Abstract

Background

Continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) and high-flow nasal oxygen (HFNO) have been used to manage hypoxaemic respiratory failure secondary to coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pneumonia. Limited data are available for patients treated with noninvasive respiratory support outside of the intensive care setting.

Methods

In this single-centre observational study we observed the characteristics, physiological observations, laboratory tests and outcomes of all consecutive patients with COVID-19 pneumonia between April 2020 and March 2021 treated with noninvasive respiratory support outside of the intensive care setting.

Results

We report the outcomes of 140 patients (mean±sd age: 71.2±11.1, 65% male (n=91)) treated with CPAP/HFNO outside of the intensive care setting. Overall mortality was 59% and was higher in those deemed unsuitable for mechanical ventilation (72%). The mean age of survivors was significantly lower than those who died (66.1 versus 74.4 years, p<0.001). Those who survived their admission also had a significantly lower median Clinical Frailty Score than the non-survivor group (2 versus 4, p<0.001). We report no significant difference in mortality between those treated with CPAP (n=92, mortality: 60%) or HFNO (n=48, mortality: 56%). Treatment was well tolerated in 86% of patients receiving either CPAP or HFNO.

Conclusions

CPAP and HFNO delivered outside of the intensive care setting are viable treatment options for patients with hypoxaemic respiratory failure secondary to COVID-19 pneumonia, including those considered unsuitable for invasive mechanical ventilation. This provides an opportunity to safeguard intensive care capacity for COVID-19 patients requiring invasive mechanical ventilation.

Short abstract

CPAP and HFNO are viable treatment options for hypoxaemic respiratory failure secondary to COVID-19, including in those unsuitable for invasive ventilation. These data show that these patients can be safely and effectively managed outside the ICU. https://bit.ly/36qdJsx

Introduction

Continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) and high-flow nasal oxygen (HFNO) are recommended by the British Thoracic Society (BTS) as the mainstay of noninvasive respiratory support for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) patients with severe hypoxaemic respiratory failure who are deemed unsuitable for mechanical ventilation [1]. The role of these noninvasive therapies has been examined in previous studies [2–5] with variation in the reported outcomes. Predominantly these report outcomes from inside intensive care units; however, there is also data from patients treated outside of this setting [6–8].

In this study we observed the characteristics and outcomes of consecutive patients with hypoxaemic respiratory failure secondary to COVID-19 pneumonia who received CPAP and HFNO on a respiratory support unit (RSU) between April 2020 and March 2021. The RSU is located on a standard COVID-19 respiratory ward but has enhanced staffing ratios, noninvasive patient monitoring and infection control precautions to facilitate the safe delivery of aerosol-generating procedures. We aimed to evaluate the utility of these methods of noninvasive respiratory support as a management option outside of the intensive care setting.

Methods

We undertook a single-centre, prospective observational study of consecutive patients treated for hypoxaemic respiratory failure with either CPAP or HFNO on a designated COVID-19 RSU at Hull University Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust (HUTH) between April 2020 and March 2021. We recorded patient characteristics, physiological observations, laboratory tests and clinical outcomes.

