Abstract

Background

Cough lasting 3–8 weeks and more than 8 weeks are defined as subacute/prolonged cough and chronic cough, respectively. Japanese chronic cough population has not been well studied. This study aimed to describe the prevalence and characteristics of chronic cough and subacute cough patients in Japan. This study also sought to compare between chronic cough patients who were not greatly satisfied with treatment effectiveness for resolving cough and other chronic cough patients.

Methods

Data from a cross-sectional online 2019 Japan National Health and Wellness Survey and a supplemental chronic cough survey were used to understand respondents’ chronic cough status and their cough-specific characteristics and experience. The prevalence, patient characteristics and cough-specific characteristics were summarised descriptively. Patients who were not greatly satisfied with treatment effectiveness and other chronic cough patients were compared for their characteristics and cough severity.

Results

The point prevalence of chronic cough was 2.89% and 12-month period prevalence was 4.29%. Among all chronic cough patients analysed, the average age was 56 years old, 61.1% were males and 29.4% were current smokers. Patients were most frequently told by a physician that cough was related to allergic rhinitis, asthma and cough variant asthma. Only 44.2% of chronic cough patients had spoken with a physician about their cough, and half of chronic cough patients did not use any medications. Patients who were not greatly satisfied with treatment effectiveness had significantly greater cough severity during past 2 weeks compared with other chronic cough patients (Visual Analogue Scale 45.34 vs 39.63).

Conclusions

This study described the prevalence and patient characteristics information of chronic cough patients in Japan. Furthermore, the study highlighted an unmet need for better diagnosis and treatments for chronic cough patients, especially among patients who were not greatly satisfied with treatment effectiveness and reported significantly worse cough severity.

Keywords: clinical epidemiology, cough/mechanisms/pharmacology

Key messages.

To describe the prevalence estimate and patient characteristics of chronic cough and subacute cough in Japan, and to summarise the underlying causes and treatment use among chronic cough patients.

The point prevalence of chronic cough in Japan was estimated to be 2.89%, with allergic rhinitis, asthma and cough variant asthma being the most common diseases told by a physician to be related to cough. There was unmet need for better diagnosis and treatment among chronic cough patients.

There is limited research describing the prevalence and characteristics of chronic cough patients in Japan and this study provides novel information through a population-based survey.

Introduction

Cough is one of the most common reasons for patients seeking primary care worldwide.1 In Japan, cough has been reported as the most common reason for encounter among patients visiting outpatient clinics and hospitals.2 3 Cough can be classified based on its duration. Acute cough is defined as cough lasting for less than 3 weeks and is commonly caused by upper respiratory tract infections. If cough persists for longer than 3 weeks, it is defined either as subacute/prolonged cough (3–8 weeks), or chronic cough (more than 8 weeks).4–6

Chronic cough treatment guidelines highlight the need to identify the potential causes of cough and to provide treatment for the underlying causes.7 While identification of what causes the cough may lead to specific and successful treatment in up to 98% of cases,8 9 a group of patients still suffer from persistent cough despite diagnosis according to treatment guidelines and are considered refractory chronic cough (RCC) patients.10–13 Additionally, suffering from chronic cough has been reported to have negative impact on patients’ quality of life (QoL).14

The global prevalence of chronic cough has previously been estimated to be 9.6%, with a higher prevalence observed in Europe 12.7% and America 11.0% compared with Asia 4.4%, and Africa 2.3%.15 In Japan, one study previously estimated the prevalence of cough to be 10.2%, and that 23.2% of the cough population suffered from chronic cough, giving an estimated prevalence of chronic cough of above 2%. The same study showed that more than 60% of surveyed individuals with cough did not receive any care for their condition.16 Other than that, however, there is limited research describing the prevalence and characteristics of chronic cough patients in Japan. Hence, the current study sought to describe the prevalence estimate and patient characteristics of chronic cough and subacute cough in Japan, and to summarise the underlying causes and treatment use among chronic cough patients. The secondary objective was to compare patient characteristics and cough severity between chronic cough patients who were not greatly satisfied with treatment effectiveness for resolving cough and other chronic cough patients.

Methods

This is an observational, cross-sectional study based on the 2019 Japan National Health and Wellness Survey (NHWS). Respondents who completed the 30 min NHWS and met the definition for subacute cough or chronic cough subsequently received a supplemental chronic cough survey. All respondents provided informed consent prior to participation.

Patient and public involvement

Patients or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of our research. The data used in this study were obtained from patients and respondents who provided self-reported information through the online surveys.

Study population

Potential respondents to the NHWS were recruited through an existing, general-purpose (ie, not healthcare specific) web-based consumer panel. The consumer panel recruits its panel members through opt-in emails, co-registration with panel partners, e-newsletter campaigns, banner placements and affiliation networks. All panellists explicitly agreed to be a panel member. Panel members were compensated in terms of panel points for their time, depending on the length of the survey. A stratified random sampling procedure, with strata by gender and age at the national level, was implemented to ensure that the demographic composition of the NHWS sample is representative of the Japanese adult population.17 18 Age and gender differences between regions were not considered in the sampling frame. Though the stratified random sampling approach did not account for region, the NHWS sample was overall comparable to the Japanese adult population with respect to region distribution.

