Abstract

The antimicrobial resistant strains of several pathogens are major culprits of hospital-acquired nosocomial infections. An active and urgent action is necessary against these pathogens for the development of unique therapeutics. The cysteine biosynthetic pathway or genes (that are absent in humans) involved in the production of L-cysteine appear to be an attractive target for developing novel antibiotics. CysE, a Serine Acetyltransferase (SAT), catalyzes the first step of cysteine synthesis and is reported to be essential for the survival of persistence in several microbes including Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Structure determination provides fundamental insight into structure and function of protein and aid in drug design/discovery efforts. This review focuses on the overview of current knowledge of structure function, regulatory mechanism, and potential inhibitors (active site as well as allosteric site) of CysE. Despite having conserved structure, slight modification in CysE structure lead to altered the regulatory mechanism and hence affects the cysteine production. Due to its possible role in virulence and vital metabolism of pathogens makes it a potential target in the quest to develop novel therapeutics to treat multi-drug-resistant bacteria.

Keywords: Antimicrobial resistance, Cysteine biosynthetic pathway, CysE/SAT, L-cysteine, Structure–function, Regulatory mechanism, Inhibitor

Introduction

Emergence of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) among strains of several pathogenic bacteria poses a global threat (Yoneyama and Katsumata 2006; Fischbach and Walsh 2009; Gandra et al. 2014). The narrowing pipeline of drugs available to treat infections caused by multi-drug-resistant (MDR) Gram-negative pathogens alarms a serious cause of concern. These pathogens include the infamous Enterobacteriaceae family (Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Enterobacter spp., Serratia spp., Proteus spp., Providencia spp. and Morganella spp.), Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Acinetobacter baumannii, Salmonella spp., and Shigella spp., that are major culprits of hospital-acquired nosocomial infections. In addition, Gram-positive bacteria like Streptococcus pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus, and Mycobacterium tuberculosis among others add to the priority list of WHO (Tacconelli et al. 2018). Although the true disease burden due to AMR is largely unknown, statistics released figures are indicative of nearly 700,000 yearly deaths, with the cumulative figure expected to touch 10 million deaths by 2050, posing an economic burden of USD 100 trillion to the world (Gandra et al. 2014). It takes into account the secondary effects of AMR predicts that the common surgeries such as cesareans, organ transplants, and joint replacements as well as cancer chemotherapy that contributes 4% (worth at least 120 trillion USD between now and 2050) to the world’s GDP will be at risk and combining with other effects, the total cost due to dearth of effective antibiotics may touch USD 210 trillion by 2050 (The Review on Antimicrobial Resistance 2014).

A major contributor to the global burden of AMR, studies envisage India to home 2 million of the 10 million projected deaths by 2050, which is exacerbated by high incidence of diseases like tuberculosis, malaria, and HIV are major (The Review on Antimicrobial Resistance 2014; Gelband et al. 2015; Gandra et al. 2017) According to a report prepared by team members of Center for Disease Dynamics, Economics & Policy (CDDEP), India, resistance rate of some of the common infectious agents (in community as well as healthcare settings) to broad-spectrum antibiotics such as fluoroquinolones and third-generation cephalosporins is the highest in India. In fact, greater than 80% resistance is observed in extended spectrum β-lactamases (ESBL) producers, while greater than 50% seen in Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacteriacae (CRE) and 47% in Methicillin-Resistant S. aureus (MRSA) in India (Gandra et al. 2017). AMR is a multi-dimensional problem and the major causative factors responsible for the development of high antibiotic resistance in India include, but are not limited to nonchalant prescription of antibiotics, self medication, poor infection controls in hospitals, patients not completing their antibiotic dose, over-use of antibiotics in livestocks, poor hygiene and sanitation, unregulated release of pharmaceutical effluents (The Review on Antimicrobial Resistance 2014; Laxminarayan and Chaudhury 2016; Dixit et al. 2019; Taneja and Sharma 2019). It is imperative to understand and address all these factors to effectively counter the threat resulting in high morbidity and mortality among the population, along with inflaming economic losses (Dixit et al. 2019).

The evolution of MDR pathogens due to the extensive use/misuse of antibiotics has superseded the discovery of new antimicrobials bringing us to brink of pre-antibiotic era, where the world is facing again the dearth of effective medicines for treating common microbial infections (such as diarrhea, tuberculosis, malaria, gonorrhea, etc.) (Simpkin et al. 2017; The Pew Charitable Trusts and Trusts 2017) (Projan 2003; Power 2006; Fair and Tor 2014). Paradoxically, antibiotics selective pressure induces natural ability of microbes to mutate and develop resistance. For reducing bacterial adaptation to this selective pressure, scientific community for the past decade has been working on targeting non-essential virulence processes such as quorum sensing, bacterial adhesion, etc. The agenda is to reduce pathogenesis rather than compromising the pathogen’s survival, attributing a major cause for development of drug-resistant strains (Monserrat-Martinez et al. 2019). Most of the pathogenic bacteria reside in extremely harsh conditions within host environment (such as gastric mucosa, macrophages, etc.), where they employ adaptation strategies for multiplication and survival. Sulfur containing compounds like glutathione, thiamine, Fe–S cluster, and biotin corroborate this adaptation due to their reducing and detoxifying properties. Moreover, cysteine, a sulfur-containing amino acid, is a major constituent of proteins, antioxidants, cofactors, vitamins, and metal clusters, thereby highlighting prevention of cysteine formation as a promising antibacterial target (Leustek et al. 2000; Ishikawa and Mino 2012). Cysteine-derived antioxidants, glutathione, and mycothiols play a critical role in protecting cells against oxidative stress (Noji and Saito 2003; Bhave et al. 2007). Eukaryotes and Gram-negative organisms use antioxidant glutathione, whereas Gram-positive bacteria such as M. tuberculosis (Mtb) employ mycothiol to maintain redox balance against reactive oxygen species as a first line of defense (Sassetti and Rubin 2003; Liu et al. 2013). Cysteine is required for several cellular activities and metabolic functions for Entamoeba histolytica (Gillin and Diamond 1980; Kumar et al. 2011). Cysteine is also reported to be essential in Salmonella typhimurium for its growth and survival (Turnbull and Surette 2010). If formation of cysteine is blocked, then pathogenic microbes will not able to survive without cysteine, and hence, targeting de novo cysteine biosynthetic pathway may be a promising approach for discovery of novel antimicrobials.

In de novo cysteine biosynthetic pathway, cysteine is synthesized from serine in two steps. The first step involves conversion of serine into O-acetyl serine (OAS) by transfer of acetyl group from acetyl CoA to the serine, catalyzed in the presence of the enzyme serine acetyl transferase (SAT), or CysE. The second step is catalyzed by the enzyme O-acetyl serine sulfhydralase (OASS), or CysK where OAS is converted into cysteine in the presence of sulfide (Kredich and Tomkins 1966; Smith and Thompson 1971; Ishikawa and Mino 2012). This enzyme has already been reviewed recently by our group members and will not be discussed herein (Joshi et al. 2019). CysE, the first enzyme of bacterial cysteine biosynthetic pathway, is documented to be important for infections by E. coli (Zhang and Lin 2009), Hemophilus influenza (Akerley et al. 2002), S. aureus (Chaudhuri et al. 2009), and Bacillus subtilis (Kobayashi et al. 2003). CysE is reported to be essential for the survival of M. tuberculosis during persistent phase in vivo growth (Sassetti et al. 2003; Sassetti and Rubin 2003; Rengarajan et al. 2005). CysE is also important in Serratia marcescens, an opportunistic pathogen that required CysE for flagellar transport and phospholipase/lecithinase activity (Anderson et al. 2017). Cysteine is also a component of the antioxidant trypanothione required for trypanosomatids responsible for parasitic survival (Williams et al. 2009; Ramos 2014). Owing to the importance of cysteine de novo synthetic pathway and vital role of CysE in pathogenesis of several microbes, this review attempts to compile recent advances in the structural–functional data available for novel drug target CysE, so as to facilitate drug discovery process. Although limited, some inhibitors have been identified against this drug target and the state-of-art regarding available CysE inhibitors is also included in the review.

Cysteine biosynthetic pathway in different domains

Cysteine is a non-essential amino acid in microorganisms, as it is endogenously synthesized through two major biosynthetic pathways, namely (i) reverse trans-sulfuration pathway in humans involving cystathionine intermediate; (ii) sulfhydralase pathway in bacteria and plants necessitating sulfide.

