Significance

Metastasis remains the major cause of cancer-related deaths. Overactivation of receptor tyrosine kinase AXL has been correlated with cancer invasion and metastasis, resistance to therapies, and poor patient prognosis. However, the cellular processes activated by AXL and its ligand, GAS6, are largely unknown. Here, we identified a proximity interactome of AXL and revealed actin-dependent processes activated by GAS6-AXL, including membrane ruffling and macropinocytosis, that provide insights into the role of AXL in cancer progression. The identified AXL interactors can be used in translational research toward development of effective therapies for metastatic and/or chemoresistant cancers with AXL overactivation. Moreover, our data provide a mechanistic explanation for previous studies reporting that AXL might contribute to macropinocytic uptake of viruses.

Keywords: GAS6-AXL, TAM receptors, actin, membrane ruffles, macropinocytosis

Abstract

AXL, a member of the TAM (TYRO3, AXL, MER) receptor tyrosine kinase family, and its ligand, GAS6, are implicated in oncogenesis and metastasis of many cancer types. However, the exact cellular processes activated by GAS6-AXL remain largely unexplored. Here, we identified an interactome of AXL and revealed its associations with proteins regulating actin dynamics. Consistently, GAS6-mediated AXL activation triggered actin remodeling manifested by peripheral membrane ruffling and circular dorsal ruffles (CDRs). This further promoted macropinocytosis that mediated the internalization of GAS6-AXL complexes and sustained survival of glioblastoma cells grown under glutamine-deprived conditions. GAS6-induced CDRs contributed to focal adhesion turnover, cell spreading, and elongation. Consequently, AXL activation by GAS6 drove invasion of cancer cells in a spheroid model. All these processes required the kinase activity of AXL, but not TYRO3, and downstream activation of PI3K and RAC1. We propose that GAS6-AXL signaling induces multiple actin-driven cytoskeletal rearrangements that contribute to cancer-cell invasion.

Metastasis, the ability of cancer cells to spread from the primary tumor and invade distant secondary sites, makes cancer incurable. Despite much progress in oncology in the last decades, metastasis still causes ∼90% of cancer-related deaths. To initiate metastasis, cancer cells need first to disassemble cell–cell and cell–substrate adhesion sites and prepare for migration and invasion through the extracellular matrix (ECM), vessels, and tissues. This requires, among other things, a significant remodeling of the plasma membrane and actin cytoskeleton (1, 2).

During migration and invasion, cancer cells form various actin-based protrusions such as lamellipodia, filopodia, invadopodia, peripheral ruffles (PRs), and circular dorsal ruffles (CDRs) (3–5). CDRs are enigmatic actin-rich, ring-shaped structures formed transiently on the dorsal surface of cells in response to certain growth factors. To date, it was demonstrated that CDRs are formed upon stimulation with platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) in fibroblasts, hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) in HeLa and polarized epithelial Madin-Darby Canine Kidney (MDCK) cells, and epidermal growth factor (EGF) in fibroblasts and liver-derived epithelial cells (6–10). The functions of these structures are still not fully explored, but they have been postulated to play a role in the preparation of cells for motility, mesenchymal migration through ECM, and macropinocytosis (9). Additionally, CDRs have recently been proposed to amplify AKT activation (11).

Macropinocytosis is an evolutionarily conserved, actin-dependent form of endocytosis that mediates nonselective uptake of a large amount of extracellular fluid into cells. During macropinocytosis, PRs collapse inward to create large plasma membrane–derived vesicles, termed macropinosomes, which contain extracellular fluid and solutes (12, 13). Macropinosomes may also form concomitantly with the contraction and closure of CDRs (4). Generally, macropinocytosis allows rapid and efficient remodeling of the plasma membrane and its composition. Another proposed function of macropinocytosis is to support cellular metabolism, particularly of cancer cells in which macropinocytosis is constitutively activated by mutated RAS, PTEN, or PI3K (14–17). Up-regulated macropinocytosis enables cancer cells to acquire extracellular macromolecules which, upon lysosomal degradation, provide nutrients for the metabolism and cell growth. In this way, macropinocytosis allows cancer cells to survive in a nutrient-poor tumor microenvironment (14–20). Moreover, growth factor–induced macropinocytosis has been shown to increase cell growth and proliferation by the delivery of amino acids into endolysosomes that subsequently activate mTORC1 (21).

AXL is a receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) implicated in oncogenesis. Together with TYRO3 and MER, it belongs to the TAM family. TAM receptors are dispensable for embryonic development but participate in phagocytic clearance of apoptotic cells (efferocytosis) in adult organisms (22–25). Two known TAM ligands are vitamin K–dependent proteins: growth arrest–specific 6 (GAS6) and anticoagulant protein S (PROS1). GAS6 appears to bind all three TAMs, with the highest affinity for AXL, whereas PROS1 predominantly binds TYRO3 and MER (26, 27).

AXL is associated with the pathogenesis of a wide array of human cancers including gliomas, melanomas, breast, lung, and ovarian cancer (28–31). Overexpression of AXL and/or GAS6 has been shown to correlate with a poorer prognosis and increased cancer invasiveness—for example, in glioblastoma patients (32). Inhibition of AXL reduced glioma-cell migration, invasion, and proliferation in vitro and prolonged the survival of mice after intracerebral implantation of glioma cells (33, 34). An increased expression of AXL in highly metastatic breast cancer was found to be essential for all steps of the metastatic process, starting with intravasation of cancer cells (35, 36). Consistent with the association of AXL with cancer invasion and metastasis, a recent study by Revach et al. (37) reported that AXL may regulate the formation of invadopodia in melanoma cells. Furthermore, AXL has been linked to epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) that is associated with metastasis (36, 38, 39). Several studies showed that AXL activation associated with an EMT-like phenotype conferred resistance to both conventional and targeted anticancer therapies (28, 29). Thus, AXL inhibition constitutes a promising therapeutic strategy (28, 40). Accordingly, R428, a first-in-class AXL kinase inhibitor, is being tested in the second phase of clinical trials for metastatic lung and triple-negative breast cancer, glioblastoma, and acute myeloid leukemia (41, 42).

Despite the multiple roles of AXL in cancer invasion and metastasis, the molecular mechanisms underlying its action in cancer cells are not fully characterized. Here, we identified an interactome of AXL using a proximity-dependent biotin identification (BioID) assay. Our results reveal intracellular processes induced by GAS6-AXL signaling and mechanisms underlying GAS6-AXL–driven cell invasion.

Results

AXL Interacts with Proteins Implicated in the Regulation of Actin Cytoskeleton.

To determine the AXL interactome, we performed the BioID assay in human embryonic kidney 293 (HEK293) cells and human glioblastoma LN229 cells, which do not express and express AXL, respectively (SI Appendix, Fig. S1A). We selected HEK293 cells because they are widely used for the BioID assay (43, 44), whereas LN229 cells represent a cancer-relevant model to study AXL. To identify the proximity AXL interactome under both basal and ligand-stimulated conditions, we purified human GAS6 with a carboxyl-terminal Myc-His tag from culture supernatants of stably transfected HEK293 cells (SI Appendix, Fig. S1B). The purified GAS6-Myc-His (hereafter called GAS6) induced dose-dependent AXL phosphorylation in LN229 cells, indicating that the recombinant ligand was biologically active (SI Appendix, Fig. S1C). Next, to perform proximity labeling, we fused hemagglutinin (HA)-tagged, mutated biotin ligase (BirA-R118G-HA, denoted BirA*-HA) to the intracellular carboxyl-terminal part of AXL (AXL-BirA*-HA). Expression of fusion proteins BirA*-HA and AXL-BirA*-HA was verified in HEK293 cells (SI Appendix, Fig. S1D). The AXL-BirA*-HA fusion protein localized properly to the plasma membrane (SI Appendix, Fig. S1E) and displayed activation upon ligand stimulation (SI Appendix, Fig. S1F). Since these results confirmed the functionality of the AXL-BirA*-HA fusion, we generated HEK293 and LN229 cell lines stably expressing BirA*-HA or AXL-BirA*-HA (SI Appendix, Fig. S1 G and H).

These lines were incubated in the presence or absence of GAS6 and with biotin for 24 h, as this incubation time ensured efficient target biotinylation (SI Appendix, Fig. S1I), and purified biotinylated proteins were analyzed by mass spectrometry. Western-blot analysis of samples before (input) and after (output) streptavidin-mediated pull-down showed significant enrichment of biotinylated proteins in the output samples in comparison to the input (SI Appendix, Fig. S1 J and K).

The lists of proteins identified in cells expressing AXL-BirA*-HA protein (+/−GAS6) were compared to the ones found in control BirA*-HA–expressing cells. Proteins fulfilling the following criteria were considered as AXL proximity interactors: they were identified in at least two out of three experiments, with ≥2 peptides at least in one experiment and had three times higher the sum of Mascot scores in AXL-BirA*-HA samples in comparison to the control. We found 116 such proteins in nonstimulated and 151 proteins in GAS6-treated HEK293 cells, whereas we identified 114 and 147 proteins in nonstimulated and GAS6-treated LN229 cells, respectively (Datasets S1 and S2). Among interactors identified in HEK293 cells, 26 and 61 proteins were unique for nonstimulated and GAS6-stimulated conditions, respectively, whereas 90 proteins were common for both groups (SI Appendix, Fig. S1L). In the case of hits identified in LN229 cells, 21 proteins were uniquely found in nonstimulated samples, 54 proteins were unique for GAS6-stimulated samples, and 93 proteins were common (SI Appendix, Fig. S1L).

