Abstract

Introduction:

Lipid-lowering therapy effectively decreases cardiovascular risk on a population level, but it remains difficult to identify an individual patient’s personal risk reduction while following guideline directed medical therapy, leading to overtreatment in some patients and cardiovascular events in others. Recent improvements in cardiac CT technology provide the ability to directly assess an individual’s atherosclerotic disease burden, which has the potential to personalize risk assessment for lipid-lowering therapy.

Areas Covered:

We review the current unmet need in identifying patients at elevated residual risk despite guideline directed medical therapy, the evidence behind plaque regression as a potential marker of therapeutic response, and highlight state-of-the-art advances in coronary computed tomographic angiography (CCTA) for measurement of quantitative and qualitative changes in coronary atherosclerosis over time. Literature search was performed using PubMed and Google Scholar for literature relevant to statin therapy and residual risk, coronary plaque regression measurement, and CCTA assessment of quantitative and qualitative change in coronary atherosclerosis.

Expert Commentary:

We discuss the potential ability of CCTA to guide lipid-lowering therapy as a bridge between population and personalized medicine in the future, as well as the potential barriers to its use.

1. Introduction

Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) is the leading cause of death and disability worldwide.1 Despite improvement in therapy, mortality from ASCVD remains high, currently accounting for approximately one in seven deaths.2 Lipid-lowering therapy significantly reduces mortality at the population level, but many events still occur in individuals despite appropriate guideline directed medical therapy.3 We currently have no reliable way to identify patients at higher residual risk. Anti-atherosclerotic medical therapy leads to stabilization and regression of coronary plaques as demonstrated by invasive quantitative coronary angiography and intravascular ultrasound (IVUS). Plaque regression is associated with improved outcomes.4, 5 However, IVUS is invasive and thus not practical for the individual with only moderate cardiovascular risk. Coronary computed tomographic angiography (CCTA) is the most promising noninvasive method that has the potential to fully phenotype an individual’s coronary artery plaque volume (Figures 1, 2). Direct visualization of disease regression by coronary computed tomographic angiography (CCTA) has the potential to identify these patients and provide personalized risk assessment.

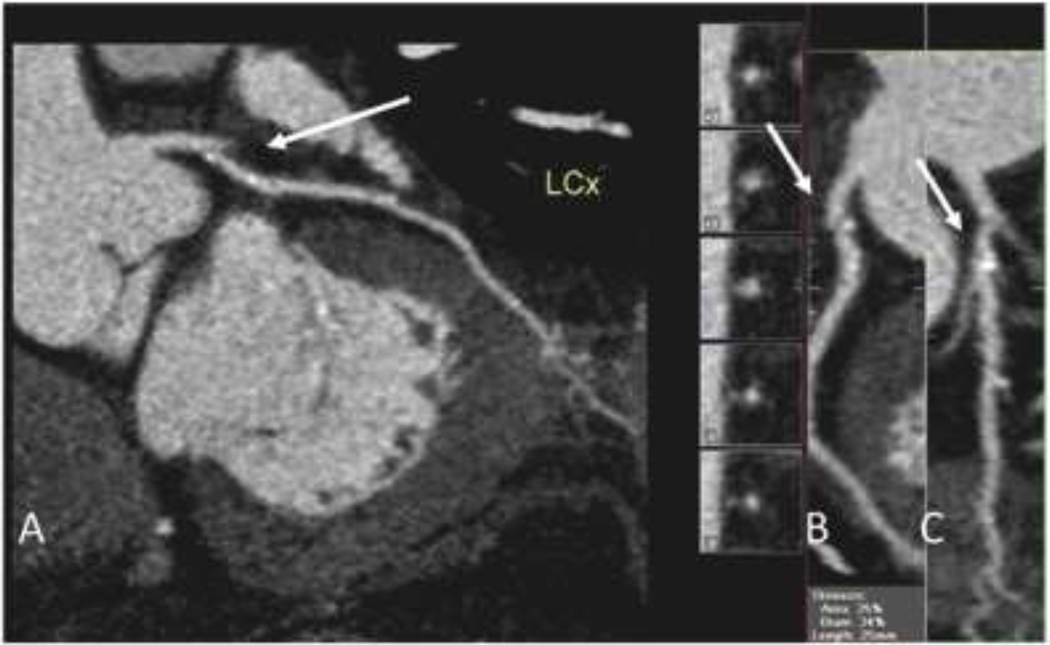

Figure 1.

72 year-old asymptomatic male with hyperlipidemia and a 10-year ASCVD risk, estimated with the Pooled Cohort Equations of 7.5%. A. CCTA images of the left circumflex artery showing mild atherosclerotic plaque (arrow). B, C: Multiple views of the proximal left circumflex artery showing small, proximal plaque (arrows). The patient was treated with 10 mg of atorvastatin. Eight years later, he presented with myocardial infarction due to high-grade stenosis in the same arterial distribution of the left circumflex artery.

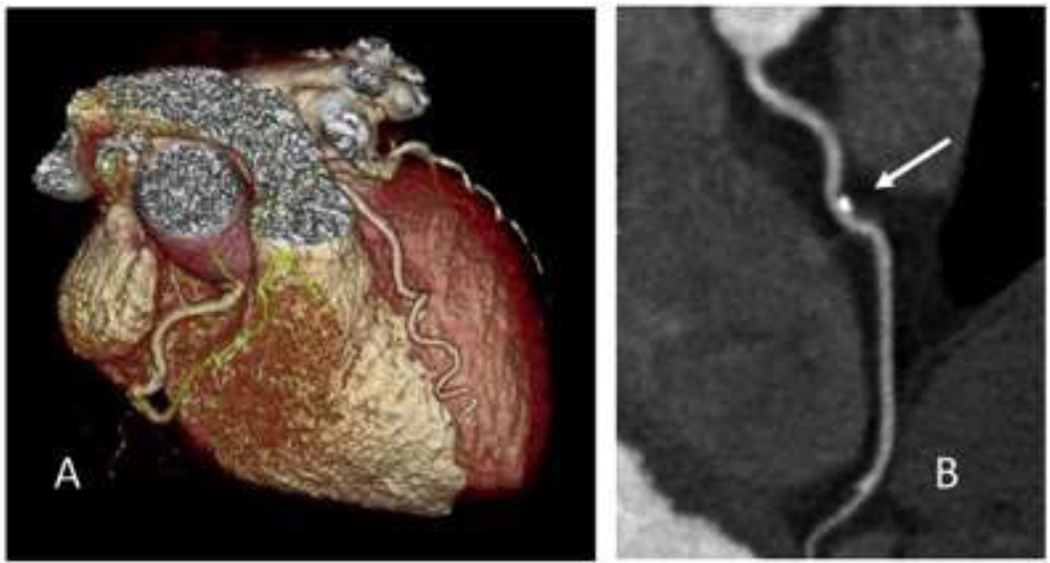

Figure 2.

63 year-old asymptomatic male referred for coronary CT assessment. A. Volume rendering of the coronary arteries. B. A small eccentric plaque (arrow) with calcified and non-calcified components is seen on detailed image of the left anterior descending artery.

In this review we summarize the current evidence regarding lipid-lowering therapy, quantitative and qualitative assessment of coronary atherosclerosis for cardiac risk, and the potential of coronary computed tomographic angiography for assessment of coronary atherosclerosis within individual patients. Current guideline directed medical therapy is effective in reducing cardiovascular risk in the population-level. We highlight the unmet need for reduction of residual risk and conceive of a personalized approach for lipid-lowering therapy, guided by therapeutic response in coronary plaque visualized by CCTA. We review both the strengths and the shortcomings of lipid-lowering therapy, and frame these in light of new advances in non-invasive imaging of ASCVD to draw attention to the new possibilities within the field of preventive cardiology.

