Abstract

Poverty is an important predictor of child maltreatment. Social policies that strengthen the economic security of low-income families, such as the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), may reduce child maltreatment by impeding the pathways through which poverty leads to it. We used variations in the presence and generosity of supplementary EITCs offered at the state level and administrative child maltreatment data from the National Child Abuse and Neglect Data System (NCANDS) to examine the effect of EITC policies on state-level rates of child maltreatment from 2004 through 2017. Two-way fixed effects models indicated that a 10-percentage point increase in the generosity of refundable state EITC benefits was associated with 241 fewer reports of neglect per 100,000 children (95% Confidence Interval [CI] [−449, −33]). An increase in EITC generosity was associated with fewer reports of neglect both among children ages 0–5 (−324 per 100,000; 95% CI [−582, −65]) and children ages 6–17 (−201 per 100,000; 95% CI [−387, −15]). Findings also suggested associations between the EITC and reductions in other types of maltreatment (physical abuse, emotional abuse); however, those did not gain statistical significance. Economic support policies may reduce the risk of child maltreatment, especially neglect, and improve child wellbeing.

Keywords: child maltreatment, economics, policy

Introduction

Child maltreatment is an important public health problem in the United States. More than one in three of all US children are estimated to experience a child protective services (CPS) investigation before their 18th birthday (Kim et al., 2017). Over half of all official victimizations occur among children 5 years old or younger (Child Maltreatment, 2017), a particularly sensitive time for child development during which the foundations for lifelong health are laid (Braveman & Barclay, 2009). Adverse health consequences linked to child maltreatment span the life course and include immediate physical injuries, delayed cognitive development, mental health problems, and increased drug and alcohol use in adolescence and adulthood (Hussey et al., 2006; Springer et al., 2007). Childhood maltreatment is among the leading causes of premature death in the United States (Felitti et al., 1998). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention researchers estimate that the annual economic burden due to substantiated child maltreatment exceeds $400 billion (in 2015 dollars) (Peterson et al., 2018), highlighting the need for effective prevention strategies.

Incidence of child maltreatment occurs along a socioeconomic gradient (Berger, 2004; Pelton, 2015) on which low-socioeconomic-status children have maltreatment rates that are five times that of other children (Sedlak et al., 2010). Given strong evidence of a persistent link between poverty and child maltreatment, some have suggested state and federal policies that improve families’ economic circumstances as a primary prevention strategy (Bullinger et al., 2019; Klevens et al., 2015). Prior research has evaluated policies such as California’s 2004 paid family leave (Klevens et al., 2016), state-level Medicaid expansions under the Affordable Care Act (Brown et al., 2019), and local minimum wage laws (Raissian & Bullinger, 2017), finding associated reductions in rates of pediatric abusive head trauma hospital admissions, Child Protective Services (CPS) substantiated reports of neglect, and overall screened-in CPS reports, respectively. More restrictive, less generous state welfare benefit programs have also been found to be associated with higher rates of out-of-home placements and substantiated cases of maltreatment (Paxson & Waldfogel, 2003).

The EITC is considered the largest anti-poverty program for working parents in the United States (Hoynes & Patel, 2018), yet the EITC’s impacts on child maltreatment remain understudied. The Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) is a refundable tax-credit that was enacted at the federal level in 1975 and has been expanded substantially since that time. In 2019, the federal EITC supplemented the after-tax income of approximately 25 million low-wage US workers and families. Decades of studies consistently find that the EITC achieves its goals of encouraging labor participation and reducing poverty (Eissa & Hoynes, 2006; Hoynes & Patel, 2018). A more recent body of research suggests that the EITC also yields unintended, yet positive, spillover effects on certain health outcomes (Simon et al., 2018). These effects have been found to be strongest for low-income mothers and children and include reductions in low birth-weight births (Hoynes et al., 2015) and infant mortality (Arno et al., 2009), and improvements in mother-rated own and child health (Averett & Wang, 2018; Evans & Garthwaite, 2014).

Many parents report using their EITC lump-sum benefit in ways that meet children’s basic needs: to purchase essential household goods, pay for rent, and pay for child-related expenses such as childcare (Halpern-Meekin et al., 2015). If so, the EITC could reduce the likelihood of neglect, which is typically defined as the failure to provide children with basic necessities such as food and medical care (Berger & Waldfogel, 2011). In addition, the EITC may prevent both neglect and abuse by reducing caregivers’ chronic stress, depression (Boyd-Swan et al., 2016; Lenhart, 2019) and the likelihood that caregivers develop dysfunctional modes of coping, such as substance abuse—a key risk factor for child maltreatment that compromises parent’s ability to provide a safe living environment (Walsh et al., 2003). Prior studies found an association between the EITC and reductions in hospital admissions for pediatric abusive head trauma (Klevens et al., 2016), self-reported behaviors that approximate neglect (Berger et al., 2017), and foster care entries (Rostad et al., 2020).