In humans, cysteine is synthesized from methionine (Fig. 1). In this pathway, L-methionine is converted to homocysteine through series of reactions that is further converted into L-cystathionine by the condensation reaction with serine by the PLP-dependent cystathionine β-synthase enzyme. Subsequently, with the deamination and hydrolysis of cystathionine catalyzed by the enzyme cystathionine γ-synthase, L-cysteine is formed (Griffith 1987).

Fig. 1.

Cysteine biosynthesis pathway in humans where cysteine is synthesized from methionine

In protozoa, remarkable differences exist in the biosynthesis of cysteine among these heterotrophic single-celled eukaryotes. Trichomonas vaginalis, an anaerobic protozoa responsible for trichomoniasis in humans, (Westrop et al. 2006) lacks glutathione and is solely dependent on cysteine for its redox balance. The organism is able to generate cysteine from both OAS or O-phosphoserine (OPS) as substrates, through an isoform of OASS, namely O-phosphoserine sulfhydralase (OPSS, EC 2.5.1.65) (Nakamura et al. 2012). Interestingly, CysE that catalyzes the production of OAS from L-serine is not well documented in this organism. However, it has active 3-phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase (PGDH) and an O-phosphoserine aminotransferase (PSAT) that together can form OPS. It is postulated that the sulfide required by T. vaginalis OPSS/CS can come either from homocysteine or mercaptopyruvate through methionine γ-lyase (MGL) or mercaptopyruvate sulfurtransferase (MST). For the methylation reaction, the protozoan parasite uses methionine from S-adenosylmethionine (SAM), resulting in the formation of S-adenosylhomocysteine (SAH). SAH is further hydrolyzed by SAH hydrolase and forms homocysteine (Fig. 2). As enzymes required for both the forward and reverse trans-sulfuration pathways are also absent, direct conversion of methionine to cysteine cannot take place. Furthermore, methionine synthase, which forms methionine from homocysteine, is also not present in T. vaginalis. All these findings suggest that cysteine biosynthesis pathway in this parasite involves mainly OPSS and is distinct from the two-step de novo cysteine biosynthetic pathway in bacteria (Westrop et al. 2006). On the other hand, Trypanosoma cruzi have both de novo cysteine biosynthesis and reverse trans-sulfuration pathways for cysteine production (Nozaki et al. 2001). Since the enzymes belonging to the former pathway are constitutively expressed in both mammalian-stage trypomastigotes and insect-stage epimastigotes, it appears that the de novo cysteine pathway may have “housekeeping” role in controlling OAS levels to maintain thiol concentration in T. cruzi (Nozaki et al. 2005). Similarly, Leishmania major also has both de novo cysteine formation and reverse trans-sulfuration pathways for generating the vital cysteine required as a source of reduced sulfur for metabolites such as CoA, since the genes encoding sulfide reduction pathway are not present in L. major. Sulfide required by OASS-A is accomplished through MST on 3-MP (3-mercaptopyruvate). Studies have shown that Cystathione β-synthase (CBS) of L. major has dual OASS-A/cysteine synthase (CS) or and CBS activities, although the former is 23-fold higher than the latter. This is because, as opposed to mammalian CBS, N-terminal heme binding and C-terminal domains are absent in the parasitic homologue, providing the substrates unrestricted passage to the active site. It is suggested that in L. major, both the CS/OASS-A and CBS are adapted to function in various developmental stages of the parasite (Williams et al. 2009).

Fig. 2.

Cysteine biosynthesis pathway in protozoa T. vaginalis [adapted from)]. The predicted role of MST in generating sulfide source for OPSS is shown in gray. PGDH: 3-phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase; PSAT: O-phosphoserine aminotransferase; OPSS: O-phosphoserine sulfhydralase; SAM-MT: S-adenosylmethionine dependent methyltransferase; SAHH: S-adenosylhomocysteine hydrolase; MGL: methionine γ-lyase; MST: mercaptopyruvate sulphurtransferase

Westrop et al. (2006)

In the archaeal domain, the cysteine biosynthesis pathway is not explored much. Nevertheless, evidence exists for presence of homologues of both CysE and CysK in Methanosarcina thermophila, suggesting that organism may utilize the sulfhydralase pathway, analogous to bacteria and plants, for cysteine biosynthesis (Borup and Ferry 2000). Literature in last few years is providing proof for methanogenic archaea (e.g., Methanococcus jannaschii, M. maripaludis) utilizing RNA-dependent SepRS/SepCysS pathway for synthesis of cysteine and this may be the only pathway for producing cysteine in these organisms (Sauerwald et al. 2005). It is suggested that the presence of essential coenzyme 2-mercaptoethanesulfonate in high levels in these methanogens (Balch and Wolfe 1979) may substitute for redox function of free cysteine and provide additional benefit with respect to thermostability. This may also explain no homologues of the bacterial cysE, cysM, and cysK genes in the genomes of archaea Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum, Methanococcus jannaschii, Pyrococcus horikoshii, and Archaeoglobus fulgidus. Possible contributions of SepRS/SepCysS pathway are being envisaged in processes requiring iron–sulfur enzymes, such as sulfur assimilation, methanogenesis, etc. (Mukai et al. 2017). Interestingly, both cysE and cysK gene products have been isolated from Methanosarcina barkeri that exhibit similarity with bacterial orthologs, suggesting the presence of both tRNA-dependent and tRNA-independent pathways for cysteine synthesis. Furthermore, both genes in M. barkeri are adjacent to each other mimicking similar gene arrangement as in Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Thermotoga maritima. Additionally, CysK identified in the genomes of non-methanogenic archaea such as Aeropyrum pernix, Sulfolobus solfataricus, Pyrococcus furiosus, Pyrococcus abyssi, Picrophilus, Thermoplasma, Halobacteria, etc. show similarity to either OASS or to cystathionine β-synthase suggesting again usage of tRNA-independent pathways for cysteine synthesis in these organisms (Kitabatake et al. 2000).

In bacteria and plants, L-cysteine is produced from L-serine by two steps (Fig. 3). In first step, OAS is formed from L-serine by the transfer of acetyl moiety from acetyl coenzyme A through SAT/CysE (EC 2.3.1.30). In the second step, L-cysteine is formed from OAS in the presence of sulfide or thiosulfate by OASS/CysK (EC 2.5.1.47) (Kredich and Tomkins 1966; Smith and Thompson 1971; Ishikawa and Mino 2012). The latter enzyme exists in two isoforms OASS-A and OASS-B, encoded by the gene cysK and cysM, respectively (Fig. 3). OASS-A/CysK is expressed in aerobic conditions and utilizes sulfide, while OASS-B/CysM is expressed under anaerobic conditions used thiosulfate (Nakamura et al., 1983). In M. tuberculosis, another isoform of OASS, referred as CysK2 (Fig. 3), is reported which uses OPS as a substrate and can utilize sulfide as well as thiosulfate to form cysteine and S-sulfocysteine, respectively (Steiner 2014).

Fig. 3.

De novo cysteine biosynthesis pathway in bacteria and plants. The sulfide enters by the sulfur assimilation pathway through the reduction of sulfate into sulfide. L-cysteine is produced from L-serine in two steps. APS: adenosine 5ʹ-phosphosulfate; PAPS: 3ʹ-phosphoadenosine 5ʹ-phosphosulfate

In contrast to animals and humans that cannot reduce sulfate, bacteria and plants have the ability to assimilate inorganic sulfur as sulfate, and reduce it to sulfide. Sulfur assimilation pathway starts with sulfur uptake via transporters, followed by activation to adenosine 5’-phosphosulfate (APS) by ATP sulfurylase (cysD cysN gene product). APS is phosphorylated into 3’-phosphoadenosine 5ʹ-phosphosulfate (PAPS) by cysC gene product, APS kinase. In some organisms like Mycobacterium, this gene product is fused to CysN (Pinto et al. 2004). In the next step of the pathway, sulfite is released from PAPS by virtue of cysH gene product- PAPS sulfotransferase. This sulfite is reduced by sulfite reductase (cysI cysJ cysG gene product) into sulfide, which in turn enters the de novo cysteine biosynthesis pathway, as shown in Fig. 3 to finally release L-cysteine (Eichhorn and Leisinger 2001; Kawano et al. 2018).

Table 1 lists reported RNA-independent cysteine biosynthetic pathway in different domains of life.

Table 1.

