamy S, Gopalakrishnan V, Ghosh MN. Effect of cholinergic drugs on acute and chronic morphine dependence. Arch Int Pharmacodyn Ther 257: 146–154, 1982. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Steinebrunner N, Mogler C, Vittas S, Hoyler B, Sandig C, Stremmel W, Eisenbach C. Pharmacologic cholinesterase inhibition improves survival in acetaminophen-induced acute liver failure in the mouse. BMC Gastroenterol 14: 148, 2014. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-14-148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tyagi E, Agrawal R, Nath C, Shukla R. Effect of anti-dementia drugs on LPS induced neuroinflammation in mice. Life Sci 80: 1977–1983, 2007. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2007.02.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Varagic V. The action of eserine on the blood pressure of the rat. Br J Pharmacol Chemother 10: 349–353, 1955. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1955.tb00882.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yoshiyama Y, Kojima A, Ishikawa C, Arai K. Anti-inflammatory action of donepezil ameliorates tau pathology, synaptic loss, and neurodegeneration in a tauopathy mouse model. J Alzheimers Dis 22: 295–306, 2010. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-100681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hoover DB, Ozment TR, Wondergem R, Li C, Williams DL. Impaired heart rate regulation and depression of cardiac chronotropic and dromotropic function in polymicrobial sepsis. Shock 43: 185–191, 2015. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0000000000000272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Laude D, Baudrie V, Elghozi J-L. Effects of atropine on the time and frequency domain estimates of blood pressure and heart rate variability in mice. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 35: 454–457, 2008. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2008.04895.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Duysen EG, Li B, Darvesh S, Lockridge O. Sensitivity of butyrylcholinesterase knockout mice to (–)-huperzine A and donepezil suggests humans with butyrylcholinesterase deficiency may not tolerate these Alzheimer’s disease drugs and indicates butyrylcholinesterase function in neurotransmission. Toxicology 233: 60–69, 2007. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2006.11.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Khan I, Ibrar A, Zaib S, Ahmad S, Furtmann N, Hameed S, Simpson J, Bajorath J, Iqbal J. Active compounds from a diverse library of triazolothiadiazole and triazolothiadiazine scaffolds: synthesis, crystal structure determination, cytotoxicity, cholinesterase inhibitory activity, and binding mode analysis. Bioorg Med Chem 22: 6163–6173, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2014.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bymaster FP, Carter PA, Yamada M, Gomeza J, Wess J, Hamilton SE, Nathanson NM, McKinzie DL, Felder CC. Role of specific muscarinic receptor subtypes in cholinergic parasympathomimetic responses, in vivo phosphoinositide hydrolysis, and pilocarpine-induced seizure activity. Eur J Neurosci 17: 1403–1410, 2003. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02588.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bymaster FP, McKinzie DL, Felder CC, Wess J. Use of M1-M5 muscarinic receptor knockout mice as novel tools to delineate the physiological roles of the muscarinic cholinergic system. Neurochem Res 28: 437–442, 2003. doi: 10.1023/a:1022844517200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tan CL, Knight ZA. Regulation of body temperature by the nervous system. Neuron 98: 31–48, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2018.02.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jeong JH, Lee DK, Blouet C, Ruiz HH, Buettner C, Chua S Jr, Schwartz GJ, Jo Y-H. Cholinergic neurons in the dorsomedial hypothalamus regulate mouse brown adipose tissue metabolism. Mol Metab 4: 483–492, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2015.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pires W, Wanner SP, La GR, Rodrigues LO, Silveira SA, Coimbra CC, Marubayashi U, Lima NR. Intracerebroventricular physostigmine enhances blood pressure and heat loss in running rats. J Physiol Pharmacol 58: 3–17, 2007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Colovic MB, Krstic DZ, Lazarevic-Pasti TD, Bondzic AM, Vasic VM. Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors: pharmacology and toxicology. Curr Neuropharmacol 11: 315–335, 2013. doi: 10.2174/1570159x11311030006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Park-Wyllie LY, Mamdani MM, Li P, Gill SS, Laupacis A, Juurlink DN. Cholinesterase inhibitors and hospitalization for bradycardia: a population-based study. PLoS Med 6: e1000157, 2009. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Arsura EL, Brunner NG, Namba T, Grob D. Adverse cardiovascular effects of anticholinesterase medications. Am J Med Sci 293: 18–23, 1987. doi: 10.1097/00000441-198701000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pakala RS, Brown KN, Preuss CV. Cholinergic Medications. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, 2021. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pham GS, Wang LA, Mathis KW. Pharmacological potentiation of the efferent vagus nerve attenuates blood pressure and renal injury in a murine model of systemic lupus erythematosus. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 315: R1261–R1271, 2018. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00362.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bernatova I, Babal P, Grubbs RD, Morris M. Acetylcholinesterase inhibition affects cardiovascular structure in mice. Physiol Res 55, Suppl 1: S89–S97, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bernatova I, Dubovicky M, Price WA, Grubbs RD, Lucot JB, Morris M. Effect of chronic pyridostigmine bromide treatment on cardiovascular and behavioral parameters in mice. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 74: 901–907, 2003. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(03)00012-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Joaquim LF, Farah VM, Bernatova I, Fazan R, Grubbs R Jr, Morris M. Enhanced heart rate variability and baroreflex index after stress and cholinesterase inhibition in mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 287: H251–H257, 2004. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01136.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Correa WG, Durand MT, Becari C, Tezini GC, do Carmo JM, de Oliveira M, Prado CM, Fazan R Jr, Salgado HC. Pyridostigmine prevents haemodynamic alterations but does not affect their nycthemeral oscillations in infarcted mice. Auton Neurosci 187: 50–55, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2014.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Santos-Almeida FM, Girao H, da Silva CA, Salgado HC, Fazan R Jr.. Cholinergic stimulation with pyridostigmine protects myocardial infarcted rats against ischemic-induced arrhythmias and preserves connexin43 protein. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 308: H101–H107, 2015. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00591.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Strelnik AD, Petukhov AS, Zueva IV, Zobov VV, Petrov KA, Nikolsky EE, Balakin KV, Bachurin SO, Shtyrlin YG. Novel potent pyridoxine-based inhibitors of AChE and BChE, structural analogs of pyridostigmine, with improved in vivo safety profile. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 26: 4092–4094, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2016.06.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Buccafusco JJ. The role of central cholinergic neurons in the regulation of blood pressure and in experimental hypertension. Pharmacol Rev 48: 179–211, 1996. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lazartigues E, Brefel-Courbon C, Tran MA, Montastruc JL, Rascol O. Spontaneously hypertensive rats cholinergic hyper-responsiveness: central and peripheral pharmacological mechanisms. Br J Pharmacol 127: 1657–1665, 1999. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lazartigues E, Freslon JL, Tellioglu T, Brefel-Courbon C, Pelat M, Tran MA, Montastruc JL, Rascol O. Pressor and bradycardic effects of tacrine and other acetylcholinesterase inhibitors in the rat. Eur J Pharmacol 361: 61–71, 1998. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(98)00717-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mathis KW, Molina PE. Central acetylcholinesterase inhibition improves hemodynamic counterregulation to severe blood loss in alcohol-intoxicated rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 297: R437–R445, 2009. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00170.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Milutinovic S, Murphy D, Japundzic-Zigon N. Central cholinergic modulation of blood pressure short-term variability. Neuropharmacology 50: 874–883, 2006. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2005.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.da Fonseca SF, Mendonca VA, Silva SB, Domingues TE, Melo DS, Martins JB, Pires W, Santos CFF, de Fatima Pereira W, Leite LHR, Coimbra CC, Leite HR, Lacerda ACR. Central cholinergic activation induces greater thermoregulatory and cardiovascular responses in spontaneously hypertensive than in normotensive rats. J Therm Biol 77: 86–95, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.jtherbio.2018.