Abstract

The current study aims to examine the effect of age and gender of users on spirituality by using an experiment. Literature believes that age and gender have a huge effect on increased or decreased spirituality. The current study aims to examine these theories by a scientific and rational method and using cognitive neuroscience (recording electroencephalograph). In order to do this, an electroencephalograph was recorded for 45 users. Findings show that there is a significant relationship between age and gender of users and spirituality (F = 4.1, p < 0.05) (F = 3.8, p < 0.05). Results showed that users at older ages reached spirituality sooner. Thus, it can be said in regard to the relationship between age and formation/improvement of spirituality that users at older ages reach spirituality sooner than users at younger ages. Results of data analysis showed that alpha and theta brain signals increased in male students at the 30–35 age range; while this increase was slower at the 20–29 age range.

Keywords: Spirituality, Age and gender, EEG, Cognitive neuroscience, Neuroscience of religion, Mosques

Background

The relationship between gender and spirituality is one of great interest. Many scholars grasp to understand this interaction. Most agree that women tend to be more religious than men (Hammermeister et al 2005a).

Spirituality is a global phenomenon and everyone experience it. The concept of spirituality has different meanings depending on the cultural and philosophical background. Further research is suggested in this area, especially in the Islamic–Iranian context (Razaghi et al 2015). Spirituality is embedded within culture (Cobb 2001; Lewis 2008; Loewenthal et al 2001), where culture is understood as a system of ideas, rules, meanings, and ways of living and thinking that are built up, shared, and expressed by a particular group of people, often of the same ethnic background (Selman et al 2011). Religious buildings have a significant role in Muslims’ culture. The architects have developed some features in designing such buildings that create a unique sense of comfort and spiritual state in humans (Sadeghi Habibabad et al 2020a). Spirituality is a lost human concept and meaning in the universe that is independent of time and place. It is an inclusive concept, which affects everyone (MahdiNejad et al 2019). Spirituality takes place on the basis of human belief in the unseen world and the supernatural universe and giving the originality to the inner world (MahdiNejad et al 2020). As Allameh Tabatabai says: “The inner world is the home of spiritual life; it is a universe much mororiginal more realistic and wider than the world of matter and sense.” (Sadeghi Habibabad et al 2019).

Spirituality is an important issue that is related to the soul and it is one of the important factors and components for making the spiritual atmosphere in Islamic mosques. Spirituality refers to a wide range of environmental feelings and desires for meeting the mental and transcendental needs of humans. In human psychology, spirituality has always been considered an important issue. Authors of this field have written various books in this regard (Schneider et al 2001). Spirituality is related to all domains of health at all ages (Smith 2004). Spirituality is the origin of meaning and goal in life (Gomez 2003) and it is characterized by consistency in life, peace, close relationship with self, God, society, and environment; and harmony (Karimi 2011).

Spiritual architecture of mosques

Since Islam period, mosque has been the most important urban element, architecture and the center of crystallization of the highest forms of creativity, taste and attitude of Muslim architects. Iranian architecture of the Islamic period is inspired by sacred symbols and signs that do not consider the architectural space apart from religious values and is of great importance in the topic of urban design, architecture and environmental psychology.

Muslim mosques, which are a prominent and obvious manifestation of art in a blessed and sacred area, have long been the ceator of the basis of historical, social, political and other events. The Iranian mosques of the Islamic period are the manifestation of the divine beauties and a clear example of the combination and connection of symbolic forms with deep beliefs. Pattern forms and symbolic connections are clearly observed in all aspects and symbols of mosques. Among the evolved organs of mosques architecture and in investigating architectural morphology, the four spaces of minaret, porch, courtyard and dome can be named as the main components of the mosque. For example, in order to examine the relationship between form and meaning, we will suffice with the concept of dome: a dome transforming the architectural form from four to a circle, has relationship with symbolic aspect in the relationship between meaning and form.

The Iranian architecture of the Islamic period has long been a body suitable for responding to the users and the context for the mental and spiritual excellence of human beings, that the peak of this art can be searched in the sacred architecture of mosques of the Islamic period. In addition to sacred ideas, this spiritual identity has also been physically and functionally responsive to its users.

Spirituality

Religion and spirituality are similar but not identical concepts. Religion is often viewed as more institutionally based, more structured, and involving more traditional rituals and practices. Spirituality refers to the intangible and immaterial and thus may be considered a more general term, not associated with a particular group or organization. It can refer to feelings, thoughts, experiences, and behaviors related to the soul or to a search for the sacred.

Many researchers have demonstrated that spirituality plays a significant role in the lives of people, their thoughts, and behaviors (Hadzic 2011). Spirituality is a term often used in psychological literature, but the definition of spirituality, including its distinctiveness as a construct separate from religiousness, continues to be debated (Bauer et al. 2019). Literature believes that spirituality can be measured; however, difficulties shouldn’t be ignored in this regard (Sherman 2001; Plante 2001; Selman 2011; King 2004). In his theory, Piedmont (1999) states that spirituality is considered in a framework of motivational approach or personal characteristics and it is believed that spirituality is a quality that originates from body and forces organism to move; thus, it can be measured (Piedmont 1999). Spirituality has been considered as the forgotten aspect of mental health (Schroder 2003). Spirituality has been interpreted as the deep relationship of the person with the world and it is the spiritual domain of human experience (Culliford 2005). Spirituality refers to a human being's subjective relationship (cognitive, emotional, and intuitive) to what is unknowable about existence, and how a person integrates that relationship into a perspective about the universe, the world, others, self, moral values, and one's sense of meaning (Senreich 2013). Spirituality was primarily viewed as an integral part of one's identity and the personal experience of the transcendent whether it is defined traditionally as God or a higher power, or in more secular terms as unity with the greater world or mystery (Gall et al 2011).