2. The Unmet Need of Residual Risk in Lipid-Lowering Therapy

Lipid-lowering therapy decreases the population rate of primary and secondary ASCVD events, but events still occur despite therapy. Statins are the primary form of lipid lowering therapy, as they are effective in nearly all at-risk patients (TABLE 1).6, 7 Statins decrease relative risk of major adverse cardiac events (MACE) by 20–45%. Thus, 55–80% residual risk for MACE remains for patients, despite statin therapy that may last for 20 or more years of their adult life.3 This residual risk could potentially be minimized by intensification of lipid-lowering therapy or initiation of non-statin medications, but these approaches are not without drawbacks. High doses of statins may be less well tolerated or have potential side effects, with statin intolerance occurring in up to 15% of patients.8 Medications such as bile acid sequestrants and ezetimibe also have potential side effects such as gastrointestinal discomfort while Proprotein Convertase Subtilisin/Kexin Type 9 (PCSK9) inhibitors are currently cost-prohibitive for a broad population.9

Table 1:

Summary of selected statin trials.

| Trial | N | Control | Intervention | Primary Outcome | Follow up Time (Years) | Control Primary Outcome (%) | Intervention Primary Outcome (%) | NNT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4S | 4444 | Placebo | Simvastatin 10–40mg | Total mortality | 5.4 | 12.0% | 8.0% | 25 |

| WOSCOPS | 6595 | Placebo | Pravastatin 40mg | Nonfatal MI and death from CHD | 4.9 | 7.9% | 5.5% | 42 |

| CARE | 4159 | Placebo | Pravastatin 40mg | Nonfatal MI and death from CHD | 5.0 | 13.2% | 10.2% | 33 |

| AFCAPS/TexCAPS | 6605 | Placebo | Lovastatin 20–40mg | Incidence of First MACE | 5.2 | 5.5% | 3.5% | 50 |

| LIPID | 9014 | Placebo | Pravastatin 40mg | CHD Mortality | 6.1 | 8.3% | 6.4% | 53 |

| MIRACL | 3086 | Placebo | Atorvastatin 80mg | All-Cause Mortality + MACE +Angina | 0.3 | 17.4% | 14.8% | 38 |

| HPS | 20536 | Placebo | Simvastatin 40mg | Total Mortality | 5.0 | 14.7% | 12.9% | 56 |

| PROSPER | 5804 | Placebo | Pravastatin 40mg | Time to First MACE | 3.2 | 16.2% | 14.1% | 48 |

| ALLHAT-LLT | 10335 | Placebo | Pravastatin 40mg | All-Cause Mortality | 4.8 | 15.3% | 14.9% | 250 |

| FLORIDA | 540 | Placebo | Fluvastatin 80mg | Ischemia + All-Cause Mortality + MACE | 1.0 | 36.0% | 33.0% | 33 |

| LIPS | 1677 | Placebo | Fluvastatin 80mg | MACE + Revascularization | 3.9 | 27.0% | 21.0% | 17 |

| ASCOT-LAA | 10305 | Placebo | Atorvastatin 10mg | Nonfatal MI and death from CHD | 3.3 | 3.0% | 1.9% | 91 |

| ALLIANCE | 2442 | Placebo | Atorvastatin titrated (LDL-C<80mg/dL) | Time to First MACE | 4.3 | 27.7% | 23.7% | 25 |

| CARDS | 2838 | Placebo | Atorvastatin 10mg | Time to First MACE | 3.9 | 9.0% | 5.8% | 31 |

| PROVE IT-TIMI 22 | 4162 | Pravastatin 40mg | Atorvastatin 80mg | All-Cause Mortality + MACE | 2.0 | 26.3% | 22.4% | 26 |

| PACT | 3408 | Placebo | Pravastatin 20–40mg | All-Cause Mortality + MACE | 0.1 | 12.4% | 11.6% | 125 |

| A to Z | 4497 | Placebo followed by Simvastatin 20mg | Simvastatin 40mg followed by 80mg | MACE + Stroke | 2.0 | 16.7% | 14.4% | 43 |

| TNT | 10001 | Atorvastatin 10mg | Atorvastatin 80mg | MACE | 4.9 | 10.9% | 8.7% | 45 |

| IDEAL | 8888 | Simvastatin 20mg | Atorvastatin 80mg | MACE | 4.8 | 10.4% | 9.3% | 91 |

| ASPEN | 2410 | Placebo | Atorvastatin 10mg | MACE | 4.0 | 15.0% | 13.7% | 77 |

| MEGA | 7832 | Placebo | Pravastatin 10–20mg | MACE | 5.3 | 2.5% | 1.7% | 125 |

| JUPITER | 17802 | Placebo | Rosuvastatin 20mg | Time to First MACE | 1.9 | 2.8% | 1.6% | 83 |

| SEARCH | 12064 | Simvastatin 20mg | Simvastatin 80mg | Major Vascular Events | 6.7 | 25.7% | 24.5% | 83 |

| IMPROVE-IT | 18144 | Simvastatin 40–80mg | Simvastatin 40–80mg + Ezetimibe 10mg | MACE + Revascularization + Stroke | 6.0 | 34.7% | 32.7% | 50 |

Trial = Abbreviated name of trial, N = Number of participants randomized, Control = Therapy used in control group, Intervention = Therapy used in intervention group, Primary Outcome = Primary outcome measured in trial, Follow up time = Average follow up time of patients in trial, Control Primary Outcome = Incidence of primary outcome in patients within control group, Intervention Primary Outcome = Incidence of primary outcome in patient within intervention group, NNT = Number needed to treat. 4S = Randomised trial of cholesterol lowering in 4444 patients with coronary heart disease: the Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study; WOSCOPS = Prevention of coronary heart disease with pravastatin in men with hypercholesterolemia; CARE = The effect of pravastatin on coronary events after myocardial infarction in patients with average cholesterol levels; AFCAPS/TexCAPS = Primary prevention of acute coronary events with lovastatin in men and women with average cholesterol levels: results of AFCAPS/TexCAPS; LIPID = Prevention of Cardiovascular Events and Death with Pravastatin in Patients with Coronary Heart Disease and a Broad Range of Initial Cholesterol Levels; MIRACL = Effects of Atorvastatin on Early Recurrent Ischemic Events in Acute Coronary Syndromes; HPS = MRC/BHF Heart Protection Study of cholesterol lowering with simvastatin in 20,536 high-risk individuals: a randomised placebo- controlled trial; PROSPER = Pravastatin in elderly individuals at risk of vascular disease (PROSPER): a randomised controlled trial; ALLHAT-LLT = Major outcomes in moderately hypercholesterolemic, hypertensive patients randomized to pravastatin vs usual care: The antihypertensive and lipid- lowering treatment to prevent heart attack trial; FLORIDA = Effect of fluvastatin on ischaemia following acute myocardial infarction; LIPS = Fluvastatin for Prevention of Cardiac Events Following Successful First Percutaneous Coronary Intervention; ASCOT-LAA = Prevention of coronary and stroke events with atorvastatin in hypertensive patients who have average or lower-than-average cholesterol concentrations, in the Anglo-Scandinavian Cardiac Outcomes Trial-Lipid Lowering Arm; ALLIANCE = Clinical outcomes in managed-care patients with coronary heart disease treated aggressively in lipid-lowering disease management clinics; CARDS = Primary prevention of cardiovascular disease with atorvastatin in type 2 diabetes in the Collaborative Atorvastatin Diabetes Study; PROVE IT-TIMI 22 = Intensive versus Moderate Lipid Lowering with Statins after Acute Coronary Syndromes; PACT = Effect of pravastatin compared with placebo initiated within 24 hours of onset of acute myocardial infarction or unstable angina; A to Z = Early intensive vs a delayed conservative simvastatin strategy in patients with acute coronary syndromes: phase Z of the A to Z trial; TNT = Intensive Lipid Lowering with Atorvastatin in Patients with Stable Coronary Disease; IDEAL = High-Dose Atorvastatin vs Usual-Dose Simvastatin for Secondary Prevention After Myocardial Infarction; ASPEN = The Atorvastatin Study for Prevention of Coronary Heart Disease; MEGA = Primary prevention of cardiovascular disease with pravastatin in Japan; JUPITER = Rosuvastatin to Prevent Vascular Events in Men and Women with Elevated C-Reactive Protein; SEARCH = Intensive lowering of LDL cholesterol with 80 mg versus 20 mg simvastatin daily in 12,064 survivors of myocardial infarction; IMPROVE-IT = Ezetimibe Added to Statin Therapy after Acute Coronary Syndromes.

2.1. Residual Risk in Patients on Guideline-Directed Medical Therapies

We do not currently have effective biomarkers to risk stratify and detect patients with elevated residual risk. Genetic, epidemiologic data, or established risk factors have not identified single strongly predictive biomarkers of residual risk. A diverse range of epidemiological factors have been described as contributing to risk of MACE despite adequate therapy including age, body mass index, sex, hypertension, baseline apolipoprotein B, blood urea nitrogen, smoking, prior cardiovascular disease, calcium channel blocker use, statin dose, aspirin use, and baseline apolipoprotein A-I. Post-treatment LDL-C was notably not associated with residual risk.10–12 Genetic factors related to ASCVD events in patients on statin therapy include mutations in SCARB1 and PSCK9, but while these were statistically significant, their clinical relevance has yet to be demonstrated.13

Failure of statins to reduce LDL-C levels to the expected degree occurrs in approximately twenty percent of the patients in major clinical trials,14 and has been linked to multiple mutations in the HMG-CoA reductase gene.15 But even when the target expected tolerated dose or goal LDL-C level is achieved, the number needed to treat to prevent primary outcomes in most major statin trials ranged from 25 to >100 (Table 1). These factors reveal a currently unmet need for more effective identification of patients at elevated risk of ASCVD events despite guideline directed medical therapy. Given the inability to determine risk through surrogate markers, direct visualization of coronary disease may be more effective.

