Abstract

Mutations in the methyl-CpG binding protein 2 (MECP2) gene cause Rett syndrome (RTT), an X-linked neurodevelopmental disorder predominantly impacting females. MECP2 is an epigenetic transcriptional regulator acting mainly to repress gene expression, though it plays multiple gene regulatory roles and has distinct molecular targets across different cell types and specific developmental stages. In this review, we summarize MECP2 loss-of-function associated transcriptome and proteome disruptions, delving deeper into the latter which have been comparatively severely understudied. These disruptions converge on multiple biochemical and cellular pathways, including those involved in synaptic function and neurodevelopment, NF-κB signaling and inflammation, and the vitamin D pathway. RTT is a complex neurological disorder characterized by myriad physiological disruptions, in both the central nervous system and peripheral systems. Thus, treating RTT will likely require a combinatorial approach, targeting multiple nodes within the interactomes of these cellular pathways. To this end, we discuss the use of dietary supplements and factors, namely, vitamin D and polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), as possible partial therapeutic agents given their demonstrated benefit in RTT and their ability to restore homeostasis to multiple disrupted cellular pathways simultaneously. Further unravelling the complex molecular alterations induced by MECP2 loss-of-function, and contextualizing them at the level of proteome homeostasis, will identify new therapeutic avenues for this complex disorder.

Keywords: Neurodevelopmental Disorders, Vitamin D, Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids, Neuroinflammation, Autism

1. Introduction

Rett syndrome (RTT) is a highly complex neurological disorder resulting from mutations in the gene MECP2, located on the X-chromosome (Amir et al., 1999). RTT patients are heterozygous for MECP2 mutations; due to X-inactivation, they display cellular mosaicism with approximately half of their cells expressing the mutant allele for MECP2 and approximately half expressing the functioning allele of MECP2. This disorder was first described by Andreas Rett in 1966 (Rett, 1966) with an account of girls who developed relatively normally for 6–18 months, after which they underwent a period of rapid regression, with loss of motor skills including purposeful hand movement. Deceleration of head growth, intellectual disability, ataxia, autonomic dysfunction, sleep problems, scoliosis, and seizures are also frequently observed in RTT (Hagberg et al., 1983; Leonard et al., 2016; Neul et al., 2010; Percy et al., 2010). RTT, with a prevalence of 1:10,000 – 1:15,000 live female births, is one of the most common causes of monogenic intellectual disability in females (Chahrour and Zoghbi, 2007; Hagberg, 1985).

Males with a mutation in their only copy of MECP2 present with neonatal encephalopathy and rarely survive long past birth (Kankirawatana et al., 2006), highlighting the essential nature of this epigenetic regulator. Precise regulation by MECP2 is, in fact, so essential to development that duplication of MECP2 also leads to a severe neurological disorder. MECP2 duplication syndrome primarily affects males, who display some overlapping phenotypes with RTT patients, including gait abnormalities, intellectual disability, and seizures (Van Esch et al., 2005). Individuals with MECP2 duplication syndrome also frequently display immunological dysfunction, with recurrent infections leading to an average age of death of 25 (Van Esch et al., 2005). Mutations that do not lead to a complete loss-of-function of MECP2 can also lead to other neurological impairments, including autism spectrum disorders and intellectual disability (Villard, 2007).

The discovery in 1999 that the majority of RTT cases are caused by mutations in MECP2 (Amir et al., 1999) was a major milestone and opened up an expansive field of study on the role of MECP2 and how its loss-of-function underpins RTT phenotypes. However, it could be argued that this discovery has raised more questions than answers. How does a mutation or duplication of this one gene lead to so many seemingly distinct phenotypes? And why is the central nervous system (CNS) so disproportionately impacted by the disruption of a protein that is broadly, if not ubiquitously, expressed? The overwhelming complexity of this disorder likely lies in the fact that MECP2 plays multiple gene regulatory roles and that it has distinct regulatory targets across different cell types and specific developmental stages.

Mutations in epigenetic regulators often lead to neurodevelopmental or neuropsychiatric disorders (Fahrner and Bjornsson, 2019; Zoghbi and Beaudet, 2016) and disruptions in epigenetic regulators, particularly chromatin modifiers, are disproportionately identified in studies of autism spectrum disorders (De Rubeis et al., 2014; Iwase et al., 2017; Zoghbi and Beaudet, 2016). MECP2, however, is a startling example of how disruptions in a single epigenetic reader can lead to widespread disruptions in multiple cellular pathways, and a highly complex disorder. In this review, we briefly highlight some of the mechanisms of action of MECP2 (MeCP2 in mouse), and the extensive transcriptome changes that result from its loss-of-function. Moving beyond the transcriptional changes, we survey global proteomic studies, which represent the ultimate manifestation of MECP2-mediated epigenetic effects. Finally, we identify specific proteins and cellular pathways that are disrupted in RTT and in vivo models of MeCP2 dysfunction, whether direct targets of MeCP2 or secondary effects from its loss-of-function, that could provide viable therapeutic targets.

2. MeCP2 is an epigenetic regulator with multiple functions

The multiple mechanisms of action of MeCP2 have been comprehensively reviewed elsewhere (Bellini et al., 2014; Connolly and Zhou, 2019; Horvath and Monteggia, 2018; Ip et al., 2018; Lyst and Bird, 2015;Tillotson and Bird, 2020); thus, we will just briefly summarize them here. MECP2 (Mecp2 in mouse) has two splice variants that differ in their amino termini. The Mecp2e1 isoform is more abundantly expressed in the brain than the Mecp2e2 isoform, and it is critical for nervous system function (Dragich et al., 2007; Vogel Ciernia et al., 2018). MeCP2 contains four primary functional domains, the methyl-CpG-binding domain (MBD), transcriptional repression domain (TRD), the NCOR-SMRT interaction domain (NID), located within the TRD, and a C-terminal domain (Lyst et al., 2013; Nan et al., 1997, 1993). Known pathogenic missense and nonsense mutations in MECP2 cluster within these highly conserved domains, highlighting their importance for the function of MECP2. In fact, a recent study employing truncated Mecp2 constructs to rescue RTT phenotypes found the NID and the MBD to be the most essential functional domains (Tillotson et al., 2017).

MeCP2 was first identified in 1992 by its ability to bind to methylated cytosines, specifically CpG dinucleotides, via its MBD (Lewis et al., 1992). In this capacity, it acts as an epigenetic reader – binding to methylated cytosines and recruiting SIN3 Transcription Regulator Family Member A (SIN3A), histone deacetylases, and NCOR/SMRT co-repressor complexes via its TRD and NID, to lead to transcriptional repression (Jones et al., 1998; Kokura et al., 2001; Lewis et al., 1992; Nan et al., 1998). MeCP2 has also been suggested to act as a transcriptional activator through recruitment of CAMP responsive element binding protein 1 (CREB1), posited to explain why many genes are down-regulated rather than up-regulated in the absence of Mecp2 (Chahrour et al., 2008). However, whether these changes all represent direct targets of MeCP2 or secondary effects is not clear, and the preponderance of evidence indicates MeCP2 primarily functions as a transcriptional repressor by binding to methylated DNA and acting as an epigenetic reader (Ip et al., 2018; Lavery and Zoghbi, 2019; Lyst and Bird, 2015; Tillotson and Bird, 2020).

More recently it has been found that MeCP2 also binds to methylated cytosines outside CpG dinucleotides (Guo et al., 2014; Kinde et al., 2015; Lagger et al., 2017). In fact, methylated CH (where H is A, T, or C) increases significantly as neurons mature (Lister et al., 2013), leading to the hypothesis that the lack of MeCP2 binding to mCH as the brain develops is what underpins the delayed onset of RTT symptoms (Chen et al., 2015). MeCP2 recruitment to methylated CA, in particular, is proposed to play a key role in the down-regulation of genes within the brain. MeCP2 can also bind to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC) (Mellén et al., 2012). MeCP2 has high affinity to 5hmCAC while its affinity to 5hmCG, which is far more abundant in the brain, is very low (Kinde et al., 2015; Lagger et al., 2017; Mellén et al., 2017); thus, the oxidation of mCG to hmCG could lead to transcriptional activation due to reduced repression by MeCP2 (Ip et al., 2018; Lavery and Zoghbi, 2019; Mellén et al., 2017).

Additional evidence suggests that MeCP2 might also act as a structural protein. In neurons, MeCP2 expression levels approach those of histones (Skene et al., 2010) and MeCP2 has been proposed to modify chromatin architecture globally (Baker et al., 2013; Skene et al., 2010). In the absence of MeCP2, there is an increase in histone deacetylation and histone H1, leading to alterations in chromatin structure (Nan et al., 1997; Skene et al., 2010). Further, MeCP2 has conserved AT hook domains that have been proposed to assist in chromatin remodeling (Baker et al., 2013). MeCP2 has also been reported to regulate microRNAs (miRNAs) within the brain (Ip et al., 2018), which can then lead to further alterations in gene expression. It might hinder miRNA processing by binding to DiGeorge syndrome critical region 8 (DGCR8) and preventing the formation of the DGCR8-Drosha complex (Cheng et al., 2014). MeCP2 has, in fact, been reported to interact with over 40 binding partners, the interactions with which can be modified by multiple post-translational modifications (Tillotson and Bird, 2020). MeCP2 undergoes phosphorylation, acetylation, ubiquitination, and SUMOylation (Ausió et al., 2014; Bellini et al., 2014). This adds yet another level of complexity in the efforts to understand the function of this multifaceted epigenetic regulator, and how mutations in MECP2 lead to disrupted gene and protein regulation, aberrant neuronal morphology, altered neuronal circuitry, and the myriad symptoms of RTT.

