Abstract

There is a limited understanding of factors such as travel time, availability of emergency obstetric care (EmOC), and satisfaction/perceived quality of care on the utilization of maternal health services in fragile and conflict-affect settings. In Afghanistan, the risk of maternal death is among the highest in the world. We assessed the relationship between these three key factors on maternal healthcare utilization in northern Afghanistan from 2010-2015. We examined three outcomes of maternal healthcare utilization: at least one skilled antenatal care (ANC) visit, in-facility delivery, and bypassing the nearest public facility for childbirth. We used three-level multilevel mixed effects logistic regression models to assess the relationships between women’s and facilities’ characteristics and outcomes. Nearest public facility score for satisfaction/perceived quality was associated with having at least one skilled ANC visit (AOR: 2.02, 95% CI: 1.21, 3.36). Women whose nearest public facility provided EmOC had a higher odds of in-facility childbirth compared to women whose nearest public facility did not provide EmOC (AOR: 1.24, 95% CI: 1.04,1.48). Nearest public hospital travel time (AOR: 0.95, 95% CI: 0.93, 0.98) and nearest public facility satisfaction/perceived quality score (AOR: 0.34, 95% CI: 0.14, 0.82) were associated with lower odds of women bypassing their nearest public facility for childbirth. Afghanistan has made progress in expanding access to maternal healthcare services during ongoing conflict. Addressing key barriers is essential to ensure that women have access to life-saving services.

Keywords: maternal health, Afghanistan, access to healthcare, antenatal care use, in-facility childbirth

Introduction

From 1990 to 2015, the global maternal mortality ratio (MMR) declined by almost half (44%) – from 385 deaths to 216 deaths/100,000 live births (UNICEF, 2017). However, many women continue to die from preventable and treatable complications related to childbirth. This is particularly true in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC) where, in 2015, the MMR (436 deaths/100,000 live births) was twice that of wealthier countries (UNICEF, 2017). Recognizing this as a priority, the UN Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 3.1 is to decrease the global MMR to fewer than 70/100,000 live births by 2030. Accessing maternal healthcare services, including antenatal care (ANC), skilled birth attendance (SBA), and delivery at a facility with emergency obstetric care (EmOC) available in case complications occur, is essential to improving both maternal and neonatal outcomes (Kassebaum et al., 2016; Mumtaz et al., 2019).

Barriers to accessing maternal healthcare services are amplified in fragile and conflict-affected settings. Thaddeus and Maine (1994) documented three critical delays – delayed decision to seek care, delayed arrival at a health facility, and delayed provision of adequate care. Distance, transportation challenges, cost, and satisfaction/perceived quality contribute to the first and second delays, while the availability of services (supplies, equipment, trained personnel) and adequate referral systems mainly contribute to the third delay (Thaddeus & Maine, 1994). A systematic literature review on the determinants of maternal and neonatal health care use in fragile and conflict-affected settings identified similar factors, distinguishing demand-side (e.g., access to transportation, female education, autonomy, health awareness, and cost of health services) from supply-side (e.g., availability and quality of health services) determinants (Gopalan et al., 2017).

In Afghanistan, the risk of maternal death is among the highest in the world with an MMR of 638 deaths/100,000 live births (WHO et al., 2019). While national MMR estimates are debated, regardless of the estimate or data source used, the number of maternal deaths in the country is unacceptably high (Alba et al., 2020). Significant progress has been made to rebuild the country’s health system, despite over 20 years of continuous conflict (Akseer et al., 2016). Between 2003 and 2015, coverage of maternal healthcare interventions substantially increased, including ANC (16% to 59%), SBA (14% to 51%), and in-facility births (13% to 48%) (Akseer et al., 2016; Ministry of Public Health (MoPH) [Afghanistan] & Central Statistics Organization (CSO) [Afghanistan], 2017). However, coverage of key interventions fall short of levels achieved by countries with MMR of 70: 91% coverage of one ANC visit, 87% skilled birth attendance, and 81% in-facility births necessary to achieve SDG 3.1 (Kassebaum et al., 2016).

In Afghanistan, socioeconomic and demographic factors, such as wealth quintile, parity, and education, are strong predictors of SBA use (Mayhew et al., 2008; Tappis et al., 2016). Additionally, sociocultural barriers, distance to a health facility and transportation access are common reasons for home delivery (Higgins-Steele et al., 2018; Hirose et al., 2015; Newbrander et al., 2014; Tappis et al., 2016). ANC use reduced the delay to seek care at the time of an obstetric emergency (Hirose et al., 2011). Surprisingly, nearly 60% of women who delivered with a SBA bypassed their nearest public facility to give birth at a more distant provider (Tappis et al., 2016). Bypassing the nearest public facility for childbirth increases time to access necessary life-saving EmOC. Among the factors that may affect the likelihood of women bypassing the closest facility are travel time, satisfaction/perceived quality, and facility characteristics (Kruk et al., 2009).

While there is speculation as to why women bypass their nearest facility to receive care, this question has not been examined systematically in Afghanistan. And to our knowledge, no prior studies in Afghanistan have assessed the role of these factors in explaining maternal healthcare service use, specifically for skilled ANC, in-facility births, and bypassing behaviour. This study is the first on Afghanistan to illustrate the spectrum of maternal healthcare services use targeting these three outcomes. We discuss the key findings associated with these outcomes and how these findings may guide future programs and policies for improving maternal healthcare utilization. Further, previous studies examining the determinants of maternal healthcare use in Afghanistan have been qualitative and cross-sectional, not accounting for time trends. Using data from 2010 to 2015, this study assesses the relationship between travel time, availability of EmOC, and satisfaction/perceived quality on maternal healthcare utilization in northern Afghanistan.

Materials and methods

Data Sources

Multiple secondary data sources were used for the analyses. We used a household survey conducted in nine provinces of the country, spatial information on health facilities and villages, Health Management Information System (HMIS) data on public health facilities, data on security incidents, and public health facility assessment data from the Balanced Scorecard. We describe each of these sources in detail.

Household survey data

The household survey was conducted as part of an impact evaluation of a results-based financing (RBF) intervention in nine northern provinces (Figure 1) (Engineer et al., 2016; MoPH [Afghanistan], Royal Tropical Institute of Amsterdam (KIT), et al., 2015). The surveys are repeated cross-sections. Two questionnaires were used for the household survey: the household questionnaire and the female and child health questionnaire.

Figure 1.

Provinces included in household survey for Results-based Financing pilot intervention

The household survey used a multi-stage probability sample of the nine selected provinces. The nine provinces were purposively selected based on representation of provinces supported by different donors and feasibility of implementing the pilot project. The first stage randomly selected 74 health facilities stratified and matched by facility type and number of outpatient visits in the previous year; one facility was randomly selected for the intervention and the other for usual care. The second stage consisted of a random sample of 288 villages or clusters in the catchment area of the selected health facilities (2 clusters per health facility). Using the household listing conducted prior to the survey, the third stage involved simple random sampling of households in the selected villages. The same villages and health facilities were visited during each year of the survey. However, households may or may not be the same as they were not linked across the datasets. On average, interviews were conducted in 24 households per village, resulting in total household sample sizes of 6,878 in 2010, 6,848 in 2013, and 6,584 in 2015. There was less than a 1% nonresponse rate by households across all three years.

The household questionnaire collected information from the head of the household on all household members, including name, sex, education, socioeconomic status, and utilization of health services. The female and child health questionnaire collected information from ever-married women age 15 to 49 or women over 18 years who are primary caretakers of children under five years of age; questions included age, literacy and media exposure; pregnancy-based reproductive history; knowledge and use of family planning methods; access, utilization, and quality of services for antenatal care, delivery, postnatal care, and child health services, including immunization; and, perception and quality of services and trust in healthcare providers.

