Key Points

Question

Does a single oral dose of azithromycin lead to absence of symptoms at day 14 in outpatients with COVID-19 compared with placebo?

Findings

In this randomized trial that included 263 participants with SARS-CoV-2 infection, treatment with a single oral dose of azithromycin, 1.2 g, vs placebo resulted in self-reported absence of COVID-19 symptoms at day 14 in 50% vs 50%; this was not statistically significant.

Meaning

Among outpatients with SARS-CoV-2 infection, treatment with a single dose of oral azithromycin compared with placebo did not result in a greater likelihood of being free of symptoms at day 14.

Abstract

Importance

Azithromycin has been hypothesized to have activity against SARS-CoV-2.

Objective

To determine whether oral azithromycin in outpatients with SARS-CoV-2 infection leads to absence of self-reported COVID-19 symptoms at day 14.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Randomized clinical trial of azithromycin vs matching placebo conducted from May 2020 through March 2021. Outpatients from the US were enrolled remotely via internet-based surveys and followed up for 21 days. Eligible participants had a positive SARS-CoV-2 diagnostic test result (nucleic acid amplification or antigen) within 7 days prior to enrollment, were aged 18 years or older, and were not hospitalized at the time of enrollment. Among 604 individuals screened, 297 were ineligible, 44 refused participation, and 263 were enrolled. Participants, investigators, and study staff were masked to treatment randomization.

Interventions

Participants were randomized in a 2:1 fashion to a single oral 1.2-g dose of azithromycin (n = 171) or matching placebo (n = 92).

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcome was absence of self-reported COVID-19 symptoms at day 14. There were 23 secondary clinical end points, including all-cause hospitalization at day 21.

Results

Among 263 participants who were randomized (median age, 43 years; 174 [66%] women; 57% non-Hispanic White and 29% Latinx/Hispanic), 76% completed the trial. The trial was terminated by the data and safety monitoring committee for futility after the interim analysis. At day 14, there was no significant difference in proportion of participants who were symptom free (azithromycin: 50%; placebo: 50%; prevalence difference, 0%; 95% CI, −14% to 15%; P > .99). Of 23 prespecified secondary clinical end points, 18 showed no significant difference. By day 21, 5 participants in the azithromycin group had been hospitalized compared with 0 in the placebo group (prevalence difference, 4%; 95% CI, −1% to 9%; P = .16).

Conclusions and Relevance

Among outpatients with SARS-CoV-2 infection, treatment with a single dose of azithromycin compared with placebo did not result in greater likelihood of being symptom free at day 14. These findings do not support the routine use of azithromycin for outpatient SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT04332107

This randomized trial assesses the effect of a single dose of azithromycin vs placebo on absence of COVID-19 symptoms at posttreatment day 14 among outpatients with SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Introduction

Azithromycin is a broad-spectrum azalide antibiotic that has anti-inflammatory and antiviral properties and that has been hypothesized to have activity against SARS-CoV-2.1 The anti-inflammatory effects of azithromycin may reduce cytokine levels that may help prevent progression to tissue damage and severe COVID-19, especially if administered early in the disease course.1 If found to be effective, azithromycin is inexpensive, widely available, and has an excellent safety profile and would be an attractive candidate for outpatient use. Alternatively, if found to be ineffective, its use should be curtailed to prevent the selection for macrolide resistance.2

Randomized clinical trials of hospitalized patients and in outpatients with presumed COVID-19 have failed to find evidence to support the use of azithromycin for COVID-19 treatment with or without the use of hydroxychloroquine.3,4,5,6 Comparing treatment with azithromycin without concurrent hydroxychloroquine vs placebo in patients with laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection could provide more definitive evidence of its efficacy for COVID-19. This randomized clinical trial of outpatients with documented recent SARS-CoV-2 infection evaluated whether a single oral dose of azithromycin was effective for prevention of progression of COVID-19 in outpatients.

Methods

Trial Design

The Azithromycin for COVID-19 Trial, Investigating Outpatients Nationwide (ACTION) study was a 2:1 randomized clinical trial evaluating the efficacy of a single oral 1.2-g dose of azithromycin compared with placebo on self-reported COVID-19 symptoms among outpatients throughout the US. Participants were recruited from May 22, 2020, through March 16, 2021. Follow-up was complete on March 31, 2021. The study was reviewed and approved by the institutional review boards at the University of California, San Francisco (protocol 20-30504) and Stanford University (protocol 56834) and was conducted under an Investigational New Drug application (No. 149526) from the US Food and Drug Administration. All participants completed an electronic written informed consent process in either English or Spanish. To complete the informed consent process, study staff reviewed the study with participants, reviewed the consent form, and answered any questions. If interested, participants digitally signed the informed consent document. The trial protocol and statistical analysis plan are available in Supplement 1.

