Abstract

Background & Aims

In patients with chronic liver disease (CLD) with or without cirrhosis, existing studies on the outcomes with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection have limited generalizability. We used the National COVID Cohort Collaborative (N3C), a harmonized electronic health record dataset of 6.4 million, to describe SARS-CoV-2 outcomes in patients with CLD and cirrhosis.

Methods

We identified all patients with CLD with or without cirrhosis who had SARS-CoV-2 testing in the N3C Data Enclave as of July 1, 2021. We used survival analyses to associate SARS-CoV-2 infection, presence of cirrhosis, and clinical factors with the primary outcome of 30-day mortality.

Results

We isolated 220,727 patients with CLD and SARS-CoV-2 test status: 128,864 (58%) were noncirrhosis/negative, 29,446 (13%) were noncirrhosis/positive, 53,476 (24%) were cirrhosis/negative, and 8941 (4%) were cirrhosis/positive patients. Thirty-day all-cause mortality rates were 3.9% in cirrhosis/negative and 8.9% in cirrhosis/positive patients. Compared to cirrhosis/negative patients, cirrhosis/positive patients had 2.38 times adjusted hazard of death at 30 days. Compared to noncirrhosis/positive patients, cirrhosis/positive patients had 3.31 times adjusted hazard of death at 30 days. In stratified analyses among patients with cirrhosis with increased age, obesity, and comorbid conditions (ie, diabetes, heart failure, and pulmonary disease), SARS-CoV-2 infection was associated with increased adjusted hazard of death.

Conclusions

In this study of approximately 221,000 nationally representative, diverse, and sex-balanced patients with CLD; we found SARS-CoV-2 infection in patients with cirrhosis was associated with 2.38 times mortality hazard, and the presence of cirrhosis among patients with CLD infected with SARS-CoV-2 was associated with 3.31 times mortality hazard. These results provide an additional impetus for increasing vaccination uptake and further research regarding immune responses to vaccines in patients with severe liver disease.

Keywords: COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, Cirrhosis, OMOP, N3C

Abbreviations used in this paper: AALD, alcohol-associated liver disease; aHR, adjusted hazard ratio; BMI, body mass index; CCI, Charlson Comorbidity Index; CI, confidence interval; CLD, chronic liver disease; EHR, electronic health record; HR, hazard ratio; ICD-10-CM, International Classification of Diseases; Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification; IQR, interquartile range; IRB, Institutional Review Board; MELD-Na, Model for End-Stage Liver Disease-Sodium; N3C, National COVID Cohort Collaborative; NAFLD, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease; NCATS, National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences; NIH, National Institutes of Health; OMOP, Observational Medical Outcomes Partnership; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2

In this study of 220,727 patients with liver disease, 30-day mortality was 8.9% for cirrhosis/severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2–positive patients, and severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection was associated with a 2.38 times hazard of death.

What You Need to Know.

Background and Context

We used the National COVID Cohort Collaborative (N3C), a harmonized EHR dataset of 6.4 million, to describe SARS-CoV-2 outcomes in patients with CLD and cirrhosis.

New Findings

In this study of 220,727 patients with liver disease, 30-day mortality was 8.9% for cirrhosis/SARS-CoV-2–positive patients and SARS-CoV-2 infection was associated with a 2.38-times hazard of death.

Limitations

Comparison population of cirrhosis/SARS-CoV-2–negative is likely sicker than the general cirrhosis population. There is substantial not-at-random missingness of multiple covariates.

Impact

This study corroborates previous research on the increased risk of adverse outcomes in cirrhosis/SARS-CoV-2–positive patients. This study provides additional impetus for increasing vaccine uptake among this vulnerable population.

Hepatic involvement is common in severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection, with clinical manifestations ranging from liver function test elevation to acute hepatic decompensation.1, 2, 3, 4 In patients with existing chronic liver diseases (CLD) and cirrhosis, the outcomes of SARS-CoV-2 infection have been mixed.5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 Previous small-scale studies from tertiary referral centers have demonstrated mortality rates approaching 40% for patients with cirrhosis who were infected by SARS-CoV-2.7 , 10 Other studies, however, have shown that patients with cirrhosis who test positive for SARS-CoV-2 infection had similar mortality rates compared to those patients hospitalized with complications of cirrhosis without SARS-CoV-2 infection.9

A study of patients with and without cirrhosis based on national data extracted from the US Department of Veterans Affairs Clinical Data Warehouse demonstrated that patients with cirrhosis were less likely to test positive for SARS-CoV-2 but, when positive, were 3.5 times more likely to die from all-causes compared to those who tested negative. Although this was one of the largest studies of outcomes of SARS-CoV-2 infection in patients with cirrhosis to date, 88% of the underlying patient population was male, limiting generalization to other patient populations.11

The National COVID Cohort Collaborative (N3C) was formed in April 2020 as a centralized resource of harmonized electronic health record (EHR) data from health systems around the United States.12 , 13 As of July 1, 2021, 214 clinical sites had signed data transfer agreements and 57 sites had harmonized data included in the N3C Data Enclave—a diverse and nationally representative central repository of harmonized EHR data and a new model for collaborative data sharing and analytics. Initial results up to December 2020 from the N3C main cohort have been characterized and described previously.14 To address the conflicting results and gaps of previous studies, we used the N3C Data Enclave to answer the following 3 distinct questions regarding outcomes of SARS-CoV-2 infection in patients with CLD:

-

1.

What is the association between SARS-CoV-2 and mortality in patients with CLD with cirrhosis?

-

2.

What is the association between cirrhosis and mortality in patients with CLD who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2?

-

3.

What are the factors associated with mortality among patients with CLD with cirrhosis who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2?

Methods

The National COVID Cohort Collaborative

The N3C is a centralized, curated, harmonized, secure, and nationally representative clinical data resource with embedded analytical capabilities. The N3C is composed of members from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Clinical and Translational Science Awards Program and its Center for Data to Health, IDeA Centers for Translational Research, National Patient-Centered Clinical Research Network, Observational Health Data Sciences and Informatics network, TriNetX, and Accrual to Clinical Trials network. N3C’s design, infrastructure, deployment, and initial analyses from the main N3C cohort have been described previously.12 , 14 N3C Data Enclave is a secure cloud-based implementation of Palantir Foundry (Palantir Technologies, Denver, CO) analytic suite hosted by the NIH National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS).12 , 14

The N3C Data Enclave includes EHR data of patients who were tested for SARS-CoV-2 or had related symptoms after January 1, 2020. For patients included in the N3C Data Enclave, encounters in the same source health system beginning on or after January 1, 2018 are also included to provide lookback data. N3C uses centrally maintained “shared logic sets” for common diagnostic and phenotype definitions.12 , 14 All EHR data in the N3C Data Enclave are harmonized in the Observational Medical Outcomes Partnership (OMOP) common data model, version 5.3.1.15 , 16 In the OMOP common data model, classification vocabularies, such as International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM), or Standard Nomenclature of Medicine; are mapped to standard OMOP concepts based on semantic and clinical relationships.17 Vocabulary classification and mapping of various ontologies to the OMOP standard vocabulary is maintained by Observational Health Data Sciences and Informatics Network and publicly available on ATHENA (http://athena.ohdsi.org/), which is a web-based vocabulary repository.18 For all analyses, we used the deidentified version of the N3C Data Enclave, versioned as of July 1, 2021 and accessed on July 3, 2021. To protect patient privacy, all dates in the N3C Data Enclave are uniformly shifted up to ±180 days within each partner site in the deidentified database.

Definition of SARS-CoV-2 Status

SARS-CoV-2 testing status was based on a modified version of the N3C shared logic set; specifically, OMOP concept identifiers signifying culture and nucleic acid amplification testing for SARS-CoV-2 (Supplementary Table 1) were queried among all patients included in the N3C Enclave.12 , 14 We did not query SARS-CoV-2 antibody testing, as this might be a marker of remote infection or vaccination rather than active infection. The “index date” for all analyses was defined as the date of the earliest positive test (for SARS-CoV-2–positive patients) or earliest negative test (for SARS-CoV-2–negative patients).11 Patients who underwent repetitive SARS-CoV-2 testing were classified based on the above definitions governing the earliest test. Patients who did not have SARS-CoV-2 testing by the above definitions (eg, those who were clinically diagnosed with “suspected COVID-19” or those with antibody testing only) were excluded. To account for uniform date shifting that occurs per partner site in the deidentified N3C Data Enclave, we calculated a “maximum data date” to reflect the last known date of records for each data partner and excluded patients who were tested <90 days of this “maximum data date.”

Definitions of Chronic Liver Disease and Cirrhosis

CLD diagnoses were made based on documentation of at least 1 OMOP concept identifier corresponding to previously validated ICD-10-CM codes for liver diseases (Supplementary Table 2) at any time before the index date.19, 20, 21, 22 As “steatosis of the liver” is a common finding in alcohol-associated liver disease (AALD) and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), patients with OMOP concept identifier 4059290 (corresponding to ICD-10-CM code K76.0) and at least 1 OMOP concept identifier describing alcohol use (Supplementary Table 2) in accordance with definitions by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Alcohol Epidemiologic Data System, were categorized as those with AALD.23, 24, 25, 26 Patients with OMOP concept identifier 4059290 without an alcohol use OMOP concept identifier were categorized as NAFLD.

Diagnoses were determined in a hierarchical manner such that NAFLD categorization was made only after exclusion of all other CLD causes. In those patients identified to have CLD, diagnoses of cirrhosis were made based on documentation of at least 1 OMOP concept identifier corresponding to previously validated ICD-10-CM codes for cirrhosis and its complications (Supplementary Table 2) at any time before the index date.12 , 27 Diagnoses of cirrhosis, therefore, can only take place in the setting of an existing CLD diagnosis. Patients who had undergone orthotopic liver transplantation (n = 12,170 patients) as signified by OMOP concept identifier 42537742 (corresponding to ICD-10-CM code Z94.4) were excluded from all analyses.

