Abstract

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) has changed the lives of many people across the globe. In addition to the effect of the virus on the biological functions in those infected individuals, many countries have launched government policy with additional impact of these quarantine procedures on the metabolic health of many people worldwide. This mini-review aimed to highlight current evidence regarding the influence of metabolic health due to these quarantine procedures including decrease in physical activity, changes in unhealthy eating habits, increase in stress, and provide recommendations of healthy lifestyle during COVID-19 pandemic.

Keywords: COVID-19 pandemic, Metabolic dysregulation, Quarantine, Preventive measures

1. Introduction

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection causes coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). As of May 4, 2021, 152,502,868 cases and 3,199,110 deaths have been confirmed globally [1]. SARS-CoV-2 induces mild symptoms in the early stage but has the risk of progression to severe illness, including an acute respiratory distress syndrome, and multiorgan failure [2].

Several groups have reported that old age, obesity, diabetes mellitus (DM), cardiovascular disease (CVD), hypertension, and metabolic syndrome are risk factors for fatal and other serious outcomes of COVID-19 [[3], [4], [5]]. From a meta-analysis including 41 studies involving 21,060 individuals infected with COVID-19, patients with male gender, advanced age, smoking history, obesity, DM, hypertension, cancer, coronary heart disease, chronic liver disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), chronic kidney disease are more likely to develop severe COVID-19 symptoms [3]. People with CVD and/or DM had an increased risk of being admitted to intensive care units, requiring mechanical ventilation, or of dying due to SARS-CoV-2 infection [6,7]. Because elevated blood glucose level directly promote SARS-CoV-2 replication, which essentially requires glycolysis in the host [8], patients with high glucose concentration are expected to experience a more serious course of COVID-19 than their counterparts with a normal glucose level [4]. Moreover, metabolic derangement induces host immune dysregulation and pro-inflammatory milieu, leading to increased severity and mortality in COVID-19 due to vasculopathy, coagulopathy, and thrombosis [9]. Nonetheless, from another meta-analysis including 7 studies, there was no significant association found between DM and severe COVID [10]. It was found that older age, dyspnoea, COPD, CVD and HT were predictive factors of severe COVID [10].

2. Impact of COVID-19 and related quarantine procedures on metabolic risk

2.1. Current evidence

During the COVID-19 pandemic, many countries have launched the government policy to follow quarantine measures, including the closure of exercise facilities and movement restriction. Several countries reinforced these measures to shutting down public facilities such as sports centers, and suspending school attendance. The public was requested to refrain from going outside unnecessarily, and to keep 1–2 m distance from others in public places [11]. Owing to these preventive measures, the number of daily new cases of COVID-19 in many countries fell substantially.

However, this policy seems to impose an adverse effect on metabolic control of many people across the globe [12]. The preventive measures initiated as a response to the COVID-19 pandemic, such as preventing people from going outdoors and shutting down exercise facilities, are likely to have a negative influence on lifestyle and behaviors [13], which can adversely impact on energy homeostasis [14,15].

A recent study published in Primary Care Diabetes investigated the impact of prolonged COVID-19 lockdown on metabolic parameters in patients with DM and healthy individuals in Turkey with the study participants in their fifties and being either overweight or obese [16]. After the initiation of lockdown procedures, there was a trend of increase in body weight more in DM than non-DM groups (1.91 ± 5.48 kg vs 0.54 ± 0.95 kg, p > 0.05). Increase in waist circumference was more in DM compared with non-DM participants (1.20 ± 2.38 cm vs 0.03 ± 0.46 cm, p < 0.05). Glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) was found to have increased more in people with DM compared to non-DM counterparts (0.71 ± 1.35% vs. 0.02 ± 0.19%, p < 0.05). Serum LDL-cholesterol and triglycerides also increased in the DM group (7.6 ± 34.3 mg/dl and 58.2 ± 133.5 mg/dl, p < 0.05) whereas non-significantly decreased in non-DM group (−3.5 ± 14.5 mg/dl and −6.5 ± 41.8 mg/dl), respectively. This study has demonstrated the negative effect on metabolic control in DM associated with the lockdown procedure in fighting the COVID-19 pandemic.

