Abstract

Background/Aim: The anticipation of radiotherapy can cause distress and sleep disorders, which may be aggravated by the COVID-19 pandemic. This study investigated sleep disorders in a large cohort of patients with breast cancer before and during the pandemic. Patients and Methods: Twenty-three characteristics were retrospectively analyzed for associations with pre-radiotherapy sleep disorders in 338 patients. Moreover, 163 patients presenting before and 175 patients presenting during the COVID-19 pandemic were compared for sleep disorders. Results: Sleep disorders were significantly associated with age ≤60 years (p=0.006); high distress score (p<0.0001); more emotional (p<0.0001), physical (p<0.0001) or practical (p<0.0001) problems; psycho-oncological need (p<0.0001); invasive cancer (p=0.003); chemotherapy (p<0.001); and hormonal therapy (p=0.006). Sleep disorders were similarly common in both groups (prior to vs. during the pandemic: 40% vs. 45%, p=0.38). Conclusion: Although additional significant risk factors for sleep disorders were identified, the COVID-19 pandemic appeared to have no significant impact on sleep disorders in patients scheduled for irradiation of breast cancer.

Keywords: COVID-19 pandemic, pre-radiotherapy sleep disorders, breast cancer, prevalence, risk factors

Breast cancer is one of the most common cancer types worldwide (1). In the vast majority of patients with primary breast cancer, the treatment regimen includes adjuvant radiotherapy (2). Being scheduled for radiotherapy can cause significant distress for patients, which may be associated with sleep disorders. According to previous studies, sleep disorders are quite common in patients with breast cancer (3,4).

Controversy exists regarding the point in time during a patient’s course when sleep orders are most prevalent. In a study that investigated sleeping habits in 33 patients with breast cancer and 23 with prostate cancer during a course of radiotherapy plus 6-month follow-up, sleep disorders occurred mainly before and at the beginning of the treatment (5). In a population-based epidemiological study including 465 patients with breast cancer and 263 with prostate cancer, sleep disorders increased during the period of treatment due to radiation-related side-effects (6). To date, only a few studies have investigated the prevalence of pre-radiotherapy sleep disorders and corresponding risk factors (4,7,8). Therefore, a major goal of the current study was the identification of additional risk factors for pre-radiotherapy sleep disorders in a large cohort of patients with primary breast cancer.

Distress and pre-radiotherapy sleep disorders may be aggravated by the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. The majority of patients with cancer belong to the high-risk group because of immuno-suppression due to malignant disease or anticancer treatment (9-12). The studies reported so far have provided conflicting results regarding the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on distress and sleep disorders in patients with cancer (13-17). No study has particularly focused on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the prevalence of sleep disorders before a course of radiotherapy. Therefore, an additional major goal of the current study was the investigation of a potential impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the prevalence of pre-radiotherapy sleep disorders in patients with breast cancer scheduled to receive radiotherapy after breast-conserving surgery or mastectomy.

Patients and Methods

In this retrospective study, data of 338 female patients assigned to external-beam irradiation for primary breast cancer following breast-conserving surgery or mastectomy were analyzed for pre-radiotherapy sleep disorders. The study received approval from the Ethics Committee of the University of Lübeck (reference number 21-178). All patients had completed a National Comprehensive Cancer Network Distress Thermometer evaluation (18). The entire cohort included 175 [previously reported (4)] patients who presented for irradiation between March 2020 and February 2021 (i.e. during the COVID-19 pandemic in Lübeck) and 163 patients who presented between March 2019 and February 2020 (i.e. prior to the COVID-19 pandemic in Lübeck).

Patients treated with breast-conserving surgery were assigned to whole-breast irradiation (40 Gy in 15 fractions over 3 weeks or 50.4 Gy in 28 fractions over 6.5 weeks) with or without a boost to the tumor bed (10 Gy in 5 fractions over 1 week) (2). Following mastectomy, patients with risk factors were assigned to irradiation of the chest wall, mainly with 50.4 Gy in 28 fractions over 6.5 weeks. The treatment volume included locoregional lymph nodes when more than three axillary lymph nodes were involved and with involvement of 1-3 axillary lymph nodes and specific risk factors (2).