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lataro RM, Silva CA, Tefe-Silva C, Prado CM, Salgado HC. Acetylcholinesterase inhibition attenuates the development of hypertension and inflammation in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Am J Hypertens 28: 1201–1208, 2015. doi: 10.1093/ajh/hpv017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Shaffer F, McCraty R, Zerr CL. A healthy heart is not a metronome: an integrative review of the heart's anatomy and heart rate variability. Front Psychol 5: 1040, 2014. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Okazaki Y, Zheng C, Li M, Sugimachi M. Effect of the cholinesterase inhibitor donepezil on cardiac remodeling and autonomic balance in rats with heart failure. J Physiol Sci 60: 67–74, 2010. doi: 10.1007/s12576-009-0071-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Billman GE. The LF/HF ratio does not accurately measure cardiac sympatho-vagal balance. Front Physiol 4: 26, 2013. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2013.00026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.de Geus EJC, Gianaros PJ, Brindle RC, Jennings JR, Berntson GG. Should heart rate variability be “corrected” for heart rate? Biological, quantitative, and interpretive considerations. Psychophysiology 56: e13287, 2019. doi: 10.1111/psyp.13287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sacha J. Interaction between heart rate and heart rate variability. Ann Noninvasive Electrocardiol 19: 207–216, 2014. doi: 10.1111/anec.12148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cohen MA, Taylor JA. Short-term cardiovascular oscillations in man: measuring and modelling the physiologies. J Physiol 542: 669–683, 2002. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.017483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Taylor JA, Myers CW, Halliwill JR, Seidel H, Eckberg DL. Sympathetic restraint of respiratory sinus arrhythmia: implications for vagal-cardiac tone assessment in humans. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 280: H2804–H2814, 2001. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.280.6.H2804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Heart rate variability: standards of measurement, physiological interpretation and clinical use. Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and the North American Society of Pacing and Electrophysiology. Circulation 93: 1043–1065, 1996. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Billman GE. Heart rate variability—a historical perspective. Front Physiol 2: 86, 2011. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2011.00086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Pagani M, Lombardi F, Guzzetti S, Rimoldi O, Furlan R, Pizzinelli P, Sandrone G, Malfatto G, Dell'Orto S, Piccaluga E. Power spectral analysis of heart rate and arterial pressure variabilities as a marker of sympatho-vagal interaction in man and conscious dog. Circ Res 59: 178–193, 1986. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.59.2.178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sleight P, La Rovere MT, Mortara A, Pinna G, Maestri R, Leuzzi S, Bianchini B, Tavazzi L, Bernardi L. Physiology and pathophysiology of heart rate and blood pressure variability in humans: is power spectral analysis largely an index of baroreflex gain? Clin Sci (Lond) 88: 103–109, 1995. [Erratum in Clin Sci (Colch) 88: 733, 1995]. doi: 10.1042/cs0880103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Martelli D, Silvani A, McAllen RM, May CN, Ramchandra R. The low frequency power of heart rate variability is neither a measure of cardiac sympathetic tone nor of baroreflex sensitivity. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 307: H1005–H1012, 2014. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00361.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Taylor JA, Carr DL, Myers CW, Eckberg DL. Mechanisms underlying very-low-frequency RR-interval oscillations in humans. Circulation 98: 547–555, 1998. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.98.6.547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.McAllen RM, Tanaka M, Ootsuka Y, McKinley MJ. Multiple thermoregulatory effectors with independent central controls. Eur J Appl Physiol 109: 27–33, 2010. doi: 10.1007/s00421-009-1295-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Morrison SF. Differential control of sympathetic outflow. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 281: R683–R698, 2001. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.2001.281.3.R683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]