Abstract

Patients on maintenance hemodialysis (MHD), which are at high risk of infection by SARS-CoV-2 virus and death due to COVID-19, have been prioritized for vaccination. However, because they were excluded from pivotal studies and have weakened immune responses, it is not known whether these patients are protected after the “standard” two doses of mRNA vaccines. To answer this, anti-spike receptor binding domain (RBD) IgG and interferon gamma-producing CD4+ and CD8+ specific-T cells were measured in the circulation 10-14 days after the second injection of BNT162b2 vaccine in 106 patients receiving MHD (14 with history of COVID-19) and compared to 30 healthy volunteers (four with history of COVID-19). After vaccination, most (72/80, 90%) patients receiving MHD naïve for the virus generated at least one type of immune effector, but their response was weaker and less complete than that of healthy volunteers. In multivariate analysis, hemodialysis and immunosuppressive therapy were significantly associated with absence of both anti-RBD IgGs and anti-spike CD8+ T cells. In contrast, previous history of COVID-19 in patients receiving MHD correlated with the generation of both types of immune effectors anti-RBD IgG and anti-spike CD8+ T cells at levels similar to healthy volunteers. Patients receiving MHD naïve for SARS-Cov-2 generate mitigated immune responses after two doses of mRNA vaccine. Thus, the good response to vaccine of patients receiving MHD with a history of COVID-19 suggest that these patients may benefit from a third vaccine injection.

Keywords: BNT162b2, COVID-19, hemodialysis, mRNA vaccine, SARS-CoV-2

Graphical abstract

Among the various alarms raised by the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic was its impact on the population of patients with end-stage renal disease,1 , 2, particularly those requiring in-center hemodialysis. Logistical aspects of maintenance hemodialysis (MHD), including frequent encounters at health care facilities with other patients and staff, the physical proximity of patients during sessions, and transportation to and from center in shared vehicles, increase the risk for disease transmission.3 As a result, the reported incidence of COVID-19 in hemodialysis centers was high, particularly during the peaks of the pandemic.1 , 4 , 5 Furthermore, because of their comorbid profile and chronic kidney disease–induced immunosuppression,6, 7, 8 the risk of death due to COVID-19 was consistently and dramatically higher in MHD patients infected with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) than in the general population.9, 10, 11

Because of their higher risk for both infection by SARS-CoV-2 and death due to COVID-19, MHD patients were prioritized for vaccination in France.12 Pivotal studies using lipid nanoparticle-encapsulated mRNA-based vaccines that encode the full-length spike protein of SARS-CoV-2 showed excellent efficacy (~95%) at preventing COVID-19 illness in the general population after 2 doses of the vaccine administered i.m. 3 weeks apart.13 , 14 However, whether these good results are generalizable to individuals living with kidney disease, in particular those on MHD, is not certain because the latter were not enrolled in these studies.15 Furthermore, several lines of evidence suggest that in MHD patients, immune response (in particular after vaccination) may be blunted.7 , 8

Aiming at evaluating the immunogenicity of the SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine BNT162b2 in MHD individuals, the Response Of heModialyzed pAtieNts to cOvid-19 Vaccination (ROMANOV) study prospectively quantified the humoral and cellular responses after the second dose of vaccines in 106 patients on MHD in Lyon University Hospital and compared these results with those of a cohort of 30 healthy volunteers (HVs).

Methods

Study population

According to the recommendations of the French health authority,12 vaccination with mRNA BNT162b2 COVID-19 vaccine was offered to all patients on MHD in the 2 centers of Lyon University Hospital (France) who did not have any of the following contraindications: diagnosis of COVID-19 within the last 3 months, organ transplantation within the last 3 months, rituximab injection within the last 3 months, ongoing flare of vasculitis, acute sepsis, or major surgery within the last 2 weeks.

All adult patients who received a standard (prime + boost 3 to 5 weeks apart, depending on availability of the dose) vaccination with BNT162b2 vaccine and gave consent for the use of their blood, collected at the time of a routine biological evaluation, for analysis of the postvaccinal immune response were enrolled in ROMANOV study.