Study Setting and Recruitment

Participants were recruited from across the US. The trial was advertised via traditional methods (eg, flyers in testing sites), letters mailed to patients who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 at the Stanford Clinical Virology Laboratory, and social media. Potential participants completed an online survey instrument that assessed their eligibility. Study staff attempted to contact each potential participant 3 times by telephone and once by email if unable to contact the participant by telephone. If a potential participant could not be contacted or was no longer in their eligible window from the date of their SARS-CoV-2 test, they were counted as “eligible but not enrolled.” If a participant was successfully contacted, they were provided with details on the study and sent an electronic copy of the informed consent document via email. Participants unable to complete the electronic informed consent were mailed a paper copy of the consent document. Participants filled out an online baseline survey and were mailed a study kit overnight, which consisted of the study medication and instructions. All documents were available in English and Spanish. Race and ethnicity were self-reported by participants based on fixed categories with the option to report an “other” race or ethnicity to comply with US Food and Drug Administration guidelines.

Eligibility Criteria

Participants were eligible for the trial if they had a documented positive SARS-CoV-2 test result (nucleic acid amplification or antigen) within 7 days before enrollment. If participants had multiple tests, the first positive test date was considered the date that they tested positive. Participants uploaded proof of SARS-CoV-2 positive test results during screening or emailed results directly to study staff. Participants were excluded if they were younger than 18 years, had a self-reported macrolide allergy, were concurrently taking hydroxychloroquine if they were older than 55 years (to reduce the potential risk of QT-interval prolongation), were concurrently taking nelfinavir or warfarin, were currently pregnant (self-report), or were unable to receive study drug in the mail or to complete online questionnaires. Participants were not required to be symptomatic to be eligible for the trial.

Randomization

Participants were randomized in a 2:1 ratio to azithromycin or matching placebo. Randomization was unrestricted (no blocking or stratification), and the sequence was generated by the study’s unmasked data team using a computer-generated pseudo-random number generator in R (R Foundation). A 2:1 allocation ratio was chosen to increase the probability that participants received the active study drug without compromising statistical power. The 2:1 allocation ratio led to approximately a 10% increase in overall sample size relative to a 1:1 allocation ratio.

Interventions and Masking

To facilitate masking and allocation concealment, letters were randomly assigned (eg, A, B, C; 6 letters total) to each study treatment (azithromycin or placebo). Study medication bottle labeling was identical with the exception of the treatment letter to allow for masking of investigators, study staff, and participants. Participants were randomly assigned to receive 1 of the 6 treatment letters and were sent a medication bottle labeled with that treatment letter. Only the study’s unmasked data team was aware of which treatment letters corresponded to azithromycin and placebo. After randomization, participants were sent a single oral 1.2-g dose of azithromycin suspension or matching placebo (Pfizer Inc) via overnight mail. The placebo was specifically formulated to match the azithromycin. Allocation was concealed by not revealing the letter randomly assigned to the participant until after enrollment and baseline assessments were complete.

In the event that a study participant’s treating physician thought it necessary for the safety of the participant to know whether they received azithromycin or placebo, an unmasked member of the study team directly contacted the treating physician to reveal this information. Treatment allocation information was divulged only at the request of a treating physician.

Outcomes

All prespecified primary and secondary clinical end points are reported herein (see Supplement 1 for full list of prespecified primary and secondary end points). The prespecified primary end point was self-reported absence of COVID-19 symptoms at day 14. Prespecified secondary end points included adverse events at day 3, hospitalization and/or death by day 21, emergency department and/or urgent care use by day 21, household members who were diagnosed with or developed symptoms of COVID-19 by day 21, and patient-reported COVID-19 symptoms at day 21 (including fever, cough, diarrhea, abdominal pain, anosmia, conjunctivitis, sore throat, shortness of breath, myalgia, fatigue, dizziness, and an open-ended “other” category). Laboratory end points will be reported in a separate article.

Outcome Assessment

Participants completed online surveys at days 3, 7, 14, and 21 after enrollment to assess outcomes. At day 3, participants were asked if they had experienced vomiting, nausea, diarrhea, rash, or abdominal pain since they took their study medication to assess possible adverse effects of the study medication. Participants were asked about symptoms at each time point. Participants were asked if they had stayed in a hospital setting (defined as in the emergency department or admitted to the hospital for ≥24 hours), if they had visited an emergency department or urgent care center, and if any household members had been diagnosed with or developed symptoms of COVID-19 since their last survey.

Protocol Changes

The original primary outcome for the trial was hospitalization. Prior to the first interim analysis, the proportion of participants who were hospitalized was substantially lower than 10% as assumed during the original trial design phase (Supplement 1). Given the lower risk of hospitalization and slower than anticipated enrollment, the principal investigators proposed to the data and safety monitoring committee (DSMC) on October 15, 2020, that the primary outcome be changed to absence of self-reported symptoms by the 14-day study visit, without unmasking treatment allocation or performing any data analysis. The DSMC approved this change on the same day. The study biostatistician reestimated the sample size for the new primary outcome (described in the Sample Size section), and a new interim monitoring schedule was proposed consisting of a single interim analysis when half of the new sample size target had been enrolled and reached their 14-day visit (described in the Interim Analysis section). The changes were implemented in the statistical analysis plan, in the manual of operations and procedures, and on ClinicalTrials.gov on December 15, 2020, prior to the interim analysis or to unmasking of treatment allocation.