Respondents 20 years or older who completed the NHWS and self-reported having cough daily for at least 3 weeks at any time in the past 12 months were invited to participate in the chronic cough survey. Respondents were excluded from the analysis if they met any of the following criteria: (1) self-reported in NHWS or the chronic cough survey of any form of lung cancer, interstitial lung disease, such as idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis or currently taking an ACE inhibitor or (2) self-reported experienced chronic cough in the NHWS but did not participate in the chronic cough survey. Patients with lung cancer and interstitial lung disease were excluded from the analysis with the consideration that the patient characteristics and treatment patterns of this group of patients with severe diseases is expected to be different from other patients where cough may persist despite comprehensive diagnostic process and treatment of other underlying conditions.

Subacute cough and chronic cough patients were defined as respondents self-reporting coughing for 3–8 weeks or greater than 8 weeks, respectively, at any time in the past 12 months. These respondents were considered ‘current’ subacute or chronic cough if cough was reported as present at the time of survey.

Chronic cough patients were asked if they had been informed by a physician of any conditions or behaviours that were related to their cough and the degree to which medications for these conditions treated cough adequately. As an attempt to understand RCC patients, patients who reported a condition but the medications for these conditions did not resolve cough ‘a great deal’ were identified as chronic cough patients who were not greatly satisfied with treatment effectiveness for resolving cough. This definition was our best effort to reflect the guidelines, and based on the information available in this study.12 Chronic cough patients who reported that they had not been informed by a physician of any conditions or behaviours related to chronic cough or reported ‘don’t know’, despite having seen healthcare professionals since experiencing chronic cough and having spoken with a physician for chronic cough, were identified as ‘chronic cough patients whose underlying diseases were unknown’.

Covariates collected from NHWS

Demographic measures included age, gender and employment status. General health characteristics included body mass index (BMI), smoking status, alcohol use, exercise behaviour and Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI). The CCI reflects the presence and seriousness of chronic comorbid diseases. An adapted version of the CCI was created excluding chronic pulmonary disease from the index score. Higher index indicates greater comorbid burden.19–21

Variables collected from chronic cough questionnaire

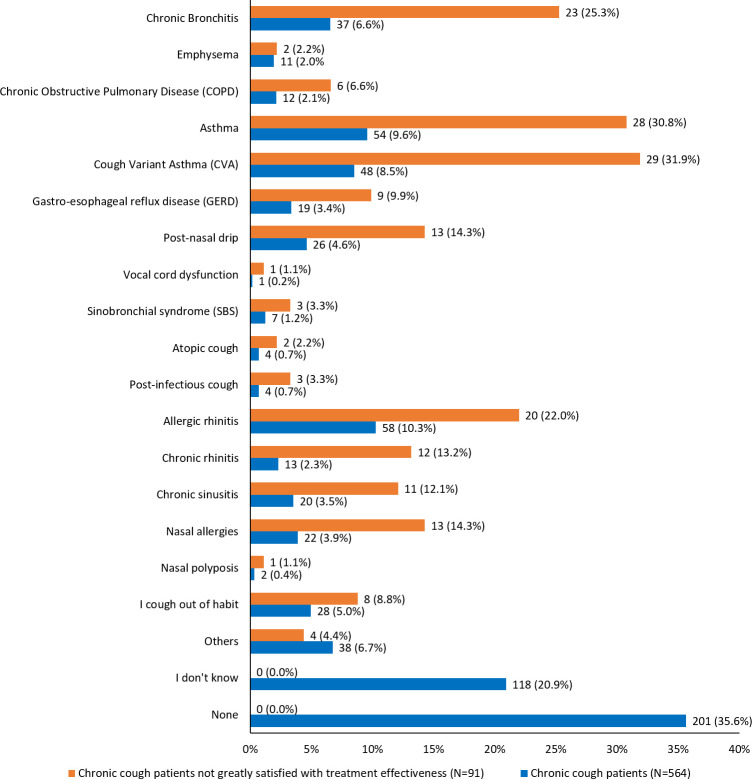

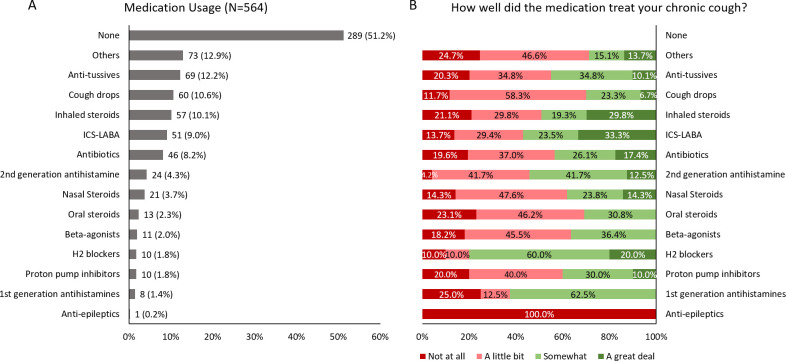

Underlying diseases related to chronic cough were self-reported from the question ‘Has a doctor ever told you that any of the following conditions or behaviours are related to your chronic cough’. Responses were chosen from a predefined list of diseases (refer to full list in figure 1). Chronic cough patients self-reported their medication usage for chronic cough and satisfaction with the treatment. Medication was chosen from a pre-defined list of medication categories and their corresponding medications (refer to full list in figure 2). The satisfaction was measured by asking ‘How well did medication treat chronic cough’, with the response options ‘not at all’, ‘a little bit’, ‘somewhat’ or ‘a great deal’.