3. Regression in Coronary Plaque as a Marker of Therapeutic Response

Atherosclerotic plaque is the substrate of ASCVD, and therefore evaluation of atherosclerotic plaque may provide a strong marker of disease status and therapeutic response. Plaque progression evaluated across different modalities, such as carotid intimal medial thickness,16 coronary artery calcification,17 and non-calcified coronary plaque18–20 is a universal indicator of poor prognosis. Conversely, plaque regression measured by IVUS is correlated with decreased MACE.4

3.1. Plaque Regression with Lipid-Lowering Therapy

Regression of coronary plaque burden after treatment with statins has been extensively studied in trials using IVUS (TABLE 2). Most trials have examined change in normalized quantity of plaque by change in percent atheroma volume (ΔPAV%). There is a linear relationship between ΔPAV% and post-treatment LDL-C level; however, LDL-C is a limited predictor of plaque response, as the association between LDL-C and change in plaque over time measured by IVUS is weakly correlated (r=0.41).21, 22 In meta-analyses examining for associations between ΔPAV% and outcomes, ΔPAV% reduction is strongly associated with reduced MI or revascularization23, and MACE.24 Although these analyses suggest that plaque regression is associated with improved outcomes, IVUS results are difficult to generalize, as trials included were typically of patients referred to cardiac catheterization, a high-risk population.

Table 2:

Lipid-lowering trials with IVUS measurement of volumetric change in plaque. Results are presented as mean ± standard deviation or median (interquartile range).

| Trial | N | Medication | Follow up Time (months) | LDL-C Pre (mg/dL) | LDL-C Post (mg/dL) | Change in Plaque Atheroma Volume (%) | Change in Total Atheroma Volume (mm3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GAIN | 99 | Atorvastatin titrated (LDL-C<100mg/dL) | 12 | 155.0±34.0 | 86.0±30.0 | NR | 1.2±30.4* |

| REVERSAL | 249 | Pravastatin 40mg | 18 | 150.2±25.9 | 110±25.8 | 1.6% (1.2 to 2.2) | 4.4 (0.1 to 6.0) |

| REVERSAL | 253 | Atorvastatin 80mg | 18 | 150.2±27.9 | 79.0±30.2 | 0.2% (−0.3 to 0.5) | −0.9 (−3.5 to 1.6) |

| ESTABLISH | 48 | Atorvastatin 20mg | 6 | 124.6±34.5 | 70.0±25.0 | NR | −8.3±9.0* |

| ASTEROID | 349 | Rosuvastatin 40mg | 24 | 130.4±34.3 | 60.8±20.0 | −0.8% (−1.2 to −0.5) | −5.6 (−6.8 to −4.0) |

| JAPAN-ACS | 125 | Pivastatin 4mg | 9.3 | 130.9±33.3 | 81.1±23.4 | NR | −8.7±8.2 |

| JAPAN-ACS | 127 | Atorvastatin 20mg | 9.6 | 133.8±31.4 | 84.1±27.4 | NR | −9.8±8.6 |

| COSMOS | 126 | Rosuvastatin 2.5–20mg | 17.4 | 140.2±31.5 | 82.9±18.7 | NR | −5.3(−7.6 to −2.6)* |

| TWINS | 20 | Atorvastatin titrated (LDL-C<100mg/dL) | 5.5 | 146.2±28.8 | 85.7±18.2 | NR | −12.1 (NR)* |

| TWINS | 20 | Atorvastatin titrated (LDL-C<100mg/dL) | 18.4 | 146.2±28.8 | 87.9±15.8 | NR | −25.4 (NR)* |

| TOGETHAR | 46 | Pivastatin 2mg | 11.9 | 145±24.0 | 93.6±22.6 | −0.1% (−1.2 to 1.0) | NR |

| SATURN | 519 | Atorvastatin 80mg | 23.9 | 119.9±28.9 | 70.2±1.0 | −1.0% (−1.19 to −0.6) | −4.4 (−6.0 to −3.3) |

| SATURN | 520 | Rosuvastatin 40mg | 23.9 | 120.0±27.3 | 62.6±1.0 | −1.2% (−1.5 to −0.9) | −6.4 (−7.5 to −5.1) |

| IBIS-4 | 82 | Rosuvastatin 40mg | 13 | 127.0 (107.0–145.0) | 73.3 (62.0–90.0) | −0.9% (−1.6 to −0.3) | −7.7 (−9.9 to −5.6) |

| PRECISE IVUS | 100 | Atorvastatin titrated (LDL-C<70mg/dL) + Ezetimibe 10mg | 10.1 | 109.8±25.4 | 63.2±16.3 | −1.4% (−3.4 to −0.1) | −5.3 (−12.4 to 0.1) |

| PRECISE IVUS | 102 | Atorvastatin titrated (LDL-C<70mg/dL) | 9.7 | 108.3±26.3 | 73.3±20.3 | −0.3% (−1.9 to 0.9) | −1.2 (−5.7 to 3.3) |

| GLAGOV | 846 | Evolocumab 420mg + Statin | 18 | 92.6 (90.1–95.0) | 36.6 (34.5–38.8) | −0.76% (−1.9 to 0.4) | −4.3 (−15.6 to 7.0) |

Trial = Abbreviated name of trial, N = Number of participants with analyzable serial IVUS examinations, Medication = Drug used trial arm, Follow up Time = Mean time between first and second intravascular ultrasound measurement, LDL-C Pre = Low Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol level prior to initiation of drug therapy ± standard deviation or (95% confidence interval), LDL-C Post = Low Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol level at time of follow up ± standard deviation or (95% confidence interval), Change in Plaque Atheroma Volume = Percent change in average area of vessel occupied by atheroma ± standard deviation or (95% confidence interval), Change in Total Atheroma Volume = Change in total plaque volume measured and normalized to length ± standard deviation or (95% confidence interval). NR=Not Recorded,

Total atheroma volume not normalized to length.

GAIN = Use of Intravascular Ultrasound to Compare Effects of Different Strategies of Lipid-Lowering Therapy on Plaque Volume and Composition in Patients With Coronary Artery Disease; REVERSAL = Effect of intensive compared with moderate lipid-lowering therapy on progression of coronary atherosclerosis: a randomized controlled trial; ESTABLISH = Demonstration of the Beneficial Effect on Atherosclerotic Lesions by Serial Volumetric Intravascular Ultrasound Analysis During Half a Year After Coronary Event; ASTEROID = Effect of Very High-Intensity Statin Therapy on Regression of Coronary Atherosclerosis; JAPAN-ACS = Effect of Intensive Statin Therapy on Regression of Coronary Atherosclerosis in Patients With Acute Coronary Syndrome; COSMOS = Effect of Rosuvastatin on Coronary Atheroma in Stable Coronary Artery Disease Multicenter Coronary Atherosclerosis Study Measuring Effects of Rosuvastatin Using Intravascular Ultrasound in Japanese Subjects; TWINS = Qualitative and quantitative changes in coronary plaque associated with atorvastatin therapy; TOGETHAR = Stabilization and Regression of Coronary Plaques Treated With Pitavastatin Proven by Angioscopy and Intravascular Ultrasound; SATURN = Effect of Two Intensive Statin Regimens on Progression of Coronary Disease; IBIS-4 = Effect of high-intensity statin therapy on atherosclerosis in non-infarct-related coronary arteries (IBIS-4): a serial intravascular ultrasonography study; PRECISE IVUS = Impact of Dual Lipid-Lowering Strategy With Ezetimibe and Atorvastatin on Coronary Plaque Regression in Patients With Percutaneous Coronary Intervention; GLAGOV = Global Assessment of Plaque Regression With a PCSK9 Antibody as Measured by Intravascular Ultrasound.

3.2. Heterogeneity of Plaque Regression Response

IVUS data is very revealing regarding the overall effect of statins, but the response of atherosclerotic plaque to statin therapy within treatment groups is heterogeneous. In patients receiving a “regression-dose” statin, there are subsets of patients who experience progression and subsets that experience regression of atherosclerotic plaque, in approximately a 1:2 ratio. The lack of homogenous response to statin therapy is present even in patients with extremely low LDL-C: more than 20% of patients with LDL-C≤70 mg/dL continue to have progression over time in pooled analysis of IVUS studies. Lower amount of plaque at baseline, presence of diabetes, elevated systolic blood pressure, and less responsive HDL-C and apolipoprotein-B levels are weakly associated with progression of atherosclerotic plaque.25 Plaque regression with statin therapy also varies with sex, with women having on average significantly more plaque regression than men when LDL-C is lowered to <70mg/dL.26

Invasive observation of qualitative structural changes of individual coronary plaques (as opposed to quantitative ΔPAV%) in vivo is feasible but there are currently no studies evaluating associations of these changes with clinical outcomes. Invasive optical coherence tomography and near-infrared spectroscopy have the ability to visualize increase in cap thickness of high-risk lesions such as thin-capped fibroatheroma (TCFA) and decrease in lipid content in single lesions.27–29 Coronary angioscopy visualizes decrease in necrotic core content.30, 31 IVUS shows normalization of remodeling index at lesion locations,32 reduction in fibro-fatty lesion content, increased calcification, and resolution of pathological intimal thickening lesions.33, 34 There is currently no readily available single diagnostic modality to evaluate for all of the above parameters, but these qualitative changes have been associated with quantitative plaque regression.33 Given the correlation with regression, observation of reduction in plaque burden may be an effective way to measure overall successful response to therapy.