Trial Oversight

The DSMC, consisting of experts in biostatistics, trial design, epidemiology, and infectious disease, oversaw the trial. The DSMC met 3 times during the course of the trial to review and approve the study design prior to the start of enrollment, to review proposed changes in the primary end point, and to review the results of the interim analysis. The study protocol stipulated that serious adverse events were to be reported to the study’s medical monitor, who subsequently determined if they were related to study participation. Any serious adverse event determined to be possibly related to study participation was to be reported to the DSMC in real time.

Sample Size

The original sample size estimation was based on the original primary outcome, hospitalization by day 14 (Supplement 1). The sample size target was revised after the change in the primary end point to absence of self-reported symptoms at day 14. Assuming 50% of participants would be symptom free at day 14, 20% loss to follow-up, and an α = .05, inclusion of 455 participants would provide approximately 80% power to detect an increase in the proportion of participants who were symptom free from 50% to 65% at day 14. At the time the trial was designed, there was little evidence to guide sample size assumptions. The 15% difference was chosen because it was judged to be a clinically meaningful difference, the sample size would be feasible to recruit, and the difference was consistent with clinical improvement at 14 days in an early trial of lopinavir-ritonavir and with assumptions for other ongoing trials of azithromycin for COVID-19.7,8

Interim Analysis

A single interim efficacy analysis after 50% of the target population was enrolled and had reached their day 14 end point was prespecified (at P = .001) using a Lan-DeMets α approach with an O’Brien-Fleming boundary.

Statistical Analysis

In the case of the trial being stopped for any reason, the prespecified final analysis would include all outcomes among participants who had been enrolled at the time the trial was stopped. Participants were analyzed according to their randomization group, and all participants with complete data at day 14 were included in the primary analysis. Methods for handling missing data in sensitivity analyses are described below. The primary analysis estimated the prevalence difference comparing the proportion of patients who were symptom free at 14 days in the azithromycin vs placebo groups. The prevalence ratio and corresponding 95% confidence intervals were estimated using a nonparametric bootstrap. P values for differences between groups were calculated using a permutation test with the prevalence difference between groups as the test statistic and 10 000 iterations. For the secondary end points of hospitalization, emergency department use, incident COVID-19 among other household members, and specific COVID-19 symptoms, the difference in prevalence between groups and the 95% confidence interval for the difference were estimated. P values were estimated for differences between groups as with the primary outcome. The proportion of participants experiencing each adverse event was calculated by treatment group.

A series of subgroup analyses for the primary end point were prespecified, including by age (>60 vs ≤60 years), presence of self-reported COVID-19 symptoms at enrollment vs asymptomatic at enrollment, and high risk vs low risk, with high risk defined as age 60 years or older and reported hypertension, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, or obstructive or restrictive lung disease at enrollment (Supplement 1). The presence of interaction on the additive scale was tested for using an interaction term between treatment group and each effect modifier in linear binomial models. Because all analyses were prespecified, no adjustments for multiple comparisons were made. All tests were 2-sided and an α < .05 was considered statistically significant. Because of the potential for type I error due to multiple comparisons, findings for analyses of secondary end points should be interpreted as exploratory.

A prespecified analysis to account for missing outcomes using inverse probability weighting was completed as a robustness check, assuming that the outcomes were missing at random (Supplement 1).9 As an additional robustness check, assuming that outcomes were missing not at random, a pattern-mixture model approach was used modeling absence of symptoms at day 14 with a linear probability model as a function of covariates listed for the inverse probability–weighted estimator. Missing outcomes were imputed using the model fit to predict, adding a shift parameter that varied across a range of values. All analyses were conducted in R version 4.0.2 (R Foundation).