The Gene Ontology (GO) analysis of biological processes among the identified hits indicated enrichment of proteins implicated in cell junction organization, several actin-related processes, axonogenesis, supramolecular fiber organization, and angiogenesis in both nonstimulated and GAS6-stimulated samples. In GAS6-stimulated cells, AXL was found to interact also with proteins involved in receptor-mediated endocytosis and endosomal transport, positive regulation of GTPase activity, signaling, cell-substrate adhesion, and positive regulation of migration (Fig. 1 and SI Appendix, Fig. S2). Importantly, more proteins implicated in actin-related processes were found in GAS6-treated than in nonstimulated LN229 cells (Fig. 1). The GO analysis of molecular functions also showed enrichment of actin-binding proteins among AXL proximity interactors (SI Appendix, Fig. S2). Similarly, the GO analysis of cellular components identified proteins localizing to the cell leading edge and lamellipodium, which are actin-rich structures (SI Appendix, Fig. S2).

Fig. 1.

The BioID interactome analysis reveals that AXL is implicated in the regulation of the actin cytoskeleton. The GO analysis of biological processes for the BioID hits identified in LN229 cells is shown. NS: nonstimulated cells; GAS6: GAS6-stimulated cells.

Generally, the composition of the interactome of AXL, particularly upon GAS6 stimulation, points to the involvement of this receptor in the regulation of actin dynamics as one of its main functions in the cell.

GAS6 Triggers the Formation of PRs and CDRs.

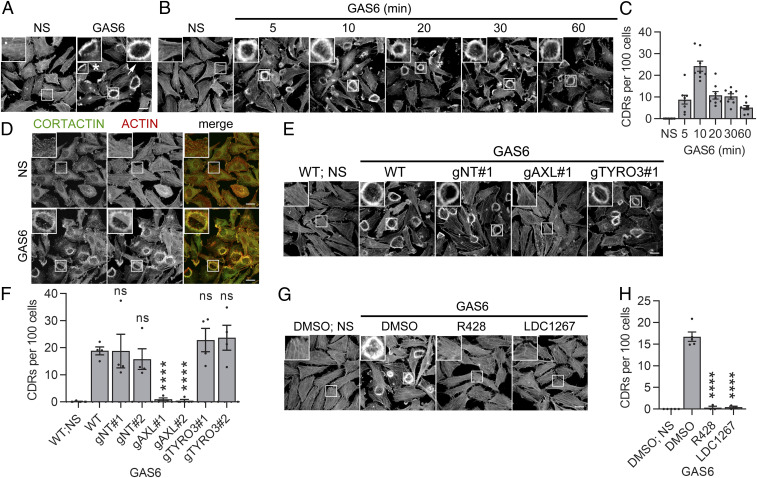

Taking into account the importance of actin-related processes for cancer-cell migration and invasion (45), we focused on a possible role of GAS6-AXL signaling in actin cytoskeleton remodeling. We found that AXL accumulated in cell regions enriched in actin, including lamellipodia, both in nonstimulated and GAS6-treated cells (SI Appendix, Fig. S3 A–E). Moreover, stimulation of LN229 cells with GAS6 triggered membrane ruffling manifested by the formation of PRs and CDRs (Fig. 2A). The maximal CDR formation occurred after 10 min of stimulation with GAS6 and subsided afterward (Fig. 2 B and C). CDR formation upon GAS6 stimulation was also confirmed in other AXL-expressing cancer-cell lines, lung A549 and breast MDA-MB-231 carcinoma (SI Appendix, Fig. S3F).

Fig. 2.

GAS6 induces the formation of CDRs, which depends on AXL and its kinase activity. (A) Formation of PRs (marked with asterisk) and CDRs (marked with arrow) in serum-starved LN229 cells stimulated with GAS6 for 10 min. (B) Kinetics of CDR formation in serum-starved LN229 cells stimulated with GAS6 for the indicated time periods. (C) Quantitation of the CDRs shown in B, n = 8. (D) Cortactin accumulation on CDRs upon stimulation of serum-starved LN229 cells with GAS6 for 10 min. (E) CDR formation upon knockout of AXL and TYRO3 in LN229 cells. Two guide RNAs (gRNAs) targeting AXL (gAXL#1 and gAXL#2) and TYRO3 (gTYRO3#1 and TYRO3#2) were used. Two nontargeting gRNAs (gNT#1 and gNT#2) served as controls. WT: wild-type LN229 cells. Serum-starved cells were stimulated with GAS6 for 10 min. (F) Quantification of data shown in E, n = 4. Student’s unpaired t test, ****P ≤ 0.0001; ns, nonsignificant (P > 0.05). (G) CDR formation upon AXL inhibitors. Serum-starved LN229 cells were pretreated for 30 min with R428 or LDC1267 followed by stimulation with GAS6 for 10 min. (H) Quantification of data shown in G; n ≥ 3, Student’s unpaired t test, ****P ≤ 0.0001. Insets in confocal images are magnified views of boxed regions in the main images. Actin was stained with phalloidin. (Scale bars, 20 μm.) For data quantification, ∼150 cells were counted per experiment, and each dot represents data from one independent experiment, whereas bars represent the means ± SEM from n experiments. NS: nonstimulated cells; GAS6: GAS6-stimulated cells.

In line with the observed GAS6-induced CDR formation, a more profound analysis of AXL proximity interactors revealed 23 proteins known to localize and/or contribute to the formation of CDRs (SI Appendix, Table S1). One of them was cortactin, a cytoplasmic actin-binding protein that is considered as one of the main CDR markers (46). Immunostaining of GAS6-stimulated LN229 cells confirmed that cortactin colocalized with actin on CDRs (Fig. 2D). Cumulatively, these data show that AXL is localized to actin-rich cell regions and that GAS6 stimulation rapidly induces the formation of cortactin-positive CDRs.

GAS6-Induced CDR Formation Depends on AXL and Its Kinase Activity.

GAS6 was described as a ligand for all three TAM receptors (26, 27). Since LN229 cells express AXL and TYRO3 (SI Appendix, Fig. S1A), we assessed the contribution of these receptors to GAS6-induced CDRs. To this end, we knocked out AXL and TYRO3 by the CRISPR-Cas9 method (SI Appendix, Fig. S3G) and tested GAS6-induced CDR formation in the generated knockout LN229 lines. We discovered that the knockout of AXL, but not TYRO3, inhibited GAS6-driven CDRs (Fig. 2 E and F). The same effects were observed when expression of AXL and TYRO3 was silenced by small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) (SI Appendix, Fig. S3 H–J).

To determine whether activation of the tyrosine kinase domain of AXL was required for the formation of GAS6-induced CDRs, we tested the effect of AXL inhibitors on the appearance of these actin structures. Treatment of LN229 cells with R428 or LCD1267 prior to stimulation with GAS6 prevented AXL phosphorylation and CDR formation (Fig. 2 G and H and SI Appendix, Fig. S3K). Altogether, these data indicate that the formation of CDRs upon GAS6 stimulation depends on AXL and its kinase activity.

PI3K Mediates GAS6-Induced CDR Formation Downstream of the GAS6-AXL.

AXL has been shown to trigger activation of several downstream signaling pathways such as PI3K-AKT, ERK, and PLC-γ (28). However, activation of a particular set of downstream effectors is often cell type specific. To verify which proteins are activated by GAS6-AXL signaling and can mediate GAS6-induced CDRs in glioblastoma cells, we assessed the phosphorylation status of different effectors in GAS6-stimulated LN229 cells using a phospho-kinase array (Fig. 3A and SI Appendix, Fig. S4A). GAS6 mainly triggered phosphorylation of AKT and its substrates such as GSK3-αβ, PRAS40, and WNK1 (47). This potent activation of AKT was also confirmed by Western blot (Fig. 3B and SI Appendix, Fig. S4B), but its pharmacological inhibition with MK-2206 had no effect on GAS6-induced CDR formation (SI Appendix, Fig. S4 C–E). AKT phosphorylation indicated that GAS6 might activate PI3K; thus, we checked whether pharmacological inhibition of PI3K activity affected GAS6-stimulated CDRs. Two inhibitors specific for class I PI3Ks, GDC-0941 and ZSTK474, prevented the GAS6-AXL–dependent formation of CDRs in LN229 cells (Fig. 3C and SI Appendix, Fig. S4 F and G). These results are in agreement with a previous report that PDGF-induced CDRs were blocked by inhibition of PI3K but not AKT (10).

Fig. 3.