This study is the first to use administrative data to examine whether living in a state with a refundable EITC, as well as the level of refundable EITC benefits within those states, are associated with child maltreatment report rates. In addition to overall maltreatment rates, we examined multiple forms of child maltreatment. Our hypotheses were that increases in state EITC benefits would be associated with lower rates of child maltreatment, particularly neglect, given the strong conceptual link between poverty and child neglect. In addition, because most child maltreatment occurs to children 5 years old and younger (Child Maltreatment, 2017) we hypothesized that the effects of the EITC could be larger for that age group. Young children are a particularly salient population for this study since a large body of research indicates early childhood as an important developmental stage for future cognitive, social, emotional, and health outcomes (e.g. Shonkoff & Phillips, 2000; Heckman, 2006).

Methods

Data

We combined multiple data sources to create a state panel dataset. Child maltreatment data were obtained from the National Child Abuse and Neglect Data System (NCANDS) Child File. NCANDS is a dataset compiled by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families. NCANDS includes all screened-in reports of child maltreatment (reports that met agency criteria to warrant further investigation) to state and local child protective service agencies across the United States. Reports of suspected child maltreatment are made by both mandatory and voluntary reporters. Mandatory reporters are required by law to report suspected child maltreatment and are typically professionals who have frequent contact with children, such as social workers, law enforcement officers, teachers and school personnel, and physicians and other health care workers. Voluntary reporters are all persons who report suspected child maltreatment without requirement to do so by law.

The NCANDS Child File contains a record for each child maltreatment report, including the state and year in which the report was made, the age of the child, and the type of maltreatment alleged (e.g. neglect, physical abuse, emotional abuse, and sexual abuse). Although NCANDS seeks to obtain a full census of all reports of child maltreatment, some states fail to submit their administrative child maltreatment data to NCANDS in some years. We excluded reports made in the years preceding a state’s failed submission to NCANDS due to concerns about data quality. For further details about missing data contributions to NCANDS see online Appendix Table 1 Note. To construct annual maltreatment rates, we counted children who experienced multiple child welfare investigations in a given year as the subject of only one investigation that year. In total, our main analytic panel dataset contained 689 state-year observations assembled from 42,682,675 reports of alleged maltreatment made in 50 states and the District of Columbia between 2004 and 2017, the most recent year of complete data available.

Child Maltreatment Rates

This analysis considered several child maltreatment outcomes of interest. We first constructed, for each state, the annual overall child maltreatment report rate. We then constructed the annual child maltreatment report rate by one of the four types of maltreatment (neglect, physical abuse, emotional abuse, and sexual abuse). Importantly, indicators of maltreatment type were not mutually exclusive because reports often involved multiple types of maltreatment. These outcome measures included all screened-in reports of child maltreatment (reports that met agency criteria to warrant further investigation), regardless of substantiation status (whether the case met an evidentiary threshold for maltreatment according to state law). Our decision to include both substantiated and unsubstantiated cases in these outcome measures was based on prior studies indicating that substantiated and unsubstantiated cases face similar risks of future re-victimization (Kohl et al., 2009) and risks for future deleterious behavioral, developmental, and health outcomes (Hussey et al., 2005; Kugler et al., 2019). However, we also constructed the annual substantiated maltreatment rate to test the robustness of our main results. A notable share of maltreatment allegations remains unsubstantiated, and thus, could be more indicative of poverty than actual maltreatment (Jonson-Reid et al., 2013). Lastly, for each of these outcomes, we constructed age-specific rates for two child age groups: children ages 0–5 and children ages 6–17. Annual state-level child population data were obtained from the U.S. Census and used to construct rates per 100,000 children.

State Earned Income Tax Credits

We used two variables to capture state EITC policies: 1) a binary variable for whether a state had a refundable EITC in a given year (i.e., presence) and 2) a continuous variable for the percentage of the federal EITC a state offered in a given year (i.e., generosity). Prior studies of state EITC impacts on child maltreatment captured state EITCs with a three-category variable for EITC presence, whether a state offered: a refundable EITC, a non-refundable EITC, or no EITC (Klevens et al., 2016, Rostad et al., 2020). However, over recent decades, states have not only introduced and eliminated EITC programs (i.e. adjusted presence), but also set differential EITC benefit levels for new and existing credits (i.e. adjusted generosity). Measuring state EITCs as the percentage of the federal credit allows us to more fully capture the continuum of EITC benefits available to state taxpayers across states and within states over time.

