Abstract

Purpose

We aimed to explore differences in the NaIO3-elicited responses of retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) and other retinal cells associated with mouse strains and dosing regimens.

Methods

One dose of NaIO3 at 10 or 15 mg/kg was given intravenously to adult male C57BL/6J and 129/SV-E mice. Control animals were injected with PBS. Morphologic and functional changes were characterized by spectral domain optical coherence tomography, electroretinography, histologic, and immunofluorescence techniques.

Results

Injection with 10 mg/kg of NaIO3 did not cause consistent RPE or retinal changes in either strain. Administration of 15 mg/kg of NaIO3 initially induced a large transient increase in scotopic electroretinography a-, b-, and c-wave amplitudes within 12 hours of injection, followed by progressive structural and functional degradation at 3 days after injection in C57BL/6J mice and at 1 week after injection in 129/SV-E mice. RPE cell loss occurred in a large posterior-central lesion with a ring-like transition zone of abnormally shaped cells starting 12 hours after NaIO3 treatment.

Conclusions

NaIO3 effects depended on the timing, dosage, and mouse strain. The RPE in the periphery was spared from damage compared with the central RPE. The large transient increase in the electroretinography was remarkable.

Translational Relevance

This study is a phase T1 translational research study focusing on the development and validation of a mouse model of RPE damage. It provides a detailed foundation for future research, informing choices of mouse strain, dosage, and time points to establish NaIO3-induced RPE damage.

Keywords: sodium iodate, strain difference, retinal pigment epithelium, age-related degeneration

Introduction

The retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) layer is a monolayer epithelium just outside of the neural retina that functions as the major barrier between the outer retina and the choroid. The RPE plays a critical role in the survival of photoreceptor cells and in the normal function of the blood–retinal barrier.1 Dysfunction of RPE cells can cause retinal disease, such as age-related macular degeneration (AMD)2 and, therefore, it is the subject of intense research. There are several animal models of AMD. Some acute experimental models of RPE damage and retinal damage are appropriate for specific aspects of human macular diseases,3 even those that progress slowly or appear late in life, including AMD. To further develop and refine an AMD animal model for needed therapeutics, we sought to optimize a mouse model based on the known RPE-specific toxicity of systemic NaIO3 treatment. Here, the proposition is that, although NaIO3 treatment damages the RPE, and therefore, it is a model of RPE disease, it is underdeveloped because its mechanism remains unknown; thus, the field needs a vetting of the model under more nuanced circumstances.

NaIO3, a stable chemical oxidizing agent,4 induces RPE damage, mimicking some features of geographic atrophy (GA).5–7 As summarized and extended by Sorsby in 1941,8 systemically administered NaIO3 is selectively toxic to RPE cells, and this RPE damage is followed by retinal degeneration in humans and rabbits. This finding has been tested in several mammals, such as mice, rats, monkeys, rabbits, dogs, and pigs.6,9–13 The effect of NaIO3 on the RPE and retina is time and dose dependent, with the structure and function of the retina deteriorating steadily by the week.14–18 The damage is possibly reversible at low concentrations, but permanent at modestly higher concentrations.16

The damage mechanism of NaIO3 on the RPE is still not completely understood. NaIO3 treatment induces oxidative stress and upregulates the genes involved in oxidative stress responses, resulting in the death of the RPE cells in vivo and in vitro10,19,20 and the accumulation of macrophages near RPE cells, causing photoreceptor cell death.16 The inhibition of oxidative stress could be a treatment target to alleviate RPE cell dysfunction and apoptosis.21,22 RPE cell necrosis followed by photoreceptor cell apoptosis occurs after high-dose administration of NaIO3,23 whereas a lower dose induces RPE cell apoptosis via calpain-mediated pathways.24,25

We compare C57BL/6J and 129/SV mice, two common strains used for NaIO3-induced RPE damage. Functional and in vivo morphometric comparisons have been conducted in these two strains. Comparisons among previous studies are difficult because NaIO3 dosage and administration, types of outcome measures, and time points after injection vary widely among groups and publications. Unlike some previously published efforts, we rigorously genotyped mice to confirm strain identity. Moreover, we investigated the functional and morphologic responses of C57BL/6J and 129/SV-E mice to systemic low doses of NaIO3 at times shortly after systemic treatment with NaIO3. In particular, we thoroughly characterized the electroretinography (ERG) responses after NaIO3 treatment, which few investigations have reported previously.

To refine the NaIO3-induced RPE damage model that exhibits repeatable, moderate functional, and structural changes, we explored the difference in response of the RPE and retina to a mouse strain and dosing regimen. We provide a detailed reference for future studies in choosing mouse strains, dosages, and time points to establish the NaIO3-induced RPE damage model.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Young adult male 2- to 3-month old C57BL/6J (Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) and 129/SV-E (Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA) mice were used in this study. The consensus is that males are more susceptible than females to NaIO3. Schnabolk et al.26 reported that disease severity differences after NaIO3 treatment were observed between the sexes. We chose only males to decrease and control variability. In future experiments, we plan to directly compare male and female responses to NaIO3, now that we have been able to decrease the dose, increase the reliability of the effects, find the earliest time points, and perhaps detect the initiation of disease caused by NaIO3 in one sex. All animals were housed in a standard laboratory environment and maintained on a 12-hour:12-hour light–dark cycle (7 am on and 7 pm off) at 21 °C. During the light cycle, the light levels measured at the bottom of the mouse cages ranged from 5 to 45 lux. Mice had access to standard mouse chow (Rodent Diet 5053; LabDiet, Inc., St. Louis, MO) ad libitum and weighed 25 to 30 g throughout the study. All mouse handling procedures and care were approved by the Emory Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and followed the ARVO Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research. Mice were euthanized with CO2 gas for all experiments.

NaIO3 Preparation and Tail Vein Injection

A sterile 0.3% (W/V) NaIO3 solution was freshly prepared from solid NaIO3 (MKCB2618V, Sigma-Aldrich, assay ≥99%) dissolved in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (VWRVK813, Cat. #97063-660, 1× solution composition: 137 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 9.5 mM phosphate buffer) before tail vein injection. Each mouse received a single tail vein injection. Mice were injected with 10 or 15 mg/kg of body weight of 0.3% NaIO3 solution. Control mice were injected with an equivalent volume of sterile PBS based on body weight.

Each mouse was anesthetized with isoflurane/oxygen (isoflurane, NDC 66794-017-25, Piramal Critical Care Inc., Bethlehem, PA) and placed on a circulating heating water pad (39 °C) to keep warm during anesthesia. An overhead lamp was used to provide an additional light source to visualize the tail vein. Positioning the animal on its side, we grasped the tail at midlength and injected the lateral vein using a 30 g needle and a 0.3-mL syringe (Cat. #50752, MHC Medical Products), keeping the needle parallel to the vein. An alcohol preparation pad was used before injection to disinfect, promote vasodilation, and stop bleeding after injection.

Several delivery methods of NaIO3 have been used in recent studies, including intravenous, intraperitoneal, and intravitreal routes. The reason we chose intravenous injection to deliver NaIO3 was that our preliminary experiments revealed that intraperitoneal injection with NaIO3 induced retinal degeneration, but with large variations within treated groups. Other routes, including retro-orbital or intravitreal injection, involve high rates of technical failure in our experience. Once the tail vein injections were mastered, we found the injections to be fast, reliable, and less traumatic for the mouse.

ERG

Mice were dark adapted overnight before ERG was performed. In preparation for the ERG, the mice were anesthetized using intraperitoneal injections of 100 mg/kg of ketamine and 15 mg/kg of xylazine (ketamine; KetaVed from Vedco, Inc., Saint Joseph, MO; xylazine from Akorn, Lake Forest, IL).

Once anesthetized, proparacaine (1%; Akorn Inc.) and tropicamide (1%; Akorn Inc.) eye drops were administered to decrease eye sensitivity and dilate the pupils. Mice were placed on a heating pad (39 °C) under dim red light provided by the overhead lamp of the Diagnosys Celeris system (Diagnosys, LLC, Lowell, MA). Light-guided electrodes were placed in contact with individual eyes; the corneal electrode for the contralateral eye acted as the reference electrode. Full-field ERGs were recorded for the scotopic condition (stimulus intensity: 0.001, 0.005, 0.01, 0.1, 1, and 10 cd s/m2; flash duration, 4 ms). Signals were collected for 0.3 seconds in steps 1 to 5 and 5 seconds for step 6 after light flashes. Scotopic a-, b-, and c-waves were defined, as noted in Figure 3. After the recordings, each mouse was placed in its home cage on top of a heating pad (39 °C) to recover from anesthesia.

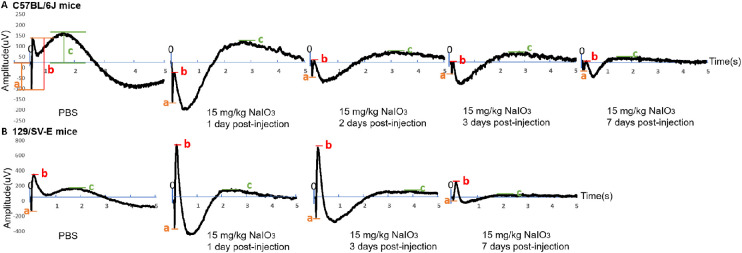

Figure 3.