PI3K mediates GAS6-induced CDR formation. (A) Phospho-kinase array showing activation of AKT and its substrates in serum-starved LN229 cells upon stimulation with GAS6 for 10 min. 1, AKT (S473); 2, AKT (T308); 3, GSK3-αβ (S21/S9); 4, PRAS40 (T246); 5, WNK1 (T60). Three paired spots in the corners are positive controls. (B) GAS6-induced phosphorylation of AXL (P-AXL, Y702) and AKT (P-AKT, S473). Serum-starved LN229 cells were stimulated with GAS6 for the indicated time periods. α-tubulin (α-tub.) served as a loading control. (C) CDR formation in GAS6-stimulated cells pretreated with PI3K inhibitors. Serum-starved LN229 cells were incubated with GDC-0941 or ZSTK474 for 30 min followed by incubation with GAS6 for 10 min, n = 3. Student’s unpaired t test, ***P ≤ 0.001. Corresponding confocal images are shown in SI Appendix, Fig. S4F. (D) Coimmunoprecipitates (Top) of anti-AXL (IP:AXL) and control antibodies (IP:IgG) from extracts of serum-starved LN229 cells stimulated with GAS6 for 2.5 and 5 min. Input (Bottom) represents 4% of the lysates used for IP. (E) Formation of GAS6-induced CDRs upon siRNA-mediated depletion of p85 isoforms. LN229 cells were transfected with combination of nontargeting siRNAs (siCTR#1+#2) or two combinations of siRNAs targeting p85-α and p85-β (sip85α#1+β#1 or sip85α#2+β#2). A total of 72 h after transfection, serum-starved cells were stimulated with GAS6 for 10 min, n = 3. Student’s unpaired t test, ***P ≤ 0.001, ****P ≤ 0.0001. Corresponding confocal images are shown in SI Appendix, Fig. S4H. (F) Formation of GAS6-induced CDRs upon overexpression of WT HRAS or its dominant negative mutant, HRAS S17N. Serum-starved LN229 cells stably expressing Ruby2-HRAS and Ruby2-HRAS S17N were stimulated with GAS6 for 10 min, n = 3. Student’s unpaired t test, ns: nonsignificant (P > 0.05), ***P ≤ 0.001. Corresponding confocal images are shown in SI Appendix, Fig. S4K. (G) Formation of GAS6-induced CDRs upon siRNA-mediated depletion of RAC1. LN229 cells were transfected with nontargeting siRNAs (siCTR#1) or siRNAs targeting RAC1 (siRAC1#1, siRAC1#2, or siRAC1#3). A total of 72 h after transfection, serum-starved cells were stimulated with GAS6 for 10 min, n = 3. Student’s unpaired t test, *P ≤ 0.05. Corresponding confocal images are shown in SI Appendix, Fig. S4L. For quantification of microscopic data, ∼150 cells were counted per experiment. In case of data shown in F, ∼50 cells expressing Ruby2-HRAS or Ruby2-HRAS S17N were counted per experiment. Each dot represents data from one independent experiment, whereas bars represent the means ± SEM from n experiments. NS: nonstimulated cells; GAS6: GAS6-stimulated cells.

We found two regulatory subunits of class IA PI3Ks, p85-α and p85-β, among AXL interactors only in GAS6-stimulated samples, which indicated that they were specifically associated with activated AXL (SI Appendix, Table S1 and Datasets S1 and S2). Using coimmunoprecipitation, we confirmed that p85 proteins bound AXL upon GAS6 stimulation (Fig. 3D). Both subunits have been recently described as downstream effectors of RAB35, and their knockout prevented the formation of PDGF-induced CDRs (10). Thus, to investigate their involvement in GAS6-AXL–driven CDR formation, we depleted both p85 isoforms by siRNA-mediated silencing. Knockdown of p85-α and -β inhibited CDR formation upon GAS6 stimulation (Fig. 3E and SI Appendix, Fig. S4 H and I). Cumulatively, these findings indicate that AXL stimulation by GAS6 induces mainly PI3K-AKT signaling, whereas GAS6-triggered formation of CDRs is specifically mediated by PI3K.

PI3K is one of the main effector pathways of RAS small GTPases that have been implicated in induction of CDRs (4, 48, 49). Consistent with this, we showed that GAS6 activated RAS (SI Appendix, Fig. S4J) and that expression of a dominant negative HRAS S17N mutant inhibited GAS6-induced CDRs (Fig. 3F and SI Appendix, Fig. S4K). Additionally, we verified the involvement of RAC, another small GTPase implicated in signaling downstream of RAS-PI3K that leads to CDR formation (4, 48). As shown in Fig. 3G and SI Appendix, Fig. S4 L and M, depletion of RAC1 blocked GAS6-triggered CDRs. Altogether, these data confirmed involvement of the RAS-PI3K-RAC axis in driving CDR formation downstream of GAS6-AXL.

GAS6-Induced PRs and CDRs Drive Macropinocytosis through which GAS6-AXL Complexes are Internalized.

It is well established that membrane ruffling promotes macropinocytosis, and both PRs and CDRs were postulated to initiate macropinosome formation (4, 50). Live imaging of GAS6-stimulated LN229 cells expressing a plasma membrane–tethered mCherry (MyrPalm-mCherry) showed that GAS6 stimulation triggered intense membrane ruffling and formation of large vesicles reminiscent of macropinosomes (Fig. 4A and Movies S1 and S2). We next asked whether GAS6-AXL complexes were internalized via the formed macropinosomes. Confocal imaging of cells immunostained for AXL and Myc-tagged GAS6 revealed that both the receptor and its ligand were present on the macropinosome membrane labeled by EEA1 and Rabankyrin-5 (Rank-5), markers of early endosomes and macropinosomes (51), respectively (Fig. 4 B and C). AXL was specifically enriched on the macropinosome membrane, in contrast to another plasma-membrane protein such as N-cadherin (Fig. 4 D and E). We further confirmed that AXL-positive macropinosomes colocalized with high-molecular-mass dextran, a known cargo of macropinocytosis (52, 53) (Fig. 4F). Moreover, AXL-positive macropinosomes were formed also in other cancer-cell lines such as A549, MDA-MB-231, and ovarian cancer SKOV3 cells (SI Appendix, Fig. S5 A–C). Altogether, these data indicate that GAS6 triggers membrane ruffling that drives internalization of GAS6-AXL complexes via macropinocytosis.

Fig. 4.

GAS6-induced membrane ruffing drives macropinocytosis through which GAS6-AXL complexes are internalized. (A) Live-cell time-lapse images of LN229 cells showing the formation of macropinosomes upon GAS6 stimulation. Serum-starved cells expressing the plasma membrane tethered mCherry were imaged for 5 min before and 30 min after addition of GAS6 by spinning disk confocal microscopy. Representative frames (0 to 30 min of GAS6 stimulation) from Movie S1 are shown. (B, C) GAS6-stimulated LN229 cells showing GAS6 and AXL on macropinosomes marked by EEA1 (B) and Rabankyrin-5 (Rank-5, C). Serum-starved cells were stimulated with GAS6 for 10 min. (D) GAS6-induced AXL-positive macropinosome in LN229 cells. Serum-starved cells were stimulated with GAS6 for 10 min. (E) Fluorescence intensity (FI) profiles along the yellow line shown in D. A representative profile is shown. (F) Colocalization of GAS6-induced AXL-positive macropinosomes with a high molecular mass dextran. Serum-starved LN229 cells expressing AXL-EGFP (AXL) were incubated with fluorescently labeled dextran in the presence or absence of GAS6 for 10 min. Insets in confocal images are magnified views of boxed regions in the main images. (Scale bars, 20 μm.) NS: nonstimulated cells: GAS6: GAS6-stimulated cells.

Although it has been reported that macropinosomes can be formed upon closure of CDRs, some findings suggest that PRs, but not CDRs, are necessary and sufficient for macropinocytosis (54). Thus, to test the involvement of GAS6-induced CDRs in macropinosome formation, we performed live imaging of GAS6-stimulated LN229 cells expressing mCherry to label the plasma membrane, together with LifeAct-mNeonGreen that stained filamentous actin (F-actin). This dual-color live-cell imaging confirmed that CDRs formed upon GAS6 stimulation were large, dynamic, and transient actin structures (SI Appendix, Fig. S5D and Movies S3 and S4). It further revealed that some macropinosomes were indeed formed upon closure of CDRs (SI Appendix, Fig. S5D and Movies S3 and S4). However, although GAS6 triggered the appearance of AXL-positive macropinosomes in SKOV3 cells, we did not observe the formation of CDRs in these cells (SI Appendix, Fig. S5C).

GAS6-Induced Macropinocytic Internalization Depends on AXL and Downstream Activation of PI3K and RAC1.

To determine whether GAS6 stimulates macropinocytic internalization of a model cargo, we measured uptake of a high-molecular-mass dextran (52, 53). Immunofluorescence analysis showed that fluorescently labeled dextran was internalized into large vesicular structures in LN229 cells within 10 min of GAS6 stimulation (Fig. 5 A and B). In parallel, measurements of dextran uptake by flow cytometry confirmed an increase in dextran internalization upon GAS6 stimulation (Fig. 5 C–F and SI Appendix, Fig. S6). GAS6-induced dextran uptake was completely inhibited by a macropinocytosis inhibitor 5-(N-ethyl-N-isopropyl)amiloride (EIPA) (55) (Fig. 5C and SI Appendix, Fig. S6B). Next, we checked whether kinase activity of AXL was needed for the observed GAS6-stimulated macropinocytic internalization of dextran. As shown in Fig. 5C and SI Appendix, Fig. S6B, incubation of cells with AXL inhibitors, R428 and LDC1267, prior to GAS6 stimulation completely blocked GAS6-induced uptake of dextran. This indicates that activation of the kinase domain of AXL is required for GAS6-driven macropinocytosis, similar to GAS6-induced CDR formation. Moreover, siRNA-mediated depletion of AXL, but not of TYRO3, completely inhibited GAS6-stimulated macropinocytic dextran internalization (Fig. 5D and SI Appendix, Fig. S6 C and D). These data clearly demonstrate that, although LN229 cells express two TAM receptors, AXL and TYRO3, GAS6-activated macropinocytic uptake of dextran depends specifically on AXL.