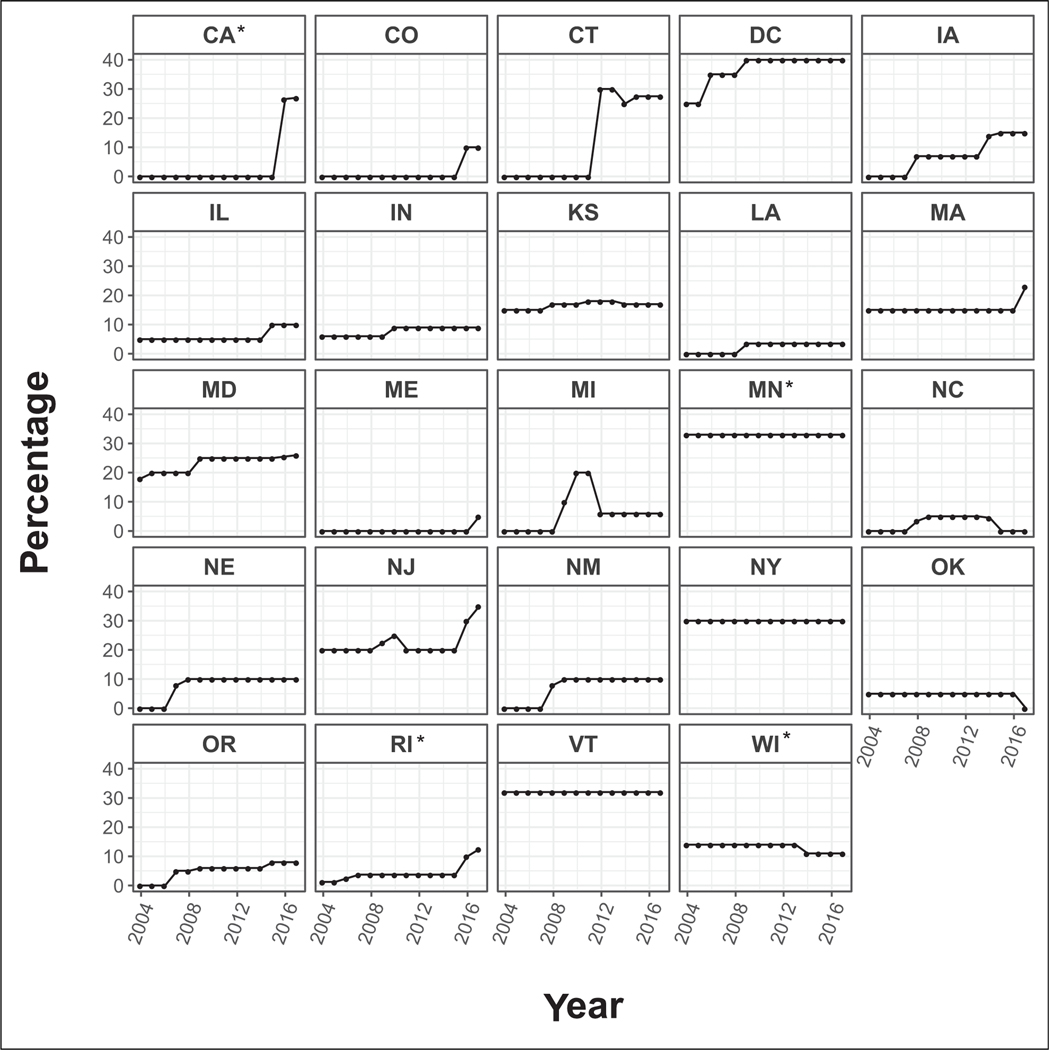

We assigned EITC measures according to the year in which taxpayers could have received EITC benefits. Historical information on state EITCs were obtained from the National Bureau of Economic Research’s TAXSIM program (www.nber.org/taxsim) (Feenberg & Coutts, 1993). The majority of state EITCs over the study period were fully refundable (i.e. tax filers could receive the credit in full, regardless of tax liability), but a small number of states offered a non-refundable EITC (i.e. tax filer’s credits were capped at the amount of their tax liability). We treated states with non-refundable EITCs as offering no EITC since most families living in poverty rarely owe sufficient income tax to benefit from non-refundable tax credits (Pac et al., 2020). Furthermore, prior studies found no association between non-refundable state EITCs and indicators of child maltreatment: rates of pediatric abusive head trauma and foster care entries (Klevens et al., 2016; Rostad et al., 2020). The vast majority of states set EITC benefits as a percentage of the federal benefit and followed the federal credit’s structure and eligibility criteria. However, four states (Wisconsin, Minnesota, Rhode Island, and California) offered an EITC that diverged from the typical state pattern. See Figure 1 Note for detailed information about our coding of the continuous EITC variable for these four states.

Figure 1.

State EITC generosity 2004–2017. Source: National Bureau of Economic Research’s TAXSIM program (www.nber.org/taxsim) Note. States not included in this figure never had a refundable EITC during the study period but were still included in the analysis. Data display the percentage of the federal EITC offered as a supplementary credit in each state and correspond to the year in which taxpayers received EITC benefits. Wisconsin’s EITC follows the federal structure but the percentage of the federal credit offered is based on number of children (e.g. one child: 4%; two children: 11%; or three children: 34%). For Wisconsin, we used the supplement for families with two children since an average family has approximately two children. Minnesota’s EITC depends on household income and ranges from 25% to 45%. For Minnesota, we used the average benefit according to the Tax Policy Center: 33% of the federal credit. Rhode Island offered a partially refundable EITC, for which we calculated the refundable portion as a percentage of the federal EITC. California’s EITC, which was first offered in tax year 2015, phased-out completely at 31% of the federal EITC’s earnings threshold. For California, we multiplied the percentage of the federal credit offered to eligible households by 31%.