Results

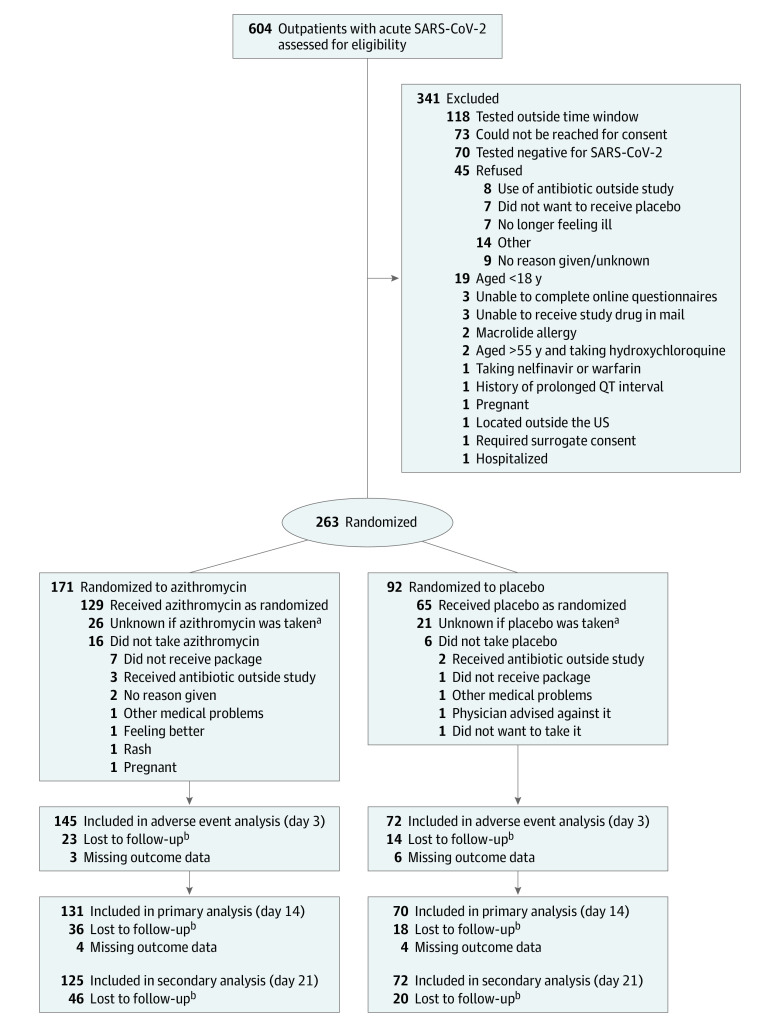

A total of 263 participants were enrolled, of whom 171 were randomized to azithromycin and 92 to placebo, with 76% completing the day 14 study visit (77% in the azithromycin group and 76% in the placebo group) (Figure; eTable 1 in Supplement 2). The percentage and distribution of baseline characteristics among participants completing the trial and who did and did not report taking the study medication were similar between groups (eTables 2-5 in Supplement 2). The median time from positive test result to enrollment in the study was 3 days (azithromycin: 3 days; placebo: 2 days) (Table 1). The median age of the study population was 43 years and 66% were female. The most commonly reported symptoms at baseline included cough (azithromycin: 65%; placebo: 66%), fatigue (azithromycin: 63%; placebo: 60%), and fever (azithromycin: 51%; placebo: 44%) (Table 1). Most participants reported multiple symptoms (azithromycin: 89%; placebo: 89%). Treatment allocation information was given to the treating physicians of 4 participants.

Figure. Flow of Participants in a Trial of Azithromycin for Treatment of SARS-CoV-2 Infection in Outpatients.

aDid not complete survey at day 3.

bLoss to follow-up numbers are cumulative.

Table 1. Baseline Participant Characteristics, Medications, and Symptoms.

| Characteristics | Azithromycin (n = 171) | Placebo (n = 92) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, median (IQR), y | 42 (35-49) | 44 (35-51) |

| Sex, No. (%) | n = 168 | n = 92 |

| Female | 117 (69) | 57 (62) |

| Male | 51 (30) | 35 (38) |

| Geographic region, No. (%)a | ||

| West | 79 (46) | 40 (44) |

| Southeast | 38 (22) | 14 (15) |

| Southwest | 24 (14) | 16 (17) |

| Midwest | 21 (12) | 16 (17) |

| Northeast | 9 (5) | 6 (7) |

| Race and ethnicity, No. (%)b | n = 167 | n = 92 |

| Non-Hispanic White | 94 (56) | 56 (61) |

| Latinx/Hispanic | 49 (29) | 27 (30) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 11 (7) | 1 (1) |

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 6 (4) | 3 (3) |

| Non-Hispanic Middle Eastern/Arab | 2 (1) | 1 (1) |

| Non-Hispanic Native American | 0 | 1 (1) |

| More than 1 race | 4 (2) | 3 (3) |

| Preferred not to answer | 1 (1) | 0 |

| Alcohol consumption >3 times per wk, No. (%)c | 23 (14) | 9 (10) |

| Current use, No. (%) | ||

| Cigarettes | 13 (8) | 5 (5) |

| Marijuana | 9 (5) | 6 (7) |

| e-Cigarettes/vaping | 8 (5) | 2 (2) |

| Cigars | 1 (1) | 1 (1) |

| Comorbidities, No. (%)d | ||

| Asthma | 21 (12) | 11 (12) |

| Hypertension | 20 (12) | 12 (13) |

| Diabetes | 5 (3) | 5 (5) |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 4 (2) | 0 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 1 (1) | 1 (1) |

