Abstract

Background/Aim: S100A4 expression is associated with the pathology of chronic inflammatory diseases. In this study, we investigated the role of S100A4 and four inflammatory mediators (IL-1β, IĸB, IL-10, and TNF-α) in human periapical granulomas (PGs). Materials and Methods: S100A4 expression in PGs obtained by apicoectomy was examined by immunohistochemistry. Further, the expression of S100A4 and four inflammatory mediators was compared between PGs and healthy gingival tissues (HGTs) using real-time PCR. Results: In the PGs, S100A4 was found to be expressed in endothelial cells and fibroblasts. Furthermore, real-time PCR revealed that the expression of S100A4 and IL-1β in PGs was significantly higher than that in HGTs. Although a correlation between the expression of S100A4 and IĸB or IL-10 was not detected, a positive correlation between the expression of S100A4 and IL-1β or TNF-α was observed. Conclusion: The expression of S100A4 correlates with the pathogenesis of PGs.

Keywords: Apical periodontitis, endothelial cells, S100A4, inflammatory mediators, periapical granulomas, real-time polymerase chain reaction

Periapical granulomas (PGs), a type of refractory periapical periodontitis, arise in response to the presence of oral bacteria and their products (1,2). PGs are primarily characterised by chronic inflammation around the tooth apex, a phenomenon responsible for bone resorption and the manifestation of various clinical symptoms, resulting in a marked reduction in the quality of life of the patients (3). Treatment of apical periodontitis is to eliminate the source of root canal infection that causes lesions of apical periodontal tissue and has a high success rate (4). However, despite proper treatment by the dentist, apical periodontitis may not heal and tooth extraction may be required (4). Cytokines and growth factors play an important role in the development of periapical lesions and associated tissue damage (5). Notably, these inflammatory mediators increase lymphocyte activation, inflammatory cell migration, and osteoclast activation in the lesions (3,6-8). Although various studies have investigated the mechanisms underlying the development of periapical periodontitis (1-8), several details remain unclear. Thus, the elucidation of the pathology of apical periodontitis will be very useful for endodontic treatment.

Calcium-binding proteins S100 (termed S100 proteins) are low-molecular-weight proteins harbouring an EF-hand-type calcium-binding domain (9). The S100 protein family comprises 25 proteins and is expressed only in vertebrates (10,11). A member of the S100 protein family is known to be secreted by tumour cells and stromal cells, where S100 supports tumorigenesis by inducing angiogenesis (11,12). S100 proteins exhibit a cell-specific expression pattern and are involved in regulating processes, such as cell proliferation and differentiation, apoptosis, and inflammation (13). Furthermore, recent studies have reported S100 expression to be associated with chronic inflammatory diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis and Crohn’s disease, and that these proteins play a role in determining disease pathology (12,14-17). A prior study has shown that an S100 protein, S100A4, is involved in metastasis and is a major player in the transition from benign growth to malignancy (18). Additionally, it has been suggested that S100A4 plays an essential role in the induction of chronic inflammation (19).

In autoimmune diseases, the expression of interleukin-1β (IL-1β), tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), and interleukin-10 (IL-10) in mononuclear cells is associated with that of S100A4 (20-23). The binding of S100A4 to the receptor for advanced glycation end products activates nuclear factor-kappaB (NF-ĸB) and mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways, thereby promoting tumour cell invasion and survival (24). S100A4 also impairs osteoblast-mediated calcification, thereby inhibiting new bone formation and causing an imbalance in bone homeostasis (25). Via activating NF-ĸB, S100A4 interferes with the calcification function of osteoblasts, inhibits the formation of new bone, and causes an imbalance in bone homeostasis (25). Inhibitor of ĸB (IĸB), bound to the NF-ĸB dimer, is phosphorylated and degraded by the IĸB kinase (IKK) complex; as a result, NF-ĸB is activated and translocates to the nucleus (26-28). Additionally, S100A4 downregulation suppresses bone resorption in periodontal diseases (29-31). Hence, elucidating the pathophysiology of apical periodontitis may aid in the development of endodontic treatment for refractory periapical periodontitis.