In 2017, 26 states offered an EITC credit that supplemented the federal credit; 22 of which were fully refundable. Among the states that offered a refundable EITC in 2017, on average, states offered a credit equal to 18% of the federal credit. In 2017, state EITCs ranged in generosity from 3.5% in Louisiana to 40% in the District of Columbia. Figure 1 shows state-specific trends in the EITC variable used in our analyses between 2004 and 2017. Over the study period, the majority of state EITC changes involved newly enacted or expanded EITCs; only a few states changed from non-refundable to refundable or reduced the benefit level. Eleven states introduced a new refundable EITC and 16 states altered the generosity of an existing refundable EITC over the study period. On average, among states with a change in a refundable EITC, benefits increased by 9 percentage points, as a percentage of the federal EITC, between 2004 and 2017.

Covariates

Our models controlled for a set of state-level policies as well as demographic and economic characteristics that may be associated with both state EITC generosity and state-level rates of reported child maltreatment. We compiled the following variables at the state-year level: maximum Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) benefits for a family of three, state minimum wage (or the federal minimum wage if it exceeded the state’s minimum wage), whether the state expanded Medicaid under the ACA, whether the state offered Paid Family Leave, Gross State Product, the percentage of adults with a bachelor’s degree or higher, the percentage of children who are Black, and the percentage of children living in single-parent households. Online Appendix Figure 1 presents trends for each covariate among two groups: (1) states that offered a refundable EITC during the study period (n = 24) and (2) states that did not (n = 27). The two groups followed broadly similar covariate trends over the study period, but there were some notable differences; states that offered an EITC were more likely to introduce Paid Family Leave and expand Medicaid under the ACA. These trends suggest important differences in overall policy contexts between states with and without a supplementary EITC. Divergences over time in state policies also highlight the need to control for such state-by-year factors in our models to address confounding concerns.

Statistical Analyses

To examine the effect of state EITC policies on child maltreatment rates, we took a generalized difference-indifferences analytic approach (Wing et al., 2018), capturing EITC policy variation across states and within states over time and applying two-way fixed effects models to state-level data. We estimated ordinary least squares (OLS) regression models that controlled for state fixed-effects, year fixed-effects, state-specific linear and quadratic time trends, as well as the set of time-varying state-level policies and demographic and economic characteristics described above. The year and state fixed-effects controlled for temporal changes that occurred nationwide and time-invariant differences in state characteristics, respectively. State-specific time trends controlled for any gradual changes within states that may be correlated with both changes in the child maltreatment rate and state EITC policies. (See Online Appendix Note 1 for the formal model specification.)

The key assumption underlying this methodological approach is that states with and without a policy change would have followed parallel temporal trends in child maltreatment rates in the absence of a policy change. Counterfactual outcomes are inherently unobservable, but it is common to assess the validity of this assumption by examining trends prior to policy implementation (Wing et al., 2018). To quantitatively assess baseline trends in state-level maltreatment rates by EITC status, we estimated regression models for maltreatment report rates prior to the introduction of a refundable EITC that included an interaction term between continuous calendar year and an indicator for whether the state introduced a refundable EITC during the study period. Also, we carried out a falsification test with a “placebo” outcome that should not be affected by the EITC. Specially, we randomly assigned states’ maltreatment report rates over the study period.

We conducted several sensitivity analyses. First, we assessed whether our results were robust to the exclusion of 13 states that introduced the EITC before the start of the study period. If EITC benefits influenced child maltreatment trends in states that adopted the EITC before the study period, such states may no longer serve as suitable controls for later treatment states (Goodman-Bacon, 2018). We also tested whether our results were sensitive to the exclusion of reports made in California since California’s EITC—first offered in tax year 2015—differed in key structural ways from other state EITCs; most notably, by targeting a significantly smaller portion of the income distribution. For all analyses, standard errors were clustered at the state-level to account for the nonindependence of observations within the same state over time (Wing et al., 2018). Analyses were performed in the R statistical environment, using R version 3.6.0.

Results

Table 1 shows state-level maltreatment rates for states with and without refundable EITCs. During the study period, between 2004 and 2017, the average annual state rate of reported child maltreatment was 4,387 per 100,000 children and of substantiated child maltreatment was 854 per 100,000 children. Child maltreatment report rates were higher among 0–5-year old children than among 6–17-year old children (5,263 per 100,000 children ages 0–5 and 3,864 per 100,000 children ages 6–17).

Table 1.