Fig. 5.

GAS6 induces macropinocytic internalization of dextran, which depends on AXL and downstream PI3K and RAC1 activation. (A) Internalization of fluorescently labeled dextran into large vesicular structures following stimulation with GAS6. Serum-starved LN229 cells were incubated with GAS6 and dextran for 10 min, fixed, and stained with DAPI to visualize the nuclei. (B) Analysis of integral fluorescence intensity of dextran-positive vesicles (expressed in arbitrary units, AU) shown in A, n = 5. Student’s unpaired t test, **P ≤ 0.01. (C–F) GAS6-induced macropinocytic uptake of dextran upon macropinocytosis (EIPA) and AXL (R428 and LDC1267) inhibitors (C), siRNA-mediated depletion of AXL or TYRO3 (D), PI3K inhibitors (GDC-0941 and ZSTK474) (E), and CRISPR-Cas9–mediated knockout of RAC1 (F) in LN229 cells. For experiments with inhibitors, serum-starved cells were incubated for 30 min with the indicated inhibitor prior to GAS6 stimulation. For siRNA-mediated depletion, two nontargeting siRNAs (siCTR#1 and siCTR#2), three siRNAs against AXL (siAXL#1, siAXL#2, siAXL#3), and three siRNAs against TYRO3 (siTYRO3#1, siTYRO3#2, siTYRO3#3) were used. For CRISPR-Cas9–mediated knockout, two different gRNAs targeting RAC1 (gRAC1#1 and gRAC1#2) were used. Cells were stimulated with GAS6 for 2 min, then fluorescent dextran was added, and cells were incubated for an additional 20 min. The fluorescence of internalized dextran was measured by flow cytometry, n = 3. (G) Proliferation of WT and AXL knockout (KO) LN229 cells incubated in medium with normal (2 mM Q) or subphysiological (0.2 mM Q) glutamine concentration in the absence or presence of 2% BSA. AXL KO cells were generated using gAXL#2. The medium was replaced every 24 h, and cell proliferation was measured after 6 d using an ATPlite assay. Data are presented relative to the values obtained for LN229 cells grown in 0.2 mM Q. Student’s unpaired or one sample (gray stars) t test **P ≤ 0.01. Insets in confocal images are magnified views of boxed regions in the main images. (Scale bars, 20 μm.) For quantification of microscopic data, ∼150 cells were counted per experiment. Each dot represents data from one independent experiment, whereas bars represent the means ± SEM from n experiments. Dashed lines show median fluorescence of dextran taken up by nonstimulated cells. NS: nonstimulated cells: GAS6: GAS6-stimulated cells.

PI3K-generated PI(3,4,5)P3 has been shown to play an important role during macropinocytosis (56). Since PI3K is the main downstream signaling pathway activated by GAS6-AXL in LN229 cells, we assessed the impact of pharmacological inhibition of PI3K on GAS6-stimulated macropinocytic dextran internalization. We found that the incubation of LN229 cells with PI3K inhibitors GDC-0941 and ZSTK474 prior to GAS6 stimulation blocked GAS6-induced uptake of dextran (Fig. 5E and SI Appendix, Fig. S6E). Additionally, CRISPR-Cas9–mediated knockout of RAC1, a key downstream effector of PI3K in actin remodeling, completely blocked GAS6-induced dextran internalization (Fig. 5F and SI Appendix, Fig. S6 F and G). Cumulatively, these findings indicate that, similarly to CDR formation, GAS6-induced macropinocytosis depends on AXL and its kinase activity as well as downstream activation of PI3K-RAC1 but not on a related TAM receptor, TYRO3. These data are consistent with a study by King et al. (57) published during the revision of our manuscript, showing that AXL activation induces macropinocytosis in a PI3K-dependent manner in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDA) cells.

AXL-Activated Macropinocytosis of Albumin Partly Rescues Growth of Glioblastoma Cells in Subphysiological Concentrations of Glutamine.

It was demonstrated that RAS-transformed pancreatic cancer cells acquire glutamine via the lysosomal degradation of exogenously provided albumin internalized through macropinocytosis, which allows them to survive and proliferate in the absence of this amino acid (14). Thus, we hypothesized that GAS6-AXL–induced macropinocytosis of albumin could similarly promote survival of glioblastoma LN229 cells. To verify this possibility, we examined whether proliferation of LN229 cells was affected by glutamine deprivation and whether this effect could be reversed by culturing cells in media supplemented with 2% bovine serum albumin (BSA). To avoid growth arrest and to reproduce conditions used previously by others (14), experiments with glutamine deprivation were done in the presence of 10% dialyzed serum (in contrast to standard GAS6 stimulations in our study performed in the absence of serum). Since GAS6 is present in serum (58), to estimate the contribution of AXL to cell growth, we tested both wild-type (WT) and AXL knockout LN229 cells. As shown in Fig. 5G, proliferation of LN229 cells was significantly inhibited under a subphysiological glutamine concentration (0.2 mM Q), and the addition of BSA improved over twofold the growth of cells cultured under glutamine deprivation. Moreover, the survival of AXL knockout cells in BSA-supplemented media was lower than the WT cells, indicating that AXL contributes to the observed albumin-mediated improvement in cell viability (Fig. 5G). Thus, our results suggest that AXL-dependent macropinocytosis allows exploiting exogenous albumin to improve survival of LN229 cells under conditions of glutamine deprivation, in agreement with the similar findings of King et al. (57) in PDA cells.

GAS6-AXL–Induced CDRs Accumulate Components of Focal Adhesions.

In addition to macropinocytosis, another postulated function of CDRs is the remodeling of cellular components in preparation for migration that requires disassembly of adhesion sites. In this regard, integrins were shown to be rapidly and transiently redistributed to CDRs upon focal adhesion (FA) disassembly during cell migration stimulated by growth factors (59). Given this, we tested the localization of integrin β-1 in GAS6-stimulated LN229 cells, which were seeded on fibronectin-coated coverslips. We observed accumulation of integrin β-1 on GAS6-induced CDRs (Fig. 6A) along with other FA components such as vinculin, talin, and paxillin (Fig. 6 B–D).

Fig. 6.

GAS6-AXL–induced CDRs trigger disassembly of FAs via transient accumulation of their components. (A–D) Accumulation of integrin β-1 (A), vinculin (B), talin (C), and paxillin (D) on GAS6-induced CDRs. Serum-starved LN229 cells were stimulated with GAS6 for 10 min. (E) Accumulation of vinculin, but not AXL, on GAS6-induced CDRs. Serum-starved LN229 cells were stimulated with GAS6 for 10 min. (F, G) Number (F) and average area (G) of FAs in serum-starved LN229 cells upon stimulation with GAS6 for 10 min. The number and the area of FAs per cell were counted using ImageJ software for 15 nonstimulated and 15 GAS6-stimulated cells without (w/o) CDRs and 15 GAS6-stimulated cells with (w/) CDRs from three independent experiments, n = 45. Mann–Whitney U test, ****P ≤ 0.0001, ns: nonsignificant (P > 0.05). Corresponding confocal images are shown in SI Appendix, Fig. S7N. (H) Spreading of WT and AXL knockout (KO) LN229 cells following GAS6 stimulation for 30 min. Cell area was measured using ImageJ software for 50 nonstimulated and 50 GAS6-stimulated cells from two independent experiments, n = 100. Mann–Whitney U test, ****P ≤ 0.0001; ns, nonsignificant (P > 0.05). Corresponding confocal images are shown in SI Appendix, Fig. S7O. (I) Cell elongation index of serum-starved LN229 cells upon stimulation with GAS6 for 10 min. The cell-elongation index (the ratio between the major axis and the minor axis) was measured using ImageJ software for 50 nonstimulated and 50 GAS6-stimulated, CDR-containing cells from two independent experiments, n = 100. Mann–Whitney U test, ****P ≤ 0.0001. Corresponding confocal images are shown in SI Appendix, Fig. S7P. Insets in confocal images are magnified views of boxed regions in the main images. (Scale bars, 20 μm.) NS: nonstimulated cells: GAS6: GAS6-stimulated cells. Each data point represents a value for a single cell; horizontal lines are means ± SEM for n cells.

Our GO analysis of cellular components among the identified AXL interactors revealed enrichment of proteins localized to FAs, including those FA components that were accumulated on GAS6-induced CDRs (SI Appendix, Fig. S2 and Datasets S1 and S2). Despite the biochemical detection of many FA components in close proximity to AXL in the BioID assay, we did not observe evident accumulation of AXL on FAs independently of the presence or absence of serum or GAS6 (Fig. 6E and SI Appendix, Fig. S7 A–E). In turn, AXL was present on PRs but not on fully enclosed CDRs formed upon GAS6 stimulation for 10 min (Fig. 6E and SI Appendix, Fig. S7 F–I). However, we observed accumulation of AXL together with vinculin on lamellipodia, which are sites of new FA formation (60) (SI Appendix, Fig. S7 A and J–M). Altogether, these findings revealed that GAS6-driven CDRs concentrate FA components, suggesting that they may be involved in turnover of existing FAs.

GAS6-AXL–Induced CDRs Are Involved in FA Disassembly.