Based on the role of S100A4 in periodontal diseases, we hypothesised that S100A4 is expressed in inflamed periapical tissues in humans and may be involved in the pathogenesis of PGs. The aim of this study was to compare the expression of S100A4 between inflammatory and healthy tissues in the oral cavity. The expression of S100A4 (at protein and mRNA levels) in PGs and healthy gingival tissues (HGTs) was assessed using immunohistochemistry and real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR). In addition, we investigated the correlation between the expression of S100 and that of other inflammatory mediators (IL-1β, IĸB, IL-10, and TNF-α) in PGs using real-time PCR. In the future, the results of this study may be useful to elucidate the pathophysiology of periapical periodontitis.

Materials and Methods

Sample collection. The Ethics Committee of the Nihon University School of Dentistry approved the experimental protocol of this study (EP18D014), and all patients provided written informed consent for treatment and publication of findings. The study was conducted in accordance with the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. Periapical periodontitis samples were obtained from patients (n=44; 26 men and 18 women; age, 32-64 years) during endodontic surgery and tooth extraction upon clinical examination. No systemic disease was observed in the patients. Additionally, the patients did not report consuming any medications (for six months prior to the endodontic surgery) that could affect the inflammatory responses. HGTs were obtained when impacted wisdom teeth were extracted from patients at the Department of Oral Surgery (n=5; 3 men and 2 women; age, 25-37 years).

Preparation of tissue sections. The samples were divided in half immediately after the periapical lesions were excised. One half of the divided tissues was fixed with 10% neutral-buffered formalin and paraffin sections (4-μm thick) were prepared. The other half of the tissue samples was fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde prepared in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), embedded in OCT compound (Tissue-Tek, Elkhart, IN, USA), and frozen in dry-ice acetone. These samples were then used for RNA preparation. HGT samples were also prepared as described above.

Histological examination. Haematoxylin-eosin (HE) staining was performed to investigate tissue histopathology. After staining, three different fields in each tissue section were examined under a light microscope (Olympus BX60, Tokyo, Japan).

Immunohistochemistry. Paraffin sections were subjected to immunohistochemistry to identify S100A4-expressing inflammatory cells in human PGs. The paraffin sections were first treated for 30 min at room temperature (RT) with 0.3% H2O2 prepared in methanol to inactivate endogenous peroxidase, and non-specific binding was blocked by incubation in 1.5% normal horse serum (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) for 90 min. The sections were probed with a rabbit anti-human S100A4 monoclonal antibody (1:100; Abcam, Cambridge, UK) in a humid atmosphere at RT for 2 h. Then, the sections were washed with PBS and incubated with biotinylated horse anti-rabbit IgG antibody (1:500; Vector Laboratories) at RT for 30 min. This was followed by an incubation with the avidin-biotin peroxidase complex (Vector Laboratories) for 30 min. Optimum colour development of positive cells was achieved by incubating with horseradish peroxidase substrates (3,3’-diaminobenzidine, Vector Laboratories) for 1 min. Immunohistochemistry on HGT sections (negative control) was performed using the same technique as that used for the PG tissues.

RNA extraction and real-time PCR. Total RNA was extracted from frozen PG tissues or HGT using 1 ml of TRIzol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and was used for reverse transcribing complementary DNA (40 ng; 25 μl reaction mixtures containing TB Green Premix Ex Taq (Takara Bio, Shiga, Japan), and the sense and antisense PCR primers (20 μmol/l, each; Table I) against human S100A4, IL-1β, IĸB, IL-10, TNF-α, and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH)). PCRs were performed on a Smart Cycler (Cepheid, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) in accordance with the manufacturer’s protocols. The expression of target genes was normalised to that of GAPDH.

Table I. PCR primers used to detect the mRNA levels of S100A4, IL-1β, IĸB, IL-10, TNF-α, and GAPDH in periapical granulomas and healthy gingival tissues.

Statistical analysis. Gene expression data were analysed using SPSS version 15.0 for Windows (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). The expression of S100A4 and IL-1β in PGs and HGTs was compared using the Mann-Whitney U-test. The Pearson’s correlation coefficient was used to analyse the correlation between the expression of S100A4 and that of the four inflammatory mediators (IL-1β, IĸB, IL-10, and TNF-α). p-Values <0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Histological evaluation of periapical lesions and HGTs. To define the pathological features of the periapical lesions (n=44), paraffin sections of the periapical lesions were evaluated using HE staining. Of the 44 periapical lesions examined by light microscopy, 32 contained granulomatous tissues characterised by infiltration of numerous inflammatory cells, such as lymphocytes, macrophages, and plasma cells (Figure 1A). No epithelial cells were detected in any fields of these samples, and the specimens were diagnosed as PGs. The remaining 12 lesion sections exhibited granulomatous tissues with complete epithelial lining and surrounding collagen fibres (Figure 1B). These specimens were diagnosed as radicular cysts and were excluded from this study. HGTs contained more collagen fibres beneath the epithelial cell layers and fewer inflammatory cells than the periapical lesions (Figure 1C).

