Abstract

Prognosing life-threatening orthopaedic infections caused by Staphylococcus aureus remains a major clinical challenge. To address this, we developed a multiplex assay to assess the humoral immune proteome against S. aureus in patients with musculoskeletal infections. We found initial evidence that antibodies against some antigens (autolysins: Amd, Gmd; secreted immunotoxins: CHIPS, SCIN, Hla) were associated with protection, while antibodies against the iron-regulated surface determinant (Isd) proteins (IsdA, IsdB, IsdH) were aligned with adverse outcomes. To formally test this, we analyzed antibody levels and 1-year clinical outcomes of 194 patients with confirmed S. aureus bone infections (AO Trauma CPP Bone Infection Registry). A staggering 20.6% of the enrolled patients experienced adverse clinical outcomes (arthrodesis, reinfection, amputation, and septic death) after 1-year. At enrollment, anti-S. aureus IgG levels in patients with adverse outcomes were 1.35-fold lower than those in patients whose infections were successfully controlled (p<0.0001). Overall, there was a 51–69% reduction in adverse outcome risk for every 10-fold increase in initial IgG concentration against Gmd, Amd, IsdH, CHIPS, SCIN, and Hla (p<0.05). Notably, anti-IsdB antibodies remained elevated in patients with adverse outcomes; for every 10-fold change in the ratio of circulating anti-Isd to anti-autolysin IgG at enrollment, there was a trending 2.6-fold increased risk (Odds Ratio=2.555) of an adverse event (p=0.105). Moreover, antibody increases over time correlated with adverse outcomes, and decreases with positive outcomes. These studies demonstrate the potential of the humoral immune response against S. aureus as a prognostic indicator for assessing treatment success and identifying patients requiring additional interventions.

Keywords: Orthopaedic Infections, Host Immunity, Staphylococcus aureus, Osteomyelitis, 2-Stage Revision Surgery

Introduction

Bone Infection continues to be the bane of orthopaedic surgery with an urgent need for novel therapeutics.1 The infection rates following total joint arthroplasties have essentially remained the same at 1–2% for the past 50 years, despite significant advances in surgical techniques, and adherence to rigorous prophylactic surgical protocols.2; 3 The major pathogen Staphylococcus aureus is responsible for causing 30–42% of fracture-related infections (FRI)4; 5 and 10,000–20,000 infections in prosthetic joint patients each year in the United States alone.6; 7 Majority of the severe cases of osteomyelitis are primarily caused by methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) and newly emerging strains with pan-resistance.8; 9

Considerable efforts to address non-antibiotic anti-S. aureus interventions, such as immunotherapies that could limit or eliminate the pathogen, have failed.10–12 Several S. aureus passive and active vaccines evaluated by U.S Food and Drug Administration have failed to demonstrate efficacy in large clinical trials. Most notably, a vaccine based on iron-regulated surface determinant B developed by Merck, (IsdB-V710) provided little or no protection, but elevated the risk of poor outcomes, including death, among patients who encountered post-immunization S. aureus infections.13 This unexpected phenomenon has been attributed to the pathogenic role of anti-IsdB IgG enabling the passage of S. aureus into the bloodstream and its dissemination to distal organs.14 Indeed, in our clinical studies, we observed that patients who died from S. aureus osteomyelitis were among those experiencing the greatest elevation of anti-IsdB IgG levels.15 In sharp contrast, patients with periprosthetic joint infections (PJI) experiencing positive outcomes tend to have greater abundance of the IgG specific for the autolysin-derived enzymes, amidase (Amd) and glucosaminidase (Gmd).16; 17 Additionally, we have also shown that elevated anti-S. aureus antibody levels can be useful for diagnosing ongoing S. aureus orthopaedic infections.15; 18; 19

In the current study, we examined an international biospecimen registry (AO Trauma Clinical Priority Program (CPP) Bone Infection Registry20) of patients experiencing S. aureus orthopaedic infections to understand if: 1) there are immunological signatures at the time of presentation that predict successful elimination of the S. aureus infection; and 2) postoperative anti-S. aureus IgG levels correlate with successful infection resolution or failure. Specifically, we performed post-hoc correlative analyses on anti-S. aureus IgG levels and 1-year clinical outcomes on patients from the AO Trauma CPP Bone Infection Registry to investigate the following hypotheses: 1) Patients who experienced adverse outcomes due to the surgical procedures have lower anti-S. aureus IgG compared to patients who have successfully resolved their infections 2) Anti-IsdB antibody levels and ratio of circulating pathogenic anti-Isd (anti-IsdA + anti-IsdB + anti-IsdH) vs. protective anti-autolysin (anti-Gmd + anti- Amd) IgG at the time of surgery correlate with adverse outcome at 1-year post-operatively. Here, we describe analyses and results aiming to test these hypotheses and identify signatures of humoral immunity against S. aureus, that are associated with and predictive of clinical outcomes following bone infection.