Average State-level Maltreatment Rates by Presence of Refundable State EITC, 2004–2017 (n = 689 state years).

| States without an (n = 27) EITC |

States with an (n = 24) EITC |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

|

| |||||

| Overall reports per 100,000 children | |||||

| All children | 4,373 | 2,175 | 4,404 | 1,973 | |

| Children 0–5 years old | 5,215 | 2,578 | 5,318 | 2,051 | |

| Children 6–17 years old | 3,815 | 1,851 | 3,921 | 2,024 | |

| Neglect reports per 100,000 children | |||||

| All children | 2,449 | 1,472 | 2,835 | 1,465 | |

| Children 0–5 years old | 3,228 | 1,849 | 3,745 | 1,859 | |

| Children 6–17 years old | 1,990 | 1,239 | 2,370 | 1,326 | |

| Physical abuse reports per 100,000 children | |||||

| All children | 1,041 | 904 | 961 | 598 | |

| Children 0–5 years old | 1,112 | 1,191 | 987 | 695 | |

| Children 6–17 years old | 981 | 754 | 950 | 633 | |

| Emotional abuse reports per 100,000 children | |||||

| All children | 438 | 793 | 338 | 492 | |

| Children 0–5 years old | 473 | 998 | 393 | 619 | |

| Children 6–17 years old | 405 | 681 | 314 | 438 | |

| Sexual abuse reports per 100,000 children | |||||

| All children | 312 | 205 | 338 | 213 | |

| Children 0–5 years old | 253 | 174 | 284 | 176 | |

| Children 6–17 years old | 333 | 220 | 361 | 236 | |

| Overall substantiations per 100,000 children | |||||

| All children | 769 | 432 | 952 | 472 | |

| Children 0–5 years old | 1,078 | 605 | 1,318 | 643 | |

| Children 6–17 years old | 617 | 358 | 780 | 425 | |

Source: NCANDS Child File: 2004–2018

Note. SD = standard deviation. Because some maltreatment reports are not designated to any of the four maltreatment categories (neglect, physical abuse, emotional abuse, sexual abuse), the sum of reports made annually across the four types of maltreatment does not equal to the total number of reports made each year. States with a refundable EITC during the study period include: CA, CO, CT, DC, IA, IL, IN, KS, LA, MA, MD, ME, MI, MN, NC, NE, NJ, NM, NY, OK, OR, RI, VT, WI. States without a refundable EITC during the study period include: AK, AL, AR, AZ, DE, FL, GA, HI, ID, KY, MO, MS, MT, ND, NH, NV, OH, PA, SC, SD, TN, TX, UT, VA, WA, WV, WY

Tables 2 and 3 present key regression results for the association between state EITCs and annual rates of child maltreatment stratified by child age, maltreatment type, and substantiation status. We found that a 10-percentage point increase in the generosity of state EITC benefits was associated with 220 fewer overall reports of child maltreatment per 100,000 children (95% CI [−455, −15]) (Table 2). Coefficient estimates for covariates are provided in Online Appendix Table 2. To put these results into policy context, our estimates suggest that increasing all state EITCs to at least 18% of the federal credit (the average over the study period) would be associated with 177,444 fewer reports of maltreatment made nationwide in 2017, based on the approximately 3.5 million reports made that year (Online Appendix Table 3). Furthermore, we found that an increase in EITC generosity was associated with fewer reports of maltreatment both among children ages 0–5 (−276 per 100,000; 95% CI [−563, −9]) and children ages 6–17 (−194 per 100,000; 95% CI [−403, −16]) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Estimates of the Association between State EITC Generosity and Child Maltreatment Rates (2004–2017).

| Overall Reports | Neglect Reports | Physical Abuse Reports | Emotional Abuse Reports | Sexual Abuse Reports | Overall Substantiations | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| All Children | −220 (−455, 15)* | −241 (−449, −33)** | −21 (−58, 16) | −32 (−106, 42) | 6 (−16, 28) | −55 (−120, 10)* |

| By Child Age | ||||||

| Ages 0–5 | −276 (−563, 9)* | −324 (−582, −65)** | −22 (−69, 25) | −49 (−139, 41) | 6 (−21, 33) | −89 (−179, 1)* |

| Ages 6–17 | −194 (−403, 16)* | −201 (−387, −15)** | −19 (−50, 12) | −25 (−91, 42) | 5 (−15, 25) | −40 (−95, 15) |

| N | 689 | 689 | 689 | 658 | 689 | 689 |

Sources: NCANDS Child File: 2004–2018 and National Bureau of Economic Research’s TAXSIM program (www.nber.org/taxsim)

Note. All models include state and year fixed effects, state-specific linear and quadratic time trends, and the full set of state-level control variables for policies, economic characteristics, and demographics. 95% confidence intervals in parentheses. Each coefficient indicates changes in the rate of outcome associated with a 10 percentage point increase in a refundable state EITC, expressed as a percentage of the federal EITC.

p < .10;

p < .05

Table 3.