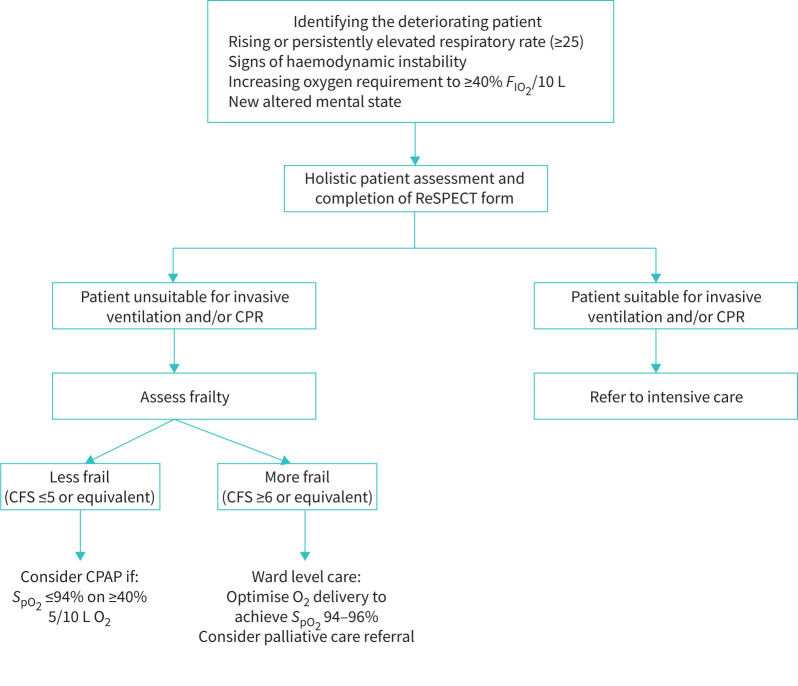

Patients were identified as requiring noninvasive respiratory support on clinical grounds and supported using a management algorithm designed and implemented at HUTH, based on current BTS recommendations [1]. Prior to the initiation of CPAP/HFNO, patients were assessed for suitability for invasive mechanical ventilation by the hospital's critical care outreach team including a senior intensive care physician and/or a senior respiratory physician. The decision-making process was holistic and included assessment of the patients’ premorbid condition, likelihood of a positive outcome, and the views of the patients and/or next of kin. The Clinical Frailty Score (CFS) [9], a 7-point scale which measures a patient's frailty based on their comorbid status as well as ability to carry out activities of daily living, was utilised as part of the holistic assessment to predict the likelihood of successful treatment with CPAP/HFNO. All decisions were documented as an advanced care plan in the clinical case records. This pathway can be visualised in figure 1. Individual patient care and advanced care planning were ultimately the responsibility of the treating clinical team. Both CPAP and HFNO were delivered in accordance with BTS guidelines and was overseen by specialists in respiratory medicine.

FIGURE 1.

Hull University Teaching Hospitals (HUTH) treatment algorithm for treating the deteriorating coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) patient. Broadly, patients with Clinical Frailty Score (CFS) score ≥6 were treated for ward-based care (not continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP)) only. Patients with a CFS score of ≤5 were to be discussed with a respiratory medicine consultant, for consideration of CPAP/high-flow nasal oxygen (HFNO). FIO2: inspiratory oxygen fraction; CPR: cardiopulmonary resuscitation. ReSPECT: Recommended Summary Plan for Emergency Care and Treatment; SpO2: oxygen saturation measured by pulse oximetry.

The primary outcome of interest in our study was inpatient mortality. Patient characteristics, modality of respiratory support received and outcome data were collected prospectively. Treatment tolerance was ascertained on a post hoc basis through review of patients’ adherence to therapies as documented in their clinical case records. In the event of missing data, retrospective case record and electronic patient record review was undertaken to input missing data items. All physiological parameters and laboratory markers included in the study are those taken prior to the initiation of CPAP/HFNO. Data collection was approved by the HUTH clinical governance committee.

Data are presented descriptively. Comparison of means was performed using t-tests, comparison of medians was performed using Mann–Whitney U-testing and comparison of proportions was compared using Chi Squared testing. Statistical significance was defined as a p-value of <0.05. All statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 26 (IBM, Chicago, IL, USA). Outcomes were analysed with patients assigned to HFNO or CPAP groups in two ways: firstly, based on initial treatment choice (intention-to-treat analysis (ITT)); and secondly, based on the highest level of support received (patients that received both HFNO and CPAP during their admission were analysed in the CPAP group).

Results

Patient characteristics and outcomes

Outcomes for 140 patients were observed: 65% (n=91) were male and mean±sd age was 71.2±11.1 years. Overall inpatient mortality was 59% (n=82). In the 98 patients that were considered unsuitable for invasive ventilation, inpatient mortality was 72% (n=71). Of the 42 patients deemed suitable for invasive mechanical ventilation, 48% (n=20) were admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) and 11 were treated with invasive mechanical ventilation. All 11 patients treated with mechanical ventilation died, reflecting 26% of all patients treated with noninvasive respiratory support that were considered suitable for invasive ventilation.