The impact of COVID-19 and associated preventive measures on metabolic profiles were also investigated in South Korea [17], using data from 1485 patients (mean age of 61.8 ± 11.7 years) who attended a tertiary hospital at least twice a year, in the past four years. Changes in metabolic parameters from the COVID-19 pandemic (2019–2020) were compared with the same time points during the previous seasons of 2016–2019 [17]. The lipid profiles worsened in the pandemic period compared with the previous years [17]. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the overall rate of metabolic syndrome increased significantly by 21% compared with the period in 2018–2019. Body mass index increased by 0.09 ± 1.16 kg/m2 in the 2019–2020 pandemic period, whereas it decreased by –0.39 ± 3.03 kg/m2 in 2018–2019 and by –0.34 ± 2.18 kg/m2 in 2017–2018 (both p < 0.05). Systolic blood pressure increased by 2.6 ± 18.2 mmHg in the COVID-19 pandemic period, while it decreased in the three antecedent seasons (p < 0.05 for the COVID-19 period vs all previous periods).

By contrast, other studies did not observe any impact of lockdown on glycemic control [[18], [19], [20], [21], [22]]. Indeed, deterioration of glycemia in DM even without a national lockdown has been reported [23]. In a short-term observational study in the Netherlands, 435 people with DM (280 type 1 DM and 155 type 2 DM) HbA1c 8–11 weeks after the start of lockdown measures compared to before showed no deterioration of glycemic control but increase in perceived stress and anxiety, weight gain and less exercise [18]. In a retrospective study in Italy (128 type 2 DM) investigating the effect of lockdown (9 March 2020 to 18 May 2020), there was significant increase in body mass index, fasting plasma glucose and HbA1c with insulin therapy being the only significant predictor of worsening of HbA1c [19]. From the results of another study done in Italy including 304 type 2 DM with mean age of 69 years, home confinement related to COVID-19 lockdown did not exert any significant impact on fasting plasma glucose and HbA1c [20]. Similarly, according to the results of 110 type 2 DM from India also did not show any significant changes in body weight and HbA1c [21]. From a study in Japan involving review of electronic medical records in 1009 type 2 DM between January 2019 and August 2020 through comparison of HbA1c before and after COVID-19 outbreak, HbA1c significantly increased from 7.45% to 7.53% even though there was no policy of national lockdown during the period [23]. From another study in Japan which was a cross-sectional, retrospective cohort study with 203 type 2 DM included, it was reported that stress and lifestyle changes related to COVID-19 pandemic were linked with increased body weight and HbA1c [22].

2.2. Decrease in physical activity

Preventive measures against the COVID-19 outbreak are implemented in many countries. These include social distancing, telecommuting, remote classes, working from home and closure of exercise facilities, such as community centers, private gyms, swimming pools, and parks. These measures inevitably reduce physical activity in many individuals, particularly in people who have underlying metabolic dysregulation. Of note, physical distancing does not equal to physical inactivity and the decrease in physical activity related to home confinement secondary to COVID-19 outbreak should call for more public attention [24]. According to a mobile big data, because of the social distancing policy, personal movement of the general public in South Korea decreased by 38.1% in the 4th week of the COVID-19 outbreak (February 24–March 1, 2020), compared with the period before a confirmed COVID-19 case was identified (January 9–22, 2020) [25]. A recent self-reporting survey showed that people spent more time at home and gained weight during the COVID-19 pandemic [26]. It has been reported that decreased physical activities related to the COVID-19 pandemic contributed to aggravation in insulin resistance and increase in body weight [27]. Of note, the influence of COVID-19 on physical activity may vary in different countries. For instance, in Finland, a less densely populated country, a lot of outdoor activities such as trekking, cross-country skiing, and gardening have increased significantly, because these can be done with a distance from others and the country did not have a complete lockdown albeit many restrictions related to indoor activities were introduced. From a survey done among parents in the United States (US), it is evident that equitable access to outdoor spaces and play equipment generally support children’s physical activity during shelter-in-place mandate due to COVID-19 epidemic [28]. A decrease in outdoor activities and an increase in time spent using the internet and social network services, playing online games, and watching television may also result in a harmful impact on their eating habit [29]. An international online survey, which was intended to investigate the behavioral and lifestyle consequences of COVID-19 restrictions, reported that the COVID-19 related home confinement had resulted in an unfavorable effect on physical activity and food consumption pattern [55]. Thus, preventive measures against the COVID-19 outbreak may aggravate a sedentary lifestyle and unhealthy diet among the general public. In fact, according to the Community Mobility Reports released by Google (https://www.google.com/covid19/mobility/?hl=en-GB), the people’s moving trends are decreasing in many countries during the COVID-19 pandemic.