4. Cardiac Computed Tomography (CT) for Coronary Disease Assessment

Cardiac CT can be used for evaluation of coronary plaque burden and morphology with technical ease, good reproducibility, low cost, and high data acquisition speed. Cardiac CT has historically had a role in risk stratification using the Coronary Artery Calcification Score (CAC). CAC is strongly associated with cardiovascular risk in multiple cohorts35–39 The combination of CAC with traditional risk factors in MESA significantly improved risk prediction over prior models,40 and a CAC score of zero is one of the best predictors of low cardiac risk.41 Although CAC is used to effectively refine cardiovascular risk, once coronary calcification is initiated, it follows a predictable pattern of progression,42 with no consistent evidence of the ability to regress in response to therapy.43 CAC appears to have no role in evaluating therapeutic response or change in atherosclerotic disease over time.

Coronary CT angiography (CCTA) on the other hand may be better situated to measure changes in non-calcified plaque over time. Non-calcified plaque can progress or regress in response to lipid lowering therapy across different levels of baseline CAC.44 CCTA reliably measures the overall plaque burden, differentiates plaque subtypes,45, 46 and identifies high-risk plaques47. With evolution of technology, the diagnostic accuracy of CCTA has increased. Early CCTA had 85% sensitivity and 90% specificity in identifying stenosis >50% compared to invasive angiography.48 Contemporary CCTA modalities are essentially equivalent to invasive angiography in detecting hemodynamically significant lesions.49

New CCTA techniques can also evaluate the physiologic and functional significance of plaques. CT perfusion can identify perfusion defects similarly to nuclear stress testing.50 Non-invasive fractional flow reserve (FFR) using CCTA has been FDA approved and correlates well with invasive FFR.51 New imaging methods such as dual energy CT and photon-counting CT will allow for material decomposition, which is the ability to identify, differentiate, and quantify fat, fibrosis, calcium, and iodine. However, widespread adoption of cardiac CT has yet to occur. The 2010 appropriate use criteria limit CCTA use to low and intermediate risk patients in the setting of uncertain alternative diagnostics.52

4.1. Modern Plaque Assessment by Coronary Computed Tomographic Angiography

Early CCTA technology was hampered by low resolution, high radiation dose, and limited reproducibility. In modern CCTA modalities, spatial resolution has improved, while radiation dose has decreased due to single-heartbeat acquisition using multi-detector CT (up to 320 detectors), imaging gating strategies and advanced reconstruction algorithms. Radiation dose with CCTA had previously been similar to or greater than cardiac catheterization (10–15 mSv), but technical developments have greatly reduced the typical radiation dose associated with CCTA (commonly 2–5 mSv).53 The reliability of CCTA has improved,45, 54 and even ultra-low, sub-millisievert (<1 mSv) radiation dose CCTA techniques are becoming available.55

Similar to invasive studies, analysis of coronary plaque by CCTA for risk assessment may be divided into two different approaches: (1) qualitative assessment of plaque features thought to be “high risk”; this approach has mostly been applied to patients seen in the emergency department setting; and (2) quantitative measurement of total coronary plaque burden. Both qualitative and quantitative CCTA parameters can follow changes in non-calcified plaque over time and could be used to monitor response to treatment. Compared to IVUS, CCTA is non-invasive and has a lower cost. Anatomic-landmark-based 3D coregistration between multiple timepoints may be more accurate than the length-based 2D measurement by IVUS. While initial experience in 2007 comparing CCTA to IVUS showed systemic but reproducible underestimation of lumen and vessel size,56 current CCTA-based plaque volume measurements are strongly correlated with IVUS in an expert reader-assisted method (r= 0.94) and fully automatic method (r=0.84).57 The reproducibility of CCTA for plaque burden has recently been defined.58

4.2. Qualitative High Risk Features of Coronary Plaque

Plaque attenuation on CCTA has been associated with histological composition from early experiments.59 Classic high-risk plaque features on CCTA include the “napkin-ring” sign, positive remodeling, low attenuation plaque, and spotty calcification. These features are associated with acute coronary syndrome (ACS) culprit lesions.60–62 The presence of these findings in patients presenting to the emergency department (ED) with chest pain is associated with a 9-fold higher probability of ACS independent of presence of significant coronary stenosis.63

The risk of ACS in patients with different CCTA findings was assessed in an observational cohort of more than 3,000 patients and 3.9 years of follow up. In this cohort, high-risk plaques were defined as positive remodeling and/or low attenuation plaques and significant stenosis was defined as > 70%. The presence of plaque without high-risk features on initial CCTA was associated with a 30% higher risk of ACS compared to the absence of plaque. The presence of significant stenosis alone was associated with a two-fold increase of ACS risk, while the presence of any high-risk feature was associated with a 13-fold increase. Coexistence of significant stenosis with high-risk plaque was associated with a 17-fold increase in ACS risk. Among 450 patients that received a follow-up CCTA, those with evidence of plaque progression (defined as worsening stenosis or positive remodeling) had a 33-fold increase in risk of ACS; the combination of plaque progression and high-risk plaque on original imaging was associated with a 70-fold increase. Notably, only four high risk plaques became non-high-risk plaque on follow up imaging.47

4.3. Quantitative Non-Invasive Measurement of Coronary Plaque Burden

The ability to identify high-risk features enhances the prognostic accuracy of cardiac CT. However, similar to CAC, identification of high-risk features currently lacks relevance for management or intervention. Global assessment of disease by plaque burden, with follow-up of global response may be better suited for assessment of therapeutic response, particularly in patients at earlier stages of disease. There are multiple methods of volumetric plaque quantification by CCTA, extensively reviewed.64

Non-calcified plaque burden is quantifiable by CCTA (Figures 3, 4 and 5) is associated with modifiable risk factors, predictive of future events, and modifiable over time. The quantity of total (calcified plus non-calcified) coronary plaque in an asymptomatic statin-eligible cohort was associated with male gender and prior statin dose, whereas non-calcified plaque burden was associated with modifiable risk factors such as systolic blood pressure, diabetes, and LDL-C level.65 The quantity of non-calcified plaque in non-obstructive lesions in a cohort of patients with NSTEMI was associated with recurrent ACS events in a multivariate analysis, while CAC and calcified plaque burden provided no additional predictive value.46 In an observational study of five hundred patients at intermediate risk of coronary artery disease, the presence of non-calcified plaques versus either calcified plaque or no plaque had a greater than 20-fold increase in risk of MACE.66

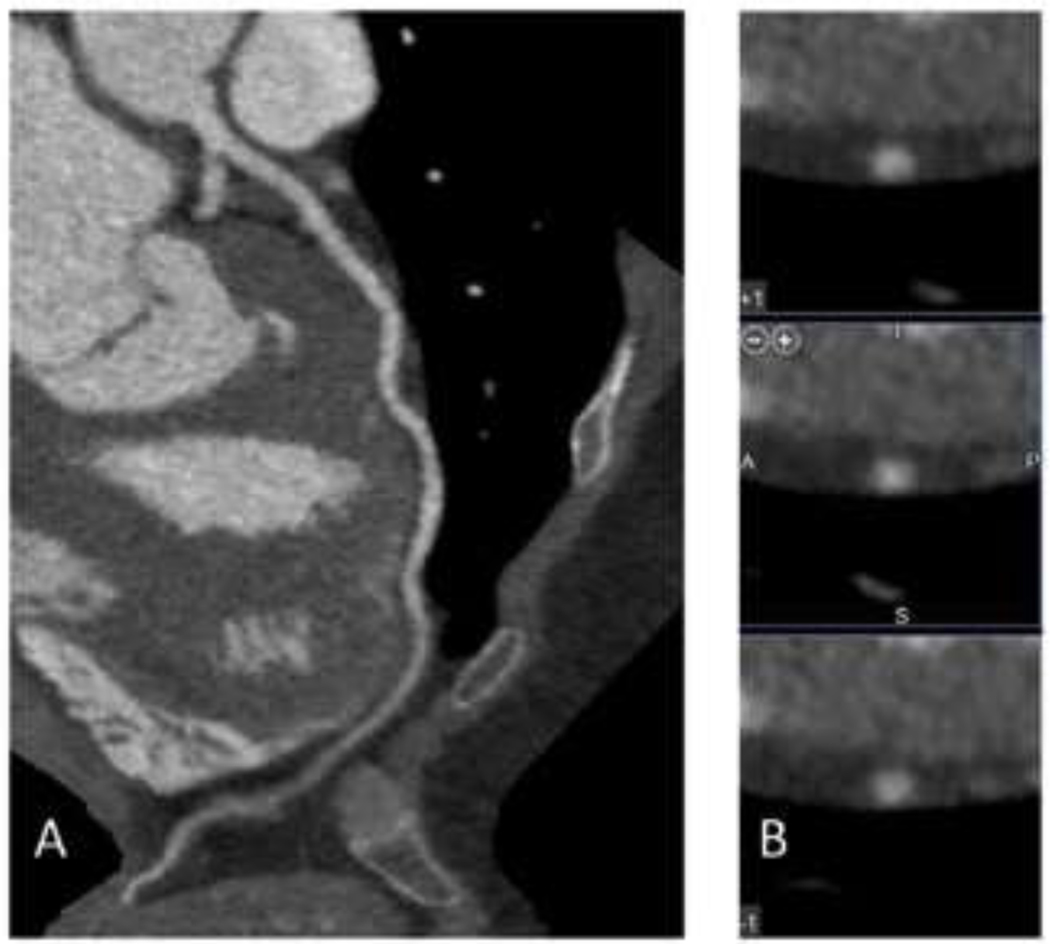

Figure 3.