In the absence of validated correlates of vaccine-induced protection against SARS-CoV-2 (i.e., measurable parameter indicating that a person is protected against becoming infected and/or developing COVID-19 disease),14 we reasoned that hemodialyzed patients would have the same excellent level of protection as the general population14 if they were able to generate similar amount of specific humoral (antibodies) and cellular (helper and cytotoxic T lymphocytes) effectors. We therefore compared the amount of anti-spike receptor-binding domain (RBD) IgG and interferon-γ–producing cluster of differentiation (CD) 4+ and CD8+ T cells measured 10 to 14 days after the second injection in MHD patients with the values measured at the same time point in a cohort of 30 HVs. This timing was selected on the basis of previous reports demonstrating that both cellular and antibody responses are at their peak at this time point.16

History of COVID-19 was defined as a positive polymerase chain reaction test in nasopharyngeal swab. The screening for infection was performed in patients in the presence of symptoms or because the patient had contact with a positive case. The same detection strategy was applied to MHD patients and HVs.

The ROMANOV study was conducted in accordance with the French legislation on biomedical research and the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was evaluated by a national ethical research committee (ID-RCB 2021-A00325-36). The French National Commission for the Protection of Digital Information authorized the conduction of the study.

Anti–SARS-CoV-2 spike-RBD (S-RBD) humoral response assessment

The IgG antibodies directed against the RBD of the spike glycoprotein of the SARS-CoV-2 were detected by a chemiluminescence technique, using the Maglumi SARS-CoV-2 S-RBD IgG test (Snibe Diagnostic) on a Maglumi 2000 analyzer (Snibe Diagnostic), according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Briefly, 10 μl of serum was incubated in the appropriate buffer with magnetic microbeads covered with S-RBD recombinant antigen, to form immune complexes. After precipitation in a magnetic field and washing, N-(4-aminobutyl)-N-ethylisoluminol–stained anti-human IgG antibodies were added to the samples. After a second magnetic separation and washing, the appropriate reagents were added to initiate a chemiluminescence reaction. When necessary, sera were diluted sequentially up to 1:1000.

Anti–SARS-CoV-2 spike cellular response assessment

Spike-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell response was quantified in the circulation of the HVs and hemodialyzed patients using the QuantiFERON SARS-CoV-2 test (Qiagen), a commercially available interferon-γ releasing assay, according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Briefly, after collection, 1 ml blood was distributed in each tube of the assay: (i) uncoated tube: negative control/background noise, (ii) tube coated with mitogen: positive control, (iii) tube coated with human leukocyte antigen-II restricted 13-mer peptides derived from the entire SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein used to stimulate CD4+ T cells, and (iv) tube coated with human leukocyte antigen-II and human leukocyte antigen-I 8- and 13-mer derived from the entire SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein used to stimulate both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. After 20 hours of culture at 37 °C, tubes were centrifuged for 15 minutes at 2500g, and stored at 4 °C before interferon-γ quantification by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay.

The CD4+ T-cell assay value was the difference between tube (iii) and the negative control. The CD8+ T-cell assay value was the value obtained for tube (iv), with subtraction of the CD4 tube (iii) and the negative control (i).

Statistical analysis

All the analyses were performed using R software version 4.0.4 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2021; https://www.R-project.org) and/or GraphPad Prism v8.0. Categorical variables were expressed as percentages and compared with the χ2 test. Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± SD and compared using 1-way analysis of variance and multiple t-test post hoc analyses or as median ± interquartile range and compared using Mann-Whitney test for variables with nonnormal distribution.

Logistic regression models were used in both univariate and multivariate analyses. Noncolinear explanatory variables associated with outcomes (i.e., optimal humoral and cellular responses) in univariate analysis (P < 0.1) were included in multivariate models. The Firth bias-correction method was used in cases of complete separation.17 Stepwise regression analyses with bidirectional elimination were then performed, using Aikake information criterion to select the most fitting final multivariate models.

Venn diagrams were computed using R with the “ggplot2” and “ggVennDiagram” packages.

Results

Study design and characteristics of the population

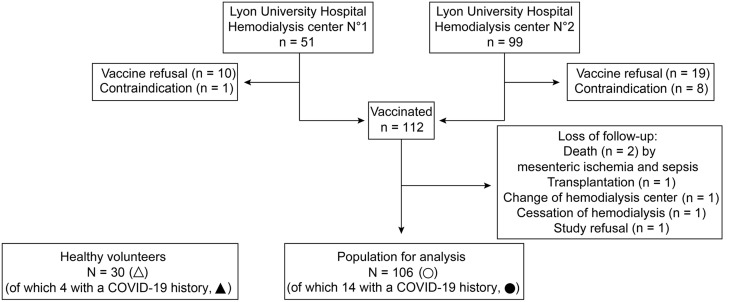

Among the 150 MHD patients dialyzing at Lyon University Hospital, 38 refused the vaccine or had contraindications to the injection. Of the 112 who were vaccinated, 1 declined participating in the study and 5 were lost during the follow-up (Figure 1 ). The general characteristics of the 106 MHD patients available for analysis, including 14 with a previous history of COVID-19 dating >3 months (black circles), are summarized in Table 1 . Mean age was 65 years, and most of them were male (65%) and had a high burden of comorbid conditions (including cardiovascular disease in 45% and diabetes in 44%). In addition, 22% had a history of kidney transplantation and 12% were on immunosuppressive drugs (crossed circles).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the study. COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019.