A variety of Mecp2 loss-of-function models have been developed to study the functions of MeCP2, and these have provided crucial insight into the transcriptional targets of MeCP2, the proteome disruptions that occur with its loss-of-function, and the resulting phenotypes. Further, they have identified disrupted cellular pathways that could provide therapeutic targets for RTT. Details of phenotypes and behavioral differences observed in these models have been reviewed in detail previously (Ezeonwuka and Rastegar, 2014; Kyle et al., 2018; Ribeiro and MacDonald, 2020; Sanfeliu et al., 2019; Tillotson and Bird, 2020). The Mecp2tm1.1Bird/J line, lacking exons 3 and 4, was one of the earliest RTT models generated (Guy et al., 2001) and has been the most commonly used model for transcriptome studies and rescue experiments. Other early models commonly used include the loss-of-function Mecp2tm1.1 Jae, which has a deletion of exon 3 (Chen et al., 2001), and the truncation model Mecp2308, which has a stop codon inserted after codon 308 (Shahbazian et al., 2002). Floxed alleles and flox-stop alleles have allowed for conditional excision and re-expression of Mecp2, respectively, in distinct tissues or cell types, further delineating the specific targets and roles of MeCP2 across cell types and brain regions. More recent mouse lines have been generated that carry patient-identified missense mutations affecting MeCP2 function (S421A, R270X, R306C, G273X, T158M and R106W) (Cohen et al 2011; Baker et al 2013; Lyst et al 2013; Johnson et al 2017). Patient-derived induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) are also being used to study MECP2 mutations, with the advantage of differentiation into multiple CNS cell types. This allows for studying effects of MeCP2 disruption on phenotype and biology directly in the cell type of interest. These models are shedding additional light on the functions of MeCP2, as well as the variability found in RTT.

3. Mecp2 loss-of-function causes widespread transcriptional disruptions

Given the near-ubiquitous nature of MeCP2 expression and its role in epigenetic and transcription regulation, it is unsurprising that disruptions in Mecp2 are associated with transcriptome-wide changes in many different cell and tissue types. A recent review characterized these changes across 38 datasets from studies utilizing mouse models of Mecp2 dysfunction, and identified over 400 genes that were differentially expressed in Mecp2-mutant mice versus controls (Sanfeliu et al., 2019). These genes are enriched for 76 biological pathways including axon guidance, circadian entrainment, calcium signaling, insulin secretion, GABAergic and glutamatergic synapse and inflammation (Sanfeliu et al., 2019) - all processes that are disturbed in RTT (Balakrishnan and Mironov, 2018; Boban et al., 2018; Borg et al., 2005; Cooke et al., 1995; De Felice et al., 2013; Mironov et al., 2009; Oyarzabal et al., 2020). However, these expression changes are not consistent across multiple studies from the same tissue type or brain region, suggesting that the technique used for transcriptomic studies, nature of Mecp2 dysfunction, type of mutation, and post-translational modifications of MeCP2 that regulate its activity may alter the transcriptome perturbations that are observed.

In addition to the specific Mecp2 mutation (Baker et al., 2013; Johnson et al., 2017), transcriptional changes may also be subject to differences in sex and stage of disease. While male Mecp2 null mice and female heterozygous mice can show similar phenotypic manifestations of RTT, their ages of onset are vastly different (Guy et al., 2001). Due to the severity of phenotype coupled with earlier onset of disease, greater than 30 transcriptome studies have been performed in male mice and only 4 studies reported in females (Sanfeliu et al., 2019), although female mice are the more clinically relevant model. Studies in female mice have demonstrated that Mecp2 loss-of-function leads to both cell-autonomous and non-cell-autonomous disruptions in gene expression (Ribeiro and MacDonald, 2020). The brain of heterozygous female mice is a mosaic of MeCP2− and MeCP2+ cells due to random X-inactivation. MeCP2− and MeCP2+ cortical pyramidal neurons from the heterozygous brain display distinct patterns of gene expression, demonstrating cell autonomous disruptions in the regulation of gene expression by the loss of MeCP2 (Johnson et al., 2017; Renthal et al., 2018). However, a large of number of genes are also differentially expressed in MeCP2+ neurons from heterozygous female mice when compared to wildtype neurons from a control mouse brain. These non-cell-autonomous differentially expressed genes do not seem to be directly regulated by MeCP2, most likely resulting from indirect effects of the mosaic RTT brain environment (Johnson et al., 2017; Renthal et al., 2018) further adding to the complexity of RTT.

Of note, a majority of studies performed in male Mecp2-null mice were carried out when the mice were highly symptomatic (i.e. between 6 – 8 weeks of age). Thus, a caveat of many studies in male mice is also the inability to distinguish direct MeCP2 targets versus secondary transcriptomic changes that occur due to disease phenotype. This has been addressed in part by studies performed during neural development (Bedogni et al., 2016; Kishi et al., 2016), and where tissue (Baker et al., 2013; Jordan et al., 2007) or cell-specific gene expression (Zhao et al., 2017) changes were compared at different stages of disease, or Mecp2 expression was conditionally reactivated in the brain (Cortelazzo et al., 2020). Whether disrupted cellular pathways are a result of direct loss of transcriptional regulation by MeCP2 or are the result of secondary changes is likely not relevant to the development of therapeutic treatments, however. Identifying the disrupted downstream cellular pathways, whether direct transcriptional targets of MeCP2 or not, and restoring homeostasis will be essential to alleviating phenotypes.

4. Protein and cellular pathway alterations consistently identified with Mecp2 dysfunction

In order for these genome-wide transcriptomic changes to ultimately affect cellular function, they have to be reflected by changes in protein expression. There have been few broad proteome studies in comparison to transcriptome analyses, however, and these studies have found that protein changes are minimal, relative to the extensive transcriptional changes that have been identified (Krishnaraj et al., 2019; Pacheco et al., 2017). Further, there is often weak correlation between mRNA and protein expression changes (Pacheco et al., 2017), and for a subset of genes, transcription versus protein changes show completely opposite trends (Delépine et al., 2015; Matarazzo and Ronnett, 2004). We summarize results from global proteome studies across RTT animal models and patient studies that have used an unbiased approach or assayed more than 10 proteins, either during a developmental timepoint (Table 1a) or at an adult, symptomatic stage (Table 1b).

Table 1A:

Summary of proteome studies performed at developmental stages in mouse and human RTT models or patients

| Study | Type of sample used | Mouse model/cell line | Age/N | Sex | Method | Key proteins altered/key findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Cortelazzo et al., 2020) | Cortex | Mecp2stop/y and Mecp2stop/y Nestin Cre (rescue at 17 weeks) | 5,17 weeks n = 6 per group | M | MS | 13 DEPs at 17 weeks in Mecp2stop/y versus reactivation; 12 rescued; Proteostasis (HSP7C, CH60, PDIA3), peptide assembly (STIA3) redox (PRDX6 and SODC) glycolysis (TPIS and KPYM) and energy homeostasis (LDHB, ODPB), NO regulation (DDAH1) neuronal development (DPYL2); |

| (Matarazzo and Ronnett, 2004) | Olfactory bulb (OB)and epithelial tissue (OE) | Mecp2 null | 2,4 weeks | M | LC/MS/MS | Greater number of DEPs vs WT (14 across OB and OE combined; 3-fold cutoff) including Lamin C, CRMP2 (Cytoskeleton), Histone 1 H2aK, H3 (OE) and Creatine Kinase, Calretinin (OB) |

| (Rodrigues et al., 2020) | human iPScs and derived neural progenitor cells and cortical neurons | Clones derived from 5 lines including one WT control, an isogenic RTT from a female patient and 3 iPSC lines RTT lacking E1 from a separate patient | F | TRAP seq and RNA seq | RTT neurons have diminished translation and over 2100 genes show perturbed ribosome engagement; NEDD4L E3-ubiquitin ligase targets show decreased ubiquitination and increased protein accumulation | |

| (Varderidou-Minasian et al., 2019) | iPSc derived neural cultures | MECP2 exons 3–4 mutation from RTT patient | 3 RTT clones and 3 isogenic controls from one individual | NM | LCMS/MS | 39 DEPs (27 upregulated and 12 downregulated in RTT vs. controls - all timepoints combined); Includes proteins involved in immunity, actin skeleton, calcium binding and metabolism |

| (Sharma et al., 2017) | Exosomes from iPSc derived neural cultures | Patient-MECP2 gr mutant Q83X and isogenic control Crispr-Cas9-mediated rescue of MECP2 | 6 preps from each oup | M | MS | 237 DEPs (1.5-fold or higher) with neurogenesis being significantly overrepresented; Flotillin, GAP43, Alix validated by Western blot. Control exosomes restore MECP2 knockdown neural culture numbers whereas patient derived exosomes do not. |

| (Kim et al., 2019) | iPSc derived neural cultures | (Q83X) (N126I) MECP2 mutant samples and respective unaffected fathers (WT83 and WT126) | 7–10 replicates per exp | M | SILAC and LC-LC/MS/MS | SILAC in RA treated cells identified DEPs involved in glial differentiation (GFAP, S100B) and MS in undifferentiated cells showed altered LIN28 expression (increased in mutant neural progenitor cells). |

Studies are presented in reverse chronological order grouped based on tissue type; only MECP2 mutation RTT studies in murine and human models have been included. Abbreviations used: NM: sex not mentioned; MS: Mass Spec; DEPs: Differentially expressed proteins; DEGs: Differentially expressed genes; SILAC: Stable Isotope Labeling by/with Amino acids in Cell culture, Co-iP: Coimmunoprecipitation, MALDI TOF: Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization-Time Of Flight, 2D GE: 2D Gel electrophoresis, RNA seq: RNA sequencing, TRAP seq: translating ribosome affinity purification; exp: experiment; DEC: differentially expressed compounds