Materials and Methods

Patient enrollment.

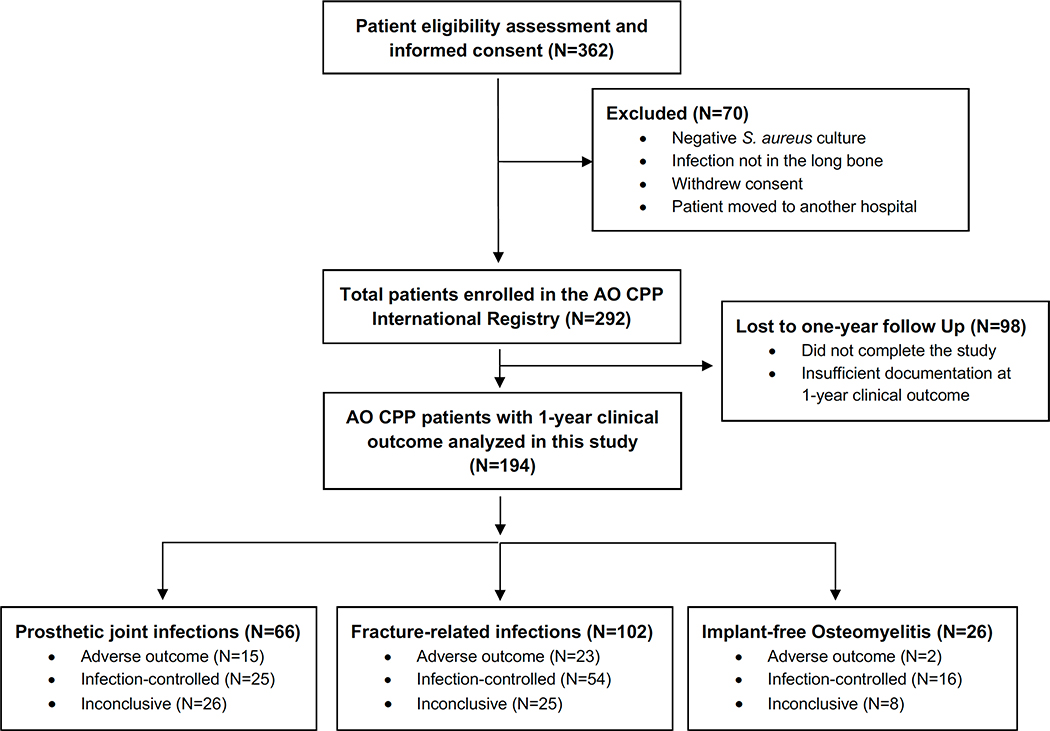

This study was performed on serum samples obtained from patients who were part of an international biospecimen registry (AO Trauma Clinical Priority Program (CPP) Bone Infection Registry20). This registry consists of 292 patients who experienced long bone (i.e., femur, tibia, fibula, humerus, radius, ulna, or clavicle) S. aureus infections and were enrolled between November 2012 and August 2017 in 18 centers around the world (Europe, North America, South America and Asia). All patients were recruited with local IRB approval, and patient information was collected in a REDCap database managed by AO Trauma administrators. A detailed description of patient enrollment, sample collection, and the numerous clinical, patient-reported outcome measures, end-points that were collected have recently been discussed.20 Additionally, the flow chart in Fig. 1, summarizes the AO Trauma CPP Bone Infection Registry study design. In the current study, we analyzed anti-S. aureus IgG levels and clinical outcomes in a subset of 194 patients who completed the study and had 1-year follow-up data on clinical outcomes (Fig. 1). Laboratory investigators had access only to de-identified clinical data provided on request by the AO Trauma data management team.

Figure 1. Flow chart depicting the AO Trauma CPP Bone Infection Registry study design.

This registry consists of 292 patients who experienced long bone (i.e., femur, tibia, fibula, humerus, radius, ulna, or clavicle) S. aureus infections enrolled in 18 centers around the world (Europe, North America, South America and Asia). Among these, 194 patients completed the study with 1-year follow-up data on clinical outcomes measures.

Clinical outcomes.

This study focused on patients whose clinical outcomes were definable 1-year after the surgical procedure; they were categorized into three outcome groups: 1) “infection-controlled”; 2) “adverse outcome”; and 3) “inconclusive”. The defining measures of “infection-controlled” group were retention of the bone and successful re-implantation combined with resolution of the infection. The “adverse outcomes” group included those suffering loss of function (arthrodesis, removal of implant without replacement, amputation), definitive surgery prior to or at the 12-month post-operative visit, as well as reinfection following reimplantation and septic death due to S. aureus. Patients were considered “inconclusive” if they were judged to be clinically “healing” but not “healed” at the end of the 12-month period of observation.