Figure 1. Histological examination of periapical lesions and healthy gingival tissues (HGTs) stained by haematoxylin and eosin (HE). (A) Periapical granulomas (PGs) exhibiting rich vasculature and inflammatory cell infiltration; (B) Radicular cysts (RCs) with epithelial cell lining; and (C) HGTs. Scale bars=100 μm.

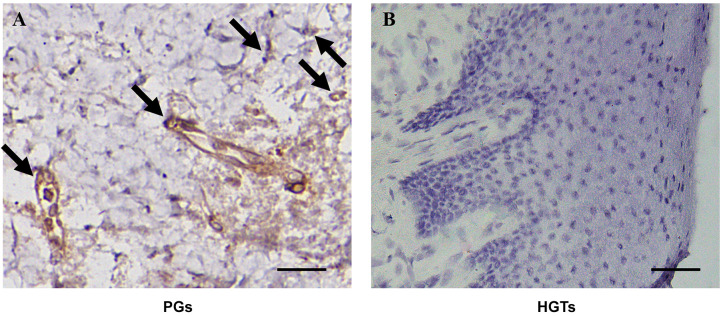

Immunohistochemistry. S100A4-positive endothelial cells and fibroblasts were observed in the human PG sections. Additionally, S100A4 was expressed in the lymphocytes present in the blood vessels of PGs (Figure 2A). None of the HGTs expressed S100A4 (Figure 2B).

Figure 2. Immunohistochemical analysis of PGs with human S100A4 antibody. (A) S100A4-positive endothelial cells, fibroblasts, and lymphocytes were observed in human periapical granulomas (PGs). Arrows indicate the cells expressing S100A4 (Scale bar=15 μm). (B) S100A4 expression was not detected in healthy gingival tissues (HGTs) (Scale bar=50 μm).

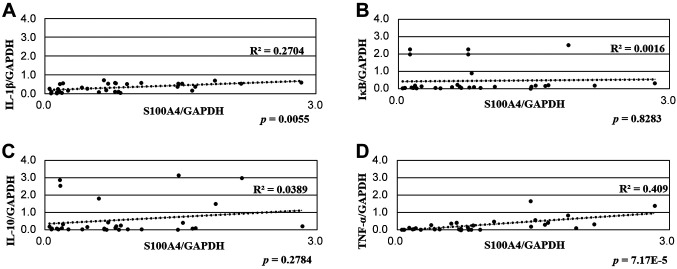

Real-time PCR analysis. To detect S100A4, IL-1β, IĸB, IL-10, and TNF-α mRNA expression in PGs and HGTs, all frozen tissues (32 PGs and 5 HGTs) were examined using real-time PCR analysis. All specimens expressed the mRNAs of S100A4 and the four inflammatory mediators (Figure 3). The HGT samples also expressed mRNAs of S100A4 and the four inflammatory mediators; however, the expression levels were significantly lower than that in PGs (p<0.01). The expression of IL-1β, IĸB, IL-10, and TNF-α mRNAs was compared with S100A4 mRNA expression, and the correlation was examined using Pearson’s correlation coefficient. A positive correlation between the expression of S100A4 and IL-1β and that of S100A4 and TNF-α was noted (Figure 4A and D). However, no correlation between the expression of S100A4 and IĸB and that of S100A4 and IL-10 was observed (Figure 4B and C).

Figure 3. Real-time PCR analysis for S100A4, IL-1β, IĸB, IL-10, and TNF-α mRNA expression in periapical granulomas (PGs) and healthy gingival tissues (HGTs); mRNA expression was normalised to that of GAPDH mRNA expression. Horizontal black bars indicate the median. The expression levels of all mRNAs in HGTs were significantly lower than those in PGs. **p<0.01 (Mann-Whitney U-test).

Figure 4. Real-time PCR and Pearson’s correlation coefficient analysis were performed to compare the mRNA expression of S100A4 with that of IL-1β, IĸB, IL-10, and TNF-α in human periapical granulomas (PGs). (A, D) A positive correlation between the expression of S100A4 and IL-1β (p=0.0055, R2=0.2704) and that of S100A4 and TNF-α (p<0.001, R2=0.409) was noted. (B, C) A correlation between the expression of S100A4 and IĸB (p=0.8283, R2=0.0016) and that of S100A4 and IL-10 (p=0.2784, R2=0.0389) was not observed.