To test whether GAS6-induced CDRs affected FA dynamics, we quantified the number and area of these adhesion structures in nonstimulated and GAS6-stimulated cells exhibiting CDRs. As shown in Fig. 6F and SI Appendix, Fig. S7N, GAS6-stimulated LN229 cells with CDRs contained considerably fewer FAs in comparison to nonstimulated cells and GAS6-stimulated LN229 cells without CDRs. Consistent with this, the average FA area was also significantly decreased in GAS6-stimulated LN229 cells with CDRs in comparison to both nonstimulated cells and GAS6-stimulated LN229 cells without CDRs (Fig. 6G). These observations suggested that GAS6-induced CDRs might lead to FA disassembly through transient accumulation of FA components. Since, during attachment to the ECM substrate, cell spreading requires continuous formation and disassembly of FAs (61), we assessed the impact of GAS6 stimulation on LN229 cells plated on fibronectin. As shown in Fig. 6H, GAS6-stimulated LN229 cells spread better in comparison to nonstimulated cells. Moreover, this GAS6-dependent increase in cell spreading was reduced in AXL knockout cells (Fig. 6H and SI Appendix, Fig. S7O).

Finally, we calculated a cell elongation index (the ratio between the major and minor axis of the cell, SI Appendix, Fig. S7P), which directly correlates with mesenchymal migration, a specific mode of cell locomotion through the ECM, associated with CDR-dependent matrix invasion (4, 54, 62). We found that the cell elongation index of GAS6-stimulated cells forming CDRs was significantly higher in comparison to nonstimulated cells (Fig. 6I and SI Appendix, Fig. S7P). Cumulatively, these observations allow us to conclude that GAS6-AXL–induced CDRs are implicated in FA turnover by concentration of FA components. They further suggest that CDRs might play a role in cell migration through the ECM. Notably, these conclusions are consistent with the data of Abu-Thuraia et al. (63), published during the revision of our manuscript.

The GAS6-AXL Pathway Induces Cell Invasion in a PI3K-Dependent Manner.

RAB35-dependent CDRs were proposed to act as a steering wheel for PDGF- and HGF-mediated chemotaxis and chemoinvasion (10). To check whether GAS6 is a chemotactic factor, we tested migration of LN229 cells through a membrane toward a GAS6 gradient in a Boyden chamber. We found that, in contrast to serum, GAS6 did not attract LN229 cells (SI Appendix, Fig. S8A). Since it was postulated that CDRs might correspond to invasive protrusions and play a role during three-dimensional invasion (4, 54), we tested the impact of GAS6 on invasion of cancer cells grown as spheroids. As shown in Fig. 7 A and B, GAS6 stimulated invasion of LN229 cells into Matrigel, and the same effect was also observed for MDA-MB-231 spheroids (SI Appendix, Fig. S8 B and C). Importantly, GAS6 did not enhance growth of LN229 spheroids cultured without Matrigel, indicating that the observed effect is due to GAS6-induced invasion (SI Appendix, Fig. S8 D and E). Similar to CDR formation and macropinocytosis, GAS6-stimulated invasion was inhibited by the CRISPR-Cas9–mediated inactivation of AXL but not of TYRO3 (Fig. 7 A and B). Moreover, invasion of LN229 cells was dependent on the kinase activity of AXL, as it was completely blocked by two AXL inhibitors, R428 and LDC1267 (Fig. 7C and SI Appendix, Fig. S8F).

Fig. 7.

GAS6-AXL signaling induces cell invasion in a PI3K-dependent manner. (A) GAS6-stimulated invasion of WT, AXL, or TYRO3 knockout (KO) LN229 cells. Two different gRNAs targeting AXL (gAXL#1 and gAXL#2) and TYRO3 (gTYRO3#1 and TYRO3#2) were used. Two different nontargeting gRNAs (gNT#1 and gNT#2) served as controls. (Scale bars, 500 μm.) (B) Quantification of data shown in A, n = 3. Student’s unpaired t test, **P ≤ 0.01, ***P ≤ 0.001, ns: nonsignificant (P > 0.05). (C and D) GAS6-induced invasion of LN229 spheroids after treatment with inhibitors of AXL (R428 or LDC1267) (C), PI3K (GDC-0941 and ZSTK474) (C), and knockout of RAC1 (D). For CRISPR-Cas9–mediated knockout of RAC1, two different gRNAs targeting RAC1 (gRAC1#1 and g RAC1#2) were used. Corresponding images are showed in SI Appendix, Fig. S8 F–H. Student’s unpaired t test, **P ≤ 0.01, ***P ≤ 0.001, ****P ≤ 0.0001. Spheroids embedded in Matrigel were incubated with GAS6 for 4 d. The area of spheroids was measured by ImageJ software. Data are expressed as fold changes of the spheroid area on the fourth day (DAY 4, D4) with respect to the spheroid area before Matrigel addition (DAY 0, D0). Each dot represents data from one independent experiment, whereas bars represent the means ± SEM from n experiments. NS: nonstimulated cells; GAS6: GAS6-stimulated cells.

Since a pharmacological inhibition of PI3K or CRISPR-Cas9–mediated knockout of RAC1 blocked both formation of CDRs and macropinocytosis following GAS6 stimulation (Fig. 3 C and G, Fig. 5 E and F), we assessed the impact of these perturbations on GAS6-induced invasion. We showed that PI3K inhibitors GDC-0941 and ZSTK474 (Fig. 7C and SI Appendix, Fig. S8G) or RAC1 knockout (Fig. 7D and SI Appendix, Fig. S8H) completely blocked GAS6-induced invasion of LN229 cells. GAS6-stimulated invasion was also blocked by the macropinocytosis inhibitor EIPA (SI Appendix, Fig. S8 I and J). This suggests that macropinocytosis may be involved in GAS6-AXL–induced invasion of cancer cells.

Collectively, these findings show that GAS6 induces cancer-cell invasion, which depends on AXL, the activity of its tyrosine kinase domain, and downstream activation of PI3K and RAC1 but not on its cognate TAM receptor TYRO3. Moreover, our data indicate that GAS6-induced CDRs and macropinocytosis may contribute to invasion triggered by the activation of GAS6-AXL signaling.

Discussion

AXL, a member of the TAM receptor family, and its ligand, GAS6, are associated with pathogenesis and metastasis of multiple cancers (28, 29). Despite active development of AXL inhibitors for clinical use in oncology, astonishingly little is known about its intracellular mechanisms of action. Here, we identified the interactome of AXL in HEK293 and glioblastoma LN229 cells and thereby found that GAS6-AXL regulates several actin-related processes that enhance an invasive phenotype of cancer cells. GAS6 triggered intense membrane ruffling, in the form of PRs and CDRs, and induced macropinocytosis. Furthermore, GAS6-induced CDRs promoted the turnover of FAs via accumulation of their components. Functionally, AXL activation by GAS6 culminated in increased invasion of cancer cells grown as spheroids. At the molecular level, we found that PI3K-AKT and RAS were activated downstream of GAS6-AXL stimulation. A pharmacological inhibition of PI3K or depletion of its regulatory subunits, p85-α and p85-β or its downstream effector RAC1 blocked CDR formation, macropinocytic internalization, and cell invasion induced by GAS6. Based on our results, we propose that GAS6-AXL signaling induces PI3K- and RAC1-dependent, actin-driven cytoskeletal rearrangements and macropinocytosis that jointly contribute to cancer-cell invasion (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8.

GAS6-AXL signaling induces actin remodeling that drives membrane ruffling, macropinocytosis, FA disassembly, and cancer-cell invasion. Upon GAS6 binding, AXL activates RAS and associates with two regulatory subunits of PI3K, p85-α and p85-β, that induce PI3K and RAC1. This triggers membrane ruffling, PRs and CDRs, that drives internalization of GAS6-AXL complexes via macropinocytosis. Macropinocytic uptake of extracellular proteins improves growth of cancer cells in a nutrient-poor environment. In parallel, GAS6-induced CDRs contribute to the disassembly of FAs through recruitment of their components, thus preparing cells for mesenchymal migration. Altogether, activation of AXL-PI3K-RAC1 signaling induces cancer-cell invasion.

There are two known ligands for the TAM receptors: GAS6 and PROS1. However, the specificity and biological relevance of their interaction with TAMs are not fully elucidated. It has been shown that, in addition to AXL, GAS6 can also activate two other TAMs, TYRO3 and MER (26, 27). Here, we discovered that depletion of AXL or pharmacological inhibition of its kinase activity completely inhibited GAS6-induced membrane ruffling, macropinocytosis, and invasion of LN229 cells grown as spheroids. In contrast, TYRO3, another TAM receptor expressed by LN229 cells, was dispensable for all these processes. Thus, our findings unequivocally demonstrate that AXL is a primary receptor for GAS6, at least in the glioblastoma model used.

Upon ligand binding, RTKs undergo endocytosis via different, often parallel, internalization pathways (64). Endocytosis is an important regulator of cellular signaling activated by RTKs that, if aberrant, contributes to RTK-associated tumorigenesis (65). However, AXL endocytosis has not been systematically investigated. Here, we discovered that, by inducing actin remodeling, GAS6 stimulation triggers macropinosome formation and that GAS6-AXL complexes localize to macropinosomes, indicating that a fraction of AXL is internalized via macropinocytosis. Thus, our data provide a mechanistic explanation for previous virology studies reporting that AXL might contribute to macropinocytic uptake of Lassa and Ebola viruses upon infection (66, 67). Importantly, AXL inhibitor R428 (Bemcentinib) has been proposed to inhibit SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus (COVID-19) entry into cells and is currently being tested for the treatment of COVID-19 patients under the ACCORD program (The Accelerating COVID-19 Research & Development Platform) (68).