Table 1.

Clinical description of HVs and MHD patients

| Variable | MHD patients (N = 106) | HVs (N = 30) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, yr | 64.9 ± 15.2 | 46.6 ± 14.8 |

| Male sex | 69 (65) | 14 (47) |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 26.5 ± 6.5 | 24.1 ± 3.8 |

| Cause of renal failure | NA | |

| Vascular | 19 (18) | |

| Diabetes mellitus | 37 (35) | |

| Glomerulonephritis | 15 (14) | |

| Hereditary | 3 (3) | |

| Uropathy | 0 (0) | |

| Others | 32 (30) | |

| Comorbidities | ||

| Cardiovascular disease | 46 (43) | 1 (3) |

| Respiratory disease | 13 (12) | 1 (3) |

| Liver disease | 5 (5) | 0 (0) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 47 (44) | 0 (0) |

| History of COVID-19 | 14 (13) | 4 (13) |

| Asymptomatic | 3 (21) | 1 (25) |

| Mild or moderate | 7 (50) | 3 (75) |

| Critical | 4 (29) | 0 (0) |

| Previous SOT | 23 (22) | 0 (0) |

| Time in HD, d | 1520 ± 1822 | NA |

| HD parameters | NA | |

| HD time per week, min | 691 ± 85 | |

| Kt/Va | 1.58 ± 0.41 | |

| IS drugs | 13 (12) | 0 (0) |

| Tacrolimus | 8 (8) | |

| Anti-metabolite | 4 (4) | |

| Steroids >5 mg/d | 3 (3) | |

| Rituximab | 1 (1) | |

| Chemotherapy | 4 (4) | |

| Biological data | NA | |

| Hemoglobin, g/L | 109 ± 14 | |

| Lymphocytes, G/L | 1.18 ± 0.53 | |

| Monocytes, G/L | 0.63 ± 0.25 | |

| CRP, mg/L | 12.6 ± 21.0 | |

| Albumin, g/L | 35.8 ± 5.2 | |

| Prealbumin, g/L | 0.34 ± 0.27 | |

| Phosphorus, mmol/L | 1.58 ± 0.50 |

BMI, body mass index; COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; CRP, C-reactive protein; G, giga; HD, hemodialysis; HV, healthy volunteer; IS, immunosuppressive; MHD, maintenance hemodialysis; NA, not available; SOT, solid organ transplantation.

Data are given as n (%) or mean ± SD.

Kt/V was used for the quantification of dialysis adequacy by the following formula: dialysis clearance of urea (K) multiplied by dialysis time (t), divided by the volume of distribution of urea (V).

These 106 MHD patients were compared with a cohort of 30 unmatched HVs, 4 of whom had a history of COVID-19 dating of >3 months (black triangles; Figure 1). The general characteristics of HVs are presented in Table 1.

Humoral response against SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine

According to the manufacturer, the threshold of detection of the assay for anti-RBD IgG is 1 arbitrary unit (Figure 2 a; dashed line). In contrast with all 30 HVs, who exhibited a homogeneous IgG response against RBD, 19 MHD patients (18%) did not develop any detectable antibody after 2 doses of vaccine (nonresponders; Figure 2a). To identify predictors of seroconversion following anti–SARS-CoV-2 vaccination, a first multivariate analysis was performed to compare these 19 nonresponders with the responders (87 MHD patients and 30 HVs). Only 2 variables were found independently associated with a lack of seroconversion: (i) being on hemodialysis (odds ratio [OR], 0.11; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.01–0.93; P = 0.041) or (ii) being on immunosuppressive treatment (OR, 0.09; 95% CI, 0.02–0.312; P = 0.001; Figure 2b and Supplementary Table S1). In contrast, a history of COVID-19 correlated with higher chances of seroconversion after vaccination (OR, 8.31; 95% CI, 0.87–1145; P = 0.071; Figure 2b).

Figure 2.

