Abstract

Endothelial cell (EC) migration is critical for healing arterial injuries, such as those that occur with angioplasty. Impaired re-endothelialization following arterial injury contributes to vessel thrombogenicity, intimal hyperplasia, and restenosis. Oxidized lipid products, including lysophosphatidylcholine (lysoPC), induce canonical transient receptor potential 6 (TRPC6) externalization leading to increased [Ca2+]i, activation of calpains, and alterations of the EC cytoskeletal structure that inhibit migration. The p110α and p110δ catalytic subunit isoforms of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) regulate lysoPC-induced TRPC6 externalization in vitro. The goal of this study was to assess the in vivo relevance of those in vitro findings to arterial healing following a denuding injury in hypercholesterolemic mice treated with pharmacologic inhibitors of the p110α and p110δ isoforms of PI3K and a general PI3K inhibitor. Pharmacologic inhibition of the p110α or the p110δ isoform of PI3K partially preserves healing in hypercholesterolemic male mice, similar to a general PI3K inhibitor. Interestingly, the p110α, p110δ, and the general PI3K inhibitor do not improve arterial healing after injury in hypercholesterolemic female mice. These results indicate a potential new role for isoform-specific PI3K inhibitors in male patients following arterial injury/intervention. The results also identify significant sex differences in the response to PI3K inhibition in the cardiovascular system, where female sex generally has a cardioprotective effect. This study provides a foundation to investigate the mechanism for the sex differences in response to PI3K inhibition to develop a more generally applicable treatment option.

Keywords: arterial healing, PI3-kinase, p110α, p110δ, TRPC6

INTRODUCTION

Cardiovascular disease is a devastating disorder that has a major impact on length and quality of life. The number of cardiovascular interventions (angioplasties, stents, and vascular grafts) performed in 2040 is expected to be 2.06 times the number performed in 2008 (1). The long-term results of all vascular interventions are compromised by intimal hyperplasia and continued thrombogenicity of the incompletely endothelialized surface. Delayed endothelial cell (EC) healing contributes to prolonged vessel thrombogenicity, stent thrombosis, and vascular dysfunction with impaired endothelium-dependent response to flow abnormalities (2, 3). If an EC surface is re-established early after arterial injury, intimal hyperplasia is minimal (4). Identifying factors that inhibit endothelial migration is one step toward improving the long-term patency of vascular interventions.

EC migration and many other EC functions are regulated by the influx of Ca2+ through calcium channels (5). EC monolayer disruption results in an influx of Ca2+ from the extracellular milieu. A brief, localized spike in [Ca2+]i is essential to initiate migration (6), but a prolonged high plateau of [Ca2+]i inhibits EC migration. A generalized, sustained increase in [Ca2+]i, such as that induced by lysoPC, disrupts time- and site-specific changes in focal adhesions and cytoskeleton that are required for cell movement, and thus inhibits EC migration required to repair monolayer disruption (5). EC has multiple Ca2+ entry pathways, and lysoPC activates canonical transient receptor potential 6 (TRPC6) and TRPC5 channels, but not voltage-gated Ca2+ channels (5, 7). TRPC channels are now considered among the most important Ca2+ permeable channels in EC [see Ref. (8) for review]. In the vasculature, TRPC channels participate in the regulation of arterial tone, vascular permeability, vascular remodeling, and intimal hyperplasia (8, 9), and are important in cell migration (7). Previous studies in TRPC6−/− mice provide compelling evidence of the importance of this cascade in vivo. In wild-type mice on a high-fat diet, re-endothelialization of injured carotid arteries is dramatically reduced compared with chow-fed mice. In contrast, hypercholesterolemia does not inhibit re-endothelialization of the injury in TRPC6−/− mice (10).

Despite considerable effort, identifying a specific TRPC6 inhibitor has been challenging. In our previous studies, we have shown that oxidized lipid products induce TRPC6 externalization by activating phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) (11). In vascular biology, class I PI3K isoforms are the most well characterized (12). Class I PI3K generates phosphatidylinositol (3,4,5)-trisphosphate (PIP3) (15) in the inner leaflet of the plasma membrane, and resultant increase in PIP3 production leads to TRPC6 externalization followed by a rise in [Ca2+]i and alteration of the cytoskeleton (5). Alteration of the cytoskeleton inhibits EC migration across an area of injury. In vascular cells, Class I PI3K isoforms also participate in a variety of intracellular signaling processes, including nitric oxide synthesis, endothelial cell-leukocyte interaction, angiogenesis, and endothelial progenitor cell biology (12).

PI3K’s role in TRPC6 externalization makes PI3K a candidate for therapeutic intervention to improve EC migration and arterial healing after injury, especially in the setting of hypercholesterolemia, which is one of the major risk factors for vascular disease. The challenge with targeting PI3K is its involvement in multiple intracellular signaling pathways and that PI3K has an estimated 50–100 down-stream effectors (16). To minimize the off-target effect of PI3K inhibition, identifying and inhibiting the specific PI3K p110 catalytic subunit isoforms (p110α, p110β, p110δ, and p110γ) responsible for the lysoPC-induced increase in TRPC6 externalization and decreased EC migration could improve arterial healing. Our previous in vitro studies show that the p110α and p110δ isoforms, but not the p110β or p110γ isoforms, are responsible for the increased PIP3 production, increased TRPC6 externalization, and decreased migration of EC in the presence of lysoPC (17).

The goal of this study was to use our in vitro findings (17) and assess their relevance to arterial healing in vivo following a denuding injury in hypercholesterolemic mice. Isoform-specific inhibitors to p110α and p110δ and pan-class I PI3K inhibitors are FDA approved or currently in late-stage clinical trials for various solid tumor cancers, lymphoma, and leukemia (18). BYL-719, CAL-101, and BKM-120 were selected for use in this study due to their oral bioavailability and similar drug delivery. BYL-719 is a potent p110α-specific inhibitor that is 50- to 250-fold more selective for p110α, as compared with the other catalytic subunit isoforms (19). CAL-101 is a potent p110δ-specific inhibitor that is 250- to 2500-fold more selective for the p110δ isoform, as compared with the other catalytic subunit isoforms (20). BKM-120 is a general Class I PI3K inhibitor, inhibiting all class IA PI3K catalytic subunit isoforms (p110α, β, δ, and γ), and has similar potency against p110α, p110β, and p110δ, but moderately less potency against p110γ (21). Repurposing existing isoform-specific PI3K inhibitors provides a novel approach to promoting EC healing after vascular intervention such as angioplasty or implantation of vascular bypass grafts.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Pharmacologic Inhibition of PI3K Isoforms

Isoform-specific inhibitors of p110α, BYL-719 (Alpelisib; Selleck Chemicals, LLC, Houston, TX; Cat. No. S2814), and p110δ, CAL-101 (Idelalisib; Selleck Chemicals, LLC, Cat. No. S226), and a general PI3K inhibitor, BKM-120 (Buparlisib; Selleck Chemicals, LLC, Cat. No. S2247) were obtained. For in vitro studies, the inhibitors were dissolved DMSO to generate a stock solution and then diluted in DMEM to achieve desired treatment concentration. For in vivo studies, the BYL-719 (50 mg/kg/day) (22), CAL-101 (50 mg/kg/day) (23), and BKM-120 (50 mg/kg/day) (24) were suspended in methyl cellulose (0.5% in distilled water, 100 µL; Sigma-Aldrich, Inc., St. Louis, MO; Cat. No. M7027) and administered by oral gavage.

EC Harvest and Culture

Bovine aortic EC (BAEC) (unknown sex) were harvested from fresh bovine aortas (abattoir) after collagenase treatment and cultured as previously described (7). Experiments were performed using EC from passage 4 to 10. Immortalized human umbilical vein cells (EA.hy926) (unknown sex) were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Hyclone Laboratories, Logan, UT) and 1 µg/mL gentamicin.

PIP3 Production by ELISA

After being made quiescent in serum-free medium for 12 h, PI3K inhibitors were added to confluent EC as indicated. Following the manufacturer’s protocol, PIP3 was extracted using a PIP3 Mass ELISA kit (Echelon Biosciences, Salt Lake City, UT), and samples read on a Spectramax 190 microplate reader (Molecular Devices, San Jose, CA) at 450 nm.

Immunoprecipitation and Immunoblot Analysis of Proteins

After confluent EC were made quiescent in serum-free DMEM for 12 h, specified agents were added. Target proteins were immunoprecipitated as previously described (25). Cell lysates were stored at –20°C until analyzed.

A 4%–20% gradient SDS-PAGE was used to separate proteins (50 µg/lane of total protein) as previously described (25). TRPC6 proteins were detected by antibodies specific for TRPC6 (1:500, Cell Signaling Technology; Cat. No. 16716). After incubation of the blots with a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (1:1,000, Cell Signaling Technology; Cat. No. 7074), the signal was developed using a chemiluminescent reagent (Invitrogen, Brookfield, WI). The blots were then stripped and reprobed using an anti-actin antibody (1:1,000; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA; Cat. No. MA1-744) and a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (1:1,000; Cell Signaling Technology; Cat. No. 7076) to verify equal loading. Images were acquired on Carestream BIOMAX MR autoradiography film (Carestream Health, Inc., Rochester, NY) and then scanned with an Epson Perfection V600 Photo using EPSON scan software. ImageJ software (NIH, Bethesda, MD) was used to quantitate protein band density.

Biotinylation of Proteins on EC Cell Surface to Detect TRPC6 Externalization

Biotinylation assay, as previously described (7), was used to determine externalization of TRPC6 channels. To biotinylate externalized proteins, EC was incubated with Sulfo-NHS-Biotin (2 mg/mL; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA; Cat. No. 21217). After lysis of the EC, the lysates were incubated with streptavidin-agarose beads. After collection, the biotinylated proteins were released from the beads, separated, and resolved by SDS-PAGE, and detected by immunoblot analysis. Immunoblot analysis was also performed on an aliquot of cell lysate removed before incubation with the streptavidin-agarose beads to determine total TRCP6 protein in the lysates.

Measurement of [Ca2+]i

ECs at 80% confluence were loaded with Calbryte 520 AM dye (AAT Bioquest, Sunnyvale CA; Cat. No. 36310), an FITC-conjugated fluorophore, following the manufacturer’s protocol. After incubation for 35 min, the EC was suspended in tubes and loaded into the sort chamber of a BD FACSMelody cell sorter (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) maintained at 37°C. After allowing the baseline to settle, lysoPC (12.5 µmol/L; 1-palmitol-2-hydroxy-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine; Avanti Polar Lipids, Alabaster, AL) was added. Relative changes in [Ca2+]i were read using the kinetic reading mode at Ex/Em 490/525 nm. FlowJo v10 software (BD Biosciences) was used to analyze the kinetics data.