Serology and Luminex-based immunoassays.

Serum samples and clinical data were collected in the biospecimen registry at the time of enrollment (t=0), at 6-month and 1-year postoperatively.20 Of the 194 patients with t=0 data, 133 had 6-month follow-up, 124 had 12-month follow-up. Serum samples were stored frozen at the originating site and then shipped for long-term storage and analysis to Virginia Commonwealth University in Richmond, VA. Serum IgG antibodies against S. aureus antigens in the infected patients were measured using a custom, eight-antigen, Luminex immunoassay as previously described.15; 17; 21; 22 The eight antigens included three proteins from the S. aureus iron-regulated surface determinant system, IsdA, IsdB and IsdH; three secretory proteins that interfere with host defense: the staphylococcal complement inhibitor (SCIN), the chemotaxis inhibitory protein from S. aureus (CHIPS) and the secreted toxin, α-hemolysin (Hla); and the two domains of the cell wall autolysin (Atl), amidase (Amd) and glucosaminidase (Gmd). For measurement of S. aureus reactive IgG, 1000 Streptavidin-coated magnetic beads per analyte per well were mixed, sonicated, and 50 μL per well were incubated for 2 hours at room temperature with 50 μL of patient sera (in duplicates) diluted 5,000-fold (10,000-fold after addition of beads). Following a brief wash step to remove the diluted serum sample, the phycoerythrin-conjugated goat anti-human IgG reagent (Southern Biotech) was added to each sample for 60 minutes prior to a final wash and measurement of human IgG bound to each antigen on a Luminex 200™ instrument (Luminex 200, xPONENT v3.1, Luminex Corp, Austin, TX). IgG titers are reported as arbitrary median fluorescent intensity (MFI) units. As described in our previous studies16; 21; 22, the MFI data generated by Luminex was accepted for downstream data analyses if the coefficient of variation (the ratio of standard deviation (SD) to the mean) among the replicates was <20%.

Statistical Data Analyses.

Comparison of 8-array anti-S. aureus antibody measurements across “infection-controlled” and “adverse outcome” patients at t=0 and later timepoints was performed using repeated measures ANOVA. The odds of adverse events and beneficial outcomes were modeled utilizing logistic regression, and results are presented as Odds Ratios (ORs) with corresponding 95% confidence intervals and p-values for each antibody. Base-10 log-transformations were used on the antibody titer values in the logistic regression models to reduce skewness and improve model fit, resulting in ORs interpreted as relative odds per 10-fold increase in antibody titer values. For 6-month and 1-year follow-up antibody measurements, data were by expressing the follow-up measurements as a percentage of the corresponding t=0 values, and similar risk factor analyses were performed. All analyses were conducted using SAS (version 9.4) and GraphPad Prism (version 8.4.3). A p-value of <0.05 was considered significant.

Results

The population was predominated by patients suffering prosthetic joint infections and fracture-related infections.

Serum anti-S. aureus IgG levels were analyzed in a cohort of 194 patients with S. aureus infections and reported 1-year clinical outcome from the AO Trauma CPP Bone Infection Registry. Within the cohort, 20.6% (40 out of 194) reported adverse outcomes including arthrodesis, reinfection, amputation, and septic death. Of these 194 patients,102 (53%) had fracture-related infections of the long bones (FRI; 54 infection-controlled; 23 adverse outcomes; 25 inconclusive); 66 (34%) had prosthetic joint infections (PJI; 25 infection-controlled; 15 adverse outcomes; 26 inconclusive); and 26 (13%) had implant-free osteomyelitis (OM; 16 infection controlled; 2 adverse outcomes; 8 inconclusive) (Fig. 1).

Anti-S. aureus IgG levels at enrollment are lower in patients who will later experience adverse outcomes due to orthopaedic infections.