Humoral response of maintenance hemodialysis (MHD) patients totheBNT162b2 vaccine. (a) The titer of IgG anti–receptor-binding domain of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 spike protein (RBD) was determined by a chemoluminescence assay in 30 healthy volunteers (HVs; triangles) and 106 hemodialyzed patients (HDs; circles) before vaccination (day [D] 0) and 10 to 14 days after the second injection of vaccine. The dashed line represents the limit of detection of the test. Black symbols represent patients with a history of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) (HVs, n = 4; HDs, n = 14). Crossed circles represent patients on immunosuppressive (IS) drugs. Mann-Whitney test; ∗∗∗∗P < 0.0001. (b) A multivariate analysis was conducted to identify the variables independently associated with seroconversion in the whole cohort (gray square vs. white square). For each variable with a P < 0.10 in multivariate analysis, a forest plot shows the odds ratio and the 95% confidence interval (CI). (c) Comparison of anti-RBD IgG titers in HVs (n = 30), MHD patients with COVID-19 history (n = 14; black circles), MHD patients with IS drugs (n = 12; crossed circles), and naïve MHD patients (n = 80; white circles). The upper dotted line represents the median IgG titer of responder naïve MHD patients. Donuts represent proportions of nonresponders (white), low responders (light gray), and high responders (dark gray). (d) A multivariate analysis was conducted to identify the variables independently associated with a high IgG response to vaccine in naïve MHD patients without IS drugs (gray square vs. white square). For each variable with a P < 0.10 in multivariate analysis, a forest plot shows the odds ratio and the 95% CI. AU, arbitrary unit; Kt/V, dialysis clearance of urea (K) multiplied by dialysis time (t), divided by the volume of distribution of urea (V); NS, not significant.

The median titer of anti-RBD IgG (176 arbitrary units; Figure 2b; dotted line) was used to further divide naïve responder MHD patients without immunosuppressive therapy into low responders (34/80 [43%]) and high responders (35/80 [43%]).

The clinical and biological characteristics of the 3 categories of naïve MHD patients without immunosuppressive therapy are compared in Table 2 . A second multivariate analysis, conducted among naïve MHD patients without immunosuppressive therapy only (Figure 2c and Supplementary Table S2), identified 2 independent characteristics associated with a better antibody response after vaccination in this group: (i) younger age (OR, 0.97; 95% CI, 0.93–1.00; P = 0.064) and (ii) better dialysis quality (OR, 4.19; 95% CI, 1.04–21.15; P = 0.060).

Table 2.

Description of clinical and biological characteristics of naïve MHD patients without immunosuppressive therapy, according to their anti-RBD IgG response

| Variables | Non-R (N = 11) | Low-R (N = 34)a | High-R (N = 35)a | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, yr | 67.8 ± 10.5 | 71.6 ± 13.2 | 61.4 ± 15.5 | 0.013 |

| Male sex | 7 (64) | 25 (74) | 28 (80) | 0.165 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 25.0 ± 6.1 | 28.6 ± 7.2 | 26.2 ± 6.2 | 0.201 |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Cardiovascular | 8 (73) | 19 (56) | 13 (37) | 0.080 |

| Respiratory disease | 4 (36) | 2 (6) | 4 (11) | 0.028 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 5 (45) | 16 (47) | 14 (40) | 0.833 |

| Previous SOT | 4 (36) | 2 (6) | 9 (26) | 0.029 |

| Cause of renal failure | 0.965 | |||

| Vascular | 3 (27) | 6 (18) | 9 (26) | |

| Diabetes mellitus | 3 (27) | 14 (41) | 12 (34) | |

| Glomerulonephritis | 1 (9) | 5 (15) | 4 (11) | |

| Hereditary | 1 (9) | 1 (3) | 1 (3) | |

| Uropathy | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Others | 3 (27) | 8 (24) | 9 (26) | |