Effects of 15 mg/kg of NaIO3 on the waveforms of scotopic electroretinogram (ERG; stimulus intensity: 10 cd.s/m2, flash duration: 4 ms, recording time: 5 s) in C57BL/6J and 129/SV-E mice. Here, “0” represents the start of stimulation, “a” represents the amplitude of scotopic a-wave, “b” represents the amplitude of scotopic b-wave, and “c” represents the amplitude of scotopic c-wave. (A) Daily changes in the waveforms after 15 mg/kg of NaIO3 administration over 7 days in C57BL/6J mice. (B) The amplitudes of scotopic a- and b-wave both increased at 1 day after injection but decreased at 7 days after 15 mg/kg NaIO3 injection in 129/SV-E mice compared with PBS-treated mice.

In Vivo Ocular Imaging

Spectral domain optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT) was conducted immediately after the ERG measurement, while the mouse was still anesthetized and the pupils still dilated. A Micron IV SD-OCT system with fundus camera (Phoenix Research Labs, Pleasanton, CA) and a Heidelberg Spectralis cSLO and SD-OCT instrument with a 25 D lens (HRAOCT2-MC; Heidelberg Engineering, Heidelberg, Germany) were used in tandem sequentially to assess the ocular posterior segment morphology in cross-section and en face. Using the Micron IV system, image-guided OCT images were obtained for the left and right eyes after a sharp and clear image of the fundus (with the optic nerve centered) was obtained. Circular scans approximately 100 µm from the optic nerve head (ONH) were collected, and 50 scans were averaged together. The retinal layers were identified according to published nomenclature.27 The neural retinal thickness and thickness of the outer nuclear layer (ONL) were analyzed using Photoshop CS6 (Adobe Systems Inc., San Jose, CA). Pixels were converted into micrometers using a conversion factor of 1.3 µm = 1 pixel. Immediately after imaging on the Micron IV system, a rigid contact lens (Heidelberg Engineering) was placed on the eye (back optic zone radius, 1.7 mm; diameter, 3.2 mm; power, Plano), and blue autofluorescence (BAF) imaging at the layer of the photoreceptor–RPE interface was conducted using a Heidelberg Spectralis cSLO instrument. During imaging and anesthesia recovery, the mice were kept on water-circulating heating pads at 39 °C to maintain body temperature.

Histology and Morphometrics of Ocular Sections

Histologic and morphometric procedures followed standard techniques. Left eyes were collected for sectioning, and right eyes were collected for RPE flatmounts. Left eyes were fixed in fixation solution (97% methanol, VWR, Cat. #BDH20291GLP; 3% acetic acid, Cat. #Fisher BP2401-500) at −80 °C for 4 days, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned through the sagittal plane on a microtome at thickness of 5 µm, with minor variation of the freeze-substitution method of Mary-Sinclair et al.28 Sections were used for hematoxylin and eosin staining, as described previously.29 All sections were imaged with a bright-field microscope with a 20× objective.

ONL nuclei were counted in a semiautomated fashion using QuPath (University of Edinburgh, Division of Pathology, Edinburgh, Scotland; https://qupath.github.io/)30 to outline the regions of the nuclei and then identify and count them within 100-µm-wide segments. The entire retina was divided into parts radially from the ONH, with five parts in the superior direction and five parts in the inferior direction. Nuclei counts were done inside a 100 µm box centered in each of the 10 parts. The first 100 µm box on each side of the ONH was placed 250 µm from the ONH. This resulted in ONL nuclei counts in ten 100 µm regions of the retina for each mouse. Mean ONL counts from three to five mice per group were plotted as “spidergrams.”

Immunofluorescence and Imaging of Retinal Sections

Immunofluorescence was used to detect glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP; anti-GFAP, #Z0334, Dako) to assess Müller cell reactivity. First, 5-µm paraffin sections were deparaffinized and rehydrated, as previously described.31 Blocking buffer consisted of 0.1% (V/V) Tween-20 and 5% (V/V) donkey serum (#S1003-36 lot 16090957, US Biological) in 1× Tris-buffered saline (TBS, 46-012-CM, Corning, 1X solution composition: 20 mM Tris, 136 mM NaCl, pH approximately 7.4). Slides were incubated in blocking solution in a Coplin jar for 30 minutes and transferred to a humidified chamber. Primary antibody solution (anti-GFAP, 1:500 diluted in blocking buffer; 200 µL) was placed on the slide, covered with a plastic Rinzl coverslip to evenly spread the antibody over the section and decrease evaporation, and incubated overnight at 4 °C. The next day, the coverslip was removed, and the slides were washed three times in 1× TBS for 15 minutes each. Secondary antibody solution (Donkey Anti-Rabbit IgG AF568, #A10042, Life Technologies, 1:1,000 diluted in blocking buffer; 200 µL) was added and incubated for 2 hours in a humidified chamber with 1× TBS at 22 °C. Slides were washed three times in 1× TBS for 15 minutes each and placed in fresh Coplin jars with 1× TBS. Finally, one to three drops of 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole nuclear stain plus Fluorshield (#F6057; Sigma, St. Louis, MO) were applied to each immunofluorescence slide. A coverslip (#22; #152250; Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA) was placed on top of the slide. The mounting media solidified overnight in darkness at ambient room temperature (22 °C) before imaging. GFAP quantification was achieved by counting GFAP-positive fibers fully penetrating into the inner nuclear layer, as others have reported.32 The data are presented as the mean ± standard error of the mean.

RPE Flatmounts

The flatmounts were prepared using the same microdissection technique as we reported previously.33,34 Briefly, the superior side of the eye was marked with a fine-point, permanent ink pen (Sharpie, Oak Brook, IL). The eye was removed, fixed in Z-Fix (Anatech Ltd., Battle Creek, MI) for 10 minutes, and then washed three times with PBS. Excess tissue was removed from the outside of the globe under a dissecting microscope. The center of the cornea was punctured using 3-mm iridectomy scissors, and flatmounting was conducted by making four radial cuts from the center of the cornea back toward the optic nerve. The flaps were peeled away from the lens, and the lens was removed. The iris and retina were removed using forceps. Four additional cuts were made in each of the four RPE–scleral flaps to enable the tissue to be flattened with the RPE side up on conventional microscope slides to which a silicon gasket had been applied (Grace Bio-Labs, Bend, OR). The RPE flatmounts were blocked with Hanks’ balanced salt solution (#SH30588.01; Hyclone, Logan, UT) containing 0.3% (V/V) Triton X-100 and 1% (W/V) bovine serum albumin (blocking buffer) for 1 hour at 22 °C.

Immunofluorescence and Confocal Imaging of RPE Flatmounts

RPE flatmounts were immunostained with a dilution of 1:250 anti-Zonula occludens-1 (ZO-1, Cat. #MABT11, Sigma) and 1:500 anti-CTNNA1 (Cat. #EP1793Y, Abcam, Cambridge, MA) in blocking buffer overnight at 4 °C. The flatmounts were washed five times with Hanks’ balanced salt solution plus 0.3% (v/v) Triton X-100 (wash buffer) for 2 minutes and then stained with secondary antibodies (Alexa Fluor 488,1:1,000 donkey anti-rat IgG, Cat. # A21208, Thermo Fisher Scientific; Alexa Fluor 568, 1:1,000 goat anti-rabbit IgG, Cat. #A11036, Thermo Fisher Scientific) by incubation for 2 hours at 22 °C. The flatmounts were washed with Hoechst 33258 (1:250, Cat. #H3569, Thermo Fisher Scientific) in blocking buffer three times to stain nuclei; they were then washed twice with wash buffer. The flatmounts were mounted with two drops of Fluoromount-G (Cat. #17984–25, Electron Microscopy Sciences, Signal Hill, CA), coverslipped, and allowed to harden overnight. The slides were stored in the dark at 4 °C until imaging using a Nikon Ti inverted microscope with a C1 confocal scanner (Nikon Instruments Inc., Melville, NY). Using automated XY stage control within the EZ-C1 software, the flatmounts were imaged with a 10X objective lens. Images were processed as described previously.33 Confocal images were digitally merged (Adobe Photoshop CS2; Adobe Systems Inc.).

Statistical Analyses

One- and two-way repeated-measure analyses of variance with Sidak/Tukey post hoc analysis and Student t tests were performed for the ERG and morphometric data. For all analyses, a P value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All graphs display data as the mean ± standard error of the mean. The stated n is the number of animals used in each group. Graphs and analyses were conducted using Prism 8.2.1 Software (GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA).

Results

Functional Changes After Low Dose NaIO3 Administration

To investigate visual functional changes after NaIO3 administration, we performed ERGs for all groups (NaIO3 treated and untreated; both mouse strains). Scotopic a-, b-, and c-waves were recorded across a series of increasing flash intensities.

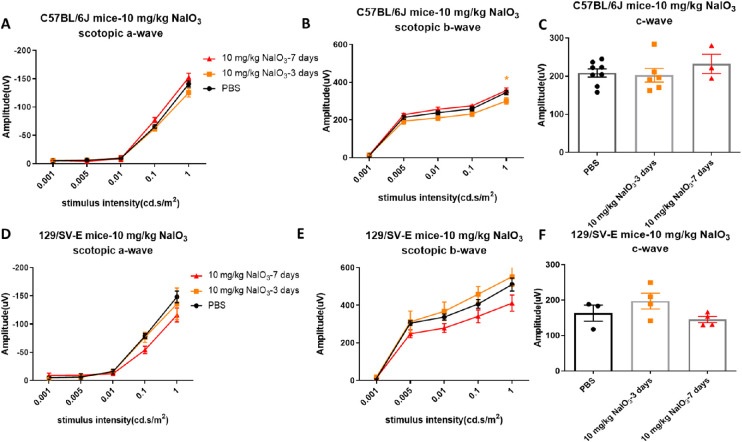

Single injections of 10 mg/kg of NaIO3 did not cause obvious damage to retinal function based on scotopic ERG assessment at 3 and 7 days after NaIO3 administration in the 129/SV-E mice (Figs. 1D, E, F). In C57BL/6J mice, amplitudes of scotopic a- and b-waves decreased slightly at a stimulus intensity level of 1 cd.s/m2 3 days after administration, but such functional loss disappeared 4 days later (Figs. 1A, B). The scotopic c-wave amplitude, which in part reflects RPE function, did not change in either strain within a week after NaIO3 treatment (Figs. 1C, F).