Table 1B:

Summary of proteome studies performed at adult or symptomatic stages in mouse and human RTT models or patients.

| Study | Type of sample used | Mouse model/cell line | Age/N | Sex | Method | Key proteins altered/key findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Pacheco et al., 2017) | Cortex | Mecp2Jae/y | P 60 n = 4 per genotype |

M | LCMS/MS | 465 DEPs vs. WT. Only 35 overlapped with DEGs (q < 0.05, p < 0.1, cutoff) including FKBP5(immunoregulation), ERp72 (Pdia4) (protein chaperone), SUN2 (nuclear envelope) |

| (Maxwell et al., 2013) | Cerebellu m |

Mecp2tm1Tam/y male mice | 11–12 weeks - | M | Co-iP MS |

MECP2 interacts with 26 proteins including TOP2B (Topoisomerase), DHX9 (helicase), PRP8(spliceosome) and long non coding RNAs including MALAT1 and RCNR3 |

| (Neul et al., 2020) | Plasma | RTT patients and age, sex matched unaffected sibling controls | n = 34 patients, n = 37 controls | NM | LC-MS/MS | 66 metabolites (uncorrected p value), 27 metabolites (FDR, p < 0.05). Altered amino acids include cysteine, phenylalanine, serine and glycine and pathways include oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction and gut microbiota |

| (Cortelazzo et al., 2017a) | Plasma | Mecp2 308+/− mice | 10–12 months old | F | 2-DE/MALDI-ToF/ToF | Altered expression of acute phase response proteins KNG1, FETA, MBL2, A1AT, RFE, ALBU and APOA1 and inflammation-modulating proteins VTDB, CD5L |

| (Cortelazzo et al., 2017b) | Plasma | RTT patients and healthy controls | n = 15 patient 1.6–17.3 years old and n = 30 health controls 1.9–18.9 years old | F | MS and ELISA | Altered APR protein expression including A1AT, A1BG, TRFE, IGHA1, IGHM, TRFE, ITIH4, FIBA CLUS, APOA1 a and cytokines TNF-a, IL-5, IL-6, IL-8, IL-37, IL-22 and I-TAC |

| (Leoncini et al., 2015) | Plasma | RTT patients and healthy controls | n = 16 patients 3–39 years old and n = 24 controls 2–32 years old | F | ELISA | Altered expression of TNF-α, IL-37, IL-22, IFN- gamma and IL-12p70 in RTT |

| (Cortelazzo et al., 2014) | Plasma | RTT patients and healthy controls | n = 25 patients with different MECP2 mutations, 3–10 years old and n = 40 age matched controls | F | 2-DE/MALDI-TOF | APR DEPs included CFAB, TRFE, ALBU, A1AT, FIBG, HPT, TTHY, ALBU, APOA1, RET4, SAA1 and immune proteins FETUA, IGHG2 |

| (De Felice et al., 2013) | Plasma | RTT patients and healthy controls | n= 24 patients with different MECP2 mutations, 4–33 years old and n=24 healthy controls, 4.1–33 years old | F | 2DE/M ALDI TOF MS | APR DEPs included CFAB, FIBA, ALBU, A1AT, HPT, TTHY APOA4, CLUS, APOA1, RET4 and VTDB |

| (Cortelazzo et al., 2017a) | Plasma | Mecp2 308+/− mice | 10–12 months old | F | 2-DE/MA LDIToF/ToF | Altered expression of acute phase response proteins KNG1, FETA, MBL2, A1AT, RFE, ALBU and APOA1 and inflammation-modulating proteins VTDB, CD5L |

| (Cortelazzo et al., 2017b) | Plasma | RTT patients and healthy controls | n = 15 patient 1.6– 17.3 years old and n = 30 health controls 1.9–18.9 years old | F | MS and ELISA | Altered APR protein expression including A1AT, A1BG, TRFE, IGHA1, IGHM, TRFE, ITIH4, FIBA CLUS, APOA1 a and cytokines TNF-a, IL-5, IL-6, IL-8, IL-37, IL-22 and I-TAC |

| (Leoncini et al., 2015) | Plasma | RTT patients and healthy controls | n = 16 patients 3–39 years old and n = 24 controls 2–32 years old | F | ELISA | Altered expression of TNF-α, IL-37, IL22, IFN- gamma and IL-12p70 in RTT |

| (Cortelazzo et al., 2014) | Plasma | RTT patients and healthy controls | n = 25 patients with different MECP2 mutations, 3–10 years old and n = 40 age matched controls | F | 2-DE/MA LDITOF | APR DEPs included CFAB, TRFE, ALBU, A1AT, FIBG, HPT, TTHY, ALBU, APOA1, RET4, SAA1 and immune proteins FETUA, IGHG2 |

| (De Felice et al., 2013) | Plasma | RTT patients and healthy controls | n= 24 patients with different MECP2 mutations, 4–33 years old and n=24 healthy controls, 4.1–33 years old | F | 2DE/M ALDI TOF MS | APR DEPs included CFAB, FIBA, ALBU, A1AT, HPT, TTHY APOA4, CLUS, APOA1, RET4 and VTDB |

| (Cortelazzo et al., 2013) | Plasma | RTT patients that are sisters | n = 2 patient pairs carrying the same MECP2 mutation between siblings, 34–42 years old and n = 10 matched healthy controls | F | MALDI TOF MS | DEPs included FIBB, HBB, TRFE, HPT, IGHG2, and CO3 and CLUS |

| (Byiers et al., 2020) | Saliva | RTT patients and matched controls | 2–40 years of age; n = 16 per group | F | 12-plex human cytokine Luminex assay | IL-1β, IL-6, IL8, IL-10, and TNF-α elevated in RTT and correlated with clinical severity |

| (Pecorelli et al., 2016b) | Serum and PBMCs | RTT patients and controls | n = 10 patients, 3–26 years of age; n = 8 healthy controls age = 8–35 years old | F | Multiple x, ELISA assays | DEPs include increased IL-8, IL-9, and IL-13 in RTT and show similar alterations in mRNA in PBMCs |

| (Pecorelli et al., 2016a) | Fibroblasts | RTT patients and controls | n = 15 with classical RTT age = 18.7 ± 10.1) and n = 15 healthy controls age = 21.8 ± 15.9 years | F | 2D GE/MS/Western blot | Altered proteins included TPM1, TPM2, ACTB (beta actin) (cytoskeleton function), TCPZ, PDIA3, HSC70 and GRP78 (protein folding). Elevated NO production, iNOS mRNA levels in RTT |

Studies are presented in reverse chronological order grouped based on tissue type; only MECP2 mutation RTT studies in murine and human models have been included. Abbreviations used: NM: sex not mentioned; MS: Mass Spec; DEPs: Differentially expressed proteins; DEGs: Differentially expressed genes; SILAC: Stable Isotope Labeling by/with Amino acids in Cell culture, CoiP: Coimmunoprecipitation, MALDI TOF: Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization-Time Of Flight, 2D GE: 2D Gel electrophoresis

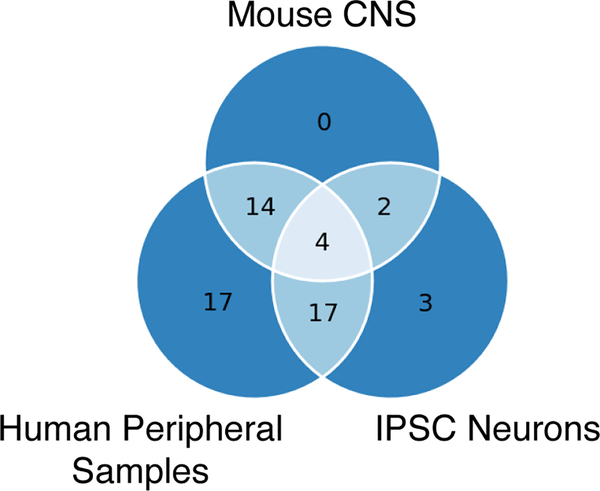

These recent proteome studies have uncovered novel findings that highlight the complexity of RTT. These include altered expression of metabolites in RTT plasma indicative of gut microbiota changes and accelerated aging (Neul et al., 2020); a shift in ratios of glial to neuronal differentiation markers (Kim et al., 2019), decreased global protein translation, decreased ubiquitination of a subset of proteins, and altered ribosome engagement of mRNAs (Rodrigues et al 2020) in RTT iPSC generated cells. However, we also observe several common themes across these proteomic studies. We performed Reactome pathway analyses (Jassal et al., 2020) on the dysregulated proteins identified in these studies and found many pathways that are common to two or more studies (Supplemental Table 1). Many of these pathways are, in fact, common across different sample types (Figure 1; Table 2), including Mecp2-mutant mouse CNS, RTT iPSC generated cells, and RTT peripheral samples (including plasma, saliva, and fibroblasts). Proteins altered are involved in neurodevelopment, inflammation regulation, cytokine production, the vitamin D pathway, protein folding, and cytoskeletal regulation. We highlight some of these pathways and focus on individual candidates that have been shown to be of biological relevance, that are altered across multiple studies and, in certain cases, currently being targeted for therapeutic intervention.

Figure 1: Extensive overlap of cellular pathways that are disrupted in the proteome of Rett syndrome models.