RNA-independent cysteine biosynthetic pathways in different domains of life

| Parasite | Cysteine biosynthetic pathways | References | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| De novo | RTS | OPSS | ||

| Leishmania major | Yes | Yes | No | Williams et al. (2009) |

| Trypanosoma brucei | No | Yes | No | Duszenko et al. (1992) |

| Trypanosoma cruzi | No | No | Yes | Nozaki et al. (2001) |

| Trichomonas vaginalis | No | No | Yes | Westrop et al. (2006) |

| Entamoeba histolytica | Yes | No | No | Kumar et al. (2011) |

| Bacteria | ||||

| Escherichia coli | Yes | No | No | Claus et al. (2005), Zocher et al. (2007) |

| Mycobacterium tuberculosis | Yes | No | No | Ågren et al. (2008) |

| Salmonella typhimurium | Yes | No | No | Becker et al. (1969) |

| Yeast | ||||

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae | No | Yes | No | Thomas and Surdin-Kerjan (1997) |

| Plants | ||||

| Aeropyrum pernix | Yes | No | No | Mino and Ishikawa (2003) |

| Arabidopsis thaliana | Yes | No | No | Warrilow and Hawkesford (2002), Heeg et al. (2008) |

| Humans | ||||

| Homo sapiens | No | Yes | No | Banerjee and Zou (2005) |

Structural insights into CysE

Overall topology

In plants and bacteria, CysE catalyzes the first step of cysteine biosynthesis and converts L-serine into OAS with the help of acetyl CoA. CysE belongs to the bacterial O-acetyltransferases family and O-acyltransferases subfamily (Downie 1989) and is composed of tandem repeats of 6 residues (LIV)-G-X4. The overall characteristic fold associated with CysE comprises of two domains (Fig. 4A)—N-terminal SATase domain comprising of ~ 1 to 140 residues (folded into eight α-helices (α1–α8), which varies in different species and C-terminal LβH (left handed β-helix) domain or hexapeptide repeat domain encompassing residues 141 to generally ~ 260 (14 β-strands making 5 rugs of the helical ladder). While most protozoan CysEs possess only the C-terminal hexapeptide repeat domain, Entamoeba dispar CysE stands as an exception by having both the domains. In contrast, fungal SAT/CysE such as Ogataea parapolymorpha and yeast CysE consist N-terminal mitochondrial targeting sequence (MTS) and C-terminal α/β hydrolase 1 domain which is quite different from bacterial and plant CysE. MTS of O. parapolymorpha targets and localizes the reporter protein to the mitochondria for its complete activity. This is indicative of independent diverging evolution of fungal CysE from other organisms (Yeon et al. 2018).

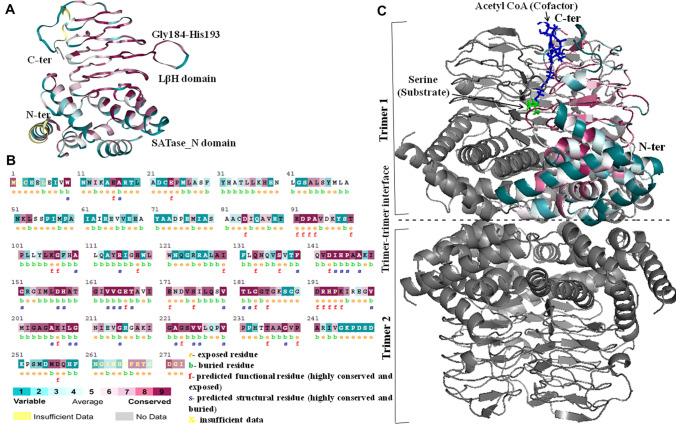

Fig. 4.

ConSurf analysis on (A) 3D cartoon structure of monomeric E. coli CysE (PDB ID: 1T3D) and B secondary amino acid sequence. The residues in both are colored by their conservation grades using the nine-grade color-coding bar, with turquoise-through-maroon indicating variable-through-conserved; C Cartoon representation of hexameric assembly of CysE. The substrate L-serine and cofactor acetyl CoA binding is depicted in green and blue sticks, respectively. The trimer–trimer interface in the CysE hexamer formed by two trimers in head-to-head arrangement is represented with a dotted line

Residue wise conservation among CysE homologues

The conservation score at each amino acid position on 3D structure of monomeric E. coli (Eco) CysE (PDB ID: 1T3D) was computed on ConSurf Server (Glaser et al. 2003), which automatically extracted 150 homologous CysE sequences from the UNIPROT database. Figure 4A and B illustrates the 3D cartoon structure and primary sequence of Eco CysE monomer respectively, colored as per their conservation grades using the nine-grade color-coding bar (turquoise-through-maroon representing variable-through-conserved). The residues critical for structure and function of Eco CysE are labeled s and f, respectively, in Fig. 4B. Some important structural residues such as I144, H145, P146, A148, D157, H158, V163, V164, G165, T181, L182, L209, and G210 are colored maroon and exhibit conservation grade of 9. Functionally important active site residues involved in the binding of substrate or inhibitor such as D92, P93, A94, E166, G183, R192, H193, and P194 also display expected conservation grade of 9. It may be important to reflect here on a previous study carried out by the author with two natural variants of CysE, where in one, the position at 241 (A241) is occupied by Ala, while in the other, it is occupied by Val (V241). The spatial position of this residue does not envisage its participation in activity or shaping of final 3D structure, and therefore, almost null SAT activity of the latter and reduced stability when compared with the former was surprising. According to ConSurf analysis, position 241 is highly conserved (score of 8 in Fig. 4B with Gly and Ser being other allowed amino acids) and forms part of solvent-exposed β-helix that caps the LβH domain. Molecular dynamic simulations provided important insights by revealing that the perturbation caused by A-to-V substitution at this site is propagated to interfaces between subunits, leading to their dissociation. The study established for the first time, position 241 of Eco CysE as a ‘hot spot’ essential for the formation of stable and functional CysE hexamer (Verma et al. 2018).

Quaternary structure

The biologically active form of CysE, as depicted in Fig. 4C, in most of the organisms is association of the two trimers in head-to-head orientation to form a hexamer (Gorman and Shapiro 2004; Pye et al. 2004; Verma et al. 2019). The trimer itself is formed by virtue of monomers coming together in a triangular arrangement with threefold axis parallel to the helical axis of LβH domain and molecular dimensions corresponding to ~ 65 Å (base) X 40 Å (apex) and 50 Å (height). The intermolecular forces holding the two subunits of the trimer are—a salt bridge between the Glu24 of one subunit and Arg125 of the neighboring subunit (residues as per E. coli CysE numbering) and hydrophobic interaction between residues Met26, Leu27, Phe31, and Tyr104 from one chain and Pro56, Ile57, Met58, Pro59, and Tyr131 from the other. Furthermore, a number of H bonds are formed between the side chains of polar residues such as Asn134 in the N-terminal helical domain of one subunit and side chain of the O-atom of main chain of Tyr 104 of another. Similarly, an interchain hydrogen bond is formed between the side chains of Gln178 and Thr181. The side chains of Asp143 and His158 interact to form interchain salt bridge (Table 2). Most of these residues show conservation score of 9 in Fig. 4B. Val239 of adjacent monomers interacts in such a manner so as to cap the end of the β-helix through symmetrical hydrophobic interaction, although this is a moderately conserved (color grade 7 in Fig. 4B) residue and is substituted by Ile, Met, Phe, Leu, Ser, Asn, Pro, Ala, Gly, and even Lys. Similarly, two trimers are organized in staggered manner where one monomer of each trimer interacts with the two monomer of adjacent trimer. The forces between the two trimers at the twofold interface include hydrophobic interactions between side chain of Tyr47 from one subunit and Ile61 from the other. Side chains of Lys37, His38, and Arg64 of one monomer associate with Glu65 of adjacent monomer to form a charged pocket. Hydrogen bond is formed between the side chain of Ser29 from one trimer with the main chain atoms of Pro25, Met26, Ala28, and Ser29 from the adjoining trimer (Table 2). Nevertheless, these N-terminal residues appear dispensable due to low conservation observed in Fig. 4B.

Table 2.