Figure 1.

Doses of 10 mg/kg of NaIO3 did not induce consistent visual function loss in C57BL/6J and 129/SV-E mice. (A, B, C) Scotopic electroretinogram (ERG) amplitudes at 3 and 7 days after injection in C57BL/6J mice. (D, E, F) Mean amplitudes of scotopic ERG at 3 and 7 days after injection in 129/SV-E mice. The results are presented as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). A two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey's multiple comparisons test was conducted between the mean amplitudes in all pair combinations. *P < 0.05. n = 3–8 C57BL/6J mice per group and n = 3–4 129/SV-E mice per group.

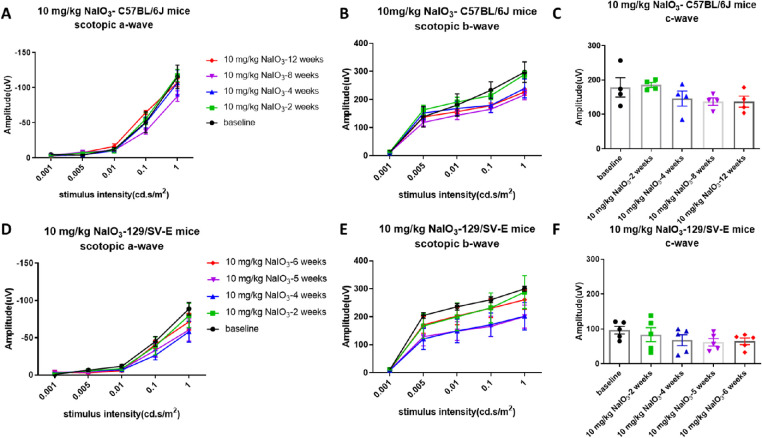

To discover whether 10 mg/kg of NaIO3 has chronic toxic effects on visual function, ERGs were recorded after administration weekly for 12 weeks. Although there was a trend toward decreased ERG amplitudes with the 10 mg/kg dose, the differences were not significant and were not consistent over time, which indicated that intravenous injection of 10 mg/kg of NaIO3 did not induce consistent damage to the RPE or retinal function in these two strains (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Longitudinal analysis of visual function of C57BL/6J and 129/SV-E mice treated with a low dose of NaIO3. Scotopic a-, b-, and c-wave amplitudes did not show significant changes in any stimulus intensity through 12 weeks in C57BL/6J mice (A, B, C) and 6 weeks in 129/SV-E mice (D, E, F) after the administration of 10 mg/kg of NaIO3. The results are presented as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). A one/two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey's multiple comparisons test was conducted among the mean amplitudes in all pair combinations. n = 4 C57BL/6J mice per group and n = 5 129/SV-E mice per group.

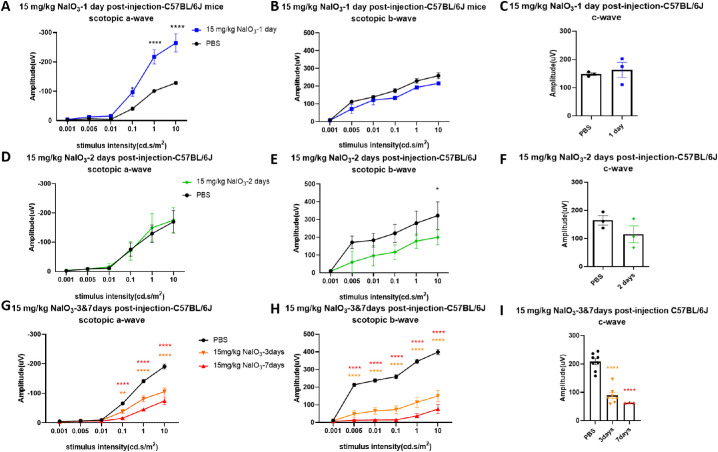

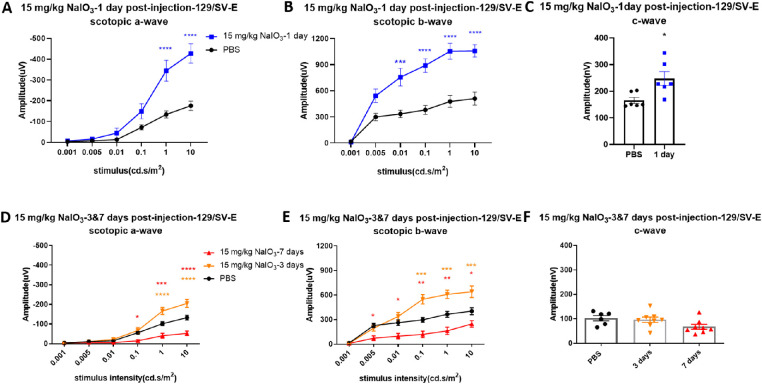

Different from the 10 mg/kg dose, a 15 mg/kg dose of NaIO3 caused severe damage. ERG responses showed dramatic changes 1 day after injection with 15 mg/kg of NaIO3 in both strains. Overall waveforms of scotopic ERG in step 6 (stimulus intensity: 10 cd.s/m2, recording time: 5 seconds) represented a deeper trough of the a-wave and a lower b-wave (Fig. 3). Importantly, the scotopic a-wave amplitude at day 1 after NaIO3 injection in C57BL/6J mice (Fig. 4A) was significantly increased compared with that in untreated mice. The c-wave amplitude did not show significant changes compared with the PBS-treated group at 1 day after NaIO3 injection (Fig. 4C). Scotopic a- and b-wave amplitudes were both significantly increased at days 1 and 3 after NaIO3 injection in 129/SV-E mice (Figs. 5A, B, D, E). The mean c-wave amplitude in 129/SV-E was also elevated at day 1 after NaIO3 treatment (Fig. 5C). Thereafter, the amplitudes of a-, b-, and c-waves of NaIO3-treated mice were all significantly decreased compared with those of PBS-treated mice.

Figure 4.

Visual function was gradually decreased after the administration of 15 mg/kg of NaIO3 in C57BL/6J mice. (A, B) Scotopic a-wave amplitude increased (doubling in amplitude) at 0.1 and 1 cd s/m2 at 1 day after injection with 15 mg/kg of NaIO3, while the scotopic b-wave amplitude was slightly decreased compared with PBS treatment. (D, E) Mean amplitudes of scotopic a- and b-wave 2 days after NaIO3 treatment. (G, H) Significant decreased of ERG a- and b-wave responses was observed 3 days and 7 days after injection with 15 mg/kg of NaIO3 in C57BL/6J mice compared with the PBS group. (C, F, I) Amplitudes of scotopic c-wave decreased over time after NaIO3 treatment compared with the PBS group. The results are presented as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). A two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Sidak's multiple comparisons test was conducted between the mean amplitudes in all pair combinations. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001. n = 3 mice (1, 2 and 7 days after injection), n = 7 mice (3 days after injection, NaIO3-treated mouse group), n = 8 mice (3 days after injection, PBS group).

Figure 5.

Changes in scotopic a-, b-, and c-wave amplitudes following 15 mg/kg of NaIO3 administration in 129/SV-E mice. (A, B, C) Amplitudes of scotopic a-, b-, and c-waves were significantly increased 1 day after injection with 15 mg/kg of NaIO3 by more than two-fold. (D, E, F) Amplitudes of scotopic electroretinograms (ERGs) at 3 and 7 days after injection. The results are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). A t-test/one/two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey's multiple comparisons test was conducted between the mean amplitudes in all pair combinations. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001. n = 6 mice in the PBS and NaIO3-treated groups (1 day), n = 8 mice in the NaIO3-treated groups (3 and 7 days).

In C57BL/6J mice, the scotopic b-wave amplitude started to show a decrease 2 days after an injection of 15 mg/kg of NaIO3, whereas the a-wave amplitude returned to normal (Figs. 4D, E). The mean amplitudes of scotopic ERG a- and b-waves were reduced 3 days after NaIO3 injection in C57BL/6J mice (Figs. 4G, H). The scotopic c-wave amplitude, which in part reflects RPE function, gradually decreased after NaIO3 injection, trending downwards starting at day 2 and significantly decreasing by days 3 and 7 in C57BL/6J mice (Figs. 4F, I).

Compared with C57BL/6J mice, 129/SV-E mice showed later functional loss under the same dosing of NaIO3 (Figs. 5D, E). As in C57BL/6J mice, the overall ERG waveforms of 129/SV-E mice at 1 and 3 days after injection also showed dramatic increases in the mean scotopic a-, b-, and c-wave amplitudes, with high variation in the treated group. There was a significant decrease in mean scotopic a- and b-wave amplitudes at 7 days after NaIO3 injection in 129/SV-E mice (Figs. 5D, E). The mean amplitudes of scotopic ERG c-waves did not change until 1 week after 15 mg/kg NaIO3 injection in 129/SV-E mice (Fig. 5F).