Discussion

Apical periodontitis occurs as a result of endodontic infection, and arises as a host defence response to the presence of bacteria and bacteria-related substances that are continuously released from the root canal system (1,2,5). Thus, as apical periodontitis is caused by an infection of the root canal system (7), the treatment plan involves the eradication of bacteria or reduction of the bacterial metabolites prior to root canal filling (3). Although root canal treatments have a high degree of success, apical periodontitis may not heal despite proper endodontic treatment (4). Tooth extraction may be performed in such cases (4). Hence, elucidation of the pathophysiology of apical periodontitis may aid the development of endodontic treatments that address such cases. However, several details about the pathophysiology of apical periodontitis remain unclear.

S100A4 expression has been reported to be upregulated in malignant tumours and is a well-known biomarker for the same (32). Additionally, S100A4 is associated with the pathogenesis of various chronic inflammatory diseases with bone resorption by the regulation of inflammatory cytokine expression (20-31). Hence, the purpose of this study was to clarify the function of S100A4 in periapical periodontitis, which is an inflammatory disease associated with bone resorption similar to rheumatoid arthritis and periodontitis.

In this study, we demonstrated the expression of S100A4 in human PGs. Using immunohistochemistry, we showed that in human PGs, S100A4 is expressed by inflammatory cells, such as endothelial cells, lymphocytes, and fibroblasts. In contrast, cells expressing S100A4 have not been reported in HGTs, and were used as a negative control in this study. S100A4 is known to contribute to cartilage destruction and the pathogenesis of chronic inflammation (24). Moreover, stimulation by an inflammatory cytokine, IL-1β, results in the overexpression of S100A4, and promotes the progression of periodontitis (31). Hence, these findings suggested that S100A4 expression may be involved in the pathogenesis of human PGs.

To compare S100A4 and IL-1β mRNA expression between PGs and HGTs, quantitative real-time PCR was performed. Notably, the expression of S100A4 and IL-1β mRNA was observed in all PG and HGT samples, and the expression of these molecules was significantly higher in PGs than that in HGTs. Recent studies have reported that the IL-1β-induced matrix metalloproteinase-13 (MMP-13) expression is upregulated by S100A4, and the absence of S100A4 expression inhibits bone metabolism by reducing MMP-3 and MMP-9 expression (29,33). Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that IL-1β stimulation induces S100A4 expression, resulting in the suppression of bone formation, and enhances matrix degradation in periodontal models (31).

Moreover, to investigate the correlation between S100A4 and IĸB, IL-10, and TNF-α mRNA expression, real-time PCR and Pearson’s correlation coefficient analyses were performed. No correlation was observed between the expression of S100A4 and IĸB and that of S100A4 and IL-10. In contrast, a positive correlation was observed between the expression of S100A4 and TNF-α. Thus, S100A4 may be intricately involved in PG pathogenesis. However, the molecular mechanisms underlying IL-1β-induced S100A4 expression and subsequent induction of TNF-α expression were not addressed in this study and remain unclear.

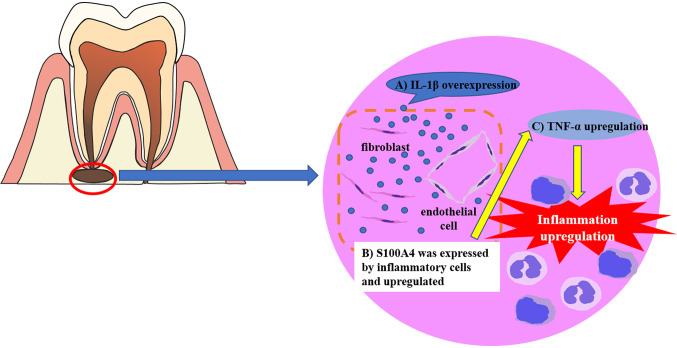

In conclusion, the results of this study indicated that in PGs, S100A4 was expressed in response to stimulation with the inflammatory cytokine, IL-1β. Furthermore, S100A4 may act in an autocrine or paracrine manner to promote TNF-α expression, thereby exacerbating the inflammatory response in PGs (Figure 5). Thus, based on these results, we propose that the administration of S100A4 inhibitors, using local drug delivery systems, during root canal treatments may facilitate tissue healing and prevent disease progression. Further studies are required to elucidate the molecular mechanism underlying S100A4 activity and explore the potential of local drug delivery systems for administering S100A4 inhibitors.