Comorbidities

Frequently observed comorbidities included hypertension (HTN) (59%, n=83), obesity (37%, n=52), diabetes mellitus (DM) (29%, n=40) and ischaemic heart disease (IHD) (27%, n=38). When compared to the survivor group, there was a significantly higher proportion of patients with IHD and obesity in the non-survivor group (12% versus 38%, p=0.001 and 45% versus 71%, p=0.022, respectively). There were also differences between the survivor and non-survivor groups in the prevalence of respiratory diseases, with non-survivors having a higher prevalence of COPD (33% versus 16%, p=0.031) and the survivor group having a higher proportion of patients with asthma (17% versus 6%, p=0.026). We also observed a higher proportion of patients with previous cancer in the non-survivor group (15% versus 3%, p=0.037).

Survivors versus non-survivors

The mean age of survivors was significantly lower than those who died (66.1 versus 74.4 years, p<0.001). The survivor group also had a significantly lower median CFS than the non-survivor group (2 versus 4, p<0.001). Patients in the non-survivor group had a significantly higher mean respiratory rate prior to CPAP/HFNO initiation when compared to survivors (28.7 versus 25.3, p=0.003). In those who received CPAP, higher initial positive end-expiratory pressures (PEEP) were required in the non-survivor group to attain target oxygen saturation (mean PEEP 9.7 cmH2O versus 8.4 cmH2O, p=0.021). The non-survivors who received CPAP also required a higher initial inspiratory oxygen fraction (FIO2) to attain target oxygen saturation (59.6 versus 71.1, p=0.002). We did not observe any difference in white cell count (WCC), lymphocyte count or C-reactive protein between those who survived and those who did not. All patient data and comparison between survivors and non-survivors is displayed in table 1.

TABLE 1.

Comparison of physiological, biochemical and admission data in patients who survived and those who did not

| All patients | Survivors | Non-survivors | p-value | |

| Subjects, n | 140 | 58 | 82 | |

| Age, mean±sd | 71.24±11.1 | 66.1±12.4 | 74.4±9.0 | <0.001 |

| Male, n (%) | 91 (65) | 34 (59) | 55 (67) | 0.433 |

| Clinical Frailty Score, median (range) | 3 (1–7) | 2 (1–5) | 4 (1–7) | <0.001 |

| CPAP/HFNO duration days, median (range) | 3.5 (1–24) | 4 (1–24) | 3.5 (1–18) | 0.642 |

| CPAP/HFNO well tolerated, n (%) | 120 (86) | 50 (85) | 67 (79) | 0.098 |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | ||||

| HTN | 83 (59) | 33 (57) | 50 (61) | 0.909 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 40 (29) | 15 (26) | 25 (30) | 0.685 |

| COPD | 36 (26) | 9 (16) | 27 (33) | 0.031 |

| Asthma | 15 (11) | 10 (17) | 5 (6) | 0.026 |

| Home NIV/CPAP | 15 (11) | 5 (9) | 10 (12) | 0.568 |

| Previous cancer | 14 (10) | 2 (3) | 12 (15) | 0.037 |

| IHD | 38 (27) | 7 (12) | 31 (38) | 0.001 |

| Smoking history | 70 (50) | 24 (41) | 46 (56) | 0.127 |

| Obesity | 52 (37) | 17 (29) | 35 (43) | 0.022 |

| Laboratory results, mean±sd | ||||

| Admission WCC ×109·L−1 | 9.7±4.4 | 7.8±3.4 | 10.6±5.1 | 0.185 |

| Admission lymphocyte count ×109·L−1 | 1.02±0.64 | 1.07±0.89 | 0.98±0.69 | 0.631 |

| Admission C-reactive protein mg·L−1 | 155±95.5 | 154±76 | 147±107 | 0.129 |

| Observations pre-CPAP/HFNO, mean±sd | ||||

| Respiratory rate | 25.9±6.0 | 25.3±5.9 | 28.7±6.8 | 0.003 |

| Heart rate | 89.4±17.0 | 89.9±19.1 | 97.3±21.9 | 0.147 |

| Oxygen saturations | 88.8±6.9 | 86.9±8.1 | 87.0±5.3 | 0.387 |

| PaO2/FIO2 ratio | 76.5±39.1 | 78.6±35.9 | 75.2±41.3 | 0.652 |

| CPAP/HFNO settings, mean±sd | ||||

| Starting CPAP PEEP | 9.2±1.8 | 8.4±2.1 | 9.7±1.9 | 0.012 |

| Starting CPAP FIO2 | 66.9±17.5 | 59.6±16.7 | 71.1±16.7 | 0.002 |

| Starting HFNO flow rate L·min−1 | 54.0±10.1 | 53.9±10.1 | 54.1±10.3 | 0.887 |

| Starting HFNO FIO2 | 70.0±14.6 | 70.4±15.9 | 69.7±14.0 | 0.966 |

CPAP: continuous positive airway pressure; HFNO: high-flow nasal oxygen; HTN: hypertension; NIV: noninvasive ventilation; IHD: ischaemic heart disease; WCC: white cell count; PaO2: arterial oxygen tension; FIO2: inspiratory oxygen fraction; PEEP: positive end-expiratory pressure.