Morphologic Retinal Degeneration After NaIO3 Injection

In Vivo Retinal Imaging

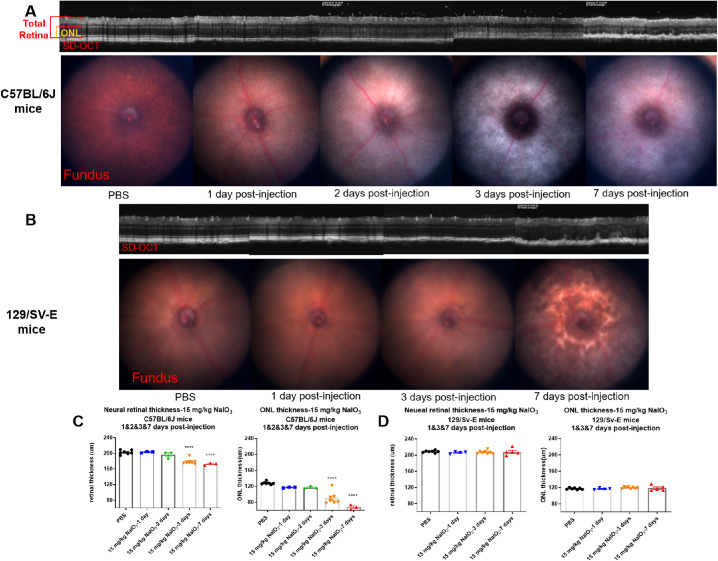

In vivo imaging indicated that morphologic changes in the retina were similar to functional losses in both strains. C57BL/6J mice developed severe damage earlier than 129/SV-E mice did after systemic exposure to the same dose of NaIO3, suggesting that C57BL/6J mice are more sensitive than 129/SV-E mice are in terms of response to toxicity of NaIO3.

Representative circular SD-OCT images of the central retina are shown in Figure 6 at a 100 µm radius from the ONH. These SD-OCT images were collected at 1, 2, 3, and 7 days after the administration of 15 mg/kg NaIO3. Divisions between the retinal layers were clear in PBS-treated mice of both strains, and it was easy to segment each individual retinal layer; however, sharp borders between the layers disappeared gradually in the treated groups. Early fading of the ellipsoid zone line at day 1 after injection in C57BL/6J mice and day 3 after injection in 129/SV-E mice was observed (Figs. 6A, B). Disappearance of the ellipsoid zone line indicated the early disruption of photoreceptors. Meanwhile, highly reflective spots appeared in the ONL, and some white dots or specks were detected in the vitreous body. Fundus photography revealed a pale fundus and fuzzy white blotches compared with the PBS group (Fig. 6A). Heavy mottling was apparent at 3 days after injection in C57BL/6J and 7 days after injection in 129/SV-E mice.

Figure 6.

SD-OCT and fundus images of C57BL/6J and 129/SV-E mice after injection with 15 mg/kg of NaIO3. (A, B) Representative SD-OCT and Micron IV fundus photography for each day after 15 mg/kg of NaIO3 treatment of C57BL/6J mice and 129/SV-E mice; red and orange brackets show the regions used for neural retina and ONL thickness measurement. (C, D) Quantification of SD-OCT images. The results are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey's multiple comparisons test was conducted between the mean thickness measurements in all possible pair combinations. ****P < 0.0001. n = 3–8 in the C57BL/6J mouse groups, n = 4–7 in the 129/SV-E mouse groups.

The thicknesses of the ONL and neural retina were measured on SD-OCT cross-sectional tomograms. Initially, the ONL and neural retinal thickness did not show decreases (at 1 and 2 days after injection with 15 mg/kg NaIO3; Fig. 6C). However, at 3 days and 7 days, obvious disruption and thinning of the retina were detected in C57BL/6J mice (Fig. 6C); the ONL and full retina both thinned, the photoreceptor layer became less visible, and more white dots appeared.

In the treated 129/SV-E mice, structural degradation, irregular folds, misalignments, and high reflectivity regions appeared in the ONL at 7 days after NaIO3 exposure (Fig. 6B). Fundus photography suggested mottling in the central retina. However, such changes were not detected in this group at 1 day and 3 days after injection. The ONL and neural retinal thickness were measured from the SD-OCT images. Statistical analysis revealed that the ONL and neural retinal thickness did not change after systemic exposure to 15 mg/kg NaIO3 (Fig. 6D) in the 129/SV-E mice. However, there was a noticeable increase in the variability of the measurements, possibly suggesting an underlying pathology.

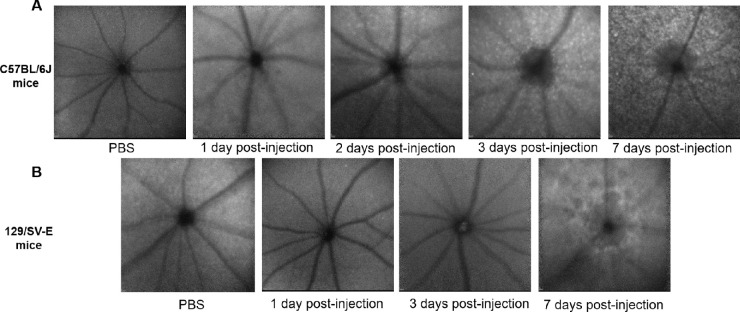

The HRA-BAF in Figure 7 paralleled the SD-OCT and fundus image results. The number of small punctate hyperautofluorescent white spots progressively increased and became widespread after NaIO3 treatment in C57BL/6J mice (Fig. 7A). Different from C57BL/6J mice, no obvious white spots were observed even 7 days after injection in 129/SV-E mice (Fig. 7B). Instead, some larger hypofluorescent spots appeared, interspersed with a weak increase in background autofluorescence, indicating possible atrophy of the RPE layer, which correlated with a mottled fundus appearance observed via color fundus photography (Fig. 6B).

Figure 7.

In vivo Spectralis en face images (with BAF) of NaIO3-induced RPE damage in two mouse strains. Each image is from a different mouse. Representative morphology at the layer of the photoreceptor–RPE interface. (A) Representative images from C57BL/6J mice. (B) Representative images from 129/SV-E mice.

Histologic Findings

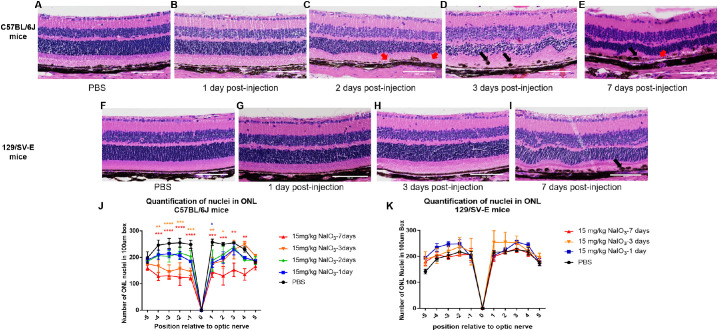

We examined fixed retinal tissues by conventional histology with hematoxylin and eosin staining. Compared with the eyes in the PBS-treated groups, which had well-organized nuclear layers and an intact regular monolayer of RPE cells, the NaIO3-treated C57BL/6J mice had irregular folds in the ONL and disorganized arrangement of photoreceptor inner and outer segments 2 days after injection. RPE cells were swollen, and the monolayer was interrupted by day 2 (Fig. 8C). There was extensive structural disruption at days 3 and 7 (Figs. 8D, E). In particular, the black arrow in Figure 8D illustrates pigmented dots, apparently melanin depositions, RPE cell migration, or melanin fragments engulfed by immune cells that were dragged into the depths of the inner layers of the retina. For 129/SV-E mice, there was no sign of ONL degeneration at days 1 or 3 based on the histologic findings. Disorganization of ONL and RPE disruption became evident at day 7 after injection (Fig. 8I).

Figure 8.

Micrographs of hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained paraffin-imbedded retinal sections of C57BL/6J and 129/SV-E mice treated with 15 mg/kg of NaIO3 at different time points. (A–E) Representative images of H&E staining for C57BL/6J mice are from a region of 250–750 µm from the optic nerve. RPE layer discontinuities are indicated with red arrows. Melanin deposition “balls” appeared in the RPE layer at days 2 and 3 (black arrows). (F–I) Representative images of H&E staining for 129/SV-E mice from a region of 250 to 750 µm from the optic nerve. Melanin deposition also appeared in and on the RPE layer at day 7 (black arrow). (J, K) Quantification of nuclei in the ONL for C57BL/6J and 129/SV-E mice. Nuclei counts in 10 discrete regions of retina sections from the ONH both in the superior (+) and inferior (–) directions in the ONL. Each region corresponds to 100 µm of arc length of retina. A two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey's multiple comparisons test was conducted between the mean nuclei counts in all pair combinations. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001. Sample sizes: n = 3–5 in C57BL/6J groups, n = 3–4 in 129/SV-E mice groups. Scale bar: 100 microns.

Density of Nuclei

The ONL of NaIO3-treated C57BL/6J mice exhibited a discernable decrease in thickness at day 3 after injection, indicating the loss of photoreceptor cells (Fig. 8D). The quantification of the ONL nuclear counts at days 1 and 2 after injection revealed a trending decrease of nuclei numbers, leading to a significant decrease in the number of nuclei in the ONL at 3 days after injection in C57BL/6J mice (Figs. 8D, 8J).