There are different possible mechanisms by which macropinocytosis could contribute to GAS6-activated intracellular trafficking of AXL. For example, Chiasson-MacKenzie et al. (9) demonstrated that the deficiency of merlin, a cytoskeletal ERM-like protein, induced CDR formation and macropinocytosis that favored internalization of EGFR and its subsequent recycling. We found merlin among AXL proximity interactors. Thus, it is conceivable that GAS6-induced CDRs and macropinocytosis might depend on AXL-mediated phosphorylation of merlin that inhibits its function. A report indicated that CDRs may also constitute an endocytic mechanism of EGFR internalization (69). Here, we did not observe GAS6 or AXL accumulation on CDRs formed upon 10 min stimulation with GAS6. This indicates that, in contrast to EGFR, AXL does not undergo CDR-driven internalization. However, we noted accumulation of AXL with actin on the dorsal site of cells following 5 min stimulation with GAS6, occasionally seen also in the area of a forming CDR. This could suggest that AXL may be recruited to the site of CDR formation at the very beginning and displaced from CDRs at later stages of their formation. Altogether, our study provides foundational data about ligand-induced endocytic trafficking of AXL, a process that has not been previously studied for any of the TAM receptors.

Macropinosomes have been postulated to form concomitantly with the contraction and closure of CDRs (4). However, Suetsugu et al. (54) questioned the involvement of these structures in macropinosome formation. Here, by time-lapse live imaging of GAS6-stimulated LN229 cells expressing markers of the plasma membrane and actin, we revealed that macropinosomes were indeed generated upon closure of CDRs. However, the formation of macropinosomes following GAS6 stimulation was not accompanied by CDR formation in SKOV3 cells. Thus, we postulate that PR- and CDR-derived macropinosomes may represent separate populations of macropinosomes and that their molecular composition and function may differ. The existence of different types of macropinosomes with diverse functions is an exciting possibility that merits further research.

Cancer metastasis remains a major clinical problem. The driving mechanisms of each step of the metastatic cascade are still poorly characterized due to their complexity. Therefore, defining such mechanisms and their key molecular players is essential, especially to develop more effective therapies (2, 70, 71). A large body of evidence documents that AXL is an important regulator of cancer progression, invasion, and metastasis in a plethora of malignant tumors (28, 29, 72). Thus, to identify biological processes and molecular players underlying an AXL-dependent aggressive phenotype, we established its interaction network using the BioID assay. To our knowledge, a comprehensive AXL interactome has not been reported so far. However, the GAS6-induced phosphoproteome has been published during the revision of our manuscript (63). Our GO analysis of the identified AXL interactors indicated, among other things, enrichment of proteins implicated in actin dynamics, which were also enriched in the AXL phosphoproteome (63). Accordingly, we found that AXL was accumulated in actin-rich cell regions, including lamellipodia, in glioblastoma LN229 cells. Similarly, another recent study by Zajac et al. showed that AXL colocalized with F-actin at the leading edge of migrating mesenchymal triple-negative breast-cancer cells and that its depletion impaired the directionality of cell migration (73).

To leave a primary tumor and invade into the surrounding ECM and tissues, cancer cells have to migrate through complex three-dimensional environments. This requires active remodeling of the actin cytoskeleton and formation of specialized actin-rich structures and protrusions. For this reason, many actin-associated proteins, also those identified here as AXL interactors, like cortactin or WAVE2, are frequently overexpressed in metastatic cancers (45). Here, we describe several actin-dependent processes downstream of AXL activation in cancer cells, such as CDR formation, FA turnover, and macropinocytosis. Together with literature data, these findings reveal that the GAS6-AXL signaling axis drives multiple cellular processes involving actin remodeling that jointly result in an invasive phenotype. Moreover, the interaction network of AXL, including numerous actin-associated proteins, may explain its previously postulated contribution to EMT that could result from controlling actin-dependent processes needed for epithelial cells to acquire a mesenchymal phenotype (74, 75).

Here, we discovered that GAS6 stimulation triggered the formation of AXL-dependent CDRs, actin structures implicated in invasion. Previous studies and our data showed that CDRs are linked to FA turnover, as proteins from disassembling FAs are redistributed and transiently accumulated on CDRs (59, 76). We identified many FA components as AXL proximity interactors that independently confirm the role of AXL in the regulation of FA dynamics as also recently reported (63). AXL may also contribute to the formation of new FAs on the cell leading edge, since it was accumulated together with vinculin on lamellipodia that are sites of new FA assembly. Since mesenchymal migration of cancer cells requires constant disassembly of existing FAs and assembly of new ones, our results indicate that the GAS6-AXL signaling pathway may regulate these processes partially by triggering the formation of CDRs. AXL was recently shown to stimulate the formation and activity of invadopodia in melanoma cells (37). This is another type of actin-based protrusion important for cancer metastasis, as it degrades and remodels the ECM (77). Invadopodia and FAs share many components (78), some of which are AXL proximity interactors. This may indicate that the receptor is concentrated on invadopodia.

Macropinocytosis is another process discovered here that may contribute to AXL-promoted cancer progression and invasion. Several studies demonstrated that macropinocytosis, through uptake of extracellular proteins (e.g., albumin) and their further degradation in lysosomes, enables cancer cells to survive in a nutrient-poor tumor microenvironment (14, 18–20). However, the majority of these studies concentrated on macropinocytosis triggered by mutated RAS and/or were conducted in pancreatic-cancer cells, whereas data on RTK-mediated macropinocytosis as an alternative nutrient-uptake route in other cancer types were lacking. Our data suggest that AXL-driven macropinocytosis may, to some extent, be exploited by glioblastoma cells for uptake of extracellular albumin to allow them to proliferate under glutamine-poor conditions. During the revision of this manuscript, such a phenomenon has been reported for PDA cells grown under nutrient deprivation that up-regulated AXL to increase macropinocytic uptake of extracellular nutrients, in particular dead cells and cell debris (57). Intriguingly, Jayashankar and Edinger (16) have recently shown that macropinocytic internalization of necrotic cell debris drives proliferation and drug resistance of breast and prostate cancer with oncogenic mutations that activate KRAS or PI3K. In phagocytes, TAM receptors participate in efferocytosis, and TAM ligands are postulated to act as a bridge between phagocyte receptors and phosphatidylserine on apoptotic cells or cell debris (22, 25). As phagocytosis is mechanistically related to macropinocytosis, it is tempting to speculate that drug resistance of cancers with overactivated GAS6-AXL signaling results, at least partially, from their increased capability for macropinocytic internalization of cell debris.

Finally, our findings demonstrate that PI3K is an important downstream effector of GAS6-AXL signaling regulating invasion of glioblastoma cells grown as spheroids via activation of several actin-dependent processes. PI3K was previously implicated in AXL-driven invasion of ovarian cancers (30). These and our own findings suggest that PI3K inhibitors alone or in combination with AXL inhibitors may inhibit metastatic spread of malignant tumors with highly activated GAS6-AXL pathways. Importantly, recent studies demonstrated that the isoform β of PI3K specifically contributes to invasion of breast-cancer cells through the regulation of invadopodia maturation (79). Since usage of isoform-specific inhibitors can limit the toxicity of panPI3K inhibitors (80), it will be important to test which isoform of PI3K plays a predominant role in AXL-driven invasion. Notably, the Food and Drug Administration recently approved Alpelisib (BYL719) as the first PI3K inhibitor, specifically for the α isoform, for the treatment of advanced and metastatic breast cancer (81).

In summary, our study revealed that GAS6-activated AXL triggers cancer-cell invasion via induction of multiple actin-dependent processes that impact cell dynamics, adhesion, and metabolism. Moreover, AXL interactors identified here may constitute molecular targets for the development of effective therapies for patients with advanced and metastatic cancers.

Materials and Methods

Detailed procedures are provided in SI Appendix, Detailed Materials and Methods.

Reagents, Antibodies, and Plasmids.

Reagents, antibodies, and plasmids are listed in SI Appendix, Detailed Materials and Methods.

Cell Lines and Cell Culture.

LN229, MDA-MB-231, SKOV3, HEK293, HEK293T, and CCD-1070Sk cells were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC), and A549 cells from Sigma-Aldrich. Genetically modified LN229 cells (expressing different proteins or CRISPR-Cas9–mediated knockouts) were generated using standard DNA plasmid transfection or lentiviral transduction as described in SI Appendix, Detailed Materials and Methods. Cells were cultured in dedicated media supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) according to the ATCC instructions and regularly tested for mycoplasma contamination.

Cell Stimulation with GAS6 and Treatment with Inhibitors.

Cells were serum-starved for 16 h and stimulated with 400 ng/mL purified GAS6-MycHis (denoted as GAS6) at 37 °C outside of the CO2 incubator (in the presence of 20 mM Hepes, pH 7.5). When relevant, cells were treated with appropriate inhibitors for 30 min at 37 °C prior to stimulation with GAS6. Detailed protocols for GAS6-MycHis purification and cell stimulation are provided in SI Appendix, Detailed Materials and Methods.

Immunofluorescence Staining and Image Analysis.