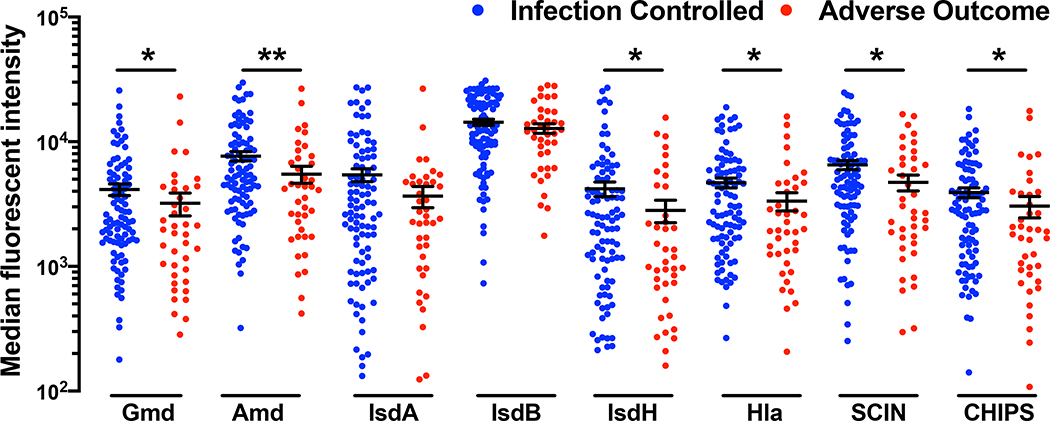

At enrollment, IgG levels against S. aureus antigens were 1.35-fold lower (p<0.0001) among patients who suffered “adverse outcomes” compared to patients who experienced positive “infection-controlled” outcomes (Fig. 2). Specifically, IgG levels against the autolysin subunits (Gmd, Amd), the secreted virulence proteins CHIPS, SCIN, Hla and the iron-scavenging protein IsdH were significantly lower in patients with adverse outcomes (p<0.05). Anti-IsdA and anti-IsdB levels were similar in both patient groups. When IgG levels were analyzed within the subpopulations of PJI and FRI patients, adverse outcome patients had lower antibody levels for most S. aureus antigens compared to the infection-controlled group (Supplemental Fig. 1).

Figure 2. Anti-S. aureus IgG levels are lower in patients with adverse outcomes due to orthopaedic infections.

Serum IgG levels at the time of enrollment, represented as Median fluorescent intensity, against 8 S. aureus antigens determined via Luminex for patients in the AOTrauma CPP Bone Infection Registry with reported S. aureus infections (N=194). IgG levels of patients who completed the study out to 1-year with recorded clinical outcome such as “infection controlled” (N=95) or “adverse outcome” (N=40; fracture present, infection present, septic death, amputation, and definitive surgery at 1-year) or “inconclusive” (N=59) were calculated. Serum IgG titers of patients who had successful and adverse outcomes are presented here (*p< 0.05, **p< 0.01, Mann-Whitney test).

This initial elevation of antibody levels is presented in a quantitative manner in Table 1 where we computed the odds ratios of adverse outcomes and controlled infections using univariate and continuous predictor logistic regression models. Low antibody levels in these calculations were defined as the IgG levels in the lower quartile (<25%) for each S. aureus antigen. For the six antigens Gmd, Amd, IsdH, SCIN, CHIPS and Hla, ten-fold increases in antibody levels at the time of enrollment correlated with 51–69% decreases in risk of adverse outcomes and these measures were statistically significant (Table 1, p<0.05). As observed in Fig. 2, anti-IsdA and anti-IsdB levels tended higher in patients who would not suffer adverse outcomes but did not attain statistical significance (p>0.13). Interestingly, demographic risk factors such as age > 70, male sex, and co-morbid risk factors such as diabetes and body mass index (BMI) > 40 kg/m2 were not associated with increased adverse clinical outcomes (Table 1).

Table 1.

Relative risk of an adverse outcomes in patients due to lack of anti-S. aureus IgG in patients

| Risk Factors | Risk of Adverse Events | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Incidence of low antibody levels (%) | Odds Ratio* | 95% CI | P-value | |||

| Antigen | Function | ||||||

| Anti-Gmd | Cell division | 194 | 33.3 | 0.400 | 0.17, 0.96 | 0.040 | |

| Anti-Amd | 194 | 33.3 | 0.312 | 0.13, 0.77 | 0.012 | ||

| Anti-Gmd+Anti-Amd | 194 | 33.3 | 0.318 | 0.13, 0.80 | 0.015 | ||

| Anti-IsdA | Iron scavenging | 194 | 22.9 | 0.614 | 0.32, 1.17 | 0.137 | |

| Anti-IsdB | 194 | 22.9 | 0.697 | 0.25, 1.96 | 0.493 | ||

| Anti-IsdH | 194 | 31.3 | 0.487 | 0.25, 0.95 | 0.035 | ||

| Anti-IsdA+Anti-IsdB+Anti-IsdH | 194 | 25.0 | 0.550 | 0.21, 1.43 | 0.219 | ||

| Anti-Hla | Toxin and Immune evasion | 194 | 33.3 | 0.308 | 0.13, 0.75 | 0.009 | |

| Anti-SCIN | 194 | 37.5 | 0.343 | 0.15, 0.81 | 0.014 | ||

| Anti-CHIPS | 194 | 33.3 | 0.340 | 0.15, 0.77 | 0.010 | ||

| Anti-Hla+Anti-SCIN+Anti-CHIPS | 194 | 35.4 | 0.232 | 0.09, 0.63 | 0.004 | ||

| Anti-Gmd+Anti-Amd+ Anti-IsdA+Anti-IsdB+Anti-IsdH+ Anti-Hla+Anti-SCIN+Anti-CHIPS | 194 | 31.3 | 0.313 | 0.11, 0.90 | 0.032 | ||

| BMI > 40 kg/m2 | 193 | 7.3 | 1.05 | 0.28, 3.95 | 0.946 | ||

| Diabetes | 166 | 17.5 | 1.71 | 0.68, 4.29 | 0.256 | ||

| Age > 70 | 194 | 17 | 2.28 | 0.99, 5.21 | 0.052 | ||

| Female | 194 | 32.5 | 1.52 | 0.74, 3.12 | 0.256 | ||

Odds ratio calculated for every 10-fold increase in anti-S. aureus antibody levels in patients at the time of enrollment

The IgG responses to different antigen groups have increased prognostic power.