2.3. Changes into unfavorable diet pattern

During the COVID-19 pandemic, social activities have been discouraged and exercise facilities have been closed. Under these restrictions, tailored lifestyle modifications such as home exercise training and cooking of healthy food are encouraged [5]. Notably, preventive measures against COVID-19 such as staying at home and school closures, may limit people's access to healthy food [12]. Based on the data obtained from the delivery apps in Korea, the number of food deliveries increased by 11% during February 1–16, compared with January 6–21, after the COVID-19 spread across the country (https://pulsenews.co.kr/view.php?sc=30800022&year=2020&no=176494). In general, fast foods such as pizza, fried chicken, French fries, and sugar sweetened beverages are popular delivery foods [30]. These foods are metabolically unhealthy compared to homemade fresh foods [31]. The increasing consumption of these foods increases energy density and high glycemic load [32,33], resulting in obesity, DM and metabolic syndrome [33,34].

Another important issue is nutrition of students in many countries. Schools in many countries have been closed for several months. Under this situation, no access to school lunch and lack of supervision from teachers and parents (who are often working) for their food choices and dietary habits is another factor to consider [35]. On the other hand, in some countries such as Finland, school kitchens provide take-away food for pupils during distance-learning. The impact resulted from the differences in practice and policy among different countries worldwide remain to be examined.

2.4. Changes in mental health: stress and depression

Furthermore, COVID-19 pandemic is exerting a negative influence on mental health [36]. Many people have been psychologically distressed due to a fear of infection or dying, and such distress can induce systemic inflammation [15]. In addition, limited access to exercise facilities and disruption of human relationships increase psychological stress, which can lead to elevations in blood pressure and dysregulation of glucose metabolism by releasing stress-related hormones such as cortisol and catecholamines [37]. The sympathetic system is activated with increased levels of catecholamines after catastrophic events, which influences the cardiovascular system negatively [38]. In metabolic dysregulated status, the renin–angiotensin-aldosterone system is also activated inappropriately, which leads to increased production of angiotensin II and elevated plasma renin activity, which in turn contributes to increasing blood pressure and deteriorating glucose metabolism [39].

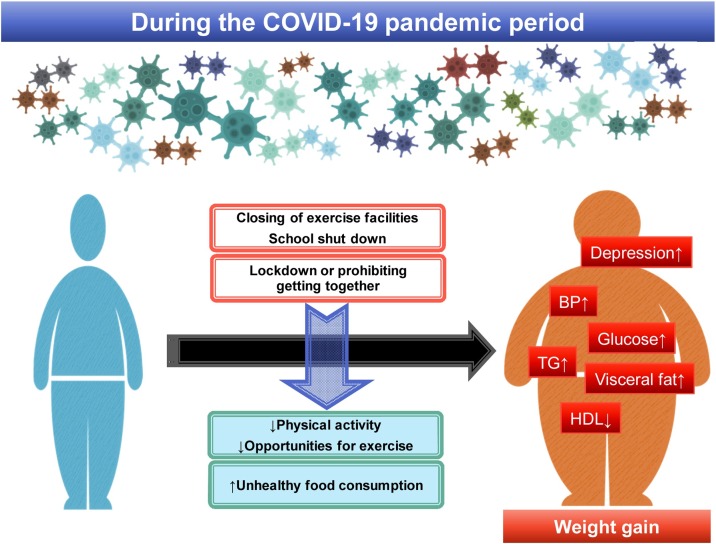

A recent study reported that prevalence of depression symptoms in US adults was more than three times higher during COVID-19 compared with before the COVID-19 pandemic [40]. People with lower economic resources and insufficient social support reported a greater burden of depression symptoms. Increase in frequency of mental illness is anticipated to come, particularly among at-risk populations in COVID-19 era. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic and related quarantine procedures on metabolic and mental health is summarized in Fig. 1 .

Fig. 1.

Impact of COVID-19 pandemic and related quarantine procedures on metabolic and mental health.

Abbreviations: BP, blood pressure; HDL, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; TG, triglycerides.