| Cancer | 1 (1) | 0 |

| Stroke | 1 (1) | 1 (1) |

| Recent macrolide use (<30 d), No. (%) | 22 (13) | 11 (12) |

| Recent hydroxychloroquine use (<7 d), No. (%) | 1 (1) | 0 |

| Current medications, No. (%)e | ||

| ACEI or ARB | 15 (9) | 14 (15) |

| Metformin | 4 (2) | 3 (3) |

| Omeprazole | 1 (1) | 1 (1) |

| Tacrolimus | 1 (1) | 0 |

| Current vitamin/supplement use, No. (%)f | ||

| Vitamin D | 64 (37) | 37 (40) |

| Vitamin C | 61 (36) | 33 (36) |

| Multivitamin | 52 (30) | 27 (29) |

| Zinc | 49 (29) | 20 (22) |

| Omega-3 fatty acid | 14 (8) | 6 (7) |

| Self-reported symptoms, No. (%) | ||

| Multiple symptoms | 152 (89) | 82 (89) |

| Cough | 111 (65) | 61 (66) |

| Fatigue | 107 (63) | 55 (60) |

| Fever | 87 (51) | 40 (44) |

| Myalgia | 82 (48) | 40 (44) |

| Anosmia | 80 (47) | 39 (42) |

| Sore throat | 71 (42) | 37 (40) |

| Diarrhea | 45 (26) | 20 (22) |

| Shortness of breath | 45 (26) | 17 (19) |

| Dizziness | 39 (23) | 15 (16) |

| Abdominal pain | 29 (17) | 12 (13) |

| Conjunctivitis | 8 (5) | 2 (2) |

| None | 12 (7) | 6 (7) |

| No. of symptoms, median (IQR) | 5 (3-6) | 4 (3-6) |

| Duration of symptoms prior to test, median (IQR), d | 3 (2-4.5) | 3 (2-4) |

| Days between positive test result and enrollment, median (IQR) | 3 (1-5) | 2 (1-4) |

Abbreviations: ACEI, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; IQR, interquartile range.

West: Colorado, Montana, Washington, Utah, Nevada, California; Southwest: Texas, Oklahoma, New Mexico, Arizona; Midwest: Ohio, Indiana, Michigan, Illinois, Missouri, Wisconsin, Minnesota, Iowa, Kansas, Nebraska, South Dakota; Southeast: Virginia, Tennessee, North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, Alabama, Arkansas, Louisiana, Florida; Northeast: Connecticut, New York, Pennsylvania, New Jersey; states were divided into regions based on geographic and cultural similarities.

Race and ethnicity were self-reported and are shown for all participants who reported race and ethnicity information.

Alcohol consumption more than 3 times per week regardless of number of drinks.

Comorbidities were self-reported by participants.

Current medications were self-reported by participants. Participants were given a list of medications that were thought to be associated with COVID-19 progression at the time of the study design (March 2020) and were asked to check any that they were currently taking.

Current supplement use was self-reported by participants. Participants were given a list of vitamins and supplements thought to be associated with COVID-19 progression at the time of the study design (March 2020) and were asked to check any that they were currently taking.

The interim analysis population was reached on February 3, 2021. On review of the prespecified interim analysis, the DSMC requested an assessment of conditional power to inform recommendation about continuing the trial.10 This analysis yielded a conditional power of 17% assuming data for the remainder of the trial was consistent with a 15-percentage-point increase in proportion of patients with no self-reported symptoms in the azithromycin group vs the placebo group. Given the low conditional power and noting that recruitment was taking longer than originally anticipated, the DSMC recommended stopping for futility on March 16, 2021.

Primary Outcome

The proportion of participants reporting being symptom free at the day 14 study visit was not significantly different between groups (50% of participants in each group) (Table 2). This corresponded to a prevalence difference of 0% (95% CI, −14% to 15%; P > .99) and a prevalence ratio of 1.01 (95% CI, 0.76-1.39; P > .99).

Table 2. Participants With Absence of Symptoms at Day 14 by Randomized Treatment Group, Overall and in Prespecified Subgroups.

| Absence of symptoms at day 14, No./total (%) | Prevalence difference, % (95% CI) | Prevalence ratio (95% CI) | P valuea | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Azithromycin | Placebo | ||||

| All participants | 66/131 (50) | 35/70 (50) | 0 (−14 to 15) | 1.01 (0.76-1.39) | >.99 |

| By age, y | |||||

| ≤60 | 61/121 (50) | 31/62 (50) | 0 (−15 to 16) | .99 | |

| >60 | 5/10 (50) | 4/8 (50) | 0 (−46 to 46) | ||

| By baseline COVID-19 symptomsb | |||||

| Asymptomatic | 9/10 (90) | 3/4 (75) | 15 (−46 to 76) | .52 | |

| Symptomatic | 57/120 (48) | 32/66 (48) | −1 (−17 to 15) | ||

Permutation test P value, 10 000 replicates (primary analysis) or P value for interaction on the additive scale (subgroup analyses), estimated with a linear-binomial model.

A single participant in the azithromycin group did not have baseline symptom information.