Figure 1.

Self-reported underlying conditions in chronic cough patients and chronic cough patients not greatly satisfied with treatment effectiveness for resolving cough note: patients were allowed to choose multiple underlying diseases. If there were no underlying diseases, patients were allowed to choose only ‘I don’t know’ or ‘none’. Only 564 chronic cough patients answered the question about underlying diseases.

Figure 2.

Self-reported medication usage and satisfaction in chronic cough patients. ICS-LABA, Inhaled Corticosteroid and Long-Acting β2-Agonist.

Cough-related characteristics reported included smoking behaviour, years experienced chronic cough, seasonality of cough, frequency of coughing up phlegm, etc (full list in online supplemental table 1). Chronic cough patients self-reported physician’s visit by answering yes/no to ‘had ever spoken with a physician about their cough’.

bmjresp-2020-000832supp001.pdf (119.1KB, pdf)

Cough severity over the past 2 weeks and on the worst day during the past 2 weeks, were assessed by a Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) ranging from 0 (no cough) to 100 (extremely severe cough).

Statistical analysis

Both 12-month period prevalence (patients who experienced cough in the past 12 months) and point prevalence (patients currently coughing at the time of survey) were estimated for chronic cough and subacute cough. Twelve-month period prevalence of chronic cough and subacute cough was analysed descriptively using the total number of respondents who responded to the question ‘Have you had cough lasting the following periods in the past 12 months’ as denominator, and the number of chronic and subacute cough patients as numerator, respectively. Point prevalence was estimated by using the same denominator, and the number of current chronic and subacute cough patients as numerator.

Prevalence was also calculated using the same methodology for four subgroups: (1) male younger than 60 years old, (2) male 60 years or older, (3) female younger than 60 years old and (4) female 60 years or older. Descriptive analyses were conducted for demographics and health characteristics of all respondents, current chronic cough patients, current subacute cough patients, chronic cough patients who were not greatly satisfied with treatment effectiveness for resolving cough, and chronic cough patients whose underlying diseases were unknown. Underlying causes, treatment use and satisfaction for chronic cough patients were also summarised. All continuous variables were summarised using mean and standard deviation (SD). All categorical variables were summarised using number of respondents and its percentage.

Bivariate analysis was conducted for comparison of demographics, health characteristics and severity in chronic cough patients who were not greatly satisfied with treatment effectiveness for resolving cough and other chronic cough patients by independent t-test for continuous variables and χ2 test for categorical variables. P values of less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Bivariate subgroup analysis was also performed between chronic cough patients currently smoking and not smoking and between chronic cough patients whose underlying diseases were unknown and all other chronic cough patients, to compare their demographics, health characteristics and cough severity.

Results

Participants

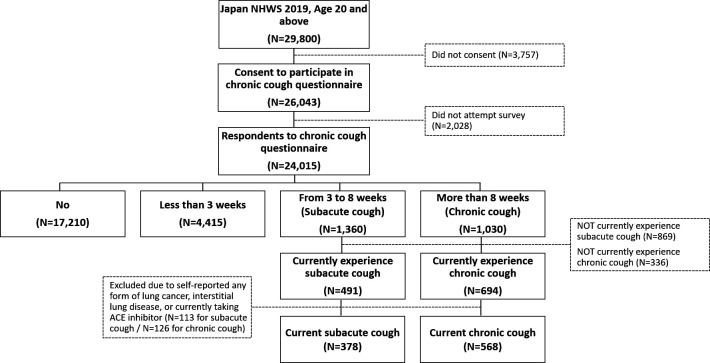

Among the 29 800 adult respondents to the NHWS 2019 who were 20 years and older, 26 043 adults provided informed consent to participate in the chronic cough survey, whereof 24 015 adults attempted the question ‘Have you had cough lasting the following periods in the past 12 months’ to screen for chronic cough and subacute cough patients. Out of these 24 015 respondents, 1030 patients experienced cough for more than 8 weeks, and 1360 patients experienced cough for 3–8 weeks. Of these, 694 respondents were currently suffering from chronic cough and 491 from subacute cough, before excluding patients with self-reported lung cancer, interstitial lung disease or currently taking an ACE inhibitor. Among these patients, 568 current chronic cough patients and 378 current subacute cough patients were included in further analyses (figure 3).

Figure 3.

Respondent flow chart. NHWS, National Health and Wellness Survey.

Prevalence

The point prevalence and 12-month period prevalence of chronic cough was 2.89% and 4.29%, respectively. The point prevalence of subacute cough was 2.04%, and the 12-month period prevalence was 5.66% (table 1). The point and 12-month period prevalence of chronic cough was greatest in males at least 60 years old (3.85%), while subacute cough was most prevalent in males less than 60 years old (2.73%), and its 12-month period prevalence was highest in females less than 60 years old (6.71%). After applying exclusion criteria, the point prevalence of chronic cough was 2.37% and 1.57% for subacute cough (table 1).

Table 1.