3. Diagnosis of diabetes and non-diabetic hyperglycemia in patients with COVID-19

It is well-known that a large proportion of people with type 2 DM are unrecognized in the population [41] and in patients with severe disease such as CVD [42]. Similarly, newly diagnosed DM is commonly observed in patients with COVID-19 according to the recent meta-analysis [43]. Several studies have shown that compared to people with normal blood glucose, those with newly diagnosed DM had higher mortality and a more severe disease prognosis when suffering from COVID-19 infection [43]. For instance, in China, mortality was increased 10-fold in people newly diagnosed DM while those with pre-existing DM had only a 5-fold risk of death [44]. Compared to patients with normal glucose, those with impaired fasting glucose also developed more severe primary composite end-point events; 5% and 18%, respectively. Also other studies have revealed that prediabetes is associated with serious outcomes of COVID-19 [45]. Among COVID-19 patients in US, 42% of those with newly diagnosed DM died during hospitalization compared to 15% of those with pre-existing DM [46].

Satish et al. recommended that “Clinicians need to be aware of these issues and should screen all COVID-19 patients with blood glucose and HbA1c at the time of admission, irrespective of their prior DM history, and closely monitor their glycemia status [47]”. Optimal glycemic control is crucial in the COVID-19 era and improves prognosis. Management of patients with diabetes and COVID-19 is challenging. Prevention and treatment strategies are urgently required to decrease morbidity and mortality in this high-risk population [48].

People diagnosed with COVID-19 not admitted to hospital should assess their own DM risk using existing non-laboratory DM risk scores [49] and if the risk is elevated consult their primary care clinics to have glycemia testing done. Generally, fating glucose, post-load 2 h glucose during 75-g oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT), and HbA1c are equally appropriate for diagnostic screening according to American Diabetes Association Guideline 2021 [50]. OGTT is known to be the most sensitive method to identify undiagnosed DM and the only way to detect impaired glucose tolerance [41] and recommended by WHO as gold standard [51]. For very high-risk people such as those with COVID-19 it is important to apply the most sensitive method, similarly, as recommended in people with CVD [52].

4. Practical consideration

Given the deterioration in metabolic profiles during the COVID-19 pandemic, healthcare providers should pay special attention on at-risk individuals in order to prevent future adverse cardiovascular events. Elevated release of cytokines in metabolic derangement is likely to provoke a “cytokine storm” in those individuals infected with SARS-CoV-2, which may lead to multiorgan failure [53]. To combat COVID-19 and its related quarantine procedures, governments and authorized medical societies must work together to promote regular exercises, healthy eating, and mental health promotion activities during this difficult period. Social media or web-based programs can provide convenient tools to guide people in achieving healthy lifestyle albeit the restricts imposed by COVID-19. Active counseling to help people coping with barriers against healthier lifestyles would be helpful in this critical situation [54]. Unfortunately, many resources in primary health care have been restricted due to the COVID-19 pandemic and new technology such as telemedicine may shed light on improving support to patients.

5. Conclusion

COVID-19 pandemic and its preventive measures impact negatively on metabolic profiles in a huge number of people worldwide. Decreased physical activity and unhealthy dietary patterns linked to preventive principles such as social distancing and lockdown appear to be the key factors mediating the negative influence. More studies including socioeconomic factors, degree of quarantine measures and its adherence are warranted to identify the long-term influence of these procedures on metabolic profile. Of note, individuals at high metabolic risk are more vulnerable to SARS-CoV-2 infection and have an increased morbidity and mortality rates compared with those without.