EC Migration Assay

Confluent EC was made quiescent in serum-free DMEM for 16 h before the migration assay. The EC was incubated with specified agents, and the razor scrape migration assay was initiated, and migration was assessed at 24 h as previously described (5). Using NIH ImageJ (NIH, Bethesda, MD), migrating EC was quantitated by an observer blinded to the experimental condition.

Proliferation Assay

EC was cultured to 70%–80% confluence in DMEM containing 10% fetal calf serum. After removing the medium, EC was washed twice with PBS, and then, DMEM without FBS was applied. Following the manufacturer’s protocol, the Quick Cell Proliferation Kit II (Abcam, Cambridge, MA; Cat. No. ab65475) was used to assess the number of viable cells. A Spectramax 190 microplate reader (Molecular Devices) was used to measure absorbance at 450 nm. Camptothecin (8 µM) and fibroblast growth factor (FGF; 20 nmol/L) were used as negative and positive controls, respectively.

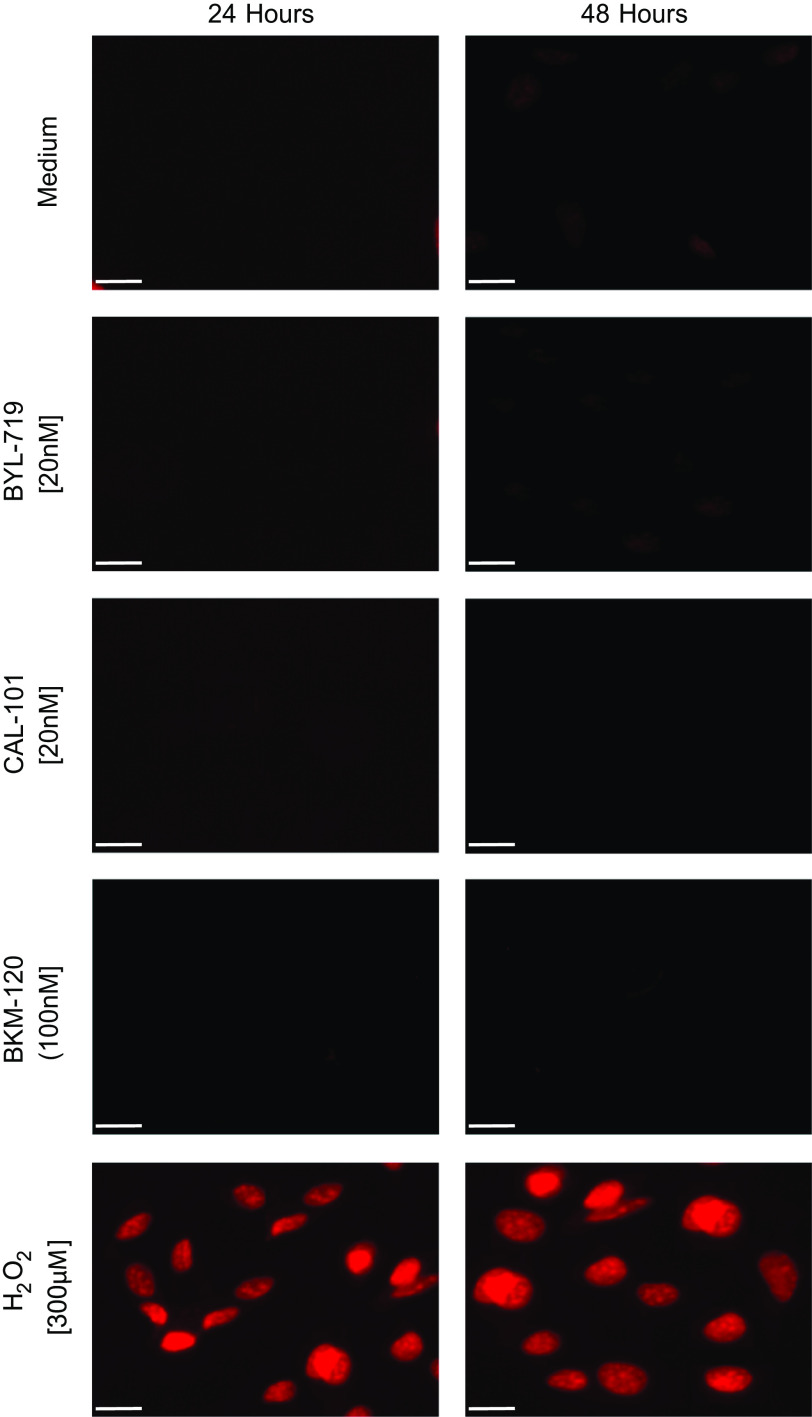

EC Apoptosis Assay

EC were grown to 70%–80% confluence and were treated as appropriate for 24 h and 48 h. Apoptosis was assessed with a Cell Apoptosis PI Detection Kit (GenScript USA, Inc., Piscataway, NJ). Fluorescence of multiple groups of cells per well was evaluated using an Olympus 1X70 inverted fluorescent microscope (Olympus, Waltham, MA) with an excitation wavelength of 535 nm and an emission wavelength of 617 nm. H2O2 (300 µmol/L) was used as a positive control for apoptosis.

Mouse Carotid Injury

Six-week-old male C57Bl/6 mice were randomly divided into 10 study groups: 1) chow diet (Envigo, Madison, WI; Cat. No. 2920X), 2) high cholesterol (HC) diet (Envigo; Cat. No. TD.150869) containing 21% hydrogenated vegetable oil and 0.2% cholesterol by weight, 3) chow diet plus vehicle (methyl cellulose, 0.5% in distilled water), 4) HC diet plus vehicle, 5) chow + BYL-719, 6) HC + BYL-719, 7) chow + CAL-101, 8) HC + CAL-101, 9) chow + BKM-120, and 10) HC + BKM-120. Vehicle, BYL-719, CAL-101, or BKM-120 was administered daily via oral gavage starting two days before carotid injury and continued until the end of study. The dosing regimen for each inhibitor was based on the pharmacokinetics of BYL-719 (26), CAL-101 (27), and BKM-120 (13). The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approved the study protocol. The animal protocol and care complied with the American Association of Laboratory Care Guidelines and the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, Institute of Laboratory Animal Resources, Commission on Life Sciences, National Research Council, Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2011.

At 10 wk of age, the mice were anesthetized with isoflurane (1.5%–2.0%) administered via a vaporizer and maintained throughout the procedure. A perivascular electrical injury of the right common carotid artery was performed as previously described (28). Electrocautery (2 W of power) was applied to the artery for 3 s using custom bipolar forceps (Elmed, Inc., Addison, IL; Cat. No. 5000SP-M) to produce a 4-mm injury. Using immunohistochemistry and transmission electron microscopy techniques, prior studies have documented that the perivascular injury denudes the endothelium and injures the smooth muscle cell layer of the vessel without damaging the adventitial layer (14). The changes in the arterial wall are consistent with changes in arterial wall after angioplasty (29).

Mouse Carotid Artery Harvest and Analysis for EC Migration

At 96 h after carotid artery injury, when the injury is ∼50% healed in mice on a chow diet, the mice were anesthetized with an intraperitoneal injection of ketamine (80 mg/kg; West-Ward Pharmaceuticals, Eatontown, NJ) and xylazine (5 mg/kg; Akorn, Inc., Lake Forest, IL). Blood was drawn from the inferior vena cava and Evans Blue (5% in PBS, 100 µL, Sigma-Aldrich, Inc.; Cat. No. E2129) was injected intravenously to stain arteries not having an intact EC surface (28). After perfusion-fixation, the carotid arteries were removed, pinned flat, imaged with an Olympus SC50 camera (Olympus, Boston, MA), and analyzed to determine the amount of arterial healing using cellSens imaging software (Ver. 2.3, Olympus), as previously described (28). Scanning electron microscopy was used in prior studies to verify that Evans Blue accurately reflected the de-endothelialized artery (10, 28). The degree of endothelial healing was verified by a reviewer blinded to the treatment group.

Plasma Assays

Plasma levels of total cholesterol and lysoPC were assessed at the conclusion of the study. Plasma from blood collected at the time of carotid removal was stored under N2 at –80°C until analyzed. Total cholesterol was determined by a cholesterol oxidase method (Total Cholesterol Reagents; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA; Catalog No. TR13421), as previously described (30). Plasma lysoPC concentration was determined by an enzymatic method, as previously described (31).

Statistical Methods

Experimental results are represented as means (SD). Unless otherwise specified, in vitro experiments were performed in triplicate with cells cultured from three different animals or independent biological samples. All Western blots and EC migration images are representative images of at least three separate experiments. GraphPad Prism 8.2 (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA) was used to perform the statistical analysis. Student’s t test and analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test or Dunnett’s multiple comparison test were used for the analysis, as appropriate. Differences at P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

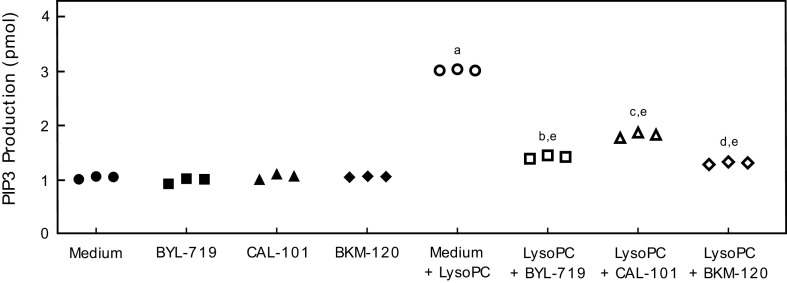

Pharmacologic Inhibition of PI3K Catalytic Subunit Isoforms Blocks lysoPC-Induced PIP3 Production

To verify BYL-719, CAL-101, and BKM-120 effectively inhibited PI3K activation, lysoPC-induced PIP3 production was assessed in BAEC pretreated with BYL-719, CAL-101, or BKM-120. Basal PIP3 production was similar in BAEC and BAEC pretreated with BYL-719, CAL-101, or BKM-120 (n = 3; Fig. 1). LysoPC significantly increased PIP3 production in control BAEC (n = 3; P < 0.001 compared with no lysoPC; Fig. 1). Pretreatment with BYL-719 significantly decreased the lysoPC-induced PIP3 production by 53% (n = 3; P < 0.001 compared with lysoPC without pretreatment; Fig. 1). Pretreatment with CAL-101 decreased the lysoPC-induced PIP3 production by 41% (n = 3; P < 0.001 compared with lysoPC without pretreatment; Fig. 1). BKM-120 pretreatment decreased lysoPC-induced PIP3 production by 57% (n = 3; P < 0.001 compared with lysoPC without pretreatment; Fig. 1). These results confirm the ability of inhibitors to effectively block lysoPC-induced PI3 kinase catalytic activity.