Spirituality is a global human phenomenon (Chiu 2004) and it is experienced by any human being (Miner-Williams 2006). Being spiritual is part of every human being (Tanyi 2002). Spirituality is attributed to beliefs and actions laid on the foundation of the idea that there are sublime (and not physical) dimensions in life that place the human beings in a private and sincere relationship with God and forming a domain of virtues in them (Newlin 2002).

The architecture of a religious and spiritual place has characteristics, which in addition to its form, has a shared link with the main foundations of life and spiritual attitude and the human soul. Spirituality is the active and dynamic aspect of the soul which is independent of form and shapes (MahdiNejad et al 2019). These shapes in which spiritual energy flows within them reflect a divine sense which gives a sacred quality (spirituality) to structure (Pei-Lin 1996). Moreover, this type of structure is made based on a geometry that allows the appropriate flow of this energy (Simpson 2007). Thus, the architecture of scared structures has always been related to the precise and deliberate system of geometrical measurements, proportions, and relationships. This deliberate geometry allows the transfer and flow of sacred energy (Gordon 2009; Macchia 2008; MahdiNejad et al 2019). Architecture has been the creator of sacred place over the millennia; thereby an architect has tried to build a manifestation of the truth on the earth. Mosques in the history of Iran’s architecture have always been in the culmination of Islamic art and architecture. The architecture of the mosques seeks to receive an inspiration from the concepts of divine word to create a space which joins the heavenly world to material world and create a single spiritual environment.

Neurobiology of spirituality

As one of the new neurosciences, neuroscience theology has raised many debates among contemporary scholars. Neurotheology believes that all of the inner experiences of humans are based on an evolutionary and neurological basis.

Neurotheology (also known as the neuroscience of religion) addresses the relationship between the human brain and religion (Aaen-Stockdale 2012). Neuroscience of religion is also known as neurotheology and spiritual neuroscience (Biello 2007), which explains the experience and religious behaviors using neurological measures (Aaen-Stockdale 2012). This study aims to examine the correlation between neurological phenomena and mental experiences of spirituality using some hypotheses to explain this phenomenon. This science differs from the religion psychology that studies mental issues, neurological cases. Advocators of religious neurology argue that there is a neurological and evolutionary context for mental experiences, which are categorized as spiritual or religious issues. Such a context has been used to write several scientific books (Austin 1999).

Both praying and meditating are associated with decreased activity in the parietal lobes; which are responsible for the processing of temporal and spatial orientation. No matter each person’s religious beliefs (or lack of them, for that matter); one can’t deny that the effects of religion on the brain must be interesting to learn about. In fact, some religious beliefs are based on scientific facts that can be measured accurately. The perceived conflict between religion and science has been standing for decades now; from lectures in ancient Greek pantheons to discussions in Internet forums. the effects of religion on the brain will always depend on the kind of religious practice we’re referring to. In other words, different religions activate different brain areas.it doesn’t matter if we’re referring to a Buddhist who meditates or a Catholic nun who prays. After all, they both have greater activity in the frontal lobes of the brain.

Thanks to neuroimaging technology, neuroscientists are attempting to explore the neurological foundations of religious and spiritual experiences (Jastrzebski 2018). Andrew Newberg advocates calling this field of neuroscience ‘neurotheology’, a term that was first popularized by James Ashbrook, a theologian who studied neuroscience (Jastrzebski 2018). The recently expanding field of research exploring the neuroscience of religious and spiritual practices and associated experiences has raised important issues regarding the validity, importance, relevance, and need for such research (Newberg 2014). Spiritual practices have shown definite neuroanatomical and neurochemical changes in the few studies that have been conducted so far to explore the neurobiology of such phenomenon (Mohandas 2008).

Spirituality and religion are not interchangeable or always linked. Therefore a person may have religion without spirituality or spirituality without religion. It is noted that spirituality can have both positive and negative effects on physical health, mental health and coping (Mohandas 2008). Neuroscience of religion is the attempt to describe and explain religious thought and behavior at the level of the brain. Unlike Cognitive Science of Religion (CSR), which mainly seeks to model the cognitive mechanisms involved in religious thought and behavior, and Evolutionary Psychology of Religion (EPR), which attempts to uncover the selection pressures that may have led to those mechanisms, Neuroscience of Religion aims to identify the neurobiological substrates of such mechanisms (Schjødt 2019). Eurobiological changes associated with religious and spiritual practices can be observed through a number of techniques that each have their own advantages and disadvantages (Newberg 2014). Early studies of meditation practices often used electroencephalography (EEG) which measures the electrical activity in the brain (Banquet 1973; Hirai 1974; Hebert and Lehmann 1977; Corby et al 1978). EEG is valuable because it is relatively non-invasive and has very good temporal resolution, although it can suffer from artifact related to the skull or scalp. Overall, EEG has continued to be useful in the evaluation of specific meditation states (Newberg 2014; Lehmann et al 2001; Aftanas and Golocheikine 2002; Travis and Arenander 2004).

Effect of age and gender on spirituality

Gender and spirituality are two sociological concepts that have received considerable attention from sociologists in this era. Accordingly, expanding movements for women's rights besides religious movements worldwide have led to great attention to these two phenomena and the correlation between them. Traditional attitude emphasizes the natural differences between men and women and confirms the inherent virtue and superiority of men compared to women based on the mentioned differences. As men and women are different physically, there is a mental difference between them also from the viewpoint of psychology in different cultures. Such differences are not just caused by the environment and upbringing conditions. The brain of a woman is organized in a way that she can express her feelings more effectively; hence, it is necessary to talk about women. Many think about his thoughts first then decide to speak while a woman can feel, think, and speak at the same time. Women are more willing to be religious than men are. Women find spiritual issues more adaptable to their minds.