Five participants were considered high risk by the prespecified definition, precluding subgroup analysis by risk stratification. Among individuals aged 60 years or younger, the prevalence difference was 0% (95% CI, −15% to 16%), and among individuals older than 60 years, the prevalence difference was 0% (95% CI, −46% to 46%), with no significant difference in estimates between groups (P > .99 for interaction) (Table 2). Similarly, there was no significant difference among asymptomatic (prevalence difference, 15%; 95% CI, −46% to 76%) compared with symptomatic participants (prevalence difference, −1%; 95% CI, −17% to 15%; P = .52 for interaction) (Table 2). Sensitivity analysis assuming data were missing at random using inverse probability weighting (prevalence difference, 0%; 95% CI, −15% to 15%) and data missing not at random (assuming a 4-fold reduction in odds of absence of symptoms at day 14 among those missing data, conditional on all other measured covariates, prevalence difference, 1%; 95% CI, −14% to 15%) were consistent with the primary outcome (eTable 6 in Supplement 2). Varying assumptions for the missing not at random analyses were consistent with the primary outcome (eTable 6).

Secondary Outcomes

By day 3, more participants reported gastrointestinal adverse events in the azithromycin group compared with placebo, including diarrhea (azithromycin: 41%; placebo: 17%), abdominal pain (azithromycin: 17%; placebo: 1%), and nausea (azithromycin: 22%; placebo: 10%) (Table 3). There were no significant differences in specific self-reported COVID-19 symptoms reported at day 14 (Table 4). No serious adverse events were reported, and there were no deaths in either study group. Among participants followed up through day 21, 5 reported having been hospitalized, all of whom were in the azithromycin group (Table 4). Reasons for hospitalization included difficulty breathing (n = 2), pneumonia (n = 1), low oxygen saturation (n = 1), and abdominal pain (n = 1). By day 21, emergency department/urgent care visits in the azithromycin group were significantly higher than in the placebo group (azithromycin: 14%; placebo: 3%; difference, 12%; 95% CI, 3%-20%; P = .01) (Table 4). There were no significant differences in the other 18 secondary outcomes (Table 4).

Table 3. Adverse Events by Randomized Study Group by Day 3 After Enrollmenta.

| Adverse events | No. (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Azithromycin (n = 145) | Placebo (n = 72) | |

| Diarrhea | 60 (41) | 12 (17) |

| Nausea | 32 (22) | 7 (10) |

| Abdominal pain | 25 (17) | 1 (1) |

| Vomiting | 5 (3) | 2 (3) |

| Rash | 4 (3) | 2 (3) |

| Otherb | 10 (7) | 3 (4) |

| ≥1 Adverse events | 82 (57) | 19 (26) |

| ≥2 Adverse events | 38 (26) | 5 (7) |

Adverse events were recorded at day 3 of the trial to capture recent events following treatment administration and to ensure that participants had received their study medication package and taken the medication before completing the survey.

Other adverse events were recorded in an open text field and included abdominal pain, stomach cramps and diarrhea, fever, light-headedness, hives, fatigue, cough, anosmia, and painful respiration.

Table 4. Secondary Outcomes by Randomized Study Group Through Day 21.

| Outcomes | No. (%) with outcome | Difference, % (95% CI) | P valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Azithromycin (n=125) | Placebo (n=72) | |||

| Incident outcomes by day 21 | ||||

| Participant hospitalized | 5 (4) | 0 | 4 (−1 to 9) | .16 |

| Participant emergency department or urgent care visit | 18 (14) | 2 (3) | 12 (3 to 20) | .01 |

| COVID-19 illness among other household membersb | 33/522 (6) | 20/278 (7) | −1 (−5 to 3) | .65 |

| Participant self-reported symptoms at day 21 | ||||

| Absence of symptoms | 71 (57) | 43 (60) | −3 (−18 to 12) | .77 |

| Fever | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | −1 (−4 to 3) | >.99 |

| Cough | 14 (11) | 13 (18) | −7 (−18 to 5) | .20 |

| Diarrhea | 4 (3) | 1 (1) | 2 (−3 to 7) | .65 |

| Abdominal pain | 0 | 1 (1) | −1 (−5 to 2) | .36 |

| Anosmia | 12 (10) | 9 (12) | −3 (−13 to 7) | .64 |

| Conjunctivitis | 2 (2) | 0 | 2 (−2 to 5) | .53 |

| Sore throat | 4 (3) | 4 (6) | −2 (−10 to 5) | .47 |

| Shortness of breath | 16 (13) | 4 (6) | 7 (−2 to 16) | .14 |

| Myalgia | 5 (4) | 3 (4) | 0 (−6 to 6) | >.99 |

| Fatigue | 32 (26) | 17 (24) | 2 (−12 to 16) | .86 |

| Dizziness | 6 (5) | 3 (4) | 1 (−6 to 7) | >.99 |

| Otherc | 10 (8) | 9 (12) | −4 (−15 to 6) | .33 |

Permutation test P value, 10 000 replicates.

Includes participants from 134 households in the azithromycin group and 69 households in the placebo group. The 95% CIs were estimated through bootstrap resampling households with replacement.

Other symptoms at day 21 were recorded in an open text field and included anosmia, nausea, headaches, difficulty focusing, forgetfulness/brain fog, headache, cold, rapid heartbeat, heaviness in chest/chest pressure, back pain, insomnia, night sweats, weakness, blurry vision, congestion, and rhinitis.