Using the patient-reported outcomes from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network Distress Thermometer (18), patients were evaluated for sleep disorders (no vs. yes) at the time of the first contact with a radiation oncologist, generally 1-2 weeks before the start of treatment. Moreover, 18 characteristics were analyzed for associations with pre-radiotherapy sleep disorders in the entire cohort (Table I). These characteristics were age (≤60 vs. ≥61 years, median=60.5 years); Karnofsky performance score (90-100 vs. 60-80); Charlson comorbidity index (2 vs. ≥3, median=2); history of previous or concurrent breast cancer or ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) (no vs. yes); history of another previous or concurrent malignancy (no vs. yes); family history of malignant disease in general (no vs. yes); family history of breast cancer or DCIS (no vs. yes); history of previous radiation therapy (no vs. yes); distress score (0-4 vs. ≥5; median=4) according to the National Comprehensive Cancer Network Distress Thermometer (18); number of emotional (0-1 vs. ≥2, median=1), physical (0-3 vs. ≥4, median=3) or practical (0 vs. ≥1, median=0) problems according to the Distress Thermometer; request for psycho-oncological support (no vs. yes); tumor type (DCIS only vs. invasive breast cancer with/without DCIS); type of surgery (breast-conserving surgery vs. mastectomy); chemotherapy prior to radiotherapy (no vs. yes), hormonal therapy with tamoxifen or aromatase inhibitors started prior to radiotherapy (no vs. yes); and treatment volume of radiotherapy (with vs. without locoregional lymph nodes).

Table I. Patient and tumor characteristics of the entire cohort.

BCS: Breast-conserving surgery; DCIS: ductal carcinoma in situ; LN: lymph nodes; NST: no special type; RT: radiotherapy. *Invasive cancer only (n=305).

In the 305 patients with invasive breast cancer, six additional characteristics were investigated, namely primary tumor stage (T1-2 vs. T3-4), nodal stage (N0-N1mi vs. N1-3), distant metastasis (no vs. yes), histology (no special type=NST vs. other histology), histological grading (1-2 vs. 3) and triple negativity (no vs. yes). Moreover, the 175 patients who presented for irradiation during the COVID-19 pandemic were compared to those 163 patients who presented prior to the Covid-19 pandemic with respect to the prevalence of sleep disorders [yes vs. no according to the evaluation with the National Comprehensive Cancer Network Distress Thermometer (18)] and the other 23 investigated characteristics.

For statistical analyses regarding associations between the investigated characteristics and pre-radiotherapy sleep disorders, the chi-square test was used. When the number of patients in one subgroup was fewer than 5, the corresponding analysis was performed with Fisher’s exact test. For both tests, p-values of less than 0.05 indicated significance, and p-values of 0.05-0.08 were considered indicative of a trend.