Azad Armaki states in his book entitled "sociology of cultural changes in Iran," "women are more religious than men in the field of religious beliefs and affections. However, this is a minor difference that does not lead to any significant correlation. Nevertheless, women do more religious practices such as prayer. Accordingly, 9.89% of women and 4.85% of men always pray while 5.5% and 7.2% of men and women do not pray, respectively. Congregational prayer is a collective religious rite. Men pray in congregation significantly more than women (6.28% men versus 3.21% women). Also, the number of women is greater than men in the relationship between gender and performance of religious authorities in the context of accountability of religious authorities in different cases. Statistics indicate that some men and women assume that religious authorities are capable of answering their religious questions. Accordingly, 6.82% of women and 4.76% of men believe that religious authorities can answer their questions related to ethical issues and personal needs. Furthermore, 5.76% of women and 9.70% of men believe that religious authorities can answer their questions related to family issues. 2.77% of women and 5.72% of men believe that religious authorities can answer their questions related to the spiritual issues of people. About 3.66% of women and 6.58% of men assume that religious authorities can answer their questions related to the social issues of the country. The abovementioned statistics are accepted at a certain significance level.” (Azad Armaki and Ghiasvand 2004).

Moreover, Serajzadeh carried out a study under the title of “Religion and Social Discipline: The Relationship between Religiosity and Anomalous Experiences” to explain why women are more religious than men (Serajzadeh and Poutafar 2008).

A substantive and growing body of empirical research demonstrates the salience of spirituality and religiousness as stand-alone psychological constructs (Hill and Pargament 2008; Kapuscinski and Masters 2010; Slater et al 2001). A gender approach to spirituality does more than give a voice to female authors or record data concerning male or female participation; it reflects on the powerful consequences of divisive and dichotomous thinking and pleas for solidarity and for a more prominent and positive place for experiences of corporeality in spiritual life, anchored in the daily life of men and women across the world (Draulans 2011).

In a study by Shahroudi et al. (2014), gender was realized as one of the determinants of the favorability of the mosques’ contextual indices from the perspective of the users; this study sought figuring out the significant and meaningful relationship between gender and architectural designs of mosques with the objective of elevating the satisfaction in all the user groups, particularly women, and enhancing their sense of spirituality in mosque spaces by taking the women’s physical and psychological needs into consideration during architectural designing of the mosques. The study findings indicated that the physical factors play a determinative role in the overall sense of the users when watching the seraglio as well as when saying prayers. In this regard, the more the physical factors are favorable, the more significant would be their effect on the users’ psychological tranquility and feeling pleasantness in the spaces (Sadeghi Habibabad et al 2020b).

Research literature suggests that there are age and gender effects on numinous constructs, but little is known about how spirituality and religiousness evolve over time and differ between genders. although the expression of spirituality and religious sentiments may vary across age and between genders, the fundamental meaning of these constructs remains the same (Brown et al 2013). Levels of spirituality and reli- giousness appear to rise over the late adoles- cent and adult life course (Brown et al 2013). According to a Gallup Poll conducted in November and December 2002*, spiritual commitment generally increases as age increases—that is, younger people are less likely to be fully spiritually committed than older people. Likely reasons for this include a number of "stage of life" issues (Winseman 2003). Most current research indicates that women are more religious than men (Rich 2012a, b). Women are about twice as likely as men to be fully spiritually committed, both in the general population (17– 8%) and within faith communities (22–11%). Culturally, it may be more acceptable for women to explore the inner life of spirituality – hence the higher proportion of spiritually committed women (Winseman 2003).

Buchko (2004) in a single university in the USA among European Americans. She found that women reported more prayer and meditation time than men did, sensed more of God’s activity and presence in day-to-day life, and reported more feelings of devotion and reverence than men. women are more religious than men; religiosity is not equal in different religions; women living in patriarchal families adhere to religious values and are more religious (Modiri 2013). girls were more likely than boys to demonstrate a higher level of spirituality score (Lee et al, 2019).

Hammermeister et al. (2005a) surveyed 435 college students with the Spiritual Well-Being Scale. They found females to have scored higher than males on all three indices of spiritual wellbeing, religious wellbeing and existential wellbeing. Byrant (2007) surveyed a representative sample of freshmen in 434 colleges and universities in the USA. After three years, Byrant surveyed a subset of the initial sample to determine the effect of college life on students’ spirituality. Byrant’s (2007) results demonstrated that women scored higher than men on religiosity. The difference between women and men on religious practice (22% versus 18% respectively) was smaller than it was on religious belief (35% and 27%, respectively). Women had higher spirituality scores than men.

Women are socialized to be more religious than men in conjunction with expectations that they may be more nurturing and/or dutiful, which some believe are also traits commonly associated with religion (Stark 2002). Studies have shown that women are more likely than men to seek religious consolation (Ferraro and Kelley-Moore 2000). Recent population surveys reveal that, among both Christian and non-Christian populations, women are more likely than men to affiliate with religious institutions, to pray, to say religion is important in their lives, to read religious texts, and to believe in life after death (Stark 2002).

Gender differences in spirituality are not limited to adults but have been found to exist amongst adolescents as well. According to the National Longitudinal Survey of Adolescent Health (1994), among youth who profess no religion, 55% are male and 45% are female. Six percent more females than males attend church regularly. Five percent more males than females do not attend church at all. Among 12th graders, 14% more males than females have never been involved in a religious youth group. 28% of 12th grade girls have been involved in a religious youth group all throughout high school, while only 22% of 12th grade boys can say the same (Rich 2012a, b).

The association between a sense of spirituality and brain waves

Religious actions activate an orbit, also known as the brain's religious cross (frontal lobe), in brain sites such as Amygdala and Hippocampus, Limbic system, anterior temporal lobe, orbitofrontal, and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. Moreover, long-term religious actions activate frontal lobes (Soufian 2011).

Meditation, prayer, and or other spiritual performances require continuous attention and mindfulness. Such ever-lasting attention can be paid by focusing on the imagination of religious art, spiritual actions, and prayer. Many brain imaging-based studies indicate that voluntary and planned activities and duties require uninterrupted attention. Such activities initiate from activation in the prefrontal cortex (PFC), especially on the right side of the brain.