Study Design and Questions of Interest

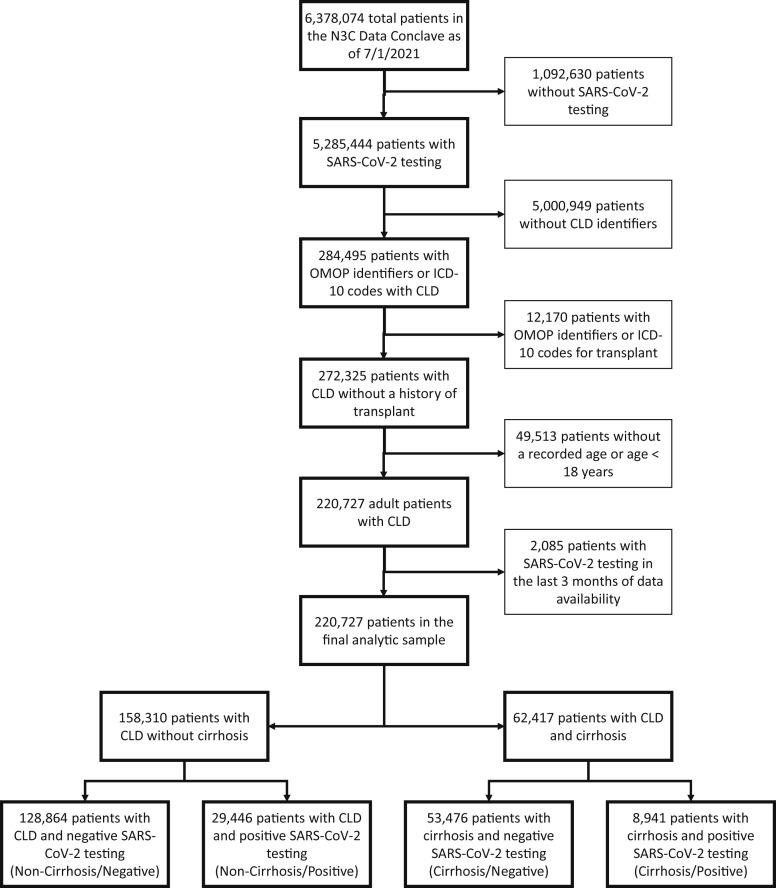

Using the above definitions for SARS-CoV-2 testing and chronic liver disease/cirrhosis; we isolated our adult patients (with age 18 years or older documented) study population. We divided the study patients into the following cohorts (Figure 1 ):

-

•

CLD without cirrhosis and SARS-CoV-2–negative: noncirrhosis/negative;

-

•

CLD without cirrhosis and SARS-CoV-2–positive: noncirrhosis/positive;

-

•

CLD with cirrhosis and SARS-CoV-2–negative: cirrhosis/negative; and

-

•

CLD with cirrhosis and SARS-CoV-2–positive: cirrhosis/positive.

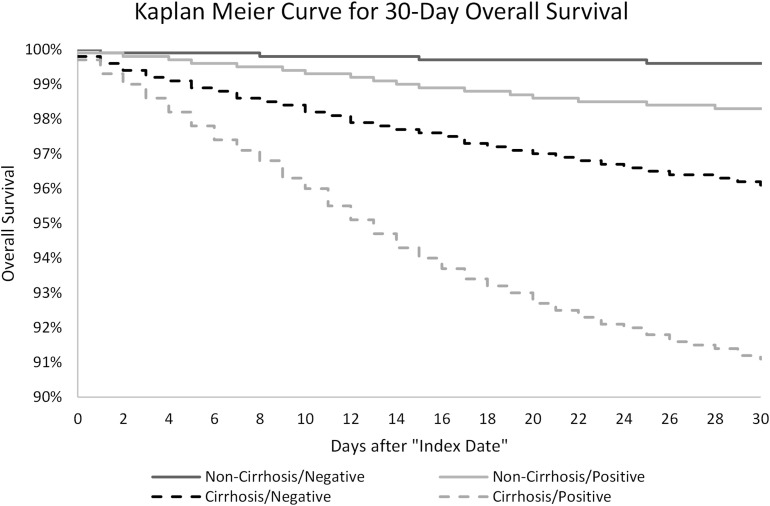

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier curve for 30-day overall survival.

Based on these cohorts, we investigated 3 questions or associations of interest concerning SARS-CoV-2 infection in patients with CLD with or without cirrhosis:

-

1.

What is the association between SARS-CoV-2 and all-cause mortality at 30 days in patients with CLD with cirrhosis? This a comparison between patients with CLD with cirrhosis who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 (cirrhosis/positive) and patients with CLD with cirrhosis who tested negative for SARS-CoV-2 (cirrhosis/negative).

-

2.

What is the association between cirrhosis and all-cause mortality at 30 days in patients with CLD who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2? This is a comparison between patients with CLD with cirrhosis who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 (cirrhosis/positive) and patients with CLD without cirrhosis who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 (noncirrhosis/positive).

-

3.

What are the demographic and clinical factors associated with all-cause mortality at 30 days among patients with CLD with cirrhosis who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 (cirrhosis/positive)?

Outcomes

All patients were followed until their last recorded visit occurrence, procedure, measurement, observation, or condition occurrence in the N3C Data Enclave. The primary outcome was all-cause mortality at 30 days after the index SARS-CoV-2 test date. Secondary outcomes included hospitalization within 30 and 90 days after the index date, mechanical ventilation within 30 and 90 days, and all-cause mortality at 90 days after the index date. The outcome of death was ascertained based on EHR data indicating in-hospital death, out-of-hospital death, or referral to hospice. The outcome of mechanical ventilation was ascertained by OMOP procedure or condition concepts. The outcome of hospitalization was ascertained based on recorded OMOP visits concepts. These outcomes were defined centrally based on concept sets in N3C shared logic and have been implemented on the full N3C cohort.12 , 14 To account for potential delays in data reporting/harmonization and outcome ascertainment from data partner sites, we had excluded all patients who had SARS-CoV-2 testing <90 days of the “maximum data date” as defined above.

Baseline Characteristics

Baseline demographic characteristics extracted from N3C Data Enclave included age, sex, race/ethnicity, height, weight, body mass index (BMI), and state of origin. States were classified into 4 geographic regions (Northeast, Midwest, South, and West) defined by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Respiratory and Enteric Virus Surveillance System.28 Patients were categorized as living in “other/unknown” region if they originated from territories not otherwise classified (eg, Guam, Puerto Rico, US Virgin Islands, or other dependencies) or if state of origin was censored to protect patient privacy in ZIP codes with few residents. We evaluated comorbid conditions based on the original Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI),29 , 30 consistent with central practices per the N3C consortium.14 As per definitions established in N3C shared logic, CCI comorbid conditions were extracted centrally using the ‘icd’ R package,14 , 31 which processes and categorizes diagnosis codes from raw data tables. To avoid double-counting liver-related comorbidities in our analyses, we calculated a modified CCI based on the original assigned weights for comorbidities (Supplementary Table 3), excluding “mild liver disease” and “severe liver disease.”

Components of common laboratory tests (basic metabolic panel, complete blood count, liver function tests, and serum albumin) were extracted based on N3C shared logic sets except for international normalized ratio, which we custom-defined based on standard OMOP concept identifiers (Supplementary Table 4). We extracted the most complete values to calculate the Model for End-Stage Liver Disease-Sodium (MELD-Na) score closest to or on the index date from within 30 days before to 7 days after the index date. Fifty-five percent of patients had laboratory tests performed within 2 days of the index date available; 17,653 patients, which represented 8% of the full analytical sample, had full laboratory data for calculation of MELD-Na scores. The time frame of 30 days before to 7 days after the index date was consistent with definitions used centrally by N3C to identify hospitalizations of interest in the main cohort.14

Statistical Analyses

Clinical characteristics and laboratory data were summarized with medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs) for continuous variables or numbers and percentages for categorical variables. Comparisons between groups were performed using χ2 and Kruskal-Wallis tests where appropriate. We used the Kaplan-Meier method to calculate 30-day and 90-day cumulative incidences of hospitalization, mechanical ventilation, and death. We used Cox proportional hazard models to evaluate the associations between SARS-CoV-2 and mortality among patients with cirrhosis, between cirrhosis and mortality among patients with CLD who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2, and factors with mortality for cirrhosis/positive patients. In all multivariable analyses, we adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, CLD etiology, CCI score, and region of origin.

We conducted stratified analyses based on categories of MELD-Na scores, categories of modified CCI scores, and selected comorbidities associated with worse outcomes in SARS-CoV-2 infection per central N3C data: obesity (defined as ≥30 kg/m2), diabetes, chronic renal disease, congestive heart failure, and chronic pulmonary disease. Lastly, as full MELD-Na scores and serum albumin values were available for 17,653 (8%) and 75,267 (34%) patients in the analytical sample, respectively, we conducted sensitivity analyses of models involving patients with cirrhosis. Two-sided P values <.05 were considered statistically significant in all analyses. Data queries, extractions, and transformations of OMOP data elements and concepts in the N3C Data Enclave were conducted using the Palantir Foundry implementations of Spark-Python, version 3.6, and Spark-SQL, version 3.0. Statistical analyses were performed using the Palantir Foundry implementation of Spark-R, version 3.5.1 “Feather Spray” (R Core Team, Vienna, Austria).32

Institutional Review Board Oversight

Submission of data from individual centers to N3C are governed by a central Institutional Review Board (IRB) protocol #IRB00249128 hosted at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine via the SMART IRB40 Master Common Reciprocal reliance agreement. This central IRB cover data contributions and transfer to N3C and does not cover research using N3C data. If elected, individual sites can choose to exercise their own local IRB agreements instead of using the central IRB. As NCATS is the steward of the repository, data received and hosted by NCATS on the N3C Data Enclave, its maintenance, and its storage are covered under a central NIH IRB protocol to make EHR-derived data available for the clinical and research community to use for studying COVID-19. Our institution has an active data transfer agreement with N3C. This specific analysis of the N3C Enclave was approved by N3C under the Data Use Agreement titled “[RP-7C5E62] COVID-19 Outcomes in Patients with Cirrhosis.” The use of N3C data for this study was authorized by the IRB at the University of California, San Francisco under #20-33149.

Results

As of July 1, 2021, fifty-seven sites that had completed data transfer were harmonized and integrated into the N3C Enclave. This included approximately 7.1 billion rows of data on 6,378,074 unique patients, of which 5,285,444 had at least 1 SARS-CoV-2 culture or nucleic acid amplification test. Of these approximately 5.3 million patients who had undergone testing, an analytical sample of 220,727 patients with CLD with or without cirrhosis was assembled, after applying exclusion criteria for transplant status, age, and date shifting in the N3C Enclave (Supplementary Figure 1). Based on SARS-CoV-2 test results, we divided the 220,727 patients with CLD into the following 4 cohorts: 128,864 (58%) noncirrhosis/negative, 29,446 (13%) noncirrhosis/positive, 53,476 (24%) cirrhosis/negative, and 8,941 (4%) cirrhosis/positive.

Supplementary Figure 1.

Isolation of patients with CLD with and without cirrhosis from the main N3C cohort.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

The baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of the 4 cohorts are presented in Table 1 . In general, the 4 cohorts differed significantly with regard to distributions of age, race/ethnicity, height, weight, BMI, etiologies of chronic liver disease, modified CCI scores, National Respiratory and Enteric Virus Surveillance System regions, and laboratory test values. Of note, patients with cirrhosis were less likely to be women: 53% of noncirrhosis/negative, 54% of noncirrhosis/positive, and 44% of cirrhosis/negative and 45% of cirrhosis/positive cohorts. Of CLD etiologies, there were notable differences in the distribution of patients with AALD: 34% and 28% of the cirrhosis/negative and cirrhosis/positive cohorts, respectively, compared to 6% and 7% of the noncirrhosis/negative and noncirrhosis/positive cohorts, respectively.