Results

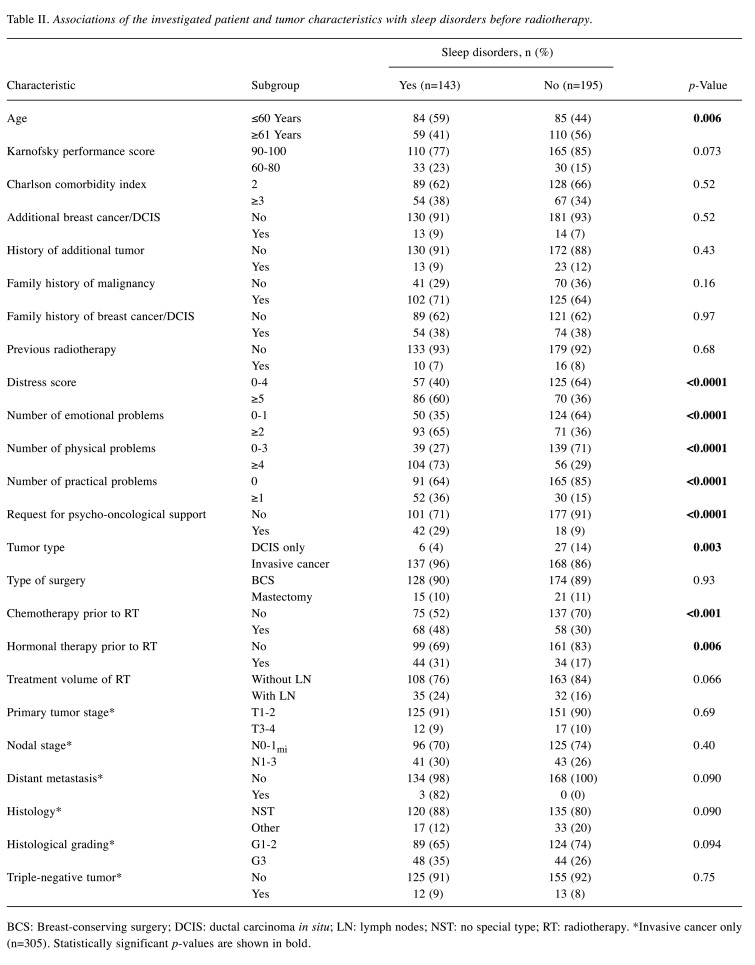

Considering the entire cohort, pre-radiotherapy sleep disorders were indicated by 143 of the 338 patients (42%). Sleep disorders were significantly associated with age ≤60 years (p=0.006), a distress score of ≥5 (p<0.0001), ≥2 emotional problems (p<0.0001), ≥4 physical problems (p<0.0001), practical problems (p<0.0001), request for psycho-oncological support (p<0.0001), invasive breast cancer (p=0.003), chemotherapy prior to radiotherapy (p<0.001) and hormonal therapy prior to radiotherapy (p=0.006) (Table II). Additionally, trends for being associated with sleep disorders were observed for a Karnofsky performance score of 60-80 (p=0.073), and radiotherapy including locoregional lymph nodes (p=0.066).

Table II. Associations of the investigated patient and tumor characteristics with sleep disorders before radiotherapy.

BCS: Breast-conserving surgery; DCIS: ductal carcinoma in situ; LN: lymph nodes; NST: no special type; RT: radiotherapy. *Invasive cancer only (n=305). Statistically significant p-values are shown in bold.