Residues and nature of molecular forces involved in intersubunit interactions

| S.n | A chain | B chain | Nature of interaction |

|---|---|---|---|

| Between two adjacent monomers | |||

| 1 | E24 | R125 | Salt bridge |

| 2 | M26, L27, F31, Y104 | P56, I57, M58, P59, Y131 | Hydrophobic |

| 3 | Main chain O-atom of Y104 | N134 | Hydrogen bond |

| 4 | Q178 | T181 | Hydrogen bond |

| 5 | D143 | H158 | Salt bridge |

| Between two trimers | |||

| Trimer 1 | Trimer 2 | Nature of interaction | |

| 1 | Y47 | I61 | Hydrophobic |

| 2 | S29 | P25, M26, A28, S29 | Hydrogen bond |

CysE does not necessarily assemble into a hexamer exclusively, a well-studied case being that of enteric protozoan E. histolytica (Ehi) CysE which exists as a trimer (Kumar et al. 2011). N-terminal region (~ 100 residues) of Ehi SAT1 is quite different in primary sequence resulting in different orientation of N-terminal helices (especially, helix 4 and 5) and charge distribution when compared to other bacterial CysEs. In addition, an 8 amino acid insertion in the active site loop and variations in the C-terminal region of Ehi CysE have broader implications in abolishing regulatory mechanisms (discussed in the ensuing section) and ensuring sufficient cysteine availability for glutathione deficient E. histolytica's survival under oxidative stress (Nozaki et al. 1998; Kumar et al. 2011). This organism has multiple CysE isoforms, namely Ehi SAT1, Ehi SAT2, and Ehi SAT3 which, respectively, exhibit high, intermediate, and insensitivity towards the feedback inhibitor L-cysteine (Hussain et al. 2009). Susceptibility to cysteine inhibition in bacterial enzymes is mainly due to the inhibitor competing with the substrate L-serine at the active site and allosteric conformational differences in acetyl CoA-binding site. Structural and biochemical studies with EhiSAT1 attribute differences in the N-terminal region, active site loop, and C-terminal residues of Ehi isoforms to yield an open and accessible acetyl CoA-binding site that is unaffected by cysteine binding (Kumar et al. 2011). An independent in silico analysis on biological assembly of Mtb CysE predicts that it may exist as a trimer due to its (i) shorter N-terminus (comprising of only 4 helices) as compared to most of the CysEs (containing 8 helices) and (ii) more positive surface and irregular trimeric base being unfavorable for trimeric–trimeric interactions (Gupta and Gupta 2020). Anyhow recent reports on oligomeric state of CysE indicate that both trimeric and hexameric populations coexist in solution (Kumar et al. 2014; Verma et al. 2018, 2020). X-ray crystallography structures have been determined for CysE from several organisms such as Escherichia coli, Haemophilus influenza, Entamoeba histolytica, Brucella abortus, Brucella melitensis, Vibrio cholerae, Yersinia pestis, Bacteroides vulgates, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Glycine max, proving instrumental in providing insights into the structural determinants leading to functional diversity among these organisms. Table 3 puts together these available structures with their PDB codes and related publications for ready reference.

Table 3.

Reported PDB structures of CysE enzyme of cysteine biosynthetic pathway

| Domain | Organism | SAT (CysE) and apo or ligand bound |

|---|---|---|

| Bacteria | Escherichia coli | 1T3D (complexed with cysteine) (Pye et al. 2004) |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | 6JVU (complexed with cysteine) (Verma et al. 2019) | |

| Vibrio cholerae | 4H7O (complexed with cysteine) (To be published) | |

| Yersinia pestis | 3GVD (complexed with cysteine) (To be published) | |

| Brucella melitensis | 3MC4 (Apo form) (To be published) | |

| Brucella abortus | 4HZC (Apo form) (Kumar et al. 2014); 4HZD (complexed with Acetyl CoA) (Kumar et al. 2014) | |

| Haemophilus influenzae | 1S80 (Apo form) (Gorman and Shapiro 2004); 1SSM (truncated apoenzyme) (Olsen et al. 2004); 1SSQ (complexed with cysteine) (Olsen et al. 2004); 1SST (complexed with Acetyl CoA) (Olsen et al. 2004) | |

| Bacteroides vulgates | 3F1X (Apo form) (To be published) | |

| Protozoa | Entamoeba histolytica | 3P1B (Apo form) (Kumar et al. 2011); 3P47 (complexed with L-cysteine) (Kumar et al. 2011); 3Q1X (complexed with L-serine) (Kumar et al. 2011) |

| Plant | Glycine max | 4N69 (complexed with serine) (Yi et al. 2013); 4N6A (apo form) (Yi et al. 2013); 4N6B (complexed with CoA) (Yi et al. 2013) |

Active site and mechanism of serine O-acetylation

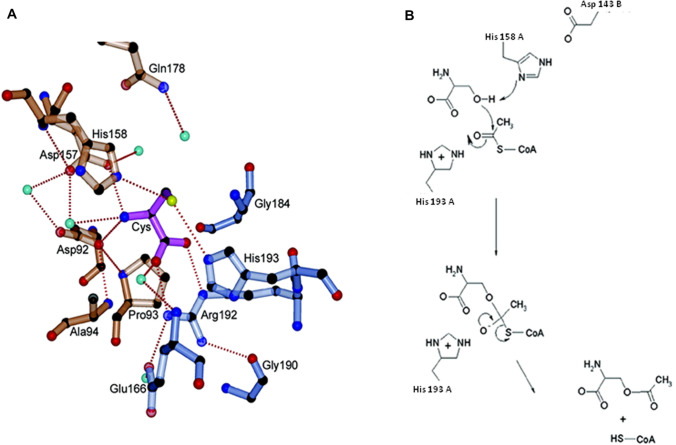

The conserved substrate (or feedback inhibitor) binding site of CysE is located in the cleft between two adjacent monomers (Fig. 4C), with six active sites in the biologically relevant hexameric CysE (Olsen et al. 2004; Gorman and Shapiro 2004; Pye et al. 2004; Verma et al. 2020). The active site is formed by β-strand (Asp157-Thr160, as per E. coli CysE numbering) and the β-turn meander (from α5- α6) of one subunit and the substrate-binding loop (Gly184-His193) of the neighboring subunit. The substrate-binding loop is composed of 10 residues (184GTGKTSGDRH193) and includes conserved small residues such as Gly for imparting space for ligand binding. The active site comprises of two histidine residues, His158 and His193, one from each subunit, which form H-bond with sulfur moiety of the ligand. Apart from these, three other charged residues are involved in catalysis namely, Asp92, Asp157 from one subunit and Arg192 from the other (Fig. 5A). Based on the crystal structure of E. coli CysE in complex with cysteine, a ternary intermediate has been modeled with L-serine in the active site. It is envisaged that Oγ of L-serine forms an H bonds with His158 and Asp143 (each from different subunit) and making a catalytic triad. Subsequently, Oγ mounts a nucleophilic attack on the carbonyl of acetyl CoA, and after the collapse of tetrahedral intermediate, the products OAS and CoA are generated (Gorman and Shapiro 2004; Pye et al. 2004). Amine and carboxylate moieties of L-serine form additional contacts with carboxylate side chains of two Asps (92 and 157) and with the side chain of Arg192, respectively (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5.

A Architecture of cysteine-binding site. Active site residues from adjacent subunits are depicted in orange and blue color, while cysteine is shown in purple color ball and stick representation. Hydrogen bonds are shown in red dotted line and water molecules are depicted in cyan sphere; B mechanism of serine O-acetylation (adapted from

Pye et al. 2004)

A comparative analysis of Eco CysE and modeled Mtb CysE active sites also provides exciting insights. Subtle differences in the substrate-binding LβH and the β-turn meander loops, responsible for positioning of substrate and cofactor in their respective binding sites, alter the active site architecture of Mtb homologue in regards to its electrostatic charge distribution, size, and hydrophobic character, suggesting significant differences in binding affinities of ligands in this active site as compared to Eco counterpart (Gupta and Gupta 2020).

Acetyl CoA-binding site and mechanism of O-acetyl serine formation

Similarly, the cofactor (acetyl CoA)-binding site is also located at the cleft of two monomers of adjacent subunit (Fig. 4C). There are several C-terminal hydrophobic residues that form a cavity to accommodate acetyl CoA. Ala204 forms hydrogen bond with terminal carbonyl oxygen of CoA, whereas Ala222 amide group interacts with the proximal carbonyl oxygen of the CoA and carbonyl oxygen of the same residue H bonds with the nitrogen of adenyl moiety of CoA. These interactions stabilize the acetyl CoA in such a way that its extended chain orient towards the active site which facilitate the transfer of acetyl group to the serine. The residues His193, His158, and Asp157 make the catalytic core of acetyl CoA where His158 activate the serine -OH group which works as nucleophile for acetyl CoA and generate tetrahedral intermediate. The positive charge of His193 is neutralized with the carbonyl oxygen of Asp157 and amide group of His193 stabilizes this intermediate. Subsequent rearrangements lead to the formation of OAS and releases CoA (Kumar et al. 2014).