Table 1.

Baseline Demographic, Clinical, and Laboratory Characteristics of the 220,727 Patients With Chronic Liver Diseases With and Without Cirrhosis Included in the Analysis

| Characteristic | Noncirrhosis/negative (n = 128,864) | Noncirrhosis/positive (n = 29,446) | Cirrhosis/negative (n = 53,476) | Cirrhosis/positive (n = 8941) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex, female | 68,209 (53) | 15,947 (54) | 23,479 (44) | 4009 (45) | |||

| Age | 54 (42–64) | 53 (41–62) | 60 (50–67) | 61 (51–68) | |||

| 18–29 y | 8732 (7) | 2163 (7) | 1431 (3) | 229 (3) | |||

| 30–49 y | 42,408 (33) | 10,365 (35) | 11,315 (21) | 1696 (19) | |||

| 50–64 y | 48,582 (38) | 10,952 (37) | 22,528 (42) | 3702 (41) | |||

| 65+ y | 29,142 (23) | 5966 (20) | 18,202 (34) | 3314 (37) | |||

| Race/ethnicity | |||||||

| White | 80,114 (62) | 15,995 (54) | 35,308 (66) | 5055 (57) | |||

| Black/African-American | 19,524 (15) | 4291 (15) | 8701 (16) | 1701 (19) | |||

| Hispanic | 16,898 (13) | 5524 (19) | 5424 (10) | 1289 (14) | |||

| Asian | 4639 (4) | 968 (3) | 1203 (2) | 195 (2) | |||

| Unknown/other | 7689 (6) | 2668 (9) | 2840 (5) | 701 (8) | |||

| Height, cma | 170 (163–178) | 170 (163–178) | 170 (163–178) | 170 (163–178) | |||

| Weight, kga | 90 (75–107) | 94 (79–112) | 83 (69–100) | 86 (72–104) | |||

| BMI, kg/m2,a | 31 (27–37) | 33 (28–38) | 29 (24–34) | 30 (25–36) | |||

| BMI ≥30 kg/m2 | 46,239 (36) | 9405 (32) | 15,198 (28) | 2401 (27) | |||

| Liver disease etiology | |||||||

| NAFLD | 85,420 (66) | 21,237 (72) | 17,753 (33) | 3492 (39) | |||

| Hepatitis C | 27,657 (21) | 4691 (16) | 10,577 (20) | 1707 (19) | |||

| AALD | 8017 (6) | 1941 (7) | 17,980 (34) | 2518 (28) | |||

| Hepatitis B | 5406 (4) | 1170 (4) | 2173 (4) | 399 (4) | |||

| Cholestatic | 785 (1) | 100 (0) | 3158 (6) | 522 (6) | |||

| Autoimmune | 1579 (1) | 307 (1) | 1835 (3) | 303 (3) | |||

| Decompensated cirrhosis | 36,930 (69) | 5993 (67) | |||||

| Modified CCIb | 1 (0–3) | 1 (0–3) | 2 (0–5) | 3 (1–6) | |||

| Comorbidities | |||||||

| Diabetes | 39,865 (31) | 10,510 (36) | 20,954 (39) | 4339 (49) | |||

| Chronic renal disease | 11,660 (9) | 2651 (9) | 10,235 (19) | 2228 (25) | |||

| Congestive heart failure | 10,615 (8) | 2169 (7) | 10,235 (19) | 2044 (23) | |||

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 36,229 (28) | 7,391 (25) | 16,271 (30) | 2859 (32) | |||

| Region | |||||||

| Northeast | 14,940 (12) | 2664 (9) | 4273 (8) | 791 (9) | |||

| Midwest | 20,098 (16) | 4498 (15) | 10,345 (19) | 1574 (18) | |||

| South | 22,066 (17) | 3670 (12) | 9596 (18) | 1142 (13) | |||

| West | 16,462 (13) | 2560 (9) | 6367 (12) | 657 (7) | |||

| Other | 55,298 (43) | 16,054 (55) | 22,895 (43) | 4777 (53) | |||

| Laboratory testsa | |||||||

| Albumin, g/L | 4.0 (3.6–4.4) | 3.7 (3.1–4.1) | 3.4 (2.8–4.0) | 3.1 (2.6–3.7) | |||

| AST, u/L | 28 (20–47) | 33 (22–52) | 41 (25–74) | 43 (27–77) | |||

| ALT, u/L | 31 (19–56) | 37 (22–66) | 29 (18–51) | 32 (20–57) | |||

| Total bilirubin, mg/dL | 0.5 (0.4–0.7) | 0.4 (0.3–0.7) | 0.9 (0.5–2.0) | 0.8 (0.4–1.8) | |||

| Creatinine, mg/dL | 0.8 (0.7–1.0) | 0.8 (0.6–1.0) | 0.9 (0.7–1.2) | 0.9 (0.7–1.4) | |||

| INR | 241 (190–301) | 239 (184–311) | 174 (106–254) | 163 (99–252) | |||

| Platelet, 109/L | 13.0 (11.4–14.3) | 12.9 (11.4–14.1) | 11.3 (9.3–13.1) | 10.9 (9.0–12.8) | |||

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | 1.1 (1.0–1.2) | 1.1 (1.0–1.2) | 1.3 (1.1–1.7) | 1.3 (1.1–1.8) | |||

| Neutrophil, 109/L | 4.8 (3.4–6.8) | 4.2 (3.0–6.2) | 4.3 (2.9–6.6) | 4.3 (2.9–6.6) | |||

| Lymphocyte, 109/L | 1.8 (1.3–2.5) | 1.4 (1.0–2.0) | 1.3 (0.8–2.0) | 1.1 (0.7–1.7) | |||

| Neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio | 2.8 (1.8–4.6) | 2.5 (1.7–4.2) | 3.2 (2.0–5.6) | 3.7 (2.1–7.1) | |||

| MELD–Nac | 9 (7–13) | 10 (8–13) | 16 (11–24) | 17 (11–24) | |||

NOTE. Continuous variables are presented as median (IQR), ordinal and categorical variables are presented as n (%).

ALT, alanine transaminase; AST, aspartate transaminase; INR, international normalized ratio.

Height, weight, BMI, and laboratory tests exhibit a range of missingness from 38% to 88% of the total sample.

Modified CCI was calculated based on the original CCI score, excluding weights for “mild liver disease” and “severe liver disease.”

MELD-Na scores were calculated for 17,653 patients, which represent 8% of the total sample.

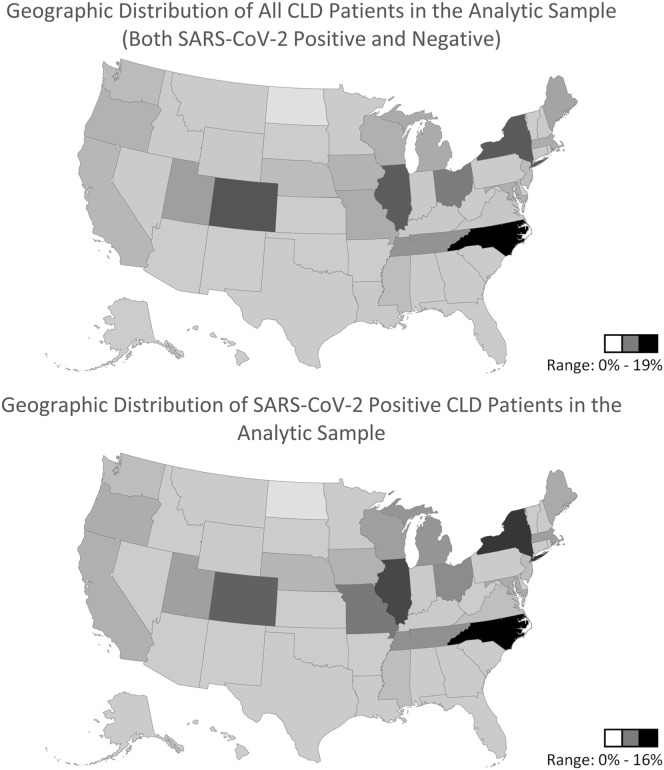

Full MELD-Na components were available with scores calculated in 17,653 patients, representing 8% of the total population. Among noncirrhosis patients, full MELD-Na components were available for 6866 of 158,310 patients (4%), the median MELD-Na was 9 (IQR, 7–13) and 10 (IQR, 8–13) in noncirrhosis/negative and noncirrhosis/positive patients, respectively. Among patients with cirrhosis, full MELD-Na components were available for 10,787 of 62,427 (17%) patients, median MELD-Na was 16 (IQR, 11–24) and 17 (IQR, 11–24) in cirrhosis/negative and cirrhosis/positive patients, respectively. For 121,703 patients with CLD (55%) whose location data were available, every state and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Respiratory and Enteric Virus Surveillance System region was represented, both in the full sample and among those with positive SARS-CoV-2 tests (Supplementary Figure 2).

Supplementary Figure 2.

Geographic distributions of CLD patients and CLD patients with positive SARS-CoV-2 testing in analytic sample.

Death, Hospitalization, and Mechanical Ventilation Rate

Cumulative incidences of outcomes of interest (30- and 90-day all-cause death, hospitalization, and mechanical ventilation) are presented in Table 2 . Thirty-day death rates increased progressively from 0.4% in noncirrhosis/negative patients to 1.7% in noncirrhosis/positive patients, and from 3.9% in cirrhosis/negative patients to 8.9% in cirrhosis/positive patients. Ninety-day death rates also increased progressively from 0.8% in noncirrhosis/negative patients to 2.3% in noncirrhosis/positive patients, and from 7.0% in cirrhosis/negative patients to 12.7% in cirrhosis/positive patients. Thirty- and 90-day mechanical ventilation rates also increased in a similar fashion based on SARS-CoV-2 status and presence of cirrhosis. Of note, 30-day and 90-day hospitalization rates were consistently higher among patients with cirrhosis compared to those patients without cirrhosis. Among both noncirrhosis and cirrhosis patients, those testing negative for SARS-CoV-2 had higher 30- and 90-day hospitalization rates. Kaplan-Meier curves for 30-day mortality among the 4 cohorts are presented in Figure 1.

Table 2.