| Time in HD, d | 1772 ± 1420 | 1345 ± 1693 | 2037 ± 2406 | 0.977 |

| HD parameters | ||||

| HD time per week, min | 665 ± 86 | 699 ± 56 | 711 ± 64 | 0.123 |

| Kt/Vb | 1.59 ± 0.39 | 1.45 ± 0.30 | 1.69 ± 0.36 | 0.022 |

| Biological data | ||||

| Hemoglobin, g/L | 106 ± 12 | 109 ± 12 | 112 ± 14 | 0.446 |

| Lymphocytes, G/L | 0.84 ± 0.52 | 1.19 ± 0.46 | 1.36 ± 0.55 | 0.015 |

| Monocytes, G/L | 0.62 ± 0.41 | 0.64 ± 0.17 | 0.63 ± 0.21 | 0.964 |

| CRP, mg/L | 20.4 ± 20.9 | 10.8 ± 10.9 | 6.2 ± 7.4 | 0.003 |

| Albumin, g/L | 33.4 ± 4.3 | 36.6 ± 4.7 | 35.9 ± 5.6 | 0.206 |

| Prealbumin, g/L | 0.25 ± 0.08 | 0.34 ± 0.10 | 0.39 ± 0.45 | 0.387 |

| Phosphorus, mmol/L | 1.32 ± 0.39 | 1.58 ± 0.61 | 1.55 ± 0.50 | 0.299 |

BMI, body mass index; CRP, C-reactive protein; G, giga; HD, hemodialysis; High-R, high responders; Low-R, low responders; MHD, maintenance hemodialysis; Non-R, nonresponders; RBD, receptor-binding domain; SOT, solid organ transplantation.

Data are given as n (%) or mean ± SD. Qualitative variables are compared by χ2 test, and quantitative variables are compared by 1-way analysis of variance.

Low-R and High-R are defined by the median titer value of responder MHD patients without immunosuppressive therapy and naïve for the virus.

Kt/V was used for the quantification of dialysis adequacy by the following formula: dialysis clearance of urea (K) multiplied by dialysis time (t), divided by the volume of distribution of urea (V).

Spike-specific CD4+ T-cell response correlates with anti-RBD IgG response

The generation of IgG against a target protein requires a cognate interaction between antigen-specific B cells and antigen-specific CD4+ T cells.18 , 19

In line with their strong anti-RBD IgG response, all HVs (30/30 [100%]) and MHD patients with history of COVID-19 (14/14 [100%]) had detectable spike-specific CD4+ T cells in their circulation (Figure 3 a). This percentage was 70% (48/69) for responders but decreased to 18% (2/11) for nonresponders among naïve MHD patients without immunosuppressive therapy (Figure 3a). As expected, MHD patients on immunosuppressive therapy had almost never detectable spike-specific CD4+ T cells (Figure 3a). A correlation was therefore established between the presence of spike-specific CD4+ T cells and the titer of anti-RBD IgG (Figure 3b).

Figure 3.

Cluster of differentiation (CD) 4+T-cell response of maintenance hemodialysis (MHD) patients totheBNT162b2 vaccine correlates with humoral response. (a) The secretion of interferon-γ by circulating spike protein-specific CD4+ T cells was measured in vitro in healthy volunteers (HVs; n = 30; triangles), MHD patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) history (n = 14; black circles), MHD patients with immunosuppressive (IS) drugs (n = 12; crossed circles), and naïve MHD patients (n = 80; white circles) 10 to 14 days after the second injection of vaccine. Naive MHD patients were divided into 2 groups according to the absence (nonresponders [Non-resp]; n = 11) or presence (responders [Resp]; n = 69) of humoral response. The dashed line represents the threshold of positivity of the test. Mann-Whitney test; ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗∗P < 0.0001. (b) The correlation between the titer of anti–receptor-binding domain of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 spike protein (RBD) IgG and the secretion of interferon-γ by spike-specific CD4+ T cells is shown for HVs (n = 30), MHD patients with COVID-19 history (n = 14; black circles), MHD patients with IS drugs (n = 12; crossed circles), and naïve MHD patients (n = 80; white circles). The lower dashed line represents the limit of detection for anti-RBD IgG. The upper dotted line represents the median IgG titer of responder naïve MHD patients. Pie charts represent the percentage of patients with a positive (black) and negative (white) CD4+ T-cell response in each stratum of anti-RBD IgG response. χ2 Test; ∗∗∗∗P < 0.0001. AU, arbitrary unit; NS, not significant (P > 0.05).

Spike-specific CD8+ T-cell response in MHD patients

Complementing the role of antibodies, virus-specific CD8+ T cells are involved in the elimination of infected cells (virus “factories”). Like the humoral response, CD8+ T-cell response of MHD patients appeared more heterogeneous than that of HVs (Figure 4 a). Spike-specific CD8+ T cells could be detected in the large majority of HVs (21/30 [70%]) and MHD patients with history of COVID-19 (12/14 [86%]; Figure 4b). This percentage was 43% (30/69) for responders but only 18% (2/11) for nonresponders among naïve MHD patients without immunosuppressive therapy (Figure 4b). Again, MHD patients on immunosuppressive therapy had almost never (1/12 [8%]) detectable spike-specific CD8+ T cells (Figure 4b).

Figure 4.