Figure 1.

Pharmacologic inhibition of p110α, p110δ, or all catalytic subunit isoforms or PI3K inhibited lysoPC-induced PIP3 production. BAECs were preincubated with BYL-719 (20 nmol/L), CAL-101 (20 nmol/L), or BKM-120 (100 nmol/L) for 1 h. The BAECs were then incubated with lysoPC (12.5 µmol/L) for 15 min. PIP3 production in the presence or absence of lysoPC was determined by ELISA and represented by scatter plots (n = 3 independent biological samples, aP < 0.001 compared with medium alone, bP < 0.001 compared with BYL-719, cP < 0.001 compared with CAL-101, dP < 0.001 compared with BKM-120, eP < 0.001 compared with medium + lysoPC). Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test. BAEC, bovine aortic endothelial cell; lysoPC, lysophosphatidylcholine; PI3K, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase; PIP3, phosphatidylinositol (3–5)-trisphosphate.

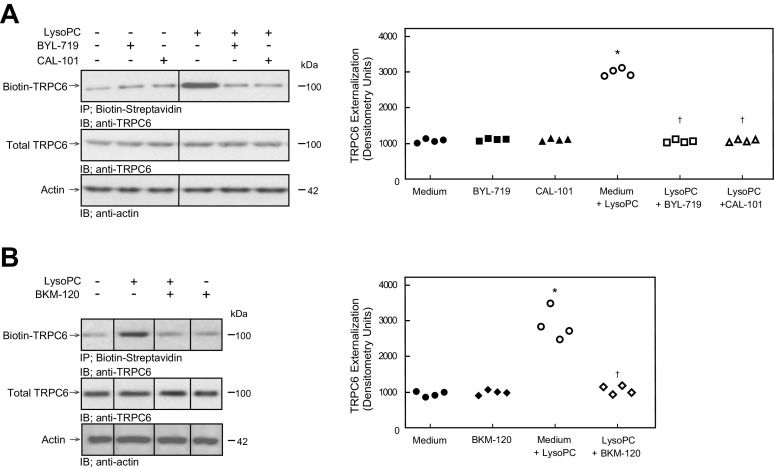

Pharmacologic Inhibition of PI3K Catalytic Subunit Isoforms Blocks lysoPC-Induced TRPC6 Externalization

The effect of the selective pharmacologic inhibitors of p110α (BYL-719) and p110δ (CAL-101) and the nonselective catalytic subunit inhibitor (BKM-120) on lysoPC-induced TRPC6 externalization was evaluated by biotinylation assay. At baseline, TRPC6 externalization in control BAEC and BAEC pretreated with BYL-719, CAL-101, or BKM-120 was similar (n = 4, Fig. 2, A and B). LysoPC exposure increased TRPC6 externalization in BAEC by 181%–190% (n = 4; P < 0.001 compared with no lysoPC; Fig. 2, A and B). Pretreatment with BYL-719, CAL-101, or BKM-120 inhibited the increase in TRPC6 externalization (n = 4; Fig. 2, A and B) following lysoPC exposure. The individual isoform-specific inhibitors decreased TRPC6 externalization to a level similar to the general inhibitor.

Figure 2.

Pharmacologic inhibition of p110α, p110δ, or all catalytic subunit isoforms of PI3K inhibited lysoPC-induced TRPC6 externalization. BAECs were preincubated with BYL-719 (20 nmol/L), CAL-101 (20 nmol/L), or BKM-120 (100 nmol/L) for 1 h. The BAECs were then incubated with lysoPC (12.5 µmol/L) for 15 min. A, left: externalization of TRPC6 after BYL-719 or CAL-101 pretreatment was detected by biotinylation assay and total TRPC6 by immunoblot analysis. Actin served as loading control (n = 4 independent biological samples). Black lines between lanes indicate lanes rearranged from the same gel. All bands are from the same gel. Right: densitometry measurements of TRPC6 externalization are represented as scatter plots (n = 4 independent biological samples, *P < 0.001 compared with medium alone, †P < 0.001 compared with medium + lysoPC). B, left: externalization of TRPC6 after BKM-120 pretreatment was detected by biotinylation assay and total TRPC6 by immunoblot analysis. Actin served as loading control (n = 4 independent biological samples). Black lines between lanes indicate lanes rearranged from the same gel. All bands are from the same gel. Right: densitometry measurements of TRPC6 externalization are represented as scatter plots (n = 4 independent biological samples, *P < 0.001 compared with medium alone, †P < 0.001 compared with medium + lysoPC). Statistical analysis for A and B was performed using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test. BAEC, bovine aortic endothelial cell; lysoPC, lysophosphatidylcholine; PI3K, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase; TRPC6, canonical transient receptor potential 6 channels.

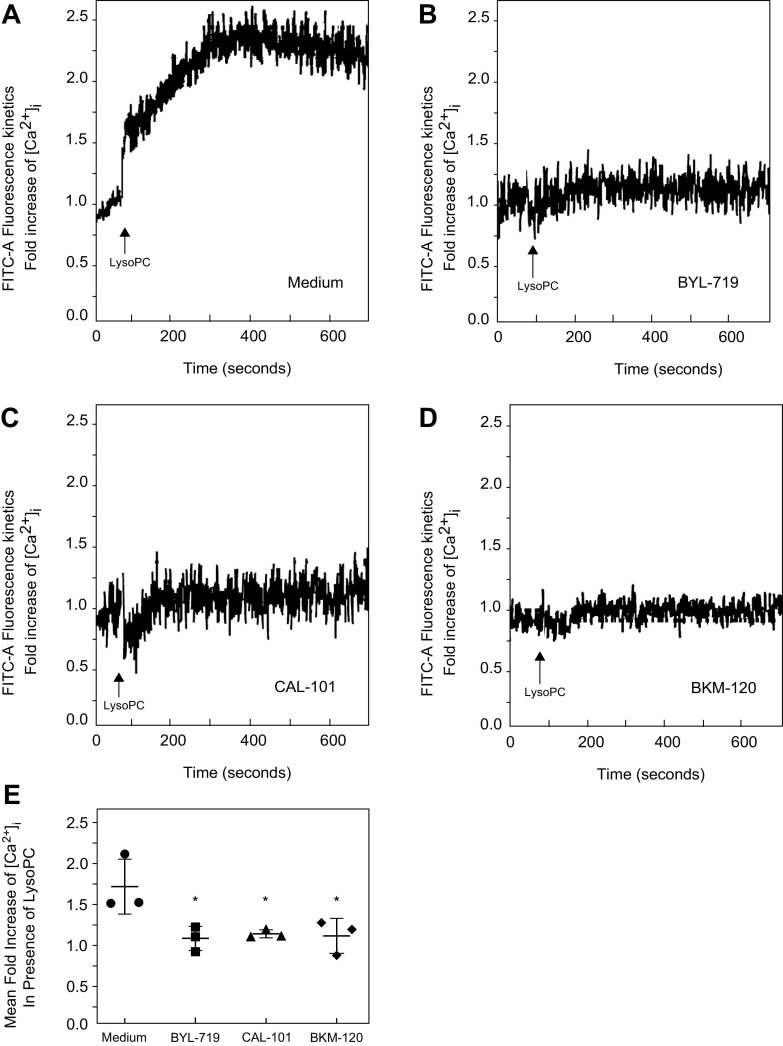

The effect of PI3K isoform-specific inhibitors on [Ca2+]i in the presence of lysoPC was evaluated. LysoPC significantly increased [Ca2+]i in control (Medium) cells (Fig. 3A). Inhibition of p110α with BYL-719 blocked the rise in [Ca2+]i in response to lysoPC compared to control cells (n = 3; Fig. 3, B and E). Similarly, inhibition of p110δ with CAL-101 blocked the rise in [Ca2+]i after the addition of lysoPC compared to control cells (n = 3; Fig. 3, C and E). Inhibition of all the catalytic subunit isoforms with BKM-120 inhibited the lysoPC-induced rise in [Ca2+]i compared to control cells (n = 3; Fig. 3, D and E). BKM-120 inhibited the lysoPC induced rise [Ca2+]i to the same level as BYL-719 or CAL-101. These results support the important role of the p110α and p110δ catalytic subunit isoforms of PI3K in lysoPC-induced TRPC6 activation.

Figure 3.

Pharmacologic inhibition of p110α, p110δ, or all catalytic subunit isoforms of PI3K inhibited the rise in [Ca2+]i in the presence of lysoPC. BAECs were preincubated with BYL-719 (20 nmol/L), CAL-101 (20 nmol/L), or BKM-120 (100 nmol/L) for 1 h. The ECs were loaded with the FITC-conjugated fluorophore Calbryte 520 AM dye. The ECs were suspended in tubes and loaded into the sort chamber of a BD FACSMelody cell sorter maintained at 37°C. After adjusting the baseline, lysoPC (12.5 µmol/L) was added. A–D: using the kinetic reading mode at Ex/Em 490/525 nm, relative changes in [Ca2+]i in medium (A), BYL-719 (B), CAL-101 (C), or BKM-120 (D) treated cells were determined (representative images of n = 3 independent biologic samples). E: fold increase in [Ca2+]i measured by difference in mean [Ca2+]i at baseline and after addition of lysoPC (12.5 µmol/L) presented as a dot whisker plot (n = 3 independent biological samples, *P < 0.03 compared to medium). Statistical analysis performed using one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparison test against medium. BAEC, bovine aortic endothelial cell; lysoPC, lysophosphatidylcholine; PI3K, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase.