There was no difference in time from hospitalisation to initiation of CPAP/HFNO between survivors and non-survivors (median time to initiation (range) 2 days (1–30) versus 2 days (1–14)). The median (range) duration of CPAP/HFNO treatment for all patients was 3.5 days (1–24); there was no difference between survivors and non-survivors (median (range) 4 (1–24) days versus 3.5 (1–18) days, p=0.454).

Patients considered unsuitable for invasive mechanical ventilation: survivors versus non-survivors

There was no significant difference in age between survivors and non-survivors in the group of patients deemed unsuitable for invasive mechanical ventilation, although the mean age was numerically lower in survivors (mean age 72.4 versus 76.3 years, p=0.053). The survivor group had a significantly lower median CFS score (3.5 versus 4, p=0.022). The survivor group had a significantly higher proportion of patients with obesity (48% versus 34%, p=0.033). Patients that did not survive their admission had a significantly higher white cell count prior to the initiation of CPAP/HFNO (mean WCC 11.5 versus 7.4, p=0.036). Data for patients that were considered unsuitable for invasive mechanical ventilation are displayed in table 2.

TABLE 2.

Comparison of physiological, biochemical and admission data between survivors and non-survivors in the group of patients deemed unsuitable for invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV)

| All patients considered not suitable for IMV | Not suitable for IMV survivors | Not suitable for IMV non-survivors | p-value | |

| Subjects, n | 98 | 27 | 71 | |

| Age, mean±sd | 76.1±4.6 | 72.4±4.1 | 76.3±4.8 | 0.053 |

| Male, n (%) | 58 (59) | 14 (52) | 44 (62) | 0.362 |

| Clinical Frailty Score, median (range) | 4 (1–6) | 3.5 (2–5) | 4 (1–6) | 0.022 |

| CPAP/HFNO duration days, median (range) | 4 (1–24) | 7 (1–24) | 4 (1–11) | 0.172 |

| CPAP/HFNO well tolerated, n (%) | 81 (83) | 25 (93) | 56 (79) | 0.053 |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | ||||

| HTN | 63 (64) | 18 (67) | 45 (58) | 0.593 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 29 (30) | 9 (33) | 20 (31) | 0.539 |

| COPD | 32 (33) | 5 (19) | 27 (38) | 0.081 |

| Asthma | 6 (6) | 1 (4) | 5 (6) | 0.563 |

| Home NIV/CPAP | 12 (12) | 4 (15) | 8 (11) | 0.585 |

| Previous cancer | 12 (12) | 2 (7) | 10 (19) | 0.397 |

| IHD | 32 (33) | 5 (19) | 27 (38) | 0.081 |

| Smoking history | 49 (50) | 11 (41) | 38 (54) | 0.258 |

| Obesity | 37 (38) | 13 (48) | 24 (34) | 0.033 |

| Laboratory results, mean±sd | ||||

| Admission WCC ×109·L−1 | 10.5±5.2 | 7.4±4.3 | 11.5±5.1 | 0.036 |

| Admission lymphocyte count ×109·L−1 | 0.98±0.6 | 0.81±0.46 | 1.04±0.75 | 0.425 |