Cumulative Incidences of Mortality, Mechanical Ventilation, and Hospitalization At 30 and 90 Days After Index Date

| Variable | Noncirrhosis/negative, % (n = 128,864) | Noncirrhosis/positive, % (n = 29,446) | Cirrhosis/negative, % (n = 53,476) | Cirrhosis/positive, % (n = 8,941) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hospitalization by day 30 | 27.2 (27–27.5) | 20.4 (19.9–20.9) | 48.8 (48.3–49.2) | 47.2 (46.1–48.2) |

| Hospitalization by day 90 | 29.4 (29.2–29.7) | 22.9 (22.1–23.1) | 51.7 (51.3–52.1) | 50.1 (49–51.2) |

| Mechanical ventilation by day 30 | 0.8 (0.7–0.8) | 1.8 (1.7–2) | 4.8 (4.6–5) | 8.8 (8.2–9.4) |

| Mechanical ventilation by day 90 | 0.9 (0.9–1) | 2.0 (1.8–2.1) | 6.0 (5.8–6.2) | 9.9 (9.3–10.5) |

| Mortality by day 30 | 0.4 (0.4–0.4) | 1.7 (1.6–1.9) | 3.9 (3.7–4) | 8.9 (8.3–9.5) |

| Mortality by day 90 | 0.8 (0.7–0.8) | 2.3 (2.1–2.4) | 7.0 (6.8–7.3) | 12.7 (12–13.4) |

NOTE. Values are presented as cumulative incidence rate (95% CI).

Association Between SARS-CoV-2 Infection and Death in Patients With Cirrhosis

In univariate analyses, compared to cirrhosis/negative patients, SARS-CoV-2 positivity (cirrhosis/positive) was associated with 2.37 times hazard of death within 30 days (hazard ratio [HR], 2.37; 95% confidence interval [CI], 2.18–2.58; P < .01). In multivariate analyses, compared to cirrhosis/negative patients, SARS-CoV-2 positivity (cirrhosis/positive) was associated with 2.38 times hazard of death within 30 days (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR], 2.38; 95% CI 2.18–2.59; P < .01) after adjusting for race/ethnicity, CLD etiology, modified CCI, and region.

Of note, age (aHR, 1.02; 95% CI, 1.01–1.02; P < .01), other/unknown race/ethnicity (aHR, 1.35; 95% CI, 1.16–1.58; P < .01), AALD as etiology (aHR, 1.47; 95% CI, 1.33–1.61; P < .01), and modified CCI (aHR, 1.06 per point; 95% CI, 1.05–1.07; P < .01) were associated with higher 30-day mortality hazards in multivariate analyses. Cholestatic liver disease as etiology (aHR, 0.66; 95% CI, 0.53–0.81; P < .01) and location in other/unknown region (aHR, 0.71; 95% CI, 0.62–0.82; P < .01) were associated with lower 30-day mortality hazards in multivariate analyses. Detailed results are presented in Table 3 .

Table 3.

Association of SARS-CoV-2 Infection With All-Cause 30-Day Mortality in Patients With Cirrhosis (Cirrhosis/Positive vs Cirrhosis/Negative)

| Variable | Univariable Cox regression |

Multivariable Cox regression |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | P value | aHR | 95% CI | P value | |

| SARS-CoV-2 infection | 2.37 | 2.18–2.58 | <.01 | 2.38 | 2.18–2.59 | <.01 |

| Age, y | 1.02 | 1.02–1.02 | <.01 | 1.02 | 1.01–1.02 | <.01 |

| Sex, female | 0.91 | 0.84–0.98 | .01 | 0.99 | 0.91–1.07 | .74 |

| Race/ethnicity, n (%) | ||||||

| White | Ref | — | — | Ref | — | — |

| Black/African American | 1.10 | 0.99–1.21 | .08 | 0.98 | 0.88–1.09 | .68 |

| Hispanic | 1.08 | 0.96–1.22 | .21 | 1.04 | 0.92–1.18 | .54 |

| Asian | 0.92 | 0.70–1.20 | .53 | 0.95 | 0.72–1.26 | .73 |

| Unknown/other | 1.32 | 1.14–1.53 | <.01 | 1.35 | 1.16–1.58 | <.01 |

| Etiology of liver disease, n (%) | ||||||

| NAFLD | Ref | — | — | Ref | — | — |

| Hepatitis C | 0.91 | 0.81–1.01 | .09 | 0.97 | 0.86–1.08 | .55 |

| AALD | 1.20 | 1.10–1.31 | <.01 | 1.47 | 1.33–1.61 | <.01 |

| Hepatitis B | 0.97 | 0.80–1.19 | .78 | 1.01 | 0.82–1.24 | .93 |

| Cholestatic | 0.60 | 0.49–0.74 | <.01 | 0.66 | 0.53–0.81 | <.01 |

| Autoimmune | 0.79 | 0.62–1.00 | .05 | 0.88 | 0.70–1.12 | .30 |

| Modified CCIa | 1.07 | 1.06–1.08 | <.01 | 1.06 | 1.05–1.07 | <.01 |

| Region | ||||||

| Northeast | Ref | — | — | Ref | — | — |

| Midwest | 0.87 | 0.79–1.08 | .06 | 0.92 | 0.79–1.07 | .26 |

| South | 0.95 | 0.84–1.15 | .49 | 1.06 | 0.91–1.23 | .47 |

| West | 0.77 | 0.69–0.98 | <.01 | 0.88 | 0.75–1.05 | .15 |

| Other | 0.71 | 0.65–0.87 | <.01 | 0.71 | 0.62–0.82 | <.01 |

Modified CCI was calculated based on the original CCI score, excluding weights for “mild liver disease” and “severe liver disease.”

Association Between Presence of Cirrhosis and Death in Patients With Chronic Liver Disease Who Tested SARS-CoV-2–Positive

In univariate analyses, compared to noncirrhosis/positive patients, the presence of cirrhosis (cirrhosis/positive) was associated with 5.34 times hazard of death within 30 days (HR, 5.34; 95% CI, 4.75–6.00; P < .01). In multivariate analyses, compared to noncirrhosis/positive patients, the presence of cirrhosis (cirrhosis/positive) was associated with a 3.31 times hazard of death within 30 days (aHR, 3.31; 95% CI, 2.91–3.77; P < .01) after adjusting for race/ethnicity, CLD etiology, CCI, and region.

Of note, age (aHR, 1.05 per year; 95% CI, 1.05–1.06; P < .01), Hispanic ethnicity (aHR, 1.20; 95% CI, 1.02–1.42; P = .03), other/unknown race (aHR, 1.25; 95% CI, 1.01–1.55; P = .04), chronic hepatitis C as etiology (aHR, 1.27; 95% CI, 1.08–1.48; P < .01), AALD as etiology (aHR, 1.40; 95% CI, 1.20–1.65; P < .01), and modified CCI (aHR, 1.07 per point; 95% CI, 1.05–1.08; P < .01) were associated with higher 30-day mortality hazards in multivariate analyses. Female sex (aHR, 0.84; 95% CI, 0.74–0.95; P < .01), location in the Midwest (aHR, 0.51; 95% CI, 0.41–0.62; P < .01), location in the South (aHR, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.61–0.91; P < .01), location in the West (aHR, 0.43; 95% CI, 0.33–0.57; P < .01) and other/unknown locations (aHR, 0.46; 95% CI, 0.39–0.54; P < .01) were associated with lower 30-day mortality hazards in multivariate analyses. Detailed results are presented in Table 4 .

Table 4.

Association of Presence of Cirrhosis With All-Cause 30-Day Mortality in All Patients With Chronic Liver Disease Who Tested Positive for SARS-CoV-2 Infection (Cirrhosis/Positive vs Noncirrhosis/Positive)

| Variable | Univariable Cox regression |

Multivariable Cox regression |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | P value | aHR | 95% CI | P value | |

| Presence of cirrhosis | 5.34 | 4.75–6.00 | <.01 | 3.31 | 2.91–3.77 | <.01 |

| Age, y | 1.07 | 1.06–1.07 | <.01 | 1.05 | 1.05–1.06 | <.01 |

| Sex, female | 0.65 | 0.58–0.73 | <.01 | 0.84 | 0.74–0.95 | <.01 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||

| White | Ref | — | — | Ref | — | — |

| Black/African American | 1.29 | 1.11–1.49 | <.01 | 0.98 | 0.83–1.15 | .80 |

| Hispanic | 0.95 | 0.81–1.2 | .54 | 1.20 | 1.02–1.42 | .03 |

| Asian | 1.11 | 0.81–1.54 | .51 | 1.38 | 0.99–1.92 | .06 |

| Unknown/other | 1.04 | 0.84–1.29 | .69 | 1.25 | 1.01–1.55 | .04 |

| Etiology of liver disease | ||||||

| NAFLD | Ref | — | — | Ref | — | — |

| Hepatitis C | 1.86 | 1.61–2.16 | <.01 | 1.27 | 1.08–1.48 | <.01 |

| AALD | 2.55 | 2.20–2.96 | <.01 | 1.40 | 1.20–1.65 | <.01 |

| Hepatitis B | 1.44 | 1.08–1.91 | .01 | 0.93 | 0.70–1.25 | .65 |

| Cholestatic | 1.95 | 1.34–2.85 | <.01 | 0.74 | 0.51–1.09 | .13 |

| Autoimmune | 2.00 | 1.38–2.91 | <.01 | 1.19 | 0.82–1.73 | .37 |

| Modified CCIa | 1.18 | 1.16–1.19 | <.01 | 1.07 | 1.05–1.08 | <.01 |

| Region | ||||||

| Northeast | Ref | — | — | Ref | — | — |

| Midwest | 0.49 | 0.40–0.59 | <.01 | 0.51 | 0.41–0.62 | <.01 |

| South | 0.65 | 0.53–0.78 | <.01 | 0.75 | 0.61–0.91 | <.01 |

| West | 0.30 | 0.23–0.40 | <.01 | 0.43 | 0.33–0.57 | <.01 |

| Other | 0.40 | 0.34–0.47 | <.01 | 0.46 | 0.39–0.54 | <.01 |

Modified CCI was calculated based on the original CCI score, excluding weights for “mild liver disease” and “severe liver disease.”

Factors Associated With 30-Day Mortality Among Cirrhosis/Positive Patients

Demographic and clinical factors associated with all-cause 30-day mortality among cirrhosis/positive patients are presented in Table 5 . In univariate analyses, we found that age (HR, 1.04 per year; 95% CI, 1.03–1.04; P < .01), other/unknown race (HR, 1.30; 95% CI, 1.00–1.67; P = .05), and modified CCI (HR, 1.06; 95% CI, 1.05–1.08; P < .01) were associated with higher risk of 30-day mortality among cirrhosis/positive patients. Cholestatic liver diseases (HR, 0.62; 95% CI, 0.42–0.91; P = .02), location in the Midwest (HR, 0.72; 95% CI, 0.41–0.69; P < .01), location in the South (HR, 0.72; 95% CI, 0.56–0.94; P = .01), location in the West (HR, 0.58; 95% CI, 0.42–0.81; P < .01), and other/unknown locations (HR, 0.51; 95% CI, 0.41–0.63; P < .01) were associated with lower hazards of mortality in univariate analyses.

Table 5.