Reactome pathway analyses were performed on the proteins found to be dysregulated in multiple Rett syndrome studies. From the many pathways found to be dysregulated in two or more studies, many commonalities are observed when comparing studies performed on mouse Mecp2-mutant central nervous system tissues (Mouse CNS), RTT iPSC-derived neural progenitors and neurons (IPSC Neurons), and samples derived from RTT patients, which include plasma, saliva, and fibroblasts (Human Peripheral Samples). The overlapping pathways are listed in Table 2.

Table 2:

Overlapping Reactome Pathways Dysregulated in MECP2-mutant proteome studies.

| Mouse CNS + IPSC Neurons + Human Periphery | Interleukin-12 signaling |

| Interleukin-12 family signaling | |

| Gene and protein expression by JAK-STAT signaling after Interleukin-12 stimulation | |

| Response to elevated platelet cytosolic Ca2+ | |

| Mouse CNS + IPSC Neurons | Transcriptional Regulation by MECP2 |

| MECP2 regulates neuronal receptors and channels | |

| Mouse CNS + Human Periphery | Platelet activation, signaling and aggregation |

| HDL clearance | |

| Chylomicron assembly | |

| Hemostasis | |

| Cellular responses to stress | |

| Cellular responses to external stimuli | |

| ATF6 (ATF6-alpha) activates chaperones | |

| ATF6 (ATF6-alpha) activates chaperone genes | |

| rRNA processing in the mitochondrion | |

| tRNA modification in the mitochondrion | |

| Binding and Uptake of Ligands by Scavenger Receptors | |

| Scavenging by Class A Receptors | |

| Defective ABCA1 causes TGD | |

| Calnexin/calreticulin cycle | |

| IPSC Neurons + Human Periphery | Signaling by Interleukins |

| TRAF6 mediated NF-κB activation | |

| TAK1 activates NFκB by phosphorylation and activation of IKKs complex | |

| Regulation of Insulin-like Growth Factor (IGF) transport and uptake by Insulin-like Growth Factor Binding Proteins (IGFBPs) | |

| Insulin-like Growth Factor-2 mRNA Binding Proteins (IGF2BPs/IMPs/VICKZs) bind RNA | |

| GABA synthesis, release, reuptake and degradation | |

| EPHB-mediated forward signaling | |

| Post-translational protein phosphorylation | |

| PERK regulates gene expression | |

| Platelet degranulation | |

| Chaperone Mediated Autophagy | |

| ATF4 activates genes in response to endoplasmic reticulum stress | |

| Advanced glycosylation endproduct receptor signaling | |

| Clathrin-mediated endocytosis | |

| Muscle contraction | |

| Smooth Muscle Contraction | |

| Striated Muscle Contraction |

Lists of differentially expressed proteins from each of the 18 studies were converted into the human protein symbols, if necessary, to facilitate comparative analyses. Studies on metabolites or that reported protein complexes without denoting individual proteins were excluded from the analyses. The Reactome biological pathways (Jassal et al., 2020) were determined for the differentially expressed proteins from each of the remaining 13 studies (significance p < 0.05). Pathways that appeared in two or more studies were categorized by tissue type. Overlapping pathways between different tissue types are shown below and in Figure 1.

4.1. Disruptions in Proteins Associated with Neurodevelopment

RTT is a progressive neurodevelopmental disorder, with many symptoms that manifest postnatally during the final stages of neuronal maturation. Therefore, it is unsurprising that neurodevelopment-associated proteins are altered across multiple RTT studies (Cortelazzo et al., 2020; Kim et al., 2019; Rodrigues et al., 2020). For example, proteins found to be altered in exosomes produced by MECP2 LOF human induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs), compared to isogenic controls, had an over-representation of proteins involved in nervous system development and neurogenesis, including neuritogenesis, axonal guidance, and proliferation of neurons (Sharma et al., 2019). Increased expression of LIN28 - a neuron/glia fate commitment regulation protein, and decreased expression of the glial differentiation proteins Glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) and S100 calcium-binding protein B (S100B) were also found in neural progenitor cells (NPCs) differentiated from iPSCs derived from male patients with the Q83X or N126I MECP2 mutations, compared to healthy controls (Kim et al., 2019). LIN28 overexpression in wild type neurons decreased levels of synaptic markers and suppressed GFAP expression in control NPCs. In line with these findings, knocking down LIN28 in Q38X cells led to a partial rescue of the reduced levels of synaptic proteins in these cells. Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) studies in NPCs showed direct binding of MECP2 to the LIN28 promoter. The authors hypothesize that loss of MECP2 in RTT can lead to elevated LIN28 expression during early development causing imbalances in neuron to glia cell fate commitment contributing to a higher number of immature neurons. These neurodevelopmental changes may contribute to the multitude of symptoms seen in RTT.

A comparison of temporal proteomic changes (days 3, 9, 15, 22) in MECP2 mutant (exon 3, 4 deletion) patient-derived iPSCs versus isogenic control cells during neural cell differentiation found a total upregulation of 27 proteins and downregulation of 12 proteins in MECP2 mutant cells (Varderidou-Minasian et al., 2019). Proteins involved in neurodevelopment (dendrite formation and axon growth), immunity, calcium signaling, and metabolism were altered in RTT derived cells during early stages of neuronal differentiation, suggesting these changes occur before overt symptom onset. However, neurodevelopment associated proteins were altered across all timepoints and the number of differentially expressed proteins increased significantly at later time points, indicating a progressive disruption in the proteome. A similar neurodevelopmental study directly examined transcriptome vs. proteome changes by performing parallel translating ribosome affinity purification sequencing (TRAP-seq) and RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) across iPSC to NPC and NPC to neuronal cell transitions, in control versus MECP2 mutant iPSCs (Rodrigues et al., 2020). They found slightly less than a third of transcribed genes show a shift in ribosome engagement across both transitions and consisted of genes involved in neurodevelopment, glycolysis, transcription and translation factors. RTT neurons showed an overall decrease in protein translation and reduced mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1) activity. In addition, RTT neurons had lower levels of the neural precursor cell expressed developmentally downregulated gene 4-like (NEDD4L) ubiquitin ligase and increased protein levels of its protein targets, suggesting that increased protein stability due to lack of ubiquitination may explain some of the discrepancies between transcriptome versus protein changes for a subset of genes (Rodrigues et al., 2020).

4.2. Immune function alterations in RTT

Immune mediators, such as cytokines and chemokines, can regulate multiple aspects of brain physiology including neuronal morphology, glial cell function, neurotransmitter release, and synaptic function, in a context-specific manner. Many of these classical immune proteins, in fact, have known functions in neuronal development, synaptic remodeling and differentiation, in addition to their roles as immune mediators (Miller and Gauthier, 2007; Morimoto and Nakajima, 2019). An increase in levels of peripheral proinflammatory markers is often associated with neurodevelopmental disorders such as autism (Siniscalco et al., 2018), schizophrenia (Khandaker et al., 2015) and RTT (Pecorelli et al., 2020). These systemic alterations in inflammation may in part explain the eventual multi-organ pathophysiology of RTT. A review of transcription studies in mouse models of Mecp2 dysfunction identified gene expression changes in inflammation mediators across multiple cell types, including neurons, astrocytes, and microglia (Sanfeliu et al., 2019). Based on our survey of proteomic studies, select acute phase response proteins (APRs), key cytokines interleukins 6, 8, 37 (IL6, IL8, IL37), tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα), and the Nuclear Factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NFκB) pathway are highly associated with MeCP2 dysfunction. The majority of human studies we discuss were done using peripheral samples including plasma, serum and saliva; however, wherever possible we highlight any relevant findings in the CNS.

4.2.1. Cytokines and NFκB

Based on a recent review of immune dysfunction in Rett syndrome (Pecorelli et al., 2020), three pro-inflammatory cytokines- IL8, IL6, and TNFα are observed to be the most frequently altered in peripheral samples of patients. Our review of proteomic changes revealed a similar trend with the addition of the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL37 to this group. Each of these cytokines plays unique roles in brain physiology that encompass neuronal growth, neurotransmission, cell survival, and protection against inflammation (Araujo and Cotman, 1993; Ren et al., 2020; Willis et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2019). Tnfα mRNA is increased across the Mecp2-null brain (Kishi et al., 2016), and both TNFα mRNA (Cronk et al., 2015) and protein (Nance et al., 2017) are increased in Mecp2-null mice microglia. Lower levels of lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-mediated IL6 release and a trend for decreased TNFα are seen in conditioned media collected from murine Mecp2-null astrocytes compared to wildtype (Maezawa et al., 2009). TNFα and IL6 mRNA are also upregulated in LPS-induced human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) with mutated MECP2 expression, and splenocytes isolated from Mecp2-null mice (O’Driscoll et al., 2015). TNFα protein levels increase in LPS treated MECP2 deficient human monocytic THP1 cells, while treatment with a TNFα neutralizing antibody lowered levels of TNFα and IL6 mRNA in MECP2-deficient THP1 cells compared to those that were untreated. These findings suggest that disruptions of TNFα and IL6, at both the mRNA and protein levels, are associated with MeCP2 dysfunction in both the CNS and peripheral systems.