Estimates of the Association Between State EITC Presence and Child Maltreatment Rates (2004–2017)

| Overall Reports | Neglect Reports | Physical Abuse Reports | Emotional Abuse Reports | Sexual Abuse Reports | Overall Substantiations | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| All Children | −193 (−640, 254) | −407 (−851, 37)* | −60 (−152, 32) | −75 (−203, 52) | −11 (−53, 32) | −28 (−142, 86) |

| By Child Age Ages 0–5 | −299 (−871, 273) | −544 (−1111, 23)* | −60 (−180, 61) | −98 (−257, 62) | −14 (−57, 29) | −49 (−205, 106) |

| Ages 6–17 | −152 (−542, 238) | −347 (−736, 42)* | −62 (−146, 22) | −67 (−182, 47) | −10 (−52, 32) | −20 (−119, 78) |

| N | 689 | 689 | 689 | 658 | 689 | 689 |

Sources: NCANDS Child File: 2004–2018 and National Bureau of Economic Research’s TAXSIM program (www.nber.org/taxsim) Note. All models include state and year fixed effects, state-specific linear and quadratic time trends, and the full set of state-level control variables for policies, economic characteristics, and demographics 95% confidence intervals in parentheses. Each coefficient indicates changes in the rate of outcome associated with the introduction of a refundable state EITC.

p < .10;

p < .05.

We saw the strongest effects of EITC generosity on neglect: a 10-percentage point increase in the generosity of state EITC benefits led to 241 fewer overall reports of neglect per 100,000 children (95% CI [−449, −33]) (Table 2). An increase in EITC generosity was associated with fewer reports of neglect both among children ages 0–5 (−324 per 100,000; 95% CI [−582, −65]) and children ages 6–17 (−201 per 100,000; 95% CI [−387, −15]) (Table 2). We did not see similar strength of evidence for effects of the EITC on other types of maltreatment (physical abuse, emotional abuse, and sexual abuse), as none of these associations reached statistical significance.

When we tested the robustness of our results to only considering substantiated reports (rather than all reports, regardless of substantiation status), associations remained consistent between EITC generosity and both overall maltreatment rates (−55 per 100,000; 95% CI [−120, 10]) (Table 2). Finally, we considered whether simply the presence of a state EITC, without consideration for the generosity of the benefits offered, was associated with maltreatment reductions (Table 3). While a binary measure is less precise and does not capture the range of EITC benefits available to state taxpayers, we also observed that EITC presence was associated with 407 fewer reports of neglect per 100,000; 95% CI [−851, 37]) (Table 3). When testing the parallel trends assumption, we found no indication of a negative interaction between future EITC status and continuous calendar year on overall maltreatment reports (b = −6, P = .91) or reports of neglect (b = −75, P = .12), suggesting that the parallel trends assumption is plausible. Additionally, in a falsification test where we randomly assigned states’ neglect report rates over the study period, the association between the EITC and child maltreatment rates switched signs (positive, rather than negative; b = 184; results not shown). Our results were also largely unchanged by a set of sensitivity tests in which we excluded states that introduced the EITC before the start of the study period (Online Appendix Table 4), and California (Online Appendix Table 5).

Discussion

We assessed the association between state EITC policies and child maltreatment using an administrative dataset on all official reports of child maltreatment made across the United States from 2004 to 2017. We found evidence that the presence of a refundable state EITC predicted lower rates of reported neglect, but not other types of maltreatment. The generosity of refundable state EITC programs was associated with fewer reports of child maltreatment: a 10-percentage point increase in a refundable state EITC benefit led to a 5% decline in rates of reported child maltreatment. The association between state EITC generosity and overall rates of child maltreatment was driven primarily by neglect rates. A 10-percentage point increase in a refundable state EITC benefit led to an 9% decline in rates of reported neglect, a substantively significant policy and public health effect. The magnitude of these results aligned with those of two previous studies which found that the introduction of a refundable state EITC was associated with an 11% decrease in foster care entries (Rostad et al., 2020) and a 13% reduction in hospital admissions for pediatric abusive head trauma (Klevens et al., 2016). We did not find a significant association between refundable state EITC policies and other types of maltreatment (physical abuse, emotional abuse, and sexual abuse).

Although neglect receives disproportionally less pubic attention than physical abuse and sexual abuse, it makes up approximately 75% of all confirmed child maltreatment cases and is linked to severe health and developmental impairments (National Scientific Council on the Developing Child, 2012). Of the 1,720 child fatalities attributed to maltreatment in 2017, neglect was present in 75% of the cases (Child Maltreatment 2017). Over recent decades, rates of neglect have remained persistently high, while rates of physical and sexual abuse have declined (Finkelhor et al., 2018). Traditional child welfare interventions, which occur at the family-level and seek to alter perpetrator behavior, may be less effective for preventing neglect than other forms of abuse (Bullinger et al., 2019). Given the complex relationship between poverty and neglect, macro-level social policies that address families economic circumstances could hold more promise for neglect prevention (Bullinger et al., 2019).

Our results indicate that the EITC may reduce rates of maltreatment for both young and older children. Effects were largest on rates of neglect among young children (ages 0–5), the population with the highest baseline rates of neglect. Decreases among children 5 years or younger are meaningful since early childhood is a particularly crucial time for children’s development, when the basis for lifelong physical, cognitive, social, and emotional health is formed (e.g. Shonkoff & Phillips, 2000; Heckman, 2006). Lower rates of maltreatment among younger children suggest that the EITC has value as a primary prevention strategy, potentially thwarting the initiation of maltreatment in the earliest stages of childhood.