Figure 5. Potential role of S100A4 in periapical granulomas (PGs). (A) Inflammatory cells infiltrate and express IL-1β in PGs. (B) IL-1β induces S100A4 expression in inflammatory cells. (C) The expression of TNF-α stimulated by S100A4 upregulates the inflammatory response.

Conflicts of Interest

The Authors have no conflicts of interest to declare in relation to this study.

Authors’ Contributions

T.T. and T.M. performed the experiments and acquired the data. K.H., T.N., and Y.T. analysed and interpreted the data. O.T. critically reviewed the drafts of the article. K.H. conceived and designed the experiments.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by grants from the Sato Fund (2018 and 2019) and JSPS KAKENHI Grant Numbers 2586112 and 15K20415. The Authors would like to thank Editage (www.editage.jp) for English language editing.

References

- 1.Nair PN. On the causes of persistent apical periodontitis: a review. Int Endod J. 2006;39(4):249–281. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2006.01099.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nair PN. Apical periodontitis: a dynamic encounter between root canal infection and host response. Periodontol 2000. 1997;13:121–148. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.1997.tb00098.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lin L, Huang GTJ. Pathobiology of apical periodontitis. In: Cohen’s pathways of the pulp, 11th edn. In: Berman LH, Hargreaves KM, Cohen S, Burns RC, editors. Mosby Elsevier: St Louis. 2016. p. pp. 630. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nair PN. Pathogenesis of apical periodontitis and the causes of endodontic failures. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 2004;15(6):348–381. doi: 10.1177/154411130401500604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kakehashi S, Stanley HR, Fitzgerald RJ. The effects of surgical exposures of dental pulps in germ-free and conventional laboratory rats. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1965;20:340–349. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(65)90166-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Martinez ZR, Naruishi K, Yamashiro K, Myokai F, Yamada T, Matsuura K, Namba N, Arai H, Sasaki J, Abiko Y, Takashiba S. Gene profiles during root canal treatment in experimental rat periapical lesions. J Endod. 2007;33(8):936–943. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2007.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stashenko P, Yu SM, Wang CY. Kinetics of immune cell and bone resorptive responses to endodontic infections. J Endod. 1992;18(9):422–426. doi: 10.1016/S0099-2399(06)80841-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang CY, Stashenko P. Characterization of bone-resorbing activity in human periapical lesions. J Endod. 1993;19(3):107–111. doi: 10.1016/S0099-2399(06)80503-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gonzalez LL, Garrie K, Turner MD. Role of S100 proteins in health and disease. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Res. 2020;1867(6):118677. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2020.118677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moore BW. Chemistry and biology of two brain-specific proteins, s-100 and 14-3-2. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1972;32(0):5–7. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4684-6979-0_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pietzsch J. S100 proteins in health and disease. Amino Acids. 2011;41(4):755–760. doi: 10.1007/s00726-010-0816-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Salama I, Malone PS, Mihaimeed F, Jones JL. A review of the S100 proteins in cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2008;34(4):357–364. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2007.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Donato R, Cannon BR, Sorci G, Riuzzi F, Hsu K, Weber DJ, Geczy CL. Functions of S100 proteins. Curr Mol Med. 2013;13(1):24–57. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Donato R, Sorci G, Riuzzi F, Arcuri C, Bianchi R, Brozzi F, Tubaro C, Giambanco I. S100B’s double life: intracellular regulator and extracellular signal. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1793(6):1008–1022. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2008.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goyette J, Yan WX, Yamen E, Chung YM, Lim SY, Hsu K, Rahimi F, Di Girolamo N, Song C, Jessup W, Kockx M, Bobryshev YV, Freedman SB, Geczy CL. Pleiotropic roles of S100A12 in coronary atherosclerotic plaque formation and rupture. J Immunol. 2009;183(1):593–603. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kraus C, Rohde D, Weidenhammer C, Qiu G, Pleger ST, Voelkers M, Boerries M, Remppis A, Katus HA, Most P. S100A1 in cardiovascular health and disease: closing the gap between basic science and clinical therapy. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2009;47(4):445–455. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2009.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sinha P, Okoro C, Foell D, Freeze HH, Ostrand-Rosenberg S, Srikrishna G. Proinflammatory S100 proteins regulate the accumulation of myeloid-derived suppressor cells. J Immunol. 