Regulation of de novo cysteine biosynthesis pathway

Pathogenic microbes reside in an oxidative host environment necessitating the uptake of oxidized form of sulfur followed by reduction to sulfide intracellularly. Hence, cysteine biosynthetic pathway has two arms with separate roles in (i) sulfate uptake and reduction and (ii) formation of cysteine. In fact, an alternative route of cysteine biosynthesis via thiosulfate uptake lies on third independent arm, eliminating the need of sulfate reduction (Fig. 3). The thiol moiety of cysteine is highly reactive making it toxic to the cells at higher concentrations (Kari et al. 1971). That is why, the synthesis and degradation of this amino acid is stringently regulated at many levels. Most of the cysteine biosynthesis genes are positively regulated at the transcription level by CysB transcriptional activator but not the genes encoding CysE and CysK (Kredich 1992). De novo cysteine biosynthesis is governed by intracellular levels of sulfur and OAS through three documented mechanisms illustrated in Fig. 6—(1) The feedback inhibition of CysE by its end product L-cysteine. L-cysteine competes with the substrate L-serine for binding to the active site (Becker et al. 1969; Guédon and Martin-Verstraete 2006). The structural basis lies in conformational change of C-terminal stretch that places residues in the acetyl CoA-binding site ruling out acetylation of enzyme bound cysteine (Olsen et al. 2004). (2) Reversible protein–protein interaction between CysE and CysK. The C-terminal tail of CysE binds in the active site cleft of CysK with high affinity, resulting in formation of the heteromeric bi-enzyme Cysteine Synthase Complex (CSC) where CysK activity is inhibited. The role of the bi-enzyme complex in sensing sulfur-status is well established in plants where CysK concentration is many fold higher than CysE (Nakamura and Tamura 1990; Droux et al. 1992; Ruffet et al. 1994). In fact cysE is the only constitutively expressed gene of cysteine regulon (cysPUWAM) that is controlled by CysB transcription factor. However, free CysE is more prone to aggregation and degradation as opposed to CysK bound form (Droux et al. 1998), and hence, CSC formation protects CysE and results in enhanced activity of CysE but inhibition of CysK. Furthermore, bisulfide favors association of the two enzymes (Burkhard et al. 2000), whereas OAS inhibits the CysE-CysK interaction because of competition for binding to the CysK active site (Huang et al. 2005). In essence, sulfur availability influences CSC formation and CysE activity in plants, in turn affecting OAS levels and thereby cysteine production (Fig. 6). Under sulfur-rich conditions, free CysK converts OAS to L-cysteine, diminishing OAS levels and thereby favoring CSC formation. When sulfur is limiting, CysK fails to convert OAS into cysteine, resulting in OAS accumulation, dissociation of the bi-enzyme complex, and partial inactivation of CysE. The uptake of sulfate and subsequent reduction to sulfide as well as uptake of thiosulphate are dependent on OAS levels which can non-enzymatically isomerize into N-acetyl serine (NAS). Increased NAS is an indicative of accumulated OAS which in turn is governed by intracellular concentration of bisulfide. Studies suggest that NAS may be the actual inducer that can activate CysB to start transcription from cysteine regulon (Campanini et al. 2015). Additional effect of increased OAS is the activation of sulfate uptake and sulfur assimilation (transport and reduction) genes for restoration of intracellular sulfur (Becker et al. 1969; Jez and Dey 2013; Kaushik et al. 2017). In principle, CSC assembly is an indicator for the concentrations of sulfate, sulfur, and OAS. Key difference between plant and bacterial CSC function/regulation lies with the latter being more sensitive to feedback inhibition by L-cysteine (Ki ~ 1.1 µM). In plants, Ki for cysteine is reported to increase 70-fold on CSC formation, which is not the case for bacterial complex (Kredich et al. 1969; Wirtz et al. 2010). It has been reported that CSC of Salmonella typhimurium is also stabilized by sulfide and dissociated by OAS (Kredich et al. 1969). Early evidence of role of CSC assembly in bacteria for proper cysteine synthesis was provided by studies on mutant strain of the S. typhimurium that was initially isolated as a cysteine auxotroph and had reduced SAT activity and CysK interaction (Becker and Tomkins 1969). Latter DNA sequencing revealed only one base mutation that corresponded to a point mutation of A237E in the C-terminal region of CysE. Further site-directed mutations in the C-terminal domain exposed its role in catalytic activity as well as hetero-oligomerization with CysK (Wirtz et al. 2001). The CSC from Salmonella typhimurium is reported to be composed of one molecule of CysE hexamer and two molecules of CysK dimers with an approx molecular weight of ~ 310 kDa (Kredich et al. 1969). Truncation of ten amino acids from C-terminus of E. coli CysE altered the sensitivity to cysteine inhibition (Mino et al. 2000), whereas further deletion of another ten residues reduced the feedback inhibition by cysteine (Denk and Bock 1987). Among these, the most important CysE residue that contributes in the complex formation is the terminal isoleucine. Studies with Ehi SAT isoforms (discussed above) also corroborate the importance of C-terminal residues in regulating feedback inhibition and CSC formation.

Fig. 6.

Different regulatory mechanism to regulate the L-Cys formation at protein level. (1) CysE (yellow hexamer) inhibited by L-Cys (end product) through feedback inhibition; (2) Formation of bi-enzyme complex between CysE and CysK (green dimer). C-ter tail of CysE binds at the active site of CysK and forms bi-enzyme complex. In the complex, CysK inactivated and under sulfur-depleted conditions O-acetyl serine is not converted into L-cysteine by CysK and dissociates the bi-enzyme complex resulting in downregulation of cysteine synthesis; (3) Perturbation in hexameric assembly leads to the different ensemble of hexameric, dimeric, and monomeric population resulted in reduced formation of cysteine and this can be another regulatory mechanism of regulating cysteine synthesis

In addition to the above well-documented regulatory mechanisms, another possibility recently raised is—(3) perturbation in the quaternary assembly of bacterial CysE may be another putative regulatory mechanism to maintain the cysteine at intercellular level (Fig. 6). The researchers observed that the heterogeneous ensemble and loss of hexameric (quaternary) structure of S. flexneri CysE resulted in reduced enzymatic activity and stability of CysE, suggesting that the CysE enzyme activity may be tuned at quaternary level, as well (Verma et al. 2018).

Inhibitors of CysE

Treatment of bacterial infections is limited by microbes developing resistance towards all major classes of available drugs, necessitating discovery of newer and effective antibiotics against novel targets that have no known resistance. CysE is one such potential novel target and compounds targeting this enzyme may provide possibility of therapeutic intervention for treating drug-resistant bacterial infections. Apart from the feedback inhibitor L-cysteine and glycine which also inhibits CysE with Ki 13 ± 4 mM (Leu and Cook 1994; Johnson et al. 2004), only a few inhibitors of CysE have been identified till date, all through structure-based design approach. Nevertheless, the section below reviews the state-of-the-art of CysE inhibitors.