This study had limitations. First, our analyses were based on state-wide aggregate measures. Therefore, we cannot study potential mechanisms by which the EITC influences maltreatment risk. Second, reports of maltreatment made to child welfare agencies reflect a conservative estimate of the true magnitude of child maltreatment (Kim et al., 2017). Despite this limitation, researchers consider official child maltreatment reports among the best available indicators of maltreatment risk that track important public health trends such as infant mortality and infant homicides (Drake et al., 2011). Third, the number of screened-in reports of child maltreatment may be influenced by changes in agency budgets and policies. Such changes would have biased our results if they were correlated with the timing of changes in state EITCs. Although not yet available at the time of this study, a nationwide database of state-level child welfare policies, such as reported screen-in procedures and overall spending within each state’s system, would benefit future studies. Fourth, caution should be exercised when interpreting results stratified by maltreatment type, given jurisdictional discretion in classification of maltreatment. Finally, the internal validity of our results could be biased by any unobserved shocks that occurred either during or after EITC changes that did not equally affect states by EITC status.

Despite these limitations, our findings suggest the important possibility that economic support policies for low-income families play a role in the family conditions that perpetuate child maltreatment. Broad-based social policies, such as the EITC, may be effective strategies for the primary prevention of child maltreatment in the population. There is growing recognition that the child welfare system has limited ability to address many of the complex and interwoven factors that lead to maltreatment (Herrenkohl et al., 2016). By design, the child welfare system is largely reactive, only intervening with tertiary prevention after maltreatment has occurred. Decisionmakers and stakeholders should consider interventions that strengthen family economic stability in the broader effort to lessen family stress and prevent child maltreatment. Income support policies such as the EITC that reach families regardless of, and hopefully before, any involvement in the child welfare system, may be effective prevention strategies for a large proportion of the population.

This study adds to a growing body of evidence linking the EITC to positive spillover effects on child health and wellbeing, as well as preliminary evidence that the EITC meaningfully reduces maltreatment rates. Future work is needed to understand the specific dimensions of child neglect that the EITC addresses, given that neglect is a broad classification for many unmet child needs.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding

The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was funded by a cooperative agreement with the Centers for Disease Control & Prevention (1U01CE002945). Partial support for this research came from a Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development research infrastructure grant, P2C HD042828, to the Center for Studies in Demography & Ecology at the University of Washington.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- Arno PS, Sohler N, Viola D, & Schechter C. (2009). Bringing health and social policy together: The case of the earned income tax credit. Journal of Public Health Policy, 30(2), 198–207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Averett S, & Wang Y. (2018). Effects of higher EITC payments on children’s health, quality of home environment, and noncognitive skills. Public Finance Review, 46(4), 519–557. [Google Scholar]

- Berger LM (2004). Income, family structure, and child maltreatment risk. Children and Youth Services Review, 26(8), 725–748. [Google Scholar]

- Berger LM, Font SA, Slack KS, & Waldfogel J. (2017). Income and child maltreatment in unmarried families: Evidence from the earned income tax credit. Review of Economics of the Household, 15(4), 1345–1372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger LM, & Waldfogel J. (2011). Economic determinants and consequences of child maltreatment. OECD. [Google Scholar]

- Boyd-Swan C, Herbst CM, Ifcher J, & Zarghamee H. (2016). The earned income tax credit, mental health, and happiness. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 126, 18–38. [Google Scholar]

- Braveman P, & Barclay C. (2009). Health disparities beginning in childhood: A life-course perspective. Pediatrics, 124(Supplement 3), S163–S175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown EC, Garrison MM, Bao H, Qu P, Jenny C, & RowhaniRahbar A. (2019). Assessment of rates of child maltreatment in states with Medicaid expansion vs states without Medicaid expansion. JAMA Network Open, 2(6)e195529–e195529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bullinger LR, Feely M, Raissian KM, & Schneider W. (2019). Heed neglect, disrupt child maltreatment: A call to action for researchers. International Journal on Child Maltreatment: Research, Policy and Practice, 1–12.32954215 [Google Scholar]

- Drake B, Jolley JM, Lanier P, Fluke J, Barth RP, & JonsonReid M. (2011). Racial bias in child protection? A comparison of competing explanations using national data. Pediatrics, 127(3), 471–478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eissa N, & Hoynes HW (2006). Behavioral responses to taxes: Lessons from the EITC and labor supply. Tax Policy and the Economy, 20, 73–110. [Google Scholar]

- Evans WN, & Garthwaite CL (2014). Giving mom a break: The impact of higher EITC payments on maternal health. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 6(2), 258–90. [Google Scholar]

- Feenberg D, & Coutts E. (1993). An introduction to the TAXSIM model. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 12(1), 189–194. [Google Scholar]

- Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, Williamson DF, Spitz AM, Edwards V, & Marks JS (1998). Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 14(4), 245–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D, Saito K, & Jones L. (2018). Updated trends in child maltreatment 2016. Crimes against Children Research Center. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman-Bacon A. (2018). Difference-in-differences with variation in treatment timing (No. w25018). National Bureau of Economic Research. [Google Scholar]