Assessing the anti-Atl (Amd+Gmd) antibody levels as a continuous variable revealed that ten-fold increases in IgG at enrollment correlated with a 68.2% reduction in risk of adverse clinical outcomes (p=0.015). Similarly, assessing the antibody levels of the three secretory proteins (SCIN+CHIPS+Hla) correlated with a remarkable 76.8% reduction in the risk of adverse events (p=0.004). Finally, the collective humoral immune proteome levels (sum of all antigens) increase also correlates with a 68.7% decrease in risk of adverse outcomes (Table 1, p=0.032).

Post-operative anti-S. aureus IgG levels in patients correlate with persistent bone infection.

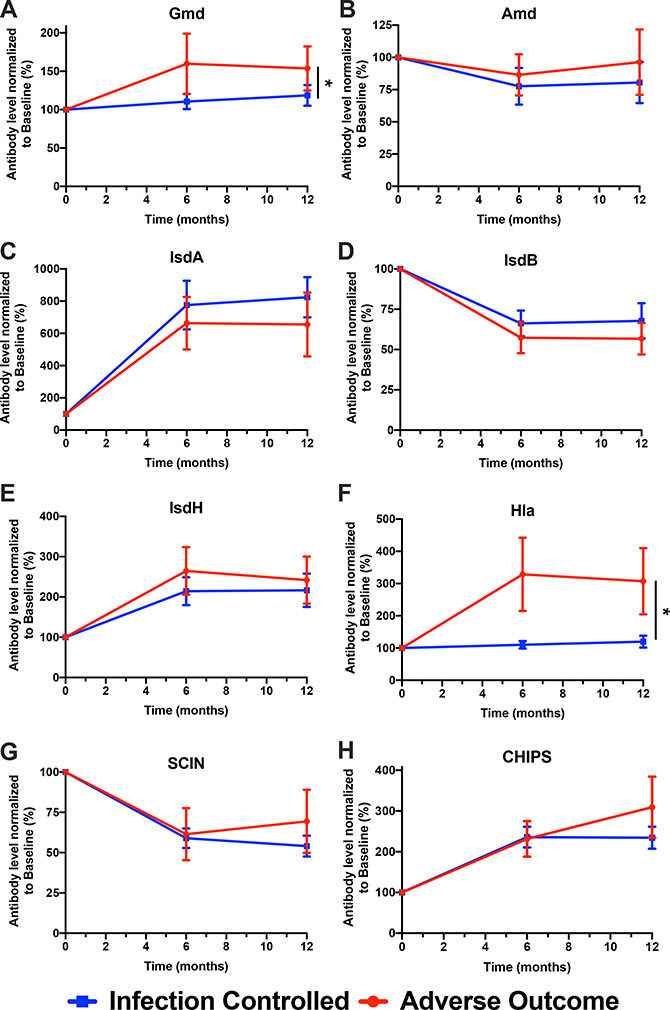

The mean levels of anti-antigen IgG were measured in samples from all enrolled patients at the 6-month and 1-year timepoints and the observed values were normalized to the IgG levels measured at enrollment (Fig. 3). For several of the antigens, the IgG levels are similar between the Infection-Controlled and Adverse Outcome populations at all three time points, particularly Amd, IsdA, IsdB, and IsdH. Levels of IgG specific for the immune evasion molecules SCIN and CHIPS trended higher for the Adverse Outcome population at 12-months, but the elevations were not significant. IgG levels specific for Gmd and Hla were significantly elevated at both the 6- and 12-month timepoints in the Adverse Outcome population suggesting that they may correlate with persistent infections (Supplemental Table 1).

Figure 3. Change in anti-S. aureus IgG in patients with S. aureus orthopaedic infections stratified by infection outcome at 1-year post-enrollment.

IgG titers against S. aureus cell division proteins (Gmd, Amd), iron scavenging proteins (IsdA, IsdB, IsdH), toxins (Hla), and immune evasion proteins (SCIN, CHIPS) at 6 months and 1-year post-enrollment were normalized to MFI values measured at t=0 and represented as a percentage of change over time (N=135 at t=0, N=101 at 6 months, N = 95 at 12 months, *p< 0.05, **p< 0.01, Repeated Measures ANOVA).