Cluster of differentiation (CD) 8+T-cell response of maintenance hemodialysis (MHD) patients totheBNT162b2 vaccine. (a) The secretion of interferon-γ by circulating spike protein-specific CD8+ T cells was measured in vitro in healthy volunteers (HVs; n = 30; triangles) and hemodialyzed patients (n = 106; circles) 10 to 14 days after the second injection of the vaccine. Black symbols represent patients with a history of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). The dashed line represents the threshold of positivity of the test. Mann-Whitney test; ∗∗P < 0.01. (b) Spike-specific CD8+ responses in MHD patients were represented for patients with a COVID-19 history (n = 14; black circles), MHD patients with immunosuppressive (IS) drugs (n = 12; crossed circles), and naïve MHD patients (n = 80; white circles), according to the absence (nonresponders [Non-resp]; n = 11) or presence (responders [Resp]; n = 69) of humoral response. Mann-Whitney test; ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗P < 0.0001. (c) A multivariate analysis was conducted to identify the variables independently associated with a CD8+ T-cell response to the vaccine in the whole cohort (30 HVs and 106 MHD patients) (gray square as reference group vs. white square). A forest plot shows the odds ratio and the 95% confidence interval (CI) for a variable with P < 0.10 in the multivariate analysis. NS, not significant (P > 0.05).

The multivariate analysis conducted to identify the variable independently associated with the presence of spike-specific CD8+ T cells in the circulation after vaccination identified 3 variables: (i) being on hemodialysis (OR, 0.33; 95% CI, 0.13–0.81; P = 0.018), (ii) being on immunosuppression therapy (OR, 0.20; 95% CI, 0.03–0.89; P = 0.062), and (iii) a history of COVID-19 (OR, 12.26; 95% CI, 3.11–83.59; P = 0.002; Figure 4c and Supplementary Table S3). Among naïve MHD patients without immunosuppressive therapy, there were no differences in clinical and biological characteristics between patients who had or had not generated specific CD8+ T cells (Supplementary Table S4).

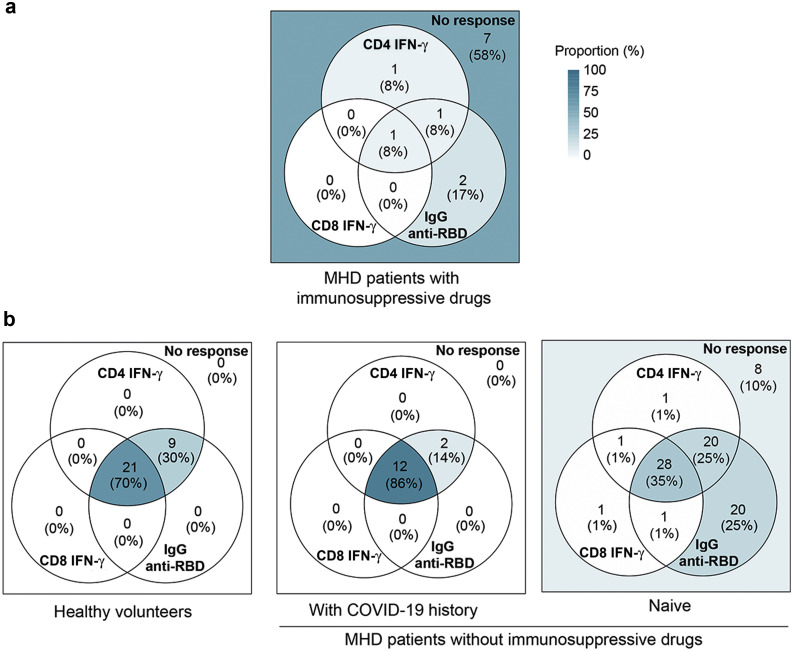

Profiling the immune response against SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine

Color-coded Venn diagrams were used to analyze the logical relation between the individual components of the immune response (IgG, CD4+ T cells, and CD8+ T cells) induced by SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine. Because immunosuppressive therapy has been shown above to strongly impair the response to the vaccine, these patients were analyzed separately (Figure 5 a). The profiles of the 3 remaining populations (HVs and MHD patients with and without medical history of COVID-19) were compared (Figure 5b).

Figure 5.

Profiling the immune response of maintenance hemodialysis (MHD) patients to the standard BNT162b2 vaccination. Color-coded Venn diagrams were used to analyze the logical relation between the individual components of the immune response (IgG, cluster of differentiation [CD] 4+ T cells, and CD8+ T cells) induced by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) mRNA vaccine. (a) Profile of immune response in MHD patients with immunosuppressive drugs. (b) Comparison of the profiles of 3 populations: healthy volunteers (n = 30) and MHD patients with (n = 14) and without (n = 80) a medical history of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). IFN-γ, interferon-γ; RBD, receptor-binding domain of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein.