Point prevalence and 12-month period prevalence estimate for chronic and subacute cough

| Total | Point prevalence (before exclusion) | Point prevalence (after exclusion*) | 12-month period prevalence | ||||

| Count | Prevalence,% | Count | Prevalence, % | Count | Prevalence, % | ||

| Chronic cough | |||||||

| All respondents | 24 015 | 694 | 2.89 | 568 | 2.37 | 1030 | 4.29 |

| <60 male | 7485 | 217 | 2.90 | 175 | 2.34 | 310 | 4.14 |

| <60 female | 7036 | 142 | 2.02 | 118 | 1.68 | 277 | 3.94 |

| ≥60 male | 5605 | 216 | 3.85 | 172 | 3.07 | 273 | 4.87 |

| ≥60 female | 3889 | 119 | 3.06 | 103 | 2.65 | 170 | 4.37 |

| Subacute cough | |||||||

| All respondents | 24 015 | 491 | 2.04 | 378 | 1.57 | 1360 | 5.66 |

| <60 male | 7485 | 204 | 2.73 | 139 | 1.86 | 492 | 6.57 |

| <60 female | 7036 | 140 | 1.99 | 120 | 1.71 | 472 | 6.71 |

| ≥60 male | 5605 | 94 | 1.68 | 71 | 1.27 | 216 | 3.85 |

| ≥60 female | 3889 | 53 | 1.36 | 48 | 1.23 | 180 | 4.63 |

*Respondents were excluded from the analysis if they met any of the following criteria: (1) self-reported in NHWS or the chronic cough survey of any form of lung cancer, interstitial lung disease, such as idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, or currently taking an ACE inhibitor or (2) self-reported experienced chronic cough in the NHWS but did not participate in the chronic cough survey.

NHWS, National Health and Wellness Survey.

Demographic and health characteristics

The mean age of all respondents who were screened for chronic cough (N=24 015) was 52 years old, 54.5% were male and 58.9% currently employed (table 2). The mean CCI among all respondents was 0.15, and the adapted CCI was 0.14. More than half of the respondents were of normal weight, that is, BMI range=18.5≤BMI <23 kg/m2 (66.1%), currently consumed alcohol (64.3%) and had never smoked (57.5%), while 19.1% were current smokers and 47.4% had exercised in the past 30 days.

Table 2.

Demographics and health characteristics for all respondents, current chronic cough patients and current subacute cough patients

| Continuous variable | All respondents (N=24 015) |

Current chronic cough patients (N=568) | Current subacute cough patients (N=378) | |||

| Mean (SD) | Median (IQR) | Mean (SD) | Median (IQR) | Mean (SD) | Median (IQR) | |

| Age | 52.26 (16.37) | 53.00 (28.00) | 56.01 (15.15) | 58.50 (25.00) | 50.73 (15.46) | 50.00 (27.00) |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index | 0.15 (0.54) | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.33 (0.67) | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.21 (0.55) | 0.00 (0.00) |

| Adapted Charlson Comorbidity Index | 0.14 (0.52) | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.23 (0.55) | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.17 (0.47) | 0.00 (0.00) |

| Categorical variable | Count (%) | Count (%) | Count (%) |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 13 090 (54.5) | 347 (61.1) | 210 (55.6) |

| Female | 10 925 (45.5) | 221 (38.9) | 168 (44.4) |

| Currently employed | |||

| No | 9861 (41.1) | 252 (44.4) | 123 (32.5) |

| Yes | 14 154 (58.9) | 316 (55.6) | 255 (67.5) |

| BMI category | |||

| Underweight (BMI <18.5) | 2666 (11.1) | 54 (9.5) | 41 (10.8) |

| Normal weight (18.5 ≤BMI <23) | 15 874 (66.1) | 373 (65.7) | 249 (65.9) |

| Overweight (23≤ BMI <25) | 3754 (15.6) | 94 (16.5) | 63 (16.7) |

| Obese (BMI ≥25) | 727 (3.0) | 31 (5.5) | 13 (3.4) |

| Decline to answer | 994 (4.1) | 16 (2.8) | 12 (3.2) |

| Smoking status (NHWS) | |||

| Never | 13 819 (57.5) | 267 (47.0) | 197 (52.1) |

| Former | 5621 (23.4) | 134 (23.6) | 84 (22.2) |

| Current | 4575 (19.1) | 167 (29.4) | 97 (25.7) |

| Currently smoke cigarettes (cough questionnaire) | |||

| No | – | 391 (68.8) | 249 (65.9) |

| Yes | – | 177 (31.2) | 129 (34.1) |

| Use of alcohol | |||

| Abstain | 8581 (35.7) | 191 (33.6) | 108 (28.6) |

| Currently consume alcohol | 15 434 (64.3) | 377 (66.4) | 270 (71.4) |

| Vigorous exercise in past 30 days | |||

| No | 12 634 (52.6) | 305 (53.7) | 163 (43.1) |

| Yes | 11 381 (47.4) | 263 (46.3) | 215 (56.9) |

BMI, body mass index; NHWS, National Health and Wellness Survey.