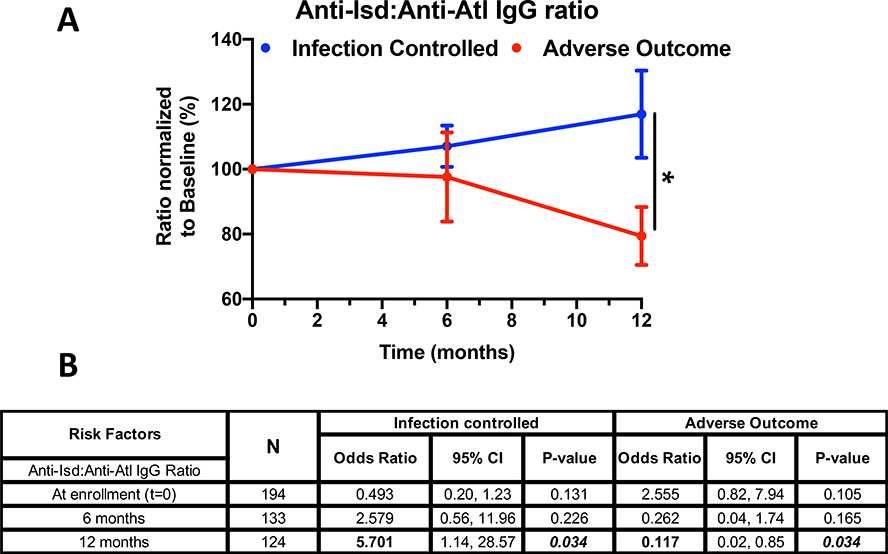

The ratio of anti-Isd IgG (anti-IsdA + anti-IsdB + anti-IsdH) to the anti-Atl IgG (anti-Amd + anti-Gmd) provides a simple measure of risk of persistent infection.

We hypothesized that elevated circulating pathogenic anti-Isd IgG correlates with adverse outcomes and that elevated protective anti-Atl IgG aligns with infection control or successful treatment outcomes. To test this, the ratio of IgG specific for the Isd antigens (IsdA, IsdB, IsdH) to the IgG specific for the Atl (Gmd, Amd) antigens was assessed (Fig. 4A), normalized to levels measured at enrollment. Among the “infection-controlled” population, this ratio tends to increase slightly (i.e., anti-Atl tends to decrease) over the 12-month period of observation, while in the Adverse Outcome population, the ratio declines slightly at 6 months and significantly at 12 months. The decline in this ratio is driven by the retention of increases in the anti-Atl IgG levels in patients with infectious complications. These trends are presented quantitatively in Fig. 4B. Notably, for every 10-fold change in the ratio of circulating anti-Isd (anti-IsdA + anti-IsdB + anti-IsdH) vs. anti-Atl (anti-Gmd + anti- Amd) IgG at the time of enrollment, there was a 2.6-fold increased risk (OR=2.555, 95% confidence interval 0.82 to 7.94, p=0.105) of an adverse outcome. For 10-fold change in the ratio of anti-IsdB alone vs. anti-Atl, there was a significant 3.5-fold increased risk (OR=3.505, 95% confidence interval 1.15 to 10.68, p=0.027) of adverse event. Moreover, as observed in Fig. 4A, the decline in the ratio postoperatively lead to an 88.3% reduction in the risk of adverse outcome at 1-year (p=0.034) and a 5.7-fold increase in the probability of positive outcome at 12 months. Collectively, these results suggest that anti-Isd vs. anti-Atl ratio can be utilized as a prognostic index for assessing treatment outcome in patients with S. aureus bone infections.

Figure 4. Ratio of anti-Isd vs. anti-Atl IgG responses can prognostically predict clinical outcome in patients with S. aureus bone infections.

A) Due to the highly skewed distributions of the circulating Isd and Atl antibody levels (Figure 3), the ratio of anti-Isd and anti-Atl responses and their fold change over time from enrollment were computed for prediction of outcome (*p< 0.05, Repeated Measures ANOVA). B) OR of change in anti-Isd:anti-Atl correlating to clinical outcome were computed at t=0, 6 months, and 1-year post-enrollment. Interestingly, for every 10-fold change in the ratio at baseline, there is a 2.5-fold increase in chance (OR=2.555) of adverse outcome in these patients (p= 0.105). Conversely, at 1-year post-enrollment, there is an 88.3% reduction in risk (odds) of adverse events (*p= 0.034) due to the ratio change.

Discussion

Serum antibody levels at the time of diagnosis are related to outcome.