| Admission C-reactive protein mg·L−1 | 160±105 | 191±78 | 150±113 | 0.160 |

| Observations pre-CPAP/HFNO, mean±sd | ||||

| Respiratory rate | 28.5±6.6 | 26.3±5.8 | 29.2±6.8 | 0.052 |

| Heart rate | 97.9±21.9 | 89.8±17.1 | 100.6±23.0 | 0.089 |

| Oxygen saturations | 88.6±7.5 | 88.4±7.6 | 88.6±5.9 | 0.899 |

| PaO2/FIO2 ratio | 75.7±40.1 | 75.1±38.8 | 75.9±40.9 | 0.932 |

| CPAP/ HFNO settings, mean±sd | ||||

| Starting CPAP PEEP | 9.4±1.6 | 8.5±2.0 | 9.7±1.4 | 0.111 |

| Starting CPAP FIO2 | 70.0±19.7 | 75.0±13.8 | 68.3±21.4 | 0.073 |

| Starting HFNO flow rate L·min−1 | 54.2±9.2 | 51.3±9.9 | 55.2±9.1 | 0.308 |

| Starting HFNO FIO2 | 68.3±14.4 | 66.6±16.7 | 69.0±13.8 | 0.702 |

CPAP: continuous positive airway pressure; HFNO: high-flow nasal oxygen; HTN: hypertension; NIV: noninvasive ventilation; IHD: ischaemic heart disease; WCC: white cell count; PaO2: arterial oxygen tension; FIO2: inspiratory oxygen fraction; PEEP: positive end-expiratory pressure.

CPAP versus HFNO

Highest level of treatment analysis

92 patients received CPAP and 28 patients received HFNO as the highest level of their treatment, where CPAP is considered a more advanced modality of respiratory support. There was no difference in inpatient mortality between the CPAP and HFNO groups (60% (n=55) versus 56% (27), p=0.477). The CPAP group had a significantly higher proportion of patients with HTN (65% versus 48%, p=0.044); however, there were no other significant differences in patient characteristics, physiological parameters or laboratory results prior to initiation of respiratory support. Data are presented in table 3.

TABLE 3.

Admission data, comorbidities and physiological parameters of patients treated with either CPAP or HFNO, displayed by highest level of treatment and intention-to-treat analysis

| CPAP: highest level of treatment | HFNO: highest level of treatment | CPAP: intention-to-treat | HFNO: intention-to-treat | |

| Subjects, n | 92 | 48 | 69 | 71 |

| Age, mean±sd | 70.7±10.0 | 71.3±13.9 | 71.1±9.7 | 71.3±12.3 |

| Male, n (%) | 55 (60) | 36 (75) | 44 (64) | 45 (63) |

| Inpatient death, n (%) | 55 (60) | 27 (56) | 40 (58) | 44 (64) |

| Clinical Frailty Score, median (range) | 3 (1–6) | 3 (1–7) | 3.5 (1–7) | 3 (1–7) |

| CPAP/HFNO duration days, median (range) | 4 (1–24) | 3 (1–14) | 4 (1–24) | 3 (1–14) |

| CPAP/HFNO well tolerated, n (%) | 76 (83) | 44 (92) | 56 (81) | 64 (90) |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | ||||

| HTN | 60 (65) | 23 (48) | 42 (61) | 41 (58) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 29 (32) | 11 (23) | 21 (30) | 19 (27) |

| COPD | 27 (29) | 9 (19) | 20 (29) | 16 (23) |

| Asthma | 9 (10) | 6 (13) | 5 (7) | 10 (14) |

| Home NIV/CPAP | 12 (13) | 3 (6) | 10 (14) | 5 (7) |

| Cancer | 7 (8) | 7 (15) | 4 (6) | 10 (14) |

| IHD | 27 (29) | 11 (23) | 19 (28) | 19 (27) |

| Smoking history | 51 (55) | 19 (40) | 31 (45) | 39 (55) |

| Obesity | 35 (38) | 17 (35) | 29 (42) | 24 (34) |

| Laboratory results, mean±sd | ||||

| Admission WCC ×109·L−1 | 9.4±4.9 | 10.1±4.1 | 9.0±4.6 | 8.8±4.2 |

| Admission lymphocyte count ×109·L−1 | 0.97±0.76 | 1.01±0.54 | 0.99±0.75 | 1.04±0.54 |

| Admission C-reactive protein mg·L−1 | 138.3±82.1 | 144.7±96.6 | 143.0±82.9 | 138.1±91.0 |

| Observations pre-CPAP/HFNO, mean±sd | ||||

| Respiratory rate | 27.8±6.8 | 24.4±4.9 | 26.1±6.0 | 25.8±5.9 |

| Heart rate | 89.6±17.7 | 88.7±15.3 | 91.7±17.7 | 87.3±16.0 |

| Oxygen saturations | 88.3±6.8 | 90.6±6.9 | 87.9±7.5 | 90.0±6.1 |

| FIO2 | 79.5±23 | 83.8±26.1 | 82.0±23.5 | 83.9±20.5 |

| PaO2/FIO2 ratio | 76.0±34.5 | 77.3±38.2 | 77.3±38.2 | 75.9±40.3 |

CPAP: continuous positive airway pressure; HFNO: high-flow nasal oxygen; HTN: hypertension; NIV: noninvasive ventilation; IHD: ischaemic heart disease; WCC: white cell count; PaO2: arterial oxygen tension; FIO2: inspiratory oxygen fraction.