Current chronic cough patients (N=568) were older (mean age of 56), and a greater percentage were males (61.1%) (table 2). The mean CCI was 0.33 and adapted CCI was 0.23, which was higher than other respondent groups. Similar to all respondents, more than half were currently employed (55.6%), of normal weight (65.7%), currently consumed alcohol (66.4%) and had exercised in the past 30 days (46.3%). Compared with other groups, current chronic cough patients had the highest proportion of current smokers (29.4%) and the lowest percentage of never smokers (47.0%). The prevalence of chronic cough was lower among non-smokers for all age and gender subgroups (online supplemental table 2). A subgroup analysis of current smokers versus not current smokers among current chronic cough patients showed that smokers were more likely to be male (76.30%), had increased cough severity (VAS 0–100: 44.60 vs 38.72, p=0.003) and that fewer chronic cough current smokers had spoken with their physician about their cough (26.60% vs 52.20%, p<0.001) (online supplemental table 3).

Current subacute cough patients had the lowest mean age (51) compared with other respondent groups. Current subacute cough patients had 55.6% males. The mean CCI was 0.21 and adapted CCI was 0.17, which was higher than no cough but lower than chronic cough patients. Compared with all respondents and current chronic cough patients, a higher percentage of current subacute cough patients were currently employed (67.5%), currently consumed alcohol (71.4%), and had exercised in the past 30 days (56.9%). Compared with all respondents, a lower percentage had never smoked (52.1%), while 25.7% were current smokers. The overall prevalence of subacute cough was lower among non-smokers with exception for a few age and gender subgroups (online supplemental table 2).

The comparisons among all respondents, current chronic cough patients and current subacute cough patients were numerical, and no statistical tests were conducted between these groups.

Underlying diseases, medication use and satisfaction of chronic cough patients

Among all chronic cough patients, allergic rhinitis (10.3%), asthma (9.6%) and cough variant asthma (CVA) (8.5%) were self-reported by patients as the most common underlying diseases told by the physicians. On the other hand, 35.6% and 20.9% of chronic cough patients answered ‘None’ and ‘I don’t know’ about the underlying diseases related to their cough, respectively, indicating that 56.5% were not certain about the underlying causes (figure 1). These populations included both patients who were informed by the physicians that there were no underlying diseases related to their cough and who had not communicated with physicians about their cough, since less than half (44.2%) of all chronic cough patients had spoken with a physician about their cough (online supplemental table 3). Among these, 54 (9.5%) of the chronic cough patients were not informed or didn’t know about their underlying diseases of chronic cough despite of communication with physicians about their cough. Patient characteristics of these chronic cough patients whose underlying diseases were unknown despite of communication with physicians about their cough, compared with all other chronic cough patients were summarised in online supplemental table 4.

Half of chronic cough patients (51.2%) did not use any medications (figure 2). The most frequently used medications were anti-tussives (12.2%), cough drops (10.6%) and inhaled steroids (10.1%), in addition to others (12.9%) that were not specifically specified. The majority of chronic cough patients taking these medications reported little or no effect for treating their cough. Only two medications, inhaled steroids (29.8%) and inhaled corticosteroid and long-acting β2-agonist (ICS-LABA) (33.3%), were reported to have a great deal effect in about one-third of chronic cough patients taking the respective medications. In chronic cough patients whose underlying diseases were unknown, the most frequently used medications were anti-tussives (22.2%), others (22.2%) and inhaled steroids (13.0%) (online supplemental table 5).

Chronic cough patients not greatly satisfied with treatment effectiveness for resolving cough

A total of 91 (16.0%) patients who were not greatly satisfied with treatment effectiveness were identified among all current chronic cough patients. The most common underlying diseases among this group of patients were CVA (31.9%), asthma (30.8%) and chronic bronchitis (25.3%) (figure 1). More than half (57.1%) of patients in this group had multiple causes.

Bivariate comparison showed that significantly more patients who were not greatly satisfied with treatment effectiveness were females compared with other chronic cough patients (56.0% vs 35.6%, p<0.001) (online supplemental table 6). Patients who were not greatly satisfied with their treatment effectiveness reported significantly greater cough severity across the past 2 weeks (VAS 0–100: 45.34 vs 39.63, p=0.021), and on the worst day during the past 2 weeks (VAS 0–100: 57.41 vs 48.44, p=0.001) compared with other chronic cough patients (online supplemental table 6).

Discussion

This study estimated the prevalence of chronic and subacute cough in Japan, based on survey responses to the 2019 NHWS with a sample representing the general population and the supplemental chronic cough survey. The point prevalence of chronic cough and subacute cough was 2.89% and 2.04%, respectively, which is similar to 2.2%–2.6% previous prevalence estimate of chronic cough in Japan and Korea.16 22 Many previous studies focused on coughing during the year, and the 12-month period prevalence of 4.29% in this study is close to the regional prevalence in Asia (4.4%)15 in the meta-analysis and lower than that in Europe (4%–16%)23–27 and America (8%–14%).15 Significant ethnic differences in cough reflex sensitivity could not be determined in previous research,28 and thus other factors such as environmental factors and other comorbidities may contribute to the observed regional differences.15 Future studies are warranted to better understand the differences in regional chronic cough prevalence.

Additionally, this study described the demographics of chronic cough patients and subacute cough patients, and common underlying diseases, medication use and treatment satisfaction among chronic cough patients. The proportion of chronic cough patients who were not greatly satisfied with treatment effectiveness were reported (as an attempt to understand the group of RCC patients), and it was shown that this group of patients experienced a higher disease severity compared with other chronic cough patients.