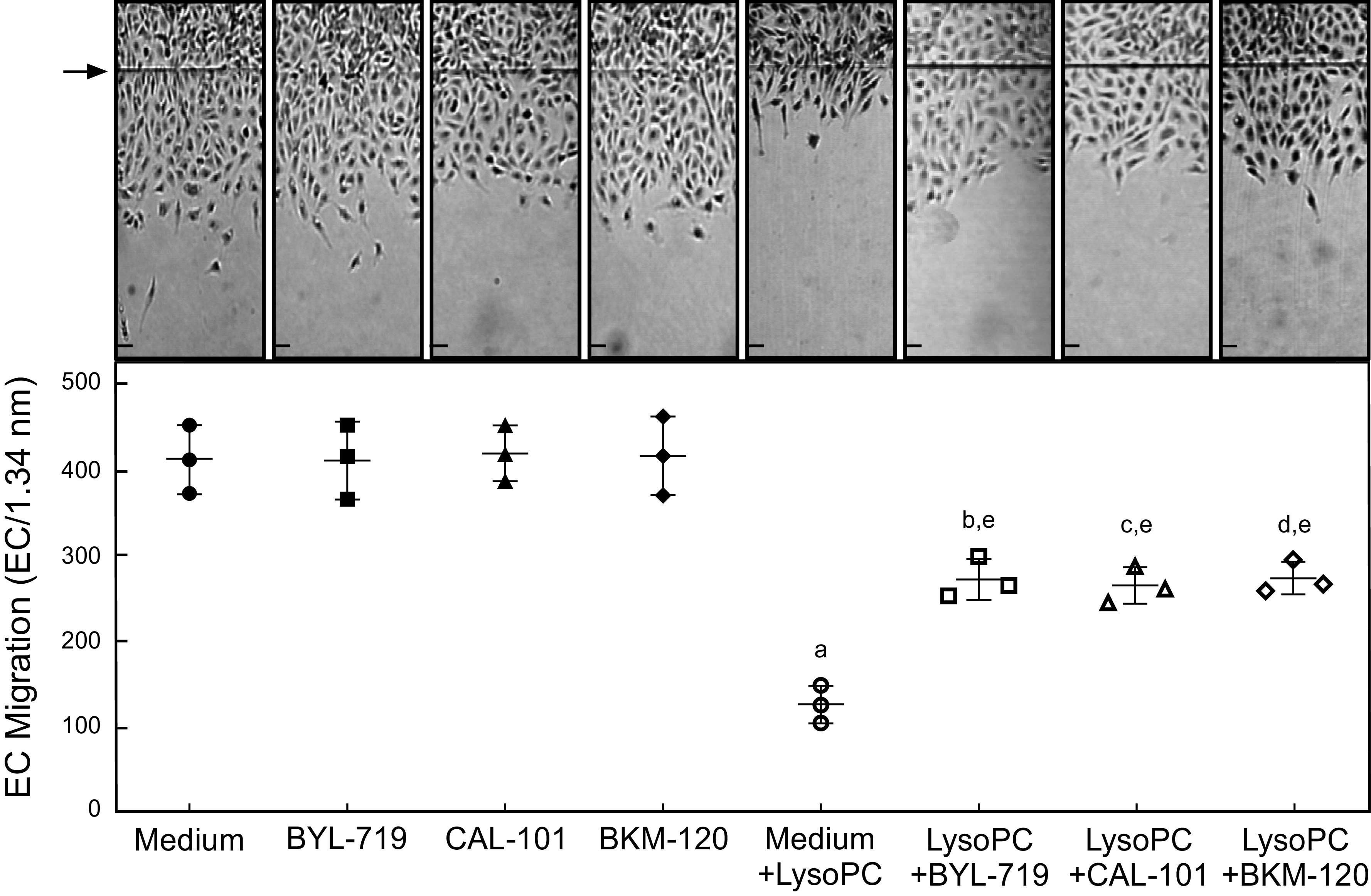

Pharmacologic Inhibition of PI3K Catalytic Subunit Isoforms Partially Preserved EC Migration in the Presence of lysoPC

Basal EC migration of control BAEC and BAEC pretreated with BYL-719, CAL-101, or BKM-120 was similar (n = 3, Fig. 4). In the presence of lysoPC, migration in control BAEC was inhibited by 69% (n = 3; P < 0.001 compared with no lysoPC; Fig. 4). In BAEC pretreated with BYL-719, CAL-101, or BKM-120, lysoPC inhibited migration by only 34%, 38%, or 34%, respectively (for each pretreatment, n = 3; P < 0.001 compared with the inhibitor pretreatment and no lysoPC; Fig. 4). These results indicate that treatment with a selective p110α, a selective p110δ, or a general PI3K pharmacological inhibitor can partially preserve BAEC migration in the presence of lysoPC. The individual isoform-specific inhibitors preserve migration to a level similar to the general inhibitor.

Figure 4.

Pharmacologic inhibition of p110α, p110δ, or all catalytic subunit isoforms of PI3K partially preserved EC migration in the presence of lysoPC. BAECs were made quiescent for 12 h. The ECs were preincubated with BYL-719 (20 nmol/L), CAL-101 (20 nmol/L), or BKM-120 (100 nmol/L) for 1 h. The migration assay was initiated and the migration in the presence or absence of lysoPC (12.5 µmol/L was assessed after 24 h). Top: representative images are shown at ×40 magnification (scale bar, 200 µm). Arrow indicates the starting line of EC migration. Lower: dot whisker plot of EC migration represented as mean (SD) (n = 3 independent biological samples, aP < 0.001 compared with medium alone, bP < 0.003 compared with BYL-719, cP < 0.001 compared with CAL-101, dP < 0.003 compared with BKM-120, and eP < 0.003 compared with medium + lysoPC). Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test. BAEC, bovine aortic endothelial cell; EC, endothelial cell; lysoPC, lysophosphatidylcholine; PI3K, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase.

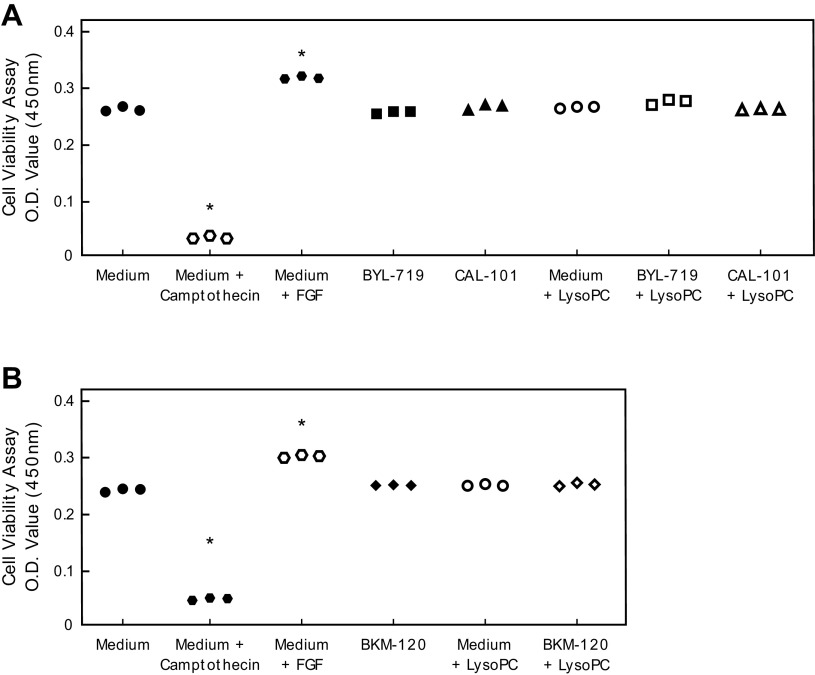

To verify the changes in BAEC migration were not related to changes in BAEC proliferation or apoptosis, proliferation and apoptosis assays were performed. BYL-719, CAL-101, and BKM-120 had no effect on BAEC cell viability in the presence or absence of lysoPC (Fig. 5). BYL-719, CAL-101, and BKM-120 did not increase apoptosis in BAEC after 24 h or 48 h (Fig. 6).

Figure 5.

Pharmacologic inhibition of p110α, p110δ, or all catalytic subunit isoforms of PI3K did not stimulate EC proliferation. BAEC were preincubated with BYL-719 (20 nmol/L) (A), CAL-101 (20 nmol/L) (A), or BKM-120 (100 nmol/L) (B) for 1 h. BAECs were incubated with or without lysoPC (12.5 µmol/L) for 24 h. EC proliferation was assessed using the Quick Cell Proliferation Kit II (Abcam) with absorbance measured at 450 nm. FGF (20 nmol/L) and camptothecin (8 µmol/L) were used as positive and negative controls. O.D. measurements (450 nm) are presented as scatter plots (n = 3 independent biological samples, *P < 0.001 compared with medium alone). Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparison test against medium alone. BAEC, bovine aortic endothelial cell; EC, endothelial cell; FGF, fibroblast growth factor; lysoPC, lysophosphatidylcholine; PI3K, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase.

Figure 6.

Pharmacologic inhibition of p110α, p110δ, or all catalytic subunit isoforms of PI3K did not cause apoptosis of EC. Bovine aortic EC were incubated with BYL-719 (20 nmol/L), CAL-101 (20 nmol/L), or BKM-120 (100 nmol/L). Apoptosis was assessed with a Cell Apoptosis PI Detection Kit (GenScript USA, Inc., Piscataway, NJ). Under fluorescent microscopy, apoptotic cells show nuclear staining with propidium iodide. H2O2 (300 µM) was used as a positive control. Representative images 24 h and 48 h after addition of the inhibitor (n = 3 independent biological samples; scale bar, 40 µm). EC, endothelial cell; PI3K, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase.

P110α and/or p110δ Pharmacologic Inhibitors Reduce lysoPC-Induced PIP3 Production and TRPC6 Externalization, and Partially Preserve EC Migration in Human EC

To ensure the effects of pharmacologic inhibition of p110α with BYL-719, p110δ with CAL-101, or all the catalytic subunit isoforms with BKM-120 were not species-specific, the PIP3 production, TRPC6 externalization, and EC migration results were verified in human EA.hy926 EC.

Basal PIP3 production was similar in EA.hy926 EC and EA.hy926 EC pretreated with BYL-719, CAL-101, or BKM-120 (n = 3; Supplemental Fig. S1A; see https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.13369061.v1). LysoPC significantly increased PIP3 production in control EA.hy926 EC (n = 3; P < 0.001 compared with no lysoPC; Supplemental Fig. S1A). Pretreatment with BYL-719 significantly decreased the lysoPC-induced PIP3 production by 48% (n = 3; P < 0.001 compared with lysoPC without pretreatment; Supplemental Fig. S1A). Pretreatment with CAL-101 decreased the lysoPC-induced PIP3 production by 27% (n = 3; P < 0.001 compared with lysoPC without pretreatment; Supplemental Fig. S1A). BKM-120 pretreatment decreased lysoPC-induced PIP3 production by 65% (n = 3; P < 0.001 compared with lysoPC without pretreatment; Supplemental Fig. S1A).