Intention-to-treat analysis

69 patients received CPAP and 71 patients received HFNO as their initial modality of respiratory support. There was no difference in inpatient mortality between the CPAP and HFNO groups (58% (n=40) versus 64% (n=44), p=0.530). There were no significant differences between the two groups with regards to baseline data, patient characteristics, physiological parameters or laboratory results prior to initiation of respiratory support. All patient data comparing those who received CPAP or HFNO on an intention-to-treat basis can be found in table 3.

Treatment tolerance

86% (n=120) of patients were documented as tolerating their treatment with either CPAP or HFNO. There was no significant difference in tolerability of CPAP/HFNO between survivors and non-survivors; there was also no significant difference in tolerability between the different modalities of respiratory support when analysed by highest level of support and on an intention-to-treat basis.

Discussion

We observed that 41.4% of patients who were treated for hypoxaemic respiratory failure secondary to COVID-19 pneumonia were discharged home after receiving either CPAP or HFNO on an RSU. We also observed that 27.6% of patients deemed unsuitable for invasive ventilation were able to be discharged home after such treatment. Many patients in our cohort had comorbidities, with more than half having at least one, and were deemed frail upon holistic assessment. Despite this, many were treated successfully on the RSU with noninvasive respiratory support.

CPAP is a noninvasive form of positive airway pressure ventilation. It delivers a constant pressure throughout the respiratory cycle, preventing small airway collapse and allowing patient-initiated breaths to recruit more lung capacity [10]. HFNO is a method of oxygen supplementation which provides humidified oxygen with a flow rate of up to 100 L·min−1 and an FIO2 of between 21% and 100%. It is believed to offer respiratory support by reduction in work of breathing, providing a low level of PEEP and by improving mucociliary clearance through humidification of the oxygen [11]. Early in the course of the COVID-19 pandemic, these modalities were deemed controversial due to the lack of quality evidence for their use in the treatment of bacterial pneumonia [12, 13]. However, these modalities are now being utilised frequently worldwide for COVID-19 pneumonia, and recent studies have aimed to evaluate their utility.

Our findings are comparable to other studies reporting outcomes of noninvasive respiratory support outside of the ICU setting. A study by Coppadoro et al. [14] that observed outcomes of patients treated with helmet CPAP outside of the ICU reported 72% mortality in patients deemed unsuitable for invasive mechanical ventilation and similarly reported that younger age was significantly associated with better outcomes. Another study by Vaschetto et al. [8] reported 34% mortality among 397 patients treated with CPAP outside of the ICU, as well as 73% mortality in the 140 patients who were deemed unsuitable for invasive ventilation. Conversely, Brusasco et al. [15] reported 83% survival in 64 patients treated with CPAP on a general respiratory ward, although patient demographics were unavailable. Data from patients treated with HFNO also paint a mixed picture. Patel et al. [5] report low inpatient mortality of 14.4% in 104 patients treated with HFNO, although the mean age of patients included in the study was 60.6 years, which is lower than in our cohort. In contrast, Calligaro et al. [16] report a mortality rate of 48% for 293 patients treated with HFNO. Indeed, the overall mortality rates reported for different cohorts will vary based on the case mix of patients studied; however, all studies mentioned indicate that both treatment strategies are useful in both the prevention of progression to mechanical ventilation and as definitive treatment for respiratory failure in COVID-19 patients. A strength of our study is that we did not select patients to be included, but we analysed data from all patients that received noninvasive respiratory support outside intensive care in our hospital over the course of the pandemic, providing an accurate representation of the patient population presenting to hospital with COVID-19 in the UK.