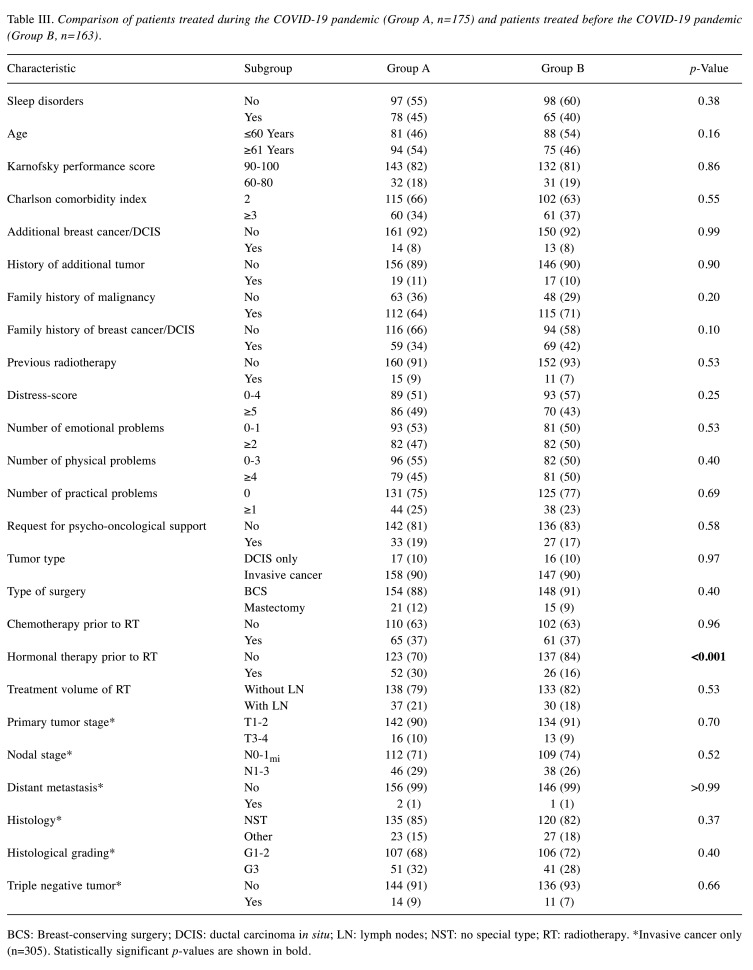

The comparison of the patients who presented during the COVID-19 pandemic and those who presented prior to the pandemic with respect to the prevalence of sleep disorders did not significantly differ (p=0.38). In those who presented during the pandemic, significantly more patients received hormonal therapy prior to radiotherapy (p<0.001). Otherwise, the distributions of the investigated characteristics were not significantly different between the groups (Table III).

Table III. Comparison of patients treated during the COVID-19 pandemic (Group A, n=175) and patients treated before the COVID-19 pandemic (Group B, n=163).

BCS: Breast-conserving surgery; DCIS: ductal carcinoma in situ; LN: lymph nodes; NST: no special type; RT: radiotherapy. *Invasive cancer only (n=305). Statistically significant p-values are shown in bold.

Discussion

Treatment protocols of patients with primary breast cancer most often include radiotherapy following breast-conserving surgery or mastectomy (2). Radiotherapy for breast cancer can be associated with acute and late toxicities (19-21). Being scheduled for radiotherapy may cause psychological distress that can lead to significant sleep disorders. Patients with breast cancer appear to be at a higher risk of being affected by sleep disorders than patients with other malignancies such as prostate cancer, as reported in a study from the University of California in Los Angeles (3). Prevalence and level of sleep disorders were significantly higher in the breast cancer group. Moreover, in a post-hoc analysis of 823 patients with cancer from a randomized trial, those with breast cancer reported the highest number of sleep problems when compared to patients with other cancer types (22).

Another important question is whether sleep disorders increase or decrease during a course of treatment. In the study of Savard et al., the concurrent effect of chemotherapy on insomnia was significantly mediated by treatment-related side-effects in the group of patients with breast cancer (6). The effect of radiotherapy on insomnia was also significantly mediated by side-effects, namely by dyspnea and night sweats. Night sweats represent an uncommon side-effect of local radiotherapy of breast cancer and appear to be caused primarily by simultaneous hormonal therapy. Moreover, the risk of radiation-related toxicity can be reduced with modern high-precision techniques. Thus, the impact of side-effects of radiotherapy on sleep disorders may currently be less pronounced than stated by Savard et al. in 2015 (6). The effect that patients appear to become used to irradiation during treatment may be relevant and lead to improvement of sleep disorders. This assumption is supported by the findings of a study that investigated sleep problems during and after a course of radiation therapy in patients with breast or prostate cancer who had been recruited for a study investigating fatigue and immune changes (5). Patients experienced a higher frequency of sleep problems prior to and during the initial phase of treatment.