75 year-old female with a 10-year ASCVD risk estimated by the Pooled Cohort Equations of 18%. No coronary artery disease was present on CCTA. A. Images of the left anterior descending coronary artery. B. Cross-section images of the left anterior descending coronary artery.

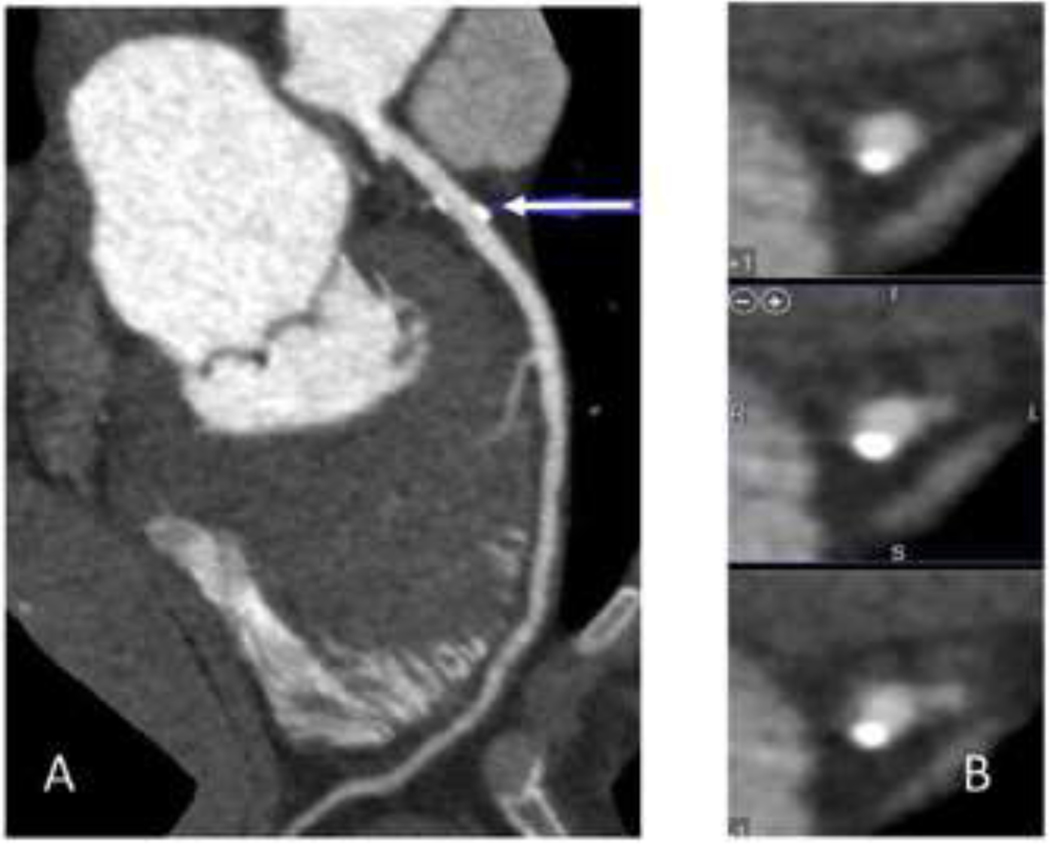

Figure 4.

68 year-old male with a 10-year ASCVD risk estimated by the Pooled Cohort Equations of 5%. Images of the left coronary artery. A. Longitudinal and B. cross-sectional views show a small plaque that is predominantly calcified.

Figure 5.

48 year-old male with elevated total cholesterol referred for coronary artery screening by CCTA. A. Longitudinal view of the left anterior coronary artery shows a large soft plaque in the mid artery. B. Cross section views of the same plaque show eccentric soft plaque surrounding the cross section of the coronary artery.

There have been a small number of trials with serial CCTA, looking at change over time (Table 3). Multiple studies show the ability of CCTA to accurately observe and quantify change in non-calcified plaque burden over time and development of high-risk features.67–70 Reduction in plaque with lipid-lowering therapy has also been accurately observed in small studies. In a small cohort of 32 patients, treatment with fluvastatin resulted in a reduction in plaque quantity and decrease in necrotic core volume in high risk areas as evaluated by CCTA.71 In a retrospective study of 100 patients referred to CCTA for known CAD, regression of non-calcified plaque in response to statin therapy was seen in patients receiving statin therapy compared to progression in those not on statin therapy (mean follow up, 400 days).72 An observational study with 147 patients with serial CCTA over two years was able to demonstrate decreasing LDL-C to <70mg/dL measurably attenuated plaque progression.73 The only randomized control trial using serial CCTA was in 40 HIV-infected patients with subclinical coronary atherosclerosis, low LDL-C, and aortic inflammation shown by PET imaging. Patients were randomized to atorvastatin versus placebo for duration of one year. After a year, serial CCTA and PET imaging showed reduced non-calcified plaque by CCTA, but no change in aortic inflammation by PET.74

Table 3:

Studies with serial CCTA scans

| Author | Year | N | Population | Time Interval (months) | Area Examined | CT Scanner | Analysis Type | Comparison Groups |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Burgstahler et al. | 2007 | 27 | Elevated CAD Risk | 16 | All plaques | 16/64-slice | Prospective | None |

| Schmid et al. | 2008 | 50 | Suspected CAD | 17 | Left Main, Proximal LAD | 64-slice | Retrospective | None |

| Lehman et al. | 2009 | 69 | Chest pain | 24 | All plaques | 64-slice | Prospective | None |

| Papadopoulou et al. | 2012 | 32 | ACS | 38 | All segments | 64-slice | Prospective | None |

| Ayad et al. | 2015 | 200 | Chest pain | 26 | All plaques | 64/128-slice | Retrospective | None |

| Hoffmann et al. | 2010 | 63 | PCP Ref erral | 25 | All plaques | 16/64-slice | Retrospective | Statin / No Statin |

| Inoue et al. | 2010 | 32 | Suspected CAD | 12 | 10 mm segment | 16/64-slice | Prospective | Fluvastatin use / no use |

| Zeb et al. | 2013 | 100 | Suspected CAD, consecutive studies | 13 | All plaques | 64-slice | Retrospective | Statin / No Statin |

| Ito et al. | 2014 | 148 | Chest pain | 12 | All plaques | 320-slice | Retrospective | Plaque non-progression / Progression |

| Lo et al. | 2015 | 37 | HIV with arterial inflammation and low LDL-C | 12 | All plaques | 128-slice | Randomized Control Trial | Atorvastatin use / no use |

| Motoyama et al. | 2015 | 449 | Known or suspected CAD | 12 | All plaques | 64/320-slice | Retrospective | ACS or no ACS |

| Shin et al. | 2017 | 147 | Plaque present on CCT A | 38 | All plaques | 64-slice | Retrospective | LDL above or below 70 |

Author = First author of manuscript, Year = Year of publication, N = Number of included participants with serial CCTA studies, Time Interval = Average duration between initial and follow up CCTA studies (months), Area Examined = Part of coronary tree included in analysis, CT Scanner = Number of CT slices in scanner or scanners used within study, Analysis Type = Prospective / Retrospective / Randomized Control Trial, Comparison Groups = Non-observational statistical analyses included within manuscript. Burgstahler et al. = Influence of a lipid-lowering therapy on calcified and noncalcified coronary plaques monitored by multislice detector computed tomography: results of the New Age II Pilot Study; Schmid et al. = Assessment of changes in non-calcified atherosclerotic plaque volume in the left main and left anterior descending coronary arteries over time by 64-slice computed tomography; Lehman et al. = Assessment of Coronary Plaque Progression in Coronary Computed Tomography Angiography Using a Semiquantitative Score; Papadopoulou et al. = Natural history of coronary atherosclerosis by multislice computed tomography; Ayad et al. = The Role of 64/128-Slice Multidetector Computed Tomography to Assess the Progression of Coronary Atherosclerosis; Hoffmann et al. = Influence of statin treatment on coronary atherosclerosis visualised using multidetector computed tomography; Inoue et al. = Serial coronary CT angiography- verified changes in plaque characteristics as an end point: evaluation of effect of statin intervention; Zeb et al. = Effect of statin treatment on coronary plaque progression-a serial coronary CT angiography study; Ito et al. = Characteristics of plaque progression detected by serial coronary computed tomography angiography; Lo et al. = Effects of statin therapy on coronary artery plaque volume and high-risk plaque morphology in HIV-infected patients with subclinical atherosclerosis: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial; Motoyama et al. = Plaque Characterization by Coronary Computed Tomography Angiography and the Likelihood of Acute Coronary Events in Mid- Term Follow-Up; Shin et al. = Impact of Intensive LDL Cholesterol Lowering on Coronary Artery Atherosclerosis Progression: A Serial CT Angiography Study.