Cells were fixed with 3.6% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 10 min and stained according to the immunofluorescence protocol with saponin or Triton X-100 permeabilization as described in SI Appendix, Detailed Materials and Methods. Images were acquired using the LSM 710 confocal microscope (Zeiss) with EC Plan-Neofluar 40 × 1.3 NA oil immersion objective, processed and analyzed as described in SI Appendix, Detailed Materials and Methods.

Live-Cell Imaging.

Live-cell imaging of GAS6-stimulated LN229 cells expressing mCherry or mCherry and LifeAct-mNeonGreen were performed using an Opera Phenix spinning disk confocal microscope or a Deltavision OMX V4 microscope, respectively, as described in SI Appendix, Detailed Materials and Methods.

BioID Assay.

HEK293 and LN229 cells expressing BirA*-HA or AXL-BirA*-HA were incubated with 50 μM biotin in the presence or absence of GAS6 for 24 h. Then, cells were lysed and biotinylated proteins were purified and analyzed by mass spectrometry as described in SI Appendix, Detailed Materials and Methods.

siRNA Transfection, Western Blot, qRT-PCR, Immunoprecipitation, Transwell Migration, and Spheroid Invasion Assay.

siRNA transfection, the Western blot, qRT-PCR, immunoprecipitation, transwell migration, and the spheroid invasion assay were conducted using standard procedures detailed in SI Appendix, Detailed Materials and Methods.

Human Phospho-Kinase Array.

The phosphorylation status and total amounts of 43 kinases were measured using the Human Phospho-Kinase Array from R&D Systems. Serum-starved LN229 cells were stimulated with 400 ng/mL GAS6 for 10 min at 37 °C and further processed according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

RAS-Activation Assay.

LN229 cells (1.25 × 106) were seeded on 10-cm dishes in complete medium. The next day, they were serum starved for 16 h prior to GAS6 stimulation for 5 and 10 min and processed according to the manufacturer’s protocol of the RAS Activation Assay Kit (Sigma-Aldrich).

Dextran-Uptake Assays.

Serum-starved LN229 cells were stimulated with GAS6 in the presence of 70,000 MW dextran conjugated with different fluorescent dyes, and then the fluorescence of internalized dextran was assessed by confocal microscopy or flow cytometry as described in SI Appendix, Detailed Materials and Methods.

Glutamine-Deprivation Assay.

WT and AXL knockout (gAXL#2) LN229 cells were seeded in triplicate into 96-well plates (2 × 103 cells/well) and cultured in complete medium for 24 h. Next, cells were washed once with PBS and incubated in medium containing 10% dialyzed FBS and 0.2 mM glutamine. Where indicated, 2% BSA was added. The medium was replaced every 24 h. After 6 d of culture, cell proliferation was measured using the ATPlite Luminescence Assay (PerkinElmer).

Cell-Spreading Assay.

WT and AXL knockout (gAXL#2) LN229 cells were trypsinized and serum starved as described elsewhere (76). Next, 8 × 104 cells were seeded in the presence or absence of GAS6 onto glass coverslips coated with 20 µg/mL fibronectin. After 30 min of incubation, cells were fixed, and actin was stained with phalloidin-Atto 390. The cell area was measured using ImageJ.

Statistical Methods.

Data are means ± SEM from at least three independent experiments unless stated otherwise. Statistical analysis was performed using the unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test and one sample t test or Mann–Whitney U test using GraphPad Prism version 8. The significance of mean comparison is annotated as follows: ns, nonsignificant (P > 0.05); *P ≤ 0.05; **P ≤ 0.01; ***P ≤ 0.001; and ****P ≤ 0.0001.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Krzysztof Kolmus for performing the GO analysis and Elżbieta Nowak for the initial help with GAS6 purification. We also thank Magdalena Banach-Orłowska, Małgorzata Maksymowicz, and Marta Kaczmarek for critical reading of the manuscript. We are grateful to Raymond B. Birge for providing a plasmid encoding GAS6. We acknowledge the support of Katarzyna Mleczko-Sanecka in the generation of CRISPR-Cas9 knockout cells. This work was supported by the SONATA Grant 2015/19/D/NZ3/03270 from the National Science Center to D.Z.-B. D.Z.-B received a Short-Term Fellowship awarded by The Federation of European Biochemical Societies. M.M. and K.J. were supported by TEAM Grant POIR.04.04.00-00-20CE/16-00, and K.P. was supported by TEAM-TECH Core Facility Plus/2017-2/2 Grant POIR.04.04.00-00-23C2/17-00, both grants from the Foundation for Polish Science cofinanced by the European Union under the European Regional Development Fund.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission. J.M. is a guest editor invited by the Editorial Board.

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.2024596118/-/DCSupplemental.

Data Availability

The mass-spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited to the Proteomics Identification Database partner repository (82) with the dataset identifier PXD017933 (83). All other study data are included in the article and/or supporting information.