The prevalence of both chronic cough and subacute cough were highest among males greater than 60 years old, and the descriptive analysis of patient demographics confirmed that chronic cough patients had a higher mean age and a higher percentage of males (61%) compared with all respondents and subacute cough patients. Another survey of Japanese patients have similarly found the highest chronic cough prevalence among 60–69 years old, and a higher prevalence among men than women (27.7% of the men surveyed vs 16.0% of the women surveyed).16 Increasing age have also been found associated with chronic cough in European and global studies.23–26 29 In contrast, these studies found either an over-representation of chronic cough among women23–25 29 or no gender difference.26 It should be recognised that in this study more men were in the total respondents as well. Factors likely to be responsible for higher prevalence of both chronic cough and subacute cough in males could be the fact that men are more likely to smoke compared with women in Japan and elderly people have a long history of smoking.30 The subgroup analysis also showed that most smoking chronic cough patients were males. Additionally, the fact that the proportion of female smokers is lower in Asia than Western Europe (9.6% vs 23.4%),31 may be a factor influencing the lower percentage of women with chronic cough observed in this study compared with studies of western European populations.23 24

Chronic cough has been strongly correlated with smoking,23 24 32 and in this study, around 30% of chronic cough patients were current smokers which was higher than all respondents. This was higher compared with the survey by Fujimura et al conducted in 2011 wherein, 22% of people who complained of cough were smokers. Notably, this comprised of both persistent cough and chronic cough patients.16 In our study, we found that chronic cough patients who were currently smokers, had a higher cough severity and hesitated to communicate with physicians about their cough, compared with non-smoking chronic cough patients. This indicated the physical and social impact smoking has on the current and possibly future health status in chronic cough patients.

A previous survey suggested that 60.6% of chronic cough patients that had not yet visited a physician.16 Remarkably, we found that 56.5% of chronic cough patients in this study were not certain about the underlying causes, and 55.8% had not spoken to a doctor about their cough. Our findings indicate that a large population of underdiagnosed patients in Japan still remains in 2019.

In our study, patients reported most frequently being told by a physician that their cough was related to allergic rhinitis, asthma and CVA. In comparison, the most common underlying disease found in the Japan 2011 survey was asthma (18.5%),16 and in a UK study the most common underlying disease were asthma, bronchitis and gastro-oesophageal reflux (GORD).33 In addition, it was reported that chronic cough associated with GORD recently became more common in Japan.34 Other studies also mention rhinitis as the most common cause for chronic cough.35 The variance across studies may be due to different demographic composition of the populations, as it has been shown that risk factors differ at both individual and community level, and by smoking status.25 Only half of chronic cough patients reported currently taking medication, and 50%–70% reported no or little effect of the most commonly used medications. This indicates an unmet need for better treatment of chronic cough in Japan. Studies in other countries similarly found the majority of chronic cough patients reporting little or no effectiveness of medication.33 36

In this study, 16% of chronic cough patients were not greatly satisfied with treatment effectiveness. Although accurate identification of RCC patients10 11 was not feasible due to the nature of this study, this group of patients was a close estimate we attempted to construct. These responders had significantly higher severity of cough compared with other chronic cough patients. This suggests an unmet need exists for effective treatments among this specific patient group. The severity of cough was measured using VAS. It has been reported that the minimum clinically important difference for VAS was 17 in acute cough37 and was believed to be of similar magnitude for chronic cough.38 The difference of approximately five observed in our study may not indicate a clinically meaningful difference between the groups. The severity and impact of cough can also be measured using cough-specific QoL instruments, which has been investigated—together with general QoL measures—in a separate manuscript focusing on the disease burden and QoL of patients with chronic cough.39 Patients with chronic cough may suffer from multiple concomitant diseases, where a targeted therapy for each disease have shown to improve symptoms.40 Systematic review on treatment for RCC have highlighted the potential role of repurposed medications such as gabapentin or pregabalin along with speech pathology as alternate treatments to reduce the frequency of cough and improve the QoL. However, further research is needed to fully understand the neural pathways of cough for development of new therapies.41 With regard to new therapies, it was reported that P2X3 receptor antagonist, gefapixant is under clinical evaluation for the treatment of refractory or unexplained chronic cough.42

Among the strengths of this study was that the NHWS and chronic cough survey provided an opportunity to analyse patient clinical characteristics, treatment patterns, and patient-reported outcomes in a real-world setting from the patient perspective. In addition, NHWS is broadly representative of the Japanese adult population, and this population-based nature of the NHWS allows for estimating the prevalence of chronic cough in a valid manner.