Factors Associated With All-Cause 30-Day Mortality Among Patients With Cirrhosis Who Tested Positive for SARS-Cov-2 Infection (Cirrhosis/Positive Patients Only)

| Variable | Univariable Cox regression |

Multivariable Cox regression |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | P value | aHR | 95% CI | P value | |

| Age, y | 1.04 | 1.03–1.04 | <.01 | 1.04 | 1.03–1.04 | <.01 |

| Sex, female | 0.98 | 0.84–1.13 | .81 | 1.04 | 0.89–1.21 | .60 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||

| White | Ref | — | — | Ref | — | — |

| Black/African American | 0.97 | 0.80–1.18 | .77 | 0.94 | 0.76–1.15 | .55 |

| Hispanic | 1.14 | 0.93–1.40 | .20 | 1.16 | 0.94–1.44 | .16 |

| Asian | 1.06 | 0.65–1.72 | .82 | 1.08 | 0.66–1.77 | .76 |

| Unknown/other | 1.30 | 1.00–1.67 | .05 | 1.43 | 1.10–1.85 | <.01 |

| Etiology of liver disease | ||||||

| NAFLD | Ref | — | — | Ref | — | — |

| Hepatitis C | 0.93 | 0.76–1.14 | .48 | 0.94 | 0.76–1.16 | .56 |

| AALD | 1.03 | 0.87–1.23 | .70 | 1.22 | 1.01–1.46 | .03 |

| Hepatitis B | 0.89 | 0.61–1.29 | .53 | 0.87 | 0.59–1.27 | .47 |

| Cholestatic | 0.62 | 0.42–0.91 | .02 | 0.63 | 0.43–0.93 | .02 |

| Autoimmune | 0.95 | 0.63–1.42 | .79 | 1.05 | 0.70–1.59 | .81 |

| Modified CCIa | 1.06 | 1.05–1.08 | <.01 | 1.04 | 1.02–1.06 | <.01 |

| Region | ||||||

| Northeast | Ref | — | — | Ref | — | — |

| Midwest | 0.53 | 0.41–0.69 | <.01 | 0.60 | 0.46–0.78 | <.01 |

| South | 0.72 | 0.56–0.94 | .02 | 0.84 | 0.64–1.10 | .20 |

| West | 0.58 | 0.42–0.81 | <.01 | 0.71 | 0.51–0.99 | .04 |

| Other | 0.51 | 0.41–0.63 | <.01 | 0.53 | 0.45–0.71 | <.01 |

Modified CCI was calculated based on the original CCI score excluding weights for “mild liver disease” and “severe liver disease.”

In multivariate analyses, age (aHR, 1.04 per year; 95% CI, 1.03–1.04; P < .01), other/unknown race (aHR, 1.43; 95% CI, 1.10–1.85; P < .01), AALD as etiology (aHR, 1.22; 95% CI, 1.01–1.46; P = .03), and modified CCI (aHR, 1.04; 95% CI, 1.02–1.06; P < .01) were associated with higher hazards of 30-day mortality. Cholestatic liver diseases (aHR, 0.63; 95% CI, 0.43–0.93; P = .02), location in the Midwest (aHR, 0.60; 95% CI, 0.46–0.78; P < .01), location in the West (aHR, 0.71; 95% CI, 0.51–0.99; P = .04), and other/unknown location (aHR, 0.53; 95% CI, 0.45–0.71; P < .01) were associated with lower hazards of 30-day mortality in multivariate analyses.

Stratified Analyses of Clinical Factors and Comorbidities Associated With Adverse Outcomes

Stratified analyses of the contributions of various clinical factors and comorbidities to associations with 30-day mortality among patients with cirrhosis are presented in Table 6 . Among patients with compensated cirrhosis (defined as those without OMOP concept identifiers associated with variceal bleeding, ascites, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, hepatic encephalopathy, hepatorenal syndrome, or hepatopulmonary syndrome), SARS-CoV-2 positivity (cirrhosis/positive) was associated with 5.00 times adjusted hazard of death within 30 days (aHR, 5.00; 95% CI, 3.92–6.37; P < .01) compared to cirrhosis/negative patients. Among patients with decompensated cirrhosis, SARS-CoV-2 positivity (cirrhosis/positive) was associated with 2.20 times adjusted hazard of death within 30 days (aHR, 2.20; 95% CI, 2.01–2.42; P < .01) compared to cirrhosis/negative patients.

Table 6.

Association of SARS-Cov-2 Infection With All-Cause 30-Day Mortality in Patients With Cirrhosis (Cirrhosis/Positive vs Cirrhosis/Negative) Stratified by Age, Body Mass Index, MELD-Na Score, and Selected Comorbidities

| Cirrhosis/positive vs cirrhosis/negative | Cirrhosis/ negative, n (%) | Death at 30d, cumulative incidence rate, % (95% CI) | Cirrhosis/ positive, n (%) | Death at 30d, cumulative incidence rate, % (95% CI) | aHR (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All patients | 53,476 (100) | 3.9 (3.7–4.0) | 8941 (100) | 8.9 (8.3–9.5) | 2.38 (2.18–2.59) | <.01 |

| Compensated | 16,546 (31) | 0.9 (0.8–1.1) | 2948 (33) | 4.7 (3.9–5.5) | 5.00 (3.92–6.37) | <.01 |

| Decompensated | 36,930 (69) | 5.2 (4.9–5.4) | 5993 (67) | 11.0 (10.1–11.8) | 2.20 (2.01–2.41) | <.01 |

| Stratified by agea | ||||||

| 18–29 y | 1431 (3) | 2.0 (1.2–2.7) | 229 (3) | 3.7 (1.1–6.1) | 1.84 (0.81–4.16) | .14 |

| 30–49 y | 11,315 (21) | 3.2 (2.9–3.5) | 1696 (19) | 4.8 (3.7–5.9) | 1.59 (1.23–2.05) | <.01 |

| 50–64 y | 22,528 (42) | 3.8 (3.6–4.1) | 3702 (41) | 7.6 (6.7–8.4) | 2.05 (1.78–2.35) | <.01 |

| 65 y or older | 18,202 (34) | 4.4 (3.1–4.7) | 3314 (37) | 12.9 (11.7–14.1) | 3.03 (2.68–3.42) | <.01 |

| Stratified by BMI | ||||||

| No BMI data | 18,096 (34) | 3.9 (3.6–4.1) | 4197 (47) | 8.4 (7.5–9.3) | 2.23 (1.95–2.55) | <.01 |

| BMI available | 35,380 (66) | 3.9 (3.7–4.1) | 4744 (53) | 9.4 (8.5–10.2) | 2.40 (2.15–2.68) | <.01 |

| BMI <25 kg/m2 | 10,143 (19) | 4.5 (4.1–4.9) | 1107 (12) | 10.5 (8.6–12.4) | 2.11 (1.70–2.62) | <.01 |

| BMI 25–30 kg/m2 | 10,039 (19) | 3.8 (3.4–4.2) | 1236 (14) | 8.8 (7.1–10.4) | 2.30 (1.84–2.87) | <.01 |

| BMI 30–35 kg/m2 | 7429 (14) | 3.5 (3.1–3.9) | 1048 (12) | 8.7 (7.0–10.5) | 2.51 (1.96–3.22) | <.01 |

| BMI ≥35 kg/m2 | 7769 (15) | 3.5 (3.1–4.0) | 1353 (15) | 9.5 (7.9–11.1) | 2.74 (2.21–3.40) | <.01 |

| Stratified by MELD-Na | ||||||

| No MELD-Na data | 44,096 (82) | 2.6 (2.4–2.7) | 7534 (84) | 6.9 (6.3–7.4) | 2.75 (2.47–3.07) | <.01 |

| MELD-Na available | 9380 (18) | 9.9 (9.3–10.5) | 1407 (16) | 19.6 (17.4–21.7) | 2.06 (1.79–2.38) | <.01 |

| MELD-Na 6–15 | 4257 (8) | 1.8 (1.4–2.2) | 581 (6) | 6.8 (4.7–8.9) | 3.49 (2.32–5.23) | <.01 |

| MELD-Na 15–20 | 1726 (3) | 4.1 (3.1–5.0) | 284 (3) | 13.3 (9.1–17.2) | 2.91 (1.92–4.42) | <.01 |

| MELD-Na 20–25 | 1298 (2) | 9.6 (8.0–11.2) | 233 (3) | 22.4 (16.7–27.7) | 2.27 (1.61–3.18) | <.01 |

| MELD-Na 25–30 | 827 (2) | 20.0 (17.2–22.8) | 129 (1) | 34.3 (25.2–42.4) | 1.68 (1.18–2.40) | <.01 |

| MELD-Na 30–35 | 451 (1) | 34.7 (30.0–39.2) | 62 (1) | 49.9 (34.7–61.6) | 1.44 (0.94–2.20) | .09 |

| MELD-Na na ≥35 | 821 (2) | 41.8 (38.2–45.2) | 118 (1) | 61.1 (50.7–69.3) | 1.36 (1.03–1.79) | .03 |

| Stratified by modified CCIb | ||||||

| Modified CCI 0 | 13,728 (26) | 3.6 (3.2–3.9) | 1936 (22) | 7.2 (6.0–8.5) | 2.08 (1.70–2.55) | <.01 |

| Modified CCI 1–2 | 15,357 (29) | 3.2 (2.9–3.5) | 2441 (27) | 7.7 (6.6–8.8) | 2.57 (2.15–3.06) | <.01 |

| Modified CCI 3–4 | 9291 (17) | 3.5 (3.1–3.9) | 1550 (17) | 8.4 (7.0–9.8) | 2.54 (2.06–3.14) | <.01 |

| Modified CCI ≥5 | 15,100 (28) | 5.0 (4.6–5.3) | 3014 (34) | 11.2 (10.0–12.4) | 2.37 (2.08–2.71) | <.01 |

| Stratified by comorbidities | ||||||

| No diabetes | 32,522 (61) | 3.9 (3.7–4.1) | 4602 (51) | 8.5 (7.6–9.3) | 2.28 (2.02–2.56) | <.01 |

| Diabetes | 20,954 (39) | 3.8 (3.6–4.1) | 4339 (49) | 9.4 (8.5–10.3) | 2.58 (2.28–2.92) | <.01 |

| No renal disease | 43,241 (81) | 3.5 (3.3–3.6) | 6713 (75) | 7.9 (7.2–8.6) | 2.39 (2.15–2.65) | <.01 |

| Renal disease | 10,235 (19) | 5.5 (5.1–6.0) | 2228 (25) | 12.0 (10.6–13.4) | 2.30 (1.98–2.67) | <.01 |

| No heart failure | 43,241 (81) | 3.5 (3.3–3.7) | 6897 (77) | 7.9 (7.2–8.5) | 2.34 (2.12–2.60) | <.01 |

| Heart failure | 10,235 (19) | 5.4 (4.9–5.8) | 2044 (23) | 12.5 (11.0–13.9) | 2.45 (2.10–2.85) | <.01 |

| No pulmonary disease | 37,205 (70) | 3.9 (3.7–4.1) | 6082 (68) | 8.5 (7.8–9.3) | 2.27 (2.04–2.52) | <.01 |

| Pulmonary disease | 16,271 (30) | 3.8 (3.5–4.1) | 2859 (32) | 9.7 (8.6–10.8) | 2.63 (2.27–3.05) | <.01 |

NOTE. Categorical variables are presented as n (%). Unless otherwise noted, aHRs are reported from multivariable model adjusting for age, sex, race/ethnicity, etiology of liver disease, modified CCI, and region.