Our observed inpatient mortality is higher than that published by the UK Intensive Care National Audit and Research Centre (ICNARC), which reports 38.3% mortality in patients over the age of 70 treated with advanced respiratory support (CPAP and HFNO are included in this definition) in the ICU [17]. This is numerically lower than the 58.6% mortality observed in our cohort (mean age 71.2 years), However, our data and that of the ICNARC cohort are not directly comparable. Coexistent comorbidities are a well-recognised risk factor for mortality in hospitalised COVID-19 patients [18, 19]; our cohort has a much higher prevalence of comorbidities as compared to the ICNARC cohort, though how these are defined varies between the two. Similarly, there would be differences between frailty levels of patients as well as proportion considered suitable for invasive mechanical ventilation in the event of deterioration on CPAP/HFNO. We believe that in the setting of the provision of critical care in the UK, our patient cohort includes many who may not conventionally be considered for treatment on the ICU. We feel as though this cohort has been seldom observed and our data help to inform management decisions of older, more frail and comorbid patients with COVID-19 pneumonia.

We do not yet know which modality of respiratory support is superior (if either) in the treatment of these patients. Our data do not portray any differences in outcomes for either CPAP or HFNO, and meaningful conclusions regarding treatment superiority cannot be drawn from observational data alone. RECOVERY-RS [20] aims to assess the effectiveness of CPAP, HFNO and standard oxygen delivery in a randomised controlled trial and will hopefully provide definitive data to inform decision-making about which respiratory support strategy is most likely to be of benefit to individual patients.

A recent study by Voshaar et al. [21] expressed an argument for “permissive hypoxaemia”, where they did not enforce a target for oxygen saturation, which allowed them to reduce the number of patients intubated. This resulted in a treatment success rate for CPAP of 83% in patients who were deemed suitable for invasive mechanical ventilation, and they concluded that we should perhaps treat more patients with noninvasive methods of respiratory support. This report has been the topic of some discussion since its publication [22, 23]. Although our data are not sufficient to draw conclusions regarding the comparison of invasive mechanical ventilation and noninvasive ventilation, we did observe 31 patients who were deemed suitable for mechanical ventilation who survived to discharge without invasive mechanical ventilation. This would suggest that this cohort of patients can be safely and effectively managed on a specialised RSU, thus preserving intensive care capacity for COVID-19 patients requiring intubation and non-COVID-19 patients with intensive care requirements.

There are limitations to our study, including the lack of a control or comparison group and that patient outcomes beyond hospital discharge are not known.

Conclusions

CPAP and HFNO are viable treatment options for patients with hypoxaemic respiratory failure secondary to COVID-19 pneumonia, including those considered unsuitable for invasive ventilation. Patients that are deemed suitable for invasive mechanical ventilation can also be treated safely and effectively outside of ICUs through appropriate use of RSUs, thereby preserving intensive care capacity for COVID-19 patients requiring intubation and non-COVID-19 patients with intensive care requirements.

Footnotes

Provenance: Submitted article, peer reviewed.

Conflict of interest: D.L. Sykes has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: M.G. Crooks has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: K. Thu Thu has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: O.I. Brown has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: T.J.P. Tyrer has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: J. Rennardson has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: C. Littlefield has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: S. Faruqi has nothing to disclose.

References

- 1.BTS/ICS. BTS/ICS Guidance: Respiratory Care in Patients with Acute Hypoxaemic Respiratory Failure Associated with COVID-19. https://www.brit-thoracic.org.uk/document-library/quality-improvement/covid-19/btsics-guidance-respiratory-care-in-patients-with-acute-hypoxaemic-respiratory-failure-associated-with-covid-19/ Date last accessed: 12 April 2021.