Religious experiences and "spiritual sense" in the human brain are similar actions in the context of cognitive neurosciences. Most of the ethical reactions of human beings, such as patience, honesty, justice, and fairness, avoid anger and nervousness are inhibitory behaviors. Accordingly, when it is about self-control in religion, it is indeed about inhibition of emotional and limbic systems in cognitive neurosciences (McNamara and Wildman 2008).

Neurologists showed that the parietal area of the brain affects the sense of "unity with the world" (Soufian 2011). They believe that the brain structures of humans create spiritual passion (Newberg et al 2003).

Results of testing Franciscan monks and Tibetan Buddhists through positron emission topography indicated increased activity in frontal lobes and declining activity in the posterior upper parietal lobe (Soufian 2011) at the end of meditation (Persinger 1983).

According to conducted studies, not only one part of the brain relates to religious actions, but there are various structures of the brain which associates with this function (Majidzadeh Ardabili et al. 2018). According to brain imaging results, different parts of the brain such as the right medial orbitofrontal cortex, the right temporal lobe, right superior and inferior parietal lobules, the right caudate nucleus, left prefrontal cortex and left anterior cingulate cortex are in relation with religious actions and spirituality (Beauregard 2006).

Alpha brainwaves

Alpha brainwaves occur when the person is conscious and alert and calm and self-possessed. In a relaxed mental state, the person can achieve creative ideas more simply. According to the report given by therapist “Patt Lind-Kyle" in her book "Heal Your Mind, Rewire Your Brain: Applying the Existing New Science of Brain Synchrony for Creativity, Peace, and Presence," the right side of your brain is more active when alpha waves are emitted, and the left side of it is more active when beta waves are emitted. When both sides of the brain are synchronized, you are in a peaceful state. Alpha waves increase feelings such as thinking, peace, relaxation, and tranquility (Essawy 2014). Alpha waves are increased in the rain during a relaxed state while spiritual feelings indicate that there has been an increased frequency of alpha in the frontal lobe. The exact part of this phenomenon begins from the prefrontal cortex (particularly in the right hemisphere) (Paloutzian 2014). Hence, it should be noted that when spirituality is formed in person, the relaxation consequences also can be seen. Nevertheless, the reverse impact does not exist.

Theta brainwaves

This amplitude of the wave is generated during sleep and dreams. Theta waves cause some profound emotional experiences in relationships the person makes with others and create a profound sense of peace. Theta waves work to improve insight and creativity. Stimulation of the sixth sense can be applied as one way to boost beta waves. The sixth sense is indeed an area for energy accumulation that is located in the frontal part of the brain between two eyebrows. The most instant way to improve this area is prostration. In a relaxation state, Theta waves are increases throughout the head areas. However, the spiritual sense has been formed when there is an increase in Theta frequency in the frontal lobe. Besides, the exact part of this phenomenon begins from the prefrontal cortex (particularly in the right hemisphere) (Paloutzian 2014). Hence, it should be noted that when spirituality is formed in person, the relaxation consequences also can be seen. Nevertheless, the reverse impact does not exist.

Methods

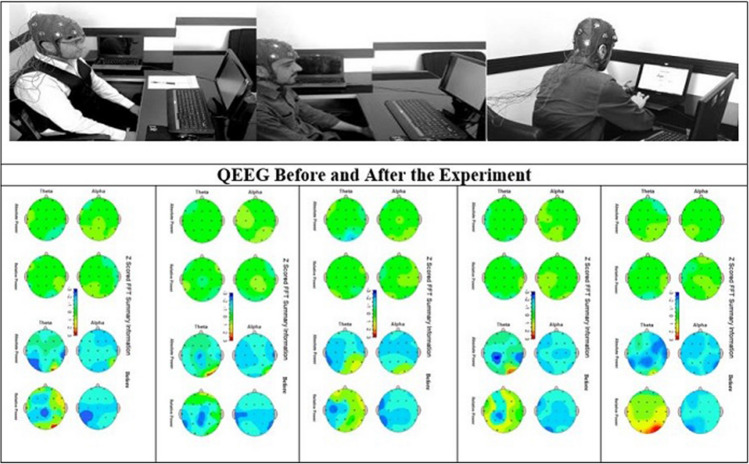

The experimental method is used in the current study. The sample size is 45 (23 males and 22 females). The age range is 20–35 years. Before the experiment, written consent was taken from all users and they completed the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ). Brain waves of users were recorded when watching images of Islamic mosques on a monitor. Electroencephalograph (EEG) was used to analyze data.

EEG (EBNeouro, Italy) device was used to record brain waves. Electronic waves of the brain were recorded in a sitting position by using Nuprep gel and standard cap. A trained operator recorded EEG, installed electrodes, and extracted data. Then, EEG artifact was removed and absolute power output (sq/µv) was extracted by software, using the FFT method. NeuroGuide, 3.0.7.0 software was used to analyze signals.

Ten electrodes including area (1Fp, 2Fp, 3F, 4F), area (3 T, 4 T), area (Q1, Q2), and area (Fz, Pz) were considered for realizing feelings. These 10 electrodes were selected based on the comments of experts and studied resources (Sourina 2011). Moreover, received signals of these electrodes from the right ear and left ear were considered as device field.