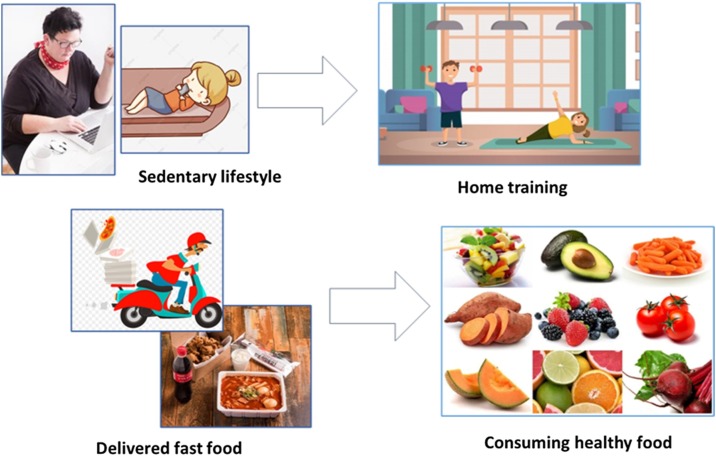

Taken together, during the COVID-19 pandemic and associated preventive procedures, nationwide strategies to maintain cardiometabolic health are necessary. Promotional activities on doing regular physical activity and consuming healthy food are strongly recommended to mitigate the unfavorable impact of COVID-19 and the related quarantine protocol on metabolic risks (Fig. 2 ). In this light, the role of primary health care workers for diabetes prevention and care is pivotal in management of people with DM, as well as those at risk of DM. Identification of previously undiagnosed DM and prediabetes among people with COVID-19 infection is essential. It is of utmost importance to be vigilant to evaluate the long-term impact on care practices worldwide after the pandemic is over.

Fig. 2.

Recommendations for healthy lifestyle during COVID-19 pandemic.

Conflict of interest

None.

Financial support

None.