- Halpern-Meekin S, Edin K, Tach L, & Sykes J. (2015). It’s not like I’m poor: How working families make ends meet in a postwelfare world. Univ of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Heckman JJ (2006). Skill formation and the economics of investing in disadvantaged children. Science, 312(5782), 1900–1902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrenkohl TI, Leeb RT, & Higgins D. (2016). The public health model of child maltreatment prevention. Trauma Violence Abuse, 17(4), 363–365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoynes H, Miller D, & Simon D. (2015). Income, the earned income tax credit, and infant health. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 7(1), 172–211. [Google Scholar]

- Hoynes HW, & Patel AJ (2018). Effective policy for reducing poverty and inequality? The earned income tax credit and the distribution of income. Journal of Human Resources, 53(4), 859–890. [Google Scholar]

- Hussey JM, Chang JJ, & Kotch JB (2006). Child maltreatment in the United States: Prevalence, risk factors, and adolescent health consequences. Pediatrics, 118(3), 933–942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussey JM, Marshall JM, English DJ, Knight ED, Lau AS, Dubowitz H, & Kotch JB (2005). Defining maltreatment according to substantiation: Distinction without a difference? Child Abuse & Neglect, 29(5), 479–492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonson-Reid M, Drake B, & Zhou P. (2013). Neglect subtypes, race, and poverty: Individual, family, and service characteristics. Child Maltreatment, 18(1), 30–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H, Wildeman C, Jonson-Reid M, & Drake B. (2017). Lifetime prevalence of investigating child maltreatment among US children. American Journal of Public Health, 107(2), 274–280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klevens J, Barnett SBL, Florence C, & Moore D. (2015). Exploring policies for the reduction of child physical abuse and neglect. Child Abuse & Neglect, 40, 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klevens J, Luo F, Xu L, Peterson C, & Latzman NE (2016). Paid family leave’s effect on hospital admissions for pediatric abusive head trauma. Injury Prevention, 22(6), 442–445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohl PL, Jonson-Reid M, & Drake B. (2009). Time to leave substantiation behind: Findings from a national probability study. Child Maltreatment, 14(1), 17–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kugler KC, Guastaferro K, Shenk CE, Beal SJ, Zadzora KM, & Noll JG (2019). The effect of substantiated and unsubstantiated investigations of child maltreatment and subsequent adolescent health. Child Abuse & Neglect, 87, 112–119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenhart O. (2019). The effects of income on health: new evidence from the Earned Income Tax Credit. Review of Economics of the Household, 17(2), 377–410. [Google Scholar]

- National Scientific Council on the Developing Child (2012). The science of neglect: The persistent absence of responsive care disrupts the developing Brain. (Working Paper No. 12) www.developingchild.harvard.edu.

- Pac J, Garfinkel I, Kaushal N, Nam J, Nolan L, Waldfogel J, & Wimer C. (2020). Reducing poverty among children: Evidence from state policy simulations. Children and Youth Services Review, 105030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxson C, & Waldfogel J. (2003). Welfare reforms, family resources, and child maltreatment. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 22(1), 85–113. [Google Scholar]

- Pelton LH (2015). The continuing role of material factors in child maltreatment and placement. Child Abuse & Neglect, 41, 30–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson C, Florence C, & Klevens J. (2018). The economic burden of child maltreatment in the United States, 2015. Child Abuse & Neglect, 86, 178–183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raissian KM, & Bullinger LR (2017). Money matters: Does the minimum wage affect child maltreatment rates? Children and Youth Services Review, 72, 60–70. [Google Scholar]

- Rostad WL, Ports KA, Tang S, & Klevens J. (2020). Reducing the number of children entering foster care: effects of state Earned Income Tax Credits. Child Maltreatment, 25(4), 1077559519900922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sedlak AJ, Mettenburg J, Basena M, Peta I, McPherson K, & Greene A. (2010). Fourth national incidence study of child abuse and neglect (NIS-4) (Vol. 9). US Department of Health and Human Services. [Google Scholar]

- Shonkoff J & Phillips DA (Eds.). (2000). From neurons to neighborhoods: The science of early childhood development. National Academies Press. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon D, McInerney M, & Goodell S. (2018). The earned income tax credit, poverty, and health. Health Affairs Policy Brief. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hpb20180817.769687/full/ [Google Scholar]

- Springer KW, Sheridan J, Kuo D, & Carnes M. (2007). Long-term physical and mental health consequences of childhood physical abuse: results from a large population-based sample of men and women. Child Abuse & Neglect, 31(5), 517–530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Administration on Children, Youth and Families, Children’s Bureau. Child maltreatment (2017). https://www.acf.hhs.gov/cb/resource/child-maltreatment-2017

- Walsh C, MacMillan HL, & Jamieson E. (2003). The relationship between parental substance abuse and child maltreatment: findings from the Ontario Health Supplement. Child Abuse & Neglect, 27(12), 1409–1425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wing C, Simon K, & Bello-Gomez RA (2018). Designing difference in difference studies: Best practices for public health policy research. Annual Review of Public Health, 39, 453–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.