However, the limitations of the study should be acknowledged. The NHWS and chronic cough survey are cross-sectional, hence no causality can be concluded. The underlying diseases of chronic cough were self-reported, and the validity of these diseases told by the physicians were not verified through one standard guideline. In addition, although NHWS is broadly representative of the Japanese national adult population, however, like other online patient-reported surveys, it likely be influenced by selection bias and under-represents people without access to or comfort with online administration, as well as less healthy elderly people, institutionalised patients, and those with severe comorbidities and disabilities. Majority of the Japanese population have access to the internet, but respondents who participated in health-related surveys may be more health conscious. Moreover, respondents to NHWS had the option to voluntarily agree to participate in the cough specific questionnaire. Therefore, baseline demographic and health characteristics may differ between participants and non-participants. Subjects who had/have no cough might have lower interest in participating in the cough survey, and samples within the cough module may not be representative of the Japanese chronic cough population. The data of the surveys are self-reported, which introduced recall and self-presentation biases. Although it was our intention to better understand RCC patients, the group analysed in this study was only based on self-reported medication use and satisfaction with the treatment effectiveness, and it could not be validated if patients suffered persistent cough despite treatment according to guidelines as defined in the guidelines for refractory cough.12

Conclusion

In conclusion, the prevalence of chronic cough and subacute cough in Japan was estimated to be 2.89% and 2.04%, respectively. The prevalence of chronic cough was highest among male ≥60 (3.85%), and the most common self-reported underlying diseases were allergic rhinitis (10.3%), asthma (9.6%) and CVA (8.5%). Furthermore, there was an unmet need for better diagnosis and treatment among chronic cough patients, especially among patients who were not greatly satisfied with treatment effectiveness and reported significantly worse cough severity.

Footnotes

Contributors: KT, TK, JS, MA and ST conceptualised the study. KT, TK, KO, MK and YC designed the study and wrote the manuscript. YC and KO performed the statistical analysis. All authors interpreted the results. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This study was sponsored by MSD K.K., Tokyo, Japan.

Competing interests: KT, TK, KO, MK, MA and ST are employees at MSD K.K, Tokyo, Japan. YC is an employee at Kantar, Health Division, Singapore. Kantar received funding from MSD K.K., Tokyo, Japan for conduction of the study, analysis and manuscript development. JS is an employee at Merck Sharp & Dohme, a subsidiary of Merck & Co, Kenilworth, New Jersey, USA.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available on reasonable request.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

Ethics approval

The NHWS survey was approved by the Pearl Pathways Institutional Review Board (IN, US; study number: 19-KANT-196) and the chronic cough survey was reviewed and approved by Toukeikai Kitamachi Clinic ERB (approval number: MSD06756).

References

- 1.Finley CR, Chan DS, Garrison S, et al. What are the most common conditions in primary care? systematic review. Can Fam Physician 2018;64:832–40. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kajiwara N, Hayashi K, Misago M, et al. First-visit patients without a referral to the Department of internal medicine at a medium-sized acute care hospital in Japan: an observational study. Int J Gen Med 2017;10:335–45. 10.2147/IJGM.S146830 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Takeshima T, Kumada M, Mise J, et al. Reasons for encounter and diagnoses of new outpatients at a small community hospital in Japan: an observational study. Int J Gen Med 2014;7:259–69. 10.2147/IJGM.S62384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.The committee for The Japanese Respiratory Society guidelines for management of cough . Concept and use of the guidelines. Respirology 2006;11:S135–6. 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2006.00920_1.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.The committee for The Japanese Respiratory Society guidelines for management of cough . Prolonged cough and chronic cough. Respirology 2006;11:S141–2. 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2006.00920_4.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Irwin RS, French CL, Chang AB, et al. Classification of cough as a symptom in adults and management algorithms. Chest 2018;153:196–209. 10.1016/j.chest.2017.10.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Perotin J-M, Launois C, Dewolf M, et al. Managing patients with chronic cough: challenges and solutions. Ther Clin Risk Manag 2018;14:1041–51. 10.2147/TCRM.S136036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Irwin RS, Curley FJ, French CL. Chronic cough. The spectrum and frequency of causes, key components of the diagnostic evaluation, and outcome of specific therapy. Am Rev Respir Dis 1990;141:640–7. 10.1164/ajrccm/141.3.640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morice AH, McGarvey L, Pavord I, et al. Recommendations for the management of cough in adults. Thorax 2006;61 Suppl 1:i1–24. 10.1136/thx.2006.065144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pratter MR. Unexplained (idiopathic) cough: ACCP evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest 2006;129:220S–1. 10.1378/chest.129.1_suppl.220S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haque RA, Usmani OS, Barnes PJ. Chronic idiopathic cough: a discrete clinical entity? Chest 2005;127:1710–3. 10.1378/chest.127.5.1710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gibson PG, Vertigan AE. Management of chronic refractory cough. BMJ 2015;351:h5590. 10.1136/bmj.h5590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kanemitsu Y, Kurokawa R, Takeda N, et al. Clinical impact of gastroesophageal reflux disease in patients with subacute/chronic cough. Allergol Int 2019;68:478–85. 10.1016/j.alit.2019.04.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.French CL, Irwin RS, Curley FJ, et al. Impact of chronic cough on quality of life. Arch Intern Med 1998;158:1657–61. 10.1001/archinte.158.15.1657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Song W-J, Chang Y-S, Faruqi S, et al. The global epidemiology of chronic cough in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Respir J 2015;45:1479–81. 10.1183/09031936.00218714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fujimura M. Frequency of persistent cough and trends in seeking medical care and treatment-results of an Internet survey. Allergol Int 2012;61:573–81. 10.2332/allergolint.11-OA-0368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kantar . National health and wellness survey: patient-reported healthcare evidence, 2020. Available: https://www.kantar.com/expertise/health/da-real-world-data-pros-claims-and-health-records/national-health-and-wellness-survey-nhws