The ability of CCTA to quantify changes in coronary atherosclerosis over time in response to therapy has the potential to improve our understanding of the significance of change in plaque on an individual’s ASCVD risk by non-invasive means though further research is needed. The combination of anatomical assessment through CAC, high-risk plaque features, and non-calcified plaque burden and assessment of the physiological significance of the plaque though CT perfusion and FFR-CT further expand the possibilities of cardiac CT for personalized medicine. Future developments in dual-energy and multi-energy CT will further expand diagnostic options while addressing previous technological limitations.

4.4. Limitations and Future Developments of Computed Tomography for Personalized Risk Assessment

The recent technical achievements within CCTA have been the main focus of this article, however the described potential use is far from a clinical reality, with multiple steps needed in order to move it forwards. Broadly speaking, outcomes data, large-scale trials, and randomized interventional data are all still necessary. There are both logistical and structural barriers to obtaining these data.

Our ability to prospectively observe the in vivo natural history of atherosclerosis in order to understand the relevance of changes in plaque quantity has traditionally been limited by the risks associated with obtaining these observations invasively. The PROSPECT trial utilizing IVUS was only performed in patients with acute coronary syndromes, already undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention.75 Based on high-risk patients, IVUS studies suggest that reduction of coronary plaque is correlated with lower event rates.23, 24 The data are relatively poor; primarily meta-analyses of multiple trial populations. At this point, it remains difficult to definitively state whether or not quantitative plaque progression is part of a causal pathway by which atherosclerosis results in adverse cardiac outcomes. It is also remains to be determined if change in plaque quantity is a strongly associated marker with cardiac adverse events, so that intervention for plaque regression could be an appropriate surrogate endpoint. Data are even more limited in low to intermediate risk patients.

The ability to perform larger-scale studies of plaque regression has also been limited thus far because the costly and invasive nature of IVUS. While CCTA is ideal for cost reduction, lower-risk patient populations, and appears to possess the technical ability to measure changes in plaque over time; larger studies with serial CCTA measurements have only occurred in the past five years, and still multiple orders of magnitude smaller than the largest statin therapy trials (Table 3, Table 1). This is in part related to recent changes within current state of technology, namely that regular serial CCTA scans in low to moderate risk patients had been previously unreasonable due to radiation exposure, but has become safer with technological improvement.

The upcoming PARADIGM registry may help address some of our gaps in knowledge. This registry aims to be the largest multi-center registry of patients with serial CCTA imaging. It is aimed at prospectively describing the natural history of atherosclerosis by CCTA in low to moderate risk patients, capturing quantitative and qualitative changes in coronary atherosclerosis over time, and subsequent major adverse cardiac events. Whereas current serial CCTA studies have all been under 500 patients, PARADIGM will aim for >2,000 patients with at least two years between initial and follow up imaging.76 From observational data provided by PARADIGM and potential other future serial CCTA trials, we hope to better understand the strength of the association between changes in plaque and outcomes, as well as to generate hypotheses on how to most effectively modify the natural history of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease.

After these advances, we may begin to address the remaining barriers to the use of CCTA to personalize cardiovascular medicine, one of the largest being the lack of interventional trials. In the current literature, we know of only one randomized pharmacological interventional trial utilizing serial CCTA in 37 HIV-infected patients, with a measured outcome of plaque regression, not cardiovascular events.74 It remains to be seen whether or not characteristics measured by CCTA can be adequately used to predict personalized outcomes. This is unfortunately a structurally difficult question to answer, as large population randomized trials are inherently geared towards generating population-based outcomes over personalized outcomes. In order to definitively address this within a trial, the pharmacological intervention would have to be personalized; for example, titration of statin dosing to plaque regression within an individual, with a measured hard cardiovascular outcome. A trial of any size combining serial CCTA and titrated statin dosing with longitudinal outcomes would be an extremely complex undertaking, and until this is resolved it may be difficult to provide justification for personalized therapy over risk-category based treatment.

5. Conclusion

Lipid-lowering therapy has become the cornerstone in primary and secondary prevention of ASCVD. Despite strong efficacy, adverse cardiovascular events still occur in a significant number of patients receiving statins. There are no biomarkers to date to identify these patients. Non-calcified plaque burden is independently associated with cardiac outcomes, with change in plaque burden measured by IVUS as a potential marker of treatment response. CCTA can measure changes in non-calcified coronary plaque burden and high-risk plaque features, which may allow for personalized assessment of risk in the future. Definitive confirmation of the significance of quantitative changes in coronary plaque is yet to be obtained and the optimal methods to reduce plaque burden in at-risk patients remains to be determined. Research in this area may advance us towards an era of personalized risk prediction and individualized medical therapy. Until then, cumulative and current evidence to date support intensive lipid lowering therapy with a “lower-is-better” approach in high-risk patients.

6. Expert Commentary:

In this review, we highlight developments in the technological advance of cardiac CT, the pathophysiological correlates of these new measurement abilities, and an unmet need within current practice of lipid-lowering therapy, namely the inability to identify patients who benefit or not while on guideline directed medical therapy. CCTA has improved significantly, and while it does not possess the resolution of IVUS, from a pragmatic standpoint the relative ease and non-invasive nature of CCTA presents an obvious opportunity to understand the natural history of atherosclerosis, particularly in low and moderate risk patients. The PARADIGM registry is an excellent example of developing these abilities, and will likely provide us with a greater understanding of cardiovascular disease.

At a deeper level, however, this unmet need highlights an inherent problem with our population-based treatment algorithms, namely that for lipid-lowering therapies, the number needed to treat is significantly greater than one. In other medical fields, such as infectious disease, the number needed to treat is closer to one, and in fields such as surgery, the number needed to treat often reaches one for procedures like appendectomy or cholecystectomy. Preventive cardiology nevertheless has flourished, in part due to such high prevalence of disease that these medications still provide an excellent population-wide benefit, despite limitations on an individual level. This is juxtaposed with imaging, which is an extremely personalized diagnostic modality. Few would argue that a CT scan was less specific to an individual than a lipid panel or a blood pressure. This level of specificity and personalization provides an amount of information that can make it difficult to standardize therapeutic options, and often we respond to this by attempting to group non-dichotomous imaging variables into dichotomies, such as CAC zero versus non-zero.

What we wish to do with this review is to conceptualize a middle ground between standardization and personalization, to use CCTA to move the number needed to treat for lipid-lowering therapy closer to one. We specifically suggest using non-calcified plaque progression versus regression as a pathophysiologically based dichotomous variable to assess therapeutic response, though we recognize that the breadth of information captured by CCTA reaches far beyond this. As discussed, proving that targeting an individual marker of therapeutic response (in this case, plaque regression) will provide an individual mortality benefit is extremely difficult, though biological plausibility for reduction of disease substrate reducing disease incidence is somewhat self-evident. We can see an analogy to this problem within the 2013 lipid guidelines, where LDL-C threshold goals were removed due to lack of randomized control trial evidence for personalized thresholds.77 Whether or not threshold recommendations will return in the future has yet to be determined.

Our hope for the future is we can move away from abstract surrogate markers such as risk category as a predictor of treatment efficacy, towards monitoring of disease phenotype and personalized response to therapy. We believe that CCTA is potentially well-situated to provide this personalization, and quantitative plaque regression as an intervention may be able to capture multiple aspects of treatment response, allowing us to directly target the pathophysiological underpinnings of coronary atherosclerosis. For CCTA, our envisioned ultimate goal would be guided regression of atherosclerosis to a disease-free or maximally stabilized state within an individual. Interestingly, the CCTA studies demonstrating the ability to measure change in non-calcified plaque over serial examinations have been primarily performed on 64-slice single energy scanners, a generation or more behind current dual energy designs. This suggests that the true advancement that could allow a shift in our management of disease is not a breakpoint in imaging resolution, but a combination of factors: radiation reduction, new therapeutic options, along with increasing clinical acceptance of the role of cardiac CT in disease management.