Discussion

In this randomized clinical trial of single-dose oral azithromycin for outpatient COVID-19, there was no significant difference in self-reported symptom absence 14 days after enrollment among participants randomized to azithromycin compared with placebo. These results build on those of previous randomized clinical trials of azithromycin for COVID-19 in both outpatient and inpatient settings, none of which have found a benefit of azithromycin for the treatment of COVID-19.3,4,5,6,11 In hospitalized patients, trials of azithromycin with or without hydroxychloroquine failed to find an effect of azithromycin on clinical outcomes or mortality, with no obvious safety signal.4,5,11 In outpatients and those with suspected COVID-19, azithromycin did not prevent progression to hospitalization or improve time to viral clearance of SARS-CoV-2 in nasal swabs.3,6 The present trial adds to the evidence against clinical benefit of azithromycin for COVID-19.

Most participants enrolled in this trial were symptomatic at baseline, and the distribution of symptoms mirrored other settings.12,13 Overall, participants in this study were young and had mild disease courses. Enrollment was not restricted based on symptoms, disease severity, or risk of progression to severe disease to evaluate if azithromycin was efficacious very early in COVID-19 before it had progressed. These results cannot be extrapolated to patients with more severe disease or those at higher risk of progression.

Exploratory secondary analyses evaluated clinical outcomes such as hospitalization and emergency department use and should be interpreted as hypothesis generating. Mild gastrointestinal adverse events following azithromycin administration are well established.14,15,16 Participants receiving azithromycin reported more gastrointestinal adverse events 3 days after treatment administration compared with placebo. All hospitalizations occurred in the azithromycin group, and there was more emergency department use in the azithromycin group compared with placebo. Most hospitalizations were due to respiratory issues, although 1 participant reported being hospitalized for severe abdominal pain. Additional research is needed to confirm these findings.

Overuse of antibiotics during the COVID-19 pandemic may lead to increased selection for antimicrobial resistance.17,18 Participants reporting recent macrolide use were not excluded; 12.5% of participants reported that they had used a macrolide within 30 days of enrollment. Antibiotic treatment is known to select for antimicrobial resistance.2,19,20,21 Widespread use of azithromycin for COVID-19 in the absence of a clear bacterial indication may contribute to resistance selection.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, although the trial was originally designed to evaluate prevention of hospitalization, due to a lower event rate than planned, the primary outcome was changed to symptom absence by day 14 prior to the first interim analysis. This study was underpowered for hospitalization end points. Second, a substantial proportion of participants reported not taking their allocated study medication or had missing adherence data. Nonadherence to the allocated study medication may have biased results toward the null. Third, loss to follow-up was higher than planned. The study was conducted remotely without any physical patient contact in order to reduce transmission risk, which may have facilitated loss to follow-up. Email, telephone, and next-of-kin information was collected from all participants. Multiple reminders were sent to complete surveys to mitigate loss to follow-up. Baseline characteristics for those retained and not retained after 14 days were similar, and sensitivity analyses accounting for missing outcomes did not change any conclusions of the study. If participants who were hospitalized or otherwise incapacitated were not followed up, hospitalization and other poor outcomes could be underestimated. Fourth, the time between receipt of a positive test result and enrollment in the study was a median 1 day longer among participants randomized to azithromycin compared with placebo. A longer time between positive test results and enrollment could mean that those participants were further along in their disease course and less likely to have persistent symptoms. Fifth, participants had to be able to complete online questionnaires and receive study materials at a physical location to participate in the trial, which may have selected for a younger and lower-risk population, limiting generalizability to those at increased risk of poor outcomes. However, given that azithromycin is routinely prescribed to patients with COVID-19 in lower-risk subgroups, broad inclusion may improve generalizability to lower-risk outpatient management.

Conclusions

Among outpatients with SARS-CoV-2 infection, treatment with a single dose of azithromycin compared with placebo did not result in greater likelihood of being symptom free at day 14. These findings do not support the routine use of azithromycin for outpatient SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Trial Protocol and Statistical Analysis Plan

eTable 1. Other Reasons for Refusing Study Participation

eTable 2. Baseline Characteristics, Medications, and Symptoms Among Those Who Were Retained at the Day 14 Timepoint

eTable 3. Baseline Characteristics, Medications, and Symptoms Among Those Who Were Not Retained at the Day 14 Timepoint

eTable 4. Baseline Characteristics, Medications, and Symptoms Among Those Who Were and Were Not Retained at the 14-Day Timepoint

eTable 5. Baseline Characteristics, Medications, and Symptoms Among Those Who Did and Did Not Report Taking Study Medication

eTable 6. Proportion of Participants Reporting Being Symptom Free at Day 14 by Randomized Treatment Group, Unadjusted and Accounting for Missing Outcome Data