References

- 1.Liu C., Feng X., Li Q., Wang Y., Li Q., Hua M. Adiponectin, TNF-alpha and inflammatory cytokines and risk of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cytokine. 2016;86:100–109. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2016.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wu Z., McGoogan J.M. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: summary of a report of 72314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA. 2020;323:1239–1242. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li X., Zhong X., Wang Y., Zeng X., Luo T., Liu Q. Clinical determinants of the severity of COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2021;16 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0250602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lim S., Bae J.H., Kwon H.S., Nauck M.A. COVID-19 and diabetes mellitus: from pathophysiology to clinical management. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2021;17:11–30. doi: 10.1038/s41574-020-00435-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lim S., Shin S.M., Nam G.E., Jung C.H., Koo B.K. Proper management of people with obesity during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Obes. Metab. Syndr. 2020;29:84–98. doi: 10.7570/jomes20056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guan W.J., Ni Z.Y., Hu Y., Liang W.H., Ou C.Q., He J.X., Liu L., Shan H., Lei C.L., Hui D.S.C., Du B., Li L.J., Zeng G., Yuen K.Y., Chen R.C., Tang C.L., Wang T., Chen P.Y., Xiang J., Li S.Y., Wang J.L., Liang Z.J., Peng Y.X., Wei L., Liu Y., Hu Y.H., Peng P., Wang J.M., Liu J.Y., Chen Z., Li G., Zheng Z.J., Qiu S.Q., Luo J., Ye C.J., Zhu S.Y., Zhong N.S., C. China Medical Treatment Expert Group for Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382:1708–1720. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bello-Chavolla O.Y., Bahena-Lopez J.P., Antonio-Villa N.E., Vargas-Vazquez A., Gonzalez-Diaz A., Marquez-Salinas A., Fermin-Martinez C.A., Naveja J.J., Aguilar-Salinas C.A. Predicting mortality due to SARS-CoV-2: a mechanistic score relating obesity and diabetes to COVID-19 outcomes in Mexico. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2020;105 doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgaa346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Codo A.C., Davanzo G.G., Monteiro L.B., de Souza G.F., Muraro S.P., Virgilio-da-Silva J.V., Prodonoff J.S., Carregari V.C., de Biagi Junior C.A.O., Crunfli F., Jimenez Restrepo J.L., Vendramini P.H., Reis-de-Oliveira G., Bispo Dos Santos K., Toledo-Teixeira D.A., Parise P.L., Martini M.C., Marques R.E., Carmo H.R., Borin A., Coimbra L.D., Boldrini V.O., Brunetti N.S., Vieira A.S., Mansour E., Ulaf R.G., Bernardes A.F., Nunes T.A., Ribeiro L.C., Palma A.C., Agrela M.V., Moretti M.L., Sposito A.C., Pereira F.B., Velloso L.A., Vinolo M.A.R., Damasio A., Proenca-Modena J.L., Carvalho R.F., Mori M.A., Martins-de-Souza D., Nakaya H.I., Farias A.S., Moraes-Vieira P.M. Elevated glucose levels favor SARS-CoV-2 infection and monocyte response through a HIF-1alpha/glycolysis-dependent axis. Cell Metab. 2020;32:437–446. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2020.07.007. e435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bansal R., Gubbi S., Muniyappa R. Metabolic syndrome and COVID 19: endocrine-immune-vascular interactions shapes clinical course. Endocrinology. 2020;161 doi: 10.1210/endocr/bqaa112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jain V., Yuan J.M. Predictive symptoms and comorbidities for severe COVID-19 and intensive care unit admission: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Public Health. 2020;65:533–546. doi: 10.1007/s00038-020-01390-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ministry of Health and Welfare; 2020. Stronger Social Distancing for 15 Days, Starting With the Government! [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lim S., Lim H., Despres J.P. Collateral damage of the COVID-19 pandemic on nutritional quality and physical activity: perspective from South Korea. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2020;28:1788–1790. doi: 10.1002/oby.22935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Di Renzo L., Gualtieri P., Pivari F., Soldati L., Attina A., Cinelli G., Leggeri C., Caparello G., Barrea L., Scerbo F., Esposito E., De Lorenzo A. Eating habits and lifestyle changes during COVID-19 lockdown: an Italian survey. J. Transl. Med. 2020;18:229. doi: 10.1186/s12967-020-02399-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mattioli A.V., Ballerini Puviani M., Nasi M., Farinetti A. COVID-19 pandemic: the effects of quarantine on cardiovascular risk. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2020;74:852–855. doi: 10.1038/s41430-020-0646-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mattioli A.V., Nasi M., Cocchi C., Farinetti A. COVID-19 outbreak: impact of the quarantine-induced stress on cardiovascular disease risk burden. Future Cardiol. 2020;16:539–542. doi: 10.2217/fca-2020-0055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Karatas S., Yesim T., Beysel S. Impact of lockdown COVID-19 on metabolic control in type 2 diabetes mellitus and healthy people. Prim. Care Diabetes. 2021;15:424–427. doi: 10.1016/j.pcd.2021.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sohn M., Koo B.K., Yoon H.I., Song K.H., Kim E.S., Kim H.B., Lim S. Impact of COVID-19 and associated preventive measures on Cardiometabolic Rksk Factors in South Korea. J. Obes. Metab. Syndr. 2021 doi: 10.7570/jomes21046. Online ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ruissen M.M., Regeer H., Landstra C.P., Schroijen M., Jazet I., Nijhoff M.F., Pijl H., Ballieux B., Dekkers O., Huisman S.D., de Koning E.J.P. Increased stress, weight gain and less exercise in relation to glycemic control in people with type 1 and type 2 diabetes during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMJ Open Diabetes Res. Care. 2021;9 doi: 10.1136/bmjdrc-2020-002035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Biamonte E., Pegoraro F., Carrone F., Facchi I., Favacchio G., Lania A.G., Mazziotti G., Mirani M. Weight change and glycemic control in type 2 diabetes patients during COVID-19 pandemic: the lockdown effect. Endocrine. 