MECP2 may regulate these cytokines directly. MECP2 has been shown to bind a distal site in the coding region of TNFα, suggesting a chromatin level-based regulation of this cytokine (O’Driscoll et al., 2015). Also, MECP2 and H3meK9 bind to a site on an IL6 upstream region in human pancreatic adenocarcinoma cells whose methylation status negatively correlated with IL6 gene expression, suggesting that MECP2 may regulate IL6 silencing (Dandrea et al., 2009). However, MECP2 might also regulate these cytokines via disrupted regulation of the NFκB signaling pathway. MECP2 deficient THP1 cells show enhanced binding of NFκB after LPS treatment by ChIP (O’Driscoll et al., 2015). NFκB inhibitor treatment blocked LPS-mediated upregulation of TNFα, IL6 and IL3 mRNA in MECP2 knockdown PBMCs, and TNFα, IL6 mRNA upregulation in MECP2 deficient THP1 cells. This shows that diminished MECP2 expression is associated with NFκB-mediated TNFα and IL6 mRNA upregulation. MECP2 modulates glutamatinase expression, a surrogate for glutamate release, through NFκB in PBMCs also (O’Driscoll et al., 2013). These data indicate that MECP2 can regulate levels of glutamate, IL6 and TNFα via NFκB signaling, as well as epigenetically regulate IL6 and TNFα expression.

Cortical astrocytes isolated from Mecp2308/y mice also show increased protein expression of several NFκB targets, although differences in NFκB binding activity were not detected (Delépine et al., 2015). Further, the NFκB pathway is aberrantly upregulated in cortical neurons with Mecp2 loss-of-function (Kishi et al., 2016; Ribeiro et al., 2020). Upstream of NFκB pathway activation and translocation of the NF-κB transcription factor dimer to the nucleus, is the phosphorylation of the IκB kinase (IKKB) complex, which is regulated by the protein Interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase 1 (IRAK1) (van Loo and Beyaert, 2011). Multiple gene expression studies across the hypothalamus (Chahrour et al., 2008), cortex, midbrain, cerebellum (Urdinguio et al., 2008), and hippocampus have shown increased Irak1 expression in animal models of Mecp2 dysfunction. Our previous studies also found elevated cortical Irak1 expression in male Mecp2 null mice (Kishi et al., 2016) and female heterozygous mice (Ribeiro et al., 2020). Importantly, genetically attenuating NFκB signaling rescues the dendritic deficits seen in cortical callosal projection neurons, and enhances the normally shortened lifespan of Mecp2 null mice by approximately 50% (Kishi et al., 2016). These data indicate that aberrant NF-κB pathway activation plays a key role in the brain pathophysiology of RTT and could provide a viable therapeutic target.

In line with these findings, recent studies show that inhibiting NFκB signaling via the Glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK3β) pathway inhibitor SB216763 in Mecp2-null neurons reduced NFκB activation, reduced proinflammatory cytokine protein expression, and rescued dendritic and spine deficits (Jorge-Torres et al., 2018). Together, these data indicate that targeting NFκB can have anti-inflammatory benefits and partially restore neuronal physiology. Overall, Mecp2 dysfunction leads to increased NFκB signaling, which can then disrupt the expression of a number of downstream target genes of NFκB. Alleviating these imbalances in NFκB can potentially restore homeostasis to the downstream inflammation and dysregulated expression of other target genes that have important roles in brain physiology.

4.2.2. Nitric oxide

Nitric oxide (NO) is a gaseous retrograde neurotransmitter that regulates immune response, neurotransmission, neuroprotection, and cell signaling. NO protects against infection-induced inflammation in both the CNS and periphery (Olivera et al., 2016), however excessive NO production in the brain, particularly by glial cells, can contribute to neuroinflammation and neurotoxicity [reviewed by (Ghasemi and Fatemi, 2014)]. Nitric oxide synthase (NOS) is the enzyme responsible for synthesis of NO from L-arginine. Endothelial (eNOS) and neuronal NOS (nNOS) regulate physiological NO levels (Joca et al., 2019), whereas inducible (iNOS) is often produced in response to inflammatory stimuli (Amitai, 2010). iNOS is subject to epigenetic control by DNA methylation and histone (H3K4Me3) modifications. ChIP studies show that MECP2 binds to the iNOS promoter in human endothelial cells (Chan et al., 2005). This suggests that MECP2 may normally repress iNOS gene expression and MECP2 dysfunction in RTT may lead to excessive NO production due to elevated iNOS levels. In fact, Nos1 (neuronal) is one of the most significantly differentially expressed genes across 38 transcriptomic datasets from mouse models of RTT (Sanfeliu et al., 2019). At least two studies have shown that proteins associated with NO function are also altered with Mecp2 loss-of-function. These include increased dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase (DDAH) in Mecp2 null mouse cortex (Cortelazzo et al., 2020) – involved in NO generation, and increased NO production and elevated iNOS mRNA in fibroblasts of RTT patients (Pecorelli et al., 2016a). Furthermore, small intestine tissue from Mecp2-null mice show elevated neuronal NO synthase protein compared to wild type mice (Wahba et al., 2016), perhaps suggesting that excessive NO production in the gut contributes to the gastrointestinal disturbances seen in RTT patients.

4.3. Disruptions in the Vitamin D pathway

Our review of proteome disruptions in RTT identified changes in the expression of two key proteins in the vitamin D pathway, the vitamin D receptor Protein-disulfide isomerase-associated 3 (PDIA3) and the vitamin D binding protein (VTDB). Vitamin D receptors are either nuclear or membrane bound and play a key role in vitamin D signaling by initiating vitamin-D mediated transcriptional and cell signaling changes. PDIA3 is a vitamin D receptor that is localized to the cell membrane (Boyan et al., 2012); it is also a stress-response protein that functions as a chaperone (Wang et al., 2020). The other vitamin D receptor - VDR, exerts its genomic effects by interacting with the retinoid X receptor and bound vitamin D, migrating to the nucleus and binding to vitamin D response elements (VDRE) (Kato, 2000). This enables gene transcription/repression by vitamin D by the interaction of this complex with chromatin modifying proteins (Pike et al., 2012). PDIA3 acts in a non-genomic manner by interacting with vitamin D at the cell membrane and activating Protein Kinase C (PKC) signaling downstream to regulate biological function (Doroudi et al., 2012). At baseline, Vdr mRNA is highly abundant in rat astrocytes, liver and kidney while Pdia3 shows increased expression across different brain cells, including neurons, astrocytes, endothelial cells and low expression peripherally (Landel et al., 2018).

Our review of the literature revealed at least 2 studies showing increased PDIA3 protein expression in the context of Mecp2 dysfunction. The first study found that Mecp2-null mice had higher levels of PDIA3 compared to wildtype controls at 5 and 17 weeks in whole brain samples, which was rescued by brain-specific re-expression of Mecp2 (Cortelazzo et al., 2020). A separate study demonstrated that RTT patient fibroblasts express elevated PDIA3 protein levels in comparison to healthy controls (Pecorelli et al., 2016a). While the role of PDIA3 has not been studied in the context of RTT, recent studies show that PDIA3 functions go beyond protein folding, particularly in conditions of neurotrauma and neurodegeneration. Murine cortical Pdia3 mRNA and protein are induced in response to traumatic brain injury (TBI) in vivo (Wang et al., 2019). Following TBI, Pdia3−/− mice fail to induce an upregulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-6, TNF-α and IL-1β, exhibit reduced NFκB activation and increased levels of anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 in the ipsilateral cortex (Wang et al., 2019). These data suggest that PDIA3 is a key regulator of neuroprotection and neuroimmune response, both of which are impaired in RTT.

In contrast to PDIA3 protein, Pdia3 mRNA is downregulated in the hypothalamus of 6 week old Mecp2 null mice (Chahrour et al., 2008) and cortices of P60 Mecp2 Jae/y mice (Pacheco et al., 2017) compared to their respective wildtype controls. These data are in apparent opposition to the increased PDIA3 protein expression in Mecp2 null mice at 5 and 17 weeks of age in the cortex (Cortelazzo et al., 2020). This stark contrast between mRNA and protein data has been observed for a subset of genes in other Mecp2 studies (Delépine et al., 2015; Matarazzo and Ronnett, 2004). These changes may be explained by increased protein stability or posttranslational modifications of specific MeCP2 targets, requiring further investigation into their regulation by MeCP2.

VTDB is also altered in MeCP2 loss of function studies. VTDB binds and act as a carrier protein for 25(OH)-vitamin D and 1,25(OH)2-vitamin D, and regulates macrophage activation (Yamamoto and Homma, 1991) and actin polymerization (Van Baelen et al., 1980). Plasma VTDB levels are decreased in both Mecp2 308 mice compared to wildtype mice (Cortelazzo et al., 2017a), as well as in RTT patients versus unaffected controls (De Felice et al., 2013); however, its role in RTT remains uncharacterized. Overall, dysregulation of both PDIA3 and VTDB in the vitamin D pathway in RTT needs to be investigated in further detail to fully understand how they contribute to RTT pathogenesis.

4.4. Neurotrophic factors altered in RTT: BDNF and IGF1

Brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) is a multifaceted protein that plays numerous roles in nervous system function including regulation of synaptic plasticity, neuronal growth, neuroprotection and neurotransmission. Over the last decade the role of BDNF in RTT has been studied extensively and is reviewed elsewhere (Katz, 2014; Li and Pozzo-Miller, 2014); thus we will only briefly discuss its role here. BDNF shows genetic association with RTT and specific polymorphisms in BDNF correlate with higher clinical severity (Zeev et al., 2009), ages of seizure (Nissenkorn et al., 2010; Zeev et al., 2009) and epilepsy onset (Nectoux et al., 2008) in RTT patients. Further, these Bdnf polymorphisms lead to altered hippocampal neuron morphology and synaptic transmission phenotypes in cultured neurons from Mecp2-null mice (Xu et al., 2017). Regulation of Bdnf by MeCP2 is highly complex and context-specific, however. MeCP2 binds to Bdnf promoter IV, inhibiting its expression; activity-dependent phosphorylation of MeCP2 releases this binding and promotes Bdnf transcription (Ballas et al., 2005; Chen et al., 2003). Release of MeCP2 may increase binding of transcriptional regulators like CREB (Li and Pozzo-Miller, 2014), which promote Bdnf transcription. However, in vitro studies show that Mecp2 overexpression in cortical neurons is associated with higher levels of Bdnf IV while Mecp2 knockout neurons show diminished Bdnf IV expression (Klein et al., 2007) which mirror findings of reduced BDNF mRNA and protein levels in human RTT embryonic stem cell-derived neurons (Li et al., 2013).