Adjusted HRs for stratified age group analyses are reported from multivariable model adjusting for sex, race/ethnicity, etiology of liver disease, modified CCI, and region.

Modified CCI was calculated based on the original CCI score, excluding weights for “mild liver disease” and “severe liver disease.” Adjusted HRs are reported from multivariable model adjusting for age, sex, race/ethnicity, etiology of liver disease, and region.

In general, within stratified categories of age, the aHRs of death within 30 days for cirrhosis/positive compared to cirrhosis/negative patients increased from aHR of 1.59 (age 30–49 years) to aHR of 3.03 (age 65 years or older). Within stratified categories of BMI, the aHRs also increased from aHR of 2.11 (BMI <25 kg/m2) to aHR of 2.74 (BMI ≥35 kg/m2). Within stratified categories of MELD-Na scores, however, the aHRs deceased from aHR of 3.49 (MELD-Na 6–15) to aHR of 1.36 (MELD-Na ≥35). A similar trend was also seen within stratified categories of the Modified CCI: the aHRs decreased from aHR of 2.57 (score 1–2) to aHR of 2.37 (score ≥5).

When stratified based on comorbid conditions, the aHRs of death within 30 days for cirrhosis/positive compared to cirrhosis/negative patients increased in the presence of diabetes (aHR, 2.58 vs aHR, 2.28 for no diabetes), heart failure (aHR, 2.45 vs aHR, 2.34 for no heart failure), and pulmonary disease (aHR, 2.63 vs aHR, 2.27 for no pulmonary disease). When stratified based on chronic renal disease, however, the aHRs were lower for those with renal disease (aHR, 2.34 vs aHR, 2.30 for no renal disease).

Sensitivity Analyses With Model for End-Stage Liver Disease-Sodium and Serum Albumin

As calculated MELD-Na scores were available for only 17,653 patients (8%) and serum albumin values were available for 75,267 patients (34%), we conducted sensitivity analyses to determine the influence of these variables on the above multivariate models comparing patients with cirrhosis (Supplementary Table 5). For the multivariate model evaluating the association of SARS-CoV-2 infection with death in patients with cirrhosis, further adjustments for MELD-Na and serum albumin did not change the significance of the association (aHR, 1.66–2.38). For the multivariate model evaluating factors associated with death among cirrhosis/positive patients, further adjustments for MELD-Na and serum albumin did not change the significance of the association for age and death (aHR, 1.02–1.05). These adjustments for MELD-Na and serum albumin did, however, eliminate the associations of race/ethnicity (unknown/other), AALD as CLD etiology, modified CCI with increased hazard of death. Similarly, these adjustments eliminate the associations of cholestatic liver disease as CLD etiology and location (Midwest, West, and other/unknown) with decreased hazards of death.

Discussion

In this study of nearly 221,000 patients with CLD in the National COVID Cohort Collaborative, we found that SARS-CoV-2 infection was associated with 2.38 times hazard of all-cause mortality within 30 days among patients with cirrhosis. Among all patients with CLD (with and without cirrhosis) who tested SARS-CoV-2–positive, the presence of cirrhosis was associated with 3.31 times hazard of all-cause mortality within 30 days. Our results are consistent with previous studies of patients with CLD with and without cirrhosis, but our use of the N3C Data Enclave has several unique features that enhance the generalizability of our results and advance our understanding of SARS-CoV-2 infection in patients with CLD. The number of clinical sites included in this study (harmonized data from 57 as of July 1, 2021) confers a major strength to this study in terms of the number of patients, national scope, and demographic representation. Notably, 51% of the participants were women and 32% were racial/ethnic minorities: 16% identified as Black/African American, 13% Hispanic, and 3% Asian.

In addition, compared to previous studies, which only included data in the early phases of the COVID-19 pandemic, this study covers a longer duration up to July 2021 and reflects changes in treatment and therapy advances. For example, we found a lower cumulative incidence of all-cause 30-day mortality at 8.9% for cirrhosis/positive patients compared to previous studies with estimates up to 17%.12 Consistent with previous studies, we also found comparatively higher hospitalization rates in SARS-CoV-2 negative groups (noncirrhosis/negative and cirrhosis/negative) likely due to changes in healthcare delivery during the COVID-19 pandemic as standardized testing before hospital admissions and procedures became widespread.33 , 34

With regard to demographic and clinical factors associated with adverse outcomes in SARS-CoV-2 infection, our findings were also consistent with existing literature. We found female sex was associated with a lower hazard of death (aHR, 0.84; 95% CI, 0.74–0.95; P < .01) among all Patients with CLD with SARS-CoV-2 infection (Table 4). This sex association, however, did not remain once we stratified to only cirrhosis/positive. Consistent with extensive racial/ethnic disparities described,35 , 36 we found an increased hazard of mortality for those who identified as Hispanic (aHR, 1.20; 95% CI, 1.02–1.42; P = .03) and those who identified as other/unknown (aHR, 1.25; 95% CI, 1.01–1.55; P = .04) among Patients with CLD with positive SARS-CoV-2 test (Table 4). When we stratified to only cirrhosis/positive patients, we found that this association between Hispanic ethnicity and mortality was no longer significant. The reasons for this are likely multifactorial and reflect present disparities in differential rates of SARS-CoV-2 infection,35 , 36 and longstanding disparities in access to treatment for liver diseases in the United States.37, 38, 39 The broader questions regarding sex and racial/ethnic disparities during the COVID-19 pandemic are active areas of exploration among several N3C teams.12, 13, 14

To further understand risk factors and patterns associated with adverse outcomes in SARS-CoV-2 infection, we conducted stratified analyses comparing mortality between cirrhosis/positive and cirrhosis/negative patients (Table 6). Consistent with previous literature,40, 41, 42, 43 we found that age, obesity, and comorbid conditions (ie, diabetes, heart failure, and pulmonary disease) were significant cofactors in increasing the mortality risk for patients with cirrhosis when infected with SARS-CoV-2. For instance, among patients with cirrhosis between the ages of 30 and 49 years, the adjusted hazard of 30-day mortality associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection was 1.59; this adjusted hazard increased to 3.03 among those who were older than 65 years. Similarly, among patients with cirrhosis with BMIs <25 kg/m2, the adjusted hazard of 30-day mortality associated SARS-CoV-2 infection was 2.11; this adjusted hazard increased to 2.74 among patients with cirrhosis with BMIs ≥35 kg/m2. Interestingly, we found that the aHRs of 30-day mortality decreased when we stratified by MELD-Na score categories. This is likely due to high baseline mortality rates seen among patients with more severe liver disease regardless of SARS-CoV-2 infection, for example, cumulative incidence of death at 30 days of 41.8% among cirrhosis/negative patients with MELD-Na score ≥35. A similar phenomenon was seen with increasing modified CCI scores, in which the aHRs decreased when we stratified by higher score categories. This is also likely due to a higher baseline mortality rate among cirrhosis/negative patients with higher comorbidity scores. We did not include smoking status in our stratified analyses, as there have been data ascertainment issues (as missingness was only suggestive of non-smoking status) per discussions with central N3C teams.

Due to the methodology by which we derived our SARS-CoV-2–negative comparison populations (noncirrhosis/negative and cirrhosis/negative), we likely introduced selection bias, as these cohorts were more likely to undergo procedures or be hospitalized. These comparison populations, therefore, do not reflect baseline populations of patients with CLD with and without cirrhosis. As such, the aHRs for 30-day mortality associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection among patients with cirrhosis and various comorbidity categories calculated in this study may be an underestimate of the true HR, as our comparison populations were more clinically ill.

We acknowledge the following limitations. First, N3C is a collaboration among multiple NCATS-supported Clinical and Translational Science Awards program hubs and, therefore, has an overrepresentation of tertiary academic medical centers as data partners, which limits the generalizability of the study. Moreover, there is substantial oversampling of data from certain states—notably North Carolina, New York, Illinois, and Colorado. The national scope and sex/demographic characteristics of our study population, however, are unique strengths of this study compared to previous research. Second, as data were aggregated from many sites, there is systematic missingness of certain variables. In our study, this is most apparent in that we were only able to calculate the MELD-Na scores for 17,653 patients. We accounted for this by conducting sensitivity analyses that showed our main findings did not change. In addition, our sensitivity analyses revealed that certain geographic and CLD etiology associations with mortality were eliminated once adjustments were made in cirrhosis/positive patients. This most likely reflected not-at-random data missingness in N3C. Third, although N3C has standardized protocols for data curation and harmonization, there likely remains variations in terminology and ontology between sites. The use of the OMOP common data model, however, decreases such differences and enforces a degree of standardization.15 , 16 , 44

Fourth, due to date-shifting employed in the process of de-identification in the N3C Data Enclave and differences in data harmonization times between data partner sites, there may be a delay in ascertainment of outcomes. There may be misclassification of outcomes if the date of SARS-CoV-2 testing was close to the latest known date of records (“maximum data date”) for that site. To account for these issues, we employed 2 methods: 1. We attempted to maximize follow-up for each patient by defining last follow-up as any encounters or records (visit occurrence, procedure, measurement, observation, or condition occurrence) in the OMOP data model. 2. We excluded patients whose date of SARS-CoV-2 testing was within 90 days of the maximum data date—this exclusion criterion affected only 1% of potential patients to be included in the analytical sample.

Fifth, we used the deidentified version of the N3C Data Enclave to conduct our analyses. To protect patient privacy, date shifting was uniformly applied. This means that our analyses could not investigate temporal trends with each COVID-19 surge in the United States. Lastly, there is likely misclassification between patients with AALD and NAFLD given the nonspecific nature of OMOP concept identifier 4059290 “steatosis of the liver” (corresponding to ICD-10 code K76.0). This is most apparent in only 6% of patients with CLD without cirrhosis who were classified to have AALD, while 33% of patients with cirrhosis were classified with AALD (due to more specific ICD-10 codes for cirrhosis due to AALD).