In order to leverage the advancements of CCTA to address the issue of residual ASCVD risk in individual patients, multiple steps are necessary. Studies designed to confirm the IVUS meta-analysis results that plaque regression is associated with improved outcomes are needed. These studies should include large observational studies of asymptomatic patients with low to moderate risk like PARADIGM that can evaluate whether plaque regression is associated with improved outcomes and improve our understanding the progression and development of coronary atherosclerosis. It will be essential to understand the interaction between early versus advanced disease substrates and medical therapy in order to pursue the most effective disease modification strategy. Next, trials to determine the most effective way to regress coronary atherosclerosis in patients who failed to regress on typical statin therapy should be performed. Finally, trials comparing personalized lipid-lowering regimens for plaque reduction versus standard management can help us understand if personalized medicine can be effective at decreasing the residual risk currently seen.

7. Five-year view

Widespread adoption of cardiac CT, and thus CCTA, has been limited by perceived lack of added value when weighed against the cost and risks of exposure to radiation or iodinated contrast. However, over the next five years, we will see a shift in perception. New technological advancements such as perfusion imaging, FFR-CT, and dual-energy material decomposition of plaque will become more commonplace among major medical centers; the broadening portfolio of CT’s ability to provide anatomical and functional information quickly, cheaply, and noninvasively will lift the perception of the entire modality. Diagnostic workup that was previously firmly within the realm of nuclear cardiology, cardiac magnetic resonance imaging, or diagnostic invasive catheterization will now overlap with cardiac CT. While CCTA represents only a one facet of the modality, from a research standpoint it will significantly benefit from the influx of data and utilization, and will begin to improve our understanding of how our lipid-lowering therapies affect coronary atherosclerosis over time.

8. Key Issues:

Lipid-lowering therapies have reduced mortality in atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease by approximately 25%. Major adverse cardiovascular events still occur in patients on guideline directed lipid-lowering treatment.

Current markers of therapeutic response to lipid-lowering therapies are insufficient to capture residual risk and identify individuals that receive or lack benefit from lipid-lowering therapy.

Plaque regression, quantified by various imaging modalities, is a marker for evidence of response to lipid-lowering therapy.

Coronary computed tomographic angiography has improved in resolution, radiation exposure, and reliability to the point that it can be considered for non-invasive detection of changes in non-calcified plaque volume over time.

Non-invasive imaging may provide a way to identify residual risk and therapeutic response to lipid-lowering therapy in order to personalize medical treatment and maximize therapeutic efficacy.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This paper was not funded.

Footnotes

Declaration of interest

The authors have no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending, or royalties.

References

Reference annotations

* Of interest

** Of considerable interest

- 1.Murray CJ et al. Disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for 291 diseases and injuries in 21 regions, 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. The lancet 380, 2197–2223 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mozaffarian D. et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics—2016 Update A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation, CIR. 0000000000000350 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Libby P. The forgotten majority: unfinished business in cardiovascular risk reduction. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 46, 1225–1228 (2005).*Early paper describing residual risk within cardiovascular therapy

- 4.Holmes C, Schulzer M. & Mancini G. Angiographic results of lipid-lowering trials: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cholesterol-lowering therapy: evaluation of clinical trial evidence. New York: Marcel Dekker Inc, 191–220 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tsujita K. et al. Impact of dual lipid-lowering strategy with ezetimibe and atorvastatin on coronary plaque regression in patients with percutaneous coronary intervention: the multicenter randomized controlled PRECISE-IVUS trial. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 66, 495–507 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tavazzi L. et al. Effect of rosuvastatin in patients with chronic heart failure (the GISSI-HF trial): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet (London, England) 372, 1231–1239 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kjekshus J. et al. Rosuvastatin in older patients with systolic heart failure. New England Journal of Medicine 357, 2248–2261 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Banach M. et al. Statin intolerance–an attempt at a unified definition. Position paper from an International Lipid Expert Panel. Archives of medical science: AMS 11, 1 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tice JA OD, Cunningham C, Pearson SD, Kazi DS, Coxon PG, Moran AE, Penko J, Guzman D, Bibbins-Domingo K . in PCSK9 Inhibitors for Treatment of High Cholesterol: Effectiveness, Value, and Value Based Price Benchmarks (Institute for Clinical and Economic Review, Comparative Effectiveness Public Advisory Council, 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mora S. et al. Determinants of Residual Risk in Secondary Prevention Patients Treated With High-Versus Low-Dose Statin Therapy The Treating to New Targets (TNT) Study. Circulation 125, 1979–1987 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ishikawa T. et al. The relationship between the effect of pravastatin and risk factors for coronary heart disease in Japanese patients with hypercholesterolemia. Circulation Journal 72, 1576–1582 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Group, W.o.S.C.P.S. Influence of pravastatin and plasma lipids on clinical events in the West of Scotland Coronary Prevention Study (WOSCOPS). Circulation 97, 1440–1445 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peters BJ et al. Genetic variability within the cholesterol lowering pathway and the effectiveness of statins in reducing the risk of MI. Atherosclerosis 217, 458–464 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kataoka Y. et al. Atheroma progression in hyporesponders to statin therapy. Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology 35, 990–995 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chasman DI et al. Pharmacogenetic study of statin therapy and cholesterol reduction. Jama 291, 2821–2827 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wannarong T. et al. Progression of carotid plaque volume predicts cardiovascular events. Stroke 44, 1859–1865 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Budoff MJ et al. Progression of coronary artery calcium predicts all-cause mortality. JACC: Cardiovascular Imaging 3, 1229–1236 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kobashigawa JA et al. Multicenter intravascular ultrasound validation study among heart transplant recipients: outcomes after five years. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 45, 1532–1537 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tuzcu EM et al. Intravascular ultrasound evidence of angiographically silent progression in coronary atherosclerosis predicts long-term morbidity and mortality after cardiac transplantation. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 45, 1538–1542 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Puri R. et al. Left main coronary atherosclerosis progression, constrictive remodeling, and clinical events. JACC: Cardiovascular Interventions 6, 29–35 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ridker PM, Mora S. & Rose L. Per cent reduction in LDL cholesterol following high-intensity statin therapy: potential implications for guidelines and for the prescription of emerging lipid-lowering agents. European Heart Journal (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.von Birgelen C. et al. Relation Between Progression and Regression of Atherosclerotic Left Main Coronary Artery Disease and Serum Cholesterol Levels as Assessed With Serial Long-Term (≥12 Months) Follow-Up Intravascular Ultrasound. Circulation 108, 2757–2762 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.D’Ascenzo F. et al. Atherosclerotic coronary plaque regression and the risk of adverse cardiovascular events: a meta-regression of randomized clinical trials. Atherosclerosis 226, 178–185 (2013).*Meta-analysis showing potential benefit of coronary plaque regression.

- 24.Nicholls SJ. et al. Intravascular ultrasound-derived measures of coronary atherosclerotic plaque burden and clinical outcome. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 55, 2399–2407 (2010).*Meta-analysis showing potential benefit of coronary plaque regression.