Very few data are available regarding sleep disorders of patients with breast cancer before and during radiation treatment. In a previous study, the prevalence of pre-radiotherapy sleep disorders was 48% (7). In the entire cohort of the present study (n=338), the corresponding prevalence was 42%. This cohort included 175 previously reported patients, in whom the prevalence was 45% (4). In the. previous report, occurrence of sleep disorders was significantly associated with higher distress scores, psycho-oncological need, and greater numbers of emotional, physical or practical problems. Moreover, trends were observed for associations between sleep disorders and lower Karnofsky performance score or higher Charlson Comorbidity Index (4). The current study confirmed the results regarding the significant factors and the Karnofsky performance score, except for the Charlson Comorbidity Index. This may be explained by the fact that in the current study, the median score of the comorbidity index (2 points) was chosen as a cut-off, whereas in the previous study the cut-off was set at 3 points. In addition to the factors that were significant or showed a trend in the previous study, the present larger study identified additional factors associated with pre-radiotherapy sleep disorders. These factors included younger age (≤60 years), invasive breast cancer, chemotherapy prior to radiotherapy and hormonal therapy started prior to radiotherapy. Younger age (<58 years) has been described as being significantly associated with sleep disorders in a post-hoc analysis of a randomized trial including patients with different primary tumor types (breast cancer accounting for 49%) receiving chemotherapy (22). Moreover, in a cross-sectional survey study of 413 patients with breast cancer receiving aromatase inhibitors, age showed a borderline trend for association with clinical insomnia (p=0.083) (23). Rates of clinical insomnia were 24% in patients younger than 55 years, 20% in patients aged 55-65 years and 13% in patients older than 65 years. In a survey of 125 patients with breast cancer of any stage from the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, patients reporting sleep problems had a median age of 51.3 years compared to 56.6 years in patients without sleep problems (p<0.10) (24). More recently, in a study from Ireland including 294 patients with different cancer types (37% patients with breast cancer), age <65 years was an independent predictor of insomnia (odds ratio=1.8, 95% confidence interval=1.1-3.4; p=0.03) (25).

Associations between chemotherapy and sleep disorders were also previously described. In a population-based epidemiological study including 465 patients with breast cancer and 263 with prostate cancer, chemotherapy and its side-effects contributed to more sleep disorders (6). In a study of 502 patients with newly diagnosed breast cancer, those patients who received chemotherapy tended to have a higher rate of sleep disorders at 1 year after diagnosis of breast cancer (26). In a study of 74 patients with breast cancer, 29% of the patients receiving adjuvant chemotherapy had a high insomnia severity index compared to 4.2% of the patients receiving adjuvant radiotherapy, 7.7% of the patients evaluated prior to any treatment and 0% in a control group without breast cancer (p=0.004) (27). Moreover, in a prospective observational study of 173 patients with non-metastatic breast cancer, chemotherapy (odds ratio=0.08, 95% confidence interval=0.02-0.29; p<0.001) was identified as a main risk factor for persistent insomnia (28). Conflicting data were reported regarding the impact of hormonal therapy on sleep disorders. In the prospective study of Nabieva et al., sleep disorders caused by letrozole led to discontinuation of the hormonal therapy in a significant number of post-menopausal patients with early-stage breast cancer (29). Similar results were reported from a cohort study including 100 patients with breast cancer receiving aromatase inhibitors and 200 women without cancer diagnosis (30). Treatment with aromatase inhibitors was associated with a significant increase in sleep problems. On the contrary, in the studies of Savard et al. (6) and Bhave et al. (31), no significant associations were found between hormonal therapy and insomnia or sleep quality.

Furthermore, invasive breast cancer (when compared to DCIS alone) was identified as risk factor for pre-radiotherapy sleep disorders in the present study. This factor was not described previously, possibly because only very few studies, including our preceding one, focused on pre-radiotherapy sleep disorders (4,7,8). However, since invasive cancer is associated with poorer prognoses than DCIS, the situation is likely more stressful for the affected patients. In addition, a greater treatment volume of radiotherapy showed a trend toward having an association with sleep disorders. An impact of the treatment volume on the occurrence of sleep disorders was not previously described. This finding can be explained by the fact that irradiation of a larger volume including locoregional lymph nodes can be associated with a higher risk of late toxicities such as lymphedema, arm paresis, lung fibrosis and coronary heart disease. Moreover, irradiation of lymph nodes is indicated only in cases of locoregionally advanced disease with a higher risk of locoregional recurrence. These factors likely lead to an increased level of distress often associated with sleep disorders.