Despite these limitations, our study is one of the largest studies of outcomes of SARS-CoV-2 infection in patients with CLDs with and without cirrhosis to date. Our results are consistent with those from previous studies and show that SARS-CoV-2 infection is associated with an increased risk of all-cause mortality among patients with cirrhosis. This study provides an additional impetus for increasing vaccine uptake among patients with cirrhosis.45 In addition, as patients with advanced liver diseases have well-recognized immune dysfunction with attenuated immune responses to other vaccines,46, 47, 48, 49 further research is urgently needed regarding immune responses to COVID-19 vaccines in patients with CLD to guide public health recommendations. Given the continued expansion of N3C and ongoing acquisition of longitudinal data, our study in the N3C Data Enclave lays the foundation for studying future potential clinical questions, such as clinical responses to vaccinations, which affect liver disease patients as the COVID-19 pandemic continues to evolve.50

Acknowledgments

N3C Consortium members: Jeremy R. Harper, Owl Health Works LLC, Indianapolis, IN; Christopher G. Chute, DrPH, MD, MPH, Schools of Medicine, Public Health, and Nursing, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD; and Melissa A. Haendel, PhD, Center for Health AI, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora, CO.

The analyses described in this publication were conducted with data or tools accessed through the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) N3C Data Enclave covid.cd2h.org/enclave and supported by NCATS U24 TR002306. This research was possible because of the patients whose information is included within the data from participating organizations (covid.cd2h.org/dtas) and the organizations and scientists (covid.cd2h.org/duas) who have contributed to the ongoing development of this community resource.

The N3C data transfer to NCATS is performed under a Johns Hopkins University Reliance Protocol IRB00249128 or individual site agreements with National Institutes of Health (NIH). The N3C Data Enclave is managed under the authority of the NIH; information can be found at https://ncats.nih.gov/n3c/resources.

The authors gratefully acknowledge contributions from the following N3C core teams (∗ asterisk denotes corresponding team leads): principal investigators: Melissa A. Haendel,∗ Christopher G. Chute,∗ Kenneth R. Gersing, Anita Walden; workstream, subgroup and administrative leaders: Melissa A. Haendel,∗ Tellen D. Bennett, Christopher G. Chute, David A. Eichmann, Justin Guinney, Warren A. Kibbe, Hongfang Liu, Philip R.O. Payne, Emily R. Pfaff, Peter N. Robinson, Joel H. Saltz, Heidi Spratt, Justin Starren, Christine Suver, Adam B. Wilcox, Andrew E. Williams, Chunlei Wu; key liaisons at data partner sites; regulatory staff at data partner sites; individuals at the sites who are responsible for creating the datasets and submitting data to N3C; data ingest and harmonization team: Christopher G. Chute,∗ Emily R. Pfaff,∗ Davera Gabriel, Stephanie S. Hong, Kristin Kostka, Harold P. Lehmann, Richard A. Moffitt, Michele Morris, Matvey B. Palchuk, Xiaohan Tanner Zhang, Richard L. Zhu; phenotype team (Individuals who create the scripts that the sites use to submit their data, based on the COVID and long COVID definitions): Emily R. Pfaff,∗ Benjamin Amor, Mark M. Bissell, Marshall Clark, Andrew T. Girvin, Stephanie S. Hong, Kristin Kostka, Adam M. Lee, Robert T. Miller, Michele Morris, Matvey B. Palchuk, Kellie M. Walters; project management and operations team: Anita Walden,∗ Yooree Chae, Connor Cook, Alexandra Dest, Racquel R. Dietz, Thomas Dillon, Patricia A. Francis, Rafael Fuentes, Alexis Graves, Andrew J. Neumann, Shawn T. O'Neil, Andréa M. Volz, Elizabeth Zampino; partners from NIH and other federal agencies: Christopher P. Austin,∗ Kenneth R. Gersing,∗ Samuel Bozzette, Mariam Deacy, Nicole Garbarini, Michael G. Kurilla, Sam G. Michael, Joni L. Rutter, Meredith Temple-O'Connor; analytics team (individuals who build the Enclave infrastructure, help create codesets, variables, and help Domain Teams and project teams with their datasets): Benjamin Amor,∗ Mark M. Bissell, Katie Rebecca Bradwell, Andrew T. Girvin, Amin Manna, and Nabeel Qureshi.

The authors thank the Publication Committee for their review of this publication to ensure compliance with International Committee of Medical Journal Editors guidelines, the N3C User Code of Conduct, and appropriate author attribution; Publication Committee Review Team: Carolyn Bramante, Jeremy R. Harper, Wendy Hernandez, Farrukh M. Koraishy, Saidulu Mattapally, Amit Saha, Satyanarayana Vedula; Stony Brook University—U24TR002306, University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center—U54GM104938: Oklahoma Clinical and Translational Science Institute, West Virginia University—U54GM104942: West Virginia Clinical and Translational Science Institute, University of Mississippi Medical Center—U54GM115428: Mississippi Center for Clinical and Translational Research, University of Nebraska Medical Center—U54GM115458: Great Plains IDeA-Clinical & Translational Research, Maine Medical Center—U54GM115516: Northern New England Clinical & Translational Research Network, Wake Forest University Health Sciences—UL1TR001420: Wake Forest Clinical and Translational Science Institute, Northwestern University at Chicago—UL1TR001422: Northwestern University Clinical and Translational Science Institute, University of Cincinnati—UL1TR001425: Center for Clinical and Translational Science and Training, The University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston—UL1TR001439: The Institute for Translational Sciences, Medical University of South Carolina—UL1TR001450: South Carolina Clinical & Translational Research Institute, University of Massachusetts Medical School Worcester—UL1TR001453: The UMass Center for Clinical and Translational Science, University of Southern California—UL1TR001855: The Southern California Clinical and Translational Science Institute, Columbia University Irving Medical Center—UL1TR001873: Irving Institute for Clinical and Translational Research, George Washington Children's Research Institute—UL1TR001876: Clinical and Translational Science Institute at Children's National, University of Kentucky—UL1TR001998: UK Center for Clinical and Translational Science, University of Rochester—UL1TR002001: UR Clinical & Translational Science Institute, University of Illinois at Chicago—UL1TR002003: UIC Center for Clinical and Translational Science, Penn State Health Milton S. Hershey Medical Center—UL1TR002014: Penn State Clinical and Translational Science Institute, The University of Michigan at Ann Arbor—UL1TR002240: Michigan Institute for Clinical and Health Research, Vanderbilt University Medical Center—UL1TR002243: Vanderbilt Institute for Clinical and Translational Research, University of Washington—UL1TR002319: Institute of Translational Health Sciences, Washington University in St. Louis—UL1TR002345: Institute of Clinical and Translational Sciences, Oregon Health & Science University—UL1TR002369: Oregon Clinical and Translational Research Institute, University of Wisconsin-Madison—UL1TR002373: UW Institute for Clinical and Translational Research, Rush University Medical Center—UL1TR002389: The Institute for Translational Medicine (ITM), The University of Chicago—UL1TR002389: ITM, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill—UL1TR002489: North Carolina Translational and Clinical Science Institute, University of Minnesota—UL1TR002494: Clinical and Translational Science Institute, Children's Hospital Colorado—UL1TR002535: Colorado Clinical and Translational Sciences Institute, The University of Iowa—UL1TR002537: Institute for Clinical and Translational Science, The University of Utah—UL1TR002538: Uhealth Center for Clinical and Translational Science, Tufts Medical Center—UL1TR002544: Tufts Clinical and Translational Science Institute, Duke University—UL1TR002553: Duke Clinical and Translational Science Institute, Virginia Commonwealth University—UL1TR002649: C. Kenneth and Dianne Wright Center for Clinical and Translational Research, The Ohio State University—UL1TR002733: Center for Clinical and Translational Science, The University of Miami Leonard M. Miller School of Medicine—UL1TR002736: University of Miami Clinical and Translational Science Institute, University of Virginia—UL1TR003015: iTHRIVL Integrated Translational health Research Institute of Virginia, Carilion Clinic—UL1TR003015: iTHRIVL Integrated Translational health Research Institute of Virginia, University of Alabama at Birmingham—UL1TR003096: Center for Clinical and Translational Science, Johns Hopkins University—UL1TR003098: Johns Hopkins Institute for Clinical and Translational Research, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences—UL1TR003107: UAMS Translational Research Institute, Nemours—U54GM104941: Delaware CTR ACCEL Program, University Medical Center New Orleans—U54GM104940: Louisiana Clinical and Translational Science Center, University of Colorado Denver, Anschutz Medical Campus—UL1TR002535: Colorado Clinical and Translational Sciences Institute, Mayo Clinic Rochester—UL1TR002377: Mayo Clinic Center for Clinical and Translational Science, Tulane University—UL1TR003096: Center for Clinical and Translational Science, Loyola University Medical Center—UL1TR002389: The ITM, Advocate Health Care Network—UL1TR002389: ITM, OCHIN—INV-018455: Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation grant to Sage Bionetworks, The Rockefeller University—UL1TR001866: Center for Clinical and Translational Science, The Scripps Research Institute—UL1TR002550: Scripps Research Translational Institute, University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio—UL1TR002645: Institute for Integration of Medicine and Science, The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston—UL1TR003167: Center for Clinical and Translational Sciences, NorthShore University HealthSystem—UL1TR002389: ITM, Yale New Haven Hospital—UL1TR001863: Yale Center for Clinical Investigation, Emory University—UL1TR002378: Georgia Clinical and Translational Science Alliance, Weill Medical College of Cornell University—UL1TR002384: Weill Cornell Medicine Clinical and Translational Science Center, Montefiore Medical Center—UL1TR002556: Institute for Clinical and Translational Research at Einstein and Montefiore, Medical College of Wisconsin—UL1TR001436: Clinical and Translational Science Institute of Southeast Wisconsin, University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center—UL1TR001449: University of New Mexico Clinical and Translational Science Center, George Washington University—UL1TR001876: Clinical and Translational Science Institute at Children's National, Stanford University—UL1TR003142: Spectrum: The Stanford Center for Clinical and Translational Research and Education, Regenstrief Institute—UL1TR002529: Indiana Clinical and Translational Science Institute, Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center—UL1TR001425: Center for Clinical and Translational Science and Training, Boston University Medical Campus—UL1TR001430: Boston University Clinical and Translational Science Institute, The State University of New York at Buffalo—UL1TR001412: Clinical and Translational Science Institute, Aurora Health Care—UL1TR002373: Wisconsin Network For Health Research, Brown University—U54GM115677: Advance Clinical Translational Research (Advance-CTR), Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey—UL1TR003017: New Jersey Alliance for Clinical and Translational Science, Loyola University Chicago—UL1TR002389: The ITM, #N/A—UL1TR001445: Langone Health's Clinical and Translational Science Institute, Children's Hospital of Philadelphia—UL1TR001878: Institute for Translational Medicine and Therapeutics, University of Kansas Medical Center—UL1TR002366: Frontiers: University of Kansas Clinical and Translational Science Institute, Massachusetts General Brigham—UL1TR002541: Harvard Catalyst, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai—UL1TR001433: ConduITS Institute for Translational Sciences, Ochsner Medical Center—U54GM104940: Louisiana Clinical and Translational Science Center, HonorHealth—None (Voluntary), University of California, Irvine—UL1TR001414: The UC Irvine Institute for Clinical and Translational Science, University of California, San Diego—UL1TR001442: Altman Clinical and Translational Research Institute, University of California, Davis—UL1TR001860: UCDavis Health Clinical and Translational Science Center, University of California, San Francisco—UL1TR001872: UCSF Clinical and Translational Science Institute, University of California, Los Angeles—UL1TR001881: UCLA Clinical Translational Science Institute, University of Vermont—U54GM115516: Northern New England Clinical & Translational Research Network, Arkansas Children's Hospital—UL1TR003107: UAMS Translational Research Institute