Basal TRPC6 externalization was similar in EA.hy926 EC pretreated with BYL-719 (n = 4; Supplemental Fig. S1B), CAL-101 (n = 4; Supplemental Fig. S1B), or BKM-120 (n = 4; Supplemental Fig. S1C). LysoPC caused a significant increase in TRPC6 externalization, but BYL-719 (n = 4; Supplemental Fig. S1B), CAL-101 (n = 4; Supplemental Fig. S1B), and BKM-120 (n = 4; Supplemental Fig. S1C) blocked the increase in lysoPC-induced TPRC6 externalization when the EA.hy926 EC was pretreated with any of the inhibitors.

Basal migration of control EA.hy926 EC and EA.hy926 EC pretreated with BYL-719, CAL-101, or BKM-120 was similar (n = 3; Supplemental Fig. S1D). In the presence of lysoPC, migration of EA.hy926 EC decreased by 65%–69% (n = 3; P < 0.001 compared with no lysoPC; Supplemental Fig. S1D). In EA.hy926 EC pretreated with BYL-719, CAL-101, or BKM-120, lysoPC inhibited migration by only 36%, 36%, or 36%, respectively (for all pretreatments, n = 3; P < 0.001 compared with pretreatment without lysoPC; Supplemental Fig. S1D).

These results indicate that treatment with a selective p110α or a selective p110δ PI3K catalytic subunit pharmacological inhibitor can significantly inhibit TRPC6 externalization and preserve EC migration in the presence of lysoPC at levels similar to a general PI3K catalytic subunit inhibitor. The results are not species specific and strengthen the case that p110α and p110δ are the PI3K catalytic subunit isoforms involved in externalization of TRPC6 channels in the presence of lysoPC.

Pharmacologic Inhibition of PI3K Catalytic Subunit Isoforms Preserved Arterial Injury Healing in Hypercholesterolemic Mice

A total of 103 male and 106 female 10- to 12-wk-old C57Bl/6 mice were included in this study. Two male mice and 4 female mice were excluded from the analysis due to thrombosis of the injured carotid artery. One male and one female mouse were excluded because they died during the study period due to an esophageal injury related to oral gavage administration of the study drug. One mouse was excluded who died of respiratory failure while under anesthesia. The excluded mice were spread across multiple study groups, and the complication rate was lower than expected. Furthermore, the thrombosis rate was lower than the expected rate of 10%. Mice on the HC diet tended to weigh more at the time of injury as compared with the mice on a chow diet (Table 1), but the pharmacologic inhibitors had no effect on weight (Table 1).

Table 1.

Mouse data

| Group | Weight | Cholesterol, mmol/L | LysoPC, µmol/L | Arterial Healing, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chow | 22.4 (3.1) | 2.13 (0.59)a | 872.9 (208.6)a | 57.1 (6.2)a |

| Chow + Vehicle | 22.7 (3.9) | 2.00 (0.48)b | 855.5 (84.4)b | 58.1 (14.3)b |

| Chow + BYL-719 | 24.1 (3.8) | 2.46 (0.53)c | 953.6 (160.0)c | 57.8 (10.7) |

| Chow + CAL-101 | 25.0 (3.9) | 2.41 (0.43)d | 873.8 (134.7)d | 51.3 (11.1) |

| Chow + BKM-120 | 22.5 (2.9) | 2.47 (0.69)e | 890.3 (89.0)e | 50.7 (15.9) |

| HC | 24.5 (3.8) | 3.89 (0.88)a | 1,102.2 (171.7)a | 31.6 (11.5)a |

| HC + Vehicle | 24.9 (4.7) | 3.94 (0.83)b | 1,090.8 (146.5)b | 37.3 (11.6)b,f,g,h |

| HC + BYL-719 | 25.4 (3.8) | 3.70 (0.51)c | 1,107.8 (146.7)c | 46.8 (9.5)f |

| HC + CAL-101 | 26.4 (4.1) | 3.71 (0.72)d | 1,026.0 (99.3)d | 47.9 (12.3)g |

| HC + BKM-120 | 25.9 (4.4) | 3.79 (1.05)e | 1,196.7 (136.0)e | 47.0 (12.9)h |

Values are means (SD); n = 20 mice for all study groups. HC, high cholesterol; LysoPC, lysophosphatidylcholine.

Significant differences (P ≤ 0.05) are designated as:

abetween chow and high cholesterol;

bbetween chow + vehicle and HC + vehicle;

cbetween chow + BYL-719 and HC + BYL-719;

dbetween chow + CAL-101 and HC + CAL-101;

ebetween chow + BKM-120 and HC + BKM-120;

fbetween HC + vehicle and HC + BYL-719;

gbetween HC + vehicle and HC + CAL-101;

hbetween HC + vehicle and HC + BKM-120. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test.

In mice on the HC diet, plasma cholesterol, determined 96 h after carotid injury, was significantly higher compared with mice on the chow diet. Plasma cholesterol was 3.89 (0.88) mmol/L and 2.13 (0.59) mmol/L in mice on HC and chow diets, respectively (n = 20, P < 0.001; Table 1). Administration of the vehicle alone or with an inhibitor did not alter plasma cholesterol levels compared with mice on the corresponding diet without the vehicle (Table 1). For all pharmacologic inhibitors, the plasma cholesterol was significantly higher in mice on the HC diet + inhibitor compared with chow diet + inhibitor (n = 20, P < 0.001 for each pharmacologic inhibitor; Table 1).

Plasma lysoPC levels were determined from blood samples collected 96 h after carotid injury as a marker of systemic oxidative stress. In mice fed the HC diet, plasma lysoPC was significantly higher than in mice on the chow diet. Plasma lysoPC was 1102.2 (171.7) mmol/L and 872.9 (208.6) mmol/L in mice on HC and chow diets, respectively (n = 20, P < 0.001; Table 1). For vehicle alone and all inhibitors, the plasma lysoPC was significantly higher in mice on the HC diet compared with the same treatment group in mice on the chow diet (n = 20 in each group; P < 0.003 for each intervention; Table 1).

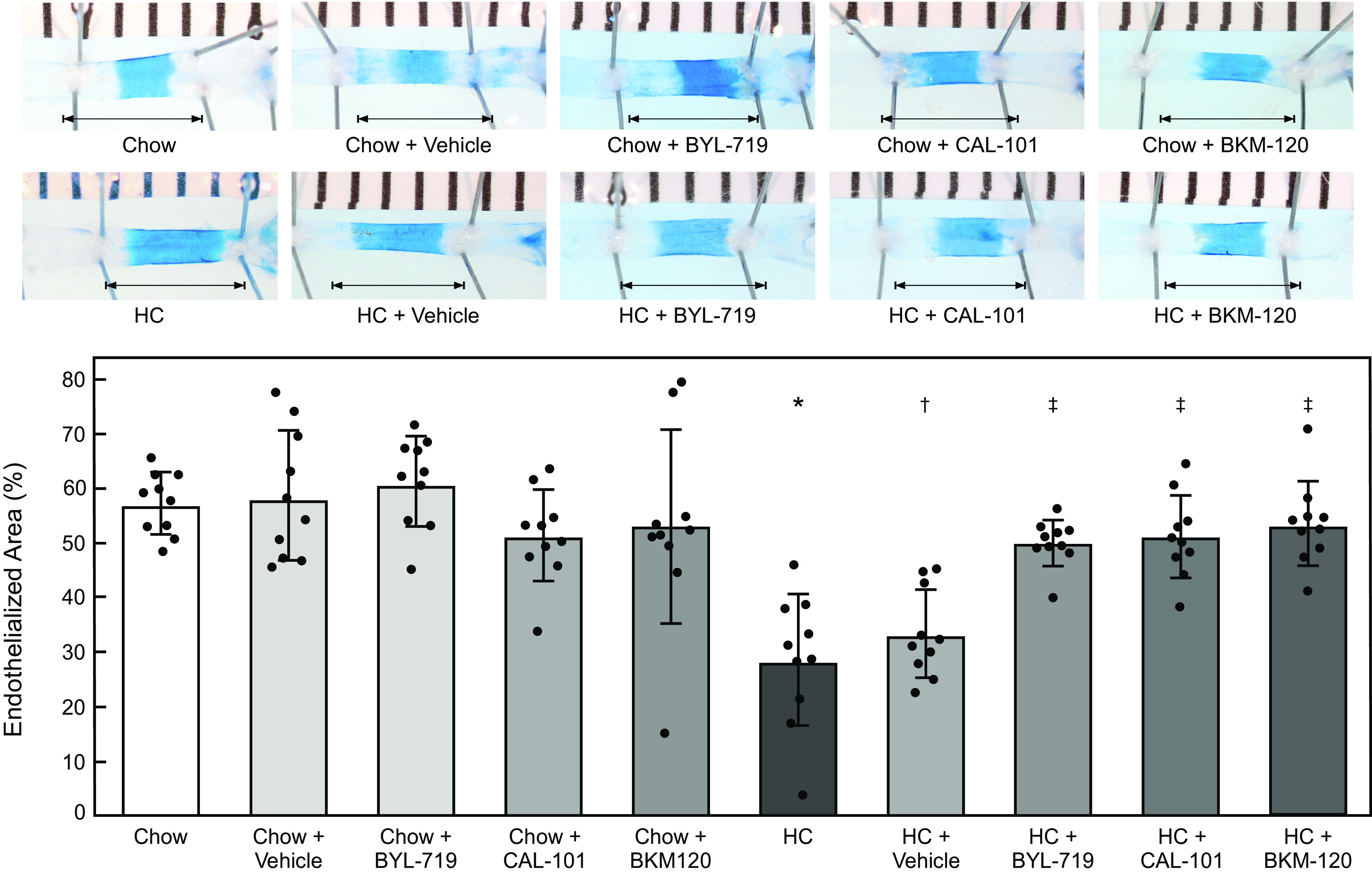

At 96 h after the electrocautery injury, carotid healing was quantitated. Mice on the chow diet healed 57.1% (6.2) of the injured area, but re-endothelialization in mice on the HC diet was significantly decreased with coverage of 31.6% (11.5) (n = 20; P < 0.001; Table 1). Administration of the vehicle alone did not significantly affect re-endothelialization in mice on either the chow or HC diets compared with mice on the corresponding diet that did not receive the vehicle (Table 1). BYL-719, CAL-101, and BKM-120 did not significantly impact re-endothelialization in mice on the chow diet, but did significantly improve arterial healing in hypercholesterolemic mice with EC healing of 46.8% (9.5), 47.9% (12.3), and 47.0% (12.9), respectively (for each drug: n = 20; P < 0.02 compared with HC + vehicle; Table 1). No significant difference was observed when comparing one pharmacologic inhibitor to the other inhibitors in mice on the same diet (Table 1).