The prevalence of psychological distress and sleep disorders may have increased during the COVID-19 pandemic. Therefore, the current study compared the prevalence of pre-radiotherapy sleep disorders in 175 patients with primary breast cancer who presented for radiotherapy during the COVID-19 pandemic to the prevalence in 163 presenting prior to the pandemic. The prevalence was slightly higher during the pandemic but the difference was not statistically significant (45 vs. 40%, p=0.38). Moreover, since a higher proportion of patients treated during the COVID-19 pandemic received hormonal therapy prior to the start of radiotherapy (due to a change of the treatment concept at our university hospital in 2020) and since this therapy was significantly associated with sleep disorders, the observed difference of 5% was likely a result of hormonal therapy. Thus, the diagnosis of breast cancer appeared to be more stressful for patients than the threat arising from the COVID-19 pandemic. This finding is consistent with two previous reports from Europe. A study from Denmark found remarkably low levels of distress and high levels of resilience in 40 Danish patients with cancer being under treatment or under follow-up during the COVID-19 pandemic (13). In a study from the United Kingdom including 144 participants (cancer patients and their supporting networks), the COVID-19 pandemic had no detrimental effect on the patients’ psychological well-being (14). On the contrary, the authors of a study from Turkey including 595 patients with cancer under active treatment stated that the pandemic may have increased anxiety and depression in their group (15). Moreover, in two larger studies from China focusing on patients with breast cancer, a high prevalence of depression, anxiety, distress and insomnia was observed (16,17). However, none of these previous studies was comparable to our present study, since they did not focus on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on pre-radiotherapy sleep disorders. When interpreting the results of the current study, the retrospective design and the possibility of a selection bias should be considered.

In summary, additional risk factors such as younger age, invasive breast cancer, chemotherapy or hormonal therapy prior to radiotherapy, and irradiation of locoregional lymph nodes were associated with pre-radiotherapy sleep disorders. The COVID-19 pandemic appears to have had no significant impact. The diagnosis of breast cancer appeared more detrimental to sleep than the pandemic.

Conflicts of Interest

The Authors report no conflicts of interest related to this study.

Authors’ Contributions

D.R., S.T. and T.W.K. participated in the design of the study. D.R. and C.A.N. collected the data which were analyzed by D.R. The article, which was drafted by D.R. and S.E.S., was reviewed and finally approved by all Authors.

Acknowledgements

As part of the project NorDigHealth, this study was funded by the European Regional Development Fund through the Interreg Deutschland-Danmark program.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2021. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(1):7–33. doi: 10.3322/caac.21654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leitlinienprogramm Onkologie (Deutsche Krebsgesellschaft, Deutsche Krebshilfe, AWMF): S3-Leitlinie Früherkennung, Diagnose, Therapie und Nachsorge des Mammakarzinoms, Version 4.3, 2020; AWMF Registernummer: 032-045OL. Available at: https://www.leitlinienprogramm-onkologie.de/leitlinien/mammakarzinom/ [Last accessed on May 21, 2021]