A low-molecular-weight synthetic compound, discovered by virtual screening of a chemical library against the available crystal structure of E. coli CysE (with IC50 of 72 μM), also inhibited the proliferation of E. histolytica (Agarwal et al. 2008). Similarly, screening of natural product library against CysE of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) yielded six natural compounds that could inhibit CysE activity and MRSA growth. Additionally, two out of these, with an IC50 of 30 μM and 72 μM, exhibited antibiofilm activity as well (Chen et al. 2019). To this scanty inhibitor database of the enzyme, our investigations against K. pneumoniae CysE, identified 5 inhibitors, namely, apocynin, berberin, mangiferin, quercetin, and vasicine, through in silico docking of natural compound. Of these, quercetin was found to be most potent inhibitor that allostrically inhibited Kpn CysE with Ki of 162 μM and IC50 of 3.7 μM. An allosteric inhibitor may present certain advantages over orthosteric inhibitor with respect to not facing the same evolutionary pressure and thereby decreasing resistance susceptibility (Monserrat-Martinez et al. 2019). Quercetin also inhibited the activity of E. coli and S. flexneri CysEs, and offers promises as a lead compound for drug discovery (Verma et al. 2020). An in silico screening of anti-tubercular bioactive compounds against Mtb CysE employed bioactive compounds from natural origin due to their drug like properties and extraordinary structural and chemical diversities. After short listing the top hits, the researchers also docked them in the active site cleft of Eco CysE as a control. Compounds C1, C3, C4, and C7 exhibited preference for Mtb CysE, and were reported as selective inhibitors of Mtb CysE (Gupta and Gupta 2020). Another study has reported the inhibitors of S. typhimurium CysE through virtual screening of ChemDiv focused library where six compounds displayed inhibitory activity with IC50 below 100 μM, with compound 3 being the most potent with IC50 of 48.6 μM (Table 4). One of the compounds also interfered with the growth of E. coli in cell-based assay with MIC of 64 μg/ml (Magalhaes et al. 2020). The same group has discovered new inhibitors of S. typhimurium CysE through virtual screening of in-house chemical library and the compound 22d (3,5-dimethylphenyl) exhibited several fold higher inhibitory potency with IC50 4.24 μM. Despite improvement, most promising compound was not able to interfere with bacterial growth, and hence, further research is required for identifying a compound with improved permeability (Magalhaes et al. 2021). Table 4 lists the significant inhibitors of CysE reported till date.

Table 4.

Selected potent inhibitors of CysE reported till date

| CysE | Inhibitors | IC50 | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli CysE | 3-Oxo-2-phenyl-3,5-dihydro-2H-pyrazolo(3,4d)thieno(2,3-b)pyridine-7-carboxylic acid | 72 μM | Agarwal et al. (2008) |

| S. aureus CysE | 11-oxo-ebracteolatanolide B | 30 μM | Chen et al. (2019) |

| (4R,4aR)-dihydroxy-3-hydroxymethyl-7,7,10atrimethyl-2,4,4a,5,6,6a,7,8,9,10,10a,l0b dodecahydrophenanthro [3,2-b]furan-2-one) | 72 μM | ||

| K. pneumoniae CysE | Quercetin | 3.7 μM | Verma et al. (2020) |

| M. tuberculosis CysE | C1; CHEMBL1426565 | – | Gupta and Gupta (2020) |

| C3; CHEMBL1321725 | |||

| C4; CHEMBL1162041 | |||

| C7; CHEMBL1506527 | |||

| S. typhimurium CysE | 1,2,3-thiadiazole-4-carboxylic acid | 48.6 μM | Magalhaes et al. (2020) |

| S. typhimurium CysE | 22d; 3,5-dimethylphenyl | 4.24 μM | Magalhaes et al. (2021) |

Concluding remarks

The emerging issue of antimicrobial resistance demands for us to upgrade our present armatorium of therapeutics to supersede unmanageability of infections caused by MDR pathogens. This can be achieved by discovery of novel targets that are responsible for virulence and vital metabolism of pathogens. The pathway or genes involved in production of cysteine appear to be essential for survival of persistence in several microbes, including M. tuberculosis. The de novo cysteine biosynthetic pathway is present in plants, bacteria, and protozoa, but absent in humans as a different route is employed there for cysteine production, recommending this pathway as an attractive targets for developing novel antibiotics. This review discusses recent studies on structure function and regulation of CysE, the first enzyme of the pathway. The information gathered indicate that despite conserved structure, slight modification can lead to altered regulatory mechanisms affecting cysteine production. An A241V mutation in a natural variant of Sfl CysE, perturbs the quaternary structure to an extent that the variant loses its activity and stability, suggesting for the first time its crucial role in CysE's structure and function. Similarly, a single residue change (His208Ser) in Ehi SAT3 when compared to EhiSAT1 makes this isoform insensitive to cysteine feedback inhibition, causing its constitutive expression. Moreover, in E. histolytica, CysE does not interact with CysK to form complex CSC, abolishing another regulatory mechanism that comes into play under sulfur-sufficient conditions. It appears that the organism has evolved its cysteine biosynthetic pathway to enable its survival in the host. Although some active site as well as allosteric inhibitors have been reported, but no drug molecule exists so far and further work is required in this direction.

Acknowledgements

Authors are grateful to the Department of Biotechnology (DBT), Government of India, for the research grant (Ref No. BT/BioCARe/01/79/2011-12).

Author contributions

DV thoroughly reviewed the literature, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript; VG conceived and supervised the study as well as critically revised the manuscript.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest related to this study.

Contributor Information

Deepali Verma, Email: deepali.biotechnology@gmail.com.

Vibha Gupta, Email: vibha.gupta@jiit.ac.in.

References

- Agarwal S, Jain R, Bhattacharya A, Azam A. Inhibitors of Escherichia coli serine acetyltransferase block proliferation of Entamoeba histolytica trophozoites. Int J Parasitol. 2008;38:137–141. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2007.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ågren D, Schnell R, Oehlmann W, et al. Cysteine synthase (CysM) of Mycobacterium tuberculosis is an O-phosphoserine sulfhydrylase: evidence for an alternative cysteine biosynthesis pathway in Mycobacteria. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:31567–31574. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M804877200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akerley BJ, Rubin EJ, Novick VL, et al. A genome-scale analysis for identification of genes required for growth or survival of Haemophilus influenzae. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2002;99:966–971. doi: 10.1073/pnas.012602299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson MT, Mitchell LA, Mobley HLT. Cysteine biosynthesis controls Serratia marcescens phospholipase activity. J Bacteriol. 2017;199:e00159–e217. doi: 10.1128/JB.00159-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balch WE, Wolfe RS. Specificity and biological distribution of coenzyme M (2-mercaptoethanesulfonic acid) J Bacteriol. 1979;137:256–263. doi: 10.1128/jb.137.1.256-263.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee R, Zou CG. Redox regulation and reaction mechanism of human cystathionine-β- synthase: a PLP-dependent hemesensor protein. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2005;433:144–156. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2004.08.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker MA, Tomkins GM. Pleiotrophy in a cysteine-requiring mutant of Samonella typhimurium resulting from altered protein-protein interaction. J Biol Chem. 1969;244:6023–6030. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9258(18)63576-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker MA, Kredich NM, Tomkins GM. The purification and characterization of O-acetylserine sulfhydrylase—a from Salmonella typhimurium. J Biol Chem. 1969;244:2418–2427. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9258(19)78240-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhave DP, Muse WB, Carroll KS. Drug targets in mycobacterial sulfur metabolism. Infect Disord Drug Targets. 2007;7:140–158. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2001449.Engineering. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borup B, Ferry JG. Cysteine biosynthesis in the Archaea: Methanosarcina thermophila utilizes O-acetylserine sulfhydrylase. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2000;189:205–210. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2000.tb09231.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burkhard P, Tai CH, Jansonius JN, Cook PF. Identification of an allosteric anion-binding site on O-acetylserine sulfhydrylase: structure of the enzyme with chloride bound. J Mol Biol. 2000;303:279–286. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campanini B, Benoni R, Bettati S, et al. Moonlighting O-acetylserine sulfhydrylase: new functions for an old protein. Biochimica Biophysica Acta-Proteins and Proteom. 2015;1854:1184–1193. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2015.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhuri RR, Allen AG, Owen PJ, et al. Comprehensive identification of essential Staphylococcus aureus genes using transposon-mediated differential hybridisation (TMDH) BMC Genomics. 2009;10:291. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-10-291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C, Yan Q, Tao M, et al. Characterization of serine acetyltransferase (CysE) from methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and inhibitory effect of two natural products on CysE. Microb Pathog. 2019;131:218–226. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2019.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claus MT, Zocher GE, Maier THP, Schulz GE. Structure of the O-acetylserine sulfhydrylase isoenzyme CysM from Escherichia coli. Biochemistry. 2005;44:8620–8626. doi: 10.1021/bi050485+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denk D, Bock A. L-Cysteine biosynthesis in Escherichia coli: nucleotide sequence and expression of the serine acetyltransferase (cysE) gene from the wild-type and a cysteine-excreting mutant. J Gen Microbiol. 1987;133:515–525. doi: 10.1099/00221287-133-3-515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixit A, Kumar N, Kumar S, Trigun V. Antimicrobial resistance: progress in the decade since emergence of New Delhi metallo-β-lactamase in India. Indian J Commun Med. 2019;44:4–8. doi: 10.4103/ijcm.IJCM_217_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downie JA. The nodL gene from Rhizobium leguminosarum is homologous to the acetyl transferases encoded by lacA and cysE. Mol Microbiol. 1989;3:1649–1651. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1989.tb00150.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Droux M, Martin J, Sajus P, Douce R. Purification and characterization of O-acetylserine (thiol) lyase from spinach chloroplasts. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1992;295:379–390. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(92)90531-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Droux M, Ruffet ML, Douce R, Job D. Interactions between serine acetyltransferase and O-acetylserine (thiol) lyase in higher plants. Structural and kinetic properties of the free and bound enzymes. Eur J Biochem. 1998;255:235–245. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1998.2550235.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duszenko M, Mühlstädt K, Broder A. Cysteine is an essential growth factor for Trypanosoma brucei bloodstream forms. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1992;50:269–273. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(92)90224-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fair RJ, Tor Y. Antibiotics and bacterial resistance in the 21st century. Perspect Med Chem. 2014;6:25–64. doi: 10.4137/PMC.S14459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischbach MA, Walsh CT. Antibiotics for emerging pathogens. Science. 2009;325:1089–1093. doi: 10.1126/science.1176667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gandra S, Barter DM, Laxminarayan R. Economic burden of antibiotic resistance: how much do we really know? Clin Microbiol Infect. 2014;20:973–980. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gandra S, Joshi J, Sankhil A, Laxminarayan R (2017) Scoping report on antimicrobial resistance in india—center for disease dynamics, economics & policy (CDDEP). https://cddep.org/publications/scoping-report-antimicrobial-resistance-india/. Accessed 27 Feb 2020