Analysis and findings

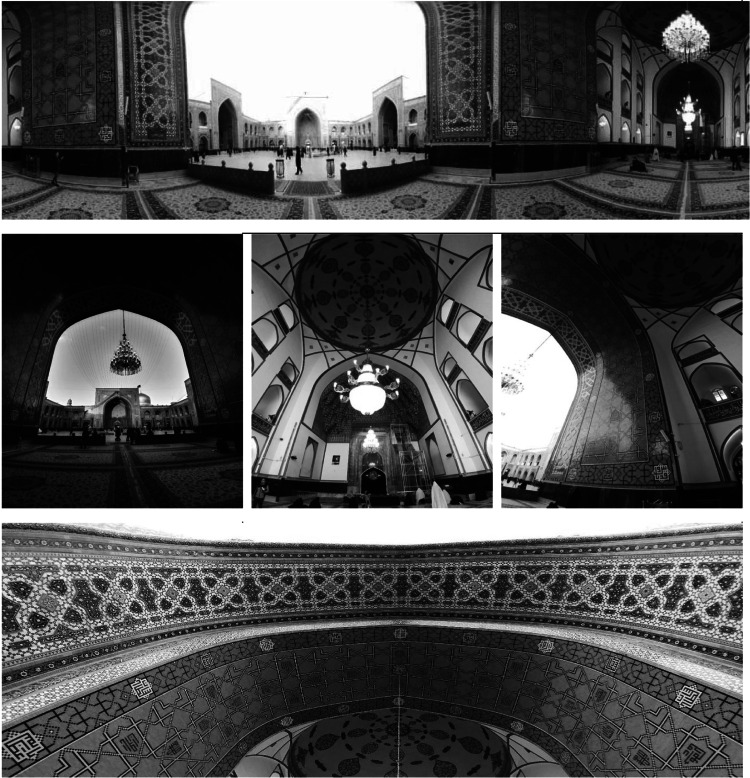

After measuring changes in the mean and standard deviation of alpha (α) and theta (θ) signals, results showed that mean alpha waves increased in 91.24% of users and decreased in 8.67% of users after watching images of Islamic mosques (Goharshad Mosque) (Fig. 1). Moreover, the range of theta parameters increased by 82.39% of users and decreased to 17.61% of users. Figure 2 shows the brain map (QEEG) for 5 users before and after the experiment (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

A 360-degree image of Goharshad Mosque, Mashhad. Iran. (

Source: Authors)

Fig. 2.

QEEG map for brain waves of users before and after watching images of Islamic mosques (5 users as an example)

Wave recording was done using a EEG device, filter adjustment options, and automatic calibration mechanism. The electrodes were placed as caps using a special gel for electronic conduction and recording accuracy. The image of the mosque was rotated 360 degrees through a 30-degree angle monitor (Hwang 2007) (Asgarzadeh 2012) in front of the people.

The changes and fluctuations of brainwaves in those seeing the images of the mosque were different from the data before doing so (normal brainwaves before seeing the images) (Sadeghi Habibabad et al 2020a). Alpha wave fluctuations of the human brain while presenting emotional stimuli and comparison with the resting state of the frontal part of the brain were first done by Davidson in 1979 (Sadeghi Habibabad et al 2020b). Brain theta waves emit between 4 and 7 Hz. The only state below this frequency is the Delta waves: which is a deep, dreamless state (it is even difficult for Zen masters to stay alert at these levels). When human brain produces theta waves, the person feels a deep sense of relaxation (Habibabad et al. 2020). However, Dr. Basar, one of the world’s most famous biofeedback researchers, argues that brain theta waves produce a “detached relaxation” whose results vary “from sleepiness, hypnosis-like states to seeing brilliant and pseudoHologram” (Basar 2012).

One of the most measurable effects over a short period is anxiety shown in the frequency of brainwaves (Essawy 2014). The strong negative correlation between peak frequency and theta/beta ratios in both experimental conditions in Goharshad Mosque was vividly seen. Those showing an increase in energy levels at higher frequencies had a lower theta-beta ratio as well. However, the subjects showed a lower level of theta-to-beta ratio and a higher alpha peak frequency (healthier EEG). Theta-to-beta, alpha peak, and peak frequencies were measured to specify the relationship between subject brain modes using EEG (Sadeghi Habibabad et al 2020a).

It can be said based on Table 1 and Fig. 3 that brain activity has a significant relationship with spirituality and gender of users (F = 4.1, p < 0.05). In fact, reaching spiritual forms depends on the gender of users. This finding is consistent with Tabaeian et al (2018) and Brown et al (2013). The above figure shows that women reach spirituality sooner than men. These observed differences parallel findings in the research literature, where women consistently score higher than men on measures of spirituality and religious involvement (Wink and Dillon 2002; Maselko and Kubzansky 2006).

Table 1.

Analysis of variance for examining activity differences in brain waves (gender and spirituality)

| Standard deviation | Average | Number of samples | Gender | Time to start spirituality / second | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3.02 | 12.02 | (23–1) | Men | (0–20) A | |

| 4.85 | 18.11 | 22 | Women | ||

| 4.70 | 16.21 | (23–1) | Men | (21–40) B | |

| 4.65 | 13.92 | 22 | Women | ||

| Theta waves | Mean sum of squares | Sum of deviant scores squares | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spirituality | 41.89 | 41.89 | F value | p value | P < 0.05 |

| Gender | 82.01 | 82.01 | 4.3 | 0.004 | Significant |

| Spirituality and gender | 75.63 | 75.63 | 4.1 | 0.01 | Significant |

Fig. 3.

Comparison of mean time to reach mindfulness (spirituality) in men and women

FIt can be said based on Table 2 and Fig. 4 that brain activity has a significant relationship with spirituality and the age of users (F = 3.8, p < 0.05). In fact, reaching spiritual forms depends on the age of users. This finding is consistent with Tabaeian et al (2018) and Brown et al (2013). The above figure shows that users with higher age reach spirituality sooner than men.

Table 2.