Pharmacologic Inhibition of PI3K Improved Arterial Injury Healing in Hypercholesterolemic Male Mice but Not Female Mice

During subgroup analysis, significant differences were identified between male and female mice. Across all study groups, the female mice were significantly smaller than the male mice (n = 10 for each sex; P < 0.05 for each group; Tables 2 and 3), but the high cholesterol diet ± inhibitors did not significantly affect the weight of the mice when compared with mice of the same sex receiving the chow diet ± the inhibitors.

Table 2.

Male mouse data

| Group | Weight, g | Cholesterol, mmol/L | LysoPC, µmol/L | Arterial Healing, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chow | 25.2 (1.6) | 2.52 (0.51)a | 974.6 (165.0)b | 57.3 (5.7)b |

| Chow + Vehicle | 26.1 (1.8) | 2.13 (0.47)a,c | 918.2 (55.2)d,e | 58.8 (11.9)e |

| Chow + BYL-719 | 27.7 (0.9) | 2.88 (0.30)a | 1,097.8 (47.6)d,f | 61.3 (8.3) |

| Chow + CAL-101 | 28.2 (2.1) | 2.74 (0.30)a | 977.7 (99.3)g | 51.4 (8.4) |

| Chow + BKM-120 | 25.2 (1.0)h | 3.10 (0.30)a,c | 968.8 (31.1)h | 53.0 (17.8) |

| HC | 27.7 (2.6) | 4.43 (0.91)a | 1,169.3 (186.7)b | 28.5 (12.2)b |

| HC + Vehicle | 27.0 (3.4) | 4.66 (0.43)a,e | 1,203.5 (74.8)e,i | 33.3 (8.2)e,i,j,k |

| HC + BYL-719 | 28.3 (2.8) | 3.96 (0.48)a | 1,197.5 (105.1)f | 50.0 (4.3)i |

| HC + CAL-101 | 29.7 (2.0) | 4.21 (0.67)a | 1,084.7 (104.3)g,i | 51.1 (7.6)j |

| HC + BKM-120 | 30.0 (2.2)h | 4.47 (1.01)a | 1,298.1 (76.4)h | 53.6 (7.8)k |

Values are means (SD); n = 10 mice for all study groups. HC, high cholesterol; LysoPC, lysophosphatidylcholine.

Significant differences (P ≤ 0.05) are designated as:

abetween any chow group and any HC group;

bbetween chow and high cholesterol;

cbetween chow + vehicle and chow + BKM-120;

dbetween chow + vehicle and chow + BYL-719;

ebetween chow + vehicle and HC + vehicle;

fbetween chow + BYL-719 and HC + BYL-719;

gbetween chow + CAL-101 and HC + CAL-101;

hbetween chow + BKM-120 and HC + BKM-120;

ibetween HC + vehicle and HC + BYL-719;

jbetween HC + vehicle and HC + CAL-101;

kbetween HC + vehicle and HC + BKM-120. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test.

Table 3.

Female mouse data

| Group | Weight, g | Cholesterol, mmol/L | LysoPC, µmol/L | Arterial Healing, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chow | 19.7 (1.0) | 1.75 (0.38)a | 771.3 (204.0)b | 57.0 (7.0)b |

| Chow + Vehicle | 19.3 (1.7) | 1.87 (0.47)a | 792.8 (57.1)c | 57.4 (16.9)c |

| Chow + BYL-719 | 20.5 (1.1) | 2.03 (0.32)a | 809.3 (74.3)d | 54.2 (12.0) |

| Chow + CAL-101 | 21.9 (2.4) | 2.01 (0.24)a | 769.9 (66.7)e | 51.3 (13.8) |

| Chow + BKM-120 | 19.8 (0.8) | 1.85 (0.18)a | 811.7 (45.4)f | 48.4 (14.2) |

| HC | 21.4 (1.8) | 3.33 (0.35)a | 1,035.0 (131.9)b | 34.7 (10.4)b |

| HC + Vehicle | 22.8 (5.1) | 3.22 (0.33)a | 978.1 (107.2)c | 41.4 (13.4)c |

| HC + BYL-719 | 22.4 (1.9) | 3.45 (0.41)a | 1,018.2 (128.5)d | 43.5 (12.2) |

| HC + CAL-101 | 23.1 (2.9) | 3.21 (0.30)a | 967.2 (47.2)e | 44.6 (15.4) |

| HC + BKM-120 | 22.2 (2.4) | 3.12 (0.53)a | 1,095.4 (102.0)f | 40.4 (14.1) |

Values are means (SD); n = 10 mice for all study groups. HC, high cholesterol; LysoPC, lysophosphatidylcholine.

Significant differences (P ≤ 0.05) are designated as:

abetween any chow group and any HC group;

bbetween chow and high cholesterol;

cbetween chow + vehicle and HC + vehicle;

dbetween chow + BYL-719 and HC + BYL-719;

ebetween chow + CAL-101 and HC + CAL-101;

fbetween chow + BKM-120 and HC + BKM-120. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test.

When comparing mice of the same sex, the plasma cholesterol was significantly higher in HC ± the pharmacologic inhibitors compared with mice on the corresponding chow diet ± the inhibitors (Tables 2 and 3). However, plasma cholesterol was significantly lower in the female mice compared with the male mice in the same treatment group (n = 10 for each sex, P < 0.03 for each group; Tables 2 and 3), except for the chow + vehicle groups (P = 0.22).

In male mice (Table 2) or female mice (Table 3), plasma lysoPC was significantly higher in mice on the HC diet ± inhibitor compared with the corresponding chow diet ± inhibitor. Plasma lysoPC levels were significantly lower in female mice compared with male mice across all study groups, except for the HC group (n = 10 for each sex, P < 0.03 for each group; Tables 2 and 3). Furthermore, plasma lysoPC levels in female mice on high cholesterol diet ± inhibitor were not significantly different than corresponding male mice on the chow diet ± inhibitor, except with BKM-120 treatment (Tables 2 and 3).

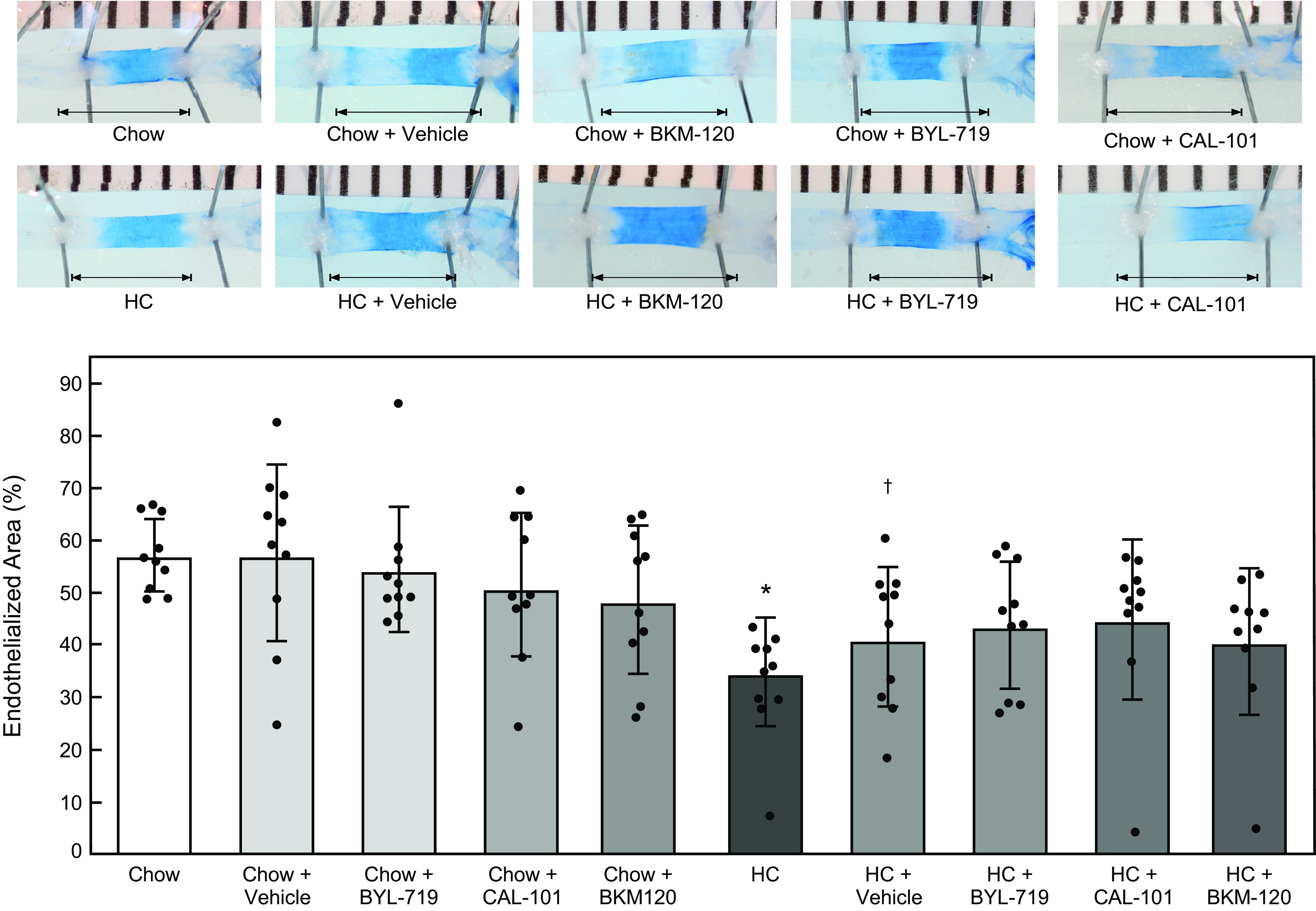

Hypercholesterolemia was associated with a significant decrease in endothelial healing in both male and female mice (Figs. 7 and 8 and Tables 2 and 3). The vehicle alone did not affect re-endothelialization in mice on either the chow or HC diets compared with mice on the corresponding diet without the vehicle. No inhibitor had a significant impact re-endothelialization in male (Fig. 7 and Table 2) or female (Fig. 8 and Table 3) mice on the chow diet. Treatment with BYL-719, CAL-101, and BKM-120 significantly improved arterial healing in hypercholesterolemic male mice with EC healing of 50.0% ± 4.3%, 51.1% (7.6), and 53.6% (7.8), respectively (for each drug: n = 10; P < 0.001 compared with HC + vehicle; Fig. 7 and Table 2). Unlike in male mice, treatment with BYL-719, CAL-101, and BKM-120 did not significantly improve arterial healing in hypercholesterolemic female mice with EC coverage of 43.5% (12.2), 44.6% (15.4), and 40.4% (14.1), respectively (for each drug: n = 10, P > 0.60 compared with HC + vehicle; Fig. 8 and Table 3). No significant difference was observed when comparing one pharmacologic inhibitor to the other two inhibitors in male (Fig. 7 and Table 2) or female (Fig. 8 and Table 3) mice on the same diet. These results indicate that pharmacologic inhibition p110α, p110δ, or all catalytic subunit isoforms of PI3K preserves endothelial healing in hypercholesterolemic male mice, but does not significantly improve arterial healing in hypercholesterolemic female mice.