These findings have led to a possible “dual operation” model (Li and Pozzo-Miller, 2014), where MeCP2 phosphorylation and brain developmental stage determine its eventual effect on Bdnf expression. Interestingly, environmental enrichment using social, cognitive, sensory and motor based approaches in RTT patients leads to improved motor skills that correlate with peripheral BDNF levels (Downs et al., 2018). More recent studies suggest that MeCP2 regulates learning stimulus-specific splicing of Bdnf in ex vivo brainstem preparations of pond turtles (Zheng et al., 2017) indicating that activity-mediated neuronal stimulation and MeCP2 are critical regulators of Bdnf splicing. Although MeCP2-mediated regulation of Bdnf is extremely complex and context-specific, levels of BDNF decrease rapidly with onset of disease and neuropathology in Mecp2-null mice (Chang et al., 2006) and human RTT autopsy brain studies show reduced BDNF mRNA levels (Deng et al., 2007). Thus, several physiological and pharmacological approaches to rescue BDNF levels are being investigated in animal models as well as RTT patients. For example, the small molecule LM22A-4, a BDNF agonist, was shown to rescue hippocampal LTP and object-location memory in female Mecp2 heterozygous mice (Li et al., 2017).

Insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF1) is another major neurotrophic factor that regulates synaptic plasticity, dendritic growth, and neurotransmission. Plasma IGF1 levels are low in a subset of RTT patients (Huppke et al., 2001) and negatively correlate with head circumference (Hara et al., 2014). IGF is also decreased in the hippocampus of Mecp2-null mice (Schaevitz et al., 2010). Similar to BDNF, regulation of IGF1 by MECP2 occurs at multiple levels. Mecp2 knockdown elevates the LncRNA H19 in rat hepatic stellate cells, which represses expression of the IGF1 receptor (IGF1R) (Yang et al., 2016). Studies using the β2-adrenergic receptor agonist clenbuterol in Mecp2-null mice show MeCP2 represses the let7f miRNA, which downregulates IGF1 (Mellios et al., 2014). In totality, these findings suggest that MeCP2 is a crucial regulator of IGF1 expression, stability, and signaling. Therefore, modulating IGF1 in RTT holds great promise as a therapeutic approach. IGF1 treatment induces Mecp2 mRNA and increases levels of MeCP2 nuclear protein in cortical neurons (Tropea et al., 2016), and protects against MeCP2-e2 isoform mediated neurotoxicity in vitro (Dastidar et al., 2012). Treatment of Mecp2 mutant mice with recombinant IGF1 protein reverses behavioral and synaptic defects (Castro et al., 2014; Tropea et al., 2009). This, combined with promising in vitro data showing beneficial effects of IGF1 in RTT patient iPSc-derived neurons (de Souza et al., 2017; Williams et al., 2014) has led to numerous clinical trials targeting IGF1 (Katz et al., 2016; O’Leary et al., 2018). As one example, recombinant human IGF1 (Mecasermin) treatment correlated with marked improvements in disease severity, social and cognitive measures in RTT patients versus untreated patients (Pini et al., 2016).

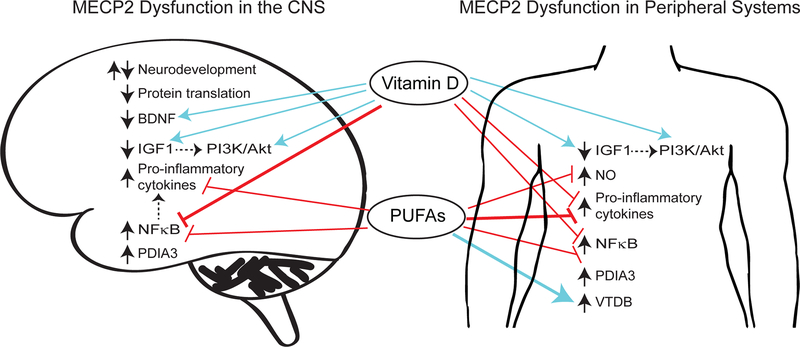

5. Modifying multiple cellular pathways via nutritional supplementation as a partial therapeutic intervention in RTT

There are numerous cellular pathways disrupted downstream of Mecp2 loss-of-function, proving a challenge to therapeutic treatments. Further, while RTT is a neurological disorder it also affects peripheral tissues including liver, kidneys, and heart because of the multiple biological pathways that are dysregulated. Most treatments currently under investigation target a single protein, pathway, or symptom of RTT. The most effective intervention, however, should target multiple pathways and mediate its beneficial effects both centrally and peripherally. Dietary supplements are emerging as a potential partial therapeutic approach because of their ease of administration, safety, absorption, and ability to exert their biological effects on multiple organ systems. They can positively regulate immune function, neurological function, cardiac function, bone growth, and antioxidant response. Both vitamin D and omega-3 fatty acids can modify multiple cellular pathways that are disrupted in RTT, and both have been previously shown to improve symptoms in Autism Spectrum Disorders and other neurological disorders (Infante et al., 2018; Jia et al., 2015; Mazahery et al., 2017; Saad et al., 2018, 2016). Based on these promising findings, we discuss biological actions of these two agents and their potential applications for RTT therapy (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Proposed mechanisms for rescue of disrupted proteome in Rett syndrome by Vitamin D and Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids (PUFAs).

MECP2 dysfunction is associated with increased (upward black arrow) or decreased (downward black arrow) expression of multiple proteins and cellular pathways in the central nervous system as well as peripheral organs and circulatory system (denoted by the term “periphery”) contributing to perturbations in physiological processes such as altered (up and down black arrows) neurodevelopment, and increased inflammation. These proteins include both direct targets of MECP2, and those that might be disrupted indirectly due to regulation by MECP2 targets (dashed arrows). Vitamin D and PUFAs have been shown to inhibit (red lines) or activate (blue arrows) several of these pathways in non-RTT studies, and to restore homeostasis to these pathways in RTT patients or Mecp2-mutant mouse models (weighted red lines and blue arrows). Vitamin D and PUFAs have tremendous potential to simultaneously rescue multiple disrupted pathways and provide a partial therapeutic for RTT.

5.1. Polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs)

Polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) are essential fatty acids that are acquired only through dietary sources. The shorter chain version of PUFAs – eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoicacid (DHA), found mostly in oily fish, are known as omega-3 PUFA (ω−3 PUFA). ω−3 PUFAs have a well-demonstrated anti-inflammatory mode of action including decreasing NFκB activation (Nakanishi and Tsukamoto, 2015), and suppressing pro-inflammatory gene expression in monocytes (Zhao et al., 2005). PUFAs have been shown to be beneficial in some ADHD studies (Perera et al., 2012; Voigt et al., 2001) and in treatment of depressive symptoms in major depression (Jahangard et al., 2018; Nemets et al., 2002). PUFAs can decrease levels of NFκB in the brain and dampen inflammation in vivo (Peng et al., 2020). Several recent studies show that ω−3 PUFA supplementation may alter the immune imbalances seen in RTT patients, including reversing APR protein expression directionality (De Felice et al., 2013; Leoncini et al., 2015), and rescuing decreased VTDB expression (De Felice et al., 2013) and cytokine expression, including TNFα (Byiers et al., 2020) and IL-37 (Leoncini et al., 2015). In addition, data from two clinical trials suggest PUFA supplementation can decrease oxidative stress and enhance myocardial function in RTT (Maffei et al., 2014; Signorini et al., 2014).

Another study found 6 months of ω−3 PUFA fish oil supplementation in stage I RTT patients was associated with marked improvements in “sitting, ambulation, hands use, nonverbal communication, and respiratory dysfunction” (De Felice et al., 2012). The authors hypothesized that these effects may be attributed to rescue of white matter defects and decreasing oxidative stress that can impact lipid peroxidation and BDNF levels. Also, PUFA administration showed a trend for improving verbal communication in RTT patients (De Felice et al., 2012), however further studies are needed to examine its effects on cognition in RTT.

5.2. Vitamin D

Among their many symptoms, RTT patients often exhibit low bone mineral density and are highly susceptible to fractures (Jefferson et al., 2011). Vitamin D is involved in regulation of calcium absorption and maintaining normal bone health (Moreno et al., 2012). Multiple studies show that vitamin D levels are low in blood samples from RTT patients (Motil et al., 2011; Sarajlija et al., 2013) and RTT patients may be prescribed vitamin D supplementation to aid bone health (Wiedemann et al., 2019). Vitamin D is neuroprotective (Brewer et al., 2001; Wang et al., 2000), immunomodulatory (de Oliveira et al., 2020), and regulates memory (Saad El-Din et al., 2020), suggesting it plays a role in multiple aspects of brain physiology, in addition to bone health. Interestingly, our recent studies found that Mecp2-null mice similarly have significantly reduced levels of circulating vitamin D (Ribeiro et al., 2020), suggesting that this deficiency is not simply a result of diet or environmental exposure.