Analysis of variance for examining activity difference in brain waves (age and spirituality)

| Standard deviation | Average | Number of samples | Age | Time to start spirituality / second | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4.20 | 13.28 | (23–1) | (20–29) | (0–20) A | |

| 4.90 | 16.85 | 22 | (30–35) | ||

| 5.10 | 17.47 | (23–1) | (20–29) | (21–40) B | |

| 3.90 | 12.66 | 22 | (30–35) | ||

| Theta waves | Mean sum of squares | Number of samples | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spirituality | 40.89 | 40.89 | F value | p value | P < 0.05 |

| Gender | 80.98 | 80.98 | 4.1 | 0.006 | Significant |

| Spirituality and gender | 76.12 | 76.12 | 3.8 | 0.02 | significant |

Fig. 4.

Comparison of mean time to reach mindfulness (spirituality) at two age ranges

Conclusions

There is a significant relationship between spirituality and users' gender. In fact, reaching spiritual states depends on the gender of the individuals. The results show that women reach spiritual state earlier than men. Therefore, according to the recorded data regarding brain signals, there is a significant relationship between users' gender and creating/promoting a sense of spirituality, in a way that women achieve spiritual states earlier than men.

There is a significant relationship between brain activity regarding spirituality and users’ age. In fact, reaching spiritual states depends on the age of the individuals. The results show that people with a higher age range have reached spiritual state earlier. Therefore, regarding the relationship between people's age and creating/ promoting a sense of spirituality, it can be stated that people with higher age achieve peace and spiritual sense sooner than people with lower age.

Results showed that women reach spirituality sooner than men. Thus, concerning recorded data on brain signals, there is a significant relationship between gender and formation/improvement of spirituality, such that women reach spirituality sooner than men. It became clear in data analysis that in mean recorded waves, alpha and theta signals increased for female students at first 5–15 s of experiment and male students at first 15–20 s of the experiment. This shows that gender affects the formation/improvement of spirituality, such that women reach spirituality sooner than me. Thus, this point should be considered in designing female special and male special spaces in religious structures.

Results showed that users at older ages reached spirituality sooner. Thus, it can be said in regard to the relationship between age and formation/improvement of spirituality that users at older ages reach spirituality sooner than users at younger ages. Results of data analysis showed that alpha and theta brain signals increased in male students at the 30–35 age range; while this increase was slower at the 20–29 age range. Moreover, this also holds for a female student at the same age ranges.

Obviously, the results of each one of the cognitive tests performed in a real environment become close to reality, but due to time and economic constraints in this article, this was not possible. It is also suggested that for more investigation about the age of users regarding spirituality, the distance of the selected age range increases. Regarding the BCI system, it is also suggested for future researches that by extracting the recorded wave properties, various instructions are proposed in the form of a program or device and provide its feedback to users.

Author contributions

JM and HA contributed to designing the study. AS wrote the manuscript. AS and PM and HA contributed to writing and reviewing the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Funding

No funding was received for this study from any funding agency or organization.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

Informed consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the study women and Man. It was made clear to all subjects that participation was voluntary.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Jamal-e-Din MahdiNejad, Email: Mahdinejad@sru.ac.ir.

Hamidreza Azemati, Email: Azemati@sru.ac.ir.

Ali Sadeghi habibabad, Email: A.sadeghi@sru.ac.ir.

References

- Aaen-Stockdale C. Neuroscience for the Soul. Psychologist. 2012;25(7):520–523. [Google Scholar]

- Aazad Armaki T, Ghiasvand A. Sociology of cultural changes in Iran. Tehran: Aan; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Aftanas LI, Golocheikine SA. Non-linear dynamic complexity of the human EEG during meditation. Neurosci Lett. 2002;330:143–146. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3940(02)00745-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asgarzadeh M, Lusk A, Koga T, Hirate K. Measuring oppressiveness of streetscapes. Landsc Urban Plan. 2012;107(1):1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.landurbplan.2012.04.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Austin JH. Zen and the brain: toward an understanding of meditation and consciousness. Cambridge: MIT Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Banquet JP. Spectral analysis of the EEG in meditation. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1973;35:143–151. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(73)90170-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basar E. A review of alpha activity in integrative brain function: Undamental physiology, sensory coding, cognition and pathology. Int J Psychophysiol. 2012;86(1):1–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2012.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer AS, Johnson TJ. Conceptual overlap of spirituality and religion: an item content analysis of several common measures. J Spiritual Ment Health. 2019;21(1):14–36. doi: 10.1080/19349637.2018.1437004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beauregard M, Paquette V. Neural correlates of a mystical experience in carmelite nuns. Neurosci Lett. 2006;405(3):186–190. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2006.06.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biello D. Searching for god in the brain. Sci Am Mind. 2007;18(5):38. doi: 10.1038/scientificamericanmind1007-38. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brown IT, Chen T, Gehlert NC, Piedmont RL (2013). Age and gender effects on the assessment of spirituality and religious sentiments (ASPIRES) scale: a cross-sectional analysis. Psychol Relig Spiritual, 5(2), 90. https://psycnet.apa.org/fulltext/2012-27377-001.html

- Bryant AN (2007). Gender differences in spiritual development during the college years. Sex Roles, 56(11–12), 835–846. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs11199-007-9240-2

- Buchko KJ (2004). Religious beliefs and practices of college women as compared to college men. J Coll Stud Dev, 45(1), 89–98. https://muse.jhu.edu/article/52879.