- Gelband H, et al (2015) State of the world’s antibiotics. https://www.cddep.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/swa_edits_9.16.pdf. Accessed 27 Feb 2020

- Gillin FD, Diamond LS. Attachment of Entamoeba histolytica to glass in a defined maintenance medium: specific requirement for cysteine and ascorbic acid. J Protozool. 1980;27:474–478. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.1980.tb05402.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser F, Pupko T, Paz I, et al. ConSurf: identification of functional regions in proteins by surface-mapping of phylogenetic information. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:163–164. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/19.1.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorman J, Shapiro L. Structure of serine acetyltransferase from Haemophilus influenzae Rd. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2004;60:1600–1605. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904015240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffith OW. Mammalian sulfur amino acid metabolism: an overview. Methods Enzymol. 1987;143:366–376. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(87)43065-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guédon E, Martin-Verstraete I. Amino acid biosynthesis ~ pathways, regulation and metabolic engineering. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg; 2006. Cysteine metabolism and its regulation in bacteria; pp. 195–218. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta S, Gupta V. Homology modeling, structural insights and in-silico screening for selective inhibitors of mycobacterial CysE. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 2020;39:1547–1560. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2020.1734089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heeg C, Kruse C, Jost R, et al. Analysis of the Arabidopsis O-acetylserine(thiol)lyase gene family demonstrates compartment-specific differences in the regulation of cysteine synthesis. Plant Cell. 2008;20:168–185. doi: 10.1105/tpc.107.056747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang B, Vetting MW, Roderick SL. The active site of O-acetylserine sulfhydrylase is the anchor point for bienzyme complex formation with serine acetyltransferase. J Bacteriol. 2005;187:3201–3205. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.9.3201-3205.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussain S, Ali V, Jeelani G, Nozaki T. Isoform-dependent feedback regulation of serine O-acetyltransferase isoenzymes involved in l-cysteine biosynthesis of Entamoeba histolytica. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2009;163:39–47. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2008.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa K, Mino K (2012) Biosynthesis of cysteine. In: Chorkina FV, Karataev AI (eds) Cysteine: biosynthesis, chemical, structure and toxicity. Nova Science Publishers, Inc., pp 111–134

- Jez JM, Dey S. The cysteine regulatory complex from plants and microbes: what was old is new again. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2013;23:302–310. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2013.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson CM, Huang B, Roderick SL, Cook PF. Kinetic mechanism of the serine acetyltransferase from Haemophilus influenzae. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2004;429:115–122. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2004.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi P, Gupta A, Gupta V. Insights into multifaceted activities of CysK for therapeutic interventions. 3 Biotech. 2019;9:1–16. doi: 10.1007/s13205-019-1572-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kari C, Nagy Z, Kovács P, Hernádi F. Mechanism of the growth inhibitory effect of cysteine on Escherichia coli. J Gen Microbiol. 1971;68:349–356. doi: 10.1099/00221287-68-3-349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaushik A, Ekka MK, Kumaran S. Two distinct assembly states of the cysteine regulatory complex of Salmonella typhimurium are regulated by enzyme-substrate cognate pairs. Biochemistry. 2017;56:2385–2399. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.6b01204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawano Y, Suzuki K, Ohtsu I. Current understanding of sulfur assimilation metabolism to biosynthesize L-cysteine and recent progress of its fermentative overproduction in microorganisms. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2018;102:8203–8211. doi: 10.1007/s00253-018-9246-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitabatake M, So MW, Tumbula DL, Söll D. Cysteine biosynthesis pathway in the archaeon Methanosarcina barkeri encoded by acquired bacterial genes? J Bacteriol. 2000;182:143–145. doi: 10.1128/JB.182.1.143-145.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi K, Ehrlich SD, Albertini A, et al. Essential Bacillus subtilis genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2003;100:4678–4683. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0730515100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kredich NM. The molecular basis for positive regulation of cys promoters in Salmonella typhimurium and Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 1992;6:2747–2753. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb01453.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kredich NM, Tomkins GM. The enzymic synthesis of L-cysteine in Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium. J Biol Chem. 1966;241:4955–4966. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9258(18)99657-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kredich NM, Becker MA, Tomkins GM. Purification and characterization of cysteine synthetase, a bifunctional protein complex, from Salmonella typhimurium. J Biol Chem. 1969;244:2428–2439. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9258(19)78241-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S, Raj I, Nagpal I, et al. Structural and biochemical studies of serine acetyltransferase reveal why the parasite Entamoeba histolytica cannot form a cysteine synthase complex. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:12533–12541. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.197376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S, Kumar N, Alam N, Gourinath S. Crystal structure of serine acetyl transferase from Brucella abortus and its complex with coenzyme A. Biochimica Biophysica Acta-Proteins and Proteom. 2014;1844:1741–1748. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2014.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laxminarayan R, Chaudhury RR. Antibiotic resistance in India: drivers and opportunities for action. PLoS Med. 2016;13:e1001974. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leu LS, Cook PF. Kinetic mechanism of serine transacetylase from Salmonella typhimurium. Biochemistry. 1994;33:2667–2671. doi: 10.1021/bi00175a040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leustek T, Martin MN, Bick J-A, Davies JP. Pathways and regulation of sulfur metabolism revealed through molecular and genetic studies. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 2000;51:141–165. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.51.1.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu YB, Long MX, Yin YJ, et al. Physiological roles of mycothiol in detoxification and tolerance to multiple poisonous chemicals in Corynebacterium glutamicum. Arch Microbiol. 2013;195:419–429. doi: 10.1007/s00203-013-0889-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magalhaes J, Franko N, Raboni S, et al. Inhibition of non-essential bacterial targets: discovery of a novel serine O-acetyltransferase inhibitor. ACS Med Chem Lett. 2020;11:790–797. doi: 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.9b00627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magalhaes J, Franko N, Raboni S, et al. Discovery of substituted (2-aminooxazol-4-yl)Isoxazole-3-carboxyl acids as inhibitors of bacterial Serine acetyltransferase in the quest for novel potential antibacterial adjuvants. Pharmaceuticals. 2021;14:174. doi: 10.3390/ph14020174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mino K, Ishikawa K. Characterization of a novel thermostable O-acetylserine sulfhydrylase from Aeropyrum pernix K1. J Bacteriol. 2003;185:2277–2284. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.7.2277-2284.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mino K, Hiraoka K, Imamura K, et al. Characteristics of serine acetyltransferase from escherichia coli deleting different lengths of amino acid residues from the C-terminus. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2000;64:1874–1880. doi: 10.1271/bbb.64.1874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monserrat-Martinez A, Gambin Y, Sierecki E. Thinking outside the bug: molecular targets and strategies to overcome antibiotic resistance. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:E1255. doi: 10.3390/ijms20061255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukai T, Crnković A, Umehara T, et al. RNA-dependent cysteine biosynthesis in bacteria and archaea. Mbio. 2017;8:e00561–e617. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00561-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura K, Tamura G. Isolation of serine acetyltransferase complexed with cysteine synthase from allium tuberosum. Agric Biol Chem. 1990;54:649–656. doi: 10.1080/00021369.1990.10870005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura T, Kawai Y, Kunimoto K, et al. Structural analysis of the substrate recognition mechanism in O-phosphoserine sulfhydrylase from the hyperthermophilic archaeon aeropyrum pernix K1. J Mol Biol. 2012;422:33–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2012.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noji M, Saito K. Sulphur amino acids: biosynthesis of cysteine and methionine. Netherlands: Springer; 2003. pp. 135–144. [Google Scholar]