- 18.Dibonaventura MD, Fukuda T, Stankus A. PRM11 evidence for validity of a national patient-reported survey in Japan: the Japan National health and wellness survey. Value in Health 2012;15:A646–7. 10.1016/j.jval.2012.08.262 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, et al. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis 1987;40:373–83. 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Charlson ME, Charlson RE, Peterson JC, et al. The Charlson comorbidity index is adapted to predict costs of chronic disease in primary care patients. J Clin Epidemiol 2008;61:1234–40. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2008.01.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Quan H, Li B, Couris CM, et al. Updating and validating the Charlson comorbidity index and score for risk adjustment in hospital discharge Abstracts using data from 6 countries. Am J Epidemiol 2011;173:676–82. 10.1093/aje/kwq433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kang M-G, Song W-J, Kim H-J, et al. Point prevalence and epidemiological characteristics of chronic cough in the general adult population: the Korean National health and nutrition examination survey 2010-2012. Medicine 2017;96:e6486. 10.1097/MD.0000000000006486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ford AC, Forman D, Moayyedi P, et al. Cough in the community: a cross sectional survey and the relationship to gastrointestinal symptoms. Thorax 2006;61:975–9. 10.1136/thx.2006.060087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bende M, Millqvist E. Prevalence of chronic cough in relation to upper and lower airway symptoms; the Skövde population-based study. Front Physiol 2012;3:251. 10.3389/fphys.2012.00251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Çolak Y, Nordestgaard BG, Laursen LC, et al. Risk factors for chronic cough among 14,669 individuals from the general population. Chest 2017;152:563–73. 10.1016/j.chest.2017.05.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kaushik N, Smith J, Linehan M. Prevalence of chronic cough in a population based survey. European Respiratory Journal 2015;46:PA1139. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lätti AM, Pekkanen J, Koskela HO. Defining the risk factors for acute, subacute and chronic cough: a cross-sectional study in a Finnish adult employee population. BMJ Open 2018;8:e022950. 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-022950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dicpinigaitis PV, Allusson VR, Baldanti A, et al. Ethnic and gender differences in cough reflex sensitivity. Respiration 2001;68:480–2. 10.1159/000050554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Morice AH, Jakes AD, Faruqi S, et al. A worldwide survey of chronic cough: a manifestation of enhanced somatosensory response. Eur Respir J 2014;44:1149–55. 10.1183/09031936.00217813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sternbach N, Annunziata K, Fukuda T, et al. Smoking trends in Japan from 2008-2017: results from the National health and wellness survey. Value in Health 2018;21:S105. 10.1016/j.jval.2018.07.794 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pampel FC. Global patterns and determinants of sex differences in smoking. Int J Comp Sociol 2006;47:466–87. 10.1177/0020715206070267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Barbee RA, Halonen M, Kaltenborn WT, et al. A longitudinal study of respiratory symptoms in a community population sample. correlations with smoking, allergen skin-test reactivity, and serum IgE. Chest 1991;99:20–6. 10.1378/chest.99.1.20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chamberlain SAF, Garrod R, Douiri A, et al. The impact of chronic cough: a cross-sectional European survey. Lung 2015;193:401–8. 10.1007/s00408-015-9701-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Niimi A. Cough associated with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD): Japanese experience. Pulm Pharmacol Ther 2017;47:59–65. 10.1016/j.pupt.2017.05.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Marchesani F, Cecarini L, Pela R, et al. Causes of chronic persistent cough in adult patients: the results of a systematic management protocol. Monaldi Arch Chest Dis 1998;53:510–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kang S-Y, Won H-K, Lee SM, et al. Impact of cough and unmet needs in chronic cough: a survey of patients in Korea. Lung 2019;197:635–9. 10.1007/s00408-019-00258-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee KK, Matos S, Evans DH, et al. A longitudinal assessment of acute cough. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2013;187:991–7. 10.1164/rccm.201209-1686OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang K, Birring SS, Taylor K, et al. Montelukast for postinfectious cough in adults: a double-blind randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Respir Med 2014;2:35–43. 10.1016/S2213-2600(13)70245-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kubo T, Tobe K, Okuyama K, et al. Disease burden and quality of life of patients with chronic cough in Japan: a population-based cross-sectional survey. BMJ Open Respir Res 2021;8:e000764. 10.1136/bmjresp-2020-000764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Good JT, Rollins DR, Kolakowski CA, et al. New insights in the diagnosis of chronic refractory cough. Respir Med 2018;141:103–10. 10.1016/j.rmed.2018.06.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ryan NM, Vertigan AE, Birring SS. An update and systematic review on drug therapies for the treatment of refractory chronic cough. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2018;19:687–711. 10.1080/14656566.2018.1462795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Smith JA, Kitt MM, Morice AH, et al. Gefapixant, a P2X3 receptor antagonist, for the treatment of refractory or unexplained chronic cough: a randomised, double-blind, controlled, parallel-group, phase 2B trial. Lancet Respir Med 2020;8:775–85. 10.1016/S2213-2600(19)30471-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjresp-2020-000832supp001.pdf (119.1KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available on reasonable request.