For the NaIO3-treated 129/SV-E mice, ONL nuclear counting did not detect the loss of photoreceptor cells, but there were clear waves, spacing changes, and increased variability in the sizes and shapes of nuclei and irregularities in the ONL layering at 7 days after injection (Figs. 8I, K). The subtle difference in the neural retinal thickness and the number of ONL nuclei between the C57BL/6J and 129/SV-E strains (PBS treated [black in all figures]) should be noted (Figs. 8J, K). The C57BL/6J neural retinal thickness was thinner overall but the retina had a slightly larger number of nuclei than the 129/SV-E mice did.

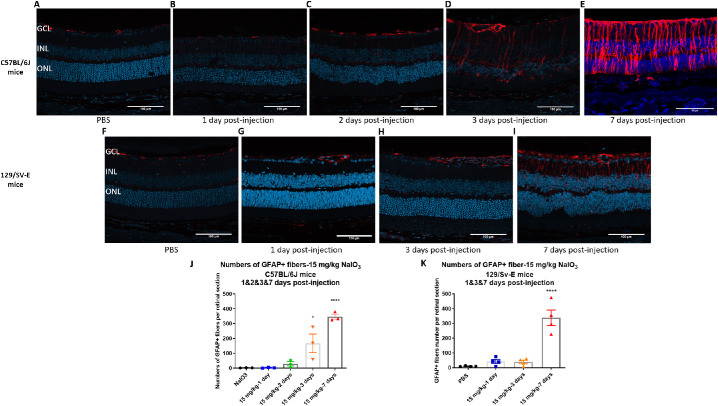

Müller Cell Activation

The activation of astrocytes and Müller cells was assessed by GFAP immunochemistry for the NaIO3-treated groups. In the PBS groups, GFAP immunoreactivity was only exhibited in the retinal ganglion cell layer and optic nerve (Figs. 9A, F). Otherwise, the GFAP signal in the ganglion cell layer significantly increased at day 3, but not at days 1 or 2, along with radial expression extending throughout the inner nuclear layer and ONL; this result indicated gliosis of Müller cells 3 and 7 days after injection in C57BL/6J mice (Figs. 9A–E, 9J). In 129/SV-E mice, the GFAP signal was intense in the ganglion cell layer and in a radial pattern at day 7 after NaIO3 treatment, but not at day 1 or 3 after injection (Figs. 9G, H, I, K); this result is in accordance with the functional and morphologic damage.

Figure 9.

Increased GFAP staining in the ganglion cell layer after administration with 15 mg/kg of NaIO3 in both strains. GFAP was labeled with GFAP antibody (red) and nuclei with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (blue). Representative morphologic images of GFAP staining from the region of 250–750 µm from the optic nerve. (A–I) Representative images from C57BL/6J and 129/SV-E mice. (J, K) The number of GFAP+ fibers spanning from the ganglion cell layer into and across the inner nuclear layer per retinal section in both strains. A one-way ANOVA with Tukey's multiple comparisons test was conducted between the mean nuclei counts in all pair combinations. *P < 0.05, ****P < 0.0001. Sample sizes: n = 3 in C57BL/6J groups, n = 4 in 129/SV-E Groups. Scale bar: 100 microns.

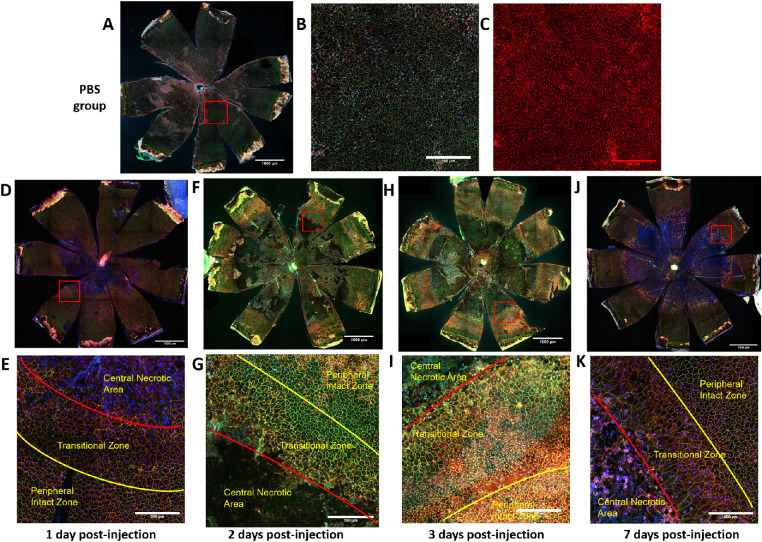

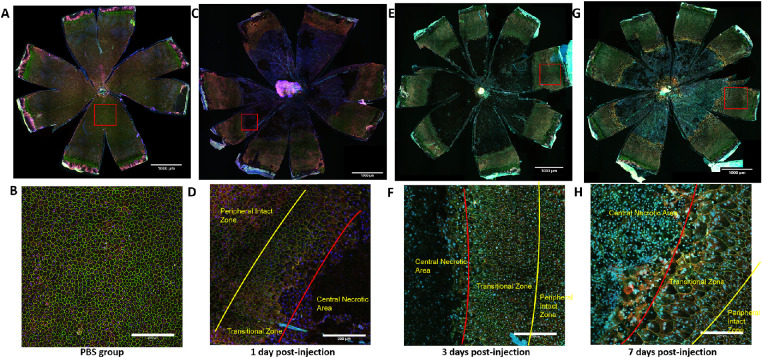

Morphologic Changes of the RPE Layer and Loss of RPE Cells

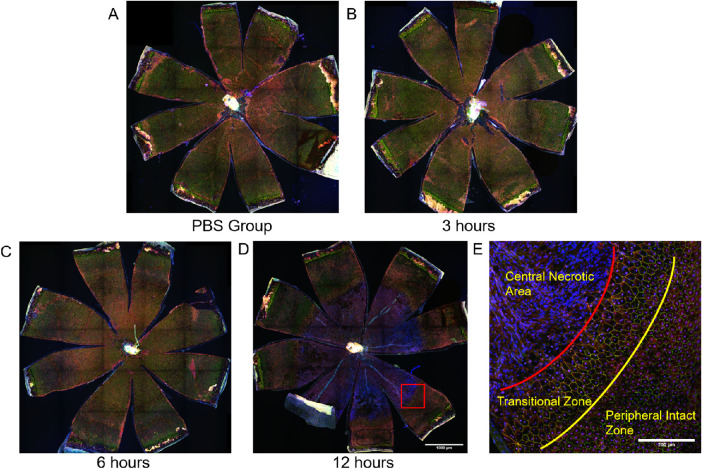

To test the RPE for hypothesized morphologic damage after NaIO3 treatment, we performed confocal microscopy on immunofluorescent staining of ZO-1, alpha-catenin, and Hoechst 33258 on RPE flatmounts. This approach revealed that RPE cells lost normal cell boundary patterns and that cells fused or severely stretched in the posterior central region within 1 day of injection with 15 mg/kg of NaIO3 in C57BL/6J mice (Fig. 10D). Similar death patterns also appeared in 129/SV-E mice, where central RPE cells were damaged or completely lost (Fig. 11C). This heavy damage was evident in flatmount preparations, despite no obvious damage seen with in vivo imaging at day 1 (Figs. 10D, E). No RPE cell death was observed in the PBS-treated group, where the flatmounts were uniformly covered with intact and regular RPE cells. As shown in Figure 10C, α-catenin closely localized to the tight junction collar near the apical face of the RPE cells in the PBS group.

Figure 10.

Systemic exposure to NaIO3 caused RPE cells to lose their normal structure and patterning. RPE cells chiefly died in the center to midperiphery in C57BL/6J mice. The RPE flatmounts were immunostained for ZO-1 (green), α-catenin (red), and Hoechst 33258 (blue). (A) RPE flatmounts from the PBS group. (B) High-resolution image from the PBS group, normally mononucleate and binucleate polygonal RPE cells did not exhibit a cytosolic α-catenin signal. (C) High-resolution image from the PBS group with only red channel (α-catenin). (D, F, H, J) Representative RPE flatmounts from NaIO3-treated C57BL/6J mouse groups. (E, G, I, K) High-resolution images of the transition zone in RPE flatmounts from NaIO3-treated groups. Scale bar in A, D, F, H, J: 1000 microns; scale bar in B, C, E, G, I, K: 200 microns.

Figure 11.

RPE layers in response to systemic exposure to NaIO3 in 129/SV-E mice. The RPE flatmounts from 129/SV-E mice were immunostained for ZO-1 (green), α-catenin (red), and Hoechst (blue). (A) RPE flatmounts from the PBS group. (B) High-resolution image from the PBS group. (C, E, G) Representative RPE flatmounts from NaIO3-treated 129/SV-E mouse groups. (D, F, H) High-resolution images of the transition zone in RPE flatmounts from NaIO3-treated groups. RPE cells near the center were highly irregular in shape and size. Scale bar in A, C, E, and G: 1000 microns; scale bar in B, D, F, and H: 200 microns.