Our hypothesis has been that a strong IgG response against certain S. aureus antigens will identify those patients likely to experience successful resolutions of challenging orthopaedic infections. In this large international group of patients experiencing FRI, PJI or osteomyelitis, there were interesting trends at the time of diagnosis. Those with elevated levels of antibodies specific for a range of S. aureus antigens would progress to successful therapeutic outcomes. In contrast, those likely to suffer poor outcomes including arthrodesis, amputation and septic death tended to express lower levels of these same antibodies. In this regard, the higher levels of antibodies specific for the autolysin enzymes (Amd and Gmd), the toxin/immune evasion proteins (Hla, SCIN and CHIPS) and one of the Isd proteins (IsdH) were each significant predictors of ultimate infection control. In contrast, the levels of antibodies specific for IsdA and IsdB were not. Simple sums of IgG levels specific for certain groups, e.g., the toxin/immune evasion proteins or the Atl proteins were strong predictors of outcome. Even the simple sum of IgG levels to the eight antigens was a significant predictor of positive outcome.

At the six and twelve months timepoints, the predictive values of these same IgG levels reverse.

Upon successful intervention, the infection has been controlled and, in most patients, for most antigens, antibody levels remain the same or modestly decline at the 6-month and 12-month timepoints. However, for patients whose infection remains unresolved the levels of some antibodies rise. Specifically, levels of IgG specific for IsdB remain essentially unchanged while IgG antibodies specific for the autolysin subunit Gmd significantly increase. Thus, at the time of infection, elevation of anti-Gmd is a positive predictor of successful outcome17, but at later time points further increases in the levels of anti-Gmd correlate with poor outcomes. This is seen in the Odds Ratio calculations that show that high anti-Gmd IgG levels at the time of diagnosis are predictors of positive outcome; in contrast, high anti-Gmd IgG levels at 6 or 12 months are associated with poor outcomes.

The ratio of anti-Isd and anti-Atl IgG levels could provide a prognostic measure of likely outcome.

Because absolute concentrations of antibody levels are difficult to define and because prior analysis of patients is likely to be unavailable, we have explored the usefulness of internal ratios of antibody levels that may correlate with patient outcome. Based on our prior experience with antibodies that recognize the Isd antigens and are associated with poor outcomes and anti-autolysin antibodies that are associated with successful healing, we examined the ratios of anti-Isd to anti-Atl. In a newly infected patient, anti-Isd levels rise and remain at the same elevated level for the following year in all patients. In contrast, anti-Atl antibodies rise at the onset of infection and remain at the same level for the infection-controlled patients, but they continue to increase in patients who will suffer adverse outcomes. Thus, a low ratio of the anti-Isd to anti-Atl responses could provide an index of risk for poor outcome among patients with unresolved infections. In infection-controlled patients, the anti-IsdB:anti-Atl ratio would rise or remain unchanged throughout the one-year period of observation. In contrast, in the adverse outcome patients, the anti-Atl levels would rise (and the ratio with the anti-IsdB would shrink) providing an internally referenced measure of ongoing infection. In this patient cohort, this simple measure associated with possible outcome although not with compelling statistical power (p=0.105).

Limitations.

Sample numbers were insufficient to support comparisons among FRI, PJI and OM groups.

The great strength of this study is the extraordinary AO Trauma CPP Bone Infection registry of serum samples collected during the first year following primary infection in nearly two hundred patients worldwide. This collection also has internal complexity indicated in the results section: 53% of patients had FRI, 34% had PJI and 13% had implant-free osteomyelitis. Attempts to do comparisons among these subgroups suffered from insufficient statistical power due to small numbers in key groups. For example, more than 60% of FRI patients experience resolution of infection20 and display declining antibody levels in the first year. In contrast, nearly 80% of PJI patients retain elevated IgG levels and even increase them at the 6- and 12-month timepoints. Even with this significant patient sample collection, there are too few patients in the adverse outcome PJI population to attain statistical significance.

Serum antibody levels have complexity that other analytes do not.

This study has been based on the levels of anti-S. aureus IgG antibodies present in the sera of infected patients. Even in the absence of infection, humans have high levels of anti-S. aureus IgG due to our co-existence with it as a commensal, essentially from the time of birth. This is, at least partially, why the analytic range is so broad (three orders of magnitude) and that large populations of patients are needed to confidently measure the relatively small elevations (2-to-5 fold) typically observed during infections.15

Future Studies.

The observations in this work focus on the use of serum antibody levels as plausible measures of the presence of and therapeutic success in treating orthopaedic infections. However, they lack the sensitivity and specificity to meet clinical needs. To better understand the utility of antibody-based tools for assessing the state of orthopaedic infections, and particularly those caused by S. aureus, we plan to: 1) focus on distinct populations of patients experiencing orthopaedic infections (e.g., FRI, PJI, osteomyelitis, diabetic foot infections and septic arthritis); and 2) examine the emergence of recently activated circulating plasmablasts as plausible biomarkers for diagnosis and/or tracking of the resolution of active S. aureus infections.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NIH NIAMS P30 AR069655, P50 AR07200, and AO Trauma Clinical Priority Program, NIH 1UL1TR002649 (SLK), AO Trauma Clinical Priority Program Fellowship (GM), and NIH NIAID R21 AI119646 (JLD).