- Chiu L, Emblen JD, Van Hofwegen L, Sawatzky R, Meyerhoff H (2004). An integrative review of the concept of spirituality in the health sciences. West J Nurs Res, 26(4), 405–428. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15155026. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Cobb M. The dying soul: spiritual care at the end of life. UK: McGraw-Hill Education; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Corby JC, Roth WT, Zarcone VP, Jr, Kopell BS. Psychophysiological correlates of the practice of tantric yoga meditation. Arch Gen Psych. 1978;35:571–577. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1978.01770290053005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Culliford L (2005). Healing from within: spirituality and mental health. Retrieved on Mar, 1, 2009. http://www.multifaiths.com/pdf/HealingFromwithin.pdf

- Draulans V (2011) Gender and spirituality. In: Bouckaert L, Zsolnai L (eds) Handbook of spirituality and business. Palgrave Macmillan, London. 10.1057/97802303214587

- Essawy S, Kamel B, El-Sawy MS (2014). Sacred buildings and brain performance: the effect of sultan hasan mosque on brain waves of its users. http://dspace.chitkara.edu.in/xmlui/handle/1/24

- Ferraro KF, Kelley-Moore JA. Religious consolation among men and women: do health problems spur seeking? J Sci Study Relig. 2000;39:220–234. doi: 10.1111/0021-8294.00017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gall TL, Malette J, Guirguis-Younger M. Spirituality and religiousness: a diversity of definitions. J Spiritual Ment Health. 2011;13(3):158–181. doi: 10.1080/19349637.2011.593404. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez R, Fisher JW. Domains of spiritual well-being and development and validation of the spiritual well-being questionnaire. Personal Individ Differ. 2003;35(8):1975–1991. doi: 10.1016/S0191-8869(03)00045-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon J. Is a sense of self essential to spirituality? J Relig Disabil Health. 2009;13(1):51–63. doi: 10.1080/15228960802581438. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hadzic M. Spirituality and mental health: current research and future directions. J Spiritual Ment Health. 2011;13(4):223–235. doi: 10.1080/19349637.2011.616080. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hammermeister J, Flint M, El-Alayli A, Ridnour H, Peterson M (2005). Gender differences in spiritual well-being: are females more spiritually-well than males? Am J Health Stud, 20.

- Hebert R, Lehmann D. Theta bursts: an EEG pattern in normal subjects practising the transcendental meditation technique. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1977;42:397–405. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(77)90176-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill PC, Pargament KI. Advances in the conceptualization and measurement of religion and spirituality: Implications for physical and mental health research. Psychol Relig Spiritual. 2008;5:3–17. doi: 10.1037/1941-1022.S.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirai T. Psychophysiology of zen. Tokyo: Igaku Shoin; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang T, Yoshizawa N, Munakata J, Hirate K (2007). A study on the oppressive feeling caused by the buildings in urban space Focused on the physical factors corresponding with oppressive feeling. J Environ Eng (Transaction of AIJ, (616), 25–30. https://jglobal.jst.go.jp/en/detail?JGLOBAL_ID=200902257640249040

- Jastrzebski AK. The neuroscience of spirituality. Pastoral Psychol. 2018;67:515–524. doi: 10.1007/s11089-018-0840-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kapuscinski AN, Masters KS. The current status of measures of spirituality: a critical review of scale development. Psychol Relig Spiritual. 2010;2:191–205. doi: 10.1037/a0020498. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Karimi L Shomoossi N, Safee Rad I, Ahmadi Tahor M (2011). The relationship between spiritual well-being and mental health of university students. J Sabzevar Univ Med Sci, 17(4), 274–280. http://jsums.medsab.ac.ir/article_46.html

- King JE, Crowther MR. The measurement of religiosity and spirituality. J Organ Change Manage. 2004 doi: 10.1108/09534810410511314. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, Jirásek I, Veselský P, Jirásková M. Gender and age differences in spiritual development among early adolescents. Eur J Dev Psychol. 2019;16(6):680–696. doi: 10.1080/17405629.2018.1493990. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann D, Faber PL, Achermann P, Jeanmonod D, Gianotti LR, Pizzagalli D. Brain sources of EEG gamma frequency during volitionally meditation-induced, altered states of consciousness, and experience of the self. Psychiatry Res. 2001;108:111–121. doi: 10.1016/S0925-4927(01)00116-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis LM. Spiritual assessment in African-Americans: a review of measures of spirituality used in health research. J Relig Health. 2008;47(4):458–475. doi: 10.1007/s10943-007-9151-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loewenthal KM, Cinnirella M, Evdoka G, Murphy P. Faith conquers all? beliefs about the role of religious factors in coping with depression among different cultural-religious groups in the UK. Br J Med Psychol. 2001;74(3):293–303. doi: 10.1348/000711201160993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macchia P. (2008). Understanding the Sensual Aspects of Timeless Architecture.

- MahdiNejad J, Azemati H, Sadeghi Habibabad A. Religion and spirituality: mental health arbitrage in the body of mosques architecture. J Relig Health. 2019 doi: 10.1007/s10943-019-00949-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MahdiNejad J, Azemati H, Sadeghi Habibabad A. Explaining an influential model of the significant relationship between religion, spirituality, and environmental peace in mosque interior architecture. J Relig Health. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s10943-020-00983-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majidzadeh Ardabili K, Rostami R, Kazemi R. Electrophysiological correlates of listening to the recitation of Quran. Neurosci J Shefaye Khatam. 2018;6(2):69–81. doi: 10.29252/shefa.6.2.69. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maselko J, Kubzansky LD. Gender differences in religious practices, spiritual experiences and health: results from the U.S. general social survey. Soc Sci Med. 2006;62:2848–2860. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNamara P, Wildman W. Challenges facing the neurological study of religious behavior, belief, and experience. Method Theory Study Relig. 2008;20(3):212–242. doi: 10.1163/157006808X317455. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Miner‐Williams D (2006). Putting a puzzle together: making spirituality meaningful for nursing using an evolving theoretical framework. J Clin Nurs, 15(7), 811–821. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16879374. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Modiri F, Azadarmaki T (2013). Gender and Religiosity. J Appl Sociol, 24(3), 1–14. http://jas.ui.ac.ir/article_18312.html.