Figure 7.

Pharmacologic inhibition of p110α, p110δ, or all catalytic subunit isoforms of PI3K partially preserved arterial healing in hypercholesterolemic male mice after injury. At 10 wk of age, male C57Bl/6 mice on a chow or HC diet underwent an electrical injury to the right carotid artery. Mice were treated via oral gavage with BYL-719 (50 mg/kg/day), CAL-101 (50 mg/kg/day), or BKM-120 (50 mg/kg/day) suspended in 0.5% methyl cellulose from 48 h prior to injury until 96 h after injury. At 96 h after injury, Evans Blue dye was injected intravenously to identify the area without an intact endothelial monolayer. Top: representative images of carotid arteries 96 h after electrical injury. The arrow identifies the length of the initial 4-mm injury. Bottom: re-endothelialization results shown as the percent of re-endothelialized area relative to the total injured area. Results are represented as the mean (SD) (n = 10 male mice for all treatment groups; *P < 0.001 compared with Chow, †P < 0.001 compared with Chow + Vehicle, ‡ P < 0.001 compared with HC + Vehicle). Statistical analysis was performed using unpaired Student’s t test. HC, high cholesterol; PI3K, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase.

Figure 8.

Pharmacologic inhibition of p110α, p110δ, or all catalytic subunit isoforms of PI3K does not significantly improve arterial healing in hypercholesterolemic female mice after injury. At 10 wk of age, female C57Bl/6 mice on a chow or HC diet underwent an electrical injury to the right carotid artery. Mice were treated via oral gavage with BYL-719 (50 mg/kg/day), CAL-101 (50 mg/kg/day), or BKM-120 (50 mg/kg/day) suspended in 0.5% methyl cellulose from 48 h prior to injury until 96 h after injury. At 96 h after injury, Evans Blue dye was injected intravenously to identify the area without an intact endothelial monolayer. Top: representative images of carotid arteries 96 h after electrical injury. The arrow identifies the length of the initial 4-mm injury. Bottom: re-endothelialization results shown as the percent of re-endothelialized area relative to the total injured area. Results are represented as the means ± SD (n = 10 female mice for all treatment groups; *P < 0.001 compared with Chow, †P = 0.03 compared with Chow + Vehicle). Statistical analysis was performed using unpaired Student’s t test. HC, high cholesterol; PI3K, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase.

DISCUSSION

Lipid oxidation products, including lysoPC, cause externalization of TRPC6 channels in part through activation of the p110α and p110δ catalytic subunit isoforms of PI3K and increased PIP3 production. When TRPC6 is anchored in the membrane, its activation leads to increased [Ca2+]i (32–34). This increased [Ca2+]i activates calpain causing cytoskeletal protein alterations and inhibition of EC migration (5).

This study is the first to report the role of the p110α and p110δ PI3K catalytic subunit isoforms in arterial healing after injury in hypercholesterolemic animals. Our previous in vitro studies showed that the p110α and p110δ PI3K catalytic subunit isoforms, but not the p110β or p110γ isoforms, are responsible for the lysoPC-induced increase in TRPC6 externalization and the associated decrease in EC migration (17). This study assessed the in vivo relevance of those in vitro findings by examining arterial healing following a denuding injury in hypercholesterolemic mice treated with pharmacologic inhibitors of PI3K and its p110α and p110δ isoforms. The pharmacologic inhibitors partially preserved healing in hypercholesterolemic male mice, but did not significantly improve arterial healing after injury in hypercholesterolemic female mice.

The lack of significant improvement in arterial healing in female hypercholesterolemic mice treated with the PI3K inhibitors in this study was unexpected. Although not statistically significant, hypercholesterolemic female mice tended to heal better than the male mice without PI3K inhibitor treatment. The trend was similar in hypercholesterolemic female mice receiving the vehicle without the inhibitor compared to the hypercholesterolemic male mice receiving the vehicle alone. The female mice used in this study are premenopausal, and our arterial healing results, without PI3K inhibitor treatment, are consistent with prior studies where female sex is generally considered cardioprotective in premenopausal women (35, 36). The explanation for better healing in female mice compared to male mice might be the effect of estrogen on the cardiovascular system and its regulation of antioxidant activity. Estrogen receptors (ERα and ERβ) are present in the plasma membrane of vascular EC (37), and upon activation, ERα regulates activation of superoxide dismutase 2 (SOD2) and ERβ regulates basal SOD2 levels in EC leading to decreased reactive oxygen species (38). That our female mice have lower oxidative stress is supported by their lower levels of lysoPC, and this would promote EC healing since reactive oxygen species inhibit EC migration and healing of arterial injuries.

Despite baseline improvement in arterial healing in hypercholesterolemic female mice, the response was blunted when treated with the PI3K inhibitors. Resistance to the PI3K inhibitors mice may explain the dampened response in hypercholesterolemic female mice. Based on the ER+ breast cancer literature, multiple pathways have been identified for PI3K inhibitor resistance. Inhibition of PI3K has been shown to cause compensatory activation of upstream receptor tyrosine kinases that limit the effectiveness of the PI3K inhibitors (39). ER signaling can also lead to persistent activation of downstream effectors in the PI3K signaling pathway that limits to effectiveness of the PI3K inhibitors (40, 41). Resistance to PI3K inhibitors in vivo may lead to persistent TRPC6 channel activity in the hypercholesterolemic female mice. Unfortunately, no assay is available to directly assess TRPC6 activity in vivo. Further investigation is warranted to explore this possibility.

In addition to higher average percent re-endothelialization, hypercholesterolemic female mice tended to have higher variability between individual mice (Table 3), as indicated by larger standard deviation in most of the study groups, as compared with male mice (Table 2). This higher variability may be related to variation in estrogen levels depending on timing of the carotid injury relative to the estrous cycle of the mouse. The plasma concentration of estradiol levels in virgin mice ranges from a mean of 20 pg/mL to greater than 40 pg/mL across the four stages of the estrous cycle (42). The trend toward increased baseline healing and higher variability in the hypercholesterolemic female mice may have led to the study being underpowered with regard to the female mice alone. The power analysis for the current animal studies was based on our prior studies comparing normocholesterolemic and hypercholesterolemic male mice only, as our previous studies did not include female mice (10, 28, 43). Future studies will need to account for these differences in the research design.

This study indicates a potential new role for isoform-specific PI3K inhibitors, which are used clinically in the treatment of cancer, to pharmacologically block TRPC6 externalization induced by lipid oxidation products. Importantly, this provides a novel approach to promote EC migration and improve arterial healing in male patients after arterial injury such as angioplasty or implantation of intravascular devices while minimizing the impact on alternative PI3K signaling pathways. This study also identifies for the first-time significant sex differences in the response to PI3K inhibition in the cardiovascular system, where female sex generally has a cardioprotective effect. This study provides a foundation for future studies of the signaling pathway involved in lysoPC-induced TRPC6 externalization and develop a more generalizable treatment option to improve arterial healing, limit restenosis, and reduce the need for reintervention.

SUPPLEMENTAL DATA

Supplemental Fig. S1: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.13369061.v1.

GRANTS

This project was supported by Career Development Award IK2BX003628 from the US Department of Veterans Affairs Biomedical Laboratory Research and Development Service and National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grant HL064357 from the National Institutes of Health (NIH/NHLBI).

DISCLAIMERS

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not represent the views of the US Department of Veterans Affairs, the NIH, the NHLBI, or the US Government.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

P.C., A.H.S., L.M.G., and M.A.R. conceived and designed research; P.C. and M.A.R. performed experiments; P.C., A.H.S., L.M.G., and M.A.R. analyzed data; P.C., A.H.S., L.M.G., and M.A.R. interpreted results of experiments; P.C. and M.A.R. prepared figures; M.A.R. drafted manuscript; P.C., A.H.S., L.M.G., and M.A.R. edited and revised manuscript; P.C., A.H.S., L.M.G., and M.A.R. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank the Director of the Cleveland Clinic Lerner Research Institute Flow Cytometry Core facility, Dr. Kewal Asosingh, and technologist, Amy Graham, for invaluable assistance with the calcium studies and with analysis of the calcium data.