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Oliver ME, Hinks TSC. Azithromycin in viral infections. Rev Med Virol. 2021;31(2):e2163. doi: 10.1002/rmv.2163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.O’Brien KS, Emerson P, Hooper PJ, et al. Antimicrobial resistance following mass azithromycin distribution for trachoma: a systematic review. Lancet Infect Dis. 2019;19(1):e14-e25. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(18)30444-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.PRINCIPLE Trial Collaborative Group . Azithromycin for community treatment of suspected COVID-19 in people at increased risk of an adverse clinical course in the UK (PRINCIPLE): a randomised, controlled, open-label, adaptive platform trial. Lancet. 2021;397(10279):1063-1074. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00461-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cavalcanti AB, Zampieri FG, Rosa RG, et al. ; Coalition Covid-19 Brazil I Investigators . Hydroxychloroquine with or without azithromycin in mild-to-moderate Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(21):2041-2052. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2019014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.RECOVERY Collaborative Group . Azithromycin in the treatment of patients admitted to the hospital with severe COVID-19: the COALITION II randomised clinical trial. Lancet. 2021;397(10274):605-612. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00149-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johnston C, Brown ER, Stewart J, et al. ; COVID-19 Early Treatment Study Team . Hydroxychloroquine with or without azithromycin for treatment of early SARS-CoV-2 infection among high-risk outpatient adults: a randomized clinical trial. EClinicalMedicine. 2021;33:100773. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.100773 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cao B, Wang Y, Wen D, et al. A trial of lopinavir-ritonavir in adults hospitalized with severe Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(19):1787-1799. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gyselinck I, Liesenborghs L, Landeloos E, et al. ; DAWn-Azithro Consortium . Direct antivirals working against the novel coronavirus: azithromycin (DAWn-AZITHRO), a randomized, multicenter, open-label, adaptive, proof-of-concept clinical trial of new antivirals working against SARS-CoV-2—azithromycin trial. Trials. 2021;22(1):126. doi: 10.1186/s13063-021-05033-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Little RJ, D’Agostino R, Cohen ML, et al. The prevention and treatment of missing data in clinical trials. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(14):1355-1360. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsr1203730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lachin JM. A review of methods for futility stopping based on conditional power. Stat Med. 2005;24(18):2747-2764. doi: 10.1002/sim.2151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.RECOVERY Collaborative Group . Azithromycin in patients admitted to hospital with COVID-19 (RECOVERY): a randomised, controlled, open-label, platform trial. Lancet. 2021;397(10274):605-612. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00149-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Spinato G, Fabbris C, Polesel J, et al. Alterations in smell or taste in mildly symptomatic outpatients with SARS-CoV-2 infection. JAMA. 2020;323(20):2089-2090. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.6771 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nehme M, Braillard O, Alcoba G, et al. ; COVICARE Team . COVID-19 symptoms: longitudinal evolution and persistence in outpatient settings. Ann Intern Med. 2021;174(5):723-725. doi: 10.7326/M20-5926 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sié A, Dah C, Bountogo M, et al. ; Gamin Study Group . Adverse events and clinic visits following a single dose of oral azithromycin among preschool children: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2020;104(3):1137-1141. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.20-1002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ayele B, Gebre T, House JI, et al. Adverse events after mass azithromycin treatments for trachoma in Ethiopia. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2011;85(2):291-294. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2011.11-0056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Astale T, Sata E, Zerihun M, et al. Self-reported side effects following mass administration of azithromycin to eliminate trachoma in Amhara, Ethiopia: results from a region-wide population-based survey. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2019;100(3):696-699. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.18-0781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Antimicrobial resistance in the age of COVID-19. Nat Microbiol. 2020;5(6):779. doi: 10.1038/s41564-020-0739-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Afshinnekoo E, Bhattacharya C, Burguete-García A, et al. ; MetaSUB Consortium . COVID-19 drug practices risk antimicrobial resistance evolution. Lancet Microbe. 2021;2(4):e135-e136. doi: 10.1016/S2666-5247(21)00039-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lipsitch M, Samore MH. Antimicrobial use and antimicrobial resistance: a population perspective. Emerg Infect Dis. 2002;8(4):347-354. doi: 10.3201/eid0804.010312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Doan T, Worden L, Hinterwirth A, et al. Macrolide and nonmacrolide resistance with mass azithromycin distribution. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(20):1941-1950. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oldenburg CE, Hinterwirth A, Sié A, et al. Gut resistome after oral antibiotics in preschool children in Burkina Faso: a randomized, controlled trial. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;70(3):525-527. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciz455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol and Statistical Analysis Plan

eTable 1. Other Reasons for Refusing Study Participation

eTable 2. Baseline Characteristics, Medications, and Symptoms Among Those Who Were Retained at the Day 14 Timepoint

eTable 3. Baseline Characteristics, Medications, and Symptoms Among Those Who Were Not Retained at the Day 14 Timepoint

eTable 4. Baseline Characteristics, Medications, and Symptoms Among Those Who Were and Were Not Retained at the 14-Day Timepoint

eTable 5. Baseline Characteristics, Medications, and Symptoms Among Those Who Did and Did Not Report Taking Study Medication

eTable 6. Proportion of Participants Reporting Being Symptom Free at Day 14 by Randomized Treatment Group, Unadjusted and Accounting for Missing Outcome Data

Data Sharing Statement