Considering that vitamin D deficits are common in RTT, proteins within the vitamin D pathway are dysregulated in the disorder, and vitamin D has many known beneficial effects, it could serve as a useful partial therapeutic agent in RTT. Our recent findings, in fact, demonstrate that dietary vitamin D supplementation in Mecp2-mutant mice ameliorates the reduced dendritic complexity and soma size phenotypes in both hemizygous Mecp2-null males and heterozygous females, and it modestly improves the phenotype progression and reduced lifespan of Mecp2-null males (Ribeiro et al., 2020). Vitamin D is known to inhibit the NFκB pathway in different cell types (Cohen-Lahav et al., 2006; Harant et al., 1998; Riis et al., 2004). Given our previous studies demonstrating beneficial effects of dampening NFκB on neuronal morphology and lifespan in Mecp2 null mice (Kishi et al., 2016), we hypothesize that the therapeutic benefit of vitamin D may be attributed to its anti-inflammatory and anti-NFκB action. In vitro studies demonstrate that vitamin D does, indeed, rescue the aberrant NF-κB activation that occurs with Mecp2 knockdown in cortical neurons (Ribeiro et al., 2020). Vitamin D supplementation in rats has also been shown to decrease total NFκB protein levels and reverse cognitive deficits induced by high fat diet (Hajiluian et al., 2017), and to protect against LPS-mediated cognitive impairment and to decrease levels of the proinflammatory cytokine IL6 (Mokhtari-Zaer et al., 2020). Vitamin D also upregulates anti-inflammatory IL-10 (Guillot et al., 2010), represses IL8 promoter activity, and decreases NFκB binding to the IL8 promoter (Harant et al., 1997), providing further support for the use of vitamin D to counter the increased NF-κB pathway activation and inflammation observed in RTT.

The beneficial effects of vitamin D supplementation in RTT may additionally be attributed to its regulation of growth factor signaling, including BDNF and IGF. Vitamin D supplementation rescues age-related BDNF deficits in brains of rats (Khairy and Attia, 2019) and increases BDNF levels in the hippocampus of rats fed on a high fat diet compared to a control diet, along with reducing total NFκB levels (Hajiluian et al., 2017). As discussed previously, rescuing the reduced BDNF levels significantly improves RTT pathophysiology. Another well studied therapeutic target in RTT is the growth factor IGF1. A recent meta-analysis of eight clinical studies spanning different disorders showed that vitamin D supplementation increases levels of IGF1 in subjects aged 60 years or less (Kord-Varkaneh et al., 2020). Vdr knockout mice have decreased levels of plasma IGF1 compared to wildtype mice (Song et al., 2003), suggesting that IGF1 may be modulated by vitamin D. IGF1 treatment in Mecp2-null mice activates the Phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K/Akt) pathway, leading to improvements in synaptic function (Castro et al., 2014). Vitamin D treatment in hypothalamic cell cultures has also been found to increase insulin-mediated activation of the PI3K/Akt pathway, and enhance neuronal firing (da Silva Teixeira et al., 2020). Thus, vitamin D could rescue neuronal function both by upregulating IGF1 levels directly as well as by activating the downstream PI3K/Akt pathway. Overall, vitamin D can target multiple pathways (BDNF, IGF1, PI3K/Akt, NFκB) that are dysregulated in RTT, suggesting it may compensate for MeCP2 dysfunction by modulating multiple cellular pathways in parallel. Further studies are needed to investigate the mechanisms by which vitamin D ameliorates Mecp2-mutant phenotypes in order to fully understand its potential as an effective partial therapeutic intervention in RTT.

6. Conclusions and Future Directions

At its core, RTT is a progressive neurodevelopmental disorder caused by loss of function mutations in the epigenetic regulator MECP2. Through this review, we have attempted to answer the question of how modifying one epigenetic regulator- MECP2, leads to the myriad of physiological disturbances seen in RTT. MECP2 mediates its effects primarily by altering gene transcription en masse. In addition, MeCP2 binds to histones, spliceosome proteins and long non-coding RNAs suggesting an ability to modify chromatin structure by interacting with these different entities (Maxwell et al., 2013). MeCP2 also mediates cell-autonomous and non-autonomous effects in the nervous system (Ribeiro and MacDonald, 2020), contributing to pathogenesis and cell-type specific effects on gene expression of important physiological mediators such as neurotrophic factors. Several MECP2 target, such as NO and IGF1, seem to have dose-dependent effects similar to MECP2, where too much or too little can have equally devastating effects on normal cellular function. All of these effects explain the vast impact of MECP2 dysfunction on innumerable biological processes in the brain including neurodevelopment, neural morphology and function, oligodendrocyte myelination, astrocyte function, and neuroinflammation.

CNS-specific Mecp2 loss-of-function in mice recapitulates most phenotypes observed in total loss-of-function mice (Guy et al., 2001; Tudor et al., 2002), highlighting the enhanced vulnerability of the brain to disruptions in epigenetic regulation, and its exquisite requirement for precise regulation. However, additional disruptions in peripheral systems are also observed and are important not only as biomarkers of the disorder, but also contribute to the extensive phenotypes of RTT. For example, a recent study by Orefice et al (Orefice et al., 2019) showed rescue of Gamma aminobutyric acid (GABAergic) signaling deficits specifically in peripheral sensory neurons ameliorates tactile sensitivity, social deficits, and anxiety-like behavior in Mecp2 mutant mice. This suggests that targeting the peripheral symptoms of RTT may resolve some of the CNS deficits, emphasizing the cross talk and common downstream targets of MeCP2 between the two. Biochemical pathways that play key roles in both central and peripheral function, such as cholesterol metabolism, are perturbed in the brains and livers of Mecp2 mouse models (Buchovecky et al., 2013), and RTT patient plasma samples and fibroblasts (Segatto et al., 2014). Interestingly, a recent mutagenesis screen to identify suppressor mutations in genes that ameliorate phenotypes in Mecp2-null mice found that a mouse line that carried nonsense mutations in the cholesterol metabolism protein encoding gene Squalene monooxygenase (Sqle), rescues the disrupted lipid metabolism in Mecp2-null mice and improves their symptoms (Buchovecky et al., 2013). Further, mice that additionally have mutations in a DNA damage response gene RB binding protein 8, endonuclease (Rbbp8) show a synergistic effect in enhancing longevity in Mecp2-null mice (Enikanolaiye et al., 2020). These data reinforce the idea of targeting multiple cellular pathways to resolve the effects of Mecp2 dysfunction.

Rescuing MECP2 dysfunction by re-expressing Mecp2 in the mouse brain can resolve many symptoms of RTT (Guy et al., 2007) and reverse expression of a subset of protein targets (Cortelazzo et al., 2020), opening up greater possibility for therapeutic intervention even at highly symptomatic stages. Although approaches such as exogenous re-expression of MECP2 or reactivation of the silenced allele of MECP2 offer great hope for a cure for RTT, there are many challenges to their development and application in humans. It may be significantly more feasible, at least in the short term, to use therapeutic interventions that can target identified biochemical pathways that are associated with MECP2 loss of function and that have already been approved for therapeutic use. For example, a recent study used existing FDA-approved small molecule inhibitors to target KCC2- a K Cl cotransporter that is altered across neurons from RTT human and in vivo Mecp2 mutant mouse studies. Tang et al showed that targeting KCC2 not only rescues neuronal morphology defects in vitro, but also reverses apnea and locomotion defects in RTT mouse models (Tang et al., 2019).

As outlined in this review, numerous transcriptome and proteome studies make it clear that there are many disrupted cellular pathways that additively contribute to RTT phenotypes. Thus, treating RTT will likely require a combinatorial approach, targeting nodes within the interactomes of these pathways. We have discussed vitamin D and PUFAs as possible partial therapeutic interventions due to their demonstrated utility in RTT and their ability to target multiple physiological processes simultaneously (Figure 2). Further unravelling the complex molecular alterations induced by MECP2 loss-of-function and contextualizing them at the level of proteome homeostasis will identify new therapeutic avenues for this complex disorder. We excitedly anticipate future studies that take into account these multi-layered functional aspects of MECP2.

Supplementary Material

Highlights:

Rett syndrome is a complex neurological disorder caused by mutations in MECP2

MECP2 is an epigenetic regulator that causes widespread transcriptional changes

MECP2 loss-of-function associated proteome disruptions are relatively understudied

Proteome disruptions converge on multiple cellular and biochemical pathways

Vitamin D can restore homeostasis to several disrupted pathways simultaneously

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Nikolaus Wagner, Mayara Ribeiro and Lorelle Parker for their helpful feedback and suggestions. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health [Grant number 1R01NS106285], and the International Rett Syndrome Foundation [Grant number 3064] awarded to JLM.