REFERENCES

- 1.Jim J, Owens PL, Sanchez LA, Rubin BG. Population-based analysis of inpatient vascular procedures and predicting future workload and implications for training. J Vasc Surg 55: 1394–1399, 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2011.11.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Farb A, Burke AP, Kolodgie FD, Virmani R. Pathological mechanisms of fatal late coronary stent thrombosis in humans. Circulation 108: 1701–1706, 2003. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000091115.05480.B0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tanous D, Bräsen JH, Choy K, Wu BJ, Kathir K, Lau A, Celermajer DS, Stocker R. Probucol inhibits in-stent thrombosis and neointimal hyperplasia by promoting re-endothelialization. Atherosclerosis 189: 342–349, 2006. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2006.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haudenschild CC, Schwartz SM. Endothelial regeneration. II. Restitution of endothelial continuity. Lab Invest 41: 407–418, 1979. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chaudhuri P, Colles SM, Damron DS, Graham LM. Lysophosphatidylcholine inhibits endothelial cell migration by increasing intracellular calcium and activating calpain. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 23: 218–223, 2003. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.0000052673.77316.01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Isshiki M, Ando J, Yamamoto K, Fujita T, Ying Y, Anderson RGW. Sites of Ca2+ wave initiation move with caveolae to the trailing edge of migrating cells. J Cell Sci 115: 475–484, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chaudhuri P, Colles SM, Bhat M, Van Wagoner DR, Birnbaumer L, Graham LM. Elucidation of a TRPC6-TRPC5 channel cascade that restricts endothelial cell movement. Mol Biol Cell 19: 3203–3211, 2008. doi: 10.1091/mbc.e07-08-0765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yao X, Garland CJ. Recent developments in vascular endothelial cell transient receptor potential channels. Circ Res 97: 853–863, 2005. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000187473.85419.3e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dietrich A, Kalwa H, Fuchs B, Grimminger F, Weissmann N, Gudermann T. In vivo TRPC functions in the cardiopulmonary vasculature. Cell Calcium 42: 233–244, 2007. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2007.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rosenbaum MA, Chaudhuri P, Graham LM. Hypercholesterolemia inhibits reendothelialization of arterial injuries by TRPC channel activation. J Vasc Surg 62: 1040–1047, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2014.04.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chaudhuri P, Rosenbaum MA, Sinharoy P, Damron DS, Birnbaumer L, Graham LM. Membrane translocation of TRPC6 channels and endothelial migration are regulated by calmodulin and PI3 kinase activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 113: 2110–2115, 2016. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1600371113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morello F, Perino A, Hirsch E. Phosphoinositide 3-kinase signalling in the vascular system. Cardiovasc Res 82: 261–271, 2009. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvn325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bendell JC, Rodon J, Burris HA, de Jonge M, Verweij J, Birle D, Demanse D, De Buck SS, Ru QC, Peters M, Goldbrunner M, Baselga J. Phase I, dose-escalation study of BKM120, an oral pan-Class I PI3K inhibitor, in patients with advanced solid tumors. J Clin Oncol 30: 282–290, 2012. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.36.1360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carmeliet P, Moons L, Stassen JM, De MM, Bouché A, Van den Oord JJ, Kockx M, Collen D. Vascular wound healing and neointima formation induced by perivascular electric injury in mice. Am J Pathol 150: 761–776, 1997. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jean S, Kiger AA. Classes of phosphoinositide 3-kinases at a glance. J Cell Sci 127: 923–928, 2014. doi: 10.1242/jcs.093773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vanhaesebroeck B, Stephens L, Hawkins P. PI3K signalling: the path to discovery and understanding. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 13: 195–203, 2012. doi: 10.1038/nrm3290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chaudhuri P, Smith AH, Putta P, Graham LM, Rosenbaum MA. P110α and P110δ catalytic subunits of PI3 kinase regulate lysophosphatidylcholine-induced TRPC6 externalization. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. In press. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00425.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Janku F, Yap TA, Meric-Bernstam F. Targeting the PI3K pathway in cancer: are we making headway? Nat Rev Clin Oncol 15: 273–291, 2018. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2018.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fritsch C, Huang A, Chatenay-Rivauday C, Schnell C, Reddy A, Liu M, Kauffmann A, Guthy D, Erdmann D, De Pover A, Furet P, Gao H, Ferretti S, Wang Y, Trappe J, Brachmann SM, Maira SM, Wilson C, Boehm M, Garcia-Echeverria C, Chene P, Wiesmann M, Cozens R, Lehar J, Schlegel R, Caravatti G, Hofmann F, Sellers WR. Characterization of the novel and specific PI3Kalpha inhibitor NVP-BYL719 and development of the patient stratification strategy for clinical trials. Mol Cancer Ther 13: 1117–1129, 2014. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-13-0865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lannutti BJ, Meadows SA, Herman SE, Kashishian A, Steiner B, Johnson AJ, Byrd JC, Tyner JW, Loriaux MM, Deininger M, Druker BJ, Puri KD, Ulrich RG, Giese NA. CAL-101, a p110δ selective phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase inhibitor for the treatment of B-cell malignancies, inhibits PI3K signaling and cellular viability. Blood 117: 591–594, 2011. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-03-275305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maira SM, Pecchi S, Huang A, Burger M, Knapp M, Sterker D, Schnell C, Guthy D, Nagel T, Wiesmann M, Brachmann S, Fritsch C, Dorsch M, Chene P, Shoemaker K, De Pover A, Menezes D, Martiny-Baron G, Fabbro D, Wilson CJ, Schlegel R, Hofmann F, Garcia-Echeverria C, Sellers WR, Voliva CF. Identification and characterization of NVP-BKM120, an orally available pan-class I PI3-kinase inhibitor. Mol Cancer Ther 11: 317–328, 2012. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-11-0474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.O’Brien NA, McDonald K, Tong L, von Euw E, Kalous O, Conklin D, Hurvitz SA, di Tomaso E, Schnell C, Linnartz R, Finn RS, Hirawat S, Slamon DJ. Targeting PI3K/mTOR overcomes resistance to HER2-targeted therapy independent of feedback activation of AKT. Clin Cancer Res 20: 3507–3520, 2014. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-2769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tasian SK, Teachey DT, Li Y, Shen F, Harvey RC, Chen IM, Ryan T, Vincent TL, Willman CL, Perl AE, Hunger SP, Loh ML, Carroll M, Grupp SA. Potent efficacy of combined PI3K/mTOR and JAK or ABL inhibition in murine xenograft models of Ph-like acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood 129: 177–187, 2017. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-05-707653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alikhani N, Ferguson RD, Novosyadlyy R, Gallagher EJ, Scheinman EJ, Yakar S, LeRoith D. Mammary tumor growth and pulmonary metastasis are enhanced in a hyperlipidemic mouse model. Oncogene 32: 961–967, 2013. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chaudhuri P, Colles SM, Fox PL, Graham LM. Protein kinase Cδ-dependent phosphorylation of syndecan-4 regulates cell migration. Circ Res 97: 674–681, 2005. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000184667.82354.b1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.James A, Blumenstein L, Glaenzel U, Jin Y, Demailly A, Jakab A, Hansen R, Hazell K, Mehta A, Trandafir L, Swart P. Absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion of [14C]BYL719 (alpelisib) in healthy male volunteers. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 76: 751–760, 2015. doi: 10.1007/s00280-015-2842-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nair KS, Cheson B. The role of idelalisib in the treatment of relapsed and refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Ther Adv Hematol 7: 69–84, 2016. doi: 10.1177/2040620715625966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rosenbaum MA, Miyazaki K, Graham LM. Hypercholesterolemia and oxidative stress inhibit endothelial cell healing after arterial injury. J Vasc Surg 55: 489–496, 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2011.07.081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.D'Alessandro D, Neri E, Moscato S, Dolfi A, Bartolozzi C, Calderazzi A, Bianchi F. Immediate structural changes of porcine renal arteries after angioplasty: a histological and morphometric study. Micron 37: 255–261, 2006. doi: 10.1016/j.micron.2005.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rosenbaum MA, Miyazaki K, Colles SM, Graham LM. Antioxidant therapy reverses impaired graft healing in hypercholesterolemic rabbits. J Vasc Surg 51: 184–193, 2010. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2009.08.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kishimoto T, Soda Y, Matsuyama Y, Mizuno K. An enzymatic assay for lysophosphatidylcholine concentration in human serum and plasma. Clin Biochem 35: 411–416, 2002. doi: 10.1016/S0009-9120(02)00327-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kwon Y, Hofmann T, Montell C. Integration of phosphoinositide- and calmodulin-mediated regulation of TRPC6. Mol Cell 25: 491–503, 2007. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Monet M, Francoeur N, Boulay G. Involvement of phosphoinositide 3-kinase and PTEN protein in mechanism of activation of TRPC6 protein in vascular smooth muscle cells. J Biol Chem 287: 17672–17681, 2012. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.341354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tseng P-H, Lin H-P, Hu H, Wang C, Zhu MX, Chen C-S. The canonical transient receptor potential 6 channel as a putative phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate-sensitive calcium entry system. Biochemistry 43: 11701–11708, 2004. doi: 10.1021/bi049349f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Barrett-Connor E, Bush TL. Estrogen and coronary heart disease in women. JAMA 265: 1861–1867, 1991. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mendelsohn ME, Karas RH. Molecular and cellular basis of cardiovascular gender differences. Science 308: 1583–1587, 2005. doi: 10.1126/science.1112062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Guo X, Razandi M, Pedram A, Kassab G, Levin ER. Estrogen induces vascular wall dilation: mediation through kinase signaling to nitric oxide and estrogen receptors α and β. J Biol Chem 280: 19704–19710, 2005. doi: 10.1074/jbc.m501244200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu Z, Gou Y, Zhang H, Zuo H, Zhang H, Liu Z, Yao D. Estradiol improves cardiovascular function through up-regulation of SOD2 on vascular wall. Redox Biol 3: 88–99, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2014.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Serra V, Scaltriti M, Prudkin L, Eichhorn PJ, Ibrahim YH, Chandarlapaty S, Markman B, Rodriguez O, Guzman M, Rodriguez S, Gili M, Russillo M, Parra JL, Singh S, Arribas J, Rosen N, Baselga J. PI3K inhibition results in enhanced HER signaling and acquired ERK dependency in HER2-overexpressing breast cancer. Oncogene 30: 2547–2557, 2011. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Elkabets M, Vora S, Juric D, Morse N, Mino-Kenudson M, Muranen T, Tao J, Campos AB, Rodon J, Ibrahim YH, Serra V, Rodrik-Outmezguine V, Hazra S, Singh S, Kim P, Quadt C, Liu M, Huang A, Rosen N, Engelman JA, Scaltriti M, Baselga J. mTORC1 inhibition is required for sensitivity to PI3K p110α inhibitors in PIK3CA-mutant breast cancer. Sci Transl Med 5: 196ra99, 2013. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3005747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vora SR, Juric D, Kim N, Mino-Kenudson M, Huynh T, Costa C, Lockerman EL, Pollack SF, Liu M, Li X, Lehar J, Wiesmann M, Wartmann M, Chen Y, Cao ZA, Pinzon-Ortiz M, Kim S, Schlegel R, Huang A, Engelman JA. CDK 4/6 inhibitors sensitize PIK3CA mutant breast cancer to PI3K inhibitors. Cancer Cell 26: 136–149, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.05.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zenclussen ML, Casalis PA, Jensen F, Woidacki K, Zenclussen AC. Hormonal fluctuations during the estrous cycle modulate heme oxygenase-1 expression in the uterus. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 5: 32, 2014. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2014.00032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rosenbaum MA, Chaudhuri P, Abelson B, Cross BN, Graham LM. Apolipoprotein A-I mimetic peptide reverses impaired arterial healing after injury by reducing oxidative stress. Atherosclerosis 241: 709–715, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2015.06.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]