- 25.Bayturan O. et al. Clinical predictors of plaque progression despite very low levels of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 55, 2736–2742 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Puri R, Nissen SE & Nicholls SJ Statin-induced coronary artery disease regression rates differ in men and women. Current opinion in lipidology 26, 276–281 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hattori K. et al. Impact of statin therapy on plaque characteristics as assessed by serial OCT, grayscale and integrated backscatter–IVUS. JACC: Cardiovascular Imaging 5, 169–177 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Habara M. et al. Impact on optical coherence tomographic coronary findings of fluvastatin alone versus fluvastatin+ ezetimibe. The American journal of cardiology 113, 580–587 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kini AS et al. Changes in Plaque Lipid Content After Short-Term Intensive Versus Standard Statin TherapyThe YELLOW Trial (Reduction in Yellow Plaque by Aggressive Lipid-Lowering Therapy). Journal of the American College of Cardiology 62, 21–29 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Takano M. et al. Changes in coronary plaque color and morphology by lipid-lowering therapy with atorvastatin: serial evaluation by coronary angioscopy. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 42, 680–686 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kodama K. et al. Stabilization and regression of coronary plaques treated with pitavastatin proven by angioscopy and intravascular ultrasound-the TOGETHAR trial. Circulation Journal 74, 1922–1928 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Takayama T. et al. Remodeling pattern is related to the degree of coronary plaque regression induced by pitavastatin: a sub-analysis of the TOGETHAR trial with intravascular ultrasound and coronary angioscopy. Heart and vessels 30, 169–176 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Puri R. et al. Long-term effects of maximally intensive statin therapy on changes in coronary atheroma composition: insights from SATURN. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging 15, 380–388 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Räber L. et al. Effect of high-intensity statin therapy on atherosclerosis in non-infarct-related coronary arteries (IBIS-4): a serial intravascular ultrasonography study. European heart journal 36, 490–500 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Paixao AR et al. Coronary artery calcium improves risk classification in younger populations. JACC: Cardiovascular Imaging 8, 1285–1293 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Detrano R. et al. Coronary calcium as a predictor of coronary events in four racial or ethnic groups. New England Journal of Medicine 358, 1336–1345 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nicoll R. et al. The coronary calcium score is a more accurate predictor of significant coronary stenosis than conventional risk factors in symptomatic patients: Euro-CCAD study. International Journal of Cardiology 207, 13–19 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Erbel R. et al. Coronary risk stratification, discrimination, and reclassification improvement based on quantification of subclinical coronary atherosclerosis: the Heinz Nixdorf Recall study. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 56, 1397–1406 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hoffmann U. et al. Cardiovascular Event Prediction and Risk Reclassification by Coronary, Aortic, and Valvular Calcification in the Framingham Heart Study. Journal of the American Heart Association 5, e003144 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McClelland RL et al. 10-year coronary heart disease risk prediction using coronary artery calcium and traditional risk factors: derivation in the MESA (Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis) with validation in the HNR (Heinz Nixdorf Recall) Study and the DHS (Dallas Heart Study). Journal of the American College of Cardiology 66, 1643–1653 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Blaha MJ et al. Role of Coronary Artery Calcium Score of Zero and Other Negative Risk Markers for Cardiovascular Disease: The Multi-Ethnic Study Of Atherosclerosis (MESA). Circulation, CIRCULATIONAHA. 115.018524 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Erbel R. et al. Progression of coronary artery calcification seems to be inevitable, but predictable - results of the Heinz Nixdorf Recall (HNR) study. European Heart Journal 35, 2960–2971 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Priester TC & Litwin SE Measuring progression of coronary atherosclerosis with computed tomography: searching for clarity among shades of gray. Journal of cardiovascular computed tomography 3, S81–S90 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nicholls SJ et al. Coronary artery calcification and changes in atheroma burden in response to established medical therapies. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 49, 263–270 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kwan AC et al. Coronary artery plaque volume and obesity in patients with diabetes: the factor-64 study. Radiology 272, 690–699 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kristensen TS et al. Prognostic implications of nonobstructive coronary plaques in patients with non–ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: a multidetector computed tomography study. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 58, 502–509 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Motoyama S. et al. Plaque characterization by coronary computed tomography angiography and the likelihood of acute coronary events in mid-term follow-up. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 66, 337–346 (2015).**The largest serial CCTA cohort with outcomes for qualitative plaque characteristics.

- 48.Miller JM et al. Diagnostic performance of coronary angiography by 64-row CT. New England Journal of Medicine 359, 2324–2336 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Budoff MJ et al. CT Angiography for the Prediction of Hemodynamic Significance in Intermediate and Severe Lesions: Head-to-Head Comparison With Quantitative Coronary Angiography Using Fractional Flow Reserve as the Reference Standard. JACC: Cardiovascular Imaging 9, 559–564 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rochitte CE et al. Computed tomography angiography and perfusion to assess coronary artery stenosis causing perfusion defects by single photon emission computed tomography: the CORE320 study. European heart journal 35, 1120–1130 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nørgaard BL et al. Diagnostic performance of noninvasive fractional flow reserve derived from coronary computed tomography angiography in suspected coronary artery disease: the NXT trial (Analysis of Coronary Blood Flow Using CT Angiography: Next Steps). Journal of the American College of Cardiology 63, 1145–1155 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Taylor AJ et al. ACCF/SCCT/ACR/AHA/ASE/ASNC/NASCI/SCAI/SCMR 2010 appropriate use criteria for cardiac computed tomography: a report of the American college of cardiology foundation appropriate use criteria task force, the society of cardiovascular computed tomography, the American college of radiology, the American heart association, the American society of echocardiography, the American society of nuclear cardiology, the north American society for cardiovascular imaging, the society for cardiovascular angiography and interventions, and the society for cardiovascular magnetic resonance. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 56, 1864–1894 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chen MY, Shanbhag SM & Arai AE Submillisievert median radiation dose for coronary angiography with a second-generation 320–detector row CT scanner in 107 consecutive patients. Radiology 267, 76–85 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schuhbaeck A. et al. Interscan reproducibility of quantitative coronary plaque volume and composition from CT coronary angiography using an automated method. European radiology 24, 2300–2308 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Øvrehus KA et al. Reproducibility of semi-automatic coronary plaque quantification in coronary CT angiography with sub-mSv radiation dose. Journal of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography 10, 114–120 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bruining N. et al. Reproducible coronary plaque quantification by multislice computed tomography. Catheterization and Cardiovascular Interventions 69, 857–865 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Park H-B et al. Clinical feasibility of 3D automated coronary atherosclerotic plaque quantification algorithm on coronary computed tomography angiography: comparison with intravascular ultrasound. European radiology 25, 3073–3083 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Symons R MJ, Wu CO, Pourmorteza A, Ahlman MA, Lima JAC, Chen MY, Mallek M, Sandfort V, Bluemke DA. Coronary CT angiography: variability of CT scanners and readers for measurement of plaque volume. Radiology In Press (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bruining N. et al. Compositional volumetry of non-calcified coronary plaques by multislice computed tomography: an ex vivo feasibility study. EuroIntervention: journal of EuroPCR in collaboration with the Working Group on Interventional Cardiology of the European Society of Cardiology 5, 558–564 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Motoyama S. et al. Computed tomographic angiography characteristics of atherosclerotic plaques subsequently resulting in acute coronary syndrome. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 54, 49–57 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pflederer T. et al. Characterization of culprit lesions in acute coronary syndromes using coronary dual-source CT angiography. Atherosclerosis 211, 437–444 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Otsuka K. et al. Napkin-ring sign on coronary CT angiography for the prediction of acute coronary syndrome. JACC: Cardiovascular Imaging 6, 448–457 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Puchner SB et al. High-risk plaque detected on coronary CT angiography predicts acute coronary syndromes independent of significant stenosis in acute chest pain: results from the ROMICAT-II trial. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 64, 684–692 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sandfort V, Lima JA & Bluemke DA Noninvasive Imaging of Atherosclerotic Plaque Progression Status of Coronary Computed Tomography Angiography. Circulation: Cardiovascular Imaging 8, e003316 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rodriguez K. et al. Coronary plaque burden at coronary CT angiography in asymptomatic men and women. Radiology 277, 73–80 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gitsioudis G. et al. Combined Assessment of High-Sensitivity Troponin T and Noninvasive Coronary Plaque Composition for the Prediction of Cardiac Outcomes. Radiology 276, 73–81 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Schmid M. et al. Assessment of changes in non-calcified atherosclerotic plaque volume in the left main and left anterior descending coronary arteries over time by 64-slice computed tomography. The American journal of cardiology 101, 579–584 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Papadopoulou S-L et al. Natural history of coronary atherosclerosis by multislice computed tomography. JACC: Cardiovascular Imaging 5, S28–S37 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ayad SW, ElSharkawy EM, ElTahan SM, Sobhy MA & Laymouna RH The Role of 64/128-Slice Multidetector Computed Tomography to Assess the Progression of Coronary Atherosclerosis. Clinical Medicine Insights. Cardiology 9, 47 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ito H. et al. Characteristics of plaque progression detected by serial coronary computed tomography angiography. Heart and vessels 29, 743–749 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Inoue K. et al. Serial coronary CT angiography–verified changes in plaque characteristics as an end point: evaluation of effect of statin intervention. JACC: Cardiovascular Imaging 3, 691–698 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zeb I. et al. Effect of statin treatment on coronary plaque progression–a serial coronary CT angiography study. Atherosclerosis 231, 198–204 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Shin S. et al. Impact of Intensive LDL Cholesterol Lowering on Coronary Artery Atherosclerosis Progression: A Serial CT Angiography Study. JACC: Cardiovascular Imaging (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lo J. et al. Effects of statin therapy on coronary artery plaque volume and high-risk plaque morphology in HIV-infected patients with subclinical atherosclerosis: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. The Lancet HIV 2, e52–e63 (2015).**RCT with serial CCTA imaging.

- 75.Stone GW et al. A prospective natural-history study of coronary atherosclerosis. New England Journal of Medicine 364, 226–235 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lee S-E. et al. Rationale and design of the Progression of AtheRosclerotic PlAque DetermIned by Computed TomoGraphic Angiography IMaging (PARADIGM) registry: A comprehensive exploration of plaque progression and its impact on clinical outcomes from a multicenter serial coronary computed tomographic angiography study. American heart journal 182, 72–79 (2016).*Planned design for large-scale serial CCTA registry.

- 77.Stone NJ et al. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 63, 2889–2934 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]