In the NaIO3-treated mice (regardless of strain), there were three different morphologic zones of RPE cells laid out concentrically from the ONH. First, centered on the ONH and in the posterior through the midperiphery, there was a large single zone that included many large patches that lacked evidence of RPE cells. In adjacent patches of this central zone, the remaining RPE cells had lost their regular shape and ZO-1 staining, only a little residual α-catenin staining remained, and the number of cells was diminished and generally looked moth-eaten. It appeared that everything within this central zone was dead or dying, patchy, debris filled, or barren. It took days for this central zone to fully “bloom” into a completely barren lesion, but the distinct large size of the lesion and the extent of the barren patch were remarkable and present from the start. The underlying choroid showed through because of the absence of melanin granules from losing the RPE in this barren zone. Second, there was a ring-like transitional zone of abnormally shaped RPE cells at a midperipheral level. There were some RPE cells that were highly variable in size. The RPE cells were extremely large, stretched, and irregularly shaped, and they had multiple nuclei. Third, at the far periphery, there was a zone of RPE cells that had mostly normal cell features of regular size and shape mixed with some radially elongated irregular cells, but even here at the far periphery, there were dysmorphic RPE cells (Figs. 10E, G, I, K; Figs. 11D, F, H).

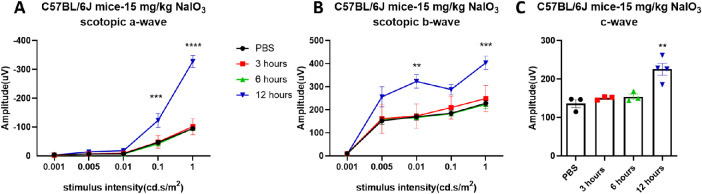

Functional and Morphologic Changes on Day 1

To better understand the retinal functional and morphologic changes in the early stages after systemic exposure to NaIO3, we measured scotopic ERGs at 3, 6, and 12 hours after injection in C57BL/6J mice. In these mice, the mean amplitudes of scotopic ERG a-, b-, and c-waves increased at 12 hours post NaIO3 injection (Fig. 12), roughly doubling in magnitude compared with the PBS group. Similarly, as shown in Figure 13, the RPE layer retained its normal tight junction structure at 6 hours after injection, but extensive damage was detected at 12 hours after injection (Figs. 13D, E).

Figure 12.

Visual function changes within 12 hours after NaIO3 injection. Amplitudes of scotopic a-, b-, and c-wave all sharply increased about two-fold at 12 hours after injection with 15 mg/kg of NaIO3. The results are presented as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). A one/two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Sidak's/Tukey's multiple comparisons test was conducted between the mean amplitudes in all pair combinations. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001. n = 3–4 mice.

Figure 13.

RPE layers lost their normal structure and became disrupted at 12 hours after injection with 15 mg/kg of NaIO3 in C57BL/6J mice. The RPE flatmounts from C57BL/6J mice were immunostained for ZO-1 (green), α-catenin (red), and Hoechst (blue). (A) RPE flatmount from the PBS group. (B, C) RPE cells still maintain normal structure within 6 hours after injection. (D) RPE disruption appeared at 12 hours after injection. (E) High-resolution images of the transition zone in RPE flatmounts from NaIO3-treated groups. Scale bar in A, B, C, D: 1000 microns, scale bar in E: 200 microns.

Discussion

In this study, we found the lowest concentration of NaIO3 that consistently causes the same level of damage from mouse to mouse. This information is advantageous because a lower dose is associated with fewer side effects of treatment, which will help to elucidate authentic disease-initiating sequalae versus spurious drug effects that may obscure relevant mechanisms. We identified the time at which highly characteristic symptoms first initiated after injection, and we found the timing of early events during the disease course. In the future, these prerequisites will allow us to establish causal pathways that result in RPE and retinal cell dysfunction brought on by NaIO3.

Our central hypothesis was that treatment of mice with low-dose NaIO3 would allow a nuanced understanding of the early effects on the function and morphology of the RPE and retina. The premise was partially based on our prior experiences with the treatment of mice with systemic injections of NaIO3 at concentrations reported in the literature.16,25,35–41 In our hands, these treatment regimens produced losses in retinal function and tissue that were excessively rapid and severe, making the approach problematic as a model for a cause-and-effect analysis of retinal and RPE damage. We tested this hypothesis by investigating the effects of tail vein injections of various concentrations of NaIO3 on RPE/retina function and morphology in C57BL/6J and 129/SV-E mice, looking for a threshold dose at which the steps in disease progression could be teased out. Our observations indicate the following:

-

1.

Threshold dose: A single injection at 15 mg/kg is the lowest dose that induced stable and repeatable RPE damage in both strains.

-

2.

Bracketing the minimum dose: A single tail vein injection of 10 mg/kg of NaIO3 did not consistently induce functional loss or morphologic changes of the retina in either strain (Figs. 1–2).

-

3.

Functional and morphologic strain differences: Although both mouse strains reacted at the same low threshold dose, we confirmed and extended strain differences at this same low dose of NaIO3 on retinal function and structure.17,35,42,43 C57BL/6J mice were more sensitive and sensitive sooner to NaIO3 than 129/SV-E mice were, by all the measures that we tested, including ERGs, SD-OCTs, BAF, layer thicknesses by hematoxylin and eosin, disruption of RPE by flatmounts, and histology (see Figs. 1–13).

-

4.

Transiently increased ERG signals: Interestingly and unexpectedly, scotopic ERG waveform amplitudes were transiently and greatly increased within 24 hours following injection with 15 mg/kg of NaIO3 in both strains, although strain differences appeared at later times (as discussed elsewhere in this article). This effect is not noted in the literature, except by Sato's group, which identified supernormal transient b-waves in NaIO3-treated mice.44–46 We extended the observations from Sato et al to include earlier times after injection, lower doses of NaIO3, and additional mouse strains. We further found that scotopic a-, b-, and c-waves all transiently increase, and outcomes vary with strain and with the time of assessment, after injection. The transient increase in each wave's amplitude is large, at more than two-fold. This transient effect bears further investigation in future experiments to understand how a toxic process can be so significant and rapid (Figs. 4 and 5). Because the effect is not immediate, but takes more than 6 hours after injection to manifest (Figs. 4, 5, and 12), we wonder how the effect is mediated and which distinct cells47 and physiologic processes are required. Moreover, we wonder what processes then take over to cause deterioration of ERG signals and why they are slower in 129/SV-E versus C57BL/6J mice.13,25 There are many possibilities for governing the transient increase and subsequent deterioration of the ERGs. These include all the retinal, RPE, and choroidal cells, because they are all closely coupled physically and metabolically. Oxidative damage to macromolecules can stabilize them in either a continuously activated or inactive state. For example, oxidative damage could change the distribution of potassium in Müller cells or the subretinal space, affecting amplitudes of a-, b-, and c-waves.46,48 Many other potential initiating targets exist, including third-order neuronal cells,48 cone cells,17 ON-bipolar cells, and amacrine cell responses.49 NaIO3 may change the resistance of the RPE cells or other layers, directly affecting current flow and voltage differences measured in the ERG.50 These possibilities are now testable under our conditions.

-

5.

Effects on the c-wave: The c-wave amplitudes transiently increased in the first 24 hours after injection and then decreased in both mouse strains. The decreases in the c-waves followed the same pattern as other measures; they were evident in the C57/BL/6J mice earlier and faster than in the 129/SV-E mice (Figs. 4, 5). The RPE and Müller cells govern the c-wave,51–54 but with dependence on the a-wave. The c-wave was easy to collect and detected underlying disease in the RPE.

-

6.

Effects on live imaging: Live imaging revealed parallel strain-specific stress responses, but with subtle whitening, indicating structural changes associated with damage. Fundus BAF detected many small white spots at the level of the RPE in C57BL/6J mice but none in 129/SV-E mice, which instead had large hypofluorescent blotches (Fig. 7B). Many white spots were found by SD-OCT in C57BL/6J mice in the ONL and vitreous cavity (Fig. 6A). The precise identity of the white spots and blotches after NaIO3 treatment remains unknown.37 Future comparisons of white spots and histologic features are needed and are now feasible.

-

7.

Histopathologic cross-sections and RPE flatmount analysis: Similar to other responses, the histologic findings mirrored in vivo imaging, showing noted mouse strain differences (Fig. 8). The RPE layer became detached, and the RPE cells were swollen. RPE cells appeared in the subretinal space after NaIO3 injection (Fig. 8). No significant morphologic changes appeared at days 1 and 2 after injection, but the thickness of the full retina and counts of nuclei in the ONL trended downwards. The central retina degenerated more than the periphery did, which was similar to changes in the RPE layer en face. A massive breakdown of the mouse RPE sheet occurred between 6 and 12 hours after injection, in a single large central geographic lesion (Fig. 13D), which was surrounded by RPE cells in a transition zone between the barren center and the far periphery (Figs. 10E, G, I, K; Figs. 11D, F). ZO-1 staining detected highly elongated RPE cells with greater apical surface areas, multiple nuclei per cell, and irregularly shaped cells in this transition zone. Our images provide entire en face views showing where the RPE patches are missing. This gives a clear view of the spatiotemporal loss of the RPE after NaIO3 treatment. The damaged central posterior area appears suddenly and then does not grow in size. That is, the damaged area seems to be large and complete; it does not progress in size over time. The NaIO3 treatment results in a loosening and detachment of RPE cells from Bruch's membrane and, when the neural retina is peeled away from the RPE flatmount surface, RPE cells that have undergone epithelial to mesenchymal transition, RPE debris, and dying and dead RPE cells seem to be released from the central posterior aspect of the flatmount or remain weakly attached to the outer segment face of the neural retina. In the future, we may be able to quantify the amount of melanin pigment in wash solutions and on the surface of the neural retina, and this may represent a quantitative surrogate of the number of lost RPE cells and associated debris. Other mechanisms may be at play, including autophagy or phagocytosis by microglia or macrophages, which may metabolize RPE cells and debris, and may substantially account for the loss of RPE cells from the RPE sheet. These and related hypothesized explanations of the lost RPE cells centrally through the midperiphery are testable in the future.