Two doses of BNT162b2 vaccine were sufficient to induce the generation of a high number of all types of immune effectors in HVs (Figure 5b; left panel). However, although the same complete profile was observed in most (12/14 [86%]) MHD patients with a medical history of COVID-19 (Figure 5b; middle panel), most (52/80 [65%]) MHD patients naïve for the virus showed some defect in their anti-spike immune response (Figure 5b; right panel). The defective immune response of naïve MHD patients predominated for cellular response (i.e., CD4+ T cells detectable in only 50% of naïve MHD patients vs. 100% in HVs, and CD8+ T cells detectable in only 31% of naïve MHD patients vs. 70% in HVs).

Of note, only 3 naïve MHD patients had detectable spike-specific T cells in absence of anti-RBD IgG.

Discussion

The ROMANOV study prospectively quantified the anti-RBD IgG and the helper and cytotoxic T lymphocytes generated after 2 doses of BNT162b2 vaccine in MHD patients. Comparing these results with those of a cohort of unmatched HVs, we observed that if most MHD patients naïve for the virus develop some immune effectors after vaccination, their numbers remain below those observed in HVs, raising a question about the level of protection of vaccinated MHD patients. The facts that (i) hemodialysis was an independent predictor of lack of seroconversion after vaccination and (ii) the quality of the dialysis estimated by the Kt/V (dialysis clearance of urea [K] multiplied by dialysis time [t], divided by the volume of distribution of urea [V]) was associated with a better response to vaccine in naïve nonimmunosuppressed MHD suggest that uremic toxins could potentially play a detrimental role on the development of a humoral response.7 Furthermore, it has also been suggested that uremic milieu of end-stage renal disease may be associated with antibody dysfunction.20 It is therefore tempting to speculate that one could improve immune function (and therefore response to vaccine) of MHD patients by optimizing uremic toxin elimination. This theory is in line with the data reported by Kovacic et al., demonstrating that higher Kt/V values were associated with better antibody response to hepatitis B virus vaccine.21

The parameter that predicted the best optimal response to vaccination of MHD patients was a history of COVID-19. Indeed, although history of COVID-19 did not significantly impact the generation of any of the 3 types of immune effectors in vaccinated HVs, this parameter had a massive impact in MHD patients. In contrast with MHD patients naïve for the virus, those with a history of COVID-19 had a response to vaccine, which was indistinguishable from that of HVs. This result may indicate that increasing the exposure to viral antigens could circumvent the immune dysfunction of hemodialyzed patients. It is therefore tempting to speculate that naïve MHD patients with suboptimal immune response after 2 doses of vaccine might benefit from a third injection. This theory is in line with the better vaccine responses consistently reported in MHD populations following adaptation (i.e., increase in the dose and/or the number of injections) of vaccinal schemes.22

In conclusion, MHD patients naïve for SARS-CoV-2 are particularly vulnerable to SARS-CoV-2 and would greatly benefit from vaccine protection. However, the standard 2 doses scheme seems insufficient to induce in naïve MHD patients the same intensity of immune response as in HVs. In addition to optimization of dialysis therapy, which could improve immune function, naïve MHD patients might require additional injections of SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine. Prospective studies are urgently needed to validate this hypothesis.

Disclosure

All the authors declared no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

The authors are indebted to the members of the GRoupe de REcherche Clinique (Céline Dagot, Farah Pauwels, Fatiha M’Raiagh, and Daniel Sperandio), and Lise Siard, Claudine Lecuelle, and Philippe Favre from Eurofins Biomnis, for their precious help during the conduction of the study. ME is supported by the Hospices Civils de Lyon. XC is supported by funding from the Société Francophone de Transplantation. OT is supported by Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale (PME20180639518).

Footnotes

Table S1. Univariate analysis relating characteristics of responders versus nonresponders in the whole cohort (106 maintenance hemodialysis [MHD] patients + 30 healthy volunteers [HVs]).

Table S2. Univariate analysis relating comparisons between high responders and low + no responders in naïve maintenance hemodialysis (MHD) patients without immunosuppressive (IS) drugs.

Table S3. Univariate analysis relating characteristics of CD8 responders versus CD8+ nonresponders in the whole cohort (106 maintenance hemodialysis [MHD] patients + 30 healthy volunteers [HVs]).