- Nozaki T, Asai T, Kobayashi S, et al. Molecular cloning and characterization of the genes encoding two isoforms of cysteine synthase in the enteric protozoan parasite Entamoeba histolytica1. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1998;97:33–44. doi: 10.1016/S0166-6851(98)00129-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nozaki T, Shigeta Y, Saito-Nakano Y, et al. Characterization of transsulfuration and cysteine biosynthetic pathways in the protozoan hemoflagellate, Trypanosoma cruzi: Isolation and molecular characterization of cystathionine β-synthase and serine acetyltransferase from trypanosoma. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:6516–6523. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009774200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nozaki T, Ali V, Tokoro M. Sulfur-containing amino acid metabolism in parasitic protozoa. Adv Parasitol. 2005;60:1–99. doi: 10.1016/S0065-308X(05)60001-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen LR, Huang B, Vetting MW, Roderick SL. Structure of serine acetyltransferase in complexes with CoA and its cysteine feedback inhibitor. Biochemistry. 2004;43:6013–6019. doi: 10.1021/bi0358521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinto R, Tang QX, Britton WJ, et al. The Mycobacterium tuberculosis cysD and cysNC genes form a stress-induced operon that encodes a tri-functional sulfate-activating complex. Microbiology. 2004;150:1681–1686. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.26894-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Power E. Impact of antibiotic restrictions: the pharmaceutical perspective. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2006;12:25–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2006.01528.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Projan SJ. Why is big pharma getting out of antibacterial drug discovery? Curr Opin Microbiol. 2003;6:427–430. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2003.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pye VE, Tingey AP, Robson RL, Moody PCE. The structure and mechanism of serine acetyltransferase from Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:40729–40736. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403751200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramos T (2014) Cysteine biosynthesis in Leishmania. PhD thesis, University of Glasgow. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/5156/

- Rengarajan J, Bloom BR, Rubin EJ. From the cover: genome-wide requirements for Mycobacterium tuberculosis adaptation and survival in macrophages. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2005;102:8327–8332. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503272102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruffet ML, Droux M, Douce R. Purification and kinetic properties of serine acetyltransferase free of O-acetylserine(thiol)lyase from spinach chloroplasts. Plant Physiol. 1994;104:597–604. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.2.597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sassetti CM, Rubin EJ. Genetic requirements for mycobacterial survival during infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2003;100:12989–12994. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2134250100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sassetti CM, Boyd DH, Rubin EJ. Genes required for mycobacterial growth defined by high density mutagenesis. Mol Microbiol. 2003;48:77–84. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03425.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauerwald A, Zhu W, Major TA, et al. RNA-dependent cysteine biosynthesis in archaea. Science. 2005;307:1969–1972. doi: 10.1126/science.1108329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpkin VL, Renwick MJ, Kelly R, Mossialos E. Incentivising innovation in antibiotic drug discovery and development: progress, challenges and next steps. J Antibiot. 2017;70:1087–1096. doi: 10.1038/ja.2017.124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith IK, Thompson JF. Purification and characterization of l-serine transacetylase and O-acetyl-l-serine sulfhydrylase from kidney bean seedlings (Phaseolus vulgaris) BBA-Enzymology. 1971;227:288–295. doi: 10.1016/0005-2744(71)90061-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steiner EM, Both D, Lossl P, et al. CysK2 from Mycobacterium tuberculosis is an O-phospho-L-serine-dependent S-sulfocysteine synthase. J Bacteriol. 2014;196:3410–3420. doi: 10.1128/JB.01851-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tacconelli E, Carrara E, Savoldi A, et al. Discovery, research, and development of new antibiotics: the WHO priority list of antibiotic-resistant bacteria and tuberculosis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2018;8(3):318–327. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30753-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taneja N, Sharma M. Antimicrobial resistance in the environment: the Indian scenario. Indian J Med Res. 2019;149:119–128. doi: 10.4103/ijmr.IJMR_331_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Pew Charitable Trusts, Trusts TPC (2017) Antibiotics currently in clinical development. Antibiotic resistant project 1–7

- The Review on Antimicrobial Resistance (2014) Antimicrobial resistance: tackling a crisis for the future health and wealth of nations. http://amr-review.org

- Thomas D, Surdin-Kerjan Y. Metabolism of sulfur amino acids in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1997;61:503–532. doi: 10.1128/.61.4.503-532.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turnbull AL, Surette MG. Cysteine biosynthesis, oxidative stress and antibiotic resistance in Salmonella typhimurium. Res Microbiol. 2010;161:643–650. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2010.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Eichhorn JRP, Leisinger TE. Sulfonate-sulfur metabolism and its regulation in Escherichia coli. Arch Microbiol. 2001;176:1–8. doi: 10.1007/s002030100298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verma D, Gupta S, Kaur KJ, Gupta V. Is perturbation in the quaternary structure of bacterial CysE, another regulatory mechanism for cysteine synthesis? Int J Biol Macromol. 2018;111:1010–1018. doi: 10.1016/J.IJBIOMAC.2018.01.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verma D, Antil M, Gupta V. Recombinant production of active Streptococcus pneumoniae CysE in E. coli facilitated by codon optimized BL21(DE3)-RIL and detergent. Prep Biochem Biotechnol. 2019;49(4):368–374. doi: 10.1080/10826068.2019.1573194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verma D, Gupta S, Saxena R, et al. Allosteric inhibition and kinetic characterization of Klebsiella pneumoniae CysE: an emerging drug target. Int J Biol Macromol. 2020;151:1240–1249. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.10.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warrilow AGS, Hawkesford MJ. Modulation of cyanoalanine synthase and O-acetylserine (thiol) lyases A and B activity by β-substituted alanyl and anion inhibitors. J Exp Bot. 2002;53:439–445. doi: 10.1093/jexbot/53.368.439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westrop GD, Goodall G, Mottram JC, Coombs GH. Cysteine biosynthesis in Trichomonas vaginalis involves cysteine synthase utilizing O-phosphoserine. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:25062–25075. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M600688200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams RAM, Westrop GD, Coombs GH. Two pathways for cysteine biosynthesis in Leishmania major. Biochem J. 2009;420:451–462. doi: 10.1042/bj20082441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wirtz M, Berkowitz O, Droux M, Hell R. The cysteine synthase complex from plants: mitochondrial serine acetyltransferase from Arabidopsis thaliana carries a bifunctional domain for catalysis and protein-protein interaction. Eur J Biochem. 2001;268:686–693. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2001.01920.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wirtz M, Birke H, Heeg C, et al. Structure and function of the hetero-oligomeric cysteine synthase complex in plants. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:32810–32817. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.157446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeon JY, Yoo SJ, Takagi H, Kang HA. A novel mitochondrial serine O-acetyltransferase, OpSAT1, plays a critical role in sulfur metabolism in the thermotolerant methylotrophic yeast Ogataea parapolymorpha. Sci Rep. 2018;8:2377. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-20630-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yi H, Dey S, Kumaran S, et al. Structure of soybean serine acetyltransferase and formation of the cysteine regulatory complex as a molecular chaperone. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:36463–36472. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.527143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoneyama H, Katsumata R. Antibiotic resistance in bacteria and its future for novel antibiotic development. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2006;70:1060–1075. doi: 10.1271/bbb.70.1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang R, Lin Y. DEG 5.0, a database of essential genes in both prokaryotes and eukaryotes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:D455–D458. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zocher G, Wiesand U, Schulz GE. High resolution structure and catalysis of O-acetylserine sulfhydrylase isozyme B from Escherichia coli. FEBS J. 2007;274:5382–5389. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2007.06063.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]