-

8.

Remodeling in the transition zone: In the transition zone, the release of α-catenin into the cytosol is an early marker of a damage response.52,55 Rearrangement of α-catenin may reflect motility of RPE cells through epithelial to mesenchymal transition. The intracellular distribution of α-catenin changed in RPE cells in the transition zone in C57BL/6J mice, but was lesser and slower in 129/SV-E mice (Figs. 10 and 11), as with our other strain differences. Injection of NaIO3 induced upregulation of the genes involved in oxidative stress, inflammatory, and cell death signaling.56–58 Müller cells were activated in parallel to decreases in ERGs and morphometrics. These changes followed the same pattern of the more sensitive and earlier response in C57BL/6J mice and a later response in 129/SV-E mice (Fig. 9).

-

9.

The variability and unreliability of NaIO3 as a model in the literature: The early and rapid acute increase in ERG signals followed by the more gradual loss in ERG signals may help to explain some of the variability in the previously reported results regarding the NaIO3 model of RPE death,17,37,46 creating what seemed to be irreproducible and inexplicable variations and differences that may not really exist. Here, our early and extensive temporal series may help to explain previous variability in the NaIO3 injury model.

-

10.

Possible differences in blood flow in the central posterior versus the far periphery in the mouse eye: We do not know how or why the RPE cells in the periphery are spared compared with the heavier loss in the central RPE. We speculate that high concentrations of NaIO3 first flow through the central inner retinal vessels. NaIO3 may experience dilution as the flow passes from central to peripheral, and this pattern of flow and dilution might explain the heavier loss centrally, but this awaits future experiments. There could be many other explanations, including that the peripheral RPE are more resistant than central owing to a location-specific or cell-specific difference. Later RPE cell death seems to be limited, and this is a topic of ongoing experiments. Other possibilities to explain the central location of cell death loss abound but depend on the details of retinal and choroidal flow of blood in the mouse, and these may be strain specific.59

-

11.

The transition zone as a possible model of GA lesions: The damage in the transition zone (with extremes in shapes, sizes, and patterns of RPE cells) resembles some of the RPE cells surrounding GA lesions in AMD.60–62 The barren patch that is central–posterior in the mouse in some ways resembles the denuded patches of GA lesions in AMD. The possible invasion of transition zone RPE cells into the denuded lesion may be a useful model for considering aspects of wound healing.63,64 It could be that, as a part of a wound response, these initially healthy transition zone cells rapidly expand to cover severely damaged atrophic patches.

-

12.

Experiments beyond the scope of the present study: The considerable disappearance of RPE cells from the central to midperiphery of the RPE sheet after NaIO3 injection is rapid and requires further investigation to resolve the following questions. What accounts for this rapid loss? Is this loss due to cell death, detachment, and migration of living RPE cells, or their embedment into the neural retina? The loss of basal attachment to Bruch's membrane coupled with increased binding to outer segments could explain the loss of cells from the surface of the RPE sheet preparation when peeling off the neural retina. Many of these and related questions can be investigated now that reliable experimental conditions are available for the C57BL/6J and the 129/SV-E strains of mice. Quantifiable toxic symptoms were seen earlier in C57BL/6J mice compared with 129/SV-E mice. A limited number of genes may control these differences between the two strains. It may be possible to identify these genes by using forward genetics and recombinant inbred mice, and such studies might be mechanistically informative.65–67

-

13.

The NaIO3 model as an RPE damage model: Many other researchers have raised the issue of whether the NaIO3 model is truly an RPE-only damage model or whether it is truly a retina damage model that heavily involves the RPE. The current lack of understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying NaIO3 damage and exactly which organelles and cellular processes it targets is regrettable. We hope that our refinement of the model, the reduction in dose, and better appreciation of transient early effects, will foster simple mechanistic experiments in the future to understand the origins of NaIO3 damage in the RPE and retina.

Conclusions

In this study, we observed differences in functional and morphologic responses to low doses of systemic NaIO3 administration between two strains of inbred mice, which are among the most heavily used in biomedical research. Although 129/SV-E mice are more resistant to NaIO3 RPE toxicity than C57BL/6J mice are, in each strain, a single tail vein injection of 15 mg/kg of NaIO3 was the lowest dose to induce stable and repeatable RPE damage. NaIO3 treatment also greatly, but transiently, increased the ERG wave amplitudes in both strains. It is important to discover the different responses between these two strains in chemically induced RPE damage. We conclude that the effect of NaIO3 is distinctly different time and dose wise. Taken from two mouse strains that are widely used in NaIO3-induced RPE damage, our data provide a reference for optimal dosage and timepoints for further comparisons.

Acknowledgments

Supported by National Institutes of Health grants (R01EY028450, R01EY021592, P30EY006360, F31EY028855, R01EY028859, T32EY07092, and T32GM008490); the Abraham and Phyllis Katz Foundation; Veterans Affairs Rehabilitation Research & Development (I01RX002806,I21RX001924 and C9246C); and the joint training program between Emory University School of Medicine and Xiangya School of Medicine, Central South University.

Disclosure: N. Zhang, None; X. Zhang, None; P.E. Girardot, None; M.A. Chrenek, None; J.T. Sellers, None; Y. Li, None; Y.-K. Kim, None; V.R. Summers, None; S. Ferdous, None; D.A. Shelton, None; J.H. Boatright, None; J.M. Nickerson, None