Data Availability Statement: The N3C Data Enclave (covid.cd2h.org/enclave) houses fully reproducible, transparent, and broadly available limited and de-identified datasets (HIPAA definitions: https://www.hhs.gov/hipaa/for-professionals/privacy/specialtopics/de-identification/index.html). Data are accessible by investigators at institutions that have signed a Data Use Agreement with NIH who have taken human subjects and security training and attest to the N3C User Code of Conduct. Investigators wishing to access the limited dataset must also supply an institutional IRB protocol. All requests for data access are reviewed by the NIH Data Access Committee. A full description of the N3C Enclave governance has been published; information about how to apply for access is available on the NCATS website: https://ncats.nih.gov/n3c/about/applying-for-access. Reviewers and health authorities will be given access permission and guidance to aid reproducibility and outcomes assessment. A Frequently Asked Questions about the data and access has been created at: https://ncats.nih.gov/n3c/about/program-faq The data model is OMOP 5.3.1, specifications are posted at: https://ncats.nih.gov/files/OMOP_CDM_COVID.pdf

This manuscript is available on the medRxIv preprint server as MEDRXIV/2021/258312 at https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.06.03.21258312.

CRediT Authorship Contributions

Jin Ge, MD, MBA (Conceptualization: Lead; Formal analysis: Lead; Investigation: Lead; Writing – original draft: Lead). Mark J. Pletcher, MD, MPH (Data curation: Supporting; Writing – review & editing: Supporting). Jeremy R. Harper, MBI (Data curation: Equal; Data Quality Assurance; Governance; N3C Phenotype Definition: Equal). Christopher G. Chute, DrPH, MD, MPH (Data curation: Equal; Funding acquisition: Equal; Project administration: Equal; Resources: Equal; Writing – review & editing: Supporting; Clinical Data Model Expertise; Data Integration; Data Quality Assurance: Equal). Melissa A. Haendel, PhD (Funding acquisition: Equal; Supervision: Equal; Governance; Project Management; Regulatory Oversight: Equal). Jennifer C. Lai, MD, MBA (Conceptualization: Supporting; Formal analysis: Supporting; Investigation: Supporting; Supervision: Lead; Writing – original draft: Supporting; Writing – review & editing: Supporting).

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest The authors disclose no conflicts.

Funding The authors of this study were supported by 5T32DK060414-18 (National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases to Jin Ge), American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) Advanced/Transplant Hepatology Award (AASLD Foundation, to Jin Ge), P30DK026743 (UCSF Liver Center Grant, to Jin Ge and Jennifer C. Lai), UL1TR001872 (National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, to Mark J. Pletcher), and R01AG059183 (National Institute on Aging, to Jennifer C. Lai). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or any other funding agencies. The funding agencies played no role in the analysis of the data or the preparation of this manuscript.

Author names in bold designate shared co-first authorship

Note: To access the supplementary material accompanying this article, visit the online version of Gastroenterology at www.gastrojournal.org, and at http://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2021.07.010.

Contributor Information

N3C Consortium:

Jeremy R. Harper, Christopher G. Chute, and Melissa A. Haendel

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Table 1.

Standard Observational Medical Outcomes Partnership Concept Identifiers for Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 Testing Per National COVID Cohort Collaborative Shared Logic Sets

| SARS-CoV-2 test type | OMOP concept identifiers |

|---|---|

| Culture | 586516 |

| Nucleic acid amplification | 586517, 586518, 586519, 586520, 586523, 586526, 706154, 706155, 706156, 706157, 706158, 706159, 706160, 706161, 706163, 706165, 706166, 706167, 706168, 706169, 706170, 706171, 706172, 706173, 706174, 706175, 715260, 715261, 715262, 757677, 757678 |

Supplementary Table 2.

Standard Observational Medical Outcomes Partnership Concept Identifiers for Chronic Liver Disease Etiologies, Alcohol Use and its Complications, and Cirrhosis and its Complications

| Etiology of chronic liver disease or complication of cirrhosis | Validated ICD-10-CM codes | OMOP concept identifier |

|---|---|---|

| Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease19,20,26 | K76.0 without an associated alcohol use ICD10-CM or OMOP code,a K75.81 | 4059290 without an associated alcohol use concept ID,a 40484532 |

| Chronic hepatitis C19,20 | B17.1, B18.2, B19.2 | 192242, 198964, 197494 |

| Alcohol-associated liver disease19,20,24, 25, 26,51 | K70.0, K70.1, K70.2, K70.3, K70.4, K70.9, and K76.0 with an associated alcohol use ICD 10-CM or OMOP Codea | 4340383, 4340385, 196463, 4340386, 201612, and 4059290 with an associated alcohol use concept IDa |

| Chronic hepatitis B19,20 | B16.X, B17,0, B18.0, B18.1, B19.1 | 197795, 197493, 192240, 439674, 4281232 |

| Cholestatic liver disease21 | K74.3, K74.4, K74.5, K83.01 | 4135822, 4046123, 192675, 4058821 |

| Autoimmune hepatitis22 | K73.2, K75.4 | 4026125, 200762 |

| Cirrhosis | K70.30, K74.69, K74.60, E83.11, K71.7, K72.1, K74.3, K74.4, K74.5 | 196463, 4064161, 4163735, 4026136, 4340390, 4135822, 4046123, 192675 |

| Varices, not bleeding | I85.00, I86.4, I85.1 | 22340, 24966, 4237824, 4111998 |

| Varices, bleeding | I85.01, I86.41, I85.11 | 28779, 4087310, 4112183, |

| Ascites | K70.31, K70.11, K71.51, R18.8 | 46269816, 46269835, 46273476, 200528 |

| Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis | K65.2 | 199863 |

| Hepatic encephalopathy | K72.91, G93.40, K72.11, K70.41, K71.11, K72.01, B19.0, B19.11, B19.21 | 4245975, 377604, 372887, 46269836, 46269818, 377604, 196029, 200031, 439672 |

| Hepatorenal syndrome | K76.7 | 196455 |

| Hepatopulmonary syndrome | K76.81 | 4159144 |

Supplementary Table 3.

Modified Charlson Comorbidity Index Excluding Weights for Liver-Related Comorbidities

| Original Charlson Comorbidity Index29,30 |

Modified Charlson Index |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Assigned weights | Conditions | Assigned weights | Conditions |

| 1 | Myocardial infarct | 1 | Myocardial infarct |

| 1 | Congestive heart failure | 1 | Congestive heart failure |

| 1 | Peripheral vascular disease | 1 | Peripheral vascular disease |

| 1 | Stroke or cerebrovascular disease | 1 | Stroke or cerebrovascular disease |

| 1 | Dementia | 1 | Dementia |

| 1 | Chronic pulmonary disease | 1 | Chronic pulmonary disease |

| 1 | Connective tissue disease | 1 | Connective tissue disease |

| 1 | Peptic ulcer disease | 1 | Peptic ulcer disease |

| 1 | Mild liver disease | 0 | Mild liver disease |

| 1 | Diabetes | 1 | Diabetes |

| 2 | Hemiplegia or paralysis | 2 | Hemiplegia or paralysis |

| 2 | Chronic renal disease | 2 | Chronic renal disease |

| 2 | Complicated diabetes (with end organ damage) | 2 | Complicated diabetes (with end organ damage) |

| 2 | Malignancy/leukemia/lymphoma | 2 | Malignancy/leukemia/lymphoma |

| 3 | Severe liver disease | 0 | Severe liver disease |

| 6 | Metastatic malignancy | 6 | Metastatic malignancy |

| 6 | HIV/AIDS | 6 | HIV/AIDS |

Supplementary Table 4.

Standard Observational Medical Outcomes Partnership Concept Identifiers for International Normalized Ratio

| OMOP concept identifiers | Concept names |

|---|---|

| 3039326 | INR in platelet poor plasma by coagulation assay, post heparin neutralization |

| 3022217 | INR in platelet poor plasma by coagulation assay |

| 3051593 | INR in capillary blood by coagulation assay |

| 3032080 | INR in blood by coagulation assay |

| 3042605 | INR in platelet poor plasma or blood by coagulation assay |

| 4261078 | Calculation of international normalized ratio |

INR, international normalized ratio.

Supplementary Table 5.

Sensitivity Analyses of Cox Regressions Involving Patients With Cirrhosis

| Model Evaluated | n | aHR | 95% CI | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SARS-CoV-2 infection among patients with cirrhosis (cirrhosis/positive vs cirrhosis/negative) | ||||

| MV | 62,403 | 2.38 | 2.18–2.59 | <.01 |

| MV + MELD-Na | 10,785 | 2.05 | 1.78–2.37 | <.01 |

| MV + serum albumin | 28,348 | 1.66 | 1.50–1.85 | <.01 |

| MV + MELD-Na + serum albumin | 9853 | 1.76 | 1.51–2.04 | <.01 |

| Age in factors associated with death among cirrhosis-positive patients | ||||

| MV | 8939 | 1.04 | 1.03–1.04 | <.01 |

| MV + MELD-Na | 1407 | 1.05 | 1.03–1.06 | <.01 |

| MV + serum albumin | 4098 | 1.02 | 1.02–1.03 | <.01 |

| MV + MELD–Na + serum albumin | 1311 | 1.04 | 1.03-1.05 | <.01 |

| Unknown/other race (reference White) in factors associated with death among cirrhosis-positive patients | ||||

| MV | 8939 | 1.65 | 1.27–2.15 | <.01 |

| MV + MELD-Na | 1407 | 1.18 | 0.77–1.82 | .44 |

| MV + serum albumin | 4098 | 1.61 | 1.17–2.20 | <.01 |

| MV + MELD-Na + serum albumin | 1311 | 1.31 | 0.85–2.04 | .22 |

| Alcohol-associated liver disease (reference NAFLD) in factors associated with death among cirrhosis-positive patients | ||||

| MV | 8939 | 1.22 | 1.01–1.46 | .03 |

| MV + MELD-Na | 1407 | 0.80 | 0.59–1.10 | .17 |

| MV + serum albumin | 4098 | 0.87 | 0.70–1.08 | .21 |

| MV + MELD-Na + serum albumin | 1311 | 0.77 | 0.56–1.06 | .11 |