- Mohandas E, (2008), Neurobiology of Spirituality. In: Singh AR and Singh SA (eds.), Medicine, Mental Health, Science, Religion, and Well-being, MSM, 6, Jan– Dec 2008, p63–80. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3190564/

- Newberg AB. The neuroscientific study of spiritual practices. Front Psychol. 2014;5:215. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newberg A, Pourdehnad M, Alavi A, d'Aquili EG. Cerebral blood flow during meditative prayer: preliminary findings and methodological issues. Percept Mot Skills. 2003;97(2):625–630. doi: 10.2466/pms.2003.97.2.625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newlin K, Knafl K, Melkus GDE. African-American spirituality: a concept analysis. Adv Nurs Sci. 2002;25(2):57–70. doi: 10.1097/00012272-200212000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paloutzian RF, Park CL, editors. Handbook of the psychology of religion and spirituality. US: Guilford Publications; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Pei-lin L (1996). On" the spiritual space" of China's historical-cultural villages [J]. Journal Pek Univ Humanit Soc Sci, 1. http://en.cnki.com.cn/Article_en/CJFDTotal-BDZK601.006.htm

- Persinger MA (1983). Religious and mystical experiences as artifacts of temporal lobe function: a general hypothesis. Percept Motor Skills, 57 (3_suppl), 1255–1262. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Piedmont RL. Does spirituality represent the sixth factor of personality? spiritual transcendence and the five-factor model. J Pers. 1999;67(6):985–1013. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.00080. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Plante TG, Sherman AC (Eds). (2001). Faith and health: psychological perspectives. Guilford Press. https://scholarcommons.scu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1036&context=psych

- Razaghi N, Rafii F, Parvizy S, Sadat Hosseini A (2015). Concept analysis of spirituality in nursing. IJN; 28 (93 and 94):118–131. URL: http://ijn.iums.ac.ir/article-1-2153-fa.html

- Rich II A. (2012). Gender and spirituality: are women really more spiritual?.

- Rich II (2012). Gender and spirituality: are women really more spiritual?. https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/honors/281/

- Sadeghi Habibabad A, MahdiNejad J, Azemati H, et al. Using neurology sciences to investigate the color component and its effect on promoting the sense of spirituality in the interior space of the vakil mosque of shiraz (using quantitative electroencephalography wave recording) J Relig Health. 2019 doi: 10.1007/s10943-019-00937-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadeghi Habibabad A, MahdiNejad J, Azemati H. Recording the users’ brain waves in manmade religious environments based on psychological assessment of form in creation/enhancement of spiritual sense. Integr psych behav. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s12124-020-09567-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadeghi Habibabad A, MahdiNejad JED, Azemati H, Matracchi P. Examination of the psychological impact and brainwaves functioning of the users of buildings and environments built based on promoting relaxation and spiritual sense. J Spiritual Mental Health. 2020 doi: 10.1080/19349637.2020.1738311. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schjødt U, van Elk M (2019). The neuroscience of religion. Oxford handbook of the cognitive science of religion.

- Schneider K Bugental J, Pierson J (2001). The handbook of humanistic psychology: leading edges of theory, practice, and research.

- Schroder PJ. Spirituality and mental health care. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 2003;41(9):57–57. doi: 10.3928/0279-3695-20030901-18. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Selman L, Harding R, Gysels M, Speck P, Higginson IJ. The measurement of spirituality in palliative care and the content of tools validated cross-culturally: a systematic review. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2011;41(4):728–753. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2010.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senreich E. An inclusive definition of spirituality for social work education and practice. J Soc Work Educ. 2013;49(4):548–563. doi: 10.1080/10437797.2013.812460. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Serajzadeh SH, Poutafar M. Religion and social discipline: the relationship between religiosity and anomalous experiences. Soc Issues Iran. 2008;16(63):71–105. [Google Scholar]

- Shahroudi A, Hosseini H, Momeni Z (2014) A study of the adaptability rate of mosques architecture with the women’s needs, a case study: mosques of Sari city. Q J Iran Islamic City Stud 18:39–53. http://iic.icas.ir/Journal/Article_Details?ID=150

- Sherman AC, Simonton S (2001). Assessment of religiousness and spirituality in health research. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2001-05098-006

- Simpson K (2007). Spiritual architecture and paradise regained: milton's literary ecclesiology. Duquesne University Press. https://muse.jhu.edu/book/5371

- Slater W, Hall TD, Edwards KJ. Measuring spirituality and religion: where are we and where are we going? J Psychol Theol. 2001;29:4–21. doi: 10.1177/009164710102900102. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smith S. Exploring the interaction of trauma and spirituality. Traumatology. 2004;10(4):231–243. doi: 10.1177/153476560401000403. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Soufian S, Sofian M (2011), Religious experiences in the view of neurology. J Arak Uni Med Sci; 13(5):98–106. URL: http://jams.arakmu.ac.ir/article-1-961-fa.html

- Sourina O, Liu Y (2011). A fractal-based algorithm of emotion recognition from eeg using arousal-valence model. In: Biosignals (pp. 209–214). https://www.scitepress.org/Papers/2011/31518/31518.pdf

- Stark R. Physiology and faith: addressing the “universal” gender difference in religious commitment. J Sci Study Relig. 2002;41(3):495–507. doi: 10.1111/1468-5906.00133. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tabaeian R, Amiri S, Molavi H (2018). Investigating developmental trend of spiritual transcendence from adolescence to elderly: a cross sectional Study. Res Cognit Behav Sci, 7(2), 13–22. doi: 10.22108/cbs.2017.86864.0https://iranjournals.nlai.ir/1513/article_396388.html

- Tanyi, R. A. (2002). Towards clarification of the meaning of spirituality. J Adv Nurs, 39(5), 500–509. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12175360. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Travis F, Arenander A. EEG asymmetry and mindfulness meditation. Psychosom Med. 2004;66:147–148. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200401000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wink P, Dillon M. Spiritual development across the adult life course: findings from a longitudinal study. J Adult Dev. 2002;9:79–94. doi: 10.1023/A:1013833419122. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Winseman AL (2003). Spiritual commitment by age and gender. Gallup Poll Tuesday Brief, 108–108. https://news.gallup.com/poll/7963/spiritual-commitment-age-gender.aspx

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].