References

- 1. Kampik D, Basche M, Luhmann UFO, et al.. In situ regeneration of retinal pigment epithelium by gene transfer of E2F2: a potential strategy for treatment of macular degenerations. Gene Ther. 2017; 24(12): 810–818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Reisenhofer MH, Balmer JM, Enzmann V.. What can pharmacological models of retinal degeneration tell us? Curr Mol Med. 2017; 17(2): 100–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Damico FM, Gasparin F, Scolari MR, Pedral LS, Takahashi BS.. New approaches and potential treatments for dry age-related macular degeneration. Arq Bras Oftalmol. 2012; 75(1): 71–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sorsby A, Harding R.. Oxidizing agents as potentiators of the retinotoxic action of sodium fluoride, sodium iodate and sodium iodoacetate. Nature. 1966; 210(5040): 997–998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bhutto IA, Ogura S, Baldeosingh R, et al.. An acute injury model for the phenotypic characteristics of geographic atrophy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2018; 59(4): AMD143–AMD151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mones J, Leiva M, Pena T, et al.. A swine model of selective geographic atrophy of outer retinal layers mimicking atrophic AMD: a phase I escalating dose of subretinal sodium iodate. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2016; 57(10): 3974–3983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zieger M, Punzo C.. Improved cell metabolism prolongs photoreceptor survival upon retinal-pigmented epithelium loss in the sodium iodate induced model of geographic atrophy. Oncotarget. 2016; 7(9): 9620–9633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sorsby A. Experimental pigmentary degeneration of the retina by sodium iodate. Br J Ophthalmol. 1941; 25(2): 58–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Koh AE, Alsaeedi HA, Rashid MBA, et al.. Retinal degeneration rat model: a study on the structural and functional changes in the retina following injection of sodium iodate. J Photochem Photobiol B. 2019; 196: 111514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hanus J, Anderson C, Sarraf D, Ma J, Wang S.. Retinal pigment epithelial cell necroptosis in response to sodium iodate. Cell Death Discov. 2016; 2: 16054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hariri S, Moayed AA, Choh V, Bizheva K.. In vivo assessment of thickness and reflectivity in a rat outer retinal degeneration model with ultrahigh resolution optical coherence tomography. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012; 53(4): 1982–1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ou Q, Zhu T, Li P, et al.. Establishment of retinal degeneration model in rat and monkey by intravitreal injection of sodium iodate. Curr Mol Med. 2018; 18(6): 352–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ahn SM, Ahn J, Cha S, et al.. Morphologic and electrophysiologic findings of retinal degeneration after intravitreal sodium iodate injection following vitrectomy in canines. Sci Rep. 2020; 10(1): 3588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Yang Y, Ng TK, Ye C, et al.. Assessing sodium iodate-induced outer retinal changes in rats using confocal scanning laser ophthalmoscopy and optical coherence tomography. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2014; 55(3): 1696–1705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Machalinska A, Lejkowska R, Duchnik M, et al.. Dose-dependent retinal changes following sodium iodate administration: application of spectral-domain optical coherence tomography for monitoring of retinal injury and endogenous regeneration. Curr Eye Res. 2014; 39(10): 1033–1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Moriguchi M, Nakamura S, Inoue Y, et al.. Irreversible photoreceptors and RPE cells damage by intravenous sodium iodate in mice is related to macrophage accumulation. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2018; 59(8): 3476–3487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chowers G, Cohen M, Marks-Ohana D, et al.. Course of sodium iodate-induced retinal degeneration in albino and pigmented mice. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2017; 58(4): 2239–2249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Upadhyay M, Milliner C, Bell BA, Bonilha VL.. Oxidative stress in the retina and retinal pigment epithelium (RPE): role of aging, and DJ-1. Redox Biol. 2020; 37: 101623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Liu YL, Li RC, Xie J, et al.. Protective effect of hydrogen on sodium iodate-induced age-related macular degeneration in mice. Front Aging Neurosci. 2018; 10: 389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hwang N, Kwon MY, Woo JM, Chung SW.. Oxidative stress-induced pentraxin 3 expression human retinal pigment epithelial cells is involved in the pathogenesis of age-related macular degeneration. Int J Mol Sci. 2019; 20(23): 6028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Su F, Spee C, Araujo E, et al.. A novel HDL-mimetic peptide HM-10/10 protects RPE and photoreceptors in murine models of retinal degeneration. Int J Mol Sci. 2019; 20(19): 4807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Jadeja RN, Jones MA, Abdelrahman AA, et al.. Inhibiting microRNA-144 potentiates Nrf2-dependent antioxidant signaling in RPE and protects against oxidative stress-induced outer retinal degeneration. Redox Biol. 2020; 28: 101336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kiuchi K, Yoshizawa K, Shikata N, Moriguchi K, Tsubura A.. Morphologic characteristics of retinal degeneration induced by sodium iodate in mice. Curr Eye Res. 2002; 25(6): 373–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Balmer J, Zulliger R, Roberti S, Enzmann V.. Retinal cell death caused by sodium iodate involves multiple caspase-dependent and caspase-independent cell-death pathways. Int J Mol Sci. 2015; 16(7): 15086–15103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Zhou P, Kannan R, Spee C, et al.. Protection of retina by alphaB crystallin in sodium iodate induced retinal degeneration. PLoS One. 2014; 9(5): e98275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Schnabolk G, Obert E, Banda NK, Rohrer B.. Systemic inflammation by collagen-induced arthritis affects the progression of age-related macular degeneration differently in two mouse models of the disease. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2020; 61(14): 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Huber G, Beck SC, Grimm C, et al.. Spectral domain optical coherence tomography in mouse models of retinal degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009; 50(12): 5888–5895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mary-Sinclair MN, Wang X, Swanson DJ, et al.. Varied manifestations of persistent hyperplastic primary vitreous with graded somatic mosaic deletion of a single gene. Mol Vis. 2014; 20: 215–230. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ferdous S, Grossniklaus HE, Boatright JH, Nickerson JM.. Characterization of LSD1 expression within the murine eye. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2019; 60(14): 4619–4631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bankhead P, Loughrey MB, Fernandez JA, et al.. QuPath: open source software for digital pathology image analysis. Sci Rep. 2017; 7(1): 16878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Sellers JT, Chrenek MA, Girardot PE, et al.. Initial assessment of lactate as mediator of exercise-induced retinal protection. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2019; 1185: 451–455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Augustine J, Pavlou S, Ali I, et al.. IL-33 deficiency causes persistent inflammation and severe neurodegeneration in retinal detachment. J Neuroinflammation. 2019; 16(1): 251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Boatright JH, Dalal N, Chrenek MA, et al.. Methodologies for analysis of patterning in the mouse RPE sheet. Mol Vis. 2015; 21: 40–60. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Zhang X, Girardot PE, Sellers JT, et al.. Wheel running exercise protects against retinal degeneration in the I307N rhodopsin mouse model of inducible autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa. Mol Vis. 2019; 25: 462–476. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Berkowitz BA, Podolsky RH, Lenning J, et al.. Sodium iodate produces a strain-dependent retinal oxidative stress response measured in vivo using QUEST MRI. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2017; 58(7): 3286–3293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hanus J, Anderson C, Ma J, Wang S.. RPE necroptosis in mouse model of sodium iodate–induced RPE degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2016; 57(12): 5789. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Wang J, Iacovelli J, Spencer C, Saint-Geniez M.. Direct effect of sodium iodate on neurosensory retina. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2014; 55(3): 1941–1953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Sreekumar PG, Li Z, Wang W, et al.. Intra-vitreal alphaB crystallin fused to elastin-like polypeptide provides neuroprotection in a mouse model of age-related macular degeneration. J Control Release. 2018; 283: 94–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ge Y, Zhang A, Sun R, et al.. Penetratin-modified lutein nanoemulsion in-situ gel for the treatment of age-related macular degeneration. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2020; 17(4): 603–619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Mulfaul K, Ozaki E, Fernando N, et al.. Toll-like receptor 2 facilitates oxidative damage-induced retinal degeneration. Cell Rep. 2020; 30(7): 2209–2224.e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. He H, Wei D, Liu H, et al.. Glycyrrhizin protects against sodium iodate-induced RPE and retinal injury though activation of AKT and Nrf2/HO-1 pathway. J Cell Mol Med. 2019; 23(5): 3495–3504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Redfern WS, Storey S, Tse K, et al.. Evaluation of a convenient method of assessing rodent visual function in safety pharmacology studies: effects of sodium iodate on visual acuity and retinal morphology in albino and pigmented rats and mice. J Pharmacol Toxicol Methods. 2011; 63(1): 102–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Berkowitz BA, Podolsky RH, Lenning J, et al.. Sodium iodate produces a strain-dependent retinal oxidative stress response measured in vivo using QUEST MRI. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2017;58(7): 3286–3293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Hosoda L, Adachi-Usami E, Mizota A, Hanawa T, Kimura T.. Early effects of sodium iodate injection on ERG in mice. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh). 1993; 71(5): 616–622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Sugimoto S, Imawaka M, Kurata K, et al. [A procedure for recording electroretinogram (ERG) and effect of sodium iodate on ERG in mice]. J Toxicol Sci. 1996; 21(Suppl 1): 15–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Adachi-Usami E, Mizota A, Ikeda H, Hanawa T, Kimura T.. Transient increase of b-wave in the mouse retina after sodium iodate injection. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1992; 33(11): 3109–3113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Pinto LH, Invergo B, Shimomura K, Takahashi JS, Troy JB.. Interpretation of the mouse electroretinogram. Doc Ophthalmol. 2007; 115(3): 127–136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Tanaka M, Machida S, Ohtaka K, Tazawa Y, Nitta J.. Third-order neuronal responses contribute to shaping the negative electroretinogram in sodium iodate-treated rats. Curr Eye Res. 2005; 30(6): 443–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Hirasawa H, Miwa N, Watanabe SI.. GABAergic and glycinergic systems regulate ON-OFF electroretinogram by cooperatively modulating cone pathways in the amphibian retina. Eur J Neurosci. 2020; 53(5): 1428–1440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. I.P. The Electroretinogram: ERG. 2001 May 1 [Updated 2007 Jun 27]. In: Kolb H FE, Nelson R, ed. The Organization of the Retina and Visual System [Internet]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK11554/: Salt Lake City (UT): University of Utah Health Sciences Center; 1995. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Kinoshita J, Peachey NS.. Noninvasive electroretinographic procedures for the study of the mouse retina. Curr Protoc Mouse Biol. 2018; 8(1): 1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Matsuura T, Miller WH, Tomita T.. Cone-specific c-wave in the turtle retina. Vision Res. 1978; 18(7): 767–775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Biswal MR, Justis BD, Han P, et al.. Daily zeaxanthin supplementation prevents atrophy of the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) in a mouse model of mitochondrial oxidative stress. PLoS One. 2018; 13(9): e0203816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Shahi PK, Liu X, Aul B, et al.. Abnormal electroretinogram after Kir7.1 channel suppression suggests role in retinal electrophysiology. Sci Rep. 2017; 7(1): 10651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Donaldson KJ, Sellers JT, Boatright JH, Nickerson JM.. Alpha-catenin is a novel marker for identifying abnormal morphology following surgical damage of the RPE. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2017; 58(8): 624. [Google Scholar]

- 56. Ahn SM, Ahn J, Cha S, et al.. The effects of intravitreal sodium iodate injection on retinal degeneration following vitrectomy in rabbits. Sci Rep. 2019; 9(1): 15696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Yang Z, Wang KK.. Glial fibrillary acidic protein: from intermediate filament assembly and gliosis to neurobiomarker. Trends Neurosci. 2015; 38(6): 364–374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. de Hoz R, Rojas B, Ramirez AI, et al.. Retinal macroglial responses in health and disease. Biomed Res Int. 2016; 2016: 2954721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Jiao C, Adler K, Liu X, et al.. Visualization of mouse choroidal and retinal vasculature using fluorescent tomato lectin perfusion. Transl Vis Sci Technol. 2020; 9(1): 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Zhang Q, Chrenek MA, Bhatia S, et al.. Comparison of histologic findings in age-related macular degeneration with RPE flatmount images. Mol Vis. 2019; 25: 70–78. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Rashid A, Bhatia SK, Mazzitello KI, et al.. RPE cell and sheet properties in normal and diseased eyes. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2016; 854: 757–763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Bhatia SK, Rashid A, Chrenek MA, et al.. Analysis of RPE morphometry in human eyes. Mol Vis. 2016; 22: 898–916. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Tamiya S, Kaplan HJ.. Role of epithelial-mesenchymal transition in proliferative vitreoretinopathy. Exp Eye Res. 2016; 142: 26–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Gao H, Hollyfield JG.. Aging of the human retina. Differential loss of neurons and retinal pigment epithelial cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1992; 33(1): 1–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Lu Y, Zhou D, King R, et al.. The genetic dissection of Myo7a gene expression in the retinas of BXD mice. Mol Vis. 2018; 24: 115–126. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. King R, Li Y, Wang J, Struebing FL, Geisert EE.. Genomic locus modulating IOP in the BXD RI mouse strains. G3 (Bethesda). 2018; 8(5): 1571–1578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. King R, Struebing FL, Li Y, et al.. Genomic locus modulating corneal thickness in the mouse identifies POU6F2 as a potential risk of developing glaucoma. PLoS Genet. 2018; 14(1): e1007145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]