- 3.Garrett K, Dhruva A, Koetters T, West C, Paul SM, Dunn LB, Aouizerat BE, Cooper BA, Dodd M, Lee K, Wara W, Swift P, Miaskowski C. Differences in sleep disturbance and fatigue between patients with breast and prostate cancer at the initiation of radiation therapy. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2011;42(2):239–250. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2010.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rades D, Narvaez CA, Dziggel L, Tvilsted S, Kjaer TW. Sleep disorders in patients with breast cancer prior to a course of radiotherapy - prevalence and risk factors. Anticancer Res. 2021;41(5):2489–2494. doi: 10.21873/anticanres.15026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thomas KS, Bower J, Hoyt MA, Sepah S. Disrupted sleep in breast and prostate cancer patients undergoing radiation therapy: the role of coping processes. Psychooncology. 2010;19(7):767–776. doi: 10.1002/pon.1639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Savard J, Ivers H, Savard MH, Morin CM. Cancer treatments and their side effects are associated with aggravation of insomnia: Results of a longitudinal study. Cancer. 2015;121(10):1703–1711. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Savard J, Simard S, Blanchet J, Ivers H, Morin CM. Prevalence, clinical characteristics, and risk factors for insomnia in the context of breast cancer. Sleep. 2001;24(5):583–590. doi: 10.1093/sleep/24.5.583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dhruva A, Paul SM, Cooper BA, Lee K, West C, Aouizerat BE, Dunn LB, Swift PS, Wara W, Miaskowski C. A longitudinal study of measures of objective and subjective sleep disturbance in patients with breast cancer before, during, and after radiation therapy. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2012;44(2):215–228. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2011.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Savard J, Jobin-Théberge A, Massicotte V, Banville C. How did women with breast cancer experience the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic? A qualitative study. Support Care Cancer. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s00520-021-06089-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Al-Quteimat OM, Amer AM. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on cancer patients. Am J Clin Oncol. 2020;43(6):452–455. doi: 10.1097/COC.0000000000000712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang H, Zhang L. Risk of COVID-19 for patients with cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(4):e181. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30149-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liang W, Guan W, Chen R, Wang W, Li J, Xu K, Li C, Ai Q, Lu W, Liang H, Li S, He J. Cancer patients in SARS-CoV-2 infection: a nationwide analysis in China. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(3):335–337. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30096-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dieperink KB, Ikander T, Appiah S, Tolstrup LK. The cost of living with cancer during the second wave of COVID-19: A mixed methods study of Danish cancer patients’ perspectives. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2021;52:101958. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2021.101958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hulbert-Williams NJ, Leslie M, Hulbert-Williams L, Smith E, Howells L, Pinato DJ. Evaluating the impact of COVID-19 on supportive care needs, psychological distress and quality of life in UK cancer survivors and their support network. Eur J Cancer Care. 2021;(Engl):e13442. doi: 10.1111/ecc.13442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yildirim OA, Poyraz K, Erdur E. Depression and anxiety in cancer patients before and during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic: association with treatment delays. Qual Life Res. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s11136-021-02795-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen X, Wang L, Liu L, Jiang M, Wang W, Zhou X, Shao J. Factors associated with psychological distress among patients with breast cancer during the COVID-19 pandemic: a crosssectional study in Wuhan, China. Support Care Cancer. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s00520-021-05994-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Juanjuan L, Santa-Maria CA, Hongfang F, Lingcheng W, Pengcheng Z, Yuanbing X, Yuyan T, Zhongchun L, Bo D, Meng L, Qingfeng Y, Feng Y, Yi T, Shengrong S, Xingrui L, Chuang C. Patient-reported outcomes of patients with breast cancer during the COVID-19 outbreak in the epicenter of China: A cross-sectional survey study. Clin Breast Cancer. 2020;20(5):e651–e662. doi: 10.1016/j.clbc.2020.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Holland JC, Andersen B, Breitbart WS, Buchmann LO, Compas B, Deshields TL, Dudley MM, Fleishman S, Fulcher CD, Greenberg DB, Greiner CB, Handzo GF, Hoofring L, Hoover C, Jacobsen PB, Kvale E, Levy MH, Loscalzo MJ, McAllister-Black R, Mechanic KY, Palesh O, Pazar JP, Riba MB, Roper K, Valentine AD, Wagner LI, Zevon MA, McMillian NR, Freedman-Cass DA. Distress management. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2013;11(2):190–209. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2013.0027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tuohinen SS, Skytta T, Huhtala H, Virtanen V, Kellokumpu-Lehtinen PL, Raatikainen P. Left ventricular speckle tracking echocardiography changes among early-stage breast cancer patients three years after radiotherapy. Anticancer Res. 2019;39(8):4227–4236. doi: 10.21873/anticanres.13584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Werner EM, Eggert MC, Bohnet S, Rades D. Prevalence and characteristics of pneumonitis following irradiation of breast cancer. Anticancer Res. 2019;39(11):6355–6358. doi: 10.21873/anticanres.13847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gkantaifi A, Papadopoulos C, Spyropoulou D, Toumpourleka M, Iliadis G, Kardamakis D, Nikolaou M, Tsoukalas N, Kyrgias G, Tolia M. Breast radiotherapy and early adverse cardiac effects. The role of serum biomarkers and strain echocardiography. Anticancer Res. 2019;39(4):1667–1673. doi: 10.21873/anticanres.13272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Palesh OG, Roscoe JA, Mustian KM, Roth T, Savard J, Ancoli-Israel S, Heckler C, Purnell JQ, Janelsins MC, Morrow GR. Prevalence, demographics, and psychological associations of sleep disruption in patients with cancer: University of Rochester Cancer Center-Community Clinical Oncology Program. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(2):292–298. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.5011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Desai K, Mao JJ, Su I, Demichele A, Li Q, Xie SX, Gehrman PR. Prevalence and risk factors for insomnia among breast cancer patients on aromatase inhibitors. Support Care Cancer. 2013;21(1):43–51. doi: 10.1007/s00520-012-1490-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McFarland DC, Shaffer KM, Tiersten A, Holland J. Prevalence of physical problems detected by the distress thermometer and problem list in patients with breast cancer. Psychooncology. 2018;27(5):1394–1403. doi: 10.1002/pon.4631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harrold EC, Idris AF, Keegan NM, Corrigan L, Teo MY, O’Donnell M, Lim ST, Duff E, O’Donnell DM, Kennedy MJ, Sukor S, Grant C, Gallagher DG, Collier S, Kingston T, O’Dwyer AM, Cuffe S. Prevalence of insomnia in an oncology patient population: An Irish tertiary referral center experience. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2020;18(12):1623–1630. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2020.7611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fontes F, Pereira S, Costa AR, Gonçalves M, Lunet N. The impact of breast cancer treatments on sleep quality 1year after cancer diagnosis. Support Care Cancer. 2017;25(11):3529–3536. doi: 10.1007/s00520-017-3777-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tag Eldin ES, Younis SG, Aziz LMAE, Eldin AT, Erfan ST. Evaluation of sleep pattern disorders in breast cancer patients receiving adjuvant treatment (chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy) using polysomnography. J BUON. 2019;24(2):529–534. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fleming L, Randell K, Stewart E, Espie CA, Morrison DS, Lawless C, Paul J. Insomnia in breast cancer: a prospective observational study. Sleep. 2019;42(3):zsy245. doi: 10.1093/sleep/zsy245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nabieva N, Fehm T, Häberle L, de Waal J, Rezai M, Baier B, Baake G, Kolberg HC, Guggenberger M, Warm M, Harbeck N, Wuerstlein R, Deuker JU, Dall P, Richter B, Wachsmann G, Brucker C, Siebers JW, Popovic M, Kuhn T, Wolf C, Vollert HW, Breitbach GP, Janni W, Landthaler R, Kohls A, Rezek D, Noesselt T, Fischer G, Henschen S, Praetz T, Heyl V, Kühn T, Krauss T, Thomssen C, Hohn A, Tesch H, Mundhenke C, Hein A, Hack CC, Schmidt K, Belleville E, Brucker SY, Kümmel S, Beckmann MW, Wallwiener D, Hadji P, Fasching PA. Influence of side-effects on early therapy persistence with letrozole in post-menopausal patients with early breast cancer: Results of the prospective EvAluate-TM study. Eur J Cancer. 2018;96:82–90. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2018.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gallicchio L, MacDonald R, Wood B, Rushovich E, Helzlsouer KJ. Menopausal-type symptoms among breast cancer patients on aromatase inhibitor therapy. Climacteric. 2012;15(4):339–349. doi: 10.3109/13697137.2011.620658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bhave MA, Speth KA, Kidwell KM, Lyden A, Alsamarraie C, Murphy SL, Henry NL. Effect of aromatase inhibitor therapy on sleep and activity patterns in early-stage breast cancer. Clin Breast Cancer. 2018;18(2):168–174.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.clbc.2017.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]