List of Abbreviations:

- CNS

Central nervous system

- RTT

Rett syndrome

- MBD

Methyl-CpG-binding domain

- TRD

Transcriptional repression domain

- NID

NCOR-SMRT interaction domain

- 5hmC

5 hydroxymethylcytosine

- iPSC

Induced pluripotent stem cell

- NPC

Neural progenitor cell

- ChIP

Chromatin immunoprecipitation

- TRAP seq

Translating ribosome affinity purification sequencing

Footnotes

Declaration of interests

☒ The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References:

- Amir RE, Van Den Veyver IB, Wan M, Tran CQ, Francke U, Zoghbi HY, 1999. Rett syndrome is caused by mutations in X-linked MECP2, encoding methyl- CpG-binding protein 2. Nat. Genet 10.1038/13810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amitai Y, 2010. Physiologic role for “Inducible” nitric oxide synthase: A new form of astrocytic-neuronal interface. Glia 58, 1775–1781. 10.1002/glia.21057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araujo DM, Cotman CW, 1993. Trophic effects of interleukin-4, −7 and −8 on hippocampal neuronal cultures: potential involvement of glial-derived factors. Brain Res 600, 49–55. 10.1016/0006-8993(93)90400-H [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ausió J, de Paz A.M. artíne., Esteller M, 2014. MeCP2: the long trip from a chromatin protein to neurological disorders. Trends Mol. Med 10.1016/j.molmed.2014.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker SA, Chen L, Wilkins AD, Yu P, Lichtarge O, Zoghbi HY, 2013. An AT-hook domain in MeCP2 determines the clinical course of Rett syndrome and related disorders. Cell. 10.1016/j.cell.2013.01.038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balakrishnan S, Mironov SL, 2018. CA1 Neurons Acquire Rett Syndrome Phenotype After Brief Activation of Glutamatergic Receptors: Specific Role of mGluR1/5. Front. Cell. Neurosci 10.3389/fncel.2018.00363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballas N, Grunseich C, Lu DD, Speh JC, Mandel G, 2005. REST and its corepressors mediate plasticity of neuronal gene chromatin throughout neurogenesis. Cell 121. 10.1016/j.cell.2005.03.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedogni F, Gigli CC, Pozzi D, Rossi RL, Scaramuzza L, Rossetti G, Pagani M, Kilstrup-Nielsen C, Matteoli M, Landsberger N, 2016. Defects during Mecp2 Null Embryonic Cortex Development Precede the Onset of Overt Neurological Symptoms. Cereb. Cortex 26. 10.1093/cercor/bhv078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellini E, Pavesi G, Barbiero I, Bergo A, Chandola C, Nawaz MS, Rusconi L, Stefanelli G, Strollo M, Valente MM, Kilstrup-Nielsen C, Landsberger N, 2014. MeCP2 post-translational modifications: A mechanism to control its involvement in synaptic plasticity and homeostasis? Front. Cell. Neurosci 10.3389/fncel.2014.00236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boban S, Leonard H, Wong K, Wilson A, Downs J, 2018. Sleep disturbances in Rett syndrome: Impact and management including use of sleep hygiene practices. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part A 10.1002/ajmg.a.38829 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borg I, Freude K, Kübart S, Hoffmann K, Menzel C, Laccone F, Firth H, Ferguson-Smith MA, Tommerup N, Ropers HH, Sargan D, Kalscheuer VM, 2005. Disruption of Netrin G1 by a balanced chromosome translocation in a girl with Rett syndrome. Eur. J. Hum. Genet 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyan BD, Chen J, Schwartz Z, 2012. Mechanism of Pdia3-dependent 1α,25-dihydroxy vitamin D3 signaling in musculoskeletal cells, in: Steroids. 10.1016/j.steroids.2012.04.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewer LD, Thibault V, Chen KC, Langub MC, Landfield PW, Porter NM, 2001. Vitamin D hormone confers neuroprotection in parallel with downregulation of L-type calcium channel expression in hippocampal neurons. J. Neurosci 10.1523/jneurosci.21-01-00098.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchovecky CM, Turley SD, Brown HM, Kyle SM, McDonald JG, Liu B, Pieper AA, Huang W, Katz DM, Russell DW, Shendure J, Justice MJ, 2013. A suppressor screen in Mecp2 mutant mice implicates cholesterol metabolism in Rett syndrome. Nat. Genet 45. 10.1038/ng.2714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byiers BJ, Merbler AM, Barney CC, Frenn KA, Panoskaltsis-Mortari A, Ehrhardt MJ, Feyma TJ, Beisang AA, Symons F, 2020. Evidence of altered salivary cytokine concentrations in Rett syndrome and associations with clinical severity. Brain, Behav. Immun. - Heal 10.1016/j.bbih.2019.100008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro J, Garcia RI, Kwok S, Banerjee A, Petravicz J, Woodson J, Mellios N, Tropea D, Sur M, 2014. Functional recovery with recombinant human IGF1 treatment in a mouse model of Rett Syndrome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 10.1073/pnas.1311685111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chahrour M, Sung YJ, Shaw C, Zhou X, Wong STC, Qin J, Zoghbi HY, 2008. MeCP2, a key contributor to neurological disease, activates and represses transcription. Science (80-. ). 10.1126/science.1153252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chahrour M, Zoghbi HY, 2007. The Story of Rett Syndrome: From Clinic to Neurobiology. Neuron. 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan GC, Fish JE, Mawji IA, Leung DD, Rachlis AC, Marsden PA, 2005. Epigenetic Basis for the Transcriptional Hyporesponsiveness of the Human Inducible Nitric Oxide Synthase Gene in Vascular Endothelial Cells. J. Immunol 10.4049/jimmunol.175.6.3846 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang Q, Khare G, Dani V, Nelson S, Jaenisch R, 2006. The disease progression of Mecp2 mutant mice is affected by the level of BDNF expression. Neuron. 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.12.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Chen K, Lavery LA, Baker SA, Shaw CA, Li W, Zoghbi HY, 2015. MeCP2 binds to non-CG methylated DNA as neurons mature, influencing transcription and the timing of onset for Rett syndrome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 10.1073/pnas.1505909112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen RZ, Akbarian S, Tudor M, Jaenisch R, 2001. Deficiency of methyl-CpG binding protein-2 in CNS neurons results in a Rett-like phenotype in mice. Nat. Genet 27. 10.1038/85906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen WG, Chang Q, Lin Y, Meissner A, West AE, Griffith EC, Jaenisch R, Greenberg ME, 2003. Derepression of BDNF Transcription Involves Calcium-Dependent Phosphorylation of MeCP2. Science (80-. ). 302, 885–889. 10.1126/science.1086446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng TL, Wang Z, Liao Q, Zhu Y, Zhou WH, Xu W, Qiu Z, 2014. MeCP2 Suppresses Nuclear MicroRNA Processing and Dendritic Growth by Regulating the DGCR8/Drosha Complex. Dev. Cell 28, 547–560. 10.1016/j.devcel.2014.01.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Gabel HW, Hemberg M, Hutchinson AN, Sadacca LA, Ebert DH, Harmin DA, Greenberg RS, Verdine VK, Zhou Z, Wetsel WC, West AE, Greenberg ME, 2011. Genome-Wide Activity-Dependent MeCP2 Phosphorylation Regulates Nervous System Development and Function. Neuron. Neuron 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.08.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen-Lahav M, Shany S, Tobvin D, Chaimovitz C, Douvdevani A, 2006. Vitamin D decreases NFκB activity by increasing IκBα levels. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant 10.1093/ndt/gfi254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connolly DR, Zhou Z, 2019. Genomic insights into MeCP2 function: A role for the maintenance of chromatin architecture. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol 10.1016/j.conb.2019.07.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooke DW, Naidu S, Plotnick L, Berkovitz GD, 1995. Abnormalities of thyroid function and glucose control in subjects with Rett syndrome. Horm. Res 10.1159/000184309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cortelazzo A, De Felice C, De Filippis B, Ricceri L, Laviola G, Leoncini S, Signorini C, Pescaglini M, Guerranti R, Timperio AM, Zolla L, Ciccoli L, Hayek J, 2017a. Persistent Unresolved Inflammation in the Mecp2–308 Female Mutated Mouse Model of Rett Syndrome. Mediators Inflamm 10.1155/2017/9467819 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cortelazzo A, De Felice C, Guerranti R, Signorini C, Leoncini S, Pecorelli A, Zollo G, Landi C, Valacchi G, Ciccoli L, Bini L, Hayek J, 2014. Subclinical inflammatory status in Rett syndrome. Mediators Inflamm. 2014. 10.1155/2014/480980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cortelazzo A, De Felice C, Guy J, Timperio AM, Zolla L, Guerranti R, Leoncini S, Signorini C, Durand T, Hayek J, 2020. Brain protein changes in Mecp2 mouse mutant models: Effects on disease progression of Mecp2 brain specific gene reactivation. J. Proteomics 10.1016/j.jprot.2019.103537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cortelazzo A, de Felice C, Leoncini S, Signorini C, Guerranti R, Leoncini R, Armini A, Bini L, Ciccoli L, Hayek J, 2017b. Inflammatory protein response in CDKL5-Rett syndrome: evidence of a subclinical smouldering inflammation. Inflamm. Res 10.1007/s00011-016-1014-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cortelazzo A, Guerranti R, De Felice C, Signorini C, Leoncini S, Pecorelli A, Landi C, Bini L, Montomoli B, Sticozzi C, Ciccoli L, Valacchi G, Hayek J, 2013. A plasma proteomic approach in rett syndrome: Classical versus preserved speech variant. Mediators Inflamm. 10.1155/2013/438653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cronk JC, Derecki NC, Ji E, Xu Y, Lampano AE, Smirnov I, Baker W, Norris GT, Marin I, Coddington N, Wolf Y, Turner SD, Aderem A, Klibanov AL, Harris TH, Jung S, Litvak V, Kipnis J, 2015. Methyl-CpG Binding Protein 2 Regulates Microglia and Macrophage Gene Expression in Response to Inflammatory Stimuli. Immunity. 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.03.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- da Silva Teixeira S, Harrison K, Uzodike M, Rajapakshe K, Coarfa C, He Y, Xu Y, Sisley S, 2020. Vitamin D actions in neurons require the PI3K pathway for both enhancing insulin signaling and rapid depolarizing effects. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol 200. 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2020.105690 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dandrea M, Donadelli M, Costanzo C, Scarpa A, Palmieri M, 2009. MeCP2/H3meK9 are involved in IL-6 gene silencing in pancreatic adenocarcinoma cell lines. Nucleic Acids Res. 10.1093/nar/gkp723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]