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

JLD is a cofounder of MicroB-plex, Inc. (Atlanta, GA.) and works there part-time. The other authors have no financial conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Schwarz EM, Parvizi J, Gehrke T, et al. 2019. 2018 International Consensus Meeting on Musculoskeletal Infection: Research Priorities from the General Assembly Questions. J Orthop Res 37:997–1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tande AJ, Patel R. 2014. Prosthetic joint infection. Clinical microbiology reviews 27:302–345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stulberg JJ, Delaney CP, Neuhauser DV, et al. 2010. Adherence to surgical care improvement project measures and the association with postoperative infections. Jama 303:2479–2485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Depypere M, Morgenstern M, Kuehl R, et al. 2020. Pathogenesis and management of fracture-related infection. Clin Microbiol Infect 26:572–578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Govaert GAM, Kuehl R, Atkins BL, et al. 2020. Diagnosing Fracture-Related Infection: Current Concepts and Recommendations. J Orthop Trauma 34:8–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kates SL, Tornetta P 3rd. 2020. Commentary on Secondary Fracture Prevention: Consensus Clinical Recommendations From a Multistakeholder Coalition Originally Published in the Journal of Bone and Mineral Research. J Orthop Trauma 34:221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goodson KM, Kee JR, Edwards PK, et al. 2020. Streamlining Hospital Treatment of Prosthetic Joint Infection. J Arthroplasty 35:S63–S68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kaplan SL. 2014. Recent lessons for the management of bone and joint infections. The Journal of infection 68Suppl 1:S51–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Assis LM, Nedeljkovic M, Dessen A. 2017. New strategies for targeting and treatment of multi-drug resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Drug Resist Updat 31:1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fowler VG Jr., Proctor RA. 2014. Where does a Staphylococcus aureus vaccine stand? Clin Microbiol Infect 20Suppl 5:66–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Proctor RA. 2019. Immunity to Staphylococcus aureus: Implications for Vaccine Development. Microbiol Spectr 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miller LS, Fowler VG, Shukla SK, et al. 2019. Development of a vaccine against Staphylococcus aureus invasive infections: Evidence-based on human immunity, genetics, and bacterial evasion mechanisms. FEMS Microbiol Rev. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fowler VG, Allen KB, Moreira ED, et al. 2013. Effect of an investigational vaccine for preventing Staphylococcus aureus infections after cardiothoracic surgery: a randomized trial. Jama 309:1368–1378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nishitani K, Ishikawa M, Morita Y, et al. 2020. IsdB antibody-mediated sepsis following S. aureus surgical site infection. JCI Insight 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nishitani K, Beck CA, Rosenberg AF, et al. 2015. A Diagnostic Serum Antibody Test for Patients With Staphylococcus aureus Osteomyelitis. Clin Orthop Relat Res 473:2735–2749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee CC, Southgate RD, Jiao C, et al. 2020. Deriving a dose and regimen for anti-glucosaminidase antibody passive-immunisation for patients with Staphylococcus aureus osteomyelitis. Eur Cell Mater 39:96–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kates SL, Owen JR, Beck CA, et al. 2020. Lack of Humoral Immunity Against Glucosaminidase Is Associated with Postoperative Complications in Staphylococcus aureus Osteomyelitis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Masters EA, Trombetta RP, de Mesy Bentley KL, et al. 2019. Evolving concepts in bone infection: redefining “biofilm”, “acute vs. chronic osteomyelitis”, “the immune proteome” and “local antibiotic therapy”. Bone Research 7:20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gedbjerg N, LaRosa R, Hunter JG, et al. 2013. Anti-glucosaminidase IgG in sera as a biomarker of host immunity against Staphylococcus aureus in orthopaedic surgery patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am 95:e171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morgenstern M, Erichsen C, Militz M, et al. 2020. The AO trauma CPP bone infection registry: Epidemiology and outcomes of Staphylococcus aureus bone infection. J Orthop Res. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oh I, Muthukrishnan G, Ninomiya MJ, et al. 2018. Tracking Anti-Staphylococcus aureus Antibodies Produced In Vivo and Ex Vivo during Foot Salvage Therapy for Diabetic Foot Infections Reveals Prognostic Insights and Evidence of Diversified Humoral Immunity. Infection and immunity 86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Muthukrishnan G, Soin S, Beck CA, et al. 2020. A Bioinformatic Approach to Utilize a Patient’s Antibody-Secreting Cells against Staphylococcus aureus to Detect Challenging Musculoskeletal Infections. Immunohorizons 4:339–351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.