Spatial data

Spatial data were obtained from several publicly available sources and the MoPH. Data on settlements, provincial boundaries, road network, water bodies, landcover, and health facilities were obtained from 2012-2013 Afghanistan Information Management Services (AIMS) through the Humanitarian Data Exchange (OCHA, 2019). Villages were matched with village or settlement GPS coordinates by name. A total of 251 village clusters were matched, 29 village locations were estimated by field staff, and 8 villages (2.8%) had missing GPS coordinates or estimated locations. The road network included main, secondary, and tertiary roads. Updated health facility coordinates (from the 2012 data) were provided by the MoPH (data from 2015). Digital elevation data were obtained from the US Geological Survey at a spatial resolution of 90m2 (USAID & USGS, 2019).

HMIS data

HMIS data were provided by the MoPH to identify all public primary care clinics (Sub Health Centres, Basic Health Centres, and Comprehensive Health Centres) and hospitals, their activity level in the years 2010, 2013, and 2015, and the availability of EmOC services (e.g., full provision or partial provision) as reported by the MoPH HMIS. The public health system was redesigned to rapidly scale-up primary care services to the population through the Basic Package of Health Services (BPHS) with referrals to the secondary hospital level providing the Essential Package of Hospital Services (EPHS).

The HMIS designates public facilities as providing full EmOC services if they reported performing EmOC procedures that BPHS and EPHS guidelines indicate should be available at the primary care or hospital level for the entire year (MoPH, 2005; MOPH Afghanistan, 2010). All public clinics are expected to provide basic EmOC (BEmOC), defined by six “signal functions” of obstetric care: administration of parenteral antibiotics for puerperal sepsis, administration of uterotonic drugs for postpartum hemorrhage, parenteral anticonvulsants for pre-eclampsia and eclampsia, manual removal of the placenta, removal of retained products of conception; assisted vaginal delivery (with forceps or vacuum). All hospitals are expected to provide Comprehensive EmOC (CEmOC), which includes the six BEmOC signal functions as well as cesarean surgery and blood transfusion (WHO, 2009). However, in 2010, a national assessment found only 68% of surveyed hospitals performed all BEmOC signal functions and 56% of facilities performed all CEmOC signal functions (Y.-M. Kim et al., 2012), and there was little change in EmOC availability between 2010 and 2016 (Ansari et al., 2020). HMIS reports indicate only 33% of all public facilities provided a full year of EmOC services in 2010, 57% in 2013, and 71% in 2015 (C. Kim et al., 2020).

The HMIS dataset had a total of 547 unique facilities over the three years in the nine study provinces with 486 (89%) active facilities with matching GPS coordinates in 2010, 515 (94%) in 2013, and 529 (97%) in 2015. HMIS data were merged with health facility coordinates in Stata 14 (StataCorp, 2015) and exported for use in ArcGIS 10.1 (ESRI, 2011).

Balanced scorecard and other data

We extracted the provincial health system performance indicators of the nine provinces from the Balanced Scorecard for BPHS facilities for each study year (MoPH [Afghanistan], Silk Route Training and Research Organization (SRTRO), et al., 2015; Peters et al., 2007). The Balanced Scorecard data are from the National Health Service Performance Assessment, which is an annual assessment of service provision from a random sample of 25 facilities offering the BPHS in each province. The Balanced Scorecard comprises of 23 indicators across six domains and presents an overall composite score for each province. Data on insecurity incidents by province were obtained from the International NGO Safety Organization (INSO, 2011).

Data Analysis

Household survey data from the nine provinces were used to match travel time data from villages to their nearest public primary care clinic, public hospital, or public facility (clinic or hospital) providing EmOC.

Modelling travel time by transportation mode in GIS

A detailed description of the spatial modelling techniques used to generate travel times from a woman’s village to her nearest public clinic, public hospital, and public facility providing EmOC is described elsewhere (C. Kim et al., 2020). Briefly, a “merged land cover” was generated using a combination of land cover (consisting of 21 land types and sub-types), elevation, road, rivers, and water bodies layers in AccessMod (version 5.0.7). This merged land cover was used to create a raster surface of travel time between facilities and villages and exported with grid cell sizes of 100m2; all subsequent raster layers were aligned with this layer (position and cell resolution). Travel impedance was modelled from the central location of the village to the nearest public facility by a given transport mode. We used ArcGIS to calculate the quickest routes between villages and their nearest public facility or facility providing EmOC services based on predefined speed limits and ease of travel across the six specified land cover types.

Travel scenarios were developed to depict the potential types of transport used by pregnant women to access health facilities: foot only, foot and donkey, foot and motor vehicle, and a combination of the modes for the most efficient travel time. Various sources were used to estimate travel speeds for each transport mode (C. Kim et al., 2020). We assigned the travel speeds to each land cover type for each travel mode to create travel time surfaces (by hour) to every health facility point from the villages. Separate raster layers were then derived for each mode of transport (motor vehicle, donkey, and foot) at 100m2 grid cells and each pixel was assigned an impedance value.

Relationship between travel time and quality of care factors in the utilization of maternal healthcare services

Calculating travel times from GIS data:

Travel times were calculated from each village to every active public facility for each year. Travel time was assigned to women based on their village of residence and reported mode of transport used to seek healthcare. We developed maps of the nine provinces for each year by transport mode to illustrate the change in access to public facilities for women in the sampled villages by travel time (in hours) across the three study years.

Measures:

We examined three outcomes of maternal healthcare utilization: 1) having at least one ANC visit with a skilled provider (yes/no); 2) childbirth at a health facility (delivery in-facility compared to home); and 3) whether women bypassed their nearest public facility for childbirth (yes/no). Variables in the models were selected based on the literature of determinants of delivery service use and the Three Delays model of accessing maternal healthcare (Gabrysch & Campbell, 2009; Gopalan et al., 2017; Thaddeus & Maine, 1994). Supplement Table 1 provides detailed descriptions of all variables in the model, including their level of missingness (missingness was addressed in the statistical analysis). The main independent variables were travel time to, and quality of care of, the nearest public facility. Three travel times were included in the models (in hours) to the nearest public hospital, public clinic (Sub Health Centre, Basic Health Centre, or Comprehensive Health Centre), and public facility providing EmOC. Measures of the availability and quality of care of the nearest public facility included provision of EmOC services (yes/no), facility satisfaction/perceived quality of care score, and availability of at least one female health worker (yes/no).

Nearest public facility satisfaction/perceived quality of care score was constructed from a set of 17 questions on a Likert scale from 1 (lowest) to 4 (highest). These questions were only asked to women who utilized care at these facilities in the previous two weeks to account for recall bias. A score was assigned to each public facility. Household wealth status was measured by wealth quintile based on index scores constructed using principal component analysis of household assets, income sources, and housing characteristics, extracted from the household survey data (MoPH [Afghanistan], KIT, et al., 2015).

Covariates in the model included individual- and household-, facility-, and province-level characteristics. Covariates at the individual and household level included woman’s age (divided into seven five-year categories), woman’s education level (no education, primary, secondary or higher), gravidity (no previous pregnancies or 1 or more previous pregnancies), ANC adequacy index (no ANC, inadequate, and adequate), and access to a motor vehicle (yes/no).

The ANC adequacy index was based on four dimensions of continuity and adequacy of ANC, including skill level of provider (care provided by physician, nurse, or midwife), timeliness (care initiated during the first four months of pregnancy), sufficiency (at least four ANC visits during the pregnancy), and appropriateness (a summary indicator on nine services received: weight check, blood pressure check, urine exam, blood test, nutrition counselling, counselling on signs of pregnancy complications, counselling on where to go when complications occur, iron and folic acid supplementation, and tetanus toxoid 2 vaccine). We used a threshold of six services received, relaxing the 80% threshold used in similar studies for “good” or “adequate” ANC that used medical record data (Majrooh et al., 2014; Yeoh et al., 2015). ANC was considered adequate if a woman had at least four skilled ANC visits in the first four months of pregnancy and received at least six of the nine services. ANC was considered inadequate if a woman had at least one skilled ANC visit after the first four months of pregnancy or fewer than six services received. The ANC adequacy index was only included in the models on in-facility births and bypassing behaviour. We modified the Adequacy of Prenatal Care Utilization Index for this ANC index to account for timeliness, content, and process of care based on WHO recommendations as the number of visits alone do not correlate with content and process of care received (Hodgins & Agostino, 2014; Milton Kotelchuck, 1994). Studies in LMICs commonly use the receipt of four or more ANC visits rather than a composite index, due to various reasons such as limited data availability or inability to capture all processes of care (Heredia-Pi et al., 2016). Use of an ANC index is limited in the UMIC context, and the need to standardize and better measure effective ANC coverage has been recognized (Hodgins & Agostino, 2014; Morón-Duarte et al., 2018).

We also controlled for whether a woman lived in the catchment area of a public facility that received the RBF intervention intended to improve facility performance. Province characteristics included indicator variables for province, number of security incidents by province, provincial health performance scores from the Balanced Scorecard, and year (2010, 2013, 2015).

Statistical analysis:

We accounted for the complex survey design and weights at each level and nested structure in the analysis. Additionally, due to the three-stage sample structure, women living in the same villages and villages within the catchment area of the same public facility were more likely to be similar to each other than women in other villages and catchment areas. Therefore, three-level multilevel mixed effects logistic regression models were used to assess the relationships between women’s and facilities’ characteristics and outcomes. To address missing data for travel time by transport modes and satisfaction/perceived quality of care scores, we used multiple imputation (Stata command for multiple imputation chained equations [MICE]) and generated 45 imputation samples (UCLA: Statistical Consulting Group, n.d.). Weighted descriptive statistics and bivariate analyses were estimated accounting for the survey design. Multicollinearity was assessed by obtaining the variance inflation factors (VIF), and security incidents and provincial health performance score were both excluded from the final models due to their high levels of correlation with the province variable. Results from the multilevel logistic analyses are presented as adjusted odds ratios (AOR) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) and evaluated at a p-value≤0.05. All statistical analyses were conducted in Stata 14.

Ethical Considerations

Permission to use all datasets for this secondary data analysis was granted by the MoPH in Kabul, Afghanistan. We received an exemption from the Institutional Review Board at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill to conduct this study (#16-3202).

Results

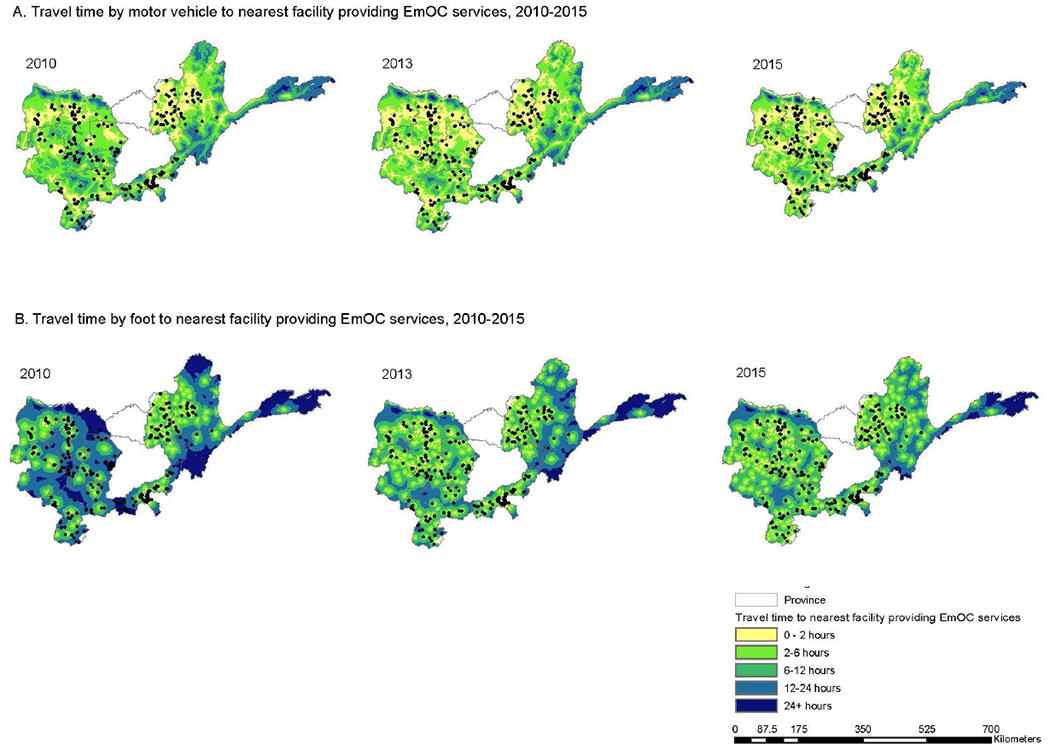

Spatial Access and Travel Time

In 2010, the majority of the nine provinces, including many villages included in this study sample, remained more than 12 hours away by foot from a facility that provided EmOC services (Figure 2). By 2015, most of these villages were within a 12-hour walking zone. While both panels in the figure show improvements in access over time, the least access remains in Badakhshan province near the Wakhan corridor in the northeast of the country.

Figure 2.

Spatial access and travel time to public facilities providing EmOC services for villages in the nine provinces in study sample, 2010-2015

Characteristics of Study Sample

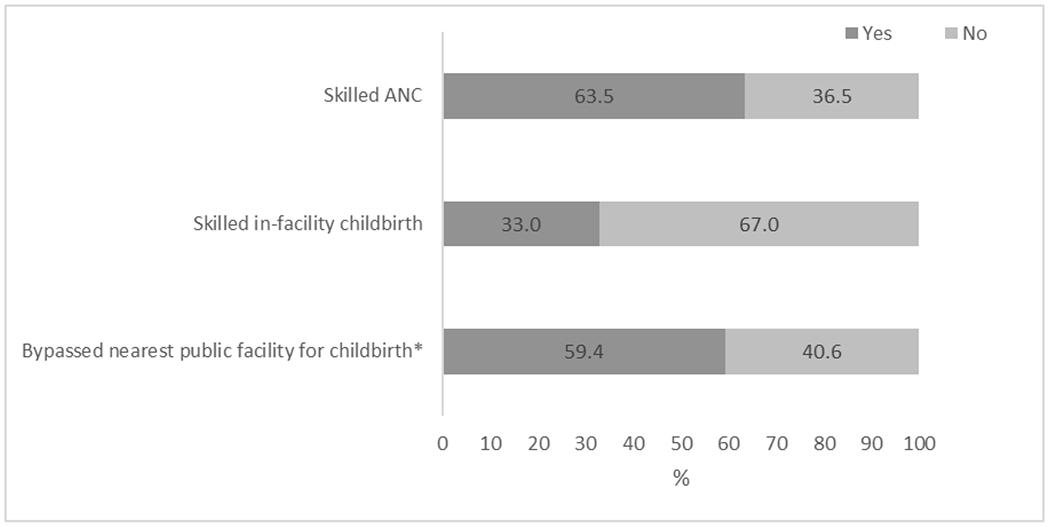

A total of 9,712 women were included in the analytical sample for use of skilled ANC, 9,705 women for in-facility childbirth, and 3,038 women for whether they bypassed their nearest facility for childbirth (Table 1). Bypassing behaviour was conditional on having an in-facility birth. Descriptive statistics for all characteristics can be found in Supplement Tables 2–4. Sixty-three percent of women had at least one skilled ANC visit, 33.0% delivered at a facility, and among those who gave birth in a facility, 59.4% bypassed their nearest facility for childbirth (Figure 3). Nearly half (46.0%) of women who had skilled ANC were from the upper two wealth quintiles, though only 6.8% had access to a motor vehicle. Women who had skilled ANC had an average travel time of 1.8 hours to the nearest public clinic, compared to 2.0 hours for women who did not use skilled ANC. Among women who had a birth at a facility compared to those who delivered at home, the mean travel time to the nearest public facility providing EmOC (2.6 vs 3.8 hours) and public hospital (6.4 vs 7.7 hours) was at least one hour less. Almost 75% of the women lived nearest to a public facility providing EmOC, and 62% lived nearest to a public facility with at least one female health worker. Among women who delivered at a facility, the mean satisfaction/perceived quality of care score for their nearest facility was 57.6% compared with 55.4% for women who delivered at home. Travel times to the nearest public facility providing EmOC, public hospital, and public clinic among women who delivered in a facility compared to women who delivered at home were 2.6 hours vs. 3.8 hours, 6.4 hours vs. 7.7, and 1.6 hours vs. 2.0 hours, respectively. Among women who bypassed their nearest public facility for childbirth, 38.8% were from the highest wealth quintile and had a mean travel time to the nearest public facility providing EmOC of 2.2 hours compared with 3.2 hours for women who did not bypass their nearest public facility, and 4.9 hours to the nearest public hospital compared with 8.7 hours for women who did not bypass their nearest public hospital.

Table 1.

Characteristics of women and their nearest public facility included in study sample by maternal health utilization outcomes, weighted by women’s probability of selection*+

| No skilled ANC | At least one skilled ANC visit | p-value | No in-facility delivery | In-facility delivery | p-value | Childbirth at nearest public facility a | Bypassed nearest public facility a | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

| (n=3741) n (%) | (n=5971) n (%) | (n=6606) n (%) | (n=3099) n (%) | (n=1136) n (%) | (n=1902) n (%) | ||||

|

| |||||||||

| Individual/household characteristics | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Wealth status | |||||||||

| First quintile | 835 (21.4) | 841 (14.1) | ≤0.001 | 1328 (19.0) | 348 (12.2) | ≤0.001 | 164 (14.6) | 175 (10.6) | ≤0.001 |

| Second quintile | 755 (19.2) | 1080 (18.7) | 1360 (20.6) | 474 (15.4) | 245 (21.0) | 217 (11.4) | |||

| Third quintile | 766 (20.9) | 1183 (20.2) | 1416 (22.1) | 532 (17.1) | 230 (19.5) | 292 (15.5) | |||

| Fourth quintile | 757 (21.4) | 1254 (21.1) | 1318 (20.4) | 689 (22.8) | 237 (21.3) | 439 (23.8) | |||

| Fifth quintile | 628 (17.1) | 1613 (25.9) | 1184 (17.9) | 1056 (32.4) | 260 (23.6) | 779 (38.8) | |||

| Access to a motor vehicle | |||||||||

| No | 3256 (94.2) | 5376 (93.2) | 0.094 | 5880 (94.8) | 2745 (91.3) | ≤0.001 | 1021 (93.0) | 1669 (90.0) | 0.048 |

| Yes | 189 (5.7) | 405 (6.8) | 314 (5.2) | 279 (8.7) | 75 (7.0) | 199 (10.0) | |||

| Travel time to nearest public facility providing EmOC [n (mean hours)] | 4453 (3.8) | 2296 (2.6) | ≤0.001 | 834 (3.2) | 1420 (2.2) | ≤0.001 | |||

| Travel time to nearest public hospital [n (mean hours)] | 4453 (7.7) | 2296 (6.4) | ≤0.001 | 834 (8.7) | 1420 (4.9) | ≤0.001 | |||

| Travel time to nearest public clinic [n (mean hours)] | 2277 (2.0) | 4481 (1.8) | 0.015 | 4453 (2.0) | 2296 (1.6) | ≤0.001 | 834 (2.0) | 1420 (1.4) | ≤0.001 |

|

| |||||||||

| Nearest facility characteristics | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Facility type | |||||||||

| Sub Health Centre | 1474 (42.8) | 2576 (46.2) | 0.116 | 2654 (43.9) | 1391 (47.1) | 0.042 | 529 (45.3) | 831 (48.0) | 0.243 |

| Basic Health Centre | 1419 (31.9) | 1927 (25.7) | 2424 (29.6) | 919 (24.7) | 280 (21.4) | 621 (26.8) | |||

| Comprehensive Health Centre | 616 (19.1) | 1058 (20.8) | 1160 (20.6) | 515 (19.3) | 221 (23.0) | 282 (17.0) | |||

| Hospital | 232 (6.2) | 410 (7.3) | 368 (5.9) | 274 (8.9) | 106 (10.3) | 168 (8.2) | |||

| EmOC provided | |||||||||

| No | 1140 (24.9) | 1805 (27.4) | 0.198 | 2160 (27.4) | 784 (24.6) | 0.163 | 298 (25.8) | 471 (24.0) | 0.574 |

| Yes | 2601 (75.1) | 4166 (72.6) | 4446 (72.6) | 2315 (75.4) | 838 (74.2) | 1431 (76.0) | |||

| At least 1 female health worker | |||||||||

| No | 1672 (39.2) | 2627 (38.2) | 0.63 | 3094 (41.2) | 1202 (33.1) | ≤0.001 | 364 (26.4) | 808 (37.5) | ≤0.001 |

| Yes | 2069 (60.8) | 3344 (61.8) | 3512 (58.8) | 1897 (66.9) | 772 (73.6) | 1094 (62.5) | |||

| Satisfaction/perceived quality score [n (mean score)] | 994 (53.1) | 4523 (56.9) | ≤0.001 | 3437 (55.4) | 2074 (57.6) | 0.003 | 875 (57.5) | 1154 (57.7) | 0.874 |

Abbreviations: EmOC: Emergency Obstetric Care

Complex survey design, weights, and nested structure accounted for in descriptive analysis. Sub-total sample sizes may not add up to the total due to missingness.

Complete tables with descriptive statistics for each outcome provided in Supplement.

Bypassed nearest public facility for childbirth conditional on skilled delivery at a facility

Figure 3.

Maternal health utilization outcomes by total women in study sample with a live birth in the previous two years of study (n=9,720)

*Bypassed nearest public facility for childbirth conditional on skilled delivery at a facility

Relationship Between Travel Time, Availability, and Quality of Care on Utilization of Maternal Health Services

Controlling for individual, facility and community characteristics (Table 2), satisfaction/perceived quality of the nearest facility was associated with a higher odds of having at least one skilled ANC visit (AOR: 2.02, 95% CI: 1.21, 3.36). Higher odds of women’s use of skilled ANC were also associated with education level and wealth status. Travel times and other quality of care factors were not associated with the use of skilled ANC. Unadjusted bivariate results are presented in Supplement Table 5.

Table 2.

Multilevel logistic regression analyses of travel time to public facilities and quality of care predicting the utilization of maternal healthcare services for the most recent birth within the last two years

| Skilled ANC | In-facility delivery | Bypassed nearest public facility | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Adjusted OR (95% CI) | P-value | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | P-value | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | P-value | |

|

| ||||||

| Fixed effects | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Individual/household characteristics | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Woman’s age category (ref: 15-19 years) | ||||||

| 20-24 years | 0.91 (0.71, 1.15) | 0.412 | 0.85 (0.69, 1.06) | 0.141 | 0.91 (0.58, 1.41) | 0.665 |

| 25-29 years | 0.89 (0.72, 1.12) | 0.332 | 0.58*** (0.47, 0.73) | ≤0.001 | 0.83 (0.53, 1.29) | 0.407 |

| 30-34 years | 0.89 (0.72, 1.12) | 0.340 | 0.54*** (0.42, 0.68) | ≤0.001 | 0.85 (0.54, 1.33) | 0.476 |

| 35-39 years | 0.80 (0.63, 1.01) | 0.065 | 0.64*** (0.50, 0.83) | ≤0.001 | 0.82 (0.52, 1.29) | 0.389 |

| 40-44 years | 0.66** (0.50, 0.87) | 0.004 | 0.61*** (0.45, 0.80) | ≤0.001 | 1.16 (0.66, 2.05) | 0.611 |

| 45-49 years | 0.71* (0.50,0.99) | 0.048 | 0.66* (0.45, 0.97) | 0.034 | 1.32 (0.57, 3.05) | 0.517 |

| Woman’s education level (ref: No education) | ||||||

| Primary education | 1.47*** (1.19, 1.81) | ≤0.001 | 1.53*** (1.18, 1.97) | ≤0.001 | 1.05 (0.69, 1.60) | 0.826 |

| Secondary education or more | 2.11*** (1.57, 2.82) | ≤0.001 | 2.22*** (1.68, 2.93) | ≤0.001 | 1.42 (0.83, 2.43) | 0.195 |

| Gravidity (ref: No previous pregnancies) | ||||||

| 1 or more previous pregnancies | 0.91 (0.64, 1.28) | 0.597 | 0.96 (0.70, 1.31) | 0.800 | 0.90 (0.48, 1.67) | 0.732 |

| Wealth status (ref: First quintile) | ||||||

| Second quintile | 1.18* (1.00, 1.40) | 0.047 | 1.10 (0.91, 1.32) | 0.322 | 0.51*** (0.34, 0.73) | ≤0.001 |

| Third quintile | 1.37*** (1.16, 1.61) | ≤0.001 | 1.08 (0.88, 1.32) | 0.459 | 0.73 (0.50, 1.09) | 0.128 |

| Fourth quintile | 1.42*** (1.18, 1.72) | ≤0.001 | 1.31* (1.04, 1.64) | 0.020 | 0.93 (0.61, 1.42) | 0.739 |

| Fifth quintile | 1.73*** (1.40, 2.16) | ≤0.001 | 1.40** (1.10, 1.78) | 0.006 | 0.84 (0.53, 1.35) | 0.475 |

| ANC adequacy index (ref: No ANC) | ||||||

| Inadequate | 4.08*** (3.48, 4.80) | ≤0.001 | 1.07 (0.78, 1.47) | 0.662 | ||

| Adequate | 6.58*** (4.97, 8.71) | ≤0.001 | 0.99 (0.61, 1.63) | 0.975 | ||

| Access to motor vehicle (ref: No) | ||||||

| Yes | 0.99 (0.80, 1.22] | 0.934 | 1.26* (1.01, 1.57) | 0.044 | 1.24 (0.83, 1.84) | 0.299 |

| Travel time to nearest public facility providing EmOC | 1.00 (0.98, 1.02) | 0.674 | 1.02 (0.99, 1.06) | 0.221 | ||

| Travel time to nearest public hospital | 1.00 (0.99, 1.01) | 0.721 | 0.95*** (0.93, 0.98) | ≤0.001 | ||

| Travel time to nearest public clinic | 0.97 (0.93, 1.02) | 0.217 | 0.94* (0.89, 0.99) | 0.042 | 0.97 (0.87, 1.07) | 0.499 |

| Facility characteristics | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Nearest facility type (ref: Sub Health Centre) | ||||||

| Basic Health Centre | 1.15 (0.92, 1.44) | 0.205 | 1.16 (0.91, 1.47) | 0.225 | 0.68 (0.44, 1.50) | 0.081 |

| Comprehensive Health Centre | 1.01 (0.76, 1.33) | 0.950 | 0.91 (0.69, 1.20) | 0.501 | 0.47** (0.28, 0.77) | 0.003 |

| Hospital | 0.98 (0.67, 1.43) | 0.908 | 1.45 (0.88, 2.39) | 0.139 | 0.44 (0.19, 1.01) | 0.053 |

| Nearest public facility provides EmOC (ref: No) | ||||||

| Yes | 1.17 (0.91, 1.51) | 0.211 | 1.24* (1.04, 1.48) | 0.020 | 0.84 (0.56, 1.26) | 0.400 |

| At least 1 female health worker at nearest public facility (ref: No) | ||||||

| Yes | 0.85 (0.69, 1.06) | 0.158 | 1.11 (0.93, 1.31) | 0.247 | 0.82 (0.55, 1.21) | 0.316 |

| Satisfaction/perceived quality score of nearest public facility | 2.02** (1.21, 3.36) | 0.008 | 1.12 (0.75, 1.67) | 0.587 | 0.34** (0.14, 0.82) | 0.017 |

| Received RBF intervention (ref: No) | ||||||

| Yes | 0.97 (0.77, 1.21) | 0.779 | 1.24 (0.97, 1.59) | 0.088 | 1.25 (0.78, 2.00) | 0.348 |

| Province characteristics | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Province (ref: Parwan) | ||||||

| Badakhshan | 0.45*** (0.30, 0.68) | ≤0.001 | 0.30*** (0.14, 0.60) | ≤0.001 | 0.71 (0.19, 2.73) | 0.624 |

| Takhar | 0.44*** (0.29, 0.65) | ≤0.001 | 0.54** (0.35, 0.84) | 0.006 | 0.30** (0.14, 0.64) | 0.002 |

| Samangan | 1.09 (0.74, 1.61) | 0.656 | 1.30 (0.84, 2.02) | 0.244 | 0.10*** (0.04, 0.24) | ≤0.001 |

| Balkh | 2.42*** (1.55, 3.78) | ≤0.001 | 0.64* (0.42, 0.98) | 0.042 | 0.73 (0.29, 1.82) | 0.494 |

| Jawzjan | 5.22*** (3.19, 8.53) | ≤0.001 | 1.54 (0.85, 2.78) | 0.154 | 0.57 (0.18, 1.85) | 0.346 |

| Bamyan | 1.64* (1.08, 2.48) | 0.021 | 1.05 (0.68, 1.64) | 0.816 | 0.12*** (0.50, 0.29) | ≤0.001 |

| Saripul | 2.53*** (1.47, 4.35) | ≤0.001 | 0.88 (0.44, 1.77) | 0.718 | 0.23*** (0.10, 0.54) | ≤0.001 |

| Panjsher | 0.83 (0.37, 1.85) | 0.649 | 1.04 (0.60, 1.98) | 0.895 | 2.04 (0.84, 4.90) | 0.112 |

| Year (ref: 2010) | ||||||

| 2013 | 0.84 (0.67, 1.06) | 0.145 | 1.30** (1.10, 1.55) | 0.003 | 1.03 (0.71, 1.50) | 0.859 |

| 2015 | 2.14*** (1.69, 2.70) | ≤0.001 | 2.52*** (2.12, 2.99) | ≤0.001 | 1.03 (0.75, 1.41) | 0.857 |

|

| ||||||

| Random effects | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Facility-level variance (se) | 0.19 (0.07) | 0.34 (0.09) | 1.59 (0.52) | |||

| Facility-level ICC | 5.22% | 8.89% | 27.53% | |||

| Village-level variance (se) | 0.11 (0.07) | 0.23 (0.09) | 0.88 (0.45) | |||

| Village-level ICC | 8.37% | 14.74% | 42.89% | |||

| Level 1 units | 9,705 | 9,698 | 3,036 | |||

| Level 2 units | 288 | 288 | 288 | |||

| Level 3 units | 144 | 144 | 144 | |||

Abbreviations: ANC: Antenatal care; EmOC: Emergency obstetric care; ICC: intraclass correlation coefficient; RBF: Results based financing; se: standard error

p ≤ 0.05,

p ≤ 0.01,

p ≤ 0.001

Women whose nearest public facility provided EmOC services had a higher odds of an in-facility childbirth compared to women whose nearest public facility did not provide EmOC (AOR: 1.24, 95% CI: 1.04, 1.48). Holding other covariates constant, travel time to the nearest public clinic was associated with a lower odds of in-facility childbirth (AOR: 0.94, 95% CI. 0.89, 0.99). Other covariates significantly associated with a higher odds of in-facility childbirth included inadequate or adequate ANC (Inadequate: AOR: 4.08, 95% CI: 3.48, 4.80; Adequate: AOR: 6.58, 95% CI: 4.97, 8.71), access to a motor vehicle (AOR: 1.26, 95% CI: 1.01, 1.57), wealth status in the upper two quintiles (4th: AOR: 1.31, 95% CI: 1.04, 1.64; 5th: AOR: 1.40, 95% CI: 1.10, 1.78), and education (Primary: AOR: 1.53, 95% CI: 1.18, 1.97; Secondary: AOR: 2.22, 95% CI: 1.68, 2.93).

Controlling for other covariates, travel time to the nearest public hospital was associated with a lower odds of bypassing the nearest public facility for childbirth (AOR: 0.95, 95% CI: 0.93, 0.98). The nearest public facility type associated with a lower odds of bypassing was Comprehensive Health Centres (AOR: 0.47, 95% CI: 0.28, 0.77) compared to Sub Health Centres. Also, satisfaction/perceived quality score of the nearest public facility was associated with a lower odds of women bypassing their nearest public facility (AOR: 0.34, 95% CI: 0.14, 0.82). Presence of a female health worker at the nearest public facility was not significantly associated with having a skilled ANC, in-facility delivery, or bypassing for childbirth.

Discussion

This study assessed the relationship between travel time and availability of and satisfaction/perceived quality of care with maternal healthcare service use from 2010 to 2015 in northern Afghanistan. These factors mainly contribute to delays in the decision to seek care and arrival at health facilities for maternal healthcare services. This study, to our knowledge, is the first on Afghanistan to illustrate the spectrum of maternal healthcare services use for ANC and in-facility childbirth, including factors associated with bypassing the nearest facility for childbirth. We discuss the key findings associated with these outcomes and how these findings may guide future programs and policies for improving maternal healthcare utilization.

We found that wealth status, education level, and satisfaction/perceived quality of care of the nearest facility were associated with women’s use of skilled ANC. This finding is consistent with prior research, where decreasing wealth and education or literacy levels were associated with a lower odds of obtaining care in East Africa (Ruktanonchai et al., 2016), India (Sridharan et al., 2017), and Columbia (Osorio et al., 2014). The association between satisfaction/perception of quality of care with skilled ANC uptake has been less explored, but qualitative studies report that women delay or restrict ANC visits due to poor staff attitudes and neglect (Finlayson & Downe, 2013; Simkhada et al., 2007). Despite barriers to skilled ANC use, over 60% of women with a previous birth had at least one visit; yet only a third delivered at a facility. This disparity has been reported in other LMICs (Magoma et al., 2010). A combination of community and health systems level interventions have been found to be most effective in increasing ANC uptake (Mbuagbaw et al., 2015).

Women’s education level and adequacy of ANC were also both strongly associated with in-facility childbirth. Adequate counselling on birth planning during ANC visits has been found to increase uptake of in-facility childbirth; additionally, simultaneous quality improvement of ANC and delivery services should be prioritized (Manzi et al., 2018; Morón-Duarte et al., 2018; Pervin et al., 2012). Longer distances and travel time to care have been found to significantly reduce women’s likelihood to use in-facility childbirth (Gabrysch et al., 2011; Gabrysch & Campbell, 2009). In Zambia, as distance doubled, the odds of in-facility childbirth decreased by 29% (Gabrysch et al., 2011). In Ghana, an increase in travel time of one hour reduced the odds of in-facility birth by 22% (Masters et al., 2013); in India, being 1km further from a health facility reduced the probability of in-facility birth by 4.5% (Kumar et al., 2014). Similarly, we found that increased travel time to the nearest public facility was associated with lower odds of in-facility childbirth in northern Afghanistan. While we are limited by the lack of service quality measures, the availability of EmOC at the nearest public facility was associated with higher odds of in-facility childbirth. A study in Ghana found that measured quality of care at the nearest facility was not associated with use, but when the nearest facility provided substandard EmOC care, in-facility childbirth was less likely (Nesbitt et al., 2016). In related analyses, published separately, we found poorer spatial access (increased travel time) to public health facilities in the nine provinces compared to what may be self-reported due to differences in measurement (C. Kim et al., 2020). Increasing spatial access to facilities and the availability of EmOC services may increase in-facility childbirth.

Consistent with Tappis, et al. (2016), we found that almost 60% of women who delivered in a facility bypassed their nearest public facility. Many factors may influence women’s decisions to give birth in a facility beyond travel time and the availability of EmOC services. Similar to other studies, we found that facility type (or level) and satisfaction/perceived quality of care at the nearest public facility were associated with women bypassing their nearest public facility for childbirth. Previous studies in East Africa found that bypassing behaviour was associated with perceived poor quality of care at the nearest facility and that women seek facilities that provide higher technical quality of care, often provided at hospitals (Kruk et al., 2009; Leonard et al., 2003). This is likely true in Afghanistan as we found that travel time to a public hospital was associated with a lower odds of bypassing.

There is a trade-off in decision-making between travel time and the quality of care provided at hospitals. A better understanding of quality components of delivery services may be informative of women’s preferences for care. Studies have found that the increased number of EmOC signal functions available was associated with a decreased odds of bypassing (Kanté et al., 2016; Salazar et al., 2016). In Afghanistan, public facilities offering EmOC services should be fully staffed to provide 24-hour emergency services; however, assessments have shown that not all of these facilities provide all signal functions or meet the minimum staffing requirements (Faqir et al., 2015; Kim et al., 2012). A qualitative study found that insecurity and conflict has affected health infrastructure, referral capacities, and the ability and willingness of health providers to work, particularly female providers (Carthaigh et al., 2015). These factors present additional barriers to accessing healthcare, as well as resulting in women having to deliver at home or bypass a public facility that does not provide adequate care. Although we found that the presence of a female health worker at the nearest public facility was not associated with any of the outcomes, this may be due to little variation as the majority of facilities had a female health worker or because specifically midwives and doctors were not captured, rather only the presence of any female health worker.

Strengths of this study include its use of unique secondary data that capture utilization behaviours across three time points (2010, 2013, and 2015) at the same villages and public facility catchment areas in nine provinces of northern Afghanistan. Repeated cross sections allowed us to control for time trends. Factors contributing to bypassing behaviour have not previously been explored in Afghanistan. The measurement of travel time in this study is a significant improvement over previous estimates due to the estimation techniques using spatial analysis. However, geographical coordinates are prone to measurement error and the travel times estimated would be an average at the village level, though likely correlated at the household level based on the study in Ghana (Nesbitt et al., 2014).

Limitations include limited generalizability to provinces that are geographically and ethnically different or to women who did not deliver in the previous two years; notably, this shortened recall period reduces the potential threat of recall bias. The situation in Afghanistan is also volatile and the security levels change rapidly in the country. We were unable to control for district-level security incidents due to limited data, and it is unclear how specific villages and households are affected. Yet, evidence has shown that conflict affects the access and use of healthcare services (Carthaigh et al., 2015). We calculated travel times to the nearest public facility, not the facility used for care, due to limitations in the data. Some spatial aggregation error may also result from using the village centroid over individually geocoded locations (compound of residence), leading to possible errors based on a woman’s location in her village. However, a study in Ghana found that the deviance between the measures calculated from village and compound was less than 30 minutes and were highly correlated for 98% of births and the same nearest facility was identified for 85% of births in their data (Nesbitt et al., 2014). We aggregated the provision of EmOC services over a full year which may not account for temporal trends and influences on utilization behaviour if a public facility was able to provide EmOC at one point throughout the year and women chose to deliver at the facility during that time. Year fixed effects were included to capture the influence of aggregate time trends. We were also unable to control for the quality of care at the nearest facility and the facility where a woman delivered. Use of HMIS data on EmOC status may not be reflective of actual signal function capacity at facilities; in other words, facilities report whether EmOC was fully or partially available but this is cross-checked with maternity registers to confirm whether all signal functions were performed during that time period or otherwise validated.

Conclusion

In Afghanistan, recommended maternal healthcare services are currently underutilized, and the health status of women remains among the poorest among LMICs (Bartlett et al., 2005). Improving the health of all women requires a better understanding of the access and use of healthcare and their changes over time. Afghanistan has made progress in expanding access to key maternal healthcare services during ongoing conflict; however, significant barriers to accessing maternal healthcare persist. Addressing barriers such as travel time to health facilities, perceptions of poor quality of care, availability of EmOC, and provision of full ANC are essential to ensure that women have access to life-saving services. Appropriate care seeking behaviour is important to ensure health system efficiency for achieving maximum population health gains. Policies are needed that incentivize continuous investment in outreach interventions targeting vulnerable communities, while simultaneously improving the availability and quality of maternal healthcare services. This study provides an improved understanding of the factors associated across the spectrum of maternal healthcare use. Linking spatial data with facility quality measures would enhance this analysis. Further research should examine the travel time to the place where a woman received care to better understand facility choice and the trade-off between travel time and quality of care where a woman delivered. This study shows that greater understanding is needed to address women’s preferences for care in order to ensure the efficient delivery of healthcare services in communities.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank the Silk Route Training and Research Organization and the Afghanistan Ministry of Public Health for their support and sharing data for this study. We also thank Philip McDaniel at UNC Chapel Hill Davis Library for his GIS support.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest statement

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Data Availability Statement

Raw data were generated at the Silk Route Training and Research Organization and owned by the Afghanistan Ministry of Public Health. Derived data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author [CK] on request, with permission from the Afghanistan Ministry of Public Health. Several of the spatial datasets that support the findings of this study are openly available in the Humanitarian Data Exchange at data.humdata.org.

Contributor Information

Christine Kim, Department of Health Policy and Management, Gillings School of Global Public Health, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina, USA.

Hannah Tappis, Technical Leadership and Innovations Department, Jhpiego, Baltimore, Maryland, USA.

Laila Natiq, Silk Route Training and Research Organization, Kabul, Afghanistan.

Bruce Fried, Department of Health Policy and Management, Gillings School of Global Public Health, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina, USA.

Kristen Hassmiller Lich, Department of Health Policy and Management, Gillings School of Global Public Health, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina, USA.

Paul L. Delamater, Department of Geography, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina, USA

Morris Weinberger, Department of Health Policy and Management, Gillings School of Global Public Health, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina, USA.

Justin G. Trogdon, Department of Health Policy and Management, Gillings School of Global Public Health, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina, USA

References

- Akseer N, Bhatti Z, Rizvi A, Salehi AS, Mashal T, & Bhutta ZA (2016). Coverage and inequalities in maternal and child health interventions in Afghanistan. BMC Public Health, 16(Suppl 2). 10.1186/s12889-016-3406-l [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alba S, Sondorp E, Kleipool E, Yadav RS, Rahim AS, Juszkiewicz KT, & Burnham G (2020). Estimating maternal mortality : what have we learned from 16 years of surveys in Afghanistan ? BMJ Global Health, 5, e002126. 10.1136/bmjgh-2019-002126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ansari N, Tappis H, Manalai P, Anwari Z, Kim YM, van Roosmalen JJM, & Stekelenburg J (2020). Readiness of emergency obstetric and newborn care in public health facilities in Afghanistan between 2010 and 2016. International Journal of Gynaecology and Obstetrics, 148(3), 361–368. 10.1002/ijgo.13076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartlett L. a, Dahl S, Salama P, Mawji S, & Whitehead S (2005). Conceiving and dying in Afghanistan. Lancet, 365(9476), 2006. 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66692-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carthaigh NN, De Gryse B, Esmati AS, Nizar B, Van Overloop C, Fricke R, Bseiso J, Baker C, Decroo T, & Philips M (2015). Patients struggle to access effective health care due to ongoing violence, distance, costs and health service performance in Afghanistan. International Health, 7(3), 169–175. 10.1093/inthealth/ihu086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engineer CY, Dale E, Agarwal A, Agarwal A, Alonge O, Edward A, Gupta S, Schuh HB, Burnham G, & Peters DH (2016). Effectiveness of a pay-for-performance intervention to improve maternal and child health services in Afghanistan: A cluster-randomized trial. International Journal of Epidemiology, 45(2), 451–459. 10.1093/ije/dyv362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ESRI. (2011). ArcGIS Desktop: Release 10.5.1. Environmental Systems Research Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Faqir M, Zainullah P, Tappis H, Mungia J, Currie S, & Kim YM (2015). Availability and distribution of human resources for provision of comprehensive emergency obstetric and newborn care in Afghanistan: a cross-sectional study. Conflict and Health, 9(1). 10.1186/s13031-015-0037-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finlayson K, & Downe S (2013). Why do women not use antenatal services in low- and middle-income countries? A meta-synthesis of qualitative studies. PLoS Medicine, 10(1), e1001373. 10.1371/joumal.pmed.1001373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabrysch S, & Campbell O (2009). Still too far to walk : Literature review of the determinants of delivery service use. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 18(34), 1–18. 10.1186/1471-2393-9-34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabrysch S, Cousens S, Cox J, & Campbell OMR (2011). The Influence of Distance and Level of Care on Delivery Place in Rural Zambia: A Study of Linked National Data in a Geographic Information System. PLoS Medicine, 8(1). 10.1371/joumal.pmed.1000394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gopalan SS, Das A, & Howard N (2017). Maternal and neonatal service usage and determinants in fragile and conflict-affected situations: A systematic review of Asia and the Middle-East. BMC Women’s Health, 17(1), 1–12. 10.1186/s12905-017-0379-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heredia-Pi I, Servan-Mori E, Damey BG, Reyes-Morales H, & Lozano R (2016). Mesurer le caractère adéquat des soins prénataux: Une étude transversale nationale au Mexique. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 94(6), 452–461. 10.2471/BLT.15.168302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins-Steele A, Burke J, Foshanji AI, Farewar F, Naziri M, Seddiqi S, & Edmond KM (2018). Barriers associated with care-seeking for institutional delivery among rural women in three provinces in Afghanistan. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 18(1), 1–9. 10.1186/s12884-018-1890-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirose A, Borchert M, Cox J, Alkozai AS, & Filippi V (2015). Determinants of delays in travelling to an emergency obstetric care facility in Herat, Afghanistan: An analysis of cross-sectional survey data and spatial modelling. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 15(1). 10.1186/s12884-015-0435-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirose A, Borchert M, Niksear H, Alkozai AS, Cox J, Gardiner J, Osmani KR, & Filippi V (2011). Difficulties leaving home: a cross-sectional study of delays in seeking emergency obstetric care in Herat, Afghanistan. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 73(7), 1003–1013. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.07.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodgins S, & Agostino D (2014). The quality – coverage gap in antenatal care : toward better measurement of effective coverage. Global Health:, 2(2), 173–181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- INSO. (2011). International NGO Safety Organization. https://www.ngosafety.org/keydata-dashboard/ [Google Scholar]

- Kanté AM, Exavery A, Phillips JF, & Jackson EF (2016). Why women bypass front-line health facility services in pursuit of obstetric care provided elsewhere: A case study in three rural districts of Tanzania. Tropical Medicine and International Health, 21(4), 504–514. 10.1111/tmi.12672 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kassebaum NJ, Barber RM, Dandona L, Hay SI, Larson HJ, Lim SS, Lopez AD, Mokdad AH, Naghavi M, Pinho C, Steiner C, Vos T, Wang H, Achoki T, Anderson GM, Arora M, Biryukov S, Blore JD, Carter A, … Zuhlke LJ (2016). Global, regional, and national levels of maternal mortality, 1990-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. The Lancet, 388(10053), 1775–1812. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31470-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim C, Tappis H, McDaniel P, Soroush MS, Fried B, Weinberger M, Trogdon JG, Kristen Hassmiller Lich, & Delamater PL (2020). National and subnational estimates of coverage and travel time to emergency obstetric care in Afghanistan: Modeling of spatial accessibility. Health and Place, 66(October), 102452. 10.1016/j.healthplace.2020.102452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y-M, Zainullah P, Mungia J, Tappis H, Bartlett L, & Zaka N (2012). Availability and quality of emergency obstetric and neonatal care services in Afghanistan. International Journal of Gynaecology and Obstetrics: The Official Organ of the International Federation of Gynaecology and Obstetrics, 116(3), 192–196. 10.1016/j.ijgo.2011.10.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruk ME, Mbaruku G, McCord CW, Moran M, Rockers PC, & Galea S (2009). Bypassing primary care facilities for childbirth: A population-based study in rural Tanzania. Health Policy and Planning, 24(4), 279–288. 10.1093/heapol/czp011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S, Dansereau E, & Murray C (2014). Does Distance Matter for Institutional Delivery in Rural India? Applied Economics, 6846(May 2015). 32. 10.2139/ssrn.2243709 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard KL, Mliga GR, & Haile D (2003). Bypassing Health Centres in Tanzania: Revealed Preferences for Quality. Journal of African Economies, 11(4), 441–471. [Google Scholar]