2021;72:604–610. doi: 10.1007/s12020-021-02739-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Falcetta P., Aragona M., Ciccarone A., Bertolotto A., Campi F., Coppelli A., Dardano A., Giannarelli R., Bianchi C., Del Prato S. Impact of COVID-19 lockdown on glucose control of elderly people with type 2 diabetes in Italy. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2021;174 doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2021.108750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sankar P., Ahmed W.N., Mariam Koshy V., Jacob R., Sasidharan S. Effects of COVID-19 lockdown on type 2 diabetes, lifestyle and psychosocial health: a hospital-based cross-sectional survey from South India. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. 2020;14:1815–1819. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Munekawa C., Hosomi Y., Hashimoto Y., Okamura T., Takahashi F., Kawano R., Nakajima H., Osaka T., Okada H., Majima S., Senmaru T., Nakanishi N., Ushigome E., Hamaguchi M., Yamazaki M., Fukui M. Effect of coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic on the lifestyle and glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes: a cross-section and retrospective cohort study. Endocr. J. 2021;68:201–210. doi: 10.1507/endocrj.EJ20-0426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tanji Y., Sawada S., Watanabe T., Mita T., Kobayashi Y., Murakami T., Metoki H., Akai H. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on glycemic control among outpatients with type 2 diabetes in Japan: a hospital-based survey from a country without lockdown. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2021;176 doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2021.108840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Meyer S.M., Landry M.J., Gustat J., Lemon S.C., Webster C.A. Physical distancing not equal physical inactivity. Transl. Behav. Med. 2021;11:941–944. doi: 10.1093/tbm/ibaa134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Park I.N., Yum H.K. Stepwise strategy of social distancing in Korea. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2020;35:e264. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2020.35.e264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zachary Z., Brianna F., Brianna L., Garrett P., Jade W., Alyssa D., Mikayla K. Self-quarantine and weight gain related risk factors during the COVID-19 pandemic. Obes. Res. Clin. Pract. 2020;14:210–216. doi: 10.1016/j.orcp.2020.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Martinez-Ferran M., de la Guia-Galipienso F., Sanchis-Gomar F., Pareja-Galeano H. Metabolic impacts of confinement during the COVID-19 pandemic due to modified diet and physical activity habits. Nutrients. 2020;12 doi: 10.3390/nu12061549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Perez D., Thalken J.K., Ughelu N.E., Knight C.J., Massey W.V. Nowhere to go: parents’ descriptions of children’s physical activity during a global pandemic. Front. Public Health. 2021;9 doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.642932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pearson N., Biddle S.J. Sedentary behavior and dietary intake in children, adolescents, and adults. A systematic review. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2011;41:178–188. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim T.H., Park Y., Myung J., Han E. Food price trends in South Korea through time series analysis. Public Health. 2018;165:67–73. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2018.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fleischhacker S.E., Evenson K.R., Rodriguez D.A., Ammerman A.S. A systematic review of fast food access studies. Obes. Rev. 2011;12:e460–471. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2010.00715.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Prentice A.M., Jebb S.A. Fast foods, energy density and obesity: a possible mechanistic link. Obes. Rev. 2003;4:187–194. doi: 10.1046/j.1467-789x.2003.00117.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pereira M.A., Kartashov A.I., Ebbeling C.B., Van Horn L., Slattery M.L., Jacobs D.R., Jr., Ludwig D.S. Fast-food habits, weight gain, and insulin resistance (the CARDIA study): 15-year prospective analysis. Lancet. 2005;365:36–42. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17663-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Duffey K.J., Gordon-Larsen P., Jacobs D.R., Jr., Williams O.D., Popkin B.M. Differential associations of fast food and restaurant food consumption with 3-y change in body mass index: the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults Study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2007;85:201–208. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/85.1.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bogl L.H., Mehlig K., Ahrens W., Gwozdz W., de Henauw S., Molnar D., Moreno L., Pigeot I., Russo P., Solea A., Veidebaum T., Kaprio J., Lissner L., Hebestreit A., on behalf of the IDEFICS and I. Family Consortia Like me, like you - relative importance of peers and siblings on children’s fast food consumption and screen time but not sports club participation depends on age. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2020;17:50. doi: 10.1186/s12966-020-00953-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rajkumar R.P. COVID-19 and mental health: a review of the existing literature. Asian J. Psychiatr. 2020;52 doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stephens M.A., Wand G. Stress and the HPA axis: role of glucocorticoids in alcohol dependence. Alcohol Res. 2012;34:468–483. doi: 10.35946/arcr.v34.4.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mattioli A.V., Sciomer S., Cocchi C., Maffei S., Gallina S. Quarantine during COVID-19 outbreak: changes in diet and physical activity increase the risk of cardiovascular disease. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2020;30:1409–1417. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2020.05.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cabandugama P.K., Gardner M.J., Sowers J.R. The Renin Angiotensin Aldosterone System in obesity and hypertension: roles in the Cardiorenal Metabolic syndrome. Med. Clin. North Am. 2017;101:129–137. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2016.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ettman C.K., Abdalla S.M., Cohen G.H., Sampson L., Vivier P.M., Galea S. Prevalence of depression symptoms in US adults before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw. Open. 2020;3 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.19686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Glucose tolerance and mortality: comparison of WHO and American Diabetes Association diagnostic criteria. The DECODE study group. European Diabetes Epidemiology Group. Diabetes epidemiology: collaborative analysis of diagnostic criteria in Europe. Lancet. 1999;354:617–621. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gyberg V., De Bacquer D., Kotseva K., De Backer G., Schnell O., Sundvall J., Tuomilehto J., Wood D., Ryden L., Investigators E.I. Screening for dysglycaemia in patients with coronary artery disease as reflected by fasting glucose, oral glucose tolerance test, and HbA1c: a report from EUROASPIRE IV—a survey from the European Society of Cardiology. Eur. Heart J. 2015;36:1171–1177. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sathish T., Kapoor N., Cao Y., Tapp R.J., Zimmet P. Proportion of newly diagnosed diabetes in COVID-19 patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2021;23:870–874. doi: 10.1111/dom.14269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li H., Tian S., Chen T., Cui Z., Shi N., Zhong X., Qiu K., Zhang J., Zeng T., Chen L., Zheng J. Newly diagnosed diabetes is associated with a higher risk of mortality than known diabetes in hospitalized patients with COVID-19. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2020;22:1897–1906. doi: 10.1111/dom.14099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sathish T., Cao Y. Is newly diagnosed diabetes as frequent as preexisting diabetes in COVID-19 patients? Diabetes Metab. Syndr. 2021;15:147–148. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.12.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bode B., Garrett V., Messler J., McFarland R., Crowe J., Booth R., Klonoff D.C. Glycemic characteristics and clinical outcomes of COVID-19 patients hospitalized in the United States. J. Diabetes Sci. Technol. 2020;14:813–821. doi: 10.1177/1932296820924469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sathish T., Cao Y., Kapoor N. Newly diagnosed diabetes in COVID-19 patients. Prim. Care Diabetes. 2021;15:194. doi: 10.1016/j.pcd.2020.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Papadokostaki E., Tentolouris N., Liberopoulos E. COVID-19 and diabetes: what does the clinician need to know? Prim. Care Diabetes. 2020;14:558–563. doi: 10.1016/j.pcd.2020.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schwarz P.E., Li J., Lindstrom J., Tuomilehto J. Tools for predicting the risk of type 2 diabetes in daily practice. Horm. Metab. Res. 2009;41:86–97. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1087203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.American Diabetes A. 2. Classification and diagnosis of diabetes: standards of medical care in Diabetes-2021. Diabetes Care. 2021;44:S15–S33. doi: 10.2337/dc21-S002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Alberti K.G., Zimmet P.Z. Definition, diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus and its complications. Part 1: diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus provisional report of a WHO consultation. Diabet. Med. 1998;15:539–553. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9136(199807)15:7<539::AID-DIA668>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cosentino F., Grant P.J., Aboyans V., Bailey C.J., Ceriello A., Delgado V., Federici M., Filippatos G., Grobbee D.E., Hansen T.B., Huikuri H.V., Johansson I., Juni P., Lettino M., Marx N., Mellbin L.G., Ostgren C.J., Rocca B., Roffi M., Sattar N., Seferovic P.M., Sousa-Uva M., Valensi P., Wheeler D.C., Group E.S.C.S.D. 2019 ESC guidelines on diabetes, pre-diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases developed in collaboration with the EASD. Eur. Heart J. 2020;41:255–323. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Michalakis K., Ilias I. SARS-CoV-2 infection and obesity: common inflammatory and metabolic aspects. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. 2020;14:469–471. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.04.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Patnode C.D., Evans C.V., Senger C.A., Redmond N., Lin J.S. Behavioral counseling to promote a healthful diet and physical activity for cardiovascular disease prevention in adults without known cardiovascular disease risk factors: updated evidence report and systematic review for the US preventive services task force. JAMA. 2017;318:175–193. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.3303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ammar A., Brach M., Trabelsi K., Chtourou H., Boukhris O., Masmoudi L., Bouaziz B., Bentlage E., How D., Ahmed M., Muller P., Muller N., Aloui A., Hammouda O., Paineiras-Domingos L.L., Braakman-Jansen A., Wrede C., Bastoni S., Pernambuco C.S., Mataruna L., Taheri M., Irandoust K., Khacharem A., Bragazzi N.L., Chamari K., Glenn J.M., Bott N.T., Gargouri F., Chaari L., Batatia H., Ali G.M., Abdelkarim O., Jarraya M., Abed K.E., Souissi N., Van Gemert-Pijnen L., Riemann B.L., Riemann L., Moalla W., Gomez-Raja J., Epstein M., Sanderman R., Schulz S.V., Jerg A., Al-Horani R., Mansi T., Jmail M., Barbosa F., Ferreira-Santos F., Simunic B., Pisot R., Gaggioli A., Bailey S.J., Steinacker J.M., Driss T., Hoekelmann A. Effects of COVID-19 home confinement on eating behaviour and physical activity: results of the ECLB-COVID19 international online survey. Nutrients. 2020;12 doi: 10.3390/nu12061583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]