- 2.Nightingale R, Nwosu N, Kutubudin F, et al. Is continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) a new standard of care for type 1 respiratory failure in COVID-19 patients? A retrospective observational study of a dedicated COVID-19 CPAP service. BMJ Open Respir Res 2020; 7: e000639. doi: 10.1136/bmjresp-2020-000639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ashish A, Unsworth A, Martindale J, et al. CPAP management of COVID-19 respiratory failure: a first quantitative analysis from an inpatient service evaluation. BMJ Open Respir Res 2020; 7: e000692. doi: 10.1136/bmjresp-2020-000692 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mellado-Artigas R, Ferreyro BL, Angriman F, et al. High-flow nasal oxygen in patients with COVID-19-associated acute respiratory failure. Crit Care 2021; 25: 58. doi: 10.1186/s13054-021-03469-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Patel M, Gangemi A, Marron R, et al. Retrospective analysis of high flow nasal therapy in COVID-19–related moderate-to-severe hypoxaemic respiratory failure. BMJ Open Respir Res 2020; 7: e000650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sykes DL, Parthasarthy A, Brown OI, et al. COVID-19 progression, frailty, and use of prolonged continuous positive airway pressure as a ward-based treatment: lessons to be learnt from a case. Lung India 2021; 38, Suppl S1: 64–68. doi: 10.4103/lungindia.lungindia_583_20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guy T, Créac'hcadec A, Ricordel C, et al. High-flow nasal oxygen: a safe, efficient treatment for COVID-19 patients not in an ICU. Eur Respir J 2020; 56: 2001154. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01154-2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vaschetto R, Barone-Adesi F, Racca F, et al. Outcomes of COVID-19 patients treated with continuous positive airway pressure outside the intensive care unit. ERJ Open Res 2021; 7: 00541-2020. doi: 10.1183/23120541.00541-2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rockwood K, Song X, MacKnight C, et al. A global clinical measure of fitness and frailty in elderly people. CMAJ 2005; 173: 489–495. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.050051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schlobohm RM, Falltrick RT, Quan SF, et al. Lung volumes, mechanics, and oxygenation during spontaneous positive-pressure ventilation: the advantage of CPAP over EPAP. Anesthesiology 1981; 55: 416–422. doi: 10.1097/00000542-198110000-00013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Renda T, Corrado A, Iskandar G, et al. High-flow nasal oxygen therapy in intensive care and anaesthesia. Br J Anaesth 2018; 120: 18–27. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2017.11.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.NICE. Pneumonia: diagnosis and management of community- and hospital-acquired pneumonia in adults. www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg191/documents/pneumonia-guideline-consultation-full-guideline2 Date last accessed: 6 June 2021.

- 13.Helviz Y, Einav S. A systematic review of the high-flow nasal cannula for adult patients. Crit Care 2018; 22: 71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Coppadoro A, Benini A, Fruscio R, et al. Helmet CPAP to treat hypoxic pneumonia outside the ICU: an observational study during the COVID-19 outbreak. Crit Care 2021; 25: 80. doi: 10.1186/s13054-021-03502-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brusasco C, Corradi F, Di Domenico A, et al. Continuous positive airway pressure in Covid-19 patients with moderate-to-severe respiratory failure. Eur Respir J 2021; 57: 2002524. doi: 10.1183/13993003.02524-2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Calligaro GL, Lalla U, Audley G, et al. The utility of high-flow nasal oxygen for severe COVID-19 pneumonia in a resource-constrained setting: a multi-centre prospective observational study. EClinicalMedicine 2020; 28: 100570. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.icnarc. COVID-19 Report. www.icnarc.org/Our-Audit/Audits/Cmp/Reports Date last accessed: 14 April 2021.

- 18.Tian W, Jiang W, Yao J, et al. Predictors of mortality in hospitalized COVID-19 patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Med Virol 2020; 92: 1875–1883. doi: 10.1002/jmv.26050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Noor FM, Islam MM. Prevalence and associated risk factors of mortality among COVID-19 patients: a meta-analysis. J Community Health 2020; 45: 1270–1282. doi: 10.1007/s10900-020-00920-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Perkins GD, Couper K, Connolly B, et al. RECOVERY- respiratory support: respiratory strategies for patients with suspected or proven COVID-19 respiratory failure; continuous positive airway pressure, high-flow nasal oxygen, and standard care: a structured summary of a study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials 2020; 21: 687. doi: 10.1186/s13063-020-04617-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Voshaar T, Stais P, Köhler D, et al. Conservative management of COVID-19 associated hypoxaemia. ERJ Open Res 2021; 7: 00292-2021. doi: 10.1183/23120541.00292-2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Windisch W, Kluge S, Bachmann M, et al. Conservative management of COVID-19 associated hypoxaemia. ERJ Open Res 2021; 7: 00113-2021. doi: 10.1183/23120541.00113-2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morice AH. COVID-19 controversy: when to intubate? ERJ Open Res 2021; 7: 00185-2021. doi: 10.1183/23120541.00185-2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]