Table S4. Univariate analysis relating comparisons between CD8 responders and CD8 nonresponders in naïve maintenance hemodialysis (MHD) patients without immunosuppressive (IS) drugs.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Thaunat O., Legeai C., Anglicheau D. IMPact of the COVID-19 epidemic on the moRTAlity of kidney transplant recipients and candidates in a French Nationwide registry sTudy (IMPORTANT) Kidney Int. 2020;98:1568–1577. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2020.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Williamson E.J., Walker A.J., Bhaskaran K. Factors associated with COVID-19-related death using OpenSAFELY. Nature. 2020;584:430–436. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2521-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weiner D.E., Watnick S.G. Hemodialysis and COVID-19: an Achilles’ heel in the pandemic health care response in the United States. Kidney Med. 2020;2:227–230. doi: 10.1016/j.xkme.2020.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Quintaliani G., Reboldi G., Di Napoli A. Exposure to novel coronavirus in patients on renal replacement therapy during the exponential phase of COVID-19 pandemic: survey of the Italian Society of Nephrology. J Nephrol. 2020;33:725–736. doi: 10.1007/s40620-020-00794-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Creput C., Fumeron C., Toledano D. COVID-19 in patients undergoing hemodialysis: prevalence and asymptomatic screening during a period of high community prevalence in a large Paris center. Kidney Med. 2020;2:716–723.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.xkme.2020.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Caillard S., Chavarot N., Francois H. Is COVID-19 infection more severe in kidney transplant recipients? Am J Transplant. 2021;21:1295–1303. doi: 10.1111/ajt.16424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Espi M., Koppe L., Fouque D., Thaunat O. Chronic kidney disease-associated immune dysfunctions: impact of protein-bound uremic retention solutes on immune cells. Toxins. 2020;12:300. doi: 10.3390/toxins12050300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Betjes M.G.H. Immune cell dysfunction and inflammation in end-stage renal disease. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2013;9:255–265. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2013.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ng J.H., Hirsch J.S., Wanchoo R. Outcomes of patients with end-stage kidney disease hospitalized with COVID-19. Kidney Int. 2020;98:1530–1539. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2020.07.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jager K.J., Kramer A., Chesnaye N.C. Results from the ERA-EDTA Registry indicate a high mortality due to COVID-19 in dialysis patients and kidney transplant recipients across Europe. Kidney Int. 2020;98:1540–1548. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2020.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hilbrands L.B., Duivenvoorden R., Vart P. COVID-19-related mortality in kidney transplant and dialysis patients: results of the ERACODA collaboration. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2020;35:1973–1983. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfaa261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haute Autorité de Santé Vaccins Covid-19: quelle stratégie de priorisation à l’initiation de la campagne? https://www.has-sante.fr/jcms/p_3221237/fr/vaccins-covid-19-quelle-strategie-de-priorisation-a-l-initiation-de-la-campagne Available at:

- 13.Baden L.R., El Sahly H.M., Essink B. Efficacy and safety of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:403–416. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2035389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Polack F.P., Thomas S.J., Kitchin N. Safety and efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:2603–2615. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2034577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Glenn D.A., Hegde A., Kotzen E. Systematic review of safety and efficacy of COVID-19 vaccines in patients with kidney disease. Kidney Int Rep. 2021;6:1407–1410. doi: 10.1016/j.ekir.2021.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sahin U., Muik A., Derhovanessian E. COVID-19 vaccine BNT162b1 elicits human antibody and T H 1 T cell responses. Nature. 2020;586:594–599. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2814-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Firth D. Bias reduction of maximum likelihood estimates. Biometrika. 1993;80:27–38. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lanzavecchia A. Antigen-specific interaction between T and B cells. Nature. 1985;314:537–539. doi: 10.1038/314537a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen C.-C., Koenig A., Saison C. CD4+ T cell help is mandatory for naive and memory donor-specific antibody responses: impact of therapeutic immunosuppression. Front Immunol. 2018;9:275. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.00275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Canas J.J., Starr M.C., Hooks J. Longitudinal SARS-CoV-2 seroconversion and functional heterogeneity in a pediatric dialysis unit. Kidney Int. 2021;99:484–486. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2020.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kovacic V., Sain M., Vukman V. Efficient haemodialysis improves the response to hepatitis B virus vaccination. Intervirology. 2002;45:172–176. doi: 10.1159/000065873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vaccinating_Dialysis_Patients_and_patients_dec2012.pdf. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/dialysis/PDFs/Vaccinating_Dialysis_Patients_and_patients_dec2012.pdf. Accessed April 2, 2021.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.