2008;181(7):4666–4675. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.7.4666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Berge G, Mælandsmo GM. Evaluation of potential interactions between the metastasis-associated protein S100A4 and the tumor suppressor protein p53. Amino Acids. 2011;41(4):863–873. doi: 10.1007/s00726-010-0497-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ambartsumian N, Grigorian M. [S100A4, a link between metastasis and inflammation] Mol Biol (Mosk) 2016;50(4):577–588. doi: 10.7868/S0026898416040029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cerezo LA, Kuncová K, Mann H, Tomcík M, Zámecník J, Lukanidin E, Neidhart M, Gay S, Grigorian M, Vencovsky J, Senolt L. The metastasis promoting protein S100A4 is increased in idiopathic inflammatory myopathies. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2011;50(10):1766–1772. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ker218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cerezo LA, Remáková M, Tomčik M, Gay S, Neidhart M, Lukanidin E, Pavelka K, Grigorian M, Vencovský J, Šenolt L. The metastasis-associated protein S100A4 promotes the inflammatory response of mononuclear cells via the TLR4 signalling pathway in rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2014;53(8):1520–1526. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keu031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grum-Schwensen B, Klingelhöfer J, Beck M, Bonefeld CM, Hamerlik P, Guldberg P, Grigorian M, Lukanidin E, Ambartsumian N. S100A4-neutralizing antibody suppresses spontaneous tumor progression, pre-metastatic niche formation and alters T-cell polarization balance. BMC Cancer. 2015;15:44. doi: 10.1186/s12885-015-1034-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oslejsková L, Grigorian M, Hulejová H, Vencovsky J, Pavelka K, Klingelhöfer J, Gay S, Neidhart M, Brabcová H, Suchy D, Senolt L. Metastasis-inducing S100A4 protein is associated with the disease activity of rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2009;48(12):1590–1594. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kep316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Boye K, Maelandsmo GM. S100A4 and metastasis: a small actor playing many roles. Am J Pathol. 2010;176(2):528–535. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.090526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim H, Lee YD, Kim MK, Kwon JO, Song MK, Lee ZH, Kim HH. Extracellular S100A4 negatively regulates osteoblast function by activating the NF-ĸB pathway. BMB Rep. 2017;50(2):97–102. doi: 10.5483/bmbrep.2017.50.2.170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huxford T, Hoffmann A, Ghosh G. Understanding the logic of IĸB:NF-ĸB regulation in structural terms. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2011;349:1–24. doi: 10.1007/82_2010_99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kanarek N, Ben-Neriah Y. Regulation of NF-ĸB by ubiquitination and degradation of the IĸBs. Immunol Rev. 2012;246(1):77–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2012.01098.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mulero MC, Huxford T, Ghosh G. NF-ĸB, IĸB, and IKK: Integral components of immune system signaling. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2019;1172:207–226. doi: 10.1007/978-981-13-9367-9_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Erlandsson MC, Svensson MD, Jonsson IM, Bian L, Ambartsumian N, Andersson S, Peng Z, Vääräniemi J, Ohlsson C, Andersson KME, Bokarewa MI. Expression of metastasin S100A4 is essential for bone resorption and regulates osteoclast function. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1833(12):2653–2663. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2013.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mah SJ, Lee J, Kim H, Kang YG, Baek SH, Kim HH, Lim WH. Induction of S100A4 in periodontal ligament cells enhances osteoclast formation. Arch Oral Biol. 2015;60(9):1215–1221. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2015.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhou M, Li ZQ, Wang ZL. S100A4 upregulation suppresses tissue ossification and enhances matrix degradation in experimental periodontitis models. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2015;36(11):1388–1394. doi: 10.1038/aps.2015.77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Oslejsková L, Grigorian M, Gay S, Neidhart M, Senolt L. The metastasis associated protein S100A4: a potential novel link to inflammation and consequent aggressive behaviour of rheumatoid arthritis synovial fibroblasts. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67(11):1499–1504. doi: 10.1136/ard.2007.079905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Miranda KJ, Loeser RF, Yammani RR. Sumoylation and nuclear translocation of S100A4 regulate IL-1beta-mediated production of matrix metalloproteinase-13. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(41):31517–31524. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.125898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]