References

- 1.Lambert A. W., Pattabiraman D. R., Weinberg R. A., Emerging biological principles of metastasis. Cell 168, 670–691 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Steeg P. S., Targeting metastasis. Nat. Rev. Cancer 16, 201–218 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Caswell P. T., Zech T., Actin-based cell protrusion in a 3D matrix. Trends Cell Biol. 28, 823–834 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hoon J. L., Wong W. K., Koh C. G., Functions and regulation of circular dorsal ruffles. Mol. Cell. Biol. 32, 4246–4257 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buccione R., Orth J. D., McNiven M. A., Foot and mouth: Podosomes, invadopodia and circular dorsal ruffles. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 5, 647–657 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mellström K., Heldin C. H., Westermark B., Induction of circular membrane ruffling on human fibroblasts by platelet-derived growth factor. Exp. Cell Res. 177, 347–359 (1988). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abella J. V., Parachoniak C. A., Sangwan V., Park M., Dorsal ruffle microdomains potentiate Met receptor tyrosine kinase signaling and down-regulation. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 24956–24967 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Azimifar S. B., et al., Induction of membrane circular dorsal ruffles requires co-signalling of integrin-ILK-complex and EGF receptor. J. Cell Sci. 125, 435–448 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chiasson-MacKenzie C., et al., Merlin/ERM proteins regulate growth factor-induced macropinocytosis and receptor recycling by organizing the plasma membrane:cytoskeleton interface. Genes Dev. 32, 1201–1214 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Corallino S., et al., A RAB35-p85/PI3K axis controls oscillatory apical protrusions required for efficient chemotactic migration. Nat. Commun. 9, 1475 (2018). Correction in: Nat. Commun. 9, 2085 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yoshida S., Pacitto R., Sesi C., Kotula L., Swanson J. A., Dorsal ruffles enhance activation of Akt by growth factors. J. Cell Sci. 131, jcs220517 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kerr M. C., Teasdale R. D., Defining macropinocytosis. Traffic 10, 364–371 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marques P. E., Grinstein S., Freeman S. A., SnapShot:Macropinocytosis. Cell 169, 766–766.e1 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Commisso C., et al., Macropinocytosis of protein is an amino acid supply route in Ras-transformed cells. Nature 497, 633–637 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim S. M., et al., PTEN deficiency and AMPK activation promote nutrient scavenging and anabolism in prostate cancer cells. Cancer Discov. 8, 866–883 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jayashankar V., Edinger A. L., Macropinocytosis confers resistance to therapies targeting cancer anabolism. Nat. Commun. 11, 1121 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Commisso C., The pervasiveness of macropinocytosis in oncological malignancies. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B. Biol. Sci. 374, 20180153 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Palm W., Metabolic functions of macropinocytosis. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B. Biol. Sci. 374, 20180285 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Recouvreux M. V., Commisso C., Macropinocytosis: A metabolic adaptation to nutrient stress in cancer. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne) 8, 261 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee S. W., et al., EGFR-pak signaling selectively regulates glutamine deprivation-induced macropinocytosis. Dev. Cell 50, 381–392.e5 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yoshida S., Pacitto R., Yao Y., Inoki K., Swanson J. A., Growth factor signaling to mTORC1 by amino acid-laden macropinosomes. J. Cell Biol. 211, 159–172 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nguyen K. Q., Tsou W. I., Kotenko S., Birge R. B., TAM receptors in apoptotic cell clearance, autoimmunity, and cancer. Autoimmunity 46, 294–297 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Burstyn-Cohen T., Maimon A., TAM receptors, phosphatidylserine, inflammation, and cancer. Cell Commun. Signal. 17, 156 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zagórska A., Través P. G., Lew E. D., Dransfield I., Lemke G., Diversification of TAM receptor tyrosine kinase function. Nat. Immunol. 15, 920–928 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lemke G., Burstyn-Cohen T., TAM receptors and the clearance of apoptotic cells. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1209, 23–29 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lew E. D., et al., Differential TAM receptor-ligand-phospholipid interactions delimit differential TAM bioactivities. eLife 3, e03385 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tsou W. I., et al., Receptor tyrosine kinases, TYRO3, AXL, and MER, demonstrate distinct patterns and complex regulation of ligand-induced activation. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 25750–25763 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Paccez J. D., Vogelsang M., Parker M. I., Zerbini L. F., The receptor tyrosine kinase Axl in cancer: Biological functions and therapeutic implications. Int. J. Cancer 134, 1024–1033 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wu X., et al., AXL kinase as a novel target for cancer therapy. Oncotarget 5, 9546–9563 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rankin E. B., et al., AXL is an essential factor and therapeutic target for metastatic ovarian cancer. Cancer Res. 70, 7570–7579 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rankin E. B., Giaccia A. J., The receptor tyrosine kinase AXL in cancer progression. Cancers (Basel) 8, 103 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hutterer M., et al., Axl and growth arrest-specific gene 6 are frequently overexpressed in human gliomas and predict poor prognosis in patients with glioblastoma multiforme. Clin. Cancer Res. 14, 130–138 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vajkoczy P., et al., Dominant-negative inhibition of the AXL receptor tyrosine kinase suppresses brain tumor cell growth and invasion and prolongs survival. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 5799–5804 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Onken J., et al., Inhibiting receptor tyrosine kinase AXL with small molecule inhibitor BMS-777607 reduces glioblastoma growth, migration, and invasion in vitro and in vivo. Oncotarget 7, 9876–9889 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Goyette M. A., et al., The receptor tyrosine kinase AXL is required at multiple steps of the metastatic cascade during HER2-positive breast cancer progression. Cell Rep. 23, 1476–1490 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gjerdrum C., et al., Axl is an essential epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition-induced regulator of breast cancer metastasis and patient survival. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 1124–1129 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Revach O. Y., Sandler O., Samuels Y., Geiger B., Cross-talk between receptor tyrosine kinases AXL and ERBB3 regulates invadopodia formation in melanoma cells. Cancer Res. 79, 2634–2648 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chaffer C. L., San Juan B. P., Lim E., Weinberg R. A., EMT, cell plasticity and metastasis. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 35, 645–654 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Antony J., Huang R. Y., AXL-driven EMT state as a targetable conduit in cancer. Cancer Res. 77, 3725–3732 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Davra V., Kimani S. G., Calianese D., Birge R. B., Ligand activation of TAM family receptors-implications for tumor biology and therapeutic response. Cancers (Basel) 8, 107 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sheridan C., First AXL inhibitor enters clinical trials. Nat. Biotechnol. 31, 775–776 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Holt B., Micklem D., Brown A., Yule M., Lorens J., Predictive and pharmacodynamic biomarkers associated with phase II, selective and orally bioavailable AXL inhibitor bemcentinib across multiple clinical trials. Ann. Oncol. 29 (suppl. 8), viii14–viii57 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Roux K. J., Kim D. I., Raida M., Burke B., A promiscuous biotin ligase fusion protein identifies proximal and interacting proteins in mammalian cells. J. Cell Biol. 196, 801–810 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lambert J. P., Tucholska M., Go C., Knight J. D., Gingras A. C., Proximity biotinylation and affinity purification are complementary approaches for the interactome mapping of chromatin-associated protein complexes. J. Proteomics 118, 81–94 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yamaguchi H., Condeelis J., Regulation of the actin cytoskeleton in cancer cell migration and invasion. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1773, 642–652 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Krueger E. W., Orth J. D., Cao H., McNiven M. A., A dynamin-cortactin-Arp2/3 complex mediates actin reorganization in growth factor-stimulated cells. Mol. Biol. Cell 14, 1085–1096 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nascimento E. B., et al., Insulin-mediated phosphorylation of the proline-rich Akt substrate PRAS40 is impaired in insulin target tissues of high-fat diet-fed rats. Diabetes 55, 3221–3228 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lanzetti L., Palamidessi A., Areces L., Scita G., Di Fiore P. P., Rab5 is a signalling GTPase involved in actin remodelling by receptor tyrosine kinases. Nature 429, 309–314 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Castellano E., Downward J., RAS interaction with PI3K: More than just another effector pathway. Genes Cancer 2, 261–274 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Buckley C. M., King J. S., Drinking problems: Mechanisms of macropinosome formation and maturation. FEBS J. 284, 3778–3790 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schnatwinkel C., et al., The Rab5 effector Rabankyrin-5 regulates and coordinates different endocytic mechanisms. PLoS Biol. 2, E261 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Commisso C., Flinn R. J., Bar-Sagi D., Determining the macropinocytic index of cells through a quantitative image-based assay. Nat. Protoc. 9, 182–192 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Galenkamp K. M. O., Alas B., Commisso C., Quantitation of macropinocytosis in cancer cells. Methods Mol. Biol. 1928, 113–123 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Suetsugu S., Yamazaki D., Kurisu S., Takenawa T., Differential roles of WAVE1 and WAVE2 in dorsal and peripheral ruffle formation for fibroblast cell migration. Dev. Cell 5, 595–609 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Koivusalo M., et al., Amiloride inhibits macropinocytosis by lowering submembranous pH and preventing Rac1 and Cdc42 signaling. J. Cell Biol. 188, 547–563 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hoeller O., et al., Two distinct functions for PI3-kinases in macropinocytosis. J. Cell Sci. 126, 4296–4307 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.King B., Araki J., Palm W., Thompson C. B., Yap/Taz promote the scavenging of extracellular nutrients through macropinocytosis. Genes Dev. 34, 1345–1358 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Balogh I., Hafizi S., Stenhoff J., Hansson K., Dahlbäck B., Analysis of Gas6 in human platelets and plasma. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 25, 1280–1286 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gu Z., Noss E. H., Hsu V. W., Brenner M. B., Integrins traffic rapidly via circular dorsal ruffles and macropinocytosis during stimulated cell migration. J. Cell Biol. 193, 61–70 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zaidel-Bar R., Cohen M., Addadi L., Geiger B., Hierarchical assembly of cell-matrix adhesion complexes. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 32, 416–420 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Huveneers S., Danen E. H., Adhesion signaling - Crosstalk between integrins, Src and Rho. J. Cell Sci. 122, 1059–1069 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zobel M., et al., A NUMB-EFA6B-ARF6 recycling route controls apically restricted cell protrusions and mesenchymal motility. J. Cell Biol. 217, 3161–3182 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Abu-Thuraia A., et al., AXL confers cell migration and invasion by hijacking a PEAK1-regulated focal adhesion protein network. Nat. Commun. 11, 3586 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Goh L. K., Sorkin A., Endocytosis of receptor tyrosine kinases. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 5, a017459 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Miaczynska M., Effects of membrane trafficking on signaling by receptor tyrosine kinases. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 5, a009035 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hunt C. L., Kolokoltsov A. A., Davey R. A., Maury W., The Tyro3 receptor kinase Axl enhances macropinocytosis of Zaire ebolavirus. J. Virol. 85, 334–347 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Fedeli C., et al., Axl can serve as entry factor for Lassa virus depending on the functional glycosylation of dystroglycan. J. Virol. 92, e01613-1 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bell J. How BerGenBio became a frontrunner in UK hunt for Covid-19 treatment, https://www.clinicaltrialsarena.com/analysis/bergenbio-covid-19-treatment/ (12 May 2020).

- 69.Orth J. D., Krueger E. W., Weller S. G., McNiven M. A., A novel endocytic mechanism of epidermal growth factor receptor sequestration and internalization. Cancer Res. 66, 3603–3610 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Chitty J. L., et al., Recent advances in understanding the complexities of metastasis. F1000 Res. 7, 1169 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Menezes M. E., et al., Detecting tumor metastases: The road to therapy starts here. Adv. Cancer Res. 132, 1–44 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kimani S. G., et al., Normalization of TAM post-receptor signaling reveals a cell invasive signature for Axl tyrosine kinase. Cell Commun. Signal. 14, 19 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zajac O., et al., AXL controls directed migration of mesenchymal triple-negative breast cancer cells. Cells 9, 247 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sun B. O., Fang Y., Li Z., Chen Z., Xiang J., Role of cellular cytoskeleton in epithelial-mesenchymal transition process during cancer progression. Biomed. Rep. 3, 603–610 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Yilmaz M., Christofori G., EMT, the cytoskeleton, and cancer cell invasion. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 28, 15–33 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Reinecke J. B., Katafiasz D., Naslavsky N., Caplan S., Regulation of Src trafficking and activation by the endocytic regulatory proteins MICAL-L1 and EHD1. J. Cell Sci. 127, 1684–1698 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Eddy R. J., Weidmann M. D., Sharma V. P., Condeelis J. S., Tumor cell invadopodia: Invasive protrusions that orchestrate metastasis. Trends Cell Biol. 27, 595–607 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wang Y., McNiven M. A., Invasive matrix degradation at focal adhesions occurs via protease recruitment by a FAK-p130Cas complex. J. Cell Biol. 196, 375–385 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Erami Z., Heitz S., Bresnick A. R., Backer J. M., PI3Kβ links integrin activation and PI(3,4)P2 production during invadopodial maturation. Mol. Biol. Cell 30, 2367–2376 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hanker A. B., Kaklamani V., Arteaga C. L., Challenges for the clinical development of PI3K inhibitors: Strategies to improve their impact in solid tumors. Cancer Discov. 9, 482–491 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.FDA , FDA approves first PI3K inhibitor for breast cancer, https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-first-pi3k-inhibitor-breast-cancer (24 May 2019).

- 82.Perez-Riverol Y., et al., The PRIDE database and related tools and resources in 2019: Improving support for quantification data. Nucleic Acids Res. 47 (D1), D442–D450 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Poświata A., Zdżalik-Bielecka D., Identification of AXL interactome by proximity-dependent protein identification (BioID). The Proteomics Identifications Database (PRIDE). http://www.ebi.ac.uk/pride/archive/projects/PXD017933. Deposited 9 March 2020.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement