Abstract

Thrombopoietin receptor agonists (TPO-RAs) can mitigate preprocedural thrombocytopenia in patients with chronic liver disease (CLD) however their effects on procedural outcomes is unclear. In this meta-analysis, we aimed to better define the efficacy, thrombotic risk and bleeding mitigation associated with the use of preoperative TPO-RAs in patients with CLD. We performed a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled clinical trials to assess the use of preprocedural TPO-RAs in patients with CLD, searching MEDLINE, EMBASE and the Cochrane library database. Six publications comprising eight randomized trials (1229 patients; 717 received TPO-RAs, 512 received placebo) and three unique TPO-RAs were retrieved. The majority of the included procedures were endoscopic. TPO-RAs were significantly more likely to result in a preoperative platelet count greater than 50 × 109/L (72.1% vs 15.6%, RR 4.8, 95% CI 3.6–6.4 p < 0.00001. NNT 1.8) and reduced the incidence of platelet transfusions (22.5% vs 67.8%, RR 0.33, 95% CI 0.3–0.4 p < 0.00001. NNT 2.2). Total periprocedural bleeding was decreased in patients who received TPO-RAs (11.6% vs 15.6%, RR 0.64, 95% CI 0.5–0.9 p = 0.01. NNT 24.7) and there was no increase in the rate of thrombosis (2.2% vs 1.8% RR 1.25, 95% CI 0.6–2.9 p = 0.60. NNH 211.1). In patients with CLD the use of preprocedural TPO-RAs resulted in significant increased platelet counts, and decreased the incidence of platelet transfusions as compared to placebo. TPO use likewise decreased the incidence of total periprocedural bleeding without increasing the rate of thrombosis.

Keywords: Thrombopoietin, bleeding, procedures

INTRODUCTION:

Patients with chronic liver disease (CLD) are at increased risk for bleeding due to multiple complications, including portal hypertension, esophageal varices, reduced hepatic synthetic function and thrombocytopenia that correlates with the degree of liver disease. Thrombocytopenia in chronic liver disease is due primarily to reduced production of thrombopoietin (TPO) and splenic platelet sequestration secondary to portal hypertension.1

Prophylactic platelet transfusions are often considered prior to elective procedures in patients with CLD to reduce bleeding risk. There is ambiguity, however, in safe platelet count thresholds for various procedures due to a paucity of robust clinical data to define bleeding risks, and thus guidelines are mostly based on expert consensus.2 Recently, the FDA approved two oral thrombopoietin receptor agonists (TPO-RAs) as periprocedural adjuncts in patients with chronic liver disease prior to elective procedures. This approval was based on published data showing that avatrombopag (Doptelet ®) and lusutrombopag (Mulpleta ®) significantly reduced the utilization of procedural platelet transfusions.3,4 A prior study of the TPO-RA eltrombopag (Promacta ®) in a similar population was halted early due to concerns for an increased rate of splanchnic vein thrombosis.5

Unanswered questions remain about the use of TPO-RAs in this population. It is unclear how to interpret the primary endpoint of treatment-team guided platelet transfusions given the lack of clinical data to establish evidence-based transfusion thresholds for various procedures to prevent bleeding complictions.6 Likewise, the potential risks of both TPO-RA use and platelet transfusion in the setting of planned procedures are not fully understood. Finally, patients with CLD have globally altered hemostasis, of which thrombocytopenia is only one component. While platelet transfusions are not without risk and healthcare costs, the risks and healthcare costs associated with periprocedural TPO-RA use are not well understood with at least one trial stopped early due to excessive thrombotic complications.5 Lastly, it is unclear if TPO-RA use in this setting impacts clinically meaningful endpoints such as procedural or postprocedural bleeding. To address these questions, we performed a systemic review and meta-analysis of randomized double blinded placebo-controlled clinical trials evaluating preprocedural TPO-RA use in patients with thrombocytopenia secondary to CLD.

METHODS:

Article selection criteria

Studies were included if they described randomized, double blinded, placebo-controlled trials (RCTs) of adult patients with chronic liver disease and severe thrombocytopenia planning to undergo any elective procedure. We included studies of any TPO-RA compared to placebo. We limited our search to English language publications that reported sufficient data for analysis. We excluded studies evaluating TPO-RAs for the treatment of immune-mediated, cancer-associated or chemotherapy-induced thrombocytopenia as well as any single-arm study or studies not comparing TPO-RAs to placebo. The primary outcomes of this review were to assess (1) the efficacy of TPO-RAs at correcting severe thrombocytopenia as defined by an increase in platelet count over 50 × 109/L and (2) the incidence of platelet transfusions. The major safety endpoint was assessing rate of periprocedural bleeding. The rate of thrombosis was also assessed.

Data sources and searches

Electronic searches were performed in MEDLINE, EMBASE and the Cochrane library database. The complete search strategy is available in supplemental Table 1. Articles published from inception to January 2020 were eligible for inclusion.

Study selection

Two reviewers (IL and JJS) independently performed the study selection based on the defined inclusion and exclusion criteria. Disagreements were resolved through discussion or, if consensus could not be reached, through a third reviewer. For trials that reported results in multiple publications, we extracted data from the most complete publication and used the other publications as well as clinicaltrials.gov and study protocol resources to clarify the data. Results were reported in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRIMSA) statement for reporting of systematic reviews and meta-analyses of randomized clinical trials. 7

Data extraction and quality assessment

One reviewer (IL) performed data extraction independently using standardized data extraction sheets and a second reviewer (JJS) independently confirmed the data through review of each included trial. Discrepancies between the reviewers were resolved by consensus or through a third reviewer. The following data were extracted from the included trials: study design, year of publication, source of funding, population characteristics (number of patients, mean age, sex, race, ethnicity, cause of liver disease, Child-Turcotte-Pugh Score, mean or median baseline platelet counts and information on the included procedures), interventions (type of TPO-RA and dosing regimen), treatment in the control arm, and all data relevant to platelet counts, platelet transfusion, and bleeding events including severity when available. The supplemental data and data reported on clinicaltrials.gov were reviewed for each study and any outcomes data germane to this review but not reported in the published studies were included. To assess the validity of eligible randomized trials, two reviewers (IL, JS) assessed study quality using the methods specified in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions.8

Data abstraction and analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the baseline clinical characteristics of the included trials. Results from the different TPO-RAs were pooled to allow for an overall comparison against placebo. Pooled risk ratio (RR) and corresponding 95% confidence interval (CI) were calculated for all outcomes using the Mantel-Haenszel random-effects model. p- values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. A random-effects model was chosen based on the assumption that there would be heterogeneity in the individual studies as a result of variations in the included procedures, individual patient characteristics, and the decision to offer platelet transfusion or not. Forest plots were generated for relevant outcomes and the number needed to treat (NNT) for each outcome was reported. The I2 statistic was used to assess heterogeneity between individual studies. In accordance with the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions an I2 of 0 to 40% was considered unimportant heterogeneity; 30% to 60%, moderate heterogeneity; 50% to 90%, substantial heterogeneity; and 75% to 100%, considerable heterogeneity.8 Review Manager (RevMan, version 5.3; the Nordic Cochrane Centre, the Cochrane Collaboration, 2014, Copenhagen, Denmark) was used to perform all analysis.

RESULTS:

Study identification and selection

Using electronic searches in MEDLINE, EMBASE, 410 citations were identified (Supplemental Figure 1). Fifty-six additional citations were identified in the Cochrane library database. After removal of duplicates 381 unique records were screened. Of these, 223 studies underwent full-text review. After full-text review, 217 studies were excluded. Reasons for exclusion included non-human studies, review articles, foreign language articles, studies evaluating an alternative clinical question, phase 1 clinical trials, unblinded trials, post-marketing trials and retrospective studies. A total of 6 studies comprising 8 distinct study groups were included (four trials evaluating avatrombopag9,10, three trials evaluating lusutrombopag11–13 and one trial evaluating eltrombopag5), totaling 1229 patients. Among the 8 trials, 717 patients were assigned to receive a TPO-RA, and 515 patients to receive placebo. The main characteristics of the included studies are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Included study characteristics

| Author | Year | Trial Name | Clinical trial accession | Study design | No. patients | Location | TPO-RA | Dose | Length of follow-up | PVT screening |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Afdhal | 2012 | ELEVATE | NCT00678587 | Phase III | 292 | 13 countries | Eltrombopag | 75mg daily for 14 days | 30 days PP | no |

| Terrault | 2014 | 2014-A | NCT00914927 | Phase II | 67 | USA, multicenter | Avatrombopag | Variable dosing (1G) up to 7 days | 30 days PT | no |

| Terrault | 2014 | 2014-B | NCT00914927 | Phase II | 63 | USA, multicenter | Avatrombopag | Variable dosing (2G) up to 7 days | 30 days PT | yes |

| Terrault | 2018 | ADAPT-1 | NCT01972529 | Phase III | 231 | 20 countries | Avatrombopag | 40 OR 60mg daily for 5 days | 35 days PT* | yes |

| Terrault | 2018 | ADAPT-2 | NCT01976104 | Phase III | 204 | 16 countries | Avatrombopag | 40 OR 60mg daily for 5 days | 35 days PT* | yes |

| Hidaka | 2019 | L-PLUS 1 | JapicCTI-132323 | Phase III | 96 | Japan, multicenter | Lusutrombopag | 3mg daily for up to 7 days | 28 days PT | yes |

| Peck-Padosavlijevic | 2019 | L-PLUS 2 | NCT02389621 | Phase III | 215 | 22 countries | Lusutrombopag | 3mg daily for up to 7 days | 28 days PT | yes |

| Tateishi | 2019 | JapicCTI-121944 | Phase IIb | 61 | Japan, multicenter | Lusutrombopag | Variable dosing^ up to 7 days | 28 days PT | yes |

(1G) - 100mg 1G formulation day 1 followed by: 20mg daily days 2–7 OR 40mg daily days 2–7 OR 80mg daily days 2–7; (2G) - 80mg 2G formulation day 1 followed by: 10mg daily days 2–7 OR 20mg daily days 2–4 then placebo days 5–7;

= 2mg qD x 7 days OR 3mg qD x 7 days OR 4mg qD x 7 days; (stopped days 5–7 if plts >50K and >20K from baseline.)

PT = post treatment;

PT= post treatment start; PP = post procedure. PVT = portal vein thrombosis; TPO-RA = thrombopoeiten receptor antagonist

Study quality

The risk of bias was assessed using the Cochrane tool as detailed in supplemental Figure 2. Potential bias was noted in one study due to incomplete reporting of outcome data5 and in two trials due to incomplete blinding of the outcome assessment.10 Overall the risk of bias of the included studies was low.

Baseline characteristics of the included studies and patients

The baseline characteristics of the included patients are shown in Table 2. All of the 8 studies were sponsored by pharmaceutical companies. The mean ages of participants ranged from 52.5 to 67.8 years old with the majority of patients having Child Pugh class A or B liver disease and only a minority having Child Pugh class C disease. Chronic viral hepatitis was the most common cause of liver disease among the included studies. Among the various TPO-RA clinical trials adverse events were generally mild to moderate and were similar to placebo. Common adverse events included headache and abdominal discomfort.

Table 2.

Baseline patient characteristics

| Race and Ethnicity | Etiology of chronic liver disease | Severity of chronic liver disease | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Age M (SD) |

Sex | White | Asian | B/AA | Hispanic or Latino | HCV | HBV | Alcohol | NASH | AI/Misc | Child-Pugh: A | Child-Pugh: B | Child-Pugh: C | MELD Mdn |

Baseline platelet count (x109/L) |

| ELEVATE | 52.5 (11.4) | 64.4%M; 35.6%F | 61.0% | 36.6% | 2.1% | - | 67.47% | 13.01% | 7.19% | 46.2% | 43.8% | 9.6% | 12 (6–25) |

Mdn 40 (80–222) | ||

| L-PLUS 1 | 67.8 (8.6) | 53.1%M; 46.9%F | *100% | - | 76.17% | 4.47% | 19.34% | 38.85% | 44.79% | 16.38% | 12–13 | Mdn 38-40 (18–55) | ||||

| L-PLUS 2 | 55.7 (11.3) | 62.3%M; 37.7%F | 79.5% | 14.9% | 0.47% | 12.1% | 82.57% | 4.80% | 12.70% | 41.30% | 44.47% | 12.70% | 12–13 | Mdn 38-42 (18–57) | ||

| ADAPT-1 | 56.3 (10.06) | 68.4%M; 31.6%F | 55.4% | 38.5% | 2.2% | 13.0% | 61.90% | 14.29% | 6.06% | 16.45% | 56.3% | 38.5% | 3.9% | 10–11 (6–22) |

M 36.4 (8.71) | |

| ADAPT-2 | 58.2 (12.24) | 62.3%M; 37.7%F | 64.2% | 27.0% | 2.9% | 22.1% | 52.45% | 14.71% | 12.75% | 20.10% | 55.4% | 36.8% | 7.4% | 10–11 (4–23) |

M 38.1 (SD 7.35) | |

| Terrault 2014 - A | 54.4 (6.88) | 73.1%M; 26.9%F | 89.6% | - | - | - | 73.96% | 12.50% | 8.30% | 7.30% | 50.0% | 50.0% | 0.0% | - |

M 40.4 (6.6) |

|

| Terrault 2014 - B | 54.6 (6.19) | 61.9%M; 38.1%F | 84.2% | - | - | - | 47.44% | 20.93% | 23.26% | 12.56% | 4.65% | 62.8% | 35.3% | 1.4% | - |

M 37.6 (8.4) |

| Tateishi | 67.2 (8.78) | 57.4%M; 42.6F | *100% | - | 73.77% | 16.39% | 11.48% | 1.64% | 0.00% | 59.02% | 40.98% | 0.00% | - | M 40.96 (8.76) | ||

= not reported. Mdn. = median; M. = mean; SD = standard deviation. B/AA = black or African American; H/L = Hispanic or Latino.

= assumption of 100% Asian participants based on text reference to participants as “Japanese”, however formal Race and ethnicity not reported. HCV = Chronic hepatitis C virus infection; HBV = Chronic hepatitis B virus infection; Alcohol = Alcoholic liver disease; AI = autoimmune; Misc – miscellaneous; CP = Child-Pugh. Race reported for populations with >1% representation. See Supplemental Table 2 for complete data.

Included procedures:

A breakdown of the included invasive procedures is outlined in Table 3. Endoscopic procedures (esophagogastroduodenoscopy [EGD] or colonoscopy) were the most common types of procedures in treatment arm. When stratifying procedures based on bleeding risk as previously described4, the majority of procedures (60%) were in the lowest bleeding-risk category. Higher bleeding risk interventions such as vascular procedures represented only 12.9% of all procedures. Less than 1% of patients in each treatment arm underwent procedures involving open incision of a body cavity or tissue space.

Table 3.

Procedures grouped by risk categories (increasing risk from 1 through 4) as described by Afdhal et al. 2012.

| Risk | Procedure | Placebo | TPO-RA | No. studies |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | Total number of procedures / no. patients | 474 / 512 pts | 691 / 717 pts | 6 |

| 1 | Risk Category 1 procedures - no. (% all procedures) | 294 (62.00%) | 404 (58.48%) | |

| Paracentesis | 5 | 10 | 4 | |

| All endoscopic procedures | 175 | 260 | ||

| Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) | 162 | 236 | ||

| Colonoscopy | 9 | 22 | ||

| Argon plasma coagulation (APC) | 4 | 2 | 1 | |

| All HEENT procedures | 31 | 44 | 1 | |

| Dental procedure | 29 | 43 | 4 | |

| Non-dental HEENT procedure | 2 | 1 | 1 | |

| Gastrointestinal endoscopic procedures, large-volume paracentesis, dental extractions ^ | 83 | 90 | Afdhal | |

| 2 | Risk Category 2 procedures - no. (% all procedures) | 85 (17.95%) | 143 (20.69%) | |

| Liver procedure | 64 | 117 | ||

| RFA | 44 | 95 | 4 | |

| Liver biopsy | 16 | 17 | 6 | |

| Other liver procedure | 4 | 2 | 1 | |

| Percutaneous ethanol injection therapy | 0 | 3 | 2 | |

| Laparoscopic procedures | 1 | 3 | ||

| Percutaneous needle biopsy of an organ, primary HCC resection/ablation, laparoscopic procedures ^ | 20 | 23 | Afdhal | |

| 3 | Risk Category 3 procedures - no. (% all procedures) | 72 (15.20%) | 78 (11.28%) | |

| Vascular procedure | 72 | 78 | ||

| Transarterial chemoembolization | 43 | 53 | 3 | |

| Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt | 3 | 0 | 1 | |

| Vascular catheterization | 26 | 25 | 2 | |

| 4 | Risk Category 4 procedures - no. (% all procedures) | 4 (0.84%) | 4 (0.58%) | |

| Open incision of body cavity or tissue space ^ | 4 | 4 | Afdhal | |

| Unk. | Unknown risk category procedures - no. (% all procedures) | 19 (4.01%) | 62 (8.97%) | |

| NA | No procedure | 30 | 20 | 3 |

= variceal ligation, banding, sclerotherapy and/or biopsy Unk. = unknown; HEENT = head ear eyes nose throat

Afdhal 2012 published number of procedures in TPO-mimetic and placebo in summary based on the above risk categories. Procedures are thus presented in groupings for Afdhal participants. Further granularity of procedures in Table S3

Platelet count elevation over 50 × 109/L

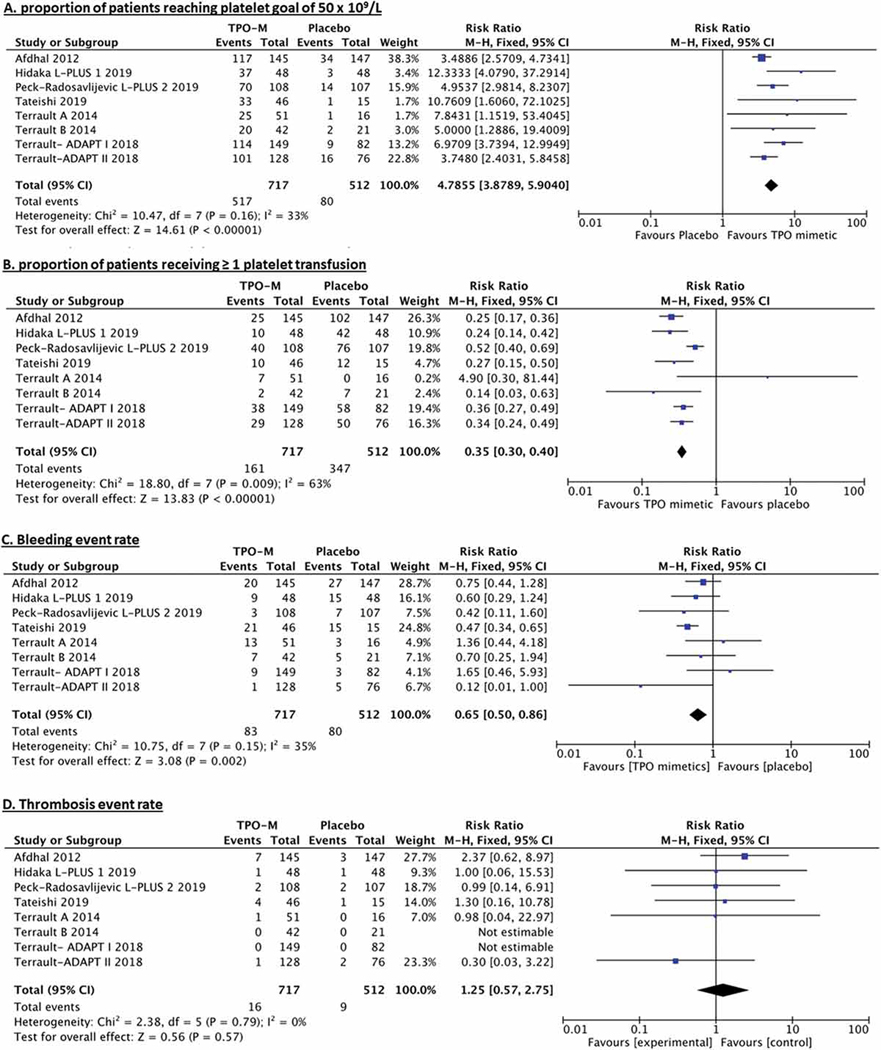

In the 8 trials comparing TPO-RA with placebo, elevation of platelet count over 50 × 109/L at any point during the study occurred in 72.1% of patients treated with TPO-RA vs 15.6% of those who received placebo. The individual rates of platelets response in each included trial are outlined in Table 4. The pooled relative risk for correction of severe thrombocytopenia (RR) was of 4.8, 95% CI 3.6–6.4 p < 0.00001. Figure 1A. The number needed to treat with TPO-RA (NNT) to reverse severe thrombocytopenia was 1.8. Of note, some but not all studies indicated this endpoint was assessed prior to any platelet transfusion.

Table 4.

Proportion of patients requiring at least 1 transfusion and proportion of patients with correction of severe thrombocytopenia.

| Proportion of patients who received ≥ 1 platelet transfusion^ | Proportion of patients who were “responders”, reaching ≥ 50×109/L | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Study | Placebo | TPO mimetic | Placebo | TPO mimetic |

| ELEVATE | 69.4% | 17.2% | 23.1% | 80.7% |

| L-PLUS 1 | 87.5% | 20.8% | 6.3%* | 77.1%* |

| L-PLUS 2 | 71.0% | 37.0% | 13.1%* | 64.8%* |

| ADAPT-1 | 70.7% | 25.5% | 11.0% | 76.5% |

| ADAPT-2 | 65.8% | 22.7% | 21.1% | 78.9% |

| Terrault 2014 - A | 0.0% | 13.7% | 6.3% | 49.0% |

| Terrault 2014 - B | 33.3% | 4.8% | 9.5% | 47.6% |

| Tateishi 2019 | 80.0% | 21.7% | 6.7%* | 71.7%* |

All transfusions during entire study included. No standardized transfusion in any of the studies.

= Responder defined by achieving plts > 50K and with >20K from baseline prior to platelet transfusion

Figure 1.

Forest plots of treatment effects (A) proportion of patients reaching platelet goal of 50 × 109/L (B) proportion of patients receiving platelet transfusion as well as safety outcomes (C) bleeding event rate (D) thrombosis event rate.

Platelet transfusion

In the included trials, 22.4% of patients treated with TPO-RA received at least one platelet transfusion, compared with 67.7% in the placebo arm. The individual rates of platelet transfusion in each included trial are outlined in Table 4. The pooled risk reduction for platelet transfusion was 0.33, 95% CI 0.3–0.4 p < 0.00001. Figure 1B. The NNT with TPO-RA to prevent platelet transfusion was 2.2.

Periprocedural bleeding

The periprocedural bleeding event rate was 11.6% in the TPO-RA group and 15.6% in the placebo group. Specific bleeding events are outlined in Table 5. Non-gastrointestinal mucosal bleeding (4.6%) and gastrointestinal bleeding (3.2%) were the most common forms of bleeding in the placebo and treatment arms respectively. (RR 0.64, 95% CI 0.5–0.9 p = 0.01), shown in Figure 1C. The NNT with TPO-RA to prevent one bleeding event was 24.7.

Table 5.

Safety endpoints of bleeding and thrombosis events, reported as event rate.

| Bleeding event | Placebo (events) | Tpo-RA (events) | No. studies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total (events/patients) | 80/512 (15.6%) | 83/717 (11.6%) | 8 |

| Anemia * | 1 | 10 | 3 |

| Contusion | 6 | 6 | |

| Hematoma | 8 | 3 | |

| Subcutaneous bleeding | 7 | 9 | |

| Hematuria | 10 | 2 | 3 |

| Mucosal bleeding (non-GI) | 24 | 11 | |

| Gastrointestinal bleeding | 9 | 23 | |

| Hemorrhage NOS | 15 | 19 | |

| Thrombotic events | Placebo | Tpo-RA | No. studies |

| Total (events/patients) | 9/512 (1.8%) | 16/717 (2.2%) | 8 |

| Studies without PVT screening | 3/163 | 7/196 | 4 |

| Studies with PVT screening | 6/246 | 8/330 | 2 |

| Studies with no thromboses | 0/103 | 0/191 | 2 |

No uniform threshold referenced by studies with anemia as bleeding outcome.

Unable to estimate severity of bleeding episodes given lack of uniformly adopted bleeding severity score that differentiates between mild bleeding, clinically relevant non-serious and clinically relevant serious bleeding episodes. More detailed bleeding events in Table S4

Thrombosis

The event rate of thrombosis detection periprocedurally was 2.2% in patients randomized to TPO-RA compared to 1.8% of patients randomized to placebo. Thrombotic events are reported in summary and stratified by PVT pre-screening vs no pre-screening in Table 5. (RR 1.25, 95% CI 0.6–2.9 p = 0.60), shown in Figure 1D. While this finding did not meet our prespecified definition of significance, the calculated NNH was 211.1. Two studies did not screen for splanchnic vein thrombosis prior to trial enrollment, one of which was terminated early due to concerns for an increased incidence of portal vein thrombosis.5,10

DISCUSSION:

This systematic review and meta-analysis found that procedural TPO-RA use in patients with chronic liver disease is associated with significant increase in platelet count (RR 4.79; NNT 1.8), decreased rates of platelet utilization (RR 0.35; NNT 2.2), and total periprocedural bleeding (RR 0.65; NNT 24.7), without any significant impact in the rate of thrombosis. We observed significant heterogeneity for the rate of platelet transfusion utilization (I2 = 63%). The observed heterogeneity can potentially be explained by the differences in desired platelet transfusion thresholds which likely vary by procedure, provider and center.

While none of the individual studies were powered for the primary endpoint of bleeding, perhaps the most important finding of our analysis was that the pooled analysis showed a statistically significant decrease in overall periprocedural bleeding with the use of TPO-RAs. The significance of this finding should be interpreted with caution however, as the included studies mostly involved low-risk procedures and did not uniformly describe the severity of bleeding. The significance of many of the reported bleeding events (e.g. unspecified anemia, epistaxis, ecchymosis and petechiae) is also questionable and many of these events may have been unrelated to the specific procedure leading to trial enrollment. The decreased bleeding seen with TPO-RA use may suggest however that the commonly employed platelet threshold of 50 × 109/L could be insufficient to prevent procedural bleeding in some circumstances and that higher counts may be needed for ideal hemostasis in patients with chronic liver disease. An alternative explanation could be that platelet transfusion somehow increases the risks of bleeding, a hypothesis influenced by the results of trials that evaluated platelet transfusion for intracerebral hemorrhage and neonatal bleeding and found paradoxically worse outcomes in the transfused patients.14,15 One mechanism behind this speculative hypothesis is that the proinflammatory phenotype of transfused platelets may enhance vascular permeability and incite the loss of endothelial barrier function. Another possibility is providers were inappropriately comfortable foregoing platelet transfusion in certain procedures which contributed to the increased rate of total bleeding in the patients assigned to placebo. It is also important to point out that hepatitis C and B were the most common causes of CLD in the studies that compose this meta-analysis. This point should be considered in terms of generalizability of the results. It is also possible that some patients had a component if immune thrombocytopenia compounding their presentation as viral hepatitis is associated with immune thrombocytopenic purpura.16 Lastly, It is important to note that thrombocytopenia is only one component of the globally-altered hemostatic milieu encountered in individuals with CLD, which is associated with an increased risk of both hemorrhage and thrombosis.17,18 This is evidenced by the non-trivial rate of thrombosis noted in this meta-analysis which was unaffected by the use of TPO-RAs.

There are several limitations to this study which should be addressed. First, there is high heterogeneity of the included procedures including their likely bleeding risks. In the absence of a standard to predict bleeding risk of procedures, we adopted a previously proposed procedure risk categorization,5 which allowed us to give context to the clinically meaningful outcomes. Second, all studies used physician guided platelet transfusion, with several specifically commenting on variable patterns of transfusion, no protocol for transfusion and concern regarding interpretation of this outcome. In addition, given the double-blinded nature of the studies included in this analysis, some proportion of patients in the TPO-RA arms of the trials also received platelet transfusions, potentially confounding all efficacy and safety outcomes. Third, given the inconsistent descriptions of bleeding episodes in the included trials it is challenging to assess the true clinical impact of the bleeding reduction with either experimental or standard of care interventions. The impact of TPO-RA use on the most clinically relevant endpoints, namely reducing major bleeding or clinically relevant non-major bleeding, remains unclear. Likewise, the paucity of high-risk surgical procedures in the analysis limits the applicability of the findings to such procedures. However, we feel the large size of this pooled analysis strengthens the findings and highlights a new signal of decreased bleeding risk in TPO-RA treated patients.

In conclusion, when compared with placebo, TPO-RAs are associated with less severe thrombocytopenia, and less platelet transfusions and less bleeding when given preprocedure for elective procedures in patients with chronic liver disease and severe thrombocytopenia, without any apparent increase in the risk of thrombosis. Future trials should ideally aim to include a larger proportion of patients with chronic liver disease undergoing higher-risk surgical procedures, with a primary endpoint of major and clinically-relevant non-major bleeding according to standardized criteria.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment of research support:

Authors of this work have been supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (HL101972, HL144113). H. Al-Samkari is the recipient of the National Hemophilia Foundation-Shire Clinical Fellowship Award, the Harvard KL2/Catalyst Medical Research Investigator Training Award, and the American Society of Hematology Scholar Award. J. Shatzel is supported by the National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (HL151367).

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: J.J.S. is a consultant for Aronora, Inc. H.A. receives research funding to his institution from Agios and Dova and is a consultant for Agios, Dova, and Amgen. The remaining authors declare no potential conflict of interest.

References:

- 1.Mitchell O, Feldman DM, Diakow M, Sigal SH. The pathophysiology of thrombocytopenia in chronic liver disease. Hepat Med. 2016;8:39–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nagrebetsky A, Al-Samkari H, Davis NM, Kuter DJ, Wiener-Kronish JP. Perioperative thrombocytopenia: evidence, evaluation, and emerging therapies. Br J Anaesth. Jan 2019;122(1):19–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cheloff AZ, Al-Samkari H. Avatrombopag for the treatment of immune thrombocytopenia and thrombocytopenia of chronic liver disease. J Blood Med. 2019;10:313–321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shirley M, McCafferty EH, Blair HA. Lusutrombopag: A Review in Thrombocytopenia in Patients with Chronic Liver Disease Prior to a Scheduled Procedure. Drugs. Oct 2019;79(15):1689–1695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Afdhal NH, Giannini EG, Tayyab G, et al. Eltrombopag before procedures in patients with cirrhosis and thrombocytopenia. N Engl J Med. Aug 23 2012;367(8):716–724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Olson SR, Koprowski S, Hum J, McCarty OJT, DeLoughery TG, Shatzel JJ. Chronic liver disease, thrombocytopenia and procedural bleeding risk; are novel thrombopoietin mimetics the solution? Platelets. 2019;30(6):796–798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000100-e1000100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Higgins JPT TJ, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.0 (updated July 2019) Cochrane. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Terrault N, Chen YC, Izumi N, et al. Avatrombopag Before Procedures Reduces Need for Platelet Transfusion in Patients With Chronic Liver Disease and Thrombocytopenia. Gastroenterology. Sep 2018;155(3):705–718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Terrault NA, Hassanein T, Howell CD, et al. Phase II study of avatrombopag in thrombocytopenic patients with cirrhosis undergoing an elective procedure. J Hepatol. Dec 2014;61(6):1253–1259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jansen PM, Pixley RA, Brouwer M, et al. Inhibition of factor XII in septic baboons attenuates the activation of complement and fibrinolytic systems and reduces the release of interleukin-6 and neutrophil elastase. Blood. Mar 15 1996;87(6):2337–2344. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peck-Radosavljevic M, Simon K, Iacobellis A, et al. Lusutrombopag for the Treatment of Thrombocytopenia in Patients With Chronic Liver Disease Undergoing Invasive Procedures (L-PLUS 2). Hepatology. Oct 2019;70(4):1336–1348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tateishi R, Seike M, Kudo M, et al. A randomized controlled trial of lusutrombopag in Japanese patients with chronic liver disease undergoing radiofrequency ablation. J Gastroenterol. Feb 2019;54(2):171–181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baharoglu MI, Cordonnier C, Al-Shahi Salman R, et al. Platelet transfusion versus standard care after acute stroke due to spontaneous cerebral haemorrhage associated with antiplatelet therapy (PATCH): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet. Jun 25 2016;387(10038):2605–2613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Curley A, Stanworth SJ, Willoughby K, et al. Randomized Trial of Platelet-Transfusion Thresholds in Neonates. N Engl J Med. Jan 17 2019;380(3):242–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pockros PJ, Duchini A, McMillan R, Nyberg LM, McHutchison J, Viernes E. Immune thrombocytopenic purpura in patients with chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Am J Gastroenterol. Aug 2002;97(8):2040–2045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hum J, Amador D, Shatzel JJ, et al. Thromboelastography Better Reflects Hemostatic Abnormalities in Cirrhotics Compared With the International Normalized Ratio. J Clin Gastroenterol. Sep 2020;54(8):741–746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lisman T, Porte RJ. Pathogenesis, prevention, and management of bleeding and thrombosis in patients with liver diseases. Res Pract Thromb Haemost. 2017;1(2):150–161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.