- Magoma M, Requejo J, Campbell OMR, Cousens S, & Filippi V (2010). High ANC coverage and low skilled attendance in a rural Tanzanian district: a case for implementing a birth plan intervention. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 10, 13. 10.1186/1471-2393-10-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majrooh MA, Hasnain S, Akram J, Siddiqui A, & Memon ZA (2014). Coverage and quality of antenatal care provided at primary health care facilities in the “Punjab” province of “Pakistan.” PLoS ONE, 9(11). 10.1371/joumal.pone.0113390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manzi A, Nyirazinyoye L, Ntaganira J, Magge H, Bigirimana E, Mukanzabikeshimana L, Hirschhorn LR, & Hedt-Gauthier B (2018). Beyond coverage: Improving the quality of antenatal care delivery through integrated mentorship and quality improvement at health centers in rural Rwanda. BMC Health Services Research, 18(1), 1–8. 10.1186/s12913-018-2939-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masters SH, Burstein R, Amofah G, Abaogye P, Kumar S, & Hanlon M (2013). Travel time to maternity care and its effect on utilization in rural Ghana: A multilevel analysis. Social Science and Medicine, 93, 147–154. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.06.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayhew M, Hansen PM, Peters DH, Edward A, Singh LP, Dwivedi V, Mashkoor A, & Burnham G (2008). Determinants of skilled birth attendant utilization in Afghanistan: A cross-sectional study. American Journal of Public Health, 98(10), 1849–1856. 10.2105/AJPH.2007.123471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mbuagbaw L, Medley N, Aj D, Richardson M, & K HG (2015). Health system and community level interventions for improving antenatal care coverage and health outcomes. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotelchuck Milton. (1994). An Evaluation of the Kessner Adequacy of Prenatal Care Index and a Proposed Adequacy of Prenatal Care Utilization Index. American Journal of Public Health, 84(9), 1414–1420. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1615177/pdf/amjph00460-0056.pdf [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Public Health [Afghanistan], & Central Statistics Organization [Afghanistan], (2017). Afghanistan Demographic and Health Survey 2015. https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR323/FR323.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Public Health [Afghanistan], Royal Tropical Institute of Amsterdam (KIT), & Silk Route Training and Research Organization (SRTRO). (2015). An Impact Evaluation of the Results-based Financing Intervention in Afghanistan: Final Report 2015. In Ministry of Public Health, KIT Royal Tropical Institute, Silk Route Research and Training Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Public Health [Afghanistan], Silk Route Training and Research Organization (SRTRO), & Royal Tropical Institute (KIT). (2015). The Balanced Scorecard Report: Basic Package of Health Services 2015. [Google Scholar]

- MoPH. (2005). The Essential Package of Hospital Services for Afghanistan 2005/1384. [Google Scholar]

- MOPH Afghanistan. (2010). A Basic Package of Health Services for Afghanistan - 2010/1389. Health San Francisco, July, 1–90. http://www.moph.gov.af/en/index.php?id=23 [Google Scholar]

- Morón-Duarte LS, Ramirez Varela A, Segura O, & Freitas da Silveira M (2018). Quality assessment indicators in antenatal care worldwide: a systematic review. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 1–9. 10.1093/intqhc/mzy206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mumtaz S, Bahk J, & Khang YH (2019). Current status and determinants of maternal healthcare utilization in Afghanistan: Analysis from Afghanistan demographic and health survey 2015. PLoS ONE, 14(6), 1–14. 10.1371/joumal.pone.0217827 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nesbitt RC, Gabrysch S, Laub A, Soremekun S, Manu A, Kirkwood BR, Amenga-Etego S, Wiru K, Höfle B, & Grundy C (2014). Methods to measure potential spatial access to delivery care in low- and middle-income countries: a case study in rural Ghana. Int J Health Geogr, 13, 25. 10.1186/1476-072X-13-25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nesbitt Robin C., Lohela TJ, Soremekun S, Vesel L, Manu A, Okyere E, Grundy C, Amenga-Etego S, Owusu-Agyei S, Kirkwood BR, & Gabrysch S (2016). The influence of distance and quality of care on place of delivery in rural Ghana. Scientific Reports, 6(August). 1–8. 10.1038/srep30291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newbrander W, Natiq K, Shahim S, Hamid N, & Skena NB (2014). Barriers to appropriate care for mothers and infants during the perinatal period in rural Afghanistan: A qualitative assessment. Global Public Health, 9(supl), S93–S109. 10.1080/17441692.2013.827735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OCHA. (2019). The Humanitarian Data Exchange v1.32.2. https://data.humdata.org/search?q=afghanistan&ext_search_source=main-nav&page=1 [Google Scholar]

- Osorio AM, Tovar LM, & Rathmann K (2014). Individual and local level factors and antenatal care use in Colombia: a multilevel analysis. Cad. Saude Publica, Rio de Janeiro, 30(5), 1079–1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pervin J, Moran A, Rahman M, Razzaque A, Sibley L, Streatfield PK, Reichenbach LJ, Koblinsky M, Hruschka D, & Rahman A (2012). Association of antenatal care with facility delivery and perinatal survival – a population-based study in Bangladesh. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 12(1), 1. 10.1186/1471-2393-12-111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters DH, Noor A, Singh LP, Kakar FK, & Hansen M (2007). A balanced scorecard for health services in Afghanistan. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 85(2), 146–151. 10.2471/BLT.06.033746 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruktanonchai CW, Ruktanonchai NW, Nove A, Lopes S, Pezzulo C, Bosco C, Alegana VA, Burgert CR, Ayiko R, Charles ASEK, Lambert N, Msechu E, Kathini E, Matthews Z, & Tatem AJ (2016). Equality in maternal and newborn health: Modelling geographic disparities in utilisation of care in five East African countries. PLoS ONE, 11(8), 1–17. 10.1371/joumal.pone.0162006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salazar M, Vora K, & Costa A. De. (2016). Bypassing health facilities for childbirth : a multilevel study in three districts of Gujarat, India. 1, 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simkhada B, Teijlingen ER Van, Porter M, & Simkhada P (2007). Factors affecting the utilization of antenatal care in developing countries: systematic review of the literature. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 61(3), 244–260. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04532.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sridharan S, Dey A, Seth A, Chandurkar D, Singh K, Hay K, & Gibson R (2017). Towards an understanding of the multilevel factors associated with maternal health care utilization in Uttar Pradesh, India. Global Health Action, 10(1). 10.1080/16549716.2017.1287493 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- StataCorp. (2015). Stata Statistical Software: Release 14 (No. 14). StataCorp LP. [Google Scholar]

- Tappis H, Koblinsky M, Doocy S, Warren N, & Peters DH (2016). Bypassing Primary Care Facilities for Childbirth: Findings from a Multilevel Analysis of Skilled Birth Attendance Determinants in Afghanistan. Journal of Midwifery & Women’s Health, n/a-n/a. 10.1111/jmwh.12359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thaddeus S, & Maine D (1994). TOO FAR TO WALK: MATERNAL MORTALITY IN CONTEXT. Social Science & Medicine, 38(8), 1091–1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UCLA: Statistical Consulting Group, (n.d.). Multiple Imputation in Stata. Retrieved August 8, 2019, from https://stats.idre.ucla.edu/stata/seminars/mi_in_stata_pt1_new/

- UNICEF. (2017). Maternal mortality fell by almost half between 1990 and 2015. https://data.unicef.org/topic/matemal-health/matemal-mortality/

- USAID, & USGS. (2019). USGS Projects in Afghanistan. https://afghanistan.cr.usgs.gov/geospatial-reference-datasets

- WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, World Bank Group, & United Nations Population Division. (2019). Trends in Maternal Mortality: 2000 to 2017. https://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/matemal-mortality-2000-2017/en/

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2009). Monitoring emergency obstetric care: a handbook (World Health Organization (WHO) (ed.)). World Health Organization (WHO). [Google Scholar]

- Yeoh PL, Hornetz K, Shauki NIA, & Dahlui M (2015). Assessing the extent of adherence to the recommended antenatal care content in Malaysia: Room for improvement. PLoS ONE, 10(8), 1–15. 10.1371/joumal.pone.0135301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.